Introduction

Punctuating the rhythm of historical buildings on the main approach from Belgrade’s train station, lies a gate-like structure of two destroyed modernist towers of brick and marble. The twin ruins of the former General Staff of the Yugoslav Army and the Ministry of Defense of Yugoslavia (referred to together as the Generalštab) have been much photographed and debated in the years after the NATO bombings of 1999 (Figure 1). Some Belgraders shrug and say that there is simply no money for the rebuilding of the two buildings. In 2013, however, the Ministry of Defense of Serbia announced that an investor from the Emirates would take over the ruins and build a luxury hotel on the prime location (Balkan Insight). In late 2016, the prime minister of Serbia stated that the building should be cleared to make room for a monument of medieval ruler Stefan Nemanja (Blic 2016). Yet for some local architects, the ruined structure should not even be considered for rebuilding; for instance, according to Milica,Footnote 1 aged 15 at the time of the bombings and at the time of writing a practicing architect, “the ruins should be kept as ruins, they are like a monument to the months of bombing and suffering of people of Belgrade.”Footnote 2 The memorialization of ruins on the one side, and the proposal for a clearing of the site followed by lucrative new construction on the other, are just two ends of a continuum of imaginations for the fate of the ruined Generalštab. This article will explore the relationship between approaches and debates surrounding ruins which resulted from the 1999 NATO bombings and the collective memories of the events, scrutinizing the role of ruins and reconstructions to embody, sustain, and engender memory on personal and societal levels.

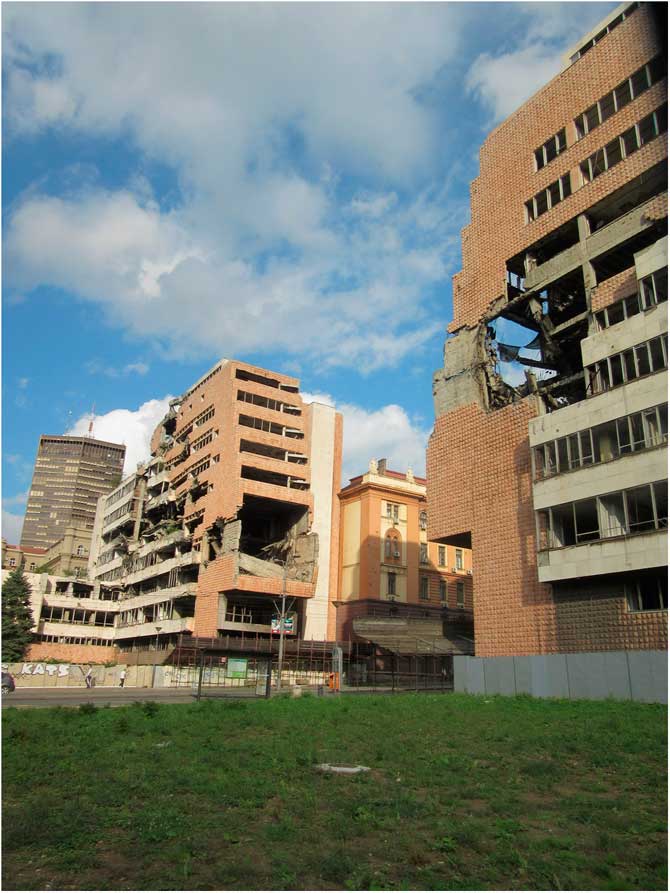

Figure 1 The Generalštab (General Staff) complex, consisting of the Yugoslav Army Headquarters and the Federal Ministry of Defense, destroyed in 1999 by the NATO bombings.

The relationship with the recent past in Serbia has been generally discussed with regards to state practices and cooperation with the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) (Subotić Reference Subotić2009), as well as narratives of denial (Dimitrijevic Reference Dimitrijevic2008; Obradovic-Wochnik Reference Obradovic-Wochnik2013; Gordy Reference Gordy2013), and of (self)-victimization (MacDonald Reference MacDonald2002; Žarkov Reference Žarkov2007). More recently, there has been increasing attention on the reshaping of cultural practices and national symbols in relationship to the recent wars (Lazic Reference Lazic2013; McLeod, Dimitrijević, and Rakočević Reference McLeod, Dimitrijević and Rakočević2014; Fridman Reference Fridman2015; David Reference David2015a), as well as on processes of memorialization and commemoration (David Reference David2014, Reference David2015b). Nevertheless, the relationship between urban space and the memory of the wars has not yet been directly addressed. While David (Reference David2014) fruitfully discussed the monument to the fallen of the wars of the 1990s as a site of “mnemonic battles,” her aim was to investigate the mediation of international and domestic demands rather than discuss the monument in relationship to space, memory, and city. In contrast, this article examines the collective memory and narratives of the 1999 NATO bombings from a spatial lens, examining the relationship between urban space and memorial engagements with the recent past of the Yugoslav wars.

Shifting scales from the nation to the locality of the city contributes to furthering our understanding of how collective memories are reassembled and relate to the emergence of different, complex canvases of identity. Cities have long been arenas of political struggle, with conflict being at the core of the urban condition (Pullan and Baillie Reference Pullan and Baillie2013), targets and battlegrounds of war and political violence (Bogdanović Reference Bogdanović1993; Graham Reference Graham2004; Coward Reference Coward2009,), as well as places of resistance and resilience (Jansen Reference Jansen2001). Consequently, they can be analyzed as specific situations of collective memory formation and memory practices. Discussing the collective memory of political violence and conflict in relationship to cities can be treated, on the one hand, as a “classical” exploration of collective memory in the realm of urban populations. Yet, the city and its built environment are not only stages of enacting memory, the Halbwachsian (Reference Halbwachs and Coser1992) cadre matériel in which memories are embedded, as urban space could also be seen as a mnemonic device itself, even an actor in the process of shaping memory. It is the latter approach that this article will take, in investigating how architects debate the reshaping of urban space after conflict and how the urban space itself relates to collective memory and expresses national memory narratives.

