The late 3rd millennium bc saw the final flowering of elaborate flint knapping in Britain. It is a period characterised by the development of a variety of very skilled flint-working techniques, resulting in a large corpus of fine, pressure-flaked, and punched objects being deposited in a variety of contexts, most famously alongside rich single burials. Of the flint objects produced at this time, flint daggers are among the most eye-catching while also being among the least well understood. Since Grimes’ (Reference Grimes1932) seminal typochronology, little attention has been paid to lithic daggers in Britain, except to note additions to his corpus. Summary papers have dealt with smaller regions within the distribution area that were poorly served by Grimes’s work, such as Wales (Green et al. Reference Green, Houlder and Keeley1982) and northern Britain/Scotland (Saville Reference Saville2012). Additionally, Needham (Reference Needham2005; Reference Needhamforthcoming) has incorporated the small minority of British flint daggers from burial contexts into his discussions of Beaker society and technology.

Flint daggers are a well-known and closely studied object type in continental Europe with major production centres known in Italy (Mottes Reference Mottes2001), Switzerland (Honegger Reference Honegger2002; Honegger & de Montmollin Reference Honegger and de Montmollin2010), France (Delcourt-Vlaeminck Reference Delcourt-Vlaeminck2004; Ihuel Reference Ihuel2004; Mallet Reference Mallet1992), and the Nordic regions (Apel Reference Apel2001; Frieman Reference Frieman2012c; Lomborg Reference Lomborg1973; Olausson Reference Olausson2000). They are frequently associated with ideas about the importance of masculine or warrior identities, increasing social stratification and the significance of metal tools and metalworking to societies just on the cusp of becoming metal-using (Earle Reference Earle2004; Sarauw Reference Sarauw2007; Reference Sarauw2008; Steiniger Reference Steiniger2010; Vandkilde Reference Vandkilde1996). Yet, their relationship to metal, and specifically the long-held belief that they are universally copies of metal has recently been questioned (Frieman Reference Frieman2012a; Reference Frieman2012c). Over the last several decades, this increasingly nuanced discussion of flint daggers, flint knapping technologies, and the significance of both to expanding networks of communication and exchange in 3rd and 2nd millennia bc Europe has been carried out with little to no input from Britain.

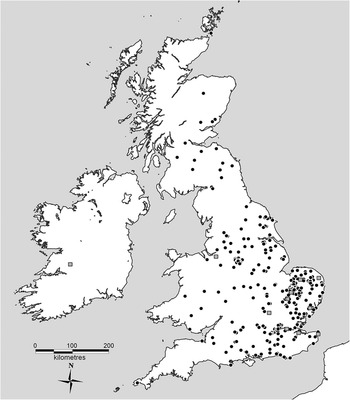

This paper will set out to redress this imbalance by both presenting an updated summary of the various types of British flint daggers, their production sequences and deposition contexts, and elaborating an interpretative framework which links them to developments within the British Beaker system as well as to the wider flint-dagger-using European continent. Flint daggers have been recovered from Kent to Cornwall and north to Orkney, but they are most densely distributed in south-east England, particularly northern East Anglia (Fig. 1). These daggers are not numerous – the present survey has recorded just under 400 (Appendix)Footnote 1 using relatively liberal and inclusive standards, meaning that at least some are probably erroneously included – nor were they in circulation for a long period of time. When they have find contexts with datable associations, these are almost always linked to a set of Beaker related materials in circulation in the last quarter of the 3rd millennium bc, a date supported by the handful of radiocarbon dates for contexts with flint daggers which also cluster tightly in the period between 2250 and 2000 cal bc (Harding & Healy Reference Harding and Healy2007; Levitan & Smart Reference Levitan and Smart1989; Needham Reference Needham2005; Reference Needham2012; Reference Needhamforthcoming; Roberts & Prudhoe Reference Roberts and Prudhoe2005). Yet, they were clearly time-consuming to make and valued enough to be deposited, for a brief time at least, in some of the richest burial contexts yet uncovered of their era. This paper will propose that the value accorded to such a novel and short-lived artefact type can be linked to the increasing regionalisation and concomitant significance accorded to local ancestral identities in Britain after 2250 cal bc. Their role in the wider sphere of flint dagger production and circulation will be explored in order to demonstrate that, while British flint daggers were definitely produced in Britain, they not only derived from flint daggers circulating on the continent, but were produced as part of an effort to claim affiliation for some British communities with this European dagger bearing network. Although metal still dominates our discourse about the late 3rd and early 2nd millennia bc in Britain, it is argued that the lithic evidence, and particularly the British flint daggers, give us a special window into social relations, identity formation and exchange and reconnects the British Beaker period to its larger north-west European context.

Fig. 1 The distribution of flint daggers found in Britain and Ireland. Black circles are British flint daggers, grey squares are hilted Scandinavian flint daggers

CATEGORISING BRITISH FLINT DAGGERS

A cursory examination of Grimes’s (Reference Grimes1932) typology and discussion makes clear that the categories he used to identify specific types of flint daggers are rather broad and do not easily lend themselves to archaeological analysis. Furthermore, examination of museum collections and the subsequent body of literature on flint daggers highlights that many of the objects included in previous publications were definitively not daggers (Table 1). Grimes’s catalogue evidently rested in large part on publications by, and communication with, his contemporaries, leading to the inclusion of, for example, many small flint fragments – bifacially worked but typologically indeterminate – collected by E.C. Curwen in East Sussex and rather optimistically published as flint daggers (Curwen Reference Curwen1932; Reference Curwen1941).

Table 1 Flint Objects Included by Grimes in his Catalogue but Which Were Misidentified as Flint Daggers

Unfortunately this confusion about how to identify a flint dagger found in a British context continues. Museum collections around Britain have numerous examples of plano-convex knives, scrapers, fragments of axes and other edged tools, some bifacially worked, some only worked on one face, all recorded as ‘flint daggers’. Therefore, among the primary goals of the present survey was to develop a better system for recognising and identifying flint daggers found in British contexts than that provided by Grimes.

The criteria below are somewhat arbitrary, but were decided upon based, first, on the need to delimit the category dagger in meaningful ways; second, on our improved (although still significantly fragmentary) understanding of later Neolithic and Bronze Age British flintworking; and, finally, on a preliminary examination of the British Museum’s collection of flint tools recorded in their own catalogue or by Grimes as ‘flint daggers’.

Items included in the catalogue as credible flint daggers:

-

● Are fully bifacially knapped;

-

● Are largely flat in profile, lacking a tendency towards marked plano-convexity or full convexity in profile;

-

● Are at least 100 mm long when complete and unresharpened – traces of resharpening or breakage have allowed for the inclusion of smaller pieces in the catalogue;

-

● Have a distinct double-edged cutting part with a reasonably pointed tip and a distinct tang or hafting end with several different possible base morphologies;

-

● May belong to recognised types of flint daggers better known in other parts of Europe, specifically the Nordic area.

Formal groupings

Unfortunately, there are few clear typological divisions within the assemblage of objects identified through the application of the criteria listed above. The majority of the daggers from British contexts are quite uniform in production technique and measurements. Nevertheless, three obviously distinct flint dagger types can be distinguished: hilted Scandinavian daggers, short-tanged British daggers, and long-tanged British daggers, of which the latter type can be divided into four morphological classes (Fig. 2). These classes lie on a continuum, they are not distinct types in the classical sense and they overlap considerably, which is unsurprising given the lack of evidence for chronological development in the dagger form within Britain (contra Grimes Reference Grimes1932). There are few metrical distinctions between them, so the classification of a given object as being of one of these forms relies on three primary observations: the morphology of the tang, specifically its edges; the shape of the blade, particularly as regards the point of maximum width; and the transition between tang and blade (referred to as the ‘junction’). Based on the prevalence of notches, binding traces, and edge wear (see below), all British daggers are assumed to have been hafted in some sort of organic handle, whether that comprised an actual wood, bone, or antler handle into which the tang was inserted or a simple leather or fibre wrapping probably varied. That said, many of the larger daggers had tangs which could have been held in the hand unaltered as hilts, so further research is necessary to determine whether a distinction ought to be made between long-tanged and hilted British flint daggers.

