The bipolar confrontation between the US and Soviet Union during the Cold War prompted statesmen and scholars alike to seek ways to prevent nuclear holocaust. Many argued that this was best done through deterrence, and accordingly much attention was devoted to exploring the dynamics of deterrence, particularly from about 1960–1990. However, the end of the Cold War brought about by the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe and the collapse of the Soviet Union led to a lessened tension between the US and Russia. In response, many believed deterrence to be irrelevant in the post-Cold War world,Footnote 1 and attention shifted to topics such as the democratic peace, globalisation, and international terrorism.

Nonetheless, deterrence – the use of a threat (explicit or not) by one party in an attempt to convince another party to maintain the status quo – is a general phenomenon that is not limited to any particular time or space.Footnote 2 Moving beyond a simple focus on the US-Soviet relationship, scholars have recently begun further explorations of deterrence, through development of theory,Footnote 3 analysis of policy alternatives,Footnote 4 and empirical analysis.Footnote 5

This article seeks to evaluate where deterrence theory stands today, focusing primarily on recent developments. Specifically, what follows is an examination of several important topics in deterrence theory. The article begins with a consideration of the distinction between classical deterrence theory and perfect deterrence theory, and then turns to a discussion of the assumption of rationality in deterrence. Following these initial steps is an examination of three important categorisations of deterrence: unilateral versus mutual deterrence, conventional versus nuclear deterrence, and general versus immediate deterrence. After that, the difficult task of testing deterrence theory and key avenues of recent theoretical developments are examined before turning to final conclusions.

Theories of deterrence

An evaluation of where deterrence theory stands must start with a consideration of what deterrence theory is. Deterrence theory – often called rational deterrence theory – argues that, in order to deter attacks, a state must persuade potential attackers that: 1) it has an effective military capability; 2) that it could impose unacceptable costs on an attacker, and 3) that the threat would be carried out if attacked.Footnote 6 And so deterrence theorists, both earlyFootnote 7 and more recentlyFootnote 8 have attempted to explain deterrence through several key elements: ‘the assumption of a very severe conflict, the assumption of rationality, the concept of a retaliatory threat, the concept of unacceptable damage, the notion of credibility, and the notion of deterrence stability.’Footnote 9

Morgan argues that all of these efforts are explorations of the same theory.Footnote 10 While seemingly disparate in both time and approach, all focus on similar issues and work from similar assumptions. For Morgan, while there may be different deterrence strategies there is only one deterrence theory.

Morgan's position notwithstanding, the question of whether the distinctions between different variants of deterrence theory are significant enough to consider them separate theories remains open. Zagare argues that much of the deterrence literature can indeed be categorised as a single theory: classical deterrence theory.Footnote 11 However, because theoretical approaches and assumptions vary widely from one theorist to another, Zagare also divides classical deterrence theory into two sub-groups: structural deterrence theory and decision-theoretic deterrence theory.Footnote 12

Structural deterrence theory, closely aligned with realism, argues that a balance of power brings peace; if two states are equal in power, each will be deterred since neither will be able to gain an advantage.Footnote 13 Furthermore, structural deterrence theory argues that nuclear deterrence is inherently stable. While ‘in a conventional world, a country can sensibly attack if it believes that success is probable’, with nuclear weapons ‘a nation will be deterred from attacking even if it believes that there is only a possibility that its adversary will retaliate.’Footnote 14 Thus, the key to deterrence is a second-strike capability, and once this is achieved,Footnote 15 deterrence is straightforward since the enormous costs associated with nuclear war make an attack irrational. Accidental war, then, represents the only real threat to deterrence.Footnote 16

Decision-theoretic deterrence theorists, on the other hand, utilise expected utility and game theory to construct models of deterrence.Footnote 17 While their approach is quite different, decision-theoretic deterrence theorists take the structural deterrence theorists' idea that nuclear war is irrational to heart by assuming that conflict is always the worst outcome.

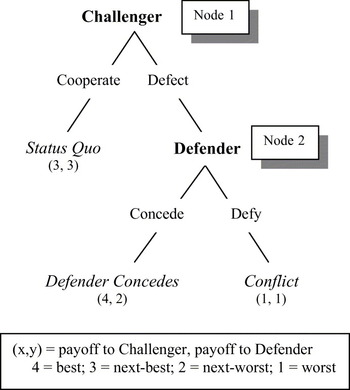

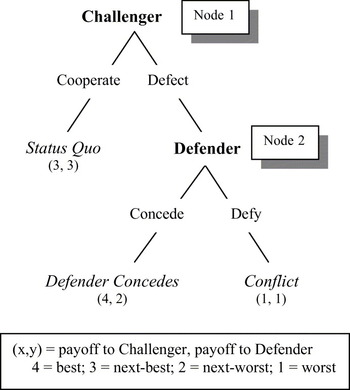

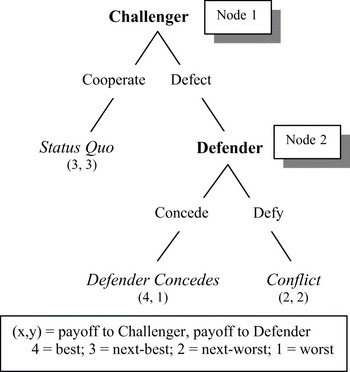

A typical ‘classical’ model of deterrence is shown in Figure 1. In this game, there are two actors: a Challenger, who seeks to alter the status quo, and a Defender that seeks to deter such challenges. Challenger begins the game by deciding whether to cooperate, in which case the Status Quo remains, or attack Defender by choosing to defect. Defender, in turn, has two possible responses to a challenge: to concede, resulting in Defender Concedes, or to defy, resulting in Conflict. Challenger would most prefer Defender Concedes, and Defender likes Status Quo the best. However, they both agree that Conflict is the worst possible outcome.

