Introduction

Archaeologists have long recognised the value of historical cemeteries in addressing a wide range of research questions. Studies have covered topics including death, bereavement and commemoration, the development of complex social relationships and identities, reconstructions of wealth, power and status, as well as past health, wellbeing and demographics (e.g. Dethlefson & Deetz Reference Dethlefson and Deetz1966; Cannon Reference Cannon1989; Mytum Reference Mytum1989, Reference Mytum1990, Reference Mytum and Carver1993; Meyer Reference Meyer1993; Bell Reference Bell1994; Tarlow Reference Tarlow1999). Historical and modern pet cemeteries provide similar opportunities to refine our understanding, especially in relation to the development of past human-animal relationships, yet few archaeologists engage with these burial grounds. To investigate whether such cemetery data provide evidence for the changing roles of animals in people's lives and afterlives, this article presents an archaeological survey of four pet cemeteries in England. Interpreted alongside archaeological, historical and sociological literature, the results demonstrate the value of pet cemeteries in furthering our understanding of the continuously changing relationships between humans and animal companions in the post-medieval and modern periods around the world.

The archaeology of pets

Pets, defined as animals who occupy a domestic space and primarily serve as entertainment and companionship for humans (Tague Reference Tague2008: 290), are difficult to identify positively in the archaeological record (Thomas Reference Thomas and Pluskowski2005; Sykes Reference Sykes2014). Although skeletal remains and their archaeological contexts offer clues, the precise nature of these relationships are difficult to interpret and often inconclusive. Not all pets were given discrete burials, and not all discrete burials recovered by archaeologists are necessarily indicative of an animal companion (Thomas Reference Thomas and Pluskowski2005: 95; Morris Reference Morris2011; Pluskowski Reference Pluskowski2012). Additional skeletal evidence can further inform on past human-animal relationships. Butchery patterns and age-at-death distributions, for example, can indicate whether populations of animals were exploited predominantly for meat, secondary products or for other reasons, while bone pathologies and trauma identified can provide insight into maltreatment or care (Thomas Reference Thomas and Pluskowski2005: 95; Tourigny et al. Reference Tourigny, Thomas, Guiry, Earp, Allen, Rothenburger, Lawler and Nussbaumer2016). Unfortunately, disease and trauma can have multiple aetiologies, rendering it difficult to associate differential diagnoses with a direct human treatment of animals (Thomas Reference Thomas, Powell, Southwell-Wright and Gowland2016). Concepts such as ‘care’ and ‘wellbeing’ are relative and historically specific, further complicating assessment (Thomas Reference Thomas, Powell, Southwell-Wright and Gowland2016: 169). Human-animal co-burials offer additional opportunities to infer the presence of a pet/companion, but these are rare and their meanings can be interpreted in multiple ways (Morris Reference Morris2011). Few are the occasions that pets can be positively identified in the archaeological record.

A history of pet burials and commemoration

Relationships between people and animals can simultaneously vary from purely functional to primarily emotional. Such relationships change over time and space and assume a variety of roles. While certain species, such as cats and dogs, can serve functional roles (e.g. for pest control or security), it is generally agreed that modern pet-keeping began in Britain in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (Ritvo Reference Ritvo1987; Tague Reference Tague2008: 290). Pet ownership then became increasingly common in the Western world across a range of social groups throughout the nineteenth century (Serpell Reference Serpell1986: 51).

For as long as people lived with animals, they needed to manage dead animal bodies. Although dog burials are commonly recovered from prehistoric and Roman sites in Britain, fewer are found in medieval contexts (Morris Reference Morris and DeMello2016: 13), when dog and cat skeletons are more likely to be recovered from refuse deposits (Thomas Reference Thomas and Pluskowski2005). Not all animal bodies were buried in the post-medieval period: sometimes, dogs and horses were sold to knackers’ yards, where carcasses could be rendered down to produce useful materials, such as skins, and meat for animal consumption (Wilson & Edwards Reference Wilson and Edwards1993: 54). Such post-medieval disposal practices do not necessarily reflect a lack of care for the animals in life, but rather the influence of Christian doctrine on appropriate burial practice, and hygiene concerns related to body disposal (Mytum Reference Mytum1989; Thomas Reference Thomas and Pluskowski2005).

