INTRODUCTION

This article addresses the question of how language ecology shapes the bilingual speech observed in multilingual settings.Footnote 1 It is based on present-day, first-hand data from two previously undocumented varieties of Romani and Pomak in contact with Turkish in Greek Thrace. In order to isolate the relevant parameters, I chose to compare these two communities within the Muslim minority of Thrace, which are very different in terms of their socio-professional and cultural profiles but live in roughly the same area and share long-term contact with Turkish. This contact began in Ottoman times and continued in both communities throughout the 20th century. From the perspective of language contact outcomes, despite some similarities in borrowings, close study reveals that Turkish has a radically different status in these two language communities: Komotini Romani is an example of what Auer Reference Auer1998 terms a “fused lect,” a form of stabilized codeswitching with a high number of borrowings (verbs, nouns, adverbs, conjunctions) and a variety of borrowing strategies (such as complete verb paradigm transfer and borrowed inflexion for masculine nouns). Pomak, in contrast, shows fewer borrowings, including only a few verbs, and more habitual discourse- and participant-related codeswitching. As I argue here, these differences are related to the patterns of language contact in these societies, which in turn are related to the speech community's ecology.

REVIEW OF LITERATURE ON LANGUAGE CONTACT AND SOCIAL FACTORS

The term “ecology of language,” as applied to linguistics by Mufwene Reference Mufwene2001 (following Voegelin, Voegelin & Schultz Reference Voegelin, Voegelin, Schultz, Hymes and Bittle1967 and Haugen Reference Haugen1972), refers to the analysis of language as a complex system of adaptation to the external, social environment and to internal language variation. Studying the ecology of a language implies taking a close look at the social, ethnographic, cultural, and economic environment in which the language is spoken, including a wide range of factors such as population size and changes in living conditions. Moreover, from a macroecological perspective, Mufwene suggests that the study of language ecology should also include system-internal linguistic factors such as language contact, cross-dialectal and inter-idiolectal variation, and structural linguistic features (Mufwene Reference Mufwene2001:22). Thus the term “language ecology” has come to cover all the parameters, external and internal, necessary for understanding language contact.

In the tradition of Weinreich Reference Weinreich1953, relations between language contact outcomes and the types of society they are produced in have frequently been the center of attention. An attempt to correlate the intensity of contact with language contact outcomes led to the proposal of a borrowing scale (Thomason & Kaufman Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988:74–75) ranging from “casual contact” and lexical borrowing to “very strong cultural pressure” and heavy structural borrowing. Winford Reference Winford2003, following Loveday Reference Loveday1996, also correlates the degree of bilingualism and contact phenomena through a continuum that starts with “distant” contact and lexical borrowing and ends with high multilingualism in heterogeneous communities. TrudgillReference Trudgill, Bervik and Jahr1989 (more recently, cf. Trudgill Reference Trudgill2008 vs. Mufwene Reference Mufwene2008) has also convincingly shown how social and sociolinguistic parameters shape contact-induced change. More specifically, he has studied community size (large vs. small), social network structures (tight vs. loose), and types of contact (low vs. high, long-term contact with child bilingualism vs. short-term contact with adult bilingualism). Recent studies in contact linguistics pursue this approach, taking into consideration the external factors that facilitate the diffusion of linguistic features (Aikhenvald & Dixon Reference Aikhenvald and Dixon2007). From a synchronic viewpoint, the study of codeswitching phenomena has contributed to a better understanding of language contact mechanisms. The constraints and social significance of bilingual speech are analyzed in a more advantageous manner, and it is possible to combine macro- and micro-level analyses (see, among others, Poplack Reference Poplack1980; Gumperz Reference Gumperz1982; Myers-Scotton Reference Myers-Scotton1993a, Reference Myers-Scotton1993b; Silva-Corvalàn Reference Silva-Corvalàn1994).

However, Matras Reference Matras, Matras and Sakel2007 challenges the importance traditionally assigned to social parameters by claiming that the sources of borrowing are to be found in “the need to reduce the cognitive load” (Matras Reference Matras, Matras and Sakel2007:67, following Matras Reference Matras1998). Contrary to Thomason & Kaufman (Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988:35), who claim that “it is the sociolinguistic history of the speakers … that is the primary determinant of the linguistic outcome of language contact. Purely linguistic considerations are relevant but strictly secondary overall,” for Matras sociolinguistic factors are relevant, yet secondary: They do not trigger but rather “license” the speakers to “dismantle the mental demarcation boundaries that separate their individual languages” (Matras Reference Matras, Matras and Sakel2007:68).

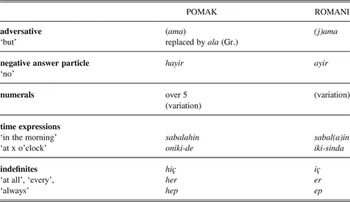

The present case study brings some new insight to this debate. On the one hand, Pomak and Romani share some borrowings from Turkish that agree with the universal borrowability hierarchy proposed by Matras Reference Matras, Matras and Sakel2007. For example, both have borrowed the adversative marker, numerals, and the same time expressions and indefinite nouns. On the other hand, the degree and type of contact, factors directly dependent on the social environment, explain to a great extent the differences observed in the results of language contact in the two cases.

