1. Introduction.

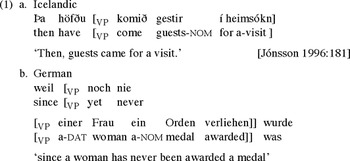

In languages like Icelandic and German, nominative DPs appear to be acceptable in vP/VP internal positions, as for example in 1.1

Since German main clauses require verb second configurations (which sometimes make it impossible to see where arguments in the middle field are), I follow standard practice and give most German examples as embedded clauses.

I use the following labels for clausal projections in German: CP for the complementizer domain, TP for the inflectional domain, and vP for active transitive und unergative constructions. Since there is no reason for assuming that nominative Case and agreement are separate in German (that is, subject-verb agreement is always with the nominative), I simply use TP and ignore Agr phrases. Note that this is just a labeling choice to make the structures more transparent and does not affect the analysis (it also does not mean that I reject split IP structures for German). Lastly, I represent unaccusative and passive predicates as VPs without a vP layer.

For theories in which nominative Case is licensed by T0 (see Chomsky 1981), this poses the question of how the appropriate licensing relationship is established. In the early 1990s, Chomsky developed a reductionist view of Case licensing, in which all such relations involved movement of the nominative to SpecTP. Thus, examples such as those in 1 would be analyzed as involving covert movement to SpecTP.

Alternatively, it could be assumed—at least for German—that the bracketing in 1b is not correct, and that the nominative is in fact in SpecTP, with everything to the left being adjoined to TP. A third view, assumes a covert expletive (pro) in SpecTP that checks nominative Case and agreement, and transfers these features to the nominative argument in situ via some form of coindexation (see Safir 1985a, 1985b, Sternefeld 1985, Koster 1987, Grewendorf 1988, 1990, Cardinaletti 1990, Jónsson 1996, and Haeberli 2002, among many others).

In this paper, I reconsider these issues and provide arguments against all three of these approaches. In particular, I show that (i) the constituent including the nominative arguments in 1b cannot be TP, (ii) covert movement of the nominative DP is excluded in certain cases, and (iii) the postulation of an empty expletive is neither necessary nor motivated. Instead, I propose an updated version of den Besten's (1985a) government approach (see also Fanselow 1991a, 1991b). I argue, following Chomsky 2000, that Case licensing is established under the government-like Agree configuration, with movement not driven by matters of Case and agreement. I conclude that Case/agreement are licensed vP/VP-internally and not in a specifier-head configuration.

Although this conclusion has also been reached in a series of works by Hubert Haider (see, for instance, Haider 1993, 2006), the theoretical implementations of the two approaches are very different. Haider, recognizing the problems of a specifier-head approach noted above, argues that German lacks Infl-type functional projections altogether and that Case/agreement cannot be seen as relations between a DP and a functional head, but rather as relations determined by the lexical argument structure. Thus, German and English differ substantially in their clausal architecture, and the way tense is represented and Case/agreement are licensed. I argue that these differences are not warranted and that the Agree approach together with a parameterization of the EPP offers a simpler and more explanatory account of the differences among languages.

The paper is organized as follows. In the first part (section 2), I establish that there are vP/VP-internal nominatives that never get to SpecTP. Hence, if the choices are Agree versus movement, the conclusion is that Agree is not only a possible way of analyzing these constructions, but is required.3

Chomsky (2000) suggests that English there-insertion contexts provide an argument for Agre. However, since there is an alternative specifier-head analysis (see Bobaljik 2002), there-insertion contexts only show that an Agree analysis is possible but not necessary. In what follows, I show that certain constructions are only compatible with the Agree approach and cannot be accounted for assuming a movement analysis.

2. Agree without Movement.

In this section, I present an argument for Agree—that is, for the claim that Case/agreement licensing is established without obligatory movement of the DP to the (specifier of) the relevant functional head. The argument for Agree (and against Move(ment) in these constructions) is based on topicalization constructions in German and leads to the conclusion that the EPP (as a requirement that Spec TP be obligatorily filled) does not hold in German. Before proceeding, it may be useful to lay out the issues to be discussed in their theoretical context. Thus, I first briefly summarize the major trends in the approaches to Case/agreement licensing.

2.1. A Short History of Case Licensing.

In standard GB-theory (Chomsky 1981), we find an asymmetry between nominative and accusative Case assignment: nominative is assigned under m-command (in a specifier-head configuration), whereas accusative is assigned in a sisterhood relation under c-command, as shown in 2.

With the development of a VP-external functional domain responsible for object Case (and agreement), it became possible to eliminate this asymmetry and to postulate a uniform Case/agreement mechanism (see Johnson 1991's μ-head, or proposals involving AgrO or v). According to Chomsky 1989, 1991, Mahajan 1989, and Déprez 1989, among many others, all Case/agreement licensing required a specifier-head configuration—thus, Case/agreement became parasitic on movement, as in 3.

To account for the VP-internal surface position of objects in English, as in 4, it is typically assumed that movement can be overt or covert—in English, subjects move overtly, whereas objects move covertly.4

Throughout this paper, I follow the traditional view about LF and represent covert phenomena (that is, operations where an element is pronounced in its base or lower position, but interpreted in the moved or higher position) as involving covert movement (that is, syntactic movement affecting interpretation but not pronunciation). If one adopts a more recent single output or cyclic spell-out model, many of the questions (and potentially also conclusions) will be different (see in particular note 15).

This universal view, however, is challenged by examples such as those in 1. To account for such examples, I follow Chomsky 2000, who revives the idea of a government-like relation for Case/agreement licensing. In particular, Chomsky suggests that all licensing is met via Agree. The Agree configuration for nominative and accusative licensing is shown in 5a. At its core, this relation is very similar to the configurations picked out by head-government in the GB framework, although the proposed locality conditions are different. In this relation, features are matched or licensed abstractly without movement. As characterized by Chomsky (2000), the Agree relation is initiated by a functional head with unchecked features (the probe), which seeks a potential checker (the goal) within some locality domain (the phase).

On the Agree approach, a DP that remains in situ on the surface may in fact remain there throughout the derivation. The approach is thus distinguished from the approach taken in the Economy period (see, for instance, Chomsky 1989, 1991). Under this approach, all checking relations were established by movement and a DP that remained in situ on the surface was taken to undergo covert movement. Note that under the Agree approach, movement is not excluded; it is simply not required to check Case and agreement features. For instance, movement of the subject in English can occur, as shown in 5b; however, the crucial claim of the Agree approach is that it is not triggered by the need to check Case and agreement features, but rather by a feature such as the EPP—that is, the requirement that a certain position (SpecTP) be filled. Returning to the cases in 1, since—as I show below—the nominative arguments are inside the VP at PF and LF, these examples provide an argument for the necessity of Agree. Furthermore, excluding an analysis involving empty expletives, I conclude that the EPP is not active in German and Icelandic; that is, there is no requirement that something moves to SpecTP or that this position be filled in these languages.

2.2. The Argument in Brief.

Let us assume for now as a null hypothesis, that Case and agreement are licensed uniformly across languages, in particular, that a nominative DP has to be in a certain structural relation with T (the null expletive and the TP-less views are discussed in sections 3 and 4). The major difference between the Agree approach and the specifier-head approach (henceforth Move approach) is whether movement is required to license Case/agreement.5

I do not distinguish between Agree and feature movement in this work. What I call Move involves movement, possibly covert, of a collection of features, such as those involved in scope and binding relations along with those involved in Case and agreement. By Agree I mean the possibility of checking the latter without affecting the position of the former. In this sense, Agree, Government, and Move-F converge, and are kept distinct from (phrasal) movement.

