A plaque mounted on the wall of the Eagle pub, close to the former building of the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, commemorates the moment on 28 February 1953 when Francis Crick made his entrance, proclaiming that he and Watson had ‘found the Secret of Life’.Footnote 1 The thesis of this paper is that Crick's enthusiastic boast should be taken seriously. The ‘secret of life’ was not just an eternal and timeless question. It was also an urgent and particular issue for the deeply fractured intellectual elites of scientists and literary intellectuals of early Cold War Britain. Many scientists favoured strictly materialist and antireligious interpretations of life; contesting these were writers for whom life had an essentially spiritual dimension. The model of DNA's structure now in the Science Museum can therefore be seen as a relic of a major cultural confrontation, and not just a statement about an important molecule.

This paper is a work of synthesis which attempts to join two established historical discourses. The paper begins with a summary of the discussions of vitalism and materialism that took place between the First World War and the 1950s. To that debate, this paper links the broad discussions about the cultural objectives of molecular biology that were coincident with the early days of modern DNA science, and shows how, through the arguments of people such as Crick himself and of Jacob Bronowski, perceptions of molecular biology were intimately bound into the longer-term disputes over vitalism. Finally it suggests that this understanding of molecular biology as part of the public sphere, even in its youth, helps us read the large model of DNA built in 1953 which, reconstructed, sits in the Science Museum today.

As Frank Turner and Peter Bowler have shown, in the early twentieth century the debates between science and religion in Britain had taken a new turn.Footnote 2 Previous arguments over evolution gave way to a renewal of the ancient debate over materialism and vitalism which acquired new significance in the wake of the Great War.Footnote 3 Religious believers mourning their dead were comforted by thoughts of meaning, of life eternal and of self-sacrifice. To others, the emergence of the Soviet Union gave hope for a new age, a new economy and a new culture here on earth. European societies, then, were sharply divided between conservatives with strong religious views and modernizers keen to disenchant the world.Footnote 4 For both groups the questions of life and matter were far from abstract.

The newly sharp edge to this issue can be seen in the different tones of the Gifford lectures on science and religion presented by the leading Conservative politician Arthur Balfour in 1914 and, again, in 1922. The publication of the post-war lectures, unlike their predecessors, was prefaced by a ‘prologue’. This introduction reflected on the changing times, the revolution caused by the war, the dominance of technology in everyday life and the wonderful findings of science. A former prime minister and recent negotiator of the Versailles treaty, Balfour was concerned not so much by doctrinal disputes over such matters as the age of the Earth as by competition for the hearts of his audience. He introduced his readers to the thought ‘that some part at least of the alleged “conflict between Theology and Science” is not a collision of doctrine, but a rivalry of appeal; and that so far as Science, or rather scientific Naturalism, is concerned, the strength of that appeal is largely modern’.Footnote 5

Balfour's elegant turn of phrase belied the intensity of the divides then appearing in Britain and expressed in a fierce and widespread debate over vitalism. In contrast to the belief in a special spark of life espoused by religious communities, typically, the biochemical community had advanced materialist interpretations. Thus the meeting, in 1928, of the British Association for the Advancement of Science had been dominated by talk of new findings that might challenge the concept of an immaterial soul. So public was the debate, and so excited were the scientists, that the London Times could report the failure to reach resolution itself as ‘news’: ‘Science and life. Ancient mystery unresolved’.Footnote 6 More hopefully, on 28 September, the New York Times reported on the British Association meeting: ‘England stirred by theories on life’.Footnote 7 Two days later, the science editor Waldemar Kaempffert devoted more than a double-page spread to an article which began, ‘What is life? Can we create it in the laboratory?’. Biochemist F.G. Donnan was quoted as predicting on the basis of recent discoveries that the synthesis of living cells was coming nearer. The next year, the London Times report of the meeting, held in South Africa, also focused on discussions of the nature of life.Footnote 8 Biochemists had come to be associated with materialism.

At a time when the physics of the very small and the very fast was turning out to be rather different from the physics of everyday scales, ‘materialism’ was not necessarily to be equated with a ‘reductionism’ that would reduce biology to chemistry and physics. Many scientists believed that the very complexity of biological systems created unique contexts for the operation of scientific laws. Roger Smith, looking at the work of Sherrington and Julian Huxley, has shown how scientists reflecting on the complexity of life took part in a broader intellectual discourse: each, in his own way, saw a special quality in life arising from its complexity, even though they were materialists. Even Schrödinger's What Is Life of 1944 has been shown by Robert Olby to reflect the vision of a non-reductionist physicist who expected to find novel laws ruling the formation of life.Footnote 9

At the same time, there were many people, such as Balfour, for whom any materialist mindset, with its denial of the divine presence, was itself to be condemned. Attitudes to science in student circles provide an interesting guide to wider debates amidst their peers. Debates in the Oxford Union, for example, were indeed used to indicate the climate of opinion at the time, and the famous 1932 decision not to fight for ‘king and country’ has been much cited as an indicator of a wider mood of pacifism.Footnote 10

Patterns of undergraduate journalism and debate also provide an indicator of the tension within the educated classes between those for whom science's achievements were to be celebrated and those for whom they seemed a darkening threat. Jacob Bronowski, a literary mathematics student, co-founded and edited in November 1928 an undergraduate magazine with the positive title Experiment. The first issue contained just one article on science, titled ‘Biochemistry’.Footnote 11 Other supporters of the magazine were the future film-makers Humphrey Jennings and Basil Wright, while the cover was designed by Misha Black, later to be a most distinguished industrial designer but then known as the younger brother of the treasurer, mathematician Max Black.Footnote 12 These people would work together for a generation.

