1 Introduction

A lack of vocabulary has been considered a major factor that makes writing in a foreign language difficult (Leki & Carson, Reference Leki and Carson1994). As H. Yoon (Reference Yoon2008) notes, the mastery of lexical and grammatical accuracy can contribute to an increase in self-confidence and a possible improvement in the overall writing quality of L2 writers. To enhance L2 learner writing performance, a corpus approach has been regarded as a viable way to help learners with lexico-grammatical patterns (Coxhead & Byrd, Reference Coxhead and Byrd2007; Flowerdew, Reference Flowerdew2010; Tribble, Reference Tribble2009; C. Yoon, Reference Yoon2011). This study attempts to examine in what ways DDL activities help learners improve lexico-grammatical patterns in L2 writing. A set of paper-based concordance activities was developed around a topic-specific corpus. Students were directed to observe the concordance lines and explore the collocations of five target abstract nouns. The lexico-grammatical uses of these five words in the students’ essays were then analysed and compared between the two groups (inter-subject comparison) and within the experimental group (intra-subject comparison).

2 Application of corpora in second language writing: A critical review

Over the past decade, corpora have become increasingly important for L2 writing instruction as teaching has become less a practice of imparting knowledge and more one of providing opportunities for learning (Hyland Reference Hyland2003). There are two possibilities for incorporating corpora into the L2 writing classroom (Römer Reference Römer2008; Tribble & Jones Reference Tribble and Jones1997). One possibility is for teachers to examine a corpus and determine the most frequent words or patterns of a target genre, then design teaching materials based on their observations. The other is for students to use a concordancer to explore the corpus themselves. The focus of academic discussions and practical corpus application has shifted from the first possibility (indirect uses via teachers) to the second (direct uses by learners in the classroom). Research on learners’ direct use of corpora in language learning has witnessed an increase over the past two decades since Johns (Reference Johns1991) advocated DDL in language teaching and learning. In general, the DDL studies on L2 writing can be placed into three categories according to the different stages where the actual use of corpora by the students takes place, that is, before, during, and after writing. Among these studies, some focus on the students’ evaluations of corpus use in writing (H. Yoon & Hirvela, Reference Yoon and Hirvela2004; Gaskell & Cobb, Reference Gaskell and Cobb2004; H. Yoon, Reference Yoon2008), which have highlighted issues in need of further research when learners consult corpora as a resource in the writing process. Some are theoretically-based and descriptive, with a focus on how to incorporate corpora into L2 writing (Bernardini, Reference Bernardini2002; Lee & Swales, Reference Lee and Swales2006; Thurstun & Candlin, Reference Thurstun and Candlin1998; Tribble, Reference Tribble1997, Reference Tribble2001, Reference Tribble2002; Weber, Reference Weber2001); others examine the effects of corpus use by learners as a consultation skill for error correction in revising their drafts (Chambers & O’Sullivan, Reference Chambers and O’Sullivan2004; O’Sullivan & Chambers, Reference O’Sullivan and Chambers2006; H. Yoon, Reference Yoon2008) or for learning particular types of linguistic points in writing, such as connectors (Cresswell, Reference Cresswell2007), conjunctions (Tseng & Liou, Reference Tseng and Liou2006), or reporting verbs (Bloch, Reference Bloch2009). Using corpora helps learners to become more effective learners in terms of vocabulary and associated grammar and usage (Coxhead, Reference Coxhead2000; Coxhead & Byrd, Reference Coxhead and Byrd2007; Thurstun & Candlin, Reference Thurstun and Candlin1997; Tribble, Reference Tribble2002).

Despite the benefits of corpus use for language teaching and learning, limitations and challenges in the application of corpora in the classroom have also been reported. Pérez-Paredes, Sánchez-Tornel, Alcaraz Calero and Aguado Jiménez (Reference Pérez-Paredes, Sánchez-Tornel, Alcaraz Calero and Aguado Jiménez2011) and Pérez-Paredes, Sánchez-Tornel and Alcaraz Calero (Reference Pérez-Paredes, Sánchez-Tornel and Alcaraz Calero2012) explored learners’ search behaviour when learners directly accessed corpora during focus-on-form activities. The researchers point out that careful consideration should be given to cognitive aspects concerning the initiation of corpus searches and the role of the search interface. These studies have provided a valuable framework to understand how corpora can be utilized to enrich learning resources in L2 writing instruction or used as a reference tool for enhancing writing skills.

