Introduction

The main objective of this paper is to demonstrate the unity of the Hadiqat al-haqiqeh va shariʿat at-tariqeh (The Enclosed Garden of Truth and the Law of the [Sufi] Path–hereafter, Hadiqeh.), also known as Fakhrināmeh and Elāhināmeh. The Hadiqeh is a non-narrative medieval Persian manual of Sufi and political advice composed by the poet Abu al-Majd Majdud b. Ādam Sanāʾi Ghaznavi (d. 1135 CE).Footnote 2 The book served as a model for several mystical poetic texts written in the subsequent centuries, including Rumi’s Masnavi-ye maʿnavi and ʿAttār’s Manteq at-tayr, Elāhināmeh, and Mosibatnāmeh. As a result, it plays a significant role in the history of Islamic mysticism and Persian advice literature.

Written in the masnavi form, the Hadiqeh was dedicated to the Ghaznavid ruler Bahrāmshāh (r. 1117–57 CE).Footnote 3 Each chapter focuses on a particular topic relevant to Sufi and political ethics. Unlike Sanāʾi’s other masnavi, Sayr al-ʿebād elā al-maʿād (The Journey of [God’s] Servants to the Returning Point), the Hadiqeh lacks a story-like narrative, with a particular plot that guides the reader from one event to another in a sequential manner. However, the work can be considered a “non/narrative,” a word that was coined in the mid-1980s and was first used in the fifth issue of Poetics Journal, which included postmodernist debates about narrative. The slash between the two parts of the word is to indicate that even non-narrative works presume some sort of narrative—or to be more precise, unity—for there is a purpose behind the production of each work that connects different sections of the work to one another.Footnote 4 As a result of its non-linear narrative, the Hadiqeh is perceived as a book with “loose organization,” with “parables and anecdotes on a wide variety of subjects.”Footnote 5 Since the Hadiqeh was a model for Rumi’s Masnavi-ye maʿnavi, and so presumably they shared the same format and structure, the common belief is that the Hadiqeh is not a coherent whole. Strikingly, outside the Persian-speaking world, no one has conducted a close textual analysis of the entire Hadiqeh to prove its disunity or unity, and to shed light on the intersection of multiple topics and intellectual currents in the work. Scholarly contributions have been largely limited to the investigation of its general outline—mostly from the perspective of Sufi ethics, as well as the intersection of religion and politics by pioneering scholars such as J. T. P. de Bruijn and Charles-Henri de Fouchécour.Footnote 6 In other words, none have expounded on the politico-pietistic content and narrative of the work. In his recent study, Nicholas Boylston has identified degrees of reality and divine transcendence as two metaphysical principles that create a unity in the message of the Hadiqeh.Footnote 7 Nonetheless, he does not examine each chapter of the work to discuss how it fits within the overall scheme of the text. The reasons behind the dearth of scholarship on the Hadiqeh are manifold. First, the work has multiple recensions, and this has complicated the study of its textual transmission, which itself has led to the production of significantly different printed editions of the work. Second, since Sanāʾi died before organizing the fragments of the work into a volume with proper order, the order of chapters and subchapters may not necessarily reflect the author’s intention. Third, the division of the book into multiple sections, each centering on one concept, has made it difficult to detect the connection between these sections.

The present study, therefore, contains two major sections. The first section discusses the first two aforementioned issues in detail and explains why the complexity of the manuscript tradition of the Hadiqeh should not prevent us from studying the work. The second section argues that the work has a textual unity by providing a possible way of reading it using the existing editions of the work, particularly the most recent edition by Mohammad Jaