Introduction

The Battle of Gaugamela, which was fought in 331 B.C.E. between Macedonian and Greek forces under the command of Alexander the Great and the Persian army led by the Achaemenid King Darius III, has been called one of the most significant battles in the history of the world (Fig. 1).Footnote 2 In fact, its result brought about the effective collapse of the Achaemenid Empire – an empire that spanned two centuries and stretched from present-day India to Libya – and also led to the emergence of a new era, now widely known as the Hellenistic period. It was the Hellenistic period that generated the unprecedented interaction of Greek and ancient Near Eastern cultures, and as such established foundations for the cultural heritages of the Mediterranean and Middle East that, to a great extent, still exist today.

Fig. 1 General context of Macedonia and the Achaemenid empire in the time of Alexander the Great and Darius III

Notwithstanding the great importance of the Gaugamela battle, its precise location is far from certain. This situation is simply a result of the state of the extant historical sources, which do not provide us with precise topographical or geographical information and also very often contradict each other.Footnote 3 As a result, modern scholars have not come to a consensus on a single location for the battlefield of Gaugamela. As a matter of fact, all previous identifications have been formulated by European travelers and explorers from the eighteenth to the early twentieth centuries. Several sites have been proposed thus far as the location of ancient Gaugamela (Fig. 2): Karamleis,Footnote 4 Qaraqosh,Footnote 5 Tell Aswad,Footnote 6 (a mound south of) Wardak,Footnote 7 and Tell Gomel.Footnote 8 All of these identifications may be divided into two major groups on geographical and topographical grounds, because of their relative location towards Jebel Maqlub: the southern hypotheses and the northern hypotheses.Footnote 9 On the authority of renowned scholar Aurel Stein, Karamleis has become the most well-known identification of Gaugamela south of Jebel Maqlub.Footnote 10 In contrast, Tell Gomel is the only site located north of Jebel Maqlub that has been associated with the famous battlefield. Consequently, for many decades scholars opted for only one of these identifications – either the Karamleis areaFootnote 11 or the Tell Gomel region.Footnote 12

Fig. 2 Geographical and topographical context, including the limits of the survey permit area of LoNAP, marked by the polygonal line

However, past identifications have not been based on detailed research. Importantly, most modern scholars have never had the chance to verify these identifications ‘on the ground’ because of the unstable political conditions that have marked this part of the Middle East in the past. However, the recent period of relative security and stability in the autonomous region of Kurdistan in Iraq has led to the breaking of a new dawn for Near Eastern archaeology.Footnote 13 Many international teams began their research in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq in 2011, and new teams have been arriving every year since. One of these archaeological teams is the Land of Nineveh Archaeological Project (hereafter LoNAP), which started in 2012.Footnote 14 The project explored an area of 3000 km2 in the province of Dohuk by means of archaeological survey and selected excavations (Fig. 2). The survey permit area of LoNAP includes the site of Gir-e Gomel (Tell Gomel). The Gaugamela Project was launched in this context in 2018 (preceded by a short reconnaissance in 2016), and its specific aim has been to identify the location of the Battle of Gaugamela (331 B.C.E.) using a well-known approach correlating the methods of ancient history and various techniques often classified under the name of landscape archaeology. Similarly, in 2011 another archaeological team from the University of Athens undertook an attempt at shedding more light on the identification of Gaugamela. As a result, K. Zouboulakis revived and strongly advocated the identification of Qaraqosh with Gaugamela, which was first suggested by Sushko (Reference Sushko1936).Footnote 15

