Background

India accounted for 17.0% of the global burden of maternal deaths in 2015 (WHO et al. 2015). In 2016, the maternal mortality ratio for the country was estimated at 130 per 100,000 live births (NITI Aayog, 2018) – close to twice the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) (Goal 3.1) of 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. Since the launch of the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) in India in 2005, increasing institutional deliveries has been proposed as a solution to reducing maternal deaths (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2005). This is aligned with the goal of improved maternal health and the wider discourse on safe motherhood through biomedical institutional forms of care (Storeng & Béhague, Reference Storeng and Béhague2014). Additionally, skilled attendance at birth has been promoted since 2006 through the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) scheme – a cash transfer programme that provides monetary incentives to women to attend institutions for delivery (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Misra, Diwan, Agnani, Levin-Rector and De Costa2014). As a result of these efforts, there has been a substantial increase in the number of institutional deliveries in India, especially after the launch of the National Health Mission (NHM) in 2013 (National Health Mission, 2017). However, this has not resulted in commensurate improvements in key maternal and newborn health indicators, especially the UN SDG of reducing maternal deaths. One reason for this is that the overemphasis on increasing institutional delivery has concealed women’s negative experiences with the health system in terms of the poor quality of their interaction with institutional health care staff (Jha et al., Reference Jha, Christensson, Skoog Svanberg, Larsson, Sharma and Johansson2016).

Health care providers often behave rudely with pregnant women (National Health Mission, 2017). Evidence of poor, often violent behaviour towards women during labour has been found in high- and low-income settings alike (Bowser & Hill, Reference Bowser and Hill2010; Bohren et al., Reference Bohren, Vogel, Hunter, Lutsiv, Makh and Souza2015; Ishola et al., Reference Ishola, Owolabi and Filippi2017). This can include physical and verbal abuse, violations of privacy, actions that promote stigma and discrimination, and neglect and abandonment (WHO, 2017). Thus, even though delivery in institutional facilities in India rose from 26.0% of total deliveries in 1992–93 to 72.0% in 2009, the quality of maternal care has remained a major concern (UNDP India, 2019).

Violence against women (VAW) is a well-recognised public health issue (Consultation on Violence against Women & WHO, 1996). Violence against women by health care providers during childbirth has been called ‘obstetric violence’, and has instead been variously described as ‘mistreatment’ (Bohren et al., Reference Bohren, Vogel, Hunter, Lutsiv, Makh and Souza2015), ‘disrespect and abuse’ (DA) (Bowser & Hill, Reference Bowser and Hill2010) and ‘dehumanized care’ (Misago et al., Reference Misago, Kendall, Freitas, Haneda, Silveira and Onuki2001) by other researchers. Although these different concepts have distinct definitions and systems of classification of VAW, they all highlight the connection between mistreatment and other forms of gender-based violence: the medicalization of the natural process of childbirth; the roots of VAW in gender inequality; and the threat to women’s rights and health (Savage & Castro, Reference Savage and Castro2017). Moreover, Sadler et al. (Reference Sadler, Santos, Ruiz-Berdún, Rojas, Skoko, Gillen and Clausen2016) suggested that ‘obstetric violence’ is reflective of other forms of marginalization of women, contingent on their location within the larger political economy.

Initially, the movement against ‘obstetric violence’ grew out of a focus on quality of care (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Jerez, Klein, Correa, Belizán and Cormick2018). In 1993 in Brazil, the ground-breaking and influential Network for the Humanization of Labour and Birth (Rehuna) in its founding charter recognized ‘the circumstances of violence and harassment in which care happens’ (Diniz & Ayres, Reference Diniz and Ayres2001). However, the network deliberately did not talk about ‘violence’ and instead favoured terms such as ‘humanizing childbirth’ and ‘promoting the human rights of women’ because it feared a hostile reaction from professionals if it specifically mentioned violence. It was legislation in Venezuela that used the term ‘obstetric violence’ for the first time, describing it as ‘the appropriation of the body and reproductive processes of women by health personnel’ (República Bolivariana de Venezuela, 2007). Here, it was defined as dehumanized treatment and an abuse of medication which converts natural processes into pathological ones, bringing with it a loss of autonomy of women and their ability to decide freely about their bodies and sexuality, negatively impacting their quality of life. Since then, a significant amount of research has been carried out globally on ‘obstetric violence’ and its multiple descriptions (Bowser & Hill, Reference Bowser and Hill2010; D’Gregorio, Reference D’Gregorio2010; Freedman et al., Reference Freedman, Ramsey, Abuya, Bellows, Ndwiga and Warren2014). While attempts to identify what constitutes VAW during childbirth by health care providers have been cognisant of the historical, social and cultural settings, doing so remains complex.

Bohren et al. (Reference Bohren, Vogel, Hunter, Lutsiv, Makh and Souza2015) conducted a systematic review of VAW during childbirth by health care providers and produced a broad, comprehensive categorization with a pressing caveat that there is a lack of standardized, comprehensive and agreed-on typology, identification criteria and operational definitions of the mistreatment of women during facility-based childbirth. The major types of mistreatment by providers outlined in their systematic review were: (1) physical abuse, (2) sexual abuse, (3) verbal abuse, (4) stigma and discrimination, (5) failure to meet professional standards of care, (6) poor rapport between women and providers, and (7) health system conditions and constraints.

Despite increased global inquiry into VAW during childbirth by health care providers, henceforth referred to as ‘obstetric violence’, the literature in the Indian context has remains scattered, and a critical analysis of the existing literature is called for. This integrative review aims to collate and analyse the extant literature on ‘obstetric violence’ in India and analyse the results of empirical research using the comprehensive typology of Bohren et al. (Reference Bohren, Vogel, Hunter, Lutsiv, Makh and Souza2015). The aim is to also highlight results that do not align with any of the Bohren et al. categories, to identify all types of ‘obstetric violence’ in India and compare these with global findings. In summary, the aim is to develop a framework to address the pernicious yet evasive issue of ‘obstetric violence’ in India from a rights-based perspective within the existing structural and social determinants of health.

Literature search

Strategy and selection criteria

PubMed, Google Scholar and JSTOR were searched for peer-reviewed studies on the quality of treatment that women receive during childbirth in health facilities in India. The database search was carried out using the terms ‘mistreatment’, ‘obstetric violence’, ‘disrespect and abuse’ and ‘dehumanized care’, as these all denote the concept of poor treatment of women in childbirth by health care providers. However, a consensus was reached about using the term ‘obstetric violence’ for the review based on the way the Indian movement against this form of VAW has taken shape, in a manner similar to that of Latina midwives effectively resisting medicalization and harmful medical procedures as well as abusive and dehumanizing practices deployed against economically and socially marginalized women in Latin America (Dixon, Reference Dixon2015). For the purpose of this review, therefore, ‘obstetric violence’ refers to any of the terms mentioned above, and all these terms denote the same concept of VAW during childbirth by health care providers. The search was limited to the period 2003–2019 to focus on current operational definitions and methodologies of VAW during childbirth. The last search was carried out on 2nd July 2019.