I will examine how, through the process of approaching ruins in reshaping the city after political violence and conflict, city makers participate—intentionally or not—in the act of reconfiguring collective memories and ideas of the nation. Furthermore, I will examine how urban space, and especially ruins, relate as mnemonic and affective devices to the reshaping of collective memories and national identities. I distinguish between collective memory as a remembered lived experience of a group (Halbwachs Reference Halbwachs1980) and official memory narratives, which are a carefully assembled collection of memory events with political reasoning and significance (Assmann Reference Assmann2006). Specifically, I examine architects and city makers as mediators of collective memories and state politics of memory, and the city as an arena of spatial manifestation of different memory narratives as well as an actor of memory making. Therefore, I shift the scale from the national to the urban, and from “classical” memory entrepreneurs from the political realm to city makers, usually perceived as “technical” actors. Consequently, the article aims to respond to the call of Forest, Johnson, and Till (Reference Forest, Juliet and Till2004) for studies of memory to move beyond the political elite versus general public dichotomy by exploring the multiplicity of agendas and negotiations of processes of remembering the past as well as reshaping national identity. Furthermore, through the analysis of space as a discursive object and representation, this article aims to follow up to Wulf Kansteiner’s observation (Reference Kansteiner2006, 27) that “we have to further collective memory studies by focusing on the communications among memory makers, memory users, and the visual and discursive objects and traditions of representations.”

By discussing the ruined Generalštab complex in Belgrade and the visions for its reconstruction, the article will problematize how urban reconstruction, collective memory, and national identities reinforce each other. To do so, I will first explore the relationships between urban space and collective memory, focusing on how memories of violence have been conceptualized in relation to urban space and architecture, how ruins have been connected to memory and national identity through a repertoire of interpretative frames, and how the practice of memorial architecture has increasingly become a significant presence in cities. Further, I will examine how city makers in Belgrade select and reassemble spatialized collective memories through capitalizing on the violent past in order to create and disseminate novel forms of identity in the process of reconstruction. To do so, I will examine the landscape of ruins on display in Belgrade, focusing on the debates surrounding the Generalštab, brought about by architects, NGOs, and authorities. I analyze the variety of narrative frames that these actors put forward about the building, the ruin, its state of waiting, and the reconstruction possibilities, revisiting as such the relationship between urban space, collective memory, and visions of national identity.

Collective Memories of Political Violence and the Urban

Through its “enduringness of materials” (Ricoeur Reference Ricoeur, Kathleen and Pellauer2004, 150), urban space is a mediator between events and memory (Halbwachs Reference Halbwachs and Coser1992; Bakshi Reference Bakshi2012, Reference Bakshi2014). In contexts of political violence, urban space can be a subject of violence itself—through its physical destruction—and/or the stage of human suffering, including acts of killing, kidnappings, torture or rape, or famine and deprivation. Urban space becomes in both cases a mnemonic device for memories of political violence. Andrew Herscher (Reference Herscher2010) argued for a more nuanced understanding of architecture in relationship to violence, opposing the view of architecture as just a “product, effect, expression or mediation.” For him, the destruction of cities becomes, a “semantically modal and transformative practice that constructs novel poles of enactment and reception” (Herscher Reference Herscher2010, 4). This triggers the question on whether urban space is itself an actor in shaping collective memory and political emotions. For some approaches like actor-network theory, things, including architectural objects and ruins, have agency of their own (Latour Reference Latour2005). According to affect theory, encounters with such ruins could engender affect (Thrift Reference Thrift2008). The anthropological work of Yael Navaro-Yashin (Reference Navaro-Yashin2009,), Soumhya Venkatesan (Reference Venkatesan2009), and Stef Jansen (Reference Jansen2013) reconciles place-, things- and people-centered approaches: materiality is communicative, but only in relationship to the people interacting with it. I examine architectural ruins in the postwar city in this latter framework, thus discussing urban space as an arena of memory which needs to be mediated with the subjective experience of the viewer.

The memorial dimension of space can be instrumentalized. Political power and institutions reshape how collective memories are expressed in the built environment, by selecting what to commemorate or ignore, including for instance which memorials to build or which heritage buildings to renovate (Lowenthal Reference Lowenthal1985; Hillier Reference Hillier1998; Sandercock Reference Sandercock1998; Hoelscher and Alderman Reference Hoelscher and Aldermann2004). While some of these decisions and policies come from the state level, the analysis of local dynamics and actors gives a more nuanced understanding of the spatialization of memory. The agency of local city makers can at times be in sharp contrast with national policy or top down memory narratives in the local planning and architectural interventions (Fenster Reference Fenster2004). A triad of memory-agents develops, all in relationship to local communities and their collective memory: architecture/urban space, which embodies and encapsulates memory; states, with their official narratives; and local level city makers, including architects who, intentionally or not, modify space and thus alter its mnemonic qualities. The interventions in urban space are then interpreted by communities and individuals and participate in the (re)shaping of collective memory.