This study is devoted to one of several specific questions, all of which must be answered before the final identification of Gaugamela can be made. Namely, according to two ancient sources, Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, 3.9.2–3Footnote 16, and Quintus Curtius Rufus, Histories of Alexander the Great, 4.12.15–24Footnote 17, on the eve of the battle the approaching Macedonian army and the Persian troops that were waiting on the battlefield could not see each other because of intervening hills at a distance of c. 12 km (60 stades). However, the two armies gained a full view of their respective positions once the Macedonians reached the hills c. six km away from the Persian positions (30 stades). The co-appearance of this ‘visibility’ motif in both Arrian and Curtius is very striking, as the two sources come from different literary traditions. In the absence of contemporary sources on Alexander the Great (all writings of Alexander's historians are not extant), Arrian's work, though written only in the first half of the second century C.E., enjoys a particular recognition among modern historians because it is based on eye-witness accounts of Alexander's Persian campaign (in particular, those of Ptolemy and Aristobulos). In turn, Curtius, writing in the first century C.E., is mainly based on Cleitarchus, whose work (now lost) was probably written in the late fourth century B.C.E. and became very popular (and consequently followed) in antiquity. Nevertheless, Cleitarchus was often criticized for being unreliable by other ancient writers, and this is believed to have been one of the reasons why Arrian turned to other sources in his Anabasis. This co-appearance definitely enhances the historical credibility of the ‘visibility’ motif.

While visibility can be checked on the ground, modern methods used in Geographic Information Systems (hereafter GIS) offer a number of tools that allow for objective testing of the visibility between two or more chosen points, including measurement of the visible area. GIS visibility tools are not terra incognita for archaeologists and historians. They have particularly been used to speculate about factors influencing settlement and monument location (e.g., viewsheds showing a settlement's defensibility and control over economic hinterland; intervisibility of military structures; intervisibility of routes, landmarks and settlements).Footnote 18 Importantly, it should be stressed that the use of GIS visibility tools may even be the only way to conduct research in areas that cannot currently be accessed by scholars for security reasons. This has been the case for the southern identification of Gaugamela in recent decades because of its proximity to Mosul,Footnote 19 unlike the Tell Gomel area, which members of LoNAP have been able to inspect since 2012. In this light, the aim of this paper is to test visibility for the three most significant identifications of ancient Gaugamela – Karamleis, Qaraqosh, and Tell Gomel.

GIS methodology

ArcGIS,Footnote 20 with its viewshed analysis tool, was chosen as the software for our analyses.Footnote 21 Performed on the raster model, viewshed analysis determines which raster cells are visible from the selected viewpoint and which cells are not visible. Viewshed analysis includes both qualitative (indication of areas seen and unseen with the attribution of values 1 and 0, respectively) and quantitative (measurement of surface) information. A digital elevation model (hereafter DEM) plays a fundamental role in viewshed analysis.Footnote 22 Generally speaking, a DEM is a continuous digital representation of a terrain's surface resulting from interpolation of the source data to numerical form.Footnote 23 Several methods may be used to create DEMs, including ground measurements, digitization of topographic maps, photogrammetric surveys, laser scanning (especially LiDAR) and radar interferometry.Footnote 24 However, direct field surveys and use of some of the most up-to-date techniques (LiDAR in particular) are difficult or even impossible in many regions of the Middle East, in most cases because of the political situation.Footnote 25 In this context, the DEMs widely used in geosciences and archaeology of the Middle East are global open-source DEMs. Although there are currently several freely available DEMs on a global scale,Footnote 26 the two DEMs with long-established traditions of use in geosciences and archaeology are SRTM (Shuttle Radar Topography Mission) and ASTER (Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer).Footnote 27 Given the results of methodological research on their accuracy,Footnote 28 we decided to use the two latest versions of these datasets with the same resolution and coverage: SRTMGL1 (Shuttle Radar Topography Mission Version 3 Global 1 Arc-Second) and ASTER GDEM2 (Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer Global Digital Elevation Model Version 2) to avoid possible distortion of our results due to the subjective choice of only one input material.

The SRTMGL1 DEM used in this study is the result of radar interferometry from Earth's orbit created by the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission.Footnote 29 The mission was carried out in 2000 by the space agencies of the USA (NASA), Germany (DLR), and Italy (ASI). In turn, the ASTER GDEM2 is the result of a joint mission of Japan's Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) and NASA. It is based on several optical subsystems that have been operating on NASA's Terra satellite since 1999.Footnote 30 These DEMs, with a spatial resolution of about 30 m, are available in the form of tiles with dimensions of 1 × 1 degrees in the WGS84 system from EarthExplorer, the data portal of the United States Geological Survey (USGS): https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ (accessed April 1, 2021).

