What follows presents two hitherto unstudied Persian compilations. Known in several manuscript collections under the same generic titles, Muntakhab-i Bustān or Intikhāb-i Bustān (“Selections of the Bustān”), these texts consist of selections of verses from the Bustān (“Orchard”) of Saʿdī Shirāzi (d. ca. 693/1292), a didactic poem completed around the middle of the thirteenth century. Eleven copies can be identified. They were executed between the 1470s and the 1550s in a geographical area spanning from Turkey to Central Asia.Footnote 1

A long ma![]() navī (poem written in rhyming couplets) of approximately four thousand verses, the Bustān of Saʿdī consists of a preface (dībācha) and ten chapters, each deploying a succession of short stories interspersed with moral advice.Footnote 2 Generally labeled as literature of advice or didactic literature, this poem is often classified as a mirror for princes, a literary genre destined to instruct rulers on certain aspects of government and behavior. But the Bustān is also a multifaceted, polyvalent text.Footnote 3 Mixing different patterns of speech, style, and literary genre, it interweaves epic tales with humoristic anecdotes, narrative poems with proverbial sentences, mythical stories with philosophical statements, thus addressing a wide range of themes such as love, education, speech, or ascetic life.Footnote 4 The Bustān is also known for its literariness or reflexive qualities. While a few stories stage a character named Saʿdī, other passages comment upon the structure and function of the Bustān, and in particular its multilayered, duplicitous ethics, for example when the poem is compared to a date fruit whose first, sweet layer protects a more central, enigmatic kernel.Footnote 5

navī (poem written in rhyming couplets) of approximately four thousand verses, the Bustān of Saʿdī consists of a preface (dībācha) and ten chapters, each deploying a succession of short stories interspersed with moral advice.Footnote 2 Generally labeled as literature of advice or didactic literature, this poem is often classified as a mirror for princes, a literary genre destined to instruct rulers on certain aspects of government and behavior. But the Bustān is also a multifaceted, polyvalent text.Footnote 3 Mixing different patterns of speech, style, and literary genre, it interweaves epic tales with humoristic anecdotes, narrative poems with proverbial sentences, mythical stories with philosophical statements, thus addressing a wide range of themes such as love, education, speech, or ascetic life.Footnote 4 The Bustān is also known for its literariness or reflexive qualities. While a few stories stage a character named Saʿdī, other passages comment upon the structure and function of the Bustān, and in particular its multilayered, duplicitous ethics, for example when the poem is compared to a date fruit whose first, sweet layer protects a more central, enigmatic kernel.Footnote 5

With its discontinuous structure and thematic diversity, the Bustān constantly oscillates between order and disorder, fragment and whole, situated detail and general lesson. A garden of words rather than a successive, linear discourse, it invites readers to read around rather than through the whole text, and thus to rearrange the poem as they please. As a matter of fact, verses from the Bustān were frequently used as quotations in literary texts or as epigraphic inscriptions on portable objects and architectural monuments.Footnote 6 This paper is devoted to such an example of reuse. It presents two different compilations of Saʿdī’s Bustān. For each compilation, a few hundred verses were selected from the Bustān and mixed together in order to form a shorter poem. The earliest known copies of these compilations date back to the fifteenth century.Footnote 7

Given the lack of scholarship on this material, I first describe the texts of the two compilations as well as their relation to the complete Bustān. Each compilation consists of a certain number of verses chosen from among the 4,000 verses of the complete poem. Although the Bustān’s total number of verses varies from one manuscript to another, the compilations’ verses are found in most copies of the complete Bustān produced during the same period, as well as in the modern critical edition of Ghulām-Ḥusayn Yūsufī published in 1963. The first one is composed of approximately 150 verses while the second includes around 500 verses. These compilations are different, sharing fewer than fifty verses, and they each depart considerably from the complete Bustān. Neither of them emulates the thematic and stylistic diversity of the poem. Instead of the heterogeneous, centrifugal richness of the Bustān, they offer discrete, focused texts, reassembling the Bustān into a uniform, contained garden. More specifically, it seems that verses were picked in such a way as to inflect the Bustān’s literary genre. As this paper suggests, the shorter compilation reinforces the mirror-for-princes function of the Bustān. The longer one, by contrast, leans toward mysticism, privileging verses that echo Sufi erotic theology.

Next, I consider the manuscripts containing these compilations in order to address further aspects of reception and circulation. Although it remains difficult to assess when and by whom these compilations were made, manuscript copies offer invaluable information on their use and transmission. The compilations appear to have been particularly appreciated during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in Iran, Central Asia, and Turkey. Most of them were copied in small manuscripts, hardly exceeding twenty-five folios, a format that enhances both their portability and their intimate character. Some copies were lavishly decorated and illustrated. The short compilation, which features an anthology of political advice, was diffused in princely circles in western Iran and Turkey. It was passed from the Aq Qoyunlu court to the Safavids to the Ottomans.Footnote 8 In contrast, all copies of the second compilation were produced in the East, in the regions of Khurasan and Transoxiana.Footnote 9 Interestingly enough, these patterns of circulation are reflected in the paintings accompanying the text, emphasizing the settings in which the compilations could be received.

Mirror for Princes

Let us start with the compilation that was diffused in western Iran and Turkey.Footnote 10 A rather short selection, its 150 verses were drawn exclusively from the moral discourse of the Bustān, thus forming a collection of am![]() āl (proverbs, aphorisms) and pand (pieces of advice). No narrative verses were thus included. This technique of extracting moral aphorisms from their narrative contexts was quite common. Several authors approached the Shāhnāma of Firdawsī in this manner. In 1081, a certain ʿAlī b. Aḥmad made a collection of moral verses known as Ikhtiyārāt-i Shāhnāma or Kitāb-i Intikhāb-i Shāhnāma (“Selections of the Shāhnāma”) which he presented as a book of wisdom.Footnote 11 In his Rāḥat al-ṣudūr wa āyat al-surūr (“Ease of Hearts and Marvel of Happiness”), written in the early thirteenth century, Muḥammad b. ʿAlī Rāvandī quoted lengthy series of verses from the Shāhnāma, mostly from its non-historical sections. As explained in the preface, Rāvandī’s objective was “to choose some selections of poetry and prose, and compile them into a collection so that [men] might learn from them.”Footnote 12 By privileging general and proverbial quotations from the Shāhnāma, his text reveals a reception of Firdawsī’s poem as a mirror for princes, as Julie Scott Meisami and other scholars have shown.Footnote 13 More generally, selections from the Shāhnāma seem to have been available to medieval authors as independent works, as reservoirs of wisdom from which they could pick wise sayings before incorporating them as quotations in their own work, as Nasrin Askari has suggested.Footnote 14