The eighteenth century witnessed the publication of epitaphs and elegies for pets in very small print runs, predominantly in local newspapers. Although these were mostly satirical and generally intended for amusement, some were suggestive of public discourse at the time, and touched on controversial topics, such as whether or not animals had souls and the morality of pet keeping (Tague Reference Tague2008). While a few elite households occasionally held small funerals and erected memorials to deceased pets within their private gardens (Thomas Reference Thomas1983: 118), the first public pet cemetery in Britain appeared in the late nineteenth century, in the affluent London borough of Westminster. Following the death of a dog named Cherry in 1881, its owner asked a gatekeeper at Hyde Park whether the dog could be buried there. A space was allotted in the gatekeeper's personal garden, where, over the next few decades, hundreds of other dogs were interred (Hodgetts Reference Hodgetts1893: 630) (Figure 1). Publicly accessible pet cemeteries subsequently spread across Britain throughout the twentieth century.

Figure 1. Surviving gravestones from Hyde Park Pet Cemetery (photograph by E. Tourigny, taken with permission from The Royal Parks).

Historians and geographers have recognised the value of British pet cemeteries in studying past human-animal relationships, providing much-needed discussion on the meanings behind the spaces occupied by these graves, the human emotions involved in animal commemoration, and how pet cemeteries reflect past and current social values (Howell Reference Howell2002; Mangum Reference Mangum, Denenholz Morse and Danahay2007; Kean Reference Kean, Johnston and Probyn-Rapsey2013; Lorimer Reference Lorimer2019). These studies provide important historical context and theoretical foundations for an archaeological survey. Other scholars have examined pet cemeteries elsewhere in the world, adopting anthropological and sociological approaches to their studies, without necessarily drawing on the substantial archaeological literature on cemetery recording methods and data analyses (e.g. Chalfen Reference Chalfen2003; Brandes Reference Brandes2009; Gaillemin Reference Gaillemin2009; Veldkamp Reference Veldkamp2009; Ambros Reference Ambros2010; Pregowski Reference Pregowski and DeMello2016a; Bardina Reference Bardina2017; Schuurman & Redmalm Reference Schuurman and Redmalm2019). This article takes a more systematic approach to the recording of animal burial grounds, comparing results to contemporaneous human burial practices and examining changing commemoration practices. The resulting discussion demonstrates how other disciplines can make use of archaeological approaches to recording cemeteries and the resulting data analyses.

Methods

Tarlow (Reference Tarlow1999: 2) describes gravestones as “history and archaeology; both text and artefact. They are both deliberately communicative and unintentionally revealing”. As with human burial grounds, pet cemeteries represent locations where social relationships are negotiated and reproduced in the gravestones—whether intentionally or not. As evidenced in the works of Howell (Reference Howell2002) and Kean (Reference Kean, Johnston and Probyn-Rapsey2013), historical British pet cemeteries contain clues that reveal human attitudes towards animals, but we need a systematic method of studying the materiality of pet cemeteries in order to examine properly the extent to which they represent wider social trends. Following the standards described by Mytum (Reference Mytum2000) for recording human cemeteries, I have recorded all of the extant gravestones present in four British pet cemeteries. Inscriptions and designs were photographed and recorded for each grave marker. Many gravestones were damaged, buried or toppled, or their inscriptions were eroded. Inscriptions were only transcribed when legible. The date of death is assumed to be the same as, or near to, the date of gravestone erection. Gravestones with illegible inscriptions are omitted from analyses, when necessary. Over the years, some gravestones were relocated to different sections of their respective cemeteries to accommodate the development of new footpaths and/or for aesthetic reasons. This is common practice in cemeteries (Tarlow Reference Tarlow1999: 14) and does not affect the conclusions drawn here. The following sections discuss the data according to research themes, highlighting changing human-animal relationships and demonstrating potential contributions to further research.

