Introduction

Recent decades of research have provided ample evidence of the extended effect of SES-related differences in children's early linguistic experience on language development (Hart & Risley, Reference Hart and Risley1995; Hoff, Reference Hoff2003; Hurtado, Marchman & Fernald, Reference Hurtado, Marchman and Fernald2008; Huttenlocher, Vasilyeva, Cymerman & Levine, Reference Huttenlocher, Vasilyeva, Cymerman and Levine2002; Lieven, Reference Lieven2010; Weisleder & Fernald, Reference Weisleder and Fernald2013; Weizman & Snow, Reference Weizman and Snow2001). The majority of the studies that have maintained the existence of a word gap between low and middle SES children's early linguistic experience (Hoff, Reference Hoff2003; Rowe, Reference Rowe2008, Reference Rowe2012) were based on the quantity of tokens to which children were exposed. A few of these studies also provided evidence regarding general indicators of qualitative features of CDS at a global level, such as lexical diversity and syntactic complexity, measured by the mean length of utterance (Hoff, Reference Hoff2003; Huttenlocher, Waterfall, Vasilyeva, Vevea & Hedges, Reference Huttenlocher, Waterfall, Vasilyeva, Vevea and Hedges2010; Rowe, Reference Rowe2008, Reference Rowe2012). Nonetheless, a growing body of research suggests that other qualitative dimensions of input that are deployed at the proximal context of parent-child interactions also constitute a pathway through which SES may exert its influence on children's language ability (Pace, Luo, Hirsh-Pasek & Golinkoff, Reference Pace, Luo, Hirsh-Pasek and Golinkoff2017; Sperry, Sperry & Miller, Reference Sperry, Sperry and Miller2019).

Language input does not occur in isolation: the social affordances in which language is embedded make up the interactional quality of language. Studies have shown differences in the pragmatic function of child directed utterances: low-SES mothers’ utterances often direct their children's behavior and middle-SES mothers’ utterances usually elicit conversation from their children (Hart & Risley, Reference Hart and Risley1995; Hoff, Reference Hoff2006, Reference Hoff2013; Ramirez, Migdalek, Stein, Cristia & Rosemberg, Reference Ramirez, Migdalek, Stein, Cristia and Rosemberg2016; Mastin, Marchman, Elwood-Lowe & Fernald, Reference Mastin, Marchman, Elwood-Lowe and Fernald2016; Kuchirko, Schatz, Fletcher & Tamis-LeMonda, Reference Kuchirko, Schatz, Fletcher and Tamis-LeMonda2019; Rowe, Reference Rowe2008; Rowe et al., Reference Rowe, Coker and Pan2004; Snow et al., Reference Snow, Arlman-Rupp, Hassing, Jobse, Joosten and Vorster1976). They have also identified SES variations in the semantic and temporal contingency of caregiver's responses to children's early vocalizations (Hoff, Reference Hoff2003; McGillion et al., Reference McGillion, Herbert, Pine, Keren-Portnoy, Vihman and Matthews2013; Tamis-LeMonda, Kuchirko & Song, Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Kuchirko and Song2014; Vanormelingen & Gillis, Reference Vanormelingen and Gillis2016).

At the very local level of interaction Tal and Arnon (Reference Tal and Arnon2018a)'s study provided some evidence of SES differences in the way caregivers structure the information, wrapping it in sequences of partial self-repetitions. The term variation sets was coined by Küntay and Slobin (Reference Küntay, Slobin, Slobin, Gerhartd, Kyratzis and Guo1996), to conceptualize these sequences that include a lexical item in reformulated utterances. Although they vary in form, they are addressed to children with a constant pragmatic intention, in order to play diverse functions in interaction (regulate their action, provide or request information). In Tal and Arnon (Reference Tal and Arnon2018a)'s study, high SES Scottish and Israeli mothers’ CDS included a greater proportion of words and utterances in variation sets than low SES mothers’ CDS. Yet, in line with previous studies on other input measures (Stein, Menti & Rosemberg, Reference Stein, Menti and Rosemberg2021; Sperry et al., Reference Sperry, Sperry and Miller2019; Weisleder & Fernald, Reference Weisleder and Fernald2013), variability was high in both social groups. SES differences were also found in the pragmatic function of the variation sets produced by the Scottish mothers: middle SES children heard more variation sets with an ideational function (that is, to provide information) than their low SES peers (Tal & Arnon, Reference Tal and Arnon2018b).

It was noteworthy that, Tal and Arnon's (Reference Tal and Arnon2018a, Reference Tal and Arnon2018b) results were based on data collected in parent-child quasi-experimental relatively brief play situations. Evidence from a few studies indicates that these situations, delimited in time, space and objects, elicit dense language input, and tend to give rise to referential language. Conversely, in the ebb and flow of everyday life children participate in diverse activities, which may vary greatly between social groups (Psaki et al., Reference Psaki, Seidman, Miller, Gottlieb, Bhutta, Ahmed, Ahmed, Bessong, John, Kang, Kosek, Lima, Shrestha, Svensen and Checkley2014; Vernon-Feagans, Garrett-Peters, Willoughby, Mills-Koonce & the Family Life Project Key Investigators, Reference Vernon-Feagans, Garrett-Peters, Willoughby and Mills-Koonce2012; Sperry et al., Reference Sperry, Sperry and Miller2019). In these everyday activities they interact with multiple participants (see Sperry et al., Reference Sperry, Sperry and Miller2019 regarding differences between social groups in the amount of input to children stemming from multiple participants), and language occurs naturally, shows fluctuations, is interspersed with silences, and may present frequent overlapping conversations among participants (Bergelson, Amatuni, Dailey, Koorathota & Tor, Reference Bergelson, Amatuni, Dailey, Koorathota and Tor2018; Tamis-LeMonda, Kuchirko, Luo, Escobar & Bornstein, Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Kuchirko, Luo, Escobar and Bornstein2017). This may affect differently the presence and proportion of words and utterances included in variation sets in socio-economically diverse households. In addressing this issue, the present paper adopts a naturalistic perspective, looking at the relationship between SES, the type of activity and the proportion of words and utterances in variation sets in CDS, as well as the pragmatic function they play in the interactions that constitute the linguistic environments of Spanish-speaking Argentinian toddlers – an understudied population.

To this end, the following sections review previous research that consider: a) variation sets’ characteristics, b) the pragmatic function of variation sets in CDS and c) contextual differences that may impact on variation sets: c.i) activity type and c.ii) SES. Based on these earlier findings we present our research questions.

a) Variation sets’ characteristics

One of CDS's main features is its repetitiousness (Söderström, Reference Söderström2007). Studies have identified different types of repetitions, such as partial or exact repetitions and have shown its correlation with language growth (Cameron-Faulkner, Lieven & Tomasello, Reference Cameron-Faulkner, Lieven and Tomasello2003; Kavanaugh & Jirkovsky, Reference Kavanaugh and Jirkovsky1982; Kaye, Reference Kaye1980; McRoberts, McDonough & Lakusta, Reference McRoberts, McDonough and Lakusta2009; Papousek, Papousek & Haekel, Reference Papousek, Papousek and Haekel1987; Stern, Spieker & MacKain, Reference Stern, Spieker and MacKain1982). Variation sets specifically refer to successive utterances addressed to young children, which include partial self-repetitions that have a constant pragmatic intention but varying form, such as:

Example from the Argentinian corpus:

Mamá: &ah rosquitas Guille se las agarró todas.

Mamá: vení, vamos a poner las rosquitas acá.

Mamá: tomá, poné unas rosquitas.

