Introduction

Intranasal packing is well recognised as the primary treatment modality for epistaxis when simple measures such as direct pressure and cautery do not suffice.Reference Kundi and Raza 1 – Reference Biswas and Mal 3 Nasal packing is recommended by both the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the British Medical Journal Best Practice guidance after failure of these basic interventions. 4 , 5 Both guidance documents recommend non-dissolvable packing and in-patient admission in light of the risk of complications and pack displacement. Despite a move towards directed therapy using endoscopes and cautery instruments, nasal packing remains the mainstay of epistaxis management within secondary care.Reference Evans, Young and Adamson 6 This may in part be because of the ease and availability of packing.Reference Badran, Malik, Belloso and Timms 7

There are numerous nasal packs available, both dissolvable and non-dissolvable. In general, intranasal pack choice is guided by availability, cost and preference. This systematic review aimed to identify evidence for when, and in which setting, intranasal packing should be used. In addition, we sought to evaluate which forms of packs should be endorsed as optimum treatment on the balance of benefits, risks, patient acceptability and economic assessment. The aftercare of patients, in terms of admission, duration of pack use and observation after pack removal in the case of non-dissolvable packs, was also reviewed.

Aims

This review aimed to address the following key clinical questions that were identified relating to dissolvable and non-dissolvable nasal packs: when should dissolvable or non-dissolvable packing be used?; which packs provide optimum treatment on the balance of benefits, risks, patient acceptability and economic assessment?; who should pack the patients?; should packed patients be admitted?; when should non-dissolvable packs be removed?; and is there a role for the removal of dissolvable packs, and when should this occur?

Materials and methods

This work forms part of a set of systematic reviews designed to summarise the literature prior to the generation of a UK national management guideline for epistaxis. This review addresses two research domains: dissolvable and non-dissolvable nasal packs. A common methodology has been used in all reviews, described in the first of the publications.Reference Khan, Conroy, Ubayasiri, Constable, Smith and Williams 8 Studies were only included if they primarily involved patients aged 16 years and above treated for epistaxis within a hospital environment. Search strategies for the two domains were kept separate, but the evidence was assessed together given the significant overlap. The search strategy can be found in the online supplementary material that accompanies this issue.