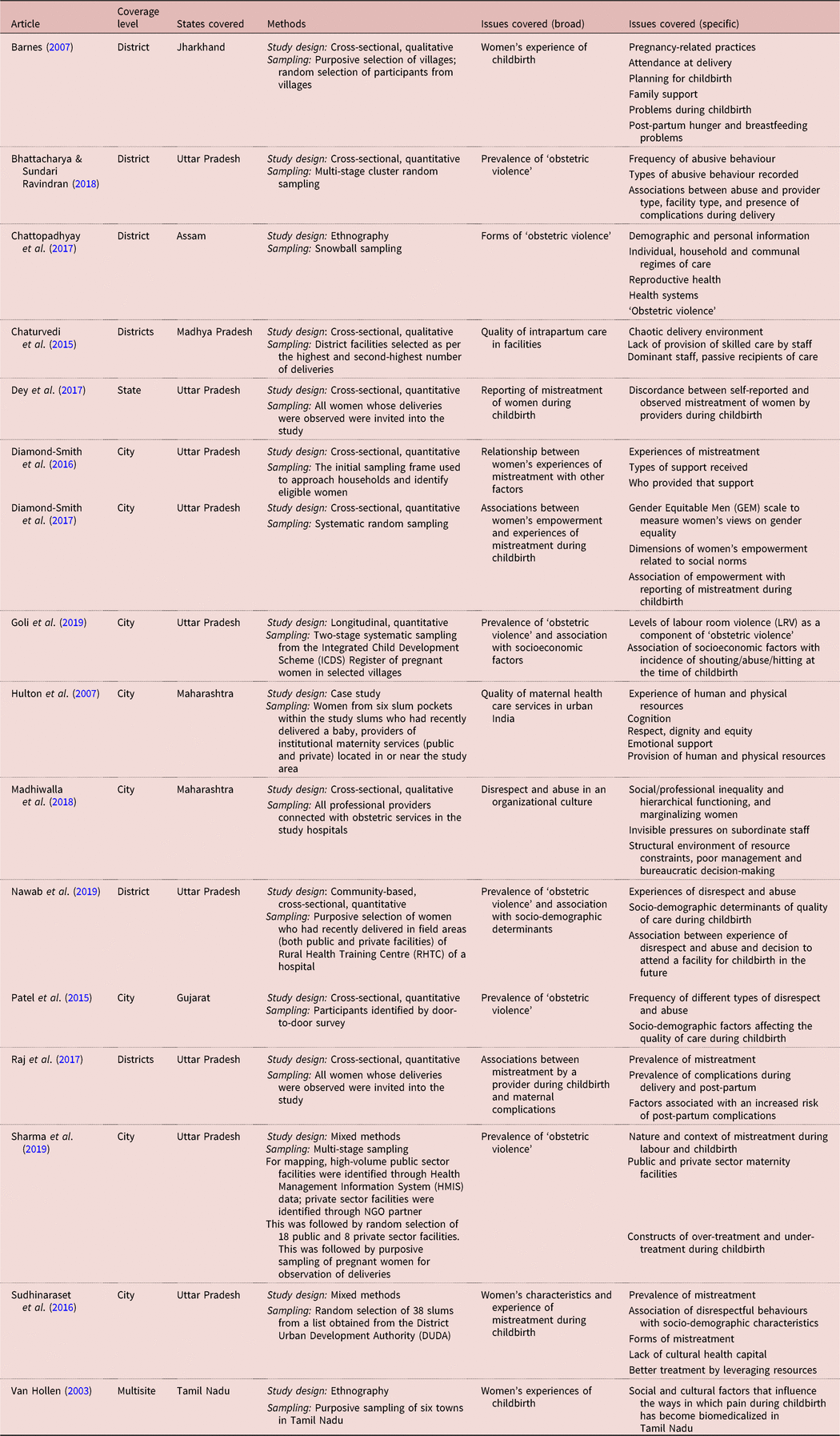

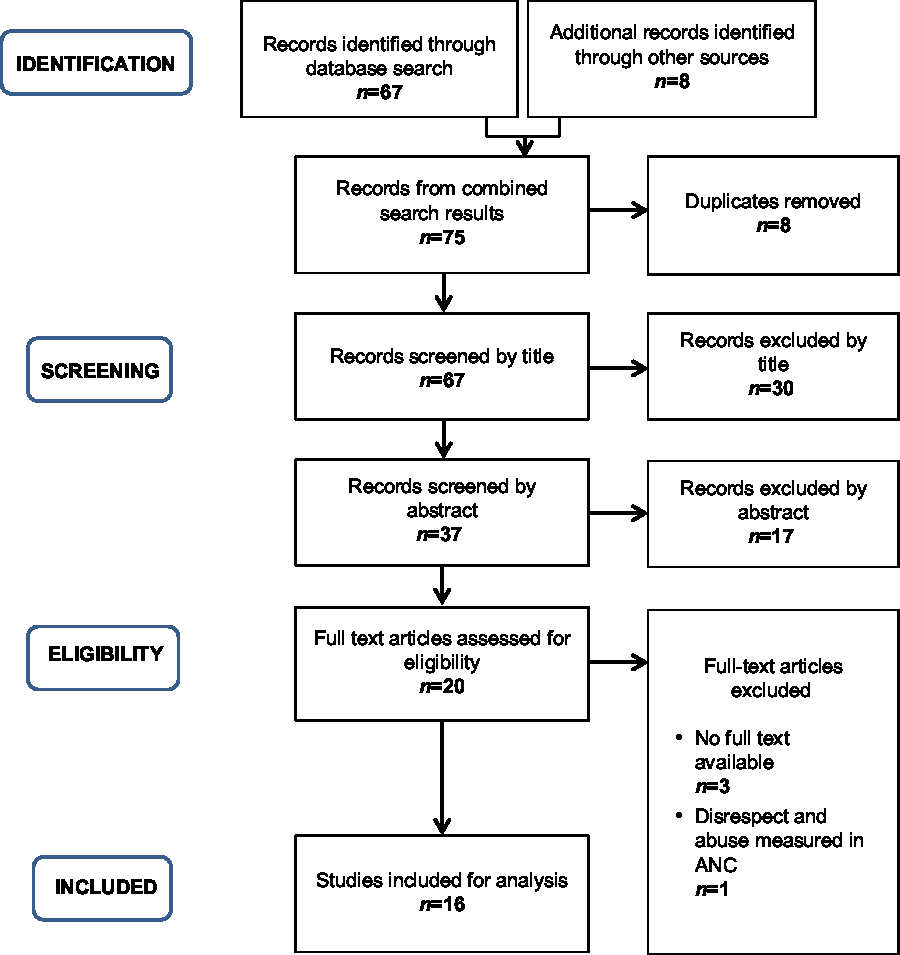

From the initial database search, 67 potentially relevant articles were identified. A secondary supplementary search was conducted where the reference lists of identified articles were checked manually, as well as the ‘grey literature’. A combined total of 75 articles were identified through this process. After removing duplicates, 67 titles were reviewed to check their relevance to VAW during childbirth, on the basis of which 30 articles were excluded. Next, the abstracts of 37 articles were assessed for inclusion criteria, which formed the basis for eligibility. The inclusion criteria comprised qualitative or quantitative empirical research characterizing women’s experience of childbirth in health facilities, written in English, and limited to India. The following outcomes pertaining to VAW during childbirth were examined in each of the articles: the prevalence of ‘obstetric violence’, forms of ‘obstetric violence’, interventions for ‘obstetric violence’, implications for maternal mortality and morbidity, effect on facility-based childbirth, the legal aspects of ‘obstetric violence’ and Respectful Maternity Care (RMC). Abstracts that did not cover at least one of the above-mentioned outcomes were excluded, and 20 articles were finally arrived at for full-text review. Of these, the full text was not available for three articles, and hence they were removed from further analysis. All remaining papers were downloaded, organized and reviewed in Mendeley. The studies were assessed keeping in mind the need to record all explicit and implicit and symbolic and tangible forms of ‘obstetric violence’. One article that focused on measuring disrespect and abuse during antenatal care was excluded. After analysing the full texts for eligibility, sixteen articles were ultimately included in the review, as listed in Table 1. The integrative review process is depicted in Figure 1.

Table 1. Studies included in the review

Figure 1. Process of selecting studies for this integrative review on ‘obstetric violence’ in India.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from each article into a data extraction form for the following: objectives of the study, study setting and study population, sampling details, methods and results/findings/conclusions. The forms were critically examined to merit inclusion. Methodological quality assessment was carried out for each included study jointly by the co-authors. Quality assessment was conducted keeping in mind that the studies should be empirical with details of sampling and strategy, that there should be transparency in the qualitative studies, that data should be coded, that participant characteristics should be given, and that they should comply with ethical guidelines to ensure confidentiality and anonymity. The authors were not contacted for further information.

Data analysis

Owing to the diverse nature of the subject, an integrative review was chosen for analysis (Whittemore & Knafl, Reference Whittemore and Knafl2005). The findings of the included studies were thematically judged, based on the categories outlined in the typology of Bohren et al. (Reference Bohren, Vogel, Hunter, Lutsiv, Makh and Souza2015), namely: (1) physical abuse, (2) sexual abuse, (3) verbal abuse, (4) stigma and discrimination, (5) failure to meet professional standards of care, (6) poor rapport between women and providers, and (7) health system conditions and constraints. As these seven enlisted themes were further detailed by Bohren et al. (Reference Bohren, Vogel, Hunter, Lutsiv, Makh and Souza2015) into second- and first-order themes, the results of the studies included in the review were accordingly scrutinized. One additional theme emerged, namely, harmful traditional practices and beliefs during childbirth. This category was added for data extraction from each included article as ‘harmful traditional practices and beliefs’.

Findings

Physical abuse of women during childbirth