āl (proverbs, aphorisms) and pand (pieces of advice). No narrative verses were thus included. This technique of extracting moral aphorisms from their narrative contexts was quite common. Several authors approached the Shāhnāma of Firdawsī in this manner. In 1081, a certain ʿAlī b. Aḥmad made a collection of moral verses known as Ikhtiyārāt-i Shāhnāma or Kitāb-i Intikhāb-i Shāhnāma (“Selections of the Shāhnāma”) which he presented as a book of wisdom.Footnote 11 In his Rāḥat al-ṣudūr wa āyat al-surūr (“Ease of Hearts and Marvel of Happiness”), written in the early thirteenth century, Muḥammad b. ʿAlī Rāvandī quoted lengthy series of verses from the Shāhnāma, mostly from its non-historical sections. As explained in the preface, Rāvandī’s objective was “to choose some selections of poetry and prose, and compile them into a collection so that [men] might learn from them.”Footnote 12 By privileging general and proverbial quotations from the Shāhnāma, his text reveals a reception of Firdawsī’s poem as a mirror for princes, as Julie Scott Meisami and other scholars have shown.Footnote 13 More generally, selections from the Shāhnāma seem to have been available to medieval authors as independent works, as reservoirs of wisdom from which they could pick wise sayings before incorporating them as quotations in their own work, as Nasrin Askari has suggested.Footnote 14

In the compilations of the Bustān, one must further note that the aphoristic verses were picked from disparate chapters and arranged in an order that differs from the complete Bustān. As such these compilations contrast with other selections of ma![]() navīs found in anthologies such as the so-called Safīna-yi Tabrīz, compiled in Tabriz in the 1330s, in which verses were selected in a linear way, following the order of the complete poem.Footnote 15 Verses were also chosen in a linear fashion in the anthologies made for the Timurid prince Iskandar Sulṭān in Shiraz and Isfahan between 1410 and 1413, in which they follow not only the order but also the structure of the complete editions of the ma

navīs found in anthologies such as the so-called Safīna-yi Tabrīz, compiled in Tabriz in the 1330s, in which verses were selected in a linear way, following the order of the complete poem.Footnote 15 Verses were also chosen in a linear fashion in the anthologies made for the Timurid prince Iskandar Sulṭān in Shiraz and Isfahan between 1410 and 1413, in which they follow not only the order but also the structure of the complete editions of the ma![]() navīs, hence offering more of a summary than a rewriting of the text.Footnote 16