Results

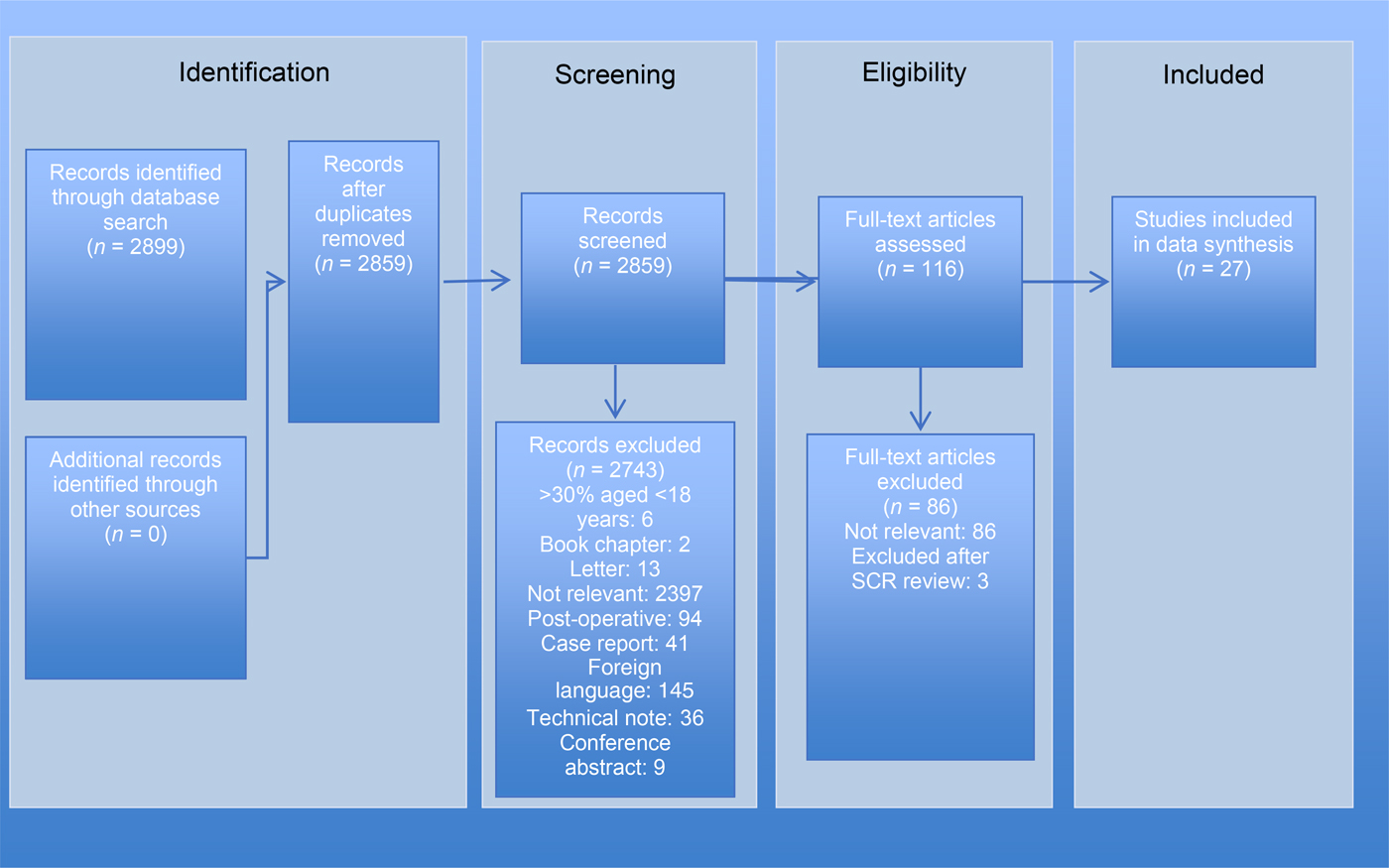

Twenty-seven eligible studies were identified relating to non-dissolvable packs (Appendix I) and nine relating to dissolvable packs (Appendix I). Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the search and article selection process.

Fig. 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (‘PRISMA’) diagram for the non-dissolvable packs review, mapping the number of records identified, included and excluded during different review phases. SCR = ??

Fig. 2 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (‘PRISMA’) diagram for the dissolvable packs review, mapping the number of records identified, included and excluded during different review phases.

Summary of evidence

Indications for nasal packing

The initial management of epistaxis involves simple measures such as the application of pressure, followed by cautery. Epistaxis can either be anterior, which is often self-limiting, or posterior.Reference Pollice and Yoder 9 In most studies, packing was advocated for patients in whom such basic measures failed; however, no specific guidance was provided regarding the optimum duration for such measures. Singer et al. specified 15 minutes of pressure followed by a further 15 minutes of pressure after the application of a topical nasal decongestant if epistaxis persisted.Reference Singer, Blanda, Cronin, LoGiudice-Khwaja, Gulla and Bradshaw 10 Thereafter, epistaxis management was escalated. In the studies that did specify when packing should be employed, the range of time for simple pressure and cautery prior to nasal packing varied from 30 minutes to 2 hours.Reference McGlashan, Walsh, Dauod, Vowles and Gleeson 2 , Reference Badran, Malik, Belloso and Timms 7 , Reference Corbridge, Djazaeri, Hellier and Hadley 11

The commonly used non-dissolvable packs include nasal tampons, alginate-covered nasal balloons, and ribbon gauze which may be impregnated with bismuth iodoform paraffin paste. To avoid gaps in evidence, topical gel agents (gelatine-thrombin matrix haemostatic sealants FloSeal® and Surgiflo®, and fibrin sealants Tisseel® and Evicel®) have been included in this dissolvable pack section.