Mother: &oh cookies Willie took them all.

Mother: come, we will put the cookies here.

Mother: here you are, put some cookies there.

Küntay and Slobin (Reference Küntay and Slobin2002)'s thorough examination of these sequences of utterances in CDS revealed that variation sets are mostly produced around a verb and its arguments, and are characterized by three types of phenomena occurring across successive utterances: lexical substitution or rephrasing, addition or deletion of specific reference, and reordering. The same lexical items are overlapped across adjacent utterances within a short time frame with regard to the same situation. Input is organized according to patterns that encompass an entire set of cues that allow the deciphering of the relevant dimensions of lexical, morphological and syntactic variation in the language. This might help the child distinguish nouns from verbs and extract the relevant elements enhancing their morphological, lexical, and syntactic development. The alignment of the repeated parts of the utterances may facilitate the comparison of those utterances and help the learning child understand the sequential relations between words, as well as the properties of words belonging to the same word categories (Onnis, Edelman, Esposito & Venuti, Reference Onnis, Edelman, Esposito and Venuti2021).

Küntay and Slobin (Reference Küntay, Slobin, Slobin, Gerhartd, Kyratzis and Guo1996)'s first evidence of the prevalence of variation sets structure in CDS was obtained from the analysis of the interactions between a Turkish mother and her daughter when she was 1:8 to 2:3 years old. They found that variation sets account for approximately 20% of the utterances addressed to the child. This finding was replicated in several other studies with different languages (Tal & Arnon, Reference Tal and Arnon2018a; Waterfall, Reference Waterfall2006; Waterfall, Sandbank, Onnis & Edelman, Reference Waterfall, Sandbank, Onnis and Edelman2010; Wirén, Nilsson Björkenstam, Grigonytė & Cortes, Reference Wirén, Nilsson Björkenstam, Grigonytė and Cortes2016).

The pattern of this structural property on input to children was also longitudinally depicted. For instance, Waterfall (Reference Waterfall2006) showed that the percentage of variation sets declines in the second year of life, accompanied by a decrease in their length, measured in the quantity of utterances included in variation sets. Waterfall maintains variation sets are mostly used by caregivers before children have started to speak; indeed, their decrease with age may be related to an increase in caregivers’ expansions of children's previous utterances when children can communicate better using speech. Wirén et al. (Reference Wirén, Nilsson Björkenstam, Grigonytė and Cortes2016) also found a decrease of variation sets as children grew older: 8 month olds heard more proportion of utterances in variation sets than 2 year olds in Swedish.

Extant evidence shows the facilitative role of variation sets and its relation to better language outcomes in naturalistic and experimental studies (Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Waterfall, Lotem, Halpern, Schwade, Onnis and Edelman2010; Onnis, Waterfall & Edelman, Reference Onnis, Waterfall and Edelman2008; Schwab & Lew-Williams, Reference Schwab and Lew-Williams2016; Waterfall, Reference Waterfall2006; Waterfall et al., Reference Waterfall, Sandbank, Onnis and Edelman2010). Waterfall (Reference Waterfall2006) showed that words as well as syntactic structures heard by the child inside variation sets were produced earlier than other words that did not appear inside variation sets. The facilitative role of variation sets was also depicted by Onnis et al. (Reference Onnis, Edelman, Esposito and Venuti2021), who found that mothers employed them with their atypical children with low cognitive abilities at older ages than with typical children, probably as a way of simplifying the communicative interaction.

b) The pragmatic function of sequences of variation sets in CDS

Why do variation sets occur so frequently in early interactions between caregivers and children? As shown by the aforementioned studies the lexical repetition in variation sets may serve to capture and maintain children's attention and this, together with facilitating children's language development, might explain why caregivers resort to them as a means of getting the child to do, understand or attend something related to the ongoing activity (Rowe & Snow, Reference Rowe and Snow2019).

In their single child study, Küntay and Slobin (Reference Küntay and Slobin2002) found that variation sets played different pragmatic functions in interactions: most of them were used to query information, followed by commands with a regulatory function and to a lesser extent with an ideational function that provides information. Their longitudinal analysis showed an increase in variation sets used with a regulatory function.

Tal and Arnon's study (2018b) extended Küntay and Slobin (Reference Küntay and Slobin2002)'s, looking at differences in the pragmatic function of variation sets in an English corpus (Howe, Reference Howe1981) made up of 40 minutes free play at home situations between 16 children and their mothers when children were 1:6–1:8 and five months later. Their findings showed that middle SES, as compared to low SES, mothers used more variation sets with an ideational function. However, they did not find SES differences in variation sets that were oriented to ask for information. Although they found more variation sets with a regulatory function in the low SES group the difference did not reach significance. The authors opened up the question of whether any kind of variation set may impact on language learning. They suggested that perhaps only variation sets that have an ideational function enhance learning, as they expand on the linguistic content of the conversation. This idea follows in line with previous studies analyzing the entire CDS which showed a positive effect of commentaries that serve an ideational function and a negative effect of directives with a regulatory function on vocabulary growth and word processing (Mastin et al., Reference Mastin, Marchman, Elwood-Lowe and Fernald2016). However, other research has shown that the use of commands to regulate children's behaviour favours the comprehension of verbs (Rosemberg & Alam, Reference Rosemberg and Alam2021; Goldfield, Reference Goldfield2000).

Tal and Arnon's (Reference Tal and Arnon2018b) aforementioned analysis on the pragmatic function that variation sets serve in the interaction was based on data collected in quasi-experimental at-home situations: the children interacted only with their mother in a play activity that organized the dyads’ interactions. Nonetheless in their daily life, children interact with a variety of other adults and children and participate in multiple social and routine maintenance activities, which may vary greatly in different social and cultural groups (Psaki et al., Reference Psaki, Seidman, Miller, Gottlieb, Bhutta, Ahmed, Ahmed, Bessong, John, Kang, Kosek, Lima, Shrestha, Svensen and Checkley2014; Vernon-Feagans et al., Reference Vernon-Feagans, Garrett-Peters, Willoughby and Mills-Koonce2012). For instance, Sperry et al.'s (Reference Sperry, Sperry and Miller2019) and Casillas, Amatuni, Seidl, Söderström, Warlaumont and Bergelson's (Reference Casillas, Amatuni, Seidl, Söderström, Warlaumont and Bergelson2017) studies revealed that definitions of verbal environments that exclude multiple caregivers may underestimate the amount of speech addressed to the child.

c) Contextual differences that may impact on variation sets

c.i) Activity type

Roy, Frank, DeCamp, Miller and Roy (Reference Roy, Frank, DeCamp, Miller and Roy2015)'s dense longitudinal investigation of a single child provided evidence that the spacial, temporal and linguistic dimensions of the activity context in which a word appears was a better predictor of word acquisition than lexical frequency, mean length of the utterance or word length. This finding motivated further naturalistic studies that examine the quantity (Glas, Rossi, Hamdi-Sultan & Batailler, Reference Glas, Rossi, Hamdi-Sultan and Batailler2018; Söderström & Wittebolle, Reference Söderström and Wittebolle2013; Weisleder, Mendelsohn, Villanueva, Canfield, Cates, Seery, Vasques & Robertson, Reference Weisleder, Mendelsohn, Villanueva, Canfield, Cates, Seery, Vasques and Robertson2019) and quality (Tamis-LeMonda, Custode, Kuchirko, Escobar & Lo, Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Custode, Kuchirko, Escobar and Lo2018; Rosemberg, Alam, Audisio, Ramirez, Garber & Migdalek, Reference Rosemberg, Alam, Audisio, Ramirez, Garber and Migdalek2020) of CDS in different types of activities.

