Introduction

E-mental health is one of the fastest growing fields in mental health research (Schmidt & Wykes, Reference Schmidt and Wykes2012) and can be defined as the ‘use of digital technologies and new media for the delivery of screening, health promotion, prevention, early intervention, treatment, or relapse prevention as well as for improvement of health care delivery (e.g. electronic patient files), professional education (e-learning), and online research in the field of mental health’ (Riper et al. Reference Riper, Andersson, Christensen, Cuijpers, Lange and Eysenbach2010). Given the current international pressure for improving mental health care, the use of technology may hold great promise. In particular, it has been suggested that internet-based mental health interventions have the potential to overcome traditional barriers to care, and also to reduce the demand on clinicians at lower costs (Christensen & Hickie, Reference Christensen and Hickie2010). Currently, computerized interventions are available for a broad range of disorders, particularly common mental disorders such as depression and anxiety (Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Cuijpers, Craske, McEvoy and Titov2010; Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Farrer and Christensen2010), eating disorders (Beintner et al. Reference Beintner, Jacobi and Taylor2012; Dölemeyer et al. Reference Dölemeyer, Tietjen, Kersting and Wagner2013) and substance abuse and dependence (Tait & Christensen, Reference Tait and Christensen2010), along with other conditions such as tinnitus (Kaldo et al. Reference Kaldo, Levin, Widarsson, Buhrman, Larsen and Andersson2008), chronic pain (e.g. Chiauzzi et al. Reference Chiauzzi, Pujol, Wood, Bond, Black, Yiu and Zacharoff2010) or irritable bowel syndrome (Ljotsson et al. Reference Ljotsson, Hedman, Andersson, Hesser, Lindfors, Hursti, Rydh, Ruck, Lindefors and Andersson2011).

The vast majority of e-mental health interventions are based on cognitive-behavioral principles (Schmidt & Wykes, Reference Schmidt and Wykes2012). This is unsurprising, given that cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) has demonstrated efficacy across a range of mental disorders (Butler et al. Reference Butler, Chapman, Forman and Beck2006). In addition, CBT approaches translate well into computerized interventions, as they are based on learning models in which the therapist (or other support worker) has the function of a teacher or coach who imparts important information to the patient and teaches them a set of reproducible skills (Musiat & Schmidt, Reference Musiat, Schmidt and Agras2010). Patients are often encouraged to put these skills into practice between treatment sessions. Furthermore, CBT interventions are characterized by being systematic and operationalized and are frequently detailed in a treatment manual or protocol. This format has lent itself well to translation of interventions into self-help materials and, more recently, into computer and internet programs. For this reason, the focus of the present review is on CBT e-mental health interventions only. In addition, many of the putative advantages are based on the comparison with face-to-face CBT. There is some inconsistency in the field with regard to the use of the terms e-mental health, mobile health (m-health), internet-based interventions, web-based interventions and computerized interventions (Eysenbach et al. Reference Eysenbach2011). In the following, we use the term computerized CBT (cCBT) to describe CBT interventions delivered through technology, including CDROM, internet and mobile devices.

The clinical efficacy of cCBT has been the focus of numerous reviews (e.g. Anderson & Jacobs, Reference Anderson and Jacobs2004; Foroushani et al. Reference Foroushani, Schneider and Assareh2011), which generally provide support for the efficacy of cCBT. Particularly for the most common mental disorders anxiety and depression, meta-analyses have found effect sizes that compare to face-to-face therapy (Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Cuijpers, Craske, McEvoy and Titov2010). There is no consensus as to whether therapist support improves outcomes in cCBT. A meta-analysis of depression interventions by Andersson & Cuijpers (Reference Andersson and Cuijpers2009) found higher effect sizes for interventions with support (d = 0.61) compared to those without (d = 0.25), whereas another review suggests that this is not necessarily the case (Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Farrer and Christensen2010). However, these reviews emphasize that more research is needed with regard to the cost-effectiveness and specific mechanisms of change, along with the efficacy of specific interventions. Given the strong evidence base for efficacy, it is somewhat surprising that the field is characterized by the slow transition of effective interventions into practice (Whitfield & Williams, Reference Whitfield and Williams2004). To date, only three interventions are specifically recommended in the UK national treatment guidelines, including one for depression, one for panic/phobia and one for obsessive–compulsive disorders (NICE, 2008, 2009a , b ). The dearth of systematic research on the putative advantages of e-mental health may account for this. Hence, it is possible that e-mental health has yet failed to demonstrate distinct advantages over traditional routes of care. Although it could be argued that research into the efficacy of interventions has priority over investigating these advantages, it is important to note that most of the research in e-mental health is triggered by the assumption that computerized treatments can overcome some of the shortfalls of traditional interventions, such as limited availability and high costs.

Assumed added benefits in e-mental health

There are numerous opinion papers, editorials and reviews highlighting a range of potential benefits of cCBT over traditional delivery platforms. Through a review of these articles and discussion with field experts, commonly quoted added benefits of cCBT interventions were identified.