There is a paucity of good quality evidence supporting the use of dissolvable packs. However, with no reported complications in the literature, dissolvable packs appear safe to use in acute epistaxis. A prospective randomised controlled trial (RCT), which included 70 patients, supported using FloSeal over Merocel® packs following failed conservative measures such as nose pinching in anterior epistaxis (level 1b evidence).Reference Mathiasen and Cruz 12 The re-bleed rate within the first 7 days was also lower in those treated with FloSeal (14 per cent vs 40 per cent; p < 0.05).Reference Mathiasen and Cruz 12 Additionally, dissolvable packing can be used in anterior epistaxis following failed cautery or anterior pack use in an effort to avoid surgical intervention, although the evidence for this is weak (level 2b).Reference Kundra, Cho, Sahota, Pau and Conboy 13 , Reference Shikani, Chahine and Alqudah 14 There is evidence (level 2b) to support the use of dissolvable packing in posterior epistaxis.Reference Bhatnagar and Berry 15 – Reference Kilty, Al-Hajry, Al-Mutairi, Bonaparte, Duval and Hwang 17 In selected coagulopathic patients who fail to respond to either silver nitrate cautery or non-dissolvable packs, fibrin sealant appears to be efficacious (level 4 evidence – weak cohort study);Reference Walshe 18 however, there are significant cost implications, as FloSeal is currently considerably more expensive than the non-dissolvable packs available, and the evidence we present is based on a single RCT.

Nasal packing should be performed in a setting with appropriate lighting and equipment.Reference Kundi and Raza 1 , 4 Epistaxis patients are usually managed by healthcare professionals other than otolaryngologists at first presentation, and often by junior members of the team who may not be experienced in nasal pack insertion.Reference Upile, Jerjes, Sipaul, El Maaytah, Singh and Hopper 19 Those patients who require escalation of treatment subsequently arrive under the care of the ENT team only once they have been packed.

Glicksman et al. performed an RCT, and demonstrated that both computer-assisted learning and text learning relating to nasal packing (ribbon gauze and nasal tampon) improved an individual’s ability to perform this procedure.Reference Glicksman, Brandt, Moukarbel, Rotenberg and Fung 20 The computer-assisted learning group were able to learn the skill more effectively (level 1b evidence).Reference Glicksman, Brandt, Moukarbel, Rotenberg and Fung 20 However, their training time was longer than those who received text-based learning. A study by Lammers (involving ribbon gauze packing on a training model) further supports the concept of training in nasal packing.Reference Lammers 21 The author concluded that practical training allows the individual to learn and retain the skills better than observational training. The group also noted that, over time, if the skill was not used, the ability to perform it diminished equally.

Training (computer-assisted learning and simulation) in both anterior and posterior nasal packing provides a significant benefit, by increasing the ability to adhere to a department protocol,Reference Lammers 21 improving practitioners’ confidence, enabling an increased amount of gauze to be packed,Reference Sugarman and Alderson 22 and improving non-specialists’ speed and efficacy in packing (level 1b).Reference Glicksman, Brandt, Moukarbel, Rotenberg and Fung 20 A retrospective observational study by Evans et al. found that patients packed by emergency department staff were more likely to require further treatment in the form of either nasal packs or cautery when compared with patients packed by ENT department staff (p = 0.004; level 2c evidence).Reference Evans, Young and Adamson 6 Conversely, there was a significant difference in the length of admission, with ENT-packed patients having a longer admission (2.54 days vs 2.86 days; p = 0.0012; level 2c evidence).Reference Evans, Young and Adamson 6 This may be because those who required ENT input had more severe epistaxis or associated co-morbidities, though the authors did not expand upon this in the study.