Since vocabulary teaching and writing are two inter-related areas, it is worth reviewing empirical research on corpus use for vocabulary learning here. Stevens (Reference Stevens1991) is the pioneer in conducting the first controlled experiment investigating the effectiveness of learners’ consultation of corpus printouts. In his study, a group of university students were directed to provide a known word to fill a gap in a text, which was either a single gapped sentence or a set of gapped concordances. The results of the learners’ performance in these two sets of exercises showed that they retrieved words from memory more successfully when doing the concordance-based exercises.

Cobb (Reference Cobb1997) extended Stevens’ (Reference Stevens1991) research by setting up a comparative study with a control group and an experimental group to examine whether online concordance exercises were more effective for vocabulary acquisition than traditional vocabulary exercises. In the experiment, a suite of CALL-type activities, with a modified concordance as their main information source, was designed and tested with more than 100 learners over an academic term; the control group used a set of traditional vocabulary learning materials. The results of the weekly quizzes over the academic semester confirmed that the online concordance exercises were more effective for students’ vocabulary acquisition than the traditional materials.

Boulton (Reference Boulton2008, Reference Boulton2010) examined and discussed the effects of DDL, in particular paper-based concordance materials, in vocabulary learning for low-proficiency English learners. Boulton (Reference Boulton2008) pointed out the advantages of using printouts of concordance lines in the classroom. In Boulton (Reference Boulton2010), the researcher investigated 62 low-proficiency level learners coping with paper-based corpus exercises and a DDL approach in comparison with traditional teaching materials. Fifteen problematic language items were selected from students’ written productions, and two sets of teaching materials were distributed to the students. One set included concordance materials of the target items while the other had traditional materials retrieved from dictionary entries. The outcomes of a post-test on these fifteen problematic items show that corpus-based exercises helped students learn the language more efficiently than the traditional learning materials did.

The above studies have provided useful insights into how corpus use, especially concordances, can help learners to gain broader and deeper vocabulary knowledge. Although it is reported that the DDL approach helped learners achieve a better score in the vocabulary tests than the traditional learning activities did, the outcomes of using the target words in their written products have not yet been extensively investigated, thus leaving ample room for further empirical research to examine the effects of corpus-based learning in this regard.

3 Research questions

The present study was designed to investigate the effects of DDL on vocabulary use in L2 writing by comparing the writing outcomes of a control group and an experimental group. Two research questions are addressed:

1. Can paper-based DDL improve L2 learners’ lexico-grammatical use of abstract nouns in their writing?

2. Do L2 learners think that paper-based DDL helps their vocabulary use in L2 writing?

4 Method

4.1 Paper-based DDL activities

A topic-specific corpus consisting of texts related to gambling and the lottery was compiled using texts obtained from reputable online English news websites, as well as from the Louvain Corpus of Native English Essays (LOCNESS).Footnote 1

Following the text-collecting approach suggested by Nelson (Reference Nelson2009), three English news websites that contained quality articles on the desired topics were identified: the BBC News, the Guardian, and the New York Times. A search for the key words gambling and lottery on these websites was carried out and the relevant articles were downloaded.

The other source was a sub-corpus of opinion essays on the topic of the national lottery written by the British students in the LOCNESS corpus. In this corpus, each text consisted of approximately 500 to 600 words. Twelve articles were selected, identified as samples of good writing by an experienced native English teacher of writing, who was also a writing examiner for the International English Language Testing System (IELTS). Any language errors or typos in these texts were corrected before they were included in the corpus. Although it could be argued that essays written by native English students may not be a suitable or reliable source for teaching English writing, it should also be noted that these revised texts from LOCNESS could be deemed appropriate as they deal with the same subject field of the writing task in this study.

Next, with the aid of the web-based corpus analysis tool Wmatrix (Rayson Reference Rayson2002), a keyword list was generated using the British National Corpus (BNC) as a reference corpus. Target words were selected according to two criteria: frequency of occurrence in the topic-based corpus (each word occurs at least three times), and abstract nouns often used in opinion essays (Read Reference Read2004). Based on these two criteria, five words were chosen. They were controversy, criticism, objection, situation, and effect. About ten concordance lines of each target word were then selected and presented in the corpus-based activities.

