Language, Gesture, and Drag

In the middle of Mark Morris's ballet Dido and Aeneas, set to the Henry Purcell opera of the same title, a female dancer mimes the story of the Greek goddess Diana and her unfortunate suitor, Actaeon. While hunting in the mountains, Actaeon catches sight of Diana bathing nude, and the fiercely chaste goddess transforms him into a stag; his own well-trained hounds, baying triumphantly, turn on their master. When the word “mountain” is sung, the dancer marks out two jagged peaks over her head with one hand. When the hunter Actaeon is mentioned by name, the dancer mimes a bow being arched and an arrow shot from it. Then, as the line “here, here, Actaeon met his fate,” is being sung, the dancer points one finger down at a spot on the ground, nodding emphatically. It was here, she is saying—right here, where I am pointing, see?

The rest of the dancers in the Mark Morris Dance Company are gathered around her in two diagonal lines; they repeat her series of movements, so that in case anyone in the audience has missed her gestures or their importance, nine dancers will do it again, three more times. What is exceptional about this is that, first of all, no one needs the meaning of “here, here” pointed out with this degree of emphasis. “Here, here” is a gesture with a indexical sense that extends to concert dance as well as to quotidian communication, and it is only one of many movements of this type in Dido and Aeneas. The act of pointing is so referential that it does not achieve what Susan Leigh Foster, distinguishing the modes of representation through which dance alludes to a world beyond the stage, calls the “imitative” mode of representation; the dancer just points to the real object of her unmistakable, solid, deictic referent (Foster Reference Foster1986, 66).

The pantomimic “hunter” gesture associated with Actaeon's name helps the audience to understand the dramatic irony of this story. The libretto doesn't make explicit that Actaeon's identity as a hunter brings the tragic fate of being ripped apart by his own hounds upon him. It is only the pantomimic hunting gesture of letting an arrow fly from a taut bowstring that clarifies this essential narrative element. The libretto—which was written in 1689 by Nahum Tate for “Mr. Josias Priest's Boarding School at Chelsey for Young Gentlewomen,” and thus strives hard for modesty (Acocella Reference Acocella1993, 98)—only recounts Actaeon's story allusively: “Oft she visits this lone mountain/Oft she bathes her in this fountain/Here, here Actaeon met his fate/Pursued by his own hounds/And after, after mortal wounds/Discovered too, too late.”Footnote 1 Morris's deictic and pantomimic vocabulary supplements the Actaeon text by linking Diana, the goddess of the hunt, with Acteon, the hunter she makes prey to his own hounds. The story hinges on the reversals of their shared identity as hunters: his glance pierces her modesty; ruthlessly, she sights him; he is changed in one terrible instant from man to stag; his bow clatters to the ground; he has trained his dogs entirely too well. It is Acteon's inability to call off his hounds—the futility of his gestures to communicate as clearly as verbal language—that marks the culmination of the story's tragic irony. For this reason, the more clearly and repeatedly the Acteon story is mimed, the more likely it is that the whole audience will come to understand the implications of reversed identities and gestural language—and the tragedy that it foreshadows for Dido and Aeneas, who are the ostensible audience for this nested subplot.

Finally, in the phrase “here, here, Actaeon met his fate,” there is a gesture associated with the word “fate”: “the dancer stretches his arms out sideways and up, twists his wrists, and splays his fingers,” in Joan Acocella's description (Acocella Reference Acocella1993, 142–143). In the case of the “fate” gesture, which cannot have a clear indexical or pantomimic referent as “here” and “hunter” do, an abstract action must somehow convey the concept of fate (see Photo 1). As Acocella elaborates,

The gesture has so much fateful poetry of its own—the long, outward stretch of the arms (fate controls the whole world), the raising of the arms (fate is directed by heaven), the muscular tension in the shoulders (fate is powerful), the spidery splay of the fingers (fate is terrible, or will be for Dido)—that the body can carry the weight of that meaning without our having to hear the word. (Acocella Reference Acocella1993, 143)

The word “fate” occurs seventeen times in Dido and Aeneas, and is eventually performed by everyone in the cast: sometimes one-handed, sometimes with both hands; at times facing the audience, at other times while walking offstage; and sometimes starkly against the air, sometimes pressed knowingly into the body of the dancer.

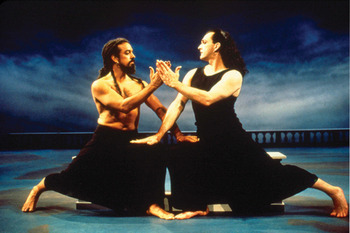

Photo 1. “Fate” gesture (Bradon McDonald and Company). Photo by MMDG/Costas.

These three levels of gestures—the indexical enactment of “here, here,” the supplemental pantomime of “Actaeon” as a hunter, and the poetic signifier assigned to “fate”—constitute a basic gestural vocabulary of Dido and Aeneas. Although a diverse audience will inevitably read this scene at different levels—some barely skimming the surface of a new story, some sinking into the pleasure of a familiar tale embellished by poetic movement—Dido and Aeneas works tirelessly to establish a unified kinetic language of its own, a more or less stable set of deictic and pantomimic gestures and movements that weave in and out of the text of the libretto.Footnote 2

Strictly speaking, as Randy Martin writes, “dance is unlike language,” because “movement lacks the discrete equivalents of sound-images that words provide” (Reference Martin and Foster1995, 109). However, Martin notes, there are certain dance forms that employ an established vocabulary of gestures and movement phrases—Indian kathak, mime sections in nineteenth-century story ballets,Footnote 3 Ghanaian dancing, etc.—that prompt an audience educated in the conventions of that particular genre to interpret the meaning of specific movements. There can be a connection between a gesture in dance and its semantic referent, but this depends on an active, trained, sensitive audience, and a set of conventions shared with that audience. As Foster has proposed, it is only the “literate dance viewers [who], like choreographers, ‘read’ dances by consciously utilizing their knowledge of composition to interpret the performance, and in this sense they perform the choreography along with the dancers” (Foster Reference Foster1986, 57; emphasis mine).

In Dido and Aeneas, Morris employs a movement vocabulary that speaks to a heterogeneous audience, engaging a broad range of “literacies.”Footnote 4 He relies heavily—and unfashionably, in the canon of postmodern dance—on mimetic gesture and repetition, turning his choreography into a kind of pluralistic pedagogy. It is a dance that matches gestures nearly one-to-one with the words being sung—and a dance that uses movement to enact allusive references that the libretto glides over. In the Laban-based catalogue of Preston-Dunlop and Sanchez-Colberg's Dance and the Performative, Morris's choreography is listed under the heading “words and movement” because he “extracts images from the words … [and] embodies [them] in the gestural part of his movement vocabulary” (Reference Preston-Dunlop and Sanchez-Colberg2002, 51).

This focus on legibility and the reiteration of codes of bodily meaning brings Dido and Aeneas very close to Judith Butler's theory of gender performativity.Footnote 5 As Foster observes, “Butler's notion of performativity, not unlike choreography, emphasizes the structuring of deep and enduring cultural values through the implementation of specific representational codes and conventions” (Foster Reference Foster2002, 137). However, Foster also critiques Butler for drawing her theory of performativity from linguistics—specifically, from J. L. Austin's taxonomy of performative utterance—rather than from actual performances (Foster Reference Foster1998, 3–4). Although Foster recognizes that Michel de Certeau brings Austin's linguistically based theories into the realm of bodily meaning, so that “swerves” and other errant gestures can disrupt social codes of normativity, de Certeau is concerned with a meandering assemblage of pedestrian movements. He proposes that quotidian movements can present a tactical challenge to the strategic order of urban systems; he gives even the act of walking the capacity to create multiple levels of meaning. For de Certeau, the moving body produces speech-acts that can appropriate elements of language, delineate a relationship with an interlocutor, and even “transform each spatial signifier into something else” (de Certeau Reference de Certeau and Randal1984, 98).

