Figure 1 On International Workers’ Day, 1 May 2012, a man walking his dog discovered Ihsane Jarfi’s body in a field. La Reprise: Histoire(s) du théâtre (I), Milo Rau and Ensemble. Théâtre National, Brussels, May 2018. (Photo by Hubert Amiel)

Reprise et ressouvenir sont un même mouvement, mais en direction opposée; car, ce dont on a ressouvenir, a été: c’est une reprise en arrière; alors que la reprise proprement dite est un ressouvenir en avant.

— Søren Kierkegaard (La Reprise, 1843)(Repetition and recollection are the same movement, except in opposite directions; for what is recollected has been, is repeated backward. Whereas the real repetition is recollected forward.)

Production Notes

La Reprise: Histoire(s) du théâtre (I) premiered in Brussels as part of Kunstenfestivaldesarts, at Théâtre National Wallonie-Bruxelles on 4 May 2018. It has toured to Lausanne, Barcelona, Berlin, Rome, Munich, Amsterdam, Adelaide, São Paolo, Taipei, and Edinburgh, among other places.

Production Credits

Concept, Text, and Director — Milo Rau

Research and Dramaturgy — Eva-Maria Bertschy

Dramaturgic Collaboration — Stefan Bläske, Carmen Hornbostel

Set and Costume Design — Anton Lukas

Video — Maxime Jennes, Dimitri Petrovic

Light Design — Jurgen Kolb

Technical Director — Jens Baudisch

Producers — Mascha Euchner-Martinez, Eva-Karen Tittmann

Assistant Director — Carmen Hornbostel

Assistant Dramaturg — François Pacco

Assistant Set Designer — Patty Eggerickx

Public Relations — Yven Augustin

Design — Nina Wolters

Equipment — Workshops and studios of Théâtre National Wallonie-Bruxelles

Performers

Tom — Tom Adjibi

Sara — Sara De Bosschere

Suzy — Suzy Cocco

Sébastien — Sébastien Foucault

Fabian — Fabian Leenders

Johan — Johan Leysen

La Reprise: Histoire(s) du théâtre (I)

JOHAN: What did I just do?

I entered.

I think entering is the most difficult part. Once you’re on stage, in the situation, everything is clear. You just react.

But the question is: When do you become the character? At what moment does the tragedy begin? Some actors begin in their dressing rooms. Or they identify. To “get into character.” I can’t do that. I don’t think they’re playing characters, they’re playing being actors. Just like directors who shout — they’re not directing, they’re “being” directors.

Acting is like delivering a pizza: It’s not about the delivery man. It’s about the pizza. The best actors communicate something, deliver something. And the less they stand in the way of that something the more that something can exist.

I’ve been an actor since my 20s, nearly half a century. I’ve played everything, even dead people.

Once, I played the ghost of Hamlet’s father.

Mist, please…

“I am thy father’s spirit,

Doom’d for a certain term to walk the night, And for the day confin’d to fast in fires,

Till the foul crimes done in my days of nature Are burnt and purg’d away.

But that I am forbid to tell the secrets of my prison-house,

I could a tale unfold whose lightest word would harrow up thy soul, freeze thy young blood,

Make thy two eyes, like stars, start from their spheres, Thy knotted and combined locks to part

And each particular hair to stand on end,

Like quills upon the fretful porpentine.”

That’s theatre!

A dead person speaking, a ghost. But in real life of course the dead don’t speak, they don’t even hear, they’re just dead. Although, I did hear about someone who spoke to the dead… A lawyer told me one day he had to defend a young musician, an excellent pianist, who had won first prize at the conservatory, but a hypersensitive romantic with psychological problems. His therapist suggested he go and live alone because he still lived with his mother. He found a small house near an old, ruined cemetery. Walking through the cemetery one day, he noticed some of the graves had been vandalized. They were crypts, little chapels with steps going down. And our musician became fascinated. He went down into the graves and found…people. For some reason the bodies were well-preserved and only partially decomposed. Overwhelmed by a great loneliness he brought a body home. He made a hole in his ceiling to hide it. And now and again, when he felt very lonely he would bring the body out and sit it in an armchair, for company. Then he brought back a second body, a woman… And then a child… And finally a baby. But he made the mistake of talking about it. The authorities found out, and he was arrested, accused of body snatching and desecration of a grave. And so he came to be in our lawyer’s office who found himself sitting opposite a polite young man, who could tell you everything about Chopin, Purcell, and Mozart, who could explain how to play a sonata. And the lawyer said, “I don’t understand — how do you want to talk to the dead? The dead don’t speak.” “Maybe,” says the young man, “but they can hear us.”

