“Civilization” is surely among those concepts that are the most widely used in international political discourse but taken the least seriously by contemporary social science. After Huntington’s (Reference Huntington1993, Reference Huntington1996) well-known “clash of civilizations” thesis generated a flurry of systematic large-N empirical studies in the 1990s and early 2000s, researchers quickly converged around the conclusion that civilizational divides are not a significant cause of conflict (e.g., Breznau et al. Reference Breznau, Kelley, Lykes and Evans2011; Fox Reference Fox2001, Reference Fox2002; Henderson and Tucker Reference Henderson and Tucker2001; Neumayer and Plümper Reference Neumayer and Plümper2009; Russett, Oneal, and Cox Reference Russett, Oneal and Cox2000).Footnote 1 While a few did uncover previously overlooked roles in international politics for religion, which Huntington argued was central to civilizational identity, these accounts tended to de-link religion from the concept of civilizations itself (Baumgartner, Francia, and Morris Reference Baumgartner, Francia and Morris2008; Fox Reference Fox2007; Grim and Finke Reference Grim and Finke2007; Johns and Davies Reference Johns and Davies2012). As a consequence, one now tends to find “civilizations” either not mentioned at all in the most important social science journals or cited as a foil against which scholars frame their own alternative arguments (e.g., Yashar Reference Yashar2007).

We argue it is high time for the social sciences to jettison the concept’s Huntingtonian baggage and study civilizational identity using the same conceptual and methodological tools that social science has developed to research other forms of identity. In doing so, we build on the pioneering work of a handful of scholars who have observed and documented such rhetoric and argued that civilizational concepts strongly influence the thinking of elites and intellectuals in certain countries (Abrahamian Reference Abrahamian2003; Eriksson and Norman Reference Eriksson and Norman2011; Katzenstein and Weygandt Reference Katzenstein and Weygandt2017; Linde Reference Linde2016; Rivera Reference Rivera2016; Tsygankov Reference Tsygankov2003; Zimmerman Reference Zimmerman2002, 178–182). We pay special attention to the even smaller set of studies that explicitly move us closer to a theoretical alternative to the Huntingtonian framework. Acknowledging Katzenstein’s (Reference Katzenstein2010, 36–37) admonition to recognize the “pluralism and plurality” involved in civilizational identity, we follow Brubaker (Reference Brubaker2017a, Reference Brubaker2017b) in identifying a process of “civilizationism” akin to the nationalism that was pursued by earlier generations of political entrepreneurs and Hale (Reference Hale2014) in arguing for founding a new theory of civilizational identity upon the most well-established accumulated findings of nonprimordialist research on identity (Chandra Reference Chandra2012).

One might argue we need evidence that civilizational identity has a major impact on attitudes or political outcomes before it is worthwhile studying its nature and sources, but we contend exactly the opposite: one can only adequately address the impact of civilizational identity once one has an adequate new way of conceptualizing it because concepts must guide operationalization and interpretation in the research process. The question of concept must therefore precede confident assessments of possible impact, yet we lack systematic empirical research into the validity of alternative conceptualizations of civilizational identity. This is what our study seeks to provide.

That said, there is more than enough prima facie evidence at hand to establish that civilizational identity is likely to matter and that, therefore, this line of research is important to pursue. Perhaps most obviously, world leaders, populists, pundits, journalists, insurgent groups, and other real-world political actors have been strikingly out of sync with the academics: such influential figures can frequently be found referring to “Western,” “European,” “Islamic,” “Asian,” “Orthodox,” “Christian,” or other “civilizations” in their appeals to domestic and international opinion, invoking such concepts to illuminate everything from the September 11 attacks in 2001 (Al Jazeera World 2011) to the rise of Southeast Asian powers (Mahbubani Reference Mahbubani1993).

Moreover, ordinary citizens themselves tell us that civilizational identity is important in their own thinking about international affairs. In a 2016 study carried out by the reputable Levada-Center in Russia at our request, when asked about the “main causes” of the conflicts in Ukraine and Syria, a quarter or more of the respondents identified “the striving of different civilizations to expand their influence in the world,” as can be seen in Table 1. The civilizational option was the second- or third-most frequently identified fundamental cause of these conflicts, and was chosen not much less frequently than were the most commonly picked causes. Of course, we cannot rule out that these citizens are unaware of what is really driving their views of the conflict, but this is ultimately an empirical question that constitutes grounds for pursuing further research, not for ruling it out.

Table 1. Percent of respondents giving the following answers from a closed list to: “Which of the following, in your opinion, are the main causes of the conflict in Ukraine and Syria?” Multiple answers were possible.

The survey was carried out May 22–25, 2016, on a nationally representative sample (N=1,602) on Levada-Center’s periodic omnibus survey using its standard methodology.

In calling for new research, we argue for the utility of a bottom-up approach, developing our new understanding of civilizational identity by looking at how the masses themselves—the people to whom leaders are appealing—understand it. In fact, we are aware of no prior published research that systematically analyzes mass public opinion primarily to study the nature of identification with purported civilizations, even though such data would appear crucial for understanding why leaders might choose to invoke notions of civilizations in their rhetoric. Just as establishing the sources of micro-level identification with nations is central to understanding the politics of nationalism, so we argue is it crucial to identify the sources of micro-level civilizational identification (or Brubaker’s “civilizationism”) if we want ultimately (in future research) to understand what its effects might be. Indeed, as research into “popular geopolitics” teaches us, discourses capable of shaping state behavior can both emerge and compete at the mass level (O’Loughlin and Talbot Reference O’Loughlin and Talbot2005; O’Loughlin, Toal, and Kolosov Reference O’Loughlin, Toal and Kolosov2005). We thus ask the following central question in our study: What influences individuals’ primary identification of their own country with one purported world civilization or other?