The sample includes some of the largest pet cemeteries in the country, representing burials from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century (Table 1; Figure 2). These include England's first public pet cemetery at Hyde Park, a large suburban burial ground in Ilford and two cemeteries—Jesmond Dene and Northumberland Park—in the north-east. The cemeteries surveyed were chosen for their size and accessibility; together their gravestones cover a 100-year period. The results demonstrate the usefulness of such an approach to the study of human-animal relationships. They do not, however, represent a complete analysis of the complex ways in which people interacted with animals across time and space. Most gravestones were erected between 1890 and 1910, and between 1945 and 1980 (Table 2). The concentration of data between these two periods complicates any observation of trends from the early to mid twentieth century. While few nineteenth-century gravestones note the species of the interred animal, Hodgetts (Reference Hodgetts1893) identifies the Hyde Park grounds as a cemetery for dogs. The majority of recorded gravestones in this study are for dogs, although an increasing proportion of cats are represented as we progress through the twentieth century.

Figure 2. Location of recorded pet cemeteries: 1) Hyde Park; 2) People's Dispensary for Sick Animals cemetery, Ilford; 3) Jesmond Dene; 4) Northumberland Park (map by N. Dabaut).

Table 1. Cemetery information.

Table 2. Number of recorded stones by decade (determined by earliest date of death on gravestone).

Pets, friends or family?

The vocabulary used on gravestones reveals the nature of the relationships between the buried animals and those who commemorated them. In all periods, most stones are quite simple, featuring only the name of the animal, relevant dates and perhaps an opening statement such as ‘In memory of’. A few include further details about the relationship. Many of the earlier graves refer to animals as pets, friends or companions. Such references continue to the end of the twentieth century, but with differences in how commemorators refer to themselves. As was common practice in the nineteenth century, gravestones in human cemeteries often include the names or initials of those erecting the monuments (Tarlow Reference Tarlow1999: 66). Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century pet gravestones are no different, often including the names or initials of those erecting the stones. Occasionally, the commemorators’ names feature more prominently than those of the buried animals. A few graves reference the animal leaving behind their ‘sorrowing mistress’. Naming the commemorator continues throughout the twentieth century, although by the mid century, proper nouns and initials are often replaced with pronouns such as ‘Mummy’, ‘Dad’, ‘Nan’ or ‘Auntie’, suggesting a familial relationship with the animal (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Vocabulary used in reference to the commemorator (figure by E. Tourigny).

Some gravestone texts explicitly describe the relationship, either with introductory statements such as ‘In memory of my dear pet’, or through epitaphs like ‘A faithful friend and constant companion’. The relationships described in the texts sometimes conflict with the commemorator's self-reference. Cooch's (d. 1952, Ilford) epitaph, for example, reads ‘Our faithful pet and companion’, but the commemorator identifies themself as ‘Mummy’. References to animals as family members increase after the Second World War (Figure 4), coinciding with a rise in the use of family surnames on pet gravestones (Figure 5). Some early adopters of surnames put them in parentheses or quotation marks, as if to acknowledge they are not full members of the family, or perhaps to pre-emptively address any criticism.

Figure 4. Types of human-animal relationship mentioned on animal gravestones (figure by E. Tourigny).

Figure 5. The use of family surnames on animal gravestones (figure by E. Tourigny).