Among the most commonly assumed advantages is the increased flexibility for patients with regard to time and location of accessing treatment (Robinson & Serfaty, Reference Robinson and Serfaty2003; Cuijpers et al. Reference Cuijpers, van Straten and Andersson2008; Carroll & Rounsaville, Reference Carroll and Rounsaville2010). In the UK and the USA, approximately 20% of the population live in rural areas (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010; ONS, 2011) whereas in less developed areas in the world, this figure is more than 50% (United Nations, 2012). Mental health care in these areas is characterized by lower availability of services, greater distances to specialist care and greater reluctance to seek help due to the lack of anonymity in close communities (Aisbett et al. Reference Aisbett, Boyd, Francis, Newnham and Newnham2007). Given that interventions can be delivered entirely through a computerized system, it is assumed that users can access their treatment at any time and when they need it the most. Within mental health, stigma is a major barrier for seeking help and a large proportion of patients do not approach practitioners because they feel embarrassed about their problem (Wrigley et al. Reference Wrigley, Jackson, Judd and Komiti2005). Several authors suggest that cCBT can reduce the barriers for help-seeking by providing a non-stigmatizing treatment alternative (Robinson & Serfaty, Reference Robinson and Serfaty2003; Proudfoot, Reference Proudfoot2004; Titov, Reference Titov2007; Spurgeon & Wright, Reference Spurgeon and Wright2010). On the one hand, this implies that some individuals may find cCBT less stigmatizing than face-to-face treatment and are therefore more likely to engage with these interventions. On the other hand, this implies that, after using cCBT, individuals are more likely to seek help through specialized services (Titov, Reference Titov2007). In addition, cCBT is assumed to reduce waiting times for treatment, be more cost-effective (Illman, Reference Illman2004; Spurgeon & Wright, Reference Spurgeon and Wright2010) and reduce the workload on mental health professionals (Titov, Reference Titov2007; Christensen & Hickie, Reference Christensen and Hickie2010; Spurgeon & Wright, Reference Spurgeon and Wright2010). Treatment satisfaction is not traditionally quoted as a particular advantage of cCBT. However, it is generally implied that the advantages outlined above make cCBT more attractive than other forms of care, at least to some. In addition, satisfaction with an intervention is one of the most important secondary outcome criterion in the evaluation of health interventions (Ruggeri, Reference Ruggeri1994).

Given that research in e-mental health has focused primarily on efficacy and the frequent assumption that such interventions have numerous advantages, the present paper aimed to review the evidence on the assumed added benefits of cCBT interventions for mental health problems (e.g. symptoms) and mental disorders as defined in DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000). We reviewed controlled trials investigating added benefits of interventions for children, adolescents and adults against waitlist controls or other interventions. The benefits reviewed include: cost-effectiveness, geographic flexibility, time flexibility, waiting time for treatment, stigma, therapist time, help-seeking behavior and treatment satisfaction. The evaluation of added benefits is important to establish whether cCBT has advantages over traditional care and to allow a transition of such interventions into clinical practice.

Method

Data sources and search terms

The electronic databases Medline (from 1950 to the present) and Web of Science were searched from their earliest date until 31 January 2013 for English publications investigating the efficacy of CBT interventions targeting mental health problems delivered through, or with the help of, technology. The following terms were used in the search: (‘CBT’ OR ‘cognitive behaviour therapy’ OR ‘cognitive behavior therapy’ OR ‘cognitive behavioural therapy’ OR ‘cognitive behavioral therapy’) AND (internet* OR web OR online* OR computer*) AND (trial OR randomi* OR effect*). Given the high number of papers identified in the search, no further search of references within papers was deemed necessary and was not performed. The present review was conducted according to the standards outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009).

Study inclusion criteria

Studies had to fulfill the following inclusion criteria: (a) the study was published in a peer-reviewed journal; (b) the study reports a controlled or randomized controlled intervention trial; (c) the intervention uses a cognitive-behavioral treatment model; (d) the intervention was delivered through computer technology, including CDROM, email, internet, mobile devices; (e) the intervention targets mental disorders as defined by the DSM-IV-TR or symptoms or risk factors of such; and (f) the study has evaluated at least one of the added benefits as outlined above.

Procedures and data extraction

Search results were imported into Endnote X5. In an initial step, titles and abstracts were screened to identify review articles, opinion papers, meta-analyses and other papers that did not meet inclusion criteria. Full text articles were obtained for the resulting papers and then reviewed by the first author (P.M.). If doubts about inclusion arose, the paper was referred for a second opinion. Data were extracted from the papers meeting the inclusion criteria by two raters (P.M. and N.T.). This included: type of trial and control conditions, cost-effectiveness (direct intervention costs, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, probability of cost-effectiveness), geographic limitations (location of participants, proportion of urban/rural participants), time flexibility (time/frequency of intervention access), waiting time (time between assessment and intervention), stigma (stigma ratings before/after intervention), therapist time (time spent with each participant), treatment satisfaction (self-rated scales, proportion of satisfied participants), and help-seeking (frequency of use of services). Given the number and heterogeneity of outcomes, a quantitative synthesis of the extracted data (e.g. a meta-analysis) was not conducted. An assessment of risk to evaluate risk of bias in individual studies and across studies was not undertaken. This was primarily because, in most cases, included papers were efficacy trials and the reviewed outcomes were secondary outcomes.