Accordingly, we begin below by reconceptualizing the notion of civilization in light of non-primordialist theories of identity and developing testable propositions that should help us establish the validity of the theory and distinguish it empirically from the older, more primordialist Huntingtonian logic. We then evaluate our approach by pooling survey data from early 2013 and late 2014 on identity politics in Russia, a country where civilizational identity is prominent in political discourse. We report strong evidence that Russians’ understandings of their country’s place in the set of “world civilizations” bear strong marks of social construction. In particular, it appears that whether Russians see their country as part of “European” civilization, “Asian” civilization, a “mix” of European and Asiatic civilizations, or a “distinct” stand-alone civilization is linked to gendered and nongendered socialization during the pre-reform Soviet period, post-Soviet experiences of opening up to the West, and factors as contingent as perceptions of Russia’s own economic performance. We also find a prominent role for geographic place in influencing individuals’ perceptions of Russia’s civilizational belonging in ways consistent with constructivist rather than Huntingtonian theory. Indeed, our findings (which are also the first systematic test of Huntingtonian theory using public opinion data) fail to confirm Huntington’s notion that civilizational identity is linked to deep-seated, enduring cultural cleavages that become more salient as globalization progresses. Our study thus provides for a better understanding of what underlies identification with purported civilizations, which in turn will facilitate better future studies of its possible impact on major political outcomes that locals frequently frame as civilizational in nature. It will also enable more accurate anticipation of possible future shifts in mass senses of civilizational belonging.

Reconceptualizing Civilizations Theory

Hale (Reference Hale2004) argues that identity can be understood as a set of personal points of reference that enable individuals to navigate the social world, with identity categories like ethnicity or class helping the brain simplify the otherwise hopelessly complex task of comprehending how one fits into the world of everyone else around them. Within this framework, “civilization” can be defined as a high-order identity category based on cultural (as opposed to physical) attributes that occupies a level of abstraction between “human being” and “ethnic group” or “nation,” tending to subsume multiple nations and ethnic groups but not all of them. Importantly, by not ruling out other as-high or higher-order identity categories, we diverge from Huntington’s (Reference Huntington1993, 24) definition of civilization as the “broadest level of cultural identity” short of human. We also do not adopt his definitional assumption that people’s identification with civilizations is necessarily “intense” (Huntington Reference Huntington1993, 24).

By describing civilizational identity as a social construct (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017a; Hale Reference Hale2014; Katzenstein Reference Katzenstein2010), we are saying that one’s own understanding of one’s civilizational belonging will not spring sui generis from one’s own mind or from purely objective observations. Instead, it will reflect what you believe about yourself and your place in the larger social world in light of how others perceive you and how you perceive that others perceive you, all subject to the requirement that your belief provides you with some cognitive capacity to make sense of one’s social environment (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2004; Chandra Reference Chandra2012; Hale Reference Hale2004; Hopf Reference Hopf2002). And because the social world is not perfectly knowable, this reflexivity is potentially subject to many kinds of influences, including agential attempts to shape understandings in competition with other would-be narrative-shapers (Abdelal et al. Reference Abdelal, Herrera, Johnston and McDermott2009).

First and foremost, this means there is no natural, clearly bounded set of civilizations that objectively exist in any one time or place (Hale Reference Hale2014). Instead, this is ultimately an empirical question on which not every individual will agree (Katzenstein Reference Katzenstein2010). While we may develop theory on what influences identity, which civilizations can be said to “exist” depends on the totality of individual-level beliefs about what the most salient higher-level identity categories are, and how one chooses to aggregate these beliefs.

This leads us to a core theoretical proposition: systematic research into the totality of individuals’ perceptions of civilizational identity becomes foundational to a true constructivist understanding of civilizational politics. Only with this understanding can we begin to capture what drives different people to have different civilizational identifications, and only at that point are we in a strong position to examine what the effects of civilizational identification might be on high politics, including war, ethnic conflict, or patterns of domestic politics in a given country. This is where our study picks up, laying out some initial theoretical ideas as to what might influence civilizational identification and then testing them systematically using survey data on a country where civilizational identity is widely regarded to be salient and contested.

Since civilization is a macro-level identity category, civilizational identification can take at least two different forms at the mass level. One form reflects the civilization with which the individual personally and directly identifies. A second form is mediated by mid-level identity categories like “nation,” “ethnic group,” “state,” or“country,” reflecting individuals’ identification of their own nation/group/state/country as belonging to one civilization or another. Such indirect, mediated civilizational identification is important to distinguish from direct personal identification because “civilizational identity entrepreneurs” frequently talk not about the civilizational belonging of collections of individuals as individuals, but about the civilizational belonging of their own “country” or “nation” as a whole. We will demonstrate this below in the case of Russia.

Because elite discourse tends to stress the civilizational belonging of nations and countries, and because elites typically elide the distinction between nations and countries, we concentrate in this study on individuals’ civilizational identification as mediated through one’s own country. Specifically, focusing on civilizational alternatives that are available in elite discourse, we ask: What leads people to identify their own country as primarily belonging to one particular civilization as opposed to another?

Contrasting Expectations

If civilizational identity is socially constructed in the way most social science research now concurs other identities like ethnicity and nation are, as is the baseline theoretical claim of our study, people’s identification of their own country with one civilization or other should reflect locally important construction processes (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017a; Katzenstein Reference Katzenstein2010). Such processes are likely to be context-specific, though some meaningful generalizations are possible.

For one thing, because education and state nation-building efforts are widely documented to be important shapers of identity (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996; Darden and Grzymala-Busse Reference Darden and Grzymala-Busse2006; Darden and Mylonas Reference Darden and Mylonas2016; Gellner Reference Gellner1983), we would expect individuals’ senses of civilizational belonging to be strongly associated with the extent and type of their exposure to different official state narratives in both past and present. In contrast with the primordialist expectation that location on civilizational fault lines naturally breeds enmity, a constructivist perspective allows for the possibility that physical proximity can foster mutually profitable interactions, common practices, and senses of cultural commonality (Hale Reference Hale2014, 9–13), which in turn might promote identification with that “other civilization.” Moreover, if identity is not necessarily only about deep, unchanging attributes but also about understandings of one’s place in the world that can change along with a rapidly changing environment (Hale Reference Hale2014, 11), then we might expect people’s civilizational perspective to be influenced by such changes, including those of a highly contingent nature.

