1. Introduction

According to van Os (Reference Os1989:2), intensification is a “funktional-semantische Kategorie der Verstärkung und der Abschwächung intensivierbarer sprachlicher Ausdrücke” [functional semantic category of strengthening and weakening of intensifiable linguistic expressions]. In line with this definition, an intensifier is a device that scales a quality up or down relative to an assumed norm (Bolinger Reference Bolinger1972:17, Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985:589–590). While scholars disagree over the most appropriate terminology to use (Stoffel Reference Stoffel1901, Bolinger Reference Bolinger1972, Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985, Paradis Reference Paradis1997), intensifiers have been a topic of much linguistic research that has yielded some important findings about language variation and change (Stoffel Reference Stoffel1901, Bolinger Reference Bolinger1972, Partington Reference Partington1993, Paradis Reference Paradis1997, Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Tagliamonte & Roberts Reference Tagliamonte and Roberts2005, Xiao & Tao Reference Xiao and Tao2007, Méndez-Naya Reference Méndez-Naya2008, Fuchs Reference Fuchs2017, Stratton Reference Stratton2018). One finding is that intensifiers appear to function as elements within a multi-dimensional system, which means that the increase or decrease in the frequency of an intensifier can result in a rearrangement of the system of intensifiers as a whole (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Tagliamonte & Roberts Reference Tagliamonte and Roberts2005, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte2008). Exploring the collocational distribution of intensifiers has also provided some insight into the delexicalization process and semantic bleaching of intensifiers (Bolinger 1972, Heine 1993). From a sociolinguistic standpoint, several studies have also found that social factors, such as gender and age, can influence the use of intensifiers (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Tagliamonte & Roberts Reference Tagliamonte and Roberts2005, Macaulay Reference Macaulay2006, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte2008, Fuchs Reference Fuchs2017).

However, intensification in the German language, specifically the intensification of adjectives, is underexplored (van Os Reference Os1989:3, Breindl Reference Breindl2009:403).Footnote 1 While some studies have proposed various ways to categorize or describe German intensifiers (van Os Reference Os1989, Claudi Reference Claudi2006, Breindl Reference Breindl2009), no studies to date have carried out a synchronic exploration of how German intensifiers work together as parts within a multi-dimensional system. Furthermore, to the best of my knowledge, no studies have empirically investigated the effects of social factors such as gender and age on the use of German intensifiers. Using a subcorpus of the largest available corpus of present-day spoken German, Forschungs- und Lehrkorpus Gesprochenes Deutsch (FOLK; Research and Teaching Corpus of Spoken German), the present study bridges these empirical gaps by carrying out a comprehensive examination of German adjective intensifiers.

There are two central research questions addressed in the present study, which were formulated based on previous research. First, what does the system of German adjective intensifiers currently look like in terms of frequency and function, based on the synchronic data in FOLK? In other words, which German intensifiers are currently used most frequently, and are specific types of intensifiers (that is, amplifiers) more frequent than others (that is, downtoners)? Second, is German intensifier use sensitive to the social factors gender and age?Footnote 2 While the present study is specifically interested in the intensification of adjectives in the German language, its findings are related to the broader context of intensification in other Germanic languages. Thus, the study contributes to a better understanding of intensification crosslinguistically.

The structure of the present study is as follows. First, a summary of the terminology used to describe intensifiers is provided in section 2.1, which includes a detailed description of the taxonomy used in this study. Section 2.2 provides an overview of the most salient findings of studies on intensifiers. The methodology—that is, the corpus used, the data collection, and coding process—is then provided in section 3. The distributional analysis is provided in section 4.1, followed by the multivariate sociolinguistic analysis in section 4.2. A summary of the main findings and implications is subsequently provided in section 5.

2. Intensifiers

2.1. Describing German Intensifiers

While intensifiers can intensify a variety of parts of speech, the present study is interested in what Bäcklund (1973:279) and Androutsopoulos (Reference Androutsopoulos1998:457–458) found to be the most frequent function of the intensifier, namely, the adjective intensifier. This focus on adjective intensification (as opposed to verbal or adverbial intensification) is in line with the established practice in quantitative research on intensi-fication (D’Arcy 2015:458). Some examples from the corpus of the types of German adjective intensifiers that are of interest in the present study are provided in 1.

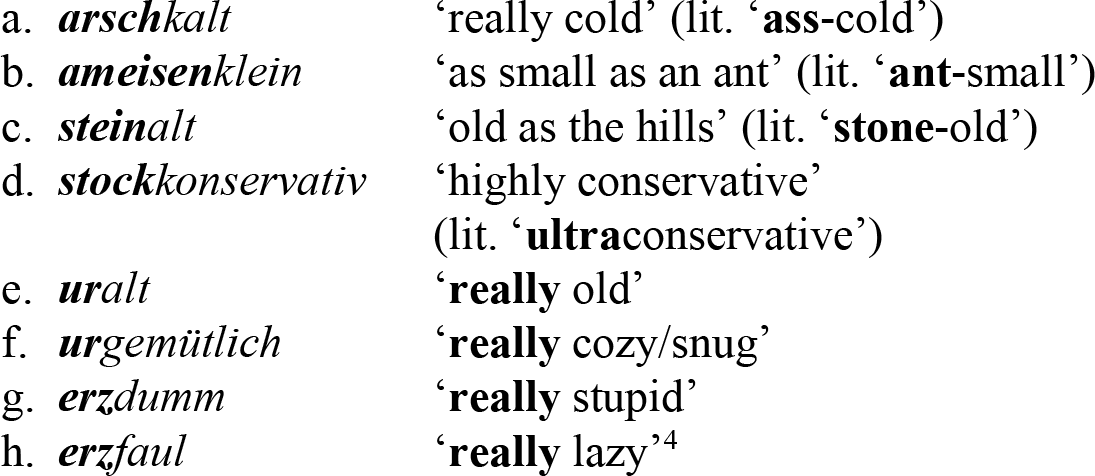

(1)

In German, adjectives can be intensified syntactically, as in 1, or through the use of morphology (Kirschbaum Reference Kirschbaum2002, Hecht Reference Hecht2002), as in 2.Footnote 3 Morphologically, this can be done through compounding, where the noun, sometimes referred to as a prefixoid, appears first and the adjective appears second, as in 2a–d. Alternatively, this can be achieved through the affixation of prefixes, sometimes referred to as booster prefixes (German Steigerungspräfixe), as in 2e–h.

