Introduction

Depression is one of the most debilitating mental disorders in the general population, strongly associated with a reduced quality of life, work disability, cardiovascular disease (Beutel et al., Reference Beutel, Wiltink, Kirschner, Sinning, Espinola-Klein, Wild, Munzel, Blettner, Zwiener, Lackner and Michal2014), and premature death (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Vogelzangs, Twisk, Kleiboer, Li and Penninx2013). Its prevalence was 7.2% in the general population aged 25–74 years based on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Beutel et al., Reference Beutel, Wiltink, Kirschner, Sinning, Espinola-Klein, Wild, Munzel, Blettner, Zwiener, Lackner and Michal2014). The vulnerability–stress model (Spijker et al., Reference Spijker, De Graaf, Bijl, Beekman, Ormel and Nolen2004) posits sociodemographic, psychological, somatic, and behavioral risk factors.

With regard to sociodemographic factors, women were about twice as likely to develop depression during their life time as men (Timm et al., Reference Timm, Ubl, Zamoscik, Ebner-Priemer, Reinhard, Huffziger, Kirsch and Kuehner2017). While older cohorts of men and women had a decreased incidence of depression, incidence remained higher in women. However, evidence for late-onset depression (>60 years) has been scarce (Aziz and Steffens, Reference Aziz and Steffens2013), and the greatest gender gap in incident depression has been found in middle age (Bogren et al., Reference Bogren, Brådvik, Holmstrand, Nöbbelin and Mattisson2017).

In a meta-analysis on the associations with socioeconomic status (SES) (Lorant et al., Reference Lorant, Deliege, Eaton, Robert, Philippot and Ansseau2003), prevalence studies (N = 51) prevailed over incidence and persistence studies (N = 5, each). Odds of a new episode of depression were increased in low SES. However, compared with the odds of persistent depression [odds ratio (OR) = 2.06], the magnitude was lower (OR = 1.24); dose–response relationships were found for lower education, income, and SES (Groffen et al., Reference Groffen, Koster, Bosma, Van Den Akker, Kempen, Van Eijk, Van Gool, Penninx, Harris, Rubin, Pahor, Schulz, Simonsick, Perry, Ayonayon, Kritchevsky and Health2013).

As psychological factors, early childhood adversity in addition to a family history of depression (Timm et al., Reference Timm, Ubl, Zamoscik, Ebner-Priemer, Reinhard, Huffziger, Kirsch and Kuehner2017), increased the risk for depressive and anxiety disorders later in life (Gibb et al., Reference Gibb, Chelminski and Zimmerman2007). Further, neuroticism and negative emotionality predicted the onset of major depressive disorder (MDD) episodes in community samples (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Kotov and Bufferd2011). Major stressful life events (SLE) have been identified as precursors of depression (Kendler et al., Reference Kendler, Karkowski and Prescott1999). While men reported more work-related and legal problems and women reported more interpersonal problems (Kendler et al., Reference Kendler, Thornton and Prescott2001), life event categories had similar depressogenic effects in men and women (Vrshek-Schallhorn et al., Reference Vrshek-Schallhorn, Stroud, Mineka, Hammen, Zinbarg, Wolitzky-Taylor and Craske2015). Loneliness as an important social stress factor (Beutel et al., Reference Beutel, Klein, Brahler, Reiner, Junger, Michal, Wiltink, Wild, Munzel, Lackner and Tibubos2017b) was a risk factor for incident depression (Green et al., Reference Green, Copeland, Dewey, Sharma, Saunders, Davidson, Sullivan and Mcwilliam1992), whereas social support was associated with lower depressive symptoms (Beutel et al., Reference Beutel, Brahler, Wiltink, Michal, Klein, Junger, Wild, Munzel, Blettner, Lackner, Nickels and Tibubos2017a). In a twin study, women reported higher levels of social support than men. However, social support reduced the risk of subsequent depression only in women (Kendler et al., Reference Kendler, Myers and Prescott2005).