This contrasts with what one would expect from the older, Huntingtonian theory of civilizational identification. For Huntington (Reference Huntington1993, Reference Huntington1996), senses of civilizational identification first and foremost reflect deep cultural divides that tend to subsume ethnic groups and correspond most closely to world religious traditions. If this theory is valid, we would expect perceptions of a country’s civilizational belonging to be strongly patterned by ethnicity and religion. Moreover, central to Huntington’s thesis is that these cultural differences will become more salient as globalization and other processes bring people from deeply different cultures into contact with each other. Such contact, he writes, can come from various forms of human travel, especially migration. Thus we would expect civilizational identification to be shaped by contact with migrants and travel outside one’s country, where one encounters other people and learns about which countries do and do not share the deep civilizational attributes that one identifies with one’s own country. Relatedly, when it comes to geographic place, people living in regions physically closest to the “fault lines” of perceived civilizations should be expected to be most likely to come into contact with representatives of other civilizations and to be aware of the distinctions.

Russia’s Value for a Theory-Building Study of Civilizational Identity

Russia is useful for building new theory on civilizational identity for at least two reasons. First, civilizational identity in Russia is contested (Katzenstein and Weygandt Reference Katzenstein and Weygandt2017), providing the crucial variation necessary for examining what leads different individuals to associate the same country (their own) with different purported world civilizations. Second, the concept of civilization is quite prominent in contemporary Russian political discourse, including state rhetoric justifying major policy moves, making it substantively important to understand in its own right (Tsygankov Reference Tsygankov2014, Reference Tsygankov2016). Indeed, Russia powerfully exemplifies the very puzzle that motivates this study with respect to many countries of the world: the prominent invocation of civilizational concepts in Russia is wildly out of sync with the social science community’s low level of attention to them.

Civilizational Discourse in Russia

Perhaps the most obvious evidence of the importance of civilizational discourse in Russia and the locally contested nature of Russia’s civilizational belonging is the immense appeal of Huntington’s theories there (not to mention the rest of the post-Soviet space). His 1996 book was translated into Russian in 2003 and became a bookstore blockbuster. The Russian state has proven permeable to such civilizational narratives. In 2008, under Dmitry Medvedev’s presidency as Putin temporarily shifted to the post of prime minister, Russia’s official foreign policy concept explicitly adopted a civilizational framework. For “the first time in contemporary history,” it declared, “global competition is acquiring a civilizational dimension which suggests competition between different value systems and development models within the framework of universal democratic and market economy principles” (“The Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation” 2008). Perhaps most dramatically, in his address announcing Russia’s annexation of Crimea on March 18, 2014, Putin declared that Grand Prince Vladimir’s adoption of Orthodox Christianity on that peninsula over a millennium ago had laid the “civilizational foundation” that today unites Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus (Putin Reference Putin2014).

That said, Russian leaders tend to use the term civilization in different ways at different times. To illustrate this, we searched the official presidential administration website, which archives speeches and other public statements made by Putin and Medvedev as president. This collection thus is a reasonable reflection of what the very top Russian state leadership deems important in its connection with the public. Among these speeches, we find 288 uses of the term “civilization” (tsivilizatsiia), or its adjectival form, between 2000—when Putin first assumed the presidency—and the end of the period covered by the public opinion data at the center of our study (2013–14). As Table 2 shows, of these 288 occurrences, well over half (173) use the term in the sense of “world civilization,” or as the antonym of barbarity, for example, in citing the victory over Nazism. The remaining instances refer to particular “civilizations” or to the existence of multiple civilizations (as in “dialogue of civilizations”) and about half of these (52) are devoted to Russia’s belonging to a particular kind of “civilization.”

Table 2. By type, the frequency of Russian presidents’ usages of the term “civilization” (or its adjectival forms) in public remarks archived in the official presidential website Kremlin.ru, 2000–2014.

Compiled by the authors from the official website of the President of the Russian Federation, Kremlin.ru.

As for where Russia’s leadership says its country fits in, despite the attention given in media and some scholarly accounts to Eurasianism in Russia, more references are in fact to Russia as part of European civilization (24 references) or a “Christian civilization” (6 references) during the period that interests us here. The vocabulary used to describe this belonging is always very plain and deep, featuring statements such as: “Russia is an indivisible part of European civilization” (Putin Reference Putin2000); “Russia’s cultural roots are in European civilization” (Putin Reference Putin2007); and Russia is a “branch of European civilization” (Medvedev Reference Medvedev2010). We note that in these statements, the talk is explicitly of “Russia” (the country) having European civilizational belonging.

References to European civilization seem to have been partly replaced—especially since 2013—by references to a “Christian civilization” that is not limited to Orthodoxy. Prior to 2013, references to Christian civilization occurred mostly in the context of celebrating Orthodox Christianity as the cultural basis of Russia, but after 2013 they have been used to attach Russia to a pan-European Christian identity. Related to Putin’s “conservative turn”Footnote 2 in the wake of massive “liberal” protests in 2011–2012, the shift to a pan-European Christian “civilizationism” has enabled the Putin regime to dissociate itself from “liberal” Europe while simultaneously preserving the idea of Russia as an inalienable core of an “authentic” Europe that is under assault (Laruelle Reference Laruelle, Kolstø and Blakkisrud2016). This positioning also helps make sense of the common language the Kremlin has been able to find with many far-right organizations in Europe and the US.

The notion of Russia as “Eurasian civilization” appears less regularly in the rhetoric of state leaders on their official website (7 times), being utilized in particular under two main circumstances. First, it emerges when the president emphasizes his country’s role in combining or bridging East and West, Europe and Asia, being a crossroads of continents and civilizations. Such language is also invoked when the Russian leader is celebrating specific Russian places or regions that are seen to straddle Europe and Asia spatially or culturally, as with Chechnya, the Black Sea, the Volga region, Tuva, Vladivostok, and the historic cities of Kazan and Astrakhan. This Eurasian narrative was most visible in the early 2000s (with several invocations in 2000 and 2004–2006) and then appeared several times again between 2011 and 2014. Overall, the pattern is of intermittent usage driven by specific occasions for which it is expedient to make reference to bridging, combining, or mixing.

