1. Introduction

Sentence processing is known to be driven to a large extent by speakers’ expectations about what comes next (Altmann & Kamide, Reference Altmann and Kamide1999; Hale, Reference Hale2001; Levy, Reference Levy2008; MacDonald, Reference MacDonald1993; McRae, Spivey-Knowlton, & Tanenhaus, Reference McRae, Spivey-Knowlton and Tanenhaus1998, among many others) and recent research has stressed the role of expectation in discourse processing (Dery & Koenig, Reference Dery and Koenig2015; Kehler & Rohde, Reference Kehler and Rohde2016; Rohde, Levy, & Kehler, Reference Rohde, Levy and Kehler2011; Scholman, Rohde, & Demberg, Reference Scholman, Rohde and Demberg2017; van Bergen & Bosker, Reference Van Bergen and Bosker2018). A classic example where discourse expectations have been shown to affect discourse processing is illustrated in (1).

Sentences with verbs like congratulate in (1) – which are often called ‘object-biased implicit causality verbs’ (Garvey & Caramazza, Reference Garvey and Caramazza1974) – encourage speakers to expect the next sentence to explain why Wendy congratulated somebody and readers expect the second sentence to be about the person who is congratulated. This is why readers tend to interpret the temporarily ambiguous pronoun she in (1a) as referring to Janice (object) and to process the subject pronoun in (1b) faster when reading he, which can refer to the person being congratulated (Chris), than when reading she. Finally, participants are more likely to produce Chris (or he) than Wendy (or she) as the subject of their continuations after reading the sentence in (1c). Such continuation biases and expectations have been replicated in several languages (see Brown & Fish, Reference Brown and Fish1983a, for English; Brown & Fish, Reference Brown and Fish1983b, for Chinese; Cozijn, Commandeur, Vonk, & Noordman, Reference Cozijn, Commandeur, Vonk and Noordman2011 for Dutch; Kim & Park, Reference Kim and Park2016, for Korean; Pyykkönen & Järvikivi, Reference Pyykkönen and Järvikivi2010, for Finnish; and Hartshorne, Sudo, & Uruwashi, Reference Hartshorne, Sudo and Uruwashi2013, for a cross-linguistic comparison).

The goal of the present study is to investigate whether speakers’ expectations of what comes next in discourse, as well as their discourse productions, can be influenced by the frequency distribution of constructions they encounter in the language they speak, or whether their expectations and productions are immune to such grammatical constraints and resulting frequency distributions. We report two story continuation experiments similar to the experiment we alluded to with respect to (1) in two typologically unrelated languages, English and Korean, and in two discourse genres, monologues and conversations. The purpose of these experiments is to determine whether Korean speakers expect an explanation continuation to the same degree as English speakers do; i.e., whether they expect the sentence that follows a context sentence to provide the cause of the event that was just described, both when the context sentence describes an event that highly implies a cause, as in (2a), and when it does not, as in (2b).

When language users produce or comprehend successive utterances or discourse segments, they attempt to relate them to each other in a way that makes sense of the discourse as a whole, i.e., they try to maximize discourse coherence (e.g., Hobbs, Reference Hobbs1985; Mann & Thompson, Reference Mann and Thompson1988, among others). Example sentences in (3) illustrate some of the discourse relations between two discourse segments (typically, sentences or clauses) that can help bring about discourse coherence. (The second discourse segments in (3) are among those produced by our participants in the experiments we report on, when prompted with the first segment.)

The second sentence in (3a) explains why the event described by the first happened, the second sentence in (3b) elaborates on how the event described by the first sentence was carried out, and, finally, the second sentence in (3c) describes the outcome of the event described by the first sentence. These three continuations form coherent discourses together with the first sentence because of the existence of an explanation, elaboration, and result relation between the two sentences, respectively (see Hobbs, Reference Hobbs1985; Kehler, Reference Kehler2002; Mann & Thompson, Reference Mann and Thompson1988; Sanders, Spooren, & Noordman, Reference Sanders, Spooren and Noordman1992, for more or less comprehensive lists of discourse relations).

Many studies have suggested that the order of the description of events tends to correspond to the order in which the events occurred (e.g., Chafe, Reference Chafe and Givón1979; Hopper, Reference Hopper and Givón1979; Levinson, Reference Levinson2000; Zwaan, Reference Zwaan1996). When the cause is reported first and the effect follows, the order of the descriptions is considered ICONIC or FORWARD (Sanders & Sweetser, Reference Sanders and Sweetser2009); the converse order is considered NON-ICONIC or BACKWARD. As the iconic/forward RESULT relation between two discourse segments is considered more natural than the non-iconic/backward EXPLANATION relation, discourse segments related via a result relation are predicted to be produced more frequently and comprehended faster than discourse segments related via an explanation relation. However, when verbalizing a sequence of events by conjoining clauses or sentences, speakers are also constrained by the grammars of their languages, and languages vary in how they constrain the ordering of clauses. The order of discourse segments could therefore occur with different frequencies and thus differentially influence discourse productions across languages. This is the issue we address in this paper.

That language processing is constrained by language-specific properties is well established. Ease of understanding of complex syntactic structures (e.g., relative clauses) may differ across typologically distinct languages, and sentence production strategies (e.g., the size of planning units) may also vary across languages (see Jaeger & Norcliffe, Reference Jaeger and Norcliffe2009, and Norcliffe, Harris, & Jaeger, Reference Norcliffe, Harris and Jaeger2015, for review). Speakers of different languages may also differ in their choice of referring expression or referential bias as a result of differences in grammars (e.g., Hwang, Reference Hwang2018; Kim & Grüter, Reference Kim and Grüter2019). To our knowledge, however, no study has yet addressed the question of whether grammatical differences affect how speakers CONSTRUCT a discourse, i.e., whether it affects choices that span more than a sentence. The present study aims to fill that gap, as it investigates the effect of grammatical differences between English and Korean on discourse production.

Korean is a highly agglutinative head-final language and provides speakers with 31 causal markers, 15 conjunctive subordinators, and 16 conjunctive adverbials, according to Sohn’s (Reference Sohn, Dixon and Akhenvald2009, p. 296) categorization. To express a forward result relation between two clauses, Korean speakers can choose among 15 clause-final morphs that express the concept of cause and then express the effect in a separate clause, as in (4a), or choose among 15 clause-initial conjunctive adverbials that express the concept of consequence or effect, as in (4b). The relevant markers are bolded in (4).