AN INTRODUCTION TO POMAK AND ROMANI

Both Balkan and Romani studies have long been at the heart of contact linguistics. The Balkan Sprachbund was proposed by Troubetzkoy in Reference Troubetzkoy1928, based on earlier works by Kopitar Reference Kopitar1829, Miklosič Reference Miklosič1861 and Sandfeld Reference Sandfeld1926. In modern studies, it accounts for the fact that many distantly related Balkan languages have “converged,” meaning that they have developed parallel syntactic structures that do not occur in the genetically related languages found outside the Sprachbund. The Balkan Sprachbund includes the South Slavic languages – Macedonian, Bulgarian and Serbian – as well as Balkan Romance, Albanian, and to some extent Greek, Balkan Turkish and Judezmo. Although Romani has also participated in the areal convergence phenomena and is considered a “balkanized” Indo-Aryan language, Romani dialects are best known for their “language mixing.”

Pomak

Pomatsko ‘Pomak’ is the name used for the South Slavic variety spoken by Muslim inhabitants of the Rhodope Mountains in Greece1, who often migrated to other cities or countries during the second half of the 20th century (see Figure 1). The origin of the Pomaks is very controversial and heavily influenced by state ideologies; Turkish researchers claim that Pomaks are of Turkic origin and shifted to Slavic, Bulgarian researchers that Pomaks are Slavs who were converted to Islam, and some Greek researchers relate them to pre-Slavic and pre-Turkic local populations. This study focuses on a Pomak variety spoken in a village of the Xanthi area, which I will refer to as Pomak1.Footnote 2 I carried out fieldwork in this village on four occasions between 2005 and 2009, combining questionnaires with, more significantly, observation of speech production in natural contexts.

Figure 1: The Pomak (1) and Komotini Romani (2) vernaculars in Greek Thrace.

The Pomaks living in Thrace, together with the Turks and Muslim Roma, were exempted from the obligatory exchange of populations that took place in the 1920s when Ottoman rule collapsed. They were guaranteed the right to bilingual education in Greek (the state language) and Turkish (the Muslim minority language) (1923, under the Lausanne Treaty). In this context, a shift to Turkish became generalized in the second half of the 20th century,Footnote 3 as it was considered by the communities to be a more useful language for social advancement; the shift was also motivated by the community's strong religious identity (Greek is the emblematic language to which the Christian populations in modern Greece shifted).

Contrary to the general tendency to shift to Turkish, in the village under study (and more broadly in the general area) Pomak is still transmitted to children and is used in everyday communication. The majority of the speakers in this village are trilingual. The younger generation, both men and women, have learned Greek and Turkish at school, within the “Minoritariste” primary school educational system. However, monolingual Pomak speakers are still to be found among the oldest women. Most frequently, women over 50 years of age have basic communication skills in Greek and Turkish, limited to greetings and short conversation (Adamou & Drettas Reference Adamou, Drettas and Adamou2008).

Pomak1 shares some common Balkan Sprachbund properties, such as a ‘will’ future, a subjunctive, the dative/genitive merger, and postposed articles. Compared to the most closely related South Slavic languages, Pomak1 shows some interesting features. For example, similarly to other peripheral Balkan Slavic dialects, it has preserved, to a certain extent, its case system – distinguishing between the nominative, the dative-genitive, and the accusative, the latter being subject to differential marking related to humanness (see Adamou Reference Adamou2010). Note that loss of the case system is one of the main features that distinguish Bulgarian and Macedonian from Serbian; Bulgarian and Macedonian have developed an analytical system based on prepositions for the same functions.

Moreover, Pomak1 shows some features that are exceptional for Slavic languages in general, such as the overt expression of deixis in the formation of temporal conjunctions, indicating the anchoring of the event in the speech time situation (see Adamou in press). The deictic suffixes also constitute the definite articles and the demonstratives: For “here and now” situations, the entities considered as being part of the speaker's sphere receive the -s- suffix, while the -t- suffix is reserved for the addressee's sphere and the -n- suffix for distal entities. But when the entities are situated in a different space and time sphere while retaining relevance for the discourse situation, the -t- suffix is used for the past, while the -n- suffix is used for entities in all non-past situations.

Romani

Romani is an Indo-Aryan language spoken throughout Europe, in the Americas, and in Australia. The migrants, who probably belonged to service-providing castes (Matras Reference Matras2002), arrived from India during the period of the Byzantine Empire, around the 10th century. Romani was considerably influenced by Greek during this period. At the end of the Byzantine era, some groups migrated toward western and northern Europe and new contact languages were added.

The first dialectological classifications were carried out by Miklosič Reference Miklosič1872–1880, reconstructing migration routes through the analysis of loanwords. The Balkans Roma were divided into two major groups on the grounds of religion and mobility (see Paspati Reference Paspati1870). On this basis, Gilliat-Smith Reference Gilliat-Smith1915 distinguished in Bulgaria between the nomadic Christian populations originating from Wallachia, termed the Vlax, and the Muslim, settled groups, termed non-Vlax. This had considerable impact on Romani studies, but more recently a dialectal categorization based on linguistic features has become dominant, distinguishing for the Balkan area a Balkan Romani branch and a Vlax Romani branch, with the latter being geographically centered in today's Romania and including the migrants in various Europeans countries (Bakker & Matras Reference Bakker, Matras, Matras, Bakker and Kyuchukov1997, Elšík Reference Elšík, Elšík and Matras2000, Boretzky & Igla Reference Boretzky and Igla2004).

The dialects currently spoken in Greece belong to the Balkan and Vlax Romani branches. The presence of Balkan Romani speakers is documented as early as the 11th century and has been continuous since then. Vlax groups arrived more recently, usually in the 1920s following the Lausanne Treaty. The data presented in this paper were collected during three fieldwork visits carried out between 2005 and 2007 in a small Muslim community of approximately 300 people, settled in the suburbs of the city of Komotini. Komotini, or Gümülcine in Turkish, is particularly well known in Romani studies because the earliest Romani text from the Balkans was written down there, in 1668 by Evliya Çelebi, and published in the Seyahat name ‘Book of travels’ (see Friedman & Dankoff Reference Friedman and Dankoff1991 for an analysis of the text).