Generalized anxiety disorder has a high lifetime comorbidity with depressive disorders (Coplan et al., Reference Coplan, Aaronson, Panthangi and Kim2015); due to their early age of onset, anxiety disorders may precede depression. For example, anxious adolescents with a tendency to ruminate were more vulnerable to subsequent depressive symptoms (Starr et al., Reference Starr, Stroud and Li2016). A systematic review (Hardeveld et al., Reference Hardeveld, Spijker, De Graaf, Nolen and Beekman2010) found that larger numbers of previous depressive episodes and residual symptoms increased the risk of recurrence. Subclinical depression adversely affected functioning and quality of life, which may contribute to an increased incidence of depression (Rodriguez et al., Reference Rodriguez, Nuevo, Chatterji and Ayuso-Mateos2012).

The relationship between depression and behavioral factors is complex: depression has been related to physical inactivity and increased consumption of tobacco and alcohol. Recent meta-analyses found more incident depression in obesity (ORs between 1.21 and 5.18), particularly in women (Rajan and Menon, Reference Rajan and Menon2017). In a recent study, baseline smoking was associated with incident depression 5 years later (Cabello et al., Reference Cabello, Miret, Caballero, Chatterji, Naidoo, Kowal, D'este and Ayuso-Mateos2017).

Regarding somatic factors, increased depressive symptoms were found in cardiovascular disease, diabetes (Wiltink et al., Reference Wiltink, Beutel, Till, Ojeda, Wild, Munzel, Blankenberg and Michal2011), cancer (Hartung et al., Reference Hartung, Brahler, Faller, Harter, Hinz, Johansen, Keller, Koch, Schulz, Weis and Mehnert2017), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and other chronic diseases. Given the link between multimorbidity and depression (Spangenberg et al., Reference Spangenberg, Forkmann, Brahler and Glaesmer2011), in an aging sample, somatic conditions need to be ascertained. However, studies investigating the significance of chronic disease for the onset of depression in the general population have been scarce. In a recent systematic review (Bernardini et al., Reference Bernardini, Attademo, Cleary, Luther, Shim, Quartesan and Compton2017), out of 12 studies predicting MDD, five focused on patients with medical disorders, and only two were from the general population.

This paper is based on a unique, comprehensive large longitudinal population-based aging sample, analyzing the effects of sociodemographic, psychological, behavioral, and somatic baseline data on new onset of depression 5 years later. We took care to exclude participants who were depressed at baseline, who had reported a previous diagnosis of depression or who had taken antidepressants. Our aims were:

(1) To determine the point prevalence of depression in individuals who had not shown evidence of depression at baseline 5 years earlier,

(2) To determine the combined impact of a broad range of social, psychological, behavioral, and somatic predictors of new onset of depression.

Methods

Procedure and study sample

As described by Wild et al. (Reference Wild, Zeller, Beutel, Blettner, Dugi, Lackner, Pfeiffer, Münzel and Blankenberg2012), the Gutenberg Health Study (GHS) is a population-based, prospective, observational single-center cohort study in the Rhine-Main-Region, Germany. Its primary aim is to analyze and improve cardiovascular risk factors and their stratification. The study protocol and documents were approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Chamber of Rhineland-Palatinate and the local data safety commissioner. All study investigations were conducted in line with the Declaration of Helsinki and principles outlined in recommendations for Good Clinical Practice and Good Epidemiological Practice. Participants were included after informed consent. The sample was drawn randomly from the local registry in the city of Mainz and the district of Mainz-Bingen, stratified 1:1 for gender and residence and in equal strata for decades of age. Inclusion criterion was age 35–74 years. Insufficient knowledge of German language, psychological, or physical impairment with regard to participation led to exclusion.

At baseline, 15 010 participants were examined between 2007 and 2012. Of those, 14 732 (98.1%) filled out the PHQ-9. A total of 12 422 took part in the follow-up (82.8%). Of those, N = 12 140 filled out the PHQ-9 (97.7%). Thus, 12 061 filled out the PHQ-9 on both occasions. Eight hundred seventy-seven were excluded due to a PHQ-9 ⩾ 10 at baseline, 971 had reported a history of depression, and 177 took antidepressant medication (N07a). Thus, analyses were based on N = 10 036 participants. Participants who fulfilled inclusion criteria and were lost to follow-up (N = 1850) were slightly more often female, older, had a lower SES, and suffered more frequently from chronic disease and cardiovascular risk factors; however, there were no differences regarding depression, generalized anxiety, or panic at baseline; social phobia was even slightly lower in drop-outs.

