The aim of the present scoping review is to map the existing meta-analytic and systematic review literature regarding adult attachment and mental health difficulties (MHDs). This review will include meta-analyses and systematic reviews as they are considered to offer good evidence, synthesizing a large body of data and assessing for quality of primary studies in this area. While the review does not offer a comprehensive map of all primary studies, it offers a broad enquiry into the state of research regarding adult attachment and MHD, identifying established, suggestive, or inconsistent findings and highlighting implications and future directions. In order to contextualize findings, a brief review of attachment theory and measurement across the lifespan will be presented.

Overview of attachment theory

Attachment theory developed from Bowlby’s (Reference Bowlby1982[1969]) observations of children who were separated from their caregivers. In attachment theory, he proposed that all humans are born with an innate psychobiological attachment system that motivates to seek proximity to, or availability of, a caregiver. The availability of the caregiver to meet the child’s needs for care and safety during times of danger contributes to their survival, in line with evolutionary theory.

When the child’s attachment behaviours are met appropriately they develop a stable and trusting attachment to their caregiver, and begin to use them as a ‘safe base’ from which to explore their world. Over time the child develops positive mental representations of themselves and of others based on these early experiences (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1982[1969]). However, when the caregiver is often or consistently unavailable to witness, tolerate, understand, and appropriately respond to the child’s attachment behaviours, the child does not experience relief from their distress, develops behaviour patterns to keep the caregiver as available as possible, developing an insecure attachment style, characterized by negative views of the self and/or others (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1982[1969]).

These internal working models and relationship styles are proposed to continue throughout the lifespan. Insecure attachment is theorized to reduce resilience when coping with threatening experiences, and to predispose an individual to psychological difficulties in times of crisis (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1982[1969]; Mikulincer & Shaver, Reference Mikulincer and Shaver2012).

Attachment measurement and classification in infants

Mary Ainsworth developed the Strange Situation (SS), an observational procedure to evaluate the early relations between infant and parent, based on the child’s reactions to their parent leaving and returning (Ainsworth et al. Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978). From this Ainsworth et al. (Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978) identified behaviours they suggested indicated a ‘Secure’ attachment, and anxious ‘Avoidant’ insecure attachment, and an anxious ‘Ambivalent/Resistant’ insecure attachment. See Table 1 for an outline of the infant behaviours of each style, and parenting style thought to contribute to the development of this style.

Table 1 Initial attachment styles of the Strange Situation (Ainsworth et al. Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978)

However, not all behaviour fit these three attachment categories. Of particular note, were behaviours such as freezing, rocking, and both approaching and avoiding the caregiver. This led to a fourth classification of ‘Disorganized/Disorientated’ proposed by Mary Main, a graduate student of Ainsworth (Main & Solomon, Reference Main and Solomon1990). These behaviours are often related to maltreatment and trauma. This observation also led to the development of Crittenden’s (Reference Crittenden1997) Dynamic Maturational Model (DMM), discussed later. Evidence has supported the theoretical position that differences in attachment style are related to the caregiving style and environment (van IJzendoorn, Reference van IJzendoorn1995).

In later childhood insecure attachment is associated with MHD. Moderate associations have been identified between insecure attachment and externalizing behaviours (Fearon et al. Reference Fearon, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, Lapsley and Roisman2010), and anxiety (Colonnesi et al. 2011).

Attachment measurement and classification in adults

There is evidence that attachment styles are relatively stable from infancy to young adulthood (Pinquart et al. Reference Pinquart, Feussner and Ahnert2013). The measurement of attachment in adults has developed in two traditions. The first was as an extension of the SS, the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI; George et al. Reference George, Kaplan and Main1985). The AAI is an hour long interview, during which participants are asked about their childhood experiences with their primary caregivers, and about memories of loss, separation, rejection, and trauma (George et al. Reference George, Kaplan and Main1985). Coders then rate the participants’ discourse according to the way in which they respond, reflecting their state of mind and coherence of discourse.

