The Chicago School of antitrust, which has by and large held sway in the United States from the late 1970s to the present, is under attack. Unsurprisingly, the Chicago School is facing a good deal of fire from the left: from organizations like the Open Markets Institute, anticorporate Progressives like Senator Elizabeth Warren, and the Congressional Democratic leadership.Footnote 1 More surprisingly to many observers, antitrust reformist sentiment is also growing on the right, from a diverse array of voices including President Donald Trump and influential “never-Trumper” Bill Kristol.Footnote 2 The American Conservative recently turned with surprising ferocity on the Chicago School icon Robert Bork, asserting that “whereas prior generations of lawmakers protected the American citizenry as businessmen, entrepreneurs, and growers, Bork led a revolution that sacrificed the small producer at the altar of efficiency and cheap goods.”Footnote 3

But although Chicago faces formidable headwinds that could well spell its demise, it is surely premature to consider it buried. For all of the criticisms of the Chicago School, there is not an obvious replacement in sight. The antitrust profession, though divided on many enforcement questions, remains strongly committed to the consumer welfare model that Chicago inaugurated. Most significantly, there remains the fact that in the United States, antitrust policy (outside the merger area) is largely made by the courts rather than by Congress or the Executive Branch, and the courts often take decades to adopt new paradigms.

So if Chicago isn't dead, then why conduct a postmortem? The answer lies in the fact that, over its 120-year history, American antitrust policy has been characterized by the rise and fall of many different ideological schools: marginalism, populism, Progressivism, associationalism, Brandeisianism, structuralism, and many others.Footnote 4 During the New Deal administration alone, three very different schools of thought on antitrust policy prevailed at different times.Footnote 5 Thirty to forty years seems like a long shelf life for any one ideological school to reign over antitrust policy. However much longer the Chicago School may prevail, it is surely not the end of history.

Any fair assessment of the Chicago School's effects on U.S. antitrust enforcement must move beyond the conventional assumption that “Chicago killed antitrust enforcement.” Although Chicago School influences certainly contributed to a curtailment of antitrust enforcement in some areas and an overall decline in antitrust activity, both public and private, the Chicago School did not support repeal of the antitrust laws as a whole but rather a shift in enforcement priorities. Consistent with Chicago's generally deregulatory proclivity, many of Chicago's antitrust prescriptions were directed against the state; that is to say, Chicago tended to view antitrust as a deregulatory tool. Still, even deployments of antitrust tools in support of laissez-faire contributed to the reinforcement of antitrust law as a permanent institution of the American mixed capitalist economy. Chicago's antitrust legacy is not abolition but rather solidification of antitrust's position in the bipartisan mainstream of market regulation.

A (Non-Premature) Postmortem for Brandeisianism and Structuralism

In order to understand the Chicago School, one must understand from where it came or, more particularly in a dialectic sense, against what it reacted. Chicago's complex story begins with the Brandeisian and structuralist schools that preceded it.

The Brandeisian school that dominated U.S. antitrust policy during much of the twentieth century is epitomized in the title of Louis Brandeis's 1914 essay (subsequently made the title of a 1934 collection of his essays) in Harper's Weekly: “The Curse of Bigness.”Footnote 6 Arguing for “regulated competition” over “regulated monopoly,” Brandeis asserted that it was necessary to “[curb] physically the strong, to protect those physically weaker,” in order to sustain industrial liberty.Footnote 7 Brandeis evoked a Jeffersonian vision of a social-economic order organized on a small scale, with atomistic competition between a large number of equally advantaged units. His goals included the economic, social, and political.Footnote 8 As explained in a dissenting opinion by William O. Douglas in the 1948 Columbia Steel case, Brandeis worried that “size can become a menace—both industrial and social. It can be an industrial menace because it creates gross inequalities against existing or putative competitors. It can be a social menace—because of its control of prices.”Footnote 9

The Brandeisians also feared the corrosive effect of concentrated industrial power on politics, government, and democracy itself. This facet of Brandeisian ideology gained prominence in the period following World War II, when congressional leaders promoting the 1950 Celler-Kefauver Act, which amended and strengthened the antimerger provisions of the 1914 Clayton Act, laid the blame for the rise of Nazism squarely at the feet of industrial concentration in Germany and proposed aggressive antitrust enforcement to thwart both fascism and the rising tide of Communism.Footnote 10