Figure 1. ‘Classical’ deterrence game.

Defender faces a quandary: a concession provides a more favourable outcome than the conflict that would follow defiance, but if Challenger knows that Defender will concede, Challenger will always attack and deterrence will always fail. Zagare and Kilgour label this dilemma the ‘paradox of mutual deterrence’.Footnote 18 Classical deterrence theory offers two primary solutions.

The first proposed solution is for Defender to make an irrevocable commitment to a hard-line strategy. Such irrevocable commitments are made by burning bridges to limit one's options by eliminating the ability to back down even though that would be the preferred alternative.Footnote 19 So Defender makes an irrevocable commitment to defy, and must communicate this commitment to Challenger.Footnote 20 Then Challenger is faced with the choice of remaining at the Status Quo by cooperating or defecting and starting a Conflict. Since choices of cooperate by Challenger and defy by Defender are mutual best responses, this strategy pair denotes a Nash equilibrium with Status Quo as the outcome. The problem, however, is that if Challenger does attack, then Defender's only rational response would be to concede, leading to Defender Concedes. Although the strategy pair (cooperate, defy) is a Nash equilibrium, it is not sub-game perfect because it involves an irrational choice by Defender off the equilibrium path.Footnote 21 The only sub-game perfect equilibrium is the strategy pair (defect, concede), which results in Defender Concedes.Footnote 22

The second solution to this dilemma offered by classical deterrence theorists is threats that leave something to chance.Footnote 23 These threats allow Defender to circumvent the problem of irrational action by threatening to take action ‘that raises the risk that the situation will go out of control and escalate to a catastrophic nuclear exchange’.Footnote 24 Thus, rather than relying upon a threat to make an irrational choice for war, Defender can simply make a rational choice to raise the risk of war and leave the question of whether war starts or not to chance. Powell demonstrates that threats that leave something to chance not only lead to successful deterrence, but the resulting equilibrium is perfect as well.Footnote 25

However, the idea of threats that leave something to chance rests upon the possibility of accidental war. There is a lot of speculation about this possibility,Footnote 26 with the outbreak of World War I often cited as the prime example of an inadvertent war.Footnote 27 However, Trachtenberg conducts an extensive examination of the coming of the First World War and concludes that

when one actually tests these propositions against the empirical evidence, which for the July Crisis is both abundant and accessible, one is struck by how weak most of the arguments turn out to be. The most remarkable thing about all these claims that support the conclusion about events moving ‘out of control’ in 1914 is how little basis in fact they actually have.Footnote 28

The prime example of accidental war turns out to be not such a good example after all. Rather than support the idea, the outbreak of World War I actually undermines the idea of threats that leave something to chance.

Schelling suggests that in most crises, one side or another will be willing to run greater risks of mutual assured destruction to achieve its goals. Therefore, credibility is determined by whose interests are more greatly threatened by an ongoing crisis and by who is more willing to take risks to protect their interests. Hence, deterrence becomes a ‘competition in risk taking’ as states employ brinksmanship in what the subtitle to Powell's 1990 book calls ‘the search for credibility’. But a threat is said to be credible if it is believed.Footnote 29 Given that a nuclear attack invites one's own destruction, the threat to choose to do so is not believable, and is thus not credible. Schelling argues that while this is true, the threat to increase the risk of inadvertent war can in fact be believable.Footnote 30 But since historical evidence shows that World War I – the prime example of ‘accidental war’ – arose as a result of conscious decisions, not chance,Footnote 31 these threats that leave something to chance seem to be not credible after all.

Classical deterrence theory and its associated ideas such as mutual assured destruction and brinksmanship represent the conventional wisdom about deterrence. Zagare and Kilgour offer an alternative to classical deterrence theory, which they call perfect deterrence theory.Footnote 32 In particular, they depart from classical deterrence theory in their view of credibility. Zagare and Kilgour argue that threats are believable, and thus credible, when they are rational to carry out.Footnote 33 Connecting credibility with rationality in this way is consistent with the treatment of credibility in game theory.Footnote 34

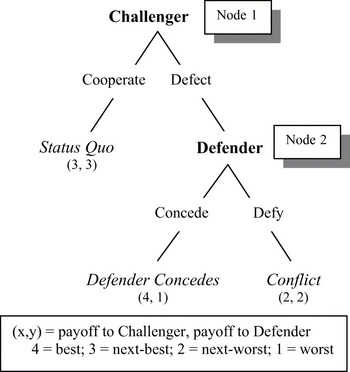

This connection between credibility and rationality can be seen by re-examining the game in Figure 1. If Defender prefers Defender Concedes to Conflict, and this is known to Challenger, Challenger has no reason whatsoever to believe that Defender will carry out her threat; thus Defender's threat is not credible. On the other hand, if Defender prefers Conflict to Defender Concedes, and this is known to Challenger, Challenger would believe Defender's threat; that is, Defender's threat would be credible. The simple deterrence game with a credible threat by Defender is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Simple deterrence game with a credible threat.