Control points for viewshed analysis were obtained from a visual interpretation of available satellite images on the Google Earth Pro and ArcMap software in the WGS84 geographical system. The choice of specific control points strictly followed the authors of given historical identifications (Stein Reference Stein1942; Sushko Reference Sushko1936) for the Mosul region (Karamleis and Qaraqosh). In the case of the Tell Gomel area, the control points are the result of fieldwork carried out in 2016 and 2018. The following features were applied to the control points: name, latitude, longitude, OFFSETA. For latitude and longitude, the WGS84 was used. The OFFSETA option in ArcGIS 10 is used to establish the height of the observation point relative to the DEM. In our case, a value of 2.5 m, corresponding to the height of a rider on a horse, was chosen. Finally, our data was transformed into an (Asia) Lambert Conformal Conic projection.

Topography of the Battle of Gaugamela according to Stein and Sushko

According to Aurel Stein, the center of the Persian army was located in Karamleis (and included the “high mound close to Karamleis”),Footnote 31 the left wing was located near Qaraqosh, and the right wing reached the foothills of ‘Ain-as-Satrah.Footnote 32 In Stein's view, the Macedonians first made eye contact with the Persian troops around the present-day town of Minarah Shebek.Footnote 33 The hills that kept the two armies from seeing each other from a distance of 60 stades are described by Stein as an “outlier of the hill chain which stretches … from the left bank of the Tigris towards the northern extremity of the plain near the village of Bartallah.”Footnote 34 Stein also pointed to Abu Wajnam as the location of the Macedonians’ Tigris crossingFootnote 35 but did not suggest a precise route for their approach between Abu Wajnam and Minarah Shebek. However, it appears that he intended to indicate that the direction of the Macedonian approach was western or northwestern (“any position in a fold of lower ground north of that outlier was not visible from Karamleis [at a distance of 12 km]”).

Making the best of Stein's descriptions, the following locations have been chosen for viewshed analysis (Fig. 3):

-

Location 1: The center of the Persian army at 36°18′24.63″N, 43°24′25.27″E (36.306842, 43.407019), in the vicinity of the modern town of Karamleis.

-

Location 2: The left wing of the Persian army at 36°16′46.2″N, 43°21′50.2″E (36.279508, 43.363956), in the vicinity of the modern town of Bakhdida (Qaraqosh).

-

Location 3: The right wing of the Persian army at 36°20′52.14″N, 43°26′30.36″E (36.347817, 43.441767), at the foothills of ʿAin-as-Satrah.

-

Location 4: The final Macedonian camp at 36°18′50.3″N, 43°20′15.7″E (36.313964, 43.337694), in the vicinity of Minarah Shebek, at a distance of c. 6 km from Karamleis.

-

Location 5: Position no. 1 of the approaching Macedonian army at 36°23′02.9″N, 43°18′50.7″E (36.384131, 43.314075), northwest of Bazwaia at a distance of c. 6 km from Minarah Shebek and c. 12 km from Karamleis.

-

Location 6: Position no. 2 of the approaching Macedonian army at 36°20′08.4″N, 43°16′01.9″E (36.335656, 43.267206), at a distance of c. 6 km from Minarah Shebek and c. 12 km from Karamleis.

Fig. 3 All control points for the viewshed analysis and the geographical context of northern Iraq

It should be noted that the mapping of Locations 3, 5, and 6 is, to a great extent, speculative because Stein did not point to precise locations in this regard. In mapping Locations 5 and 6, we have offered two alternative locations for the approach from the northwest and west, respectively. The choice of both positions followed the most important requirements of the ancient sources (distance of c. 6 km from the Macedonian camp and c. 12 km from the center of the Persian army). Location 5 is located approximately along Stein's identification of the old caravan route coming from the Mosul Dam area (and from the crossing points of the Tigris at Cizre, Feshkhabur, Abu Dhahir, and Abu Wajnam). Location 6 is situated on the southeastern fringes of modern Mosul and as such could be located along the line of the Macedonian approach if Alexander's army would have been coming from the Tigris crossing at Eski Mosul or Mosul.