Present-day Komotini Romani (KR) is clearly a Vlax variety that cannot be considered a direct descendant of the 17th-century Gümülcine Roma. As is often the case for the Roma communities, Komotini Roma have mixed origins; the older ones seem to be related to various places in present-day Greece and Bulgaria. At present, the group is closely connected to and intermarries with other Roma groups living in various urban neighborhoods of the city or in the nearby city of Xanthi. The most common language name is romani (adj.), romane (adv.), characterized by the loss of the final -s. Men, women, and children are trilingual in Romani, Turkish, and Greek. Speakers distinguish between “pure Romani” as opposed to their own xoraxane romane, or Turkish-Romani dialect. In this neighborhood Romani is still transmitted to children, but a shift to Turkish is reported to be taking place in other, wealthier Muslim communities.

LANGUAGE CONTACT OUTCOMES

Through analysis of the contact mechanisms and processes, I now show how the results of contact with Turkish differ between Pomak1 and Komotini Romani (KR).

Codeswitching and fused lects

Pomak1 and Komotini Romani are significantly different at the level of bilingual speech. Pomak1 shows classic participant-related codeswitching with Turkish and, more importantly, with Greek. As Auer describes it,

In CS (code-switching), the contrast between one code and the other (for instance, one language and another) is meaningful, and can be interpreted by participants, as indexing (contextualizing) either some aspects of the situation (discourse-related switching), or some feature of the code-switching speaker (participant-related switching). (Auer Reference Auer1998:2).

In contrast, Komotini Romani is better understood in terms of a fused lect, a category proposed by Auer (Reference Auer1998:1) to describe “stabilized mixed varieties”:3

While LM (Language Mixing) by definition allows variation (languages may be juxtaposed, but they need not be), the use of one ‘language’ or the other for certain constituents is obligatory in FLs; it is part of their grammar, and speakers have no choice. (Auer Reference Auer1998: 15).

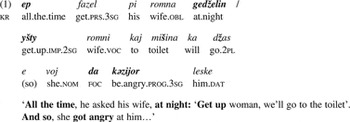

Consider the following example from KR (Turkish in bold):

(1) Excerpt from the tale “The Coward and the Giants” (sentences 4, 5). Sound, annotation and translation of the complete texts are available online: http://lacito.vjf.cnrs.fr/archivage/languages/Romani_fr.htm

Since the KR speakers are trilingual, Greek insertions are also frequent (Greek underlined, Turkish in bold, Romanian in bold and underlined):

(2)

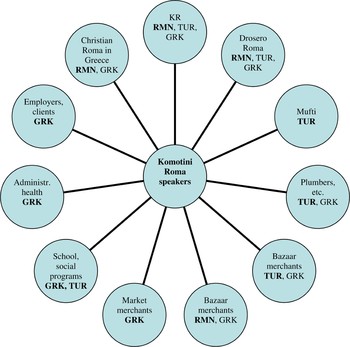

Despite their superficial similarity, Greek and Turkish insertions have a very different status in KR. The Greek insertions are an aspect of discourse-related codeswitching that is not obligatory and that results from relatively recent bilingualism (three to four generations). In this example, ute ‘nor’ is linked to eksetasis ‘exams’, which like ‘psychologist’ is related to Greek institutional realities. In other moments in discourse the same speaker, instead of using ute ‘nor’, will use the Indic equivalent, in. Turkish items, on the contrary, are obligatory in the Komotini Romani dialect. Nevertheless, owing to their complex networks (see Figure 2) and mobility (it is common to spend years in other Greek cities), the Komotini Roma can communicate in other Romani dialects presenting a minimum of Turkish borrowings, as is the case of Christian Roma. A clear, conscious distinction is made between their own Turkish-Romani dialect and the other Romani dialects they master. This competence most likely explains some cases of variation between a Turkish loan verb and an Indic verb, as can be observed in the narration of a tale by the same speaker:

(3) Excerpt from the tale “The Man-snake”; http://lacito.vjf.cnrs.fr/archivage/languages/Romani_fr.htm

Figure 2: The Komotini Roma social network (interaction language in bold type).

The Turkish items found in KR are not due to the current contact situation but result from the generalized bilingualism current during the Ottoman Empire. This is better understood when we look at the larger picture in the Balkans, where similar Turkish-Romani dialects are to be found in many Balkan countries with more or less intense contemporary contact with Turkish (e.g. Bulgaria, Former Yugoslavic Republic of Macedonia, and Kosovo). Interestingly, comparison with the Romani dialect spoken by Christian Roma settled in the Ajia Varvara neighborhood in Athens shows that the Turkish loan verbs are used with Turkish verb morphology even though the speakers stopped being proficient in Turkish at least three or four generations ago, as seen in Table 1 (from Igla Reference Igla1996).

Table 1. Ajia Varvara Romani (Igla Reference Igla1996: 61).

As Auer notes, contrary to code-mixing, which requires competent bilingual speakers, “speakers of a fused lect AB may but need not be proficient speakers of A and/or B” (Auer Reference Auer1998:13). Although there is no doubt that current bilingualism helps maintain and develop this strategy in Komotini Romani, it is more than likely that grammaticalization of the Turkish insertions was completed at an earlier stage. Therefore, we need to consider the contact ecology at the moment when this language mixing emerged and observe the contemporary contact ecology favoring its use and development.