In this game, Defender will choose to defy at node 2 because a concession would result in her least preferred outcome. Knowing this, Challenger will cooperate at node 1 because the outcome that results (Status Quo) is preferred to the outcome that results from defection (Conflict). Thus, if Defender has a credible threat, Status Quo is the sole equilibrium outcome.

Accordingly, the solution to the paradox of mutual deterrence is the presence of credible threats.Footnote 35 When both sides possess credible and capable threats, Status Quo emerges as the rational outcome. Furthermore, the resulting equilibrium is sub-game perfect, and it does not rest upon untenable assumptions of the possibility for accidental war.

Zagare and Kilgour label their theory ‘perfect’ because of their insistence on the use of perfect equilibria. This insistence stems from the observation that ‘perfectness rules out threats that are not credible’.Footnote 36 However, Powell has also employed perfect equilibria, but his work certainly falls within classical, rather than perfect, deterrence theory.Footnote 37 The real hallmark of perfect deterrence theory is the insistence that credibility varies, and that credibility is determined by a state's preference between conflict and backing down.Footnote 38

While Morgan argues that there is only one deterrence theory, it is clear that there are at least two: classical and perfect.Footnote 39 While classical deterrence theory is rooted in the basic assumption that the high costs of nuclear war make conflict the worst outcome for everyone, perfect deterrence theory is rooted in the assumption that different states have different preferences. While some may indeed prefer backing down to fighting, others prefer to fight and only these latter states have credible threats. Although there are other differences between the two theories,Footnote 40 this one assumption makes a tremendous impact on the predictions and explanations offered.

Assumption of rationality in deterrence theory

But what about the assumption of rationality? Both classical and perfect deterrence theory are rooted in the assumption of rationality, which can be defined as

gaining as much information as possible about the situation and one's options for dealing with it, calculating the relative costs and benefits of those options as well as their relative chances of success and risks of disaster, then selecting – in light of what the rational opponent would do – the course of action that promised the greatest gain or, if there would be no gain, the smallest loss.Footnote 41

Morgan goes to great lengths discussing limits of rational behaviour. These limits arise because decision makers lack sufficient time to analyse all alternatives in a crisis situation, they lack information about the opponent and the consequences of decisions, and/or they are affected by emotions or cognitive limitations. These limitations to rational decision-making processes have been previously well established.Footnote 42

Furthermore, deterrence can fail even when states appear rational or succeed despite irrationality. Thus, Morgan laments that ‘rationality is an inconsistent guide to how deterrence turns out’.Footnote 43 For these reasons, Morgan concludes that the assumption of rationality is unnecessary for the development of deterrence theory and that an alternative theory needs to move away from reliance upon it.

But Morgan and others fail to account for the distinction between procedural and instrumental rationality. Morgan defines procedural rationality, and it is these procedures that he and others focus upon in determining whether or not states are ‘really’ rational.Footnote 44 However, the assumption used in rational deterrence theory – as in rational choice theory more broadly – is instrumental rationality.Footnote 45

An instrumentally rational actor is one who, when confronted with ‘two alternatives which give rise to outcomes […] will choose the one which yields the more preferred outcome’.Footnote 46 Thus, Morgan is quite correct to state that ‘what is rational for an actor depends on the actor's preferences’. However, his further claim that ‘knowing preferences is not necessarily enough […] Rationality is not simply acting out one's preferences or objectives – it is arriving at that action by choosing in a specified way’Footnote 47 is not in accord with instrumental rationality. If an actor chooses according to her preferences, then she is instrumentally rational, regardless of which procedures are used. And since these preferences are subjective in nature, emotions, cognitive limitations, and the like may shape preferences but do not make an actor irrational.Footnote 48

Of course it can be quite difficult to determine an actor's subjectively held preferences with certainty. Accordingly, determining the rationality of any action can be quite difficult as well. To determine that an action is irrational, one must prove that the actor deliberately chose contrary to his subjective preferences given the situation as he saw it. On the other hand, determining that an action is rational requires proof that the actor chose according to her preferences given the situation as she saw it. I would argue that either task is immensely difficult if not impossible. And this is precisely why it is assumed. It is thus no surprise to a rational deterrence theorist that rationality is an inconsistent guide to how deterrence turns out because since: 1) all actions are rational (by assumption) and, 2) deterrence sometimes succeeds and sometimes fails (by observation), this point is obvious.

One final point regarding rationality deserves consideration. Morgan correctly points out that, in seeking solutions to the paradox of mutual deterrence discussed in the previous section, classical deterrence theorists such as Schelling and Kahn move away from rationality in discussions of strategic ploys such as ‘feigning irrationality’. These contradictions introduce logical inconsistency in to classical deterrence theory – the very thing that rational choice theory is used to avoid.Footnote 49 But perfect deterrence theory demands consistent use of the rationality assumption and thus provides a logically consistent alternative.

Categorisations of deterrence

I now turn to a consideration of three common categorisations of deterrence, starting with the distinction between unilateral and mutual deterrence.

Unilateral vs. mutual deterrence

Deterrence deals with states' attempts to prevent others from challenging the status quo. The need for deterrence to prevent these challenges depends upon whether the state desires alterations to the status quo. Deterrence is not needed to prevent a state that is satisfied with the status quo from initiating a challenge. Deterrence is only relevant when states seek alterations in the status quo. If neither state in a dyad seeks to alter the status quo, then there is no deterrence. If one state seeks to alter the status quo but the other does not, there is unilateral deterrence. And finally, a situation where both sides of a dyad seek alterations to the status quo is one of mutual deterrence.