In competition with Experiment, a more arty magazine, Venture, was established the same month. Its founders – student and actor Michael Redgrave and his friend Robin Fedden, with the collaboration of the art historian Anthony Blunt – would be as distinguished as the competition. Julian Bell, an undergraduate student of English, son of Vanessa Bell and nephew of Virginia Woolf, was closely associated with Venture and he also spoke in support of a motion at the Cambridge Union on ‘The sciences are destroying the arts’.Footnote 13 Although that motion was heavily defeated, Bell himself had spoken eloquently. He dismissed businessmen as ‘the waste-product’ of science. Within a few years he would be dead. Killed fighting for the Republicans in Spain, he would not have a chance to make his own name. Nonetheless the talent and future distinction of many of his contemporaries should dissuade us from dismissing their arguments on grounds of their youth.

It was not only within the ancient universities that concerns over the claims of science were raised. The analyst of science fiction Mark Hillegas has discerned a ‘broad cultural movement which, gaining momentum in the twenties and thirties, turned from dreams of reason, progress, science and the perfectibility of man to tradition and the doctrine of original sin’.Footnote 14 Famously, the Bishop of Ripon argued in 1927 that science was moving so quickly that a ‘science holiday’ was called for, to allow reflection and social response.Footnote 15 In his examination of the debate in early twentieth-century Britain over whether science and religion could be reconciled, Peter Bowler shows in detail how the debate over the validity of any non-scientific views came to be polarized in the late 1930s.Footnote 16 Behind strictly local factors was an increasingly fractious global political context, with the competing attractions of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany expressed in such conflicts as opposing views over the Spanish Civil War. This debate reflected such tensions, the internal dynamics of the debate and also the acerbic leadership of such potent writers as Hillaire Belloc and G.K. Chesterton on the religious side and, opposing, an outspoken cohort of public scientists.

The reductionist biologists

A generation of scientists younger than J.S. Haldane were beginning to assert themselves in the 1930s. Several were hard-nosed reductionist materialists, for whom the idea of an organism being different from a chemical was vitalistic claptrap.Footnote 17 In the early years they were led by J.S. Haldane's son, John Burdon Sanderson (JBS), who had reacted against his father's holism. A man who had particularly enjoyed fighting in the recently concluded First World War, ‘JBS’ began ‘Daedalus’, his 1923 reflection on the potential of science, with the evocation of a 1915 battle. The main protagonists seemed to be the big guns rather than men: ‘One would rather choose those huge substantive oily black masses which are so much more conspicuous, and suppose that the men are in reality their servants, and playing an inglorious, subordinate, and fatal part in the combat.’Footnote 18

In ‘Daedalus’ Haldane dismissed opponents as looking at innovators as heretics. He enthused about the possibility of biological innovations, such as ectogenesis – which he was sure would be considered ‘blasphemy’. Famously this inspired the riposte of his friend Julian Huxley's brother Aldous – the novel Brave New World. As another member of the ‘visible college’ of left-wing scientists, Haldane's friend the embryologist Joseph Needham pointed out in a review that Huxley had got the biology right.Footnote 19 J.B.S. Haldane would be converted to communism during the 1930s, like many other biochemists for whom the science of socialism and biology were identical.

In the pantheon of materialist biologists, J.B.S. Haldane was, in turn, closely associated with his younger contemporary, the crystallographer known generally as ‘Sage’, John Desmond Bernal. The historian and philosopher Stephen Toulmin expressed Bernal's influence thus in an article in the New York Review of Books:

In the 1930s, indeed, Bernal became for a while a major intellectual influence. Though it was the poets of the Popular Front era (Auden, Spender, Day Lewis) who took the public eye, the real focus of radical thought in the Britain of the time was among the scientists of Cambridge, and the man at the center of it all was J.D. Bernal.Footnote 20

A young man in the 1920s, and too young himself to fight in the First World War, in 1929 Bernal published his heretical work The World, the Flesh and the Devil. The words of the title knowingly chosen by this lapsed Catholic were drawn from the list of potential sources of evil specified by the Counter-Reformation Council of Trent. For Bernal, the list served as provocative headings for the challenges posed by science. He even reflected on a future when man would transcend this Earth and escape to the stars. Humanity would be freed too of the limitations of the natural materials from which we are made; it is incidentally ironic that Bernal's wife Eileen was a close friend and correspondent of that arch-opponent of scientism, Julian Bell, the two allied in their love of the biochemist Antoinette Pirie, hatred of fascism and passion for correspondence. They could, however, not agree on Eileen's materialism and fervent Marxism.Footnote 21