The Repetition

SÉBASTIEN: I studied acting at the Conservatoire in Liège and when I graduated, I stayed and lived there. Maybe some of you know Liège from the films by the Dardenne brothers? Little brick houses blackened by factory smoke, the River Meuse, slag heaps, and as far as the eye can see, blast furnaces, warehouses, factories. For 200 years, Liège was at the center of the world’s steel industry but since the ’80s all the factories have gradually been sold and boarded up. It’s as though the whole of Liège suddenly lost its job. For generations it was a city of workers but today, if you live in Liège, the chances are you’ll be unemployed. Unless of course you’re in a Dardenne brothers film.

So when, in 2012, just after the last steelworks closed, Ihsane Jarfi was murdered, it was like a symbol for the fnal decline of the city. A young man, a homosexual, killed by other young unemployed men. He got into their car by chance, a gray Polo, they undressed him, they beat him to death, and left him on the outskirts of the city, naked, on a cold, rainy night in April. His agony lasted four hours. His body wasn’t recovered until 10 days later, as it happened very close to a small wood where I often walked with my daughter and my in-laws’ border collie. So of course I sometimes think it could have been me who found the body.

The trial started two years later, in 2014. It lasted four and a half weeks. By chance, I was on holiday — well, actually, unemployed… and whenever I could, I would go to the courthouse. There were very moving moments, and very tough ones, and some were completely absurd. For instance, when for more than two hours they discussed whether Ihsane Jarfi had said to the murderers: “I want to suck a big cock.” And whether the tragedy had occurred because of that remark. In front of his mother and his whole family. I felt no sympathy for the accused but I was shocked by how the judge openly mocked their common way of speaking.

One other detail struck me: The night of the murder, before driving into the city center, one of the killers celebrated his birthday with his girlfriend in the Liège suburbs. While Ihsane Jarfi was celebrating a colleague’s birthday at the Open Bar in the city center. And the next day was his mother’s birthday. An unbelievable coincidence, or maybe just something very ordinary. During the trial I recorded the proceedings in secret and filled a dozen notebooks. I remember everything.

To recreate this story onstage we organized a casting call at the Théâtre de Liège.

JOHAN: Suzy?

SUZY: Yes.

JOHAN: Why theatre?

SUZY: I don’t know… I’m retired. I’ve taken some acting classes.

JOHAN: Age?

SUZY: 67. I think we are the same age.

JOHAN: How is it going, being retired?

SUZY: Financially it’s not ideal. Belgian pensions aren’t great. But I make some money dog-sitting for rich people.

JOHAN: How much do you make doing that?

SUZY: If I have them two or three weeks, it’s not bad. Last month I made 600 euros and so I was able to go to Sardinia.

JOHAN: Cash in hand?

SUZY: Of course, otherwise there wouldn’t be anything left.

JOHAN: Cocco, that’s not a Belgian name…

SUZY: No, my father was Sardinian, he arrived in Liège in ’48.

JOHAN: He came to work in the mines.

SUZY: Yes.

JOHAN: You’re married?

SUZY: I was married, but I got divorced in ’87. My husband preferred a fake blonde.

JOHAN: Children?

SUZY: I have two sons. And I took in a Libyan refugee.

JOHAN: To make a few bucks?

SUZY: No, actually I work more to be able to feed him.

JOHAN: Do you believe in God?

SUZY: No.

JOHAN: But you’re Italian!

SUZY: I’m a communist.

JOHAN: Have you ever been in a movie?

SUZY: I was an extra in the last Dardenne brothers film, The Unknown Girl.

JOHAN: What was it about?

SUZY: Well, as usual, it takes place in Seraing, which is the old mining area in Liège.

JOHAN: Where Ihsane Jarfi’s killers came from?

SUZY: Yes, indeed.

JOHAN: What did you do in the film?

SUZY: I had to drive up in my car. I used up all my gas because the Dardenne brothers made me do it at least five times. When I saw the movie, you don’t even see me, except passing by for a second in the distance. For 50 euros! I thought they were going to fill my tank, but no.

JOHAN: Have you done theatre before?

SUZY: Yes, once, in an amateur show. The Doctor in Spite of Himself. I played Christine, the woodcutter’s wife.

JOHAN: Ah… Molière… Can you cry?

SUZY: Now? No.

JOHAN: Try… You have to think of something sad. What are you thinking about?

SUZY: About my friend who died.

JOHAN: Do you miss her?

SUZY: Yes, every day… I can’t.

JOHAN: Have you ever done anything extreme?

SUZY: In the last play, I played an old lady who had been abandoned. It was a reference to abandoned dogs. I had to crawl around on all fours.

JOHAN: Show us!

(She takes a few steps on all fours.)

SUZY: Like this… A dog.

JOHAN: You can sit down again. Have you ever done any nude scenes?

SUZY: No one has ever asked me to.

JOHAN: Would you?

SUZY: I’m 67 — it might be a bit late.

JOHAN: Would you do it with me?

SUZY: I don’t know.