Ruins as Mediators of Memory and National Identity

As visible testimonies of destruction, ruins have been viewed as depositories of memory and have often sustained national narratives. As mnemonic devices, ruins have fascinated Europe for centuries, with Roman ruins in particular as remnants of a grand past and of a spectacular decay and fall (Huyssen Reference Huyssen2006). The Romantic movement aestheticized ruins and even gave birth to a fashion of placing artificial ruins in gardens and landscapes of the picturesque (Andrews Reference Andrews1989). Artificial ruins have become important ingredients in landscapes related to national identity, such as the English garden (Janowitz Reference Janowitz1990). Enduring or rediscovered, through archaeological work, ruins of the past sustained national identities and national narratives marking pasts of glory (eg. Greece) or suffering (Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2007). This aestheticization of ruins continued to some extent even after the large scale destruction of cities during World War II (Elżanowski Reference Elzanowski2010). Hempel, a Dresden art historian, for instance, discussed the need to preserve post-World War II ruins as aesthetic and mnemonic devices alike: “Some parts of our inner cities will resemble the Roman Forum. Piously treasured ruins could also bear witness to the greatness of the past” (Hempel 1948, in Elzanowski Reference Elzanowski2010). Ruins continued to also sustain national identity narratives and were mobilized as such through photography and cinema (Moeller Reference Moeller2014). The so-called authenticity of ruins as testimony became at times a fetish, with authorities promoting an “arrested decay” of ruins in order to keep them as convenient markers of time with a political but also a commodified role, as DeLyser (Reference DeLyser1999) shows through her study of preserving ruins for tourism in the American West.

Ruins, however, do not solely serve the role to fixate memory, as they are both ephemeral and ambiguous (Huyssen Reference Huyssen2003). On the one hand, ruination becomes a metaphor for human memory itself, erodible and unpredictable. According to Kathleen Stewart (Reference Stewart1996), ruins are an “embodiment of the process of remembering itself,” (93), as some parts of the past remain, while others disappear. On the other hand, the disjointed fragments and traces of ruins are hard to weave in a coherent narrative (Edensor Reference Edensor2005), thus ruins are in their essence ambiguous (Huyssen Reference Huyssen2006), as their disjointed fragments and traces are hard to weave in a coherent narrative (Edensor Reference Edensor2005). They can be read and interpreted in multiple ways, related to the frame of references of the readers. Furthermore, according to Ann Stoler (Reference Stoler2008), the memorial role of ruins is not intrinsically connected to their often monumental or remarkable physicality, but to the ways people make sense of what they lost and what they still have. Ruins therefore cannot be seen as depositories of monolithic collective memories which engender similar, homogenous reactions in the viewers.

Memorial Architecture

The Memorial Church in West Berlin, in which a modernist new structure was juxtaposed with the ruin of the Kaiser Wilhelm church, destroyed in World War II, revealed the potentiality of architects to engage with memory work in rebuilding or, working around, ruins (Ladd Reference Ladd1998). The involvement of architects in memory work has been highlighted by the emergence of a wave of memorial architecture, sparked by Maya Lin’s Vietnam Memorial in Washington, DC. The latter signified a departure from traditional sculptural memorials, as its structure, a deep cut in the ground listing names of the fallen, had an impact on space and landscape that was considered a breakthrough at the time, not without controversy (Kelly Reference Kelly1996). Architects had already had a prime role in designing Holocaust memorials (Young Reference Young1993), but also in the emerging counter monument movement, which involves visitors, who are expected to participate actively in the memorial event (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2003).

The reception of such memorial architecture has been diverse. Karen Till (Reference Till1999) for instance showed how resistance to the redesigned memorial of the Neue Wache in Berlin led to a debate of the interpretation of history and the production of national collective memory in Germany. Similarly, Forest, and Johnson (2011) analyzed the shifting interpretation and continuous struggles over memorials in the former Soviet Union. Scholarship on Holocaust memorials and 9/11 memorials has been also abundant. Most of this work, however, was concentrated on new memorial architecture projects or existing monuments, and not on cases of memorial engagement through design of ruins and processes of reconstruction, which this article directly examines.

Methodology

This article builds on fieldwork conducted in Belgrade over a total period of nine months between 2012 and 2015, which included archival research, semi-structured interviews, as well as an immersion in city spaces, everyday life, and interactions through participant observation. Specifically, I explored, photographed, and mapped a variety of places in Belgrade, with a particular focus on the sites and ruins of the NATO bombing. In the Belgrade City Archive, I researched the biography of the bombed buildings, as well as the media coverage of the 1999 bombings between March and August of that year in the leading daily newspapers Politika and Danas. For later coverage of the reconstruction debates, I used online material in Serbian media found through searching for particular events and buildings. An important part of this research was the interviews: I interviewed 16 local architects and planners and two officials with different levels of experience in Belgrade, meeting a number of them several times over the years. Furthermore, I led a four-day workshop titled “Making Sense of Ruins” as part of the Disappearing Architecture project of the October Salon, Belgrade’s signature arts event. Through four days of intensive discussion and project work, I explored with 12 young architects and architecture students their perspectives of dealing with destruction and the memory of conflict, coming to terms with the past, and design responsibility for the new generations of city makers. Furthermore, I analyzed workshop materials from REX, an NGO who organized a debate on the fate of the Generalštab, which provided complementary, or reinforcing information with what I obtained from interviews. Finally, participant observation and continuous engagement with Belgrade’s everyday life and spaces framed the study in a lived experience of place and mediated sociopolitical narratives established from secondary sources with the diverse voices of local residents.

(Spatializing) Collective Memories of 1990s Political Violence in Belgrade

Before discussing how ruins and reconstructions are mobilized in the reshaping of collective memory, let us now outline the main threads of the collective memory of political violence and war in Belgrade and how they relate to urban space. In the contemporary landscape of Belgrade, there are few spatial traces of the decade marked by political violence, the 1990s. Most prominently, ruins such as the Generalštab attest to the NATO bombings of 1999. Nevertheless, war came to the city after a decade under the Milošević regime, marked by the lack of direct conflict in Belgrade itself, but of other forms of political violence, and mainly of a precarious existence for most people. On the one hand, this regime was accused of killing journalists and political opponents, maneuvering elections, persecuting minorities, and supporting paramilitaries in neighboring republics, after those declared their independence. But on the other, the local memories of 1990s are dominated by the difficult political and economic situation, the trade embargo, the shortage of goods, world-record inflation, and images of pensioners rummaging through trash for food (Clark Reference Clark2008).