The semantics and pragmatics of markers differ in subtle ways: they can encode differences in the strength of the cause–effect relation, the presence or absence of an overlap between the cause and the effect, and so forth. In contrast to the forward result relation, the backward explanation relation is hard to express and is expressed relatively rarely in Korean. There is only one conjunctive adverbial that marks this discourse relation: the adverbial waynya(ha)myen, which can appear at the beginning of a cause clause that follows an effect clause, as in (5a). Speakers sometimes also begin with an effect clause and follow with a cause clause that ends with a conjunctive morph expressing the concept of cause, as in (5b).

The pattern exemplified in (5b), though, does not conform to the standard clause linkage rules exemplified in (4a) and is infrequent. It mostly occurs when a speaker wishes to express an afterthought, attempts a repair, or has in mind some specific pragmatic and/or stylistic goal, e.g., the desire to emphasize the cause. It is not uncommon for this fragment-type cause clause, e.g., Siho-ka ka-nikka in (5b), to occur as an independent utterance in conversation, just as it is in Japanese (Ford & Mori, Reference Ford and Mori1994). Overall, Korean provides speakers with a rich array of morphosyntactic means to explicitly encode the result discourse relation, but it is much harder and infrequent to explicitly encode the explanation discourse relation.

In contrast to Korean, English causal markers occur at the beginning of a clause, as shown in (6) (again, relevant markers are bolded). The connectives marking the cause include because and since, and the connectives marking the effect include so in (6a) and therefore, among many others. Importantly, the encoding of result and explanation relations is highly flexible in English, as shown in (6b) and (6c): clauses encoding the cause can either precede or follow the clause encoding the effect. English is thus less constrained than Korean when it comes to backward or non-iconic relations between discourse segments. In fact, Diessel (Reference Diessel2001) and Diessel and Hetterle (Reference Diessel, Hetterle and Siemund2011) argue that in their corpus English speakers seem to prefer a backward ordering of cause and effect, i.e., the order in (6c) over the order in (6a) or (6b).

Given these grammatical differences in the explicit encoding of result and explanation relations, speakers of English and Korean have had different frequencies of experience with forward and backward causal relations. If linguistic experience significantly modulates speakers’ expectations in language processing, as much of the recent literature suggests, such differences in frequencies of experience may shape or influence the way English and Korean speakers construct discourses, in particular the frequency with which they produce non-iconic discourses, i.e., discourses in which the description of the effect precedes the description of cause. Our hypothesis is that the grammar of Korean, which severely restricts the explicit marking of explanation relations, will lead Korean speakers to produce less frequently than English speakers explanation continuations even when no explicit marker of a discourse relation is present.

The contrast we have just discussed in how causes and effects are marked is not specific to Korean and English. Head-final languages like Korean tend to use clause-final connectives in subordinate clauses while head-initial languages like English tend to put corresponding connectives at the beginning of clauses. Furthermore, the position of connectives (clause-initial vs. clause-final) affects the preferred order of clauses (main and then subordinate vs. subordinate and then main clause): a clause that includes a clause-final connective typically rigidly precedes a main clause, while a clause that includes a clause-initial connective can occur more freely before or after the main clause. Putative differences in the processing and production of causal discourse relations between English and Korean might therefore extend to head-initial vs. head-final languages.

Just as speakers try to construct a coherent discourse for their listeners or readers in monologues, as in (7a) (Hobbs, Reference Hobbs1979), conversational partners bear the mutual responsibility of assuring discourse coherence while taking turns, as in (7b) (Clark & Schaefer Reference Clark and Schaefer1987; Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson, Reference Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson1974). In both kinds of discourse, there should be a clear conceptual relationship between the discourse segments S1 and S2. In fact, Rohde (Reference Rohde2008) shows that, given a context which favors a causal relation between discourse segments, English speakers are almost equally likely to produce explanation continuations (S2) to the same sentence prompts (S1) in monologues and conversations.

The grammatical constraints and typological differences just discussed may have a different effect on monologues and conversations, though. When the assertive discourse segment (S1) is produced in the monologue in (7a), Speaker A will most likely continue with another assertive discourse segment (S2) such as Janice graduated. In conversations like (7b), however, the conversational partner, Speaker B, enjoys more freedom. She can respond not only with an assertion of her own but also with a question such as Why did she do that? or ask if Speaker A agrees with her suggestion as in She is graduating, isn’t she? Although these two latter contributions also provide an explanation for the event described by the first sentence, responses that consist of questions or include tags are not subject to the grammatical constraints on clause linkage just discussed. In other words, since questions that suggest or ask about a possible explanation for the event are possible continuations to a prompt sentence in conversations, the constraints on the assertion of an explanation imposed by Korean grammar are less likely to have an impact on conversations than on monologues. We therefore expect any effect of the grammar of Korean on discourse production to be attenuated or non-existent in conversations.

Conversations such as (7b) are important to test our hypothesis that grammar can indirectly affect discourse production. After all, even if we were to find that Korean speakers are less likely to continue with an explanation for the event described by the first sentence, as in (3), it could just be that for some conceptual or cultural reasons Korean speakers favor more than English speakers iconic descriptions of sequences of events. Comparing the production of explanation relations in monologues and conversations can be helpful in disentangling between grammatical and cultural/conceptual sources of putative differences in the production of explanation continuations. If differences in explanation continuations stem from conceptual or cultural differences in speakers’ preference for iconic descriptions, conversations should pattern with monologues; if differences in explanation continuations stem from grammatical differences, conversations should pattern differently from monologues.

In sum, the contrast in the English and Korean grammar of causal connectives – the two languages constrain differently the way speakers can mark explanation and result relations in assertions – provides an ideal ground to address this paper’s research question of whether grammatical constraints modulate speakers’ discourse expectations and their choice of discourse relation in production. Korean grammar strongly favors the expression of a cause to precede that of an effect, while English grammar much more freely allows the expression of a cause to precede or follow the expression of an effect. This difference in grammar means that Korean speakers have encountered much fewer effect–cause discourse sequences than English speakers. We hypothesize that this preponderance of the cause–effect order in the narratives they have had experience with leads Korean speakers to favor that order of presentation more than English speakers, even when no connective marking is present. Additionally, we predict that the putative effect of grammatical differences only applies to assertions, as Korean constraints on the expression of explanation continuations only apply to assertions. The effect of language on explanation continuations will therefore be stronger where assertions prevail, e.g., in monologues, and be weaker or disappear in discourse genres where explanations can be expressed through non-assertive utterances such as questions, e.g., in conversations. Finally, we expect Korean speakers engaging in conversations to use other forms of continuations than assertions or statements (e.g., questions) to express explanation continuations than do English speakers: if Korean speakers engage in causal reasoning as much as English speakers do, they will take advantage of the ability to utter other forms of continuations, like questions, to express what they can only express with difficulty in declarative form.