Bernal's disdain for religion did not make him an enemy of art or of aesthetics.Footnote 22 It did resonate, however, with a scorn for belief in the immaterial. Bernal was fond of quoting Engels that life was the mode of existence of albumen. He inspired his followers in the search for a chemical basis for living processes. Max Perutz, first director of Cambridge's Laboratory of Molecular Biology and Francis Crick's doctoral supervisor, would recall his first encounter with Bernal, his own supervisor-to-be: ‘I asked him: “How can I solve the secret of life?” He replied: “The secret of life lies in the structure of proteins, and X-ray crystallography is the only way to solve it.”’Footnote 23 In the same year as this conversation, 1936, Bernal emphasized his materialist interpretation in an article for the Marxian journal Science and Society: ‘The practical scientists of today are learning to manipulate life as a whole and in parts very much as their predecessors of a hundred years ago were manipulating chemical substances. Life has ceased to be a mystery and has become a utility.’Footnote 24

Bernal, more than any other single individual, inspired a British school of what would come to be called ‘molecular biology’. At the same time an American school fostered by the Rockefeller Foundation was exploring how biological processes could be understood at the molecular scale. Between these two different but complementary networks, there were a number of historic meetings. For instance, in 1938 the Rockefeller foundation organized a meeting in the Danish town of Kampenborg on molecular biology. There were four British participants: Bernal, Conrad Waddington, Cyril Darlington and William Astbury. After the Second World War, the first three would all write fiery books about the nature of life.Footnote 25 The influence of each of these men through their writings and their students was considerable. Reflecting on the discipline as a whole, Fuerst has argued in a finely wrought 1982 article that the molecular biology which emerged in the post-war era rested on a reductionist belief system.Footnote 26

The humanist response

An answer to Bernal and his protégés was hurled back by Oxford ‘Christian humanists’ who had been scarred by the experience of the First World War and interpreted the nature of evil during the Second World War. The title ‘humanism’ was bitterly contested at the time. The name by itself was used by those such as the atheist philosopher Bertrand Russell for whom man rather than any God was the source of morality.Footnote 27 But another group also claimed the title ‘the Christian humanists’. For them the needs and qualities of man should be the measure of nature, not the other way around.Footnote 28 Balfour had concluded his 1922 lectures with the reflection that humanism could not be divorced from theism. From the 1920s, the views of such writers were deeply coloured by recent wartime experience. The anglo-Catholic T.S. Eliot penned The Waste Land. The Roman Catholic J.R.R. Tolkien vividly described the terrifying warrior half-visible ‘ringwraiths’ said to be based on the ghostly images of men half alive returning to their trenches from an assault.Footnote 29

Such writers as Tolkien, and his friend and Oxford colleague C.S. Lewis, were the legitimate descendents of the poet and philosopher Samuel Taylor Coleridge, both in the quality and impact of their writing and in their theistic interpretation of life. Their visions transcended the bounds of their own time, casting back to a more attractive medieval world and making claims on the future. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the thunderous responses of Tolkien and Lewis to the challenge of the modern technocrats still resonate.Footnote 30

There is a huge literature analysing the work of both Lewis and Tolkien. Its scale and scholarship assert the significance of their works to other intellectuals and their serious intent behind what might seem to be fantasy.Footnote 31 These two writers were linked by vocation, by friendship and by shared experience of the Great War and of the suffering it had inflicted. While neither writer was against science per se, both were suspicious of its claims and of the impacts of applied science. So while Lewis was impressed by the possibilities of the literary genre pioneered by H.G. Wells, he was also very wary of the Wellsian technocratic philosophy.Footnote 32 In a 1954 letter, Lewis explained that That Hideous Strength was about ‘Grace against Nature and Nature against Anti-Nature (modern industrialism, scientism and totalitarian politics)’.Footnote 33 Tolkien too was appalled by the same three demons. The Nature editor Henry Gee has worked hard to demonstrate that he was not ‘against’ knowledge per se, but certainly The Lord of the Rings is very much a romantic reaction against modern industrial life.Footnote 34 Intertwined within its tales of daring and adventure are portraits of evil and polluted industrial worlds, and speeches articulating a wicked materialism expressed by the evil wizard Saruman.

Meeting in the Eagle and Child pub in the centre of Oxford, the friends – J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Warren Lewis (the brother of C.S.) and Charles Williams – together with such followers and students as Roger Lancelyn Green, took the name ‘the Inklings’. From the 1930s to the early 1950s this loose cabal discussed literature and retaliation against the forces of scientism.Footnote 35

Lewis addressed himself, explicitly, to the reductionist materialist challenge raised by Bernal and Haldane. In 1943 he presented the Riddell lectures at Durham on the subject of the ‘Abolition of man’. In this study of values and education he put his argument that ‘what we call Man's power over Nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other Men with Nature as its instrument’.Footnote 36 Lewis also expressed his views about the reduction of humanity to Nature in a more popular genre. His science fantasy books and particularly That Hideous Strength of 1945 were a direct response to Bernal's vision of man escaping the planet. Even the more apparently child-oriented books in the Narnia series have recently been interpreted in terms of Lewis's preference for a medieval world view.Footnote 37