In addition, Russia’s leadership sometimes refers to Russia itself as its own distinct civilization. The Russian-language adjective applied in such instances for “Russian” is always rossiiskaia, which connotes a broader sense of inclusion of minority groups (those associated with the country), and never russkaia, the somewhat narrower word. In the early 2000s, “Russian civilization” served as a generic term to describe Russia’s status compared to other “big” civilizations associated with particular countries (India, China, Indonesia, and the US being the ones mentioned). Since 2013, however, the term’s usage greatly expanded, no longer primarily for comparison but now as a way of emphasizing that Russia has a distinct value system of its own. The vocabulary accompanying this usage since 2013 is telling, including such words as powerful (moshchnaia), unique (unikal’naia, samobytnaia), multinational (mnogonatsional’naia), country-civilization (strana-tsivilizatsiia), and state-civilization (gosurdarstvo-tsivilizatsiia). Overall, during 2000–2014, Russia’s top leadership refers to “Russian civilization” 15 times in the materials on the Kremlin’s website.

The notion of civilization, then, is not only prominent in Russian elite discourse but actively used by the state as the representative of the country’s identity, including to justify highly consequential moves like the annexation of Crimea. At the same time, we confirm Katzenstein’s (Reference Katzenstein2010, Reference Katzenstein and Weygandt2017) argument that civilizational identity in Russia—as with other forms of identity (Abdelal et al. Reference Abdelal, Herrera, Johnston and McDermott2009)—reflects both pluralism and plurality, with different thinkers and actors advancing different visions as to how Russia fits in to what one might call the world “civilizational map.”

Moreover, we find that the state’s own invocations of “civilization” are demonstrably vague and inconsistent (Linde Reference Linde2016). At times, the term refers to a humanist, universalist tradition of describing human history and world progress. At other times, the concept reflects a Huntingtonian culturalist narrative that classifies countries by “civilization.” And while it is usually always about Russia’s role in the world and its interaction with its neighbors, even this usage stands out for remarkable plasticity and inconsistency as the notion of civilizational identity is strategically deployed in a highly situational manner to evoke contingency-specific feelings of shared perceptions. We thus find that Russian authorities use “civilization” as a discursive repertoire to foster feelings of consensus, with the substantive contents emptied or filled in according to circumstance.Footnote 3

The most important conclusion for setting up our study’s analysis of micro-level patterns of identification, then, is as follows: individual Russian citizens operate not in a rigid, settled identity space but in a social space where they are likely to encounter a wide variety of ways in which one can think about Russia’s civilizational belonging. And more specifically, given rhetoric that is likely to be familiar to them from the discourses of their top leadership and prominent public figures, the main alternatives are likely to be understandable to ordinary people as “European civilization,” a “mixed” European-Asian civilization, and its own distinct civilization. We now turn to examining potential influences on individuals’ own civilizational perceptions of Russia with respect to these categories that are available to them in elite discourse.

The Data

To study how individuals perceive Russia’s civilizational belonging, we engage data collected by the ROMIR survey agency in Russia and made publicly available by the New Russian Nationalism (NEORUSS) project (Kolstø and Blakkisrud Reference Kolstø and Blakkisrud2014). Here, we use this project’s two nationwide surveys, the first being in the field May 8–27, 2013—prior to the outbreak of protests in Ukraine that led to the 2014 revolution—and the second carried out November 5–18, 2014—after Russia had annexed Crimea and started backing a growing insurgency in eastern Ukraine. The samples were each designed to be nationally and demographically representative, with 1,000 respondents in 2013 and 1,200 in 2014. Surveys were conducted in Russian. Crucially for our purposes, these two surveys contain identical questions on Russia’s civilizational belonging along with other items that enable us to test different theories of perceived civilizational belonging. The fact that the two surveys span the Crimea annexation and other major events of 2014 also enables us to assess whether the outbreak of conflict impacts perceptions of civilizational identification.

The central outcome we seek to explain in our statistical analysis is the pattern of responses to a question asking people to name the civilization of which Russia is a part while reading them a list of possibilities that include European civilization, a mix of European and Asian civilizations, a stand-alone Russian civilization, and “Asian (eastern)” civilization. Table 3 presents the exact wording along with the basic distribution of answers in both 2013 and 2014.

Table 3. “People often discuss the place of Russia in the world. Tell me please, do you consider Russia to be part of European civilization or something else? Please choose the answer that you think is most correct” (estimated percentage of population giving each answer, from NEORUSS 2013 and 2014 surveys, question 37).

For this table and all other calculations from these data, we adjust standard errors for regional clustering and use weights to adjust the NEORUSS sample to country population statistics.

We note that this question does pose analysts with some interpretational challenges. First, it presumes the “existence” of “civilizations” generally. The main downside of presuming the existence of civilizations is that the survey may lead people who do not think about civilizations in their daily lives to answer in civilizational terms. While true, confronting individuals with questions or situations that they do not necessarily think about in everyday life is an unavoidable feature of virtually all survey research, which has generally found that responses are meaningful when interpreted with care and proper appreciation for margins of error (Zaller and Feldman Reference Zaller and Feldman1992). And people for whom the notion of civilization is completely alien—or for whom the given choice set is completely off base—can always respond “I find it hard to say” or refuse to answer, response categories that were coded by the interviewers and appear in the dataset.