To address this paper’s research questions, we conducted two story continuation experiments, one in a monologue setting (Experiment 1) and one in a conversational setting (Experiment 2). In the monologue experiment, we presented participants with a sentence prompt and asked them to provide a continuation that they thought was the most natural given what they had just read. In the conversation experiment, we presented the same sentence prompts, but presented them as utterances of a hypothetical conversational partner. We asked participants to provide their response to this partner. Our stimuli contained so-called IMPLICIT CAUSALITY (IC) verbs, which are known to facilitate explanation continuations in both types of discourse, as well as non-IC verbs, which are known to be neutral with respect to causality (Garvey & Caramazza, Reference Garvey and Caramazza1974). This IC manipulation was intended to ascertain Korean speakers’ sensitivity to event causality in discourse production and to confirm the previous finding that Korean speakers perceive and react to causally related events described by IC verbs in a way that is similar to that of English speakers (Kim & Park, Reference Kim and Park2016; Yi, Reference Yi2019). If they do, any effect on the frequency of explanation continuations is unlikely to be due to a differential sensitivity to events that imply causes.

We predict that IC verbs facilitate explanation continuations in both languages and in both genres, and that English and Korean speakers differ only in their general preference for an explanation relation in monologues but not in conversations. In other words, we expect a main effect of IC verbs in both experiments, and most importantly, a main effect of language (Korean speakers produce less explanation continuations) in Experiment 1, but not in Experiment 2. We predict no interaction between language and implicit causality, i.e., we expect IC verbs to lead to an equal increase in explanation continuations in both languages. Finally, we predict that English and Korean speakers do not differ in their preference for a result relation in either monologue or conversation, as the two languages do not differ grammatically in the expression of result relations.

Summarizing, we predict (1) that in monologues, Korean speakers are less likely to produce explanation continuations than English speakers but equally likely to produce result continuations, and (2) that in conversations, English and Korean speakers do not differ in how likely they are to produce an explanation or result continuation. If our predictions are borne out, our experiments will suggest that grammatical constraints can indeed modulate discourse production even in the absence of cognitive differences in speakers’ attention to causal relations.

2. Experiment 1

2.1. method

2.1.1. Participants

Forty English native speakers and 40 Korean native speakers participated in this experiment. English speakers were undergraduate students at the University at Buffalo who took an introductory psychology class and who took part in the experiment for course credit. None of them spoke Korean. Korean participants included undergraduate students at Seoul National University and other adult speakers living in Seoul and its surrounding areas. Many of them learned English as a foreign language but did not speak English fluently. They were paid $7 for their participation.

2.1.2. Material and design

The experimental material included 24 sentences with IC verbs and 24 sentences with non-IC verbs. We borrowed our English IC verbs from Rohde’s (Reference Rohde2008) Experiment 4, an experiment that tested the effects of IC verbs on sentence continuations. Our IC verbs consisted of 12 subject-biased IC verbs (SIC) and 12 object-biased IC verbs (OIC). Previous research has shown that, when interpreting a sentence that contains an IC verb, people tend to be biased toward the filler of a particular grammatical function in their attribution of causality (Au, Reference Au1986; Brown & Fish, Reference Brown and Fish1983a; Garvey & Caramazza, Reference Garvey and Caramazza1974). For example, upon reading a sentence with an SIC verb, as in (8a), readers are more likely to assume that the referent of the subject (Wendy) is the cause than the referent of the object (Chris), by continuing with, for example, She continuously tapped beats on his bedroom door. Conversely, upon reading a sentence with an OIC verb, as in (8b), readers are more likely to assume that the referent of the object (Chris) is the cause than the referent of the subject (Wendy), by continuing with, for example, He just graduated from college. Similar IC-verb biases exist in other languages (Hartshorne, Sudo, & Uruwashi, Reference Hartshorne, Sudo and Uruwashi2013; Kim & Park, Reference Kim and Park2016; Rudolph & Försterling, Reference Rudolph and Försterling, F.1997; Yi, Reference Yi2019). We counterbalanced verb biases (SIC and OIC verbs) in the construction of our materials. Non-IC sentences contained verbs that have little to do with implicit causality, as exemplified in (8c).

We prepared two sets of stimuli, one in English and the other in Korean. Corresponding sentences were paraphrases. We also kept the sentence structures the same as much as possible, but there were some inevitable differences. Whereas all English IC verbs are strictly transitive, only Korean OIC verbs are transitive, as shown in (9a). Korean SIC verbs (for the most part psych verbs) are intransitive (Nam, Reference Nam2009). For example, the Korean counterpart to the English SIC verb surprise, nolla-, is best translated as ‘to be/get surprised’, as in (9b), with a nominative noun phrase expressing the experiencer argument and a dative noun phrase expressing the stimulus argument, respectively. In other words, the participant roles filled by subject and object noun phrases in English are filled by dative and nominative noun phrases, respectively, in Korean. One way of transitivizing Korean verbs like nolla- is to add the causative suffix -key ha-, as in (9c) (lit. ’to cause someone to get surprised’). To minimize potential effects of this syntactic difference between English and Korean SIC verbs, Korean SIC experimental items were divided into SIC1 and SIC2 items (6 each). Korean SIC1 items used intransitive SIC verbs, as in (9b) and SIC2 items used transitive SIC verbs (e.g., through the use of the causative suffix -key ha-), as in (9c); the English counterparts of these SIC experimental items were all transitive.