Perfect deterrence theory models both mutual and unilateral deterrence situations and demonstrates that deterrence is more stable in unilateral than mutual deterrence.Footnote 50 Senese and Quackenbush apply this logic to an analysis of settlements to militarised interstate disputes.Footnote 51 They argue that imposed settlements lead to unilateral deterrence whereas negotiated settlements and disputes ending without a settlement require mutual deterrence to maintain peace. Accordingly, they expect imposed settlements to be the most stable, and their empirical analysis strongly supports this conclusion.

Given strong empirical support for the theoretical prediction that unilateral deterrence is more stable than mutual deterrence, it would seem to make sense for states to desire an ‘escape from mutual deterrence’.Footnote 52 Since power is satisfyingFootnote 53 a state may be able to move from mutual to unilateral deterrence by increasing its power relative to its counterpart. Morgan argues that this implies ‘that a challenger is irrational enough to let the deterrer achieve unilateral deterrence – the deterrer is rational in trying to escape mutual deterrence while the challenger is irrational enough to let this happen.’Footnote 54

But a move from mutual to unilateral deterrence does not have such implications. Power is not the same thing as satisfaction.Footnote 55 Therefore, if the deterrer wants to escape mutual deterrence, then he only needs to no longer desire an alteration of the status quo – no increases in power are necessary. And even if the deterrer does increase in power dramatically, this would not at all imply irrational action by the challenger, since such an increase does not depend on any action by the challenger whatsoever.

Therefore, Morgan's concerns that attempts to escape from mutual deterrence could cause instability are not logically supported. Unilateral deterrence is more stable than mutual deterrence, all else being equal. If a state wants to escape from mutual deterrence, it only needs to decide that it is satisfied with the status quo and therefore no longer needs to be deterred.

While the distinction between unilateral and mutual deterrence rests on the interests of the states involved, the next distinction is based upon the weapons possessed by these states.

Nuclear and conventional deterrence

Deterrence theory was brought to prominence in academic and policymaking circles because of the threat of nuclear holocaust during the Cold War. Therefore, many scholars have focused on the dynamics of nuclear deterrence.Footnote 56 Others have focused specifically on conventional deterrence.Footnote 57 Support for this analytical distinction rests on the notion that ‘nuclear weapons dissuade states from going to war much more surely than conventional weapons do’.Footnote 58

However, this expectation regarding the stabilising effects of nuclear weapons is contradicted both empirically and logically. Empirically, although classical deterrence theorists claim that nuclear weapons are inherently stabilising, there is evidence that non-nuclear opponents of nuclear powers do not appear cautious or constrained in their hostile activity.Footnote 59 Furthermore, the possession of nuclear weapons does not appear to impede escalatory behaviour by non-nuclear opponents.Footnote 60

Logical problems stem from classical deterrence theorists' claim that nuclear warfare entails such high costs that it is the worst possible outcome for all sides. It is precisely the assumption that conflict is the worst possible outcome that leads to the paradox of mutual deterrence discussed previously. If conflict – nuclear or conventional – indeed is always the worst possible outcome, deterrence cannot ever be successful. Any state that is attacked will always capitulate rather than bring about its own worst outcome, and knowing this, challengers will always attack.

One might think that policymakers would either have to have nerves of steel or brains of lead to launch a massive nuclear attack against a similarly armed adversary and expect that the adversary would do nothing as it faces total destruction. After all, what leader would not retaliate in response to a nuclear attack? In other words, it is hard to imagine that a state would prefer backing down after being attacked by nuclear weapons to retaliation and all-out nuclear war. This highlights the problem with the use of Chicken as a model of deterrence, for it stipulates that backing down is indeed preferred to fighting back. And classical deterrence theory assumes not only that some states hold this preference, but that all do.

The only logically consistent resolution to this paradox is the existence of mutually credible threats, where each state prefers to fight rather than back down.Footnote 61 Accordingly, if classical deterrence theory is correct that nuclear weapons make conflict the worst possible outcome – and thus, less preferable than backing down – then they are destabilising, not stabilising. If classical deterrence theory is not correct in this assumption, then the fundamental idea that deterrence is a game of Chicken falls apart. In any case, Zagare and Kilgour demonstrate that, beyond a certain threshold, the ability to impose additional costs has no effect on the stability of deterrence. Thus, as Morgan argues, ‘nuclear deterrence […] is given too much credit for the long peace’.Footnote 62

To draw conclusions regarding the distinction between nuclear and conventional deterrence, one can focus on three themes. First, the concept of deterrence is broad and is not limited to either nuclear or conventional conflicts. Secondly, states have an interest in deterring both conventional and nuclear conflicts. And finally, classical deterrence theory's claims about nuclear deterrence – which are the basis of the analytic distinction between nuclear and conventional deterrence – are contradicted both logically and empirically. Put together, these points indicate that deterrence theory should focus on general explanations of the dynamics of deterrence, rather than limited explanations of nuclear or conventional deterrence.

One final categorisation to be reviewed here is the distinction between general and immediate deterrence.