4.2 Participants

Forty third-year university students majoring in English for Business Purposes at a University in South China participated in this study. Their overall English proficiency level was upper-intermediate according to the Oxford English Placement Test. The participants were randomly assigned to a control group or an experimental group, each with twenty students. A writing test conducted before the experiment showed no statistically significant difference in English writing competence between the two groups according to the independent samples t-test (p>.05).

4.3 Procedure

The study was held in the context of an English writing workshop. The writing task chosen for the study was argumentative writing, which is a regular and traditional writing task required for university students in mainland China. Each session of the writing workshop lasted 80 minutes. In order to minimize the impact of unwanted variables, all sessions were instructed by the same teacher, and the students were given the same textbook and writing assignments.

The two groups took three writing tests: a pre-test, an immediate post-test, and a delayed post-test. Each writing test lasted 60 minutes. In week 1, a pre-test was taken by both groups. They wrote an argumentative essay on the impact of the tourist industry, and were directed to use the five target words in their writing (controversy, criticism, objection, situation, and effect).

In week 2, both groups took the immediate post-test, writing an opinion essay on the lottery. All the participants were required to use the same five nouns as in the pre-test in their writing. Before the students took the immediate post-test, both groups were given a lead-in article related to the writing topic of “the lottery”. The control group read the article, brainstormed the topic for five minutes, studied the five words by consulting dictionaries (the traditional reference tool), and was then directed to write an opinion essay. The most popular dictionary used by the students was the Oxford advanced learner’s English-Chinese dictionary (4th edition).

The experimental group undertook the same activities as the control group. However, instead of dictionary consultation, they were given a set of concordance materials to observe the patterns of the target words. The material consisted of five sets of concordance lines, each highlighting the keyword in the centre (see Appendix 1). During the prewriting stage, the teacher had no contact with the two groups, other than to hand out the materials.

In week 4, both groups took a delayed post-test, writing an opinion essay on gambling. In this task, no words were provided in the writing prompt or required to be used in the students’ essays. The task was conducted in this manner in order to investigate how many words from the concordance activities were used again in the delayed post-test after a two-week interval and how these words were used in the two groups’ written texts. Following the delayed post-test, anonymous questionnaires (see Appendix 2) were given to the experimental group during the class to evaluate the DDL activities.

4.4 Data analysis

Two sets of data were analysed to investigate the effects of the DDL activities on learners’ writing: (1) student essays, and (2) descriptive data obtained from students’ questionnaire responses and their learning journals. Two native English teachers evaluated the students’ use of the target nouns by categorizing them on a 3-point scale: appropriate, less appropriate, and inappropriate (see Table 1). The use of the nouns falling into the categories of “less appropriate” and “inappropriate” were characterized as errors.

Table 1 Appropriacy scale

In addition to the analysis of the use of the five nouns, students were surveyed for their views on the DDL activities in L2 writing. The responses to the Likert-scale questionnaires in each category were summated and treated as interval data. The means and standard deviations were calculated using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 17.0). In order to enhance the presentation of the questionnaire data, students’ responses were coded into three categories, “helpful”, “not helpful”, and “no opinion” by placing all the positive answers (5 “somewhat agree”, 6 “agree”, and 7 “strongly agree) into the “helpful” category, and all negative answers (1 “strongly disagree”, 2 “disagree”, 3 “Somewhat disagree”) into the “not helpful” category. Students in the experimental group were also instructed to write a learning journal in English after the experiment to comment on the DDL activities and provide suggestions for improving the activities.

5 Results

5.1 Accuracy

Error-free ratios between groups and the improved use of the abstract nouns within the experimental group were compared. In the pre-test, the control group and the experimental group had similar error-free ratios in terms of the use of the five target nouns (40% and 38% respectively). However, in the immediate post-test, the experimental group’s error-free ratios increased to 88% while the control group’s error-free ratios only increased to 47%.

The use of the target nouns by the experimental group was further investigated and categorized into three types: positive change, negative change, and no change. “Positive change” was described as inappropriate or less appropriate use of the nouns in the pre-test, but appropriate use in the immediate post-test. “Negative change” was appropriate use of the nouns in the pre-test but less appropriate or inappropriate uses in the immediate post-test; and “no change” was described as inappropriate or less appropriate use of the nouns both in the pre-test and the immediate post-test. Overall, the instances of positive change (42 in total) outnumbered negative change (3) and no change (6). Table 2 shows examples of each category.