Consider, for example, a context in which an argument, such as a nominative DP agreeing with the finite verb, can be shown to be in a position lower than its Case/agreement position (SpecTP) at PF and LF. The PF position should be detectable by normal word order diagnostics, and the LF position could be fixed as low in contexts where we can independently exclude covert movement. Since in such contexts, a specifier-head relation between the subject and T cannot be established (either overtly or covertly), checking of the Case and agreement features would be impossible under the Move approach. Under the Agree approach, by contrast, such a scenario would be predicted to be grammatical as long as nothing else forces movement of the nominative DP.

I contend that this is exactly what we find in German VP-fronting contexts (see Haider 2006, Meurers 1999, 2000 for a similar argumentation but different theoretical conclusions). The shape of the argument is illustrated in 6; detailed examples and descriptions are provided in the next section. If in a context such as 6a the lower VP undergoes topicalization (that is, the nominative DP stays inside the VP in overt syntax), the nominative DP obligatorily takes scope under the stranded dative DP. These scope properties are not surprising since VP-fronting constructions are typically subject to scope freezing effects (see Barss 1986, Sauerland 1998, Sauerland and Elbourne 2002). Assuming that scope freezing is induced by a ban against reconstruction into or movement out of a (reconstructed) topicalized phrase, we can conclude that covert movement of the nominative DP is impossible, as shown in 6b.6

A reviewer correctly points out that the argument presented here relies on the premise that covert movement has an effect on scope. I believe that this premise is justified. For a theory to avoid circularity, there must be an independent diagnostic of covert movement. The assumption here is that scope serves as the best available independent effect of covert phrasal movement. It is conceivable that a theory may posit covert movement with no scope ramifications. Under this different set of assumptions, one would have to reconsider the conclusions reached here in light of whatever other independent diagnostic of covert movement might be justified. A theory in which Case/agreement relations were the only diagnostic of covert movement would—for the issue investigated here—be in principle unfalsifiable, and hence is not considered.

Importantly, however, we will see that nominative Case is obligatory and the nominative DP also obligatorily agrees with the finite verb in the contexts in 6. If Case/agreement checking required a spec-head configuration, these facts would be puzzling. Assuming, on the other hand, that feature checking is met via Agree, as in 6c, and that German lacks the EPP, the Case/agreement properties follow straightforwardly, since the nominative argument can stay in situ throughout the derivation while still Agreeing with the probe T.

Note that the important part of the argument to be presented is not the fact that nominative can be assigned to arguments in VP-internal position in German but that in certain constructions, nominative must be assigned to arguments inside the VP. Thus, while it seems uncontroversial that nominative DPs do not necessarily move overtly to SpecTP in German, an argument against nominative Case assignment/checking in a specifier-head relation can only be made if it can be shown that the nominative DP also does not move covertly to SpecTP. Scope freezing is thus the essential ingredient which yields the argument for the existence of Agree without movement.

2.3. Scope Freezing.

Let me start with an illustration of scope freezing contexts (see Barss 1986, Lechner 1996, 1998, Sauerland 1998, Sauerland and Elbourne 2002). The scope freezing contexts relevant for the discussion here are constructions in which a quantifier cannot scope out of a moved constituent containing it. While examples such as 7a are ambiguous between a wide and a narrow scope interpretation of the universal quantifier, the wide scope reading disappears when a constituent containing the universal quantifier is topicalized, as in 7b. I do not provide any explanation for this freezing effect; I simply assume that fronted XPs are “frozen” for scope in the sense that movement out of a frozen XP and reconstruction into a frozen XP are prohibited. However, reconstruction of the whole frozen XP is possible. Thus, in 7b, the topicalized XP can reconstruct, but then the universal quantifier cannot undergo further movement (resulting in a narrow scope interpretation with respect to the existential quantifier).7

For the argument provided here it is crucial that scope freezing is seen as a restriction on movement (see Bruening 2001 for an alternative account); furthermore, we assume that reconstruction is a syntactic phenomenon (see Lechner 1996, 1998 for an alternative view).

The same effect is found in topicalization constructions in German. I concentrate on unaccusative constructions involving an indirect dative object and a nominative argument. As will become clear as we proceed, it is not crucial that these constructions are unaccusative; all that is important is that the nominative starts out below the dative, which is typically only possible in unaccusative constructions. As is shown in 8, these constructions allow scope ambiguity between the two arguments, indicating that covert movement is in principle possible.8

The inverted scope interpretation is only available in German under a fall-rise intonation (see Frey 1989, 1993, Krifka 1998, Lechner 1998). This fact has led to a well-known controversy regarding scope in German. As argued in Frey 1989, 1993, sentences with this special intonation should not be used to determine the scopal options in German. However, sentences with a fall-rise intonation, which are ambiguous, are regular sentences of German and hence need to be derived as well. Note that it has also been pointed out for English (which is a prototypical non-rigid scope language) that sentences with an inverted scope reading require a special intonation (see, for instance, Jackendoff 1972, Ladd 1980, 1996). This effect is perhaps not as strong as it is in German, but it nevertheless seems to be a fact that inverted scope goes together with certain intonational properties. I thus do not see a reason to exclude examples such as 8 from the discussion of scope and to not postulate covert movement in these examples as a mechanism to derive the inverted scope order.

If, by contrast, the universal quantifier is part of a topicalized constituent as in 9, the ambiguity disappears and again only a narrow scope interpretation of the universal quantifier is possible.9

For some speakers, topicalization of a constituent including a strong nominative QP is marked. The judgments in this section are from speakers who allow this construction.

Before I turn to the structure of these examples and their relevance for the question of Agree versus Move, a few words about the underlying structure of 8–9 are necessary. I follow the general assumption that the nominative argument originates in a position lower than the dative argument (see Frey 1989, 1993, Haider and Rosengren 2003, among others). One piece of evidence for this claim comes from variable binding. Comparing the variable binding properties in unaccusative nominative/dative constructions with those in transitive nominative/dative constructions (for example, constructions with verbs like help) leads to the conclusion that the dative DP is generated in a position higher than the nominative DP in unaccusative constructions, whereas the nominative DP is the higher argument in transitive constructions. Relevant examples are given in 10. All examples involve a bound variable embedded in the first argument and a quantified DP as the second argument (in the linear order). In the first two examples, the nominative precedes the dative. As can be seen in 10a versus 10b, a bound variable interpretation is only possible in this configuration when the verb is unaccusative; the structure is ungrammatical when the verb is transitive. In contrast, if the dative precedes the nominative, as in 10c,d, a bound variable interpretation is possible in the transitive construction and prohibited in the unaccusative construction. (All examples are grammatical when the pronouns are interpreted referentially or when the arguments are switched).

A standard account of asymmetries of this sort is that in the orders that allow a bound variable interpretation, the arguments embedding the bound pronouns do not occur in their base positions but have been moved to their surface position from a position lower than the quantified arguments (see 11a,d).10

Note that German is a head-final language. Assuming a head-final structure, the arguments in 10b,c and 11b,c appear in their base positions.