JOHAN: Thank you Suzy.

SARA: Fabian?

FABIAN: Yes?

SARA: You are a forklift driver?

FABIAN: Yes.

SARA: Have you always done that?

FABIAN: No. I was a bricklayer for 15 years. But I didn’t like it, it wasn’t for me. So a lot of the time I was late to work, and drunk. And then I hurt my back so I stopped and got my forklift license to drive a Clark. But I’m having a hard time finding work in that field. It seems everybody in Liège is a forklift operator. When the factories closed, everybody thought that was the thing to do.

SARA: Why are you interested in the theatre?

FABIAN: Recently I went on a professional reorientation seminar and apparently I have an artistic profile.

SARA: There’s a lot of unemployment. It must be difficult?

FABIAN: The statistics say there’s one job for every sixty unemployed people.

Speaking of the unemployed…do you know this joke? Tw o unemployed guys are in a café drinking beer and

SÉBASTIEN: Fabian, can you speak more clearly?

FABIAN: Yes, sorry. So… Two unemployed guys are in a bar drinking beer and reading the paper… One says to the other: “Look —unemployment’s up again.” The other guy thinks and says: “Well, they must be happy with us then.”

SARA: You like telling jokes?

FABIAN: Yes.

SARA: Fabian, have you ever done theatre before?

FABIAN: A few times, some small parts.

SARA: Why does it interest you?

FABIAN: There’s a certain freedom in theatre… You can do things that you can’t do in real life.

SARA: Have you ever kissed anyone onstage?

FABIAN: Once.

SARA: Can you kiss me?

FABIAN: Yes.

SARA: And have you ever hit anybody onstage?

FABIAN: No.

SARA: Can you hit me?

FABIAN: You? A gentle tap?

SARA: Yes — hit me.

(He slaps her slightly.)

SARA: Harder.

(He slaps her a little harder.)

SARA: Look, there’s a technique. (She shows him a fake slap.)

(He tries.)

SARA: What’s important is the reaction of the person who gets hit.

(He fake-slaps her hard — she falls on the ground.)

SARA: You can go back to your table. What is that machine?

FABIAN: A sampler. I can play all kinds of sounds. Birds. A city. Rain. Applause. I put that on after sex.

SARA: So you’re a DJ?

FABIAN: Well, I make electronic music.

SARA: Who’s your favorite artist?

FABIAN: Aphex Twin.

SARA: Which song do you like best?

FABIAN: “Polynomial C.”

SARA: Why?

FABIAN: It’s a piece that’s very sad but it has a catchy beat. That combination of sadness and energy moves me.

Do you want to hear it?

SARA: Yes.

(He turns on the music.)

SÉBASTIEN: Tom?

TOM: Fabian, turn the music off please.

SÉBASTIEN: Why do you do theatre?

TOM: Why I do theatre? Because for me it’s the school of life. No, I don’t know. To make people laugh.

SÉBASTIEN: Why did you come to these auditions?

TOM: You were looking for a young North African.

SÉBASTIEN: Yes… But you you’re from Benin, aren’t you?

TOM: No, I’m from Lille.

SÉBASTIEN: You know what I mean.

TOM: No, I don’t. My mother is French, my father is originally from Benin. But they always offer me Arab roles. And I’ve been told I look a little like Ihsane Jarfi.