Table 2 Examples of positive change, no change, and negative change

5.2 Complexity

Lexico-grammatical patterns of the nouns in the immediate post-test were compared between the control group and the experimental group. As shown in Figure 1, all the target nouns except effect were used in a greater variety of grammatical patterns by the experimental group than by the control group. The grammatical patterns of effect were equal in the two groups, falling into two types: (1) V+effect (by collocating cause and have); and (2) effect+copular verb BE as subject (e.g. Another negative effect is that lottery games have caused many crimes).

Fig. 1 Distribution of lexico-grammatical patterns in the immediate posttest

Although only two types of grammatical structures of effect were found in the students’ texts, the experimental group tended to use varied adjectives to modify effect (e.g. its harmful effects, a terrible effect, the serious effect, a significant effect, another negative effect, the potential harmful effects, and numerous positive effects), while the control group only used a limited number of premodifiers (e.g. the bad effect, a good effect, many big effects, and greater effect).

In contrast to the use of effect, the lexico-grammatical patterns of the other four target nouns (controversy, objection, criticism, and situation) are noticeable as more syntactic variations were observed in the experimental group. Due to space limitations, examples of two nouns (controversy and situation) are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3 Lexico-grammatical patterns of controversy in the immediate posttest

* Referring to the inappropriate and less appropriate use of the Ns.

Table 4 Lexico-grammatical patterns of situation in the immediate posttest

* Referring to the inappropriate and less appropriate use of the SNs.

As illustrated in Table 3, the most common lexico-grammatical pattern found in the control group was controversy used as a subject complement in the grammatical structure: there+copular verb BE +a controversy. This pattern was used by about two thirds of the students. Lexical verbs such as provoke, face, and stir were absent in the control group. Apart from this, there was only one attempted use of passive voice in the control group (A controversy is put into heat discussion), which was unsuccessful because the student used an inappropriate verb put to collocate with controversy. In contrast, the experimental group was more resourceful in using controversy, as evidenced by the variety of lexical verbs (e.g. provoke, cause, face, stir, trigger, and raise) used to collocate with controversy. Also, they made improvements in terms of grammatical accuracy. To a large extent, the experimental group appeared to outperform the control group in both areas of syntactic variations and correct grammar use.

A remarkable difference in the use of situation between the two groups is the variety of grammatical structures (see Table 4). The control group used situation in only two structures: (1) N+V (e.g. the situation will become more serious); and (2) Prep+N (situation embedded in a PP which functions as an adverbial, e.g. in this situation, welfare lottery is no more a good thing). In comparison, the experimental group used two additional structures: (1) V+N (e.g. worsen the situation; exacerbate the situation); and (2) Prep+N (where the PP functions as an object complement, e.g. Lottery will leave some people in situation of risk).

Another noteworthy grammatical structure was the NP pattern. NPs headed by the target word were classified into two types: (1) premodifier+N; and (2) N+postmodifier. On the whole, in terms of frequency, the experimental group showed more variety of NP patterns than the control group. The control group tended to use determiners as premodifiers to collocate with the target nouns, such as the possessive articles my and their, the definite article the, the indefinite articles a and an, and the referential pronoun this. The adjectives modifying the nouns were also limited in number, such as bad, good, heated and great. The patterns in the experimental group presented a more complex picture. The most salient difference from the control group was the greater variety of adjectives used to modify the target nouns, such as numerous and enormous to precede controversy; strong and considerable to quantify objection; intense and main to modify criticism; desperate and complicated to describe situation; and harmful and significant to modify effect. These adjectives were more formal than those observed in the control group (good, bad, and great), which seem more appropriate in argumentative essays.

In terms of the N+postmodifier patterns, the two common postmodifiers were prepositional phrases and zero relative clauses. As can be seen in Table 5, more appropriate prepositions were found in the experimental group than the control group. The experimental group also used more varied N+postmodifier patterns. For instance, the usage of controversies followed by surrounding was presented in the concordance activities, and a number of students in the experimental group seemed to notice this pattern and use it in their own written output, whereas such a usage was not observed in the control group.

