Surgical-site infections (SSIs) are the second most common hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) reported in Europe. 1,Reference Plachouras, Karki and Hansen2 They are associated with significantly increased morbidity and mortality, length of stay, and cost of hospitalization. Reference de Lissovoy, Fraeman, Hutchins, Murphy, Song and Vaughn3,Reference Astagneau, Rioux, Golliot, Brucker and Group4 In 2017, 10,149 SSIs were reported as complications in 648,512 surgical procedures in 13 European countries. 5 According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), ~16,049 deaths per year and 58.2 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) per 100,000 persons were attributed to SSIs in 2011–2012. Reference Cassini, Plachouras and Eckmanns6

In fact, SSIs are highly preventable. One study estimated that up to 60% of SSIs can be prevented through the use of evidence-based guidelines and strategies. Reference Anderson, Podgorny and Berrios-Torres7 One such strategy is the administration of perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis (PAP). Reference Bowater, Stirling and Lilford8 Although administration of PAP for 24 hours after surgery is considered sufficient, Reference Allegranzi, Bischoff and de Jonge9 prolonged duration (>1 day) in more than half of surgical prophylaxis courses in European countries was recorded in a recent point prevalence study (PPS). Reference Plachouras, Karki and Hansen2 Consequently, PAP is also one of the most common drivers of antimicrobial prescribing in Europe; it contributes to the increase in both antimicrobial consumption and the subsequent emergence of antimicrobial resistance. 1

Although several guidelines are available for appropriate administration of PAP, Reference Page, Bohnen, Fletcher, McManus, Solomkin and Wittmann10–16 adherence to these guidelines varies across countries and settings, and many studies have reported significant noncompliance among surgeons. Reference Tourmousoglou, Yiannakopoulou, Kalapothaki, Bramis and St Papadopoulos17–Reference Parulekar, Soman, Singhal, Rodrigues, Dastur and Mehta23 Recent evidence suggests that noncompliance with guidelines mainly occurs in the duration of PAP and, to a lesser extent, in the type of antimicrobial prescribed or in the time of administration. Reference Tourmousoglou, Yiannakopoulou, Kalapothaki, Bramis and St Papadopoulos17,Reference Miliani, L’Heriteau, Astagneau and Group18 All 3 factors (duration, type of antimicrobial, and time of administration) represent opportunities for meaningful improvement in the administration of surgical prophylaxis to limit unwanted effects of antimicrobial resistance. In the past, interventional studies have managed to increase the appropriateness of surgical prophylaxis in some settings, Reference van Kasteren, Kullberg, de Boer, Mintjes-de Groot and Gyssens19,Reference Dona, Luise and La Pergola24–Reference Knox and Edye30 but these studies have been limited, and most took place in single centers. Reference Dona, Luise and La Pergola24,Reference Murri, de Belvis and Fantoni26–Reference Ozgun, Ertugrul, Soyder, Ozturk and Aydemir28,Reference Knox and Edye30

According to a recent ECDC PPS, PAP is administered for >1 day in >70% of surgeries in Greece. Reference Plachouras, Karki and Hansen2 Low compliance with national guidelines was identified in adults (36.3%), and very low compliance with international guidelines was identified in children (5.6%) Reference Tourmousoglou, Yiannakopoulou, Kalapothaki, Bramis and St Papadopoulos17,Reference Dimopoulou, Papanikolaou, Kourlaba, Kopsidas, Coffin and Zaoutis20 in the 2 single-center studies that have been conducted in Greece, mainly due to low compliance with appropriate duration. In Greece, limited data exist on active PAP surveillance, and ours is the first study to develop and implement an intervention for PAP in a Greek setting.

In this study, we audited clinical practice and developed and implemented a multimodal intervention on the appropriate use of PAP in elective surgical procedures in adult surgical departments across Greece.

Methods

We conducted a prospective, multicenter, active surveillance study on PAP before and after the implementation of an intervention. A national initiative, Preventing Hospital-Acquired Infections in Greece (PHiG), was developed; one of its aims is to improve the appropriate use of PAP in Greek surgery departments. The following surgery departments from 3 major Greek hospitals participated (2 in Athens and 1 in Thessaloniki): general surgery (n = 2), orthopedic (n = 2), cardiothoracic surgery (n = 1), neurosurgery (n = 1), and urology (n = 1). Patients admitted to these departments who underwent the following surgical procedures were included: coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), valve replacement, hip or knee replacement, cholecystectomy, inguinal hernia repair, craniotomy, intracranial pressure catheter placement, or prostatectomy. Patients treated with antimicrobials for a possible infection before surgery were excluded from this study.