In order to better understand the impact of the activity on the input, some of these studies grouped the activities according to the child engagement and/or the social and functional context. Glas et al. (Reference Glas, Rossi, Hamdi-Sultan and Batailler2018) in a corpus of two children speaking three different languages distinguished between “solitary activities” in which the child explored the environment or play by herself, “maintenance activities” which included feeding, bath and hygiene, and “social activities”, such as play, book reading and talk between child and adults. Their results showed greater differences in CDS across activity types than across languages. Weisleder et al. (Reference Weisleder, Mendelsohn, Villanueva, Canfield, Cates, Seery, Vasques and Robertson2019) categorized the activities in “child engaging activities”, such as play and booksharing and “non-child engaging activities”, that included meals and grooming. Their results revealed a greater density of CDS in child engaging activities, but also higher variability between the families in this type of activity. Rosemberg et al. (Reference Rosemberg, Alam, Audisio, Ramirez, Garber and Migdalek2020) took into account whether the child was the focus of the activity and the degree of social interaction in order to cluster activities in three groups: child centered social activities, child centered solitary activities and household centered activities. In line with Weisleder et al. (Reference Weisleder, Mendelsohn, Villanueva, Canfield, Cates, Seery, Vasques and Robertson2019), they found that household centered activities had less variability between the families than child centered ones.

It is worth noting that the type of activity has been found to predict the pragmatic function of the child directed utterances (Altınkamış, Kern & Sofu, Reference Altınkamış, Kern and Sofu2014; Rosemberg et al., Reference Rosemberg, Alam, Audisio, Ramirez, Garber and Migdalek2020; Tamis-LeMonda et al., Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Custode, Kuchirko, Escobar and Lo2018). Tamis-LeMonda et al. (Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Custode, Kuchirko, Escobar and Lo2018) found that US American middle class mothers directed more referential language utterances that provided or queried information about objects or activities, during book-sharing activities than during feeding, grooming and transition moments.

Despite the context of activity being an important predictor of language input, to our knowledge no previous study has specifically analyzed the relationship between variation sets in CDS and the ongoing activity. Focusing on this relationship is particularly relevant considering Küntay and Slobin (Reference Küntay and Slobin2002)'s noteworthy observation about the pragmatics of variation sets: they are used by the speaker as a way of getting the child to do, understand or attend something related to the ongoing activity.

c.ii) SES

The way activities unfold differ between social and cultural groups and this may impact differently on CDS. Rosemberg et al. (Reference Rosemberg, Alam, Audisio, Ramirez, Garber and Migdalek2020) found an effect of SES and the type of activity on the pragmatic function of utterances in the input directed to socio-economically diverse Argentinian children. Children from middle SES heard more requests. Likewise, this type of utterance was more frequent when the child was participating in social activities – book reading, organized play or conversations between adults and children – than when they were engaged in solitary activities – such as exploratory play with objects, watching tv or physical play-. Conversely, children from low SES heard more commands aimed to regulate the child's activity. Interestingly, in both social groups commands were more frequent during child centered solitary activities and less likely in child centered social ones. An interaction was found between SES and activity type such that when the command was oriented to an entity and not to an action, the probability was higher in child-centered activities in middle SES.

The differences found by Rosemberg et al. (Reference Rosemberg, Alam, Audisio, Ramirez, Garber and Migdalek2020) may be explained by SES differences observed in the ebb and flow of everyday life. In low SES populations extended households are more frequent. Children interact with multiple participants (Psaki et al., Reference Psaki, Seidman, Miller, Gottlieb, Bhutta, Ahmed, Ahmed, Bessong, John, Kang, Kosek, Lima, Shrestha, Svensen and Checkley2014; Vernon-Feagans et al., Reference Vernon-Feagans, Garrett-Peters, Willoughby and Mills-Koonce2012; Sperry et al., Reference Sperry, Sperry and Miller2019) in activities which are not frequently centered on them, and usually they have less access to toys, books and other child specific objects (Bradley & Crowey, Reference Bradley and Corwin2002).

The Argentinian context

In Argentina, and particularly in the Buenos Aires metropolitan area, the biggest of the country, there are great levels of structural inequality that materialize in the income of families and their access to goods and services. According to official data, in the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires, more than 31% of the families live below the poverty line (INDEC, EPH, 2020). This is equivalent to more than 1,500,000 families that can satisfy neither basic feeding needs, nor other needs such as clothing, transportation, education and health, among others. Additionally, there is a high level of segregation; and material living conditions, such as access to sewage networks and running water, are very different between slums (known as villas de emergencias) and poor neighborhoods compared to the residential neighborhoods where families of middle and high SES live. Low SES families tend to be larger, with a greater number of children and also adults, considering that in many cases three generations share the home. This gives rise to overcrowded living conditions that affect more than 22% of the households (INDEC, EPH, 2014).

In turn, these living conditions are intertwined with differences in access to education. Adults in low SES households have less than 12 or 7 years of schooling (Abelenda, Canevari & Montes, Reference Abelenda, Canevari and Montes2016) and attend institutions with fewer material and pedagogical resources (Tiramonti, Reference Tiramonti2004).

The current study

The above mentioned studies that have identified SES differences on the proportion of words and utterances and on the pragmatic function of variation sets were based on data collected in brief child-mother play situations; thus, they do not allow to infer the relationship between variation sets and the type of activity. The latter may be particularly relevant considering the extant evidence regarding the impact of the type of activity on the quantity of CDS (Glas et al., Reference Glas, Rossi, Hamdi-Sultan and Batailler2018; Söderström & Wittebolle, Reference Söderström and Wittebolle2013; Weisleder et al., Reference Weisleder, Mendelsohn, Villanueva, Canfield, Cates, Seery, Vasques and Robertson2019) as well as on the pragmatic function of child directed utterances (Tamis-LeMonda et al., Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Custode, Kuchirko, Escobar and Lo2018; Rosemberg et al., Reference Rosemberg, Alam, Audisio, Ramirez, Garber and Migdalek2020).

Research showing differences in children's everyday activities in low and middle socio-economic households (Psaki et al., Reference Psaki, Seidman, Miller, Gottlieb, Bhutta, Ahmed, Ahmed, Bessong, John, Kang, Kosek, Lima, Shrestha, Svensen and Checkley2014; Vernon-Feagans et al., Reference Vernon-Feagans, Garrett-Peters, Willoughby and Mills-Koonce2012) raise the question of whether the type of activity may affect differently the characteristics of variation sets in the speech directed to socio-economically diverse children in their daily life. Naturalistic studies may unveil a particular portrayal of reality not clearly depicted in quasi-experimental studies (Bergelson et al., Reference Bergelson, Amatuni, Dailey, Koorathota and Tor2018; Tamis-LeMonda et al., Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Kuchirko, Luo, Escobar and Bornstein2017). Hence, the present investigation focuses on the impact of SES and the type of activity on the proportion of words and utterances in variation sets and the pragmatic functions they adopt in the CDS in an Argentinian Spanish speaking naturalistic corpora. We seek to address the following questions:

1. What effect do socio-economic status (SES) and the type of activity have on the proportion of words and utterances included in variation sets in CDS?