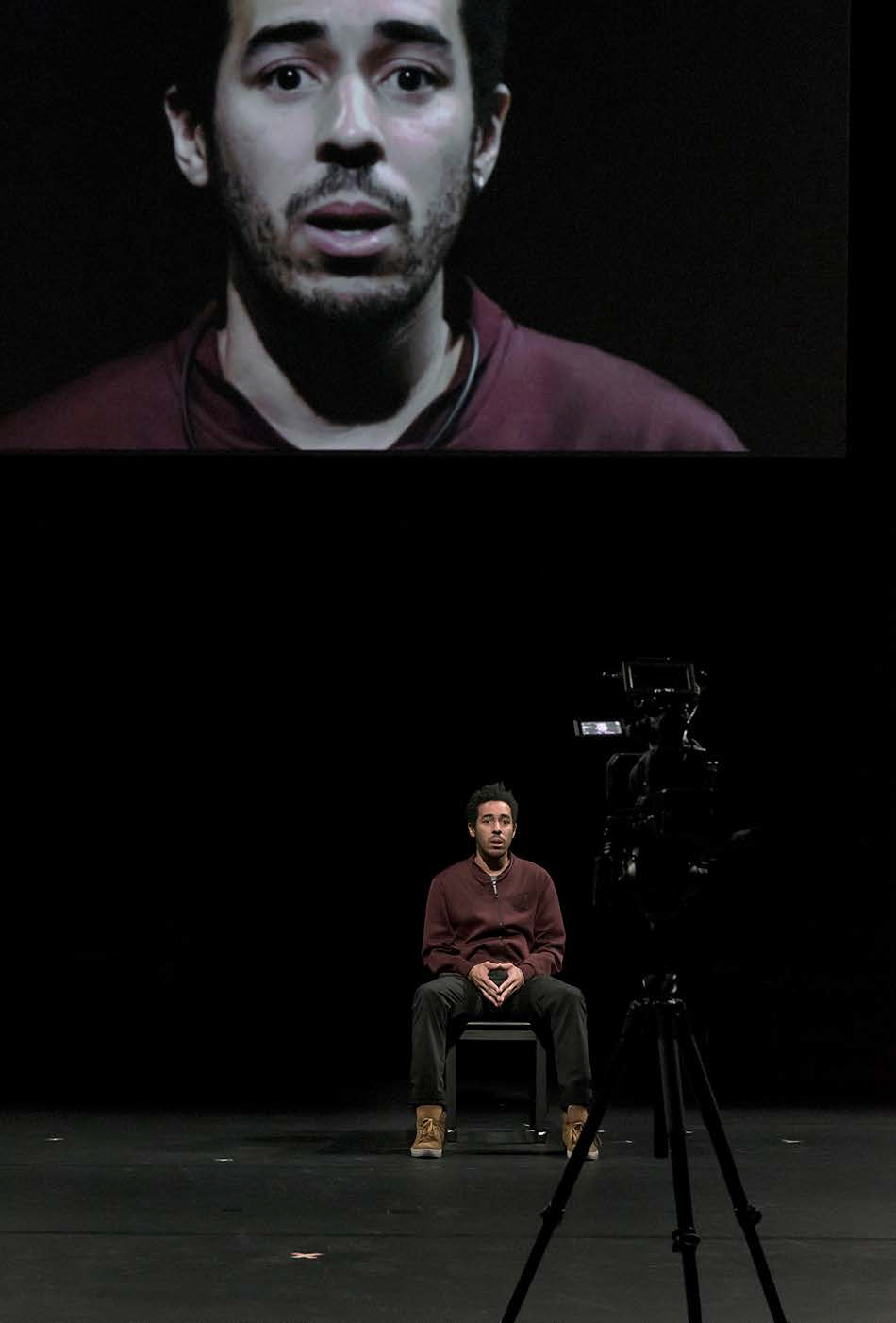

Figure 2 Tom Adjibi’s audition during which he says that people have told him he looks like Ihsane Jarfi. La Reprise: Histoire(s) du théâtre (I), Milo Rau and Ensemble. Théâtre National, Brussels, May 2018. (Photo by Hubert Amiel)

SÉBASTIEN: You do!

TOM: A few years ago I went to an audition for a Dardenne brothers film. They were looking for a black African. So I sent them my CV and they called me in. So I sent them some photos and I never heard from them again. I think they thought I wasn’t black enough for the role. I left messages but no response. So the day of the auditions I went to their offices in Liège without an appointment and they gave me a slot anyway. I wasn’t right physically because my sister and my mother were black in the film. They said: “Maybe you could play Kader, an Arab.” But Kader was in his 40s. So eventually they gave me the part of the doctor.

JOHAN: A doctor — that’s good, right?

TOM: Yes, for once it was OK. Thanks, Dardenne brothers. But it bothers me that people never ask me to play a character, just an origin. I get offered “the Arab” or “the mixed-race man” or “the multicultural youth,” but never “the bad guy” or “the good guy” or “the mad man,” whatever. If you’re black you either get to play a black person, or you do political theatre where you criticize that you only play black people. Or you do dance. So I’ve developed some strategies.

SÉBASTIEN: What strategies?

TOM: I went to an audition where they wanted people who spoke several languages. On my resumé I said I spoke Beninese and Danish. Which isn’t true at all, I don’t speak either one. So I spent the day pretending.

SÉBASTIEN: Can you show us?

(TOM speaks fake Danish.)

TOM: The problem was there was a Swedish girl who actually spoke Danish… Obviously she didn’t have a clue what I was saying… So I asked her quietly in English, “Please, pretend you understand.”

SÉBASTIEN: And Beninese? How do you do that?

TOM: The trick is to add a few words that are the same in every language. Like YouTube or Coca Cola, it makes it credible.

SÉBASTIEN: Show us!

(He speaks fake Beninese.)

TOM: I can also speak Arabic if you need it.

SÉBASTIEN: What’s your favorite music?

TOM: At the moment I’m listening to a lot of classical music. “The Cold Song” for instance. I don’t know why, that song really gets me.

SÉBASTIEN: What is it?

TOM: It’s by Purcell. It’s the story of a man who begs the God of Love to let him freeze to death.

SÉBASTIEN: Have you ever done anything extreme onstage?

TOM: Not really… I’ve made myself throw up a few times.