Fig. 2 Morphological schema of flint daggers found in British contexts: A) hilted Scandinavian dagger; B) short-tanged British dagger; C) Class 1 long-tanged British dagger; D) Class 2 long-tanged British dagger; E) Class 3 long-tanged British dagger; F) Class 4 long-tanged British dagger

It is worth noting that these classifications are based on evidence from only about 170 of the nearly 400 British flint daggers as these were the only ones that were both complete enough and accessible for morphological analysis.

HILTED SCANDINAVIAN DAGGERS

These 14 pieces are distinct from the rest of the assemblage of daggers found in Britain and Ireland (Fig. 2: A) in three clear ways: their morphology, their age, and their find contexts. First, their morphology reflects production techniques consistent with the manufacture of flint daggers in the Nordic region. They fit neatly into the established Scandinavian typology as type VI daggers – although two fishtail (type IV or V) examples are present (Table 2) (Apel Reference Apel2001; Lomborg Reference Lomborg1973). Second, based on this typological information, they are significantly younger than the majority of the flint daggers from British contexts. Based on stratigraphic observations and radiocarbon dating of Scandinavian finds, Type IV and V daggers date to no earlier than 1950 cal bc and the smaller type VI daggers are generally believed to begin circulating c. 1700 cal bc (Lomborg Reference Lomborg1973; Vandkilde Reference Vandkilde1996; Vandkilde et al. Reference Vandkilde, Rahbek and Rasmussen1996). Finally, the hilted Scandinavian daggers are never found in burial assemblages. Seven were single finds (three from wet contexts), five lack contextual information, one was found with two Scandinavian square-butted axes on a cliff in Ramsgate, Kent (Cat. No. 288) as an apparent hoard deposit, and one was associated with ceramic material and may have derived from a settlement or burial, but the context is unclear (Hicks Reference Hicks1878; Thomas Reference Thomas1956). They do appear to have a somewhat regular distribution pattern, with all but one being found in south-east England; although it is worth highlighting that the only definite flint dagger from an Irish context was a Scandinavian type VI dagger found in a dried up lake in Scariff, Co. Clare (393) (Clark Reference Clark1932b; Corcoran Reference Corcoran1964; Day Reference Day1895; Macalister Reference Macalister1921).

Table 2 Hilted Scandinavian Flint Daggers Found In British Contexts

Two other flint daggers from British contexts are morphologically closer to the hilted Scandinavian daggers than to any of the more frequently recovered British flint dagger morphologies, but both are questionable. The small, rough dagger from Merthyr Mawr Warren, Bridgend (151) has a lanceolate blade and a thick, parallel-edged hilt; but its hilt is also predominantly chalky cortex and only roughly shaped rather than carefully knapped. By contrast, the very fine piece from Peasmarsh, Godalming, Surrey (346) has a carefully formed lanceolate blade and appears to have a somewhat thicker, parallel-edged hilt, but post-depositional breakage means the butt end is missing, preventing it being concretely identified as Scandinavian in form.

SHORT-TANGED DAGGERS

Nearly all of the British daggers for which the information is available have a hafting part which makes up 46–52% of the length. However, there are seven pieces (Table 3) which have a tang that makes up less than one-third of the length of the whole piece (Fig. 2: B).Footnote 2 These short-tanged daggers, unlike the rest of the flint dagger assemblage, would be difficult to wield holding only the tang in one’s hand. Also included in this group, on purely morphological grounds, is a small and rather crudely made piece thought to be from Norfolk (153) which has a short hafting end with large notches that would make it equally unsuitable for holding in the hand.

Table 3 Short-Tanged British Flint Daggers

These short-tanged daggers tend to be rather short; the average length of these pieces is 122 mm, an average blade width of 44 mm and an average tang width of 38 mm. Two-thirds show evidence of resharpening. Yet, morphologically, they are very unalike. They range from the thin triangular blade and blocky trapezoidal tang of the piece from the UK or Ireland in the British Museum collection (1) to a delicately leaf-shaped artefact from Deeside, Aberdeenshire (12) which was only included in the catalogue because it met the criteria listed above in that it had a double-edged blade at one end and hafting traces at the other. A potential parallel for short-tanged daggers can be found in the clearly Early Neolithic class of Irish artefacts termed javelins (Woodman et al. Reference Woodman, Finlay and Anderson2006, 144–5).Footnote 3 However, the Deeside example finds its closest parallels in the foliate knives discussed below. This group also includes the extremely anomalous artefact from Stofield, Edgerston, Scottish Borders (23). This piece is unique in the catalogue in that it was knapped from what appears to be a local quartzite and, most likely due to the unsuitable raw material, is extremely crudely made with a roughly shaped blade end and a tang which is both quite narrow and asymmetrical.Footnote 4 Short-tanged daggers have no consistent find context as five of the eight lack contextual information while one was dredged from the River Thames near Battersea and two others derive from funerary assemblages, including a small dagger from a burial under a barrow at Herdsman’s Hill, near Peterborough, Cambridgeshire (243) (Leeds Reference Leeds1912) which was clearly made from the same block of flint as the Class 2 long-tanged flint dagger it accompanied (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3 The two flint daggers found with a Beaker burial at Herdsman’s Hill, Newark, Peterborough, Cambridgeshire (AN1956.986 & AN1956.986.a, reproduced with permission from the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford). They are obviously made from the same nodule of flint. A) Currently classified as a short-tanged flint dagger, but might perhaps be better thought of as a foliate knife once better typological criteria are available. B) Class 2 flint dagger

LONG-TANGED BRITISH DAGGERS

Class 1

Class 1 flint daggers (Fig. 2: C) are the smallest of the British forms and have the most obvious distinction between blade and tang. The 26 Class 1 flint daggers typically have narrow, leaf-shaped or triangular blades and somewhat tapered tang edges. In general, blade and tang are more or less the same length. In all but four cases for which the information is available, the base is round or flat. They are rather slight and somewhat stocky with an average length of 139 mm and an average maximum width of 49 mm. Their widest point is typically on the blade end, very close to the junction of blade and tang. Over 90% of Class 1 daggers show evidence of resharpening. Only around one-third are notched, in distinction to Class 2 and 3 daggers. Of these, the notches are generally placed at the junction of blade and tang and there is a considerable diminution of tang width just past the notches. Their distribution pattern shows two regional centres of deposition: northern East Anglia and the north-west of England. There is no clear deposition pattern. Half were single finds (including five retrieved from riverine contexts) and three were found in burials, among which is the well-known example from barrow 6 at West Cotton, Northamptonshire (132) (Grace Reference Grace1990; Harding & Healy Reference Harding and Healy2007).

Class 2

Class 2 flint daggers (Fig. 2: D), with Class 3 daggers, are the largest of the British long-tanged types with an average length of 154 mm, average maximum blade width of 59 mm and maximum tang width of 51 mm. The 24 Class 2 daggers are characterised by a broad, leaf-shaped blade with its widest point about four-fifths of the distance from the blade tip to the junction of blade and tang. There is sometimes a clear shoulder between the blade and tang; but, even when the blade has been resharpened to the point that this shoulder is no longer present, a change of angle is generally apparent, making the blade part visually distinct from the hafting part. In some cases, due to resharpening, the blade edges are nearly parallel between the widest point and the junction. Roughly 85% of Class 2 flint daggers show evidence of resharpening. The tang edges are all tapered with a tendency for them to be very tapered and over half have butts which are largely flat, while a further third have rounded butts with only three daggers of this class having largely pointed butts. The blade is often slightly longer than the tang. EighteenFootnote 5 of the 24 daggers in this class have notches on their edges, and there is frequently a considerable diminution of tang width just past the notches. They are the only class of British dagger where notched edges predominate, and most of the notched examples have more than one pair of notches along their edges. There is a strong tendency for these daggers to be produced from very glassy flint with a shiny, rather than matte surface texture (18 of 21 for which the information was available). They are only found in England and Wales, with a notable focus of distribution in East Anglia, Lincolnshire, and the East Riding of Yorkshire. Again, there is no clear pattern in find context with 11 daggers listed as single finds (six of these from the Thames in Greater London and Surrey) and five coming from burials. Worth noting is that this class includes some of the best known and most eye-catching of the British flint daggers, including the well-known example from Arbor Low, Youlgreave, Derbyshire (114) (Evans Reference Evans1897, fig. 267; Jewitt Reference Jewitt1870, 155; Thurnam Reference Thurnam1871, 413), as well as the daggers accompanying the funerary deposits in Ty Ddu, Ystradfellte, Powys (149) (Cantrill Reference Cantrill1898; Green et al. Reference Green, Houlder and Keeley1982; Grimes Reference Grimes1951), Garton Slack B 152, East Riding of Yorkshire (41) (Mortimer Reference Mortimer1905) and Herdsman’s Hill, near Peterborough, Cambridgeshire (242) (Leeds Reference Leeds1912) (Fig. 3).