Without going into further detail, the generalization allows us to draw certain conclusions about the basic order of arguments.11

For instance, I do not discuss the question of why covert quantifier movement is impossible in 11b,c. One possibility is to assume that covert movement is A′-movement which causes a Weak Cross-Over violation. However, the question is then why no such violation arises for overt scrambling as in i (which has been argued to be A′-movement by Webelhuth 1989, Müller and Sternefeld 1994), or for topicalization, as in ii.

Returning to the scope freezing examples in 9, the variable binding facts provide motivation for the structures in 12: the nominative DP, which is the lower argument, forms a constituent with the verb, and this constituent undergoes fronting. (Below I consider and reject an alternative according to which the nominative is in SpecTP.) Although it is not essential for the discussion, I assume here that the fronted constituent in the examples in 9 is a remnant VP, which includes the trace of the indirect objects. Alternatively, one could assume a VP-stacking analysis as suggested in Bobaljik 1995. In that case, the fronted constituent would simply be the lower of two recursive VPs and the fronted VP would not include the trace of the dative argument.

To account for the scope properties of 9, I assume again that the fronted VP can reconstruct at LF; however, further movement of the universal quantifier out of the boxed constituent in 12 (or reconstruction of the existential quantifier into that VP) is prohibited. The nominative quantifier can, however, undergo raising inside the frozen VP.12

Note that assuming the structure in 12, quantifier scope has to be computed between the actual quantifiers (that is, between two QPs after QR or reconstruction) and cannot be seen as a relation between a quantifier and the trace of another quantifier. Following a suggestion by W. Lechner, I assume that QR of the universal quantifier in 12a inside the frozen VP is possible, and presumably necessary for interpretational purposes. If QR targets a propositional node, the universal quantifier would end up in a position c-commanding the trace of the dative argument. However, this movement does not alter the scope relations.

In 12, we see that the underlying direct object, which obligatorily bears nominative case and agrees with the finite auxiliary is embedded in the VP at PF and LF (that is, it is in a projection which is lower than its Case/agreement position SpecTP). Thus, 12 constitutes a scenario for Agree: the nominative DP is not in SpecTP at PF, and, importantly, it cannot undergo further covert movement to SpecTP due to the fact that it is embedded in a frozen complement. Since in this scenario, Case/agreement features cannot be checked in a specifier-head relation but the structures are nevertheless well-formed, it can be concluded that feature checking via Agree (that is, without covert movement) must be possible.13

For the purpose of this paper, it does not matter whether Agree is established prior to VP-movement or after reconstruction. However, in Bobaljik and Wurmbrand 2005, we argue that Agree has to be met at LF. The topicalization facts discussed in this section then represent an instance of a mismatch between the operations Move and Agree: while movement is prohibited from frozen constituents, Agree can nevertheless “see into” a frozen XP. Thanks to Friedrich Neubarth for pointing this out.

Assuming that there are no covert pro's or expletives in these constructions (see section 3), the only way to maintain the claim that German has the EPP would be to follow Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou's (1998, 2001) analysis for VSO languages. That is, one could assume that there is an EPP feature on T in German which can be checked by the finite auxiliary in 12. However, since German does not show any of the VSO properties, this claim would appear to be rather stipulative. Thus, while this approach would technically allow us to maintain the universality of the EPP, it would still raise the question of why, for instance, English and German differ in the way the EPP can be checked (more specifically, why auxiliaries in T cannot check the EPP in English). Thus, a basic (non-derived) difference between languages remains—German, in contrast to English, does not display EPP-effects. Note also that, contrary to what Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou (1998, 2001) predict, it is possible in German for both the subject and the object to simultaneously remain VP-internal (see 14 and 15).

To complete the argument for Agree it is necessary to discuss one potential alternative structure, namely the structure in 13, which would allow feature checking in a specifier-head configuration. As illustrated in 13, one could imagine that the topicalized constituent is, in fact, the TP, and that the stranded material appears attached to TP. Crucially, if the structure in 13 were possible, Case could be licensed in a specifier-head configuration (that is, the nominative DP could have undergone overt movement to SpecTP). Furthermore, assuming as above that fronted constituents are frozen for scope, neither movement of the universal quantifier out of the fronted TP nor reconstruction of the existential dative argument into the TP would be possible. Hence, under the assumption that traces do not count for scope (that is, that c-commanding the trace of the dative quantifier is not sufficient for the nominative quantifier to take scope over the dative), the scope freezing effect could also be accounted for under the structure in 13.

Thus, if the examples in 9 can be represented by the structure in 13, they could not be taken as evidence for the necessity of Agree. However, there are independent reasons for excluding TP fronting as in 13. First, Abels (2003) develops a theory of (anti)locality, from which it follows that complements of phase heads are frozen in place and cannot undergo any kind of movement. More specifically, he argues that phase heads (C and v) require XPs in their c-command domain to go through their specifiers for the usual locality reasons. Thus, if a TP that is the complement of C were to move, it would need to move through the specifier of CP. However, Abels also argues for the following anti-locality principle: movement from the complement position to the specifier position of the same head is categorically excluded. Put together, these two assumptions entail that a TP (or TP segment) that is the complement of C, as in 13, will never be able to move. Thus, adopting Abels' framework, it follows straightforwardly that 13 is not a possible derivation.

The second reason for excluding a structure such as 13 comes from the presence of a trace in the fronted constituent. As can be seen in 13, fronting of the TP would necessarily involve a constituent headed by a trace (the trace of the finite verb/auxiliary in T). According to Haider 1990, 1993, 2006 and Fanselow 1993, this is impossible: fronting of a constituent containing the trace of the finite verb is illicit in German. Since the constraint against TP-fronting and the constraint against headless fronting make the same prediction for structures such as 13, I do not decide between these two approaches here (but see Wurmbrand 2004a for a detailed comparison). For the purpose of this paper, it is sufficient to note that 13 is an impossible derivation and that we can conclude that 12 is the only possible structure for 9. Thus, Agree is required to properly account for the scope and Case/agreement facts in these examples.15

As pointed out by a reviewer, this conclusion might not hold if one adopts a more recent single output or cyclic spellout model. Under this view, it could be assumed that the nominative DP in examples involving topicalization moves to SpecTP “overtly,” but is pronounced in the VP-internal lower position, giving rise to the effect that the nominative in examples such as 9 is inside the VP at “PF.” The challenge for this approach, however, is to explain why the nominative DP cannot be interpreted in the higher position (that is, why the interpretive component cannot choose the copy in SpecTP). It seems that this is not a trivial issue, since, in principle, the copy pronounced can be different from the copy interpreted in German (as illustrated, for instance, by examples without topicalization such as 8). In other words, one would need to find an account that explains in a principled way why a PF/LF mismatch is allowed in 8 but prohibited in 9 (note that while a principle such as Minimize Mismatch as developed in Bobaljik 2002 could explain the latter it cannot explain the former). Thus, at the current stage a copy theory account such as the one just sketched faces the problem that it must stipulate that the movement that satisfies feature checking in SpecTP has no PF or LF effect, and no other independent diagnostic (which makes this account unfalsifiable for all practical purposes). At the same time, I acknowledge that this type of account could be developed into an alternative to the Agree account presented here.