Discourse classified as Secure-Autonomous (F) shows flexibility and coherence in evaluating childhood experiences of either adverse or supportive nature. Those classified with Dismissing (Ds) insecure attachment styles tend to idolize, derogate, and/or normalize experiences with caregivers and have difficulty remembering early experiences (Main & Goldwyn, Reference Main and Goldwyn1998). Those with Preoccupied (E) attachment styles tend to become overwhelmed by recalling often vivid childhood experiences that are described with anger/or passivity. Transcripts are also coded for unresolved trauma and loss when discourse becomes disorganized. If individuals score at or above the midpoint of an unresolved scale, their attachment category is Unresolved (U). When both Ds and E styles are observed during the interview, discourse is classified as Cannot Classify (Hesse, Reference Hesse1996). Classification based on the AAI has been found to predict interviewee’s attachment styles with their children, as measured by the SS, suggesting construct validity (Cohn et al. Reference Cohn, Silver, Cowan, Cowan and Pearson1992; van IJzendoorn, Reference van IJzendoorn1995). Additionally, Sagi et al. (1994) found that the classifications on the AAI were not found to be associated with non-attachment-related memory and intelligence abilities, also suggesting construct validity.

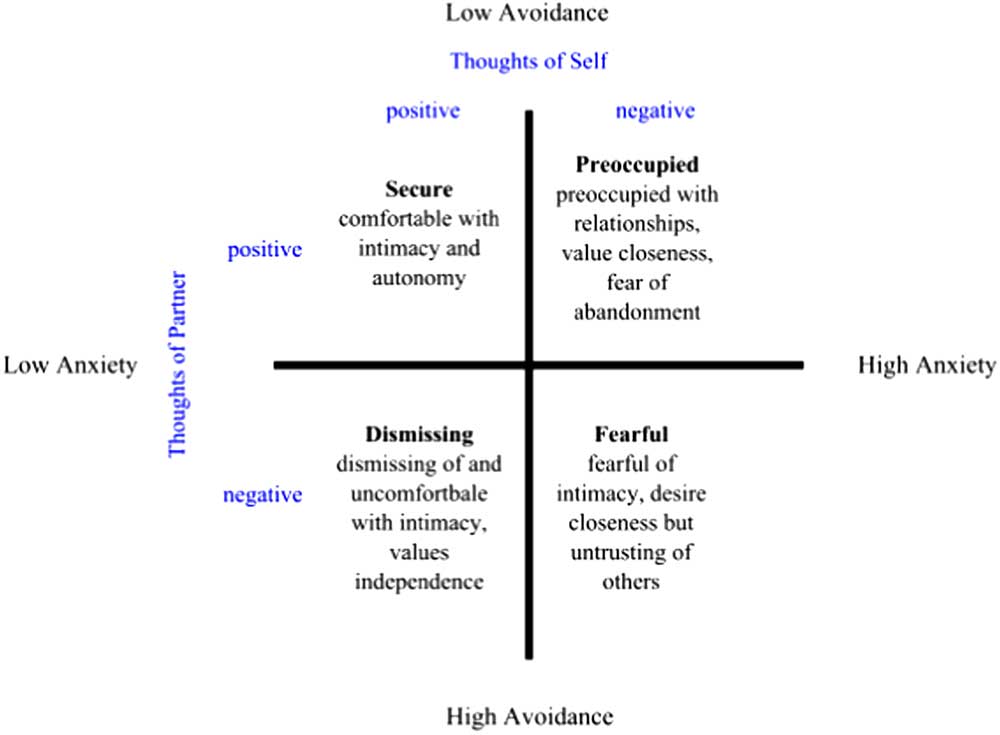

The self-report tradition was developed soon after the AAI, and assesses current relationship styles thought to be influenced by internal working models, developed from the individual’s attachment history (Hazan & Shaver, Reference Hazan and Shaver1987). These are considered to measure two independent dimensions, attachment-related anxiety and avoidance (Hazan & Shaver, Reference Hazan and Shaver1987). Attachment anxiety suggests the levels of worry that a partner will not be responsive in times of need. Avoidance indicates the level of distrust, and tendency towards independence, self-reliance and emotional distance (Hazan & Shaver, Reference Hazan and Shaver1987). Given positioning on each dimension, the individual can be classified as either Secure, or one of three insecure styles, Preoccupied, Dismissive, and Fearful. These classifications correspond with the individual’s working models of the self and other (Bartholomew & Horowitz, Reference Bartholomew and Horowitz1991). See Fig. 1 for representation of these attachment styles.

Fig. 1 Adult attachment styles according to the two dimensions, avoidance and anxiety, and the corresponding internal working models of self and others (Bartholomew & Horowitz, Reference Bartholomew and Horowitz1991).