The Brandeisian vision held sway in U.S. antitrust from the Progressive Era through the early 1970s, albeit with significant interruptions.Footnote 11 Its spirit animates a long chain of important cases—from Chicago Board of Trade in 1918 (opinion authored by Brandeis himself upholding Chicago Board of Trade trading restrictions intended to level the playing field among larger and smaller market participants) to TOPCO in 1972 (striking down a supermarket cooperative's exclusive territories system as a horizontal restraint inconsistent with free competition)—and a string of congressional reforms including the Clayton and Federal Trade Commission Acts of 1914 and the Robinson-Patman Act of 1936.Footnote 12

The two leading postwar schools of U.S. antitrust law that would eventually replace Brandeisianism are named after Harvard University and the University of Chicago because of their early association with scholars at those schools, even though much of the work of both schools was carried out elsewhere. The structuralist school became known as the Harvard School because of its association with Harvard professors Carl Kaysen, Donald Turner, and Phil Areeda and Joe Bain, a Harvard-trained economist who spent the bulk of his career at the University of California at Berkeley.Footnote 13 The Chicago School derived its name from work by Chicago scholars such as Richard Posner, George Stigler, Aaron Director, Edward Levi, and Frank Easterbrook. But none more carried the flag than Bork, a Yale professor who was trained at Chicago, whose 1978 The Antitrust Paradox remains the Chicago School bible, and Bill Baxter, a Stanford law professor who served as head of the Antitrust Division in the Ronald Reagan administration and was responsible for the AT&T breakup.

Harvard's structuralist school prevailed in U.S. antitrust law from 1950, the year of the Celler-Kefauver amendments to section 7 of the Clayton Act, until the late 1970s, when the Chicago School made a dramatic entrance at the Supreme Court. Without rejecting many of the Brandeisian policy prescriptions, structuralism shifted the focus from antitrust as a political and social ideology to antitrust as a technical economic regulatory tool, setting the stage for an even more pronounced emphasis on economics during the Chicago School era. Structuralism's core tenet posited that a strong, deterministic relationship exists between a market's structure, conduct, and performance (thus giving rise to the structure-conduct-performance, or SCP, paradigm). Concentration was the most significant component of structure. Thus, a highly concentrated market inexorably led to anticompetitive firm behavior, and such behavior inexorably led to poor market performance, expressed as higher prices, less innovation, and lower quality. The upshot was that the government could directly attack concentrated market structures without worrying about the specific mechanisms (conduct) that led from that structure to poor market performance.Footnote 14

Structuralism reached its peak in the 1960s, when the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Justice Department brought a succession of increasingly aggressive antimerger cases that ended up in the Supreme Court, with inevitable victory for the government. Many of these cases prohibited mergers that seem quite benign by contemporary economic and enforcement standards. For example, in United States v. Pabst Brewing Co., the Supreme Court prohibited a merger between the nation's tenth- and eighteenth-largest beer brewing companies, whose collective market share was less than 12 percent in the Wisconsin/Illinois/Michigan area asserted to be the relevant geographic market and less than 5 percent nationally.Footnote 15 Similarly, in United States v. Von's Grocery Co., the court prohibited a merger between two Los Angeles grocery chains that had a collective market share of less than 9 percent in a market where the top twelve chains’ market share was less than 50 percent.Footnote 16 If analyzed under the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, which is widely used today to assess market concentration, the market's resulting concentration level would have been less than 300 with a delta of less than 40, figures that would not even register on the antitrust agencies’ radars today.Footnote 17 Dissenting in Von's Grocery, Justice Stewart complained bitterly that “the Court has substituted bare conjecture for the statutory standard of reasonable probability that competition be lessened. … The sole consistency that I can find [in the court's decisions] is that in litigation under § 7 [of the Clayton Act], the Government always wins.” Many in the business community concurred with Justice Stewart's assessment that the antitrust agencies and Supreme Court had increasingly indulged in outright hostility to mergers as a whole, whether or not they seriously threatened competition.