That Hideous Strength tells the story of naive scientists associated with an organization called ‘N.I.C.E.’, the National Institute of Coordinated Experiments, who allow themselves to be manipulated by evil power-hungry men.Footnote 38 A Bernalian figure is given the words ‘If Science is really given a free hand it can now take over the human race and re-condition it: make man a really efficient animal’. Miraculously, N.I.C.E. is destroyed by Merlin reborn, supported by lovers of trees and flowers, and real and lovable animals. In case this book is seen wrongly as a piece of whimsy, the sceptic is pointed to the more obviously scholarly The Abolition of Man, which made the same points: by removing meaning, science has left the way open for evil. As Bowler points out, Lewis's image of Weston, the liberal scientist converted into the devil in Perelandra (preceding That Hideous Strength in Lewis's trilogy), is an iconic image of ‘the changed relationship of science and religion in the Britain of the 1940s’.Footnote 39

The scientists recognized the attack. In the new communist literary magazine the Modern Quarterly, J.B.S. Haldane reviewed Lewis's science fiction, accusing the writer of ‘pandering to moral escapism by diverting his readers from the great moral problems of the day’.Footnote 40 Nonetheless, the Modern Quarterly was quite happy to focus upon the origins of life as a major issue. An article on the topic published just a few months after the end of Second World War, in spring 1946, had evoked so many responses that there was a special discussion of it in the autumn edition.

The 1950s debate

The polarization between materialists and deists that had been so evident before the war survived well into the 1950s. The Oxford Inklings continued their meetings, publishing their best-known works: Lewis's Chronicles of Narnia were published between 1950 and 1956, while Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings appeared between 1954 and 1955. Their competitors continued to be persons who mixed science, left-wing politics and materialist antireligious views.

Science's ambitions were made visible in the culture of the 1951 Festival of Britain, symbolized by the soaring Skylon and by the Dome of Discovery. Becky Conekin, the design historian, has suggested that the exhibition was intended from its first conception to integrate the arts and science.Footnote 41 But in so far as it did, this integration was on science's terms. Several of the most influential figures in its conception had been involved in the pre-war Cambridge magazine Experiment. Misha Black, a founding editor, was a key designer; Humphrey Jennings and Basil Wright made films for the Festival; and Jacob Bronowski wrote the text of the science exhibit.

Conekin has suggested that the Festival represented a Labour Party vision of ‘new Britain’. To this, she opposes the Conservative vision of what was sometimes called, evoking England's defiance of Philip II of Spain and, later, the name of the new Queen, ‘the new Elizabethans’. Certainly the Conservatives loathed the Festival of Britain and arranged for its demolition as soon as they came to power. Moreover, as Conekin points out, such promoters of the ‘new Elizabethan’ image as the journalist and author Sir Philip Gibbs would express a lyrical love of old England and a dislike of modernism and bureaucracy.Footnote 42

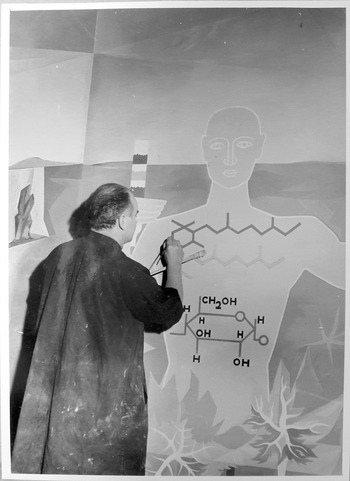

By contrast to the imagery of ‘deep England’ conjured by Gibbs, the dominant designs of the Festival of Britain were derived from crystallography. Electron-density maps of insulin exemplified the new aesthetic. The question of ‘life’ was also addressed. Max Perutz, pupil of Bernal and supervisor of Crick, was responsible for a section of the exhibition, labelled alternatively ‘Problems of life – structure of proteins’ or ‘Physical and chemical approach to life’, displayed in the science annexe, in the new western extension to the Science Museum, South Kensington. It featured a large mural commissioned from the modernist but Romantic artist Peter Ibbetson, forthrightly entitled The Problem of Life in the catalogue to an exhibition dedicated to Ibbetson's work held at London Little Gallery in 1949. Ibbetson's inspirations were identified as William Blake and Gerald Manley Hopkins.Footnote 43 The combination of his Romantic style with a materialist message was particularly powerful. Perutz's script explained that ‘scientists find it useful to leave out the idea of vital force and to think of a cell as a complex system of chemical, mechanical and electrical devices, a kind of clockwork of great complexity’.Footnote 44 This high-profile and, at that time, unusual intervention by a scientist into the public sphere highlights for us the authenticity of Perutz's later autobiographical memories of his early interest in the scientific challenge of life.

Figure 1. Peter Ibbetson working on The Problem of Life mural at the 1951 Exhibition of Science, Festival of Britain at South Kensington. Courtesy: National Archives UK.

At the same time as they were ideologically opposed, writers and scientists were socially and geographically intermingled. The close relationship between Eileen Bernal and Julian Bell shows just how intimate were the members of the two groups. When C.S. Lewis published his science fantasy Perelandra, he was challenged by the science enthusiast Arthur C. Clarke and a correspondence and meeting ensued.Footnote 45 Aldous Huxley, the dystopian novelist, was the brother of biologist Julian Huxley, close collaborator of ‘JBS’ Haldane. His pre-war Brave New World was widely seen as having continuing relevance in the 1950s. In 1956 the Sunday Times printed three long articles by the novelist himself reflecting on how Brave New World looked a quarter of a century on.Footnote 46 Naturally, such close interactions within Britain's intellectual elite made its members all the more aware of the challenge posed by the other side. It led to instant irritated responses such as Haldane's published response to Lewis and indeed to an unpublished reprise by Lewis. This was the atmosphere in which words and symbols such as ‘soul’ and ‘protein’ and soon ‘DNA’ would become ideological weapons.