The self-report and interview measures are considered to measure relatively separate aspects of attachment, that is current relationship styles and state of mind with respect to early attachment experiences, respectively. However, they do share some measureable overlap. Associations have been identified between the measures in the areas of comfort depending on attachment figures and comfort acting as an attachment figure for others (Shaver et al. Reference Shaver, Belsky and Brennan2000).

Furthermore, research has demonstrated that insecure attachment is often passed down from parent to child, termed the inter-generational transmission of attachment. Parental sensitivity was originally theorized to be the main mechanism for this. However, there has been insufficient evidence to support this model (van IJzendoorn, Reference van IJzendoorn1995). An ecological model that considered wider factors related to later attachment experiences, the social context, and individual differences has since been proposed (van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1997). Considering attachment as a triadic rather than dyadic process (among two caregivers and a child, where appropriate), the role of the extended family or social network, the wider macro system, and biological correlates have been suggested as areas for future research regarding the transmission gap (Sette et al. Reference Sette, Coppola and Cassibba2015).

Further developments of attachment theory: the DMM

Crittenden (Reference Crittenden1997) developed the DDM that expands on original attachment theory, growing from her observations of infants in the SS who did not fit the original three categories. While Main described their behaviour as Disorganized, Crittenden (Reference Crittenden1997) proposed that all attachment behaviours are functional self-protective strategies developed through interaction with caregivers. The DMM expands on Bowlby’s (Reference Bowlby1982[1969]) theory that infants may adaptively exclude information in certain environments, and may continue with this style of information processing later in life, which may then become maladaptive given the change in context. Crittenden (Reference Crittenden1997) suggests that infants classified as Avoidant in the SS, likely cut off affective information, while those classified as Ambivalent cut off cognitive information. Based on these patterns of behaviours the DDM identifies further insecure attachment style subtypes that develop as the infant matures into adulthood. These are considered dimensional rather than categorical concepts, with a balanced style in the middle (Crittenden, Reference Crittenden1997). There has been little empirical testing of the later developments of the model that apply to adolescents and adults (Landa & Duschinsky, Reference Landa and Duschinsky2013).

Review aim

Attachment theory has contributed to a vast amount of research and has emphasized the importance of social connection in human development across the lifespan. In line with the original theory, a large body of research has explored attachment and its connection to mental health. In order to offer a broad enquiry into the state of this research, the present scoping review will identify and discuss relevant systematic reviews, highlight strengths and weaknesses in the evidence base, and offer suggestions regarding research, theory, and practical applications.

Method

This review followed guidelines by Levac et al. (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien2010). This involved five stages including, (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting results. Through content analysis, themes were identified and findings are discussed regarding each theme.

Search strategy

The study took place between September and December 2015. A systematic search of PsycInfo and Pubmed databases was carried out on 28 November 2015 to identify systematic reviews and meta-analyses regarding attachment and MHDs in an adult population. The search terms were ‘Attachment’ and ‘Systematic Review or Meta-Analysis’. The search was not limited by any mental health keywords in order to avoid missing relevant studies. In total, 348 articles were identified. Titles and abstracts were screened. In all, 24 full text articles were assessed and of these, 20 were identified for the review.

Study selection

Studies were selected if they were an English language published systematic review or meta-analysis that reviewed studies using an established measure of adult attachment in the contexts of MHDs and related processes.

Quality check framework

There are mixed views regarding the need to appraise study quality in scoping reviews (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005; Levac et al. Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien2010). By their nature systematic reviews and meta-analyses generally select high-quality studies to synthesize. However, to ensure a basic level of quality appraisal in this review, Dixon-Woods et al.’s (2006) ‘fatal flaws’ criteria were applied. This criteria asks: Are the aims and objectives of the research clearly stated? Is the research design clearly specified and appropriate for the aims and objectives of the research? Do the researchers display enough data to support their interpretations and conclusions? Do the researchers provide a clear account of the process by which their findings were produced? Is the method of analysis appropriate and adequately explicated? Three studies mentioned attachment in their reviews, but did not review attachment research, and so were excluded. All appropriate studies met the basic quality check appraisal. In total, 17 studies were included in the review.

Data extraction

A form was developed to extract study characteristics including, authors, publication year, study design, participant characteristics, review aim, inclusion criteria, measure of attachment, aspect of mental health considered, key findings, limitations, and implications.