(2)

It should be noted that for Erben (Reference Erben1961:107–122), terminologically speaking, morphological intensification is expressed through “Wortbildung” [word formation] and syntactic intensification is expressed through “graduierende Beiwörter” [gradable epithets]. However, for Costa (Reference Costa1997:166–176), morphological intensification refers only to prefixation, whereas compounding is considered lexical intensification. Given that morphological intensification is less frequent and less productive than syntactic intensification (Androutsopoulos Reference Androutsopoulos1998:451, Claudi Reference Claudi2006:352), morphological intensification is not considered in the present study, which focuses solely on syntactic intensification.

Despite the cornucopia of literature on English intensifiers, there is still little consensus among scholars and researchers regarding the most appropriate terminology to use. Stoffel (Reference Stoffel1901) originally referred to intensifiers as “degree adverbs,” but Bolinger (Reference Bolinger1972:18) and Paradis (Reference Paradis1997) referred to them as “degree modifiers.” Similarly, in the German tradition, intensifiers have been referred to as Gradadverbien ‘degree adverbs’ (Fettig Reference Fettig1934, König et al. Reference König, Stark and Requardt1990), Steigerungspartikeln ‘augmentation particles’ (Helbig Reference Helbig1988), Intensivpartikeln ‘intensive particles’ (Androutsopoulos 1998), Intensitätspartikeln ‘intensifying particles’ (Breindl Reference Breindl2009), Intensitätsadverbien ‘intensity adverbs’ (Weinrich 1993), and Intensivierer ‘intensifiers’ (Kirschbaum Reference Kirschbaum2002). Some other labels also include Gradpartikel ‘scalar particle’ (Altmann Reference Altmann1976), Intensifikator ‘intensifier’ (Helbig Reference Helbig1988, van Os Reference Os1989), graduativer Zusatz ‘gradable adjunct’ (von Polenz Reference Polenz1988) and Intensivierungsoperator ‘intensifying operator’ (Hecht Reference Hecht2002). Therefore, it is clear that, just as in the English literature, there is also little consensus regarding the most appropriate terminology for describing intensifiers in the German literature.

A similar lack of consensus is observed with respect to the semantic classification of intensifiers. While some attempts have been made to distinguish between the different semantic functions of intensifiers (Helbig 1988:48), classifications are not always consistent (Bolinger Reference Bolinger1972, Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985, Weydt & Ehlers Reference Weydt and Ehlers1987, van Os Reference Os1989, Paradis Reference Paradis1997). For instance, Helbig (Reference Helbig1988:48) divides intensifiers into starke Intensivierer ‘strong intensifiers’ (such as sehr ‘very’, höchst ‘highly’, and absolut ‘absolutely’) and schwache Intensivierer ‘weak intensifiers’ (such as ziemlich ‘quite’, recht ‘right’, and etwas ‘somewhat’). While Weydt & Ehlers (Reference Weydt and Ehlers1987) also divide intensifiers into two groups, their groups are different, namely, Gradadverbien ‘degree adverbs’ and Fokuspartikeln ‘focus particles’. In contrast, according to the degree of intensity, Biedermann (Reference Biedermann1969:96) divides intensifiers into five categories, Sommerfeldt (1987) into six, and van Os (Reference Os1989) into eight. More recently, Claudi (2006) categorized intensifiers according to their “source semantics” (p. 350) as opposed to a scale/degree-based model, which can be problematic given that intensification is acknowledged to be a scalar concept. All in all, this lack of consensus suggests a complex and nonuniform picture of intensification in the German language.

In the present study, German intensifiers are described using the terminology of Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985), given that their scale-based taxonomy has become widespread in the literature on intensifiers (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Tagliamonte & Roberts Reference Tagliamonte and Roberts2005, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte2008, Broekhuis Reference Broekhuis2013, Stratton Reference Stratton2018). This approach makes the present study comparable to studies on intensifiers crosslinguistically as it provides a common denominator according to which adjective intensification can be compared. According to Quirk et al.’s (1985) taxonomy, intensifiers are subdivided into amplifiers (German Verstärker) and downtoners (German Begriffsminderung).Footnote 5 Amplifiers “scale upwards from an assumed norm,” as in es ist sehr warm ‘it is very warm’, and downtoners scale “downwards from an assumed norm,” as in es ist ein bisschen warm ‘it is a little bit warm’. Amplifiers are then subdivided into maximizers and boosters according to the scale of amplification. Maximizers “denote the upper extreme point on the scale,” as in es war extrem heiß ‘it was extremely hot’ and boosters “denote a high degree, a high point on the scale,” as in das war echt cool ‘that was real(ly) cool’. Depending on their “lowering effect”, downtoners are further subdivided into four groups: approximators, compromisers, diminishers, and minimizers. Approximators “serve to express an approximation,” as in ich bin fast sicher ‘I am almost certain’; compromisers “have only a slight lowering effect,” as in es ist ziemlich warm ‘it is quite warm’; diminishers “scale downwards and roughly mean ‘to a small extent’,” as in das Buch war etwas interessant ‘the book was somewhat interesting’, and minimizers are “negative maximizers” with the almost equivalence of “(not) to any extent’,” as in er ist kaum zufrieden ‘he is hardly pleased’.Footnote 6 In work on English intensifiers, amplifiers were found to be more frequent than downtoners, and boosters were found to be more frequent than maximizers (Mustanoja Reference Mustanoja1960:316, Peters Reference Peters1994:271, D’Arcy 2015:460).

Given that amplifiers are functionally different from downtoners, and maximizers are functionally different from boosters, in a variationist sociolinguistic analysis, dividing intensifiers according to the scale-based taxonomy of Quirk et al. (1985:590) is in keeping with the principles of defining the envelope of variation. Under this approach, the study identifies factors that shape the choice of one variant over another functionally equivalent variant, which are in direct competition. This approach is necessary because not all intensifiers are in direct competition with each other in the variationist sense (for instance, a downtoner would not be in direct competition with an amplifier).

2.2. Previous Research

As Tagliamonte (Reference Tagliamonte2012:230) puts it, intensifiers are “an ideal choice for the study of linguistic variation change” because of (1) their “versatility and color (note the sheer number of different forms); (2) the capacity for rapid change; and (3) recycling of different forms.” It has been argued that some of the reasons for their constant fluctuation in frequency are “speaker’s desire to be original, to demonstrate their verbal skills, and to capture the attention of their audience” (Peters Reference Peters1994:271).