2. What effect do SES and the type of activity have on the pragmatic function of variation sets in CDS?

Previous work (Tal & Arnon, Reference Tal and Arnon2018a) led us to predict a greater proportion of words and utterances in variation sets in middle SES than in low SES. Based on Tal and Arnon (Reference Tal and Arnon2018b)'s study and other research on the pragmatic functions of child directed utterances (Hart & Risley, Reference Hart and Risley1995; Hoff, Reference Hoff2006, Reference Hoff2013; Kuchirko et al., Reference Kuchirko, Schatz, Fletcher and Tamis-LeMonda2019; Mastin et al., Reference Mastin, Marchman, Elwood-Lowe and Fernald2016; Ramirez et al., Reference Ramirez, Migdalek, Stein, Cristia and Rosemberg2016; Rowe, Reference Rowe2008; Snow et al., Reference Snow, Arlman-Rupp, Hassing, Jobse, Joosten and Vorster1976) we expect a greater proportion of variation sets aimed to provide information (ideational pragmatic function) in middle SES families. The above cited studies have also shown a greater amount of commands in low SES CDS. Hence, we expect variation sets in this social group to be employed more frequently to regulate children's behaviour (regulatory pragmatic function). Lastly, considering previous studies with naturalistic data that have addressed the relationship between activities and language input (Glas et al., Reference Glas, Rossi, Hamdi-Sultan and Batailler2018; Rosemberg et al., Reference Rosemberg, Alam, Audisio, Ramirez, Garber and Migdalek2020; Roy et al., Reference Roy, Frank, DeCamp, Miller and Roy2015; Tamis-LeMonda et al., Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Custode, Kuchirko, Escobar and Lo2018), we predict that the type of activity will influence the proportion of child directed words/utterances included in variation sets as well as the pragmatic function served by variation sets. Based on Rosemberg et al. (Reference Rosemberg, Alam, Audisio, Ramirez, Garber and Migdalek2020) and Tamis-LeMonda et al. (Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Custode, Kuchirko, Escobar and Lo2018) studies, which found more referential language in child centered social activities, such as book-sharing, adult-child conversations and organized play, we expect a greater proportion of variation sets and in particular with an ideational and querying pragmatic function in this type of activities.

Method

Ethics statement

This research was conducted following the ethical regulation 5344/99 by the National Scientific and Technical Research Council of Argentina (CONICET) and was approved and supervised by CONICET's committee. Participating parents provided written informed consent both for themselves and on behalf of their children.

Participants

Thirty-two children (age: 14.3 months) and their families living in the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires participated in the study. They were drawn from a larger sample including socioeconomically diverse children who were followed longitudinallyFootnote 1 (Corpus: Rosemberg, Alam, Stein, Migdalek, Menti & Ojea, Reference Rosemberg, Alam, Stein, Migdalek, Menti and Ojea2015–2016)Footnote 1.

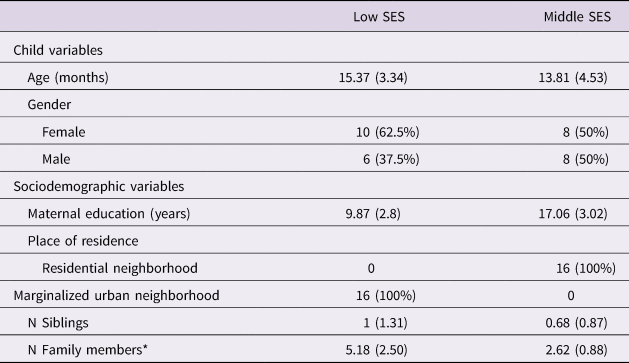

In order to select children representative of both ends of the SES spectrum in Argentinian cities, two parameters were considered: education and neighborhood. A family was categorized as middle SES if at least one of the parents had completed a university degree or similar (e.g., a teaching degree) – which translates into at least four years of further education after secondary school – and the family lived in a residential neighbourhood. In contrast, in low SES families adults had at most completed secondary school and lived either in urban marginalized slums, known as villa de emergencia, in the city or in a suburban impoverished neighbourhood. SES groups were balanced in terms of age and gender. Spanish was the first language in all the families and the one used in everyday interactions (see in Table 1 participants’ characteristics).

Table 1. Description of participants. Means/N (SD/%) of selected variables in each SES group

* The amount of family members living in the house does not include the focal child

Procedures

Data collection

Caregivers were asked to have their children wear vests equipped with digital devices in order to record every natural interaction (at home or during occasional outings) held throughout a period of four hours without the presence of the researcher. Families were asked to interact as they normally would.

Transcription

All the speech that occurred in the middle two hours of each recording – 64 hours in total – was transcribed by well-trained research assistants, using the CHAT format (Codes for Human Analysis of Transcripts, MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney2000). We did not transcribe the first hour in order to guarantee that the family would be more used to the presence of the recorder and would act more naturally. Also, we decided to exclude the last hour because in many cases the child was asleep. The speech was segmented into utterances; for those included in the same interactional turn we considered (following CHAT manual; MacWhinney, 2020) the C-unit, a main clause with associated dependent clauses. However, as this criterion is not always enough to segment the utterances in natural speech we additionally followed Bernstein Ratner and Brundage's (Reference Bernstein Ratner and Brundage2015) rule which maintains that two of the following three criteria should be met: the presence of a pause longer than two seconds, the intonation and syntactic completion.

We followed the prosodic patterns described for Spanish (Alarcos Llorach, Reference Alarcos Llorach1994) and considered whether the final portion of the unit was rising, falling or suspended in order to delimit questions, exclamations or declaratives.

To guarantee transcription reliability, research assistants and doctoral students underwent a thorough training on the transcription and utterance segmentation protocols under the supervision of a senior researcher. The trainees practiced transcribing trial samples and, once these samples matched verified master files, they started to transcribe the samples included in the study. A senior researcher rechecked for word orthographic accuracy utterance segmentation and addressee coding (see below). Whenever concerns on the less intelligible fragments arose, a further researcher was consulted.

Coding and analyses

Addressee coding

Utterances from all the participants except the target child were coded as CDS or overheard speech. The latter included adult to adult utterances, adult to non-target child(ren) utterances and, also, other child speech, either directed to an adult or to a non-target child present in the situation. For the present analysis on variation sets only CDS was considered.

Lexical measures

CLAN's MOR tool (MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney2000) was used to analyze the morphologic composition of the utterances in the sample and to identify nouns, verbs and adjectives. We employed the Argentinian version of MOR.

Automatic extraction of variation sets

The first studies that analysed variation sets in CDS employed manual extraction (Küntay & Slobin, Reference Küntay, Slobin, Slobin, Gerhartd, Kyratzis and Guo1996, 2002; Waterfall, Reference Waterfall2006). However, the intense work that this method demands on big corpus has led to the development of tools for automatic extraction (Brodsky et al., Reference Brodsky and Waterfall2007; Waterfall et al., Reference Waterfall, Sandbank, Onnis and Edelman2010; Wirén et al., Reference Wirén, Nilsson Björkenstam, Grigonytė and Cortes2016). The first one, developed by Brodsky, Waterfall and Edelman (Reference Brodsky and Waterfall2007), scans the corpus, and opens a variation set record when a word (not included in a list of highly frequent words) is repeated by the same speaker on the working set queue. The program compares utterances, considered as strings, and establishes a grade of dissimilarity between them according to Levenshtein (edit) distance. This distance is defined as how many edit operations are necessary to transform one utterance into another. On the other hand, Wirén et al. (Reference Wirén, Nilsson Björkenstam, Grigonytė and Cortes2016)'s algorithm accepts exact verbal repetitions as part of variation sets. They justified this inclusion based on the observation that utterances can be composed of the same lexical items but may show variation in prosodic as well as in the non-verbal cues accompanying them. Their algorithm also allows up to two intervening utterances as well as interventions from the child.