Class 3

Class 3 flint daggers (Fig. 2: E) are by far the most numerous, with 63 recorded in the current study. They tend to be about the same length as the Class 2 daggers, on average 154 mm, but narrower with an average maximum blade width of 54 mm and average maximum tang width of 48 mm. The blade and tang are, on average, more or less the same length. The Class 3 daggers are characterised by a leaf-shaped blade with the widest point about four-fifths of the distance from blade tip to the junction of blade and hafting part. About 80% of handled Class 3 daggers show evidence of resharpening. The key distinction between these and the Class 2 daggers is that the Class 3 daggers tend to be narrower and lack a shoulder or visible break in angle at the junction, except where notches are present; but even the roughly 40% of Class 3 daggers with notches have a smooth transition between blade and tang (eg, Fig. 4, below). Like the Class 2 daggers, their tang edges are all either somewhat or very tapered, but they have distinctly different butt morphologies. About 30% have largely flat butts, a further 30% have largely rounded butts, and roughly 40% have largely pointed butts. By contrast, both Class 1 and 2 flint daggers have flattened butt ends over 50% of the time. Class 3 flint daggers are widely distributed across Britain, with a large cluster in northern East Anglia and less dense clusters in Wessex and Yorkshire. Notably, they are the only type of long-tanged dagger found in south-east England. Like the other classes of British dagger, when their find context is known, Class 3 daggers are largely single finds, many from wet locations, including the River Thames (seven examples) and bogs in several parts of England and Scotland (five). Twice as many Class 3 daggers are found in burial contexts as Class 1 and 2 combined; but, proportionally, only 25% (16) come from funerary contexts. Funerary daggers of this class include a cluster of rich burials from Yorkshire as well as the widely published flint dagger finds from Durrington Walls (380) (Cunnington et al. Reference Cunnington, Goddard and Cunnington1896, nos 85b–e) and Amesbury G54, Wiltshire (381) (Hoare Reference Hoare1812, 163, Pl. 17), barrow 17 at Lambourne ‘seven barrows’, Berkshire (339) (Evans Reference Evans1897, 321) and barrow 1 at Irthlingborough, Northamptonshire (131) (Davis & Payne Reference Davis and Payne1993; Grace Reference Grace1990; Harding & Healy Reference Harding and Healy2007).

Fig. 4 The Class 4 flint dagger recovered from a Beaker burial at Shorncote, Somerford Keynes, Gloucestershire – arrows indicate binding traces. A large ground and polished facet is visible along one tang edge near the base (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Class 4

Class 4 flint daggers (Fig. 2: F), of which 38 were recorded in the present study, are both the easiest to describe and the hardest to delineate as separate from other artefact types. These daggers are leaf-shaped with no clear break in angle or shoulder at the junction. They are typically smaller than most of the long-tanged daggers with an average length of 140 mm and slighter, having an average maximum blade width of 47 mm and tang width of 44 mm. The point of maximum width is quite near the junction of blade and tang, and the blade is usually slightly longer than the hafting part. About four-fifths of Class 4 daggers show traces of resharpening. Like the Class 2 and 3 daggers, their tang edges are all somewhat or very tapered, but their butt ends are almost universally rounded (44%, 14 examples) or pointed (41%, 13) with only five having largely flat butt ends. Only two Class 4 daggers have notches along their edges, and both are morphologically atypical. The vast majority of Class 4 daggers were made from shiny, smooth flints; but they are typically less translucent than the other classes, largely due to patination. This class of flint dagger is widely distributed across Britain, with a slightly denser distribution in East Anglia and Greater London, mirroring the distribution of all British flint daggers. Where a find context is known, 21, the vast majority, come from non-funerary contexts, with more or less equal numbers having been recovered from dry and wet locales (including five from the Thames and two from the Little Ouse in Norfolk). Of the two examples from funerary sites, the piece found under cairn 2 on Biggar Common, South Lanarkshire (20) (Johnston Reference Johnston1997) is somewhat ambiguous as it was without direct funerary associations.

MAKING AND USING BRITISH FLINT DAGGERS

That several distinct British flint dagger forms exist suggests that there was some shared idea of what the finished objects should look like and, concomitantly, how they should be made. In general these flint daggers are flake tools made from relatively large nodules of flint. A variety of sources of high quality flint nodules are known from the British Isles, and flint mining was carried out in British contexts from early 4th millennium bc (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011); but little evidence is available at the moment for Beaker-associated flint extraction practices. Currently, little can be said about the choice of specific raw material but some patterns are clear. The raw materials chosen were, by and large, of high quality with few inclusions. Daggers tend to be made from smooth, glossy flints, most apparently from chalk deposits, and those whose provenence has been identified as the chalklands of southern England have been found across Britain from Wales (Green et al. Reference Green, Houlder and Keeley1982) to Northamptonshire (Ballin Reference Ballin2011a, 522). Although flint mining took place in southern England during the Neolithic, there is no evidence for mining subsequent to this period; however, Gardiner (Reference Gardiner1990, Reference Gardiner2008) has noted that surface deposits were abundant and discarded flint material was easily accessible in upper mine fills and was likely exploited by people after the mines fell out of use. She further suggests that this region might have been a centre of specialist flintworking during the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age (Gardiner Reference Gardiner2008), a situation which would lead naturally to the wide distribution of finely made flint objects, such as flint daggers. Similarly, daggers made of characteristic Yorkshire flint with numerous cherty inclusions have been found as distant as Nunraw, Haddington, East Lothian (17), Hitcham, Burnham, Buckinghamshire (144), and Kingston-on-Thames, Greater London (333).

While the large number of flint daggers and fragments in northern East Anglia and the presence of abundant local raw materials of high quality – although quite possibly excluding the Grimes Graves flint mines (Healy Reference Healy2012) – suggests that centres of flint dagger production and use existed in Britain in the Early Bronze Age (cf. Edmonds Reference Edmonds1995, 110), no manufacture site or workshop has yet been discovered. It is unclear whether flint blanks – for daggers or other tools – were circulating around Britain, whether only roughed out or finished artefacts travelled, or whether the distribution pattern reflects a mix of exchanged finished objects and daggers locally produced from flint blanks or local raw materials. Indeed, the anomalous quartzite dagger from Stofield, Edgerston, Scottish Borders (23) demonstrates that the production of lithic daggers was being carried out far from centres of high quality flint and, when necessary or desired, far from ideal raw materials were chosen for their production. Additionally, the well-known flint dagger from Ystradfellte (149) and the smaller, rougher piece from Merthyr Mawr Warren, Bridgend (151), both of which are assumed to have been imported to Wales from regions where the raw materials from which they were made are abundant, have tangs which are largely chalky cortex rather than flint or chert, a strange choice to make if the daggers themselves were produced in areas with widely available, large flint nodules.