To conclude, I have argued for the existence of Agree as an abstract feature licensing mechanism. The argument is based on German topicalization constructions in which the subject (that is, a nominative argument agreeing with the finite verb) is in a position lower than its Case/agreement position (that is, SpecTP) at PF, and, importantly, is trapped in this position at LF. Since in these contexts, movement to the specifier position of the licensing head cannot occur (either overtly or covertly), the grammaticality of these constructions suggests that Case and agreement licensing does not require a specifier-head configuration, which is compatible with the Agree approach to feature licensing, but incompatible with the Move approach under which all feature checking takes place in specifier-head configurations. I therefore conclude that Agree in situ without Move is possible in German and that German lacks the EPP. The advantage of this approach is that it allows us to maintain a general mechanism for Case/agreement licensing.

2.4. Further Implications.

In the previous section, we have seen that in topicalization structures a nominative DP never occurs in SpecTP. Therefore, in such structures Case cannot be checked in a specifier-head configuration. I have argued that these facts support the claim that Case is licensed via Agree in these constructions, and that German lacks the EPP. In this section, I discuss some implications of these conclusions for Case licensing in German in general. I propose that Case is always licensed via Agree and that although movement to SpecTP is possible it is not triggered by the need to check Case or EPP features.

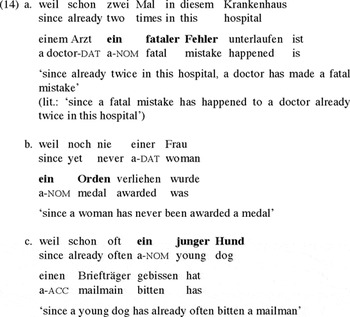

To begin with, consider the examples in 14 (14b is repeated from 1), where the nominative arguments do not appear next to the complementizers but further to the right after various adverbs, modifiers, and other arguments.

Assuming that Case is a structural relation between a DP and a functional head (see again sections 3 and 4 for different approaches), there are in principle three options to account for Case licensing in these examples: (i) overt specifier-head agreement (that is, the nominative DPs are in SpecTP and everything to the left is adjoined to TP); (ii) covert specifier-head agreement (that is, the nominative DPs are inside the vP/VP at PF and move to SpecTP at LF); and (iii) Agree (that is, the nominative DPs are inside the vP/VP throughout the derivation and Case/agreement is checked in situ). Although it is not possible to prove that options (i) and (ii) are not available, I believe that it is nevertheless possible to make an indirect argument for option (iii).

As shown in 15, the nominative arguments can be part of fronted constituents. Given the constraints on fronting discussed in the previous section, the nominatives in 15 cannot be in SpecTP at PF (otherwise the fronted constituent would have to be a TP, which is prohibited) and also not at LF (covert movement from fronted constituents is impossible). Thus, in this scenario, Case/agreement can again only be checked via Agree.

Since the examples in 14 are identical to the ones in 15, with the only difference that the latter involve topicalization of the vP/VP, the assumption that they involve different structures does not seem to be justified. To be more specific, if one were to maintain option (i) for 14, it would have to be assumed that the nominative DP (obligatorily?) moves to SpecTP unless topicalization applies (in which case, the nominative may stay within the vP/VP and receive Case via Agree). Thus, one would have to assume that the features triggering movement (whether those are Case or EPP features) are only present when no topicalization occurs. I think it is fair to say that this option is rather ad hoc, and, although it cannot be excluded empirically, a grammar that involves only one Case licensing mechanism (namely Agree) for both 14 and 15 clearly seems more economical.

As for option (ii), an account that postulates covert movement of the nominative DPs to SpecTP in examples such as 14 would predict the wrong interpretations—the indefinites in these examples strongly favor a non-specific interpretation. Let me illustrate this in more detail. As shown in 16, in German there is a strong tendency for indefinite arguments to be interpreted in their surface positions. If a specific interpretation is intended, movement is required (or highly preferred for most speakers); if a non-specific interpretation is intended movement is generally dispreferred.

Assuming that the two interpretations of indefinites correspond to different scopes relative to the adverb in 16, we can conclude that the subject is inside the VP at LF in 16b. Hence, covert movement does not occur and Case/agreement can again only be licensed via Agree. This can be further confirmed by the fact that fronting of a constituent including non-specific nominatives is possible (see 17; 17b is from Meurers 1999, 2000).

Thus, under the assumption that covert movement has an effect on interpretation (see also note 6), it is rather unlikely that the nominative DPs undergo covert movement in 14 and 16b. Thus, the most straightforward account for Case licensing in cases such as 14 is again an Agree account.

To conclude, I have suggested that Case is always licensed via Agree in German, and that DPs never move to check Case or EPP features. Crucially, however, this does not mean that DPs never move in German. As we have seen in 16a, for example, nominative DPs can occur in what looks like SpecTP. Since under the account presented here, movement is not Case/EPP-driven, there must be another reason for a DP to move. Since the position of (certain) DPs correlates with their interpretations, the answer is straightforward: Movement of DPs is not triggered by Case or EPP features, but rather by interpretation (as suggested, for instance, in Diesing 1992, Bobaljik and Thráinsson 1998). In the next section, we see that the same holds for Icelandic.

2.5. Icelandic.

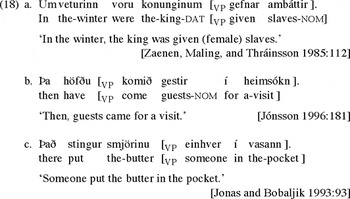

In this section, I illustrate that Icelandic, like German, allows VP-internal nominatives in the absence of any material in SpecTP. Note that I do not attempt to provide an exhaustive account of the distribution of Icelandic nominatives here. What is important for the purpose of this paper is to show that certain configurations require Agree. Examples illustrating that nominative arguments can occupy a low (that is, VP-internal) position at PF are given in 18 (18b is repeated from 1). The claim that these nominatives are VP-internal at PF is motivated by the fact that they follow the non-finite verbs in 18a,b, or a shifted object in 18c.16

Examples such as 18c (that is, VP-internal nominatives in transitive constructions) are rather restricted in Icelandic. Jonas and Bobaljik (1993) point out that only quantificational transitive subjects may remain inside the VP (at least for some speakers; see Thráinsson 1986); all other transitive subjects (including indefinites) must leave the VP. Furthermore, Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou (2001) show that transitive nominative arguments may remain inside the VP only if the object leaves the VP. While these are interesting differences between Icelandic and German that certainly require further attention, they do not challenge the basic claim made here that the VP-internal position is possible for nominative arguments in transitive constructions in Icelandic. To account for the restricted distribution of these nominatives, additional constraints such as the one suggested in Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou 2001 are necessary.

