Introduction

Jimmy Carter's accession to the US presidency in January 1977 implied a change in US foreign policy towards Latin America. Scholars argue that the Democratic administration was highly critical of the way in which the Cold War was being conducted within the continent. The Carter administration's policy of sanctions against countries that violated human rights and its lukewarm attitude towards the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua provoked a reaction against the United States that, on the one hand, united the Right and, on the other, provided a political opportunity for the reactivation of transnational anti-communist networks in the region.Footnote 1 At the same time, collaboration between Latin American ‘national security states’ in the coordination of repression against political dissidents emerged and continued beyond the winding down of Operation Condor (c. 1979–80).Footnote 2 Carter's election greatly impacted the Argentine military dictatorship (1976–83) as his administration placed restrictions on military and economic aid to the regime due to its poor human rights record. This situation led the dictatorship to forge closer ties with other governments of the same ideological stripe and to collaborate with them in what they called the ‘fight against subversion’, since – according to the military doctrines of the time – in the ‘Revolutionary War’ borders are not geographical but ideological.Footnote 3

From the early 1980s, journalistic investigations and academic research sought to demonstrate the collaboration of the Argentine military dictatorship with Central American governments in their ‘fight against subversion’.Footnote 4 The most important text in the field of historical studies on the Cold WarFootnote 5 is by Ariel Armony, who argues that the perpetrators of the ‘dirty war’ in Argentina transferred their model of massive repression to Central America in the late 1970s and early 1980s and that Argentina took ‘the place of the United States in the hemispheric struggle against communism’ when ‘subversion’ was no longer perceived as a serious threat in Argentina.Footnote 6 Armony details some of the military assistance that Argentina allegedly provided to Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua to demonstrate how ‘Argentina's military presence in these countries greatly facilitated the creation of an anti-Sandinista army’.Footnote 7

This article, which builds on previous research such as Armony's, seeks to explore the consequences of Argentine collaboration with Central American governments in their ‘fight against subversion’. However, unlike Armony's, my aim is to examine the quantitative (magnitude) and qualitative (form) dimensions of this collaboration, its timing, and the institutions and individuals responsible, to understand the effects it had on the armed forces of Guatemala and Honduras, and to estimate its possible impact on the forms of political repression there. I have selected two cases for further examination, Guatemala and Honduras, because although they differ in their links with Argentina and the United States and in the number of human rights violations committed by their repressive political regimes in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the way they carried out the systematic enforced disappearance of people was similar, making them comparable. In the urban context, a methodology associated with that used by the Argentine military dictatorship of 1976–83 was widespread: illegal detention–interrogation–disappearance, performed sequentially and supported by military intelligence. Thus, this article asks, what does my description of the transnationalisation of the Argentine military dictatorship's so-called ‘fight against subversion’ contribute to our understanding of political repression in Guatemala and Honduras in the early 1980s?

To address this question, I briefly reconstruct the characteristics of political repression in Guatemala and Honduras, paying special attention to the chronology, and review the current literature on Argentine involvement in each of the two countries. Subsequently, I analyse the evidence uncovered during my in-depth investigation carried out in official archives, mostly from Latin America, which have been opened to the public in recent years.Footnote 8 I use these sources to examine details of official, overt foreign relations and, specifically, Argentine's military relations with Guatemala and Honduras. In the next section, ‘Argentine Collaboration with Central American Governments in the “Fight against Subversion”’, I discuss the military training offered by Argentina and who received it in Guatemala and Honduras; I reconstruct two key institutions extended or created by the dictatorship to establish its presence in Central America (military attachés’ offices and the Mexico and Central America Division); and I show which Argentine military personnel were actually seconded to Central America, what tasks were assigned to them and during what period they held their posts. Finally, I compare Argentine arms sales to Guatemala and Honduras. To conclude, I relate these findings to current knowledge about political repression in the two countries during the 1980s.

In general terms, the article seeks to contribute to transnational studies of the Right during the recent history of the Latin American Cold War, to highlight the relative autonomy that Latin American actors had in forging alliances within Latin America as well as in collaborating with the US government, to shed light on a case of supra-state coordination of repression that was set up as Operation Condor was being wound down and, most importantly, to contribute social sciences evidence in cases of crimes against humanity.

Political Repression in Guatemala and Honduras

In Guatemala, state terrorism had been almost a constant since the 1954 coup d’état, although it was only from 1963 onwards, amid increasing guerrilla warfare, that the armed forces cemented themselves in power, travelled abroad for training, and incorporated then-current ideas about national security into ideology and, eventually, action. This repressive process led to genocide (1978–85) and the ‘institutional dictatorship’ of the armed forces (1982–5).Footnote 9 According to the 1999 report of the Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico (Commission for Historical Clarification, CEH), the official truth commission that documented human rights violations committed during the 34 years of internal armed conflict (1962–96), 95 per cent of the 626 recorded massacres took place between 1978 and 1984 and more than 81 per cent of the human rights violations the CEH identified were in the period 1981–3; 10 per cent of these human rights violations comprised enforced disappearances. During this period documented acts of genocide took place and 17 per cent of the country's population was forcibly displaced. It is estimated that 200,000 people were killed and disappeared during the internal armed conflict.Footnote 10

Enforced disappearance in Guatemala appeared towards the end of 1966, as in Argentina, but became a frequent practice carried out by paramilitary organisations in urban areas during the 1970s. From the government of Romeo Lucas García (1978–82) onwards, illegal detention and enforced disappearance of persons became a means of repression used by military institutions and paramilitary groups throughout the country.Footnote 11 The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) produced three reports on Guatemala. The first, published in 1981, noted that the problem of the ‘disappeared’ was one of the most serious issues of the Lucas García government.Footnote 12 The second report covered the period of the dictatorship headed by Efraín Ríos Montt (1982–3), charged with genocide in 2013 and 2018,Footnote 13 and noted differences between the situation in urban centres and rural areas. While decreasing in cities due to the dismantling of paramilitary groups operating in those areas, violence, accompanied by extreme brutality, had increased in rural areas. The second report concluded that the modus operandi of ‘kidnappings and disappearances’ remained the same as before the 1982 coup d’état.Footnote 14 The third IACHR report, from 1985, studied the years of the dictatorship of Humberto Mejía Víctores (1983–5), devoting an entire chapter to the enforced disappearance of persons. This was practised systematically and in vast numbers and, in Guatemala City, the disappearances all displayed ‘distinguishing characteristics’ that allowed different stages to be identified (detention–interrogation–disappearance).Footnote 15 The CEH report, unlike those of the IACHR, was compiled with the benefit of hindsight, and stated that the practice of enforced disappearance increased significantly between 1979 and 1983, especially in rural areas. Like the IACHR reports, it noted considerable differences between how enforced disappearances were carried out in rural and urban areas.Footnote 16

