Introduction

In the shadow of Brexit and the rise of populism in Europe and the USA, people tend to draw a straight line to an alienated White working class, angry pensioners, and the unemployed. However, such simplistic explanations overlook the roots and development of complex populist movements and do not fully grasp the support of more than 10 million voters for Marine Le Pen in the 2017 French Presidential Election, more than 5 million for the Alternative for Germany party in the 2017 German Federal Election, and recently, more than 8 million for the Law and Justice Party in the 2019 Polish Parliamentary Election. This paper focuses on the prospect of the Alternative for Germany achieving something that had eluded the radical right in Germany – a federal electoral breakthrough. Before the 2017 Bundestag Election, no right-wing party has managed to pass the threshold for parliamentary representation on the federal level – a failure that can be attributed to Germany’s strong political culture of containment and civic confrontation through large protests and anti-fascist activities (Art, Reference Art2006). Every radical right party in postwar Germany – the National Democratic Party, the German People’s Union, the Republikaner, the Freedom Party, and the Schill Party – has experienced a sudden rise, factional splits, and organizational atrophy, bringing themselves to a political oblivion.

While scholars have given due consideration to AfD voters and party ideology (Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer2015; Schmitt-Beck, Reference Schmitt-Beck2017; Bieber et al., Reference Bieber, Roßteutscher and Scherer2018), there has been little research on the party organization and its internal democratic mechanisms. This gap merits particular attention if we are to understand how intra-party democracy (IPD) may enable a new populist right party to respond effectively to political opportunities and constraints and to establish itself permanently in the political arena. This research builds upon recent scholarship on organizational dynamics in populist parties (Heinisch and Mazzoleni, Reference Heinisch and Mazzoleni2016) and suggests that the Alternative for Germany does not follow the path of hierarchical and centralized decision-making structures, typical for the radical right parties. Rather, the AfD exhibits organizational features enabling members’ political participation, mostly associated with the left and populist party family.

Drawing on original interview and participant observation data, this article argues that the AfD is characterized by diverse mechanisms of internal democracy in policy development and increased grassroots involvement in local communities. The party has adopted a collaborative approach toward policy development, where members participate in distinct stages of designing, deliberating, and approving the party program. The findings of internal democratic dynamics in the AfD can serve as an important addition to the broader literature on populism, and specifically how populism may influence party structures. Parties that conduct their internal affairs in a ‘democratic way’ show to the voters that they have an internal democratic ethos, instead of being entirely controlled by political elites. The perception that the ‘demos’ governs party decisions may add to the party’s credibility as a potential government participant (Mersel, Reference Mersel2006), and in the case of the AfD, fight off Nazi stigmatization and social exclusion. Also, through its grassroots involvement, the AfD attempts to respond to the demand of more citizens’ engagement in politics. By conducting activities intensively in local communities, the party manifests its willingness to respond to issues raised by the citizens and indirectly sends a message of better representation (Gherghina, Reference Gherghina2014).

Populist parties and the question of IPD

Studies of party organization demonstrate that modern parties have transformed into internal cartels led by career professionals, thus relinquishing values and practices originally associated with the mass party such as internal deliberation and leadership accountability (Katz, Reference Katz2001; Blyth and Katz, Reference Blyth and Katz2005; Katz and Mair, Reference Katz and Mair2009). Over the course of the late 20th century, traditional postwar parties have gradually lost their semblance as ‘essential instruments of – and for – democracy and liberty’ and they are experiencing increasing collapse in terms of confidence and trust (Ignazi, Reference Ignazi2017, p. 3). At the same time, survey evidence on party members shows strong support for more membership involvement in policy-making, as well as in candidate and leadership selection. Members in Canadian parties mentioned perceived ‘under-influence of ordinary party members’ as the ‘greatest source of discontent’ (Young and Cross, Reference Young and Cross2002, p. 682). In the British Labor Party, most members preferred active participatory democracy beyond simple voting on proposals, drafted by the leadership (Pettitt, Reference Pettitt2012).

In response to growing political discontent and declining levels of institutional trust, parties have focused on encouraging participation of members and sympathizers in decision-making processes through the adoption of procedures such as membership ballots and primaries (Seyd and Whiteley Reference Seyd and Whiteley2004; Hazan & Rahat Reference Hazan and Rahat2010; Cross and Blais Reference Cross and Blais2012). Nevertheless, there is a continuous trend of party elites retaining significant control over the decision-making processes of leadership and candidate positions (Cross Reference Cross2013; Scarrow Reference Scarrow2015). Increased political participation in parties is ‘atomistic’, as ‘individuals are isolated from one another and engaged in direct communication only with the party center, in a fashion that inhibits their ability to act in common with each other’ (Carty Reference Carty, Cross and Katz2013, p. 19).

IPD is an essential part of the ‘broader rhetoric of democratization, re-engagement and modernization delivered to diverse audiences – both internal and external to the party’ (Gauja, Reference Gauja2017, p. 5). IPD relates to various organizational aspects such as policy decision-making, candidate selection, leadership elections, and intra-party conflicts. In a recent study, Berge and Poguntke (Reference Berge, Poguntke, Scarrow, Webb and Poguntke2017) divided IPD into assembly-based deliberative processes, emphasizing open-ended and participatory discussion, and into plebiscitary mechanisms such as membership ballots and referendums. Internal democracy could strengthen the linkage not only between party members and party elite, but also between citizens and government: ‘by opening up channels of communication within party organizations, the deliberating bodies of the state could be made ‘‘porous’’ … to the influence of deliberations expressed within civil society and the public sphere’ (Teorell, Reference Teorell1999, p. 373).

Comparative research on party organization has shown that some party families have been better at allowing direct participation of their members in the formation of party policies. Green and left-wing parties in Western democracies have been found to manifest high levels of internal democracy. They were followed closely by social democrats, while conservatives exhibited average levels of IPD (Poguntke et al., Reference Poguntke, Scarrow and Webb2016). Since the 1970s and 1980s, European green and new left parties have emerged to challenge the hierarchical nature of the established parties, strongly encourage grassroots involvement in internal decision-making, and foster participatory linkages with social movements (Poguntke Reference Poguntke1987; Tsakatika and Lisi Reference Tsakatika and Lisi2013; Rihoux, Reference Rihoux and Van Haute2016). Similarly, the Workers’ Party of Brazil sought to be internally democratic by employing two-stage convention processes and institutionalizing deliberation at the local level through party nuclei (Keck, Reference Keck1992).