SÉBASTIEN: What do you think would be the most radical act on stage?

TOM: There’s a scene in a book by Wajdi Mouawad that completely sums up what I think theatre is. He imagines an empty stage with a chair in the middle. Just above the chair, there’s a noose. A character tells the audience that he is going to stand on the chair and put the noose around his neck. Then he’s going to kick the chair away and hold onto the rope to prevent himself being strangled. He says that in rehearsals he can last about 20 seconds. The character climbs on the chair, puts the noose around his neck and he kicks the chair away. Either someone will save him and he survives. Or, the audience doesn’t move and the character dies. The actor dies.

Chapter I The Loneliness of the Living

SÉBASTIEN: The day after Ihsane Jarfi dies is his mother’s birthday. It’s a normal Sunday in April.

The sky above Liège is gray. It’s a little cold, the beginning of spring. Like every evening around 11:00 p.m., before I go to bed, I am walking my dog.

(On the bed. SUZY’s awake, naked. She gets up and sits on the bed.)

JOHAN: You’re awake… What time is it?

SUZY: Nearly midnight.

JOHAN: Can’t you sleep?

SUZY: No… He didn’t come.

JOHAN: You know what he’s like.

SUZY: Yes, that’s the problem.

JOHAN: Don’t worry. He’s living his life. But you’re right, he shouldn’t forget his mother’s birthday.

SUZY: He’s not answering the phone or my texts.

(JOHAN takes his phone and dials Ihsane’s number.)

JOHAN: Voicemail. That is odd, indeed.

SUZY: So?

JOHAN: So what… You want me to call the police? He’s not a child, he’s 32… Remember when he disappeared with his boyfriend without telling us?

SUZY: It’s not the same… I don’t think you care much.

JOHAN: What?

SUZY: Ihsane…his life.

JOHAN: Come here.

(He kisses her.)

SUZY: I’m scared.

(They kiss again.)

JOHAN: He’ll call tomorrow. I’m going to sleep now.

JOHAN: Sound? Are you ready?

SUZY: Yes.

JOHAN: Camera! Go on Suzy.

SUZY: I remember it very clearly. It was the Tuesday after my birthday that my husband said: “Ihsane has disappeared.” He was kidnapped on Sunday and we found out on Tuesday. I thought: “Disappeared? No.” It feels like you’re in a movie, and it’s all unreal. Like they’re telling a story and I’m not in it.

JOHAN: Then they found his body.

SUZY: When the trial started it was very hard for me. My husband gives lectures on homophobia, he speaks publicly about the relationship he had with his son, about how he had a hard time accepting his homosexuality. I want to keep him for myself. I don’t want Ihsane to be put on show. I don’t like people talking about what he did. It’s private. I don’t like his life being on display.

When I spoke at the trial I didn’t express myself well. Talking in public like that… Whenever I have to talk about him, I feel I’m messing it up. I don’t know, it’s a weird feeling. Even now, I can’t defend him properly. I feel like a failure.

Figure 3 Suzy Cocco and Sabri Saad El Hamus step into the roles of the parents of the victim, Ihsane Jarfi, and the difference between amateur and professional actors collapses. La Reprise: Histoire(s) du théâtre (I), Milo Rau and Ensemble. Ghent, Belgium, 18 January 2019. (Photo by Michiel Devijver)

JOHAN: During the trial Ihsane became the accused. As if he had provoked this crime, with something he said, or how he behaved with the others. Some witnesses said incredible things. They even went back to kindergarten to check if maybe he wasn’t guilty.

Why did he get into that car? Because if he said “Get out of here!” to the girl who was talking to the murderers outside the Open Bar, it means he could feel the danger. Why did he go off with them if he warned the girl off? That’s the question that looms in my mind. He could have gone back into the café, or, I don’t know…

We asked the lawyer, since we hadn’t seen the autopsy report — we asked whether he realized he was going to die. Whether he was still alive, naked, in the night, in the rain. She said that, according to the doctor, he was unconscious when they left him. There are a lot of questions about what happened. Why did they go so far? Why didn’t they stop? They could have given him a chance. A couple days later they went for dinner in Maastricht with their wives. Their lives went back to normal. They even went on holiday to the seaside…

SUZY: My husband, my daughter, even his ex-boyfriend feel more than I do, I think. Because sometimes they get signs, manifestations. But Ihsane doesn’t appear to me. Not even in my dreams. All I know is that he’s not here, he doesn’t exist anymore. My husband is very religious but I can’t do it… People say: “You’ll see him again.” And I think: no, no, no… That’s the problem. I won’t see him ever again. We won’t see each other again.

JOHAN: Cut!

How do you feel?

SUZY: I’m a little cold.

JOHAN: Let’s get dressed.