Succinctly describing de Certeau's extension of Austin's theories as “speech-equals-act,” Foster finds that, whether on the streets or onstage, moving bodies “all operate within the fields of a language-like system; individual bodies vitalize that system through their own implementation of it” (2002, 129). “By endowing bodily action with enunciatory intelligence,” Foster writes, de Certeau's theories of signifying, tactical movement allow the dance scholar to analyze dances ranging from contact improvisation to Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane's early duets (Reference Foster2002, 130). While Foster embraces de Certeau, she sees Butler as intractably distant from dance studies, stating that Butler “provides no framework for the analysis of bodily movement” (Reference Foster2002, 138).

Taken together, though, Butler's theory of gender performativity and Foster's dance-oriented framework for de Certeau's interest in bodily speech-acts can be useful in analyzing the interlocking aspects of kinetic and spoken language in Dido and Aeneas. When Foster envisions the potential for meaningful kinetic utterance in dance—“bodily motion as articulation,” as she puts it—she opens up the possibility of analyzing the danced language of corporeal speech-acts (Reference Foster2002, 131). In fact, her conception of “movement as a series of discrete lexical units” takes on a new meaning in light of Dido and Aeneas, and even invites us to return to Austin as we seek to understand the nature, force, and limits of these bodily utterances (Foster Reference Foster2002, 139). Dido and Aeneas, with its “here, here” and its pantomimic overload of gesture, works hard to bring us into the realm of discrete lexical units. In bridging the distance between dance and language though indexical and pantomimic gestures, Dido imagines a choreographic reality in which a performed bodily utterance is a performative speech-act—by saying, I do; and, in doing, I say. Austin and Butler show us how linguistic signifiers can be understood as acts; de Certeau and Foster show us how actions can speak, write, and possibly transform the language in which they operate. Dido and Aeneas, swerving in its own tactical way between movement and language, does both, and therefore requires the methodological amalgamation of these theories by re-aligning Austin's framework with the ways in which dance can signify.

Because Dido establishes onstage gender identities through repeated, stylized gestures, it illustrates Butlerian performativity. This performativity, however, does not become lodged in discrete corporeal units—in the individual bodies of danced characters—but is instead distributed variously over the diverse bodies of the company's dancers during the course of the performance. Morris's choreography of gender expression presents masculinity and femininity as a set of behaviors, postures, and gestures that play across male and female bodies alike. Not only does Morris appropriate conventional elements of gendered movement, heighten and stylize them, and use them to convey meaning in his narrative dance, but he also asks his dancers to perform gestural speech-acts that are arbitrary—and possibly transformative—with regard to their own identities as speakers.

As Ramsay Burt writes, “In Austin's terms, one could say that Morris's performance of femininity was not used seriously, but in ways parasitic upon its normal use” (Burt Reference Burt2006, 40).Footnote 6 Burt's adaptation of performativity to a reading of Dido and Aeneas is also Austinian in that it sees Morris as staging failed or “infelicitous” speech-acts—an approach that makes room for “parasitic” acts of theatrical gender performance. With an amplified understanding of the ways in which Austin's theories can describe the signifying potential of moving bodies, we can analyze danced utterances as performative speech-acts without losing the dimension of actual, staged performance. Restoring attention to the specific quality of movements allows us to realize the potential of Butler's theories when applied to dances that overlay signifying codes of language, bodily codes of movement, and affective codes of gender on and through the concept of performance.

In Dido and Aeneas, gestures can be deictic and mimetic, and they do refer to identities whose depth is apparent in their ironic resonances; this is why we are able to learn, first, that Acteon is a hunter through the repeated movement of an arrow being notched on a bowstring and, later, that this identity is fatally reversible. Not only is Dido and Aeneas a rare sort of dance in that it cleaves to the indexical model of verbal language, it is also a danced investigation of how identities are inscribed on bodies. If this inscription were a straightforward process—if gestures in this dance always indicated the identities of the bodies dancing them—Morris would merely have created a kind of musical pantomime. The Queen would make noble, feminine, queenly gestures, and the Sorceress would make witchy, hag-like, cackling gestures; the heroes would stride with bold manliness towards their destinies, and the sailors would strut around, jauntily hoisting the sails. Indexical and pantomimic gestures establishing each character's identity would accord with the gestural speech-acts undertaken by each character in order to accomplish stage actions.

But Dido and Aeneas is a drag dance. There is an overt contradiction between the speech-act and the body of the speaker. In other words, Dido and Aeneas possesses a vocabulary of overt signifiers that communicate gender affect, but sets this language starkly at odds with the gender of the body most often onstage performing it. As Butler writes: “In imitating gender, drag implicitly reveals the imitative structure of gender itself—as well as its contingency” (Butler Reference Butler, Salih and Butler2004, 112). Dance heightens drag's potential for revelation by making the performance and the identity occur in the same place: the moving body. Morris multiplies this potential by making a dance like a language that can be spoken by the body, and then speaking that language “badly” by not articulating a legible, stable gender identity. He takes drag from the surface of the body (what drag looks like) and embeds it deeply in the kinetic experience of dance (what the drag body can do).

In this ballet, the two lead roles are female, but both are danced by a man; that man is the choreographer, but he is also the dancer who must perform, sweatily, the movements dictated to him by the choreographer. Since this male dancing body is Morris's own, he collapses one of Foster's objections: that dance as a discipline enshrines male authorities over female dancers, just as Butler privileges spoken words over embodied movements (Foster Reference Foster1998, 17). The material of Dido and Aeneas is gestural speech-acts, and the structure that governs it is one of tactical transposition—the inappropriate transference of signifying gestures to bodies that should not, according to cultural gender conventions, be able to speak them. Morris exaggerates the legibility of mimetic gestures only to show that even the most tightly bound relationships between a physical signifier and its bodily referent leave room for misreadings. At best, misreadings of gender can turn out to be a vulgar joke—a man acting out a charade of female masturbation as Morris does in the fourth scene has no need to wipe his finger off afterwards—but at worst they represent a dangerous illiteracy, a failure to see that normative gender behavior is a set of codes inscribed on bodies.

I propose that Morris is using his dancing as a speech-act that brashly miscommunicates and illicitly transposes gendered meaning: Dido is full of bad language. It is in this double sense, as Burt indicates, that Morris's performance is “parasitic” on both linguistic and gendered meanings. Gay Morris corroborates this idea, by citing Mark Morris's choreography as the text that “will show that dance [which can incorporate drag] offers far more subtle and wide-ranging possibilities for attacking rigid gender categories than does drag alone” (G. Morris Reference Morris and Morris1996, 142). Following de Certeau's idea of errant movements that leave visible and disruptive traces, we can see this dance as a form of “bodily writing” that scrawls both feminine and effeminate phrases across a male body. It is not Morris's costume that makes the piece a drag dance; it is the way he uses his gestures to invoke these physical expressions of femininity against and—at the same time—through his male body. As David Gere wrote in a discussion of Joe Goode's 29 Effeminate Gestures, “The effeminate man does not ‘cross-dress’ but rather ‘cross-gestures’” (Reference Gere and Desmond2001, 375–6).Footnote 7

Jane C. Desmond has argued that, at the intersection of dance and gender studies, scholars must analyze movement-based performances specifically. “As cultural critics,” Desmond urges, “we must become movement literate.… We should not ignore the ways in which dance signals and enacts social identities in all their continually changing configurations” (Reference Desmond1993–94, 57–8). Since this concern aligns with Foster's critique of Butler—“she never examines the eclectic movement vocabularies” and so draws conclusions about identities “without actually detailing the ranges of exaggerative and ironic gestures”—it is crucial to look at the kinetic language of the piece, paying special attention to its “parasitic” uses of that language (Foster Reference Foster2002, 137).