Following these previous studies our working definition of variation sets considers those sequences of two or more consecutive utterances (directed to the child) that share at least one word. To identify them in the corpus we developed an automatic algorithm for variation set extraction (Garber, Reference Garber2019). Instead of comparing strings, the algorithm increases its precision by parsing MOR tiers from CLAN's CHAT files (MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney2000) and comparing noun, verb and adjective lexemes in successive utterances.

The nouns identified included common nouns and kinship terms. Proper names were excluded. Adjectives were all included. The verb category included all the main verbs, referring to physical and mental actions. Copulas and auxiliaries – for example, those that make up compound verbs – were excluded. For instance, in the case of Spanish periphrastic verbs such as tiene que comer ‘she has to eat’, está comiendo ‘she is eating’, va a comer ‘she is going to eat’, we considered the non-finite verb forms (i.e., infinitives, gerunds and participles), as they contribute the most to the meaning of the construction. In contrast, the auxiliary verb only conveys grammatical information and certain meanings that qualify the action (RAE, 1983). We also excluded the verb dale, highly repeated in everyday talk in Argentinian Spanish, whose literal translation would be ‘give her’ but which is commonly used as ‘come on’ or ‘ok’.

Following Wirén et al. (Reference Wirén, Nilsson Björkenstam, Grigonytė and Cortes2016), our working definition comprised exact repetitions and allowed intervening utterances from the child, as well as one utterance from the speaker that did not have a word in common with the sequence of variation set. We also allowed up to three utterances from another speaker not directed to the child, and one intervening utterance from another speaker directed to the child. All these decisions were taken due to the specificity of naturalistic data, where several speakers participate and overlap their speech.

Reliability

To assess the reliability of the variation sets’ automatic identification, 10% of the data was hand coded by the first author and by the algorithm. Kappa results showed strong agreement (k = 0.934, z = 20.4). The variation sets automatically extracted in the whole corpus were read by the first, second and fourth authors in order to ensure they adjusted to the definition of variation sets, if not it was discarded.

Pragmatic measures

The first, second and fourth authors hand coded the pragmatic function of the variation sets extracted by the algorithm. Each variation set was categorized following a set of categories based on previous studies (Küntay & Slobin, Reference Küntay and Slobin2002; Tal & Arnon, Reference Tal and Arnon2018b):

1. Information querying: variation sets that prompt the child to answer a question with information.

-

Mamá: ¿o querés que te lea el cuento del conejo?

-

Mamá: ¿querés el cuento del conejo?

-

Mother: or do you want me to read the rabbit's story?

-

Mother: do you want the rabbit's story?

-

2. Ideational: variation sets that serve the function of providing information.

-

Mamá: y &plaf se metió al agua el lobito.

-

Mamá: se metió al agua con todo con barquito flotador, antiparras, patas de rana, malla, todo &chirinpum.

-

Mother: and &plaf the little wolf got into the water.

-

Mother: he got into the water with everything, with a little float boat, swim goggles, frog legs, swimming suit, everything &chirinpum.

-

3. Regulatory: variation sets that call for an action on the part of the child, serving a function of a control act.

-

Mamá: vení.

-

Mamá: vení que yo te ayudo.

-

Mother: come here.

-

Mother: come here so that I'll help you.

-

4. Other: Following Tal and Arnon (Reference Tal and Arnon2018b) we also considered repetitions of routines, and songs.

-

Mamá: nos vemos.

-

Mamá: chau nos vemos.

-

Mother: see you.

-

Mother: bye see you.

-

In some cases variation sets could involve more than one communicative act: those cases were categorized considering the pragmatic function of the first utterance. The example below was categorized as ideational.

Mamá: auto tenés ahí. ¡cuántos autos!

Mamá: ¿qué pasó? ¿te gustan los autos?

Mother: car you have there, a lot of cars!

Mother: what happened? do you like cars?

To assess the reliability of the coding of the pragmatic function 10% of the variation sets were coded by the first, second and fourth authors independently. Fleiss Kappa for multiple coders showed strong interobserver reliability (0.857). Disagreements were discussed.

Activity measures

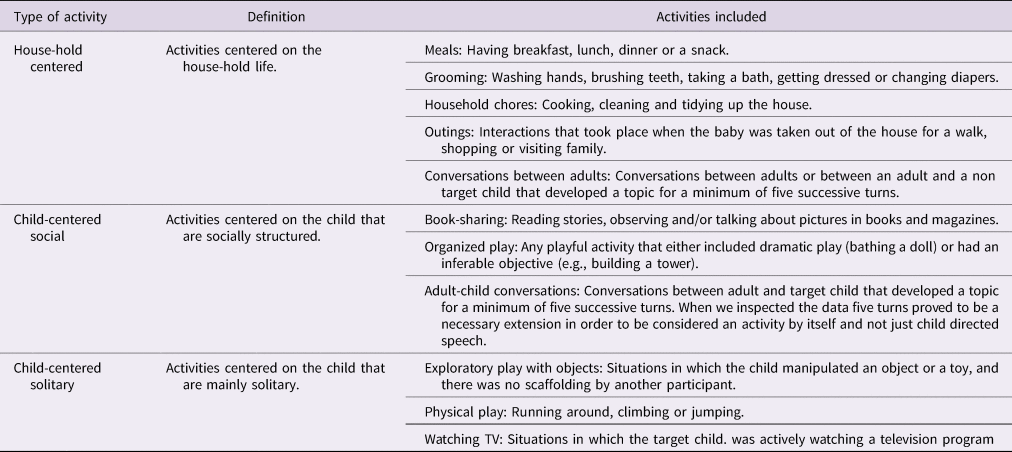

Each child-directed utterance was coded for the ongoing activity in a previous study (Rosemberg et al., Reference Rosemberg, Alam, Audisio, Ramirez, Garber and Migdalek2020). Inter-rater reliability carried out at that time showed strong inter-observer reliability (K = .95). Based on previous studies (Glas et al., Reference Glas, Rossi, Hamdi-Sultan and Batailler2018; Weisleder et al., Reference Weisleder, Mendelsohn, Villanueva, Canfield, Cates, Seery, Vasques and Robertson2019) the activities were clustered into types considering whether they were centered on the household life, or on the child, which was further classified between social and solitary activities. In table 2 we present the description of each activity type and the activities included in.

Table 2. Activity category system

Whenever two activities occurred simultaneously, the one that organized to a greater extent the participation of the child and her interlocutors was considered. When it was not possible to determine the activity that was taking place, the segment was excluded from the analysis. Considering this exclusion criteria, from the total sample of 1431 variation sets (483 from low SES and 948 from middle SES), the analyzed sample contained 1258 variation sets (402 from low SES and 856 from middle SES).

Quantitative measures of variation sets

In a previous work Stein et al. (Reference Stein, Menti and Rosemberg2021) showed SES differences in the proportion of CDS in these Argentinian households: middle SES children hear a greater proportion of CDS than low SES children. As the quantity of variation sets could be affected by these SES differences in the quantity of the CDS, we considered, in line with Tal and Arnon's study (2018a), the proportion of words and utterances (directed to the child) included in variation sets over the total amount of words and utterances in the CDS. Considering that the type of activity, our second predictor, may imply differences in the quantity of words and utterances across activities (see Table 3 in Results section), our dependent variables were: 1) the proportion of words and 2) the proportion of utterances (directed to the child) in variation sets – both were calculated over the words and utterances in the CDS of each activity type.