Results

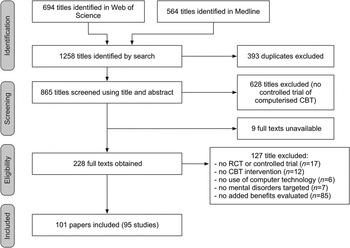

In total, 1258 papers were identified in the online search. Figure 1 illustrates the selection process of the included studies. Duplicates were removed and, after screening the paper titles and abstracts, a further 628 titles were removed from the database, as they were not randomized or controlled trials, did not use CBT or did not use computerized technology for the delivery of treatment. The full texts for 228 papers were obtained for further review and 127 titles were removed, as they did not fulfill the inclusion criteria. The final set of articles included in this review consisted of 101 publications of 95 different studies. Articles included were published between 2001 and 2013, with the vast majority having been published within the past 5 years. A complete list of articles included in this review is given in the online Supplementary Material.

Fig. 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the review process.

Cost-effectiveness

Thirteen (14%) of the included studies included some form of economic evaluation of the tested intervention. Within these studies, different approaches were used for this evaluation, including comparison of direct and indirect treatments costs, cost-effectiveness analyses, cost-utility analyses, incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) or quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). Table 1 shows the results of studies with economic evaluation of cCBT.

Table 1. Summary of studies with economic evaluation of computerized cognitive behavior therapy (cCBT)

iCBT, Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; GSH, guided self-help; TAU, treatment as usual; TRQ, Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire; CI, confidence interval; s.d., standard deviation.

Results reported in currencies other than US$ were converted into US$ using the conversion rate at the time of the review.

Geographic flexibility

Of the 95 studies included in this review, only three papers (3%) provided information about the location of intervention users. All three studies were trials in Australia. In the first study, a cluster-randomized trial investigating the efficacy of an internet-based intervention targeting anxiety and depression in adolescents (MoodGym), more than 16% of participants reported living in a rural environment (Calear et al. Reference Calear, Christensen, Mackinnon, Griffiths and O'Kearney2009). The second study investigated the same intervention (MoodGym) in adults and reported 20% of participants being located in a remote or rural area (Christensen et al. Reference Christensen, Griffiths, Mackinnon and Brittliffe2006a ). The third paper (Kay-Lambkin et al. Reference Kay-Lambkin, Baker, Kelly and Lewin2011) reported results from a trial comparing face-to-face CBT with motivational interviewing (MI), clinician-assisted cCBT/MI therapy and face-to-face person-centered therapy for depression with harmful substance use. In this trial, 41% of participants were from a rural environment.

Time flexibility

Only one paper (1%) provided information on the time of day when users accessed the intervention. In an internet-based guided self-help (GSH) treatment for binge eating disorders, users primarily accessed the website between 20:00 and 23:00 h, that is outside regular working hours (Carrard et al. Reference Carrard, Crepin, Rouget, Lam, Golay and Van der Linden2011).

Length of waiting for treatment

Of the studies in this review, only four papers (4%) provided information on the length of time participants had to wait for treatment. In three of these studies, participants were recruited from a waiting list of patients for face-to-face treatment (Carlbring et al. Reference Carlbring, Ekselius and Andersson2003, Reference Carlbring, Nilsson-Ihrfelt, Waara, Kollenstam, Buhrman, Kaldo, Soderberg, Ekselius and Andersson2005, Reference Carlbring, Maurin, Torngren, Linna, Eriksson, Sparthan, Straat, von Hage, Bergman-Nordgren and Andersson2011). The average waiting times in these studies ranged from seven (Carlbring et al. Reference Carlbring, Nilsson-Ihrfelt, Waara, Kollenstam, Buhrman, Kaldo, Soderberg, Ekselius and Andersson2005) to 15 months (Carlbring et al. Reference Carlbring, Ekselius and Andersson2003). However, this waiting time cannot be attributed to the design of those studies or the availability of the intervention, but is associated with the service participants were recruited from and the time of recruitment into the trial. The fourth study (Kaldo et al. Reference Kaldo, Levin, Widarsson, Buhrman, Larsen and Andersson2008) reported the waiting time between the first assessment of the study and the start of treatment with either a cCBT intervention or a group intervention targeting tinnitus distress. In this study, both intervention groups (internet versus group CBT) waited on average 16 days before treatment commenced.