The Wicked Choreographer

Originally, Morris had conceived Dido and Aeneas as a ballet in which he would dance all of the parts himself, but eventually he made ensemble dances for the full company (Acocella Reference Acocella1993, 110). The lead role of Aeneas went to Guillermo Resto, and Morris kept the two principal roles for himself: one was Dido, Queen of Carthage, and the other was the maleficent Sorceress who orchestrates Dido's tragic fate. That both of the lead female roles were cross-gender cast outraged the conservative Belgian press when the piece premiered in 1989. “Mark Morris, Go Home!” was the headline splashed across the Brussels' main newspaper, Le Soir (O'Mahoney Reference O'Mahoney2004). “Obviously, Morris's choreographic inspiration is to be found up his butt—which is not worth going far to see,” was the sarcastic summing-up that appeared in Le Drapeau Rouge, another Belgian paper (Roy Reference Roy2008). Because the costumes for all male and female dancers in the piece were the same—simple, long, black, sleeveless tunic-dresses that fell to mid-calf, which referenced the chitons worn by both genders in ancient Greece—and because the whole cast wore red lipstick and small gold hoop earrings and fingernail polish, it could not exactly be said that the costumes were drag (see Photo 2).Footnote 8

Photo 2. Mark Morris and Guillermo Resto in Dido and Aeneas. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann/MMDG.

The undeniable drag elements of Dido and Aeneas come specifically from Morris's distinctive way of utilizing his own almost monumentally masculine body to portray these two female characters. As Dido, Morris is anguished and queenly, while deliberately evoking a feminine use of the body. To the phrase “press'd with torment,” in Dido's first aria, Morris places one hand flat on his chest, one hand flat on his stomach, with the fingertips pointing downward, and then—maintaining the tension of the gesture by tightly pressing his fingers together—slides both hands down his body towards his pelvis, while slowly opening his legs. When Dido is watching her court dance its communal reassurance that Aeneas will return her love, she gets girlishly carried away by it all—the quick bright music, the joyous dancing, and the confirmation of her feelings—and begins to shift her torso coyly from side to side, caught up in the rhythms of the dancers' enthusiasm.

As the Sorceress, Morris seizes on the phrase “conjure up a storm” and conveys it by shimmying vigorously. He tosses his long curls with a flick of his wrist, taps his witchy fingernails in bored little trills, makes faces when his coven goes too far, rolls his eyes dramatically for emphasis, and generally “lounges about in parodies of femme fatale poses,” as Gay Morris puts it (Reference Morris and Morris1996, 148). Femininity, for the Sorceress, is a performance of high camp. Moreover, the choreography for her role includes a scene in which she lies prone, downstage center, walks her fingers of one hand down her body to her crotch, caresses her breast with the other hand, closes her eyes and opens her mouth, shudders, arches her back, and unmistakably mimes female masturbation to orgasm.Footnote 9 After she comes, the Sorceress wipes her finger clean on her dress; she is showing the extreme, explicit extent to which she can act as a female body, in all its materiality. The Sorceress's masturbation scene is a limit-case of gender and movement, in which gesture becomes a language that visually contradicts the body producing it.

The Sorceress is the most zealous user of pantomimic gesture in the whole ballet, and she imparts her gestures to her coven.Footnote 10 When the Sorceress and her coven are gleefully envisioning the results of the plan to destroy Dido, they dance several repetitions of the lines, “Destruction's our delight/ Delight our greatest sorrow.” The first of these lines gets the Sorceress, who is downstage center, clapping like she's at a hoedown, and then on the word “sorrow,” she makes a big “boo-hoo” gesture by pretending to rub her fists in her eyes, with her lower lip stuck out in a pout. It's a five-year-old's idea of conveying a grown-up word like “sorrow.” Acocella says wryly that “the literalness of the translation varies from dance to dance in Morris's repertory,” but that sometimes, “ the narrative method is very close to that of ‘I'm a Little Teapot’” (Reference Acocella1993, 142).

In the “Delight our greatest sorrow” scene, the Sorceress takes great satisfaction in making gestures to the lines “Elissa bleeds tonight” and “Elissa dies tonight.” (“Elissa” is another name for Dido.) The acting out of Dido's imminent death is done, first by the Sorceress and subsequently by her whole twitchy coven, by making two similar gestures. The line “Elissa bleeds tonight” is taken up by a two-handed gesture in which the Sorceress stabs an imaginary dagger into each of two witches' bellies, then slices their bodies open to the throat in three shuddering movements. With each motion, the two witches mime their death agonies, their eyes rolling back and their mouths open; then they collapse to the ground. To the line “Elissa dies tonight,” the Sorceress gestures as if gutting herself with one decisive, quick, ripping motion. It is graphic, and it is accompanied by the coven's interpretative demonstration of other death-gestures, which range from shooting themselves in the head to slitting each other's throats. It is during this scene, watching the violent antics of her coven, that the Sorceress masturbates.

This scene occupies an interesting place in the structure of the ballet: it shows the Sorceress acting as a choreographer, creating and directing the narrative of the piece, “setting” movement phrases on her company of witches. Following a real-world model of dance-making, the Sorceress generates movements on her own body and joins them together to make phrases; then the dancers pick up the movement sequences through imitation, and everyone rehearses this “wild vaudeville” together (Khadarina Reference Khadarina2008). In the “rehearsal” period, there is even some improvisation, in which the coven dancers create related movements based on what they have learned already from their choreographer. In the final stages, the choreographer has the pleasure of sitting off to one side, watching the company perform his or her new dance; this is, more or less, what the Sorceress does when she masturbates. The fact that Morris is both the choreographer of Dido and Aeneas and the Sorceress who “choreographs” this scene makes it a self-ironizing joke about what choreographers are doing when they make dances.

The Sorceress, however, is not just choreographing these movements for her witches to rehearse in private. She has created this scene to be performed by Dido—the one person who can't be onstage learning movement phrases from the Sorceress, since they share the same body. This configuration is familiar in dance history because of the casting for Odette/Odile in Swan Lake. There is an Odette/Odile paradigm in Dido, too—the principle female role is an embodiment of the split self: one part flashy and wicked and dark, and the other part noble and loving and self-sacrificing—but because Morris is also the piece's choreographer, and doing both roles in drag, his performance accrues a knowing irony. In Alastair Macaulay's opinion, Dido is “a stroke of imagination yet more radical and revelatory than Matthew Bourne's, in Swan Lake, in casting a male Swan/Stranger in lieu of both Odette and Odile” (Macaulay Reference Macaulay2000, 816).

That the Sorceress is both the “drag role” of the ballet, as Gay Morris says, and the choreographer of its essential narrative action (Dido's suicide, which ends the piece) shows how Morris is using casting in Dido and Aeneas to make a point about the way in which gestures are transposed from body to body, and can even be enacted by bodies that should find them impossible or, at least, unseemly. The kinetic language of the ballet—its whole gestural vocabulary—works tremendously hard to communicate how each character relates to the words of the libretto, and the Sorceress's choreographic pedagogy is the index of its success. Using gestures that could convey meaning both to a naïve audience (the “boo-hoo” gesture means she's crying) and to sophisticated readers of gender dynamics in dance (Morris, a queer choreographer, is ironizing the egotistical pleasure of the choreographer through camp gesture), the Sorceress amplifies and reinforces her speech-act by having her coven perform it again and again. She re-enforces the collective literacy of the audience. It is exactly because the piece's language is so dedicated to mimetic communication that Morris has the freedom to unsettle far less literal bodily meanings.