The study was organized in 2 phases. Phase 1 included a baseline audit of PAP from September 2016 until May 2017. In phase 2 (June 2017 to June 2018), a multimodal intervention customized to each surgery department was implemented while active surveillance of PAP continued. Cases recorded in June 2017 were not included in the analysis because the intervention was introduced in surgical departments during this month.

A multidisciplinary core team including an infectious disease specialist, an infection control specialist, and a surgeon was formulated in each hospital and was supported both by the institutional infection control committee and the PHiG initiative. An initial meeting of each core team with surgeons was held in each department, and the dedicated PAP data collection form was introduced during phase 1. An on-site investigator was assigned to each department. All investigators were trained in the methodology used by 4 experienced infection prevention specialists (ie, the PHiG initiative), who also monitored the data collection and the consistent application of methodology. A data collection tool was designed specifically for the active surveillance of PAP and was used by on-site investigators. This form included data and information about patient demographics and underlying conditions; surgical procedures; antimicrobial agents used for PAP, prescribed after surgical procedures, and prescribed after discharge; and the occurrence of SSIs. Data on the occurrence of SSIs after a patient was discharged were collected via phone communication by on-site investigators.

The main outcomes studied were appropriateness of antimicrobial agents, appropriateness of timing, and appropriateness of duration (Table 1), according to the international guidelines of American Society of Health System Pharmacists Reference Bratzler, Dellinger and Olsen14 and the local guidelines for each hospital. Any occurrence of SSI (Table 1) before or after the implementation of the intervention was also documented.

Table 1. Definitions

Note. PAP, perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis; SSI, surgical site infection; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting.

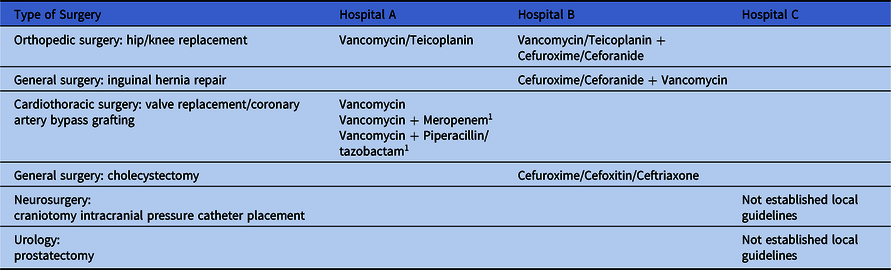

In this study, we followed the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists’ international clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Reference Bratzler, Dellinger and Olsen14 Each participating surgical department was asked to provide its local guidelines for PAP, if available. Of the 3 hospitals, 2 had their own local PAP guidelines (Table 2).

Table 2. Local Perioperative Antimicrobial Prophylaxis Guidelines

1 Only when time between admission and surgery was ≥3 days.

A multimodal intervention customized to the needs of each department was designed and implemented in collaboration with infection prevention specialists, surgeons, and hospitals’ infection control teams. The intervention strategy included educational lectures as well as audit and feedback, and it was targeted to 3 specific objectives: (1) use of the appropriate antimicrobial agent, (2) appropriate time of administration, and (3) appropriate duration of PAP. All departments received a feedback report with the results of baseline surveillance data, including benchmarking data among the different hospitals. A meeting of the core team with surgeons was held in each department early in phase 2 to discuss the results of baseline surveillance; to present the international guidelines and, if available, local guidelines; and to organize a plan for action. In addition to this meeting, educational meetings for all surgeons in the participating departments were regularly organized. The audit of PAP by on-site investigators and feedback to surgeons continued, including a report with benchmarking data every 6 months. The effect of the intervention on all aspects of PAP and occurrence of SSI was evaluated.

