Introduction

The conventional division of labour by gender in hunter-gatherer society has many exceptions in the ethnographic record (Ingold Reference Ingold1986: 87). Areas of male or female exclusivity nonetheless exist, with hunting as the primary domain of men, and gathering as that of women (Winterhalder Reference Winterhalder, Panter-Brick, Layton and Rowley-Conwy2001: 26). Among southern African hunter-gatherers, the subsistence contribution of men dominates the archaeological record, leaving the role of women far less visible (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2002). Although the roles of men and women were traditionally articulated and reinforced through rites of initiation (Barnard Reference Barnard1992), this practice has left little archaeological trace.

Hunter-gatherer ritual practices in this region are known mainly from rock art and comparative ethnographic studies that document a complex set of beliefs in supernatural agency and the mediation of specialist shamans (Lewis-Williams Reference Lewis-Williams1998). This, however, is in contrast with evidence of a highly developed knowledge of the natural world (Lee Reference Lee1979); our understanding of hunter-gatherer religious life therefore rests on different premises from those of the models and constructs that inform studies of subsistence behaviour (Kinahan Reference Kinahan, Ucko and Layton1999). To resolve this Durkheimian polarity it is necessary to explore evidence and arguments that bridge the two domains. This problem is addressed here by pursuing the line of research pioneered by Eastwood (Reference Eastwood2005, Reference Eastwood2006), who found a link between women's initiation and the female kudu (Tragelaphus strepciceros).

The evidence for women's initiation presented here centres on a rock engraving from the site of /Ui-//aes on the edge of the Namib Desert, in which a female kudu shows an array of ritually diagnostic features. The engraved panel also features images that I interpret as representations of ritual seclusion shelters used by initiates; these are matched by remains of small stone enclosures that can still be seen adjacent to the engravings, in a space that was probably used for the performance of initiation dances. I link this evidence of shamanic art and ritual performance to the landscape of women's daily work to show that the material expression of religious metaphor is not confined to figurative art. The field evidence shows that the behaviour of the female kudu and its depiction in rock art related to the rite of initiation are reprised in the posture adopted by women to grind wild grass seed. A link is thus demonstrated between ritual art and the utilitarian grindstone, via the kudu as a nexus of precept and practice.

The Dancing Kudu

The Namib Desert is a hyper-arid zone stretching over approximately 2000km along the south-western coast of Africa. There are extensive gravel plains and dune-fields almost entirely lacking in vegetation between the Atlantic coast and a broken longitudinal escarpment approximately 200km inland. Ephemeral drainage lines have narrow ribbons of riparian woodland, and there are desert inselbergs with occasional springs and local concentrations of plant and animal life. The post-Pleistocene archaeological record shows significantly expanded occupation in the mid-Holocene optimum, associated with major concentrations of rock art. Hunter-gatherer subsistence ecology during the last 5000 years involved a range of increasingly specialised desert adaptations and a pattern of movement reflecting the unpredictability of rainfall events (Kinahan Reference Kinahan, Smith and Hesse2005).

Although its resources are extremely sparse, the desert supports several nomadic antelope species and resident populations of larger mammals, such as elephant, zebra and giraffe. These all figure prominently in the rock art of the Namib, which ranges from sites with single isolated works to some with large, intricate friezes of more than one hundred animal and human figures. The importance of some animals as sources of supernatural power essential to the work of the shaman is well established throughout southern Africa (Lewis-Williams & Dowson Reference Lewis-Williams and Dowson1989). There are, however, marked regional variations in the content of the art, and the significance of some motifs has only begun to emerge (Hampson et al. Reference Hampson, Challis, Blundell and de Rosner2002). In the Limpopo Valley, Eastwood (Reference Eastwood2006) noted the association of kudu, primarily females, with paintings of women moving in file as if dancing, and depictions of the apron worn in girls’ puberty or initiation rites, as observed in ethnographic field studies. The paintings of kudu displayed a number of characteristic postures that suggested oestrus and mating behaviour, and these corresponded to several specimens of historical San folklore relating to initiation rites.