The legacy of the 1990s in urban space is connected less to that economic crisis and more to the increase of informal practices. On the one hand, there are the particularly ornate villas, illustrative of what has been described as turboarhitektura, the houses of nouveaux riches who took advantage of the turbulent changes, seen by many locals as either connected to the regime, or engaged in various illicit activities, including war gains (Jovanovic Weiss Reference Jovanovic2013). Turboarchitecture acts as a reminder of the transition, fluidity, but also lawless times of the 1990s, with more recent buildings in this “style” highlighting continuities of some of today’s elites with the 1990s. Turboarchitecture, fetishizing ornate, historicist decorations came to oppose the modernist geometries of socialist Yugoslavia, marking a new era turning its back to the hegemonies of the line and assembling an eclectic, fluid aesthetic. But beyond architectural expression, they could also be seen by locals as the markers of the “post-socialist transition:” a state in which most construction became informal, without permit, a state which withdrew from many public services, in the typical guise of the post-socialist transition urbanism to be found in other countries in the region,(Stanilov Reference Stanilov2007; Hirt Reference Hirt2008; Hirt Reference Hirt2012) defined by privatization, but with the added perception of the role of the war and embargo economy in making new elites. On the other hand, the high number of informally built houses circling Belgrade is directly linked to the wars in the former Yugoslavia, as it is estimated that up to 100,000 houses were self-built in the 1990s, with many built by refugees for whom Milošević’s regime did not provide any assistance (Diener Reference Diener2012). While they are a reminder of war in neighboring republics from where refugees came, their peripheral location makes them less visible and minimizes their everyday impact on memory practices in the city.

In contrast, ruins from the NATO bombing are centrally located. The ruins of the Generalštab, of a number of ministries on Kneza Milosa Street, as well as the Air Force Headquarters in Zemun, a north-western district of the city by the Danube, are part of the urban landscape, mnemonic reminders of the 1999 war. The collective memory of the NATO bombing in Belgrade is that of a singular episode of direct engagement with war in the city. While the wars in the former Yugoslavia started in 1991, they did not affect Belgrade directly until 1999. The NATO bombing of Belgrade began on March 24, 1999, following the unsuccessful Rambouillet negotiations over Kosovo between NATO and the government of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY). According to NATO, the main objective of the bombing was to avert a humanitarian disaster in Kosovo by preventing the capacity of Serb forces to continue violent acts against Kosovo Albanians and enforce ethnic cleansing (Mccgwire 2000). The NATO bombings lasted 78 days and led to the destruction of more than 70 buildings in the Serbian capital and throughout the territory of the FRY, hosting military and political institutions but also other strategic and tactic targets that NATO described as part of Milošević’s war machine. While NATO presented it as a humanitarian intervention, the official narrative of FRY was that of an aggression on a sovereign state, an act of barbarism, with media in FRY stressing the opposition of many people, including cultural elites in the West to NATO’s operation (Mitrović Reference Mitrovic1999; Milosević Reference Milošević2000).

The readings and associations that Belgraders have for the ruins of NATO bombings are mediated by the three tropes associated with the collective memory of the NATO bombings: victimhood, injustice, as well as resistance. Victimhood is associated with the bombings themselves, but also to the general situation of the 1990s, one of impoverishment and international isolation. Memories of the bombings include moments of panic, withdrawal in secure shelters, media reports about destroyed landscapes and killed people, and then infrastructural malfunctioning, electricity shortages, and a demodernized life (Graham Reference Graham2004), punctuated by anger and disbelief at the West’s action (Lavrence Reference Lavrence2005). The injustice trope emerges connected to the mere act of bombing the city, bypassing the link between the NATO attacks and the atrocities in Kosovo, or previous ones waged or sponsored by Milošević in Croatia or Bosnia (Jansen Reference Jansen2000). Another dimension of injustice relates to the specific relationship of the city with the political violence of the regime: while it was the Serbian capital, and thus the site of power and decision-making, Belgrade was also a city that concentrated much of Serbia’s opposition to Milošević. Consequently, in the eyes of many who protested against Milošević throughout the 1990s, the West’s attack on the city, instead of helping the civic opposition, appeared as paradoxical and unjust. Finally, the collective memory of resistance is linked to the mere acts of urban resilience, but also to protest, including the large demonstrations and acts of defying the bombings by attending concerts in the main square or on possible targets such as Branko Bridge (Lavrence Reference Lavrence2005). The memory of the resilient, resistant, heroic city connects at times the 1999 events when people took to the streets in defiance of NATO with the image of Belgrade as the stage of major demonstrations against the Milošević regime in 1996–1997 (Jansen Reference Jansen2001; Lavrence Reference Lavrence2005). It is in this specific memory scape that debates on reconstruction would take place.

Ruins on Display

NATO ruins in Belgrade did not share a common fate. Some, like the tower of the former Central Committee of the League of Communists, was rebuilt like an office building, to which a large shopping mall was attached, revealing the lucrative, profit-driven nature of reconstruction in the new political economy, an act of creative destruction typical for neoliberal urbanism (Brenner and Theodore, Reference Brenner and Theodore2002) in which memory has no place. Others were fully rebuilt, like the Avala tower on a hill south of the city, which was rebuilt after a fundraising campaign to recover what was claimed as a symbol of the modern city. Yet several remain in the state of ruins, expecting reconstruction in a state of hiding. The Ministry of Internal Affairs on the central Kneza Milosa for instance, awaits reconstruction behind giant advertisements.