Second, we observe that the survey presents respondents with a specific set of alternatives, which could mean that other existing alternatives are left out. Our analysis of state leaders’ public rhetoric above, however, indicates that the alternatives given in this item all (except for Asian civilization) figure in prominent elite discourse and are thus reasonable choices to include in a first empirical analysis like ours. Thus, while a handful might imagine Russia as part of “Islamic civilization,” which is not included, this alternative hardly figures in elite discourse, not to mention the public rhetoric of respondents’ most prominent representatives. Similarly, the option “combination” or “mixed” (smes’) would likely capture all those who believe that aspects of both European and Asian civilizations can be found in Russia with various degrees of blending, including a situation in which Russia is simultaneously part of multiple civilizations. A few may opt for “hard to say” if they insist on a particular form of multiple civilizational belonging that is not specified in the question, but such nuances do not figure significantly in state leader rhetoric.

Third, the given alternatives might each have been named slightly differently in ways that might have generated different results. For example, the NEORUSS question’s wording explicitly associates civilization with notions of geographic place: “European” (evropeiskaia), “Asian/eastern” (aziatskaia/vostochnaia), or combinations thereof. This may have primed respondents to have spatial considerations more strongly in mind than they otherwise would have. Asking about specifically European civilization may also have evoked associations related to the European Union and its normative agenda, which Russian authorities were actively criticizing during the period of our study. It may also call to mind individual countries prominently associated with Europe in Russians’ minds, countries often known to the Russian public through their culture and history without primary association with normative agendas or politics. Thus, alternative specifications might have explicitly linked the given civilizational possibilities to certain values, particular religions, or other terms linked to geographic place with somewhat different associations (e.g., “Western,” zapadnaia). The NEORUSS survey’s combining of “Asian” and “eastern” (possibly also translated as “Oriental” in this context) may potentially evoke different or even conflicting associations: the unqualified term “Asia” in Russia usually calls to mind China, Japan, and the Asian-Pacific world, while “eastern/Oriental” can be understood as focusing mostly on the Muslim world from the Middle East to Central Asia.

We do not see any particular advantages to any alternatives to the NEORUSS measure, however. Each would bring its own specific connotations and raise its own problems of specification, including which values to stress as distinctive for each civilization or whether, for example, to refer to “Orthodox” (pravoslavnaia) or more generally “Christian” (khristianskaia) civilization. As for the concept of “Western” civilization, it is conventionally more negative in Russia than “European” since “Western” has a stronger geopolitical connotation embodied by the United States and transatlantic institutions, such as NATO. “European,” on the other hand, connotes not only Europe in the sense of continental Europe without the United States but also Europe as a way of life, a history and culture, Christian roots, and a socially oriented welfare model. Finally, notions of the “eastern” or “Oriental” have long been part of Russia’s intellectual history, and some research finds that Russians may see themselves as “Oriental” in setting themselves up in opposition to the West (Morozov Reference Morozov2015). And most importantly, our examination of the usage of civilizational concepts in Russian state and public intellectual circles assures us that the alternatives given in the NEORUSS question (and as worded there) are indeed likely to be among the most familiar to respondents, who in any case could always respond “hard to say” if they found the categories a complete mismatch with their thinking.

Overall, while all these concerns should inform our interpretation, they should not undermine our ability to meaningfully address our central question regarding factors that shape identification of countries with different civilizations. In short, if a given theory of civilizational identification is valid, it should be able to explain the most important differences in how individuals respond to the NEORUSS question that we examine here. And we can gain added confidence by explicitly examining patterns among those who respond “hard to say” or refuse to answer, as we do below.

The NEORUSS 2013 and 2014 datasets, both designed to study Russian nationalism, also contain a number of items enabling us to test the main theoretical expectations discussed above. If our constructivist approach is valid, we would expect beliefs about Russia’s civilizational belonging to reflect patterns of socialization, for which we include straightforward measures of demographic traits that are strongly linked to socialization processes, sex,Footnote 4 education,Footnote 5 income,Footnote 6 age,Footnote 7 and—following calls to take different sorts of Soviet experience seriously (Pop-Eleches and Tucker Reference Pop-Eleches and Tucker2017)—whether an individual’s conscious orientations would have been formed almost entirely after the phase of Soviet rule that was most clearly committed to developing separately from and in a fundamentally different way from the West (a variable we label “Gorbachev era & younger”).Footnote 8 Another sign of the constructivist approach’s validity would be evidence for contingent influences on civilizational identification, leading us to include perceptions of economic trends at both the personal pocketbook level (“Pocketbook up”)Footnote 9 and the level of the Russian economy as a whole (sociotropic perceptions, or “RF economy up”)Footnote 10 as well as patterns of media consumption, specifically investigating whether reliance on the Internet (the primary alternative to state-dominated television) for news shapes perceptions of Russia’s civilizational belonging.Footnote 11

If Huntingtonian theory is valid, on the other hand, we would expect individuals’ identification of their country’s civilizational belonging to be influenced first and foremost by religion, ethnicity, and factors linked to globalization that bring distinct “civilizations” into contact with each other. We thus create binary variables capturing Russian ethnicity,Footnote 12 a practicing profession of Orthodox Christianity (“Orthodox pious”),Footnote 13 identification with Russia’s largest minority religion (“Muslim”),Footnote 14 whether someone has traveled outside Russia in the last five years (“Travel in last 5 years”),Footnote 15 and whether individuals are in contact with migrants (“No contact migrants”).Footnote 16 Contact with alternative civilizations would also be likely to occur on Russia’s borders, so we include binary variables capturing whether individuals live in a Russian western border regionFootnote 17 and whether they live in the Far East.Footnote 18 Finally, we control for the scale of the community in which one lives.Footnote 19

Analysis of Results

One of the most important findings has already been reported (Table 3): Russian citizens are indeed conversant in civilizational identity categories. 90%–92% percent of citizens surveyed in 2013 and 2014 identified Russia with one or another civilization, with fewer than 10% being so unfamiliar with the concept that they were unable or unwilling to do so. Moreover, there is no universal agreement on which civilization is Russia’s own. All this adds to the motivation for our study: there is thus evidence not only that elites use civilizational categories but also that the masses find these categories tractable, making it important to understand the sources of identification with them. And the fact that individuals differ in how they apply these categories to Russia provides insight into the factors that lead different people to associate their country with one purported civilization or another.

