Hostility toward refugees is a global phenomenon (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner2016; Wike et al., Reference Wike, Stokes and Simmons2016; Cowling et al., Reference Cowling, Anderson and Ferguson2019). In the United States, the American public has often expressed exclusionary attitudes toward refugees, even during humanitarian crises such as World War II or the more recent Syrian and Afghan conflicts (Pew Research Center, 2015; Hartig, Reference Hartig2018). These attitudes are frequently reflected in restrictive policies that seek to limit refugee admissions (Gibney, Reference Gibney2003; Hinnfors et al., Reference Hinnfors, Spehar and Bucken-Knapp2012). With forced displacement currently at historic highs (UNHCR, 2023), and conflict between refugee and host communities contributing to instability in a number of countries (Salehyan and Gleditsch, Reference Salehyan and Gleditsch2006; Fisk, Reference Fisk2018; Rüegger, Reference Rüegger2019, though see Lehmann and Masterson, Reference Lehmann and Masterson2020; Shaver and Zhou, Reference Shaver and Zhou2021), researchers are seeking to understand why people oppose refugees and to identify strategies for strengthening acceptance of this vulnerable group (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner2016; Dinas et al., Reference Dinas, Matakos, Xefteris and Hangartner2017; Adida et al., Reference Adida, Lo and Platas2018; Williamson et al., Reference Williamson, Adida, Lo, Platas, Prather and Werfel2021; Facchini et al., Reference Facchini, Margalit and Nakata2022).

To date, this research has placed particular emphasis on two inclusionary strategies. The first involves the provision of factual information that aims to correct misperceptions about migrants. Existing research suggests that people often overestimate how much refugees or immigrants differ culturally from the host community, or the extent to which they shape negative social and economic outcomes such as crime and unemployment (Alesina and Stantcheva, Reference Alesina and Stantcheva2020; Wu, Reference Wu2022; Lutz and Bitschnau, Reference Lutz and Bitschnau2023). These misperceptions may contribute to hostile attitudes by increasing perceived threats to host communities (Sides and Citrin, Reference Sides and Citrin2007).

The second strategy leverages emotions through perspective-getting exercises in which respondents reflect on the experiences of an outgroup member. Perspective-getting is designed to expose members of the ingroup to the experiences and feelings of an individual from the outgroup, and research has shown that such exercises can have robust and significant prejudice-reducing effects (Kalla and Broockman, Reference Kalla and Broockman2023).Footnote 1

While both approaches show promise in strengthening inclusion—by which we mean beliefs, attitudes, policy positions, and behaviors indicative of a more welcoming inclination toward refugeesFootnote 2 —they also have limitations. Studies that seek to reduce hostility toward migrants by providing information meant to correct misperceptions yield contradictory results, with some producing more inclusive views and policy preferences (Blinder and Schaffner, Reference Blinder and Schaffner2019; Facchini et al., Reference Facchini, Margalit and Nakata2022; Thorson and Abdelaaty, Reference Thorson and Abdelaaty2022), and others producing null or very small effects (Hopkins et al., Reference Hopkins, Sides and Citrin2019; Jørgensen and Osmundsen, Reference Jørgensen and Osmundsen2022; Huang, Reference Huang2023). These limited effects reflect a broader literature on political misperceptions, which indicates that providing accurate information on a variety of topics typically produces only small reductions in misperceptions and even less updating of political attitudes; it may also occasionally backfire (Chong and Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007; Nyhan and Reifler, Reference Nyhan and Reifler2010; Bursztyn and Yang, Reference Bursztyn and Yang2021). Meanwhile, studies relying on perspective-getting produce more reliably positive effects on inclusive attitudes and behaviors (Kalla and Broockman, Reference Kalla and Broockman2023), but scholars have questioned their scope. Indeed, some have argued that such empathy-based interventions may reproduce or even exacerbate ingroup biases (Bloom, Reference Bloom2016; Simas et al., Reference Simas, Clifford and Kirkland2019), making them effective only on groups to whom participants already feel close.

We move research on inclusion forward in two ways. First, our theoretical framework identifies the factors that can enhance or limit the effectiveness of factual information and perspective-getting as inclusion-promoting strategies. Providing information to correct misperceptions may not work because the information provided may not be new, it may not be salient to exclusionary attitudes, or it may be rejected by individuals motivated to believe information that is more consistent with their priors. Perspective-getting may have limited effects because such interventions rely heavily on activating empathy, which may work only on groups with whom we already feel kinship. We identify the criteria most likely to shape the effectiveness of each strategy, and then develop an argument for why combining the two might address each individual strategy's limitations: perspective-getting may attenuate an individual's motivation to resist new information, while factual information may weaken misperceptions that make outgroups seem more socially distant, which would otherwise limit the effectiveness of empathy-based interventions.

Our research design involves a sequence of three studies on more than 15,000 individuals over the course of three years. We use the first two studies as intervention-builders: they help us determine what are the most common misperceptions about refugees, and whether perspective-getting interventions are more or less effective depending on the identity of the refugee. Reflecting our approach to inclusion, we examine whether respondents update beliefs that may fuel negative stereotypes about threats from refugees, express warm feelings toward refugees, support or oppose a policy of increasing the refugee cap (the maximum number of refugees admitted for resettlement each year), and engage in political behavior to support refugees. The final study provides a comprehensive test of our individual and combined interventions on each of these four outcomes.

Our results are threefold. First, we find that both information and perspective-getting interventions affect the outcomes under study, but not uniformly. While our information treatment led to factual updating, it had no effect on warmth toward refugees or pro-refugee behavior. Moreover, we find suggestive evidence of a backfire effect: information designed to reduce misperceptions also reduced support for pro-refugee policy. By contrast, perspective-getting led to an increase in warmth toward refugees, support for raising the cap on refugees admitted to the United States, and the likelihood of writing a letter in support of pro-refugee policy, but did not reduce the extent of misperceptions.

Second, we find that the combined information and perspective-getting treatment affected all outcomes, pushing respondents toward greater inclusion. Additionally, bundling the two strategies reduced the backfire effect of information on support for pro-refugee policy. However, we find no evidence of an interactive effect in that neither intervention enhanced the effectiveness of the other.