Published sources suggesting the collaboration of the Argentine military dictatorship with these repressive governments in Guatemala are very limited. The most important of these is the CEH report. It refers to a 1984 declassified Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) document which states that ‘the Guatemalan army and military intelligence (G-2) have employed a system to exploit the tactical intelligence of captured guerrillas, which was adapted from methods used by the Argentine military during the years of the Argentine civil war’.Footnote 17 In Guatemala, the two main military intelligence agencies were the army intelligence section (Dirección de Inteligencia del Estado Mayor de la Defensa Nacional – Intelligence Directorate of the National Defence Staff), known as ‘G-2’ or ‘D-2’, and a unit of the Presidential General Staff known as ‘La Regional’ or ‘El Archivo’. According to the CEH, in 1978, under the government of Lucas García, these agencies worked in close alliance, including in the training of military personnel in the field of intelligence, both abroad and within the country, with the reopening of the Escuela de Inteligencia (Intelligence Academy) at the end of 1980. The CEH notes that ‘some officers were sent abroad to take intelligence courses in countries such as Argentina, Chile, Israel and Taiwan’ and it was these officers who promoted the reopening of the Escuela de Inteligencia, closed at the end of the 1960s, and maintained it as part of G-2.Footnote 18

Other suggestions of collaboration between Argentina and Guatemala appear in interviews published by social scientist Jennifer Schirmer. A former officer of the Intelligence Directorate of the National Defence Staff and former Director of the Intelligence Academy, Major Gustavo Díaz López, told her that ‘when Guatemala was isolated between 1978 and 1984, we turned to countries such as Argentina and Uruguay’.Footnote 19 The former Defence Minister, General Héctor Gramajo, said ‘Those who trained us a lot in intelligence were the Argentines.’Footnote 20 In an interview with sociologist Manolo Vela, officer Julián Domínguez similarly recognised that the ‘tactics used in urban warfare came from the courses that army officers took on the subject in Argentina’.Footnote 21 These comments raise a number of questions to be addressed below. When did the Argentine military dictatorship's collaboration with the Guatemalan government begin? Which institutions collaborated? Who were the officers who were trained in Argentina? In what subjects were they trained? What impact did this training have?

Before addressing these questions, I will outline the historical situation in Honduras. There, the 1957 Constitution legislated military freedom from civilian control,Footnote 22 but it was following the 1963 coup d’état headed by General Oswaldo López Arellano that the military came to dominate the nation's institutions. Following defeat in the ‘Football War’ (1969) with El Salvador, military governments under López Arellano (1972–5) and Juan Alberto Melgar Castro (1975–8) ruled Honduras; these were characterised by limited social reforms – for instance regarding land tenure – corruption and drug trafficking. The end of the 1970s was marked by the drafting of a new Constitution, free and open democratic elections, and return to civilian rule in 1982 under Roberto Suazo Córdova (1982–6). Nevertheless, the military retained unofficial power, human rights violations increased, and US economic and military influence grew. The most important milestones were the appointment of General Gustavo Álvarez Martínez as Commander of the Fuerza de Seguridad Pública (Public Security Force) in 1980 and the signing of a peace treaty with El Salvador in October of that year, signalling the final end to the Football War.Footnote 23 The treaty allowed Salvadoreans access to the demilitarised zone, disbanded Organization of American States (OAS) patrols and gave the Honduran army the task of policing the border, culminating in coordinated attacks with the Salvadorean army on Salvadorean refugees who were fleeing the civil war in their country.Footnote 24 From 1982 to March 1984, when Álvarez Martínez was Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces, Honduras became directly involved in Nicaragua's internal conflict through its support for former Somocista National Guardsmen.Footnote 25

While the IACHR did not produce a report on Honduras, a human rights assessment that did circulate at the time was a 1982 Americas Watch report, which states:

The practice of arresting individuals for political reasons and then refusing to disclose their whereabouts and status seems to have become established in Honduras. In case after case, the pattern is the same … After the initial arrest, the authorities steadfastly deny the prisoner's presence in any detention center. Through the accounts of survivors, it is established that they are taken to clandestine jails, or at least to facilities with very restricted access … In the clandestine prisons, detainees are generally subjected to torture and mistreatment, including beatings, electric shocks, deprivation of food and water, isolation, and being forced for prolonged periods to wear blinding and asphyxiating hoods.Footnote 26

In 1993 the Comisionado Nacional de Protección de los Derechos Humanos (National Commissioner for the Protection of Human Rights, CNDH) presented a preliminary report on disappearances in Honduras between 1980 and 1993. The report registered a total of 179 enforced disappearances in Honduras over that period, 30 per cent of which were registered in 1981 (53 cases), while the rest were distributed more or less evenly between 1982 and 1985, with an average of 20 cases per year. In addition to the smaller number of cases, another substantial difference from Guatemala is that the majority of the disappeared were not Hondurans. In 1981, for example, three Nicaraguans, 14 Hondurans, 27 Salvadoreans, five Costa Ricans, two Guatemalans, one Venezuelan and one Ecuadorean disappeared.Footnote 27