In the selected studies, women reported being physically abused (slapped, pinched or beaten) by health care providers during childbirth (Hulton et al., Reference Hulton, Matthews and Stones2007; Chaturvedi et al., Reference Chaturvedi, De Costa and Raven2015; Chattopadhyay et al., Reference Chattopadhyay, Mishra and Jacob2017; Bhattacharya & Sundari Ravindran, Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018; Nawab et al., Reference Nawab, Erum, Amir, Khalique, Ansari and Chauhan2019; Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Penn-Kekana, Halder and Filippi2019). The extent of physical abuse varied among the different studies, which were conducted in different locations in India: 3.7% in Raj et al. (Reference Raj, Dey, Boyce, Seth, Bora and Chandurkar2017), 5.9% in Nawab et al. (Reference Nawab, Erum, Amir, Khalique, Ansari and Chauhan2019), 15.5% in Sudhinaraset et al. (Reference Sudhinaraset, Treleaven, Melo, Singh and Diamond-Smith2016) and 40.0% in Patel et al. (Reference Patel, Makadia and Kedia2015). A study of public facilities in Uttar Pradesh assessing discordance in self-reported and observational data on the mistreatment of women during childbirth found that the observed prevalence of women being beaten/slapped by a health care provider was 3.7%, while the self-reported prevalence was 0.9% (Dey et al., Reference Dey, Shakya, Chandurkar, Kumar, Das and Anthony2017). A study investigating mistreatment during labour at public- and private-sector maternity facilities in Uttar Pradesh found that the public sector performed worse in terms of physical violence (hitting or pinching) towards labouring woman (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Penn-Kekana, Halder and Filippi2019).

Studies recording physical abuse mentioned that institutional delivery was sometimes perceived as threatening, especially by those who had a prior negative experience. One study reported a woman saying, ‘They tied my legs to iron rods’ (Barnes, Reference Barnes2007, p. 64). Many women reported being scolded and sometimes even physically beaten by medical staff for calling out in pain during delivery (Van Hollen, Reference Van Hollen2003). Madhiwalla et al. (Reference Madhiwalla, Ghoshal, Mavani and Roy2018), in their study on health care providers, noted that providers acknowledged overt violence and justified it by saying that the intention was to protect women and babies. It was also reported that, generally, it was lower-ranked workers, such as sweepers or ayahs, who slapped women (quite often on the inner thighs), while the nurses watched this happen without objection (Chaturvedi et al., Reference Chaturvedi, De Costa and Raven2015).

Sexual abuse of women during childbirth

No evidence of sexual abuse of women by health care providers was found in the studies included in this review. Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran (Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018) noted that their questions on sexual abuse received poor responses from women and that the pilot was helpful in testing the feasibility of asking sensitive questions on disrespect and abuse to a vulnerable group of rural Indian women. Hence, questions on sexual abuse were removed after their pilot study.

Verbal abuse of women during childbirth

Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran (Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018), in their study in the Varanasi district of Uttar Pradesh, found that 17.3% of women reported receiving non-dignified care in the form of shouting or scolding. A much higher prevalence was recorded by Patel et al. (Reference Patel, Makadia and Kedia2015) in their study in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, where 55.0% of participants received non-dignified care in government facilities in the form of verbal abuse. Dey et al. (Reference Dey, Shakya, Chandurkar, Kumar, Das and Anthony2017) measured the discord between the observed and self-reported mistreatment of women in health facilities, and observed the prevalence of providers using bad/abusive language to be 3.0%, while the self-reported prevalence was 2.6%. The same study found the observed prevalence of a provider threatening to slap a client as 3.2%, and the self-reported prevalence as 2.2%.

The prevalence of women reporting that they were threatened or humiliated through rude sexual remarks in public was recorded at 6.3% (Bhattacharya & Sundari Ravindran, Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018). Derogatory insults related to women’s sexual behaviour were reported by 19.3% of the participants (Bhattacharya & Sundari Ravindran, Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018). Women also reported verbal abuse when they were expressing pain: ‘When there was pain I would shake, and all the nurses would abuse me’ (Barnes, Reference Barnes2007, p. 64). Women reported verbal abuse during labour and noted that sometimes the shouting was directed at accompanying relatives (Chattopadhyay et al., Reference Chattopadhyay, Mishra and Jacob2017).