We used typical proper names to express semantic arguments. Female and male names were counterbalanced across the subject and object positions to forestall any potential effects from participants’ gender biases. Items were pseudo-randomized so that any two IC items were separated by at least one and sometimes two non-IC items. The full list of stimuli is provided in the ‘Appendix’. Each sentence stimulus was presented on a single line, as illustrated in (10). Stimuli were split into two lists for each language, with each list containing two blocks of the experimental items, 12 IC and 12 non-IC sentences per block. All sentences in the first block of the experiment ended with a full stop, as in (10a) (hereafter, free continuation responses). Sentences in the second block included the explicit connective because or its Korean equivalent, as in (10b) (hereafter, because responses). Verbs in each block were counterbalanced between the two lists. The purpose of including a because block was to determine whether Korean IC verbs show the same implicit-causality subject or object bias as English IC verbs when an explanation discourse relation is explicitly encoded. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two lists. Overall, we collected 20 responses per experimental item for each language.

2.1.3. Procedure

In this story continuation experiment, participants were given a sentence prompt and asked to provide a sentence that they thought was the most natural continuation of the sentence they had just read. We encouraged participants to write the first sentence that came to mind as they read the prompt sentence and not to change later on the sentence they provided. The English version of the experiment was conducted on a computer. Subjects were individually led into a room and seated in front of a computer monitor and a keyboard. The experiment was run using E-prime and items were presented on the computer screen one at a time. The Korean version of the experiment was conducted using a booklet where each page contained one item. All other settings were the same as for the English version of the experiment. At the beginning of the experiment, participants read instructions and completed practice items while an experimenter was present; they were encouraged to ask questions to make sure they understood the task. Once participants had completed the practice items and said they understood the procedure, the experimenter let them move on on their own by pressing a key or flipping a page. Both the Korean and English versions of the experiment took about 40 minutes.

2.1.4. Data coding

A small number of trials in which subjects provided no or incomprehensible continuations were excluded: two Korean trials and six English trials. Each remaining free continuation response (958 in Korean and 954 in English) was coded as to its discourse relation to the prompt sentence, i.e., explanation, result, elaboration, occasion, parallel, violated expectation, and background, based on Rohde’s (Reference Rohde2008) criteria. As we are particularly concerned with the explanation and result relations, we grouped together the other relations under the label other. We additionally coded explanation and result continuations as to whether the discourse relation was explicitly marked at the beginning of the continuation or not. Continuations that began with an explicit causal connective were coded as connective (e.g., because/왜냐하면 waynyahamyen, so/그래서 kulayse), and those that did not were coded as none. Our coding scheme is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Coding scheme for discourse relations and markers with example continuations

For the analysis of the effect of IC bias because responses were coded as to which entity was causally responsible for the event described by the prompt sentence. Explanation continuations that attributed the causal responsibility of the event described by the prompt sentence to the referent of its subject were coded as subject, while those that attributed the causal responsibility to the referent of the object were coded as object. All other causal attributions were coded as other, including those that attributed it to neither the referent of the subject nor the referent of the object or to both. This scheme was applied consistently to all IC items in both English and Korean, except for Korean SIC1 sentences. As explained above, in the case of SIC1 sentences, the semantic role of the English subject NP corresponds to the semantic role of the Korean dative NP, and the semantic role of the English object NP corresponds to the semantic role of the Korean subject NP. These Korean sentences were coded the way their English counterparts were for purposes of analysis, i.e., ascription of causality to Korean subject and dative NPs in SIC1 sentences were coded as object and subject, respectively. Table 2 illustrates the coding schemes.

Table 2. Coding scheme of Implicit Causality biases for because responses

2.1.5. Data analysis

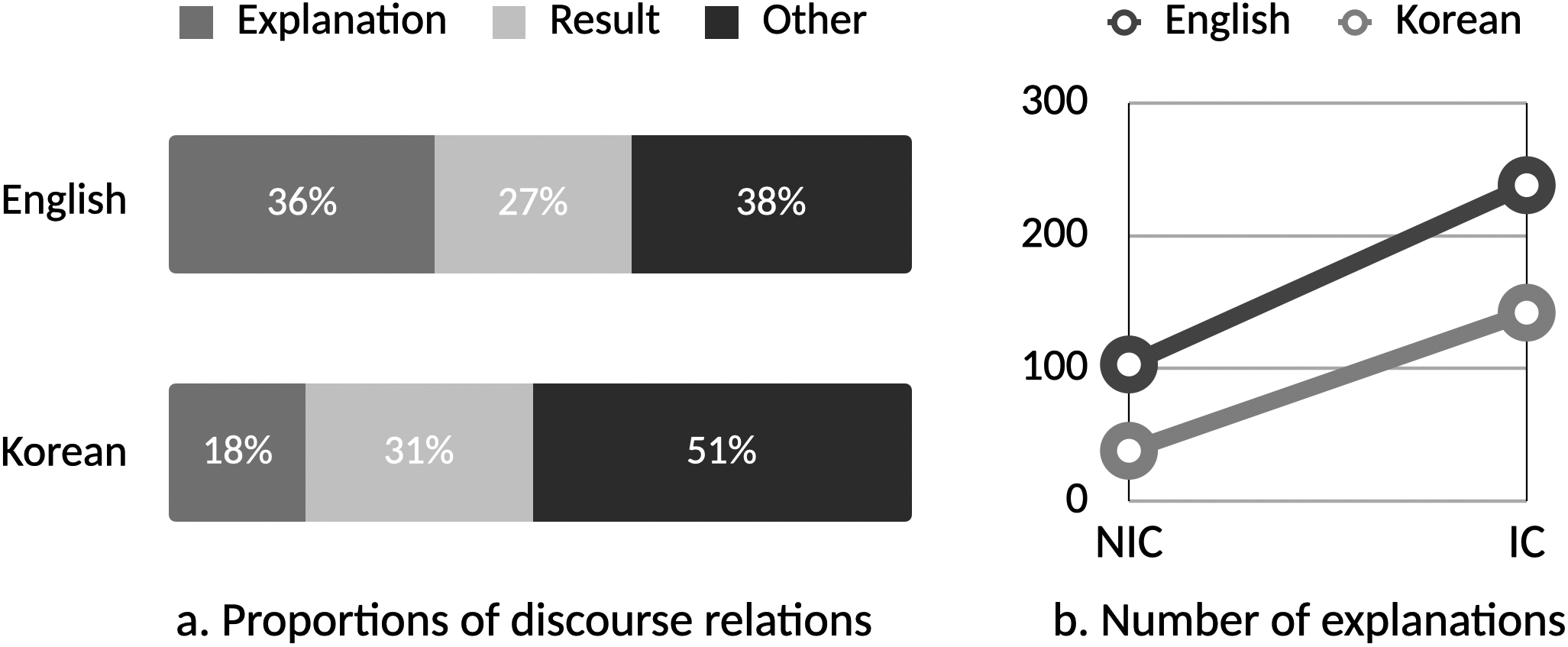

Table 3 shows the number and percentage of continuations for each discourse relation produced by our English and Korean participants. Overall, Korean speakers produced much fewer explanation continuations and more other continuations (particularly, background continuations) than English speakers.