Borrowings and borrowing integration strategies

Both Pomak1 and Komotini Romani show borrowing as the main process induced by contact with Turkish. We retain the term “borrowing” here to describe cases of transfer of forms or forms and meanings in the recipient language (Heine & Kuteva Reference Heine and Kuteva2005). Borrowings, unlike codeswitching insertions, are those items that can be found in monolingual contexts or, when applicable, can be used by monolingual speakers (Matras Reference Matras2009). They have their origins in the speech of bilinguals, and unlike codeswitching, they require a long-term or permanent license to lift selection constraints on the use of a word-form or structure (see the continuum codeswitching–borrowing in Matras Reference Matras2009: 111).

Some of the borrowings from Turkish – many of which are of Persian origin – are common in both Pomak and Romani (despite different phonetic articulations); see Table 2. From a typological perspective, they also join borrowings commonly found cross-linguistically and presented in the borrowability hierarchy, a hierarchy based on “the likelihood of a category to be affected by contact-induced change” (Matras Reference Matras, Matras and Sakel2007:31).

Table 2. Shared Pomak1 and Komotini Romani borrowings from Turkish.

Matras Reference Matras1998 has pointed out the high borrowability of the connectors and suggested that the adversative was the most frequently borrowed (followed by ‘or’ > ‘and’). It is interesting to note that the Greek adversative ala is slowly replacing the Turkish adversative ama in Romani and has already replaced it in Pomak1. Contrary to the cross-linguistic tendency to borrow the positive answer particle (Matras Reference Matras, Matras and Sakel2007), in this case both languages have borrowed the negative answer particle. Numerals are generally borrowed from the dominant language, in this case from the local trade language of the traditional “bazaar” market. In Romani, Turkish numerals are used for counting money while Romani lower numerals are used for entities such as days and months (note that some Romani numerals are old borrowings from Greek). In Pomak, Turkish numbers are used over 5, and under 5 for specific cases such as telephone numbers.

Despite these shared borrowings, Pomak has fewer borrowings than Romani, but most importantly, contrary to Romani, loan verbs are very rare in Pomak. Pomak borrowings are mainly lexical, some of them being cultural borrowings (greetings and expressing thanks), emblematic of Turkish-Muslim identity together with Turkish first and last names. Romani, on the other hand, has borrowed Turkish da, very frequently used as a focus and topic marker postposed to a noun as well as a coordinator, the plural suffix for the personal pronoun onnar, from Romani on and Turkish on-lar, and the obligation marker lazım.

Still, the most significant difference between KR and Pomak1 concerns the strategies used for the integration of the borrowings in the two languages.

Lexical integration

In Pomak all lexical borrowings bear Slavic inflexions (for the three definites, case, and number):

(4)

In KR, Turkish borrowings also generally bear Indic morphology markers:

(5)

However, borrowed masculine nouns generally use borrowed inflexion. Such is the case for the Turkish borrowings ap-ora ‘pills’ (in ex. 2), dev-ora ‘giants’, eteklik-ora ‘long skirts’, and so on, which take an older language-contact plural, Romanian -uri. This phenomenon is found in many Romani dialects. The names bearing foreign morphology (often of Greek origin) are called xenoclitic and are distinguished from the oikoclitic names taking native morphology (for a detailed description of this complex system see Matras Reference Matras2002 and Elšík & Matras Reference Elšík and Matras2006).

Verb integration

Wichmann & Wohlgemuth Reference Wichmann, Wohlgemuth, Stolz, Bakker and Palomo2008 describe four strategies of loan verb integration that can be found crosslinguistically:

(a) “light verb strategy” for cases where a verb (usually ‘to do’) is required to accommodate the loan verb;

(b) “indirect insertion” for cases where an affix is used to accommodate the loan verb;

(c) “direct insertion” for “a process whereby the loan verb is plugged directly into the grammar of the target language with no morphological or syntactic accommodation” (Wichmann & Wohlgemuth Reference Wichmann, Wohlgemuth, Stolz, Bakker and Palomo2008:99).

(d) “paradigm transfer” for cases where the loan verb is accompanied by the verb morphology and its meanings.

Komotini Romani is one of a handful of languages that are known to borrow the verb together with the time, aspect, and person markers. This is characteristic of many Romani dialects: Vlax and Balkan Romani in contact with Turkish (e.g., Muzikanta, Nange, Varna Kalajdži; for a complete list see Friedman in press), but also Crimean Romani, as well as North Russian (Rusakov Reference Rusakov, Dahl and Koptjevskaja-Tamm2001) and Lithuanian Romani (see Elšik & Matras 2006:135). Yet the degree to which verb paradigm transfer occurs is quite variable across these dialects.

In KR, however, this process is considerably developed and involves a large number and a wide range of verbs, including ‘to talk’, ‘to tell’, ‘to understand’, ‘to think’, ‘to approach’, ‘to return’, ‘to wait’, ‘to start’, ‘to finish’, ‘to rest’, ‘to lie down’, ‘to get up’, ‘to touch’, ‘to read’, ‘to write’, ‘to count’, ‘to send’, ‘to shoot’, ‘to get dirty’, ‘to clean’, ‘to throw’, ‘to get undressed’, ‘to roast’, ‘to boil’, ‘to get married’, ‘to like’.

Almost all Turkish time, mode, and aspect markers, as well as person and number markers, accompany the Turkish verbs in KR. The progressive, for example, can be seen in the following excerpt:

(6) Excerpt from the tale “The Louse and the Rom” (Sentence 3); http://lacito.vjf.cnrs.fr/archivage/languages/Romani_fr.htm.

Also subject to this process are the r-present (in ex. 2, konušur ‘speak’), the Turkish preterit -di (sevindi ‘he was happy’), imperative forms, the Turkish negator -ma-, and the Turkish future marker, seen in the example below:

(7) Excerpt from the tale “The Louse and the Rom” (Sentence 17); http://lacito.vjf.cnrs.fr/archivage/languages/Romani_fr.htm.