While they are relatively numerous in the wooded environment of the Limpopo Valley, kudu are uncommon in the Namib; they are browsers by nature and therefore mainly confined to areas with shrubs or trees. Kudu are also scarce in the rock art of the Namib: one sample of 815 identifiable painted motifs spread over 44 sites in the Hungorob ravine included only 14 kudu (Kinahan Reference Kinahan2001: 20). At the site of /Ui-//aes (known also as Twyfelfontein), which contains probably the largest concentration of rock engravings in southern Africa (Dowson Reference Dowson1992), only 7 kudu occur among 2075 identifiable motifs (Kinahan Reference Kinahan2010). One of these, discussed in detail below, is known as the Dancing Kudu due to its elegantly mobile appearance. The location of these and other sites mentioned is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The location of the archaeological sites mentioned in the text; A) /Ui-//aes (Dancing Kudu 63/K5); B) Guintib (seed-grinding site 50/3); C) Geiseb (female kudu painting 219/281); D) Gorrasis (seed-grinding site 42/22). Site references relate to the records of the Namib Desert Archaeological Survey.

Rock engravings at /Ui-//aes (Figure 2) were executed on a hard quartzitic sandstone, employing a number of techniques. The most common is shallow pecking, used to define the outline of the subject, as opposed to deep pecking that removed the cortex within the body of the subject. False shading involves the removal of some cortex to create colour variation in the body, such as markings on the coat of an antelope or the stripes of a zebra. More sophisticated is the technique of false relief, where the outline is deeply incised and the cortex removed in the body area to allow shaping of muscle-folds and other details, which become vividly apparent under oblique lighting. The most unusual technique at the site is flat polishing, of which there are only two examples; both are female kudu. The significance of flat polishing to depict the female kudu is critical to the argument in this paper.

Figure 2. A view of /Ui-//aes from the south. The Dancing Kudu panel is located on the right-hand edge of the open area near the centre of the image.

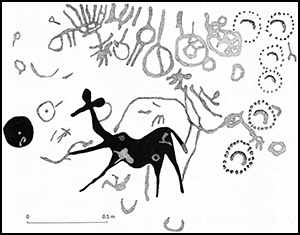

The Dancing Kudu (Figure 3) is surrounded by intersecting lines and super-positioned motifs, indicating that the panel is the result of successive episodes of engraving. The upper edge of the panel has an array of non-figurative motifs, including some with bifurcations and inner divisions suggestive of optical entoptic phenomena (Lewis-Williams & Dowson Reference Lewis-Williams and Dowson1989). Others have radiating appendages suggestive of polymelia, the sensation of having multiple limbs; both of these are linked to physical symptoms associated with the first stages of altered consciousness in ritual trance (Whitley Reference Whitley1998). Some of the engravings may be coeval, although I will argue that the kudu is more certainly associated with the six repetitive motifs to the right, each comprising a single arcuate line surrounded by a circle of closely spaced points. It is important to note that in each of these the opening of the arc faces in the same direction.

Figure 3. The Dancing Kudu panel; solid areas are flat polished, otherwise deep pecked.

The posture and appearance of the Dancing Kudu illustrates the female of the species in the context of mating behaviour. When courting, for example, the female lowers her neck and stretches forward (Estes Reference Estes1991: 171)—as shown in Figure 3—thus hollowing the back and raising the hindquarters. Eastwood (Reference Eastwood2006: 35) points out that kudu in oestrus have swollen vulvae, and this may be indicated here by the slightly raised tail. Most conclusive, however, is the heavily distended belly, showing that the kudu is at an advanced stage of pregnancy, thus linking womanhood and fecundity. Further comparison with the Limpopo Valley rock art is difficult because that of /Ui-//aes is almost entirely without human figures, and there is no obvious direct comparison with the lines of clapping women noted in Eastwood's (Reference Eastwood2005, Reference Eastwood2006) accounts of female initiation imagery.

The non-figurative motifs at the top of the panel fall within the range of forms that Smith and Ouzman (Reference Smith and Ouzman2004) have attributed to the geometric art tradition of Khoekhoen pastoralists of the last two millennia in southern Africa. The circles of closely spaced points to the right of the Dancing Kudu, however, have no equivalent in that tradition. Although they have been described by Dowson (Reference Dowson1992: 119, pl. 173) as entoptic patterns associated with the onset of altered consciousness in ritual trance, I suggest that these are more likely to represent women dancing in procession around the seclusion shelter of an initiate, as described by Marshall (Reference Marshall1999) and McGranaghan (Reference McGranaghan2015), the arc-shaped line within the circle representing the shelter itself. Depictions of physical structures, such as huts or rockshelters, while uncommon, are widely distributed in the rock art of southern Africa (Lewis-Williams Reference Lewis-Williams1981), and considered by Eastwood (Reference Eastwood2005: 16) to represent the notion of confinement or seclusion during initiation.