Table 3. Number of child directed words and utterances by activities. For each social group percentages (in brackets) were calculated over the total amount of CDS included in the analyses of type of activity

For the analyses of the pragmatic function that variation sets serve in the interaction we consider as the dependent measure the quantity of each type of pragmatic function for each child in each type of activity over the total amount of variation sets addressed to that child in that type of activity.

Data analysis

Data processing and statistical analyses were carried out in R (R Core Team, 2017). We applied mixed-effects beta regression analyses (Cribari-Neto & Zeileis, Reference Cribari-Neto and Zeileis2010) with proportions of words in variation sets, proportion of utterances in variation sets, and proportion of variation sets count for each kind of pragmatic function that included variation sets as dependent variables. The beta distribution is appropriate for studying proportions (Smithson & Verkuilen, Reference Smithson and Verkuilen2006) since it is bounded between 0 and 1, is very flexible, can accommodate skew and symmetry and allows not only to model regular location (mean) shift but also dispersion through its “precision” parameter. For interpreting this model, note that higher precision means less dispersion and vice versa. Modeling dispersion explicitly is relevant in this kind of studies because causal factors may manifest mainly through variation (and therefore heteroscedasticity) instead of location.

Results

Descriptive analyses

We first present in table 3 an overview of all the words and utterances heard by the children in each type of activity according to SES. As depicted in the table, middle SES children heard twice as much CDS than their low SES peers. When considering the amount of words and utterances in each activity type, in low SES families children heard a greater proportion of words and utterances in CDS in household centered activities, followed by child centered social and then by those in child centered solitary. Middle SES children heard almost the same amount of words and utterances directed to them in household centered and child centered social activities and less in child centered solitary activities.

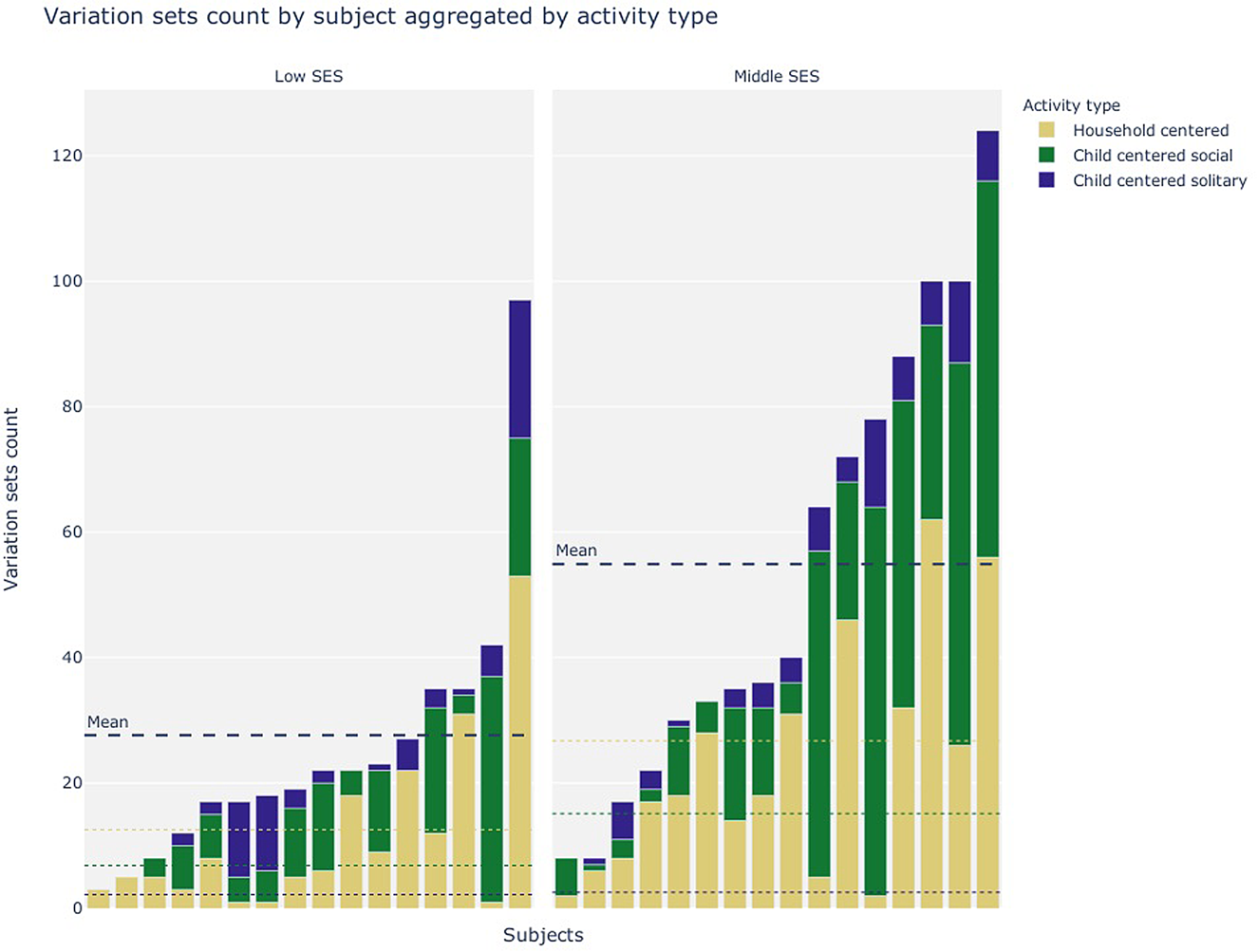

Next, in Figure 1 we present the quantity of variation sets each child heard in each type of activity, the mean of variation sets for each social group and the mean of variation sets for each social group for each type of activity. Although middle SES children heard a greater amount of variation sets, both social groups show a similar distribution across the different types of activities, such that children heard more variation sets in household centered activities, followed by child centered social and to a lesser extent in child centered solitary.

Figure 1. Quantity of variation sets each child heard for each type of activity. Dashed horizontal lines are: mean for each group (thick, black), mean for each activity for each group (thin, colored)

Regression analyses

In order to address our two research questions we fitted two sets of regression models controlling for age variability. First, we estimated the effects of SES and the type of activity (clustered in child-centered social, child-centered solitary and household-centered) on the proportion of words and utterances inside variation sets employing mixed effect beta regression analysis with target child as a random effect. Then, in order to estimate the effect of the activity type and SES on the pragmatic function of variation sets we fitted four mixed effect beta regression analyses with each type of pragmatic function as the dependent variable, considering again the child as a random effect. We first included the interaction between SES and activity type in all the models. However, as it did not show an effect, we dropped it in order to simplify the regression models. Household centered activities were used as reference levels in all the models, since the descriptive statistics shown in Figure 1 revealed a greater quantity of variation sets in this type of activity. SES is always compared with the grand mean.