The ruins of the Generalštab, however, are on full display, dominating the intersection of Kneza Milosa and Nemanjina, two major avenues in central Belgrade. They are highly visible and through the solid modernism of the original design and their damaged state, they stand out in Belgrade’s institutional quarter. The singular physicality of the complex makes it a memorable presence, with its two parts, on either side of wide Nemanjina Street, cascading toward the street. Before the bombing, the part on the left side of Nemanjina was the headquarters of the General Staff of the Yugoslav Army and was referred to as “Building A,” while the larger “Building B” across the street housed the Federal Ministry of Defense. The bombing brought major structural damage to Building A, but only affected 5% of the square footage of Building B. From the street, however, both look damaged, giving this part of the city a distinctive look of an unsolved urban problem, of suspended waiting for a solution.

Reconstructing Generalštab

For Belgrade’s Generalštab, public authorities and architects brought forward a number of scenarios. For the cash-strapped Serbian Ministry of Defense, the preferred option for the ruined complex has been to sell the site to a private investor. The prime location of the Generalštab brought throughout the years a number of possible investors, from Mohamed bin Zayed, a sheikh from the Emirates, to American billionaire Donald Trump (Bizlife, January 13, 2014). This scenario matched the overall model of seeking investment for urban projects in the neoliberal, post-socialist cities in the region, where a withdrawing state has promoted an investors’ urbanism, facilitating investors’ wishes and sidelining broader questions of “public interest” (Stanilov Reference Stanilov2007). In Belgrade, this came to be epitomized by the Belgrade Waterfront project, a large redevelopment of the banks of the Sava led by an Emirates-based developer and actively supported by the government, which led to widespread protests and civic action.

Declarations of the Ministry of Defense showed confidence that the Generalštab would be redeveloped in the near future, with the issue of it being a listed building “to be solved.” Nonetheless, such announcements have been made on a number of occasions, but they never accounted to anything more than small interventions to clear rubble or small parts from the site. According to the B92 portal (April 30, 2015), the Ministry made a new announcement in April 2015 that the ruins would be cleared for redevelopment—the UAE hotel—in the summer of 2015. In the pragmatic reconstruction option, the only scenario is to remove the current building, and with it the spatial reminder of the NATO bombing. Though a lucrative, new reconstruction, it does not mean that the place loses its connections to the collective memories of war, but the final destruction and removal of the destroyed building and its replacement by a successful contemporary project would mean it would be a memory of those in the know, and not one triggered by ruins on display.

After the initial announcement of its clearing and redevelopment, the Generalštab became the object of debate in certain sectors of society. Aside from materials in the media, there were also debates organized by civil society, but also by a publicly-funded institution, the Belgrade Cultural Centre, which reflects at least a partial opening of the state to such debates. Architects and artists organized a debate associated with the project Kustoširanje, while active civic group REX organized an event about the fate of the Generalštab, one as recently as 2013. On Facebook, a group titled “Let’s save the Generalštab from profiteers” has been active in opposing the destruction of the ruins, while it is not clear whether they advocate a restorative reconstruction or a memorial engagement. Nevertheless, the debates about the fate of the Generalštab in the public sphere, despite sporadic media coverage and dissemination through segments of professional circles and civil society, remained liminal with regards to the process of decision making.

The debates featured a number of architects, who mostly advocated the restorative reconstruction of Dobrović’s magnum opus. The restorative reconstruction was supported by the decision of the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments to declare it a monument (listed building) in 2005, acknowledging the importance of the complex for Serbian modernism. The particular timing of this listing, in the aftermath of its destruction, is related to the emergence in the Serbian press of the first declarations of the Ministry of Defense that they were looking to sell the site to an investor. Facing the risk of the clearing of the site, the Association of Belgrade Architects (Društvo Arhitekata Beograda, DAB) mobilized to block this potential scenario and initiated the motion to declare the Generalštab a cultural monument. In Serbia, the status of a cultural monument allows the sale and the re-functionalization of a building, but requires the preservation of its original appearance. According to both the Belgrade and the national branch of the Institute, as well as a part of the architectural community, the only option for this valuable building was restorative reconstruction according to the original design, ensuring that Dobrović’s legacy continues.

For architects and heritage specialists, the Generalštab is a very significant building. One of my architect interlocutors called it the most important building in Belgrade. This importance lies in the fact that this is the only building that Nikola Dobrović, the most celebrated Serbian modernist architect, built in Belgrade; some say this is in fact his magnum opus. The building has been the object of much research of architects and architectural historians in Serbia itself (Bogunović Reference Bogunović2000; Kovacević Reference Kovačević2001; Bobić 2012; Matejić Reference Matejić2012). The focus was overwhelmingly on its beginnings and especially about the intentions of Dobrović’s design. One interpretation was that the building, completed in 1963 on the site where previous government buildings were destroyed in World War II, embedded the collective memory of that war. According to this explanation, its design was reminiscent of the Sutjeska gorges in Bosnia, the scene of one the crucial battles fought by the Yugoslav partisans (Kulić 2009). In Dobrović’s writings, however, the building expressed Bergson’s dynamic schemes, translated by Dobrović in an architectural vision of space in motion. Its ever growing interstitial space between the two main parts emphasized the potentiality for movement in space through voids. Dynamic relationships between buildings set in motion urban space and can transform in Dobrović’s view disorderly cities, like Belgrade before World War II into harmonious, unitary organisms. According to Bojan Kovačević, the Bergsonian explanation is the valid one, while the Sutjeska reference, made by Dobrović himself in 1960, was supposedly made just to please the regime. As a modernist project, the Generalštab would have no place for allegorical ponderings or memory, argues Kovačević. Notwithstanding the explanation of its design, the building was considered the crowning jewel of Belgrade’s modern architecture. In the aftermath of the bombing, Mihajlo Mitrović called for its reconstruction, invoking in his intervention in Politika (February 18, 2013) Belgrade-born Viennese architect Boris Podrecca who declared that it should be the first building in the city to be restored.