FloSeal and fibrin sealants should only be applied by those experienced in their use. They are, however, simple to use and could be administered by appropriately trained non-specialists. In posterior bleeds, evidence supports the use of adjuncts with dissolvable packs, such as endoscopic identification of the specific bleeding pointsReference Shikani, Chahine and Alqudah 14 – Reference Côté, Barber, Diamond and Wright 16 , Reference Walshe 18 or the use of a Foley catheter,Reference Mathiasen and Cruz 12 , Reference Kilty, Al-Hajry, Al-Mutairi, Bonaparte, Duval and Hwang 17 to prevent spillage posteriorly. In these cases, relevant expertise in such techniques is required. Techniques involving endoscopic instrumentation are likely to be beyond the competence of a non-specialist and should be reserved for suitably trained ENT specialists.

Effectiveness of nasal packing

Evidence for the efficacy of individual packs is limited to a small selection of studies. The reported re-bleed rates appear similar for Rapid Rhino® and Merocel non-dissolvable packs.Reference Badran, Malik, Belloso and Timms 7 , Reference Moumoulidis, Draper, Patel, Jani and Price 23 There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients requiring repacking for bleeding after the initial placement of either Merocel or bismuth iodoform paraffin paste packs for anterior epistaxis.Reference Corbridge, Djazaeri, Hellier and Hadley 11

Two studies compared traditional non-dissolvable packing to Kaltostat® (calcium alginate). Murthy et al. packed patients with bismuth iodoform paraffin paste during a five-month period, followed by Kaltostat during a six-month period, and they analysed re-bleed rates and other patient outcome measures.Reference Murthy, Christodoulou, Yatigammana and Datoo 24 The use of bismuth iodoform paraffin paste led to a longer duration of packing and a higher rate of epistaxis recurrence (no statistical analyses were performed).Reference Murthy, Christodoulou, Yatigammana and Datoo 24 Xeroform® (bismuth tribromophenate), a non-dissolvable pack, had similar re-bleed rates and levels of patient-reported discomfort to those of Kaltostat.Reference McGlashan, Walsh, Dauod, Vowles and Gleeson 2

Rapid Rhino inflatable packs are reported to be easier to insert for healthcare professionals.Reference Badran, Malik, Belloso and Timms 7 There is no evidence of additional clinical benefit from the increased ipsilateral pack pressure when using a contralateral pack in the setting of unilateral bleeding.Reference Hettige, Mackeith, Falzon and Draper 25 Although the volume of air used to inflate a Rapid Rhino corresponds to a linear increase in pressure, for a given volume of inflation, a wide variation exists in the intranasal pack pressure attained in different individuals.Reference Mackeith, Hettige, Falzon and Draper 26

The literature suggests that Rapid Rhino packs are most tolerated by patients, with significantly less pain on insertion and removal compared with both the Merocel pack and the less commonly used Rhino Rocket® pack (level 1b evidence).Reference Singer, Blanda, Cronin, LoGiudice-Khwaja, Gulla and Bradshaw 10 , Reference Moumoulidis, Draper, Patel, Jani and Price 23 No differences in discomfort were observed between bismuth iodoform paraffin paste and Merocel packs.Reference Corbridge, Djazaeri, Hellier and Hadley 11 In a study by Nikolaou et al., non-dissolvable packs were found to be more painful in comparison to nasal cautery.Reference Nikolaou, Holzmann and Soyka 27

The cost implications of using non-dissolvable packs are difficult to determine from the literature. Retrospective analysis within a Swiss clinic revealed that the costs associated with Rapid Rhino pack use were primarily influenced by whether treatment was delivered on an in-patient or out-patient basis.Reference Nikolaou, Holzmann and Soyka 27 There are no high-level studies reporting re-admission rates to recommend the use of one pack over another.