Table 3. Distribution of continuation by discourse relation and language in Experiment 1

We used mixed-effects logistic regressions to analyze the results of Experiment 1. We first fitted a model that predicted an explanation continuation to free continuation responses, i.e., explanation (1) or not (0, other or result). The model had two fixed factors, language (English (0) or Korean (1)) and implicit-causality (NIC (0) or IC (1)), as well as their interaction. Following Barr, Levy, Scheepers, & Tily (Reference Barr, Levy, Scheepers and Tily2013), we ran the maximal models justified by the design, i.e., models that included a by-subject random intercept and random slope for implicit causality and a by-item random intercept. We report the maximal models, unless otherwise noted. We then examined the effect of language on the result relation. We fitted to the same dataset a model that predicted a result continuation, i.e., result (1) or not (0, other or explanation). All model settings remained the same. Implicit causality was still included as predictor because IC verbs increase the number of result continuations (although less so than explanation continuations), an effect known as Implicit Consequentiality (e.g., Pickering & Majid, Reference Pickering and Majid2007; Stewart, Pickering, & Sanford, Reference Stewart, Pickering and Sanford1998). We then conducted the same two analyses on the subset of continuations that did not include a connective marking the discourse relation between the prompt and response sentences.

Second, we analyzed because responses to examine the effect of IC bias in English and Korean. The goal of this analysis was to determine whether Korean speakers show the same causal attribution biases as English speakers do. We excluded from analysis continuations that attributed the cause of the event described by the prompt sentence neither to the subject nor to the object. We examined the effect of IC bias on all IC responses as well as on only those responses where English and Korean agree on assignment of thematic roles to subject and object grammatical functions (i.e., all responses except SIC1 condition responses). The first set of responses included 687 and 721 datapoints and the second 602 and 582 datapoints (for English and Korean, respectively). Using mixed-effect logistic regression, we fitted to the data a model that predicted causal attribution to the referent of the object of the prompt sentence. The model’s fixed factors included the known IC biases of individual verbs, language, and their interaction. Again, we ran the same maximal model justified by the design.

Finally, we ran two post hoc analyses on free continuation responses. First we examined whether SIC and OIC verbs equally increased the likelihood of explanation continuations in English and Korean. For each language, we fitted to the data a model that included IC condition as predictor of an explanation continuation. In this analysis, the dependent variable is explanation (1) or not (0, other or result) and the independent variable is the IC condition with three levels, the SIC, OIC, and the non-IC verb condition (NIC) (which served as baseline). Second, we reanalyzed all free continuation responses that were not other continuations, i.e., either an explanation (=1) or result (=0) relation to the prompt sentences, as we were particularly interested in these two relations. We fitted a new mixed-effect model to this subset of the data, keeping all model settings constant.

2.2. results and discussion

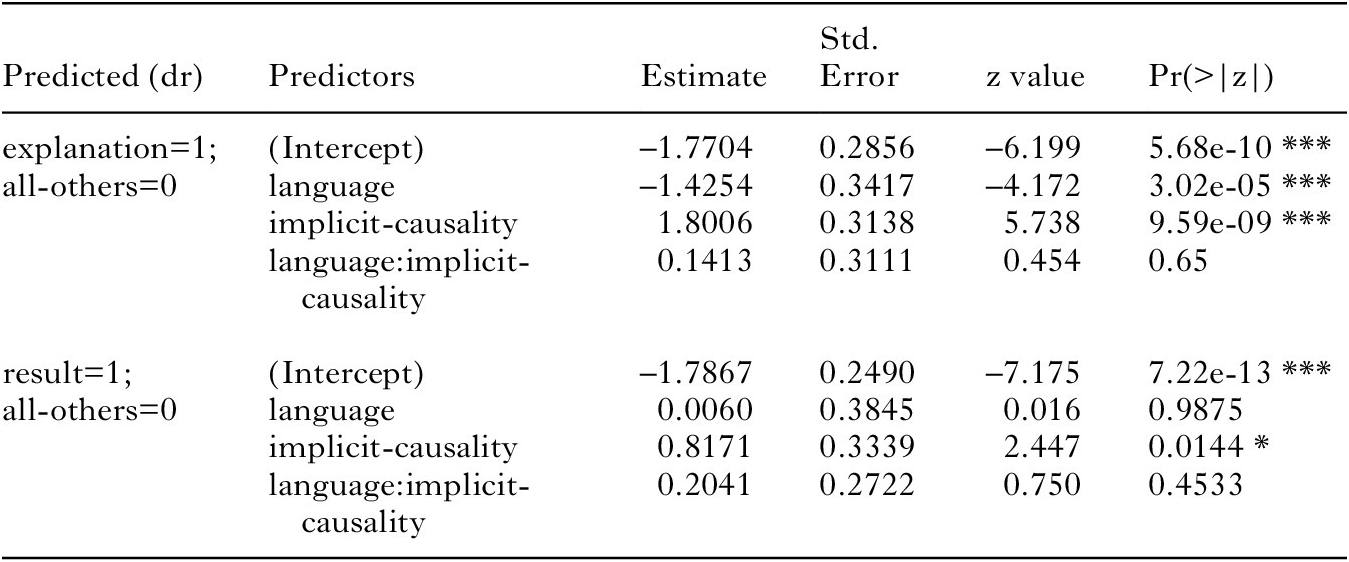

The primary goal of this experiment was to examine whether the likelihood of producing an explanation relation is modulated by the grammar of a participant’s language. The result of our mixed effects logistic regression analysis on participants’ free continuations with IC, language, and their interaction as predictors showed that a participant’s language and the presence or absence of an IC verb in the prompt sentence were significant predictors of the production of an explanation continuation. There was no interaction between these two predictors, as predicted. Korean speakers produced significantly less (and English speakers produced significantly more) explanation continuations (language, b = –1.43, SE = 0.34, z = –4.17, p < .001) and speakers of both languages produced more explanation continuations when the prompt sentence contained an IC verb than when it did not (IC, b = 1.80, SE = 0.31, z = 5.74, p < .001). The absence of interaction between language and presence or absence of an IC verb suggests that speakers of both languages were equally sensitive to the expectation of an explanation as a result of the implicit causality of IC verbs. Results of these two models are summarized in Table 4.Footnote 1