Stigma

None of the studies reviewed provided information on whether participants perceived cCBT as less stigmatizing prior to enrolling in a study. Two studies (2%) reported stigma within the context of a cCBT trial (Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Christensen, Jorm, Evans and Groves2004; Farrer et al. Reference Farrer, Christensen, Griffiths and Mackinnon2012) and both reported the effect of using cCBT on stigma. In the first study (Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Christensen, Jorm, Evans and Groves2004), participants either accessed a depression literacy website (BluePages), a computerized CBT website (MoodGym) or an attention control condition (weekly interviews). With regard to stigma, the authors found a significant interaction between time and intervention group, suggesting a different effect on stigma between the interventions. Compared to the attention control condition, both internet-based interventions significantly reduced personal stigma, that is the individual's negative beliefs about mental health problems. However, with regard to perceived stigma, that is beliefs about other people's negative view of mental health problems, the authors found that the CBT intervention website increased stigma, whereas no change was observed in the other intervention groups. The second study (Farrer et al. Reference Farrer, Christensen, Griffiths and Mackinnon2012) compared cCBT for depression with and without telephone support, telephone support only and a waitlist control group in a randomized trial. Overall, no significant interaction between time and intervention group was observed for personal stigma. However, between-group contrasts suggested that participants in the cCBT condition without telephone support showed significantly lower levels of stigma than participants in the control condition. Twelve months after the intervention, no differences were observed. In both studies, stigma was assessed using a scale developed by one of the study authors (Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Christensen, Jorm, Evans and Groves2004).

Therapist time

Of the included studies, 53 (56%) provided information on the amount of therapist involvement. It should be noted that this information is only relevant in studies that compared cCBT with therapist-led treatments or in which the computerized intervention included some form of therapist involvement. The included studies demonstrated a large variety of possible ways for therapists to facilitate patients in the use of computerized intervention, including providing telephone support, assessing patients, monitoring discussion forums, responding to emails, participating in chat rooms or brief face-to-face sessions. Similarly, the time spent on each participant over the course of treatment varied between only a few minutes (Furmark et al. Reference Furmark, Carlbring, Hedman, Sonnenstein, Clevberger, Bohman, Eriksson, Hallen, Frykman, Holmstrom, Sparthan, Tillfors, Ihrfelt, Spak, Ekselius and Andersson2009; Hedman et al. Reference Hedman, Andersson, Ljotsson, Andersson, Ruck and Lindefors2011) and several hours (Carlbring et al. Reference Carlbring, Gunnarsdottir, Hedensjo, Andersson, Ekselius and Furmark2007; Hollandare et al. Reference Hollandare, Johnsson, Randestad, Tillfors, Carlbring, Andersson and Engstrom2011).

With regard to the question of whether cCBT can reduce the workload of mental health professionals, nine trials (9%) directly compared the amount of therapist input into cCBT with traditional forms of care, such as group therapy (five studies) or individual face-to-face treatment (four studies). In all of those studies, the time spent on each patient was considerably lower for cCBT than for face-to-face therapy. For example, Andrews et al. (Reference Andrews, Davies and Titov2011) compared the efficacy of cCBT and group therapy. In the cCBT group, therapists spent on average 18 min with each participant whereas in group therapy the time spent on each individual was 240 min. In a study comparing cCBT with face-to-face individual therapy and standard counseling (Bickel et al. Reference Bickel, Marsch, Buchhalter and Badger2008), cCBT required the least therapist time (264 min per participant), followed by standard counseling (647 min) and face-to-face CBT therapy (1198 min). Compared to group and individual face-to-face therapy, the time spent per participant in these nine studies was on average six times lower in the cCBT intervention group.

However, the reduction in workload for mental health professionals is only beneficial if it is not associated with poorer outcomes. Several studies included in this review systematically varied the intensity of therapist support to investigate whether increased involvement of a therapist (or other professional/non-professional) produces more favorable outcomes. In one randomized controlled trial (RCT), internet-based CBT (iCBT) for panic disorder was given with high and low frequency of contact (email contact with therapist three times a week versus once a week). Despite the differences in the amount of therapist time received, no differences with regard to efficacy, treatment credibility and satisfaction between the groups were observed (Klein et al. Reference Klein, Austin, Pier, Kiropoulos, Shandley, Mitchell, Gilson and Ciechomski2009). In another study, cCBT for social phobia (the Shyness program) was delivered with or without clinician support and compared against a waitlist control group. The results suggested that clinician support not only increased treatment adherence dramatically but also produced greater effects on reducing symptoms of social anxiety. The efficacy of cCBT alone was between clinician-assisted cCBT and the control group (Titov et al. Reference Titov, Andrews, Choi, Schwencke and Mahoney2008). The same intervention (the Shyness program) was administered in a later study with two different types of clinician support: telephone support and support through an online forum. Both intervention groups received a comparable amount of clinician time and large effect sizes were observed, regardless of the type of support. The type of support also had no impact on completion rates or treatment satisfaction (Titov et al. Reference Titov, Andrews, Schwencke, Solley, Johnston and Robinson2009). In a study comparing tailored versus standardized iCBT, the more tailored treatment was more effective than the standardized version but also required 30% more therapist involvement (Johansson et al. Reference Johansson, Sjoberg, Sjogren, Johnsson, Carlbring, Andersson, Rousseau and Andersson2012). Finally, one study investigated the efficacy of a computer-aided self-help intervention for obsessive–compulsive disorder and compared scheduled with requested support. Participants with scheduled support received almost five times as much therapist time as participants with on-demand support and reported higher treatment adherence, in addition to greater improvements (Kenwright et al. Reference Kenwright, Marks, Graham, Franses and Mataix-Cols2005).