The Victorian era represents a watershed for human-pet relationships, marked by a growing discourse on animal welfare and the changing role of dogs in British society, as they became increasingly important figures in the family household (Howell Reference Howell2002: 8, Reference Howell2015). Some scholars interpret the establishment of separate pet cemeteries as representative of pets occupying ‘liminal’ positions within society: a special relationship within the family that is not quite equal to that of the humans involved (e.g. Gaillemin Reference Gaillemin2009; Ambros Reference Ambros2010). Although the separateness of pet and human cemeteries in Britain can be easily explained by the influence of religious doctrine governing human burial grounds, the 100-year record in pet gravestones emphasises how people struggled to identify and label their relationships with animals. Even by the late twentieth century, there was a discrepancy between the role of animals in life, as suggested by their treatment after death and the language used to describe the human-animal relationship. An animal may be considered part of the family, but this belief is not always committed to public text on the gravestone (Pregowski Reference Pregowski and DeMello2016a; Bardina Reference Bardina2017; Schuurman & Redmalm Reference Schuurman and Redmalm2019).

Immortality, spirituality and reunion

Howell (Reference Howell2002, Reference Howell2015) describes how Victorian concepts of heaven changed to become a recreation of the family home in the afterlife—a home in which the dog played a prominent role. While the act of burial and the text on some of the earliest gravestones provide evidence for an increasing belief in animal life after death (Howell Reference Howell2002; Brandes Reference Brandes2009; Gaillemin Reference Gaillemin2009), epitaphs and gravestone designs also reveal an initial hesitance at the direct expression of such beliefs. The language used among those earliest stones is carefully worded so as only to suggest or hope for reunification in an afterlife. The commemorator of Grit (d. 1900, Hyde Park), for example, demonstrates uncertainty in writing: ‘Could I think we'd meet again, it would lighten half my pain’. References to the afterlife increased slightly into the mid twentieth century, but those that do mention it tend to be more assertive. Commemorators of ‘the brave little cat’, Denny (d. 1952, Ilford), for example, confidently wrote, ‘God bless until we meet again’.

Howell (Reference Howell2002: 13) discusses how some Hyde Park gravestones reference the few Bible verses that may tenuously be interpreted as suggesting that animals have souls. Seven gravestones reference Biblical scripture: four reference Luke 12:6 (‘Not one of them is forgotten before God’), another Psalms 50:10 (‘Every beast in the forest is mine, saith the Lord’) and another Romans 8:21 (‘the creature itself also shall be delivered from the bondage of corruption into the glorious liberty of the children of God’). The last stone references John 13:7 to suggest that animal death is part of God's plan (‘Jesus replied, “You do not realize now what I am doing, but later you will understand”’). References to Christianity increase following the Second World War, when noticeably more crosses and epitaphs invoking God's care and protection appear on gravestones (Figure 6). Late twentieth-century cemeteries in the north-east of England contain no references to Christianity or reunification in heaven, countering the trend observed in the London area. This is due to council-run cemeteries not permitting the use of Christian symbols (Coates Reference Coates2012: 75) and further highlights the contentious nature of the belief in an animal afterlife and the influence of religious authority on animal commemoration practices.

Figure 6. The number of references to Christianity and concepts of reunification observed on animal gravestones (figure by E. Tourigny).

Although the lack of Christian symbols on Victorian gravestones may be surprising, it is notable that such symbols also appear relatively infrequently in contemporaneous human cemeteries. Tarlow (Reference Tarlow1999: 73–75 & 143) observes that Christian symbols and references to a heavenly reunion are more reflective of twentieth-century cemetery trends.

Attitudes towards animal death

The early nineteenth century witnessed radical transformations in human burial practices, as overcrowded urban graveyards led to the creation of for-profit cemeteries outside of city centres (Curl Reference Curl1972: 181–82; Mytum Reference Mytum1989: 284). A changing relationship between the living and the dead is also evident in an increased desire by the bereaved to visit the grave and for burials to remain perpetually undisturbed (Tarlow Reference Tarlow1999: 145). People began spending considerable sums of money on funerals and more ostentatious gravestones. These demonstrate a desire to mourn publicly, resulting in a higher number of gravestones relative to previous centuries (Tarlow Reference Tarlow1999). Although the majority of people opted to bury their animals in private gardens, the creation of pet cemeteries and the emotional epitaphs on a few early animal gravestones suggest an increasing desire for public expressions of grief following a deep loss (Howell Reference Howell2002; Kean Reference Kean, Johnston and Probyn-Rapsey2013). The need to express grief following the loss of a beloved animal, however, was at odds with socially acceptable beliefs of the time, as a disbelief in animal souls conflicted with the need to mourn a beloved individual's death (Tague Reference Tague2008: 298). Howell (Reference Howell2002: 7) argues that the establishment of the first public pet cemeteries represent human desire for an animal afterlife. While only a few early gravestones mention the desire for reunification specifically, the symbolism apparent in many of the gravestone forms and designs suggests that people conceptualised animal death in the same way as human death, through the metaphor of sleep.