The recent success of populist parties has also caught the attention of scholars investigating how populism may influence party structures. Populism ‘considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite”, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people’ (Mudde Reference Mudde2004, p.543). At the core of populist ideology lies the promise of empowering the ‘people’ in the political decision-making processes: populists urge for the adoption of direct democratic mechanisms that would ‘allow unmediated relationship between the constituencies and the leader’ (Kaltwasser Reference Kaltwasser2014, p. 479). Given that populist parties rely on the notion of representing the people in a more direct way, we would expect these parties to turn more extensively to internal participatory procedures, shifting the influence of decision-making from the ‘party in central office’ and ‘party in public office’ to the ‘party on the ground’ (Vittori Reference Vittori2020). Party members would restrict the power of the party leadership and demand key decisions to be taken by the grassroots.

However, much work on populist right parties suggests that, despite their people-centric claims, these parties are less internally democratic and tend to implement strong personalized leadership structures. Mudde (Reference Mudde2004, p.558) tries to make sense of this inconsistency in the following way: he argues that populist supporters care more about responsive leadership and ‘want politicians who know the people, and who make their wishes come true’, rather than about meaningful participatory opportunities for the grassroots. Roberts (Reference Roberts2007) who looks at the characteristics of populist left parties in Latin America also notes that these parties are characterized with top-down political mobilization and personalistic leadership that ‘challenge elite groups on behalf of an ill-defined “pueblo”, or “the people”’ (Roberts Reference Roberts2007, p. 5). Recently successful populist parties, such as Podemos and the Five Star Movement, have introduced novel participatory processes through digital platforms. However, in practice, such populist organizations still have limited bottom-up deliberation, as members mostly take part in the ratification of pre-arranged decisions by the leadership (Gerbaudo Reference Gerbaudo2019).

When it comes to the populist right party family, scholars have usually agreed on the absence of such internal democratic mechanisms. Most radical right parties ‘display a highly centralized organizational structure, with decisions being made at the top by a relatively circumscribed circle of party activists and transmitted to the bottom’ (Betz Reference Betz, Betz and Immerfall1998, p. 9). One of the best-known radical right parties, the French National Rally (RN), is a model of a highly centralized pyramid-like structure, where IPD is ‘imperfect and infrequent at best’ (Marcus Reference Marcus1995, p. 46) and decision-making is done in a top-down manner (DeClair, Reference DeClair1999; Ivaldi and Lanzone, Reference Ivaldi, Lanzone, Heinisch and Mazzoleni2016). In a similar vein, the Austrian Freedom Party has undergone considerable centralization of decision-making power in the hands of the former leader Jörg Haider (Carter, Reference Carter2005; Heinisch, Reference Heinisch, Heinisch and Mazzoleni2016). The last German populist right party to garner substantial support and steadily poll 6%–8% nationwide in the 1990s, the Republikaner, also experienced little internal democracy. Its leader, Franz Schönhuber, misjudged the importance of balance of power on the grassroots level, tolerated no opinion that deviated from the federal leadership, and prevented the formation of internal interest groups and sub-organizations, the establishment of a youth organization and a republican university association (Grätz, Reference Grätz1993, p. 73).

Despite this general finding, other scholars have noted cases of radical right parties that offer exceptions to this rule, including the Sweden Democrats and the Italian Lega Nord. The Sweden Democrats have focused on collective leadership and provision of limited grassroots involvement in policy formation during party conventions (Jungar, Reference Jungar, Heinisch and Mazzoleni2016). Daniel Albertazzi (Reference Albertazzi2016) also notes that the Lega has adopted an organizational model similar to the mass party, encouraging members to be actively involved on the local level. In 2013, the Lega also moved for the first time to elect its party leader, Matteo Salvini, through closed primary elections, after 22 years of leadership under Umberto Bossi (Sandri et al., Reference Sandri, Seddone, Bulli, van Haute and Gauja2015; McDonnell and Vampa, Reference McDonnell, Vampa, Heinisch and Mazzoleni2016). Nevertheless, these same authors also suggest that IPD is very limited in the Sweden Democrats and the Lega. Populist right parties may frequently present themselves as champions of people-centered democracy; however, empirical findings show that the decision-making is predominantly in the hands of the party leadership and membership participation is usually rare.

Other recent scholarship highlights an important unifying feature of populist party behavior, regardless of political ideology – incorporation of social movement practices and encouragement of participatory venues outside the electoral arena (Caiani and Cisař Reference Caiani and Císař2018; Pirro and Castelli Gattinara Reference Pirro and Castelli Gattinara2018). Movement-electoral interactive dynamics have significantly affected the radical left and left political organizations, as we have observed with practices of citizens’ mobilizations in Syriza and Podemos after the 2008 euro-debt crisis (Della Porta et al. Reference Della Porta, Fernández, Kouki and Mosca2017). Yet the same has also been observed in the case of the French Front National and its relationship with the Ordre Nouveau and other extremist movements (Frigoli and Ivaldi Reference Frigoli and Ivaldi2018), or the close relations between the populist right party Lega Nord and the neo-fascist movement CasaPound Italia (Pirro and Castelli Gattinara Reference Pirro and Castelli Gattinara2018).

The people-centered nature of populist parties thus may be visible in their behavior as hybrid collective actors, using both the electoral arena and movement repertoires to involve the grassroots. However, the radical right party family has been hesitant about engaging with plebiscitary politics and assembly-based organizational processes – contrary to their ideological platforms on direct democracy and empowerment of the membership (Berge and Poguntke Reference Berge, Poguntke, Scarrow, Webb and Poguntke2017). The question remains whether a populist right party such as the Alternative for Germany could provide favorable circumstances for meaningful participation of their party members in internal decision-making. The article addresses this puzzle by examining how the intra-party structures in the AfD help foster organizational ties with alienated citizens, seeking effective channels of political participation.