Our paper joins a growing literature investigating the effectiveness of providing information to counter common misperceptions about outgroups, and perspective-getting narratives on outgroup inclusion, while clarifying the contours of the impact of these interventions. A combined intervention successfully shifts all four inclusionary outcomes, revealing that these two strategies can work as complements to promote outgroup inclusion. We also show the limits of these individual interventions. Interventions that provide information to counter misperceptions lead to factual updating, but without shifting warmth, policy preferences, or behavior in an inclusionary direction. Perspective-getting shifts individuals’ warmth, policy preferences, and behavior toward outgroups but has limited effects on accurate updating of misperceptions. While neither intervention amplifies the effect of the other, we provide suggestive evidence that embedding information meant to correct misperceptions in a perspective-getting narrative may act as a protective shield against possible backfire effects of information interventions.

1. Information, emotion, and prejudice reduction

Social scientists seeking to understand what shapes public attitudes and behaviors toward outgroups, and refugees in particular, have placed particular emphasis on two strands of inquiry: the first focuses on the role that information—and misperceptions—play in sustaining or alleviating exclusionary attitudes, and the second examines the role of narratives or empathy-inducing exercises. Below, we identify the contributions and limitations of each approach, and develop a blueprint of strategies that increase refugee inclusion.

1.1 Providing information to correct misperceptions

Do individuals exclude others because of misperceptions they hold about the social group(s) to which they belong? Misperceptions about social outgroups are common. Americans overestimate how many Black Americans receive benefits from welfare (Delaney and Edwards-Levy, Reference Delaney and Edwards-Levy2018), overestimate the percent of crimes committed by Black and Hispanic Americans (Ghandnoosh, Reference Ghandnoosh2014), and incorrectly think that Muslim-Americans are more likely to support violence against civilians (Williamson, Reference Williamson2020). Such misperceptions are not innocuous: they are usually correlated with negative attitudes toward the outgroup in question (Fisk, Reference Fisk2018; Abrajano and Lajevardi, Reference Abrajano and Lajevardi2021).

In response to such misperceptions, refugee advocates attempt to provide corrective information intended to mitigate perceptions of refugees as threatening to national security, cultural norms, or the economy.Footnote 3 However the efficacy of these types of campaigns remains an open question (Adida et al., Reference Adida, Lo, Prather and Williamson2022). Studies that have tried to correct specific pieces of information about outgroups have generated mixed results. In two experimental studies providing statistical facts about the size and characteristics of the immigrant population in the United States, Grigorieff et al. (Reference Grigorieff, Roth and Ubfal2016) find that individuals do update their beliefs, as well as their policy preferences, accordingly. On the other hand, in seven separate survey experiments conducted over more than a decade, Hopkins et al. (Reference Hopkins, Sides and Citrin2019) find largely null effects of providing information on attitudes toward immigrants. Adida et al. (Reference Adida, Lo and Platas2018) also find that providing information about the relatively small number of Syrian refugees admitted to the United States compared to peer countries did not change sentiments or behaviors toward this group. Likewise, Huang (Reference Huang2023) shows that information about the ethnic backgrounds of immigrants to the United States does not shift policy attitudes or perceptions of immigrants’ impact. Even more concerning, some studies have found that providing information meant to correct misperceptions may actually generate backlash (Nyhan and Reifler, Reference Nyhan and Reifler2010).

There are several reasons why individuals may not update their factual beliefs or attitudes in response to information. First, the information may not be new. Second, even if information does lead to the updating of factual beliefs, it may not necessarily lead to changes in attitudes or policy preferences (Bursztyn and Yang, Reference Bursztyn and Yang2021; Nyhan, Reference Nyhan2021). One reason for this disconnect is that the factual beliefs being corrected may not be relevant to attitude and policy preference formation. For example, if the size of an outgroup locally is more important for attitude formation than the size of the outgroup nationally, providing information on the latter is unlikely to affect attitudes toward the outgroup.

Third, even if information addresses beliefs that are relevant to preference formation, an individual may resist updating their attitudes in response to the corrected information. This resistance may occur because the individual is motivated to interpret the information in a way that aligns with their existing sentiments, policy attitudes, and political behaviors (Bolsen et al., Reference Bolsen, Druckman and Cook2014; Lind et al., Reference Lind, Arvid, Daniel and Gustav2022), or because the individual holds strong priors based on previously consumed information, which causes them to update less (Little, Reference Little2022).

Finally, causality may run in the opposite direction. An individual who holds negative attitudes toward Muslims may justify this with the belief that Muslims engage in terrorist activity. Changing this belief with corrective information will not affect the individual's attitudes, because this belief is a product not a predictor of the exclusionary attitude (Nyhan, Reference Nyhan2021).

Acknowledging the many ways in which information can fail to change beliefs and attitudes, in this study we select a piece of information we show to be both new and relevant to preference formation: Americans tend to underestimate the amount of security vetting refugees undergo, and beliefs about vetting correlate with policy preferences. Thus, this piece of information is a “best case” scenario for testing the effect of information on updating and attitude change.

1.2 Perspective-getting to generate empathy

A second strategy for reducing exclusion focuses on emotion, aiming to promote empathy for outgroups through perspective-getting exercises. These exercises may reduce prejudice by activating empathy, including concern or sympathy directed toward the outgroup, as well as feeling what it would be like to go through the outgroup's experiences. These exercises may also increase accurate beliefs about outgroups if the cognitive efforts they require lower stereotypical thinking. Finally, these exercises may reduce exclusionary attitudes and behaviors by lowering the perceived social distance with the outgroup and shifting attributional thinking (Kalla and Broockman, Reference Kalla and Broockman2023). Perspective-getting campaigns include UNHCR's “See refugees through new eyes,” a video campaign in Bulgaria that shows the experience of a refugee trying to settle in a new countryFootnote 4 and Clouds over Sidra, which is a virtual reality tour of a Syrian refugee camp in Jordan.Footnote 5

Substantial evidence in the social sciences indicates that perspective-getting can be effective at reducing exclusionary attitudes, while also shifting policy preferences and behaviors in a more inclusive direction (Broockman and Kalla, Reference Broockman and Kalla2016; Adida et al., Reference Adida, Lo and Platas2018; Kalla and Broockman, Reference Kalla and Broockman2023; Williamson et al., Reference Williamson, Adida, Lo, Platas, Prather and Werfel2021). But others have also argued that empathy-based interventions may exacerbate polarization (Simas et al., Reference Simas, Clifford and Kirkland2019) and ingroup bias (Bloom, Reference Bloom2016). This work suggests that a limitation to empathy-based interventions is that empathy is easier to experience for groups or individuals with whom we already feel kinship. Simas et al. (Reference Simas, Clifford and Kirkland2019), for example, find that individuals who score higher on an index of empathic concern more strongly favor their own political party relative to the other political party. Similarly, Bloom (Reference Bloom2016) argues that it is not possible to empathize with everyone. Because empathy takes cognitive and emotional effort (Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Hutcherson, Ferguson, Scheffer, Hadjiandreou and Inzlicht2019), it is natural for individuals to favor empathizing with some over others. The implication of this empathy bias (Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Law and Gaesser2021) is that empathy-based interventions risk reproducing the biases that divide us.