The first analysis shows the total area of visibility of the two armies in their final positions (Figs. 4–5; Locations 1–3 occupied by the Persian army in Karamleis, Qaraqosh, and at the foot of ʿAin-as-Satrah, and Location 4 occupied by the Macedonian army at their final camp).

Fig. 4 Maps 01–04, Viewsheds of Locations 01–04: SRTMGL1

Fig. 5 Maps 01–04, Viewsheds of Locations 01–04: ASTER GDEM2

Visibility from the Persian positions at the center at Karamleis (Figs. 4–5, Map 1: Viewshed of Location 1) and the left wing (Figs. 4–5, Map 2: Viewshed of Location 2) does not reach the position of the final Macedonian camp (Location 4). The same can be said about the visibility from the final Macedonian camp at Minarah Shebek (Fig. 4–5, Map 4: Viewshed of Location 4) – the Persian positions at the center and the left wing cannot be seen at all. At the same time, very good visibility can be achieved from the Persian right wing (Figs. 4–5, Map 3: Viewshed of Location 3), and this position is also visible from the final Macedonian camp (Figs. 4–5, Map 4: Viewshed of Location 4). Location 3 at the foothills of ʿAin-as-Satrah is, however, highly controversial because it is situated on slightly raised terrain. As noted above, Stein was not precise about the location of the Persian right wing but only mentioned the general area. In contrast, the ancient sources emphasize that the Persian army was set up on uniformly level ground (Arrian 3.8.7, 3.13.2Footnote 36; Curtius 4.9.10Footnote 37). Therefore, placing any control point near ʿAin-as-Satrah is problematic, as it would essentially be contrary to the testimony of the ancient sources. Finally, it can be said that no differences that are significant for evaluation of the historical reconstruction can be observed between SRTMGL1 and ASTER GDEM2 (compare Fig. 4 and Fig. 5), although the viewshed area of SRTMGL1 is larger.