Table 4. Fixed effects in the mixed-effect models in Experiment 1 (monologue)

notes: n=1912; language (English=0; Korean=1), implicit-causality (NIC=0; IC=1)

Formula: dr ~ language * implicit-causality + (1+implicit-causality|subject) + (1|item), Data: monologue

To examine further whether the effect of language on the production of an explanation continuation is due to differences in propensity for causal reasoning between speakers of Korean and English, we tested whether the likelihood of another causal continuation, namely, a result continuation, was modulated by the participants’ language as well. The result of a mixed-effects model showed that there was no language effect on the production of result continuations (b = 0.006, SE = 0.38, z = 0.016, p = .988), suggesting that Korean speakers produce as many result continuations as English speakers do and are thus as apt to engage in causal reasoning as English speakers are. We also found that both sets of speakers produced more result continuations when IC verbs are present than when they are not, thus confirming the effect of implicit consequentiality typical of IC verbs.Footnote 2

The presence of an effect of language on explanation but not result continuations is consistent with our hypothesis that it is differences in the grammar of Korean and English that modulate speakers’ production of explanation continuations. Had our Korean participants been less inclined to engage in causal reasoning than our English participants, they would have been less likely than our English participants to provide result as well as explanation continuations. But in fact Korean participants were only less likely to provide explanation continuations. One possible explanation for the effect of language on explanation continuations is that participants simply produced markers of discourse relations in a way that reflects their lexical frequencies. The fact that clause-initial connectives marking a result discourse relation abound in Korean, but connectives marking an explanation relation are rare, might have led our participants to choose connectives that mark a result relation more frequently than connectives that mark an explanation relation. To investigate this possibility, we re-ran the same analyses after excluding explanation and result continuations that were explicitly marked by a connective, which were very few: 32 explanation and 23 result continuations in English and 5 explanation and 16 result continuations in Korean. The new dataset contained 1836 continuations. The results were the same as in our previous analyses. We still found a language effect on explanation continuations (b = –1.31, SE = 0.34, z = –3.86, p < .001), but not on result continuations (b = 0.15, SE = 0.22, z = 0.698, p = .49), suggesting that the effect of grammar on the choice of continuation persists when no marker of the discourse relation is produced, and that the language effect on explanation continuations is not therefore a mere reflection of the relative lexical frequency of connectives used in these continuations.

To examine the effect of IC bias on continuations, we also analyzed because responses. We found that Korean speakers exhibit the same verb-specific biases as English speakers do, as illustrated in Figure 1. They tended to attribute the responsibility for the event described by an SIC verb to the referent of that verb’s subject and the responsibility for the event described by an OIC verb to the referent of that verb’s object (with all IC responses, SIC, b = –1.01, SE = 0.35, z = –2.92, p < .01; OIC, b = 2.23, SE = 0.37, z = 6.01, p < .001; for all responses except SIC1 responses, SIC, b = –1.63, SE = 0.55, z = –2.94, p < .01; OIC, b = 2.47, SE = 0.47, z = 5.27, p < .001; statistics are for intercept-only models without a subject random slope for implicit causality, because models that included this factor did not converge). We found no main effect of language and no significant interaction between IC type and language. These results replicate IC bias effects previously reported for both English (Au, Reference Au1986; Brown & Fish, Reference Brown and Fish1983a) and Korean (Kim & Park, Reference Kim and Park2016; Yi, Reference Yi2019), suggesting that Korean and English speakers tend to make similar causal attributions after sentences that contain IC verbs.

Fig. 1 Implicit Causality biases in English and Korean.

Our first post-hoc analysis of the free continuation data examined whether both SIC and OIC verbs lead to more explanation continuations. The results of this analysis showed that, indeed, both SIC and OIC verbs significantly increased the likelihood of a speaker producing an explanation continuation in both English (SIC, b = 1.52, SE = 0.45, z = 3.41, p < .001; OIC, b = 2.23, SE = 0.42, z = 5.27 p < .001) and Korean (SIC, b = 2.26, SE = 0.52, z = 4.30, p < .001; OIC, b = 1.85, SE = 0.53, z = 3.47, p < .001). The presence of either type of IC verb in prompt sentences significantly increased the likelihood of a participant producing an explanation continuation in both languages, suggesting that Korean speakers engage in causal reasoning after reading sentences containing SIC and OIC verbs just as English speakers do.

Our second post-hoc analysis on free continuation responses included only explanation and result continuations and excluded other continuations. The results of this analysis showed that language is a significant predictor of the choice of discourse relation (b = –1.33, SE = 0.44, z = –3.02, p < .01): Korean speakers were less likely to choose an explanation continuation than English speakers.

As summarized in Figure 2, Experiment 1 suggests that the effect that one’s language has on the choice of explanation continuations is not due to the fact that speakers of one language (Korean) are less affected in their continuations by implicit causality verbs than speakers of another language (English), or that they do not engage in causal reasoning as much as English speakers do. Importantly, the effect of language persists when continuations do not include the hypothesized grammatical cause of differences in continuation preferences, namely, when continuations do not include connectives that explicitly mark discourse relations.

Fig. 2. Summary of Experiment 1 (monologue).

The difference we observed between the likelihood of English and Korean speakers producing an explanation continuation is consistent with our hypothesis that differences in grammar can lead to differences in discourse production. But alternative explanations are possible. Korean speakers or Korean narratives might prefer iconic discourse order more than English speakers or English narratives do for cultural or conceptual reasons that have little to do with grammar. The main goal of Experiment 2 was to tease apart the grammatical and cultural/conceptual explanations for the results of Experiment 1. If the differences in likelihood of an explanation continuation we observed were due to grammatical differences between English and Korean, we expect as many explanation continuations in genres where no relevant grammatical differences exist between the two languages, namely, in conversation, particularly when a conversational participant uses questions. If the differences in likelihood of an explanation continuation we observed were due to cultural or conceptual differences, we expect Korean speakers to produce fewer explanation continuations just as much in conversation as in monologues.