In our study, we build a perspective-getting exercise with a “hard-test” narrative about a Muslim refugee from Somalia. By doing so, we explicitly test whether empathy-based interventions work when the protagonist is more likely to be perceived as culturally distant by many Americans.

1.3 Interactive and additive effects

The above sections identify potential weaknesses of each separate intervention. In this section, we consider theoretical reasons for combining the two. Prior studies have not considered combining perspective-getting exercises and factual information meant to counter misperceptions in the same intervention. Yet, for our subject matter, we can easily embed information about the refugee vetting process within a perspective-getting exercise that delivers a human-centered narrative about a refugee. There are a number of reasons why pairing the two strategies will help us understand the ways and extent to which each strategy works.

First, we theorize that combining the two into a single intervention may lead to interactive effects. Perspective-getting can improve the uptake of new information through two possible mechanisms, one emotional and the other cognitive. Perspective-getting exercises have been tied to directly promoting open-mindedness in educational contexts (Southworth, Reference Southworth2021). They may further spur emotions such as empathy that open one up to integrating new information or allow for softening of previously held beliefs (Morisi and Wagner, Reference Morisi and Wagner2020). When individuals encounter information that conflicts with their priors or their attitudes about an outgroup, they may experience an emotional reaction that leads them to resist incorporating that information. By creating more openness toward new information, empathy generated by perspective-getting exercises may counteract this typical emotional response, making it more likely that an individual responds to the information by updating their beliefs.

Previous research also shows that individuals who engage in complex cognitive tasks are less likely to rely on out-group stereotyping (Galinsky and Moskowitz, Reference Galinsky and Moskowitz2000; Todd et al., Reference Todd, Galinsky and Bodenhausen2012). When information is paired with perspective-getting, individuals are set in a cognitive pathway that carefully considers the perspective they are receiving. Information presented in this context may be more deeply considered and therefore more likely to lead to updating.

At the same time, information meant to correct misperceptions may improve the effect of perspective-getting by alleviating empathy bias. Scholars across the social sciences have warned against empathy as a foundation for morality (Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Law and Gaesser2021) or policymaking (Bloom, Reference Bloom2016), because—they argue—we tend to feel empathy more readily for people with whom we already feel kinship. Yet we also know that identity groups are social constructs (Laitin, Reference Laitin1986), and that cultural proximity can be fluid and endogenous (Adida and Robinson, Reference Adida and Robinson2023). By embedding information about the lack of security threat posed by refugees into our perspective-getting exercise (by virtue of the extensive vetting process they must undergo), we can test whether perspective-getting becomes more effective when combined with information that reduces an important perceived difference between refugees and Americans.Footnote 6

Second, we argue that combining the two interventions could result in an additive rather than, or in addition to, an interactive effect. The argument above suggests ways in which combining the treatments may augment the effectiveness of both of them: perspective-getting exercises might open people up to consider new information, while new information may decrease perceived cultural distance and make empathy easier to generate through perspective-getting exercises. It is also possible that each intervention works independently on each outcome, and when combined they produce two separate effects for participants. Indeed, an emotional reaction generated by a perspective-getting exercise and new information on the vetting process provide two unique experiences to the participant, potentially generating two treatment effects in one.

1.4 Observable implications

From this argument follow several observable implications about the effectiveness of each individual strategy relative to a control, but also about the effectiveness of the combined treatment relative to each individual treatment. Below, we present our hypotheses.Footnote 7

We build on past research by designing a study that uses a comprehensive set of outcomes related to inclusion: belief updating, warmth, policy preference, and behavior. Existing studies tend to focus on only one or a subset of outcomes. Testing for effects on a richer set of outcomes allows us to identify which outcome each strategy moves independently, and whether a combined intervention is more likely to shape certain inclusionary outcomes over others. We expect that the combination of information and perspective-getting will affect both belief updating and inclusionary attitudes, policy preferences, and behaviors. However, whether these effects work separately or jointly is not clear ex ante.

Participants in our experiment are divided into four groups: control, information alone (Info), perspective-getting alone (PG), and information embedded in a perspective-getting exercise (PG-Info). We expect a minimal effect of information on inclusionary outcomes related to warmth, policy preferences, or behavior. Providing new and salient information should result in belief updating, but we expect that individuals’ motivated resistance to information challenging their priors will limit the effect of information on other measures of inclusion.

H1: (Info effect) Information increases belief updating relative to the control, but it does not affect any other outcome (warmth, policy preference, behavior) relative to the control.

Second, we expect a positive effect of perspective-getting on warmth and inclusionary behavior, as predicted by the existing literature. However, while there are theoretical reasons to believe that perspective-getting might soften prejudicial beliefs, here we do not expect that perspective-getting on its own will change belief updating (since we provide no actual information in that intervention) or policy preferences, the latter of which may be sticky and particularly difficult to shift (e.g., Williamson et al., Reference Williamson, Adida, Lo, Platas, Prather and Werfel2021).

H2: (PG effect) Perspective-getting (PG) increases warmth and inclusionary behavior relative to the control, but it does not affect belief updating or policy preference relative to the control.

Finally, we test whether the combined treatment will have greater effects on all outcomes relative to either independent treatment.

H3: (Combined effect) PG-Info increases belief updating, warmth, inclusionary policy preference, and inclusionary behavior relative to either PG or Info.