Because multiple studies on English have found a correlation between gender and intensifier use, indicating the tendency for female speakers to use intensifiers more often than male speakers (Tagliamonte & Roberts Reference Tagliamonte and Roberts2005, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte2008, Murphy Reference Murphy2010, Fuchs Reference Fuchs2017), it is pertinent to investigate whether this correlation can also be observed in German. Using a binary mixed effects logistic regression model, Fuchs (Reference Fuchs2017) analyzed 111 British English intensifiers and found that female speakers were more likely to use adjective intensifiers than male speakers.Footnote 7 However, to make this broad claim about female speakers in general, crosslinguistic evidence is required.

Several studies have also found that the age of the speaker can have a statistically significant effect on the frequency of intensifiers (Bauer & Bauer Reference Bauer and Bauer2002, Xiao & Tao Reference Xiao and Tao2007). While some German intensifiers (such as voll ‘real(ly)’) are considered to be more frequent in Jugendsprache ‘youth language’ (Androutsopoulos Reference Androutsopoulos1998, Kirschbaum Reference Kirschbaum2002, Breindl Reference Breindl2009), the extent to which this is empirically true today is also of interest in the present study. The closest empirical analysis of German intensifiers to date was part of Androutsopoulos’ (1998) monograph, which studied the speech of adolescents. However, as well as being two decades old, his study is also methodologically different from the present study, which is discussed in sections 3 and 4.

Another reason why intensifiers have received much attention is their tendency to undergo a process of delexicalization (Sinclair Reference Sinclair1992, Partington Reference Partington1993). According to Partington (Reference Partington1993:183), delexical-ization refers to “the reduction of the independent lexical content of a word, or group of words, so that it comes to fulfill a particular function.” Intensifiers can start out as lexical items that have semantic content, but through their delexicalization can become bleached semantically to such an extent that they no longer express their original meaning (German Verblassung der Bedeutung).Footnote 8 A commonly cited example is the development of the intensifier very in the history of the English language (Bolinger Reference Bolinger1972:18, Peters Reference Peters1994:270, Méndez-Naya Reference Méndez-Naya2003:75). Although very has its roots in the Latin adjective vērus ‘true’, it came to English via Anglo-Norman: It was first borrowed into Middle English in the 13th century as the Anglo-Norman adjective verray that meant ‘real’ or ‘true’. However, as a result of its delexicalization, the original meaning was bleached and now it is used only as an intensifier. Its former lexical meaning exists only in retentions such as to verify.

An example from the history of the German language is sehr ‘very’, as in der Film war sehr gut ‘the film was very good’. In Old High German (ca. 750–1050 CE), sêr (Proto-Germanic +sairo, +sairaz) was both an adjective that meant verwundet ‘wounded’ or schmerzvoll ‘painful’ and a noun that meant ‘pain’. By Middle High German (ca. 1050–1350 CE) these gave rise to the adverbial sêre that meant schmerzlich ‘painfully’; later it became the intensifier sehr, which is used today. Fritz (Reference Fritz1998) suggests that sehr became an intensifier due to high frequency collocations such as sêre wunt ‘painfully wounded’.Footnote 9 Regardless of the reason, its original denotation of pain and injury has been bleached semantically. Today, sehr is defined as in hohem Maße ‘to a high degree’ (Duden, sehr) and, for the most part, no longer represents its original meaning of schmerzlich ‘painfully’. However, as with the retention of verify, the original meaning of pain still lives on in the German verb versehren ‘to injure’. Interestingly, the cognate sore in English was also used as an intensifier in Old English (ca. 450–1100 CE) and Middle English (ca. 1150–1500), as in sore corrupte ‘very corrupt’ and sore syk ‘very sick’ (OED, sore adj.). In languages such as Dutch and Icelandic, the original meaning is still retained, as in het doet zeer ‘it does pain’ (Dutch) and ég er mjög sár ‘I am very hurt’ (Icelandic; see the Icelandic noun sársauki ‘pain’). The adjective sore in English, as in my arm is sore, still retains this original meaning of pain or injury. This adjective also appears to be the origin of the semantically bleached expression I am sorry in English (lit. ‘I am in pain [sore]’; see German es tut mir Leid lit. ‘it does me pain’).Footnote 10

Semantic bleaching can also strip away any historically positive or negative semantic prosody of a lexical item.Footnote 11 An example is the development of furchtbar ‘terrible’, which originally was used to describe objects that provoked fear and shock (Karpova 2014:175). Throughout time, this use “nearly disappeared” in attributive position, and furchtbar became an adjective intensifier, as in ein furchtbar teueres Auto ‘a terribly expensive car” (ibid). Then in its function as an intensifier furchtbar underwent further semantic bleaching, losing its initial negative denotation, so that now it can modify adjectival heads with positive semantic prosody, as in furchtbar froh sein ‘to be very happy’ (ibid).

Multiple crosslinguistic examples can be observed. For instance, a similar diachronic development took place in the case of English terrible and terrific (Núñez Pertejo Reference Núñez-Pertejo2017), and in the case of Danish frygteligt ‘terrible’.Footnote 12 Another example is arg (Old High German ark, Proto-Germanic +arg-az), which originally only meant ‘bad’, as in ein arger Sünder ‘a bad sinner’ (see Ärger ‘trouble’) but later became an intensifier of adjectives, going from an adjective with negative semantic prosody to a delexicalized bleached adverbial form (Kirschbaum Reference Kirschbaum2002:182). Based on the present dataset, arg can now be used to intensify adjectives with either positive or negative semantic prosody, as in sie ist arg schön ‘she is very beautiful’ or das finde ich arg traurig ‘I find that very sad’. Its cognate erg in Dutch was also originally used only as an adjective meaning ‘bad’, but it too became an intensifier of adjectives (Donaldson Reference Donaldson2017:137), which indicates that +arg-az developed along a similar path in both languages.