According to the Americas Watch report, the practice of enforced disappearance was related to Argentine military advisors in Honduras,Footnote 28 a hypothesis that the CNDH took up in its 2002 analysis. Under the section heading ‘The Argentines in Honduras’, the CNDH pointed out that the presence of Argentine military personnel in Honduras began in 1980 when the Argentine military junta sent experts in the ‘fight against subversion’ and provided advice to the security forces. From 1981 onwards the junta had a second objective: training and channelling resources to anti-Sandinista paramilitary groups based in Honduran territory.Footnote 29 Honduran historian Marvin Barahona agrees that the repressive methods used ‘to guarantee internal security’ by Álvarez Martínez bore the imprint of Argentina.Footnote 30 Erick Weaver argues that Argentina's contribution, along with that of Honduras and the United States, served to train the anti-Sandinista ‘Contras’ from the early 1980s: ‘two Argentine officers were teaching at the Alto Mando y Escuela de Oficiales y del Estado Mayor in April 1982, and at least 12 Argentine officers were working clandestinely with the groups of exiles’.Footnote 31 Questions about Argentina's role in Honduras led the CNDH to resume the investigation and to request, through the Argentine government, information about the alleged secret missions. However, according to the CNDH's report, published in 1998, no response was received.Footnote 32

In the remainder of the article I reconstruct the ways in which the governments of Argentina, Guatemala and Honduras collaborated over repression, specifying the institutions through which the collaboration took place and the military advisors involved, and offer an estimate of the consequences.

Argentina's Diplomatic Relations with Guatemala and Honduras

Argentina had sought to strengthen relations with Guatemala from 1977, with the accession of Jimmy Carter as US President and his policy of sanctions against countries that violated human rights. In October 1977, the US Congress had legislated that funds for military education and training could not be allocated to the government of Argentina, nor could military credits be given to the governments of Argentina, Brazil, El Salvador or Guatemala,Footnote 33 prohibitions that were to take effect from 1 October 1978.Footnote 34 That year, the US Secretary of State pressured Argentina to receive an IACHR inspection and in October the military government issued the official invitation, but, in parallel, Argentina sought to strengthen its ties with Guatemala. When General Lucas García took office, the Argentine Ambassador received instructions from the Foreign Ministry to ‘sound out the possibilities of increasing all types of exchanges’.Footnote 35 In July 1978, the Ambassador met privately with the Guatemalan President and several of his ministers. He told the President that ‘the Latin American nations affected [by US sanctions] had to try to help each other and cooperate to resupply themselves [with sanctioned goods] − if possible within that area [Latin America]’.Footnote 36

Argentina's relations with Honduras during the Carter administration were not shaped by human rights concerns, as the Honduran government was not accused of violating human rights. The strengthening of bilateral relations was a direct response to the triumph, in Nicaragua, of the Sandinista Revolution (July 1979), as a result of which Honduras came to play a prominent geopolitical role. For Argentine Foreign Minister Carlos Washington Pastor, ‘communism’ had arrived in Nicaragua and was threatening El Salvador and Guatemala: he ‘characterized the Central American situation as very dangerous’.Footnote 37

The year 1980 marked a milestone in these relations. In that year, the Argentine Ministry of Foreign Affairs created a discrete department for ‘Central America and the Caribbean’, separate from the Latin America Department. As the Ministry characterised it, this initiated a ‘new policy in the area, supported by a programme of direct contacts through the dispatch of high-level special missions headed by the Undersecretary for Foreign Affairs and the Undersecretary for International Economic Relations, and, additionally, through increased assistance to the countries in the area’.Footnote 38 It was through these new bilateral ties that Argentina exported repressive techniques to Guatemala and Honduras.

Guatemala

According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, bilateral relations between Argentina and Guatemala during 1980 ‘underwent a very favourable turnaround and can be considered excellent because of the rapprochement between the two countries, the exchange of ideas, cooperation and mutual understanding’.Footnote 39 The improvement in relations began with the visit of an Argentine delegation to Guatemala between 4 and 7 May 1980. The Argentine Undersecretary of Foreign Affairs, Commodore Carlos Cavandoli, met with President Lucas García, Foreign Minister Rafael Castillo Valdez and other ministers. The Undersecretary explained that Argentina had defeated ‘terrorism’ and that, as a result, it was having to face attacks from countries considered ‘friends’, that this ‘Argentine experience could serve as valid suggestions for Guatemala’ and that, accordingly, ‘it was necessary for those countries in the same situation to support each other’. Guatemalan officials agreed, adding that they were managing to ‘dominate … terrorism’ whilst avoiding ‘US intervention’. The mission closed with the delegation's offer of ‘the collaboration of the Argentine information community’ – i.e. the help of an intelligence agency set up by the Argentine military dictatorship in the region – which will be detailed below.Footnote 40

Between 25 and 29 August, a Guatemalan delegation was received in Argentina. It included Foreign Minister Castillo Valdez and, significantly, Colonel Manuel Antonio Callejas y Callejas − Lucas García's Director of Intelligence – who was convicted of carrying out the enforced disappearance of 14-year-old Marco Antonio Molina Theissen, amongst other crimes, in 2018.Footnote 41 The Guatemalan Foreign Minister's priorities were an agreement on scientific and technical cooperation, a meeting with the Argentine Defence Minister and the signature of a joint declaration in which they would make clear their firm condemnation of ‘terrorism’.Footnote 42 These diplomatic meetings were followed by others. On 10 November 1980, the Vice-President of Guatemala and his entourage travelled to Argentina, for an audience with President General Jorge Videla,Footnote 43 and a few days later, from 26 to 29 November, an Argentine delegation, at the insistent request of Lucas García, travelled to Guatemala to participate in the Third Conference of Latin American Ministers and Heads of Planning.Footnote 44 These trips resulted in the scientific and technical cooperation agreement referred to above, and financial and commercial agreements.Footnote 45

Honduras

Relations with Honduras, too, intensified during 1980. In May, Argentine Undersecretary for Foreign Affairs Cavandoli visited Honduras to hold political talks with high-ranking Honduran authorities: Foreign Minister Guillermo Pérez Cadalso, President General Policarpo Paz García and Armed Forces Chief of Staff General Mario Chinchilla Cárcamo, among others. Cavandoli explained the situation in Argentina, as he had done in Guatemala, and said that the country ‘was in a position to offer Honduras useful background information on the sad experience of the process it had undergone’.Footnote 46

The Honduran Foreign Minister seems to have recognised ‘the great struggle waged by the Argentine Republic to dominate terrorism and occupy the place it deserves on its own merits in the Latin American world order’.Footnote 47 Drafts of financial, trade and scientific and technical cooperation agreements were submitted.Footnote 48 According to Cavandoli, the Honduran President praised ‘the support and assistance provided by our Armed Forces [Argentina's] to those of that country [Honduras]’, while the Chief of Staff of the Honduran Armed Forces acknowledged ‘our Armed Forces [Argentina's] for the assistance of various kinds they provide to Honduras and highlighted the quality of our officers, many of whom have served in Honduras as instructors’.Footnote 49 Between 17 and 20 August 1981, Honduran Foreign Minister César Elvir Sierra and his entourage paid an official visit to Argentina to sign the above agreements.Footnote 50

This shift in Argentina's foreign policy towards the two Central American countries gave a formal and official framework to Argentine collaboration with them in the region's ‘fight against subversion’.