The declarations of representatives of the Ministry of Defense, however, did not show the same valuation of the building; one Minister of Defense called it downright ugly. On the one hand, this connects to the general antipathy of the public in various European contexts toward modernism; state authorities often replicate the views of the public with regards to architecture, out of populist reasons or as simply as they share these views. The gap between these valuations is expressed by a lack of understanding between architects and politicians, with architect Spasoje Krunic declaring local politicians as primitive, as they disregard the values of the past, be it the Generalštab, or even the Kalemegdan, with “monstrous, foolish” plans to build a Zaha Hadid tower at its edge (Popović 2013). Furthermore, while for architects like Kovačević this building is also connected to Serbian identity, the general public, including state authorities, reserve this role only for “older” buildings, which in Belgrade overwhelmingly means the 19th century, when the modern Serbian nation found its architectural expression in the major reshaping of former Ottoman Belgrade (Jovanović Reference Jovanović2013). The 19th century has been adopted by the post-Milošević state as the legitimizing reference point of the nation. The public discourse is building a direct link between the post-2000 Serbian state with the modernizing, European 19th century Serbia, in order to avoid much reference to the history of the Middle Ages connected too much with the controversial Kosovo issue, but also to refrain from engaging directly with the Yugoslav 20th century (Fridman Reference Fridman2015). Modernist architecture is on the other hand perceived not only as aesthetically “inferior” to the “old buildings,” but also as representative of socialist Yugoslavia rather than the Serbian nation. That can help explain why the state quickly proceeded with the reconstruction of the pre-1945 government building and air force headquarters in Zemun, while the post-1945 buildings have experienced significantly slower processes of reconstruction which in any case were not restorative.

The act of listing the building has created a “bureaucratic obstacle” for the redevelopment of the site, keeping the ruins in a state of expectation, between an owner unwilling to reconstruct, restoratively or at all, heritage institutions arguing for the need to rebuild faithfully to the original design, and the private sector. Investors are seemingly not interested in buying this central plot when they would not be able to build anything different from the original design, a condition of the ensemble's listed status, and thus missing the opportunity to bring profit by building using a contemporary design. Taika Baillargeon (Reference Baillargeon2013) describes the state of the building as continuous ephemeral, a space in waiting, with temporality becoming the main feature of the place. Nevertheless, the ruins are not frozen in time, as modifications did happen, such as the removal of the entrance to building B. And while the ruins bring forward the recent past of the bombing in Belgrade in an evident way, what is actually frozen is the debate about how their reconstruction can make sense of this destruction and of the collective memories of the NATO bombings, which are absent from the discussion. Returning to the building’s original form would imply canceling the site’s current role as a mnemonic device of the 1999 bombings, privileging the building’s architectural value over its memorial role. The two dominant options in the public discourse, the pragmatic and the restorative reconstruction, do not engage at all with the collective memory of the bombing nor with the wars of the 1990s that are intrinsically connected to that building.

A Ruin-Memorial

The political establishment generally avoided any statements about the possibility of keeping the ruins of the Generalštab as a memorial. Addressing this possibility would mean an opportunity to debate responsibility about wars, something that the political establishment was not ready to do. When asked about such a possibility, outspoken Aleksandar Vučić, minister of defense in 2013, brought back the aesthetic argument, stating that “it is not disputed to raise a monument to all the victims of the NATO aggression, all the soldiers who were killed, but I do not see any sense that this should be what it looks like” (SEEcult portal 2013), as he saw nothing valuable nor beautiful in the Generalštab complex. According to online portal Fakti.org on May 21, 2014, the Patriarch Irinej of the Serbian Orthodox Church voiced publicly such a possibility: “Those ruins which are located in the center of Belgrade should be never repaired. Let there be a testimony of our time, a testimony of [the destruction brought by] cultured Europe, testimony of democratic Europe who cared about freedom and democracy.” In interviews with Belgrade architects, I found that a number of architects considered the possibility of preserving the ruined Generalštab as a memorial to the 1999 bombings.Footnote 3 However, despite the commonality of the opinion that this would serve as an embodiment of the 1999 bombings, interpretations of the role of such a memorial diverged. For some, like Milica, the ruined site expresses victimhood and fixates on the experience of the NATO bombings and should thus become a monument to commemorate the destruction and the common suffering of Belgrade residents. Keeping the ruins in their state would be an act of preserving a “witness” of the events, a testimony to the authenticity and a visualization of the memory of bombing associated with the trope of victimhood and suffering. It would sustain the victimhood narrative not only for Belgrade residents, but also for visitors as well. The ruins are currently photographed by many, and are ascribed into a larger phenomenon of dark tourism in the Balkans, either as a primary or a side aspect of visits to the region, including sites of atrocities and “martyred cities” (Naef Reference Naef2016; Volcic, Erjavec, and Peak Reference Volcic, Erjavec and Peak2014).