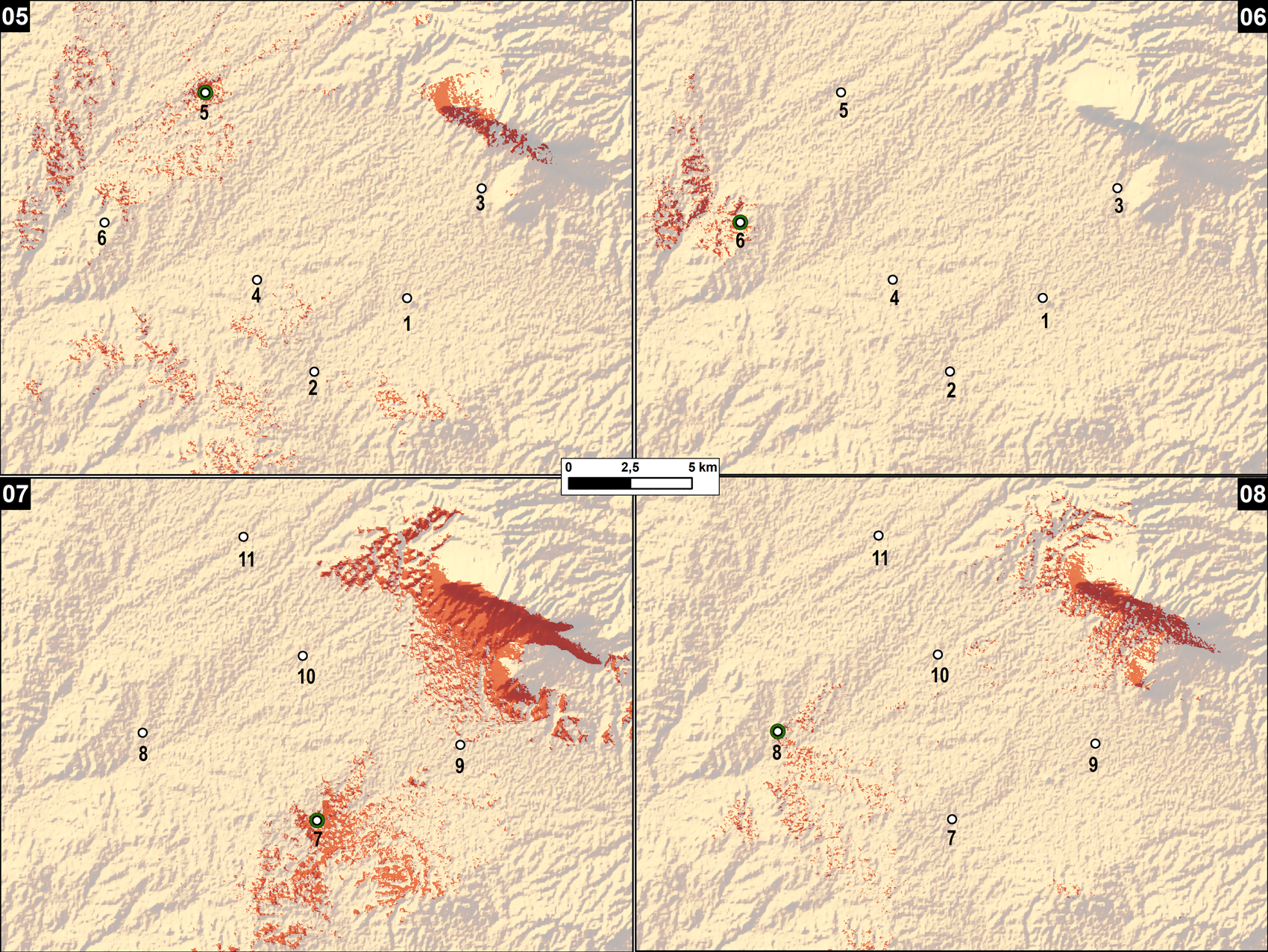

The second analysis (see Figs. 6–7, Maps 5–6) shows the viewshed areas of the Macedonian army at a distance of 12 km from the Persian positions. At that moment, the Macedonian army was approaching the battlefield and the Persians were awaiting the enemy in their final positions.

Fig. 6 Maps 05–08, Viewsheds of Locations 05–08: SRTMGL1

Fig. 7 Maps 05–08, Viewsheds of Locations 05–08: ASTER GDEM2

Indeed, there is no visibility from the Macedonian positions towards the Persian final positions (see Figs. 6–7, Maps 5–6: Viewsheds of Locations 5–6). However, it should be noted that from the Persian position at the right wing (see Fig. 4–5, Map 3: Viewshed of Location 3), Macedonian Location 5 (if the Macedonians would have been advancing from Mosul or Eski Mosul) could be seen, but not Macedonian Location 6 (which matches the more likely direction of the Macedonian advance from the Mosul Dam area, including fords at Abu Wajnam and Abu Dhahir). These results of our analysis are in line with the testimony of the ancient sources, if the Macedonian advance is understood as taking place from the Mosul Dam area.

All in all, it should be stressed that Stein's reconstruction of the deployment of the Macedonian and Persian troops is historically incorrect as far as the question of visibility on the battlefield is concerned. There is essentially no mutual visibility between the position of the final Macedonian camp at Minarah Shebek and the Persian center and left-wing positions at Karamleis and Qaraqosh.

A very detailed reconstruction of the Battle of Gaugamela on the Karamleis plain comes from Alexander Sushko, who, however, formulated his hypothesis without on-site examination. The cornerstone of his reconstruction was the linguistic identification of Qaraqosh with Gaugamela (with Qaraqosh meaning black bird in Turkish, and Gaugamela – corrected to Kaukamēla – also meaning black bird).Footnote 38 This identification has recently been revived and strongly advocated by Zouboulakis.Footnote 39

According to Sushko, the deployment of the Persian army resembled a serpentine line with three main positions: the center in Qaraqosh, the right wing in Karamleis, and the left wing near the village of Ta(h)rava.Footnote 40 What is more, Sushko also published a sketch map for the main sites (Fig. 8).Footnote 41 He placed the Macedonian positions on the map in a very detailed way – the final camp between the towns of Hazna and Börtella, and the camp from which the Macedonians reached the battlefield at Hussein Ferrash. Sushko's locations are easy to identify because they use local names.