3. Methodology: The Corpus, Data Collection, and Coding

FOLK was accessed via Datenbank für gesprochenes Deutsch (DGD; Database for Spoken German).Footnote 13 As Fandrych et al. (2012) point out, FOLK is the most frequently used subcorpus in the DGD and prior to its compilation, few German spoken corpora had been made available to the scientific community (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2016:397). Because FOLK is essentially a monitor corpus, the total number of words has increased over the last few years. The present study took a random sample of 5,000 adjectives from the 2016 dataset, which contained 219 spontaneous spoken interactions, amounting to approximately 1.6 million words (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2016:117).Footnote 14 To collect the data, speakers across Germany from diverse backgrounds (reasonably stratified for gender and age) were recorded in a variety of spoken interactions. The audio files were then transcribed orthographically. The interactions consisted of everyday conversations, such as conversations over coffee, among friends, family, and couples, while doing housework or playing games. Some others include interactions in schools and universities, such as conversations in the classroom, during meetings, and among colleagues, as well as interactions with various service providers, such as hairdressers. In this respect, FOLK is a suitable resource for analyzing the use of German intensifiers as it contains a collection of naturally-occurring authentic language. FOLK provides metadata such as the gender and age of the speaker, which was essential for the sociolinguistic component of the present study.

A foundational concept in variationist sociolinguistics is the Principle of Accountability, which is crucial to any quantitative analysis of linguistic variation (Labov Reference Labov1966:49, 1969:737–738, 1972:72). This principle requires that all relevant forms are included in the analysis as opposed to only the ones that are of interest. Methodologically, this principle has been referred to as “circumscribing the variable context” (Poplack & Tagliamonte Reference Poplack and Tagliamonte1989:60). With regard to German adjective intensifiers, the procedure involves counting not only the instances where adjectival heads were intensified (such as er ist sehr gut ‘he is very good’), but also instances, where the heads could have been intensified but were not (such as er ist ∅ gut ‘he is good’). In other words, this methodological approach takes into consideration the “zeros” (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003:263). In this respect, the present study is comparable to previous studies. This approach makes the present study replicable, and it also allows one to objectively examine the effects of social factors on the use of intensifiers: Given that their use is optional, by considering both the presence and the absence of intensifiers it is possible to conduct a quantitative analysis and to establish the overall intensification rate (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003).Footnote 15

As mentioned above, a random sample of 5,000 adjectives was extracted from the corpus using the appropriate POS (Part of Speech) tagging.Footnote 16 The data were saved as a virtual corpus, which was then manually inspected to eliminate any erroneous data (that is, false positives). By looking to the left of the adjectives one can establish whether they had been intensified by an intensifier or not. The present study was only interested in the premodification of adjectives as opposed to the postmodification, the latter being infrequent in German.Footnote 17 Following Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003:264, contexts that do not permit or block intensification (such as negative, comparative, and superlative contexts) were omitted.Footnote 18 Furthermore, “focusing subjuncts”, such as sogar ‘even’ (Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985:604), were also omitted from the present dataset, as well as constructions such as so [klein] wie… ‘as [small] as…’. In order to carry out the sociolinguistic component of the study, utterances that came from speakers with missing metadata, such as gender and age, were also omitted.

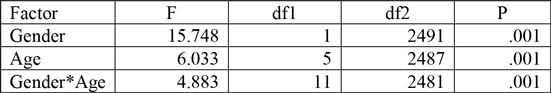

Following Fuchs 2017, for the sociolinguistic analysis (that is, the second research question) a mixed effects logistic regression model was run using IBM SPSS 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). This statistical model was carried out to test the individual effects of the factors gender and age as well as their interaction effects on the binary dependent variable measured in terms of occurrence or absence. Accordingly, the model calculated whether these social factors influence the linguistic choice of using versus omitting intensifiers with adjectives. Adjectives were abstracted and coded based on whether they were intensified or not; this method of coding made the use of the logistic regression model possible. Had one simply searched only for instances of adjective intensification, the logistic regression model would not have worked, because there would have been a nondichotomous dependent variable—that is, there would have been instances of occurrence, but no instances of absence. Such an approach would have also violated the principle of accountability.

Each adjective entry was coded according to the sociolinguistic metadata provided. The factor gender had two levels: [female] and [male], and the factor age had six levels: [0–14], [15–24], [25–34], [35–44], [45–59], and [60+]. To account for idiosyncratic speech patterns of individual speakers, speaker was included as a mixed effect (or random factor). This allows the statistical model to account for any highly frequent intensifier use in the speech of a particular speaker, which may have otherwise skewed the data. Barth & Kapatsinski (Reference Barth and Kapatsinski2018:101) point out in this respect:

[O]ne of the main challenges of corpus data is that the data are not nicely balanced … unless special care is taken, more talkative (or popular) speakers will contribute more to the database than less talkative (or less popular) ones.

While traditionally, regression models only used fixed effects, regression models that include mixed effects have now become the standard in quantitative research in variationist sociolinguistics (Johnson Reference Johnson2009, Tagliamonte & Baayen Reference Tagliamonte and Baayen2012, Fuchs Reference Fuchs2017, Barth & Kapatsinski Reference Barth and Kapatsinski2018).

4. Results

This section is divided into two parts. Section 4.1 deals with the frequency and distribution of German intensifiers (research question one). Section 4.2 presents and discusses the findings of the sociolinguistic analysis (research question two).

4.1. The Distributional Analysis

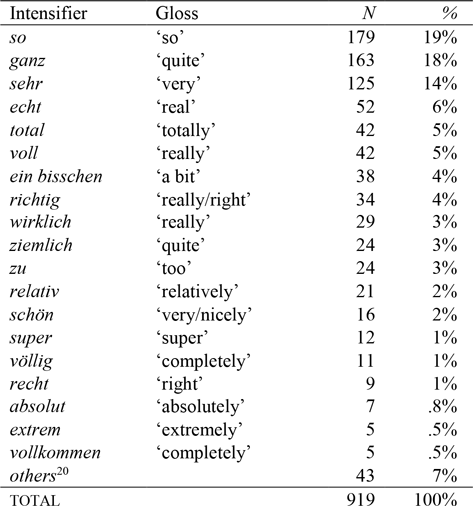

Of the 5,000 adjectives, 2,507 were omitted for reasons explained in section 3. What remained were 2,493 tokens of intensifiable adjectives (produced by 294 speakers), of which 919 were intensified (produced by 227 speakers). This means that the overall intensification rate of adjectives is 37% (see table 1), which, while on the high end, is consistent with what has been observed in English (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte2008, 2016).Footnote 19 The 919 intensified adjectives were intensified by 45 adjective intensifiers (see table 2). As is indicated in table 2, the most frequently used intensifiers were so ‘so’, ganz ‘quite’, sehr ‘very’, echt ‘real(ly)’, total ‘totally’, and voll ‘really’.