Nominal variables are presented with absolute and relative frequencies, and continuous variables are presented with mean and standard deviation. The association between the intervention period as well as patient’s profile and the appropriate use of PAP was evaluated using the χ Reference Plachouras, Karki and Hansen2 test of independence. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the impact of the intervention on the appropriateness of PAP, taking into consideration patient’s profile and possible confounders. Results are presented with odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The level of statistical significance was set to α = 0.05. Analyses were conducted using STATA SE version 13 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX). The power calculation for the evaluation of our statistically significant findings regarding overall PAP was performed and the power detected was 99%.

The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committees of the 3 hospitals.

Results

During the study period (June 2016 to June 2018), 1,524 patients were identified for inclusion in the study (Fig. 1). After excluding patients who underwent surgical procedures during the month when the intervention was introduced, 1,447 patients (mean age, 66.5 years) were included in the analysis. Before the intervention, 768 surgical procedures were performed, compared with 679 after intervention (Table 3 and Fig. 1). Among surgical procedures, the most common was hip or knee replacement (N = 483), followed by cardiothoracic surgeries (CABG, valve replacement, or a combination of these, N = 429) (Table 3). Only 2 craniotomy surgeries were recorded after the intervention, and we excluded these from the analysis (Fig. 1). The characteristics of patients and surgical procedures before and after the intervention are presented in Table 3.

Fig. 1. Timeline of the study and applied interventions. *The 2 craniotomy surgeries that were recorded after the intervention were excluded from the analysis. N = 679 patients. Note. ID, infectious diseases; IC, infection control; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting.

Table 3. Patients’ and Surgical Procedures’ Characteristics Before and After the Intervention

aAt least 1 risk factor of the following neoplasia, transplant, diabetes, smoking, multiple trauma.

Overall compliance with PAP

The overall compliance for all departments before the intervention was low (N = 685, 28.2%). Wide variations among departments in overall compliance were documented both before and after the intervention, with compliance rates ranging from 0 to 86.9% before the intervention and from 0 to 100% after the intervention. Higher compliance was recorded with regard to the choice of antimicrobial agent used for PAP, while adherence to the appropriate time of administration and to the appropriate duration of PAP was significantly lower. The implementation of the intervention achieved an increase in overall compliance to 43.9% (N = 634; P < .001).

Appropriate antimicrobial agent

Across all departments, median compliance with the appropriate antimicrobial agent according to international guidelines increased from 89.6% (N = 688) to 96.3% (N = 654; P = .001) after the implementation of the intervention (Table 4). Although all departments already had a high compliance rate with the international PAP guidelines (>75%), better compliance was achieved in 4 of the 7 departments. The choice of appropriate antimicrobial agent increased significantly in 3 departments (departments 3, 4, and 5), but did not differ significantly before and after the intervention in departments 1 and 7. In department 6, no surgical procedures were recorded after the intervention (Table 4).

Table 4. Appropriate Perioperative Antimicrobial Prophylaxis and Surgical Site Infection Rates in Participating Departments Before and After the Intervention

Note. NA, a statistical test could not be applied.

Adherence to local PAP guidelines before the intervention was significantly lower than adherence to international guidelines, with a compliance rate of 42.9% (N = 297) across all departments, but a significant increase to 57.8% (N = 376; P = .001) was achieved. Major differences among departments were recorded. In 2 departments, compliance with local guidelines was not measured because departments did not have established local guidelines for PAP administration.

In 2 other departments (departments 4 and 5), an increase in adherence to local guidelines was achieved simultaneously with higher adherence to international guidelines (Table 4). In department 1, glycopeptides were primarily used for surgical prophylaxis in hip or knee replacements both before and after the intervention (Table 5), as suggested by international guidelines; whereas in hospital B’s local guidelines, a combination of glycopeptide with second-generation cephalosporins was the antibiotic regimen of choice (Table 2). In departments 2 and 3, although a statistically not significant decrease in compliance was observed, compliance with the international guidelines improved (Table 4). This may be explained by the fact that after the intervention, surgeons used second-generation cephalosporins in inguinal hernia repairs more often than they used combinations of second-generation cephalosporins with glycopeptides, as suggested by their local guidelines.

Table 5. Most Commonly Used Antibiotic Agents for Perioperative Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Different Surgical Procedures Before and After the Intervention

The most common antibiotics used for surgical prophylaxis in every surgical procedure are summarized in Table 5.