Data summary and synthesis

The above information was then presented in Tables 2 and 3, with an accompanying narrative in the results section, grouped into relevant themes through content analysis.

Table 2 Characteristics of 17 included studies

AAI, Adult Attachment Interview; AAI2, Adult Attachment Inventory; AAPR, Adult Attachment Prototype Rating; AAQ, Adult Attachment Questionnaire; AAS, Adult Attachment Scale; AHQ, Attachment History Questionnaire; AQ, Attachment Questionnaire; ASQ, Attachment Styles Questionnaire; BARS, Bartholomew Attachment Rating Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BED, Binge eating disorder; BFPE, Bielefeld Partnership Expectations Questionnaire; BPD, borderline personality disorder; BM, burnout measure; CATS, Client Attachment to Therapist Scale; CC, Cannot Classify; CES-D, Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; Clin, clinical; Com, community; DACI, Depression Adjective Checklist, Forms F and G; DAPP, Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology; DASS, Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales; DASsatis, Dyadic Adjustment Scale; Ds, Dismissing; E, Preoccupied; ECRS, Experiences in Close Relationships Scale; ED, eating disorder; EDEbinge, Eating disorder examination-assessment of days binged; EDNOS, eating disorder not otherwise specified; F, Secure; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; HAM-D, 6 item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HAMA, Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; HC, healthy control; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; HSCL, Hopkins Symptoms Checklist; HSCL-90, Hopkins Symptom Checklist-90; IDAS, Inventory of Depression and Anxiety symptoms; IIP, Inventory of Interpersonal Problems; IPANAT, the Implicit Positive and Negative Affect Test; IPPA, Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment; IPV, Intimate Partner Violence; M-A, meta-analysis; MBI, Maslach Burnout Inventory; MDD, major depressive disorder; MPSS-SR, Modified PTSD Symptom Scale-Self-Report; NIMH, National Institute of Mental Health; NOS, not otherwise specified; PAM, Psychosis Attachment Measure; PBI, Parental Bonding Inventory; PD, personality disorder; ProQOL:CSE-R-III, Professional Quality of Life: Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue Subscales-Revisions; PS, primary studies; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; RAQ, Reciprocal Attachment Questionnaire; RCT, randomized control trial; RDoC, Research Domain Criteria project; RF, reflective functioning; RQ, relationship questionnaire; RSQ, Relationship Scales Questionnaire; S-M BM, Shiron–Melamed Burnout Measure; SAQ, Service Attachment Questionnaire; SAS1, Social Attachment Scale; SAS2, Social Anhedonia Scale; SASI, Separation Anxiety Symptom Inventory; SCL-90-R, Symptom Checklist-90-Revised; SES, Socio-economic status; SR, systematic review; TM, trichotomous measure; TSC-40, Trauma Symptom Checklist-40; U, Unresolved; WAI, Working Alliance Inventory.

Table 3 Overview of key findings, limitation and implications/future directions

AAI, Adult Attachment Interview; AN, anorexia nervosa; AN-R, anorexia nervosa-restricting type; BED, Binge eating disorder; BN, bulimia nervosa; BPD, borderline personality disorder; CATS, Clients’ Attachment to Therapist Scale; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; CI, confidence interval; CC, Cannot Classify; Ds, Dismissing; DMM, dynamic maturational model; E, Preoccupied; ED, eating disorder; ES, effect size; F, Secure; MHD, mental health difficulty; OPD, operationalized psychodynamic diagnostics; RCT, randomized control trial; RF, reflective functioning; SES, Socio-economic status; SR, systematic review; STIPO, Structured Interview of Personality Organization; TOM, Theory of Mind.

Results

The findings are presented in two tables that outline study characteristics (Table 2) and an overview of key findings, limitations, and implications (Table 3). A brief narrative regarding study characteristics accompanies Table 2

Study characteristics

The level of information offered regarding sample description was varied. Age was reported for seven studies. Two studies contained a small number of adolescents (Bakermans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn2009; Gumley et al. Reference Gumley, Taylor, Schwannauer and MacBeth2013). Of those reporting age, the majority of participants were younger adults. Seven studies of 17 reported gender, of which all were mostly female (67–73.5%). One study on psychosis consisted mostly of males (71.9%; Gumley et al. Reference Gumley, Taylor, Schwannauer and MacBeth2013). Four reported country, with most participants from North America. Number of primary studies ranged from 3 to 200. All studies reported clear aims and inclusion criteria.