This section, and the last, have suggested that for thirty years the views of British intellectuals about life had been deeply polarized. There were those who believed that understanding should begin with the human being, ‘holistically’ understood, an ethical, an aesthetic and a spiritual being. By contrast there were those who believed that this was sentimental rubbish and that living beings could be understood at the molecular level. Before the war, the division was most evident as a political split between the communist left and the religious right. As the Festival of Britain had shown, the divide continued. Perutz's treatment of life in the festival demonstrated its ferocity even without the previously vehement political overtones.

Francis Crick, Bronowski and the two cultures

There was little doubt from which direction both Francis Crick and James Watson approached religion. Watson has frequently expressed his scepticism.Footnote 47 I shall, however, focus on Crick, whose intellectual trajectory through English life from the late 1940s to the 1960s would clearly locate the significance of the double helix and of molecular biology more broadly.Footnote 48 He would later remember his intellectual trajectory as he plotted his future:

Quickly I narrowed down my interests to two main areas: the borderline between the living and the nonliving, and the workings of the brain. Further introspection showed me that what these two subjects had in common was that they touched on problems which, in many circles, seemed beyond the power of science to explain. Obviously a disbelief in religious dogma was a very deep part of my nature.Footnote 49

Crick's first hope on entering academic science after a wartime career in magnetic and acoustic firing mechanisms for mines was to study with Bernal. However, he was directed by his advisers towards Cambridge, where he ended up as the pupil of Bernal's student Max Perutz. Crick was too young, perhaps, to enter into a direct conflict with Lewis and Tolkien. However, as we have seen, the nature of life had already been defined as the critical point in the conflict between Christian humanists, for whom the secret would ever remain a mystery, and advocates of science, for whom decoding the ‘secret’ was an exciting challenge. I therefore argue that Crick's boastful cry as he entered the Eagle – that he and Watson had ‘found the Secret of Life’ – should not be seen merely as the proud claim of stealing victory from the establishment competitor Linus Pauling, who – as Pnina Abir-Am has shown – had already defined the issue of decoding the units of heredity in terms of the secret of life.Footnote 50

It is too simple to interpret Crick's expression merely as the whoop of joy of a young man who had beaten an elder. His autobiographical reminiscences, his lineage as a pupil of Perutz and self-confessed grand-pupil of Bernal, and his own ongoing assault on humanists suggest that he was well aware of the cultural current in which he swam. Robert Olby, Crick's biographer, reports a May 1953 interview he gave to the journalist Peter Richie Calder, which appeared on the front page of the liberally oriented News Chronicle newspaper under the title ‘Why you are you. Nearer the secret of life’.Footnote 51

Crick's combative views on molecular biology and religion were expressed in a BBC World Service broadcast in 1960. This talk, given just a few years after the decoding of the double helix, was a strong denunciation of people who wanted to see something special about living beings. It began with a disparaging swipe at a young woman he had met at a dinner party who emphasized that she did not eat living things. He then explains, ‘It's the aim of the modern science of molecular biology to explain living things in terms of atoms and molecules and their interactions; that is in terms of physics and chemistry.’ As an afterthought the typed text was amended in pen to read,

It now seems very probable that the understanding of living things in terms of atoms and molecules will be essentially complete before the Royal Society celebrates its next centenary, and with that understanding man's whole view of himself – of his nature and of his place in the universe – will be radically changed. And a good thing too, considering all the superstition which still permeates our whole society.Footnote 52

Crick expanded on his views at greater length in a 1966 lecture series published as Of Molecules and Men.Footnote 53 His lectures were a vehement assault on vitalism (the series itself was entitled ‘Is vitalism dead?’). He re-emphasized points which have been repeated throughout this paper. In a letter to Conrad Waddington, who had attended the pre-war Kampenborg conference and had produced his own book entitled The Nature of Life in 1961, he expressed his total agreement on the issue of vitalism.

Crick went further, however. In Of Molecules and Men he located himself in the newly rearticulated conflict between the arts and the sciences: the two cultures. This is, of course, symbolized by the work of C.P. Snow; however, the intervention of Jacob Bronowski shows that the issues were rather deeper than the debates between Snow and Leavis might suggest. In Of Molecules and Men, Crick was certainly happy to endorse Snow's ‘two-cultures’ argument, but complained,

The mistake he [Snow] made in my view was to underestimate the difference between them. The old, or literary culture, which was based originally on Christian values, is clearly dying, whereas the new culture, the scientific one based on scientific values, is still in the early stage of development, although it is growing with great rapidity.Footnote 54