Despite the paucity of identifiable preformsFootnote 6 for flint dagger production and of scholarly interest in their technology and morphology, there is a generally agreed production schema for these artefacts. While they are mostly lenticular and flat, most examples show a slight plano-convexity in profile, with one face being slightly more rounded while the other is slightly flatter. This profile presumably derives from the use of large flakes as dagger blanks, with the slightly more rounded face being the dorsal surface of the flake (cf. Saville Reference Saville2012, 1–2). The blanks were thinned through shallow invasive flaking with a soft hammer, requiring the establishment of a good platform, with the intent, it appears, to remove the entire original flake surface which is only visible in a few isolated examples (eg, the leaf-shaped dagger from Higham Ferrers, Northamptonshire (133): Humble Reference Humble2011; cf. Field Reference Field1983). Elsewhere in northern Europe, flint daggers produced on flakes have been demonstrated to go through a phase of grinding to thin the blank and create an even surface for elaborate bifacial retouch (Callahan Reference Callahan2006; Nunn Reference Nunn2006a; Reference Nunn2006b); but there is limited evidence for a grinding phase in the production of British flint daggers. That said, the flint dagger from Wick Barrow, Stogursey, Somerset (389), three daggers from the Thames in Greater London (296, 322, & 328), three daggers from bogs west of Glastonbury, Somerset (386, 387, & 388), and a leaf-shaped probable dagger from Cote Hill Farm, West Lindsey, Lincolnshire (84) all have small facets of striated polish irregularly positioned near the centre of the blade and tang faces which appears to derive from an early phase in the manufacture process, suggesting that some flint dagger blanks were ground, but subsequent flaking removed the traces. These traces might be evidence of the local manufacture of the four examples from Somerset listed above. After thinning, the blade and tang edges were further shaped through pressure flaking.

It is clear that the knappers who produced these pieces intended them to have certain specific traits, which were largely maintained through cycles of use and resharpening. As noted above, flint daggers are nearly universally flat and lenticular. Of the 13 examples which were recorded as being somewhat or markedly plano-convex in their final form, half are rather problematic: one is a Scandinavian (302), two are typologically ambiguous (74 & 153), one is fragmentary (163), and one is a possible fake, according to the Norfolk county HER records (202). The surface treatment of British flint daggers is equally uniform, but not elaborate. Only 14 daggers have been found with parallel or sub-parallel retouch on both faces, common on flake and blade flint daggers on the continent; another 15 exhibit areas of parallel or sub-parallel retouch on only one face. Several examples of unusual surface treatment exist in the form of the partially ground and polished blade faces of the daggers from Ystradfellte (149) (Green et al. Reference Green, Houlder and Keeley1982), Gooderstone Common, Breckland, Norfolk (179), the Little Ouse at Wilton Bridge, Hockwold, Norfolk (203).

Cortex remains present on a number of flint daggers. Of the 154 flint daggers for which the information is available, 46 (about 30%) have areas of cortex remaining on the surface. For 37 of these, the area of cortex is localised on or around the base of the dagger, only seven pieces have cortex on the blade, and three of those also have areas of cortex present on the tang or base. In most cases, the area of cortex on or near the base has also been carefully ground and polished. This pattern is significant as it can also be found among flint axes and daggers in circulation on the continent where it is generally understood as a conscious choice made by skilled knappers and indicating that a large flake struck across the full width of a large nodule has been used to make the finished object (Frieman Reference Frieman2012a; Reference Frieman2013a; Rudebeck Reference Rudebeck1998). While not every flint dagger with cortex on it is particularly refined in manufacture, the extremely fine example from a Beaker burial at Shorncote, Somerford Keynes, Gloucestershire (147), which has a small area of cortex at both the base and the tip, might be an example of the sort of technical showmanship noted elsewhere in Europe.

To haft and to hold

Historically, there has been some question about whether the British flint daggers were, in fact, daggers (ie, tools hafted to be held in the hand) or spearheads (ie, tools hafted on a long pole). Many of the older museum records still list these pieces as spearheads, as do many earlier papers on dagger finds, leading to some of the typological confusion discussed above. While no hafted examples have been uncovered, excavation data, such as there is, and traces on the daggers themselves, support their identification as hand-held tools. That said, in one case a flint dagger in a Beaker burial at Thorpe Hall Brickfield, Southchurch, Essex (284) was found adjacent to a darkened area of soil interpreted as a javelin shaft (Pollitt Reference Pollitt1930); however, the ultimate placement of the dagger itself, near the hands of a crouched inhumation, perhaps undermines this hypothesis. Nevertheless, a placement in or near the hands was only recorded in two other examples (Table 4).

Table 4 Flint Daggers Found Associated With Human Remains

Physical traces of hafting are visible on numerous daggers, most famously in the form of notches on tang edges which distinguish the British daggers from their continental parallels. Yet, the notches are neither present on the majority of daggers, nor are they uniform in their placement or production. About one in three have notches on their tang edges, but these can vary from deep indents pressure flaked from both faces to shallow depressions roughly punched from a single face. Most of the time, notches are present in even numbers with matching pairs on the two tang edges, but about one in four daggers has at least one unpaired notch. It is unclear whether these odd notches were created during the original knapping sequence, or whether they were, in fact, a later addition, perhaps to secure a new or differently designed haft. In some cases, edge indents previously identified as notches have proven, on closer examination, to be the result of post-depositional damage; and it seems possible that, were a dagger damaged in such a way while still in use, the damage might have been reworked into a new edge notch. While the most heavily notched daggers have as many as eight or nine notches on each edge, the majority have just one or two, usually placed near the junction of blade and tang.

Nearly all the flint daggers observed had tang edges which were obviously somewhat blunted and rounded, a pattern of edge wear which has elsewhere been identified as being consistent with having been tightly bound, likely with an organic material (Frieman Reference Frieman2012a; Reference Frieman2012c). Green et al. (Reference Green, Houlder and Keeley1982) noted a small area of dark residue, no longer visible macroscopically, on the hafting end of the leaf-shaped dagger from Ffair Rhos, Tregaron, Ceredigion (150) which proved, on microscopic analysis, to include very fine, organic, cylindrical fibres thought to have been part of the hafting. A similar dark residue or resin is visible on the tang edges of the dagger found at Brandon Creek, Southery, Norfolk (206) and on the tang faces of the dagger from Trengwainton House, Madron, Cornwall (392). Moreover, the flint dagger from Ystradfellte (149) famously bears traces of haft binding in the form of criss-crossing brownish streaks or stains on the faces between the edge notches at the junction of blade and tang. (Cantrill Reference Cantrill1898; Green et al. Reference Green, Houlder and Keeley1982, 497 & fig. 6). Very similar patterns of discolouration are present on a handful of other flint daggers,Footnote 7 suggesting that this was not an unusual way of securing handle binding. It seems likely that microscopic analysis would reveal more daggers with similar binding traces, particularly if it were directed at the heavily patinated (and, thus, rather porous) chalk flint daggers (Fig. 4). A further potential source of information on their hafting comes in the form of small highly polished facets found, generally along a single edge, at the base of about one in six of the flint daggers examined (Fig. 4). In some cases, these facets give the butt end a sharply pointed shape, but not in all cases. The vast majority are found on Class 2 and 3 flint daggers. It is possible that this facet represents a smoothing of the base edges to fit a pre-made haft of some sort; although, equally, it could be a technological signifier like the presence of cortex on a dagger’s base.

Several examples of hafted flint daggers have been found in various parts of Europe. The most famous is, of course, the small lanceolate flint dagger found in a bog in Wiepenkathen, Kreis Stade, Niedersachsen (Germany) which had its hilt wrapped in a woven cloth of wool and horse hair before being inserted into a wooden handle and its blade inserted into a leather sheath which had two long leather straps, perhaps for attaching it to a belt (Cassau Reference Cassau1935). Another well-known example of a flint blade hafted as a dagger is the 64 mm long blade which formed part of the equipment of the Similaun Man found preserved in the Alps and which was found still inserted into a 89 mm long, rectangular handle of ash wood to which it was bound by a long sinew woven around the tang at a pair of notches (Spindler Reference Spindler1994, 101–2). Another style of hafting is known from Charavine, Isére (France) where a flint dagger was recovered with an ash haft (with a large round pommel) still attached to one face with birch tar pitch and wrapped in a fibrous cord to hold the hafting together (Bocquet Reference Bocquet1974; Mallet Reference Mallet1992). The presence of notches and criss-cross patterns of binding suggests that the latter two models might be more credible hafting styles for British flint daggers. The long-tanged British daggers were probably too large in proportion to be inserted into split handles, such as was found in the Alps, but it is possible that they were attached to a wooden plate like the Charavine dagger and secured with resin and cord.