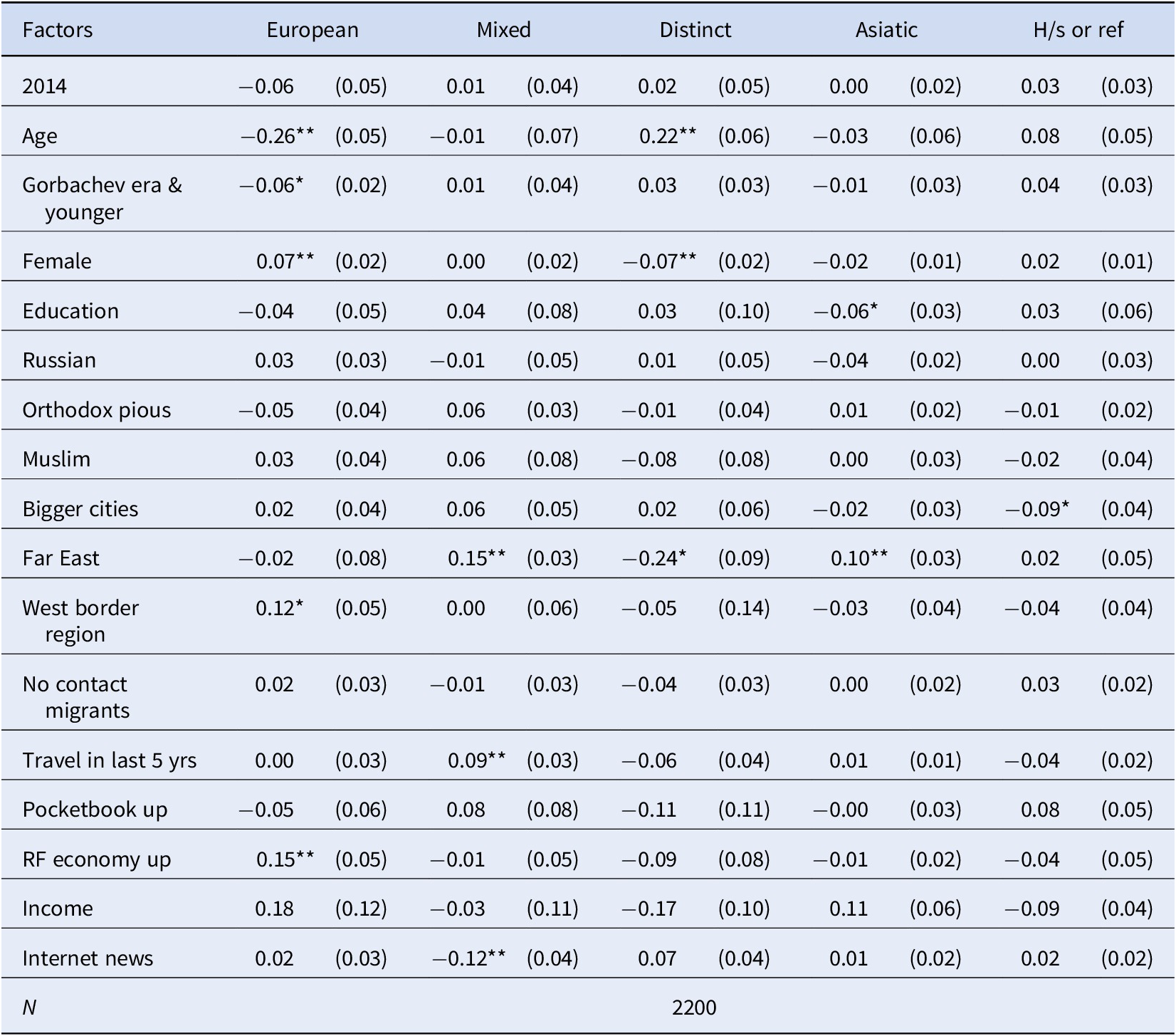

Table 4 thus presents findings from a regression analysis of the pooled NEORUSS data from 2013 and 2014 using a multinomial logit model, which is appropriate for dependent variables consisting of more than two unordered categories, as is ours. Since the coefficients generated by such models do not facilitate ready interpretation, we instead present results as full effects. The full effect of a factor is the difference it makes in the probability of an outcome occurring when we raise that factor from 0 to 1 while holding all other variables at their actual values in the dataset and (re)scaling all variables to range from 0 (its minimum observed value in the dataset) to 1 (its maximum observed value).Footnote 20 Following a widespread convention, we deem an estimated relationship significant only if we can rule out zero effect with at least 95% confidence (i.e., if p≤.05).

Illustrating how to interpret the table, we turn to the first row, which tells us that the major crisis breaking out in 2014—including Russia’s annexation of Crimea, military intervention in eastern Ukraine, and a drastic deterioration in relations with the West—had no significant impact on individuals’ senses of civilizational belonging. Thus, while our model reports that on average people became 6 percentage points less likely to identify Russia with European civilization (a full effect of 6 percentage points), 1 percentage point more likely to identify it with a mixed European-Asian civilization, and 2 percentage points more likely to identify it as a distinct stand-alone civilization between the 2013 survey and the 2014 survey, none of these differences are statistically significant. Nor do people become more or less likely to categorize Russia in civilizational terms at all: people in 2014 are an average of 3 percentage points more likely to give answers of “hard to say” or refusal to answer, but this difference is also statistically insignificant. This suggests that Russia’s conflict with the West over Ukraine did not significantly impact patterns of civilizational identification in Russia.

Findings on Constructivist Theory of Civilizational Identity

The results in Table 4 broadly testify to the promise of understanding civilizational identity from the perspective of constructivist theories of identity. We find strong evidence that people’s understandings of Russia’s relationship to alternative purported civilizations are shaped by patterns of socialization (as reflected in findings on age, upbringing, gender, and place) and contingent understandings of Russia’s own performance, its economic trends in particular.

Table 4. Full effects of factors on the probability someone identifies Russia with European, Mixed, Distinct, or Asiatic civilization in 2013–2014.

Standard errors in parentheses.

