Introduction

Insomnia is a distressing and chronic condition affecting 30–60% of all cancer survivors (Mao et al., Reference Mao, Armstrong and Bowman2007; Savard et al., Reference Savard, Ivers and Villa2011; Irwin, Reference Irwin2013; Davis and Goforth, Reference Davis and Goforth2014). It is characterized by difficulty falling asleep, maintaining sleep, or waking up too early that causes significant distress or impairment in daytime functioning (American Psychiatric Association, 2014). Among cancer survivors, insomnia has been associated with decreased quality of life as well as increased pain, fatigue, anxiety, and depression (Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, Gillespie and Espie2010; Nishiura et al., Reference Nishiura, Tamura and Nagai2015). Sleep problems also frequently affect how survivors feel physically and hinder their ability to concentrate, cope with stress, and carry out daily activities (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, MacLean and Brundage2002).

Treatment of cancer-related insomnia has proved difficult due to the limitations of conventional therapy. Pharmacologic treatment often includes medications that have been associated with bothersome side effects (e.g. daytime sedation and cognitive and psychomotor impairments) (Pagel and Parnes, Reference Pagel and Parnes2001; Savard and Morin, Reference Savard and Morin2001; Kvale and Shuster, Reference Kvale and Shuster2006; Induru and Walsh, Reference Induru and Walsh2014). Furthermore, given the polypharmacy of cancer treatment, concerns exist regarding tolerance, dependency, and drug-to-drug interactions (Savard and Morin, Reference Savard and Morin2001; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Fullington and Alvarez2018). Among non-pharmacologic treatments, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) has demonstrated the efficacy in improving sleep (Morgenthaler et al., Reference Morgenthaler, Kramer and Alessi2006; Trauer et al., Reference Trauer, Qian and Doyle2015; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Rash and Campbell2016; Qaseem et al., Reference Qaseem, Kansagara and Forciea2016). However, access to CBT-I is not widely available due to the limited availability of CBT-I clinicians at medical centers as well as a lack of physician referrals for CBT-I treatment (National Institutes of Health, 2005; Pigeon et al., Reference Pigeon, Crabtree and Scherer2007; Conroy and Ebben, Reference Conroy and Ebben2015).

Among complementary and integrative medicine modalities, acupuncture is widely used by cancer survivors at a higher rate than the general population (Mao et al., Reference Mao, Palmer and Healy2011) and is considered safe with few side effects (e.g. needling pain and bruising) (White, Reference White2004). Of the 45 NCI-designated cancer centers, 89% currently endorse the use of acupuncture for symptom management (Yun et al., Reference Yun, Sun and Mao2017). Acupuncture has shown promise in the treatment of cancer-related insomnia and may be superior to conventional drug therapy, yet the methodology of acupuncture administration has varied greatly in these trials (Bokmand and Flyger, Reference Bokmand and Flyger2013; Haddad and Palesh, Reference Haddad and Palesh2014; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Kim and Lim2017). In our recently completed randomized clinical trial of acupuncture vs. CBT-I for insomnia, we found that both acupuncture and CBT-I produced a clinically meaningful reduction in insomnia, and the therapeutic effects persisted 3 months after the end of intervention; however, CBT-I was more effective overall (Garland et al., Reference Garland, Xie and DuHamel2019).

Clearly, there is a room for continued acupuncture refinement to improve overall effectiveness. The primary objective of this qualitative study was to identify the factors that influence the perception of acupuncture's therapeutic effect among cancer survivors with insomnia who participated in our clinical trial. A better understanding of patients' perspectives regarding acupuncture response may contribute to design more effective treatment protocols or help to identify patients who are more likely to respond to the treatment.