Key findings, limitations, and implications

The accompanying narrative for Table 3 presents these findings in light of the four themes, (1) measurement of attachment; (2) measurement of MHD; (3) intrapersonal processes related to attachment and MHDs; and (4) interpersonal processes related to attachment and MHDs. These themes were developed through content analysis of the data extracted from included reviews.

Theme one: measurement of attachment

The first theme was regarding the ways in which attachment was measured in the included reviews. Six studies reported findings on both self-report and interview measures (Levy et al. Reference Levy, Ellison, Scott and Bernecker2011; Caglar-NNazali et al. Reference Caglar-NNazali, Corfield, Cardi, Ambwani, Leppanen, Olabintan, Deriziotis, Hadjimichalis, Scognamiglio, Eshkevari and Treasure2014; Gumley et al. Reference Gumley, Taylor, Schwannauer and MacBeth2013; Korver-Neiberg et al. Reference Korver-Neiberg, Berry, Meijer and de Hann2014; Malik et al. Reference Malik, Wells and Wittkowski2015; Tasca & Balfour, Reference Tasca and Balfour2014). Four reporte findings using only interview measures (Van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, Reference van IJzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburg1996; Bakermans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn2009; Zachrisson & Skarderud, Reference Zachrisson and Skarderud2010; Katznelson, Reference Katznelson2014). Seven reported findings using only self-report measures (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Msetfi and Golding2010; Diener & Monroe, Reference Diener and Monroe2011; Selcuk et al. Reference Selcuk, Zayas, Gunaydin, Hazan and Kross2012; Bernecker et al. Reference Bernecker, Levy and Ellison2014; Mallinckrodt & Jeong, Reference Mallinckrodt and Jeong2014; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Rietzschel, Danquah and Berry2015; West, Reference West2015). Of the studies that reported on both interview and self-report measures, two were meta-analyses that combined results (Levy et al. Reference Levy, Ellison, Scott and Bernecker2011; Korver-Neiberg et al. Reference Korver-Neiberg, Berry, Meijer and de Hann2014), one narrative review that presented findings together (Malik et al. Reference Malik, Wells and Wittkowski2015), four narrative reviews that presented findings separately (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Msetfi and Golding2010; Gumley et al. Reference Gumley, Taylor, Schwannauer and MacBeth2014; Tasca & Balfour, Reference Tasca and Balfour2014; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Rietzschel, Danquah and Berry2015), and one that presented meta-analytic results for self-report measures and a narrative review for interview measures (Caglar-NNazali et al. Reference Caglar-NNazali, Corfield, Cardi, Ambwani, Leppanen, Olabintan, Deriziotis, Hadjimichalis, Scognamiglio, Eshkevari and Treasure2014). A wide variety of self-report measures were used. The AAI was the most commonly used interview measure.

Theme two: measurement of MHD

The second theme was regarding the types of MHDs that were addressed in the included studies. In total, 14 studies included clinical samples, one included health professionals who experienced burnout (West, Reference West2015), and two used non-clinical samples, but measured a psychological process relevant to MHD – affect regulation (Selcuk et al. Reference Selcuk, Zayas, Gunaydin, Hazan and Kross2012; Malik et al. Reference Malik, Wells and Wittkowski2015). Of the 14 that included clinical samples, there were a mix of MHD including mood, anxiety, personality, suicidality, antisocial and other externalizing behaviours, personality disorders, abuse, post-traumatic stress disorder, eating disorders (ED), drug use, psychosis, and non-severe difficulties presenting at university counselling centres. One small sample included people with somatform difficulties (Bakermans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn2009). In one review autism and attachment were considered in relation to reflective functioning (RF; Katznelson, Reference Katznelson2014). Insecure attachment style was consistently associated with MHD. However, studies failed to show a consistent relationship between attachment style and mental health diagnosis. Unresolved classifications were particularly high among clinical samples.