In the absence of any comparative study, we are unable to support the use of a specific dissolvable pack over any other. FloSeal is the most reported product in the literature. It appears to be superior to Merocel packing with respect to patient comfort, ease of use and control of bleeding in anterior epistaxis.Reference Mathiasen and Cruz 12 There are studies, albeit less robust, that support its use in posterior epistaxis also.Reference Côté, Barber, Diamond and Wright 16 , Reference Kilty, Al-Hajry, Al-Mutairi, Bonaparte, Duval and Hwang 17 Unfortunately, no studies compare FloSeal to Rapid Rhino packs, which are seen by many as the optimal non-dissolvable packing.

Surgicel® and Chitosan® gauzes have also been successfully utilised, again with good patient tolerance. However, these appear to require more expertise because of the need for endoscopic insertion, possibly offsetting any monetary advantage that may be attained by admission avoidance.Reference Shikani, Chahine and Alqudah 14 , Reference Bhatnagar and Berry 15 FloSeal, on the other hand, can be used by emergency department staff without specialist input,Reference Mathiasen and Cruz 12 , Reference Kundra, Cho, Sahota, Pau and Conboy 13 and may have economic advantages with perceived lower admission and re-bleed rates.Reference Kundra, Cho, Sahota, Pau and Conboy 13 Dissolvable packs appear safe, with few, minor complications reported.Reference Wang, Tai, Tsou, Tsai, Li and Tsai 28 Therefore, although a robust economic assessment of FloSeal and dissolvable packs more generally has not been reported, it would appear that there might be potential for their use earlier in the epistaxis management pathway.

Management after pack insertion

The NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary and British Medical Journal best practice guidelines both recommend admission of patients following nasal pack insertion, to monitor for complications and pack displacement when using traditional non-expandable packs.

High-level evidence within the literature regarding the management of patients after packing is limited. Not all patients managed with inflatable non-dissolvable packs require admission (level 2b evidence). Patients undergoing anterior nasal packing can be safely managed as out-patients with a pack in situ, with no adverse events.Reference Van Wyk, Massey, Worley and Brady 29 Evidence to support this approach includes a 73 per cent reduced admission rate of patients undergoing anterior nasal packing placed by emergency staff, after the introduction of a new epistaxis protocol (level 2c).Reference Upile, Jerjes, Sipaul, El Maaytah, Singh and Hopper 19

Alternatively, early discharge following pack removal is acceptable, following a recommended 4-hour observation period in appropriate patients. In a small prospective study of 50 patients, 20 per cent experienced re-bleeding events, of which 96 per cent occurred within 4 hours.Reference Mehanna, Abdelkader, Albahnasawy and Johnston 30

Complications associated with nasal pack placement include obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) and infection. Obstructive sleep apnoea may be induced, or underlying OSA markedly exacerbated, following nasal packing.Reference Wetmore, Scrima and Hiller 31

The role of prophylactic antibiotics remains uncertain. Bacteraemia is reported in 12 per cent of patients with posterior packs.Reference Herzon 32 Use of topical antibiotics was associated with more single micro-organism, Gram-positive growth, in contrast to mixed and predominantly Gram-negative growth in the non-antibiotic group.Reference Herzon 32 Evidence for prophylactic systemic antibiotics is limited by sample size and study design. A blinded, pilot RCT on posterior packing reported increased rates of foul-smelling packs and predominantly Gram-negative growth in the control arm not receiving intravenous antibiotics, but no significant differences in infective complications (level 1b).Reference Derkay, Hirsch, Johnson and Wagner 33 These findings were supported by the contemporary literature.Reference Pepper, Lo and Toma 34 Further studies have not identified differences in bacterial growth following anterior packing for more than 24 hours.Reference Biswas and Mal 3 A protocol-led reduction in prophylactic oral antibiotic usage had no consequential increase in complication and re-bleed rates.Reference Biggs, Nightingale, Patel and Salib 35