Stigma and discrimination during childbirth

A study conducted in an urban slum of Ahmedabad in Gujarat found that 33.2% of women reported discrimination during childbirth (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Makadia and Kedia2015). Another study conducted in public health facilities in Uttar Pradesh recorded the prevalence of discriminatory behaviour towards women by health care providers to be 9.7% (Raj et al., Reference Raj, Dey, Boyce, Seth, Bora and Chandurkar2017). The same study also found that 2.3% of the participants were treated differently than others because they were from a particular community/social class. The results from a longitudinal study in urban and rural areas of Uttar Pradesh showed that obstetric violence was significantly higher among Muslim women (OR = 1.8; 95% CI = 0.7–4.3) compared with Hindu women (Goli et al., Reference Goli, Ganguly, Chakravorty, Siddiqui, Ram, Rammohan and Acharya2019).

Another study assessing the association between disrespect and abuse and socio-demographic factors found that women of low socioeconomic status (SES) were over three times more likely (OR = 3.68; 95% CI = 1.4–9.7) to have experienced disrespect and abuse than those of high SES (Nawab et al., Reference Nawab, Erum, Amir, Khalique, Ansari and Chauhan2019). This aligns with findings from a longitudinal study in Uttar Pradesh, which found that rich women were nearly half as likely (OR = 0.65; 95% CI = 0.16–2.59) to experience ‘obstetric violence’ as poor women (Goli et al., Reference Goli, Ganguly, Chakravorty, Siddiqui, Ram, Rammohan and Acharya2019). In contrast, Diamond-Smith et al. (Reference Diamond-Smith, Treleaven, Murthy and Sudhinaraset2017) found that being in the richest (compared with the poorest) wealth quintile was significantly associated with reporting mistreatment during childbirth (OR = 3.268; p < 0.01).

Assessing self-reported mistreatment in public facilities in Uttar Pradesh, Dey et al. (Reference Dey, Shakya, Chandurkar, Kumar, Das and Anthony2017) found that 1.4% of women felt that they were discriminated against during their stay in the facility, and 0.6% said they were treated differently based on their caste. Diamond-Smith et al. (Reference Diamond-Smith, Treleaven, Murthy and Sudhinaraset2017), in their study in birth facilities in the slums of Uttar Pradesh, found a statistically significant difference in the mistreatment of women by caste, with nearly 72.0% of those from scheduled tribes (STs) and 63.52% from scheduled castes (SCs) reporting mistreatment, compared with only 30–40% in other castes. In line with these findings, Goli et al. (Reference Goli, Ganguly, Chakravorty, Siddiqui, Ram, Rammohan and Acharya2019), in their study in Uttar Pradesh, found that the odds of ‘obstetric violence’ in SCs were half of those among the general category (OR = 0.5; 95% CI = 0.1–1.5) and among other backward classes (OBC) (OR = 0.6; 95% CI = 0.3–1.5).

Failure to meet professional standards of care

Selected studies found an association between ‘obstetric violence’ and skilled attendance at birth. Dey et al. (Reference Dey, Shakya, Chandurkar, Kumar, Das and Anthony2017) found that not having a skilled birth attendant (trained provider) was associated with an increased risk of mistreatment, as measured by self-report (AOR = 1.47; 95% CI = 1.05–2.04), as well as measured by observation (AOR = 1.44; 95% CI = 1.02–2.02). In contrast, another study from Uttar Pradesh found that women having unskilled health providers (Accredited Social Health Activist [ASHA]/dais) were more than twice as likely to experience mistreatment (OR = 2.56; 95% CI = 0.89–7.36) than when the provider was a doctor (Bhattacharya & Sundari Ravindran, Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018).

Dey et al. (Reference Dey, Shakya, Chandurkar, Kumar, Das and Anthony2017), in their assessment of the lack of informed consent in public health facilities in Uttar Pradesh, found that 47.8% of women reported not being provided with complete information on delivery procedures, and 27.0% reported that their consent was not taken before conducting delivery procedures. A study assessing disrespect and abuse in facility-based (public and private) childbirth in villages of Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, found that non-consented services (71.1%) and non-confidential care (62.3%) were the most common types of mistreatment (Nawab et al., Reference Nawab, Erum, Amir, Khalique, Ansari and Chauhan2019). Sharma et al. (Reference Sharma, Penn-Kekana, Halder and Filippi2019) found that nearly 30% of women in public and private maternity facilities of Uttar Pradesh were not asked for their consent for a vaginal examination.

Poor and indigenous women, who disproportionately use state health facilities, reported both tangible and symbolic violence, including improper pelvic examination and iatrogenic procedures such as episiotomies, which in some instances are done without anaesthesia (Chattopadhyay et al., Reference Chattopadhyay, Mishra and Jacob2017). A mixed-methods study conducted in public- and private-sector birth facilities found that an episiotomy was performed in 24% of cases and that the prevalence was similar in the two sectors (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Penn-Kekana, Halder and Filippi2019). However, when an episiotomy took place, no analgesia was given in 25% of cases, and this rate was similar in the two sectors. Comments recorded by observers corroborated that analgesics were often not given during episiotomies, despite women crying and shouting in pain.

Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran (Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018) found that women reported being subjected to surgical procedures without being offered pain relief, and 12.0% said they had been subjected to excessive force during examination or delivery. Women feared unnecessary procedures in institutions, such as Caesarean section deliveries (Barnes, Reference Barnes2007). Another study found that the prevalence of manual exploration of the uterus after delivery was 80% in public and private facilities combined (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Penn-Kekana, Halder and Filippi2019). The same study found that nearly 30% of women were subjected to fundal pressure in public facilities.

There were reports of women being subjected to medical negligence and carelessness. Chattopadhyay et al. (Reference Chattopadhyay, Mishra and Jacob2017) reported a participant whose doctor left cotton inside her vagina and forgot to tell her. For over 2 weeks post-delivery, she was harbouring two pieces of gauze, which could have been fatal had it not been for her own alertness. Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran (Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018) reported that almost 8.5% of respondents in their study were ignored when they asked for help, and two delivered without any assistance from a health care provider, suggesting neglect and abandonment. Dey et al. (Reference Dey, Shakya, Chandurkar, Kumar, Das and Anthony2017) found that 5.1% of women faced problems due to the unavailability of a provider during delivery; Sudhinaraset et al. (Reference Sudhinaraset, Treleaven, Melo, Singh and Diamond-Smith2016) found that 10.5% of the study women delivered alone; and Patel et al. (Reference Patel, Makadia and Kedia2015) recorded 25.1% of women reported ‘abandonment of care’.