Argentine Collaboration with Central American Governments in the ‘Fight against Subversion’

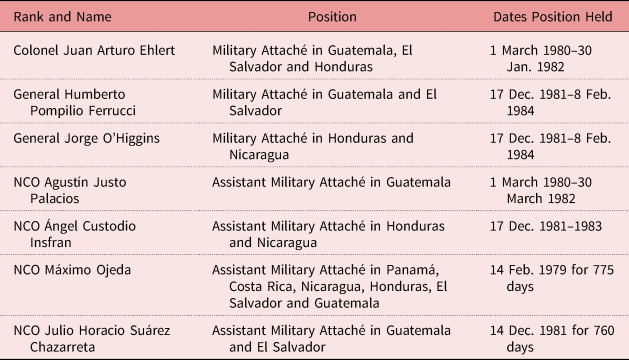

From the late 1950s, when Argentina received military counterinsurgency training from the French – especially in ‘Revolutionary War’ theory,Footnote 51 according to which control over the whole population is viewed as essential – the country disseminated these doctrines throughout Latin America. This exportation of military doctrines, including a central role for intelligence agencies, increased in the period under study.Footnote 52 The ideological and geopolitical importance that the Central American isthmus gained in the late 1970s in the whole Latin American region prompted in Argentina the creation of a series of state institutions aimed at cooperating in the ‘fight against subversion’. The military junta addressed the issue of the Argentine presence in Central America at a meeting in December 1979 and considered that one way to increase it was to open new military attachés’ offices, and/or to extend the scope of existing ones.Footnote 53 The task was assigned to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who, in October of the following year, proposed to the military junta that, among other things, the military attaché in Guatemala take on ‘the functions of naval and aeronautical attaché in that country, El Salvador and Honduras. He would also take charge of aeronautical representation in the Dominican Republic and Haiti until January 1983.’Footnote 54 From then on, the attachés’ offices, about which we still know very little, came to play a major role in the region. The military attachés listed in Table 1 were authorised to carry out special functions, including hiring civilian personnel, ‘agents’, for those functions;Footnote 55 unusually, they reported to Jefatura (Headquarters) II of the Estado Mayor General del Ejército (Army General Staff, EMGE), not to the embassies, and the diplomatic missions were not aware of all their activities.Footnote 56

Table 1. Argentine Military Attachés in Guatemala and Honduras between 1980 and 1984

Source: Promotion and military personnel files accessed through freedom of information requests.

These attachés were intelligence officers highly regarded by their superiors. For example, Juan Arturo Ehlert and Humberto Pompilio Ferrucci were decorated by the Guatemalan armed forces in 1981 and 1983 respectively, and Ehlert by the Honduran armed forces in 1981. The fact that these military attachés’ offices reported to Jefatura II is not insignificant. Directive 1/75 of the Argentine Defence Council, in 1975, gave the Argentine army primary responsibility for the ‘fight against subversion’.Footnote 57 From then on, intelligence activity was centrally run from EMGE headquarters. Intelligence Battalion 601, about which little is known, gathered information to be processed by Jefatura II. This Central de Reunión de Inteligencia Militar (Central Intelligence Gathering Centre, CIM) at EMGE was composed of personnel from the most significant civilian and military intelligence services, and, in turn, ‘was made up of different working groups or task forces that occupied different physical locations, each one in charge of the study of one or some terrorist organisations’.Footnote 58 Brigadier General Alberto Alfredo Valín, who was head of the Battalion between 1974 and 1977 and of EMGE intelligence (Jefatura II) between 1978 and 1979, stated that there were four working groups, although ‘perhaps there was a fifth group that worked with the delegate of SIDE [Secretaría de Inteligencia del Estado, State Information Secretariat] or rather this person acted as a link with SIDE to obtain information from abroad’.Footnote 59 By 1980 CIM was composed of eight groups, one of which was in charge of ‘external activities’, but it is not clear whether it continued to report to SIDE.Footnote 60 Interestingly, parallel to the creation of the Central America and Caribbean Department in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and of the military attaché's office in Guatemala, and the reorganisation of the CIM's groups, the Foreign Department of EMGE's Jefatura II set up a Mexico and Central America Division on 1 January 1980.Footnote 61 This set of state agencies, which must have worked closely together, is evidence of the political and military importance that the Argentine dictatorship gave to Mexico and Central America.

The creator and head of the Mexico and Central America Division was Lieutenant Colonel Felipe Lorenzi, an intelligence specialist, who was an ‘auxiliary in the Subversive Systems Division’ of EMGE's Jefatura II in 1978, but who from 1979 worked in its Foreign Department. In an appeal he made to the Junta de Calificación de Oficiales (Officers’ Qualification Board, JCO) in 1983, he explained, in his own words, that this Division (the Mexico and Central America Division)

did not exist as such and I was its organiser [sc. ‘founder’]. From the first binder for the registration of the information to the situation reports for the meetings with the High Commands, I played and continue to play an active part and hold primary responsibility, in which role I have maintained for five years the special confidence of the commanding and deputy commanding officers of this, my headquarters [Jefatura II].Footnote 62

Lorenzi worked in El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala between 1980 and 1981, served twice as head of EMGE's Foreign Department and had retired colonels under his command who served ‘as civilian intelligence personnel’.Footnote 63 The CNDH in Honduras compiled a list of Argentine covert operators in the region, who, given Lorenzi's assertions and the remits of the attachés’ offices, could have been placed under his authority; although, for the moment, I have not been able to verify whether they were civilian intelligence personnel working for the army.Footnote 64