Appropriate time of administration

In 4 of the 7 departments, timing of administration was appropriate in >90% of surgical procedures in the baseline period. Nevertheless, a slight decrease in adherence to appropriate administration time was observed from 78.1% (N = 721) to 74.9% (N = 666; P = .138). In most of the departments, appropriateness of timing improved after intervention. Departments 1 and 7, which had very low compliance before the intervention, demonstrated a significant increase in appropriate timing of PAP, from 44.3% (N = 79) to 73% (N = 100; P = .001) and from 20.4% (N = 49) to 60% (N = 25; P = .001), respectively. However, in department 5, a statistically significant decrease was observed (Table 4).

Appropriate duration

Compliance with appropriate duration of PAP varied among participating departments. In 5 of the 7 departments, adherence to guidelines for PAP duration was substantially low. Among these 5 departments, 3 achieved a statistically significant increase in compliance with the duration. A higher compliance rate from 33.7% (N = 729) to 60.3% (N = 642; P = .001) across all departments after the intervention was observed as well (Table 4).

Mean duration of PAP administration showed great variation among departments, with a range from 1 to 21.4 days. An overall significant decrease in the mean days of prophylaxis across all departments from 5.3 to 3.5 days was noted (P = .001). All but one department achieved a shorter duration of PAP, and most (departments 1, 2, 3, and 5) managed to limit PAP administration to ~2 days. Although a decrease from 21.4 to 15.2 days of PAP administration was achieved in department 7, all patients continued to receive excessively prolonged surgical prophylaxis after the intervention.

Multivariate analysis

After adjustment of possible confounders in the multivariable analysis, the intervention had a positive impact on the appropriate administration of PAP. After the implementation of the intervention, it was 2.3 times more likely for participating departments to administer the appropriate antimicrobial agent and 14.7 times more likely to administer it for the appropriate duration. In general, it was 5.3 times more likely that an overall appropriate PAP was achieved after the intervention (Table 6).

Table 6. Impact of Intervention on the Appropriateness of Perioperative Antimicrobial Prophylaxis

Note. CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

a Could not be estimated.

b At least 1 risk factor of the following: neoplasia, transplant, diabetes, smoking, multiple trauma.

Surgical site infections

The occurrence of SSIs decreased from 6.9% (N = 666) to 4% (N = 574) after the implementation of the intervention (P = .026). Among the 40 patients who developed an SSI and for which information for all parameters of PAP was available for evaluation; only 6 were administered overall appropriate PAP.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first multicenter, prospective, active surveillance and interventional study on PAP in surgical departments in Greece. To date, studies on PAP in Greece have included only 2 single-center studies, one of which was carried out only in pediatric patients. Reference Tourmousoglou, Yiannakopoulou, Kalapothaki, Bramis and St Papadopoulos17,Reference Dimopoulou, Papanikolaou, Kourlaba, Kopsidas, Coffin and Zaoutis20 Although a high compliance rate in the choice of antimicrobial agent and the timing of PAP administration was recorded in most participating departments in the baseline period of our study, overall compliance was low. A targeted and customized intervention including education, audit, and accompanying feedback resulted in significant increase in both overall compliance as well as compliance with appropriate antimicrobial agent used, appropriate timing of administration, and appropriate duration of PAP in most departments, without an increase in the rate of SSIs. The results of our study suggest that an antimicrobial stewardship intervention targeted to PAP can significantly contribute to increasing the appropriateness of antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery.

The successful intervention implemented in our study was based on a multimodal strategy, as suggested by WHO. The intervention included leadership from a multidisciplinary team, education, audit and feedback, and involved all aspects of PAP (antibiotic choice, timing, and duration). Interventions organized with similar core components have successfully increased appropriate administration of PAP in other settings as well. Reference Saied, Hafez and Kandeel25,Reference Bozkurt, Kaya and Gulsun27,Reference van Kasteren, Mannien and Kullberg29 By comparison, interventional studies based solely on education did not succeed in improving compliance in PAP, and thus are not recommended by the IDSA. Reference Ozgun, Ertugrul, Soyder, Ozturk and Aydemir28,Reference Knox and Edye30,Reference Barlam, Cosgrove and Abbo31 Formulation of a multidisciplinary team and establishment of continuous collaboration with surgeons is a key for successful implementation of such interventions.