Fig. 8 Sushko's sketch map of the deployment of the Macedonian and Persian troops (after Sushko Reference Sushko1936: 69)

Following Sushko's sketch map, the following locations have been chosen for viewshed analysis (Fig. 3):

-

Location 7: The center of the Persian army in the vicinity of the modern town of Qaraqosh, at 36°17′24.8″N, 43°21′54.1″E (36.290214, 43.365019).

-

Location 8: The left wing of the Persian army in the vicinity of the modern town of Ta(h)rava, at 36°19′24.2″N, 43°17′04.6″E (36.323392, 43.284619).

-

Location 9: The right wing of the Persian army in the vicinity of the modern town of Karamleis, at 36°19′05.7″N, 43°25′53.3″E (36.318250, 43.431483).

-

Location 10: The final Macedonian camp between the towns of Hazna and Börtella, at 36°21′06.9″N, 43°21′31.7″E (36.351906, 43.358808).

-

Location 11: Observation point of the Macedonian army while approaching the Persian position at a distance of c. 12 km from Qaraqosh, at 36°23′47.7″N, 43°19′53.7″E (36.396589, 43.331572).

The first issue to consider is the visibility between the Persian positions and the position of the final Macedonian camp. Our analysis using SRTMGL1 as the input DEM (the ASTER GDEM2 produces worse results; see Figs. 6–7, Map 8: Viewshed of Location 8) shows that the final Macedonian camp could clearly be seen from the Persian left wing, but not from the Persian centre (Figs. 6–7, Map 7: Viewshed of Location 7) or the Persian right wing (Figs. 9–10, Map 9: Viewshed of Location 9). At the same time, there is good visibility from the final Macedonian camp towards the Persian positions at the left wing and centre, but not towards the right wing (however, better results are obtained for SRTMGL1 than ASTER GDEM2; see Figs. 9–10, Map 10: Viewshed of Location 10). Concerning the visibility at the moment of the Macedonian approach at a distance of c. 12 km from the final Persian positions, the Macedonian army (Figs. 9–10, Map 11: Viewshed of Location 11) and the Persian army (see Figs. 6–7, Maps 7–8 and Figs. 9–10, Map 9) could not see each other.

Fig. 9 Maps 09–11, Viewsheds of Locations 09–11: SRTMGL1

Fig. 10 Maps 09–11, Viewsheds of Locations 09–11: ASTER GDEM2

The viewshed analysis for Sushko's reconstruction of the Macedonian and Persian army deployments shows better results in terms of visibility than Stein's reconstruction. However, these results are still far from satisfactory, as they indicate limited visibility for the two armies in their final positions. No arguments in favour of the historical identification of Sushko can be made based on the differences between SRTMGL1 and ASTER GDEM2. Even the slightly larger viewshed areas of SRTMGL1 (especially the viewshed of Location 10) are not good enough to make the case for Sushko's reconstruction to be consistent with the visibility requirements of the ancient sources.

The identification of the Battle of Gaugamela in the Navkur plain near Tell Gomel was first suggested for onomastic reasons. The name (Tell) Gomel can be considered a remnant of the ancient name of Gaugamela.Footnote 42 Tell Gomel is located on the west bank of the Gomel River and almost at the center of the Navkur plain.Footnote 43 The area most suitable for the deployment of large forces, especially cavalry, can be found west of Tell Gomel in the western part of the Navkur plain, and as such is clearly delimitated by natural features: the Gomel River in the east, the prominent outcrop of Jebel Maqlub in the south, and the line of the Zagros foothills in the north (see Fig. 3).

