Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) contribute significantly to morbidity and mortality in healthcare facilities, especially in the intensive care unit (ICU).Reference Magill, Edwards and Bamberg1, Reference Maragakis2 Pathogenic bacteria, including multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs), such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), are transmitted to patients via contact with healthcare workers and via contact with environments and surfaces surrounding the patient.Reference Otter, Yezli and French3 Although many previous studies have examined the role of healthcare workers’ hands in pathogen transmission, several recent studies have also highlighted the fact that patients’ hands are often contaminated and may contribute to pathogen transmission.Reference Istenes, Bingham, Hazelett, Fleming and Kirk4–Reference Mody, Washer and Kaye8 All of these studies were conducted on general medical and surgical wards or on transfer from acute to postacute care. We aimed to determine the prevalence of patient hand contamination with MDROs and other pathogenic bacteria in the ICU setting.

Methods

This prospective observational study was conducted in 3 ICUs at a tertiary-care center with approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Cleveland Clinic during the course of a randomized, double-blinded crossover study.Reference Mody, Washer and Kaye8 Informed consent was obtained from all patients and/or their family members. An imprint of one of the patient’s hands was obtained on a nonselective tryptic soy agar handprint plate that contained 0.01% lecithin and 0.5% polysorbate 80. Handprint plates were incubated at 35 ± 2°C for 24 ± 4 hours, and bacterial colonies, including MSSA, MRSA, VRE, ciprofloxacin-resistant gram-negative bacteria, ciprofloxacin-sensitive Klebsiella spp, Pseudomonas spp, and normal skin flora (ie, Diphtheroid, Bacillus, Micrococcus, and Staphylococcus spp), were identified using standard microbiologic methods. Each patient provided a single handprint sample, and no other patient information was collected or identified for this study.

Results

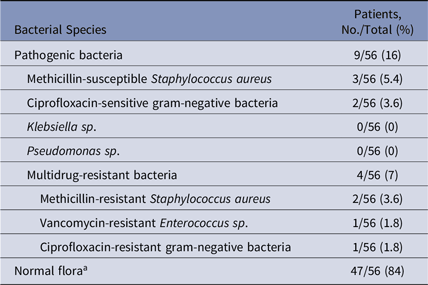

In total, 56 unique patients agreed to participate in the study, and their hand imprints were obtained over a period of 10 weeks. Of 56 patients, 9 (∼16%) had at least 1 aerobic pathogenic bacteria on a hand. Of those 56 with pathogenic bacteria, 4 (∼7%) had at least 1 MDRO on their hand: 2 patients had MRSA, 1 patient had VRE, and 1 patient had ciprofloxacin-resistant gram-negative bacteria. Most patients (47 of 56) had normal skin flora (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient Hand Carriage of Aerobic Bacterial Organisms

a Diptheroid spp, Bacillus spp, Micrococcus spp, and Staphylococcus spp.

Discussion

The results of our study demonstrate that a small portion of patients’ hands in medical ICUs harbor pathogenic bacteria, including MDROs. These results appear to be consistent with prior studies that investigated the burden of pathogenic organisms on patients’ hands, though the prevalence of contamination with MDROs appears to be lower in our study. In a 100-patient study on non-ICU medical and surgical unit floors, 39% of patients’ hands were contaminated with at least 1 pathogenic organism 48 hours after admission. Similarly, when 357 newly admitted patients in postacute-care facilities hands were swabbed, 24% of patients had at least 1 MDRO, and another 10% had acquired an MDRO during their stay.Reference Kundrapu, Sunkesula, Jury, Deshpande and Donskey5, Reference Deshpande, Fox and Wong9 The difference in prevalence of MDROs between our study and prior studies may be because of our focus on ICU patients, who underwent daily chlorhexidine bathing per protocol. Previous studies have also demonstrated a potential relationship between patient hand contamination and contamination of high-touch room surfaces. In a study of ∼400 non-ICU general medicine floor patients, 10% of patients’ hands were contaminated with MDROs, and there was a correlation between the MDROs on patient hands and the contaminated room surfaces.Reference Cao, Min, Lansing, Foxman and Mody7

Despite the emerging evidence potentially highlighting the role of patient hand hygiene in the transmission of HAIs, current best-practice recommendations do not provide a strong guidance regarding patient hand hygiene. One previous study has demonstrated that bundling of infection prevention strategies including patient hand hygiene can potentially reduce the rate of hospital-acquired infections, including Clostridioides difficile.Reference Pokrywka, Feigel and Douglas10 Therefore, building and implementing effective patient hand hygiene protocols and/or bundles has the opportunity to reduce the risk of life-threatening HAIs.

The strengths of this study include its relatively novel focus on the burden on MDROs on patients’ hands in an ICU setting and the study’s contribution to ongoing discussions surrounding infection prevention strategies targeting patient hand hygiene. On the other hand, our study was performed at a single tertiary-care center, and our results may not be applicable to other hospital settings. Furthermore, this study reports patient microbial colonization of hands, which does not necessarily indicate clinical infection. In addition, agar hand plates were used to assess bacterial contamination instead of the glove juice technique. The handprint method can be less effective because it solely provides information about the microbial burden from the anterior surface of the hand, whereas the glove-juice technique recovers microbes from the entire hand. Thus, the hand plate technique may yield comparatively less microbe recovery.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that ICU patients’ hands may harbor pathogenic bacteria, providing further evidence that poor patient hand hygiene may contribute to transmission of resistant HAIs. Further studies are necessary to understand barriers to adequate patient hand hygiene and to identify best practice strategies.

Acknowledgments

None.

Financial support

This study was funded by 3M.

Conflicts of interest

A.D. has received research funding from 3M and Clorox and is on the advisory board of Ferring Pharmaceuticals. C.J.D. has received research funding from Gojo, PDI and Clorox. S.D. is on the advisory board of 3M. All other authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.