The military attachés’ offices arranged meetings between military delegations from Guatemala/Honduras and Argentina, military training, scholarships, information and intelligence, military advice and arms sales. Despite a complaint by the IACHR following its visit to Argentina in 1979, complaints by the international human rights movement, and US government sanctions in respect of human rights violations committed by the Argentine dictatorship, the governments of Guatemala and Honduras requested and received assistance from Argentina in the ‘fight against subversion’.Footnote 65

As noted above, the Argentine military government had sought to expand military cooperation with Guatemala since July 1978, and the opening of a military attaché's office in 1980 made this possible.Footnote 66 It facilitated meetings with people in central positions in Guatemala's repressive structure. One of the most important of these was an extensive visit by the Argentine Foreign Minister to Guatemala between 15 and 30 October 1980, organised by Guatemala's Director of Intelligence, Colonel Callejas y Callejas.Footnote 67 Subsequently, the highest-ranking officers of the General Aguilar Mariscal Zavala military zone, which included Guatemala City, visited Argentina. On 22 November 1980, Army Chief of Staff Luis René Mendoza Palomo, Brigadier General Héctor López Fuentes, Colonel Óscar Cuyún Medina and Captain Rudy Flores Molina arrived in Argentina.Footnote 68 Mendoza Palomo saw the visit as a positive step ‘since it is necessary for the two countries to be united and for there to be effective cooperation between them’.Footnote 69 These individuals, who were in charge of the Guatemalan EMGE, were also responsible for ‘elaborating and revising the plans and programmes of instruction and training for the members of the army’ according to the constitution of the Guatemalan army.Footnote 70 The dates of these meetings in Argentina coincide with the creation and professionalisation of the Guatemalan Escuela de Inteligencia (see above), raising questions about possible links. During 1981 the binational military meetings continued. Between 6 and 10 April, another Argentine military mission arrived in Guatemala, composed of Army Chief of Staff General José Vaquero, General Héctor Norberto Iglesias, Colonel Pedro Miguel Colabella and Major José Carlos Hilgert.Footnote 71 It appears the group continued on to Miami and then returned to Argentina.Footnote 72 That visit is probably related to another that ended on 30 April, when an Argentine military delegation left Guatemala, together with one from the United States, in an Argentine Air Force plane.Footnote 73 One of the main issues discussed during these meetings was military training in Argentina. In the case of Honduras, I have found no record of this type of military mission during the period under investigation, possibly because it did not host an Argentine military attaché's office until 1982. Nonetheless, for Honduras, too, military training in Argentina was a major component of bilateral cooperation.

Military Training in Argentina

Argentina's military had experience dating from the late 1950s of providing training in counter-revolutionary warfare and intelligence, as well as of the publications to support this training; the Guatemalan military, since the government of Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes (1958–63), had sent personnel to Argentina for training. Guatemala's then Defence Minister, Otto Guillermo Spiegeler Noriega, travelled to Argentina on at least two occasions in 1979. He negotiated with several countries for Guatemalan officers to attend various courses at military academies, but he asked only Argentina for scholarships for intelligence training.Footnote 74 In January 1980, there was a change of cabinet: Spiegeler Noriega became Ambassador to Argentina and was replaced as Defence Minister by General Ángel Aníbal Guevara (a previous head of EMGE). In June 1980, the Guatemalan Vice-Minister of Defence, Colonel Roberto José Francisco Salazar Asturias, in a conversation with the Argentine military attaché, stressed the ‘need to extend [Argentina's] cooperation, especially in the area of intelligence courses’Footnote 75 and a few months later, as noted above, Director of Intelligence Callejas y Callejas visited Argentina.

In the case of Honduras, I have found a note addressed directly to General Chinchilla Cárcamo offering scholarships to Argentina's Escuela Nacional de Inteligencia (National Intelligence Academy), the military Escuela Superior Técnica (Technical College) and the Colegio Militar de la Nación (National Military College), in January 1980 for 1981 enrolment.Footnote 76

In 1978 Argentina established the ‘Curso de Inteligencia para Oficiales Extranjeros’ (Intelligence Course for Foreign Officers), for which scholarships were available (as they had traditionally been for training to foreign armies). The objective of the course, which was known as ‘COE-600’, was ‘to provide professional expertise, especially related to the LCS’; it was aimed at 14 junior officers from invited countries and two officers from the Argentine army.Footnote 77 From 1979, the number of places doubled.Footnote 78 In 1980, the purpose of COE-600 was ‘to provide professional expertise, especially related to places of temporary detention’,Footnote 79 and in 1981 the objective was to ‘provide knowledge in the area of intelligence on counter-terrorism, to achieve a doctrinal identity’.Footnote 80 What, exactly, was meant by ‘doctrinal identity’ was remains unclear. COE-600 was at a very high level: the Argentines who were qualified to teach it not only had to be officers but also to hold a specialist qualification, the ‘Aptitud Especial de Inteligencia’ (Special Intelligence Aptitude, AEI).Footnote 81

Fourteen high-ranking Guatemalan military personnel obtained the AEI between 1978 and 1982, representing 15 per cent of the total number of foreign students. Amongst these officers, who went on to play a major role in Guatemala's internal repression, were:Footnote 82

-

José Mauricio Rodríguez Sánchez, Director of Military Intelligence (G-2) during the Ríos Montt dictatorship (1982–3) and charged alongside Ríos Montt in the Ixil genocide trial;Footnote 83

-

Carlos Enrique Pineda Carranza, EMGE division chief (1973–8) and head of the Military Intelligence Directorate (D-2) in 1983;

-

Horacio Soto Salam, head of the EMGE intelligence directorate in 1981, named by human rights organisations as one of those who incinerated his victims;Footnote 84

-

Byron Humberto Barrientos Díaz, intelligence chief of the Cobán military zone, charged in 2016 with enforced disappearances and crimes against humanity in the CREOMPAZ case;Footnote 85