3. Experiment 2

The purpose of our second experiment was to examine (1) if the effect of language on explanation continuations varies with discourse genre, and (2) whether the difference in behavior of English and Korean speakers in Experiment 1 was due to differences in grammar, as we hypothesize, or to more conceptual or cultural differences. More precisely, we wanted to test the hypothesis that the effect of language on explanation continuations is limited to discourse genres in which assertions prevail, since it is in this context that Korean and English differ in the grammatical encoding of discourse relations. Experiment 2 thus examines the production of continuations in a conversational setting, where the use of questions to encode an explanation continuation is possible. Our prediction was that Korean speakers would produce as many explanation continuations in this context as English speakers do, at least to the extent that their responses are in the form of questions.

3.1. method

3.1.1. Participants

20 English native speakers and 20 Korean native speakers were recruited in the same way as participants in Experiment 1.

3.1.2. Material and design

We reused the material we used in the free (or full-stop) continuation condition of Experiment 1, i.e., 48 sentence prompts for both English and Korean. English full-stop stimuli were exactly the same as those in Experiment 1. Korean full-stop stimuli differed minimally from the stimuli used in Experiment 1. We used the declarative marker -다(-ta), as shown in (11a), in Experiment 1, as it is commonly used in monologues, whereas we used the discourse marker -어(-e), as shown in (11b) in Experiment 2, as this marker sounds more natural in conversation. Differences in sentence-final markers did not change the meaning of prompt sentences.

In this experiment, stimulus sentences were followed by a blank line that prompted participants to respond as if they were taking part in a conversation between a hypothetical partner (Jessica in English; 지민 Chimin in Korean) and themselves (I in English; 나 na ‘I’ in Korean), as illustrated in (12).

Each participant saw all 48 experimental items and we collected 20 responses per experimental item, as in Experiment 1.

3.1.3. Procedure

We used the same procedure as in Experiment 1, although instructions were changed to reflect the difference in genre between Experiments 1 and 2. Participants were instructed to imagine that they were conversing with a close friend named Jessica/지민 Chimin and that they were asked to provide a response that made sense given what she said. The experiment took about 30–40 minutes (48 items per subject). It took a little less time per item for participants to produce continuations in Experiment 2 than in Experiment 1.

3.1.4. Data coding and analysis

Blank or incomprehensible responses were excluded (one for Korean and seven for English). All remaining trials (959 for Korean; 953 for English) were coded for the discourse relation between the response and the prompt sentence, explanation, result, or other, as illustrated in Table 1. As is expected of conversation, participants often responded with questions that asked for more information. Responses that asked about a cause or reason, e.g., Why?, What makes her do that?, etc., were coded as explanation and those that asked about a result or consequence, e.g., How did he respond?, Did he cry?, How did it turn out?, etc., were coded as result. Participants also used questions when suggesting a probable cause, e.g., Does she like him again?, Ben had another panic attack, did he?, etc. These questions were attempts by participants to ask for confirmation/agreement or attempts to more politely provide their own opinion. All question responses were coded as question and further coded as wh- or yes/no depending on the type of question.

We used mixed-effects logistic regressions to analyze responses, keeping all model settings the same as in Experiment 1. We first fitted a model that predicted an explanation continuation to the entire data of Experiment 2, i.e., explanation (1) or not (0, other or result). We then fitted the same dataset to a model that predicted a result continuation, i.e., result (1) or not (0, other or explanation). We also ran two post-hoc analyses. The goal of the first post-hoc analysis was to determine whether Korean and English speakers differ in their use of declarative vs. interrogative sentences when producing an explanation or result continuation. The goal of the second post-hoc analysis was to determine whether the Korean speakers in Experiment 2 produced less explanation responses than English speakers, just as Korean participants did in Experiment 1, when only declarative responses are included in the analysis.

3.2. results and discussion

Our hypothesis was that any effect of language on the production of explanation continuations would disappear in the context of a conversation. As predicted, there was no main effect of language on the production of an explanation continuation (b = –0.34, SE = 0.23, z = –1.46, p = .14) or the production of a result continuation (b = 1.25, SE = 0.72, z = 1.74, p = .08). We found a main effect of implicit causality on the likelihood of an explanation continuation (b = 1.56, SE = 0.26, z = 5.98, p < .001) as in Experiment 1, but not on the likelihood of a result continuation (b = 0.016, SE = 0.43, z = 0.037, p = .97). The latter results may indicate that implicit consequentiality does not affect the choice of continuation in conversations. Results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5. Fixed effects in the mixed-effect models for Experiment 2 (conversation)

notes: n=1912; language (English=0; Korean=1), implicit-causality (NIC=0; IC=1)

Formula: dr ~ language * implicit-causality + (1+implicit-causality|subject) + (1|item), Data: conversation

Overall, the results of Experiment 2 show that Korean speakers are as likely to produce an explanation continuation as English speakers are when they take part in a conversation. Figure 3 summarizes the results of Experiment 2.

Fig. 3. Summary of Experiment 2 (conversation).

The result of a post-hoc analysis that examined the form of participants’ responses showed that, as expected and summarized in Table 6, Korean speakers produced question responses far more frequently than English speakers for explanation (b = 2.13, SE = 0.54, z = 3.966, p < .001), but not for result continuations (b = 0.47, SE = 0.82, z = 0.58, p = .57). This result supports our contention that Korean speakers would take advantage of the availability of questions as follow-ups in conversation to convey explanations that they cannot easily convey through assertions, given the grammar of their language.

Table 6. Number of response forms in explanation and result continuations (conversation)

notes: Decl = declarative; Ques = questions; Y/N-Qs = yes/no-questions.

Finally, the results of a mixed-effect model which we fitted to the subset of the data that included only declarative responses (i.e., that excluded responses using question forms) showed that language was a significant predictor of declarative explanation continuations (b = –0.54, SE = 0.23, z = –2.31, p < .05), just as was the case in Experiment 1: Korean speakers produced fewer declarative explanation continuations in conversation than English speakers. The results of these last two models show that Korean speakers made up for the relative rarity of declarative explanation continuations by producing more interrogative explanation continuations than English speakers did. More importantly, these results suggest that upon reading the prompt sentence, Korean speakers expect an explanation continuation as much as English speakers do, and are prone to express equally frequently the cause of what they just read, but because the grammar of Korean discourages the expression of a backward causal relation in declarative form, they choose questions to express what they think best follows the prompt sentence.