A district-level study in Assam exploring the opinions of health care providers on ‘obstetric violence’ noted that a 50-year-old physician/public health practitioner reported that he was taught to ‘cut the patient [woman in labour] at the peak of her pain’ (Chattopadhyay et al., Reference Chattopadhyay, Mishra and Jacob2017, p. 7). This practice came from teachers who were mostly men and was given the explanation ‘because they are already in pain, no anaesthetic is required because they [women] won’t feel much’ (Chattopadhyay et al., Reference Chattopadhyay, Mishra and Jacob2017).

Poor rapport between women and providers

Diamond-Smith et al. (Reference Diamond-Smith, Sudhinaraset, Melo and Murthy2016), in their study of women aged 16–30 years living in slum areas of Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, and delivering in a health facility showed that lack of support in the form of discussions with providers and provision of information by health care providers was strongly associated with a higher reported mistreatment score. Barnes (Reference Barnes2007) noted that women reported that providers were not sensitive to their needs, and that ‘city doctors will not wait a whole day for the delivery to take place. They will cut open the stomach and bring out the baby’. Finally, Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran (Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018) observed that mothers were only attended to when they were going to deliver; otherwise, they were allowed to suffer. One study observed that women who experienced complications during delivery were abused more (AOR = 4.18; 95% CI = 1.78–9.83) (Bhattacharya & Sundari Ravindran, Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018). This was reiterated by another facility-based study by Dey et al. (Reference Dey, Shakya, Chandurkar, Kumar, Das and Anthony2017), which found that births that resulted in post-partum maternal health complications were twice as likely to be associated with self-reported mistreatment (AOR = 2.0; 95% CI = 1.34–3.06). Similarly, Raj et al. (Reference Raj, Dey, Boyce, Seth, Bora and Chandurkar2017) found that women who reported mistreatment by a provider during childbirth had higher odds of complications at delivery (AOR = 1.32; 95% CI 1.05–1.67) and post-partum (AOR = 2.12; 95% CI 1.67–2.68).

Studies also showed reported incidences of women being left alone and their family not being allowed in the room (Van Hollen, Reference Van Hollen2003; Barnes, Reference Barnes2007; Hulton et al., Reference Hulton, Matthews and Stones2007). Sudhinaraset (Reference Sudhinaraset, Treleaven, Melo, Singh and Diamond-Smith2016) found that 19.6% of participants reported not being allowed a birth companion. Even in private facilities with ample infrastructure, the reason cited for refusal of a birth companion was that it would interfere with the hospital’s standard of sterilization in the labour room. A study that looked at the mistreatment of women in public and private facilities in Uttar Pradesh found that the private sector performed worse than the public sector in not allowing birth companions to accompany woman in labour (p = 0.02) (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Penn-Kekana, Halder and Filippi2019).

Nawab et al. (Reference Nawab, Erum, Amir, Khalique, Ansari and Chauhan2019), in a community-based study of birth facilities in Uttar Pradesh, found that 3.3% of women reported being detained in facilities for failure to pay. In another study, approximately 8% of women reported restrictions on food and water intake during labour and childbirth (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Penn-Kekana, Halder and Filippi2019). Sudhinaraset et al. (Reference Sudhinaraset, Treleaven, Melo, Singh and Diamond-Smith2016) found that 10.5% of women reported they were denied their choice of birth position and that auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs) and government doctors were less likely to accommodate traditional rituals and practices than were rural medical practitioners (RMPs) (Barnes, Reference Barnes2007). An RMP in India is a village doctor who practises modern (allopathic) medicine without any formal registration/approval or legal sanction (Kanjilal, Reference Kanjilal2011). As compared to the finding from Sudhinaraset et al. (Reference Sudhinaraset, Treleaven, Melo, Singh and Diamond-Smith2016), another study noted a much higher percentage of denial of birthing position choice in both public- and private-sector facilities, wherein 92% of women were not offered a choice (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Penn-Kekana, Halder and Filippi2019).

Health system conditions and constraints on women in childbirth

The physical conditions of facilities were often the reason that women perceived care facilities to be poor in quality (Barnes, Reference Barnes2007). At the facility level, delivery environments can be chaotic and unsafe in India (Chaturvedi et al., Reference Chaturvedi, De Costa and Raven2015). Poor ‘readiness’ to provide good-quality delivery care was observed in several areas: deficiencies in staffing, infrastructure, equipment and supplies and cleanliness. Sharma et al. (Reference Sharma, Penn-Kekana, Halder and Filippi2019) reported frequent reports of stray animals such as dogs and cows roaming throughout facility compounds and often taking shelter in wards and labour rooms. Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran (Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018) reported that 4.9% of women considered unhygienic conditions and a lack of basic amenities to be a type of abuse. One patient said, ‘It was like a dump. I could see blood and stuff of other women on the bed sheets. There were plastic bags, used sanitary napkins, urine, blood, vomit, food; everything on the floor, the toilets were overflowing with faeces with no water facility inside; finally, I had to go to the fields’. This illustrates the lack of trained and accessible health providers and appropriate facilities in the study area (Barnes, Reference Barnes2007).

Another study (Bhattacharya & Sundari Ravindran, Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018) highlighted women’s loss of autonomy: 5.6% of the women underwent vaginal examinations or deliveries in the presence of strangers without any curtains or physical privacy. They also found that 90.5% of patients reported inappropriate demands for money made by health care providers. Barnes (Reference Barnes2007) reported cases of mothers not being provided with beds. They also reported a case of a nurse asking a woman for money, soap and clothes after the birth of her baby. When she didn’t comply, the nurse did not allow her to hold her baby.

Harmful traditional practices and beliefs

Some women and providers in Jharkhand held on to beliefs such as ‘fasting is needed to “dry” the mother’s body so that she stops bleeding’ – a problem perceived as being more harmful than a lack of breast milk (Barnes, Reference Barnes2007). Hence, the nutrition required by a young mother’s body to make breast milk would rather be compromised, than seeing the need to take measures to control post-partum haemorrhage. Other examples of harmful beliefs/practices included the perception of heavy post-partum bleeding as being normal, the custom of post-partum fasting and the practice of conducting internal examinations and removing the placenta with unwashed bare hands or with non-sterile gloves. The risks associated with these practices and beliefs were rarely acknowledged by study participants. The same study found that traditional practices were compounded by harmful modern practices by the RMPs. They rarely examined the abdomen, assessed fetal heartbeat or position, or diagnosed obstructed labour. Among the most common dangerous practices employed by RMPs were the administration of oxytocin injections and conducting unnecessary episiotomies. A pertinent finding was that the practice of health care facilities throwing away the placenta was considered inauspicious to women, and was described as a factor underlying their reluctance to seek institutional delivery.

Overview

‘Obstetric violence’ has been described as having taken place when routine medical or pharmacological procedures associated with labour are conducted without allowing the woman to make decisions regarding her own body (D’Gregorio, Reference D’Gregorio2010). Such treatment is antithetical to the Universal Rights of Childbearing Women charter, which states that every woman has the right to dignified, respectful sexual and reproductive health care, including during childbirth (White Ribbon Alliance, 2011).