Methods

Participants

One hundred and sixty patients were enrolled in our randomized clinical trial for comparing the effectiveness of CBT-I and acupuncture for the treatment of insomnia in cancer survivors [Clinical trial registration: NCT02356575] (Garland et al., Reference Garland, Gehrman and Barg2016; Garland et al., Reference Garland, Xie and DuHamel2019). From these 160 participants, we recruited a subset (N = 63) to participate in semi-structured interviews prior to randomization. Of these, 31 were randomized to the acupuncture group, and 28 participated in interviews following the completion of treatment. All participants were English speaking, age 18 or older, had a cancer diagnosis, and had completed active treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy) at least 1 month prior to enrollment. Additionally, all participants underwent a clinical eligibility visit to confirm that they reported a score of greater than seven on the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (Savard et al., Reference Savard, Savard and Simard2005) and met the criteria for insomnia disorder as defined by the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2014). All participants signed a written informed consent prior to study activities. All study activities were reviewed and approved by the University of Pennsylvania's Institutional Review Board.

Acupuncture intervention

The acupuncture treatment protocol has been previously described (Garland et al., Reference Garland, Gehrman and Barg2016, Reference Garland, Xie and DuHamel2019). To briefly summarize, patients in the acupuncture group received two treatments per week in the first two weeks and one treatment during each subsequent week for a total of 10 treatments of acupuncture over eight weeks. Licensed acupuncturists followed the acupuncture treatment protocol and chose needling points based on the standardized points for insomnia symptoms and the customized points for individual patient-reported symptoms. Needles were manipulated to achieve the “De Qi” sensation and were retained for 30 min with brief manipulation at the beginning and at the end of the treatment. Patients were also given an information handout with tips for improving sleep hygiene, but no counseling regarding sleep behaviors was provided.

Questionnaire

Patients completed a study questionnaire at baseline that included demographic, cancer, and treatment characteristics. Additionally, patients completed the ISI at baseline and week 8 (post-treatment) to assess changes in insomnia symptoms. The ISI is a well-validated, self-report measure consisting of seven items in which subjects rate the intensity of their insomnia symptoms on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4 with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms (Savard et al., Reference Savard, Savard and Simard2005). Patients also completed the Consensus Sleep Diary to capture patient report of nightly insomnia symptoms throughout the eight-week treatment period (Carney et al., Reference Carney, Buysse and Ancoli-Israel2012).

Qualitative interview and analysis

The interview guide and procedures for conducting, coding, and analyzing the interviews have been published previously (Garland et al., Reference Garland, Eriksen and Song2018). Open-ended, semi-structured interviews were conducted to elicit expected and unexpected benefits and side effects of acupuncture treatment. A trained research assistant conducted the interviews after the completion of the intervention, with support from personnel at the Mixed Methods Research Lab at the University of Pennsylvania. We used an integrated approach for data analysis (Curry et al., Reference Curry, Nembhard and Bradley2009), by merging an a priori set of codes derived from the key ideas we sought to understand and a set of codes that emerged from the data through a grounded theory approach (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Hadfield and Chapman2015). For the current analysis, we categorized interview transcripts into Responders and Non-Responders based on the change in the ISI with a reduction of eight points or greater as the cut-off for a marked clinical response (Morin et al., Reference Morin, Belleville and Belanger2011). We examined coded transcripts for themes and patterns contributing to response or non-response to acupuncture.

Results

As shown in Table 1, the mean age was 60.1 years (range: 27.5–83.6 years). Study participants were evenly divided between men and women. Twenty-two participants identified as White, five as Black, and one as Asian. The most common cancer types represented were breast (29%), prostate (21%), and hematological (11%) cancer; three participants reported having been diagnosed with more than one cancer. Based on a greater than or equal to an eight-point reduction in the ISI score, 18 (64%) participants had a significant response to acupuncture treatment, while 10 (36%) participants did not.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics (N = 28)

a Other cancer includes skin, lung, other gastrointestinal, other genitourinary, etc.

We identified three themes that impacted participants' perception of response to acupuncture treatment: (1) alleviation of co-morbidities contributing to insomnia, (2) support of sleep hygiene practices, and (3) durability of therapeutic effect. Quotations from participants to support these themes are included in Tables 2–4.