For Ana, architect and activist, the call to preserve the ruins have, on the other hand, a strikingly different meaning. The ruins would be a signifier of the recent past with which society should come to terms:

For me it [the ruins of the Generalštab] has a value. This was very violent. I mean, basically, this NATO bombing in the end stopped what was happening. It should be a reminder to people and to Serbia of what they basically did in the 1990s. I mean that is that simple, that this is the end of that era, and it is violent, that era (Ana, architect, Belgrade).Footnote 4

While for Milica the ruins would stand as a memorial of victimhood; for Ana, they would be triggers of pondering over guilt, responsibility, and complexity of the wars in the 1990s in the former Yugoslavia. It would expand from the localized memory of the NATO bombings to the whole system of events that led to that bombing, to the avalanche of violence that was orchestrated from the building. What both Milica and Ana assume, however, is that the physicality of the ruins would engender a particular response or affect. However, the sheer presence of the ruins as a memorial would create just as diverse interpretations as they do at the moment: for some, the ruins remind of the months of bombing, for others of the entire military operations of the 1990s. A memorial consisting of ruins would bring different responses from different people, and, at times, distinctive responses and affects to the same person. This refers back to Huyssen’s ambiguity of ruins and Edensor (Reference Edensor2005, 846) seeing ruins as a foreground for “the value of inarticulacy, for disparate fragments, juxtapositions, traces, involuntary memories, uncanny impressions, and peculiar atmospheres cannot be woven into an eloquent narrative.”

It is not only that it is hard to identify the affect that such a memorial of ruins would trigger in the viewer, it is in fact difficult to claim that it would engender any affect at all. Consider, for instance, Aleksandra’s point: “I would keep them as ruins, this is a memorial for what happened…. But I have to say I see these ruins and I do not actually feel anything. It does not connect to me at all. I just know stories about it from my parents, it is not something I am emotionally connected to.”Footnote 5

Aleksandra, architecture student, 19 years old, stressed that her generation does not relate in the same emotional way to these ruins or to the events connected to them. They do not have the memory of the events, just accounts from their parents, and while she thinks that the site should be a memorial site, she comments she does not have the emotional reaction to work on such a project. This questions the relationship between ruins and the urban spectator, the affect that these ruins create thus appears to relate to the background of the person, it is not universal. The sheer presence of ruins is interpreted by each in different ways, and while it does relate to a common memory of destruction and hard times, it is interpreted according to contrasting narratives of victimhood and guilt, or in emotional, affective ways versus distanced, analytical ones.

Plurality of Pasts?

The majority of architects with whom I spoke concentrated on two events in the biography of the building: its creation as Dobrović’s masterpiece and the NATO bombings. Isidora Amidzić, who developed an art project on the Generalštab as an open wound in the city, considers the building to be fascinating also because on this site multiple histories intermingle: “Here was prince Milos Obrenović’s house in the 19th century, the first leader of independent Serbia, here was the Generalštab, here was where Zoran Đinđić was assassinated. There are so many layers of history here. This is why the site, the building is very important.”Footnote 6

Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic’s November 2016 announcement of plans to clear the site and build a monument to Stefan Nemanja twists the call for a memorial to reflect the history of the site by bringing in the idea of a general memorial for the Serbian nation. The site has no connection to the memory of Stefan Nemanja, but becomes, according to the new plan, a privileged place for a memorial to unite all Serbs around a cherished historical figure. Nevertheless, as other announcements have been made in the past about the possible re-functionalization, only time will tell if the memorial to Stefan Nemanja will come to fruition.

Despite the plurality of pasts invoked, one key element hardly appears though in all these narratives and accounts. While they all emphasize the form (as architectural design and as ruin) and the importance of the site for the city and its history, references to the function of the building as the headquarters of the Yugoslav army are rare. Architect Iva Cukić explained that architects ultimately think only about the building’s exterior, as this was an off-limits building before its bombing.Footnote 7 It was not one to which people would have had access, so it is only the shape, the exterior that is adulated and becomes the object of fascination and desire. What happened within its walls was not immediately transparent to architects or anyone from the public, so it never made it into the collective imaginary. The building is thus akin to Vidler’s uncanny architecture, echoing Freudian views of the unhomely (Vidler Reference Vidler1992). While the Yugoslav army was a societal binder, a symbol of Yugoslavia itself, a part of the “homely,” the events taking place in the 1990s made the institution and its headquarters a strange, uncanny version of itself, the unheimlich.

The lack of engagement with this function and thus with the destruction of the building blocks the process of shaping a reconstruction outside of the pragmatic-restorative reconstruction dichotomy. The lack of engagement relates on the one hand to the general obfuscation of the recent past in Serbian society, but also with the ambivalent and contrasting understandings of the building as home of the army and of the army as an institution. The building served for decades as the headquarters of the Yugoslav People’s Army, deemed to be an essential unifying institution for the country’s men, young Yugoslavs met people from all republics and nationalities during their military service, with the army thus being a place of encounter to foster friendships and camaraderie under the brotherhood and unity mantra of socialist Yugoslavia (Petrović 2010). Nevertheless, popular perceptions of the Yugoslav army shifted over time. In the 1980s, the army was perceived, particularly in the Western republics of Slovenia and Croatia as an increasingly Serb dominated bastion of social conservatism. From a common place for men and their memories, the melting pot of Yugoslavia, the Yugoslav army would in the 1990s become associated in the collective imaginaries of various Yugoslav groups with a very different role, that of aggressor for many in neighboring Yugoslav republics, the destroyer of Vukovar in Croatia, while for Serbia and Montenegro remaining a protector of the Yugoslav idea, as well as of the nation. The destruction of the Generalštab building consequently came in a very different framework of meaning than at its origins, as for many it symbolized Milošević’s violence machine. From being associated with the tropes of brotherhood and unity, the building came to have conflicting meanings of aggression for some and defense for others, and through its destruction, it became a mnemonic device for suffering and victimhood. The meaning of the ruins of the Generalštab is thus multi-layered, referring to different visions of the past, associated with different political emotions.