Figure 4 is from the work of Lorna Marshall among Kalahari San (see Marshall Reference Marshall1999), and shows a procession of dancing women encircling the seclusion shelter occupied by a young woman for the duration of her first menstruation. While in seclusion, the initiate is instructed by elderly relatives on how to conduct herself as an adult in society (Guenther Reference Guenther1999). Her transition is also marked by various dances, using the habits of culturally important animals to dramatise social values and customs (Marshall Reference Marshall1999). These would include eland, oryx or, in this case, the kudu: gentle, sociable, sexually submissive and known to care for its young until they are almost fully grown (Estes Reference Estes1991: 169). These dances may involve a shaman (Barnard Reference Barnard1980) because initiation is a rite of passage or transition from one state to another and therefore falls within the sphere of shamanic practice (Lewis-Williams & Pearce Reference Lewis-Williams and Pearce2004). Equally important here is the structured opposition of male and female as a necessary and recurrent theme in such narratives (Biesele Reference Biesele1993). Older male relatives may therefore be called upon to act as male antelope, but women may also attach sticks to their heads as horns and adopt this role (Eastwood Reference Eastwood2005).

Figure 4. Women dancing around a !Kung San girl's initiation shelter of branches and leaves. Photograph: Laurence K. Marshall and Lorna J. Marshall, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, PM#2001.29.686 (digital file# 98800027).

The Dancing Kudu panel at /Ui-//aes overlooks an area of level sand among large boulders fallen from the cliffs above. This setting contributes a degree of acoustic resonance to the site that may have influenced its selection as a space for ritual dance, as Rifkin (Reference Rifkin2009) has demonstrated elsewhere in southern Africa. The stone circles within this space appear to be the remains of small huts or shelters (Figure 5). Relatively intact circles have a mean diameter of 2.1m (SD 0.43m; n = 5). Significantly, the circles have no associated occupation debris, such as artefact waste, bone fragments, pottery and hearth ash, as is characteristic of small encampments of huts commonly found in the Namib (Kinahan Reference Kinahan2001: 67–68). Rather than facing inward as in an encampment, the openings of these circles face towards the Dancing Kudu panel, with a more-or-less common mean orientation of 59° (SD 6.4°; n = 4). Thus, the stone circles and the Dancing Kudu panel appear to be component parts of an integrated performance space (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Stone circle remnant of seclusion shelter at the Dancing Kudu panel (outer diameter 1.97m).

Figure 6. The Dancing Kudu panel in relation to seclusion shelters and the level sandy area that may have been used for initiation ritual performances, with inset showing resonance at the point marked ‘R’.

In this environment, the small but reliable spring at /Ui-//aes would have been a critical resource during the dry season, and the great proliferation of rock art at the site is indicative of a high level of ritual activity. This would have been occasioned by prolonged aggregation, resulting in heightened social tensions over diminishing food resources (cf. Lee Reference Lee and Spooner1972). Aggregation was, however, also associated with other ritual events, such as initiation, when normally dispersed family members are brought together (Marshall Reference Marshall1999).

Harvest in the desert

After the rains, ephemeral surface water made it possible for hunter-gatherers in the Namib to reach otherwise inaccessible sites. During the last thousand years one of the most important and specialised desert subsistence strategies involved the gathering of grass seed from underground caches of harvester ants (Kinahan Reference Kinahan2001). In some areas women today excavate the seed and clean it by winnowing, accumulating large stores as staple food and a hedge against famine (Sullivan Reference Sullivan1998). Well-preserved evidence of seed-diggings is visible in remote parts of the desert, indicating that long expeditions were made for this purpose. An apparent absence of seed-digging and -processing sites at /Ui-//aes might indicate that this was a dry-season site, where larger groupings of people could not be sustained by such relatively slender resources.