Alleviation of co-morbidities contributing to insomnia

Among all participants, sleep was often impacted by co-morbid conditions, including anxiety, pain, and hot flashes (see Table 2). Many Responders reported improvements in their insomnia when these co-morbidities were alleviated by acupuncture treatment. Some Responders reflected that acupuncture promoted a state of relaxation that helped them to manage tension or cope with anxious thoughts that made falling asleep difficult. Other Responders noted that acupuncture relieved pain that contributed to sleep disruptions. In contrast, hot flashes or pain not addressed by treatment made it difficult for a few Non-Responders to distinguish improvements in their sleep. While some symptoms did not respond to treatment, uncertainty about what symptoms could be addressed within the treatment protocol presented an additional barrier for at least one Non-Responder who felt that the acupuncture did not address the pain that contributed to her insomnia.

Table 2. Quotes from participants regarding alleviation of co-morbidities contributing to insomnia

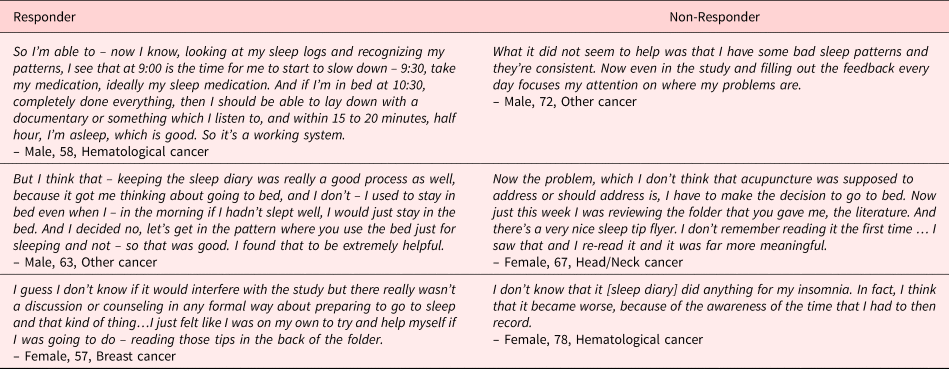

Supporting sleep hygiene practices

Many participants believed that sleep behavior contributed to poor sleep and were interested in the potential benefit of incorporating sleep hygiene practices into their insomnia treatment (see Table 3). Responders found aspects of the trial that increased awareness of maladaptive sleep practices, such as the sleep diary and sleep hygiene handout, to be helpful. Additionally, Responders felt empowered to change the aspects of their daily routine toward promoting better sleep.

Table 3. Quotes from participants related to supporting sleep hygiene practices

While several Non-Responders also noted greater awareness of maladaptive sleep behavior, they were generally less proactive in improving sleep hygiene practices. These participants did not expect acupuncture to directly affect sleep behaviors but still believed that these issues needed to be addressed in treating the underlying causes of their insomnia. A few participants noted that treatment could benefit from greater emphasis on the sleep hygiene handout with a Non-Responder not discovering this handout until the end of treatment and a Responder desiring additional support through counseling or discussion of the sleep hygiene information.