Table 1. The overall distribution of intensification (total N=2,493).

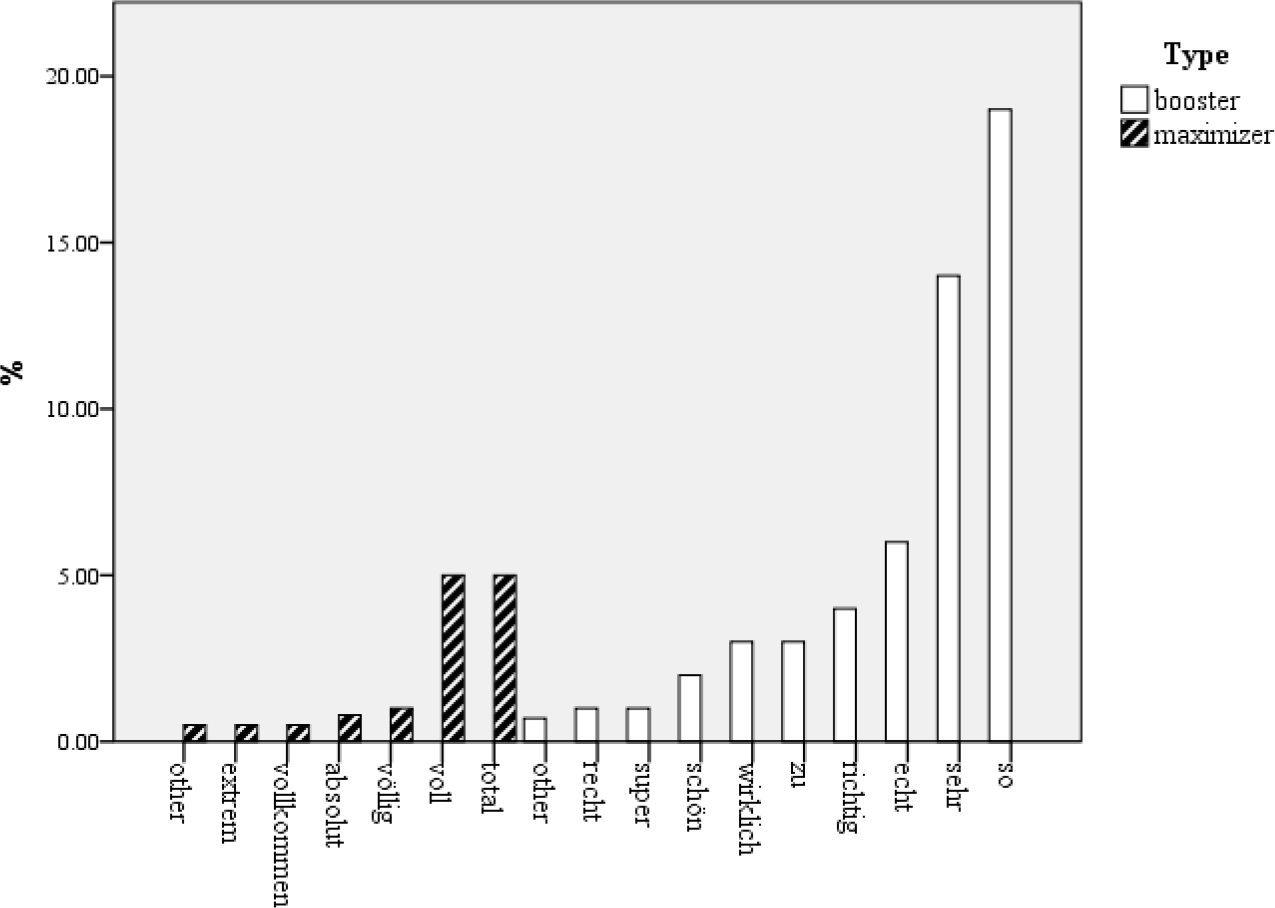

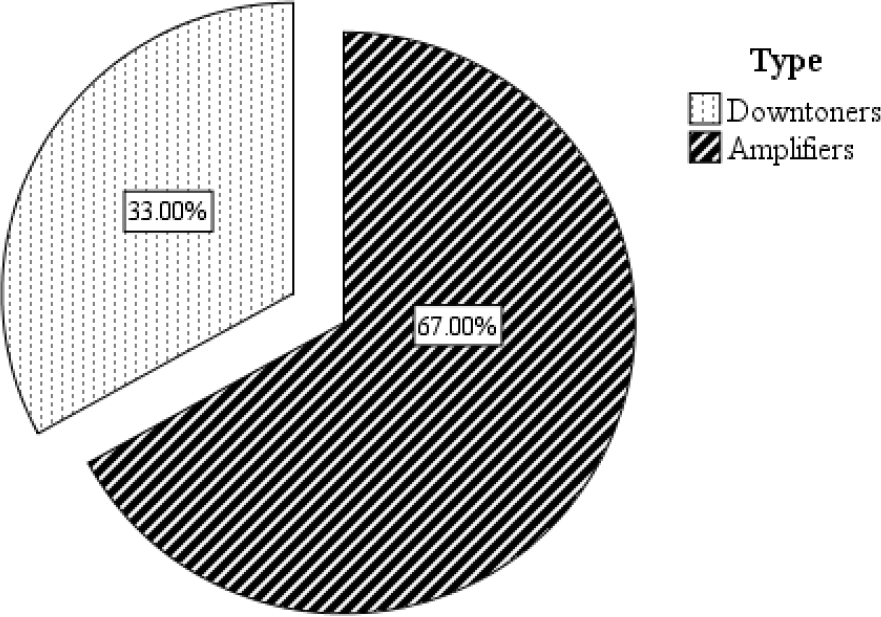

While table 2 provides a useful overall frequency of the adjective intensifiers, the latter are also divided into boosters versus maximizers (figure 1), and amplifiers versus downtoners (figure 2), according to the taxonomy of Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985:590). This semantic division reflects the different semantic functions of intensifiers.

Figure 1. Frequency: Boosters versus maximizers.Footnote 21

Figure 2. Frequency: Amplifiers versus downtoners.Footnote 22

Table 2. The frequency of German adjective intensifiers.