This distinctively future-orientedness of science had, as we have seen, been debated for a generation; it was also coming to a head in late 1950s Britain. As Guy Ortolano has recently reminded us, there was then an attempt to introduce the modernism of science not just into cultural but also into political discourse. Labour party leader Hugh Gaitskell convened the so-called ‘Gaitskell group’ of left-leaning scientists including Bernal, C.P. Snow, Patrick Blackett and Jacob Bronowski.Footnote 55 At this critical moment in the Cold War, scientists were associated with socialism and the future. It was in this environment that Snow had pushed the issue onto the public stage with his 1959 Rede Lecture on ‘The two cultures’. If scientists for Snow ‘have the future in their bones, then the traditional culture responds by wishing the future did not exist’.Footnote 56 The proximity of this view to Crick's later expression was matched by a telling change in the second edition of Snow's Two Cultures, published in 1964. There, in identifying the critical masterpiece of science of which every citizen should be familiar, he replaced the second law of thermodynamics cited in the first edition by an understanding of DNA. Snow wrote, ‘This branch of science is likely to affect the way in which men think of themselves more profoundly than any scientific advance since Darwin's – and probably more so than Darwin's.’Footnote 57 Both Crick and Snow were founding fellows of Cambridge's new scientific college Churchill College in 1958, and a typescript of the second edition of Snow's Two Cultures is to be found in the Crick papers.Footnote 58

Snow's argument famously met with vehement opposition. Critique and author were jointly condemned, and indeed abused, by the Cambridge English don F.R. Leavis. He saw Snow's argument entirely in terms of academic disciplines, the misplaced assault of the scientists upon the humanists, and the incompetence of Snow as an author purporting to be able effortlessly to turn his hand to novels. At a time of university expansion and contested ground this reading would strike home. Yet the argument was more fundamental than a mere conflict between disciplines for resources.

The high cultural stakes were highlighted by the approach taken by mathematician, intellectual and Gaitskell group member Jacob Bronowski. In 1962 Bronowski authored a play, ‘The abacus and the rose’, explicitly on the model of Galileo's Dialogue on the Two World Systems, a classic counterposing of the ancient geocentric Aristotelian system against the modern heliocentric model in which man's habitation had been decentred. This ambitious vision of the clash of civilizations was first broadcast on the BBC's Third Programme. Bronowski attempted to show the contrast between the anthropocentric world view of the humanists and the perspective of the scientist. It attracted considerable attention and the dialogue was published with considerable prominence in the American magazine The Nation two years later, and subsequently incorporated with the second edition of Bronowski's Science and Human Values.Footnote 59

There was no doubt in Snow's mind about the significance of this essay. He complimented Bronowski for what he saw as a homage to his argument, writing,

It is a tremendous support. It was gallant and generous of you to weigh in like this, and I shall never forget it. It was a pure chance that you didn't have to bear the major weight of this controversy – as I have repeatedly said both in public and in private. If that had been the case, I hope I should have behaved as handsomely as you have done. It means more to me than I can easily say.Footnote 60

The dialogue is cast as a dinnertime debate between a scientist (Potts) and an English don with a senior civil servant as the genial, if slightly dim, host. For Bronowski, the tension between the modern English don and the molecular biologist was the modern equivalent of Galileo's struggle with the Church. He describes his scientific protagonist Potts as

a little smug, because success came young, and slow to see that there really are other points of view (and interests) than that of the molecular biologist – not yet forty-five, lacking the critical gift of the other two, his sense of mission as sharply positive, as theirs is negative, Irish voice smouldering with idealism.

Bronowski's character ends with a definition of a molecular biologist almost identical in wording to the one given by Crick himself in the 1960 BBC World Service broadcast:Footnote 61 ‘He is a man who unravels the secrets of life by using the tools of physics. He shows – we have shown – that the structures of biology become intelligible when we treat them, not as strings of mysteries, but as strings of molecules.’ There is no need to intuit a parallel with Crick: there is a copy of the Nation article itself in the Crick papers. The Irish accent, of course, did not relate to Crick, but may rather have indicated Bernal.Footnote 62

Harping, Potts's opponent in Bronowski's play, is one of the Angry Young Men whose philosophy also resembles that of the school of D.H. Lawrence.Footnote 63 Bronowski describes him as displaying a ‘puritan anger, but bitter because he feels helpless in a changing time – about thirty-five, Reader in English at Southampton, say, Midland voice of preacher with cutting edge’.

The debate between the two men hinges on the nature of beauty. To the scientist Potts, a sunset was in itself beautiful. On the other hand, Harping argues that the discoveries and observations of scientists are banal and without depth while he and his colleagues are concerned with the deeper expressions of the human spirit. Here, Bronowski had not in fact made a novel point, even in terms of his own biography. He was harking back to a debate aired in the very first issue of his youthful publication Experiment.Footnote 64 Before that it had been explored in The Riddle of the Universe by the German Darwinist, materialist and founder of the philosophy of monism Ernst Haeckel. In Germany, this work had been seen as a bible for those with a materialist world view, and even in Britain it was widely known. J.B.S. Haldane had been inspired by it as a boy and later described himself as a monist. Haeckel described the issue of beauty as the point of ‘strongest opposition’ between Christianity and his ‘religion’ of monism.Footnote 65 He distinguished between the naturalistic (Haeckel's emphasis) century of the present and the past anthropistic centuries dominated by Christianity.Footnote 66 This distinction between past and present, earlier evoked by Balfour, of course, was exactly that being made by Bronowski on behalf of Crick, and a few years later by Francis Crick himself in Of Molecules and Men.