When young architects joined a focus group to discuss the issue of the past of the complex, a majority of participants confessed that they would not join a competition to propose a design for the reconstruction of the Generalštab, even if a large sum of money was involved. The many tensions between function, form, and the ambiguous role of the institution posed too great a challenge, “I would not be able to take such a job as a reconstruction of the Generalštab. There are too many layers, it is impossible to make sense of them” (Jovana, architecture student, Belgrade).

A conclusion to which this group came echoed an opinion I encountered in interviews with more senior architects: to think critically about the past in the reconstruction of the Generalštab is premature for Serbian society, 15 years after the NATO bombing: “We need more time to pass until we realize how to deal with such a building [Generalštab]. Our generation cannot solve such an issue” (Isidora, architect and teacher, Novi Sad).Footnote 8

Nevertheless, delegating the responsibility to a future generation implies that the ruins would remain frozen in the current state for a long time, which for such a central site, judging by the pressures of a neoliberal economy, is unlikely. Furthermore, the postponement of engaging creatively with critical thinking about the past condemns the city to continuously interact with the image of the ruin in its center, triggering affect and uncanny memories for the local inhabitants, and for outsiders creating the image of a city that did not regenerate and move on after the war.

Conclusion

The debates surrounding the reconstruction of the Generalštab reveal how making sense of ruins often implicates multiple, sometimes conflicting threads, of collective memory. The Generalštab, a building complex that some interpret as an embodiment of collective memories of World War II, is now, as ruins, a mnemonic device for the NATO bombing of 1999. As the building of the Yugoslav National Army, it weaves together multiple memories and meanings, from the interpretation of it echoing the Sutjeska partisan battles to its shifting connotations from guarantor of freedom in socialist Yugoslavia to a disoriented army in a disintegrating country, a destructive army in Vukovar, allegedly connected to crimes in Kosovo, object of NATO’s wrath, and now, a shrinking presence in a neoliberal state. Aside from its role as a depository of a diverging Yugoslav memory, it relates to particular local memories, from Belgrade’s liberation in 1944 by the precursors of the YNA, to Belgrade’s bombing in 1999, but also the assassination of Zoran Đinđić. The status of the Generalštab reveals tensions between local and regional memories, the role and valuation of different periods. The diversity of reactions and visions for the fate of the Generalštab from the side of architects illustrates the rich potentiality of memorial engagement but also the sheer ambiguity that a ruin or a memorial reconstruction can engender. For a number of architects, the ruined Generalštab represents a memorial of the bombing itself and its reconstruction is an act of memorial architecture which has to engage with the trauma of the city. For others however, the duty to the original architect, a master of Yugoslav modernism, would imply a faithful reconstruction that would negate the bombing. In between lie different interpretations of functions of the building and moments of memory references. The Generalštab’s relevance to collective memories of war in Belgrade, of war in the larger context of the former Yugoslavia, and of Yugoslavia’s socialist and post-socialist periods, shows the challenges of making sense of ruins in relationship to a particular past, revealing the difficulties of interpreting its ruins or possible reconstructions according to a singular frame.

These debates also reveal how multiple threads of collective memories are mediated by functional and lucrative concerns. The reshaping of urban space after the NATO bombings in Belgrade reflects the importance of political economy, investment and funding in the overall reconstruction process rather than a primacy of an engagement with the memory of the bombings. Urban reconstruction is framed as a technical process of repair which would have a seemingly uncritical and indirect relationship with collective memories of conflict. The site of the Generalštab remains a ruin that is interpreted in many ways, but its fate may be determined by capital and allegiances rather than memory. Leaving the complex to mere real estate concerns could be understood as a typical neoliberal urban project—not unlike the Belgrade waterfront—of a state withdrawing from investment, but could be understood as an expression of a state politics of non-engagement with the past of the 1990s, of which 1999 is a climax in Belgraders’ collective memory. Clearing the site and placing a memorial for a medieval ruler of Serbia would displace the particular memory of the site, while miming concerns of the state to act as a memorial actor. Through the obfuscation of the memory of the bombings, the state could be seen to dodge any discussions about causality and responsibility.

In Serbia, ruins and reconstructions alike highlight not only an obfuscated recent past, but the challenges of reshaping collective memories and national identities after political violence. What emerged is a complex canvas of how architectural reconstruction, collective memory, and national identity shape each other. On one hand, reconstruction design responds to collective memory as architects make sense of the war experience and of the main memory narratives; on the other hand, reconstructed urban space has the potentiality to reshape memory by creating a new cadre matériel for remembrance, in which the absence or transformation of physical objects has an impact on memory and highlights narratives connected to national identity, like victimhood or resilience.

Beyond these interlinkages, another aspect which emerged from this analysis is the role of affect and subjectivity in the way ruins and their mnemonic capacity is perceived, as indicated by the contrasting reactions to the ruined Generalštab. Consequently, this research suggests that there is a need to mediate the concept of memory with the potentiality of emotion and affect manifested through the subjective experience of the viewer. Ruins and memorial architecture are not just mere depositories of homogenous collective memories which would engender similar, coherent reactions in the viewer. Through outlining the diversity of views and understandings of these ruins, I suggested that notwithstanding human intentionality, including action or non-action on war ruins, the destroyed or reconstructed cityscape spatially embodies a certain narrative of the past. Engaging with the affective dimensions of spatial interventions could be therefore an avenue to expand our understanding of collective memory and narratives.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to my interlocutors in Belgrade throughout the years, and particularly to the October Salon and Mia David for inviting me to organize the workshop “Making sense of ruins” with young architects in Belgrade in October 2014, and to Orli Fridman and Krisztina Racz, who organized a workshop on memories of NATO bombing (February 2015), where I presented a first draft of this paper. Special thanks to the coordinators of this special issue and the anonymous reviewers for their comments.

Financial Support

I am grateful to the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation for awarding a Graduate Scholarship for my PhD research at the University of Cambridge.