This integrative review of the existing literature found that, although the selected studies reported a high prevalence of ‘obstetric violence’ in health care facilities in India, the nature of the violence was highly variable. A study among labouring women in public and private facilities in Uttar Pradesh found that all women in the study reported at least one indicator of mistreatment (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Penn-Kekana, Halder and Filippi2019). A community-based study in Uttar Pradesh found that 84.3% of women reported some kind of disrespect and abuse (Nawab et al., Reference Nawab, Erum, Amir, Khalique, Ansari and Chauhan2019). While the prevalence of women reporting any form of ‘obstetric violence’ was about the same in the studies of Patel et al. (Reference Patel, Makadia and Kedia2015) (57.7%), Sudhinaraset et al. (Reference Sudhinaraset, Treleaven, Melo, Singh and Diamond-Smith2016) (57.0%) and Diamond-Smith et al. (Reference Diamond-Smith, Treleaven, Murthy and Sudhinaraset2017) (50.0%), other studies in Uttar Pradesh found a much lower prevalence of women reporting any kind of obstetric violence – namely, 28.8% (Bhattacharya & Sundari Ravindran, Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018) and 15.1% (Goli et al., Reference Goli, Ganguly, Chakravorty, Siddiqui, Ram, Rammohan and Acharya2019). The latter were closer to the findings from a facility-based survey by Dey et al. (Reference Dey, Shakya, Chandurkar, Kumar, Das and Anthony2017), where observational data by health care providers showed that 22.4% of women reported being mistreated during delivery. The same study, however, found a much lower prevalence of self-reported mistreatment of women by health care providers, at 9.1%. Similar variability has been observed in other low- and middle-income countries, wherein the prevalence of self-reported disrespect and abuse ranges from 20% in Kenya (Abuya et al., Reference Abuya, Warren, Miller, Njuki, Ndwiga and Maranga2015) to 43% in Ethiopia (Wassihun & Zeleke, Reference Wassihun and Zeleke2018) to 98% in Nigeria (Okafor et al., Reference Okafor, Ugwu and Obi2015).

A possible explanation for these contrasting results could be the use of different definitions for each kind of abuse (Bhattacharya & Sundari Ravindran, Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018). There is a lack of global standard measures of abuse, which may partially account for the highly varied reported prevalences of mistreatment (12–98%) across different populations and national contexts (Freedman & Kruk, Reference Freedman and Kruk2014; Freedman et al., Reference Freedman, Ramsey, Abuya, Bellows, Ndwiga and Warren2014). Moreover, the sampling of participants may affect the reported prevalence of ‘obstetric violence’; for instance, the higher prevalence of any form of disrespect and abuse found by Nawab et al. (Reference Nawab, Erum, Amir, Khalique, Ansari and Chauhan2019) may be due to the fact that only 4- to 6-week post-partum females were included, which greatly reduced the reporting bias (inability to recall).

None of the studies included in this review recorded any incidence of sexual abuse. However, it is possible that, due to perceived stigma and discrimination, sexual abuse might not have been reported by women. This is in line with the findings of Bohren et al. (Reference Bohren, Vogel, Hunter, Lutsiv, Makh and Souza2015), who found evidence of sexual abuse only from their quantitative synthesis and not their qualitative one. Hence, it is possible that women are uncomfortable reporting sexual abuse, and further quantitative inquiry is needed for sensitive data on this topic to emerge. This does not in any way undermine the strength of qualitative inquiry in obtaining information of such a sensitive nature.

Another important finding from this review was a significant association between mistreatment and maternal complications (Dey et al., Reference Dey, Shakya, Chandurkar, Kumar, Das and Anthony2017; Raj et al., Reference Raj, Dey, Boyce, Seth, Bora and Chandurkar2017; Bhattacharya & Sundari Ravindran, Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018). Moreover, the reviewed studies found an association between type of provider and the experience of ‘obstetric violence’ (Dey et al., Reference Dey, Shakya, Chandurkar, Kumar, Das and Anthony2017; Bhattacharya & Sundari Ravindran, Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018). This is important because women reporting the use of an unskilled provider rather than a staff nurse for delivery were more likely (AOR = 8.32; 95% CI = 2.50–27.60; p < 0.01) to report delivery complications (Raj et al., Reference Raj, Dey, Boyce, Seth, Bora and Chandurkar2017). This relationship between ‘obstetric violence’ and complications is a critical finding because the reduction in maternal complications is a high-priority goal for programmatic efforts to improve maternity care, and any such finding should be considered carefully, whether causal or not (Dey et al., Reference Dey, Shakya, Chandurkar, Kumar, Das and Anthony2017). Moreover, maternal stress of any kind slows down the labour process, thereby increasing the chances of complications (Freedman et al., Reference Freedman, Ramsey, Abuya, Bellows, Ndwiga and Warren2014). Further ahead in the chronology, post-partum depression has also been found to be significantly associated with a negative childbirth experience (Gausia et al., Reference Gausia, Ryder, Ali, Fisher, Moran and Koblinsky2012).

One of the consequences of ‘obstetric violence’ that emerged from this review was that some women perceived institutional delivery as being threatening, particularly if they had prior experience of pregnancy-related hospitalization (Barnes, Reference Barnes2007). Nawab et al. (Reference Nawab, Erum, Amir, Khalique, Ansari and Chauhan2019) found that, when women were asked about their willingness to attend a facility for childbirth in the future, of those who said ‘no’, 93.8% reported experiencing some form of disrespect and abuse. Of those who were indecisive, 91.7% had experienced disrespect and abuse. This association between experiencing any disrespect and abuse and the decision to attend a facility in the future was statistically significant (χ2 = 11.188, df = 2, p < 0.05). Therefore, keeping in mind the government’s goal of increasing institutional delivery in order to reduce maternal mortality in India, the aforementioned findings underscore the need to prevent ‘obstetric violence’ and promote Respectful Maternity Care.

This review has highlighted evidence of a practice of suppressing women’s pain, or rather their expression of pain, during childbirth. Some women were asked to keep quiet when they shouted out in pain, or were abused, both physically and verbally. This finding was reinforced by a health care provider who said that many women screamed during labour, not out of ‘real pain’, but because the screams of a woman on another bed compelled women in the labour ward to join in communal screaming, ‘whether or not there’s real pain’ (Chattopadhyay et al., Reference Chattopadhyay, Mishra and Jacob2017). Such explanations are not uncommon in other parts of the world, as the disciplining of labouring women by suppressing their screams is one of the more insidious, yet common, forms of ‘violence’ inflicted through biomedical institutionalization (Shabot, Reference Shabot2016; Chadwick, Reference Chadwick2017).