navīs, hence offering more of a summary than a rewriting of the text.Footnote 16

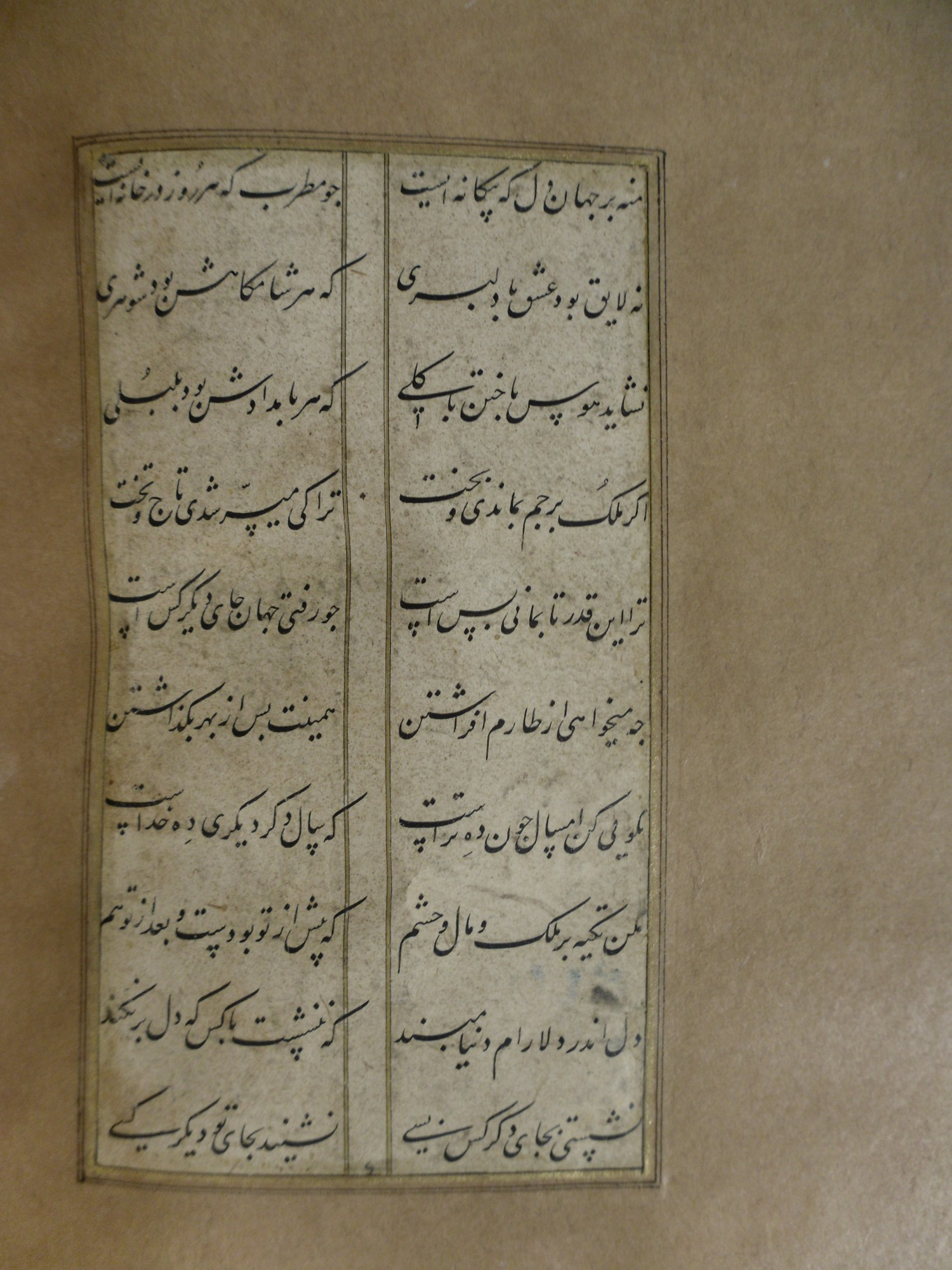

In contrast, in the compilations of the Bustān, a new order of verses is created, as can be seen from the following extract (Figure 1)Footnote 17 (after the Persian text, an English translation is provided, together with, in italics at the end of each verse, the chapter number and two verse numbers: the verse number in the English translation by G. M. Wickens, followed by the verse number in the Persian edition of Ghulām-Ḥusayn Yūsufī):Footnote 18

Figure 1. Intikhāb-i Bustān, ca. 833/1478, Art and History Trust collection, accession no. 48 and 71, fol. 6b (photograph by the author).

In this succession of ten verses, four chapters from the Bustān are represented, chapter one, six, seven, and nine, and arranged in a “random” fashion. Verses from the first chapter appear after and before verses from chapter seven or nine. However, although they do not reflect the order of Saʿdī’s text, the verses show a certain thematic consistency. One can note in particular the focus on the impermanence of the world.

The verses are also similar in structure and tone. Almost all of them are addressed to the second person, in this case a ruler. In fact, the sixth verse of the sequence, uttered in the first-person singular in Yūsufī’s edition, is here conjugated in the second person, a choice that harmonizes the compilation’s enunciative structure. Using the imperative, the compilation also projects a strong, prescriptive tone. The didactic dimension is enhanced by the recourse to rhetorical questions, as in the passage’s fourth line.

The sequence presents other forms of continuity, in particular stylistic. The second and third verses use the same metaphor, comparing the transience of the world to, respectively, a lover’s infidelity and the inconstancy of a flower. Resonances further appear through parallel constructions and repetition of words and sounds. The same two verses have a common rhyme (in “-i,” see Figure 1). Their second miṣraʿ (hemistich) also starts with the same words (“ki har”—“who each”). Although composed of verses from different chapters, sometimes separated by thousands of verses in the complete Bustān, the compilation forms a new poem with its own thematic, rhythmic, and musical consistency.

The compilation is divided into six different chapters, which all deal with the morality of kings. After a short preface praising God, the first chapter, which is the longest, starts with an elegiac sequence about the transience of the world before warning the kings of the illusion of conquest. The following chapters emphasize various values such as justice, knowledge, contentment, and compassion.

One can also note an emphasis on the pre-Islamic inspiration of the Bustān, as exemplified by the above extract. This compilation uses almost all the verses mentioning exemplary pre-Islamic figures such as Solomon, Jam, or Alexander, while leaving out the many verses devoted to Muslim figures such as the Prophet Muḥammad. In Persian literature, kingly ethics were often conveyed through the examples of Iran’s ancient kings, as in the Shāhnāma of Firdawsī,Footnote 22 a feature that further strengthens the link of this particular compilation of the Bustān to the mirror-for-princes tradition.

Both in structure and content, this Muntakhab clearly diverges from the complete Bustān. First of all, the selection and arrangement of the verses do not follow the structure of a ma![]() navī.Footnote 23 The Muntakhab focuses on moral sentences and makes little use of narrative sections, although these constitute the largest part of the Bustān. Other conventions of the ma

navī.Footnote 23 The Muntakhab focuses on moral sentences and makes little use of narrative sections, although these constitute the largest part of the Bustān. Other conventions of the ma![]() navī are not adhered to. For instance, the introduction contains only the praise of God, whereas the introduction of a ma

navī are not adhered to. For instance, the introduction contains only the praise of God, whereas the introduction of a ma![]() navī typically adds to the doxology a eulogy of the prophet, a dedication to the poet’s patron, and digressions on the occasion for writing the poem. In terms of content and literary genre, the Muntakhab presents a collection of pieces of advice intended for the education of princes, hence magnifying the mirror-for-princes function of the complete Bustān.Footnote 24

navī typically adds to the doxology a eulogy of the prophet, a dedication to the poet’s patron, and digressions on the occasion for writing the poem. In terms of content and literary genre, the Muntakhab presents a collection of pieces of advice intended for the education of princes, hence magnifying the mirror-for-princes function of the complete Bustān.Footnote 24

This compilation does not seem to aim at providing a faithful summary of the text, thus raising the question of whether or not it was inspired by other, intermediary compilations of the Bustān as well as similar collections of moral advice. As a matter of fact, it recalls the epigraphic inscriptions left by Shiraz rulers on the ruins of the palace of Darius in Persepolis, which also used fragments of the Bustān.Footnote 25

In 738/1337–38, Abū Isḥāq b. Maḥmūd from the Inju dynasty had these two successive verses of the Bustān (Chap. I, v. 800/793 and 801/794) inscribed on the ruins:

The same verses appear in the mirror-for-princes Muntakhab. Using pre-Islamic figures as exemplars, they address the theme of the impermanence of power. As such they remarkably encapsulate the general tenor of the Muntakhab and the ways in which the compilation mixes its prescriptive tone with an elegiac, mythological inspiration.

In 826/1422, the Timurid ruler Ibrahīm Sulṭān followed his peer and left several inscriptions. The longest one, supposedly carved by his own hand in naskh script, is also an excerpt from the Bustān. It frames the same two verses inscribed by the Inju ruler with three other verses picked from another section of the Bustān:Footnote 27

This compilation of verses resembles the Muntakhab in both its poietic and thematic aspects. The verses are arranged regardless of their order in the complete text. They also emphasize particular topics, here related to the conduct of rulers, in ways that further testify to a reception of the Bustān as a collection of kingly ethics.