The argument in this section has not been dependent on a close psychological reading of Francis Crick. Nor have I attempted to interpret an ambition to solve a scientific puzzle in terms of culture. Rather this section has suggested that attitudes to life were polarized at the time. Crick was well aware of the polarization and located himself clearly with respect to it. Although his documents from the early 1950s are rather sparse even in 1953, we have evidence of the interpretation of the double-helix decoding in terms of life: Watson's evidence of his whoop of joy, the letter to his son and the Ritchie Calder article. From 1960 onwards the evidence is indeed stronger: the BBC broadcast and his own Danz lectures. Most interestingly the Bronowski play locates molecular biology within the debate over the centrality of the human experience.

The model

Crick's confident assertion that he could now show his solution to the riddle of life had been precipitated by the successful building of the model of DNA and the explanation of its replication. He and Jim Watson had managed to build a small model which explained the crystallographic evidence of Rosalind Franklin, received via Maurice Wilkins. Shortly after this first model, Crick and Watson built other models. One, in particular, was as large as a man. This was seen by a Rockefeller Foundation official in April 1953 and exhibited at a Cavendish Laboratory open day a few months later. The model assured viewers of the elegance and hence the likely ‘truth’ of the young men's scientific interpretation.Footnote 67 From a strictly analytical point of view, its great scale of construction was extravagant, unconventional and unnecessary. As a rhetorical device in such an environment as a Cavendish open day, however, it was powerful and communicative. Even at the moment of its creation the model was seen as having a public as well as a strictly scientific value.

The next step in the model's entry into the public arena was taken in May 1953. An undergraduate aspiring journalist hoping to sell a story to Time magazine asked his friend, a young freelance Cambridge photographer called Anthony Barrington Brown, to photograph it together with Crick and Watson. Although at the time Barrington Brown felt he had signally failed to get them to stand portentously, he had nonetheless created a now iconic image.Footnote 68 After Watson used two of his shots in The Double Helix of 1968, they came to be widely reproduced. We can see Crick and Watson standing, proudly – if not portentously – with the model, and in the background, mounted on the wall, the diagrammatic structure published in their Nature article.

Figure 2. Watson and Crick with their DNA model. Courtesy: A. Barrington Brown/Science Photo Library.

As interest moved on, the sculptural model came to be treated as ephemeral. It began to break apart and was subsequently dismantled. Nonetheless the majority of its pieces were kept, at first by Cambridge molecular biologist John Kendrew and then by the chemist Herman Watson, who took them when he moved to the Chemistry Department of Bristol University. The Science Museum curator Anne Newmark discovered these surviving pieces in Bristol, and in 1976 Farooq Hussain, a student at King's College, reassembled the existing pieces to re-create a portion of the large model. He added substitute side chains to replace those missing, but like a careful archaeologist left it clear which pieces were original and which substitutions.Footnote 69

Re-created, the model was deposited in London's Science Museum, where it is identified as one of the most important of all the exhibits.Footnote 70 It has been compared by the art historian Martin Kemp to the Mona Lisa and to an ancient Greek vase in its impact on the viewer, its careful reconstruction and its cultural importance, describing it as a ‘treasured cultural icon’.Footnote 71 Chadarevian, in reflecting on the significance of the relic in her account of the reconstruction of the model, suggests that relics ‘are not just tokens of great deeds, but actively contribute to the creation and public celebration of those deeds’.Footnote 72 The use of words such as ‘relic’ and ‘icon’ emphasizes Kemp's point that, like Leonardo's Mona Lisa, the DNA double helix is a ‘super-image’ with a meaning far beyond the narrow band of professional interpreters. Both ‘speak to audiences far beyond their respective specialist worlds, and both carry a vast baggage of associations’.Footnote 73

Figure 3. The DNA model at the Science Museum: a sword from the field of battle. Courtesy: SSPL/Science Museum.

By the 1980s, in an era of biotechnology, the question ‘what is life?’ again had a particular resonance, and displays and broadcasts were used to focus public attention on the issue and on particular resolutions. In that way it may seem to have been presented in the 1980s as a medieval relic of some ancient saint's bones was deployed to wage a contemporary dynastic conflict. As I have argued elsewhere, that is a legitimate and powerful role of the museum exhibit.Footnote 74 There is often the assumption that these powers are acquired by accident long subsequent to their construction, and that they were not anticipated by their originators. However, it is the argument of this paper that the symbolic power was – in its significance, if not in its ultimate strength – indeed intended. It was built as a weapon in the debates of the public world. Chadarevian points out how, according to the 1987 BBC adaptation of Watson's book, ‘the double helix’ is ‘the “secret of life” made visible’. The suggestion here is that this reading was intended even in 1953. The model can therefore be compared with the archaeological remains of a battle. Just as a sword recovered from a field is a forceful reminder of a bloody conflict, so the model is a relic of a particular critical moment in an enduring dispute.