2. Research design

Our research design allows us to test the independent effects of the two inclusionary strategies outlined above, to examine whether their combination leads to additive or interactive effects, and to identify the full set of outcomes our strategies shape. To formulate our research design, we rely on two original studies: the first identifies new and salient information in the refugee vetting process and the second identifies a hard test for perspective-getting. Our empirical test then uses a survey experiment that we developed based on these initial studies to assess the effectiveness of the independent and combined interventions.

The initial surveys used to design our experiment recruited large national samples of American respondents via Lucid.Footnote 8 These samples are representative on several key demographic characteristics. The first survey which was used to design our informational intervention had a sample size of 3,840 respondents and was conducted in the fall of 2019. This survey was intended to provide a baseline measure of Americans’ knowledge about refugee populations and refugee policy in the United States. A second survey, administered on 2,011 respondents in the spring of 2021, served as a pilot in which we tested several versions of the treatment.

After designing and piloting our research design, we used a third survey to test the hypotheses. This survey had a sample size of 9,407 respondents and was implemented in the fall of 2021. It used results from the first and second survey to design an intervention intended to counter the misperceptions identified in the 2019 survey and reduce negative attitudes toward refugees through a hard test of a perspective-getting exercise.Footnote 9

2.1 Designing the information-correction intervention

The purpose of the first survey was to assess the American public's general knowledge about the country's refugee population and refugee policies, with the goal of identifying common misperceptions that could form the basis of the informational intervention. We asked respondents to provide their best guesses about the number of refugees admitted in the prior year (addressing the common trope that the country is overrun by refugees), the demographic characteristics of the refugee population, their country of origin, and their language abilities (addressing the common trope that refugees cannot assimilate culturally), whether refugees pay taxes (addressing the common trope that refugees do not contribute to society), and the extent of US government vetting of refugees as well as the frequency of refugees’ involvement in terrorist and criminal activities (addressing the increasingly common trope that refugees threaten US security).

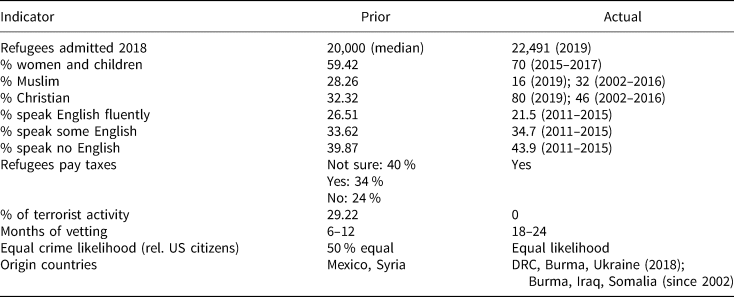

Table 1 below summarizes the average American conception about each of the above criteria (under the “Prior” column), comparing it to factual information (under the “Actual” column).Footnote 10 We find that typical misperceptions exist: the average respondent under-estimates the percentage of refugees who are women and children and over-estimates the proportion of refugees who are Muslim, for example.

Table 1. Prior beliefs and actual

Most notably, respondents in this representative sample over-estimated the security threat posed by refugees. Although the evidence overwhelmingly confirms that refugees have committed close to 0 percent of domestic terrorist activity, our sample on average reported that refugees have committed one-third of domestic terrorist activity in the US. Relatedly, Americans underestimate the amount of time dedicated to vetting refugees: the process typically takes 18–24 months, yet the modal respondent estimated that the process takes only 6–12 months. Sixty percent of the sample gave answers well below 18–24 months, with almost 10 percent of respondents indicating that there is no vetting process at all. This misperception appears to be specific to refugees as a terrorist threat, rather than a criminal threat: when asked if refugees are less likely than, equally likely as, or more likely than US citizens to commit serious crimes, the modal respondent (50 percent) answered correctly that refugees and US citizens are equally likely to engage in serious criminal activity (Amuedo-Dorantes et al., Reference Amuedo-Dorantes, Bansak and Pozo2018). We report these results graphically in SI, Section 5.