Understanding death through the metaphor of sleep featured prominently in the late Victorian era (Tarlow Reference Tarlow1999). Sleep is a particularly attractive and comforting metaphor, as it suggests an impermanent state without being explicit about beliefs concerning the immortality of animal souls. Many of the animal graves at Hyde Park follow trends observed in contemporaneous human burial plots and include both kerbstones and a headstone, as if mimicking a bed. Some even display raised body stones for increased visual effect (Figure 7). Gravestone texts regularly use sleep-related language commonly observed on human memorials, such as ‘Rest in Peace’ and ‘Here lies […]’. Sam's epitaph (d. 1894), for example, reads ‘After life's fitful slumber, he sleeps well’, while Snap and Peter's headstone (d. 1890s) reads ‘We are only sleeping, Master’. Society's attitudes towards death have changed little, as the sleep metaphor is used continuously throughout the twentieth century to conceptualise death, following the pattern observed in human cemeteries (Tarlow Reference Tarlow1999: 109).

Figure 7. Example of the use of body stones, kerbs and headstones to resemble the appearance of a bed in Hyde Park Pet Cemetery (photograph by E. Tourigny, taken with permission from The Royal Parks).

Nineteenth-century human gravestones tended to be large, of various, standardised shapes, and often included secular designs, such as foliate borders, architectural elements (e.g. pilasters and pediments) and symbols of the neo-classical revival (e.g. columns, obelisks, urns). Many were set in beautifully landscaped, garden-like cemeteries (Tarlow Reference Tarlow1999: 69–73). Remarkably, this is not the case in Hyde Park, where gravestones are nearly all of a uniformly small size (averaging: 0.31m in height, 0.24m in width and a thickness of 0.05m). Predominantly cut of the same stone type, they are tucked away in a small, private corner of the park. The majority display the same basic shape, with only six of 471 gravestones having additional decorative elements. The uniformity of gravestones, the lack of decoration and the remoteness of their location suggest that pet burials did not simply reflect another form of conspicuous consumption, but represent an actual desire to bury and commemorate animals.

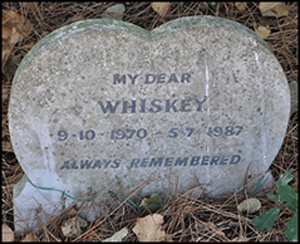

Following patterns observed in human cemeteries, a greater variety of gravestone designs appear in twentieth-century pet cemeteries. Commemorators could select from an increased supply of standardised gravestone shapes, which include foliate borders and bespoke elements, such as engravings of animals and small sculptures (best evidenced at the People's Dispensary for Sick Animals pet cemetery in Ilford) (Figure 8). Human gravestones diminish in size following the First World War (Tarlow Reference Tarlow1999: 152), whereas pet monuments occasionally become larger and more elaborate by the mid twentieth century.

Figure 8. Examples of variation in gravestone design from the People's Dispensary for Sick Animals pet cemetery in Ilford: left) Whiskey (d. 1987); right) Billy (d. 1951) (photographs by E. Tourigny).