Structuralism prevailed in the academy, antitrust agencies, courts, and political institutions until the mid-1970s. In late 1967, President Lyndon Johnson secretly asked Phil Neal, dean of the University of Chicago Law School, to lead a commission of distinguished economists and lawyers to report on the state of competition in the United States and recommend potential changes to the antitrust laws.Footnote 18 Johnson intended to use the report as part of his reelection campaign but eventually decided not to seek reelection because of the unpopularity of the Vietnam War.Footnote 19 Nonetheless, the commission concluded its work and released its report. The report represented the high-water mark of structuralist thinking. It proposed a Concentrated Industries Act that would give the attorney general a mandate to “search out” oligopolies and order divestiture to the point that no firm would end up with a market share exceeding 12 percent. It also proposed a much stronger structuralist presumption in horizontal merger cases, condemning any merger in which the four-firm concentration ratio exceeded 50 percent and one of the firms involved in the merger had a market share exceeding 10 percent.

None of the report's recommendations was adopted into law. Not only did Richard Nixon's election kill off its immediate political prospects, but by the early 1970s the Chicago School was rapidly eroding structuralism's theoretical and empirical assumptions. In the 1970s, Don Turner underwent a self-described “conversion experience” in which he accepted many of the Chicago School critiques of the SCP paradigm.Footnote 20 Vestiges of structuralist thinking appeared as late as 1979, when Jimmy Carter's National Commission to Review Antitrust Law and Procedures recommended adoption of a no-fault monopolization statute, and in the early 1980s in various iterations of the Justice Department and FTC's Horizontal Merger Guidelines and some enforcement actions, but the SCP paradigm had long since been intellectually and politically vanquished. The Harvard School that had undergirded the antimerger regime of the 1950s and 1960s morphed into a neo–Harvard School that focused on institutionalism rather than structuralism.Footnote 21 Neo-Harvard adherents, perhaps best represented by Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, took a more cautious approach toward antitrust enforcement in light of the perceived limitations of antitrust enforcement procedures and institutions, such as private litigants, juries, and generalist judges.Footnote 22

Although, as will be discussed momentarily, the Chicago School consisted of a wider variety of perspectives and approaches than commonly believed, I will categorize Chicago School attacks on the structuralist and Brandeisian schools that preceded it into four pillars. First, Chicago argued that antitrust policy had been floundering among inconsistent goals, including such ideas as preserving small business for its own sake and protecting less efficient firms from more efficient rivals. According to the Chicago School, antitrust needed a single, organizing objective. Consumer welfare was the only viable candidate in light of the antitrust laws’ text and legislative history and sound principles of microeconomics.

Second, Chicago School scholars attacked structuralism's empirical claims, demonstrating that assertions regarding the deterministic relationship between market structure and performance were based on faulty empirical assumptions. For example, economist George Stigler showed that the relationship between industry concentration and rates of return on capital was very weak, suggesting that an anticoncentration antitrust policy would do relatively little to prevent firms from earning monopoly profits.Footnote 23

Third, Chicago School scholars argued that many practices previously thought of as anticompetitive could not be explained on the grounds asserted by their critics. Thus, tying could not be the leverage of market power into a complementary market for the purpose of extracting a second monopoly rent, since that would simply cannibalize the rents in the tying market. Resale price maintenance could not be a device for granting market power to retailers, since that would encroach on the manufacturer's own profits.

Fourth, having dispelled the ostensible anticompetitive explanations for various business practices, Chicago then offered the actual, competitively benign or procompetitive explanation: tying accomplished price discrimination through metering; resale price maintenance responded to the threat of retailer free riding on the promotional activities of other retailers.Footnote 24 And so forth.

What explains Chicago's sudden and complete triumph over structuralism? Both general political and antitrust-specific factors were at play. At a general level, Chicago School “consumer welfarism” landed at a time of simultaneous consumerist and deregulatory sentiment and thus managed to resonate with both Naderism and Reaganism. At a more specific level, Chicago profited from the abandonment of Harvard School theoretical and empirical claims by leading structuralists, particularly Turner. It also benefited from a simplicity (critics would say simple-mindedness) of exposition that made its core tenets easily adoptable by courts. Doctrines like the “one monopoly profit theorem” or the “alignment of the consumer and manufacturer interest in avoiding retailer market power” were easily absorbed into legal analysis because the core observation was easy to state in a sentence or two.