International comparisons

The particular constellation of skills and interests arrayed in Cambridge in 1953 was unique.Footnote 75 Crystallographic expertise, an interest in modelling and contacts with both Chargaff and Rosalind Franklin came together just there, and that alone would explain why DNA could be decoded in Cambridge. It is my core argument that, on top of this concatenation of technical skills and network linkages, Britain's cultural–political tensions at that moment gave a distinctive and high significance to the problem. Historically, equivalents had certainly existed. Engels's dialectical materialism had been influential on the left across Europe and not just on Bernal in Britain.Footnote 76 Among scientists, the philosophy of materialism had been most coherently and influentially expressed by Haeckel through monism. Subsequently, however, during the early twentieth century, in Germany the uses of monism had themselves evolved. The Nazis had drawn upon a racial interpretation of monism while left-wing materialists had been murdered or had fled.Footnote 77

Even in the United States, from where Watson had come and with which the British community had close links, it took different forms. There, the German immigrant Jacques Loeb had promoted a philosophy close to that of monism.Footnote 78 The ground of debate between religion and science was, however, defined by the 1925 Scopes trial over the teaching of evolution. Human evolution, and its management, provided the touchstone of materialism. Over evolution one sees vehement argument, but at the time molecular genetics did not provide exactly the same focus of religious disagreement.

A provocative parallel between the Cambridge achievement and American science was offered within a few months of the decoding of the double helix. In Chicago, Stanley Miller, a student of the distinguished chemist Harold Urey, announced the synthesis of the building blocks of life in the May issue of Science, just eight weeks after the Crick and Watson paper.Footnote 79 A means by which life could have originated through strictly material means had been proposed in the 1920s and 1930s, separately by J.B.S. Haldane and the Soviet scientist Alexander Oparin.Footnote 80 At the time their hypotheses were merely speculative, but following Urey's suggestion Miller had created amino acids by passing a spark through a mixture of carbon dioxide, nitrogen and hydrogen. Since amino acids were the building blocks of proteins it seemed that here was a mechanism for life to evolve without divine intervention. This paper was cited fifty-one times in its first ten years (as measured by the ISI) – a very considerable number, if less than the Crick and Watson total of 471 over the same period.Footnote 81 This work concentrated on proteins and amino acids rather than on nucleic acids, but like Crick and Watson's near simultaneous paper, it seemed to give support to a materialist interpretation of life.

Urey himself was a cosmopolitan politically aware chemist who had campaigned for world government and been a supporter of Republican Spain in the 1930s. At the time of his announcement he had recently defended the Rosenbergs in the New York Times. Urey was, however, no Marxist materialist. Nor did his finding become contentious in the United States.

Although issues over science and religion have turned, in the United States, time and time again, on the status of evolution and of divine creation of man rather than of ‘life’ itself, they did become intertwined with the issues raised by DNA through the ‘man-playing-God’ debate. This has been tracked by the sociologist John Evans, who has mapped and followed in detail the disputes over eugenics, test-tube babies and theology.Footnote 82 The period begins for him with a paper by the British psychiatrist and geneticist Lionel Penrose, who claimed that classical genetics was giving way to a detailed biochemical interpretation. As Evans has shown, from the mid-1960s the question whether molecular biologists were ‘playing God’ became a major theme in the emerging discipline of bioethics. By 1969 Albert Rosenfeld, in his book Second Genesis, could predict ‘Coming: the control of life’.Footnote 83 Above all, the phrase was made popular by the 1977 book by Howard and Rifkin, Who Shall Play God?.Footnote 84

Conclusion

In recent years the debate between Tory and technocrat over the secret of life has been as vigorous as ever.Footnote 85 In Britain, Prince Charles has kept alive the Inklings' spirit at the centre of the nation's establishment. On the other hand, Richard Dawkins has played a role that has evoked the image of a latter-day Crick, moving between explaining the centrality of DNA and denouncing theism.Footnote 86 This paper has suggested that such disagreement should not be seen as new. It is a continuation of a century of argument since the experience of the Great War and the rise of Marxism – over the nature of life and the status of scientific reductionism.

Science has continued to play an important role in this debate over the nature of humanity. The Human Genome Project has built on the nematode worm sequencing project which in its turn is a development of a 1963 idea of Crick's to describe the E. coli cell in its entirety.Footnote 87 As a recent report on so-called synthetic biology points out, ‘One of the core ideas in synthetic biology is the notion of creating “artificial life”. This claim has simultaneously provoked fears about scientists “playing God” and raises deeper philosophical and religious concerns about the nature of life itself and the process of creation.’Footnote 88 On 26 March 2008, the Independent newspaper asked in bold type on its front page, ‘Is this a clump of cells or a living being with a soul?’Footnote 89

This paper has endeavoured to show that it is not just in recent years that such debates over the nature of life have been linked to molecular biology. ‘Monism’ provides a continuing strand. I have shown that at the time of the announcement of the double-helix structure of DNA, the long-running debates over vitalism on the one hand, and over the explanatory potential of a molecular interpretation of life on the other, were still alive. Crick, certainly, endeavoured to use these debates to frame the cultural meaning of DNA even in its early years. The physical model of the double helix now in the Science Museum can therefore be seen as a relic of a peculiarly creative moment in a debate in the public sphere over the significance of life. Today, engagement with the model can still provoke viewers to reflect on their own attitudes to the secrets of life, and the meaning of science.