As for German, the questions posed by these cases are how Case/agreement are licensed and what (if anything) satisfies the EPP. Following recent works (see, for instance, SigurÐsson 1993, 1996, 2000, Boeckx 2000, Chomsky 2000, Hiraiwa 2001, Anagnostopoulou 2003, Holmberg and Hróarsdóttir 2003, Rezac 2004, Béjar and Rezac to appear), I suggest that Case/agreement licensing is met via Agree. This analysis is supported by the fact that the nominative arguments are not only inside the VP at PF, but also at LF. Following observations in den Dikken 1995 regarding English expletive constructions, Jónsson (1996:198ff) argues that the scope facts strongly suggest that no covert movement takes place in these constructions. This is illustrated in 19 (Jónsson, p.c., modified from Jónsson 1996); 19a only has a weak cardinal reading (that is, the quantified DP has to take scope under negation), and in 19b the nominative cannot bind the reciprocal (that is, it is not in a position c-commanding the PP at LF).17

Note that one could, of course, maintain the claim that there is covert A-movement in these cases, if one postulates obligatory reconstruction. It seems, however, that the sole motivation for this approach would be to save the assumption that something has to check the EPP (at LF) or Case/agreement in a specifier-head relation. In the lack of any true evidence, it would therefore seem that the burden would be on proponents of this approach to provide reasons for obligatory yo-yo movement before this option should be taken into account.

Regarding the second question, the EPP, the examples in 18–19 show that SpecTP is not filled by any overt material in these cases. Note in particular, that 18a,b, and 19 involve topicalization of adverbs which cannot have originated in SpecTP. I thus propose that Icelandic, like German, lacks the EPP—that is, there is no requirement that SpecTP be filled.18

This account would not be compatible with accounts of Stylistic Fronting (SF) in Icelandic, which assume that SF is triggered by an EPP feature in SpecTP (see, for instance, Holmberg 2000, 2006). Since SF alternates with an expletive in impersonal constructions, Holmberg (2000) argues that SF involves the EPP. However, the EPP account does not carry over straightforwardly to subject extraction contexts where SF is possible but not obligatory and no expletive is necessary in the absence of SF. To preserve an EPP account for these cases, a variety of additional assumptions is necessary (see Holmberg 2000, 2006). Note also that there is a controversy regarding whether SF is head movement or phrasal movement (see, for instance, Jónsson 1991, who argues for a head-movement analysis). Thus, while SF could be seen as an argument for the existence of the EPP in impersonal constructions in Icelandic, the matter does not seem to be fully settled yet and alternative accounts of this phenomenon are conceivable as well.

To conclude, Icelandic and German both allow constructions in which a nominative argument remains inside the vP/VP throughout the derivation. The Agree approach, together with a language-specific setting of the EPP, provides a straightforward account of these cases. Accounts that require a specifier-head relation for Case/agreement licensing, by contrast, are faced with the question of how nominative Case and agreement are licensed in these cases (in particular, since covert movement is excluded). To account for VP-internal nominatives, two types of approaches have been suggested, which I will discuss in turn in the next two sections. The first approach (section 3) shares with the account proposed here the concept that nominative Case/agreement are uniformly licensed by T, but differs in that licensing has to involve a specifier-head relation. To account for VP-internal nominatives, a null TP-expletive is postulated that mediates licensing between SpecTP and the VP-internal argument. The second approach (section 4), by contrast, gives up the idea that Case/agreement licensing is universally tied to a functional head such as T. According to this approach, languages like German lack a functional TP domain altogether and Case/agreement is determined by the verb itself. I will compare these approaches to the Agree approach suggested here and conclude that neither the postulation of a null expletive nor the assumption that languages differ in the way Case/agreement are licensed is motivated.

3. Against (True) TP-Expletives in German and Icelandic.

A common account of VP-internal nominatives is to assume that these structures involve an empty pro subject, which checks the EPP and transmits nominative Case to the VP-internal argument (see Safir 1985a, 1985b, Sternefeld 1985, Koster 1987, Grewendorf 1988, 1990, Cardinaletti 1990, Jónsson 1996, Haeberli 2002, among many others). This is illustrated in 20a for the German example 14b, and in 20b for Icelandic example 19a.

Although it is difficult (if not impossible) to argue against silent elements, I would like to give some reasons why this approach is unsatisfactory (see also Haider 1985a, 1985b, 1991 for critique of these types of approaches). My basic claim is that all syntactic and semantic evidence points to the conclusion that there is no pro in these contexts. While there are true TP-expletives and true PF-expletives in German, both of which have independent motivation, a pro expletive postulated as in 20a would be different in that there is no evidence for it. In particular, this type of expletive would have to be defined as an obligatorily covert element that can receive Case and check the EPP, but which is otherwise invisible for all other syntactic and semantic purposes. While the assumption of such an element is, of course, possible, one has to ask whether the stipulation of an obligatorily invisible element that does no more than save the claim that Case licensing requires a specifier-head relation is motivated, in particular, in light of the existence of an alternative approach—the Agree approach developed here.

Let us look at the distribution of different types of expletives. A well-known observation (see Maling and Zaenen 1978, SigurÐsson 1989, Vikner 1995, Jónsson 1996, Bobaljik and Jonas 1996, Bobaljik and Thráinsson 1998, among many others) is that overt expletives in German and Icelandic are only possible in SpecCP (see 21a for German, 22a for Icelandic) and are excluded in SpecTP (see 21b, 22b). This contrasts with English (and Mainland Scandinavian) as shown in 21c and 22c.

A straightforward account for these expletives is to assume (following Breckenridge 1975, Thráinsson 1979, Lenerz 1985, Grewendorf 1989, Bobaljik 2002, and others) that CP-expletives in German and Icelandic are simply phonological fillers of the initial position (SpecCP) when no overt XP has moved there. I will refer to these expletives as “PF-expletives.” That is, PF-expletives are not syntactic elements, but are rather inserted at PF to satisfy an EPP-like requirement that certain positions be filled (SpecTP in English, SpecCP in German/Icelandic; see Chomsky 2000, Fanselow and Mahajan 2000, and Roberts and Roussou 2002 for the assumption of an EPP feature on C). The assumption of PF-expletives is motivated by the fact that these elements do not participate in any way in the syntax and semantics of these constructions.19

This claim has to be qualified in the following way. Icelandic and English expletive constructions show definiteness effects (German generally lacks them, except in certain special contexts, see Haeberli 2002). While these effects are clearly related to the expletive construction in some way, there is no reason to assume that they are triggered by the expletive itself. Rather, both the insertion of a PF expletive and the restrictions on the interpretation can be seen as the result of the same property—the low position of the non-expletive DPs and the lack of a topic.

Although German does not allow overt TP-expletives in contexts such as the one in 21b, there are some instances where we find es ‘it’ in SpecTP: weather-it as in 23a, the existential es gibt ‘there exist’ construction in 23b, and certain motion and experiencer constructions such as 23c (see Haider 2001 for the latter).

Importantly, however, these cases do not represent true cases of expletives, but are best analyzed as involving (quasi-) argumental es (see Chomsky 1981). There are two reasons to assign (quasi-) argument status to these occurrences of es. The standard argument for the argument status of es in 23 comes from its potential to control PRO. Assuming that only arguments can control PRO, examples in 24 provide evidence that it in these examples qualifies as an argument.

The second argument comes from the distribution of accusative case. Although the details of how Case is determined differ substantially across theories, there is a common idea that accusative is only possible in German when there also is an (underlying) external nominative argument (see Haider 1985a, 1985b, Marantz 1991, Sternefeld 1995). Hence, the prediction is that if an expletive is an argument that bears nominative Case and thus functions as a “Case competitor,” other DPs in expletive constructions should occur with accusative. Crucially, this prediction is borne out for syntactic expletives but not for PF-expletives. As shown in 21a and 25a, only nominative is possible on the non-expletive DP in PF-expletive constructions, and accusative is strictly prohibited. By contrast, in constructions with syntactic expletives (weather-it, existential, motion, and experiencer constructions) only accusative is possible, as shown in 25b–d.