By contrast, much of the “post-Chicago” critique of Chicago arises from complex theoretical work in game theory, behavioralism, or economic modeling with uncertain predictive power. It is not as easy for judges to adopt such complex and circumstantially contingent insights into maxims of law. Critics can resist generalization of the post-Chicago insights by observing that the results are frequently dependent on idiosyncratic parameters or assumptions. Even judges well read in some of the post-Chicago literature find it difficult to put the theories into practice, as occurred in the Justice Department's failed predatory-pricing case against American Airlines. The federal court of appeals for the Tenth Circuit acknowledged the post-Chicago literature on predation, asserted that in light of the new literature it would not approach predation claims “with the incredulity that once prevailed,” and then ran along to reject the government's case, applying the conventional price/cost test.Footnote 25

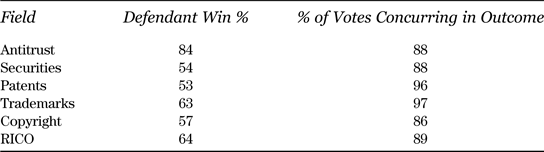

The statistics on antitrust cases in the Supreme Court in the last several decades demonstrate the breadth and depth of the Chicago revolution. Table 1 compares antitrust cases to other business law arising under federal law, such as securities, intellectual property, and claims under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO claims). A common factor in all categories of business cases is a high degree of consensus among the justices on the appropriate outcome. Across all cases, near-unanimity was the rule, with, on average, only about one dissent per decision. In all areas other than antitrust, the defendant win rate evidences a slightly pro-defendant court, with a defendant win rate of 53 to 64 percent. By contrast, the defendant win rate in antitrust cases since 1994 has been 84 percent—a figure that includes a span between 1994 and 2010 when defendants won every case before the Supreme Court.

Table 1 Supreme Court Civil Business Law Cases 1994–2017 by Percentage of Defendant Wins and Justices Voting in Favor of Prevailing Outcome

Source: Author's compilation from search of Westlaw database.

The Supreme Court's conservative, pro-defendant, or pro-business disposition is insufficient to explain the court's antitrust jurisprudence. As commentators have noted, in recent years the Supreme Court's antitrust jurisprudence reflects both Chicago School insights on economic theory and neo–Harvard School institutionalist insights, such as a suspicion that juries are incapable of deciding complex economic questions, concerns over the incentive-distorting effects of the treble damages remedy and class-action lawsuits, and a mistrust of competitor plaintiffs as ill motivated.Footnote 26 In combination, these impulses served to terminate the remaining vestiges of structuralism and Brandeisianism in U.S. antitrust jurisprudence.

Chicago and Laissez-Faire: A Complex Relationship

A conventional view holds that the Chicago School killed antitrust enforcement during the Reagan administration and ensures that the pro-enforcement position always loses.Footnote 27 No less an authority on the Chicago School than Richard Posner recently quipped that “antitrust is dead.”Footnote 28 That view is largely a caricature and fails to capture nuances that are important not only to understanding the Chicago School in historical context but also to prognosticating future trends and friction points in the evolution of antitrust policy.

A law and economics big tent

The view that the Chicago School advocated and practiced near complete nonintervention in antitrust ignores the breadth of opinion and emphasis in the school. Even as to Bork that would be an overstatement, but it emphatically fails to capture the influence and perspective of other important figures in the Chicago School. Take Posner—not the left-leaning Posner of the last decade or so but the Posner who as scholar and then judge exerted as much influence as anyone on the antitrust revolution. In important ways Posner's work supported enhanced intervention. Posner advocated finding cartel violations from mere “conscious parallelism,” argued for a long-run marginal cost test for predatory pricing (more favorable to plaintiffs than the short-run test proposed by Harvard School proponents Areeda and Turner), rejected using restrictive predatory-pricing rules to govern bundled discounts, articulated concerns over vertical foreclosure, rejected a “free riding” argument that the Chicago School supposedly accept reflexively, and argued that price discrimination may be, on average, output reducing.Footnote 29

What bound Bork, Posner, and other Chicago School figures together was the insistence that antitrust principles should be focused on efficiency and consumer welfare rather than populist political ideology. In 2001, reflecting back on the twenty-five years since publication of the first edition of his book Antitrust Law, Posner observed that he had subtitled the original version “An Economic Perspective” but was dropping the subtitle for the new version because “the other perspectives have largely fallen away.”Footnote 30 While today we may be witnessing the cyclical reemergence of the alternative political perspectives that seemed buried in 2001, Posner was clearly correct that economic reasoning had occupied the antitrust profession with lasting power.