Variation exists for the expression of the optative: The Romani complementizer te occurs in some cases for Turkish loan verbs (with the present in te bekler ‘to wait’; te konošur ‘to talk’; with the progressive in te japištijorlar ‘to stick’), while, for other verbs, the Turkish optative marker -(y)A- is to be found (uzanayim ‘to lie down’).

Another loan verb integration phenomenon is very common in Romani dialects all over Europe and is known as the “loan verb markers” strategy (see Elšík & Matras Reference Elšík and Matras2006:324–33; “borrowing of borrowing patterns” in Wichmann & Wohlgemuth Reference Wichmann, Wohlgemuth, Stolz, Bakker and Palomo2008). Loan verb markers in Romani are often Greek-derived markers, maintained even when contact with Greek has ceased. Loan verb markers are also created from other contact languages, among which Turkish (e.g. -din in the Sepečides Romani dialect, Cech & Heinschnink Reference Cech and Heinschnink1996). Still, loan verb markers are not found for Turkish verbs in KR. KR speakers index such forms for the Christian Roma, as shown in the following example for the loan verb markers -is-ar (characteristic of Vlax Romani in general):

(8)

Even though this terminology is mostly applied to Romani, I believe that loan verb markers are currently found in Pomak. As shown in the following example, Pomak1 integrates Turkish verbs and adapts them to Slavic verb morphology, but the Turkish preterit marker –di is integrated in Pomak as part of the verb radical and loses its meaning:Footnote 4

(9)

This Turkish loan verb marker is also found in other Turkish verbs such as uidisvam ‘I am matching (the colors), I am spoiling someone’, pisledisvam ‘I am soiling’.

The Komotini Romani fused lect in the mixed languages debate

Literature on mixed languages has developed considerably over recent decades and has given rise to an interesting debate on the criteria that should define mixed languages, the mechanisms that lead to their creation, and the different types of mixed languages. A satisfactory definition of mixed languages has yet to be established, owing to the variety of situations and probably also to the need for more detailed case studies. The number of borrowings and the type of lexicon (core or peripheral) are important elements for the distinction between languages that are mixed and those that have “heavily borrowed.” According to Bakker & Mous (Reference Bakker, Mous, Bakker and Mous1994:5), in cases of heavy borrowing, 45% of the lexicon is borrowed, while in mixed languages the proportion may rise to 90%. Intermediate categories, according to the authors, are not frequent. More importantly, the type of mixture is significant in that the elements of the two languages generally remain recognizable (Bakker Reference Bakker, Bakker and Mous1994).

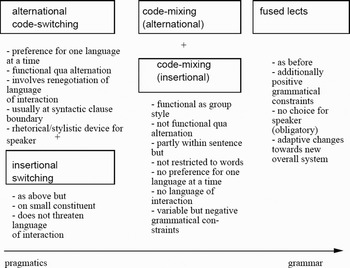

According to Auer Reference Auer1998, mixed languages are extreme cases of fused lects. I suggest here drawing a line between “fused lects,” applying to cases of languages on their way to becoming mixed, and “mixed languages,” for cases where the process is already complete. Indeed, although KR shares some features with mixed languages, it does not belong to that group (borrowed items are not as high as 90%). But KR uses a high number of Turkish verbs, together with their time and aspect markers, and the main process is code compartmentalization (Friedman in press). As a fused lect, KR could actually provide evidence to support the role of codeswitching in the creation of mixed languages, as argued by Thomason Reference Thomason and Silva-Corvalàn1995 and Auer Reference Auer1998 (see Figure 3). Although the process of language mixing is not completed, the systematic paradigm transfer of loan verbs looks like the grammaticalization of codeswitching insertions for which the speakers would have “licensed” permanent use, in Matras's terms. Current Greek codeswitching insertions, with nouns being integrated along with their native Greek inflexions, could constitute the first step in this process, since they are so similar to the Turkish insertions. Only a detailed linguistic and historical analysis makes it possible to differentiate between the Greek and the Turkish insertions, in showing that the former have acquired “permanent” and stabilized status under specific social circumstances and bilingual practices.

Figure 3: Auer's bilingual speech typology (from Auer Reference Auer1998:23).

A correlation between mixed languages and language contact ecology has been suggested both by Bakker Reference Bakker, Bakker and Mous1994 and Thomason Reference Thomason and Silva-Corvalàn1995. Bakker (Reference Bakker, Bakker and Mous1994:24), for example, has suggested two types of “intertwined” languages defined by sociohistorical criteria:

1. languages created by former nomadic groups during shift who use it as a secret language for business, e.g. Anglo-Romani;

2. languages in mixed households, e.g. Michif.

Compared to mixed languages, the KR fused lect shares common features with those of the first category, as they were produced in an itinerant group. However, unlike those languages, KR was not used as a secret language and, more importantly, it was not created during a shift, thus pointing at those factors being relevant for the creation of mixed languages.

Thomason Reference Thomason and Silva-Corvalàn1995 also relates sociohistorical characteristics of speech communities with linguistic processes of language mixing:

1. The mixed languages created in existent groups show replacement of grammar as a linguistic process (cf. Ma'a/Mbugu, Anglo-Romani).

2. The mixed languages that arise in newly rapidly formed groups show compartmentalization of the two languages' elements (cf. Media Lengua, Michif).

Although KR was created in an already existent group, as a language related to the group's identity, it does not correlate with the process of grammatical replacement. On the contrary, the process applied is compartmentalization, as found in newly formed groups. In other words, KR and Michif share the compartmentalization process (although, as already mentioned, it is not as advanced in KR as in Michif) but not the social characteristics (mixed marriages, newly formed group).