The data show that German boosters are more frequent than German maximizers and that German amplifiers are more frequent than German downtoners. The most frequently used boosters in the dataset were so ‘so’, sehr ‘very’, and echt ‘real(ly)’. Some examples of these three German boosters from the present dataset are reported in 3.

(3)

A question worth asking is why some intensifiers are more frequent than their functionally equivalent counterparts. While there are several factors that undoubtedly influence frequency both synchronically and diachronically, in an attempt to answer this question from a synchronic perspective, it is useful to examine the adjectival heads that are being intensified. Accordingly, Type-Token Ratio (TTR) was calculated. TTR relates the unique number of different adjectives (types) to the total number of adjectives intensified (tokens), which indicates how widely an intensifier collocates. This calculation indicated that the most frequently used boosters had a TTR between 63%–65%. For instance, the booster so intensified 179 adjectives, of which 117 were unique, resulting in a TTR of 65% (117 types/179 tokens). Most of the adjectival heads intensified by so were unique, which means that so modifies a wide range of different adjectives. However, adjectives such as geil ‘cool’ (das ist so geil ‘that is so cool’), groß ‘big’ (…dass so groß ist ‘…that is so big’), and krass ‘cool’ (die Nase ist so krass ‘the nose is so cool’) were intensified by so multiple times. For example, the adjective groß was intensified nine times, which, one the one hand, may suggest that so groß as a collocation is frequent, but on the other hand, may simply reflect the high frequency of the adjective groß. Furthermore, the booster sehr intensified 85 different adjectives out of a total of 125, resulting in a TTR of 68% (85 types/125 tokens). Just like so, sehr also intensified a range of different adjectives, but gut ‘good’ was intensified 24 times. Similar results were observed with echt, which had a TTR of 65%. Yet one cannot simply attribute high frequency to a high TTR since many less frequently used boosters, such as wirklich ‘really’ and richtig ‘real(ly)’, had an even higher TTR.

As for the maximizers, total ‘totally’ and voll ‘full(y)’ were the most frequently used (assuming, of course, that they still have a maximizing function; if not, völlig ‘completely’ ranks first place). The maximizer voll belongs to what Kirschbaum (2002:129) refers to as the Intensität als Vollständigkeit ‘completeness intensity’ group of intensifiers, which also includes vollkommen, völlig, and komplett since they can all be loosely translated as ‘completely’. Why voll is used more frequently than vollkommen, völlig, or komplett is not entirely clear, but the fact that it is monosyllabic, and the others are not, may play a role. Another possible explanation is that voll is now used as a booster, and as is clear from the data, boosters are more frequent than maximizers. Furthermore, völlig and vollkommen may also belong to a formal register, which is not represented in the corpus. Even the adjectives that were intensified by these two maximizers in the dataset appear to be somewhat register-specific (for example, vollkommen robust ‘completely robust’). The maximizer voll had a TTR of 78% (36 types/42 tokens), which indicates that it, too, collocates widely.Footnote 23 As table 2 indicates, other maximizers, such as extrem ‘extremely’ and absolut ‘absolutely’, were not used frequently.

The fact that amplifiers were found to be more frequent than downtoners is interesting, given that similar results were found in English (Peters Reference Peters1994:271, D’Arcy 2015:460), but no studies have drawn a quantitative parallel between the two languages. Taken together, the results from English and German may suggest that scaling up the meaning of an adjective is more frequent than scaling it down. Furthermore, the finding that German boosters are more frequent than German maximizers also corroborates findings on English. Also intriguing is the fact that the three most frequently used boosters, so ‘so’, sehr ‘very’, and echt ‘real(ly)’, are also the most frequently used boosters in English (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003:266, Tagliamonte & Roberts Reference Tagliamonte and Roberts2005, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte2008, Stratton Reference Stratton2018).Footnote 24

It is possible that there is something inherent in the semantics of these intensifiers that makes them so frequent. For instance, it seems that adjectives that denote qualities associated with truth and reality have a tendency to become intensifiers (Bolinger Reference Bolinger1972, Swan Reference Swan1991:418). This is clearly the case with really and very in English, and echt ‘real(ly), wirklich ‘really’, and richtig ‘real’ in German. It is expected that lexical items expressing truth or correctness would become adjective intensifiers through grammaticalization: Speakers feel that qualifying their statements using words with such meaning would provide validity to what they are saying. This observation seems to hold true crosslinguistically. For instance, Dutch has the adjective intensi-fiers echt ‘real(ly) and werkelijk ‘really’; Norwegian has virkelig ‘really’, ekte ‘real(ly)’, sannelig ‘truly’ (from the adjective sann ‘true’, cognate of Old English soðe ‘truly’ and forsoð ‘forsooth’), rettelig ‘right(ly)’ (from the adjective rett ‘right’), and riktig ‘right(ly)’. Swedish has verkligen ‘real(ly)’, Afrikaans has werklik ‘really’, regtig ‘really’, and rêrig ‘truly’, and Icelandic has verulega ‘really’ (raunverulegar ‘real’) and sannarlega ‘really’ (from the noun sannur ‘truth’). The use of echt as an adjective intensifier appears to be a recent development in German; according to the corpus data, it has become the third most frequently used amplifier (more specifically, booster).

In analyzing the collocational distribution of intensifiers, one can also observe crosslinguistic similarities. For instance, of the 16 adjectival heads intensified by schön ‘very’ lit. ‘nicely’, 10 (or 63%) denoted positive semantic prosody (as in sind schön süß ‘are very sweet’) and 6 (or 37%) had negative semantic prosody (as in schön traurig die ersten zwei Tage hier ‘very sad the first two days here’). On reflection, it appears that a similar development has taken place in the case of English pretty (Old English prættig), which was once only used as an adjective, but now is used as an adjective intensifier, as in the film was pretty good. Stoffel (Reference Stoffel1901:147–153) showed that the intensifier pretty came from the adjective pretty, a development, which, as the present study shows, is mirrored by the development of schön in German. The same is true with respect to the Dutch intensifier knap ‘pretty’, which originally was an adjective meaning ‘pretty/beautiful’, as in een knappe vrouw ‘a pretty woman’, and which now can be used as an adjective intensifier, as in het is knap moeilijk ‘it is pretty difficult’.