Seed-diggings, which generally occur as conspicuous clusters extending over 5km2 or more, are recognisable from two common indicators: the presence of small boulders carried from geologically distinct outcrops and that are used to break open the nests; and rock fragments showing calcareous crusting on their upper surface that could only have formed on their underside prior to being overturned in the course of digging. Other related features include temporary bivouac sites commonly associated with pottery, and hollow stone cairns that were probably used to store grass seed. This, and the absence of the stone artefact debris, discarded bone and ashy deposits usually found at hunting camps in the Namib, supports the inference that these sites may have been occupied by parties of women. Further processing of the seed to make gruel was carried out in the vicinity of more centrally located basecamps, using flat grindstones, which were either loose slabs or suitable surfaces of outcropping granite.

Two communal seed-processing sites, at Guintib and Gorrasis (Figure 1), have well-preserved grinding hollows. Measurements of the polished surfaces of 20 examples from each of the two sites yielded a mean length of 0.63m (SD 0.08m; n = 40). Assuming that stroke-length of grinding hollows is proportional to human stature (cf. Mohanty et al. Reference Mohanty, Babu and Nair2001), the grinding hollows yield an estimated mean stature of 1.49m (SD 0.12m; n = 40). This is comparable to estimates based on human female skeletal remains from the Namib Desert, indicating a mean stature of 1.51m (SD 0.04m; n = 7) (Kinahan Reference Kinahan2013). Yet the stroke-length measured on the grinding hollows requires an all-fours position, rather than the more usual seated position, which would produce a markedly shorter stroke-length. In the all-fours position the back is hollowed, and at full stretch the pelvis is raised (Figure 7), reproducing the posture of the sexually receptive female kudu, both in life and as depicted in the Dancing Kudu panel at /Ui-//aes.

Figure 7. Inferred all-fours posture and range of movement required to reproduce the stroke-length of seed-grinding hollows in the Namib Desert (after Kinahan Reference Kinahan2013).

The grinding hollow sites offer three other suggestive parallels to the Dancing Kudu engraving as a component of female initiation. First, initiation sites are places of seclusion, the female removed partly so that men can avoid contact with menstrual blood (Marshall Reference Marshall1999); the seed-grinding sites, similarly, are several hundred metres from evidence of encampment and are thus clearly secluded or separated from the encampment. These may have been women's places and not necessarily initiation sites, although this possibility should not be excluded. Second, the body of the Dancing Kudu is one of only two such highly polished engravings. The rock lies at an acute angle and could not have been used for grinding, but the surface is suggestive of a grinding hollow; the use of this technique on kudu, but on none of the other engraved motifs known at /Ui-//aes or elsewhere in the Namib, strongly implies a link between the habits of the female kudu and the work of women in preparing grass seed. This link probably related to the customary duties of women as well as the way women co-operated in their work, akin to kudu in the wild. Finally, the seed-grinding sites are associated with unusually shaped rock hollows that fill with water when it rains. Unlike most rock hollows produced by natural weathering of outcropping granite, which are circular in shape, these have formed on natural fractures and have the elongated shape of a vulva. This recalls the state of oestrus in the female kudu, noted by Eastwood (Reference Eastwood2006).

A rockshelter at Geiseb (Figure 1), in the vicinity of a seed-digging area, has a unique painting of a female kudu (Figure 8) positioned above a highly polished grinding hollow. The painting is vivid and appears more recent in date than the faint traces of two faded monochrome antelope on the same rock surface. The presence of the kudu painting at what may be a women's bivouac site, in an area that has no basecamp sites or other occupation evidence, raises the tantalising possibility that the association of women and female kudu may have been articulated through rock painting by women who were ritual specialists in their own right, as Solomon (Reference Solomon1992) and Stevenson (Reference Stevenson1995) argue. The rarity of the occurrence suggests, moreover, that an occasion (or even necessity) may have arisen in which healing or other ritual intervention was needed, thus pointing to a deeper level at which the female kudu figured in the affairs of women on seed-digging expeditions.

Figure 8. Female kudu painting at women's bivouac site, Geiseb (see Figure 1).