Methodology and data

Cross and Katz (Reference Cross and Katz2013, p. 8) suggest that IPD is not simply a matter of ‘norms of party membership, or even patterns of intra-party participation’, but also a question of ‘who has real authority over what areas of party decision-making.’ Therefore, we need to look beyond party statutes and address the question of IPD through members’ evaluations of distinct features of intra-party life and analysis of grassroots interactions during real-time party events and conventions.

The results described in this article are based on 11 months of ethnographic fieldwork (September 2018–August 2019) throughout Germany. I relied heavily on snowball sampling to build a network of contacts, arrange interviews, and get access to sources and locations. I have recorded and transcribed 20 semi-structured interviews and compiled extensive notes on conversations with 54 additional participants.Footnote 1 Interviews were analyzed qualitatively and the most important elements relating to the organization, deliberation processes, and grassroots mobilization were presented with illustrative quotations. The interviewees represented a wide a sample of activists, including party leaders, elected representatives in local, state, and federal parliaments, and ordinary citizens, who engage in activities beyond paying yearly party fees. Fifty-one percent of all interviewees were normal party members, not holding leadership positions on the local, state, or federal party levels. Most members claimed they did not belong to an internal faction. Nineteen percent identified with the radical right ‘Flügel’ faction and 36% with the liberal conservative ‘Alternative Mitte’.

Comparing the sample of AfD members to available survey data of party membership (Niedermayer Reference Niedermayer2018), interviewees with university degrees were overrepresented and pensioners were underrepresented. Also, while the survey shows that most AfD activists did not belong to a political party before the AfD (77%), the fieldwork results are skewed toward participants who have been previously involved in parties: 40.5% in the Christian Democrats (CDU), 9.4% in the Free Democrats (FDP), 2.7% in the Social Democrats (SPD), 2.7% in the Left Party, and 2.7% in the Republikaner Party. Such sample bias can be expected in ethnographic studies, where researchers do not have full control over the random selection of participants and rely on their willingness to engage with the research project Table 1.

Table 1. Representativeness of AfD members

Source: Author’s Interview Data; Survey data, Niedermayer, O. (2018), Parteimitglieder in Deutschland. Arbeitshefte a.d. Otto-Stammer-Zentrum, 29, FU, Berlin.

Participant observation was also central to my research. The selection of sites was both ‘pre-planned’ and ‘opportunistic’, as I attended scheduled party events in rural and urban districts from all 16 states and accepted spontaneous invitations to informal gatherings and dinners by party members. To ensure voluntary and informed consent of the participants, I obtained written or verbal consent. I have assigned pseudonyms to the informants for the purpose of anonymity. This research project was approved by the relevant university’s Institutional Review Board. Qualitative research comes with some important challenges, however. Initially, I experienced reluctant participation from party members because they perceived me as a journalist from a left-wing media or a biased representative of a left liberal university. I explained to them my research interest in the party organizational processes. When informants shifted toward emotionally charged topics related to immigration, Angela Merkel’s government, or climate change, I would take a passive role of a listener and attempt to bring back the discussion to party policy development or candidate selection. Often, the conversations felt like no one had ever asked the party members for their thoughts and experiences with the party structures and grassroots involvement.

Since the sample of informants consisted of respondents with a higher political interest than the population in general, it is reasonable to expect party members to ‘perform’ for the researcher in terms of masking their opinions and exaggerating their stories. To avoid socially desirable responding, I framed the questions about IPD in a neutral way and let the interviewees structure their own answers without providing them specific clues. Before conducting interviews, I established rapport with the informants by attending political events and informal gatherings with their families and friends. Good rapport and trust are associated with more honest answers, as respondents would feel more comfortable to disclose sensitive information (Garbarski et al., Reference Garbarski, Schaeffer and Dykema2016; Kühne, Reference Kühne2018). To put into perspective the gathered data, I also relied on participant observation of state and federal party conventions and regulars’ tables (Stammtisch), as well as on analysis of party documents and media reports.

Empirical approach: grassroots participation in party program development

Early field research carried out from June to August 2017 in the states of Baden-Wuertemberg and North-Rhine Westphalia suggested that many AfD members joined the party because they were dissatisfied with the current political establishment, and particularly with the absence of grassroots involvement in them. Since direct democracy and active citizens’ involvement in politics are central claims of the party ideology, should we expect the AfD organization to incorporate internal democratic principles, empowering the grassroots in the decision-making processes?

To explore the role of IPD in the AfD, I focus on mechanisms of participation, deliberation, and pluralism of dissenting opinions during the process of party policy formation. At its core, IPD is about the internal distribution of power within a political party (Cross, Reference Cross2013) and it seems to require at least some element of participation by the ‘party on the ground’ in the selection of the leading members of the ‘party central office’ (Katz, Reference Katz2014, p. 188). Substantial participatory opportunities strengthen channels of communication from the grassroots and enable party activists, informed by the demands of their local communities, to directly influence and devise party policies (Teorell Reference Teorell1999;; Gauja, Reference Gauja2013; Wolkenstein, Reference Wolkenstein2016).

Although participatory mechanisms involve both assembly-based (deliberation) and plebiscitary (ballots and referendums) modalities, deliberative practices, in particular, are essential to the improvement of IPD. Intra-party deliberation may correct problems such as how increased membership inclusiveness or plebiscitary methods (membership ballots and referendums) have reinforced and consolidated the power of the party leadership (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair2009; Cross & Pilet Reference Cross and Pilet2015; Ignazi Reference Ignazi2018). Through deliberative interactions at local party meetings as well as at state and federal party conventions, members can share their opinions, critically evaluate the party line, and develop policy statements, informed by the concerns of their local communities, while the party leadership has limited role in influencing the formation of preferences and directing the choice of the membership.