Three systematic reviews concerned attachment and ED specifically. One also included meta-analytic synthesis. Insecure attachment styles were found to be more common among those with EDs when using both interview measures (Zachrisson & Skarderud, Reference Zachrisson and Skarderud2010; Caglar-NNazali et al. Reference Caglar-NNazali, Corfield, Cardi, Ambwani, Leppanen, Olabintan, Deriziotis, Hadjimichalis, Scognamiglio, Eshkevari and Treasure2014; Tasca & Balfour, Reference Tasca and Balfour2014) and self-report measures (Caglar-NNazali et al. Reference Caglar-NNazali, Corfield, Cardi, Ambwani, Leppanen, Olabintan, Deriziotis, Hadjimichalis, Scognamiglio, Eshkevari and Treasure2014) compared to health controls. Tasca & Balfour (Reference Tasca and Balfour2014) report a rate of insecure attachment ranging from 70% to 100% across three primary studies. Zachrisson & Skarderud (Reference Zachrisson and Skarderud2010) suggest there is some evidence that Preoccupied styles are more common among bulimia nervosa. Dismissing styles among anorexia nervosa. Tasca & Balfour (Reference Tasca and Balfour2014) report inconsistent findings between ED diagnosis and attachment style but suggest that attachment style may be relevant to symptomology and severity. They suggest this supports the relevance of attachment styles when considering ED transdiagnostically. High levels of disorganized mental states were also identified among ED participants (Caglar-NNazali et al. Reference Caglar-NNazali, Corfield, Cardi, Ambwani, Leppanen, Olabintan, Deriziotis, Hadjimichalis, Scognamiglio, Eshkevari and Treasure2014; Tasca & Balfour, Reference Tasca and Balfour2014).

Two reviews focussed on attachment in the context of psychosis among those with clinical diagnoses and those from the community experiencing (sub)clinical psychosis experiences (Gumley et al. Reference Gumley, Taylor, Schwannauer and MacBeth2013; Korver-Neiberg et al. Reference Korver-Neiberg, Berry, Meijer and de Hann2014). Insecure attachment was associated with increased symptoms while greater security is associated with fewer symptoms. West (Reference West2015) found that attachment anxiety is associated with burnout and that attachment security has a negative relationship with burnout, while there are mixed findings regarding avoidance.

Theme three: intrapersonal processes related to attachment and MHDs

The third theme was regarding the intrapersonal processes that were addressed in the included studies. A number of studies focussed on intrapersonal processes that were considered potential mediators between attachment style and MHD. Selcuk et al. (Reference Selcuk, Zayas, Gunaydin, Hazan and Kross2012) and Malik et al. (Reference Malik, Wells and Wittkowski2015) focussed on emotion regulation and Katznelson (Reference Katznelson2014), on RF, both of which are considered to be relevant psychological processes in mental health. Selcuk et al. (Reference Selcuk, Zayas, Gunaydin, Hazan and Kross2012) found that emotion regulation after recalling an upsetting memory, is facilitated by imagining a secure attachment figure. However, this effect was not identified for those with insecure attachment styles imagining their attachment figure. Katznelson (Reference Katznelson2014) conducted a systematic review of RF, the operationalization of mental processes thought to contribute to the ability to mentalize, that is understand one’s own and others’ behaviours as a result of feelings, thoughts, beliefs, and desires (Fonagy et al. Reference Fonagy, Target, Steele and Steele1998). It is considered a developmental skill acquired by children though attachment relationships, which later impacts on an adults’ ability to care giver. In this way it may be an important factor in the inter-generational transmission of attachment (Katznelson, Reference Katznelson2014). Katznelson (Reference Katznelson2014) suggests that the early findings suggest RF is often low for those with MHD, particularly borderline personality disorder, some ED, and among more severe MHD. Low RF was also observed in the ED and psychosis reviews, with suggestion that mentalizing may function as a mediator between insecure attachment and ED or psychosis.

Two studies discussed intrapersonal processes as mediators between attachment styles and ED. Tasca & Balfour (Reference Tasca and Balfour2014) note that two studies found that maladaptive perfectionism, hyperactivation of emotions, negative affect, and alexithymia all mediated the relationship between insecure attachment and specific ED symptoms. Similarly, Caglar-NNazali et al. (Reference Caglar-NNazali, Corfield, Cardi, Ambwani, Leppanen, Olabintan, Deriziotis, Hadjimichalis, Scognamiglio, Eshkevari and Treasure2014) identified difficulties with identifying, understanding, and verbalizing emotions among those with ED.