Materials and assessment

The 5-h baseline examination in the study center comprised the evaluation of prevalent classical cardiovascular risk factors and clinical variables, a computer-assisted personal interview, laboratory examinations from venous blood samples, blood pressure, and anthropometric measurements. All examinations were performed according to standard operating procedures by certified medical technical assistants.

Measures

Sociodemographic variables and psychological measures were assessed via self-report: sex, age in years, employment (no/yes), income, living with partner (no/yes), and SES. SES was defined according to Lampert et al. (Reference Lampert, Kroll, Müters and Stolzenberg2009) from 3 (lowest SES) to 21 (highest SES) based on education, profession, and income.

Psychological measures

The Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS), a widely used checklist (Scully et al., Reference Scully, Tosi and Banning2000; Hobson and Delunas, Reference Hobson and Delunas2001), provides a standardized measure of the impact of a wide range of SLE. An adapted German version with 36 items was administered (Cronbach's α = 0.81); the latter were rated based on their occurrence in the past years (0 = no, 1 = yes). For analyses, we used the unweighted scores.

Loneliness was assessed by a single item ‘I am frequently alone/have few contacts’ rated as 0 = no, does not apply; 1 = yes it applies, but I do not suffer from it; 2 = yes, it applies, and I suffer slightly; 3 = yes, it applies, and I suffer moderately; 4 = yes, it applies, and I suffer strongly. Loneliness was recoded combining 0 and 1 = no loneliness or distress; 2 = slight; 3 = moderate; and 4 = severe loneliness (Beutel et al., Reference Beutel, Klein, Brahler, Reiner, Junger, Michal, Wiltink, Wild, Munzel, Lackner and Tibubos2017b).

Social support was assessed by the Brief Social Support Scale (BS6; Beutel et al., Reference Beutel, Brahler, Wiltink, Michal, Klein, Junger, Wild, Munzel, Blettner, Lackner, Nickels and Tibubos2017a). Six items (three per scale) assessed emotional and tangible support with good reliability (total scale α = 0.86). Items were rated from 1 = never, 2 = occasionally, 3 = mostly to 4 = always available.

Depression was assessed with the PHQ-9 at baseline and follow-up. Caseness at follow-up was defined by a score ⩾10. Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe, Grafe, Zipfel, Witte, Loerch and Herzog2004) found a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 82% for depressive disorder determined by this cut-off. Internal consistency for the PHQ-9 was good (Cronbach's α = 0.80).

Generalized anxiety was assessed with the two-item short form of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, Monahan and Lowe2007). A sum score of 3 or higher (range 0–6) among these two items indicated generalized anxiety with good sensitivity (86%) and specificity (83%) (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, Monahan and Lowe2007).

The German version of the Mini-Social Phobia Inventory (Mini-Spin) was used to detect social anxiety. A cut-off score of 6 (range 0–12) separated individuals with generalized social anxiety disorder and controls with good sensitivity (89%) and specificity (90%) (Wiltink et al., Reference Wiltink, Kliem, Michal, Subic-Wrana, Reiner, Beutel, Brahler and Zwerenz2017).

Panic disorder was screened with the brief PHQ panic module. Caseness was defined if at least two of the first four PHQ panic questions were answered with ‘yes’ (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Grafe, Zipfel, Spitzer, Herrmann-Lingen, Witte and Herzog2003).

Type D personality was assessed with the German version of the DS14 (Denollet, Reference Denollet2005) comprising two reliable subscales with seven items each for negative affectivity and social inhibition, rated on a five-point Likert scale (0 = false to 4 = true). Type D was defined by a cut-off of 10 on both subscales.

Behavioral measures

Health behavior included smoking, which was dichotomized into non-smokers (never smoker and ex-smoker) and smokers (occasional smoker, i.e. cigarette/day, and smoker, i.e. cigarette/day).

Obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) ⩾30 kg/m2 (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Alcohol consumption was measured in gram per day; alcohol abuse was defined as daily consumption ⩾60 mg for men and ⩾40 mg for women.