The mapping of the following control points is a result of recent fieldwork undertaken in 2018:Footnote 44

-

Location 12: This point was chosen at a distance of 6 km from the Mahad Hills, at 36°39′17.3″N, 43°19′23.6″E (36.654794, 43.323228). It is located on the line of all least cost paths leading to Tell Gomel from the vicinity of the Mosul Dam.Footnote 45

-

Locations 13 and 14: The positions of the Persian army were situated at a distance of 6 km east of the Mahad Hills. At the same time, the positions are 2–3 km away from the Khazir River, which appears to be necessary to allow enough space for the deployment of the depth of the Persian army and the management of military resources. Additionally, Tell Gomel is marked at 36°35′35.6″N, 43°28′31.9″E (36.593219, 43.475517) for orientation.

Location 15: The final Macedonian camp was placed on the Mahad Hills at a distance of c. 6 km from both Locations 13 and 14, at 36°38′00.8″N, 43°23′50.9″E (36.633562, 43.397471).

The first question is the visibility between the two armies at a distance of 12 km, with the Macedonian army on their way and the Persians awaiting the enemy in their final positions. Our analysis shows a total lack of visibility from both the Macedonian positions (Figs. 11–12, Map 12: Viewshed of Location 12) and the Persian positions (Figs. 11–12, Map 13: Viewshed of Location 13 and Figs. 11–12, Map 14: Viewshed of Location 14). The lack of visibility is clearly a result of the existence of the elevation between the two armies. It is also clear that the final Macedonian camp on the hills (Location 15) was clearly seen from the final Persian positions (Figs. 11–12, Map 13: Viewshed of Location 13 and Figs. 11–12, Map 14: Viewshed of Location 14).Footnote 46 From the hills, the Macedonians had a vast commanding view of the Navkur plain, including the Persian positions (Figs. 11–12, Map 15: Viewshed of Location 15).

Fig. 11 Maps 12–15, Viewsheds of Locations 12–15 in the Navkur Plain: SRTMGL1

Fig. 12 Maps 12–15, Viewsheds of Locations 12–15 in the Navkur Plain: ASTER GDEM2

The results of the viewshed analysis clearly show that the location of the Battle of Gaugamela in the vicinity of Tell Gomel displays very good visibility in terms of topographic features: mutual visibility was achieved for the two armies only after the Macedonian army reached the hills, and, in agreement with the testimony of the ancient sources, the visibility was good.

In conclusion, in this study a GIS method known as viewshed has been employed to solve a certain historical problem. According to ancient sources, on the eve of the Battle of Gaugamela the approaching Macedonian army and the Persian troops that were waiting on the battlefield could not see each other because of intervening hills at a distance of c. twelve km. However, the two armies gained a full view of their respective positions once the Macedonians reached the hills c. six km away from the Persian positions. Our analysis shows that the identification of the battlefield near Tell Gomel is consistent with the visibility requirements of the ancient sources, while the previous identifications of the battlefield in the vicinity of Karamleis and Qaraqosh (Stein Reference Stein1942; Sushko Reference Sushko1936; Zouboulakis Reference Zouboulakis2015, Reference Zouboulakis, Kopanias and McGinnis2016) feature poor results in terms of expected visibility.

This case study also allows a few methodological conclusions about the qualities of SRTMGL1 and ASTER GDEM2 in our study area. First, essentially the same results of the viewshed analysis are obtained for both historical reconstructions, regardless of the input DEM (SRTMGL1 or ASTER GDEM2): the identification of the Gaugamela battlefield near Tell Gomel is consistent with the visibility requirements of the ancient sources, while the identifications of the battlefield in the vicinity of Karamleis and Qaraqosh feature poor results in this regard. Second, in our study area, SRTMGL1 has, in general, higher elevations than ASTER GDEM2 and as such produces a larger viewshed area than its counterpart (remarkably, the viewshed area is still considerably smaller even for those locations in ASTER GDEM2 that have higher elevations than in SRTMGL1). Third, although ASTER GDEM2 has a slightly higher spatial resolution (27.8 x 27.8m), it includes noise (minor errors) that worsens the results of computational experiments.