The literature reports pack removal at a wide range of times after insertion. Benefits of early removal may exist for the patient, with packing for 12 hours shown to be as effective as packing for 24 hours, with significantly less discomfort.Reference Kundi and Raza 1 Nasal packing beyond 3–5 days had no additional benefits, with no significant impact on re-bleed rates.Reference Shargorodsky, Bleier, Holbrook, Cohen, Busaba and Metson 36

There is no evidence to support the admission of patients in which epistaxis has been successfully arrested by dissolvable packs.Reference Mathiasen and Cruz 12 , Reference Kundra, Cho, Sahota, Pau and Conboy 13 , Reference Bhatnagar and Berry 15 , Reference Côté, Barber, Diamond and Wright 16 Patients with significant co-morbidities or those with a lack of social support may require admission. The number of epistaxis patients requiring admission for these reasons can be significant, with half the trial participants admitted only for these indications in one study.Reference Côté, Barber, Diamond and Wright 16 Only one study offered any suggestion on the length of observation required prior to discharge (1 hour).Reference Kilty, Al-Hajry, Al-Mutairi, Bonaparte, Duval and Hwang 17

There was little evidence to support the removal of dissolvable packs, with the majority of studies leaving the packing material in situ. One paper described washing out excess FloSeal with saline, without any reported complications.Reference Kilty, Al-Hajry, Al-Mutairi, Bonaparte, Duval and Hwang 17 In studies where large amounts of Surgicel or Kaltostat were used to completely fill the nasal cavity, packing was typically removed 24–72 hours later.Reference McGlashan, Walsh, Dauod, Vowles and Gleeson 2 , Reference Murthy, Christodoulou, Yatigammana and Datoo 24 , Reference Tibbels 37

Limitations

There are numerous studies describing epistaxis management; however, there is a paucity of high-level evidence. There is insufficient evidence to determine when patients should be packed, and whether admission is required for those with non-dissolvable packs. There is also no clear evidence on the recommended duration of non-dissolvable pack use, or the duration of observation following this. More research is required to determine ongoing long-term sequelae of packing. An economic analysis of the different packs has not been performed.

Heterogeneity among the studies analysed, and a lack of high-level evidence, results in a significant risk of bias at study level. This has been mitigated with regards to FloSeal, with several studies of varying quality from different regions of the world reporting positively on its use. Most of the dissolvable pack studies included in this systematic review scored poorly on the bias assessment (Appendix II), with low numbers of patients, incompletely reported methodology or outcomes, and inadequate follow-up protocols. There were articles that may have been of interest, but were not included in the review because they are written in a foreign language or are unavailable.

Conclusion

Intranasal packing is the mainstay of epistaxis management following first aid measures and cautery. There is evidence demonstrating that simulation training improves the ability to perform this. The efficacy of Rapid Rhino and Merocel packs in controlling epistaxis is similar. However, the ease of insertion and reduced patient discomfort supports the use of Rapid Rhino as the non-dissolvable packing of choice. Regarding dissolvable packing, there is a lack of evidence of efficacy, as opposed to evidence suggesting no efficacy. The evidence synthesised from this systematic review is inadequate to provide clear and confident recommendations based on the questions we set out to answer. Currently, recommending dissolvable packs over other treatment modalities including non-dissolvable packs is inappropriate because of the lack of evidence. However, based on clinical and economic factors, dissolvable packs may have a role in managing acute primary epistaxis, particularly in coagulopathic or high-risk surgical cases. Based on the lack of reported complications, it is sufficient to recommend the continued use of dissolvable packs in units that have adopted such techniques with robust clinical governance protocols, with a call for transparency in reporting and further research.

Acknowledgement

This review was part of an epistaxis management evidence appraisal and guideline development process funded by ENT-UK. The funding body had no influence over content.

Appendix I Summary of studies included in non-dissolvable packing review

Appendix II Summary of studies included in dissolvable packing review