Chapter II The Pain of the Other

SÉBASTIEN: During the trial of Ihsane Jarfi’s killers there was one character witness who made a strong impression on me: Ihsane’s ex-boyfriend. He spoke to the accused directly, but not to say: “you bastards, you monsters!” No, what he said was: “I’m going to try to describe the man you killed. He was a good person.” He tried to explain to the killers and to the jury what it means when a human life disappears, how it hurts, how it is irreparable. In his testimony he built a mausoleum for his friend.

During research for this play we met him several times. He can’t forget because it was such a senseless death. Why did Ihsane leave the Open Bar just then? Why did he get into the gray Polo? Why did he have to suffer?

(In the Open Bar. The birthday party. The camera follows JOHAN walking through the party. JOHAN talks with FABIAN (DJ). SARA and JOHAN toast. TOM and SÉBASTIEN are talking at the bar. SARA hugs TOM. TOM and SÉBASTIEN kiss. TOM leaves.)

SÉBASTIEN: He comes out of the Open Bar, he gets in their car, they drive towards the wharves, they beat him up. On the way, near the stadium, they stop, put him in the trunk and keep going… And that’s when Ihsane prays, in Arabic, in the trunk… So he felt he was going to die. He understood. He must have been terrified because he saw the evil in their eyes, the evil we couldn’t see during the trial.

But still, on the way to the trial, I was expecting to be shocked. I don’t know… That they would give off some sort of negative energy. But when I saw their faces, that just dissipated… Because they’re just morons. Assholes who let the situation get out of control. You could almost feel sorry for them, that’s how pitiful they are. I didn’t even feel hate when I saw them. And when their families came to testify, it was the same thing, just normal people. Wintgens’s father for instance… He’s a farmer, a country guy… He walks up, takes off his cap like he’s going to Sunday mass, and he says: “If he really did this, I’m not talking to him ever again.” It was so banal. That’s when you realize how stupid Ihsane’s death was.

The most frustrating thing is knowing that I can’t feel what he felt. It’s stupid but, now, when I go to the dentist, for example, if I’m afraid of the pain, I think of him. Not because it helps, but just to tell myself: “I want to feel what he felt.” Those things bring me a little closer to him. But I haven’t been able to feel the terror. I’d like to feel it the way he did, to share it with him, to relieve him of that a little.

During the trial, when they showed the photos of Ihsane’s body, his family left the courtroom. I understand that they didn’t want to see that but it bothered me that they left. I thought: “He’s all alone, no one wants to look at him.” So I forced myself to stay and look… I’ll never forget: he was lying on his front, fully naked… And I recognize him… I recognize the nape of his neck, his back, his buttocks, everything… They had destroyed him, his rib cage was crushed. It was very hard, but I didn’t want to look away, I didn’t want there to be nobody to see him… Only the killers looking at him… And the people at the trial, who weren’t connected to him. I wanted to be there for him.

SARA: What kind of music do you play normally?

FABIAN: Mostly electronic music, Aphex Twin, Autechre, and Paintbox.x, which is my own project. On Rock nights I play Iron Maiden, Nirvana, and Izuma, Suzy’s son’s band.

SARA: What do you have for birthdays?

FABIAN: Joe Dassin. It’s for old people, but it works for birthdays.

Chapter III The Banality of Evil

FABIAN: I went to see Jeremy Wintgens at the prison in Marche-en-Famenne. It’s 40 minutes by car from Liège. It’s one of Wallonia’s most modern prisons, very clean, but depressing. To get to the visiting room you have to go through a lot of doors. Cameras everywhere. His gaze struck me: eyes slightly reddened like someone who has been crying or smoking a joint, or who spent too long in the dark. He had a miserable gaze, like a beaten dog.

SARA: Have you ever played bad guys?

FABIAN: So far I’ve only played bad guys.

SARA: Why?

FABIAN: Probably because of my face…

SARA: How are you going to play him?

FABIAN: I need a context, like an argument for instance… Like we did in rehearsal when we did Wintgens’s birthday party. That’s the scene that affects me the most in this, weirdly. Everything starts with two birthday parties. Wintgens becomes a killer on the night of his birthday. He said to me: “You want to know the truth?” I should have stayed at home. I should have stayed with my girlfriend, not gone into town. I should have stayed at home.”

Roll the video please.

(SÉBASTIEN is killing a jogger in Grand Theft Auto. SARA and FABIAN kiss for a long time. FABIAN gets more and more intrusive.)

SARA: Give me the bottle.

(She rips the bottle out of his hands. She stands up and leaves.)