And this is what Morris does with his own body in Dido and Aeneas: he uses it to proclaim its hyperbolic opposite, so that he is not merely a man dancing a woman's role, but a male body having a female orgasm. Once Morris has made sure that the whole audience is reading the mimetic gestures of his choreography, he turns these signifiers into the very antitheses of the referents he has so patiently taught them to grasp. Drag, in this ballet, is a liberation of gestures from the bodies that originate them, and a broader critique of the practice of conflating gendered signifiers with gendered bodies. By hyper-literalizing so many bodily signifiers (of which one is gender affect), Morris shows them up as a series of codes—a system of signs. These signifiers are part of a language, so they can break down in the same ways Austin (Reference Austin, Urmson and Sbisà1962, 18) finds language falling apart: there are bodily misinvocations, misexecutions, hitches, hollow acts, abuses, and insincerities. Drag is the primary mode of destabilizing the literalness of bodily signifiers in Dido and Aeneas. Combined with the doubled female roles Morris dances, it confers the freedom to transpose even the most narratively central identities from body to body. With the addition of the meta-narrative level of Morris as the choreographer who creates a language only to undermine it with his own performance, Dido becomes an experiment in how badly—with what degree of “infelicity,” Austin would say—gender can be articulated by a single dancing body.

Dido and Aeneas and Dance History

To convey this dynamic of a body whose proclaimed identity is belied by its movements, Morris draws on the gestural (onstage) history of twentieth-century modern dance, and on the legendary (offstage) sexualities of its protagonists. He combines elements of these bodily histories to create a code that underlies the more broadly legible kinetic language of Dido and Aeneas. Unlike the ballet's vocabulary as a whole, these specific citations are only meant for one segment of the audience—those used to reading dance for its queer content, who would conceive of twentieth-century dance history as a strand of queer history; in other words, those who already think that dance history is full of queens.Footnote 11

“Mark Morris … is the greatest modern-dance creator of dramatic female roles since Martha Graham,” Alastair Macaulay declared in Reference Macaulay1989 (25). It was no accident that Macaulay compared Morris to the woman who revolutionized modern dance by choreographing dramatic, intensely female roles (and who, for as long as she could, always danced the ardent, iconoclastic lead herself). Dido and Aeneas makes a clear allusion to the bench Martha Graham used in her famous solo, Lamentation; the only real prop in Morris's ballet is a low bench. As Dido performs the “press'd with torment” gesture while seated on this bench, she opens her legs and the audience sees the fabric of her dress stretch taut over her bent knees, as well as the strong flexed position of both feet: it is a clear citation of Graham's movement vocabulary in Lamentation. There are also echoes of Graham's penchant for the female protagonists of Attic drama, since she chose to create roles for herself based on several queens from Greek tragedies. These included the roles of Jocasta and Phaedra who, like Dido, commit suicide when faced with the knowledge of their sexual shame.

Acocella, who doesn't characterize Morris's Dido as a drag role, proposes that his “big male body gives the quality of monumentality that is so essential to her pathos” (Reference Acocella1993, 101). She argues that, because Morris doesn't attempt to perfect an assimilation of femininity when he plays Dido, “the violation of sexual identity depersonalizes the portrait, just as masks presumably did in Attic tragedy” (Acocella Reference Acocella1993, 101). It is true that Morris draws himself up to a full and imperious height when he dances the role, and he uses the squared bulk of his shoulders to mark off an untouchable space—a royal presence. The imposing effect of Morris's size and masculine body is felt most fully at the moment Dido confronts Aeneas, ablaze in a righteous rage at the knowledge that Aeneas has chosen to leave her and set sail for Italy. As the line “For ’tis enough, whatever you now decree/ That you had once a thought of leaving me,” is sung, Dido towers over Aeneas, menacing him with her sheer physical mass.

However, the effect of producing Dido's queenliness through Morris’ decidedly masculine body is not exactly one of “depersonalization.” Rather than striving for androgyny or a mask-like neutrality—as Graham did in Lamentation—Morris cultivates a state of intensified contradiction, constantly reminding the audience that he is a man dancing the role of a woman. The hieratic movements of his Dido are imbued with dignity, but they invoke explicitly sexual gestures that are either feminized, effeminate, or both.

The most obvious of Morris's references is to Vaslav Nijinsky's L'Après midi d'un faune; Bronislava Nijinska described how Nijinsky insisted on a “bas-relief form” in which dancers would “align their bodies so as to keep their feet, arms, hips, shoulders, and heads in the same choreographic form inspired by archaic Greece” (Nijinska Reference Nijinska, Nijinksa and Rawlinson1981, 405). Nijinsky choreographed Faune so that the dancers' bodies were always posed in two-dimensional space, moving in flattened and angular lines that imparted a sense of anachronistic, almost hieroglyphic poses. Thea Singer of The Boston Globe describes Dido and Aeneas in exactly the same terms, praising the ways that the piece “takes the tragedy and sculpts it—with angular friezes and two-dimensional posturing, hieroglyph arms and symbolic gesturing” (2008). Dido's hieratic movements claim a direct heritage in Nijinsky's Greek-inspired piece. On the surface, this citation reads as archaic, noble, and classicizing, but for those who are attuned to the connotations, it also links Dido's sexuality to that of Nijinsky's notorious Faun.

Faune ended with an infamous gesture: the Faun masturbates into a scarf abandoned by a fleeing nymph. The day after the premiere, the newspaper Le Figaro published a front-page polemic, decrying Nijinsky's “vile movements of erotic bestiality and gestures of heavy shamelessness”—an accusation very like those leveled at Morris for the masturbation scene in Dido (Nijinska Reference Nijinska, Nijinksa and Rawlinson1981, 436). Nijinsky, who did not make his sexual interest in men public knowledge, did nevertheless choreograph ballets with explicitly sexual, “deviant” premises—besides Faune, there were the implications of homoeroticism in Jeux—and Lynn Garafola characterizes these two ballets as part of Nijinsky's “erotic autobiography” (Garafola Reference Garafola1989, 57). Mark Morris, who describes himself as “a queer artist” (Rule Reference Rule2009), made Dido during his confrontational years in Brussels—a place he perceived as tolerating homosexuals only “if you wear a suit and have a firm handshake and don't give any trouble … I'm not like that” (Montgomery Reference Montgomery1989). Morris's alluding to Faune's hieratic movement vocabulary and notorious masturbation scene demonstrates, as Gay Morris writes, that Nijinsky's “ghost hovers over Dido and Aeneas” (Morris Reference Morris and Morris1996, 148). Both ballets were choreographed and danced by queer men who used the same device: the masturbation scenes were mimed as if the bodies were not those of men (one was a hybrid creature and the other was a witch). In other words, the sexual act was explicit, but it was also displaced, and the movement vocabulary of poses held in profile only served to frame and heighten this effect. The pantomimic sexual gesture was in direct contradiction with the “nature” of the body performing it.