So why are amplifiers used more frequently than downtoners? On the surface, one might hypothesize that English and German speakers prefer to amplify the quality denoted by an adjective because they are optimistic; that is, they wish to make the adjective semantically more positive. However, speakers can also amplify the meaning of adjectives with negative semantic prosody, as in der Film war sehr interessant ‘the film was very interesting’ versus der Film war sehr langweilig ‘the film was very boring’. Note that in these examples, it is the adjective that determines the positivity or negativity of the description (or proposition), not the intensifier. Therefore, to answer the question of why amplifiers are more frequent than downtoners, it would seem logical to examine the semantic prosody of the intensified adjectives. However, one still fails to arrive at an answer: The most frequently intensified adjective in the dataset was gut ‘good’, which occurred 66 times. On 69% of the occasions it was intensified by amplifiers, and 31% of the time by downtoners. Note that this tendency is observed not only in adjectives with positive semantic prosody, but also in adjectives with negative semantic prosody. For instance, the adjective schlecht ‘bad’ was intensified only six times, but always by amplifiers (as in du bist echt schlecht ‘you are real(ly) bad’) and never by downtoners. Thus, the question of why amplifiers are more frequent than downtoners is simply too intricate to answer in this study. It is possible that certain adjectives have preferences for the types of intensifiers with which they collocate. For instance, a recent study found that adjectives denoting properties associated with fear are mostly amplified, whereas adjectives denoting properties associated with disgust have a tendency to be downtoned (Strohm & Klinger 2018).

4.2. Sociolinguistic Analysis

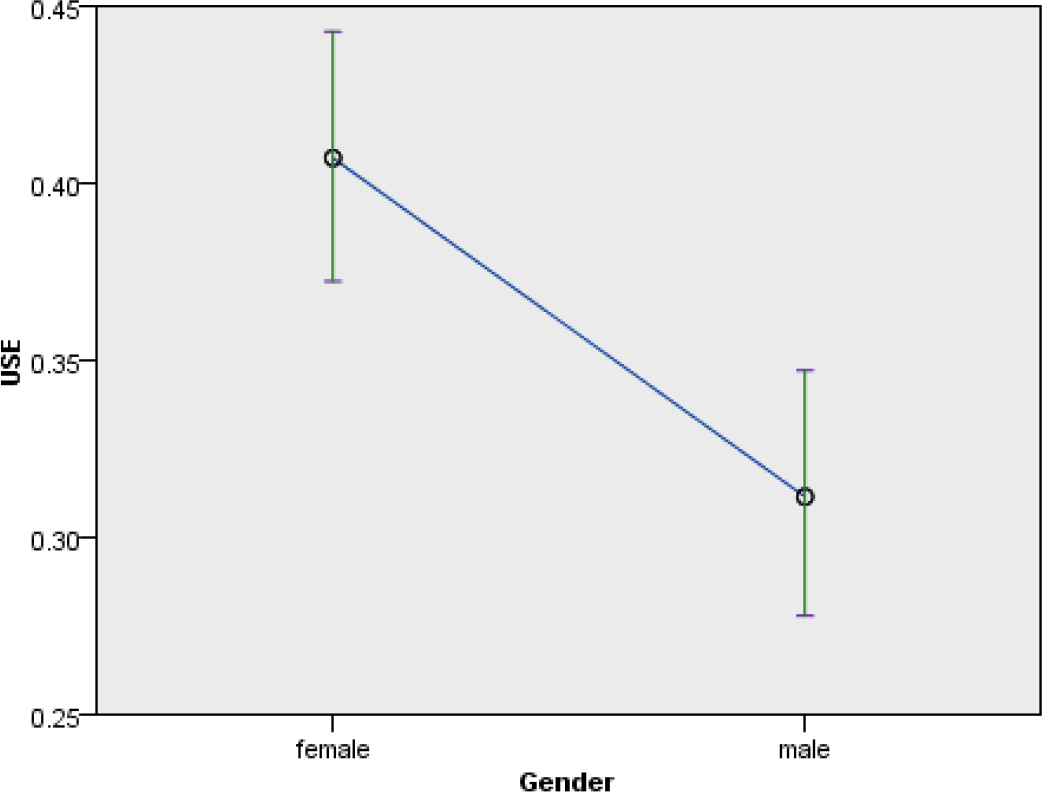

Regarding the use of specific intensifiers, descriptively speaking, female speakers used the adjective intensifier echt 13.5% more frequently than male speakers; the intensifier total 10% more frequently than male speakers and the intensifiers voll and so 7% more frequently than male speakers. As for adjective intensification in general, the binary mixed effects logistic regression model indicated that female speakers intensified adjectives more frequently than male speakers, at a p-value of .001, which is highly significant (see table 3). A graphical representation of these results is provided in figure 3. This finding thus empirically supports the claim that female speakers use intensifiers more frequently than male speakers, at least with respect to German, which corroborates findings from English (Fuchs 2017).

Figure 3. Syntactic intensification of adjectives by gender.

Table 3. Results of the mixed effects logistic regression model.

While previous research has found female speakers to be the primary users of intensification, most discussions focus solely on amplification (see, for instance, Stoffel Reference Stoffel1901:101, Jespersen Reference Jespersen1922:250). However, D’Arcy (2015:464–465) in her study on English found that although female speakers use intensifiers more frequently than male speakers, male speakers are more likely to use downtoners than female speakers. The present study found this to be true in German too, with 33% of the male sample (that is, 36 of the total 108 male speakers) using downtoners and only 18% of the female sample (that is, 33 of the total 186 female speakers) using downtoners. A Log-Likelihood test indicated that this difference is statistically significant.Footnote 25 This does not mean that female speakers prefer to amplify adjectives, whereas male speakers prefer to downtone them—this cannot be true given that 67% of all intensifiers in the dataset were amplifiers (see figure 2); however, it does mean that when an amplifier is used, the probability of it being uttered by a female speaker is significantly higher than the probability of it being uttered by a male speaker. By the same token, when a downtoner is used, the probability that it came from a male speaker is significantly higher than the probability that it came from a female speaker. From an anthropological and sociological (sociolinguistic) perspective, this contrast suggests that being male or female in modern society may have linguistic implications. When intensifying an adjective, female speakers prefer to amplify its meaning, that is, scale upwards from an assumed norm (as in es war sehr interessant ‘it was very interesting’). While male speakers also prefer to use amplifiers over downtoners, they do have a tendency to tone down the meaning of adjectives, that is, scale downward from an assumed norm more frequently than female speakers (as in es war ein bisschen interessant ‘it was a little bit interesting’).Footnote 26