It is noteworthy that parties of female kudu visit rockshelters located on hillsides and in narrow ravines to escape the midday sun and the hot desert winds. These sites, often in seed-digging areas and with indications of use as women's bivouacs, sometimes have kudu droppings and evidence of dust-bathing. The back wall of the shelter may also have patches on the rock-face rubbed to a high gloss by kudu sheltering there. Thus, there are correspondences between the evidence of female initiation at /Ui-//aes and the mundane tasks of seed-digging and -processing, with the female kudu as the common denominator. The social customs and values made explicit in initiation rites are also evident in the physical process of seed-grinding; with the outward expression of female kudu posture, and in a more subtle sense where women and kudu appear to mingle in the landscape, to the extent that women at work, finding and harvesting caches of grass seed, behave in a way that resembles the behaviour of the kudu.

Estes (Reference Estes1991: 169–84) describes female kudu as forming stable groups of up to 15, sometimes including several cows accompanied by their young offspring. This behaviour is in contrast to the generally transient association of males in bachelor herds. When a male approaches a female in oestrus, any young male offspring accompanying her are displaced. After mating, the cow will re-join the female herd. In the Namib, groups of females usually remain within the thorn-bush flanking dry watercourses or, most commonly, in rocky terrain at the foot of the desert escarpment, within reach of water. The composition of the groups, their relative stability, mobility and association with rockshelters and water points all present a close parallel with some of the archaeological evidence associated with the subsistence activities of women.

Finally, seed-digging involves the opening and disturbance of active harvester ant colonies. Seed caches may lie almost 1m below the surface and contain several kilograms of seed. It is clearly evident from these sites that the emptied nests are closed up again afterwards, with the loose rock and soil removed in the process. In some instances, nests appear to have been emptied several times and would have been visited over a number of years, leaving small areas cleared of surface rubble that was used to refill the cavities of the ant nests. The custom regarding desert melon patches, which are treated as property and inherited in the female line (Kinahan Reference Kinahan2001: 98), may well have also applied to seed-diggings. Either way, the resource was evidently curated, suggesting a degree of domestication, such that the desert was a landscape of familiar places and resources in which women, like their female kudu counterparts, could move as they wished.

Discussion

Ambiguities in possible rock art evidence for women's initiation rites led Lewis-Williams (Reference Lewis-Williams1998) to conclude that there are few, if any, explicit examples in the rock art of the southern Drakensberg, where most of his research was focused. In contrast, the Limpopo Valley studied by Eastwood (Reference Eastwood2005) yielded a consistent association between women, moving in file or dancing, and the female kudu, which he identified as a key element of women's initiation in that region. This observation agrees with the view of Solomon (Reference Solomon1992, Reference Solomon2000) that the art and the ritual life of the San were structured around gender roles, with a specifically female component articulated through rites of initiation.

The evidence presented here confirms the existence of women's initiation in the rock art of the Namib at /Ui-//aes, and points towards a more complex participation of women in the wider context of ritual activity. This evidence, as with that of the Limpopo Valley, shows that regional variations in a basically unitary tradition of ritual art can open new lines of enquiry. One of these concerns the way in which the female kudu held significance beyond initiation ritual, as a pervasive element in the everyday life of women. Another concerns mounting evidence in the Namib and elsewhere that the ritual life of southern African hunter-gatherers was more dynamic and innovative than previously thought. This evidence suggests that rites of initiation may have been modified or even adopted as a consequence of interaction with farming communities as they spread through the subcontinent during the last two millennia.

Elements of San symbolic tradition occur in material culture, folklore and language, outside the context of shamanic practice (e.g. Wiessner Reference Wiessner1983). Thus, the posture of the female kudu in rock art refers to female initiation, but new evidence presented here indicates that the same posture adopted by a woman grinding grass seed to prepare as food refers to the same precepts. Indeed, there seem to be multiple cross-references, still incompletely understood, between ritual practice, the female kudu as a metaphor and paragon, and ordinary tasks in the daily life of women. Such links would, therefore, suggest that a utilitarian grinding hollow may hold greater cultural significance than has been previously recognised. This raises the question whether rock art, as a corpus of graphic and figurative representation, is sufficient to represent the symbolic and ritual concerns of hunter-gatherer society. This is important because only a small part of the subcontinent formerly occupied by hunter-gatherer groups is rich in rock art; to understand the beliefs of groups who inhabited these areas more fully, it will be necessary to extend our understanding, informed by the rock art, to other classes of evidence. These range from stone artefact assemblages to the selection and butchery of prey species, all in some way determined by an ideology that is also evident in shamanic ritual and rock art.