Besides using hieratic movements that directly referenced classical cultures, Morris was developing the character of the tragic queen within the context of American dance history's perspective on Greek culture. (Originally, of course, Dido was not Greek but Carthaginian, and her story is told in Latin, in Virgil's Aeneid; but Aeneas was a Trojan hero in Homer's Greek epic The Iliad before Virgil adopted him.) Martha Graham's melodramatic Greek phase, with its shocking sexual narratives, is one part of Morris' inheritance. Choreographic inspiration based on Greek aesthetics also recalls Isadora Duncan, who used the justification of a return to classical ideals as a response to the scandal provoked by her free, feminine, gauzily uncorseted style of dancing. These two female choreographers, along with Ruth St. Denis, form the canonical triumvirate to which the creation of American modern dance is often attributed.Footnote 12

However, Morris's Dido and Aeneas doesn't make direct references to Ruth St. Denis (although Morris's debut solo, O Rangasayee, set to an Indian raga, clearly took up St. Denis's fascination with “Oriental” sources for her dances).Footnote 13 The concept of making a “Greek” dance with two male leads and a sculptural aesthetic suggests not Ruth St. Denis but her partner, Ted Shawn, the first significant American male choreographer in modern dance, whose closeted sexuality strongly inflected his vigorously masculine works. As Julia L. Foulkes notes, Shawn's 1923 piece Death of Adonis “drew on Greek ideals,” which is to say that Shawn “powdered his body white, and wore only a fig leaf G-string. The work consisted mostly of poses, flowing from one into another, and his idea was to convey a fluid sculpture” (Reference Foulkes and Desmond2001, 127). Shawn's asserted faithfulness to Greek aesthetics gave these sculptural poses a defensible classical pedigree, but this only barely covered up their queer implications. Susan Manning called this “the blatant double-coding of Ted Shawn's choreography”—a contradiction that conveyed how visibly queer his dances were, for an audience attuned to the significance of that gestural vocabulary (Reference Manning and André2004, 92). Thus, the first important American male modern-dance choreographer was marked as homosexual, and his sexuality was linked to the idea of male bodies (especially his own) performing Greek-identified dances. Foulkes reinforces this idea by stating, “Homosexual desire … was probably always present in this Greek model of male nudity … [and] dance, in particular, allowed for a greater suggestion of homoeroticism than literature” (Foulkes Reference Foulkes and Desmond2001, 127). The costumes for Dido and Aeneas are fairly modest, but the association with male-focused “Greek” dance and sculptural poses ties the piece strongly to Ted Shawn's legacy.

Like Shawn, Morris alludes onstage to his own sexual identity by exaggerating the codes of gender performance. Whereas Shawn was suspiciously emphatic about the heterosexual manliness of his choreography and his dancers, Morris made Dido and Aeneas a shining example of his artistic capacity to dance two opposing female lead roles. As Acocella attests, “The most monumental role that Mark Morris ever created was the double role of Dido and her sworn foe, the Sorceress” (Acocella Reference Acocella2006). As the Sorceress, Morris exaggerates the stereotypes of effeminacy; as the Queen Dido, Morris expresses a deeper, more womanly set of emotions, making use of the tropes of feminine movement. Between the Sorceress's hyperbolic camp effeminacy and Dido's insistence on the bodily nature of her sorrow—epitomized by the spread-legged “press'd with torment” gesture—the ballet overloads the gestural codes of gender affect.

Morris didn't stop with just one cross-cast sex scene in Dido, and he didn't confine his graphic choreography to the Sorceress. At the center of the ballet, a brief, wordless, heterosexual coupling occurs: Dido lies down on her back on the floor and opens her arms to Aeneas, who lies down on top of her. Eleven seconds later, he is standing upright again, staring off into the distance, contemplating his heroic destiny. It's one of the more naturalistic movement phrases in the piece, but it's not a very flattering view of heterosexual love. Performing one of the least “dancey” moments in Dido and Aeneas, Morris and Resto make straight sex look brief and pedestrian, almost unaestheticized.

This scene establishes—at the exact center and narrative fulcrum of the ballet—a glaring contradiction between a gendered gesture and the gendered body performing it. Dido, a dramatic Greek queen in the mode of Martha Graham, moving in the hieratic lines of Nijinsky's Faun, lies down on the floor to mime a declaration of her sexuality; and she does something very like what Ted Shawn did, which was to contradict his queer male body by making an unmistakable gesture of heterosexuality (besides creating hypermasculine dances, Shawn married Ruth St. Denis). However, with this scene, Morris also does something quite serious with the offstage queer history of twentieth-century dance: he puts it right into the middle of his ballet. He lies down center-stage and performs its maneuvers of self-contradiction—its private secrets, its public performances—right there on his own body, acted out in the clearest and most overt gestures. With that, he takes the invisible writing of a century of queer dance history and re-inscribes it as visible, tangible, and legible.Footnote 14

Taken together, the many sexualized and gendered gestures made by Morris in his two lead roles disqualify his performance from the category of “depersonalization.” Instead, Morris deliberately undertakes to heighten all the contradictions between his male body and the various feminine or effeminate gestures that can be performed upon it.Footnote 15 Furthermore, he infuses Dido with his personal offstage identity; the declaration that he is queer is obviously widely understood (otherwise the critic of the Drapeau Rouge would not have proposed sardonically that Morris' inspiration is to be found “up his butt”). Morris populates his ballet with the ghosts of other queer icons of twentieth-century dance, citing their gestures like palimpsests of a history of dance that he both chronicles and inherits. The fact that he draws upon a queer dance history as part of his physical lexicon is the opposite of “depersonalization”: this is an unmasking and a decoding. Morris makes it part of his project as a choreographer to historicize particular personalities, and to convert their private sexual identities into a public performance. As Dido and Aeneas enforces the legibility of gestures, it pushes the legibility of queerness, too, creating an intensified contradiction in which the “unspeakable” is communicated in clear kinetic language.

Half Queen, Half Queer

If there were a character from Greek myth that could illuminate Morris' conception of Queen Dido, it might be Pentheus, the protagonist of Euripides' tragic drama, The Bacchae.Footnote 16 Pentheus, a prince of Thebes who is overcome by Dionysian madness, spends a significant amount of the play cross-dressed, toying with his wig of girlish curls and admiring his pretty dress. Dido's most interesting relation to Pentheus is the way that Morris changes costume between the role of Dido and that of the Sorceress. In fact, he doesn't change his costume at all, except in one small respect: he pulls out the hairclip which has been holding back Dido's hair, and the long, curly locks of the Sorceress twine down around his shoulders.Footnote 17 In the Bacchae, the moment that Pentheus cross-dresses is the moment that he splits from himself—he sees double suns in the sky, and Dionysus arranges the prince's long hair to resemble his own exotically feminine curls. The echo in Dido is that the queen, like Pentheus, embodies an internal split: she loosens her curls and becomes her opposite, the Sorceress.

If we step back for a moment from seeing Dido as a classical character, and think of her categorically as a queen, we are reminded that her double or split body has a historical antecedent. In fact, the problem of correlating the power of monarchy with the body of a woman inheres in the concept of queenliness. The idea that the queen's royal body is publicly male (unemotional, rational, aggressive) and privately female (physically weak, sexually feminine, subject to variable emotions) underlies Dido's character. In Book IV of the Aeneid, Virgil emphasizes pointedly that the Queen's love for Aeneas has caused her to turn her attention away from the prosperous, industrious civic life of Carthage, absorbed instead in the idle luxuries of romance.Footnote 18 The implication is that Dido, as a queen, is inherently split between a robust, imperial, masculine body and a love-struck, idle, intimately feminine one. Morris reverses the performance—instead of being privately female and publicly male, he spends his offstage life as a man, and acts as a woman in the theater—but he maintains the concept of Dido as a queen who inhabits both a masculine and a feminine body, and whose body is thus double-coded in terms of gender.

When Dido and Aeneas premiered, there was another direct link to the character of the queen, but it wasn't a very noble one. Acocella records several anecdotes that illustrate Morris's interactions with Queen Fabiola of Belgium, royal patron of the Théâtre de la Monnaie. When she attended a performance of one of his ballets during his first season in Brussels, the Belgian audience called out, “Vive la reine!” With mock innocence, Morris commented to a journalist that he had supposed the shouts were for him (Acocella Reference Acocella1993, 6). What was worse, when he was granted an audience with Queen Fabiola after the show, he summarized it afterwards by remarking nonchalantly, “Best blow job I ever had” (Acocella Reference Acocella1993, 86). There was a reporter at his elbow when he said it.