Mystical Twist

The second compilation is three times longer than the first.Footnote 29 It is, moreover, closer to the complete Bustān, in that it actually repeats the form of the ma![]() navī. The introduction includes all the obligatory sections of a ma

navī. The introduction includes all the obligatory sections of a ma![]() navī’s preface mentioned earlier. Another difference with the first Muntakhab is the use of stories. Even if most verses belong to the abstract part of the poem, some narrative extracts were reproduced. The compilation thus emulates the ratio between narrative and proverbial verses that characterizes the form of the ma

navī’s preface mentioned earlier. Another difference with the first Muntakhab is the use of stories. Even if most verses belong to the abstract part of the poem, some narrative extracts were reproduced. The compilation thus emulates the ratio between narrative and proverbial verses that characterizes the form of the ma![]() navī.

navī.

Just as in a ma![]() navī, while each verse can be read independently, the text proposes broader continuous sequences. As an example of how scattered verses were woven into coherent passages, let us take a look at a passage from the Muntakhab’s preface. The extract opens the section usually titled, as in the complete Bustān, “The Reason for Composing the Book” (sabab-i naẓm-i kitāb) (Figure 2):Footnote 30

navī, while each verse can be read independently, the text proposes broader continuous sequences. As an example of how scattered verses were woven into coherent passages, let us take a look at a passage from the Muntakhab’s preface. The extract opens the section usually titled, as in the complete Bustān, “The Reason for Composing the Book” (sabab-i naẓm-i kitāb) (Figure 2):Footnote 30

Figure 2. Intikhāb-i Bustān, begun in 933/1526–27, Art and History Trust collection, accession no. 66, fol. 5a (photograph by the author).

The sequence begins with the first two verses of the corresponding section of the Bustān’s preface. The narrator-author introduces himself as a great traveler. Also compared to harvesting, traveling is consubstantial to writing, the process by which the poet gathers and collects all things seen and heard.

Next, as an example of the stories that Saʿdī could witness along the way, the compiler has inserted the first two verses of a narrative from the third chapter of the complete Bustān. The story is about a physician from Marv who was known for his astounding beauty. The compiler has thus created a multilevel narrative, with an extradiegetic level featuring Saʿdī as the narrator and, embedded into it, a diegetic level that recounts the story of the physician.

The montage is even more intricate. The two following verses were picked from another two different stories. The first one belongs to a story from the third chapter, which similarly evokes a character with a confounding beauty, this time from the city of Samarqand. The following verse is from the fourth chapter and also deals with a character, here a merchant whose success owes much to his countenance. Although these two verses do not belong to the story of the handsome physician of Marv, they can easily be related to it since they describe the devastating effects of physical beauty. The compiler’s strategy is associative, consolidating and developing similar stories.

Thereafter, the text retreats to the story of the doctor, adding the testimony of another character, a patient who would rather be ill than run the risk of never seeing the doctor again. The last verse of the sequence features a more abstract conclusion, highlighting the ability of love to challenge even the more rational minds.

In a few verses, this excerpt encapsulates the complex nature of the Bustān. Using the metaphor of travel, it mirrors the self-referential quality of the poem. By presenting at least two embedded stories—the journey of the narrator-author and the story of the doctor of Marv—it also announces its multilayered diegetic structure. In addition, it links the narrative passages to a moralistic reflection.

At the heart of this passage lies one of the most important themes of the Muntakhab, namely, the link between the contemplation of the beloved and metaphysical experience. This is known in Persian literature as shāhid-bāzī (“playing the witness”), the witnessing of divine presence in worldly manifestations. As early as the tenth century, some Sufi masters discussed the possibility that God might appear in finite, contained forms that humans can grasp, including the form of young males. This is what they called shāhid-bāzī, “a ritualized activity that was grounded on a belief that God may be seen by contemplating pleasant faces that bear witness to divine beauty,” as Lloyd Ridgeon wrote.Footnote 32 Shāhid-bāzī was both a literary and an actual practice, linking the contemplation of external reality to an understanding of divine beauty.Footnote 33

With its emphasis on beauty, love, and sight, the story of the doctor of Marv in fact foregrounds one of Saʿdī’s most important innovations, the integration of eroticism and spirituality. Saʿdī was one of the first poets to address shāhid-bāzī in Persian poetic discourse, by fusing together amorous experience and metaphysical perception, as Domenico Ingenito has shown.Footnote 34 Saʿdī also emphasized the visual aspect of this conflation: God appears in the act of gazing; it is the experience of sight that provides access to inner beauty.Footnote 35

Several other verses work to foreground the metaphysics of love. While it is impossible to generalize on Sufi theology, or even to equate Sufism with mysticism, aspects of the mystical experience do resonate with the Sufi tradition, including its claims of communion with God, and its culmination with the absorption or even the eradication of the self in God, as Ridgeon recently summarized.Footnote 36 At least since the tenth century, ʿishq or passionate love has been central to certain trends of Sufi ascetic theology, including the Persian Sufi tradition of the medieval period, infusing Sufism with a theosophy of eros.Footnote 37 Many Sufis considered love the highest aim of Sufi seekers, the pinnacle of the Sufi path toward transcendence.Footnote 38 Because the ultimate goal was the obliteration of the self, love could lend first to the mystic’s alienation, as the verse following the previous sequence explains:

A stock image of Sufi Persian poetry, the metaphor of the ball and the polo-stick refers to the captivity of the lover, who is played, manipulated by the beloved. A few verses later, an image of the lover’s annihilation appears, comparing the lover to a moth, and the beloved to a candle:Footnote 39

The beloved does not spare the lover any pain. What results from this ordeal is the consumption of the moth, its dissolution into the beloved’s flame: the ultimate goal of the Sufi seeker was the annihilation of selfhood. Entitled “On Love and Lovers” (dar ʿishq u ʿushshāq) in some copies, a whole chapter of the Muntakhab is devoted to the sinuous, painful quest of dervishes, “knowers of the wayside halts, though having lost the track.”Footnote 40 “Drunk with the Cupbearer”Footnote 41—the Cupbearer being another allegorical figure of the Beloved—the Sufi lover cannot help but seek his own destruction. Yet this dangerous love is precisely the key to his liberation, “for if He destroys you,” as the poem suggests, “you will be everlasting.” Sufi love is the guarantee that selfish, earthly life can be dissolved into divine plenitude:

Just as in the Bustān (and many works of advice of this period), the compilation is arranged into ten chapters, some of which repeat the content of their matching chapters in Saʿdī’s complete poem. These include the first chapter on justice (dar ʿadl, “On Justice”), the second chapter on beneficence (dar iḥsān, “On Beneficence”), the third chapter on love (dar ʿishq u ṣifat-i ʿushshāq, “On Love and Lovers”), the fourth chapter on humility (dar tavāżuʿ u takabbur, “On Humility and Pride”) as well as the sixth chapter on contentment (dar saʿādat u qanāʿat, “On Happiness and Contentment”).Footnote 43

The outline, however, also departs from the Bustān. For example, the last three chapters of the complete Bustān, respectively on gratitude, repentance, and close communion, were consolidated into one chapter, often entitled “On Gratitude” (dar shukr). New chapter titles could thus be introduced in the compilation. The most remarkable one is the title of chapter five, “On Proving the Unity” (dar i![]() bāt-i vaḥdat), which foregrounds the Sufi notion of the unity of God and creation, a notion developed in several Sufi works, including in the writings of Ibn ʿArabī (d. 1245) and the poetry of ʿAṭṭār (d. 1221) and Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī (d. 1273).Footnote 44 Several verses included in this chapter denounce the apparent diversity and fragmentation of the world, emphasizing instead the monistic idea of its unity. In the following verses, the dialectic between part and whole is illustrated by the story of the raindrop, which became a pearl as a reward for having recognized both the all-encompassing unity of the ocean and its own nothingness:Footnote 45

bāt-i vaḥdat), which foregrounds the Sufi notion of the unity of God and creation, a notion developed in several Sufi works, including in the writings of Ibn ʿArabī (d. 1245) and the poetry of ʿAṭṭār (d. 1221) and Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī (d. 1273).Footnote 44 Several verses included in this chapter denounce the apparent diversity and fragmentation of the world, emphasizing instead the monistic idea of its unity. In the following verses, the dialectic between part and whole is illustrated by the story of the raindrop, which became a pearl as a reward for having recognized both the all-encompassing unity of the ocean and its own nothingness:Footnote 45

To sum up, in contrast with the first Muntakhab, the second one presents both narrative and aphoristic verses. And instead of a collection of proverbs, it reads as a short ma![]() navī. This is not to say, however, that it is closer to the complete Bustān. Within each chapter, sequences were rearranged by inserting verses from other chapters in order to complement or twist the framing verses. In addition, despite mimicking the original structure of the Bustān, chapter titles can differ in ways that foreground certain themes to the detriment of others.

navī. This is not to say, however, that it is closer to the complete Bustān. Within each chapter, sequences were rearranged by inserting verses from other chapters in order to complement or twist the framing verses. In addition, despite mimicking the original structure of the Bustān, chapter titles can differ in ways that foreground certain themes to the detriment of others.

Thematically, the second Muntakhab foregrounds ideas and lessons that are absent from the first selection. Examples include mystical themes, in particular the practice of shāhid-bāzī and its fusion of spirituality and homoerotic ideals. Such motifs do not necessarily stand out in the complete poem of the Bustān. Verses carrying mystical imagery such as the trope of the candle and the moth are indeed often part of larger stories, where they can be used as metaphorical supplements to reflect upon secular stories. But here, because they are decontextualized and juxtaposed with similarly themed verses, they work to center and intensify a spiritual content, and in particular the aesthetics of shāhid-bāzī, even as those themes might seem peripheral to the complete Bustān.

As such, the second Muntakhab echoes the mystical literature produced in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Khurasan. This is not to say that this particular selection should be attributed to late Timurid/early Safavid Khurasan, only that it testifies to and recalls literary contexts that privileged mystical readings of canonical texts, and that also promoted a reception of Saʿdī as a mystic, as I will suggest below. The Muntakhab resonates for instance with Majālis al-ʿushshāq (The Assembly of Lovers), a collection of imaginary love stories starring legendary and historical personalities. Modern scholars have attributed the work, dated 1503, to Ḥusayn Gazurgāhī, a disciple of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Jāmī and a boon companion of the Timurid ruler Sulṭān Ḥusayn Bayqara (1438–1506).Footnote 46 Lovers include famous Sufis such as Ibn ʿArabī and Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, mythical kings like Solomon, historical rulers such as the Seljuq sultan Malikshāh, and late fifteenth-century figures like Jāmī, Mīr ʿAlī Shīr Navāʾī, and Sulṭān Ḥusayn himself, to whom the last chapter is devoted.Footnote 47 While the stories appear to treat worldly love, most often using homoerotic language, the introduction reminds us of the narratives’ allegorical dimension, of the metaphorical link between carnal and spiritual love.

In terms of poiesis, the Muntakhab recalls the practice of literary imitation developed in Herat at the end of the fifteenth century. A large part of the literary production of late Timurid Herat was devoted to the rewriting of literary models. Most often, literary forms and structures were reused, while the thematic content was adjusted to contemporary literary and intellectual interests. These practices were known as istiqbāl (reception), javāb (response), or tatabbuʿ (imitation) (by the end of the fifteenth century, all three terms were used interchangeably and for different poetic forms, whether the ghazāl, the qaṣīda, or the ma![]() navī).Footnote 48 These literary processes were neither passive nor antiquarian. They did not merely attempt to duplicate, conserve, or restore a tradition. Rather, as Paul Losensky put it, imitation was “simultaneously a method of poetic self-definition, a characteristic feature of the historical period and a form of literary interpretation.”Footnote 49 The aim was to recreate the past in ways that were relevant to the present, while engaging with both the history and the poetics of literature.

navī).Footnote 48 These literary processes were neither passive nor antiquarian. They did not merely attempt to duplicate, conserve, or restore a tradition. Rather, as Paul Losensky put it, imitation was “simultaneously a method of poetic self-definition, a characteristic feature of the historical period and a form of literary interpretation.”Footnote 49 The aim was to recreate the past in ways that were relevant to the present, while engaging with both the history and the poetics of literature.