Based on this evidence for tightly bound hafts, a good grip must have been necessary when using British flint daggers. While a number of authors have suggested that some of the finest of the found in British contexts were produced solely for deposition (cf. Brooks Reference Brooks2005), most British examples do show evidence of resharpening and frequent handling. Of the c. 170 daggers which were either observed, or for which adequate imagery was available, 126 show definite or probable signs of resharpening. That said, no flint dagger appears to have reached the point where further resharpening would have been impossible or futile. Microscopic analyses by Green et al. (Reference Green, Houlder and Keeley1982) and Grace (Reference Grace1990) indicate that at least two British flint daggers were regularly placed into and pulled out of leather sheaths. This pattern is consistent with work carried out on Dutch flint daggers by Annelou van Gijn (Reference van Gijn2010a; Reference van Gijn2010b) who suggested that they may have been stored in protective sheaths before being removed to be publicly brandished as symbols of wealth, status, or identity. Of the flint daggers directly observed in the course of the present research, the blade faces of 47 show a distinct pattern of macroscopically visible wear, with raised arrises at the centre of the blade near the junction being somewhat rounded to polished. While this polish could be the result of rubbing against a leather sheath, the fact that it is primarily located at the junction of blade and tang suggests it is a result of distinctive gestures of handling and use. A similar pattern was observed on Scandinavian fishtail flint daggers and suggested to result from a ‘chef’s knife’ grip high up on the hafted end with fingers extending onto the blade for control of fine movements (Frieman Reference Frieman2012c, 69).

This wear pattern, combined with the evidence for resharpening and, potentially, for rehafting, supports the idea that, while some daggers may have been produced for display or deposition, the majority also served some sort of more physical function and, perhaps, remained in circulation for a period of time after their production. That they may have been carefully protected in leather sheaths from which they were regularly removed indicates that their integrity was valued and carefully guarded. Some may even have remained in circulation after major breakage.

FLINT DAGGER DEPOSITION AND ASSOCIATIONS

In much of northern Europe, flint daggers are traditionally discussed as quintessential funerary objects, particularly associated with the Beaker burial rite; and Britain is no exception (cf. Needham Reference Needham2005; Reference Needhamforthcoming). However, while flint daggers are certainly found in funerary contexts in Britain, their find locations are certainly more heterogeneous than that. Clearly, the identification of find locations is rendered more difficult by the large numbers of single finds or daggers for which no find location is available. Of the 393 examples catalogued here, 155 have no known context whatsoever. A further 80 are simply single finds with no further information except, in some cases, the year of recovery. Of the 158 daggers remaining, 56 are single finds with some information about their recovery. This information might be as limited as a note that the object was recovered during fieldwalking or from the surface of a field in the South Downs, but at least some guarantee is available that these 56 daggers definitely were found more or less where their HER or museum catalogue records state.

However, in examining the available HER records, it becomes clear that a number of these so-called single finds were, in fact, recovered from what appear to be occupation or settlement contexts, in proximity to ritual sites or, potentially, from disturbed burials (Table 5). For example, three fragmented examples from Chichester College Brinsbury Campus, Pulborough, West Sussex (355, 356, & 357) formed part of a large lithic scatter recovered in systematic fieldwalking which includes over 70 barbed-and-tanged arrowheads recovered from a single field. Also of interest is the example from Little Oulsham, Feltwell, Norfolk (193) which has been suggested to derive from a flint processing area, although any direct link to contemporary knapping practices is speculative at best. This latter case might merit further investigation as dagger production sites are still unknown. Moreover, two examples from Norfolk (195 & 204) were found on burnt mounds, in one case with pot boilers, a quern, and flint tools of many periods, including barbed-and-tanged arrowheads. Burnt mounds – controversial sites apparently for heating water as part of cooking, brewing, steam production, or other industrial activities (eg, Ripper et al. 2012, 199–200) – are typically dated to the Middle or Late Bronze Age but, in Norfolk, a number of burnt mounds have yielded Beaker dates and material (eg, Bates & Wiltshire Reference Bates and Wiltshire1992; Crowson Reference Crowson2004), so an association between flint daggers and other East Anglian burnt mounds would not be surprising. Potential ritual deposits of flint daggers – sometimes singly, sometimes with other objects – include both the deposition of flint daggers in proximity to more or less contemporary monuments, such as Arbor Low henge and stone circle (114), as well as examples apparently deposited with flint or stone axes. One of these finds, the flint dagger and two flint axes recovered from Ramsgate, Kent (288), might represent a votive deposit or hoard, but should be treated as a case apart as all three pieces appear to be Scandinavian in origin and likely date to after 2000 bc (see plate in Hicks Reference Hicks1878). Largely based on their associated finds, a further eight daggers were found in contexts which might be disturbed burials or depositions linked to funerary activities.

Table 5 Flint Daggers Recovered Alone, But Which Might Derive From Disturbed Sites

Certainly, funerary contexts are the best known find spots for flint daggers in the British Isles, and some funerary contexts with flint daggers are strikingly rich. As noted above, in general, the funerary associations are consistent with the flint daggers forming part of the Beaker funerary package which is characterised by single inhumation burials with grave goods (Table 4). In fact, there is a striking consistency within the funerary rites in which these objects were used. The vast majority of interments with flint daggers are single, adult males, all tightly crouched on their left sides (Needham Reference Needhamforthcoming). Of the six contexts in which flint daggers were found with the remains of more than one individual, half of these include sub-adult remains which are not associated with the flint dagger. Two apparent flint daggers in reasonably marginal areas were found with cremation burials. Both of these depositions are unusual in that one dagger (127) appears to have been burnt with the cremation before being deposited in a cinerary urn (Smith Reference Smith1919, 18) while the other (63) might be a plano-convex knife rather than a dagger (cf. Barnes Reference Barnes1982, no. 71; Myers & Noble Reference Myers and Noble2009).

In discussing the flint daggers from funerary contexts, it is important to note common associations between them and other object types in order to better understand the rites and context in which funerary deposition of a flint dagger was deemed appropriate (Table 6). As Needham (Reference Needham2005, 201) notes, British flint daggers are strongly associated with Beakers, in distinction to contemporary burials with metal daggers. Just under half of the 43 flint daggers recovered from funerary contexts were found with Beaker pots or sherds. A further 21 funerary contexts see them associated with flint flakes and tools, most common among them flint knives and arrowheads. Other common associations include ground stone tools, such as axes (battle-axes and other ground axes), cushion stones, and sponge fingers.

Table 6 Frequency Of Association Between Flint Daggers & Various Other Notable Object Types In Funerary Contexts

Bone or antler spatulae are a particularly notable association in light of their rarity: while less than two dozen complete examples have been recovered (Duncan Reference Duncan2005), at least eight derive from five funerary contexts alongside flint daggers, a pattern of association which supports Olsen’s (in Harding & Olsen Reference Harding and Olsen1989, 104) suggestion that they might have been pressure flaking tools (cf. Harding Reference Harding2011b). Six daggers were also found associated with lumps of iron pyrite or hematite, often placed in proximity with or touching the dagger, leaving distinct red-brown stains on one face. This association might be linked to fire starting kits (cf. Stapert & Johansen Reference Stapert and Johansen1999) or to the larger sphere of pyrotechnology, including metalworking. Although metal is almost unknown in burial contexts with flint daggers – the only exception being the fragment, possibly from a chisel, in Garton Slack B 152, Yorkshire (41) – the presence of cushion stones, sponge fingers, and boar’s tusks, all objects sometimes associated with metalworking (Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick2009; Reference Fitzpatrick2011, 221–2), in burials that also contain flint daggers suggests that the daggers, and perhaps also elaborate flint knapping, fell into the same technological sphere.