General vs. immediate deterrence

Morgan highlights the importance of the distinction between general deterrence and immediate deterrence.Footnote 63 Immediate deterrence ‘concerns the relationship between opposing states where at least one side is seriously considering an attack while the other is mounting a threat of retaliation in order to prevent it.’ Conversely, general deterrence ‘relates to opponents who maintain armed forces to regulate their relationship even though neither is anywhere near mounting an attack’.Footnote 64 Thus, general deterrence has less to do with ‘crisis decision making’ than with everyday decision-making in relationships involving conflicts of interest.

General deterrence is much broader than immediate deterrence. For example, consider a case of immediate deterrence such as the Cuban Missile Crisis. Studies of immediate deterrence seek to understand how escalation can be controlled within the context of a crisis. That is, once a state has already challenged the status quo, how can a defending state deter the challenger from taking further action and thus avoid all-out war? Successful immediate deterrence entails a challenger's backing down following the defender's threat to retaliate, whereas the failure of immediate deterrence results in the challenger's attacking despite the defender's retaliatory threat.

The need for immediate deterrence indicates that general deterrence has previously failed.Footnote 65 If general deterrence always succeeds, crises and wars do not occur. Stated differently, the successful operation of general deterrence precludes the existence of immediate deterrence. It would seem appropriate, then, to focus on the origins of international crises before examining management of those crises. Since general deterrence necessarily precedes immediate deterrence, the analysis of general deterrence is more important for a general understanding of international conflict than the analysis of immediate deterrence.Footnote 66 Furthermore, as the literature on selection bias makes clear, examination of immediate deterrence without consideration of the origins of immediate deterrence cases (that is, the failure of general deterrence) can produce misleading empirical results.Footnote 67

Accordingly, what is really needed in deterrence theory is a theory of general deterrence because ‘general deterrence is a situation much more typical of international politics’ and immediate deterrence is ‘a type of situation that seldom exists’.Footnote 68 But Morgan argues that ‘at best we have fragments of a theory of general deterrence’.Footnote 69

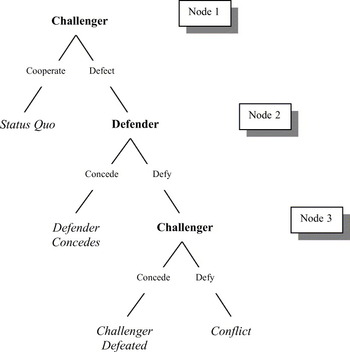

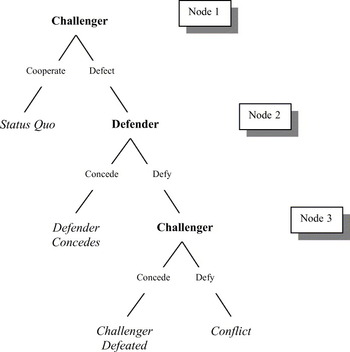

However, perfect deterrence theory is a theory of general deterrence. This can easily be seen by examining the Unilateral Deterrence Game shown in Figure 3.Footnote 70 There are two players, Challenger and Defender. At node 1, Challenger can choose whether to cooperate or defect. If Challenger cooperates, the Status Quo persists. If Challenger chooses to defect, Defender has an opportunity to respond. At node 2, Defender can choose whether to concede, resulting in Defender Concedes, or defy, giving Challenger the next choice. At node 3, Challenger can also choose whether to concede or defy. If Challenger concedes, the outcome is Challenger Defeated. However, if Challenger chooses to defy, the outcome is Conflict.

Figure 3. Unilateral deterrence game.

General deterrence fails as a result of some challenge to the status quo (that is, Challenger chooses to defect at node 1). So if no such challenge occurs (Challenger cooperates at node 1), then general deterrence succeeds and the status quo remains unchanged. Immediate deterrence deals with attempts by defender to get the challenger to back down (Defender's choice of how to respond at node 2 and Challenger's choice of whether to back down at node 3). Clearly the Unilateral Deterrence Game is a model of general deterrence.

In addition to the model of unilateral deterrence reviewed here, perfect deterrence theory incorporates models of mutual and extended deterrence, which are also focused within the realm of general deterrence. Thus, perfect deterrence theory provides a theory of general deterrence. Unfortunately, however, the ‘empirical study of general deterrence is less extensive and less well developed than is the body of work on immediate deterrence’.Footnote 71 I now turn to an examination of the difficult task of testing deterrence theory.

Testing deterrence theory

Theories are useful to the extent that they help to understand and explain reality. To determine the usefulness of deterrence theory, empirical testing is needed.Footnote 72 Two empirical approaches have been used in the deterrence literature: case-studies and quantitative analysis.Footnote 73 The case-study literature has focused on in-depth analyses of particular deterrence situations, but these studies have generally endeavoured to criticise, rather than test, rational deterrence theory.Footnote 74

Furthermore, an unfortunate divide exists between formal theories and the quantitative analysis of deterrence. There are several reasons for this disconnect: 1) while deterrence theory has typically focused on general deterrence, quantitative studies have focused almost exclusively on immediate deterrence; 2) quantitative studies that have been done have generally not tested rational deterrence theory, but rather have tested independently developed hypotheses and, 3) when studies have harkened back to rational deterrence theory, they have typically examined classical deterrence theory, a formal framework characterised by logical inconsistency and empirical inaccuracy.