KR and the other Turkish-Romani dialects differ from other mixed Romani dialects in the mechanisms they use. As shown above, KR proceeds by compartmentalization while most mixed Romani dialects proceed using a combination of grammar from language A and lexicon from language B (see Boretzky & Igla Reference Boretzky, Igla, Bakker and Mous1994 for a review of mixed Romani dialects). The following is an example of a mixed Greek-Romani variety (Indic in bold), where the lexicon is Romani and the morphology mainly Greek:

(10)

Moreover, unlike most mixed Romani languages, for which language shift has been the main mechanism, KR is a stabilized fused lect, used in everyday domestic and group communication in all domains and transmitted as such to children.

ECOLOGY AS A COMPREHENSIVE BILINGUAL SPEECH FRAMEWORK

In the earliest contact setting, within the Ottoman Empire and for almost five centuries, Turkish was the lingua franca, the language of communication and trade in the Balkans. In a second contact setting, within the Greek state, which for Thrace started in 1923 and continues today, Turkish became a minority language. In Thrace, Turkish continues to be used in colloquial and trade-related contexts and has also become the language of education for the local Muslim population (1923), alongside Greek.

For both the Pomaks and the Roma, Turkish was the dominant and prestige language, and many communities shifted to Turkish during the second half of the 20th century. However, as shown in the preceding section, the contact outcomes were different for the two languages under study. A closer look at the patterns of bilingualism and the patterns of language use in a historical perspective shows that contact with Turkish materialized in considerably different ways for the Pomaks and the Roma. Even though the two communities show some similarities in their social characteristics (both are small, tightly knit communities, with little intermarriage with outsiders), one can isolate the divergent factors in the Roma and Pomak ecologies that can help us understand the differences observed in the linguistic outcomes. These factors include the geographical setting of their traditional habitats (mountains vs. urban habitat) and the impact on the communities' social structure (isolated, with little outside contact vs. daily contact despite marginalization), the socio-professional occupations (cattle breeders and farmers vs. craftsmen and merchants) and their mobility (itinerant vs. semi-sedentary), and what those factors imply for language contact patterns (extensive vs. limited bilingualism; intensive vs. occasional use). I will also pay close attention to the role of religion and other cultural practices for the impact they have on language contact (institutional language contact through religion and education) related to the identity issues and linguistic representations (prestige) that affect the intensity of bilingualism and that in many cases lead to shift.

Roma language contact ecology and patterns of bilingualism

Thomason Reference Thomason2001 observes that, unlike pidgins and creoles, bilingual mixed languages are developed in widespread bilingual settings. On a more specific point, Wichmann & Wohlgemuth (Reference Wichmann, Wohlgemuth, Stolz, Bakker and Palomo2008: 12) propose a correlation between loan verb integration strategies and the “degrees to which speakers of the target language are exposed to the source language(s)”. The paradigm transfer of loan verbs, found in KR, is at the top of the hierarchy, related to the most intensive contact. Indeed, Komotini Roma most probably presented extensive and intensive long-term bilingualism with Turkish, the vehicular language of the Ottoman Empire: extensive in that bilingualism with Turkish concerned a large part of the speech community, women and children included; intensive, in that Turkish was used frequently in everyday interaction and in highly argumentative contexts.

The Komotini Roma's socio-professional activities and mobility also furnish elements for understanding this sort of language contact. Demographic information concerning the Ottoman period is scarce, especially for populations such as the Roma, traditionally living at the margins of the administration. But linguistic and ethnographic evidence seems to indicate that the Komotini Roma were mostly itinerant craftsmen, at least during late Ottoman times, while their status in earlier times is unclear (it has long been believed that Vlax Roma were submitted to serfdom while residing in the actual area of Romania). The elders report traditional occupations just as commonly found for the Southern Vlax Roma in general: According to them, their ancestors used to work as džambazi, horse and donkey traders; tarahči, comb makers (wood combs for animals and cow-bone combs for people); others would make sieves, porizena, of lambskin. Women would also practice fortunetelling. Those professional activities implied frequent contact with outsiders and required an argumentative discourse in order to convince and negotiate with the clients.

Matras's (Reference Matras, Halwachs, Schrammel and Ambrosch2005: 29) diffusion model for Romani dialect classification shows that itinerant Roma “appear to have traveled within the containment of specific regions” which correspond roughly to the Ottoman and the Austrian zones of influence. The change in political boundaries that resulted from the formation of the modern Greek state had an impact on the Komotini Roma's mobility (as was the case for other nomads, e.g. for the Greek-speaking Sarakatsani shepherds). The Komotini Roma became semi-sedentary and adjusted their working activities to the new borders. Modern Greek was added to their linguistic competencies, while Turkish remained their trade language in Thrace. Today, Roma of the Komotini neighborhood work as seasonal laborers in agriculture, trade (although the richest and most powerful market merchants are the Christian Roma settled in Kimeria, near Xanthi), or occasionally as cleaning staff for domestic or city services. Even though Komotini Roma are currently settled, they remain semi-sedentary, in most cases for professional reasons.