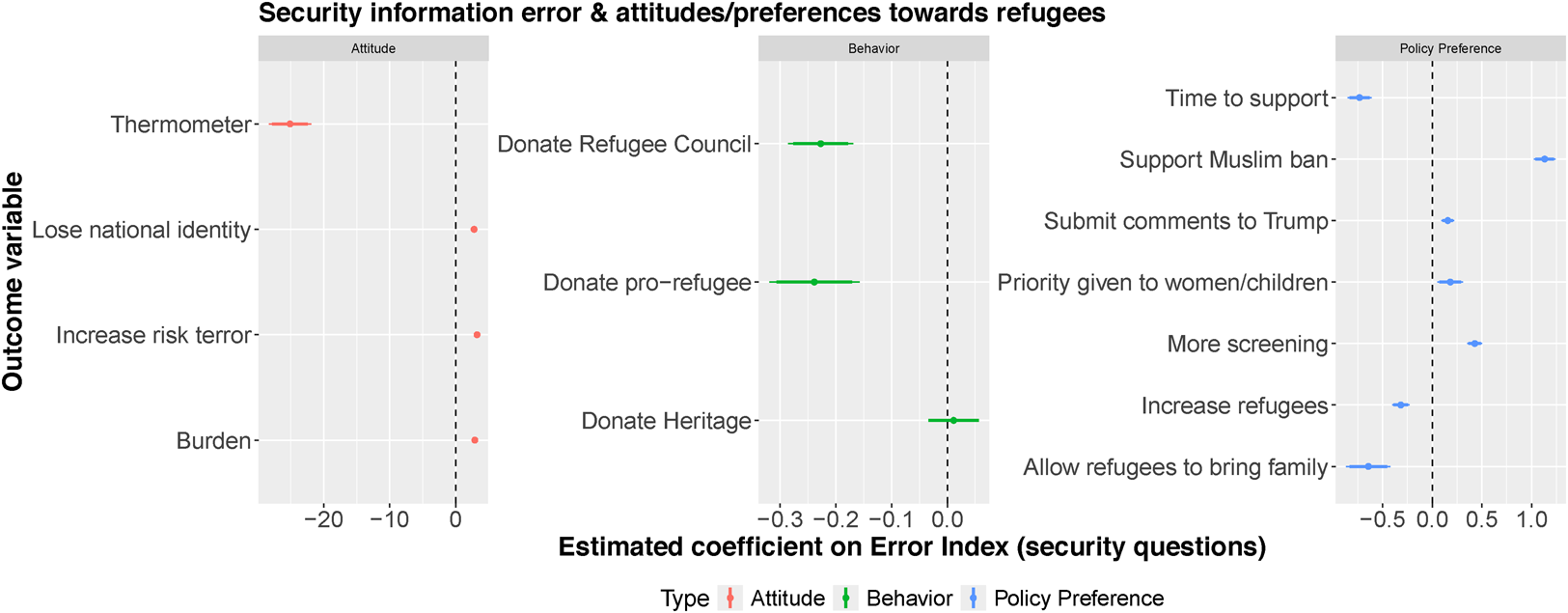

Our study also asked respondents about their feelings toward refugees, support and opposition to refugee policies, and whether they would engage in behaviors designed to support refugees. As a result, we are able to analyze whether these security-related misperceptions are significantly correlated with these outcomes. We use an “error index” as our explanatory variable. This is a (scaled) index of errors respondents have in the security threat knowledge variables (equally weighted). Here, larger values are equivalent to more error. The dependent variables are grouped into “attitudes,” “behaviors,” and “policy preferences.”Footnote 11

Figure 1 illustrates the correlation coefficient between the error index on our security threat questions and each outcome variable in a multiple regression framework. Respondents with a higher error index on security threat questions were more likely to view refugees unfavorably, more likely to hold restrictive refugee policy preferences, and more likely to exhibit behaviors associated with opposition to refugees. This relationship is stronger than any other correlation between error indices (e.g., on measures of refugees as a cultural or economic threat) and refugee exclusion.

Figure 1. Correlation between information error and attitudes/preferences toward refugees.

Notes: Each point reflects the estimated coefficient of the error index on the corresponding outcome variable in a linear regression with controls for respondent gender, race, education, party, approval for Trump, state of residence, baseline empathy, and whether the respondent has immigration history in their family's first, second, and third generations. Full regression results are reported in SI, Section 6.

2.2 Piloting interventions and outcomes

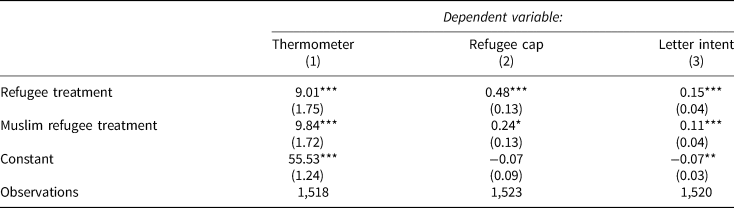

We used a second survey to develop the perspective-getting intervention. We piloted several narratives, with the goal of evaluating whether respondents reacted differently toward narratives highlighting various aspects of a refugee's identity. The core narrative in our treatments focused on a refugee who fled Somalia and ended up in the midwest region of the United States. Given the politicization of anti-Muslim sentiment toward refugees since the Syrian Civil War and then during the Trump administration, we sought to examine whether respondents reacted differently to this perspective-getting narrative when the protagonist was described as a “refugee” or a “Muslim refugee.” The Muslim refugee narrative also included an additional sentence about the refugee's difficulties explaining his religion once he arrived in the United States.Footnote 12 In Table 2, we report how these two treatments affected the three inclusionary outcomes described above.

Table 2. Effects of perspective-getting with refugee versus Muslim refugee treatments

Note: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

The results suggest that the perspective-getting treatment is less effective in moving respondents’ preferences toward the refugee cap and willingness to write a letter of support when the narrative is about a Muslim refugee than when it is about a generic refugee. The strongest effect applies to the refugee cap, where the magnitude of the Muslim refugee treatment is half that of the refugee treatment, and this difference is statistically significant at 0.10. These results suggest that the “Muslim refugee” narrative provides a harder test of perspective-getting for an intervention targeting a sample of American adults. Since we are interested in probing the limits of perspective-getting interventions, we use this harder test for our main empirical test.

2.3 Testing information-correction and perspective-getting as individual and combined interventions

Our core pre-registered empirical test builds on the studies described above to assess whether and how providing respondents with information, perspective-getting, or the combination of both shapes refugee inclusion. In this third survey, respondents were randomly assigned to a control group or one of three treatment groups. After a set of demographic questions, the control group proceeded directly to the outcome questions. The first treatment group was provided with information about the vetting process in a short paragraph citing government procedures, agencies involved, and average length of time. Respondents were also provided with a link to a US government infographic with additional information about vetting.Footnote 13

The second treatment group was provided with this same informational paragraph, but it was embedded within our hard test for perspective-getting: a narrative about Abdi, a Muslim refugee admitted to the United States. This narrative was based on real-world stories we gathered from available US newspapers, and we debriefed respondents on the fictional nature of the story at the conclusion of the survey—with links to the sources we used to construct the story.

Finally, the third treatment group read only Abdi's story, including his time spent in the refugee camp, but did not include any facts about the vetting process. To ensure that respondents were paying attention to the vignette, we asked all respondents in the treatment groups to briefly summarize how they felt about what they had just read prior to seeing the outcome questions. We report balance across the three treatment groups and control on a number of demographic variables and prior knowledge about refugee vetting in the SI.

We examine the effects of the treatment vignettes on four main outcomes. We first wanted to test whether we could successfully correct misperceptions. We therefore asked respondents how long it takes the US government to vet refugees. Second, we follow others in using a feeling thermometer to gauge negative sentiment toward refugees as people (Alrababa'h et al., Reference Alrababa'h, Dillon, Williamson, Hainmueller, Hangartner and Weinstein2020). Third, feelings of warmth toward refugees may diverge from policy preferences, as the latter may be shaped by other inputs such as partisanship (Grigorieff et al., Reference Grigorieff, Roth and Ubfal2016). To assess our respondents’ inclusionary attitudes toward refugee policy, we asked if the cap on the number of refugees admitted into the United States annually should be increased, decreased, or kept the same. Finally, to gauge if our treatments could prompt political action on behalf of refugees, we followed Adida et al. (Reference Adida, Lo and Platas2018) by asking if respondents would write a letter to the White House in support of their policy views. We analyze this variable as both a measure of intent (in the manuscript) and of actual behavior (in the SI, Section 8): results hold for both. The survey questions used to measure each of these outcomes can be found in SI, Table A-10.Footnote 14

3. Results

In this section, we present results for tests of our pre-registered hypotheses (unless otherwise stated). The four experimental groups are referred to as Info for the information only treatment, PG for the perspective-getting only treatment, PG-Info for the information embedded in the perspective-getting vignette treatment, and Control for the respondents who did not receive a vignette with information or the perspective-getting exercise.