Hence, we have good reasons to assume that the expletives in 23 are present in syntax as they participate in the computation of Case. PF-expletives, by contrast, have no effect on the Case computation, which follows if they are not present in syntax but only inserted at PF.

Turning to Icelandic, we find that the constructions corresponding to the German syntactic expletives have the same Case properties. However, no overt expletives are present, as shown in 26.

The interesting observation made in Haider 2001 is that the verbs alowing an accusative argument in the (apparent) absence of a competing nominative argument in Icelandic are very similar to the verbs allowing overt TP-expletives (that is, syntactic expletives) in German. This fact, together with the untypical Case pattern, indicates that Icelandic, like German, has syntactic expletives. However, in contrast to German, these expletives are covert. Note that for these constructions, the postulation of an empty expletive is justified by the syntactic properties, not by a theory-internal claim.

Coming back to the issue at hand, namely, whether there are covert expletives in 20, the only way to make sense of this assumption is to assume that pro would be an expletive of the PF-kind in these cases, since it does not trigger accusative Case on the VP-internal DP and does not seem to be present in the syntax for control and binding purposes. This raises the question, however, how a PF-expletive can transmit Case and how it can be—in fact, must be—covert.

To conclude, the assumption that there is a covert expletive in constructions where no argument raises to SpecTP (overtly or covertly) might save the claim that German and Icelandic, like English, are subject to the EPP, and that Case/agreement are checked in a specifier-head configuration. However, this approach raises several questions regarding the motivation and properties of these expletives. The fact that they must be silent and do not appear to be present in syntax (in contrast to true syntactic expletives that do exist in these languages) strongly suggests that they are artifacts of the theoretical claims rather than true grammatical entities. An account such as the one advocated here, which does not require these entities, seems thus more promising.

4. Against a TP-less Clause Structure for German.

I have argued that the distribution of nominative arguments in German (and tentatively Icelandic) follows straightforwardly if we assume that Case/agreement are licensed via Agree. The advantage of this account is that it allows us to simplify the grammar: no language specific assumptions about the clause structure of German are necessary and Case/agreement licensing is subject to a cross-linguistically uniform mechanism—Agree. Thus, so far, we have seen that it is not necessary to postulate that German (in contrast to English) lacks an inflectional domain (as suggested in Haider 1993). In this section, I argue that this difference between English and German is also not motivated.

4.1. Long Passive.

In this section, I provide evidence for the existence of a VP-external functional domain responsible for Case/agreement licensing in German. Let me start with some background. In German (as in English), object Case depends on the presence versus absence of an external argument, which in turn depends on the voice properties of a predicate. Thus, active non-unaccusative predicates license accusative on the object, whereas passive and unaccusative predicates do not license accusative but require nominative on the underlying object. Under the approach taken here, this difference is due to the presence versus absence of vP: when vP is present, the object Agrees with v (which is the closest Case/agreement head), resulting in accusative, as shown in 27a. When vP is absent (or inactive), the object Agrees with T, which results in nominative (see 27b).20

I assume, for simplicity, that passive and unaccusative constructions lack a vP altogether, hence the only Case assigner is T (see Zwart 2001 for a similar claim). Alternatively, one could assume that passives and unaccusatives project a vP or at least a v0, but that this v0 cannot assign structural Case.

If there are no functional heads such as v or T, the difference between nominative and accusative has to be seen as a property of the lexical argument structure of the predicates involved. That is, the active/passive difference is encoded in the verb's argument structure, which then in turn determines whether the object receives accusative or nominative, as shown in 28. I refer to this view as LEXICAL CASE ASSIGNMENT (for simplicity, I abbreviate the argument structures as ACTIVE or PASSIVE).

I believe that these two approaches can be distinguished empirically. Assuming functional Case assignment, Case is affected by the nature of the VP-external functional domain (that is, presence versus absence of vP). Under the lexical Case assignment view, by contrast, Case is assigned by the argument structure properties of the selecting verb and the VP-external environment should not have any effect on Case-assignment.

These predictions can be tested in certain infinitival constructions, namely so-called restructuring infinitives (RIs). Such infinitival complements display “clause union” effects with the selecting (matrix) verb (see Aissen and Perlmutter 1983, Rizzi 1978, Wurmbrand 2001, and references therein). Typical (lexical) verbs in German that can select RIs include versuchen ‘try’ and vergessen ‘forget’. A special property of RIs is that the Case of the embedded object depends on properties of the selecting matrix predicate. In German, the Case of the embedded object depends on the voice properties of the matrix predicate (see Wurmbrand 2001 for similar phenomena in Romance and Japanese). If the matrix predicate is active (and non-unaccusative), the embedded object obligatorily occurs with accusative case, as shown in 29.

If the matrix predicate is passivized or unaccusative, the embedded object takes nominative case and correspondingly controls agreement on the matrix auxiliary.21

For non-pronominal DPs, accusative case is morphologically distinct from nominative only in the masculine singular. Since singular agreement is the default in impersonal constructions (including impersonal passives), only plural marking is unambiguously agreement. Case and agreement can be shown simultaneously by using coordinated DPs (see Wurmbrand 2001:19). However, since this adds unnecessary complexity to the examples and since agreement in German is only with nominative DPs, I do not use examples with coordinated subjects here. For the purpose of this paper, it is sufficient to note that even where case is not marked overtly, agreement with a DP is an unambiguous indicator that the DP bears nominative case.

It has been occasionally suggested that the long passive construction is “marked,” and thus that no conclusions can be drawn from its properties. However, data collected from a corpus search show that long passive is a frequently occurring construction and is felt by many speakers to be natural in context (see http://wurmbrand.uconn.edu for the results of the corpus search). More to the point, the properties of the construction (including the scope contrasts discussed in Bobaljik and Wurmbrand 2005) are uniform across speakers: of approximately 25 speakers consulted, even those speakers who claim to find the construction itself marked nevertheless find the scope judgments to contrast as indicated, in some cases remarkably sharply. The fact that judgments are uniform on a “marked” construction constitutes in my view a strong prima facie argument that the scope properties must follow from properties of grammar and not from extra-linguistic considerations. (I am not aware of any available alternative explanation.)

The examples in 31 (see Haider 1993) make the same point with an unaccusative restructuring predicate gelingen ‘manage’, which takes a dative experiencer argument.

The Case/agreement properties in RIs can be straightforwardly accounted for assuming functional Case assignment. The analysis of RIs I assume is illustrated in 32. RIs are represented as bare (to–) VPs, lacking CP, TP, and importantly, vP—the functional projection associated with accusative case. Assuming that RIs lack a structural Case assigner/position immediately accounts for the Case dependency noted above. If the matrix predicate is an accusative assigner, the embedded object receives accusative, as in 32a; if the matrix predicate lacks an accusative assigner (that is, when it is unaccusative or passive), the embedded object receives nominative, as in 32b. (For further arguments that RIs are VPs (or something a tiny bit larger) lacking all higher functional projections, see Wurmbrand 2001).