A unique finding that emerged from this review of the Indian experience was the persistence of some harmful traditional practices and beliefs during childbirth in certain parts of rural India, which result in the misperception of risks to the mother and child. Studies have noted that a lack of acceptance of certain post-partum beliefs by institutional facilities results in women in rural India preferring home births (Van Hollen, Reference Van Hollen2003; Barnes, Reference Barnes2007). In addition, the adoption of dangerous ‘modern’ practices during home deliveries, in particular the use of oxytocin injections, was also noted. It was important to highlight these practices in this review, even though they do not adhere to the classification provided by Bohren et al. (Reference Bohren, Vogel, Hunter, Lutsiv, Makh and Souza2015), because India is a vastly diverse country with entrenched forms of ‘obstetric violence’ that are not necessarily limited to formal facilities. They are also extant in traditional birth practices and birth centres where trained village women health workers conduct deliveries. This is pertinent for India because, on the one hand, women are encouraged to give birth in institutions where they are often met with ‘obstetric violence’, while on the other hand, women from rural areas who are reluctant to access institutional care during childbirth due to fear of such ‘violence’ and being subjected to harmful practices that may jeopardise their health. These results pertain to the unique web of home births, institutional births and those carried out in quasi-institutional settings in India. Their inclusion is necessary and important because they are an impediment to the chances of many women of having a safe childbirth experience.

An element of ignorance among women about what constitutes a harmful practice was observed. The occurrence of ‘obstetric violence’ among women with no mass media exposure was found to be approximately five times higher (OR = 4.7; 95% CI = 1.7–12.8) than among those with mass media exposure in a study by Goli et al. (Reference Goli, Ganguly, Chakravorty, Siddiqui, Ram, Rammohan and Acharya2019). However, this review also found evidence of women normalizing acts of ‘obstetric violence’ that were evidently harmful, such as physical abuse and applying unnecessary force during delivery. Nawab et al. (Reference Nawab, Erum, Amir, Khalique, Ansari and Chauhan2019) found that 89.1% of women who experienced disrespect and abuse answered ‘no’ to the query about any treatment that they perceived as humiliating, and this association was statistically significant. This finding is consistent with previous reports of treating disrespectful maternal care as ‘normal’ and part of an age-old practice by health providers and by women undergoing such treatment (Bowser & Hill, Reference Bowser and Hill2010; Sando et al., Reference Sando, Ratcliffe, McDonald, Spiegelman, Lyatuu and Mwanyika-Sando2016). This normalization not only helps increase the prevalence of the problem but also renders it part of the ‘iceberg phenomenon’ by way of non-recognition and under-reporting (Nawab et al., Reference Nawab, Erum, Amir, Khalique, Ansari and Chauhan2019).

Madhiwalla et al. (Reference Madhiwalla, Ghoshal, Mavani and Roy2018) noted that their study participants acknowledged that the mistreatment of women in the form of shouting and physical coercion existed, although this was not necessarily perceived as abuse. Furthermore, Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran (Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018) found that, although statistically insignificant (p = 0.31), there was a high prevalence (25.0%) of reported abuse in private health facilities. Other studies recorded evidence of significant ‘obstetric violence’ in private facilities (Nawab et al., Reference Nawab, Erum, Amir, Khalique, Ansari and Chauhan2019; Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Penn-Kekana, Halder and Filippi2019). This shows that abusive provider behaviour has become a norm and is not restricted to government facilities where the providers are over-worked and have to work with limited resources (Bhattacharya & Sundari Ravindran, Reference Bhattacharya and Sundari Ravindran2018). For example, nurses working in New Delhi maternity homes attributed impolite and disrespectful treatment of impoverished women to long working hours, poor pay and overcrowding of facilities (Singh, Reference Singh2010). Thus there appears to be evidence of a normalization of obstetric violence in private hospitals in India. Further research is needed to assess this.

Providers set expectations and norms around what is acceptable behaviour during delivery, while women are often misinformed and may have low expectations of care. This was corroborated by a facility-based study that showed under-reporting of disrespectful and abusive behaviour by women who delivered at public health facilities (Dey et al., Reference Dey, Shakya, Chandurkar, Kumar, Das and Anthony2017). While 9.1% of women self-reported mistreatment during delivery, the directly observed mistreatment rate was much higher, at 22.4%. A study of women who recently gave birth at public health facilities in Uttar Pradesh indicated that one in five experienced mistreatment by their provider during delivery. This did not differ for women whose deliveries were observed or conducted by a mentored nurse (Raj et al., Reference Raj, Dey, Boyce, Seth, Bora and Chandurkar2017). Another study from Uttar Pradesh found a significant difference in mistreatment with the timing of admission, such that a greater proportion of mistreatment was observed in cases admitted during working hours compared with those observed outside regular working hours (p = 0.02) (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Penn-Kekana, Halder and Filippi2019).

The review’s findings suggest that mistreatment practices may not only be common, but are sufficiently acceptable that observation does not deter them. Hence, culture plays an important role, and its effect is further highlighted by a study in Uttar Pradesh, which found that lack of ‘cultural health capital’ disadvantages women during delivery care in India (Sudhinaraset et al., Reference Sudhinaraset, Treleaven, Melo, Singh and Diamond-Smith2016). Thus, when poorer women, and those of lower social standing, are subjected to ‘obstetric violence’, they are unable to recognize and describe the low quality of care or discrimination. Diamond-Smith et al. (Reference Diamond-Smith, Treleaven, Murthy and Sudhinaraset2017) assessed the association between women’s empowerment and mistreatment during childbirth and found that dimensions of empowerment related to social norms about women’s values and roles were associated with their experiences of mistreatment during childbirth.

The review found an association between socio-demographic factors and ‘obstetric violence’. Among the various determinants of disrespect and abuse, socioeconomic status was found to be significant (Diamond-Smith et al., Reference Diamond-Smith, Treleaven, Murthy and Sudhinaraset2017; Goli et al., Reference Goli, Ganguly, Chakravorty, Siddiqui, Ram, Rammohan and Acharya2019; Nawab et al., Reference Nawab, Erum, Amir, Khalique, Ansari and Chauhan2019). Other significant factors were caste (Dey et al., Reference Dey, Shakya, Chandurkar, Kumar, Das and Anthony2017; Diamond-Smith et al., Reference Diamond-Smith, Treleaven, Murthy and Sudhinaraset2017; Goli et al., Reference Goli, Ganguly, Chakravorty, Siddiqui, Ram, Rammohan and Acharya2019) and religion (Goli et al., Reference Goli, Ganguly, Chakravorty, Siddiqui, Ram, Rammohan and Acharya2019). In previous literature from other countries, socio-demographic factors such as higher parity, lower SES and HIV-positive status have been reported to predispose women to disrespect and abuse during childbirth in a facility (Bowser & Hill, Reference Bowser and Hill2010; Diniz et al., Reference Diniz, Salgado, Andrezzo, de Carvalho, Carvalho, Aguiar and Niy2015).

Study limitations

This review has certain limitations. First, the research was limited to seven states in India, hindering generalization about the results of these studies to other parts of the country. Second, the sample sizes of the included studies failed to give a sense of the actual magnitude of ‘obstetric violence’ in India. Third, only one study (Chattopadhyay et al., Reference Chattopadhyay, Mishra and Jacob2017) in the review looked at intentionality as defined by Freedman and colleagues, i.e. that the definition of disrespect and abuse should include actions that the provider intends to be harmful, but that such intent should not be a requirement of disrespect and abuse (i.e. unintended should also be included) (Freedman & Kruk, Reference Freedman and Kruk2014).