Adherence to appropriate antimicrobial agent used for surgical prophylaxis was easier to achieve. All departments participating in our study had compliance rates >75% in terms of antimicrobial choice at baseline period. Such high compliance with the appropriateness of antimicrobial agents used for surgical prophylaxis has been documented in several other studies. Reference Tourmousoglou, Yiannakopoulou, Kalapothaki, Bramis and St Papadopoulos17–Reference van Kasteren, Kullberg, de Boer, Mintjes-de Groot and Gyssens19,Reference Dona, Luise and La Pergola24,Reference Murri, de Belvis and Fantoni26,Reference Bozkurt, Kaya and Gulsun27 Meanwhile, following our intervention, there was a further increase in compliance for the appropriate choice of antimicrobial agents during surgery. This finding is also in line with observations from other countries after the implementation of similar interventions targeting PAP. Reference Dona, Luise and La Pergola24,Reference Bozkurt, Kaya and Gulsun27,Reference van Kasteren, Mannien and Kullberg29 These compliance rates were close to compliance rates observed in other countries before and after the implementation of interventions for the improvement of appropriate PAP administration. Reference Dona, Luise and La Pergola24,Reference Bozkurt, Kaya and Gulsun27,Reference van Kasteren, Mannien and Kullberg29

An increase in compliance with appropriate timing of antimicrobial administration during surgery was observed in most departments, except the orthopedic surgical procedures. Orthopedic surgeons used more often glycopeptides for surgical prophylaxis; notably, however, the antibiotic was not administered 60–120 min prior to surgery, as suggested by guidelines. Increasing appropriate duration of PAP has been shown to be both the most difficult and the most important target in interventional studies in this area. Reference Dona, Luise and La Pergola24,Reference Bozkurt, Kaya and Gulsun27,Reference van Kasteren, Mannien and Kullberg29 In our study, the appropriate duration of PAP was 14.7 times more likely to be administered after the intervention. However, PAP duration varied greatly among surgical departments; the baseline mean duration of PAP ranged from 1.3 to 21.4 days and was reduced to a range of 1–15.2 days after the intervention. Existing research on PAP duration in Europe, combined with the results of this study, supports the concept that PAP should be prioritized as a highly significant component of antimicrobial stewardship programs across hospitals. Reference Plachouras, Karki and Hansen2,Reference Hohmann, Eickhoff, Radziwill and Schulz22,Reference Versporten, Zarb and Caniaux32

Overall compliance rates following PAP intervention varied significantly among different surgical departments in our study. Considering that this study was organized within a network (PHiG) and used a multidisciplinary intervention customized for each surgical department, the role of implementation science in designing PAP interventions cannot be overemphasized. It is now apparent that interventions on optimization of PAP administration do work, Reference Dona, Luise and La Pergola24–Reference Bozkurt, Kaya and Gulsun27,Reference van Kasteren, Mannien and Kullberg29 but there is still a need to evaluate which implementation strategy works better and within a cost-effectiveness approach.

Our study has several limitations. Because our study was conducted in only 3 hospitals and focused on selective surgeries, its generalizability to different settings, countries, and surgical procedures may be limited. However, given that the participating departments were in referral hospitals in the 2 largest cities in Greece, we believe that our results can be generalized in Greece. In addition, the compliance rates we found may be subject to surveillance bias. Finally, our study may also be limited by the fact that our intervention did not include creating an enabling environment and assigning PAP administration to the anesthesiologist, which is 1 of 5 modalities that have been identified to improve appropriateness of PAP. 12 If our intervention involved also these 2 components, it may have had an even higher impact on appropriateness of PAP. Despite this, our intervention did manage to improve appropriate administration of PAP.

In conclusion, our study showed that a multimodal intervention based on both education as well as audit and feedback can contribute significantly to improvement of appropriate PAP administration. However, this intervention still leaves significant opportunity for further improvement, particularly in terms of appropriate duration of prophylaxis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hippokration Hospital of Thessaloniki, Savvas Papachristou MD, and George Koudounas MD.

Financial support

This work is a part of a program that was funded by a grant of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.