Under the lexical Case assignment view, however, it is not a priori clear how the non-local Case dependency in RIs can be accounted for. Note that crucially the infinitive is active in the long passive/unaccusative cases in 30 and 31 (to repair, not to be repaired), and hence VP-internal Case assignment should be the same as in 29, contrary to fact. The only way to account for the Case dependency of the embedded object with the higher predicate is to assume that the restructuring verb and the infinitive form a complex predicate (that is, a lexical or syntactic V-V compound), where the argument/event structures/theta-grids of both predicates are combined as a consequence of this complex predicate formation (see Haider 1993, 2003 for an explicit account along these lines for German). Complex predicate formation (in particular argument structure merger) then guarantees that restructuring constructions behave essentially like simple predicates.

Complex predicate approaches of this sort, however, have been challenged in several works (see, for instance, Wurmbrand 2001, to appear, Bobaljik and Wurmbrand 2004, to appear). In these works, it is argued extensively that the infinitive and the restructuring predicate form independent argument and event structures which have to project separately in syntax. I summarize some of the arguments in the next section.

4.2. Against a Complex Predicate Approach to Restructuring.

One question raised for the complex predicate approach, for instance, is that both predicates form independent events, which can be modified by event adverbials such as again, × many times. Similarly, the infinitive and the matrix predicate can be from different aspectual/Aktionsart classes, as illustrated in 33. 33a shows that restructuring constructions can involve an in- and a for-adverbial at the same time. Since a for-adverbial cannot modify a telic event such as catch the fish, as in 33b, it has to be the case that the for-PP modifies the event of trying to catch the fish, as in 33a. By contrast, in-adverbials cannot modify non-telic events, as in 33c, hence the in-adverbial in 33a cannot modify the trying event but only the event of catching the fish.23

This example might be acceptable if it is understood as “They tried to do the exercise in an hour,” in which case there is a (silent) telic event (do the exercise), which can be modified by the in-adverbial.

If we compare the complex predicate approach with the analysis proposed here, we get the structures in 34.

Assuming that modification targets syntactic structure, the VP-complementation approach correctly predicts that (i) both in- and for-adverbials are possible simultaneously in restructuring constructions where the two predicates differ in telicity; (ii) in sentences such as 33a, the in-adverbial can attach to the lower predicate since catch the fish constitutes an independent VP—a telic accomplishment—that can be modified by an in-adverbial but not a for-adverbial; (iii) the matrix predicate can be modified by a for-adverbial only since it is non-telic. Hence, this approach correctly predicts the distribution in 33a versus 33d.

The complex predicate approach, by contrast, has to explain how two adverbials are possible, given that there is only one complex try-catch event. If anything, it seems that this approach would predict the opposite order of adverbials: in-adverbials require a telic VP, which would be the VP including the definite object. For the for-adverbial to find a non-telic attachment place, it seems the only option would be the complex head itself—that is, the structure before the object is merged in. Thus, one might expect that the for-adverbial should be lower than the in-adverbial, yielding the structure in 33d rather than the one in 33a. In sum, unless modification and syntactic structure are entirely distinct, it seems that the complex predicate approach is not equipped to account for the distribution of event modifiers.

Furthermore, it can easily be shown that the restructuring predicate and the infinitive do not form a complex head. As illustrated in 35, the two predicates are not adjacent (see Wurmbrand 2001 for other problematic cases). Moreover, since the infinitive can be topicalized on its own (stranding the nominative object and the restructuring verb), we have strong evidence that the infinitive constitutes an XP to the exclusion of the matrix verb. Thus, restructuring clearly does not entail complex head formation between the restructuring verb and the infinitive.

Thus, both constituency tests such as topicalization and the argument and event structure properties point strongly to the conclusion that a restructuring infinitive constitutes a VP on its own (that is, excluding the matrix predicate). In my view, this is rather devastating for complex predicate approaches. Given that (at least certain) restructuring constructions cannot involve complex predicate formation, we are back to the question of why the Case of the embedded object is dependent on the voice properties of the higher verb. Assuming that Case is determined solely by the lexical argument structure of a verb then makes the wrong prediction for the passive restructuring cases discussed here, whereas the claim that German, like English and Icelandic, projects a VP-external Case/agreement licensor correctly predicts the distribution of Case in these constructions.

4.3. Are TP-less Structures for German Motivated?

The final argument in favor of a VP-external functional domain in German is a conceptual argument. A Haider-style analysis is faced with the question of how to justify the fact that typologically quite similar languages differ so significantly in their clause structure, as well as in the way tense is represented and Case/agreement are licensed. Haider (2005) suggests that the difference follows from one simple typological difference: German is a head-final language, whereas English and Icelandic are head-initial languages. I cannot reproduce the details of the analysis here, but I summarize the major claims of Haider 2005 and Haider and Rosengren 2003, and show that this view is not tenable.

According to the theory presented there, a head-initial VP structure requires the presence of a VP-external functional projection for structural licensing purposes. From this it follows, among other things, that VO languages have the EPP, non-argumental TP-expletives, and quirky subjects. In head-final languages, by contrast, the tree geometry has the effect that no VP-external licensing is required, and hence no VP- external functional Case/agreement domain is projected. The lack of such a domain in German then explains indirectly why German lacks EPP effects, non-argumental TP-expletives, and quirky subjects. Obviously, if this system is correct it offers an attractive way to derive the clause structure and licensing differences between German and English/Icelandic from one simple difference—directionality. However, on closer scrutiny, we find that this typological account runs into serious problems, which question the validity of the generalizations and hence the typological explanation for the alleged differences between German and English/Icelandic.

First, as Haider notes, directionality plays only an indirect role in determining the distribution of expletives and the EPP. According to Haider, the following one-way implication holds. If a language lacks expletives and the EPP, the language has to be a head-final language. That is, the head-final setting is a necessary condition for the lack of these properties but not a sufficient one. In other words, not all head-final languages lack expletives/EPP. This weakening of the causal relation between directionality and expletives/EPP is necessary to accommodate Dutch (and, as we will see below, Afrikaans and West Flemish). A well-known difference between Dutch and German is that Dutch allows expletives in cases where they are prohibited in German. This is shown in 36. In contrast to English there, however, Dutch er is optional (at least for some speakers; see, for example, Hoekstra 1984, Koster 1987, and Haeberli 2002).

It should be noted, however, that there is some debate about whether Dutch er is a true (subject) expletive. Bennis (1986) and Koeneman (2000), for instance, argue that er is an expletive adverb that is not associated with the subject (position). If this view is adopted, one could, in fact, maintain the claim that Dutch patterns with German in that both languages lack true subject (that is, TP) expletives. However, turning to other head-final languages, we see that the problem indeed arises—hence, a weakening of the correlation between expletives and directionality is necessary. One such language is Afrikaans. As argued in Conradie 2005, Afrikaans differs from Dutch in all the criteria Koeneman (2000) uses to argue for the adverbial status of Dutch er. I only reproduce two of Conradie's arguments here (for further differences between Dutch and Afrikaans, see Conradie 2005).

First, Conradie shows that Afrikaans daar can occur in positions where other similar adverbs cannot occur, as shown in 37.

Secondly, Koeneman (2000:191ff), following Bennis 1986 argues that Dutch er constructions, like other Germanic expletive constructions, impose the restriction that the associated argument cannot express old information. However, in Dutch this restriction affects both the subject and the object; that is, neither argument may refer to old information (see 38a, which is odd as an answer to the question How are things with your friend?). As shown in 38b, this is not the case in Afrikaans—daar only imposes a restriction on the subject and the object can refer to old information. Thus, Afrikaans there-constructions behave like true TP expletive constructions—daar is a true subject (that is, TP) expletive and not an adverb.