Calculated using multinomial logit model from pooled NEORUSS 2013 and 2014 survey datasets.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

The strongest overall predictor of civilizational categorization is age, with the oldest people in the sample being 26 percentage points less likely to identify Russia with European civilization and 22 percentage points more likely to consider it a distinct civilization. In short, the older people are, the more likely they are to identify Russia as a distinct stand-alone civilization, while the younger they are, the more likely they are to identify Russia with European civilization—even controlling for factors like urbanization, education levels, income, place of residence, media consumption habits, and travel experience. This is hard to explain through any property intrinsic to age itself, and so it likely reflects different life experiences of older people relative to younger people having to do with imbibement of Soviet narratives of Russia blazing its own distinct path to a distinct modernity. This result also controls for what many would consider a breakpoint in the Soviet socialization process, the point at which Gorbachev came to power and began a process of reforms that involved opening up to the West. Somewhat surprisingly, however, people on the younger side of this breakpoint (those who were age 6 or younger, if born at all, in 1985) are 6 percentage points less likely in 2013–2014 to consider Russia part of European civilization—again, controlling for their age. Thus, it would appear that more extended socialization in the Soviet period facilitated identification with a distinct Russian civilization and a rejection of European civilization; however, this effect is moderated by a lifetime of exposure to the post-1985 period that had its own distinct negative effect on identifying with Europe. The latter effect is plausibly related to disillusionment with attempts to integrate with the West (Sokolov et al. Reference Sokolov, Inglehart, Ponarin, Vartanova and Zimmerman2018). And the overall patterns regarding age resonate with other research finding that Soviet nostalgia is greater among older people but also present among youth who did not personally experience the USSR: according to a May 2012 survey, 90% of the older generation regrets the Soviet collapse compared to 46% of youth, and 51% of the older population hopes for the return of the Communist Party as opposed to 21% of youth (Sullivan Reference Sullivan2013, 3).

Table 4 also reports strong full effects for gender on senses of civilizational belonging, a finding that was unanticipated by the authors and extant theory but is difficult to explain through anything other than socially constructed understandings that vary with gender. Specifically, women are 7 percentage points more likely to identify Russia with European civilization than are men and also 7 percentage points less likely to identify Russia as a stand-alone civilization. While precise mechanisms will need to be tested in future research, we venture that this effect has to do with the attractiveness of Europe’s identification with a higher status for women, a status that had been relatively high in the Soviet period but regressed as “traditional” norms resurfaced after the demise of the USSR (Sperling Reference Sperling2014). Thus, among women specifically, the USSR’s socialization in favor of women’s rights—precisely because post-Soviet countries have regressed from those norms—may ironically have fostered an identification of Russia with what is seen as a more pro-woman European civilization and created reluctance to admit Russian belonging to a less equal-rights-oriented distinctly Russian civilization.

Another noteworthy result is that spatial patterning is consistent with the constructivist logic outlined above: proximity is linked to greater identification with the nearby civilization rather than rejection. Similarly, living in Russia’s Far East makes individuals more likely to see Russia as part of either Asian civilization or a “mixed” European-Asian civilization, and less likely to see it as a distinct stand-alone civilization. We also note that the full effects involved in the significant results are very large: between 10 and 24 percentage points. We are careful to note that, by itself, these findings are not strong support for constructivism: as discussed earlier, the adjectives used to specify civilizations in the NEORUSS survey instrument—“European,” “European and Asian,” and “Asian/eastern”—may have cued respondents to give answers that correspond with their own personal perspective on Russia’s geography, with people physically in continental Europe more likely to link Russia with things “European” and people physically in continental Asia more likely to link it with things “Asian” or “eastern.” That said, the tendency to see Russia’s place in the world through one’s own physical location is itself a product of social construction (O’Tuathail Reference O’Tuathail1996). And opportunities for cross-border interactions do exist for border areas that make it plausible to argue that senses of commonality and mutual profitability could emerge, impacting senses of civilizational belonging. The interpretation that exposure to other civilizations is breeding senses of commonality and mutual identification rather than hostility is also consistent with our finding that people who have traveled in the last five years are more likely to see Russia precisely as a mixed civilization, with elements of both European and Asian civilization (with a full effect of 9 percentage points).

Finally, we find evidence for the influence of highly contingent developments that the constructivist approach to civilizational identity would expect but not the Huntingtonian perspective. In particular, people who think Russia as a whole is doing better economically are found to be 16 percentage points more likely to identify their country with European civilization, even controlling for income, people’s personal economic experiences, and urban residence (none of which are significant). It strongly appears that since European civilization in Russian discourse is identified with prosperity and development, people who think Russia is experiencing movement in this direction see more affinity between Russia (the country) and European civilization. Indeed, Europe is frequently held up as a standard for what a “normal” country is like, in which context “progress” can be seen as approaching Europeanness. And conversely, the aforementioned survey research on Soviet nostalgia has found that feelings of nostalgia for the USSR are more widespread among the financially insecure part of the population (Sullivan Reference Sullivan2013, 4).

There is also some evidence that civilizational identification is linked to media consumption, as would be expected by a constructivist perspective. Those who rely primarily for their news on the Internet, which also means the main category of people who do not get news mainly from state-dominated television, are less likely to view Russia as a civilizational mix relative to all other responses. This makes sense in light of the evidence presented earlier that Russia’s state leadership itself, which tends to dominate television, is inconsistent in promoting civilizational narratives. It also fits with past research finding that Russian political behavior is powerfully driven by what they consume on television (Oates Reference Oates2013), while also noting that television influences Internet content, weakening the power of this distinction (Cottiero et al. Reference Cottiero, Kucharski, Olimpieva and Orttung2015). Finally, education levels are not a significant predictor by themselves beyond a negative correlation with Asian civilizational identity.