This very camp version of queenliness—the outrageous, trashy, overtly sexual, larger-than-life performance of feminine power—featured Morris's somewhat tactless impulses to be fabulous against the atmosphere of conservative gentility surrounding Queen Fabiola. With his offstage behavior, his insistent performance of outré queerness, he was making a joke about what Dido was not: a drag queen. The character in the ballet who did, in fact, closely resemble a drag queen was Dido's opposite—the campy, theatrical, vulgar, entertainingly wicked Sorceress. As Esther Newton attests, there is an “overwhelming emphasis upon the queen” in camp contexts generally, so Queen Dido and the Sorceress-as-drag-queen neatly interlocked as characters (Newton Reference Newton and Lewin1996, 173). Gay Morris argues that although “. . . Morris' performance as Dido does not conform to Judith Butler's definition of drag, his Sorceress does. She is the epitome of hyperbole” (Morris Reference Morris and Morris1996, 148). By exaggerating what femininity looks like, the Sorceress takes the performance of gender to its breaking point, and she does so by burdening gestural language with an excess of meanings. Hyperbolically, Morris exploits what Austin would call “misapplications” of utterance (Austin Reference Austin, Urmson and Sbisà1962, 34–35), which occur when “the ‘performer’ is of the wrong kind or type.” By declaring himself the Queen, Morris deliberately confuses the proper reference with its queer “parasitical” meaning. When Morris combines this with the assertion that he has been enjoying sexual favors from Queen Fabiola, he outrageously inverts the order of gender and sexuality; he is a performer of the “wrong kind” in a heteronormative framework.Footnote 19

For Morris to dance in drag as Dido was tantamount to an onstage declaration that he was queer; for him to dance the Sorceress was a way of saying, not just queer, but camp, too.Footnote 20 “He was an eighties personality,” Acocella wrote, “ironic, outrageous, heavy into ‘styles.’” (Acocella Reference Acocella2001). Camp enacts an effect of knowingness, but also an effect of ironic distancing. It is a gesture, like a wink, which affectionately lets you know that there is a joke being made: a gesture that points toward the artifice of other gestures. In addition to being campy, the gestural vocabulary of the Sorceress was often more acted than danced—there were more facial expressions, for one thing, like the slow cruel smile she gave when devising the means of Dido's doom.

In Dido, therefore, Morris imported not only backstage knowledge into the narrative of the piece, but offstage knowledge as well: the dancer is a man, the man is queer, the queer man is the choreographer who is making off-color jokes about the Queen of Belgium. The choreographer becomes a supernatural creature, like the Sorceress, who can move between worlds by shape-shifting—onstage, he becomes a queen, then a witch, then a queen again. The double-drag casting of Queen and Sorceress is played off the “double” casting of Sorceress/choreographer, and off the antagonistic “double” appearance of two Queens in the lobby of the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels, in the postmodern late 1980s where, as Mark Morris pointed out, when the crowd shouts Vive la reine!, its referent is actually subject to interpretation.

To Be in the Dance

“In the earliest days,” Mark Morris said reflectively in an interview in 2005, “when certain things needed to be said in public that are now old hat like queerness and feminism, I wouldn't choreograph anything that couldn't be done equally well by men or women. If I want a big number with everybody in it, you don't get to decide which sex you get to be, you just get to be in the dance” (Carman, Sucato, and Perron Reference Carman, Sucato and Perron2005). Acocella has emphasized how thoroughly Morris's choreography is a product of his early training in Balkan folk dance; how “the democratic look of his dances” emerged from the collectivism and geometric patterning of this folk tradition, which in time “made his company too look like a village” (Acocella Reference Acocella1995, 22).Footnote 21 The ensemble dances in Dido and Aeneas reflect the values of these Balkan folk dances, being both gender-neutral and touchingly communal.

The influence of folk-dancing is most strongly apparent in a scene called “The Ships,” in which Aeneas gives the order for the Trojan ships to be made ready to sail, and his sailors—the same dancers who perform in Dido's court and in the Sorceress' coven—exuberantly set about hauling in ropes, hoisting up sails, and taking “a boozy short leave/of your nymphs on the shore.” To do this, they hike up the skirts of their costumes just above the knees, and tuck them in so that they are wearing something like short, loose, blousy trousers. It's an even more unisex look than the long tunics they wear in the other scenes. The sailors' gaillarde includes elements of Irish step-dancing (the arms held straight at the sides, quick light kick-steps with the knees kept together), general folk-dance formations like the two lines of dancers who face each other, and, in keeping with the rest of Dido, a lot of gestures keyed precisely to words in the libretto. Among these are the pantomimic gesture of tossing back the rest of one's drink, to signify the “boozy short leave,” and a finger to the lips which wags back and forth to the line “and silence their mourning.” The sailors do look happy that they get to be in the dance; they clap on beat, they play tug-of-war with a rope, and at one point they put their thumbs in their armpits and flap their elbows like chicken-wings, which is an exceedingly goofy gesture, but one they do cheerfully.

Another salient aspect of the sailors' dance is that it is pointedly not virtuosic. That's partly what Morris meant when he described the gender dynamic among the early members of his company by saying, simply, “They can all do everything” (Acocella Reference Acocella1993, 91). Specifically, the Dido and Aeneas ensemble dances are remarkable for their “all do everything” spirit, even to the point of looking a little good-naturedly ragged around the edges. They are sometimes cast against gender and body-typeFootnote 22 (although often not), which gives the impression that Morris has not even really noticed which of his dancers are male and which are female.Footnote 23 The dancers themselves see the way that communal, nongender-based casting inscribes itself in their bodies. Joe Bowie, a former company dancer, described this experience vividly: “Before dancing with Mark, I spent two years dancing with Paul Taylor … I was always squatting and jumping, always picking people up, because with Paul, men are men and women are women. But after a few months with Mark, I noticed I could wear jeans again. My thighs were no longer too big…. Oh. And I finally had a neck” (Senior Reference Senior2002).

At the end of the sailors' dance—after the very last boozy leave has been taken from the nymphs on the shore—two dancers remain onstage. One is a man and the other is woman, and the man throws the woman over his shoulder like a sack of potatoes and saunters offstage. It's one of the very few lifts in the entire ballet, and, since in the history of the species, men are both the ones lifting women in dances and the ones known for throwing women over their shoulders and carrying them off, it seems that this interaction should signal something about the gender relations between these two dancers. It completely refuses to do this, and instead gives exactly the opposite impression—they're both sailors, and if one of them is too drunk to walk, the other one will pick her up and helpfully carry his shipmate back to her berth to sleep it off. Even this trivial moment, the movement phrase for the last dancers' exit is choreographed to exude communal, gender-neutral goodwill.

There are two other notable lifts in Dido and Aeneas. One happens during Dido and Aeneas' duet; this is the citation from The Sound of Music, which includes Dido running up on a bench while holding Aeneas' hand. The lifts in this scene are possible only because Dido whirls the mass of her body around, and the momentum this creates allows Aeneas to lift her briefly from the floor, in the midst of her turn. When Dido runs along the bench, Aeneas merely holds her hand; she jumps down to the floor by herself, and then he runs along the bench in the same way, while she politely holds his hand. The romance of the power imbalance between two gendered bodies—a dynamic that underlies all classical ballet, and is far from absent in modern dance—is subverted by two things in this scene. One is a citation of a popular musical (with a camp connotation in queer culture), and the other is the equality of movement Morris has taken on as a principle, following Balkan folk dancing. This duet is as close to a romantic pas de deux as Dido and Aeneas comes, but its main quality is that of inclusive equality.