FABIAN: After the birthday party they took off in the car. Parmentier was driving. They went into the center. Wintgens doesn’t remember how they got to the Open Bar. They had downed five or six bottles of scotch. But he does remember what kind of music was playing. It was rap. He told me: “If it had been my car, it would have been Rammstein or Marilyn Manson.” Outside the Open Bar they tried to pick up a girl, and that’s when Ihsane Jarfi intercedes. He approaches the passenger window and starts talking to Wintgens. Ihsane offers to take them to meet some girls and gets in the car. Wintgens said he only hit him two or three times. And that towards the end, when the others got out to undress and kill Ihsane, he stayed in the car. But that’s his version. I don’t know. At one point he opened the door. Took some fresh air. Did he get out to join in? Or to stop them? He doesn’t know. It’s too cold. It’s raining. And he does nothing.

Figure 4 The murderers are shown on the center screen as they drive the car onstage. La Reprise: Histoire(s) du théâtre (I), Milo Rau and Ensemble. Théâtre National, Brussels, May 2018. (Photo by Hubert Amiel)

What struck me is that Wintgens’s life is a copy of mine: I lived alone with my alcoholic mother until she died when I was 11. Wintgens lived alone with his mother until he was 12. Then I went to live with my dad. Wintgens went to live with his. He became a bricklayer, so did I. He had back problems and ended up unemployed, just like me. He had the same car as me. When I met him in prison, I told him all this, that we had the same life. He looked at me and said: “You’re lucky you’re doing this play. It’s a great opportunity. Make the most of it.”

Chapter IV The Anatomy of the Crime

(In the Polo, SÉBASTIEN behind the wheel, FABIAN in the passenger seat and SARA in the back. SUZY at the window is talking to FABIAN.)

SUZY: I’m in the Open Bar with some friends.

FABIAN: Well, come with us, we can have some fun.

SUZY: No, it’s my friend’s birthday, I can’t leave her.

FABIAN: Go and get your friend. We like to party with pretty girls like you.

SUZY: No I can’t.

FABIAN: C’mon… You’ve got pretty eyes.

SUZY: I’m sure I do.

FABIAN: C’mon.

SUZY: No. Some other time maybe. (He tries to touch her breasts.) Stop it! No.

TOM: Hey guys, guys, what’s going on?

FABIAN: We’re on chick patrol.

TOM: I know a good place to have a good time if you’re interested.

FABIAN: With hot girls?

TOM: Yeah, yeah, don’t worry.

FABIAN: No beached whales?

TOM: No, no.

FABIAN: Where is it?

TOM: Right behind Guillemins.

FABIAN: What’s the street?

TOM: I don’t know the address.

FABIAN: Get in, you can show us.

TOM: Yeah, but I’m at a birthday party.

FABIAN: Don’t worry, we’ll bring you back afterwards.

TOM: For sure?

FABIAN: Yeah, don’t worry.

(TOM steps in car.)

FABIAN: Are we gonna get blow jobs at least?

TOM: Yeah by girls, guys, whatever you want.

FABIAN: Guys? What are you, some kind of faggot?

SARA: Get out of here!

TOM: What the fuck? Is this guy for real? What — you’ve never sucked a big cock?

SÉBASTIEN: You want to suck a big cock? Is that it?

(SÉBASTIEN hits TOM first, and the others follow.)

TOM: Stop… I want to get out… Stop the car! Why is it locked?

SÉBASTIEN: You want to get out? You will get out, don’t worry… (SÉBASTIEN stops the car, steps out and opens the door for TOM.)

SÉBASTIEN: Get out, princess.

SARA: Out! Out! Out!

SÉBASTIEN: Open the trunk.

(SÉBASTIEN and SARA put TOM in the trunk, hit him again and go back in the car.)

SÉBASTIEN: Fuck, a car! Move his feet.

(SARA hits TOM in the trunk. TOM prays in Arabic.)

SÉBASTIEN: This isn’t a fucking mosque, shut your face.

SARA: Shut the fuck up!

(After driving for a while, they stop the car. SÉBASTIEN and SARA pull TOM out of the trunk.)

SÉBASTIEN: Fucking dog!

(SÉBASTIEN and SARA beat TOM up and undress him. FABIAN gets out of the car, pukes and gets back in his seat. SÉBASTIEN urinates on TOM, lying naked. The car is pulled back. Lights are back on stage. SÉBASTIEN finds the body.)

SÉBASTIEN: On May 1st 2012, International Workers’ Day, Ihsane Jarfi’s body was found by a man walking his dog. According to the medical examiner the body was found in a field, near a high voltage tower, in the ventral decubitus position. His body temperature was 14.3°C, the temperature outside. At that moment the death of Ihsane Jarfi became a matter of public interest.