Findings on Huntingtonian Theory of Civilizational Identity

We now turn to the results’ implications for Huntington’s theory of civilizations. Most importantly, we provide the first systematic survey-based confirmation of the widespread belief among social scientists that this approach does not accurately anticipate how ordinary people perceive civilizational identity. In particular, Table 4 reports that senses of Russia’s civilizational belonging are related neither to religion, nor to ethnicity, nor to processes linked to globalization that bring people together—at least, not in the way the Huntingtonian approach implies should be the case.

Taking religion first, neither Orthodox piety nor adherence to Islam is associated with categorizing Russia as part of European, Eurasian, or Asian/Eastern civilization. We would also note that the results do not change in any significant way if we conduct the same analysis reported in Figure 4 but with only the NEORUSS survey’s ethnic Russian respondents (dropping all ethnic minority respondents).

Accordingly, ethnicity also turns out to be a poor predictor of how people understand Russia’s civilizational belonging. Perhaps most surprisingly, we do not find ethnic Russians standing out from non-Russians for seeing Russia as part of any particular civilizational category; ethnicity appears to be a nonfactor in shaping civilizational discourse. These findings on religion and ethnicity resonate with other research that documents an absence of meaningful opposition from religious or ethnic minorities on important questions of state-level identity and policy in Russia (Alexseev Reference Alexseev, Kolstø and Blakkisrud2016; Gerber and Zavisca Reference Gerber and Zavisca2017).

Similarly, while Huntington posited that international travel and contact with migrants would evoke civilizational difference and hence sharpen divides in how people interpret their own place among world civilizations, we find no clear evidence for this here. People who have come into contact with migrants do not stand out for identifying Russia with any particular civilization or even with the tendency to associate Russia with any civilization at all (as opposed to being unable or refusing to do so). Moreover, we find that traveling abroad is associated not with sharpening senses of civilizational difference but with seeing Russia precisely as having mixed civilizational identity.

Results regarding spatial patterning, however, weigh clearly against Huntingtonian expectations. Instead of location near border regions (which we posit is likely to reflect greater cross-border regional interaction) making people more likely to realize civilizational differences and feel threatened or even hostile, as one interpretation of Huntingtonian theory would have it, borderland experience appears to make individuals more likely to identify Russia with the purported “bordering civilization.” Living in a region on Russia’s European border thus makes an otherwise average individual 12 percentage points more likely to identify Russia with European civilization, while living in Russia’s Far East makes one 10 percentage points more likely to think of Russia as part of Asian civilization, 15 percentage points more likely to see Russia as of mixed civilizational belonging, and 24 percentage points more likely to reject the idea that Russia is civilizationally distinct. As noted above, these findings are consistent with research on how identity tends to be constructed in borderlands.

Responses of Hard to Say and Refusal to Answer

Importantly, our method does not attempt to ignore responses of “hard to say” or “refusal to answer” by counting them as “missing data” but instead treats them as a distinct, substantively meaningful response category in the statistical analysis reported in Table 4. As can be seen, however, such responses are not correlated with any factors of interest, being generally unstructured. This indicates these responses are not primarily masking significant overlooked civilizational identifications, but they are instead reflecting the simple apathy that prior research has found frequently lies behind failure to answer certain kinds of survey questions in Russia (Carnaghan Reference Carnaghan1996). It also makes sense that the most rural respondents would be the most apathetic to such global concerns as civilization identity, accounting for the lone statistically significant finding here.

A Research Agenda

Overall, we have argued that the discourse of “civilizations” is too prominent in too many important places at too many critical moments for social science to ignore. While extensive research has roundly and convincingly debunked Huntingtonian concepts of civilizations, it is unfortunate that researchers have essentially thrown the proverbial baby out with the bathwater of Huntington’s theory. Instead, we suspect that being guided by Huntingtonian notions, researchers have been looking in the wrong places and using the wrong conceptual tools. Instead, we argue for following a nascent research movement (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017a; Hale Reference Hale2014; Katzenstein Reference Katzenstein2010) that calls for reconceptualizing the whole notion of civilizations, essentially building new theory from the bottom up that sheds problematic primordialist Huntingtonian assumptions and instead rests upon all that we have learned from several decades of constructivist research into the nature of identity. While prior work has convincingly debunked Huntington, our study is the first to provide systematic empirical confirmation for the validity of a specific alternative approach, paving the way for future research that can take a further next step by assessing the impact of civilizational identity on important outcomes of interest.

We demonstrate the validity of this approach by pioneering the study of mass-level civilizational identity, which has actually not yet been systematically studied even with respect to Huntingtonian theory. Our study confirms the validity of our original motivation in several ways. First, the overwhelming majority of Russians are found able to place Russia in one of several alternative purported civilizations that tend to feature strongly in Russian public discourse. Second, senses of Russia’s civilizational belonging instead bear the strong imprints of social construction, being patterned by experiences and socialization processes linked to age, gender, and geographic place as well as by highly contingent perceptions, including that people are more likely to identify Russia with a prosperous European civilization when they believe Russia itself is performing well economically. Third, we find that Huntingtonian theory proves to be a very poor predictor of civilizational identification. Whether people identify Russia with different civilizations appears to be unrelated to individuals’ religion, ethnicity, or participation in practices of globalization that are posited to bring different civilizations into contact (and conflict) with each other.

This strongly suggests that the failure of prior empirically systematic research to uncover significant effects of civilizational identity may be because researchers were operating with an inadequate Huntingtonian conceptualization of civilizational identification. Accordingly, our study opens important new pathways for thinking about the meaning of civilizational identity to ordinary people, inviting comparative research on public opinion in other countries as well as new research with new empirical strategies in Russia itself. It also supports calls for investigating the impact of such thinking on elite attitudes, elite behavior, and ultimately major outcomes of domestic politics or international relations.

Acknowledgments.

For careful comments on earlier drafts, we thank our anonymous reviewers as well as Eric McGlinchey and other participants in the DC Area Postcommunist Politics Social Science Workshop based at George Washington University’s Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies (IERES). We also thank Pål Kolstø and Helge Blakkisrud for the NEORUSS project that produced the main data used for this project.

Disclosure.

Authors have nothing to disclose.

Supplementary Materials.

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/nps.2019.125.