Table 5 Patterns of N+postmodifier in the immediate posttest

* Referring to the inappropriate and less appropriate use of the Ns.

In the delayed post-test, 54 occurrences of the target nouns were found in the experimental group while there were only 10 in the control group (see Table 6). Moreover, students in the experimental group were quite accurate in retaining the lexico-grammatical patterns of these target words.

Table 6 Occurrences and errors of the target words in the delayed post-test

The errors made in the delayed post-test by the experimental group were mainly prepositional errors. For example, one student wrote the controversy of the legality of gambling has been provoked in China, and another student wrote I have objection of gambling – both students repeating the errors made in the pre-test.

5.3 Evaluation of the DDL activities

The follow-up survey focused on two aspects of the students’ attitudes towards the corpus-informed activities: (1) an evaluation of DDL activities on vocabulary learning; and (2) the difficulties in doing the concordance activities. As shown in Table 7, the mean scores of students’ views on vocabulary learning clustered in the 5.50–6.30 score range, indicating that, overall, the majority of the students evaluated the DDL activities as helpful resources for acquiring collocational and grammatical patterns, memorizing the usage of the words, and the incidental learning of new words.

Table 7 Perceived effects on vocabulary learning (n=20)

* 1–3=disagree, 4=no opinion, 5–7=agree.

The average score regarding collocation learning (6.30) ranked top among the categories. All 20 students agreed that the concordance activities helped them acquire the collocational patterns of the target words. As one student commented in the learning journal:

Using the collocations [learned] from the vocabulary exercise also enables me to have a rich expression. Take controversy as an example, I used to use “have controversy” and this seemed to be dull. However, through the vocabulary exercise, now I know more usages like “provoke/reignite controversy”, which could polish my writing better.

In addition to improving lexical collocations, many students concurred that corpus-based activities helped them with the acquisition of prepositional colligations:

To be honest, most the words offered are known to me, but I merely have vague ideas of them, such as just the Chinese meanings. Actually I was not sure about the exact prepositions that follow the words. Take controversy for example, I always use “of” as its preposition and seldom have I used “about” or “over”. [As a] matter of fact, the “of” is inappropriate to well express the meaning of reasons for “controversy” while only either “about” or “over” can do. So the exercises can help us to know more about the words and help us to use prepositions in a correct way.

It also raised the students’ awareness of the importance of collocations:

After doing the exercise, I know the common usage of the word and the phrases the word often collates. In this way, I can have a good command of these words and my essay would be [more] academic if I know the collocation. In the future reading and writing, I will pay more attention to the collocation[s].

With regards to memorizing the usage of the words, about 90% of the students thought that reading concordances was somewhat helpful while 10% believed that it was unhelpful. The reason why some did not consider it useful for this can be seen in the following extract from one student’s learning journal:

As far as I am concerned, it did help me in some way, but the help is little. The vocabulary exercises is really a good way to improve our writing skill because it shows how to use a word in different ways and help us to know more about the word even though some words we have been familiar with. However, it does not help us very much. To learn a lot of different usage of words is a good thing, but to remember all of these usage[s] in a short time is really a challenge to me, let alone put to use [in writing] at once.

Another student remarked, “I think it helps not so much because I cannot memorize them when I want to use it in my writing. I need to refer [to] the exercise if I intend to use the new collocations.”

Although the majority of the students had a favourable attitude towards corpus use for vocabulary learning in L2 writing, Table 8 reveals a different perspective, with 75% of responses showing that it was time-consuming to do this form of activities. As one student wrote, “I think there are too [many] contents which cost our lots of time. It would be better if there is less exercise or we just [under]line the answer in the content and not need to write it out”. Half of the students reported that they did not have difficulty in formulating the overall rules for the words.

Table 8 Problems in doing the DDL activities (n=20)

* 1–3=disagree, 4=no opinion, 5–7=agree.

However, about 80% of the students reported experiencing difficulty in doing the concordance activities due to the incomplete contexts and the new words in concordances. The incomplete contexts hampered them in fully understanding the concordance output:

The examples of the words using are not so perfect because some of them are just a part of a sentence, and we don’t know what the whole meanings of the examples are. So these examples cannot well express the exact using of the words. Some of them just show the verbs or prepositions that can be used with them.