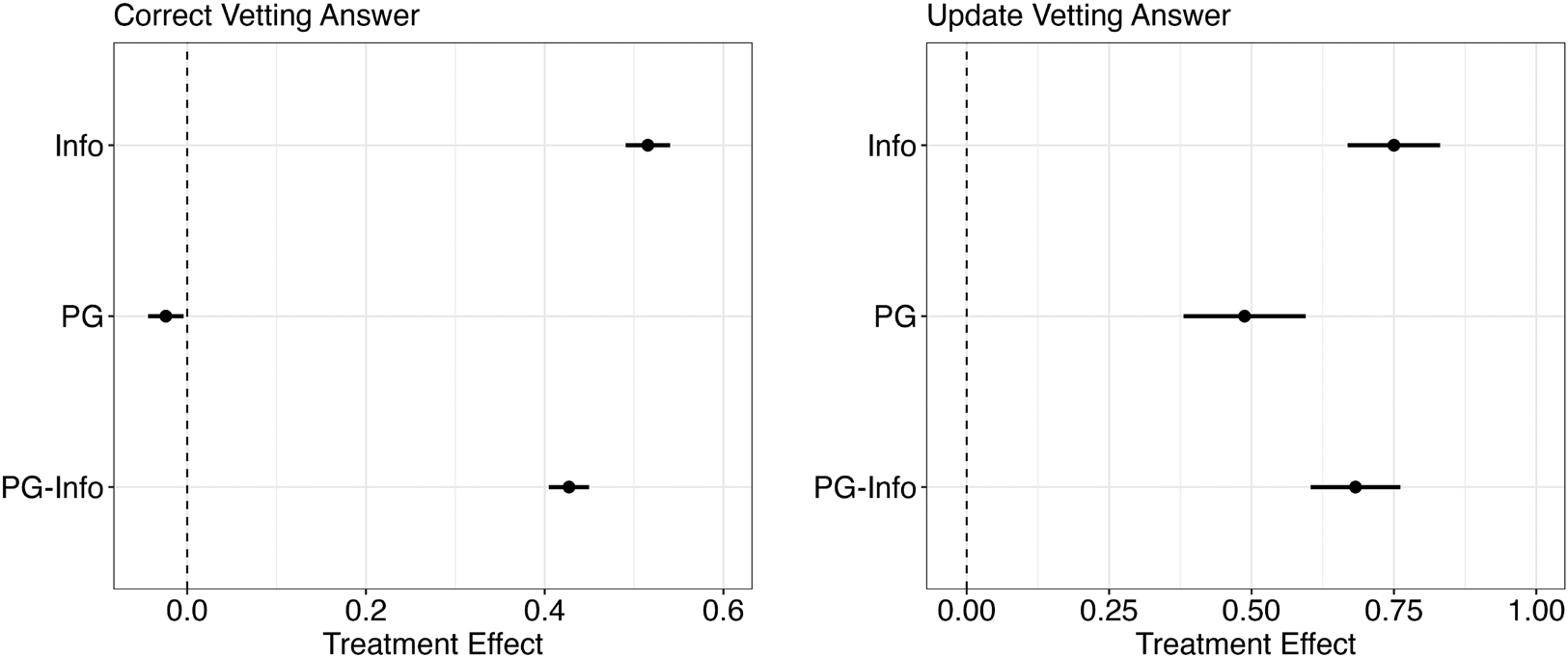

We use two different measures of respondents’ willingness to update misperceptions about the refugee vetting process. The first is a binary variable coded as 1 if respondents correctly answered the post-experimental vetting question by stating that refugees are typically vetted for 18–24 months, and 0 otherwise. The second measure subtracts respondents’ pre-experimental answer from the post-experimental answer to the vetting question, indicating whether respondents updated their perceptions of how long the process takes. The treatment effects on both of these outcomes are shown below in Figure 2. Treatment effects on the inclusion outcomes—the feeling thermometer, attitudes toward the refugee cap, and willingness to write a letter to the White House about their refugee cap views—are reported in Figure 3.

Figure 2. Treatment effects on misperception outcomes.

Note: Treatment effects on likelihood of answering correctly about the length of vetting (left) and updating vetting answer more accurately from pre to post (right). Full regression results that follow the PAP specifications, inclusive of multiple hypothesis adjustments, are reported in SI, Section 8. 95 percent c.i.