Traditionally, the whole Roma family participated in the nomadic lifestyle. Intensive codeswitching probably took place at that period and then, at some point, as Thomason Reference Thomason2001 suggests, the codeswitching became fossilized by acquiring the function of indexing the specific group. “Commercial nomadic” groups are also known for developing specific ingroup languages (see Glemch & Glemch Reference Glemch, Glemch and Rao1987). Indeed, the Komotini Roma rely on their Turkish identity for both group and individual naming. Muslim Roma have Turkish first and last names, and they refer to their group as xoraxane roma ‘Muslim, Turkish Roma’. Xoraxane indicates their Muslim religion, indexing them in the larger group of Muslim Roma in the Balkans, and distinguishing them from the dasikane roma ‘Christian Roma, Greek Roma’.Footnote 5 The xoraxane women usually wear the ‘sarouel’, sosten, distinguishing themselves from the Christian Roma who wear long, wide skirts or eteklikora (the younger ones can also be dressed in a “Western manner”).Footnote 6

The “license” to mix the two languages goes back to a long tradition of multilingualism that can be considered part of Roma identity. Traces of the various contacts in Roma history are still to be found in the modern dialects (for example, from old contact languages such as Greek, Romanian, and Slavic). The processes used for this mixing seem quite conscious, in accordance with recent approaches that see the bilingual speaker as an active “language builder” (Hagège Reference Hagège1993). Borrowings are marked through specific strategies that allow them to be integrated and yet to remain distinctive and identifiable centuries after the contact has ceased. In the case of KR, those strategies are the use of xenoclitic nouns and of paradigm transfer in verb borrowing. This linguistic compartmentalization strategy also reflects Roma social organization and their rules toward outsiders. While Roma were in constant contact with outsiders and their economy relied on trade and services with the gadže ‘non-Roma’, at the same time many Roma communities had strict rules of avoidance of outsiders. The most notorious expression of it is the marime, a term used by the Vlax Roma. Marime refers to a complex set of norms, varying from one group to another, defining “uncleanness,” and to the expulsion imposed in case of violation of those rules or for behavior disruptive to the community (Weyrauch Reference Weyrauch2001). According to Miller:

Marime developed as an ecological response to nomadic and segregated living in arrangements in wagons and tents when certain rules concerning health, sexual expression and social intercourse with outsiders proved adaptive. (Miller Reference Miller and Rehfisch1975)

Marime regulated contact among Roma as well as contact with non-Roma, the gadze. Defilement by contact with non-Roma can be seen in the traditional distance maintained from religious, educational, or health institutions. Even today, 60% of Roma children in this small neighborhood of Komotini never attend primary school, a very low percentage compared to the Christian Greek Roma in other parts of Greece. This stems both from the inadequate policies of the local Greek administration, and from the traditional distance from school that results from a perceived threat by assimilation policies to Roma culture. Contact with Muslim institutions is similar: Mosques are not found even in neighborhoods of 4,000 inhabitants, such as Drosero in Xanthi. Muslim holidays, such as Šeker Bairam or Kurban Bairam, are seldom celebrated, and the Roma I interviewed think of them as quite recent (later than the 1960s).

Even though such marginalization is characteristic of the Roma in Europe and throughout their history, cases of relative integration in modern states are not uncommon. For example, the sedentary Sepečides Roma in Turkey show “an increasing number of exogamic marriages” (Cech & Heinschnink Reference Cech and Heinschnink1996:2). Children attend Turkish schools, and the group is shifting to Turkish. Another example of integration is the case of the Ajia Varvara Roma, living in a mixed Greek and Roma neighborhood in Athens, where children attend primary school (Kozaitis Reference Kozaitis2002).

Pomak language contact ecology and patterns of bilingualism

During the Ottoman period the Pomak speech community was composed of a majority of monolingual speakers with practically no direct contact with Turkish. Turkish was introduced through Koranic schools and through members of the community who traveled. During the modern contact setting within the Greek state, contact with Turkish was intensified through primary school, mass media, and increasing contact situations (travel, migration, and urbanization). This type of low-level contact, which gave rise to few lexical borrowings, can be understood through the speech community's social and geographical environment.

Pomaks were traditionally semi-sedentary cattle breeders and farmers, living in the Rhodope Mountains. Some of those areas remain hard to reach even today, especially in winter. Pomaks would practice seasonal grazing, spending winters in their villages and migrating in the summer to nearby summer settlements, along with their families and cattle. This way of life involved little contact with outsiders, and effective bilingualism with Turkish was limited to the elite and those few who for professional reasons were part of the Turkish-speaking networks. This isolation continued within the Greek state, during the Cold War, owing to the area's status as an epitirumeni zoni ‘surveillance zone’, implying military control of the borders with neighboring Communist countries (Bulgaria, in this area). In practice, this meant limited access to the closest cities. Today the situation has considerably changed and contacts with the city of Xanthi have intensified, making it possible for many men to work in the city and to continue living in the village.

Since Ottoman times, Pomaks have been in contact with Turkish mainly through religion and school. This strong Muslim culture is reflected in the type of borrowings found: Pomak speakers use a high number of religious terms for greetings and expressing thanks, either borrowings from Turkish or terms used broadly in Muslim-Arabic culture and borrowed through Turkish, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. “Emblematic” borrowings from Turkish in Pomak1.

1Muslim Slavic speakers are also found in Bulgaria, naming their language Bulgarian, Pomak or Rhodopean.

Religion was, and still is, an important aspect of Pomak identity. Pomaks in Greece distinguish themselves from the “Bulgarians,” the neighboring Christian Slavs, according to the Ottoman administrative organization based on religion. Today most Pomak villages have a mosque, with Pomak imams and regional muftis educated in Arab countries. The hadj pilgrimage to Mecca is prestigious and widely practiced; religious events are carefully observed, and married women dress in the Muslim way, covering their hair with scarves, the mumie or mandil replacing the traditional white testemel brought from Mecca, and wearing long clothes to cover their bodies. Boys and girls go to the Koranic school (kuran kursu), and even though Koranic Arabic is taught, Turkish is the classroom language. Turkish is also, together with Greek, the language of minority primary school education, even though the number of students attending monolingual Greek schools has considerably increased in the past decade owing to permanent migration to Xanthi and families' seeking the best schools. It is important to keep in mind that until very recently, education concerned only a small part of the community, and that until the early 1990s girls would not pursue their studies beyond primary school.