As British society became increasingly secular and more tolerant of different religious beliefs during the twentieth century (Brown Reference Brown2009), there was less reluctance to express publicly a belief in animal souls, reunification in the afterlife and the membership of animals within the family. These changes are especially pronounced in the second half of the twentieth century, and are also observed elsewhere in the world. In their assessment of Finnish and Swedish pet cemeteries, Schuurman and Redmalm (Reference Schuurman and Redmalm2019) suggest that fewer references to owners in post-Second World War pet gravestones provides evidence for the acceptance of animals in the family. Furthermore, Brandes (Reference Brandes2009: 107–109) identified an increased use of familial identifiers in later twentieth-century pet burials in Hartsdale, New York.

While it may appear counter-intuitive to witness an increase in religious symbolism in a more secular society, this trend is also noted in contemporary human cemeteries in Britain and other Western countries (Tarlow Reference Tarlow1999; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Sielski, Miles and Dunfee2011). As Anthony (Reference Anthony2016: 361) notes, while human cemeteries became more inclusive in the twentieth century and became more accepting of inscriptions and symbols being used, the gravestones are not necessarily increasingly secular. Pet cemeteries, such as the example in Ilford, show a clear increase in Christian symbolism. Buena Vista pet cemetery in Leicestershire (est. 1977) comprises predominantly standardised wooden crosses as grave markers (Figure 9). The standard use of crosses at Buena Vista and the restrictions on religious symbolism imposed on other cemeteries (e.g. North Shields, Jesmond) suggest that theological orthodoxy was enforced differently across authorities.

Figure 9. Wooden cross grave markers characteristic of the Buena Vista pet cemetery, Leicestershire (photograph by K. Bridger).

Christian symbols are equally sparse in the few early pet cemeteries described outside of Britain. The generally accepted Christian position is that animals do not have souls or spirits, and that animal life is less valued than human life; there is, however, a belief that animals are God's treasured creations (Lewis Reference Lewis2008: 314–15). Despite mirroring human burial customs and hoping for reunification in a Christian heaven, the struggle to define the role of animals in the afterlife continued throughout the twentieth century, both in Britain and elsewhere around the world. Brandes (Reference Brandes2009) notes that most Christian symbols on pet gravestones in Hartsdale, the first pet cemetery in the USA, appear after the 1980s, thus suggesting a more conservative approach compared to London's post-war pet owners. In Moscow, where most people do not believe that animals have spirits or souls, pet epitaphs still suggest a continued life beyond death and reunion with the family, without evoking religious references (Bardina Reference Bardina2017). Paris's pet cemetery banned crosses upon its establishment in 1899. Gaillemin (Reference Gaillemin2009), however, notes that Parisians found other ways to suggest that pets have souls by substituting crosses with hearts, doves and angels or saints. Conversely, many of Japan's Buddhist cemeteries commonly include both human and pet burials, welcoming the idea of pets having souls (Veldkamp Reference Veldkamp2009). Rather than reflecting personal beliefs, prohibited religious symbols are often more indicative of mainstream religious doctrine and political motives.

The need to grieve

The stylistic similarities between early pet cemeteries and Victorian human cemeteries possibly reflect the adoption of ritual practices originally intended for people, where no such rituals existed for animals (Dresser Reference Dresser, Podberscek, Paul and Serpell2000: 102). While some scholars describe the act of burial and commemoration itself as evidence for belief in animal souls (e.g. Bardina Reference Bardina2017), the pet cemetery ‘movement’ also developed out of a need to mourn lost companions in a public manner alongside other bereaved people. The bond formed with an animal can be just as close as that formed between humans (Cowles Reference Cowles and Sussman2016), and the archaeological data indicate that, over time, people have become increasingly comfortable in expressing this bond, and in both grieving and commemorating its loss. While the pet cemetery movement may partly be explained as representing early expressions of belief in animal souls, their purpose may have shifted over time. This is observable in Japanese cemeteries, where funerals for animals have become less about warding off the spiritual vengeance of animal souls and more about meeting increased consumer demand and allowing pet owners the opportunity to remember and mourn the loss of their animals (Veldkamp Reference Veldkamp2009: 333).