In addition to discursive practices, pluralism of dissenting viewpoints ‘ensures that the issue under deliberation is considered from multiple angles’ (Hendriks et al. Reference Hendriks, Dryzek and Hunold2007, 366). Preferences of the AfD members are not largely aligned, and they frequently disagree on the shared principles of the party. Internal mechanisms, supporting forums of discussion and debate, help members voice their dissenting opinions, refine their preferences through discourse, and reach a compromise on final party programmatic decisions.

Such inclusive intra-party procedures, emphasizing deliberation and diversity of viewpoints, send an important signal to the members that their preferences are taken seriously in the process of policy formation and markedly diverge from the perception of parties as hierarchical bureaucratic leviathans with little membership empowerment.

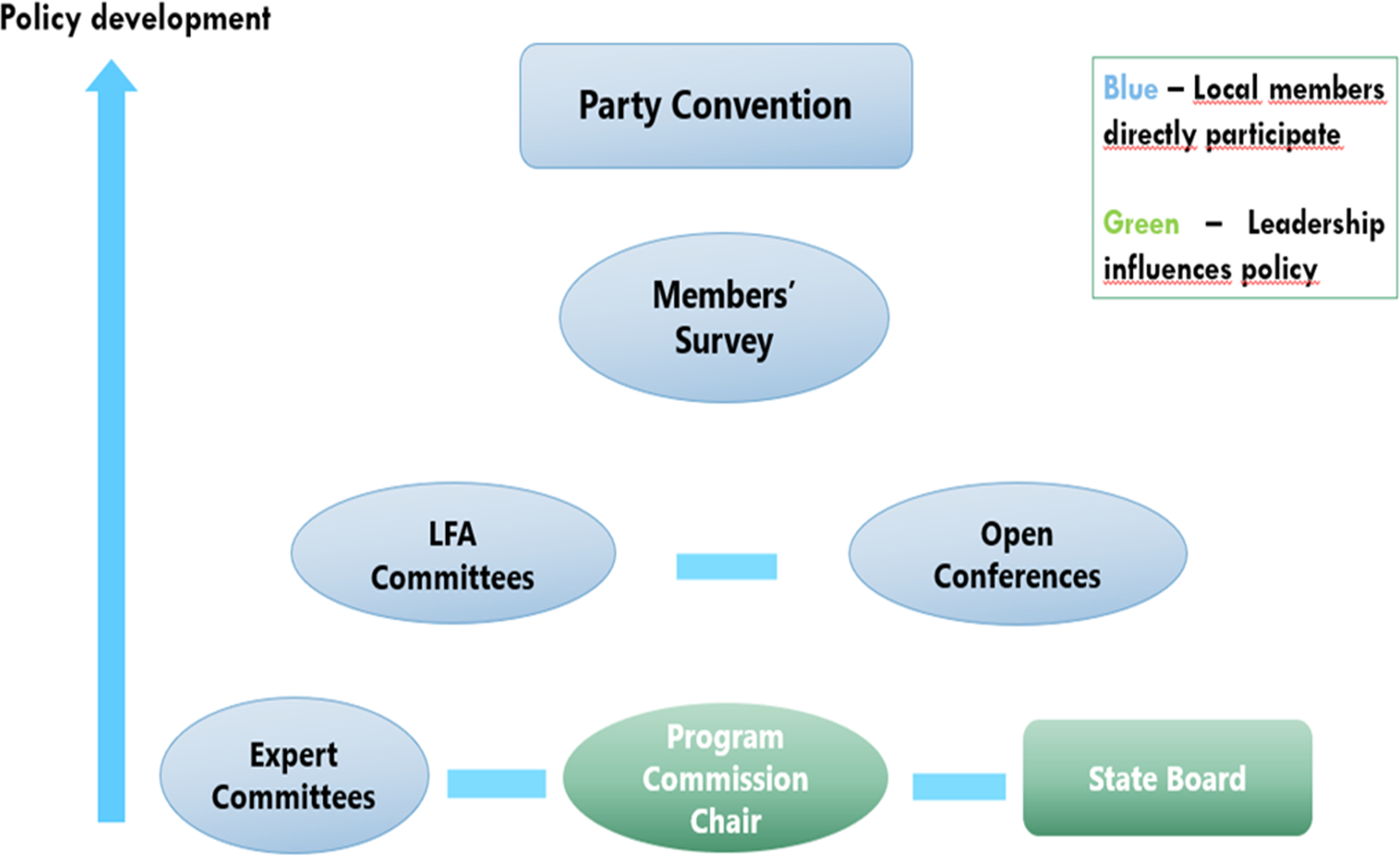

In the following analysis, (1) I examine the participatory opportunities available to members in the three main stages of party program development; and (2) I discuss deliberative practices and diversity of dissenting opinions in the case study of the 2018/2019 Federal Convention for European Parliament Elections. The AfD party employs a combination of direct participation of members and delegate participation depending on whether election programs are decided on the local, state, or federal levels. Policy formation consists of three main stages: (1) first, local policy groups, state expert committees (LFAs) or federal expert committees (BFAs) develop the programmatic statements, and a ‘Program Commission’, consisting of the chairs from each expert committee, assembles a policy draft document; (2) second, the expert committees organize membership surveys on the programmatic statements; and (3) finally, the draft is approved by a ‘Party Convention’. AfD members could influence policy development in all three stages: first, during the initial stages of the development process by drafting policy proposals in the local branches and by being members in expert committees (LFAs/BFAs); second, by participating in membership surveys; and third, by deliberating, amending, and voting on party policy at party conventions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Stages of policy formation at the AfD. Source: AfD party statutes.

Direct participation in expert committees at the state (LFAs) and federal (BFAs) levels

According to party statutes across all 16 federal states, expert committees develop programmatic statements and advise the state and federal party leadership on policy points. Every member can apply to participate in the respective LFA. Usually, there are 12 thematic committees in each state, consisting of 15–25 members each. In September 2019, I met with Olaf in the Berlin party office. He worked on the organization of expert committees for the 2017 North Rhine-Westphalia state election program and was also a member of the LFA on Social Issues. Olaf observed that around half of the party members from the state branch would attend regularly local policy meetings and at least 10% were constantly participating in the state expert committees (Olaf, North Rhine-Westphalia).