Responses were performed by a great variety of writers, orally during the majlis (a form of literary gathering) or on written supports. Jāmī, for example, based a large part of his works on the imitation of past models, as in the Bahāristān (“The Spring Garden”), which he presents in the preface as an imitation of the Gulistān (“Rose Garden”) of Saʿdī, composed shortly after the Bustān.Footnote 50 The similarities between the Bahāristān and the Gulistān are limited to formal aspects. They both consist of a prosimetrum, a text mixing prose and poetry. They have the same outline, deploying eight chapters, and both use in their titles the image of the garden to characterize their structure. Thematically and stylistically, they remain, however, quite different. While the Gulistān combines anecdotes and aphorisms of both secular and religious content, the Bahāristān belongs to the genre of the taẕkīrāt, a collection of biographies. It is composed of a series of portraits of saints and Sufis, philosophers and poets.

Very often, in these practices of javāb, just as in the Muntakhab, the new version would present a mystical twist. Another example is the story of Yūsuf u Zulaykhā, rewritten by Jāmī as a mystical ma![]() navī. In Arabic and Persian traditions, the story usually relies on the Qur’anic version, in which Zulaykha personifies the temptation of sin while Yusuf represents the ideal believer, who resists sinning for fear of God.Footnote 51 In Jāmī’s version, by contrast, Zulaykha is a positive character.Footnote 52 She stands for the Sufi seeker who, in their initiatory journey, must wrestle with the inaccessibility of the beloved, personified by Yusuf. The love affair between Zulaykhā and Yūsuf becomes a spiritual quest, in which Yūsuf personifies God while Zulaykhā stands for the Sufi seeker. Zulaykhā’s earthly love is thus “a manifestation of love for God” and her lust a desire for knowledge and truth, as Gayane Merguerian and Afsaneh Najmabadi have written.Footnote 53

navī. In Arabic and Persian traditions, the story usually relies on the Qur’anic version, in which Zulaykha personifies the temptation of sin while Yusuf represents the ideal believer, who resists sinning for fear of God.Footnote 51 In Jāmī’s version, by contrast, Zulaykha is a positive character.Footnote 52 She stands for the Sufi seeker who, in their initiatory journey, must wrestle with the inaccessibility of the beloved, personified by Yusuf. The love affair between Zulaykhā and Yūsuf becomes a spiritual quest, in which Yūsuf personifies God while Zulaykhā stands for the Sufi seeker. Zulaykhā’s earthly love is thus “a manifestation of love for God” and her lust a desire for knowledge and truth, as Gayane Merguerian and Afsaneh Najmabadi have written.Footnote 53

It seems, in fact, that Jāmī largely contributed to the reception of Saʿdī as a mystical poet. Saʿdī is indeed portrayed as a Sufi guide in Jāmī’s ma![]() navī entitled Subḥat al-abrār (“The Rosary of the Pious”). This ma

navī entitled Subḥat al-abrār (“The Rosary of the Pious”). This ma![]() navī consists of forty sections in which moral discourses are accompanied by anecdotes. The third section deals with versified speech and its divine nature. It includes verses on the inability of language to describe divine action as well as on the mystical function of poetry. The anecdote illustrating this paradoxical discourse is centered on Saʿdī. A Sufi mystic dreams of Saʿdī being rewarded by angels for a verse in which he praises God.Footnote 54 Saʿdī’s literary production is therefore cast as mystical poetry, a shift in Saʿdī’s reception that is paralleled in the Muntakhab, where the multifaceted Bustān is given mystical inflections.

navī consists of forty sections in which moral discourses are accompanied by anecdotes. The third section deals with versified speech and its divine nature. It includes verses on the inability of language to describe divine action as well as on the mystical function of poetry. The anecdote illustrating this paradoxical discourse is centered on Saʿdī. A Sufi mystic dreams of Saʿdī being rewarded by angels for a verse in which he praises God.Footnote 54 Saʿdī’s literary production is therefore cast as mystical poetry, a shift in Saʿdī’s reception that is paralleled in the Muntakhab, where the multifaceted Bustān is given mystical inflections.

Patterns of Circulation

These compilations seem to have circulated during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in different parts of the Persianate world. The mirror-for-princes Muntakhab was copied in courtly milieus of western Iran and Turkey, while the second Muntakhab seems to have been more frequently copied in Timurid and post-Timurid Khurasan and Transoxiana.

The princely status of the mirror-for-princes Muntakhab is enhanced in the manuscripts by at least four aspects: the presence of a dedication to a royal patron, the signature of celebrated artists, the addition of paintings illustrating courtly scenes, as well as the manuscripts’ circulation and transformation in princely workshops. The group’s first manuscript is dedicated to the Aq Qoyunlu ruler Sulṭān Khalīl (d. 833/1478) as stated in the double shamsa opening the book.Footnote 55 The manuscript remained unfinished: the paintings were not completed until later and the copy lacks a colophon. As Abolala Soudavar has suggested, it is possible that its making was interrupted by Sulṭān Khalīl’s death in 833/1478 and that it was made in Tabriz, after Sulṭān Khalīl had just succeeded to his father Uzun Ḥasan (r. 861/1457–882/1478).Footnote 56 Soudavar also attributes the copying of the manuscript to the famous calligrapher ʿAbd al-Raḥīm Khvārazmī, who produced several manuscripts for the Aq Qoyunlus.Footnote 57

It is no surprise that such a copy was produced for Sulṭān Khalīl, for it is consistent with the interest of the Aq Qoyunlus in the “mirrors” genre, as evidenced by their commissioning of the Akhlāq-i Jalālī (“Ethics of Jalāl”), a mirror for princes written by Jalāl al-Din Davānī (830/1427–980/1502).Footnote 58 This book was composed after the model of Naṣīr al-Dīn Ṭūsī (d. 672/1274), the Akhlāq-i Nāṣīrī (“Ethics of Naṣīr”), written in 633/1235. At the core of both books lie the four cardinal virtues of the king: ḥikmat (wisdom), shajāʿat (courage), ʿiffat (modesty) and ʿadālat (justice), which are also emphasized in the Muntakhab.Footnote 59

Sulṭān Khalīl was, moreover, particularly appreciative of the Bustān’s aphoristic verses, some of which he encountered as epigraphic inscriptions on Darius’ palace in Persepolis. The event is reported by the same Jalāl al-Dīn Davānī in a text called the ʿArżnāma (“Account of the Parade”).Footnote 60 While in Fārs, Sulṭān Khalīl went to Persepolis to complete a military review. During his visit, he discovered the inscriptions left on the ruins of Darius’ palace by the Inju ruler Abū Isḥāq b. Maḥmūd and the Timurid prince Ibrahīm Sulṭān.