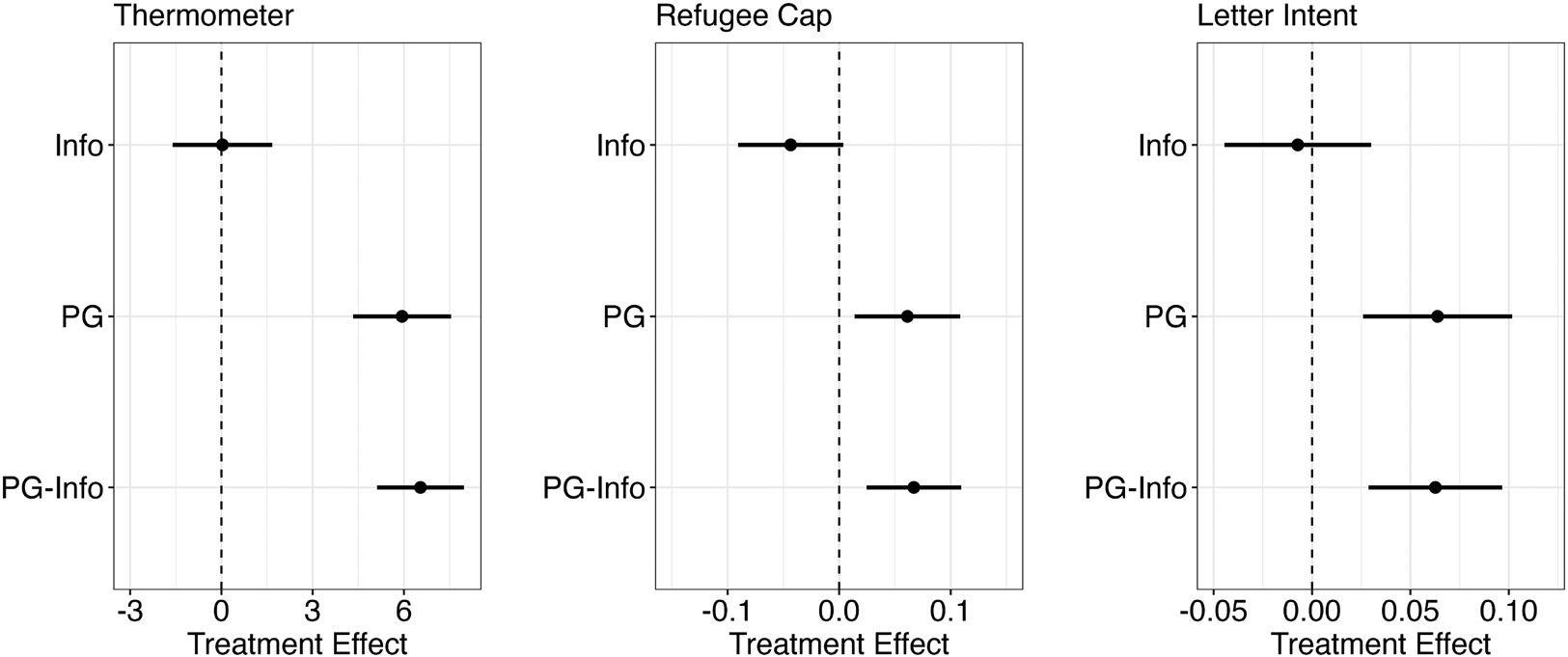

Figure 3. Treatment effects on inclusion outcomes.

Note: Treatment effects on feeling thermometer (left), attitudes toward the refugee cap policy (center), and willingness to write a letter advocating for an increase to the refugee cap (right). Full regression results that follow the PAP specifications, inclusive of multiple hypothesis adjustments, are reported in SI, Section 8. 95 percent c.i.

We discuss each of our hypotheses in turn. Our first hypothesis predicted limited effects of our information-only treatment. Indeed, we designed our vignette to provide information we knew to be new and salient for most Americans. As a result, we expect to find an effect on belief-updating. But the existing literature—emphasizing the role of motivated reasoning and the fact that beliefs may be consequences, not determinants, of attitudes—did not give us any reason to expect effects beyond that. The results reflect these expectations. Figure 2 shows that the Info treatment increased correct answers to the vetting question by 50 percentage points relative to the control group. Likewise, the Info treatment substantially increased the likelihood that respondents updated from their pre-experimental answer to the post-experimental answer by choosing a longer period of time. However, as shown in Figure 3, the Info treatment did not strengthen inclusionary attitudes. The treatment produced a precisely estimated null effect on the thermometer outcome and the letter outcome, relative to the control group.Footnote 15

In addition, we note evidence that suggests providing information to correct misperceptions may have a backfire effect on policy preferences. Individuals who received information were more likely to favor restrictive refugee policy than individuals in the control, and this effect is statistically significant at the 90 percent confidence level. Altogether, these results suggest that even when providing information that is new and seemingly relevant to Americans’ attitudes toward refugees, such an intervention has limited inclusionary effects.

Our second hypothesis predicted inclusionary effects of perspective-getting based on the main findings in this literature to date. Our findings are consistent with this expectation, indicating wide-ranging effects of perspective-getting. As shown in Figure 3, we see a significant increase in responses to the feeling thermometer, with an average increase of six percentage points. This increase is somewhat larger than findings from similar studies, including Williamson et al. (Reference Williamson, Adida, Lo, Platas, Prather and Werfel2021). We also observe an increase in preferences for inclusionary refugee policy in the PG treatment group, which is similar in magnitude to the effect of canvassing on support for transgender laws in Broockman and Kalla (Reference Broockman and Kalla2016). Finally, we observe an increase in expressed willingness to write a letter supporting these policy views, also similar in magnitude to the effect of perspective-getting on letter writing in Adida et al. (Reference Adida, Lo and Platas2018).

In sum, all inclusionary outcomes increase in the PG condition. On the other hand, as shown in Figure 2, the PG treatment does not increase the likelihood that respondents answer the vetting question correctly. The PG treatment does increase how many respondents update their answer to a longer time period, perhaps because Abdi references feeling stuck in the refugee camp. However, this effect is weaker than that of the Info treatment and is driven by a small number of respondents overcorrecting by choosing the longest-possible (and also incorrect) answer choice. These results on the misperception outcomes are unsurprising given that our perspective-getting treatment provided no factual information about the refugee vetting process. Altogether, these results provide compelling evidence of the effectiveness of perspective-getting on changing attitudes toward an out-group, insofar as we designed this intervention as a hard test.

Finally, as per our third hypothesis we examine whether combining information-correction with perspective-getting enhances the effectiveness of each individual strategy. We proposed that perspective-getting might open people up to accepting new information, while new information might alleviate the potential for empathy bias.

The coefficients for the PG-Info treatment in Figures 2 and 3 demonstrate a statistically significant effect on all four outcomes. With the incorporation of the vetting information into the perspective-getting vignette, respondents became substantially more likely to answer the vetting question correctly and to update their vetting answer from their pre-experimental to post-experimental responses. Likewise, the combined treatment produced warmer attitudes on the feeling thermometer and increased willingness to write a letter to the president supporting a more inclusive refugee policy. Importantly, the negative effect of information-only on respondents’ policy preference also disappeared: when the information is delivered as part of a perspective-getting narrative, the effect is inclusionary.

Does this combined treatment work above and beyond the effects of Info and PG individually? In Figure 4, we show the effects of PG-Info relative to responses in the Info treatment group. The right-hand graph presents results using our pre-registered measure of vetting (which captures whether or not the respondent updated to a more accurate answer between pre and post-treatment), while the left-hand graph presents results using our alternative, non pre-registered measure of vetting (capturing whether the respondent provided a longer vetting period). Together, these figures suggest that some respondents in the PG-info condition provide longer vetting times than respondents in the Info condition. Yet, our pre-registered analysis indicates no statistically significant difference on updating between the two conditions.

Figure 4. Comparing effects of Info and PG-Info on misperception outcomes.