Participation in expert committees is on a volunteer basis, despite some variation in the selection process across state party branches. Generally, members send their applications directly to an LFA coordinator, appointed by the state party leadership. Most party activists who participated at least once in an expert committee since 2014 described the selection process as merit-based. For Hannah, the invitation to participate at the LFA on Education, Research and Culture hinged upon her knowledge of the education system and first-hand experience as an elementary school teacher in the Karlsruhe district (Hannah, Baden-Württemberg). Nevertheless, there were some disapproving voices about the recruitment process. William, a district party leader from Baden-Württemberg, argued that not expertise but rather personal interests motivated the selection procedures:

I have a military career as a reserve officer. I have international experience, which nobody has in this country here. I am refused to participate in the Expert Committee for Security and Foreign Affairs…They have no international experience and they talk about foreign policy. And now, they are afraid if someone is coming in with a little bit more knowledge, they might not be important anymore. This is a personal competition, so they try to close the doors. (William, Baden-Württemberg)

Bavaria, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and North Rhine-Westphalia, however, do not follow the general model of candidate self-nomination but rather involve the local members in the selection process. Local party branchesFootnote 2 organize elections where all members choose one representative from each district to be sent to the state party leadership for final approval. This way, party members provide a limited pool of democratically elected candidates for the leadership to choose from, thus reducing the likelihood of clientelist politics as suggested by the previous quote.

Party members see themselves as effective participants in an inclusive bottom-up policy development process, based on aggregated grassroots preferences. Stefen describes this process as ‘co-determination’:

That’s the DNA of our party too, that co-determination. Our program is not written by five people, but anyone who is interested can say, ‘Yes, I’m familiar with a topic very well. I’m a doctor, I’m a cop, I’m a lawyer. I bring along my experience, I go to state committees and develop positions’…That means there’s no program from above. Just the other way around, it grows, so to speak. (Stefen, Rhineland-Palatinate)

When asked whether party members could still take part in the LFA work even if they were not selected, Olaf responded that the expert committees are ‘not a closed shop’ and all members can bring in proposals and engage in the discussions without voting rights (Olaf, North Rhine-Westphalia). After the Program Commission has assembled a program draft, all party members would be invited to deliberation conferences (Landeskonferenz) at each LFA to discuss and give suggestions for changes. Such conferences are another opportunity for interested activists to contribute informally to policy development before a final draft of the election program is sent to a party convention.

Membership consultation through online voting

Membership surveys play a major role in the intermediate stages of policy formation, after the expert committees have prepared a draft program but before finalizing it at a party convention. Such intra-party surveys are not common in German parties. One of the few such instances was in 2015 when the Berlin party branch of the CDU held an intra-party referendum on the legalization of same-sex marriage – the first issue survey in the history of the CDU (Wuttke et al., Reference Wuttke, Jungherr and Schoen2017).

At the AfD party, membership surveys are frequently employed as tools for empowering the party base in the policy development process. Several interviewees who have participated in both state and federal expert committees emphasized that LFA/BFA participants often would not reach a majority agreement on a policy thesis. Thus, all the available alternatives to a thesis would be presented to the whole membership for a vote (Sylvia, Saxony-Anhalt). The Bavarian party branch also provides clear instructions for the content of membership surveys:

If at least a third of the members of the LFA jointly support an alternative programmatic position, this ‘qualified minority’ can demand that the position be prepared and presented as an alternative draft resolution on an equal basis. (LFA Rules of Procedure)

Although the statutes of all state branches mention membership surveys, only Bavaria and North Rhine-Westphalia regularly make use of them. Only larger state branches have the financial means to organize these kinds of polls frequently (Sylvia, Saxony-Anhalt). Nevertheless, membership surveys are always conducted for the Federal and European Election Programs. Although such polls are not formally binding, party members and delegates tend to cite the results when defending their proposals at party conventions. I observed such an instance, when attending the AfD European Elections Convention in January 2019. There was a heated discussion whether the electoral program should demand ‘reduction’ or ‘abolition’ of sanctions against Russia. While the Program Commission defended extensively the original draft formulation, one party delegate insisted on the ‘abolition’ alternative, invoking the importance of the grassroots democratic decision-making process (Figure 2). His proposal passed with great majority support.

We said when writing the program that we should let the members decide with the member survey, and the option of ending the sanctions received 94% support. (Delegate, European Elections Assembly)

Figure 2. Results from the 2018 Members’ Survey on the European Election Program. ‘A stable peace order in Europe is only possible with the involvement of Russia. We do not consider the sanctions imposed on Russia to be effective. The AfD is working to end sanctions and normalize relations with Russia.’ Yes (Ja) or No (Nein). Source: 2018 Members’ Survey on the European Election Program, AfD.

Most interviewees perceived the membership referendums as an enrichment to the deliberation culture of the party. There was a high expectation for the AfD to deliver on its promise for more inclusive decision-making practices. While such practices were perceived to be absent in the political culture of the mainstream parties, the AfD party was unique in its grassroots approach of relying on membership surveys (Dominic, Thuringia).

The final step: party conventions

Party conventions are the highest decision-making party institutions. The purpose of such conventions is ‘to establish a representative democratic link between the final policy adopted by the party and its grassroots membership’ (Gauja, Reference Gauja2013, p. 66). Several interviewees stressed the fact that final decisions are not made by the state or federal party leadership (Mathias, North Rhine-Westphalia; Mikaela, Bavaria). Rather the ‘democratic base’ holds all the power and party leaders must accept the outcome even if it displeases them:

Sometimes a position goes into the program, which does not suit a federal chairperson, at the time Frauke Petry. That happens, but if the members have decided with a majority, then you have to just accept it as a federal chairperson. Frauke Petry had to live with it, inevitably. She could not say, ‘This will be removed.’ Well, then people would have reprimanded her. (Sylvia, Saxony-Anhalt)

The party statutes outline two possible types of conventions: member assemblies (Mitgliederversammung) and delegate assemblies (Delegierteversammlung). Local party leaders from Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, and Rhineland-Palatinate try to organize members’ general assemblies to the highest possible level and avoid using delegates. Markus mentioned that although all members are invited to state conventions, 400–500 activists would attend on average. On 23 February, 2019, the State Convention in Heidenheim had the biggest turnout for the state branch with over 750 members, which was still manageable without introducing a delegate system (Markus, Baden-Württemberg).