Finally, in the attempt to minimize delivery costs for cCBT, there is the question of who has to deliver support and at what level of qualification. Johnston et al. (Reference Johnston, Titov, Andrews, Spence and Dear2011) investigated whether clinician support or coach support produces different outcomes in a web-based intervention for anxiety disorders. Completion rates and the time of support received were similar across the groups. To the surprise of the authors, no significant differences between clinician and coach support were observed on most outcomes. However, with regard to scores on the seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale and the 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21), the coach-supported group seemed to show greater improvements. Similar results were observed in a trial comparing clinician support with technician support, in which both types of support produced comparable outcomes, completion rates and treatment satisfaction (Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Titov, Andrews, McIntyre, Schwencke and Solley2010). In one study, participants who received technician support continued to improve whereas those with clinician support only maintained their improvements (Titov et al. Reference Titov, Andrews, Davies, McIntyre, Robinson and Solley2010). No difference in efficacy between support by experienced therapists and support by less experienced therapists was found in a study by Andersson et al. (Reference Andersson, Carlbring and Furmark2012). The authors conclude that ‘the highly structured iCBT protocol leaves less room for therapist effects and it is possible that therapist experience would have been more important in a less structured treatment’ (Andersson et al. Reference Andersson, Carlbring and Furmark2012).

Help-seeking behavior

Of the analyzed studies, four (4%) provided information on help-seeking behavior after receiving the intervention (Christensen et al. Reference Christensen, Leach, Barney, Mackinnon and Griffiths2006b ; Klein et al. Reference Klein, Richards and Austin2006; Fichter et al. Reference Fichter, Quadflieg, Nisslmuller, Lindner, Osen, Huber and Wunsch-Leiteritz2012; Nyenhuis et al. Reference Nyenhuis, Zastrutzki, Weise, Jager and Kroner-Herwig2013). In a trial specifically investigating the help-seeking behavior in depressed individuals after receiving access to a psycho-educational website (BluePages), a CBT self-help website (MoodGym) or a control condition (Christensen et al. Reference Christensen, Leach, Barney, Mackinnon and Griffiths2006b ), participants in the cCBT group were more likely to use CBT, exercise or massage than participants receiving psycho-education. A relapse prevention intervention for patients with anorexia nervosa (Fichter et al. Reference Fichter, Quadflieg, Nisslmuller, Lindner, Osen, Huber and Wunsch-Leiteritz2012) found no differences after a 9-month follow-up between patients who received the intervention and those who did not, with respect to the use of out-patients sessions. In a study comparing ‘Panic Online’ with GSH and a control condition, the cCBT intervention was most successful in reducing general practitioner (GP) visits after receiving the intervention (Klein et al. Reference Klein, Richards and Austin2006). Finally, in a study investigating the efficacy of an internet-based intervention targeting tinnitus distress, no differences between the treatment arms regarding subsequent health visits for the problem were observed (Nyenhuis et al. Reference Nyenhuis, Zastrutzki, Weise, Jager and Kroner-Herwig2013).

Treatment satisfaction

Of the 95 studies reviewed in this article, 51 (54%) provided information on treatment satisfaction. Across studies, treatment satisfaction is often assessed with very different methodologies, including validated scales, visual analog scales or open format questions. Overall, all studies included in this review reported moderate to high satisfaction with cCBT interventions.

In studies where cCBT was compared against other forms of treatment, such as face-to-face therapy, bibliotherapy or group-based treatments, satisfaction ratings for cCBT was comparable to other forms of treatment. For example, Nyenhuis et al. (Reference Nyenhuis, Zastrutzki, Weise, Jager and Kroner-Herwig2013) compared cCBT, group-based CBT, bibliotherapy and an information control condition. All active treatments were based on the same model and achieved similar satisfaction ratings, despite differences in efficacy. Khanna & Kendall (Reference Khanna and Kendall2010) compared cCBT for anxiety disorders in children with face-to-face CBT and found no differences in satisfaction ratings between the groups. Similar results were reported in other studies comparing cCBT with face-to-face CBT (Spence et al. Reference Spence, Holmes, March and Lipp2006, Reference Spence, Donovan, March, Gamble, Anderson, Prosser and Kenardy2011; Kiropoulos et al. Reference Kiropoulos, Klein, Austin, Gilson, Pier, Mitchell and Ciechomski2008; Botella et al. Reference Botella, Gallego, Garcia-Palacios, Banos, Quero and Alcaniz2009). Studies that compared treatment conditions with personal support or technician support did not report differences in satisfaction ratings between the groups (Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Titov, Andrews, McIntyre, Schwencke and Solley2010; Titov et al. Reference Titov, Andrews, Davies, McIntyre, Robinson and Solley2010).