Physical activity was inquired with the Short Questionnaire to Assess Health-Enhancing Physical Activity (SQUASH; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Brage, Westgate, Franks, Gradmark, Diaz, Huerta, Bendinelli, Vigl, Boeing, Wendel-Vos, Spijkerman, Benjaminsen-Borch, Valanou, Guillain, Clavel-Chapelon, Sharp, Kerrison, Langenberg, Arriola, Barricarte, Gonzales, Grioni, Kaaks, Key, Khaw, May, Nilsson, Norat, Overvad, Palli, Panico, Quiros, Ricceri, Sanchez, Slimani, Tjonneland, Tumino, Feskens, Riboli, Ekelund, Wareham and Consortium2012). The SQUASH captures commuting, leisure time, household, work, and school activities. Sleeping, lying, sitting, and standing were classified as inactivity (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Brage, Westgate, Franks, Gradmark, Diaz, Huerta, Bendinelli, Vigl, Boeing, Wendel-Vos, Spijkerman, Benjaminsen-Borch, Valanou, Guillain, Clavel-Chapelon, Sharp, Kerrison, Langenberg, Arriola, Barricarte, Gonzales, Grioni, Kaaks, Key, Khaw, May, Nilsson, Norat, Overvad, Palli, Panico, Quiros, Ricceri, Sanchez, Slimani, Tjonneland, Tumino, Feskens, Riboli, Ekelund, Wareham and Consortium2012). Active sports was presented in quartiles with Q1 denominating the lowest and Q4 the highest quartile of physical activity.

Interview assessments

During the computer-assisted personal interview, participants were asked whether they had ever received a definite diagnosis of any depressive or anxiety disorder by a physician (medical history of lifetime diagnosis of any depressive, respectively, anxiety disorder). The presence of coronary heart disease was assessed by the question: ‘Were you diagnosed with a stenosis of your coronary vessels?’ Self-reported myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and peripheral arterial disease were summarized as cardiovascular risk diseases (CVD); cancer and COPD were assessed the same way.

Diabetes was defined in individuals with a definite diagnosis of diabetes by a physician or a blood glucose level of ⩾126 mg/dl in the baseline examination after an overnight fast of at least 8 h or a blood glucose level of >200 mg/dl after a fasting period of 8 h.

Medications were registered on site at the GHS study center by scanning the bar codes from the original packages of the drugs of participants. Medication use was described by the ATC code. Three classes of antidepressants were selected and entered as dichotomous variables (yes/no): non-selective monoamine reuptake inhibitors (ATC N06AA), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (ATC N06AB), and other antidepressants (ATC N06AX).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed as absolute and relative proportions for categorical data, means, and standard deviations for continuous variables and median with interquartile range if not fulfilling normal distribution. Inference tests between depression groups (no/yes) were calculated with t tests or χ2 tests.

In order to determine new onset of depression at follow-up, based on the baseline data, we excluded subjects with a medical history of depression, intake of antidepressant medication, and increased depression scores (PHQ ⩾ 10) at baseline. In order to identify predictors of new onset of depression, we performed logistic regression analysis with depression (PHQ-9 sum score ⩾ 10) as the criterion at follow-up including sociodemographic, psychological, behavioral, and somatic factors assessed at baseline (model 1). In order to determine the effect of subclinical depression, we additionally included the PHQ-9 score at baseline (model 2). In order to identify sex effects, we also analyzed women and men separately.

The p < 0.05 was considered significant. Because of the explorative nature of the study, no Bonferroni tests were conducted. All p values should be regarded as continuous parameters that reflect the level of statistical evidence, and they are therefore reported exactly. Statistical analysis was carried out using R version 3.3.1.

Results

Table 1 gives an overview of the study participants according to the presence of depression at follow-up (separate tables for men and for women cf. online Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics stratified for new onset of depression

Table 1 shows the overall rate of new onset of depression as 4.4%. Depression was significantly associated with female sex, younger age, lower SES, income, and living without a partner. A higher rate of employment may be due to younger age of depressed participants. As psychological vulnerability factors, they had an increased proportion of type D personality. Participants with new onset of depression reported more life events at baseline, more loneliness, generalized anxiety, social phobia, panic and history of anxiety, and less social support. They smoked more often and reported less physical activity; there was no difference regarding obesity. Overall, there were no differences regarding the prevalence rates of somatic diseases.