While member assemblies are the general rule for party conventions, the federal party branch and three state branches – Hessen, North Rhine-Westphalia, and Saarland – have opted to organize delegate assemblies, citing large membership size and financial and venue constraints. Wilhelm was proudly reminiscing about the uniqueness of member inclusiveness at the early AfD federal conventions:

Before, we had members at the federal level as well. That was the largest party convention in the Federal Republic of Germany after WWII. It was our AfD party convention in July 2015, in Essen, where the showdown between Lucke and Petry happened. There were 3,500 members. (Wilhelm, Bavaria)

In a similar vein, Sylvia described the 2016 Federal Convention in Stuttgart, attended by more than 2,000 members, as ‘an insane organizational and logistical achievement’ and suggested that if members were to continue exercising their right to direct participation, the AfD would have to rent a stadium (Sylvia, Saxony-Anhalt).

Local branches elect delegates to attend the conventions on their behalf and delegate entitlement is adjusted according to membership size. Most of the party members I interviewed participated as members or delegates in at least one state or federal convention. As delegates agreed that they were exercising no agency, they were chosen to convey the interests of the local members, rather than to make individual policy decisions. Andre, a leader of a ‘youth wing’ party chapter in North Rhine-Westphalia, advocated for the involvement of more ‘youth wing’ members as delegates. He argued that local party branches in North Rhine-Westphalia set a good example of representing diverse interests by incorporating various rank-and-file members, rather than just sending the local chairperson and deputy chair to conventions (Andre, North Rhine-Westphalia).

Depending on the type of party convention, all members or delegates have the right to vote and to submit proposals for changing the program draft. Several interviewees specifically stressed the fact that the party leadership can propose motions as well but cannot vote unless they serve as delegates. The party seeks to facilitate a link between grassroots discussion and policy outcomes by circulating the convention agenda, the program draft, and a proposals’ book to all local branches several weeks in advance.

At the final stage of policy development, party conventions play a key role in ensuring the representation of diverse opinions within the AfD. Despite party efforts to incorporate widespread membership consultation in the process of program-writing, the initial stage of policy formation at LFAs and BFAs is not entirely representative of the interests of the general membership. Expert committees consist of party volunteers who are passionate about a certain topic and have the time and means to attend such meetings regularly. While most members tend to agree on core party topics about the European Union and immigration, when it comes to positions on ‘fringe issues’ such as the environment or family values, party conventions serve as the essential final step to creating a program that satisfies the majority of the membership. Andre described two such situations where the program draft produced by expert committees did not align with the beliefs of the general membership and the delegates made final changes at the party convention:

At the very beginning, Bernd Lucke’s sister was part of the LFA on Family Issues. She was more like a modern woman, pro-choice and sending the child to day-care and going to work. Then, you had the very conservative members who were really fired up, and they always clashed at the conventions.

The federal expert committee on the Environment brought in a moderate program. Probably moderate for our party and in the USA probably too. In Germany, where every party is more or less green, it was already right-wing. But then our crazy guys [referring to the delegates] came and threw it out and made it really hardcore. And it was a vote of 55% to 45%. (Andre, North Rhine-Westphalia)

Case study: deliberative dynamics at the federal convention for European Parliament elections Footnote 3

The analysis of IPD through members’ eyes has, thus far, showed perceived opportunities of meaningful involvement in programmatic decision-making processes. To put these evaluations into perspective, I examined the practices of internal deliberation during the 2018/2019 European Election Assembly. AfD members generally valued the party convention as a discussion forum, inducing fruitful and productive exchanges of diverse dissenting viewpoints, with the possibility to find common ground between the internal factions.

In November 2018 and January 2019, the party held a federal convention in the East German cities of Magdeburg and Riesa, selecting 30 candidates for the 2019 European Parliament Election and deliberating on the election program. Several left-wing demonstrations took place during the convention, but the police kept them within the city center, several kilometers away from the convention location. Each person had to go through airport-like security as well as membership identification and invitation checks. Private security guards, who were also party members, were situated at the entrances and each corner of the conference hall. Aside from these tight security measures, social interactions were relaxed and amicable. Party leaders, delegates, and guests would move around freely and converse openly with each other.

The majority of the 550 delegates were men. There was a considerable share of delegates who also belonged to the youth wing of the party – ‘Junge Alternative’ (JA). A few weeks before the convention, all delegates had the opportunity to submit proposals for changes in the election program draft. There were 73 proposals in an 81-page-long proposal book. Some of these motions were written jointly by members from different regional associations, suggesting a level of ‘horizontal integration’ (Duverger, Reference Duverger1954), with delegates from East German state associations being the most active in proposing changes.

While most of the motions dealt with minor suggestions, such as replacement of phrases or fixing the wordiness of a paragraph, heated discussions took place on one of the core Eurosceptic policies of the AfD – ‘DEXIT’ or Germany leaving the EU. The program section on DEXIT provided for a 2-hour-long deliberation between two opposing camps – the Program Commission, supported by hardline conservative delegates on one side and on the other side, the federal party chair and MEP Dr. Jörg Meuthen, backed by moderate party members. The original formulation demanded a DEXIT as a ‘ necessary’ response if reforms at the EU cannot be realized ‘ within one legislative period’ of 5 years. Dr. Meuthen, however, suggested more temperate phrasing so that a withdrawal from the EU should be deemed ‘worth considering’ instead of ‘necessary’ and should happen within ‘reasonable indefinite time’ (SN − 3, Antragsbuch Europawahlversammlung 2018).