Some studies particularly investigated whether participants felt that the computerized treatment was impersonal or whether they would have preferred personal contact as part of the intervention. For example, in an RCT of an e-mail-based treatment for work stress, 68% of participants indicated not missing the personal contact with the therapist (Ruwaard et al. Reference Ruwaard, Lange, Bouwman, Broeksteeg and Schrieken2007). Similar figures were reported in an intervention for complicated grief (Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Knaevelsrud and Maercker2006), depression (Ruwaard et al. Reference Ruwaard, Schrieken, Schrijver, Broeksteeg, Dekker, Vermeulen and Lange2009) and bulimia nervosa (Ruwaard et al. Reference Ruwaard, Lange, Broeksteeg, Renteria-Agirre, Schrieken, Dolan and Emmelkamp2013).

Discussion

We have reviewed the evidence on secondary outcomes in intervention trials for computerized cognitive behavioral treatments of mental disorders or mental health problems. With 95 studies published within the previous 20 years (and 80% of these in the past 5 years), it is evident that e-mental health is a growing field. Overall, it was noted that recent trials (i.e. published within the past 5 years) were more likely to report information on added benefits on cCBT.

One of the key findings of this review is that, for many of the claimed benefits of e-mental health interventions, there is relatively little supportive evidence at this stage. Although it was not expected that each study would tap into each possible secondary outcome, it remains somewhat surprising how little information was available on them, given how often these advantages are quoted and how easily some of the information can be assessed.

Cost-effectiveness

There is increasing evidence for the cost-effectiveness of cCBT interventions across different disorders. All papers that reported the direct costs of treatment used cCBT and suggested that, compared to other active treatment options, cCBT is the cheaper alternative, if administered alone and not in conjunction with usual care (e.g. Klein et al. Reference Klein, Richards and Austin2006; Bergstrom et al. Reference Bergstrom, Andersson, Ljotsson, Ruck, Andreewitch, Karlsson, Carlbring, Andersson and Lindefors2010). However, it is important to note that these studies did not include in their calculations those costs that are required to be met by the patients, such as costs for computer equipment and internet access, or the time required by the patient to spend with the material. This was highlighted in the study by Gerhards et al. (Reference Gerhards, de Graaf, Jacobs, Severens, Huibers, Arntz, Riper, Widdershoven, Metsemakers and Evers2010), which took direct and indirect costs into consideration. The studies included in this review suggest that the cost-effectiveness of cCBT interventions largely depends on two factors: (a) costs of treatments already in place and (b) how much societal value is put on the clinical improvement in a particular disorder (e.g. Hedman et al. Reference Hedman, Andersson, Lindefors, Andersson, Ruck and Ljotsson2013). Additionally, none of the studies reported the development costs of the intervention or incorporated them into the cost-effectiveness analysis. This is important because the costs for developing can be significant, particularly with increasing complexity of an intervention. Similarly, in the reviewed studies, license costs for the intervention were not included. Most of the few evidence-based cCBT interventions implemented in services are not free of charge. These license costs have to be met by the patient or health-care provider. Nevertheless, license costs for cCBT are often less than 10% of the costs of face-to-face CBT. On balance, the results from the economic evaluation of e-mental health interventions suggest that cCBT is a cost-effective alternative to usual care, achieving results that are similar to, or better than, usual care, at lower direct costs. When delivered in addition to usual care, or where other forms of care are not in place, the direct intervention costs of e-mental health are higher, but are outweighed by the reduced societal costs (e.g. through work loss). With an increasing pressure on health-care budgets (e.g. across Europe and the USA), the importance of e-mental health is likely to rise, as it offers to maintain or even improve the standard of care at much lower costs.

Geographic flexibility

Only three studies investigated the potential of e-mental health interventions for overcoming geographic barriers, despite the assumption of easy access to care for rural populations. We compared the rates of rural study subjects reported in these trials to statistical information (AIHW, 2004) and found that they roughly mirrored the percentage of rural population to be expected for the recruitment area. Given this small number of studies, it remains difficult to evaluate the potential of cCBT for overcoming geographical barriers. It is understandable that, to some extent, this is due to trial-related factors, such as many trials being conducted in densely populated areas and recruitment taking place only in these areas. However, in most cases the geographic location of participants was simply not assessed. Without a doubt, the mode of delivery in cCBT health allows for the delivery of care in remote locations, but whether this potential is used remains to be investigated more systematically. In rural areas, access to mental health care is not just limited by the distance to available services. Handley et al. (Reference Handley, Kay-Lambkin, Inder, Attia, Lewin and Kelly2013) investigated the feasibility of computerized treatment for mental health in rural Australia and found high-speed internet access to be less available in rural areas, therefore limiting access to computerized interventions. In addition, only 20% considered using an internet-delivered treatment in the future. This suggests that the flexibility of computerized treatments in rural areas can only be exploited by addressing both accessibility and acceptability of such interventions. It is likely that these issues can only be overcome in a close collaboration between health-care providers, intervention developers, service users and communication service providers.