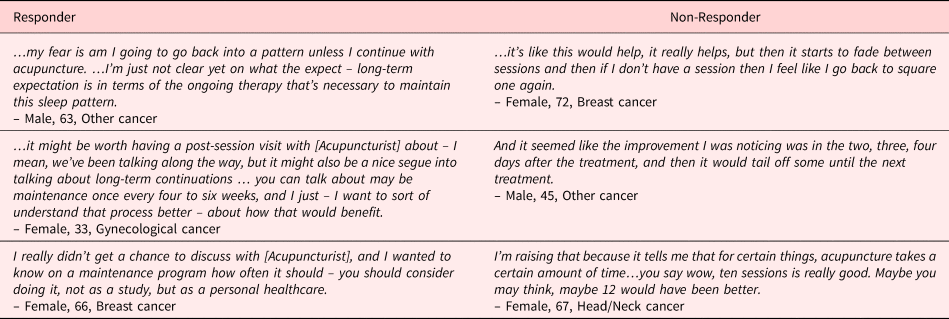

Durability of therapeutic effect

The durability of acupuncture's therapeutic effect was a major concern for both Responders and Non-Responders (see Table 4). Responders generally experienced durable therapeutic effects during treatment and, as a result, tended to be more concerned with the sustainability of insomnia relief after the completion of acupuncture. Several participants desired additional education on an appropriate regimen of acupuncture treatments after the study to maintain the benefits they experienced. One Responder commented on experiencing greater symptom relief during weeks with two treatment sessions and wondered if treatment frequency influenced acupuncture's efficacy.

Table 4. Quotes from participants on durability of therapeutic effect

Some Non-Responders observed promising sleep improvements in the period immediately after needling but felt disappointed when the effects would fade between treatment sessions. All participants who experienced only a temporary relief of their insomnia stated that they did not derive an overall benefit from acupuncture. However, a few of these Non-Responders expressed a belief that acupuncture might have been more helpful if more treatment sessions had been received.

Discussion

Insomnia is a debilitating condition experienced by up to 60% of cancer survivors (Irwin, Reference Irwin2013). In this qualitative study, three themes were identified as influencing patients' perception of their ability to respond to acupuncture: (1) alleviation of co-morbid conditions contributing to insomnia, (2) support of sleep hygiene practices, and (3) durability of therapeutic effect. Acupuncture treatment that was perceived by patients do not address one of these three factors often detracted from perceived positive outcomes and diminished perceived benefit from the treatment. Our study contributes to a limited body of research and, to our knowledge, is the first qualitative investigation that focuses specifically on examining patient-perceived factors that contribute to response to acupuncture treatment for insomnia.

We found that persistent co-morbid conditions, such as pain and hot flashes, often detracted from acupuncture treatment and made it difficult for Non-Responders to discern improvements in sleep. Similarly, Witt et al. (Reference Witt, Schutzler and Ludtke2011) found that among patients with chronic pain, baseline pain and co-morbid medical conditions predicted treatment outcomes to patients randomized to either acupuncture or usual care. In Traditional Chinese Medicine, acupuncture is usually adapted to each patient's unique symptoms, and previous research has shown that patients value this type of individualized care (MacPherson et al., Reference MacPherson, Thorpe and Thomas2006; Haddad and Palesh, Reference Haddad and Palesh2014). However, this aspect of acupuncture is often excluded from clinical trials, which focus on treating illnesses/symptoms in isolation. While the main trial's acupuncture protocol allowed some flexibility in needling to accommodate patient's co-morbid complaints such as pain and anxiety, the protocol primarily focused on treating insomnia (Garland et al., Reference Garland, Gehrman and Barg2016; Garland et al., Reference Garland, Xie and DuHamel2019). Our findings suggest that future insomnia acupuncture treatment protocols will need to incorporate a structured approach to allow adequate treatment of co-morbid symptoms such as hot flashes and pain contributing to insomnia.

Participants also perceived poor sleep hygiene practices to influence their response to acupuncture. Cancer treatment can disrupt daily routines and lead to the development of behavioral patterns that perpetuate poor sleep (Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, Gillespie and Espie2010). While there is compelling evidence for behavioral therapy that targets these causes of insomnia (Morgenthaler et al., Reference Morgenthaler, Kramer and Alessi2006; Trauer et al., Reference Trauer, Qian and Doyle2015), behavioral therapy was limited in the main trial to provide a better comparison between acupuncture and CBT-I (Garland et al., Reference Garland, Gehrman and Barg2016; Garland et al., Reference Garland, Xie and DuHamel2019). Although all participants in the acupuncture group were given a handout with sleep hygiene tips, this resource was insufficient to effectively change the sleep behaviors due to the individualized nature of people. Some participants were more likely to take initiative in altering their sleep behaviors and found that these changes contributed to treatment response.