Note: Effect of PG-Info compared to Info on answering correctly about the length of vetting (left) and updating vetting answer more accurately from pre to post (right). Full regression results that follow the PAP specifications, inclusive of multiple hypothesis adjustments, are reported in SI, Section 8. 95 percent c.i.

In Figure 5, we compare the effects of the combined PG-Info treatment on the inclusion outcomes relative to the PG treatment. Here we see that the combined treatment modestly out-performed the PG treatment in generating warmth toward refugees, but the difference is not statistically significant. Attitudes toward the more inclusive refugee policy and willingness to write a letter supporting that policy were nearly identical in the two groups. Thus, combining information with perspective-getting does not erode the effectiveness of the latter, and if anything may modestly improve it.

Figure 5. Comparing effects of PG and PG-Info on inclusion outcomes.

Note: Effect of PG-Info compared to PG on feeling thermometer (left), attitudes toward the refugee cap policy (center), and willingness to write a letter advocating for changes to the refugee cap (right). Full regression results that follow the PAP specifications, inclusive of multiple hypothesis adjustments, are reported in the SI, Section 8. 95 percent c.i.

Together, these results suggest the combined treatment offers additive but not interactive benefits. The strategy of combining information and perspective-getting seems to be effective in moving all four outcomes in an inclusionary direction. However, combining the two treatments does not enhance the effect of each individual strategy. The benefit of a combined strategy, therefore, is in its ability to shape a more comprehensive set of outcomes that advocates may care about. Though this evidence remains suggestive, the effects of the PG-Info treatment on the policy outcome also implies that incorporating information within a perspective-getting narrative can protect against potential backfire effects.

4. Discussion

Corrective information and perspective-getting are common strategies that advocates use to increase inclusive attitudes toward refugees, as well as other outgroups. This article identifies the limitations of each strategy and offers and tests arguments for why combining the two might offer a solution.

Our findings help us understand the extent and limit of each inclusionary strategy. First, we find that information correction does increase updating, but it has no effect on any other measure of refugee inclusion. Second, we find that even a hard test of perspective-getting increases refugee inclusion. Third, we find that a combined intervention does not enhance the effectiveness of each individual strategy: the effects of information and perspective-getting combined are additive, not interactive. Fourth, we find that a combined intervention does not erode the effectiveness of either strategy alone. Providing information does not make perspective-getting any less effective at improving refugee attitudes and behaviors and may in fact counter backlash, while embedding the information in a refugee narrative modestly reduces updating but still generates large improvements in accuracy.

One potential limitation of the information treatment is that respondents interpreted the lengthy vetting process as an indication of bureaucratic incompetence rather than a thorough screening of security risks. We think this possibility is unlikely, since the treatment not only included information about the length of the process, but also incorporated information about how many US agencies participate in the vetting and the types of checks they perform. To further address this possibility, we analyzed respondents’ written summaries of the treatment using topic models. Of the 1,901 respondents who received the Info treatment, only 14 percent, or 271 respondents, wrote nonsense in response to this prompt. And, as shown in the topics model in SI, Section 8, none of the most common topics appear to focus on bureaucratic incompetence.

Another concern is that our largely survey-based design captures what individuals claim to prefer in a survey, rather than more meaningful behavior such as voting or advocacy. In SI, Section 8, we offer two additional analyses that increase our confidence in the meaningfulness of our results. First, we test whether respondents rushed through the survey, and in particular, whether they were more likely to rush through if given certain treatments rather than others. This analysis shows that, as expected, respondents who received longer treatments spent more time on the survey; but post-treatment, the length of time spent on each survey was statistically equivalent.Footnote 16 Second, we manually recode each letter to discard nonsensical text and to make sure that respondents’ actual letters were consistent with the sentiment they had claimed they wanted to convey.

This analysis of letter writing, which we present in SI, Section 8, shows three key results. First, our results hold when we analyze treatment effects on our recoded variable (discarding non-sensical text). Second, we find relatively few instances of valence mismatch between the tone of the letter and the option respondents chose in the type of letter (positive or negative) they said they would write. Finally, although the frequency of nonsensical letters is not trivial (approximately 47 percent), writing nonsense is not significantly correlated with treatment. Together, these findings indicate that respondents were not rushing through the survey meaninglessly, a conclusion further reinforced by our topic model analyses, showing that the majority of letters included content relevant to the topic of refugee policy.

Our findings have implications within and beyond academia. First, we shed light on the complicated relationship between information and attitudes, revealing that individuals may update factual beliefs without shifting their policy or personal preferences. This finding reinforces research questioning the role of misinformation in explaining exclusion (Hopkins et al., Reference Hopkins, Sides and Citrin2019; Huang, Reference Huang2023). Second, we provide evidence of both the promise and limits of empathy-based interventions: on one hand, these interventions are effective even with a “hard” case (a Muslim refugee). On the other hand, perspective-getting had no effect on updating beliefs about security checks on refugees, and it did not enhance the effect of information-correction on updating these beliefs. These results suggest that perspective-getting is less likely to shift stereotypical beliefs about outgroups that are linked to misperceptions, which may have implications for the durability of its effects on other inclusive attitudes and behaviors. Third, we find no backlash or unintended effect of combining the two strategies. While these interventions do not enhance one another, there are additive effects. In other words, these interventions complement each other. In fact, the marginal backfire effect of information-correction on policy preferences disappears when information is combined with a perspective-getting narrative.

This leads us to the key implication of our findings beyond academia. Public opinion about refugees is an increasingly salient factor in refugee resettlement policy. Refugee advocates use information-provision and narrative strategies to influence public opinion about refugees. Our study shows that combining the two strategies may help advocates achieve their goals, and quell concerns about potential backlash. Bundling information into a perspective-getting narrative may enable refugee advocates to simultaneously improve beliefs about and warmth toward refugees, as well as increase policy preferences and behavior that enhance refugee inclusion.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2025.1.

To obtain replication material for this article, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/0KSG0T.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank seminar participants at the Empirical Studies of Conflict annual meeting (2022), the Stanford and ETH Zurich Immigration Policy Lab (2022), the University of California Berkeley (2023), the University of Pennsylvania (2022), the University of Texas Austin (2023), and Yale University (2022). The authors thank Yawen Zhang for research assistance. All errors are our own. Replication data are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/0KSG0T.