Initiation and the transition to womanhood under the guidance of the shaman is articulated in the Dancing Kudu, which is shown in the mating posture of oestrus and, at the same time, as pregnant. The engraving therefore combines the moments of entering adulthood and that of being fully adult. This is symbolic because in nature a pregnant female would not experience oestrus. A further indication of this liminality may be suggested by the uncharacteristically narrow head and long tapering muzzle of the animal (Figure 3), which resembles that of an antbear (Orycteropus afer). Although it has a patchy distribution in the rock art of southern Africa (e.g. Garlake Reference Garlake1995; Eastwood & Eastwood Reference Eastwood and Eastwood2006: 107), the antbear holds a general significance in San belief (e.g. Forsmann & Gutteridge Reference Forsmann and Gutteridge2012). This relates to some of its striking characteristics, including the humanlike possession of five digits on the hind limbs (Smithers Reference Smithers1986: 131). Moreover, it is nocturnal and lives in deep underground burrows, moving, like the shaman, between this world and the underworld. Here, a possible conflation of antbear and kudu may be related to the prominent hindquarters and abundant adipose tissue, both associated with fecundity and womanhood.

The link between female initiation and seed-gathering in the Namib indicates a shift in ritual practice, with the arrival of food production involving both domestic livestock (Kinahan Reference Kinahan2016) and intensified exploitation of wild plant foods, such as grass seed. Seed-gathering in the Namib is associated with radiocarbon dates from the early second millennium AD and the appearance of bag-shaped pottery (Kinahan Reference Kinahan2001: 59). The pottery, found both in nomadic pastoral and hunter-gatherer contexts, was essential to the processing of plant foods, one of the most important being wild grass seed. The integration of seed-gathering with the habits of the female kudu, and the apparent restriction of the flat polishing to the engraving of the Dancing Kudu at /Ui-//aes, provide a further evidential link between initiation ritual and the everyday work of women.

Departing from an earlier view that southern African hunter-gatherer religious beliefs remained essentially unchanged over the entire Holocene (Lewis-Williams Reference Lewis-Williams and Schrire1984), recent studies suggest that hunter-gatherers adopted some ritual practices through contact with farming communities (Jolly Reference Jolly1995, Reference Jolly1996; Blundell Reference Blundell2004; Hollmann Reference Hollmann2015). This agrees with the evidence for female initiation reported by Eastwood (Reference Eastwood2005) associated with hunter-gatherers who lived in the Limpopo Valley at the same time as Bantu-speaking farmers, who had established traditions of initiation (cf. Mitchell Reference Mitchell2002: 284). The broader social context of ritual was therefore more complex than previously considered and in Namibia, at least, it appears that specialised shamanism may have developed only in the last two millennia, as nomadic pastoralism spread into the desert (Kinahan Reference Kinahan2001: 44–46). This suggests that key elements of ritual practice among southern African hunter-gatherers, including initiation (Barnard Reference Barnard1980), might be similarly recent innovations reflecting the shifting social relations between these and other groups of people (Lewis-Williams Reference Lewis-Williams1995: 144).

Conclusions

The central importance of the female kudu in the rock art of widely separated regions, such as the Namib Desert and the Limpopo Valley in southern Africa, shows that women's initiation rites implicating the kudu have developed from fundamental precepts in this diverse yet unitary belief system. In the Namib, however, there seems to be a syncretic combination of a basic initiation metaphor, involving the female kudu, and a more elaborate extension of it into the domain of women's work involving grass seed-gathering and -processing—a relatively recent innovation based partly on the adoption of pottery. Hunter-gatherers in the Namib Desert were clearly receptive to such innovations, turning these to their advantage in increasingly specialised subsistence strategies. Systematic exploitation, processing and storage of wild grass seed added a new dimension to the work of women, making their role in the hunter-gatherer economy more formal and more visible in the archaeological record. It is unsurprising that such practices, which seem to have absorbed a great part of the subsistence effort of women, also found expression in ritual life.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Paul Lane for the opportunity to present this paper at the 4th International Landscape Archaeology Conference held at Uppsala University, Sweden, in August 2016.