Time flexibility

Similar to the geographic limitations, it is surprising how little information about the access times of the intervention is assessed or presented in trials. In the study that did report this information, users access the intervention in the evening at a time when face-to-face care is unlikely to be available. This does suggest that users exploit the time flexibility of cCBT, but the results stem from only one study. One of the current key challenges in the field is to determine who benefits from these interventions and how. Information on intervention usage, such as time and length of access, can be easily obtained by technical means and could provide valuable information on this issue. Accessibility may well be an advantage of cCBT but this has not yet been quantified. In addition, the flexibility for users is potentially counterproductive in an evaluation trial where participants ideally complete the entire intervention in a given time-frame. Although some papers reported the percentage of users completing a certain proportion of an intervention, this information could be considered instead as an indicator of attrition. It should be noted, however, there are qualitative data suggesting that users of cCBT value highly the ability to access interventions without having to take time off work (McClay et al. Reference McClay, Waters, McHale, Schmidt and Williams2013). Assessing whether time flexibility is used and valued is not only important with regard to evaluating added benefits but could also contribute to the development of new interventions, which take the preferences of users into account (e.g. shorter intervention components, higher frequency).

Length of waiting times for treatment

Only four studies provided information on waiting times for treatment. Although one study reported a very short time between the first assessment and the start of cCBT, it is unlikely that such a short waiting time would be reflected in most public services. Similar to the issues described earlier, the low number of studies reporting waiting times may be due to trial-related factors. If cCBT is not offered as part of usual care but as part of a trial, waiting lists might not exist or can be avoided. Hence, the evidence for cCBT reducing waiting times for treatment is very weak at this stage. The effect of being on a waitlist for treatment has been studied extensively in substance use disorders. Despite the burden for the individual, longer waiting times are associated with higher physical risk (Pollini et al. Reference Pollini, McCall, Mehta, Vlahov and Strathdee2006), higher health-care costs (Hunkeler et al. Reference Hunkeler, Hung, Rice, Weisner and Hu2001) and increased pre-treatment and treatment drop-out (Redko et al. Reference Redko, Rapp and Carlson2006). However, it should be noted that, in the context of a research trial, a significant proportion of individuals on the waitlist improve without any intervention (e.g. Posternak & Miller, Reference Posternak and Miller2001). In the stepped-care approach, it has been suggested that cCBT (or other evidence-based self-help) is offered as a first step for milder cases or to bridge the time between specialist care (Andrewes et al. Reference Andrewes, Kenicer, McClay and Williams2013). Thus, the question of whether cCBT can reduce waiting times may not be answered entirely through RCTs. Future research needs to include more detailed information about the treatment history of participants, including information on waiting times for treatment, or compare care pathways within services implementing cCBT and those that do not.

Stigma

Given that no study provided information on stigma prior to taking up cCBT, it remains unclear as to whether cCBT is initially perceived as less stigmatizing than other forms of treatment and therefore engages individuals in treatment who otherwise would not have sought help. The results on stigma after using cCBT raise the question of whether computerized mental health interventions could increase stigma. The two studies reporting the effect of cCBT on stigma used a non-standardized measure, making it difficult to compare the results to other studies or populations. Both studies found reduced personal stigma after cCBT. However, Griffiths et al. (Reference Griffiths, Christensen, Jorm, Evans and Groves2004) found increased perceived stigma after using cCBT whereas this domain was not assessed or reported by Farrer et al. (Reference Farrer, Christensen, Griffiths and Mackinnon2012). This raises the question of whether cCBT reinforces the user's beliefs on mental disorders being stigmatized in society. As these results are only from two studies, more research on computerized interventions and their effects on stigma should be undertaken, particularly with regard to the effect of stigma on help-seeking. With more research into stigma in e-mental health, interventions can be developed that target this issue directly. In addition, therapists supporting patients in a computerized intervention should be aware of this issue and how it can be addressed.

Therapist time

The variety of trials included in this review demonstrate that cCBT is not per se associated with reduced workload on therapists. Instead, the amount of time required largely depends on factors such as intervention design and trial design. In those trials directly comparing the time requirements for mental health professionals between cCBT and face-to-face interventions, cCBT required significantly less input from a therapist or professional than group or individual therapy. However, cCBT should not necessarily replace face-to-face interventions but can be used as an adjunct to treatment or within stepped care. For those scenarios, investigating whether cCBT reduces (or distributes) the workload for mental health professionals in the long term would require more complex and longitudinal research designs.

It is important to consider whether the reduced workload on mental health professionals comes at the cost of reduced efficacy of interventions. On balance, the evidence suggests that, compared to no support, personal support in cCBT can increase treatment efficacy and adherence, and reduce drop-out. In addition, it seems to make little difference whether a clinician, coach or technician delivers this personal support.

With regard to the working mechanism in cCBT and how personal support affects adherence, outcomes and satisfaction, the results of this review clearly indicate that more research is needed. Although it is understandable that the focus of previous studies has been primarily on the association between personal support and effectiveness of the intervention, future research needs to address the issues of treatment adherence in this field. Other indirect issues to be considered when computerized interventions largely or completely replace therapist contact are issues of governance and specifically risk assessment of harm to self or others. If cCBT significantly replaces therapist contact, it is not clear how these issues will be addressed, whereas in therapist contact situations, at least within public services, some type of operational policy will exist to deal with the assessment of such risk. In future research on e-mental health, any consequential adverse effects of governance, or lack of governance, need to be recorded and highlighted. With the increasing use of e-mental health intervention, the role of therapists could change in the near future. The caseload of face-to-face patients could reduce and be replaced by a caseload of electronically supported patients. As a consequence, the structure of mental health services needs to change to facilitate the transition of such intervention into practice and accommodate the needs of service users (e.g. by providing personal support) and therapists (e.g. by providing dedicated supervision arrangements).