Ornaments in a variety of materials are also frequently encountered in association with flint daggers in funerary contexts. Jet buttons are the most common association, being found in nine of the 14 burial contexts where ornamentation was present, and are often suggested to be deposited as part of a garment or shroud or as the fastener for an organic pouch (Czebreszuk Reference Czebreszuk2004; Shepherd Reference Shepherd1973; Reference Shepherd2009). However, in several of these burials, the buttons may not have been attached to any organic material at all, being part of piles of objects at the feet of the individuals buried in barrow 1, Irthlingborough and barrow 6, West Cotton, both excavated as part of the Raunds Area Project (131 & 132) (Harding & Healy Reference Harding and Healy2007), and positioned at the tip of a dagger placed at the hand of the interred individual at Acklam Wold B 124, Ryedale, North Yorkshire (37) (Mortimer Reference Mortimer1905; Smith Reference Smith1919, 10–11). Three burials which contained flint daggers also included bone pins which may have been clothing or hair ornaments, but could also have been used as pressure flaking tools (Duncan Reference Duncan2005). Jet pulley-rings and beads were found in four burials, in two cases alongside V-perforated buttons; and an amber ring was recovered from barrow 1 at Irthlingborough (131) in the same compact pile as the flint dagger, five V-perforated jet buttons with different quantities of wear, three cattle rib spatulae, a boar’s tusk, a slate ‘sponge finger’, a polished stone bracer which had broken and was refashioned into a second ‘sponge finger’, an elongated chalk object, a possibly unfinished triangular arrowhead, two flint knives, two flint scrapers, a retouched flint flake, a partial core, and five unretouched flint flakes (Davis & Payne Reference Davis and Payne1993; Foxon Reference Foxon2011). While this burial is extremely well-furnished, all of the burials in which flint daggers are found alongside ornaments have yielded a number of artefacts which probably tell us less about the actual possessions and life or wealth of the interred individual and more about the sorts of material appropriate to remove from circulation and place with the deceased at the time of burial (Brück Reference Brück2006; Reference Brück2009; Frieman Reference Frieman2012b; Woodward Reference Woodward2002).

The final notable find context from which flint daggers are recovered are rivers, particularly the Thames. Of the 53 daggers found in wet contexts, 43 were found during dredging activities, in dried up river channels or on the banks of rivers and streams. The ten remaining daggers were largely recovered from bogs, but two were found in reservoirs. Clearly, the antiquity of the watery find contexts cannot be guaranteed in these cases. The 43 river finds are particularly interesting as they have a distinct geographic distribution, being found almost universally in the south-east of England. The dagger from an old channel of the Trent at Staythorpe, Newark, Nottinghamshire (93) is the most northerly river find, while that recovered in dredgings from the Severn at Diglis Basin, Worcester, Worcestershire (137) is the most westerly. In fact, 33 of the flint daggers found in rivers were found in the Thames, mostly in Greater London, but one was found as far up the river as Henley, Oxfordshire (146) (Frieman Reference Frieman2013b). In this context, it is worth noting that six of the eight recorded finds of apparently Early Bronze Age, bone daggers come from the Thames as well (ApSimon 1954–Reference ApSimon5; Gerloff Reference Gerloff1975, 175–6; Smith Reference Smith1920, 13).

While the high number of finds in the Thames no doubt reflects the long history of dredging and the presence of collectors in Greater London for whom interesting antiquities would be retained, it likely also reflects a distinct set of prehistoric practices and beliefs. Later prehistory saw a long tradition depositional activity focused on the Thames and its tributaries (Bradley Reference Bradley1979; Reference Bradley1990; York Reference York2002); and, while the best known practices date to the middle of the 2nd millennium and later, they clearly originate in the Neolithic (Edmonds Reference Edmonds1995, 150; Lamdin-Whymark Reference Lamdin-Whymark2008). The nature of these depositional practices is unclear, although usually assumed to be ritual in nature. The recovery of human skulls dated from the Neolithic to the Iron Age suggests a funerary aspect to these deposition activities (Bradley & Gordon Reference Bradley and Gordon1988). During the later 3rd and earlier 2nd millennia bc material frequently encountered in dry-land funerary contexts, such as Beaker pottery, human bone, metal daggers, and stone battle-axes, appears to have been preferentially deposited in the Thames (Lamdin-Whymark Reference Lamdin-Whymark2008, 34); and this pattern can be seen to extend even further into the past, echoing Neolithic practices of deposition of complete objects, often those with mortuary associations, in the river (ibid., 45).

If the deposition of flint daggers in riverine contexts does, in fact, form part of funerary rituals, or even a separate funerary act, then the clear regional differences in flint dagger burial and river deposition locales becomes quite interesting. In fact, while there is an overlap between the areas in which these two activities were carried out, a clear regional distinction is visible, with flint daggers from rivers coming from south-east England and East Anglia – the flint dagger heartland – and flint dagger burials largely found on the periphery of this area (Fig. 5). It is possible that this distribution pattern derives from two different sets of funerary rites with different regional distributions; but, as flint daggers were just one object type occasionally deposited in a more or less uniform set of funerary practices, the regional patterning observed might well also reflect contrasting ideas of the value, function or use of flint daggers themselves.

Fig. 5 Distribution of flint daggers found in funerary (black triangles) and riverine (grey squares) contexts in the British Isles

A potential parallel is the contrast between burials with flint daggers and contemporary burials with metal daggers. While these do not have separate distribution regions, Reference NeedhamNeedham (forthcoming) has suggested that the use of flint daggers, and their common associations, in funerary contexts derived from an attempt by aspiring elites to access status while maintaining an identity distinct from elites buried with metal daggers. While Needham links distinction in burial practice to shifting relationships between communities and individuals within Britain, given the particular set of materials and contexts frequently associated with British flint daggers – not to mention their morphological characteristics – patterns of contact and communication, and possibly alliances, between British populations and their neighbours across the North Sea must be explored.

THE ORIGIN AND SIGNIFICANCE OF BRITISH FLINT DAGGERS

No obvious British precursor exists for flint daggers and it is deeply unlikely, verging on impossible, that their form originated in the British Isles despite a long tradition of flint mining and knapping. Edmonds (Reference Edmonds1995, 103–4) notes that, during the 3rd millennium bc, a distinct division in flint-knapping techniques and procedures becomes evident: quotidian flint-knapping shows a decrease in specialisation and uniformity while a number of highly specialised, and widely shared, chaînes opératoires were developed for more elaborate flint tools. These fine flint objects, including, for example, Seamer axes (Manby Reference Manby1979) and discoidal knives (Clark Reference Clark1929; Gardiner Reference Gardiner2008), are frequently found deposited in contexts which imply ritual activities linked to Grooved Ware (Edmonds Reference Edmonds1995, 105; Healy Reference Healy2012). In fact, Gardiner (Reference Gardiner2008) has noted that the poorly understood discoidal knives, like flint daggers, have a distinctly south-eastern English distribution with additional areas of concentrated deposition in Eastern Yorkshire and the Peak District, suggesting that future research might focus on possible links between the two artefact types. In Beaker contexts, barbed-and-tanged arrowheads are probably the best known of the fine lithic tools produced in the later 3rd millennium bc (Green Reference Green1980). Despite being a new form, and one with clear continental affinities (Edmonds Reference Edmonds1995, 162–3), these show obvious links to Late Neolithic British flintworking techniques, particularly in the use of pressure flaking to produce parallel oblique retouch on the surfaces of some (cf. Butler Reference Butler2005, 158–65). Similar pressure flaking is also found on some plano-convex knives, another key late 3rd millennium bc flint tool, associated with burials with Food Vessels and Collared Urns (Clark Reference Clark1932a).

A lack of recent comprehensive syntheses inevitably hampers our ability to place British flint daggers into their local technological context; but the large numbers and types of knives being produced and deposited, frequently in ritual and funerary contexts, should not be ignored. Other than plano-convex knives, various ovoid knife forms are known from around the British Isles in the 3rd millennium. For example, some bifacially worked implements ‘not elongated enough to be spearheads, or sharp enough to be knives’ (Radley Reference Radley1970a, 132), appear to have Grooved Ware associations – most famously being found in large numbers with several Seamer axes and tens of other flint objects near Holgate in York (ibid.) are a possible early form. Somewhat more recent ovate knives have been found in hoards as well as in production contexts around Grimes Graves, Norfolk (Robins Reference Robins2002). Additionally, we find very fine doubled-edged blades, such as those found in the ‘Amesbury Archer’ burial (Harding Reference Harding2011a, 94), which might well have been hafted as daggers, like the blade found with the remains of the Similaun Man (Spindler Reference Spindler1994).