The incomplete contexts are one of the main reasons for some students stating that topic-based concordance lines failed to provide them with ideas related to the writing topic. The students commented that it would be of help for them to grasp the ideas more thoroughly if they could go further into the full context of the target word and read the complete sentences or even the whole paragraph.

6 Discussion

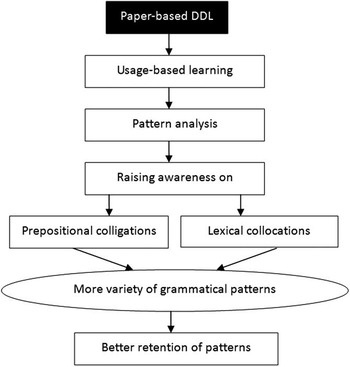

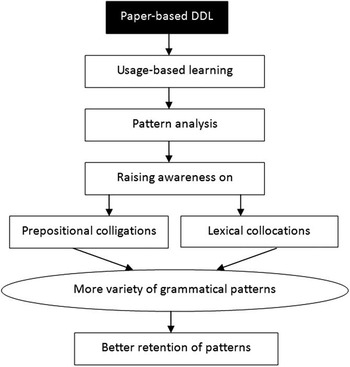

The improved use of the target words in the students’ writing along with the survey confirmed previous research (e.g. Boulton Reference Boulton2009, Reference Boulton2010) that DDL can be an effective approach to helping learners obtain and retain lexico-grammatical patterns. As illustrated in Figure 2, introducing DDL activities in the L2 writing classroom allows learners to study the target language through a usage-based learning approach (Langacker Reference Langacker2000), which encourages instance-based or exemplar-based learning. Its effects are twofold: first, it helps learners notice and acquire collocational patterns; second, the acquisition of collocational patterns in turn enables learners to generate more accurate and complex syntactic patterns, and have a better retention of the acquired patterns.

Fig. 2 Effects of DDL on the acquisition of lexico-grammatical patterns

As reported in Section 5, the high number of errors among nouns in the pre-test by both groups suggested that rule-based learning may not be adequate for improving language use in L2 writing. In this study, both groups had already acquired the basic meaning of each target noun, and were familiar with its grammatical rules; for instance, a noun can typically be modified by a determiner or an adjective, and followed by a preposition phrase as a complement. However, prior grammatical knowledge did not automatically lead to the successful use of the target words in their writing. This was partly due to the overgeneralization of the acquired rules. It was also likely that a lack of lexico-grammatical patterning was one of the possibilities that led to the occurrence of collocational and colligational errors. The improved use of the target nouns by the experimental group in the post-tests showed that paper-based DDL offered the experimental group practical guidance and helped them build up their knowledge of lexico-grammatical patterns.

Simplification of grammatical structures was another feature of the syntactic patterns of the nouns used by the control group. The students used a limited number of syntactic structures and failed to produce complex structures. When they attempted to use the target words, they tried to avoid employing unfamiliar syntactic patterns and preferred previously acquired structures. The structures there BE+N and theme+copular BE+N were frequently used, but few instances of the V+N structure were observed in the control group’s written texts. Inadequate knowledge of V+N patterns may have deterred the students from retrieving appropriate verbs to predicate the target nouns, which may have led to more lexical collocation errors and fewer instances of V+N patterns, particularly in passives. The qualitative comparison of the written texts in the immediate post-test revealed that after the treatment (observation of concordances), the experimental group was able to use a variety of lexical verbs to fill the V slot in the V+N pattern, such as trigger, provoke and stir up to collocate with controversy; face and reject with criticism; brought about with objection; worsen and exacerbate with situation. The acquisition of these lexical collocations, in return, assisted the students in generating the grammatical structure lexical verb+N, not only in the active voice but also in the passive.

The application of DDL activities encouraged learners to study the lexico-grammatical patterns by discovery learning. Through observing the KWIC concordances, they may become aware of the syntactic patterning and thus become “rule and instance learners” (Ellis, Reference Ellis1993: 91). KWIC concordances can increase learners’ sensitivity to collocation and improve language learning strategies (Pérez-Paredes, Reference Pérez-Paredes2010; Thurstun & Candlin, Reference Thurstun and Candlin1998).