Help-seeking behavior

The results from the reviewed studies on help-seeking behavior after receiving cCBT are difficult to interpret. On the one hand, cCBT could reduce barriers to seeking treatment, resulting in an increased likelihood of accessing further treatment. On the other hand, subsequent health visits of any kind could also be interpreted as a failure to reduce symptomatology. In addition, severity of the condition, selection and drop-out effects can skew the results. With regard to the impact of cCBT on help-seeking behavior, more long-term studies are required, in which patients are followed through the course of their illness. This information should be combined with a costs-effectiveness analysis to create strong evidence for the use of such interventions.

Treatment satisfaction

Data on treatment satisfaction in all reviewed studies were usually only available from individuals who remained in the trial and were assessed post-intervention or at follow-up. One of the main problems in e-mental health is the high rate of attrition, particularly in open access interventions (for a review, see Melville et al. Reference Melville, Casey and Kavanagh2010). One possible reason for not completing a study is dissatisfaction with the intervention itself. The results from the studies in this review on balance suggest that individuals are generally satisfied with cCBT interventions, but this satisfaction may be overestimated, given that data come from individuals who were successfully recruited into the trial and remained in it. Little is known about those who may not have started the intervention because of preconceptions towards cCBT or dissatisfaction with the intervention after starting it. Another indicator of treatment satisfaction is adherence to the intervention. Poor adherence (e.g. completing only a few treatment modules) may indicate dissatisfaction with the intervention, poor usability or lack of perceived effectiveness, but may also be due to improvements in the condition, lack of time and motivation. However, adherence to computerized intervention has been reviewed elsewhere (Christensen et al. Reference Christensen, Griffiths and Farrer2009; Donkin et al. Reference Donkin, Christensen, Naismith, Neal, Hickie and Glozier2011). Although the results on treatment satisfaction with cCBT are promising, future research should address these issues specifically, assessing how satisfaction with cCBT affects treatment adherence and attrition. Where possible, treatment satisfaction should be assessed with standardized measures and early during an intervention (Eysenbach et al. Reference Eysenbach2011).

Limitations

There are some limitations to this review requiring consideration. Two search engines were used for the search and there was no hand searching for eligible studies. Hence, it is possible that some relevant papers were missed in this process. In addition, a risk of bias assessment was not undertaken. This was because the reviewed papers were primarily efficacy studies whereas this review assessed how the added benefits of cCBT are reported. However, it is possible that some of the issues relevant with regard to risk of bias within individual studies also affect the reporting of added benefits. For example, insufficient blinding of participants or high drop-out rates may skew treatment satisfaction ratings. Similarly, differences between studies may increase the risk of bias across studies. For example, cost-effectiveness analyses are resource intensive and are more likely to be available for large and well-funded trials. A caveat to the findings from this review is the fact that many studies did not primarily aim to provide information on added benefits. This makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions for some of the outcomes discussed. In many cases there is simply a lack of adequate comparison groups to provide evidence for the added benefit of cCBT.

Conclusions

In summary, there seems to be a gap between research on cCBT and the implementation into care and it is likely that some of the supposed advantages can only be investigated in the context of a large-scale implementation. With the evidence for the efficacy of e-mental health increasing, future research should focus more on the working mechanisms of these interventions, in addition to the added benefits. Only if evidence for these benefits is found will service providers and patients accept cCBT as an alternative to usual care.

With the expanded CONSORT guidelines for e-health (Eysenbach et al. Reference Eysenbach2011), it is expected that the evidence base for these benefits will further improve. These extended guidelines recommend the detailed reporting of human involvement in trials, for example to what extent study participants had contact with a therapist or technician. It is recommended that parameters of treatment use or dosage, such as the number of logins or time spent with the intervention, are defined and reported. The guidelines suggest collecting and reporting detailed user demographics, given the digital divide (e.g. reduced digital access in older adults) in e-health research. This information will further contribute to our understanding of collateral outcomes, such as therapist time, cost-effectiveness, geographic and time flexibility and treatment satisfaction. In addition to the points addressed in the e-health CONSORT guidelines, the use of standardized measures for the assessment of collateral outcomes is recommended. Particularly in the assessment of treatment satisfaction or stigma, numerous unstandardized measures were used in the publications reviewed. The use of standardized measures will help in the comparison of results between studies and potentially build a more solid evidence base for the added benefit of computerized treatments. It is hoped that this review will contribute to the field by encouraging research groups to investigate the supposed advantages of e-mental health in more detail, as this will not only improve the quality of interventions themselves but also move such interventions into implementation on a large scale.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714000245.

Acknowledgments

The authors were supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at the South London and Maudsley National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust and the Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London. This article presents independent research funded by the NIHR. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Declaration of Interest

None.