The legacy and ongoing role of economic analysis in antitrust should not be mistaken for carte blanche laissez-faire. In recent years, the European Union—which has been more interventionist in antitrust cases than the United States—has been shifting away from a “form-based” or formal approach to competition cases, in which liability turned on whether the conduct at issue fell into a formally prohibited category (i.e., a loyalty-inducing discount by a firm with a certain market share flatly prohibited regardless of its economic effects) and in favor of an “effects based” or economic-functional approach (i.e., a loyalty-inducing discount granted by a dominant firm deemed illegal only if it foreclosed competitors from market access).Footnote 31 This transition has not resulted in the evisceration of antitrust policy; witness the European Commission's multibillion-euro fines on Intel and Google, justified in complex, economics-oriented decisions. Similarly, much of the “post-Chicago” literature calling for increased antitrust enforcement owes its currency to the Chicago School mainstreaming of economic theory in judicial and agency decision-making.

Consumer welfare

A conventional account has the Chicago School, or at least its Borkian wing, playing a nefarious bait-and-switch game over the normative goals of antitrust law.Footnote 32 This account goes as follows: Bork distorted the Sherman Act's legislative history to persuade the Supreme Court that Congress “meant” to adopt consumer welfare as the sole or primary goal of antitrust policy. Then, through a cheap parlor trick, Bork redefined consumer welfare to mean economic efficiency (essentially, by excluding wealth transfers from consideration since they are neutral from an efficiency perspective). The Chicago School thus suborned a judicial reduction of antitrust law to economic efficiency, from which point it could justify any business practice as plausibly efficiency-benign and hence legal.

I have rebutted this narrative elsewhere and will not repeat all of the particulars here.Footnote 33 Suffice it to say that there was nothing concealed in Bork's argument, and the Supreme Court did not adopt it wholesale. When the court held, citing Bork, that “Congress designed the Sherman Act as a ‘consumer welfare prescription,’” it did not resolve a host of issues internal to the very broad consumer welfare standard, including (1) whether productive efficiencies not passed on to consumers should be weighed against anticompetitive effects (the FTC and Justice Department's Horizontal Merger Guidelines say no); (2) how to consider practices that reduce deadweight losses but increase wealth transfers from consumers to producers; (3) how to conduct trade-offs between dynamic and static efficiency; and (4) how to weigh present consumer benefits against potential future harms, or vice versa.Footnote 34

These questions—and many others—create a wide space for contestation within the consumer welfare model and a range of potential attitudes toward enforcement, from permissive to gung ho. Tellingly, many voices in the anti-Chicago camp, including the strongly pro-enforcement American Antitrust Institute, have spoken out against the neo-Brandeisian/populist resurgence, arguing that antitrust reinvigoration should happen within the parameters of the consumer welfare standard.Footnote 35 The consumer welfare standard need not be, and in many cases has not been, a euphemism for “the defendant wins.”

Chicago and the state

Contrary to popular wisdom, Reagan did not kill off antitrust enforcement, nor did his Republican successors. Indeed, statistically, aggregate public enforcement has remained relatively stable from administration to administration over the past four decades.Footnote 36 What accounts for the perception that conservative administrations killed antitrust enforcement is that the types of cases selected for enforcement vary considerably with changes of administration. The Reagan administration brought a disproportionately large number of cartel cases in the roadbuilding and public procurement sectors, for example.Footnote 37

To be clear, I am not suggesting that the selection of types of cases to bring is unimportant. To the contrary, the selection of enforcement priorities has been underappreciated as an indicator of ideology and political commitments. Chicago's approach to antitrust enforcement reveals not abdication of enforcement but a genuine commitment to enforcement through a particular lens: that of a particular understood relationship between private markets and governmental actors.

Begin with the large number of cases brought in the roadbuilding and public procurement sectors. In most of those cases, the government was the purchaser of the overcharged services. Taxpayers were the victimized parties. The effects of the collusive behavior involved the exploitation of taxpayers and, given an even mildly progressive tax system, that meant that the cartel overcharges may have worked as a progressive tax. The Reagan administration was, of course, committed to reducing the tax burden on the wealthy, and it is therefore not surprising that it would use the antitrust laws aggressively to reduce collusion in public-sector procurement. One may disapprove of the Reagan administration's use of the antitrust laws in these ways, but that is very different than claiming that the administration declined to enforce the antitrust laws.

A similar story about the Chicago School's influence on antitrust enforcement being conditioned by its background assumptions about the state and private markets shows up in the AT&T divestiture case. How did the largest antimonopoly corporate breakup in history occur at the hands of the Reagan administration and its decidedly Chicago School Justice Department?