An example of this continuing divide is Danilovic's recent quantitative study of extended deterrence.Footnote 75 Danilovic argues that a state's inherent credibility – determined in large part by its regional interests – is a far more important predictor of deterrence outcomes than attempts to shore up credibility through the use of commitment strategies recommended by Schelling and other classical deterrence theorists.Footnote 76 However, she does not explicitly tie her quantitative analysis to any theory of deterrence. Thus, it is left to the reader to bridge this divide.

Fortunately, through her focus on credibility, Danilovic directly addresses a key distinction between perfect and classical deterrence theory.Footnote 77 As discussed above, the reason that classical deterrence theorists focus on commitment tactics as ways to shore up credibility is that they assume that all threats are inherently incredible. Zagare and Kilgour, on the other hand, argue that states' threats are only credible to the extent that the state actually prefers conflict to backing down.Footnote 78 Accordingly, Danilovic's analysis can be seen as an attempt to determine what factors (relative power, regional interests, and democracy) lead states to prefer conflict over backing down.

Since rational deterrence theory is primarily expressed through game-theoretic models, empirical tests of the theory need to be able to test predictions that result from such models. There are two primary avenues available for such tests: evaluation of equilibrium predictions and evaluation of relationship predictions.Footnote 79 Evaluation of equilibrium predictions entails comparison of the outcome predicted in equilibrium at each observation with the outcome actually observed. Bennett and Stam's test of Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman's International Interaction Game is an example of such evaluations of equilibrium predictions.Footnote 80 Once one relates Danilovic's argument about inherent credibility to Zagare and Kilgour's arguments about credibility, it becomes clear that her analysis is at least indirectly an evaluation of perfect deterrence theory's relationship predictions.Footnote 81

Selection of deterrence cases has been a subject of much disagreement, primarily between quantitative and case study researchers. An important part of the debate in World Politics in 1989–1990 dealt with the proper identification of immediate deterrence cases.Footnote 82 Unfortunately, however, the existing deterrence literature provides little guidance on the selection of general deterrence cases. This is particularly important because of the importance of general deterrence, as discussed above.

Morgan sees the maintenance of armed forces as indicative of general deterrence behaviour.Footnote 83 One can safely assume that every state wishes to deter attacks against itself – this is the basic rationale for the maintenance of armed forces. This is essentially identical to the assumption within the alliance portfolio literature that every state has a defence pact with itself.Footnote 84 Therefore, the difficult part of general deterrence case selection is not determining who makes deterrent threats (everyone does), but rather what states the threats are directed against. General deterrent threats are directed against any state that might consider an attack, but it can be difficult to identify exactly which states might do so. The key to general deterrence case selection then is to identify which states may consider attacking which other states. I argue that the states that might consider an attack on a particular state are those that have the opportunity to fight that state. Fortunately, Quackenbush has developed the concept of politically active dyads, which capture opportunity as a necessary condition for international conflict.Footnote 85 Therefore, politically active dyads can be used as a case selection mechanism for studies of general deterrence.

Another concern that has often driven debates between those employing case-studyFootnote 86 and quantitativeFootnote 87 methodologies is the determination of deterrence success and failure. However, game-theoretic models of deterrence do not make predictions regarding the success or failure of deterrence, per se; rather, the particular outcome of an interaction is predicted.Footnote 88 Furthermore, classification of certain cases as successful deterrence runs into a variety of conceptual and selection bias issues.Footnote 89

Quackenbush tests the equilibrium outcome predictions of perfect deterrence theory.Footnote 90 Since the equilibrium predictions of perfect deterrence theory rely on the actors' preferences, this requires explicit specification of utility functions for the actors involved. To do this, he employs a modification of the technique – using relative power as a measure for probability of victory and measuring utilities based on similarity of alliance portfolios – pioneered by Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman.Footnote 91 Quackenbush uses binary and multinomial logit methods to examine the prediction of militarised interstate disputes and of particular game outcomes, and the results indicate that the predictions of perfect deterrence theory are generally supported by the empirical record.

Perfect deterrence theory has also been applied to the analysis of conflict settlements by Senese and Quackenbush.Footnote 92 Their analysis demonstrates that perfect deterrence theory – through a comparison of the unilateral and generalised mutual deterrence games – makes predictions about the stability of different types of conflict settlements, and these predictions are strongly supported by the empirical record. This is an insight that was not gained through other analyses of the same subject.

Most attempts to test deterrence theory have utilised large-N, quantitative methods. Such analysis is useful because of the generalisable nature of conclusions derived from it. However, case studies would also be useful for future research. Since quantitative analyses demonstrate that perfect deterrence theory is generally supported by the historical record,Footnote 93 there is evidence that the theory can usefully be applied to particular cases. This can be done through the application of the insights of perfect deterrence theory to detailed case studies of particular historical episodes in order to understand these intrinsically interesting events more completely. For example, one study applies perfect deterrence theory to an analysis of the war in Kosovo to answer questions – such as why NATO's threat of bombing was unable to deter Serbia, and later why Serbia escalated ethnic cleansing once the bombing started – to which others have struggled for answers.Footnote 94 Another study explains the July 1914 crisis leading to World War I through an analytic narrative based on perfect deterrence theory.Footnote 95 The analysis demonstrates that although general war was not sought by any of the actors, the war was no accident.

Theoretical extensions

Although Zagare and Kilgour resolve the paradox of mutual deterrence and develop a logically consistent theory of deterrence, perfect deterrence theory, further questions still remain.Footnote 96 Recent efforts to extend our understanding of deterrence have focused on three primary areas: three-actor games, bargaining, and identifying credibility.