Afrikaans then represents a case of a head-final language with true TP-expletives—that is, Afrikaans would require a VP-external TP-domain despite its head-final status. To keep Haider's generalization, one might suggest that Afrikaans simply is not a head-final language and hence behaves like an English-type language regarding expletives. However, while this is an option in general (see Robbers 1997), it would not be an option in Haider's system. The reason is that Afrikaans is a verb cluster language (see Robbers 1997, Wurmbrand 2004b, 2006), which, according to Haider, entails that the language is head-final.

An even stronger case for the necessity of a VP-external TP-domain in a head-final language comes from West Flemish. West Flemish behaves like English in that TP-expletives are required in cases where no DP subject occupies SpecTP, as shown in 39 from Haeberli 2002:216.

One might again speculate that West Flemish is a head-initial language. Although this claim would again contradict the fact that West Flemish is a verb cluster language (see Haegeman 1994, Haegeman and van Riemsdijk 1986, Wurmbrand 2004b, 2006), let us set verb clustering aside for the moment and look at another head-final property, namely scrambling.24

Independently of the issues discussed here, the claim that scrambling is restricted to head-final languages raises questions for Slavic and other head-initial scrambling languages (see, for instance, Bailyn 2001). Furthermore, as shown in the papers in É. Kiss and van Riemsdijk 2004, the claim that verb clustering is restricted to head-final languages is problematic in light of Hungarian, and possibly other Germanic languages that have been argued to be head-initial. While these questions might be seen as quite serious problems for the theory offered in Haider 2005 and Haider and Rosengren 2003, I would like to set these issues aside and assume here for the sake of argument that the theory is valid in deriving the differences regarding VP-external Case/agreement licensing in head-initial versus head-final languages.

Crucially, however, scrambling (as defined in Haider 2005, Haider and Rosengren 2003) is not always impossible in West Flemish. In particular, as Haeberli shows, scrambling is possible in exactly (and only) the cases that involve an expletive construction shown in 41.25

Note that the assumption that the examples in 41 involve object shift rather than scrambling—which would be motivated by the fact that although the order between the subject and the objects can be inverted in 41a–c, the relative order of the indirect and direct object cannot be reversed according to Haeberli—is not available in Haider's system, since it is crucial in that account that object shift does not change the order of arguments and can only apply if the objects are preceded by the verb.

West Flemish thus shows very clearly that head-final languages must allow the projection of a VP-external functional domain.

The question arising at this point is what determines the distribution of expletives/EPP, and hence of a VP-external functional domain. If it is assumed that head-final languages can project a TP-domain, it seems that the explanation for why German lacks this domain disappears again. In other words, if the presence of the TP-domain has nothing to do with the directionality parameter but is essentially determined by a language specific setting, there is no reason why German should be different. We are thus back to the question of how the difference in clause structure suggested for head-final German, in contrast to head-final Afrikaans and West Flemish (and potentially also Dutch), can be motivated.

The second and more serious problem for the typological approach comes from Icelandic. Recall that according to Haider 2005, the lack of TP-expletives and EPP entails that the language is a head-final language (since only OV languages can lack the TP domain). Icelandic is claimed by Haider to pattern with English in having non-argumental TP-expletives and the EPP. As shown in 42a, some overt element has to occupy SpecTP in English; if no DP moves there, an expletive must be inserted. Haider's claim about Icelandic is based on 42b.26

Haider marks this example as ungrammatical without the expletive in the text, but notes in a footnote that speakers do not find the expletive-less structure impossible. Since this is also in accordance with the facts noted in the literature, I do not use Haider's notation.

Furthermore, examples such as 43b and 44 (repeated from 19) also seem to indicate that Icelandic lacks the EPP. In these examples, SpecTP is not filled at PF and—given that these examples force low scope of the nominative arguments—also not at LF (that is, it cannot be assumed that covert movement applies).

Thus, there seems to be no basis for grouping Icelandic with English and not with German. As discussed in section 3, the only way to maintain the claim that Icelandic has the EPP is to postulate a covert pro in 43b and 44, which I have argued to be unmotivated given the Case properties. However, even if we set these problems aside, an empty pro would not solve the problem here. If one were to assume a silent pro in Icelandic, it would not be clear why there should not also be one in German. Since the overt distribution of expletives and subjects gives us no reason to assume that Icelandic patterns with English and not with German (on the contrary, it seems that Icelandic looks very much like German), the assumption that Icelandic has expletive pro but German lacks it would be purely stipulative.

Table 1 summarizes the distribution of TP-expletives, verb clusters, and scrambling/object shift. As shown in the table, there is no correlation between the directionality of a language and the existence of TP-expletives and hence the EPP. There are head-final and head-initial languages that require TP-expletives, and there are head-final and head-initial languages that lack them. Furthermore, assuming that the West Flemish facts discussed above are instances of object shift, again both head-final and head-initial languages allow this process.

To conclude, although the typological explanation for why German does not display EPP properties is promising at first sight, it runs into serious problems when we look beyond German. It seems that, at this point, we have to conclude from the cross-linguistic facts that whether a language displays EPP effects or not cannot simply be predicted from the directionality settings but requires a language specific assumption. That is, German and Icelandic lack the EPP, whereas English, Afrikaans, and West Flemish are EPP languages (leaving open the status of Dutch at this point). Since both groups involve head-final and head-initial languages, the system offered in Haider 2005 has to add a language specific assumption regarding the EPP, exactly as I have suggested in this paper. Again, an account assuming a TP-less structure for German is faced with the question whether it is motivated to assume a radical difference in clause-structure, as well as the way tense is represented and Case and agreement are licensed—particularly since the alternative system argued for here seems to provide a simpler solution. All we need to account for the German/English differences is the mechanism of Agree together with a language specific setting of the EPP.27

Obviously, this account does not make any predictions for the difference in the availability of verb clustering and scrambling in English versus German. However, as observed in note 24, it remains to be seen whether the claim that scrambling is only found in head-final languages is correct. The same is the case for verb clustering (see É. Kiss and van Riemsdijk 2004).

5. Conclusion.

In this paper, I have compared various Case/agreement licensing approaches and concluded that the Agree approach fares best in light of certain constructions in German (and potentially also Icelandic). In particular, I have argued that the low (that is, vP/VP-internal) PF and LF position of nominative arguments in certain constructions provides evidence for the necessity of Agree. Since there is no overt expletive in these constructions and movement of the nominative argument to SpecTP cannot occur (either overtly or covertly), Case/agreement can only be checked via Agree. Under this approach, SpecTP remains empty throughout the derivation, which leads to the conclusion that the EPP does not hold in German—that is, there is no requirement that SpecTP must be occupied by overt (or covert) material. Thus, the EPP cannot be seen as a universal requirement. Furthermore, two alternative approaches (null expletive and TP-less structure) have been discussed and I have concluded that these approaches lack motivation and face several empirical problems. The advantage of the approach developed here is that it allows us to provide a unified account of Case/agreement licensing, which seems to be more successful from the point of view of explanatory adequacy.