Today, people continue to struggle to find an appropriate outlet to express the deep emotional pain that they suffer following the loss of a beloved animal, fearing social repercussions for either anthropomorphising their relationships and being too sentimental, or for being disrespectful of people and religious beliefs (Woods Reference Woods2000; Morley & Fook Reference Morley and Fook2005; Desmond Reference Desmond, Kalof and Montgomery2011; Schuurman & Redmalm Reference Schuurman and Redmalm2019). In the UK, charitable organisations such as the Blue Cross and the Rainbow Bridge Pet Loss Grief Centre offer counselling services to bereaved humans following the loss of their pet. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals website offers explicit reassurance to bereaved pet owners that their feelings of deep sadness, loneliness and isolation are normal and no reason to be ashamed (Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals n.d.). Online forums and digital pet cemeteries provide new venues in which people can express their grief and commemorate their beloved pets. Similarly, these online commemorations can provide scholars with evidence for changing human-animal relationships (MacKay et al. Reference MacKay, Moore and Huntingford2016). Pet-cemetery research puts this grief into historical context, demonstrating to the currently bereaved that they are not alone in their struggles to express their feelings.

Conclusion

The relationships that people develop with animals are partly a product of the cultural milieu in which they form. While people's reactions to animal death have varied across time and space, the treatment of the animal body (Tourigny et al. Reference Tourigny, Thomas, Guiry, Earp, Allen, Rothenburger, Lawler and Nussbaumer2016) and the material culture associated with animal death and commemoration highlight the human perceptions of these relationships. The archaeological data presented in this article demonstrate the wide range of human-animal relationships depicted in pet cemeteries, and their value towards investigating changing behavioural patterns through time. The results illuminate the transition of animals from being pets and companions to becoming family members, and the changing beliefs about the animal's role in the afterlife. They provide testimony to the conflicts between individual beliefs and societal pressures. Pet cemetery studies can further contribute to additional research themes not discussed here, including the differential relationships between social groups (e.g. based on ethnicity, economic status or gender), relationships to changing household demographics, studies of pet life expectancy and changes in naming practices as a reflection of cultural attitudes (e.g. Thomas Reference Thomas1983: 119; Chalfen Reference Chalfen2003; Brandes Reference Brandes2009; Pregowski Reference Pregowski and Pregowski2016b; Inoue et al. Reference Inoue, Kwan and Sugiura2018).

Comparing pet burial practices from cemeteries around the world demonstrates different attitudes towards animals and variation between social and cultural groups. Whether or not gravestones are explicit in their portrayal of human-animal relationships, pet cemeteries demonstrate emotional responses to the loss of a pet. As Schuurman and Redmalm (Reference Schuurman and Redmalm2019) observed in modern Scandinavian pet cemeteries, emotions are often ambiguous, reflecting an uncertainty in defining one's relationship with animals, and identifying what constitutes acceptable forms of grief following the loss of this relationship. The archaeological data presented provide historical context for this conflict in British society, demonstrating how public attitudes have changed over time, and how they are manifested in the material record. Furthermore, pet cemeteries allow us to contextualise our current relationship with animals through comparisons to human burial practices, thus demonstrating how archaeology can contribute to other fields of research. As our relationship with pets continues to change, so do burial practices. Cremation services are becoming increasingly popular, and new forms of material culture related to animal death and commemoration are emerging. These provide us with new opportunities to investigate the material manifestation of our relationship with non-human animals.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Royal Parks for providing access to the Hyde Park Pet Cemetery. The Royal Parks is the charity that cares for London's eight Royal Parks, covering over 5000 acres of historic parkland, buildings and monuments for everyone to enjoy. Thanks to Lisa-Marie Shillito, Scott Ashley and Katie Bridger for comments on an early draft. Thank you to the reviewers for their constructive feedback.

Funding statement

Many thanks to the Society for Post-Medieval Archaeology for the research grant to support this project.