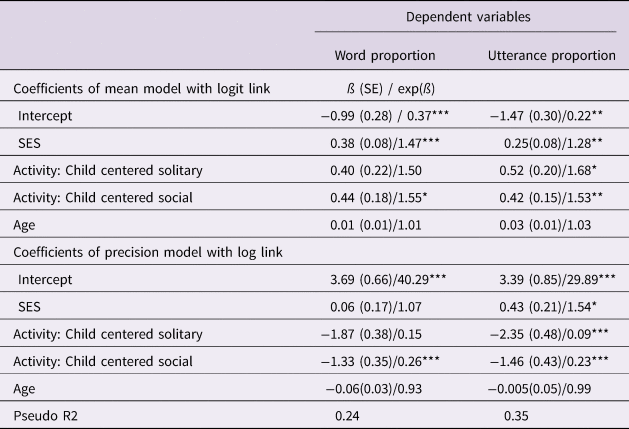

1. SES and activity type effects on the proportion of words and utterances inside variation sets

Figures 2 and 3 portray the proportion of words and utterances inside variation sets over the total amount of CDS in each social group and in each type of activity. In both groups the average child heard more than 20% of the speech addressed to them in variation sets. Also, it is worth noting that the groups share the same pattern of distribution between the activities: a greater proportion of words and utterances in variation sets in child centered social, followed by child centered solitary and finally in household centered. This indicates why the interaction between SES and activity type had no effect on the proportions of variation sets. Both words and utterances proportions were significantly higher in the middle SES group (see Table 4). Activity was also a significant predictor, such that the probability of children hearing a greater proportion of words increases in child centered social activities, and in both child centered social and solitary when the proportion of utterances is considered, compared with household centered activities, as shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2. Mean proportion of words in variation sets over the total amount of words in CDS in each type of activity aggregated by SES and activity type

Figure 3. Mean proportion of utterances in variation sets over the total amount of utterances in CDS in each type of activity aggregated by SES and activity type

Table 4. Mixed effect beta regression models predicting word and utterance proportion inside variation sets

* The level of significance is cued as follows: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001

The precision model revealed an effect of SES in the variability of the proportion of utterances: dispersion was lower in middle SES. It also showed a strong effect of the activity type: variability was much lower in household centered activities compared with child centered ones (especially in solitary). Only the activity had a significant effect on the proportion of words inside variation sets, such that precision was higher in household centered activities.

2. The pragmatic function of variation sets explained by SES and activity type

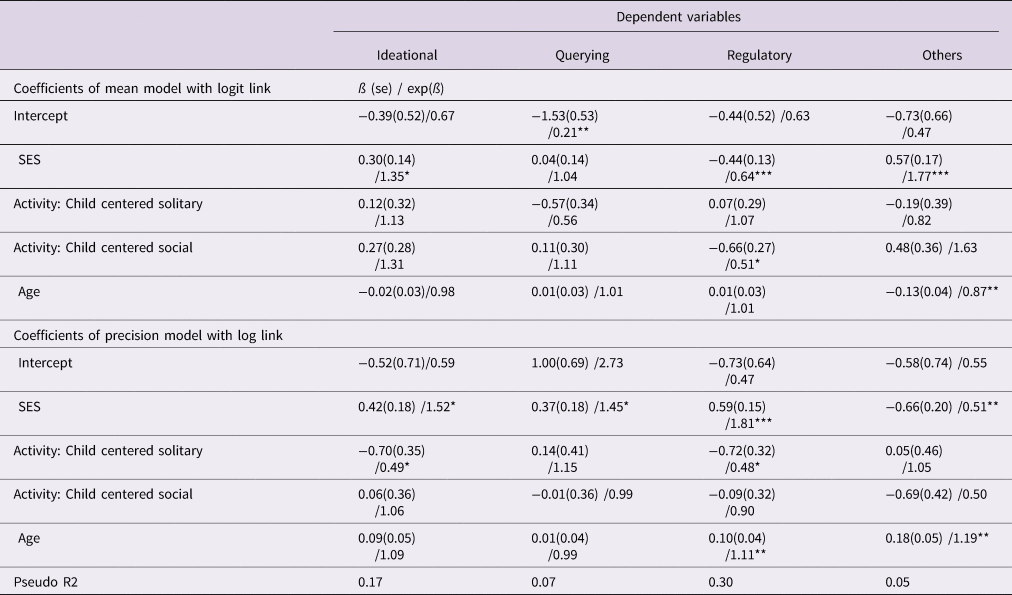

Figure 4 shows differences on the proportion of variation sets addressed with different pragmatic functions according to SES and the type of activity. To test these effects, we fitted 4 mixed effect beta regression models for each type of pragmatic function (see Table 5). The model with the regulatory pragmatic function as a dependent variable showed the best fit (pseudo R2 = .30). The results revealed that the probability of being addressed with variation sets that serve this pragmatic function is increased in household family centered activities and decreased in child centered social activities. SES also shows a significant effect: low SES children have more chances of being addressed with these types of variation sets than middle SES children. The model with the ideational pragmatic function as the dependent variable, which also showed a good fit (pseudo R2 = .17), indicates that children from middle SES have more probability of being addressed with this type of variation sets. Neither SES nor activity type showed an effect on variation sets with a querying pragmatic function. Finally, variation sets with “other” pragmatic functions revealed that there is a significantly higher probability that the target child is addressed with variation sets that serve this type of pragmatic function in the middle SES group and also with younger children. However, the pseudo R2 is not high (R2 = .06).

Table 5. Beta regression model that considered the proportion of pragmatic functions of variation sets

The level of significance is cued as follows: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001

Figure 4. Mean proportion of variation sets count for each pragmatic function aggregated by SES and activity type. CC Sol = Child centered solitary, CC Soc = Child centered social, HH Cen = Household centered.

The precision model of the beta regression analyses yielded a significant effect of SES, such that while variation sets with ideational, querying and regulatory pragmatic functions show a greater variability in low SES than in the middle SES group, the variability in “other” function was higher in middle SES than in the low SES group. Activity type had an effect on ideational and regulatory variability such that child centered solitary activities revealed higher variability on variation sets with a regulatory and ideational function. Finally, age showed an effect on variation sets with a regulatory function: variability was higher with younger children.

Discussion

This study adopted a naturalistic perspective to examine the impact of SES and the type of activity on the use of variation sets in the speech directed to Argentinian Spanish learners in their household environment. We analyzed the proportion of words and utterances in variation sets included in child directed speech and the pragmatic function they served in interaction. We examined whether previously reported effects of SES on variation sets in quasi-experimental settings (Tal & Arnon, Reference Tal and Arnon2018a, Reference Tal and Arnon2018b) were also found in a naturalistic sample collected in another language and socio-cultural environment. Our naturalistic study ensures a better understanding not only of what children hear in their natural environment, but also of the impact of the activities in the proportion of words and utterances and in the pragmatic function of the variation sets adults and older children direct to the young child, a topic which was not addressed before.

Coincidently with previous research in other languages (Küntay & Slobin, Reference Küntay, Slobin, Slobin, Gerhartd, Kyratzis and Guo1996, Reference Küntay and Slobin2002; Waterfall, Reference Waterfall2006; Wirén et al., Reference Wirén, Nilsson Björkenstam, Grigonytė and Cortes2016) our results showed that in the whole sample studied variation sets are frequently employed when addressing younger children. Nonetheless, as has been well documented regarding other features of language input (Fernald et al., Reference Fernald, Kariger, Hidrobo and Gertler2012; Hart & Risley, Reference Hart and Risley1995; Hoff, Reference Hoff2013; Rowe, Reference Rowe2008, Reference Rowe2012), the regression analysis identified SES significant differences: middle SES interlocutors employed a greater proportion of words and utterances in variation sets than low SES interlocutors. This finding mirrors Tal and Arnon's (Reference Tal and Arnon2018a) results in brief experimental and quasi-experimental dyadic play interactions.