-

Mario Mérida González, an intelligence officer in the Puerto Barrios and Quiché military zones (1984–5), deputy head of ‘El Archivo’ and successively deputy head, then head, of D-2 (1993–4);

-

Julio Alpírez, deputy head of the ‘Kaibiles’Footnote 86 in 1982 and head of ‘El Archivo’ (1986–8), charged with the enforced disappearance of Efraín Bámaca Velásquez.Footnote 87

In contrast, I have found details for only three Hondurans who took the course (Second Lieutenants José Zambrano Carrasco and Segundo Flores Murillo in 1981 and Major Alexis Perdomo Orellana in 1982). Eight members of the Nicaraguan National Guard were students in 1978–9: this is significant in view of the Honduran government's policy of giving refuge to former Somocistas (see above).Footnote 88

But COE-600 was not the only intelligence course taught to foreign officers: SIDE, too, ran strategic intelligence courses for the senior personnel of foreign armed forces.Footnote 89 Guatemalan officers Julio Balconi and Alpírez (see above) took the SIDE course in Argentina in the early 1980s;Footnote 90 in an interview with Laura Sala the former stated that it dealt ‘eminently with state intelligence matters’.Footnote 91

In addition to these, the Argentine armed forces colleges had traditionally offered scholarships, including but not limited to intelligence training, to the Guatemalan and Honduran armed forces. My research shows that Guatemala sent several superior (five) and junior officers (five); Honduras sent lower-ranking military officers (four officers, four senior non-commissioned officers, or NCOs, six junior NCOs). Among the Guatemalan officers who enrolled at the Escuela Superior de Guerra (War College) in Argentina – commemorated by a plaque at the entrance to the institution – were Byron Disrael Lima, Director of D-2 during the Mejía Víctores dictatorship, convicted of the assassination of Bishop Juan Gerardi in 1998, and José Luis Quilo Ayuso, a psychological operations officer in EMGE and commander of a battalion in the Quiché military zone during the Ríos Montt dictatorship.Footnote 92

Foreign Missions and Military Advisors

The Argentine dictatorship also sent military personnel to the countries under investigation. The officers I have been able to identify combined high academic performance with outstanding participation in the so-called ‘fight against subversion’ in Argentina; they had the AEI training and were associated with different intelligence services.Footnote 93 While these military personnel travelled in different capacities and were assigned different tasks, they were all linked to the ‘fight against subversion’.

As noted above, the Argentine military mission that arrived in Guatemala in April 1981 included Colonel Colabella, Director of SIDE between 1977 and 1978 and then Adjutant General of EMGE,Footnote 94 and General Iglesias, who was not only a guest instructor at the School of the Americas but had a record of ‘active and determined participation in the fight against subversion’.Footnote 95 He travelled to Guatemala as a member of the General Secretariat of the Presidency and of the army's High Command. Both men belonged to the military's communications arm and were decorated in Guatemala in 1981.Footnote 96

In addition to these visits, there were longer commissions, which lasted approximately 180 days, such as on the border between El Salvador and Honduras as OAS military observers. Conflict between the two countries had been closely followed by the Argentine Foreign Ministry since 1969;Footnote 97 but after the Nicaraguan Revolution of 1979, it began to be understood through the lens of the ‘domino theory’.Footnote 98 Using this perspective, the Argentine observers on the border, rather than monitoring it, reported on the problem of ‘subversion’ in an area of coordinated attacks by the Honduran and Salvadorean armies on Salvadoreans suspected of the very crime of ‘subversion’. The Argentine observers’ mission was, in the words of the decree setting it up, ‘to supervise pacification activities and carry out a population census’.Footnote 99 However, Argentina's military observers reported to EMGE's Jefatura II and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, which had primary responsibility for the ‘fight against subversion’ in Argentina.Footnote 100 During discussions at the JCO of the promotion of one of the military observers, it was noted that the task was ‘difficult to manage, it continually produced reports on the subject … which have been useful to our intelligence because of the direct information they supply’.Footnote 101 In the period from July 1979 to 1982 the following, amongst others, worked as observers: Major Domingo Anselmo Benedetto,Footnote 102 Captain Ricardo Correa,Footnote 103 Vice-Commodore Juan José Alfonso García de DiegoFootnote 104 and Frigate Captain Oscar Alberto Arroyo.Footnote 105 Some observers continued in post after the signing of the peace treaty between El Salvador and Honduras in October 1980. As these dates coincide with the formation of El Salvador's Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, FMLN), a guerrilla group which sought to overthrow the Salvadorean government, and the beginning of Salvadorean army operations in Morazán (northern El Salvador), it can be supposed that their continued presence in the area was intended to help prevent the advance of ‘subversion’.Footnote 106

Other institutions little discussed by specialists on the subject are the Permanent Commission for Inter-American Military Communications and the Inter-American Network of Military Communications (respectively COPECOMI and RECIM, from their Spanish names), both of which were part of an inter-American military system for reciprocal assistance.Footnote 107 Patrice McSherry linked them to Operation Condor, and based them in Panama.Footnote 108 In fact these agencies which, according to a Guatemalan army directive, coordinated intelligence, communications and operations, were based in Honduras between 1980 and 1981 and in Argentina from 1982.Footnote 109 Argentina sent four people to the headquarters in Honduras: Colonels Miguel Ferrari and Elbio Ojeda, Warrant Officer José Ayala and Staff Sergeant Raúl Guajardo.Footnote 110 While those of lower rank went there for training, the colonels went as delegates and liaison officers. What is noteworthy is that, according to their files, Ojeda served in SIDE, and it was precisely from that position that he was appointed on permanent commission to Honduras, and Ferrari collaborated with the Honduran armed forces, as was acknowledged by the Undersecretary of the Ministry of National Defence and Public Security in Tegucigalpa.Footnote 111 This would indicate that the Honduran armed forces received Argentine support for internal repression between 1980 and 1981, corroborating the ‘Argentines in Honduras’ section in the CNDH report.Footnote 112 Nonetheless, I have not been able to substantiate Armony's claim that ‘there were more than 150 Argentine officers and soldiers stationed in Honduras at the end of 1981’.Footnote 113