The results of the survey revealed that most students had a positive response to corpus use on vocabulary learning in their writing. They rated the corpus favourably as a useful resource for learning grammatical patterns, which might suggest that observing a target word in concordances helps them to become aware of the importance of lexical patterning. However, it is also worth noting that cut-off sentences, based on the students’ reports on the problems of doing the concordance activity, may affect their writing content development. It might be advisable for learners to access to both types of corpus presentation, i.e. KWIC concordances and the full sentences of the word. In doing so, learners can switch, according to their own needs, between the KWIC presentation and the full context to better understand the contextual usages of the words.

Another challenge of DDL was the recognition of the boundary of chunks. Students might have difficulty in recognizing which word is the ‘real friend’ accompanying the observed word. It is possible that students may mistakenly identify word clusters by chunking the target word with its immediate neighbour either to the right or the left, when in fact these words are ‘chance neighbours’ belonging to other constituents of the sentence. Hence simply directing students to observe items occurring left and right of the target words might sometimes be misleading. This may be one of the reasons why a small number of students in the experimental group made no improvement in using a target word in their writing after doing the DDL activities. It would therefore be of help to provide appropriate guidance when students get confused in analyzing the concordances. Corpora can be used as learning resources for checking vocabulary use in the classroom, but teachers’ intervention is necessary in data-driven learning (Flowerdew, Reference Flowerdew2009).

7 Conclusion and suggestions for future research

The significant progress made by the experimental group in using the target words in their writing, along with their overall positive attitudes towards corpus use, show the feasibility and usefulness of DDL activities in L2 writing instruction. The merit of such activities is that they highlight both the lexical and the grammatical patterns of an individual word, which is not often achieved through conventional learning materials focusing on syntactic rules. This study adopted a paper-based design in promoting concordance learning activities, as it is crucial that the incorporation of corpora into language teaching be pedagogically mediated (Braun, Reference Braun2007; Pérez-Paredes, Reference Pérez-Paredes2010).

This controlled experiment investigated the short-term effects of DDL on the acquisition of lexico-grammatical patterns in L2 writing within a fixed period of time. The results were limited as they only indicated that the students were able to use the acquired patterns in their writing immediately after the treatment and two weeks later in the delayed post-test, yet this is not sufficient to detect the development of learners’ writing ability. It remains unknown whether learners would be able to use the newly acquired patterns in their writing after a longer time interval. Hence the need exists for longitudinal research to examine the long-term effects of DDL on improving the use of lexico-grammatical patterns in L2 writing.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to extend her thanks to the editors and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback and suggestions on this article.

Appendix 1: Paper-based DDL activities

Prewriting vocabulary study

Direction: Study the concordance, underline or highlight the word(s) that collocate(s) with the target noun, as has been done in the first example. Then answer the questions which follow. Do not worry that these are cut-off sentences – just familiarize yourself with the key words.

Study the concordance lines of objection and answer the following questions.

1. Which adjectives are used before objection(s)?

2. Which verbs or verb phrases are used with objection(s)?

3. Which preposition commonly follows objection(s)?

Objection

1. Lottery was eventually approved. Much of the objectionto the National Lottery came from church leaders.

2. profits to charity, but was rejected. My personal objectionto Camelot as the lottery organizer is that a large

3. most famous businesses and Families had a particular objectionto the start of the National Lottery.

4. All rely on participating viewers who have no great objectionto winning their moment of glory by doing their best

5. harmless fun which won’t break the bank. The main objectionto the lottery is based on the grounds that those who

6. than that, a tax on the poor. The main objectioncame from charities who predicted that charitable donate

7. like horse-racing and casinos. These objectionsbecame much greater with the introduction of scratch cards

8. are how bitterly unpopular taxation is; therefore, objectionsraised against the lottery concerned it being marketed

9. or saving for a holiday or a car. There were also objectionsraised to the amount of money the proposed jackpot was

10. and psychological drawbacks. There were two main objectionsagainst the introduction of the national lottery

11. would have been donated to charity. Another objectionraised was that the National Lottery would

12. The proposal of a lottery brought about many objectionsand complaints. There were, and still are, two

13. of conservative government! Despite the numerous objections, the introduction of the lottery has induced a ‘fever’

Study the concordance lines of controversy and answer the following questions.

1. Which preposition commonly follows controversy/controversies?

2. Which adjectives are often used before controversy/controversies?

3. Which verbs or verb phrases are used with controversy/controversies?

Controversy

1. most or all of this money would go to charity. There has also been some controversyover the allocation of money.