The answer lies in the conviction of assistant attorney general Bill Baxter that AT&T was exploiting its status as a regulated monopolist to stifle competition.Footnote 38 What has come to be known as “Baxter's law” posits that rate-regulated monopolists may extract monopoly profits from vertically integrated markets without running afoul of the “one monopoly profit” theorem.Footnote 39 Suspecting government regulation as the deep source of AT&T's persistent monopolistic behavior, the conservative Reagan administration was willing to break it up. As in the cartel cases, the Chicago School viewed antitrust as an appropriate vehicle for liberating private markets from distortions created by government regulation or preventing private-market actors from exploiting governmental processes.

An additional area in which Chicago School ideology implies aggressive use of antitrust law concerns the potential for federal antitrust law to preempt anticompetitive state or local regulations. Use of federal law to override state economic regulation has been a priority of the political right since the Lochner era, when the Supreme Court employed substantive due process doctrines under the Fourteenth Amendment to invalidate state economic regulations perceived to intrude on the freedom of contract. Following the New Deal shift in the Supreme Court from about 1937 forward, the court repudiated this use of the federal Constitution and largely left the states free to regulate economically so long as they did not infringe minority rights or violate other provisions of the Constitution, such as the First Amendment. In 1943, in Parker v. Brown, the court extended its post-Lochner jurisprudence, holding the Sherman Act inapplicable to anticompetitive structures created by state regulation.Footnote 40 Just as the post-1937 constitutional dispensation would avoid second-guessing state regulatory judgments in favor of judicially preferred economic theories, so too the courts would reject efforts to use the Sherman Act to the same effect.

The Parker doctrine remains in effect today, albeit with significant modifications that allow some limited uses of federal antitrust law to preempt anticompetitive state regulations. In the push-and-pull over the doctrine's boundaries, it has largely been advocates of the Chicago School's consumer welfare approach that have argued for narrowing state-action immunity on the view that states systematically distort competitive processes for the benefit of rent-seekers.Footnote 41 This use of federal antitrust law as a deregulatory device is consistent with the Chicago School's broader perspective that markets tend to function well when left to their own devices and that distortions occur primarily as the result of governmental intrusion. As of this writing, there are signs that the Trump FTC is looking again at state-action questions, with a possible eye to reinvigorating FTC initiatives against anticompetitive state regulations. This may be a quite different use of antitrust law than as a device to check purely private market power, but it points again to the fact that the Chicago School is not synonymous with abdication of antitrust enforcement. Chicago had uses for antitrust.

Chicago's Legacy

The Chicago School undoubtedly moved antitrust in an anti-interventionist direction, both by curtailing the use of enforcement against dominant firms and by redeploying antitrust against the states as a deregulatory tool. But the Chicago School did not “kill” antitrust; if anything, the Chicago revolution solidified antitrust's position in the bipartisan mainstream of market regulation by growing and entrenching a professional class of lawyers, economists, and civil servants committed to simultaneously limiting antitrust's reach and ensuring its survival.

Writing a decade before the rise of the Chicago School, Richard Hofstadter described the antitrust movement as having gone underground into technocracy: “Antitrust has become almost exclusively the concern of small groups of legal and economic specialists, who carry on their work without widespread public interest or support.” Hofstadter found that antitrust had “ceas[ed] to be largely an ideology and [had become] largely a technique” administered by “a small group of influential and deeply concerned specialists” in “differentiated, specialized, and bureaucratized” administrative institutions.Footnote 42 What Hofstadter described pre-Chicago was amplified by Chicago. Because of Chicago's relentless focus on technical economics as the exclusive touchstone of antitrust analysis, antitrust became an ever more specialized and highly technical practice area. The number of professional economists working in the Justice Department's Antitrust Division and the FTC grew exponentially, as did the corresponding private-sector economic consulting firms providing support to antitrust litigants. Antitrust enforcement became a specialized practice area at large law firms in New York and Washington, with top practitioners moving through revolving doors from private practice to top government positions and then back again to the private sector. The American Bar Association Antitrust Section's annual spring meeting grew from a gathering of a few hundred lawyers to a sprawling event for over three thousand practitioners, government bureaucrats, economists, and other professionals heavily invested in the antitrust enterprise.