Three-actor games

Although direct deterrence deals with two states, extended deterrence deals with a minimum of three. Werner outlines the basic logic of extended deterrence:

The attacker must decide whether or not to attack the target, which then must decide whether or not to resist. After observing both the attacker's and the target's actions, the third party must decide whether or not to come to the aid of the target if the target has in fact been attacked.Footnote 97

However, standard practice has been to include only two players in models of extended deterrence: the attacker (or challenger) and the defender. Indeed, virtually all analyses of extended deterrence have focused on only two players.Footnote 98 Thus, although Werner clearly highlights the presence and the choices of the target (as do others), the target's role in the strategic calculation involved are generally ignored. Indeed, one article that strives to determine the ‘role of the pawn in extended deterrence’ does not model the pawn (that is, target or protégé) as one of the players.Footnote 99

Therefore, an important development in deterrence theory has been to explicitly model deterrence situations wherein the choices of the target are strategically salient. Zagare and Kilgour do so through a Tripartite Crisis Game, which focuses on Protégé's potential to realign with a more reliable partner should Defender not support her following a challenge.Footnote 100 This highlights the importance of the ‘deterrence versus restraint’ dilemma in extended deterrence wherein Defender has competing interests in having a strong enough commitment to support Protégé so as to deter Challenger, but not making such a strong commitment that Protégé would be encouraged to act recklessly.

Zagare and Kilgour extend this analysis to explain British policy in the July crisis leading to the outbreak of World War I.Footnote 101 Zagare and Kilgour demonstrate why half-hearted extended deterrent signals are so often observed in international politics in general, and in Britain's attempts to deter Germany in 1914 in particular. In so doing, they demonstrate that their analysis more fully captures the dynamics of the deterrence versus restraint dilemma than Crawford's model of ‘pivotal deterrence’, which unfortunately is not based on the axiomatic base of perfect deterrence theory.Footnote 102

Quackenbush also extends deterrence theory to consider the strategic interactions of all three actors in extended deterrence.Footnote 103 He develops a Three-party Extended Deterrence Game, a formal model that matches the basic informal logic of extended deterrence. This model is the first to explicitly model the simultaneous conduct of extended and direct deterrence identified by Snyder.Footnote 104 Furthermore, the inclusion of all three players in the analysis allows examination of other issues such as the target of a challenge and alliance reliability.

Quackenbush's analysis indicates that potential challengers look to attack members of unreliable alliances.Footnote 105 Furthermore, deterrence is more likely to succeed the more highly Defender and Protégé value a war (bilateral or multilateral) with Challenger, and the less highly they value a concession to Challenger. In addition, Challenger's increasing utility for thestatus quo also increases the probability of successful deterrence. And finally, when deterrence fails, the likely target of an attack by Challenger is the more reliable of the allies – in order to keep the unreliable side on the sidelines and prevent a multilateral war.

By including all three actors within game-theoretic models, these studies have significantly improved our understanding of the dynamics of extended deterrence. Certainly, further developments in three-actor models are warranted, and are being developed.Footnote 106 As Quackenbush demonstrates, standard two-party extended deterrence games rely upon the oft-hidden assumption that states always respond to direct challenges.Footnote 107 But since this assumption directly contradicts theories of direct deterrence, analysing all three actors in extended deterrence appears to be a more consistent way of approaching the problem.

Bargaining and deterrence

Traditional analyses of International Relations have modelled decisions as stark choices between two, or sometimes three, alternatives. This is illustrated in the Unilateral Deterrence Game in Figure 3, which presents choices between ‘Cooperate’ and ‘Defect’ or ‘Concede’ and ‘Defy.’ However, states often have a wide variety of options available to them; for example, rather than just choosing between ‘attack’ or ‘not attack’, a state could do nothing, partially mobilise troops, fully mobilise, embark on a show of force, launch airstrikes, or even initiate a full-on invasion. This of course provides a much more nuanced menu of options than traditional models would suggest.

The bargaining model of war has been a recent focus of research on International Relations.Footnote 108 Although models vary, they incorporate these nuanced options within the game-theoretic model, making the stakes under consideration endogenous to the model itself. Thus, states choose not only whether to make a demand, attack, etc., but also how much to demand, attack, etc.

Werner developed the first model of deterrence to incorporate these endogenous stakes.Footnote 109 In her Modified Extended Deterrence Game, the attacker can choose the magnitude of the threat. By modelling the stakes of war as endogenous in this way, Werner is able to identify circumstances under which extended deterrence fails because the attacker deters the third party from intervening.

Langlois and Langlois have also examined the relationship between bargaining and deterrence in analyses of direct, asymmetric deterrence.Footnote 110 This allows the rivals to bargain over the terms of an alternative status quo. It also shows how war can erupt between two rational states, even when there is complete information, contrary to traditional arguments.Footnote 111

Further analyses integrating such bargaining models within studies of deterrence are likely to continue to be a fruitful avenue for research. Nonetheless, it seems important to recognise the importance of domestic politics, and its influence on the demands that states make. For example, Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman focus on two variants of their International Interaction Game: in the Realpolitik variant, the magnitude of the demand is purely endogenous to the game, whereas in the Domestic variant, the magnitude of the demand is assumed to be determined by domestic political processes, and is thus exogenous to the game.Footnote 112 Furthermore, they find that the Domestic variant does a much better job of explaining international interactions than the Realpolitik variant.