A passionate Euro-critic and supporter for direct democracy, Werner Meier (Bavaria), was the spokesperson of the Program Commission on the DEXIT issue and deemed Dr. Meuthen’s suggestion too soft and not representing the will of the German people. Conservative delegates followed suit and called the proposal a product of utopian thinking, because the EU cannot be reformed:

The citizens who suffer from the EU expect clear deadlines from us. (Delegate #1 during deliberation)

The EU elite is not trustworthy, and we cannot expect to change anything with them, so we should push for our original claim. (Delegate #12 during deliberation)

On the other side, moderate delegates emphasized the importance of taking measured actions, instead of hastily dismissing reforms and jumping into another prolonged ‘Brexit’:

We must maintain our legitimacy. We cannot go into something important with a breakneck speed. We have to reform the EU and only when all means have failed, then we say it is reasonable to go. (Delegate #8 during deliberation)

Some members were not against an immediate DEXIT but believed it was unrealistic to achieve it, because the AfD had only 15%–20% support and could not successfully dominate the national debate. Martina Boeswald suggested the AfD use the opportunity to network with other Eurosceptic partners at the European Parliament and evaluate the European structures from within before convincing the public of their failure:

We should make a review report in 2021. We should prove to the public that the EU is just a tool for UN world politics, and then even the Euro-friendly citizens will wake up to the message. (Martina Boeswald, delegate from Baden-Württemberg)

At the end, the Program Commission offered a compromise between the two formulations that received a majority support from the delegates: ‘If our fundamental reform approaches in the existing EU system cannot be implemented in reasonable time , we consider Germany’s exit…to be necessary ’ (European Election Program 2019, p. 12).

In the guest section where I was observing the process, many AfD members disappointedly commented that the party should act now on a DEXIT, as ‘reasonable time’ would only delay necessary change. During lunch break, I also had a short conversation with Jakob, a delegate from Hamburg and a member of the ‘Youth Alternative’, who did not understand why so many party members were afraid of an immediate DEXIT. For him, DEXIT is also a reform and should not be postponed anymore because the German government has already given up too much sovereignty in the past 30 years (Jakob, Hamburg). While not content with the outcome, Jacob still expressed satisfaction with the AfD delivering adequate opportunities for members to engage in deliberation and influence policy decisions.

A month after the European Elections Assembly, I met with Dominic, a local party leader from East Thuringia and a close friend of Björn Höcke, leader of the radical right ‘Flügel’ faction. Dominic was actively involved in drafting the party program for the upcoming local elections. He also closely followed the online streaming of the Assembly and was profoundly dissatisfied with the outcome of the DEXIT debate. Nevertheless, he supported the majority decision because it was democratically made. While generally not sympathizing with the federal party leadership, including Dr. Meuthen, Dominic agreed that in the case of DEXIT party rhetoric should be moderate:

I do not want to dictate to the citizens that we need a DEXIT now…That is also one of our demands – grassroots democracy. The citizens should decide, and not me as a politician to say, ‘We need a DEXIT now.’ That is why, I understand the liberalization of the program in this respect, the point Mr. Meuthen was making. (Dominic, Thuringia)

Deliberation at party conventions is highly supported by the party members. All interviewees perceived it as a necessary component in a party whose core programmatic value is direct democracy and the empowerment of the local members. Time-consuming debates and quarrels are an integral part of the conventions, but that is a price many AfD members are willing to pay. Otherwise, they could join the CDU, where ‘if I do not shut my mouth, then I cannot go on; well, either you adapt, or your career is over.’ (Johan, Hessen). In the same vein, Sylvia jokingly pointed out that what is special about the AfD membership is that ‘we are very dissentious and even, as Gauland said so beautifully, we are “a fermenting bunch”.’ (Sylvia, Saxony-Anhalt).

Conclusive remarks

The AfD in its core ideology rejects the hierarchical nature of the established parties and their absence of responsiveness to demands made by rank and file and ordinary citizens. Thus, the party turns to grassroots democracy, emphasizing the power of party members rather than party leadership. Participant observation of party meetings and conversations with AfD members suggest that the party relies on significant participation and deliberation by members in the process of policy formation. Policy development in the AfD involves complex multi-stage procedures, which are open to the general membership and allow only limited involvement of the leadership in terms of consultation and logistical organization. While a smaller, less representative share of party activists is involved in preparation of the program drafts in expert committees (LFA/BFA), all members can participate in the final stages through online surveys and state party conventions. Prolonged deliberations at conventions, as the DEXIT debate has shown, indicate the presence of internal democracy and foster a sense of grassroots legitimation. Even though some members were dissatisfied with the outcomes of the policy debates, they still evaluated positively the party efforts to promote democratic deliberation and direct participation. Inclusive decision-making procedures develop a sense of empowerment among party activists, especially when a majority have expressed skepticism about their political influence in previous mainstream parties.

This article makes a twofold contribution to the existing literature. First, it expands our knowledge on party organization and directly speaks to scholarly work on the renewal of internal participation in green and left-libertarian European parties in the 1970s and 1980s (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1989; Pogutke, Reference Poguntke1987), radical left-wing parties in Latin America in the 1990s (Keck, Reference Keck1992), and more recently, movement parties after the European debt crisis (Della Porta et al. Reference Della Porta, Fernández, Kouki and Mosca2017; Caiani and Cisar Reference Caiani and Císař2018). The Alternative for Germany displays a high degree of members’ participation and deliberative practices – an important but contrasting addition to the comparative research on radical right parties which fail to sustain a democratic internal organization and consistently adopt mechanisms to centralize power in the leadership (DeClair, Reference DeClair1999;; Carter, Reference Carter2005; Heinisch and Mazzoleni, Reference Heinisch and Mazzoleni2016).