The other significant lift in Dido and Aeneas is an unusual one, involving three people. When the Sorceress has planned Dido's ruin, she squats down slightly and holds out her arms to her two witchy minions—the same ones who have just been jumping up on each other's backs—and they hop right up onto her big thighs, one perched on each meaty leg, and she holds them there, looking back and forth between them with an evil half-smile, until the lights go down. One of the witches is female and the other is male, but their choreography is absolutely equal. In fact, in the subsequent scene with the Sorceress, the persistence of gender-blind casting comes to a perverse point: what arouses the Sorceress is a series of short charades, or mime sequences, in which various pairs of her witches act out Dido's death at Aeneas' hands. In the first charade, the witch acting as Dido is female and the one acting as Aeneas is male; they kiss, and then “Aeneas” slits “Dido's” throat with one savage gesture. In the second charade, “Dido” is male and “Aeneas” is female; they kiss, and then the hero slices the queen's throat open. Any witch may signal that he is “Dido” by making the “royal fair” gesture of sweeping his hand in a semi-circle across his profile, and any other witch may signal that she is “Aeneas” by holding her arms out in a strong, definite triangle that lays claim to a swath of air. While the Sorceress is masturbating, this has gotten to the point where entirely random pairs of witches are mashing into each other and then jerking apart, falling to the floor, scrambling up again, throwing their bodies together and then springing apart again.

It is not the gender of the witches' bodies that determines whether they are “Dido” or “Aeneas,” but rather the signifying gesture that temporarily defines their identities as either “royal fair” or “hero”—and, in fact, the more quickly they switch roles, the more the Sorceress seems to enjoy it. The essential and continuous action in this mise-en-abyme is the charade of violent gestures, which must be play-acted as explicitly as possible for the Sorceress's pleasure. It appears that the Sorceress can masturbate to any gender combination of her coven, as long as their gestures of killing and dying fulfill two requirements: first, they must be legible; second, they must be repeated. This high-speed reiteration of arbitrary codes of gender identity ends up looking like Butler's idea of drag, but in free-fall. It shows gender codes to be so contingent, and so based on imitation, that bodies can signify an identity in almost no time at all, just by making a mimetic gesture. That identity is almost immediately exploded: the body falls to the floor, and when it rebounds, it is ready to enact a different, but equally legible gender identity. In other words, the codes hold, while the bodies slip freely in and out of them.

The combination of a double female lead role in drag and gender-blind ensemble casting established a dynamic that lasted until 2006, when Morris decided to bring the piece back into repertoire, after he had stopped dancing both Dido and the Sorceress (at that point, he was forty-nine years old; his last performance in Dido had been in 2000). This brought up a new question: what statement would Dido and Aeneas ultimately make about the identity politics of gender and sexuality? Morris seems to have had some problems settling this question himself, because he first proposed splitting the roles apart. Acocella reported in The New Yorker, just before the Company opened its twenty-fifth anniversary season at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, that “the grand-legged Amber Darragh [Star Merkens] will be Dido; the maenadic Bradon McDonald, the Sorceress” (Acocella Reference Acocella2006). However, in the end Morris decided that the role would belong to a single dancer during each performance, and the casting would alternate from evening to evening between Star Merkens (female, lanky, broad-shouldered, with a head of fierce curls) and McDonald (male, lithe, muscular, in cat-eye makeup with long ringlets tumbling past his shoulders); see Photos 3 and 4.

Photo 3. Bradon McDonald and Craig Beisecker with Company in Dido and Aeneas. Photo by MMDG/Costas.

Photo 4. Amber Star Merkens (neé Darragh) and Craig Beisecker with Company in Dido and Aeneas. Photo by Stephanie Berger/MMDG.

This casting choice drew the performance away from the deliberate “drag” aspects of Morris' performance, and toward a balance of gender-neutrality like that already present in the ensemble dances. The ballet that had originally scandalized the Belgian press with its antigender-based casting now seemed to be unconcerned with gender altogether. This paralleled a development in theories of gender performance, which had gone from being stridently subversive in the late 1980s and early 1980s to being more broadly, fluidly open-minded. These were the years when, for example, the gay theater company Bloolips collaborated with the lesbian theater company Split Britches to stage their all-drag cross-cast version of Streetcar Named Desire at WOW in New York. By the mid-1990s, mainstream Hollywood actors such as Sean Penn and Heath Ledger could play queer characters onscreen, and even win Oscars for them. The change to gender normative casting in Dido and Aeneas reflected a movement away from a political demonstration of visibility—a dance that declared, “We're here, we're queer, get used to it”—toward a recognition that many American dance audiences in the twenty-first century were used to it, and saw gender identity and sexual preference as a more open-ended set of possibilities.Footnote 24

And what would Morris himself do, now that he wasn't onstage dancing both female leads? He has chosen to do two things, and both of these bespeak his roots in folk dance traditions. As The Boston Globe critic Thea Singer wrote in 2008, “In this production, both female leads have shrunk; they now fit neatly into the frame of the work as a whole. Morris has, as if casting a bas-relief in reverse, brought the chorus—10 members of the Mark Morris Dance Group—to the fore” (Singer Reference Singer2008). Meanwhile, Mark Morris is down in the orchestra pit, out of sight, conducting the musicians and singers who are performing the score live. In other words, the emphasis on individual lead roles has diminished, and in its place we see a privileging of the group—the chorus of voices, the company of dancers—whose intermingled patterns create a democratic harmony. This is the idea that the kinetic language of the ballet is now being used as a conversation between equal interlocutors—between the dancers themselves, who seem most at home in the ensemble dance for the sailors, and with the audience, which is expected to accept with equanimity that they may see either Star Merkens or McDonald in the female lead roles.

Morris, having made his provocative declaration that queerness should be visible in dance and that gestural codes of gender should be pushed past their limits, finally decided that it wasn't 1989 anymore. Drag casting now alternates freely with “straight” casting, and when Amber [Darragh] Star Merkens plays the Sorceress, she actually has to draw on a bit of reverse drag (she sits on the bench like a basketball player, slouching her knees apart, propping her elbows, hunching her sizeable shoulders down, pushing her jaw out sulkily) in order to capture the camp edge. This newly invented variant on the Sorceress as a “drag role” is necessary because Morris believes, cheerfully, that the world has changed since his confrontational debut, and that Star Merkens has access to a whole spectrum of gestural gender affects, including straight jock masculinity. In Dido and Aeneas, the afterlife of cross-gender casting is the happy, sloppy, slightly bewildering world of the sailors where, if everyone lends a hand, they all get to be in the dance.

Transpositions

In the old days, when Morris was still fiercely dancing both lead roles, he could calibrate the exact effect of his gestures, heightening the tension between his single body and its two female personae. It was a delicate triangulation, since he had to first establish a credibly queenly Dido in the first scene and then, without changing costume, communicate at the beginning of scene two that he had become her nemesis, the Sorceress. The first time the audience sees the Sorceress onstage, her face is hidden: she is lying face down over the middle of the bench, with her hair and hands dangling to the floor. Her shoulders are hunched, her curls are a riotous mass, and her wrists are twisted inwards so that her knuckles lie on the ground while her long gold fingernails curl up slightly. It's a creepy posture; it looks like she could wake up at any minute and slither off the bench towards the audience. She lies there for some time, though, draped over the bench with her wrists twisted backwards—long enough that the image impresses itself in everyone's mind—and then, in slow deliberate movements, she starts to knuckle-walk her way down the bench, rippling her long snaky fingers but still keeping her face hidden.