The positions described so far were not, strictly speaking, those of military advisors. I have found no evidence in official Argentine military records that people in that position directly advised the Guatemalan armed forces. It is possible that there was professional development of a different type. A former officer in the Guatemalan army's operations section, interviewed by Sala, said that in 1981 Lucas García invited the Argentine army to ‘exchange experiences in the field of counter-insurgency’. At the military base in Puerto Barrios, where this officer attended lectures, ‘the speakers were intelligence agents supposedly working on behalf of the Argentine Armed Forces … active-duty military personnel but … not uniformed people’.Footnote 114

The military advice provided to Honduras constituted a more significant undertaking with higher-ranking staff. In January 1981, Argentina invited ‘two senior officers of the Honduran Army with the rank of colonel to visit the Escuela Superior de Guerra and the Escuela de Inteligencia’.Footnote 115 Although I have not as yet been able to document the actual visit, it may have been related to the fulfilment of a request made by the Honduran army for the appointment of two senior officers and a chief officer to ‘carry out the functions of advisors in training institutes’, functions which, according to the decree setting up the permanent military training mission in Honduras, could not ‘be carried out by any diplomatic representative or member of the military mission in the aforementioned country, given their special nature’.Footnote 116 The Argentine President therefore decreed the appointment to this military training mission, starting on 15 January 1982 and lasting for 370 days, of Colonels Carmelo Gigante and José Osvaldo Rivero (a.k.a. Riveiro/Ribeiro) and Lieutenant Colonel Abelardo de la Vega.Footnote 117 The commission was then extended, which meant that they did not return to Argentina until the beginning of 1984.Footnote 118 Precision about the date allows us to establish possible conjunctures for future investigation: the date of the beginning of Argentine military advice to Honduras coincides exactly with the transfer of RECIM and COPECOMI to Argentina, with the creation of the military attaché's office in Honduras (since it was previously based in Guatemala), and the appointment of Álvarez Martínez as Commander-in-Chief of the Honduran armed forces.

These Argentine advisors were appointed to the Honduran Escuela de Comando y Estado Mayor (Command and General Staff College), a higher-education officer-training institution which reported to the Commander-in-Chief. According to the 1984 Honduran Armed Forces Act, only graduates of this college could enter the Colegio de Defensa Nacional (National Defence College), the highest educational institution of the armed forces, which was created under the 1982 Constitution.Footnote 119 It is likely, then, that the Argentines played a very prominent role in this reform at Álvarez Martínez's direct request. McSherry, who investigated the Condor system in Central America, reports, as does Armony, that Honduras’ 3-16 Battalion received Argentine and US training and that ‘La Quinta’, the Fifth Army School in Tegucigalpa, was run by the Argentines; my own research suggests that it was the Escuela de Comando y Estado MayorFootnote 120 to which such training was possibly linked. Evidence from Argentina notes that the military advisors ‘modified [the] original programme of North American origin according to [the] model [of] the US school in Panama, and established [a] plan of studies and exercises on [the] basis [of] their own needs, seeking to shape [a] genuine national defence doctrine, with procedures similar to [those] used in our country’.Footnote 121

What was the profile of the Argentine military advisors? The pattern repeats itself: they were generally academically able, instructors, intelligence specialists and involved in the ‘fight against subversion’ in Argentina. It is noteworthy is that one of them, Riveiro (Ribeiro/Rivero), a founder of Operation Condor, now became one of the heads of the system in Honduras.Footnote 122 Riveiro was a staff officer in Army Intelligence Battalion 601 from 1975 to 1976, and from 1979 a staff officer in EMGE.Footnote 123 After his long posting to Honduras, he returned to Argentina as EMGE's Deputy Chief of Intelligence. The JOC explained, in somewhat obfuscating language, that Riveiro ‘fulfils transcendent functions ordered by the Army in the Central American Area. It is a Strategic intelligence activity that is not known to the mass of Army generals as it is a secret activity.’Footnote 124 Colonel Gigante had been a guest instructor at the School of the Americas and upon his return to Argentina worked in EMGE's Jefatura II (1975–6). In 1978 he drew up a ‘Directiva Nacional Contrasubversiva’ (National Counter-Subversive Directive), which was presented to Roberto Eduardo Viola and Carlos Suárez Mason.Footnote 125 Among other functions, in 1980 he was head of the Teaching Department, and then Deputy Director, of the Escuela Superior de Guerra.Footnote 126 On 21 December 1982, Gigante received a decoration from the Honduran armed forces. According to a note which he signed in his file, he was ‘titular’ (head) of a ‘secret’ commission so that he could perform ‘the functions of assistant intelligence advisor in the Honduran Army’.Footnote 127 Lieutenant Colonel de la Vega, another military advisor, taught ‘Intelligence’ in the Basic Command Course at the Escuela Superior de Guerra in 1980. According to his file, he carried out the function of ‘assistant psychological operations advisor to the Honduran army’.Footnote 128

The Arms Trade

In addition to training and personnel, the Argentine military dictatorship promoted the sale of arms and ammunition in Central America. Two important officers are linked to this trade: Brigadier General Horacio Argentino Barros, also a communications officer, was sent to Guatemala for several months and on two occasions during 1977 as Director of Development at Fabricaciones Militares, Argentina's state-owned weapons manufacturer;Footnote 129 Lieutenant Colonel Orlando Manuel Barril was Director of Arms and Ammunition Sales at Fabricaciones Militares in 1983. We know from his file that he travelled to El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala in June 1982 to ‘close sales attempts already under way, reactivate negotiations, sign contracts for materials already awarded and promote the expansion of products manufactured by the Board of Fabricaciones Militares’.Footnote 130 In 1980, on at least one occasion, the company sent its arms catalogue to Guatemala.Footnote 131

The offer of arms was accompanied by their financing: in January 1982 the Argentine Central Bank authorised Fabricaciones Militares ‘to finance the export of secret war materiel to the Republics of Honduras and Guatemala … to the value of US$ 10 and 30 millions, respectively’.Footnote 132 The bank's official document states that ‘the petitioner argues reasons of political and strategic interest to carry out this operation, approved by the Army Commander-in-Chief’. The Argentine military dictatorship also offered Guatemala ‘naval equipment’ and Pucará aircraft, specially designed for counter-insurgency missions.Footnote 133 It is worth noting, however, that Honduras is the only country to which we have evidence of weapons having been delivered.Footnote 134