After the fall of the Aq Qoyunlus, the manuscript of Sulṭān Khalīl was taken to the early Safavid capital of Tabriz in the first half of the sixteenth century. A double illustrated frontispiece and a painting were added at the Safavid workshop.Footnote 61 Showing scenes of courtly entertainment, the frontispiece clearly reflects the princely setting in which this Muntakhab was intended to be shared. The manuscript then traveled to the Ottoman Empire, for it also contains an Ottoman drawing. The picture was added on the verso of the last folio of text. It is executed in gold and consists of a vegetal composition in the saz style, featuring serrated leaf foliage.Footnote 62

The rest of this group’s manuscripts confirms the transmission of this compilation in the royal courts of western Iran and Turkey. They include a Safavid copy signed by the calligrapher Shāh Maḥmūd al-Nīshāpūrī (d. 972/1564–65), one of the most celebrated artists of the court of Shāh Ṭahmāsp (d. 984/1576).Footnote 63 This manuscript opens with a double frontispiece illustrating courtly scenes.Footnote 64 Another example of this Muntakhab was produced around 1530 and has been attributed by Francis Richard to Ottoman Turkey.Footnote 65 Finally, one should mention a copy made in Shamākhī in the region of Shirvān in 1539 and signed by the calligrapher ʿAbd al-Laṭīf Muẕahhib.Footnote 66

In contrast, the manuscript copies of the second Muntakhab were mostly diffused in Khurasan and Transoxiana. Such diffusion reflects the literary and spiritual trends of these regions, which were largely marked, as mentioned above, by a taste for rewriting, as well as an interest in bridging the mundane and the metaphysical, as noted by Ingenito and others.Footnote 67

The first known copy of the mystical Muntakhab is dated 907/1502 and was produced in the region of Bākharz in Khurasan.Footnote 68 The double frontispiece opening the book shows gatherings of scholars, rather than courtly assemblies (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Risāla [Intikhāb-i Bustān], 907/1502, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA, accession no. 1960.64, fols. 1b–2a (photograph by the author).

Other copies were made in Herat at the beginning of the sixteenth century. It is interesting to note that the famous calligrapher Muḥammad Qāsim b. Shādīshāh was responsible for copying of two of these Muntakhab. The first one appears in a larger anthology (Majmūʿa) executed in Herat in 930/1523–24. The book also contains selections from other texts (Khusraw u Shīrīn of Niẓāmī Ganjavī, Subḥat al-Abrār of Jāmī, the Ma![]() navī of Rūmī, the Khamsa of Niẓāmī and the Ḥadīqat al-Ḥaqīqa of Sanāʾī).Footnote 69 It opens with a preface that presents the content of the anthology. Several calligraphers from Herat were involved in its making, including ʿAlī al-Ḥusaynī, Muḥammad Qāsim b. Shādīshāh, Sulṭān Muḥammad Khvandān and Muḥammad Nūr. In fact, as indicated by Dust Muḥammad in his preface to the album of Bahrām Mīrzā written in 951/1544–45, these artists belonged to the same lineage of calligraphers and were linked through master‒pupil relationships.Footnote 70 Next, a painting marks the transition from the preface to the compilations.Footnote 71 Inscribed in a circular frame, it represents an old man and his disciple. This iconography plays a double role: it reflects the pedagogical and spiritual relationships between the calligraphers involved in the making of the book while announcing the Sufi vein of the texts enclosed in the anthology.

navī of Rūmī, the Khamsa of Niẓāmī and the Ḥadīqat al-Ḥaqīqa of Sanāʾī).Footnote 69 It opens with a preface that presents the content of the anthology. Several calligraphers from Herat were involved in its making, including ʿAlī al-Ḥusaynī, Muḥammad Qāsim b. Shādīshāh, Sulṭān Muḥammad Khvandān and Muḥammad Nūr. In fact, as indicated by Dust Muḥammad in his preface to the album of Bahrām Mīrzā written in 951/1544–45, these artists belonged to the same lineage of calligraphers and were linked through master‒pupil relationships.Footnote 70 Next, a painting marks the transition from the preface to the compilations.Footnote 71 Inscribed in a circular frame, it represents an old man and his disciple. This iconography plays a double role: it reflects the pedagogical and spiritual relationships between the calligraphers involved in the making of the book while announcing the Sufi vein of the texts enclosed in the anthology.

The second Muntakhab copied by Muḥammad Qāsim b. Shādishāh is contained in a freestanding manuscript that underwent multiple changes over time.Footnote 72 The calligraphy was executed in 933/1526–27, probably in Herat, before the double illustrated frontispiece and two paintings were completed a few decades later, perhaps in the city of Mashhad.Footnote 73 Just like the preceding examples, the frontispiece shows an assembly of scholars. The self-reflexivity of the painting is further highlighted by the representation, in the middle of the composition, of a book toward which the characters’ attention seems to converge.