Several naturalistic investigations (Rosemberg et al., Reference Rosemberg, Alam, Audisio, Ramirez, Garber and Migdalek2020; Tamis-LeMonda et al., Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Custode, Kuchirko, Escobar and Lo2018) have shed light on the impact of everyday activities on children's linguistic experiences; but none of them have analyzed whether the type of the activity impacts variation sets in CDS. Our descriptive results evince that the total amount of variation sets differs depending on the ongoing activity, such that children hear more variation sets in household activities, followed by child centered social and finally in child centered solitary. Interestingly, when considering the proportion of words and utterances in variation sets in relation to the amount of words and utterances in the CDS of each type of activity, the probability that a child hears a sequence of variation sets is increased in child centered social activities, followed by solitary activities and to a lesser extent in household centered activities. The difference between these two measures – the quantity of variation sets and the proportion of words and utterances included in variation sets – in child centered solitary activities may be explained by the fact that this type of activity has a lesser amount of CDS than the other activity types (see Table 3). On the other hand, the total amount of CDS in household centered and child centered social activities was very similar. It is probable that the greater proportion of words and utterances in variation sets in child social centered activities than in household centered is due to the fact that variation sets in child centered social activities are longer. Indeed in child centered social activities the child and their interlocutors attend to the same toy, book, drawing or conversation topic. In such contexts of joint attention the adult may resort to sequences in which the same lexical item is included in several re-phrased utterances that constitute a turn of interaction, in order to reach mutual comprehension and capture and maintain children's attention.

It is worth noting that the quantity of variation sets and the proportion of words and utterances in variation sets follows the same pattern of distribution between the activities in both social groups, which would explain the lack of interaction between SES and the type of activity. This finding draws attention in the framework of previous studies which have pointed out differences in socioeconomic contexts that could impact on the way activities are developed in each social group (Psaki et al., Reference Psaki, Seidman, Miller, Gottlieb, Bhutta, Ahmed, Ahmed, Bessong, John, Kang, Kosek, Lima, Shrestha, Svensen and Checkley2014; Vernon-Feagans et al., Reference Vernon-Feagans, Garrett-Peters, Willoughby and Mills-Koonce2012; Sperry et al., Reference Sperry, Sperry and Miller2019), and even more in relation with a study done with the same corpora that found an interaction between activity type and SES in the pragmatic function oriented to entities (Rosemberg et al., Reference Rosemberg, Alam, Audisio, Ramirez, Garber and Migdalek2020). This difference highlights the importance of considering different aspects of CDS in order to understand language environments, given that not all of them behave in the same way.

We also asked what effects SES and the ongoing activity may have on the pragmatic function served by variation sets in the interaction. Our findings are consistent with previous literature on the impact of SES. As shown by Tal and Arnon (Reference Tal and Arnon2018b), variation sets with an ideational function were more frequent in middle SES, and no SES differences were found in variation sets that query information. Although Tal and Arnon (Reference Tal and Arnon2018b) found differences in the proportion of variation sets used to regulate children's behaviour, the differences were not statistically significant. Our study did find a statistically higher probability that low SES children were addressed with variation sets that served a regulatory pragmatic function. The difference between both studies may be explained by the fact that our corpus is made up of long natural audio recordings at the child's home without the presence of the observer, therefore reflecting what the children of low SES actually hear at home. Indeed, Sperry et al. (Reference Sperry, Sperry and Miller2019) has shown that in these households there are usually a greater number of participants and fewer objects (Bradley & Corwin, Reference Bradley and Corwin2002) that can attract children's attention than in quasi-experimental play situations, where the child's attention is focused on the toys and where there are no other people that may distract the child. Therefore, low SES caregivers may probably need to use more directives to capture child's attention. In this respect our findings support previous literature showing a higher amount of commands in the input directed to children from low SES (Hoff, Reference Hoff2006; Kuchirko et al., Reference Kuchirko, Schatz, Fletcher and Tamis-LeMonda2019; Ramirez et al., Reference Ramirez, Migdalek, Stein, Cristia and Rosemberg2016; Rowe, Reference Rowe2008).

Activity type only showed an effect on variation sets with a regulatory function: this type of repeated sequence was more frequent in household centered activities, probably because in these contexts the adult and the child are focused on actions that the adult expects the child to do, such as eating, getting dressed, staying still while changing the diaper. Variation sets used with a regulatory function may help this purpose (Küntay & Slobin, Reference Küntay and Slobin2002)

The beta regression analysis employed in this study revealed significant intra group variance in low SES both in the proportion of variation sets and in the pragmatic functions. Within variability in socioeconomic groups was previously observed not only by Tal and Arnon (Reference Tal and Arnon2018a) in relation to variation sets, but also by research focusing on quantitative and qualitative characteristics of input at a global level (Stein, Menti & Rosemberg, Reference Stein, Menti and Rosemberg2021; Sperry et al., Reference Sperry, Sperry and Miller2019; Weisleder & Fernald, Reference Weisleder and Fernald2013). Intra group variability reveals that SES groups, and specially low SES, are not homogeneous, and point out the need to delve further into other socio-demographic and cultural characteristics of each social group.

In line with Tamis Le-Monda et al. (Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Custode, Kuchirko, Escobar and Lo2018), Weisleder et al. (Reference Weisleder, Mendelsohn, Villanueva, Canfield, Cates, Seery, Vasques and Robertson2019) and Rosemberg et al. (Reference Rosemberg, Alam, Audisio, Ramirez, Garber and Migdalek2020)'s findings, the precision model indicated significant variability in the impact of child centered activities (specially in solitary ones), in contrast to household centered activities, on the proportion of words and utterances in variation sets in CDS and in the pragmatic function they serve in interaction. The greater precision regarding the impact of household activities may be due to the fact that urban families, both from low and middle SES, may not differ greatly in the way they structure language directed to the child in household chores, grooming and meals while child centered activities that depend more on objects, such as books and toys, may vary more across social groups and individual families. On the other hand, it is worth noting that in our sample household activities had greater quantities of variation sets than the other types of activities, and this may also explain its precision, particularly in relation to child centered solitary, which was in fact the activity type that showed greater variability.

There are some limitations to this study. First, although the use of automatic extraction of variation sets allowed us to analyze a large corpora (64 hours), this type of methodology always leaves out aspects that only a human coder can identify, such as semantic re-phrasals that resort to synonyms.

Second, albeit the use of naturalistic recordings at home settings preserves the ecology of data, it has some limitations. This procedure leaves out participants’ gestures and actions that can help understand the ongoing activity. Nevertheless, the use of video recordings that provide such visual information would have also involved drawbacks. Handheld cameras demand the presence of an observer, making the situation less natural, and even obscuring children's everyday language experience by magnifying input measures (Bergelson et al., Reference Bergelson, Amatuni, Dailey, Koorathota and Tor2018).

Participants were self-selected, so conclusive generalizations to the entire population should be avoided. Additionally, it is necessary to take into account that the socio-economic status working definition varies across countries and communities: hence, our findings on the use of variation sets in CDS could only be applied to the understanding of children's linguistic experience in populations similar in housing density, and caregivers’ education. Nonetheless, this constraint is inherent to the study of children's linguistic experiences in diverse communities; in this respect, generalization may be only an aspiration not fully achieved in research aimed at the understanding of socio-cultural variations in the use of language in CDS.

To conclude, the results of this study highlight the need to attend to how language is structured in the CDS of natural at home everyday interactions. Our findings revealed that both SES and the type of activity impact on how interlocutors organize the information to young children at the local level of interactions. The partial self-repetitions of lexical items in successive utterances that constitute variation sets probably influence language acquisition; capturing children's attention on particular lexical items, and showing the syntactical and morphological features of the particular language in the verbal interaction in which the child is naturally involved. Longitudinal analysis that considers children's outcome will shed light on the impact variation sets may have on language development.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none