Another source of contact with Turkish is recent migration for work and education in Turkey and Germany. In the 1980s the migrants would settle in Germany with their families; they would become integrated in immigrant Turkish communities and would frequently shift to Turkish. Contact between relatives would remain intense, either by telephone or visits. In the past decade, changes in the politics of labor migration have made it rare for whole families to migrate to Germany. Today, young men have working contracts limited to a few months, after which they return to their original villages and take up other sorts of activities.

Occasional visits to neighboring Turkey are common, for shopping or tourism, facilitated by the Egnatia road. Turkish television and music are also influential sources of contact: Older women who have not attended school or had any mobility outside their villages point to television as an influential source of contact with Turkish.

Typological factors

In parallel with the identification of social factors, studies in contact linguistics have examined the typological parameters that influence contact-induced phenomena. Poplack & Sankoff Reference Poplack, Sankoff, Ammon, Dittmar and Mattheier1988 argue that typologically similar languages will tend to produce alternational codeswitching, while typologically distinct languages produce insertional codeswitching. Muysken Reference Muysken2000 shows that if an agglutinative language is the matrix language, then the resulting codeswitching will be insertional; if both languages are flectional, alternational codeswitching will be the result. Winford Reference Winford2003 also underlines that typological distance in contact settings determines the linguistic results to a great degree.

In the case presented here, however, typological factors do not seem to be relevant, since both recipient languages are flectional, and the source language is Turkish, an agglutinative language. For example, the types of time, mood, and aspect (TMA) markers do not determine either the paradigm transfer used in Romani or the integration strategy used in Pomak: Romani ka and Pomak še future markers are enclitic to the verb in both cases. But in Romani, Turkish verbs are borrowed along with the Turkish future marker, while in Pomak the verb is integrated into Pomak morphology and maintains the Pomak ‘will’ marker. Moreover, evidence exists for paradigm transfer of loan verbs in Romani with Russian – a flectional language – as the donor language (Rusakov Reference Rusakov, Dahl and Koptjevskaja-Tamm2001).

Paradigm transfer for loan verbs has also been considered from a typological perspective. Through a rich sample of Romani dialects, Elšik & Matras (2006:134–36) show, for example, that third person markers are more likely to be borrowed, followed by second person and then first person markers. Person and number markers also seem to depend on aspect markers. Note that in KR all person markers are transferred with the Turkish loan verb. Based on available data from other Romani dialects in the Balkans, Friedman (in press) proposes a hierarchy of Turkish TMA markers accompanying Turkish loan verbs in Romani (note that KR is very advanced along this scale):

preterit < present [-r ~ -yor] < clitic cop. idi < optative < mIş-past < future & negation < infinitive

Conclusion

In this article, I have compared two sorts of close-knit speech communities showing long-term contact with Turkish. In both cases Turkish is the dominant, prestigious language and, more significantly, an important language for the group's identity. Despite these shared features, the outcomes of language contact differ. Pomak shows a low level of borrowing, though of an often emblematic, religious type, and infrequent, participant-related codeswitching. Romani, on the other hand, shows a high number of borrowings and can be described as a fused lect in Auer's terminology.

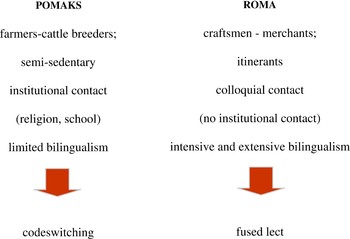

The aim of this article was to show that study of the contact ecology of the two communities leads to a better understanding of these differences. It shows the Roma itinerant craftsmen experienced intensive and extensive contact with Turkish, while Pomaks, having long been isolated, semi-sedentary cattle breeders, had little contact with Turkish, and mostly through institutions (religion and education), in what may be considered a normative context. Figure 4 presents an implicational scale showing how the speech community's professional profile and mobility determine the language contact settings, and how those in turn shape the resulting type of bilingualism and bilingual discourse. The factors shown in Figure 4 should not be viewed individually, but as a correlation of factors that are likely to produce a certain type of bilingual speech.

Figure 4: Pomak and Roma ecology and bilingual speech with Turkish.

This case study does not aim to produce a novel universal contact typology, but rather to confirm and specify the existing typologies suggested by Thomason & Kaufman Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988, Loveday Reference Loveday1996, and Winford Reference Winford2003. More specifically, it supports the observation that some social correlations may favor some types of contact outcomes: Institutional and infrequent bilingualism of isolated speech communities is most likely to produce some borrowings and no further significant impact on the language; a tight-knit speech community with a long bilingual tradition, for commercial purposes and involving child bilingualism, may give rise to more complex types of language mixing.

This comparison between two radically different communities attempts to provide a clear example of the role that language ecology plays in multilingual settings. What would be more challenging is a comparison among various Romani dialects in contact with Turkish or other languages (Greek, Slavic, Romanian), in order to identify the relevant external parameters. This supposes first-hand, detailed knowledge of local conditions, making such comparison extremely difficult to carry out given the complexity of each situation.

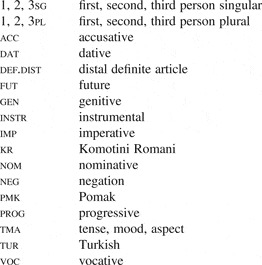

APPENDIX: ABBREVIATIONS USED IN EXCERPTS