The Muntakhab was diffused even further East, as evidenced by a copy executed by Mir Ḥusayn al-Ḥusaynī, probably in Bukhara around 1550.Footnote 74 This calligrapher is known to have produced several manuscripts for Uzbek rulers, including a copy of the complete Bustān of Saʿdī executed in Bukhara in 938/1531 for Abū al-Ghāzī Sulṭān ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz Bahādur.Footnote 75 The illumination and the paintings are also refined examples of Uzbek book arts. The book opens with a double illustrated frontispiece showing a prince and a shaykh in a courtly setting, a theme that emphasizes again the mystical tenor of this particular Muntakhab.Footnote 76

In Conclusion

Compilations of the Bustān prove to be an important tool in the study of the Bustān’s reception. Generally, they show that the Bustān was received as a flexible text, a platform for literary and artistic adaptations. Through operations of selection and juxtaposition, the compilations foreground themes that might otherwise seem secondary in the complete Bustān. While the complete Bustān can be approached as a didactic ma![]() navī destined to a great variety of audiences, the compilations narrow the moral content of the Bustān to specific interests, thus altering the Bustān’s genre. More tightly focused on the life and rule of kings, the first compilation resembles a mirror for princes. Meanwhile, the second compilation privileges mystical verses that resonate with aspects of Sufi erotic theology.

navī destined to a great variety of audiences, the compilations narrow the moral content of the Bustān to specific interests, thus altering the Bustān’s genre. More tightly focused on the life and rule of kings, the first compilation resembles a mirror for princes. Meanwhile, the second compilation privileges mystical verses that resonate with aspects of Sufi erotic theology.

The selections do not simply summarize the Bustān, since they each leave out major thematic and formal aspects, including the self-reflective quality of the Bustān, as well as its humor and irony, which often upend the poem’s moralizing tendencies. In contrast with the complete Bustān, the selections, moreover, present a limited set of themes, while projecting a certain generic consistency. By highlighting certain stories and ideas at the expense of others, and by ordering verses in a way that differs from Saʿdī’s order, the acts of selecting and juxtaposing transform Saʿdī’s text, in effect creating a different, more homogeneous composition. Even though all verses come from the Bustān of Saʿdī, because they are severed from their original context and reshuffled they produce a different literary experience. The act of selecting “disintegrates the text and detaches [it] from context,” to use Antoine Compagnon’s assessment of the act of quoting.Footnote 77

In a way, the selections reveal an effort to actualize the Bustān of Saʿdī. As Yves Citton has suggested, an actualizing reading seeks to adapt the original text to contemporary taste, instead of trying to uncover the original meaning or the author’s intentions, thus deliberately fashioning an anachronistic interpretation of the source.Footnote 78 The selections also conjure up the notion of rewriting, defined by André Lefevere as “the adaptation of a work of literature to a different audience, with the intention of influencing the way in which that audience reads the work.”Footnote 79 While the selections do not literally rewrite the poem of Saʿdī since all verses come from the Bustān, through the poetics of juxtaposition, as in a collage, they do adapt the Bustān to certain interests, thus influencing its reception or at least reflecting the preferences of particular audiences.

How then to further define and conceptualize the relation of the compilations to the complete Bustān? This question would deserve a full study by itself. As a conclusion, I will restrict myself to a few more remarks. Each compilation of the Bustān seems to engage with the complete poem of Saʿdī using a distinct hypertextual technique, to borrow Gérard Genette’s terminology: each selection derives from and thus refers to—and transcends—the Bustān, its hypotext, in a different way.Footnote 80 In the first Muntakhab, proverbs were picked from the Bustān and assembled so as to form a book of wisdom, an abridged version of the mirror for princes that runs through the Bustān. While analogous to the complete Bustān in terms of its thematic emphasis on advice, the compilation stands out formally not as a ma![]() navī but as a collection of sayings, a sort of pandnāma addressed to kings and rulers. As such it uses a technique similar to quotation: reflecting themes essential to the Bustān while altering its literary form.

navī but as a collection of sayings, a sort of pandnāma addressed to kings and rulers. As such it uses a technique similar to quotation: reflecting themes essential to the Bustān while altering its literary form.

The transformation that has led to the second Muntakhab is different. The formal conventions of the ma![]() navī were repeated. But in pushing secondary themes to the fore, including the homoeroticism of Sufi spirituality, the second Muntakhab diverts the content of the complete Bustān toward mysticism. As such it can be compared to a transposition, separating the form of the work from its spirit, and investing the content with a different meaning.Footnote 81 The selections thus constitute a pair of symmetrical and inverse transformations—the first says a similar thing differently while the second says another thing similarly. In the first case, the compiler transformed the Bustān’s form while leaving the subject rather intact—as intact as the formal transformation from ma

navī were repeated. But in pushing secondary themes to the fore, including the homoeroticism of Sufi spirituality, the second Muntakhab diverts the content of the complete Bustān toward mysticism. As such it can be compared to a transposition, separating the form of the work from its spirit, and investing the content with a different meaning.Footnote 81 The selections thus constitute a pair of symmetrical and inverse transformations—the first says a similar thing differently while the second says another thing similarly. In the first case, the compiler transformed the Bustān’s form while leaving the subject rather intact—as intact as the formal transformation from ma![]() navī to pandnāma allows; in the second case, the compiler borrowed the form of the ma

navī to pandnāma allows; in the second case, the compiler borrowed the form of the ma![]() navī while emphasizing secondary themes, diverting the Bustān from its original purpose.

navī while emphasizing secondary themes, diverting the Bustān from its original purpose.

Literary reception was, moreover, tightly linked to material practices, as the Bustān was copied, circulated, anthologized, and illustrated. Paintings were used within the selections to further assert certain readings, as shown in the last section of this paper. One might also expand this idea to the use of paintings in complete copies of the Bustān. Such hypothesis would require further research, but as a way to open up the discussion, I will finish this article with one last example. The calligrapher Shāh Qāsim b. Shādishāh mentioned earlier, who made at least two copies of the mystical Muntakhab, also produced two copies of the complete Bustān. One of them contains a painting that illustrates, for the first time in our knowledge, the story of the physician from Marv analyzed above and which appears in the Muntakhab’s introduction (Figure 4).Footnote 82 The painting selects a story that was itself selected in the Muntakhab, hence signaling, within the complete version of the Bustān, the presence of the Muntakhab.

Figure 4. Bustān, ca. 1525, Art and History Trust collection, accession no. 73, fol. 72b (photograph by the author).

The intertextual dimension of this pictorial choice is further enhanced by the architectural epigraphy represented in the painting. Quoting a verse by Āṣāfī, the inscription features a lover who complains to his beloved about the absence of a remedy for unrequited love. This quotation complements the content of the image and its surrounding text by foregrounding the theme of mystical love. Painting and epigraphy, in sum, act like a muntakhab: a lens emphasizing a particular reception of the Bustān.