Identifying credibility

A third important focus of recent theoretical developments has been on identifying credibility. Perfect deterrence theory demonstrates that credibility is an important determinant of deterrence success. In the presence of complete information, a state's credibility is simply its preference between fighting and backing down; it either has a credible threat (that is, prefers conflict) or does not (that is, prefers backing down). However, states seldom possess such full information about their opponents.

When there is incomplete information and a state's preference between fighting and backing down is not known to its opponent, the situation is more complicated. In this case, a state's credibility is the opponent's estimate of the probability that it prefers fighting to backing down; thus, credibility varies continuously between 0 and 1.Footnote 113 Forming accurate estimates of the opponent's credibility is complicated by the reality that states have incentives to misrepresent their private information.Footnote 114 Thus, states have incentives to claim that they prefer to fight rather than back down regardless of their actual preference between the two. Thus, how can states credibly communicate their commitment to fight in the face of these difficulties?

Two recent books have sought to address this question. Sartori develops a reputational theory of diplomacy whereby defenders acquire reputations for honesty or bluffing depending on whether or not they carry through on their threats to defend against the challenger.Footnote 115 She finds that a defender's reputation for honesty enhances their threat credibility and therefore increases the likelihood of successful deterrence; on the other hand, a reputation for bluffing undermines threat credibility.

In contrast, Press proposes a ‘current calculus’ model, which evaluates credibility based on the balance of power and interests at stake, and argues that it does a better job of gauging state's perceptions of their opponents' credibility than the ‘past actions’ model, which argues that credibility depends on one's record for keeping or breaking commitments.Footnote 116 His focus on assessing the interests at stake to determine credibility is quite reasonable given that credibility deals with a state's preference between backing down and conflict.

However, it is important to distinguish between credibility and capability; whereas capability is a necessary condition for deterrence success, credibility is not.Footnote 117 But assessments of the balance of power appear to have more to do with a state's preference between conflict and the status quo than a state's preference between conflict and backing down. Therefore, it appears that Press is conflating credibility and capability. For example, he argues that Britain's threat to defend Poland in 1939 was not credible, in large part because Germany (especially Hitler) misjudged the balance of power. It seems clear that, although they could not be certain, Germany believed that British intervention was likely, and thus the British threat was credible. But as Weinberg states, ‘in August 1939 Hitler preferred to attack Poland as a preliminary to attacking France and England, but he was quite willing to face war with the Western Powers earlier if that was their choice’.Footnote 118 In other words, Germany preferred conflict with France and Britain to the status quo; despite being credible, the British threat was not capable.

Conclusion

This article sought to evaluate the current standing of deterrence theory. This was done through an examination of several important topics in deterrence theory. Contrary to Morgan,Footnote 119 there are two main theories of deterrence: classical deterrence theory and perfect deterrence theory. While both are rational-choice theories, they differ in several respects, particularly regarding their treatment of credibility. Classical deterrence theory assumes that conflict is the worst possible outcome for both sides, meaning that no retaliatory threats are credible. However, this assumption leads directly to the paradox of mutual deterrence, wherein classical theory is unable to explain deterrence success.

The paradox of mutual deterrence is solved by perfect deterrence theory, which argues that the credibility of a state's threat depends upon its preference between backing down and conflict. Therefore, scholars need to move away from the assumption that conflict is the worst possible outcome. By doing so, Zagare and Kilgour are able to develop a logically consistent theory of general deterrence that usefully explains the dynamics of deterrence in mutual, unilateral, and extended deterrence situations.Footnote 120

Although the distinction between classical and perfect deterrence theories is stark, this distinction – or at least the challenge of perfect deterrence theory – is often ignored. For example, although Morgan argues that there is only one deterrence theory, in his list of ‘standard works on deterrence theory’ any reference to perfect deterrence theory is conspicuously absent.Footnote 121 Similarly, although Sartori allows the defender's preference between war and backing down to vary in her game-theoretic model, she makes no reference to the work of Zagare or perfect deterrence theory – which is where the idea of variable threat credibility comes from – but instead relates her work to classical deterrence theorists such as Schelling and Powell.Footnote 122 More examples could be provided, but the theme is consistent.

The contrast between the two theories is not simply a matter of differences over assumptions and abstract theoretical issues. The policy recommendations of perfect deterrence theory and classical deterrence theory are diametrically opposed on many issues.Footnote 123 For example, classical deterrence theory argues that national missile defence undermines the stability of deterrence,Footnote 124 whereas an application of perfect deterrence theory demonstrates that national missile defence can enhance deterrence stability.Footnote 125 However, policy discussions in academia and government are generally based on classical deterrence theory. Given its strong empirical support, coupled with logical and empirical limitations of classical deterrence theory, perfect deterrence theory provides a much better basis for analysing various aspects of national security policy.

Clearly, classical deterrence theory constitutes the ‘conventional wisdom’ regarding deterrence. Nonetheless, classical deterrence theory is badly flawed. The (unnecessarily restrictive) assumption that conflict is always the worst possible outcome needs to be discarded. It has not proven useful for developing logically consistent and empirically accurate theory. By contrast, perfect deterrence theory provides a logically consistent alternative to understand the dynamics of deterrence. Therefore, perfect deterrence theory provides the most appropriate basis for further theoretical development, empirical testing, and application to policy.