2. The statistics confirm a trend that will reignite the controversyover global warming, with the past 15 years

3. there should be a maximum jackpot of 20 million. The recent controversyabout the impartiality of the head of Office,

4. almost from her beginning, the yacht has provoked controversy. It was soon after Guthrie, who acquired her in the,

5. by the 90-strong Bar Council but it has stirred controversy within the Inns of Court and some traditional

6. to be a fresh avowal of rape. Since the entire controversywas triggered by those quotes, and since Depardieu

7. gained a level of legitimacy despite myriad controversies facing it. Online casinos are now competing for advertising

8. did not even exist. The numerous controversiessurrounding online gambling are tied to both legal and moral issue

Study the concordance lines of criticism and answer the following questions.

1. Which verbs or verb phrases are used with criticism(s)?

2. Which adjectives are often used before criticism(s)?

3. Which prepositions commonly follow criticism(s)?

Criticism

1. that would considerably change their life. Another criticism is of the size of the jackpots themselves. Many people

2. slogan of the lottery ‘it could be you’ came under intense criticism. However, recent studies have shown that the vast

3. the national lottery originally claimed. As far as the criticismdirected against the government is concerned, there was

4. say it hasn’t done enough. Egypt has already faced criticismfor conducting arbitrary arrests and indefinite

5. Societies are facing criticismover their fees, Caroline Merrell finds

6. It is difficult to argue against these criticisms. The amounts given to charity by individual donations

7. Burmese representative, Thein Tin, rejecting the criticisms, and defending his country’s human rights record,

8. I am not going to count any. The Minister rejected criticismsthat the Government is not doing enough to secure the

Study the concordance lines of situation and answer the following questions.

1. Which adjectives are used before situation(s)? Please write down the phrases. e.g. face such complicated situations

2. Which verbs or verb phrases are used with situation(s)?

3. Which prepositions are commonly used with situation(s)?

Situation

1. gambling problems often face such complicated situations in life. It then takes several years to pay back the debt.

2. It would increase gambling and exacerbate the situations of many whose financial situations would not

3. professional help should be hired if the situationgets out of hand. Gambling casinos have an environment

4. the previous debt. This will only worsen the situation further. Families should be very careful

5. Many Britons are in situationsof poverty where the lack of employment prospects

6. seen to fail the children involved by leaving them in situationsof risk. (Secretary of State for Social Services,

7. that may change their luck. People in desperate situations often tend to turn to the gambling table where they test.

8. importance, for without it a car is unusable in many situations. Overall dimensions are another subject which is

9. have annoying traits which we demonstrate in certain situations and which we counterbalance with our personality

10. and tacit, intuitive, commonsense knowledge. In some situations, these different sources of knowledge were in

11. ability to make people laugh, even in the most serious situations. And many times he has shown his readiness to take

Study the concordance lines of effect and answer the following questions.

1. Which adjectives are used before effect(s)?

2. Which verbs or verb phrases are used with effect(s)?

3. Which prepositions are used with effect(s)?

Effect

1. a profit on it. Many have also speculated as to the effectsof being a jackpot winner. Sudden riches overnight see

2. term implications on gambling habits plus the positive effects will have to be considered before a decision on its

3. in the family needs to be educated on the harmful effectsof gambling too much. Put security locks on the gamble

4. a print before exposing it to get even more noticeable effects, but there’s no solution other than to reprint the

5. the Georgian capital, Tbilisi. He compares the terrible effectsof multiple abortions in Georgia to the problem of

6. Thus, previewing served here to predict the potential effectsof Deirdre’s illness and of her personality traits on

7. The oil spill didn’t seem to have any detrimental effectson the salmon run, so we didn’t observe any

8. because it has had a significant effecton the economy. As well as causing a fall in charity

9. church have expressed great concern at the effecton low income families who spend more than they can

10. ‘flutter’ on the National lottery each week has no effecton their financial position. This kind of people can a

Appendix 2: Survey on the DDL activities

Had you heard about concordances before you took this class? (Circle one)

Yes No

Answer the following questions by using the scale below to circle the response that most closely resembles your perspectives.

1: strongly disagree; 2: disagree; 3: Somewhat disagree;

4: somewhat agree; 5: agree; 6: strongly agree; N: no opinion