Comparing supplementary baseline Table 1 for men and Table 2 for women, baseline differences emerged. Depressed men, but not women, had a lower SES, lived less often with a partner, had a higher BMI, and performed active sports less often.

Table 2. Logistic regression models of new onset of depression: model 1 excluding depression measure (PHQ-9) at baseline v. model 2 including subclinically depressed participants (PHQ-9 < 10) at baseline

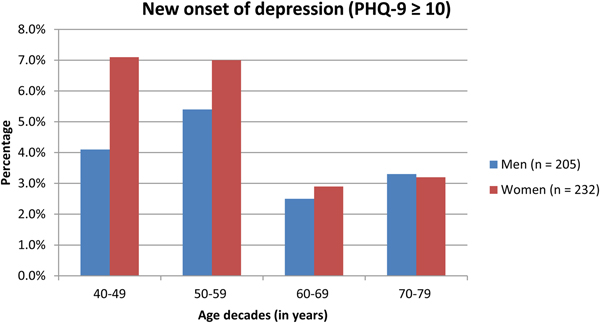

Figure 1 shows the comparison of new onset of depression of men and women by age decade.

Fig. 1. Comparison of new onset of depression in men and women across age decades.

The figure shows that the higher rate of depression in women was due to their excess morbidity in the younger age groups. In the youngest age group, women's proportion exceeded men's by 73%, in middle age by 30%, and in the elderly population, there was no more difference, while the proportion of participants with new-onset depression declined.

Table 2 shows multivariate logistic regression analyses of new onset of depression for all participants. Model 1 excludes and model 2 includes depression score at baseline.

According to model 1, younger age was a demographic predictor of depression, while female sex was no longer significant. Among the psychological factors, type D personality, comorbid cancer, and smoking were predictive of new onset of depression. This also applied to loneliness and to SLE (trend), whereas social support was protective. The strongest predictor was comorbid generalized anxiety, followed by loneliness, social phobia, type D personality, and panic disorder. Among behavioral risk factors, smoking was a significant predictor, and comorbid cancer among the somatic factors. Protective factors were age and social support.

When the baseline depression score was additionally entered (model 2), a similar pattern ensued. Baseline subclinical depression was one of the strongest predictors of depression at follow-up. Psychological, behavioral, and somatic factors remained significant predictors, and age and social support were still significantly protective, although the magnitude was diminished in most. Particularly, generalized anxiety, the strongest predictor in model 1, was only marginally significant.

Online Supplementary Table S3 presents findings for men, and online Supplementary Table S4 for women. In model 1, generalized anxiety, loneliness, social phobia, and type D personality were significant predictors of depression, whereas social support remained protective. Among men, smoking was a predictor. Among women, cancer was a predictor of depression, whereas age was associated with less new onset of depression only among women. After entering baseline subclinical depression scores (model 2), in men and women, only age was strongly predictive of a lower incidence of depression. For men, social support remained significant, whereas it was only marginally significant in women as a protective variable. Only in women, loneliness, social phobia, and cancer were retained as predictors; generalized anxiety was only marginally significant.

Discussion

Compared with studies focusing on recurrence of depression, few community studies have predicted incident depression in the general population (Bernardini et al., Reference Bernardini, Attademo, Cleary, Luther, Shim, Quartesan and Compton2017). Detailed analyses of men and women have been scarce. Based on a unique, comprehensive data set of a large longitudinal cohort of over 10 000 participants from the community aged 40–79 years, we determined the new onset of depression over 5 years and the combined effects of sociodemographic, psychological, behavioral, and somatic baseline characteristics. We took care to exclude participants who were depressed at baseline, who had reported a previous diagnosis of depression or who had taken antidepressants. Overall, we found a substantial rate of 4.4% of new onset of depression. Higher rates of women (Kuehner, Reference Kuehner2017), however, were only found below the age of 60 years, whereas the percentage of depression declined to similar levels for men and women above 60 years (Bogren et al., Reference Bogren, Brådvik, Holmstrand, Nöbbelin and Mattisson2017).