Chapter V The Rabbit

SARA: During the rehearsals, we met Ihsane’s ex-boyfriend one more time. He came to the theatre in Liège. We had just got back from a visit to a blast furnace… I can picture it now — we were sitting around the table: Johan, Sébastien, Suzy, Tom, Fabian and I… He said:

“I just didn’t know how to deal with it. I had been to a psychologist… But you know, psychologists, they’re fine, but they don’t always understand. Anyway that wasn’t what I was looking for. I wanted a sign. A sign from Ihsane. So one day a friend said to me, ‘why don’t you go to that woman?’ A clairvoyant. So off I went. She was a real ‘Madame Irma.’ And I showed her a photo of Ihsane. I had brought a photo that was different from the ones that had been in the news — he was wearing a hat, and had a huge smile; It was impossible to recognize him. She looks at the photo and says: ‘He’s dead. I can feel it, everything is spinning.’ So I shut down straight away and think: ‘she’s going to bring her box of tricks out now…’ But she started going deeper, and she says: ‘was he b…b…beaten… They beat him up?’ And she looks up and she says: ‘They beat him to death.’ I said: ‘that’s enough, stop it — obviously you saw this on TV and you’ve recognized him.’ But then she said: ‘I… Isha… Isha…’ and she told me personal things, words we used to say to each other, things she couldn’t possibly know. And well…I lost it… I was… I said: ‘I don’t believe you, this is a scam.’ I was quite aggressive. I said: ‘I need a sign. I came here for a sign!’ And then she started concentrating again — look I’m just telling you what I experienced — she concentrated, and said: ‘You’re going to come across something — a key ring, a rabbit’s foot…something soft, with fur, something you can stroke… In two or three weeks, a rabbit’s foot, you’ll come across it. I thought to myself: what’s that supposed to mean? Tw o weeks later, I was in Italy with my new boyfriend, in Verona. It was a beautiful winter’s day, it was noon, bright sunshine, amazing light! We were walking in the hills, everything was beautiful, idyllic, and an intense sadness came over me. I asked myself: why? It is all too beautiful, too lovely. I thought about Ihsane all day. And next day, before we left, I was looking at postcards in one of those spinning racks. I was turning it and turning it and suddenly — I felt something…something soft. I look down and…it wasn’t a rabbit’s foot but it was a soft fur key ring. At the moment I wasn’t surprised, I first thought, well, there’s a whole row of these things — you fnd them everywhere. But then I thought: When have I ever just had one of these in my hand? Never!

Figure 5 Tom Adjibi as Jarfi is shown in the trunk of the car on the center screen. La Reprise: Histoire(s) du théâtre (I), Milo Rau and Ensemble. Théâtre National, Brussels, May 2018. (Photo by Hubert Amiel)

And some time later, I was working in this restaurant, and every evening I went home on my scooter, and every day I happened to pass the house where Ihsane and I used to live. The road goes up steep, and every time, my scooter wouldn’t make it and would stop, I would go for the gas, but it wouldn’t make it. And every time the trip seemed endless! One day I couldn’t face taking that same road every time. Something broke in me, I said to Ihsane, I screamed it: ‘When am I going to be able to get on with my life? When is this going to stop? When will I stop moping around!’ And that very moment — believe it or not — a rabbit crossed the road.”

We’ve done five acts, as is the way. But there’s a poem, that speaks beautifully about the sixth act. It’s by Szymborska.

“For me, tragedy’s most important act is the sixth:

Figure 6 Jarfi, played by Tom Adjibi, is beaten to death in front of the car in which he was taken to the outskirts of town. La Reprise: Histoire(s) du théâtre (I), Milo Rau and Ensemble. Théâtre National, Brussels, May 2018. (Photo by Hubert Amiel)

The raising of the dead from the stage’s battlegrounds

The straightening of wigs and fancy gowns

Removing knives from stricken breasts,

Standing in a row with the living, and facing the audience.

Bowing, separately and together,

Pale hand on wounded heart,

The curtsies of the hapless suicide

The incline of the chopped-off head.

Bowing, two by two,

Rage extending its arm to softness,

Victim smiling with executioner,

Rebel and tyrant stepping forward together.

Eternity is trampled by a golden slipper’s toe,

Morality swept aside with the swish of a hat.

The irrepressible urge to do it all again tomorrow.

Then come marching those who died in earlier acts

The miraculous return of the disappeared.

The idea that they have been waiting patiently in the wings, Still in costume,

Still in their makeup,

Moves me more than any tragic monologue.”

JOHAN: Can you sing that song?

TOM: By Purcell?

JOHAN: Yes.

TOM: Fabian can you dance?

FABIAN: No, that’s why I’m a DJ.

TOM: Still, you are going to dance!

FABIAN: OK, but then with the Clark.

JOHAN: Mist, please!

(TOM sings “The Cold Song” while FABIAN dances with the Clark.)

TOM: Johan talked about the problem of starting. How to enter? But I think the end is even harder. How to end? How do you know it’s over?

There is an actor.

There is a chair in the center of the stage.

There is a noose hanging over the chair.

The actor climbs on the chair.

He puts the noose around his neck.

He says that he is going to kick the chair away.

It’s the final scene.

Either someone will save him and he survives. Or the audience doesn’t move, and he dies.

THE END