A number of very fine, ovoid knives – dubbed foliate knives (sensu Ballin Reference Ballin2011b, 450) – were also identified in the course of this survey, often typologically misidentified as flint daggers (see, for instance, Table 1). These foliate knives are arguably part of the same continuum of flintworking as the flint daggers, but are slightly more recent, are usually smaller, have no distinction between a blade and hafting parts, and often show use-wear, including gloss, on diagonally opposing edges, as if the tool were rotated in the hand during use. These knives do appear to have similar functions to flint daggers within the ritual sphere, as the example found with a multiple cremation burial in a Collard Urn from Barrow 5 at Raunds demonstrates (Harding & Healy Reference Harding and Healy2007, 141; 2011, fig. SS3.1). It is more than likely that, with further research, a number of Class 4 flint daggers, particularly those identified from photographs and drawings rather than direct observation of the original object, might be reclassified as foliate knives. The, now lost, bifacial dagger or knife found in soil making up a Bell Barrow at Heatherwood Hospital, Ascot, Berkshire (338) (Bradley & Keith-Lucas Reference Bradley and Keith-Lucas1975) might, in fact, be one such example (R. Bradley, pers. comm.).

Flint daggers from elsewhere and elsewhen

Flint daggers are not in any way unique to Britain; but the British flint daggers – by dint of their small numbers and short period of use – have largely been left out of the debates about flint dagger production and use in later prehistoric continental Europe. In fact, flint daggers have been found in European contexts from Italy to Norway and several varieties appear to have circulated widely within regional exchange and communication networks (Delcourt-Vlaeminck Reference Delcourt-Vlaeminck2004; Delcourt-Vlaeminck et al. Reference Delcourt-Vlaeminck, Simon and Vlaeminck1991; Honegger Reference Honegger2002; Honegger & de Montmollin Reference Honegger and de Montmollin2010; Kühn Reference Kühn1979; Lomborg Reference Lomborg1973; Mallet & Ramseyer Reference Mallet and Ramseyer1991; Mottes Reference Mottes2001; Siemann Reference Siemann2003; Steiniger Reference Steiniger2010; Strahm 1961–Reference Strahm1962; Struve Reference Struve1955). Long, plano-convex blades, hafted as daggers, produced primarily from flint from Grand-Pressigny in the Massif Central (France) began circulating in the very late 4th millennium and reached a floruit in the first half the 3rd (Ihuel Reference Ihuel2004; Mallet et al. Reference Mallet, Richard, Genty and Verjux2004). These Grand-Pressigny daggers were made through a specialised reduction process (Mallet & Ramseyer Reference Mallet and Ramseyer1991; Mallet et al. Reference Mallet, Richard, Genty and Verjux2004; Millet-Richard Reference Millet-Richard1994) and circulated as blanks and finished daggers via the major French rivers to Brittany and Switzerland and up the North Sea coasts to Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands (cf. Delcourt-Vlaeminck Reference Delcourt-Vlaeminck2004; Delcourt-Vlaeminck et al. Reference Delcourt-Vlaeminck, Simon and Vlaeminck1991; Honegger & de Montmollin Reference Honegger and de Montmollin2010; Lomborg Reference Lomborg1973; Siemann Reference Siemann2003; Vander Linden Reference Vander Linden2012; van der Waals Reference van der Waals1991). They, and smaller imitations in local and northern French flints (Siemann Reference Siemann2003; Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann2007), were deposited in a variety of contexts, most notably alongside late Dutch Single Grave Culture burials (van Gijn Reference van Gijn2010a, 142; Reference van Gijn2010b).

In the second half of the 3rd millennium, a Scandinavian flint dagger industry also developed (Apel Reference Apel2001; Forssander Reference Forssander1936; Lomborg Reference Lomborg1973; Müller Reference Müller1902). In contrast to the Grand-Pressigny blade daggers, the large, flat and bifacially worked flint daggers produced in Danish and Swedish contexts appear to have been made preferentially from flake blanks or flat nodules of mined flint. While the flint daggers produced in Scandinavia took a variety of subtly different forms, and certainly varied in quality of manufacture and size, a sub-group of very long, very finely made daggers appear to have been produced for the funerary sphere, particularly to accompany male burials along with archery equipment and Danish Beakers (Sarauw Reference Sarauw2007; Reference Sarauw2008). After c. 2000 bc, new forms of Scandinavian flint daggers began to be produced. These daggers had elaborate hilt morphologies and imply a thriving community of specialist flint knappers and a value system in which specialised products, including lithic tools, were highly desirable (Apel Reference Apel2000; Reference Apel2004; Frieman Reference Frieman2012a; Reference Frieman2012c). Both the lanceolate and the hilted flint dagger varieties circulated widely in Europe (Frieman Reference Frieman2012c, 74–5).

In fact, the lanceolate variety looks like the most obvious inspiration for the British flint dagger industry, most likely through contacts with the Netherlands.Footnote 8 While, during the first part of the 3rd millennium, people living in Britain seemed to be mostly insular in their technological and ritual practices, developing unique material culture and monument types, after 2500 cal bc there is a distinct opening up to the larger European sphere. There is a long-standing tradition of linking British Beaker ceramics typologically to Dutch examples (Clarke Reference Clarke1970; Sheridan Reference Sheridan2008), rather than French or even Iberian material, following the ‘Dutch model’ of Beaker ceramic typology (Fokkens Reference Fokkens2012a; Reference Fokkens2012b; van der Beek & Fokkens Reference van der Beek and Fokkens2001 with references). Moreover, Vander Linden (Reference Vander Linden2012, 77) links early British Beaker funerary rites and materials to those found in the Netherlands, and Sheridan (Reference Sheridan2008) goes so far as to identify several Scottish Beaker burial contexts which she believes were designed by and for Dutch migrants; although Fokkens (Reference Fokkens2012b) has contested this identification. As noted above, Grand-Pressigny flint daggers have been found in a number of late Single Grave Culture burials with All Over Ornamented (AOO) vessels, a suggested parent form of Beaker pottery (Vander Linden Reference Vander Linden2012, 76–7 with references). From about 2300 cal bc, lanceolate Scandinavian flint daggers also appear in Dutch contexts (Beuker & Drenth Reference Beuker and Drenth2006; Bloemers Reference Bloemers1968). In contrast to the plano-convex French daggers, these flat and bifacially worked examples are found deposited almost exclusively in wet locales away from settlement contexts (van Gijn Reference van Gijn2010a; Reference van Gijn2010b), a practice which echoes the watery deposition of Scandinavian flint axes circulating in the previous centuries.

It is entirely possible that some British flint daggers, perhaps a few of the many Class 3 daggers from south-eastern England, were originally produced in Scandinavia; and future raw material analyses might focus on this question. Certainly, Kühn (Reference Kühn1979) has identified a handful of daggers from north German contexts which have very British leaf-shaped blades and tapering tangs. Indeed, some metal objects do appear to have made it from Ireland to Scandinavia during the latter part of the 3rd millennium bc (Vandkilde Reference Vandkilde1996), so the connection is not without precedent or parallel. Yet, flint daggers do not appear in datable British contexts until after the initial, Dutch-linked spread of Beaker materials and practices – they are a later, and reasonably small-scale, addition to Beaker assemblages – so simply noting a typological or technological connection to continental material does little to illuminate their significance.

British Beakers, British daggers and the ‘dagger idea’

Flint daggers in British contexts are primarily associated with Long Necked Beakers which Needham (Reference Needham2005) has dated to the centuries after 2250 cal bc and, with them, form part of his so-called ‘fission horizon’. The fission horizon is essentially characterised by the rise of competing, localised identities within the British Beaker sphere. Beaker material culture and practices become increasingly regionalised and begin incorporating a variety of distinctly British aspects, as opposed to the much more international early Beaker horizon. For example, Long Necked beakers themselves may, in their decorative schema, show some links to earlier (and distinctly British) Grooved Ware ornamentation (ibid.). Garwood (Reference Garwood2012) notes a distinct emphasis on ancestral identities highlighted through the creation of burial alignments and the deposition of heirlooms and curated human remains within burials. Reference NeedhamNeedham (forthcoming) sees this shift in practice as part of an increasing number of ways to signal status and identity within a highly competitive, if somewhat fragmented, social context.

Yet, widening our perspective to include the broader European context of this series of insular developments gives a slightly different picture. Even while the British Beaker package was becoming more regionalised, and perhaps more overtly British, flint daggers and other continental object types, notably battle-axes, various types of which had also been in circulation on the near continent since the 4th millennium (Bakker Reference Bakker1979; Zápotocký Reference Zápotocký1992), were quickly adopted and deployed in the ritual sphere. It begins to appear that the adoption of flint daggers, and more explicitly, daggers which appear to be morphologically and, at least in the south-east, functionally patterned after the Scandinavian daggers circulating in the Netherlands, was part of a conscious attempt to call back to the Dutch connection which was so fundamental to the early adoption of the Beaker package in Britain.