4. Conclusion

This study set out to explore the possibility that a speaker’s grammar influences discourse production. Our investigation was based on the fact that Korean, but not English, clause linking makes it difficult to express an explanation relation when connecting two discourse segments via declarative clauses. The results of our two story continuation experiments revealed that, in monologues where most responses are declarative sentences, Korean speakers produce fewer explanation continuations than English speakers do, although both Korean and English speakersare equally sensitive to causally implicated events. In contrast, in a conversational discourse setting where speakers can produce interrogative as well as declarative explanation continuations, Korean and English speakers are equally likely to produce explanation continuations. Finally, our experiments showed that when a result relation is involved and the grammar of the two languages do not differentially constrain the explicit marking of that causal relation, speakers are equally likely to produce result continuations irrespective of discourse genres.

Taken together, the differences in the production of an explanation continuation and the similarities in the production of a result continuation across English and Korean support our hypothesis that grammatical constraints on the explicit conjoining of causally related clauses influence the way speakers construct monologues: language affected the way participants related an event description they read and an event description they produced when explanation was involved. Furthermore, sentences that contain implicit causality verbs increased the production of explanation continuations in both English and Korean, suggesting that putative differences in causal reasoning or sensitivity to causally implicated events are not the cause of observed differences in explanation continuations. Overall, our results across discourse relations (explanation vs. result) and discourse genres (monologue vs. conversation) provide converging evidence that Korean speakers produce less explanation continuations in monologues relative to English speakers because of differences in the grammar of their languages, not because of differences in their causal cognition or cultural/conceptual preferences for iconic descriptions of sequences of events. To our knowledge, our study is the first to show that differences in the grammar of languages can affect the processing of discourse relations.

Several factors influence speakers’ choice of one kind of continuation over another. Properties of the event described by the preceding sentence are one factor: this is why IC verbs lead to more explanation continuations (and to a lesser extent, to more result continuations). General preferences/dispositions for one kind of discourse relation over another is another factor in speakers’ choices: speakers may vary, everything being as equal as possible, in their preferences for particular discourse relations. These differences, we surmise, are partially the result of associations between events and the result of the speaker’s idiosyncratic narrative style, but they also result from exposure to other speakers’ discourses. Speakers have comprehended and produced many narrations, and the relative frequency of various discourse relations influences their preferences or dispositions: they know how a narration is typically supposed to unfold and their own narrations reflect this knowledge. It is this last source of preferences or dispositions for some continuations over others that the grammar of English and Korean affects. The grammar of Korean causes the backward order, effect and then cause, to be less frequent in discourses that Korean speakers have engaged in than in discourses that English speakers have engaged in, and this lower frequency reduces Korean speakers’ preference or disposition to expect and produce that order relative to English speakers: this is just not the way Korean narratives most naturally go.

If the mechanism we have just outlined for how grammatical differences affect discourse production is on the right track, it suggests that discourse structure is not a transparent window on event structure. Dery and Koenig (Reference Dery and Koenig2015) have shown that the temporal interval between described events is not just a reflection of how events unfold in real time but is mediated by speakers’ expectations about the granularity of the narration. The results of our Experiments 1 and 2 suggest that, similarly, expectations about what comes next in discourse partially reflect our past narrative and conversational experience and it is these expectations that can be shaped by the grammar of our language.

The genre-dependent differences we observed in the production of our Korean participants provide a few additional lessons, we believe, for the study of the interaction between grammar and discourse. First, it provides a cautionary tale for researchers who work with monolingual data. If one aims to measure the distribution of discourse relations in a language, drawing generalizations from a single discourse genre might be fraught with errors: measures might be very similar across monologues and conversations in some languages (e.g., English; Rohde, Reference Rohde2008), but may vary across these two genres in other languages, as our Korean data shows. Even for the same discourse genre, various other factors might affect the distribution of discourse relations, e.g., written vs. spoken language, degree of formality, social context, communicative purposes, and so on. In the current study, we used only written language, and the declarative marker we used in the Korean material belongs to a formal register. One may observe a different distribution of discourse relations in Korean monologues if colloquial or informal discourse markers are used or if spoken language is used. More detailed investigations into these additional potential effects of genre on the distribution of discourse relations across languages are needed.

Second, because the study of syntax is concerned with the rules that combine words and phrases within a single sentence, the influence of sentence-internal combinatorial rules on narrative discourse is easily missed. Kehler (Reference Kehler2002) showed that what was considered classic, sentence-internal syntactic phenomena such as VP-ellipsis, gapping, and extraction can be better understood when discourse coherence is taken into account. Conversely, the present study suggests that discourse phenomena may be better understood when the grammars of the languages under study are taken into consideration.

Lastly, our findings raise interesting questions regarding the development of discourse processing capabilities. Previous research has shown that young children are capable of causal reasoning and draw on many resources to make sense of real-world events (Hickling & Wellman, Reference Hickling and Wellman2001). But previous research has also shown that younger English-speaking children tend to make more mistakes in understanding backward causal relations expressed by because, as it runs counter to the order of events in the world, but have little difficulty understanding forward causal relations expressed by so (Bebout, Segalowitz, & White, Reference Bebout, Segalowitz and White1980; Lucia Reference Lucia1988). More generally, the age of acquisition of discourse relations varies with the complexity of the relation (Bloom, Lahey, Hood, Lifter, & Fiess, Reference Bloom, Lahey, Hood, Lifter and Fiess1980; Spooren & Sanders, Reference Spooren and Sanders2008), with less complex relations (e.g., additive, temporal, positive relations) being learned prior to more complex relations (e.g., causal, anti-temporal, negative relations). Given these findings, it is possible that young speakers of English are more similar to Korean adult speakers in their preference for result continuations over explanation continuations. We leave the study of this possible effect of cognitive development on discourse production to another venue.

Appendix

OIC items include object-biased implicit causality (IC) verbs; SIC items include subject-biased IC verbs; SIC1 and SIC2 differ in their syntactic structure in Korean (see Sections 2.1.2 and 3.1.2 for more detail); NIC items include non-IC verbs.