In contrast, a few participants expressed a desire for additional support and guidance from the acupuncturist regarding their sleep hygiene practices. In clinical practice, acupuncture practitioners often interweave conversations about self-care into successive treatment sessions to facilitate the active engagement of patients in their own recovery. Previous qualitative research suggests that practitioners and patients both believe these self-care discussions are beneficial for treatment response (MacPherson et al., Reference MacPherson, Thorpe and Thomas2006; Paterson, Reference Paterson2007; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Paterson and Wye2011; Price et al., Reference Price, Long and Godfrey2014). Future hybrid interventions, which incorporate both counseling on sleep hygiene practices during self-care discussions and acupuncture treatment, should be developed and tested for the treatment of insomnia in cancer populations.

Regardless of response to the treatment, Responders and Non-Responders were concerned about the durability of therapeutic outcome. Insomnia relief that faded between treatment sessions detracted from treatment benefit and contributed to non-response for several individuals. Some Non-Responders, who observed greater symptom relief following the weeks with two acupuncture sessions, felt that acupuncture's efficacy would have been improved with more acupuncture sessions per week. This aligns with another qualitative acupuncture study where patients were also dissatisfied with temporary symptom relief and concerned about receiving appropriate treatment dosage (Paterson, Reference Paterson2007). Further, previous research supports a possible association between acupuncture efficacy and treatment frequency (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Xue and Dong2013; MacPherson et al., Reference MacPherson, Maschino and Lewith2013).

While Non-Responders were concerned with outcome durability between treatment sessions, Responders were more focused on the durability of symptom relief after the completion of acupuncture treatment. For the main trial, we found that the therapeutic effect of acupuncture for insomnia was durable up to 3 months after treatment ended (Garland et al., Reference Garland, Xie and DuHamel2019). Additionally, in trials of acupuncture for chronic pain and hot flashes, therapeutic effects were found to be durable up to 6 months after the completion of treatment (Mao et al., Reference Mao, Bowman and Xie2015; Lesi et al., Reference Lesi, Razzini and Musti2016; MacPherson et al., Reference MacPherson, Vertosick and Foster2017). Future research should focus on examining the short- and long-term efficacy of acupuncture treatment for insomnia as well as incorporating booster acupuncture sessions to treatment protocols.

Some limitations to the study should be acknowledged. First, our study sample volunteered to participate in a clinical trial of acupuncture for the treatment of insomnia. Thus, the patients' perspectives reported in this paper are captured from a clinical trial experience vs. from a real-world acupuncture experience. Hence, the interpretation of the findings is limited to clinical trial settings. Second, our sample consisted of patients with cancer who were primarily college-educated, English speaking, and expressed an interest in acupuncture; therefore, the results may not be generalizable to the larger cancer population. Despite these limitations, our study included an equal sample of males and females and a diverse group of patients in terms of cancer type.

Conclusions

In our study, we identified patient-perceived contributors to response to acupuncture, such as co-morbid medical conditions, adequate support for sleep hygiene practices, and temporary therapeutic relief. Future acupuncture interventions for insomnia should address these factors in order to improve the overall effectiveness of acupuncture among individuals with cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients, oncologists, nurses, clinical and research staff, and the CHOICE Study Patient Advisory Board members (Winifred Chain, Linda Geiger, Donna-Lee Lista, Jodi MacLeod, Alice McAllister, Hilma Maitland, Edward Wolff, and Bill Barbour) for their support of this study. Research related to the development of this paper was supported in part by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) award (CER-1403-14292) and by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health grants to the University of Pennsylvania Abramson Cancer Center (2P30CA016520-40) and the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (3P30CA008748-50; R25CA020449). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent official views of PCORI, its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee, or the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. No competing financial interests exist.