Conclusions

This study, based on official sources held by different Latin American repositories, makes it possible to confirm that Argentina participated in the ‘fight against subversion’ in Guatemala and Honduras during the Argentine military dictatorship of 1976–83. The strengthening of ties between Argentina and Guatemala and, later, Honduras occurred because both countries were sanctioned, especially by the US government, for the enormous number of human rights violations perpetrated by their regimes at the time. The triumph of the Sandinista Revolution in 1979 was therefore an accelerator rather than the main cause of the ties. Following the maxim that countries fighting subversion should support each other so as not to be isolated or intervened against, visits and the signing of financial, commercial and scientific−technical cooperation agreements took place. There were regular meetings with the Guatemalan government; not so with the Honduran government. In 1980 the Argentine government created a whole series of institutions (the Central America and Caribbean Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; the military attachés’ offices; the Mexico and Central America Division within EMGE's Foreign Department) that focused on Guatemala and Honduras; many of these reported to EMGE's Jefatura II, which had primary responsibility for the ‘fight against subversion’.

The meetings between military delegations channelled through the attachés’ offices were key for the management of military training, scholarship applications, intelligence, military advice and arms sales. As regards training, that of Guatemalan and Honduran military personnel in Argentina differed substantially. While Guatemala sent several chief officers and junior officers to take (mostly) intelligence courses at both the Escuela de Inteligencia and SIDE, Honduras sent fewer lower-ranking military personnel. Officers were trained in ‘revolutionary warfare’, tactical and strategic intelligence, interrogation, ‘counter-subversion’ and ‘temporary places of detention’. In Guatemala, this training had an impact on the professionalisation of the intelligence discipline, with the creation of its Escuela de Inteligencia in 1980 mentioned above, and on the instruction of military personnel who went on to occupy leadership positions and were at the head of the ‘fight against subversion’ in their country. Intelligence was the backbone supporting systematic enforced disappearances, something that was been proved in Argentina by Nunca Más (Never Again), the report on human rights abuses by official agencies.Footnote 135 The intelligence service repeatedly used the strategy of illegal detention−interrogation−disappearance in clandestine centres created for this purpose in order to obtain information leading to the heads of the ‘subversion’; and it was precisely this scenario which began to be seen in Guatemala in a systematic way from 1980 onwards, especially in the repression carried out in urban areas. Yet until the Molina Theissen trial in 2018, which demonstrated the role of the intelligence services in enforced disappearances, the Guatemalan judicial system absolved the intelligence directorates of crimes against humanity.Footnote 136

This investigation shows that Argentine military personnel travelled to promote courses and weapons and to offer intelligence; but, above all, it has been able to identify both the Honduras-based institutions (COPECOMI and RECIM) which brought together different armed forces to coordinate intelligence and operations and the Honduran institution which received Argentine military advice; to name three Argentine military advisors; and to give the date on which the advice began. The Argentine advisors worked in the Honduran Escuela de Comando y Estado Mayor from January 1982 to January 1984, modifying the curriculum to create a national defence doctrine; such advice was not offered to Guatemala. At around the same time the military attaché's office was established in Honduras and COPECOMI and RECIM were moved to Argentina. In Honduras, the highest number of disappeared detainees, most of whom were not Hondurans, corresponds to the period when Argentine military officers with the grade of colonel were members of these institutions and collaborated with the Honduran armed forces. From 1982, the Argentina presence in Honduras was directly related to the Contras, as Armony has pointed out, although effective collaboration seems to have been short-lived: the Malvinas (Falklands) War (April–June 1982) and democracy (1983) slowed down the process of collaboration but did not immediately end it.Footnote 137

It is important to reiterate that Argentina also offered the financing of arms and ammunition to the tune of US$ 10 million to Honduras and US$ 30 million to Guatemala. As with the financial agreements, the money for arms sales to Guatemala's military dictatorship was far greater than that given to Honduras. If we compare these figures with those offered by the United States, they are striking: US economic aid to Guatemala was US$ 11.4 million in 1980, US$ 16.7 million in 1981 and US$ 13.5 million in 1982, and there was no military aid until 1985. In the case of Honduras, while economic aid dominated, military aid was only US$ 4 million in 1980, $8.9 million in 1981 and US$ 31.3 million in 1982, which shows that Argentina's support was indeed substantial.Footnote 138

The work presented in this article raises many issues that need to be explored further. Firstly, what were the specific characteristics of Argentina's collaboration with the United States, and with each country in Central America in the ‘fight against subversion’? Each national case must be examined individually rather than making regional generalisations. Secondly, what were the links between this cooperation and Operation Condor? Although some Argentine actors and institutions were involved in both, the specific cases of alleged repressive coordination and the question as to who was in charge (particularly former SIDE agents) are still being investigated.

To conclude, it is important to highlight the agency of Latin American actors and institutions in order to arrive at new meanings of the recent history of the Latin American Cold War. This research is an example of what new understandings emerge from this approach and an invitation to continue developing this type of investigation, which also shines a light on those individuals spreading repressive practices.

Acknowledgements

I thank the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica, the UBA and CONICET for supporting my research. I also acknowledge the help of the institutions named in note Footnote 8, in addition to the following: in Argentina: Grupo de Estudios sobre Centroamérica, Instituto de Estudios de América Latina y el Caribe, UBA; Equipo de Relevamiento y Análisis en los Archivos de las Fuerzas Armadas, Ministerio de Defensa; Dirección de Transparencia Institucional, Ministerio de Defensa; Dirección Nacional de Asuntos Jurídicos Nacionales en Materia de Derechos Humanos, Secretaría de Derechos Humanos; in Guatemala: Instituto de Estudios Comparados en Ciencias Penales; Asociación para el Avance de las Ciencias; Oficina de Derechos Humanos del Arzobispado de Guatemala; Asociación Familiares de Detenidos-Desaparecidos de Guatemala; in Mexico: Seminario de Estudios sobre Centroamérica, Instituto Mora y CIALC, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.