Theme four: interpersonal processes related to attachment and MHDs

The fourth theme was regarding the interpersonal processes that were addressed in the included studies. Many studies addressed interpersonal aspects of attachment in relation to MHD in the areas of social cognition (Caglar-NNazali et al. Reference Caglar-NNazali, Corfield, Cardi, Ambwani, Leppanen, Olabintan, Deriziotis, Hadjimichalis, Scognamiglio, Eshkevari and Treasure2014), interpersonal functioning, engagement with services (Gumley et al. Reference Gumley, Taylor, Schwannauer and MacBeth2013; Korver-Neiberg et al. Reference Korver-Neiberg, Berry, Meijer and de Hann2014), and n relation to the therapeutic alliance (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Msetfi and Golding2010; Diener & Monroe, Reference Diener and Monroe2011; Bernecker et al. Reference Bernecker, Levy and Ellison2014; Mallinckrodt & Jeong, Reference Mallinckrodt and Jeong2014).

Not surprisingly, difficulties in social relationships were identified among those with insecure attachment styles and MHD, specifically among the ED and psychosis reviews. These interpersonal difficulties were suggested to impact engagement with therapeutic services, not only contributing to the maintenance of MHD, but potentially impeding recovery. Among the psychosis reviews, insecure attachment was moderately associated with poorer engagement with services and poorer interpersonal functioning (Gumley et al. Reference Gumley, Taylor, Schwannauer and MacBeth2013; Korver-Neiberg et al. Reference Korver-Neiberg, Berry, Meijer and de Hann2014). Among the ED reviews, those with ED showed difficulties with non-verbal communication, difficulties in understanding how others think and feel, and an increased sense of social inferiority (Caglar-NNazali et al. Reference Caglar-NNazali, Corfield, Cardi, Ambwani, Leppanen, Olabintan, Deriziotis, Hadjimichalis, Scognamiglio, Eshkevari and Treasure2014).

Within therapy, secure attachment appears to make it easier for clients to create a strong working alliance (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Msetfi and Golding2010; Mallinckrodt & Jeong, Reference Mallinckrodt and Jeong2014). Conversely, insecurity is associated with weaker therapeutic alliance (Diener & Monroe, Reference Diener and Monroe2011). Levy et al. (Reference Levy, Ellison, Scott and Bernecker2011) report poorer post-therapy outcomes for those with anxious attachment, and better outcomes for those with secure attachment styles. However, they did not control for baseline symptoms and thus this may reflect the association between anxious attachment and MHD, rather than indicating that therapy is less effective for those with anxious attachment. In fact, Taylor et al.’s (Reference Taylor, Rietzschel, Danquah and Berry2015) review offers a more hopeful picture, finding evidence to suggest that attachment security increases and attachment anxiety decreases following therapy, with a number of studies reporting participants moving from insecure to secure classifications. They report mixed findings regarding change in attachment avoidance after therapy (Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Rietzschel, Danquah and Berry2015). Tasca & Balfour (Reference Tasca and Balfour2014) found that among those with ED, avoidant attachment was associated with drop out from individual and group therapy, and difficulties with group progress and cohesion.

Discussion

The present findings demonstrate the importance of understanding attachment insecurity in the context of MHD and psychotherapy. There are consistent findings of high levels of insecure attachment among clinical populations, including Dismissing and Preoccupied styles. The Unresolved classification, related to trauma, appears to be the most prevalent among clinical samples. There has been particular attention to those with ED and psychosis who show high levels of insecure attachment and associated difficulties with emotion, mentalization, and social relationships. There is good evidence to suggest that an insecure attachment style may act as an obstacle to developing a strong therapeutic alliance, however, attachment security is seen to increase while attachment anxiety is seen to decrease after therapeutic interventions.

Implications for research, theory, and practice

Though there is some overlap between the self-report and interview approaches, they are considered to measure relatively different aspects of attachment (Shaver et al. Reference Shaver, Belsky and Brennan2000). Thus, future reviews may benefit from presenting self-report and interview findings separately. Reviews that compare areas of convergence and divergence on these two forms of measurement may also offer further insight into their conceptual differences. Given the high level of insecure attachment styles among clinical samples it may be useful to utilize a more sensitive dimensional measure of attachment in research. Roisman et al. (Reference Roisman, Fraley and Belsky2007) suggest that the distribution of attachment as measured by the AAI is in fact continuous rather than categorical. Crittenden’s (Reference Crittenden1997) DMM is an example of a dimensional model that may be more sensitive to subtle but meaningful differences within insecure styles, related to mental health.