Second, this study has important implications for future research on populism, in terms of examining how populism may influence party organization and introduce new ways of strengthening political representation through referendums and deliberative democracy. Recent scholarship on the populist Five Star Movement and Podemos has explored the introduction of novel participatory methods for members and the possible negative impact of digital platforms on the functioning of IPD. Both the M5S and Podemos organize online deliberative forums, but their decision-making structures are still highly centralized, and members have limited access to space for horizontal discussions (Sandri et al. Reference Sandri, Seddone, Bulli, van Haute and Gauja2015; Deseriis and Vittori Reference Deseriis and Vittori2019; Gerbaudo Reference Gerbaudo2019). The study on the AfD party organization adds to this new research in terms of understanding how deliberative democratic processes work in practice and to what extent the federal party leadership dominates the decision-making processes. The findings from the field research suggest that populist parties may provide venues for internal deliberative practices to improve members’ satisfaction with political participation and to invigorate the connections between citizens and their party representatives (Teorell, Reference Teorell1999; Wolkenstein, Reference Wolkenstein2016).

Certainly, we should also consider the limits of IPD in populist organizations. The AfD party statutes, observed practices, and shared experiences by party members may suggest that the party is internally democratic and empowering the grassroots. However, we should pay special attention to the dynamic interactions between the party in public office and rank-and-file members. Caiani et al. (Reference Caiani, Padoan and Marino2021) have recently suggested that seemingly democratic internal processes in M5S and Podemos may enhance the influence of party elite in public office over key decisions in policy-making and candidate selection. Thus, the current study on the AfD has its limitations as it has not explored whether and how the party in public office may use the rhetoric and practices of grassroots democratic deliberation to gain autonomy in decision-making and possibly dominate the party on the ground.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773921000217.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Sofia Perez, Taylor Boas, Jeremy Menchik, and David Art for useful discussions and mentorship. The author also thanks Liah Greenfeld and Vivien Schmidt for thoughtful feedback in constructing the fieldwork methodology plan of this research project.

Interviewees, Cited in the Article

#1 – Andre, local leader, North Rhine-Westphalia, FDP.

#2 – Alfred, local leader, Brandenburg, CDU, FDP and Republikaner.

#3 – Dominic, local leader, Thuringia.

#4 – Gerhard, member, Saxony, CDU.

#5 – Hannah, member, Baden-Wuerttemberg.

#6 – Hans, member, Brandenburg, Free Voters.

#7 – Jacob, local leader, Hamburg.

#8 – Johan, local leader, Hessen, CDU.

#9 – Markus, local leader, Baden-Wuerttemberg, CDU.

#10 – Mathias, local leader, North Rhine-Westphalia, CDU.

#11 – Mikaela, member, Bavaria, former CSU.

#12 – Olaf, local leader, North Rhine-Westphalia, FDP and Freiheit.

#13 – Robert, member, Hessen, CDU.

#14 – Rudi, local leader, Berlin, CDU.

#15 – Stefen, local leader, Rhine Palatinate, Freiheit.

#16 – Sven, member, Saxony, FDP.

#17 – Sylvia, member, Saxony-Anhalt.

#18 – Thomas, member, Baden-Wuerttemberg, CDU.

#19 – Wilhelm, local leader, Bavaria, CSU.

#20 – William, local leader, Baden-Wurttemberg.

List of Party Documents Considered in the Analysis:

AfD. Results from the 2018 Members’ Survey for the European Elections Program. −https://www.afd.de/wp-content/uploads/sites/111/2018/11/Ergebnisse-der-Mitgliederbefragung-AfD-Europawahlprogramm−2018.pdf

AfD. Proposal Book for the European Elections Assembly. https://www.afd.de/wp-content/uploads/sites/111/2018/12/Antragsbuch_Riesa_2019_datensicher.pdf

AfD. 2019 European Elections Program. https://www.afd.de/wp-content/uploads/sites/111/2019/03/AfD_Europawahlprogramm_A5-hoch_web_150319.pdf

AfD Baden-Württemberg Party Statute. https://afd-bw.de/afd-bw/formulare/landessatzung_heidenheim.pdf

AfD Baden-Württemberg LFA Rules of Procedure. https://afd-bw.de/afd-bw/formulare/go_lfa.pdf

AfD Bavaria LFA Rules of Procedure. https://www.afdbayern.de/wp-content/uploads/sites/86/2015/11/GO-LFA-vom−13.11.2015.pdf

AfD Bavaria Party Statute. https://cdn.afd.tools/sites/170/2019/07/02211202/Landessatzung-BY-Stand−24.02.2019.pdf

AfD Berlin Party Statute and LFA Rules of Procedure. http://afd.berlin/partei/landessatzung/

AfD Brandenburg Party Statute. https://afd-brandenburg.de/landesverband/satzung-des-lv-brandenburg/

AfD Bremen Party Statute. https://afd-bremen.de/images/Uploads/Dokumente/landessatzung-bremen_26–02–17_endgueltige-fassung.pdf

AfD Hamburg Party Statute and LFA Rules of Procedure. https://afd-hamburg.de/satzung-und-ordnungen/

AfD Hessen Party Statute. https://cdn.afd.tools/sites/179/2019/04/23114846/1_AfD-Hessen_Satzung−2019–02–16_KM.pdf

AfD Lower Saxony Party Statute. https://afd-niedersachsen.de/landessatzung/

AfD Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Party Statute. https://cdn.afd.tools/sites/119/2016/11/08160931/MV-Satzung−2019.01.26.pdf

AfD Rheinland-Palatinate Party Statute. https://cdn.afd.tools/sites/110/2020/01/01182309/2019–11–17-Landessatzung-AfD-RLP.pdf

AfD Saarland Party Statute. https://cdn.afd.tools/sites/87/2019/02/04155119/Landessatzung−12.08.1803.02.19.pdf

AfD Saxony Party Statute. https://www.afdsachsen.de/landesverband/satzung.html

AfD Saxony-Anhalt Party Statute. https://cdn.afd.tools/sites/88/2018/08/14084541/Landessatzung-AfD-LV-Sachsen-Anhalt-Stand−09.06.2018.pdf

AfD Schleswig-Holstein Party Statute and LFA Rules of Procedure. https://afd-sh.de/index.php/component/phocadownload/category/2-satzung-ordnung

AfD Thuringia Party Statute. https://cdn.afd.tools/sites/178/2018/09/20163416/20180203_Landessatzung-Partei.pdf