This movement phrase represents a puzzling choreographic choice because it means that—for a large portion of the audience not familiar with the opera, which differs from Virgil's text by including the Sorceress figure—Morris has very limited modes of conveying that he is now playing an entirely new character who is the opposite of the character he has been until now. Because only the back of his neck is exposed in this position, the audience can't see yet that the hairclip is gone. Moreover, he can't use any facial expressions—his only modes of signification are the way that he holds and maneuvers his body. That he successfully communicates this new persona demonstrates the power of gestural language in this piece to transmit valuable information, even when this information contradicts assumptions about the body performing it. At the beginning of the Sorceress's first scene, Morris looks like Dido to the audience, just as he looked like a man when he initially appeared onstage as the Queen: these moments produce an effect of peripeteia—that shock of recognition that occurs when a thing neatly and dramatically becomes its own opposite.

At the end of the piece, Dido's tragic suicide seems to demonstrate that the Sorceress has successfully transposed her brutal choreography; first from her own body to the bodies of her witches—who have improvised even more guttings and slittings and stabbings—and finally to the regal body of the Queen. Of course, because the first and final bodies are really the same body, which is also the body of the choreographer, the effort of all this movement-making and rehearsing and refining starts to seem pointedly ironic—a way of stacking frames of reference inside other frames. The Sorceress is Dido's choreographer, but they are also dancing each other; Morris is the Sorceress's choreographer, and yet he still has to dance the death that the Sorceress has made up for Dido. This conflation of identities is very different from the gender-neutral, “all do everything” carousings of the sailors because, instead of equalizing the roles, it creates a hierarchy of power imbalances that is constantly telescoping in upon itself and reversing the positions. It is a very dark view of the insidious inscription of language upon the body.

When Dido commits suicide, she does stab herself, just as the Sorceress's choreography has mandated. But it is a brief and modest little movement, a quick sad slip of the hand towards the abdomen, and then Dido collapses forward—she just falls, before anyone from her court can catch her, and her body is lying there draped over the bench, her long hair spilling onto the floor, the back of her pale neck exposed and vulnerable. Her shoulders are drawn in a little, and her arms are twisted at the wrists so that the backs of her hands rest on the floor, with her fingers curling slightly inwards like a sleeping child's might. Dido ends her life in the exact same position as the one in which the Sorceress appeared the first time she was seen onstage.

The transposition of this gesture, more than any other, encapsulates the way that Morris uses drag as a strategy in Dido and Aeneas. The signature pose of the Sorceress—the one he works so hard to imbue with her coiled, witchy spitefulness—is completely unmoored from its first frame of reference, made free from the signification that tied it to her essential malevolence. When the gesture reappears, it has been entirely redefined, and now stands as Dido's noble, self-sacrificing gesture of doomed pride. It is Dido's final, deeply symbolic gesture, and the position in which her body remains for the lengthy dénouement of the piece, while her court dances its sorrow and then exits the stage in a slow procession of stately mourning. Dido has sought to express the grave and mournful meaning of her life; at least she should have her own singular and sorrowful vocabulary with which to express it. And yet, as her body gives its last utterance, as she performs the movement that seals her identity as a tragic queen, she is overwritten by someone else's language. It might be said that she does not die in her own words.

This gesture, which is bearing so much meaning, and which communicates fundamental narrative information about the two characters that perform it, is irreconcilably split between them. Dido and the Sorceress say the most essential things about themselves by performing them, but they are opposites, and so the gesture resembles the linguistic phenomenon of antiphrasis; words of this kind are also called “auto-antonyms,” “antologies,” and “enantiodromes” (Eulenberg n.d.). By analogy, if the same word can be used to mean two antithetical things then, in the language of dance, one gesture or single still posture can be used by two different characters in antiphrastic self-contradiction. Morris sets up the Sorceress's first posture as an antiphrasis to Dido's final pose, so that one gesture (and his own single body) contains two opposite meanings; this disrupts the whole carefully constructed vocabulary of Dido and Aeneas. It is clear what the Sorceress means when she curls her fingernails and twists her wrists, but then, when Dido performs the same gesture, it communicates her hopeless and regal conviction—the sorrow of her final peace. The audience must be willing to accept the disjunction between what they had expected a body to mean and what it is actually expressing. They are witnessing the transposition of gesture across the boundaries of identity, and with it the irreconcilable split of the signifier between two contradictory referents. It is not an infelicitous speech-act, but rather a statement that points out what can be fundamentally infelicitous about the languages in which bodily identities are expressed.

There is also a musical element of Dido and Aeneas that epitomizes Morris's use of drag as a strategy. Dido's lament—her final dance, sorrowful and clear-eyed, with many repetitions of the “fate” gesture—is performed to a musical form called a chaconne or ciaccona, which in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was a form of danced song with notoriously suggestive connotations. It later evolved into a slow, stately musical form characterized by its triple meter and variations on a brief harmonic motif, often built around a repeated bass line (Silbiger Reference Silbiger and Hogwood2001). In noting that Henry Purcell had chosen to make Dido's lament this latter kind of chaconne, marked by a recurrent ground bass, Joseph Roach remarked that the persistent historical reputation of this form was that it was “not European, and that it drove women crazy” (Roach Reference Roach, Parker and Sedgwick1995, 52). Susan McClary conjectures that the form originated in Africa or Peru, and explains that, whatever its origins, the chaconne became known across Europe for its irresistible repetitions, its lasciviousness, and the way it called the body to dance (McClary Reference McClary and Foster1995, 87–91).

Morris knows enough about music theory and aesthetics to conduct an orchestra, and The New York Times claimed that, musically speaking, Morris's “staging of Purcell's ‘Dido and Aeneas’ deserves a prominent place on any list of major operatic productions of the last quarter-century” (Teachout Reference Teachout1999). His choreography for Dido's lament is full of exquisite, eloquent movement variations on the word “fate,” as the libretto repeats “Remember me, but ah!/Forget my fate.”Footnote 25 Dido is at her most queenly in this scene, uncompromising and regal. Still, she is a queen dancing to a chaconne, a dance that once signified “forbidden bodily pleasures and potential social havoc” (McClary Reference McClary and Foster1995, 82). Morris lets the history of the chaconne imbue Dido's lament with its subversive sexuality and, in so doing, he reminds you in a sly way that Dido herself is a transposed character, with a heritage like that of the chaconne. She's not Greek; she's the Queen of Carthage; she's African. Furthermore, Morris cast Guillermo Resto in the role of Aeneas, which means that the part of the Greek hero is being performed by a nonwhite dancer with dreadlocks.

Dido's movements in her lament convey a language; everyone learns, in this scene, what it means when those splayed-apart fingers signifying “fate” retract themselves from the clear air and start pressing grimly into Dido's chest. However, the choreography of Dido's lament, like that of the Sorceress's masturbation scene, also invokes a history—most often a history of hidden sexualities and the imported, foreign, unspeakable parts of the artistic heritage of dance. The gestural language of Dido and Aeneas serves partly to illustrate this history, to say it out loud: a frank and hopeful fifty-minute speech-act. For Morris, with his antiphrastic use of literal referents and vulgar jokes about sex and choreography, dance is a layered and mobile language—a loosening of tongues. It is a tactical swerve away from flat, rote, well-ordered modes of signifying and toward the possibility that movement—bodily articulation—can be parasitic on normative systems of identity. At the end of the piece, when Dido is draped over the bench in her death-gesture, the audience sees her monumental body, and the power of her last gesture, but we must also see the palimpsest of the other bodies inscribed within hers—the Sorceress, a male dancer, a choreographer, a queen who occasionally pretended to confuse himself with Fabiola of Belgium, a reincarnation of Martha Graham, a new Nijinsky or Ted Shawn. As the dancers exit in solemn pairs, leaving Dido's body alone on the stage, the lights slowly fade down to this image—an open act of transposition.