Conclusions and policy recommendations

There are clear systemic issues that allow ‘obstetric violence’ to occur: an insensitive medical education curriculum, constraints on provider time and resources, disempowerment of nurses and community health workers and a lack of accountability (Chattopadhyay et al., Reference Chattopadhyay, Mishra and Jacob2017). The political will to address the problem will need to be built among professionals as well as governments, and resources will need to be allocated (Jewkes & Penn-Kekana, Reference Jewkes and Penn-Kekana2015). The World Health Organization has been a pioneer in this, making recommendations for intrapartum care resulting in a positive childbirth experience (WHO, 2018). The focus of the global agenda has gradually expanded beyond just the survival of women and their babies, to ensuring they both thrive and achieve their full potential in terms of health and well-being.

In response to global efforts to tackle the poor treatment of women during childbirth (White Ribbon Alliance, 2011; WHO, 2015, 2018), recent efforts in India to improve quality of care during childbirth have focused on provider training and checklists to increase implementation of key clinical practices (e.g. washing hands with soap and checking vital signs) (Chaturvedi et al., Reference Chaturvedi, De Costa and Raven2015; Arora et al., Reference Arora, Shields, Grobman, D’Alton, Lappen and Mercer2016). In terms of executive measures, the National Health Policy 2017 set objectives to deal with gender-based violence and address the quality of care provided under reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health (RMNCH+A) programmes (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2017). Such measures have been supplemented by the recent Labour Room Quality Improvement Initiative (LaQshya) guidelines released by the Indian government (National Health Mission, 2017). These state that the delivery of transformed care not only needs the availability of adequate infrastructure, functional and calibrated equipment, drugs, supplies and human resources, but the meticulous adherence to clinical protocols by service providers at health facilities. A component of care that is almost universally absent due to infrastructural constraints in public facilities in India is the presence of a birth companion. While Tamil Nadu has identified the importance of this, and started a Birth Companionship Programme to improve maternal health (Department of Health and Family Welfare, 2005), other states are yet to follow suit. Evidence shows that women who receive any type of support from their husband or a health worker are significantly more likely to report lower mistreatment scores (Diamond-Smith et al., Reference Diamond-Smith, Sudhinaraset, Melo and Murthy2016).

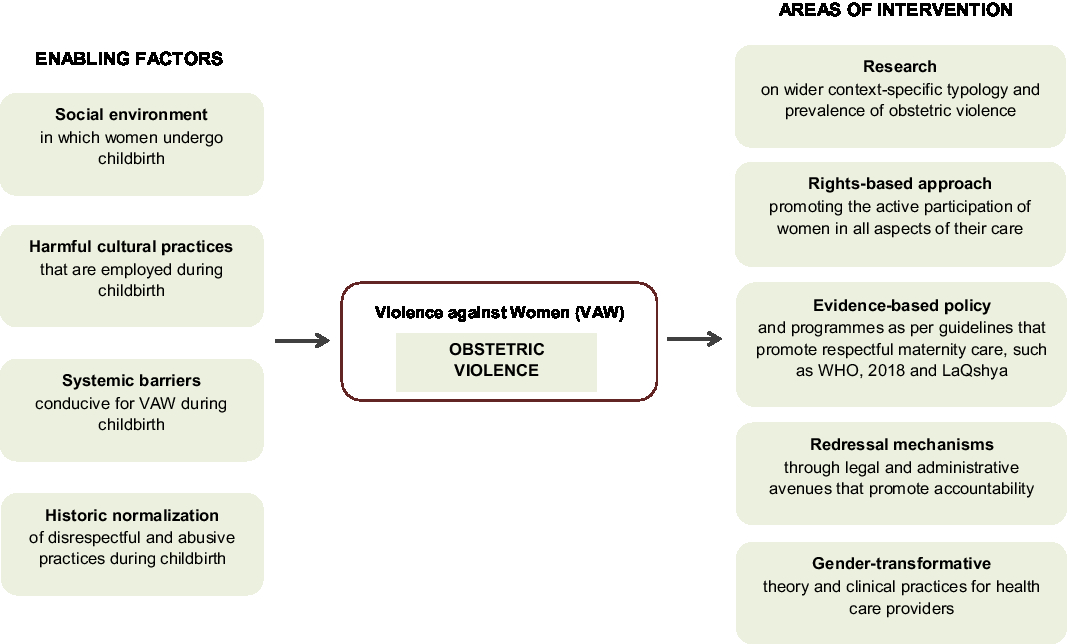

In conclusion, this review provides a picture of the normalized nature of ‘obstetric violence’ in India. The included studies highlight the key socio-cultural, economic and systemic obstacles that deny women access to quality care during childbirth. Patriarchal societies and organizational hierarchy allow undemocratic power relations to develop between patients and providers. Combined with a historic normalization of gender-based violence, women in general, and those of lower social standing in particular, harbour lower levels of expectation of quality care during childbirth. Figure 2 illustrates a way forward for addressing ‘obstetric violence’ in India as a subset of violence against women. The factors that enable ‘obstetric violence’ are listed as social environment, harmful cultural practices, systemic barriers and historic normalization of violence against women. Hence, the areas of intervention to address ‘obstetric violence’ are based on the manifestations of these factors. Suggestions for future research include a wider geographical coverage that identifies a typology and prevalence of ‘obstetric violence’. A rights-based approach builds on the fact that results will be seen when the objective of Respectful Maternity Care is adopted as an extension of the elimination of ‘obstetric violence’, which includes respect for women’s autonomy, dignity, feelings, privacy, choices, freedom from ill treatment and coercion and consideration for personal preferences, including the option of companionship during maternity care (National Health Mission, 2017). Evidence-based policy and programmes are critical for achieving the reduction in maternal mortality that is envisioned in the SDGs. Redressal mechanisms should be enabled to generate support for women and accountability for health care providers. As a long-term goal, gender-transformative education and clinical practices should be developed and taught to future health care providers. Such education and practice promotes gender equality and equity in health with the aim of redressing health inequities that are a consequence of gender roles and unequal gender-relations in society (World Health Organization, 2007). Ultimately, the improvement in maternal mortality ratio requires a transformational change in the processes related to care during delivery, which essentially amounts to quality care without violence or coercion and the participation of women in decision-making while retaining agency over their own bodies.

Figure 2. Multi-pronged framework for addressing ‘obstetric violence’ in India.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the help given by the Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes (CEHAT) and the organization’s field-level practitioners working on obstetric violence. The interaction with them was instrumental in gaining understanding about the issue of obstetric violence and placing it in the larger context of violence against women. The authors are indebted to the anonymous reviewers and the editor for their critical feedback, which sharpened the paper greatly.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial entity or not-for-profit organisation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.