In this light, flint daggers within British assemblages might indicate an attempt to affiliate oneself or one’s community with a specifically continental ancestral Beaker identity, as distinct from the more regional British versions which were emerging. The regional distinction between river finds and burial finds might indicate a time lag in the adoption of flint daggers, with the former retaining their Dutch associations while the latter, deposited further away, began accruing more locally significant meanings. However, it might also indicate nuances within this specific ancestral Beaker identity, conforming nicely to the idea that Britain after 2250 cal bc was becoming strongly regionalised, not just in burial practice, but also in personal or corporate identity (Needham Reference Needham2005; forthcoming).

It is obvious that flint daggers found in British contexts form part of the wider European trend to produce, use, display and discard lithic daggers. While, in Europe, this trend lasted from the late 4th into the 2nd millennium, in Britain it was only a brief phase in the later part of the 3rd millennium. Flint daggers have been argued to form part of a larger circulation network in which a specific ‘dagger idea’ was particularly valued (sensu Vandkilde Reference Vandkilde2001, 337; see also Heyd Reference Heyd2007; Vandkilde Reference Vandkilde2005, 17). Within this conceptual framework, daggers made from metal, from lithics, and from other raw materials, such as bone, have been argued to imply distinct and distinctly new ideas about individual prestige and status, specific gendered identities and access to new ways of carrying out and thinking about technology. While daggers appear to have had no uniform physical function, the choice to wear and display a dagger on one’s person seems to have been on indicator of their participation in the large-scale contact networks which relied on the adoption of standardised and specialised production processes (Frieman Reference Frieman2012a). Flint daggers, in combining a very traditional technology and raw material with a new form and novel, frequently specialised, production processes were able to act as ‘boundary objects’, tangible expressions of people’s engagement in shared value-systems (ibid.; Frieman Reference Frieman2012c).

British flint daggers conform nicely to this pattern. While their form is novel, there was already a long tradition of expert bifacial knapping in Britain in the 3rd millennium bc (Edmonds Reference Edmonds1995); although, until further technological studies are carried out, a direct continuity of knapping practice cannot be proved. Moreover, the treatment of a number of British flint daggers indicates that they were seen as part of this tradition, despite their novel form. For example, the surface grinding visible on three flint daggers (149, 179, & 203) is also found in the production and finishing of discoidal knives (Clark Reference Clark1929). Moreover, patterns of ritual usage of fine flint tools are also retained as can be seen in the deposition of flint daggers near ritual sites, such as Arbor Low (114) or the henge or barrow at Ringlemere, Kent (290). A somewhat contentious, but possibly key example is the apparent flint dagger from cairn 2 at Biggar Common (20). Although identified as a knife in the excavation report (Finlayson in Johnston Reference Johnston1997), morphologically, it fits the criteria used above to define and identify flint daggers, being 117 mm long, fully bifacially worked and having a double-edged blade end distinct from the flat-based tang end. It was found under the cairn, not associated with any obvious funerary remains but deposited alongside a Seamer axe, a distinctly Late Neolithic object frequently found with other classic Late Neolithic types of finely made flints. This association has led some to reject the possibility that this piece is a flint dagger; however, it fits the same pattern as the daggers noted above which combine aspects of the Late Neolithic understanding of special flint tools with the new object type. Furthermore, in a period noted for its use of curated and heirloom materials in ritual contexts (eg, Woodward Reference Woodward2002), it is possible that the axe with which this putative dagger was deposited might have been considerably older than the context in which it was found.

Thus, British flint daggers can be added to the broader European dagger phenomenon, and their significance perhaps somewhat clarified. They may very well have been produced, not just to make tangible emerging localised identities within Britain or as a material signifier of status equal to copper and bronze daggers, but as a tool to confirm the continued engagement of British communities – particularly those in eastern parts of England – with trading partners, kin, and others across the English Channel. Even as the British Beaker package became more insular in composition than international, the adoption of flint daggers (and battle-axes), could have served as a mitigating factor, signalling to continental friends and contacts that they still wanted to participate in wider networks of contact and exchange. This decision to signal cross-Channel affiliation may have been made in response to the shift in Irish trade networks away from the more distant Atlantic Facade and more tightly towards Scotland in the last quarter of the 3rd millennium (Carlin & Brück Reference Carlin and Brück2012, 203; Needham Reference Needham2004). This increased flow of Irish copper and copper alloys through northern and north-western Britain might have been seen as a threat to established networks of exchange elsewhere in the British Isles, such as southern and eastern England. That flint daggers fell out of favour relatively quickly does not indicate that these trading connections were severed, but probably reflects another external factor which made southern England a particularly desirable place to travel starting in the centuries around 2000 cal bc: the development of bronze alloying and the exploitation and exchange of Cornish tin (cf. Needham Reference Needham2000).

CONCLUSIONS

This paper has provided the first collective analysis of British flint daggers in 80 years and, in doing so, has also developed a new interpretative framework in which they can be understood. The nearly 400 flint daggers found in British contexts form a strange and highly variable assemblage. Flint daggers were a local British development linked to the wider European Beaker sphere and represent an extremely high level of technical accomplishment. They, like foliate knives, barbed-and-tanged arrowheads, thumbnail scrapers, and other bifacial forms were part of the flourishing of specialist lithic technologies at the end of the 3rd millennium bc. This floruit of lithic-working is mirrored across northern and western Europe where flint daggers of a variety of forms and raw materials were also in circulation. The British examples seem to indicate an attempt to create a tangible set of signifiers for a distinct southern and eastern British identity within the emerging regionalisation of the Beaker package after 2250 cal bc. It is suggested that they were conceived of as linking these regions with networks of exchange and communication in continental Europe, particularly in the Netherlands. This Dutch connection may have been significant not just because of its proximity, but also owing to the probable Dutch origin of the British Beaker package and the increasing importance of ancestral identities after the ‘fission horizon’. Moreover, in utilising flint daggers to emphasise this connection, people were able to tap into the rich and longstanding symbolism of the ‘dagger idea’ linked to status, knowledge, and desire to participate in long-distance networks of exchange. In other words, people living in southern and eastern Britain adapted their already rich lithic industry to draw on the potent symbolism of flint daggers and use it to emphasise their integration into wider European networks of exchange, probably in an effort to maintain their engagement in these networks in the face of increasing Irish and Scottish dominance of the British and Irish metal sources.

Yet, questions remain as to the significance of flint daggers in British contexts. They did not emerge from a void, but were part of a wider lithic industry in Britain which is still poorly understood and merits considerable future research to define the variety of tool types being produced, the quality of flint knapping being carried out in different regions and sectors and the fine chronology of the final floruit and decline of prehistoric flint knapping in Britain (cf. concerns raised in Gardiner Reference Gardiner2008). Furthermore, their placement alongside a variety of craft-working tools and battle-axes in burial contexts hints at a special relationship between knapping and ground-stone technologies which deserves considerable attention. Finally, the scattered distribution of flint daggers of obvious Scandinavian origin underscores the importance of looking more deeply into trade and exchange around the North Sea in the 2nd millennium, particularly in areas which have not been traditional centres of prehistoric research, such as Lincolnshire.

Chiefly due to the (relative) abundance and allure of Early Bronze Age metal finds, the lithic industry of the British and Irish Early Bronze Age has been largely disregarded since Clark wrote many of the seminal descriptive and typochronological papers in the 1920s. Yet, as recent research around Europe shows, lithic technology in the 3rd and 2nd millennia bc was neither subordinate to nor marginalised by metallurgy. In fact, the networks which allowed metal and metal technology to circulate were first established by people travelling great distances to access polished axes, flint daggers, and ground-stone battle-axes. This re-evaluation of the British flint daggers should not be taken as the definitive statement on their typology, technology, function, or significance; rather, it is hoped, this paper will reopen and reinvigorate discussions about British lithic industries of the 3rd and 2nd millennia bc and their significance to wider societal and technological trends.

Acknowledgements