In univariate analyses, new onset of depression was significantly associated with sociodemographic factors (Lorant et al., Reference Lorant, Deliege, Eaton, Robert, Philippot and Ansseau2003) such as female sex, younger age, lower SES and income, and living without a partner. When stratified for sex, social disadvantage, however, was only associated with depression in men. As psychological predictors for depression, both in men and in women, we identified anxiety symptoms and a history of anxiety disorders, type D personality, life events, loneliness (Beutel et al., Reference Beutel, Klein, Brahler, Reiner, Junger, Michal, Wiltink, Wild, Munzel, Lackner and Tibubos2017b), and low social support (Green et al., Reference Green, Copeland, Dewey, Sharma, Saunders, Davidson, Sullivan and Mcwilliam1992). Among the behavioral factors, smoking was associated with depression. A higher BMI and less active sports were linked to depression only in men. Surprisingly, somatic illnesses did not seem to be useful markers for future depressive episodes. In contrast, single sociodemographic and especially psychological measures, both narrow (e.g. panic) and broad (e.g. social support) concepts, showed significant effects on future depression.

Taking intercorrelations of the predictor variables into account, multivariate logistic regression models were evaluated. In the overall model, female sex was no longer significant as a sociodemographic predictor of depression. The strongest psychological predictors of new onset of depression were generalized anxiety (Hardeveld et al., Reference Hardeveld, Spijker, De Graaf, Nolen and Beekman2010; Starr et al., Reference Starr, Stroud and Li2016), loneliness with a more than twofold risk (Beutel et al., Reference Beutel, Klein, Brahler, Reiner, Junger, Michal, Wiltink, Wild, Munzel, Lackner and Tibubos2017b), and social phobia. Consistent with the role of personality in depression (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Kotov and Bufferd2011), substantially elevated risks were also found for type D personality, along with panic disorder. In the multivariate model, life events only increased the risk for men. Among behavioral risk factors, smoking was a significant predictor. Cancer turned out to be predictive (Hartung et al., Reference Hartung, Brahler, Faller, Harter, Hinz, Johansen, Keller, Koch, Schulz, Weis and Mehnert2017) among the somatic factors in the regression model (for all and for women), which was not the case in univariate analyses. Hence, shared variance of cancer with at least one of the other predictor variables seems to reveal the effect of cancer on depression in terms of a suppressor effect. This result emphasizes the relevance of joint analyses of determinants of depression, which is in line with the vulnerability–stress model (Spijker et al., Reference Spijker, De Graaf, Bijl, Beekman, Ormel and Nolen2004) emphasizing reciprocal effects of psycho-bio-social variables and the role of the link between multimorbid somatic conditions and depression in aging (Kemp et al., Reference Kemp, Arias, Fisher, Ibáñez, Sedeño and García2017). In aging, protective factors were age and social support (Beutel et al., Reference Beutel, Brahler, Wiltink, Michal, Klein, Junger, Wild, Munzel, Blettner, Lackner, Nickels and Tibubos2017a). Unlike Cabello et al. (Reference Cabello, Miret, Caballero, Chatterji, Naidoo, Kowal, D'este and Ayuso-Mateos2017), the role of unhealthy lifestyles was evident in men, but not in women. Among men, smoking and lack of exercise were predictors, and among women, cancer was a predictor of depression. Findings regarding depression in aging are contradictory (Spangenberg et al., Reference Spangenberg, Forkmann, Brahler and Glaesmer2011). Taking into account sex, in our sample, increasing age was associated with less new onset of depression only among women.

When the baseline depression score was entered into the model, a similar pattern ensued. Consistent with the literature (Rodriguez et al., Reference Rodriguez, Nuevo, Chatterji and Ayuso-Mateos2012), baseline subclinical depression was one of the strongest predictors of new onset of depression at follow-up. Psychological, behavioral, and somatic factors remained significant predictors, and age and social support were still significantly protective, although the magnitude was diminished in most. Particularly, generalized anxiety, the strongest predictor in the previous model, was statistically not predictive any more. The strong overlap of generalized anxiety and depression (Kohlmann et al., Reference Kohlmann, Gierk, Hilbert, Brahler and Lowe2016) has been discussed in terms of shared negative affectivity, respectively, neuroticism, genetic predisposition, and common neurobiology (Goodwin, Reference Goodwin2015) leading to the recent development of transdiagnostic treatment manuals (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Sauer-Zavala, Carl, Bullis and Ellard2013). After entering baseline subclinical depression scores, age (overall and both sexes) and social support (overall and men) were still predictive of a lower probability of depression. Few other risk factors were retained: At the psychological level, type D personality, loneliness, and social phobia (overall and for women) were still predictive. At somatic level, cancer (overall and for women) remained statistically relevant as risk factor, and smoking (overall) at the behavioral level. With regard to sex differences after statistically controlling the baseline depression score, only the depression buffering factors age and social support were relevant for men. For female individuals, psychological components and cancer additionally represented risk factors. Thus, the interplay of psychological and somatic determinants seems to be more important for women.