Antitrust's growing professional class needed to be fed; if more permissive legal norms cultivated by the Chicago School in the 1970s and 1980s as to mergers and monopolies meant less vigorous enforcement in those areas, enforcement would shift in different directions. One growth area was criminal enforcement against price-fixing cartels. From the 1960s to the 2000s, the number of anticartel cases brought by the Justice Department and the fines and prison sentences imposed grew exponentially.Footnote 43 For the first time in the history of U.S. antitrust enforcement, senior corporate executives involved in price-fixing behavior faced the genuine threat of hard prison time, and corporate fines soared into the billions.

In other enforcement areas, the Chicago revolution did not so much kill the enterprise as trim and then stabilize it. Figure 1, which is drawn from data collected by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, shows the trend line in private antitrust filings in federal court from the 1960s to the present. Consistent with the overall postwar boom in private litigation, private antitrust filings took off in the 1960s and ’70s before being brought down to earth by procedural and substantive antitrust reforms favoring defendants (many of which were motivated by the Chicago School critique of excessive civil litigation).Footnote 44 Still, when private enforcement levels settled at their new equilibrium in the 1980s, the number of filed cases far exceeded the numbers from the period before the run-up in the late 1960s. From a statistical perspective, the Chicago School influence may be seen as the correction of a fairly recent trend (the 1960s/1970s run-up) and the entrenchment of a stable “new normal” that still involved the filing of hundreds of new private cases a year.

Figure 1. Private antitrust cases by five-year period. (Source: Administrative Office of United States Courts, Statistics and Reports on Business of the Federal Judiciary.)

Although the Chicago School certainly cut back on the rising tide of antitrust enforcement in the postwar period, its long-run effect was anything but the elimination of antitrust as an enterprise. Rather, by furthering the growth of antitrust's professional class and institutionalizing the role of economic analysis, the Chicago School reinforced antitrust as a durable feature of the American political, legal, and regulatory landscape. Whether or not antitrust is currently sufficiently vigorous to safeguard the competitiveness of the American economy (a question currently under debate), an entrenched and professionalized set of antitrust institutions is available on a turnkey basis to any rising political or ideological movement wishing to take enforcement in a new direction.

Antitrust after Chicago

So what happens next? It seems more likely that what succeeds Chicago is some version of post-Chicago rather than a resurgence of either Brandeisianism or structuralism. Despite the mounting populist and even self-identified Brandeisian pressures to reform antitrust, the abandonment of consumer welfare as the primary standard and of technical economic analysis as a necessary building block seems remote. Given the political polarization in Washington and the fact that pressures for antitrust reform are not concentrated in either of the major political parties but instead spread divisively through both, the prospect of landmark legislative reforms seems low. The populist pressures are almost all external to the antitrust establishment, which, from right to left, has largely circled the wagons around consumer welfare. Without some significant faction of antitrust professionals (lawyers and economists) leading the charge in a Brandeisian direction, it seems unlikely that the inherently conservative courts will abandon the consumer welfare model and economic reasoning in the foreseeable future.

That said, the time seems ripe for post-Chicago to make significant inroads along a number of fronts, if for no better reason than as a sop to the “barbarians at the gate.” Empirical and theoretical work has been challenging many Chicago School claims for some time, and the rising generation of antitrust economists and lawyers is being schooled in a more interventionist literature.Footnote 45 The Justice Department's challenge to the AT&T/Time Warner merger signaled a potential revival in vertical-merger enforcement but resulted in a resounding defeat for the Antitrust Division.Footnote 46 Nonetheless, given the political climate, expect a growing number of similar challenges from both public and private enforcers in other key areas of antitrust policy, including horizontal mergers, predatory pricing, tying and bundling, dominant technology platforms, price squeezes, and labor monopsonization.

Further, expect to see Chicago's continuing influence even after it is replaced. This may occur not only in obvious ways, like the continuation of the consumer welfare model and technical economic reasoning, but also in subtler ways, such as with a continued focus on the state as a primary source of market distortions. It bears remembering that antitrust enforcement has not coded easily in left/right political terms historically but has arisen from, and in opposition to, a diverse set of sometimes conflicted political impulses.Footnote 47 Once we move past the caricature of Chicago as unadorned laissez-faire and understand it as a set of conflicted ideological commitments that have manifested periodically over time, a more realistic view about its rise to dominance, eventual replacement, and continued influence appears.