Studies consistently identified that insecure styles were common among clinical samples. However, studies that attempted to connect attachment style with mental health diagnosis were unable to produce consistent results. This finding may be related to the way in which MHD are conceptualized in research and practice. The prevailing classification system, which outlines diagnoses based on the presence of clinical symptoms, has evoked concern regarding its poor reliability, validity, and prognostic value [British Psychological Society (BPS), 2011]. There has been invitation to develop an alternative system for describing, understanding, and researching mental health (BPS, 2011).

One such alternative system is the Research Domain Criteria project (RDoC), developed for research by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The RDoC proposes that biological, social, and psychological processes be measured in a ‘bottom up’ manner in order to better understand the full range of human behaviour, from mental health to illheath (Sanislow et al. Reference Sanislow, Pine, Quinn, Kozak, Garvey, Heinssen, Wang and Cuthbert2010). Within this framework, ‘Affiliation and Attachment’ is identified as a category for research, within the ‘Systems for Social Processes’ domain (NIMH, 2015). One study adopted this framework to review previous research related to ED (Caglar-NNazali et al. Reference Caglar-NNazali, Corfield, Cardi, Ambwani, Leppanen, Olabintan, Deriziotis, Hadjimichalis, Scognamiglio, Eshkevari and Treasure2014). Future research that adopts this framework will be able to study attachment and MHD without relying on existing psychiatric diagnoses and thus may offer clearer insights into the role of attachment in mental health. Furthermore, the inclusion of biological processes offers to enhance current understanding of attachment considerably.

While working within the current psychiatric classification system, attachment and somatic symptom disorder and autism spectrum disorders are areas for future research given the lack of data for these diagnoses within the reviewed studies. In particular, attachment research regarding somatoform difficulties may be relevant as people with somatic difficulties may present to hospitals, that is a caregiving system, during a time of high stress – a context in which the attachment system may be particular active. Another clinical area with no identified meta-analytic or systematic review is chronic pain, which is similarly relevant to attachment theory.

Further research regarding attachment and therapeutic processes and outcomes over multiple time points throughout therapy and at follow-up will further elucidate the role of attachment in recovery from MHD. Emerging evidence suggests that those with avoidant attachment may struggle to develop a strong working alliance with their therapist, or may struggle with certain therapy formats, such as group therapy (Marmarosh & Tasca, Reference Marmarosh and Tasca2013). Continued research into the impact the health care provider’s attachment style may have on the therapeutic relationship, or on service engagement, in participants with insecure attachment styles and MHD is also relevant. Similarly, awareness of the connection between health care provider’s attachment styles and vulnerability to burnout or compassion fatigue may contribute to development of health care services, management, and supervision processes.

In all, the current evidence regarding attachment theory in adults in relation to MHD continues to support Bowlby’s (Reference Bowlby1982[1969]) original suggestion. During times of stress a secure attachment style may support the individual to cope, and those with insecure attachments are more vulnerable to difficulties related to intra- and interpersonal functioning.

Limitations

A major limitation of this review is the lack of inclusion of primary studies, thus likely missing important areas of research regarding adult attachment and MHD. However, it does highlight the areas where further primary studies and subsequent systematic review or meta-analyses may be appropriate to advance the evidence base regarding attachment theory. Additionally, the review was carried out by an individual, rather than by review team, as suggested by Levac et al. (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien2010).

Conclusion

The current review outlines research that demonstrates the relevance of attachment theory to understanding, researching, and working with MHD. It has been consistently found that insecure attachment is associated with MHD, particularly Unresolved styles, thought to be related to traumatic experiences. This also highlights the connection between interpersonal trauma and MHD, and the associated difficulties with intra- and interpersonal functioning in later life. However, the current evidence base also highlights the healing potential of relationships, with people engaging in therapy, developing more secure attachment styles, and experiencing positive outcomes. Further research is needed to clarify and further identify the specific intra- and interpersonal functions that mediate insecure attachment style and MHD. However, the current evidence suggests the importance of our early relationships in helping us develop the skills to understand and care for ourselves and others, and the relevance of these skills in mental health.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.