As we had already excluded participants with PHQ-9 scores ⩾10 at baseline, we entered the baseline PHQ-9 scores into our model and additionally adjusted for any signs of depressive symptoms. This can be interpreted as a sensitivity analysis eliminating any overlap between depressive and anxiety symptoms and reduced any association between stressful sociodemographic, psychological, behavioral, and somatic factors.

Limitations

We used the PHQ-9, which is one of the most-used self-report questionnaires, to assess depression. While we inquired previous medical diagnoses of depression, respectively anxiety, we did not ascertain medical diagnoses of depression and anxiety from medical files. Given the limited time frame of 2 weeks of the PHQ-9, we cannot preclude that participants were depressed at other times during follow-up. While we used all information available to exclude subjects who had been depressed, previously, an unknown proportion of participants included may actually have fulfilled the criteria of depression in the past without proper medical diagnosis. While we covered a substantial numbers of predictors from the literature, other predictors such as family history of depression were not assessed.

Conclusion

Following the vulnerability–stress model (Spijker et al., Reference Spijker, De Graaf, Bijl, Beekman, Ormel and Nolen2004), a comprehensive model was tested to predict new onset of depression in an aging population, including sociodemographic, psychological, behavioral (Cabello et al., Reference Cabello, Miret, Caballero, Chatterji, Naidoo, Kowal, D'este and Ayuso-Mateos2017), and somatic factors (Wiltink et al., Reference Wiltink, Beutel, Till, Ojeda, Wild, Munzel, Blankenberg and Michal2011; Hartung et al., Reference Hartung, Brahler, Faller, Harter, Hinz, Johansen, Keller, Koch, Schulz, Weis and Mehnert2017). Benefits of our study refer to the large sample of participants over a wide age range of middle and old age enabling us to identify a comprehensive set of predictors. Findings alert us to the complex interplay of factors and will be helpful to identify subjects at risk for developing depression. They underline the need to take signs of the major kinds of anxiety disorders (generalized, social anxiety, panic disorder) seriously as potential precursors of depression. They also underscore the role of social factors in addition to type D personality, with loneliness as a negative and social support as a positive factor. Among somatic disorders, cancer appears to cause new onset of depression in the context of these additional risk factors. Following gender-sensitive clinical research, which is a first step toward tailored treatment, we also analyzed data separately for men and women. Differential preventive efforts are likely indicated, e.g. treating smoking in men, and giving psychosocial support to women with cancer. Based on a recent trial with acceptance and commitment therapy, smoking cessation was associated with a decline of anxiety and depression in male smokers (Davoudi et al., Reference Davoudi, Omidi, Sehat and Sepehrmanesh2017). Findings that exercising has a small, but consistent positive effect on depression may need to be reconsidered separately for men and for women (Cooney et al., Reference Cooney, Dwan, Greig, Lawlor, Rimer, Waugh, Mcmurdo and Mead2013). Findings of our study have predictive validity due to the longitudinal study design in a large community sample. Future analyses might take a closer look at potential indicators of social disadvantage (e.g. employed single mothers, low-income participants) and specific life events in order to gain a better understanding of why trajectories of depression differ between women and men in midlife, but not in old age.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718001848.

Acknowledgement

We express our gratitude to the study participants and staff of the Gutenberg Health Study.

Funding

The Gutenberg Health Study is funded through the government of Rhineland-Palatinate („Stiftung Rheinland-Pfalz für Innovation“, contract AZ 961-386261/733), the research programs “Wissen schafft Zukunft” and “Center for Translational Vascular Biology (CTVB)” of the Johannes Gutenberg-University of Mainz, and its contract with Boehringer Ingelheim and PHILIPS Medical Systems, including an unrestricted grant for the Gutenberg Health Study. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.