As for age, the model also found that this was a statistically significant factor in determining the frequency of intensifiers. It was found that speakers aged 0–14 use intensifiers less frequently than all other age groups. A graphical representation of this finding can be seen in figure 4. A possible explanation for the low frequency in the youngest speakers is that intensifiers are likely to be acquired at a later stage. This is a reasonable suggestion given that intensifiers are adjuncts within adjectival phrases, which means that speakers would likely acquire adjectives first and then intensifiers. As there were several speakers in the 0–14 age group as young as 2, 3, and 6, this explanation seems plausible.Footnote 27 The model also indicated that speakers aged 15–24 intensify adjectives significantly more frequently than speakers in the other age groups, which corroborates previous crosslinguistic findings on the language of adolescents and young adults, and their desire for intensification (Androutsopoulos & Geogakopoulos 2003, Palacios Martínez & Núñez Pertejo Reference Palacios Martínez and Núñez-Pertejo2012).

Figure 4. Syntactic intensification of adjectives by age.

Previous research has also found that the intensifier voll ‘really’ is associated with youth speech (Androutsopoulos 1998, Kirschbaum 2002). The present study confirms this finding empirically: 42% of all instances of voll were uttered by speakers aged 15–24, which was statistically significant when compared to the other age groups. Note that 23% of all instances of voll were uttered by speakers aged 25–34. It is possible that this particular age group ranks second in their use of voll simply because those speakers used this intensifier in their youth, as reported in Androutsopoulos 1998:450–460, and continued to do so as adults. If this is true, then this may provide some evidence that the use of voll is not an example of age-grading, that is, the tendency of nonstandard features to peak during adolescence and then decrease in speakers’ “middle-years” (Holmes Reference Holmes1992:184).

However, according to the present dataset, the intensifier adolescents currently use most frequently is not voll but so. They used so 56 times, and voll only 27 times. Although, descriptively speaking, so was used more frequently by adolescent speakers than any other age group, it was still used frequently by all age groups, and the difference in frequency across age groups was not statistically significant. Unfortunately, it is unclear how frequent the adjective intensifier so used to be as Androutsopoulos (Reference Androutsopoulos1998:450) omitted this intensifier from his study. Nonetheless, if voll is still a maximizer, it would appear to be the most frequently used maximizer among adolescents twenty years after the study by Androutsopoulos (Reference Androutsopoulos1998:452). If voll and total are no longer maximizers, then the most frequently used maximizer among adolescents would be völlig. Interestingly, vollkommen was not used by the adolescent sample but was used by adult speakers. However, there were no instances of its use by speakers younger than 29 in the dataset.

While adolescents still frequently use the booster echt ‘real(l)y’, the booster recht ‘right’ has significantly decreased in frequency when compared to Androutsopoulos’ study (1998:450–455). Nonetheless, it appears that regardless of age, speakers use ganz ‘quite’ and sehr ‘very’ equally frequently. Descriptively speaking, total ‘totally’ and echt are used more frequently by speakers aged 15–24 than by any other age group.

The statistical model also found a significant interaction effect between the factors gender and age. The model found that male speakers aged 0–14 were more likely to intensify adjectives than female speakers aged 0–14, as shown in figure 5.

Figure 5. Interaction between the factors gender and age.

However, one should practice caution when interpreting these findings as there were only 5 male speakers aged 0–14 represented in the dataset versus 35 female speakers. Therefore, while the model takes uneven samples into account, it is to be advised that more data be collected from male speakers before drawing any conclusions.

5. Conclusion

In a broad sense, the present study suggests that the syntactic intensification of adjectives in German is similar to the syntactic intensification of adjectives in other Germanic languages. First, in examining the frequency and distribution of German adjective intensifiers, German amplifiers were found to be more frequent than German downtoners, and German boosters were found to be more frequent than German maximizers—a preference also observed in English. More specifically, the present study found that, with the exception of ganz ‘quite’, the top three German intensifiers were the counterparts of the current top three English intensifiers.

Second, by examining over 2,000 intensifiable adjectives the present study investigated whether the gender and age of the speaker were social factors that could influence the choice to use adjective intensifiers. The results have shown the age of the speaker to be a statistically significant factor as speakers aged 15–24 used adjective intensifiers more frequently than other age groups. These results tie in with what has been observed about adolescent speech patterns cross-linguistically (Palacios Martínez & Núñez-Pertejo Reference Palacios Martínez and Núñez-Pertejo2012). The results also indicated that the gender of the speaker was a significant social factor, which also corroborates crosslinguistic findings (Fuchs Reference Fuchs2017). In other words, if the speaker is female, the probability of adjectives being amplified is significantly higher than if the speaker is male. The fact that the gender of the speaker is a social factor in German may provide some support to the broader claim that female speakers have a tendency to use intensifiers more frequently than male speakers. This claim has typically been made based on English data, but, up until now, no studies had confirmed whether this is empirically true for German.

Perhaps even more interesting was the finding with respect to the use of downtoners: When a downtoner was used, the statistical probability of it being used by a male speaker was significantly higher than the probability of it being used by a female speaker. Similar results were reported in D’Arcy’s diachronic study of English (2015). In broader terms, this may suggest something about what it means to be male or female in current societies from the anthropological and sociological perspective. More specifically, female speakers prefer to amplify the meaning of adjectives by scaling upwards from an assumed norm. While the same is true for male speakers, male speakers have a tendency to tone down qualities denoted by adjectives so that they are below an assumed norm more frequently than female speakers.

While the present study bridged several gaps in research on adjective intensifiers in German, there are still numerous empirical gaps that were beyond the scope of this work and would provide an avenue for fruitful further research. For instance, what are the most frequently used intensifiers in other varieties of German such as Schweizerdeutsch ‘Swiss German’ or Plattdeutsch ‘Low German’, and do the results differ in any way from the synchronic results in the present study? How does the relationship between social factors and intensifier use play out in Germanic languages other than English and German, such as Norwegian or Dutch? While the present study investigated the effects of the social factors gender and age, the question remains whether other factors, such as social class, affect the use of German adjective intensifiers? By applying the taxonomy of Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985) and variationist methods, which allow one to examine intensifiers objectively, this study has shed light on a much-neglected area of quantitative research in German linguistics and provided a foundation for future research on intensifiers in German and in other Germanic languages.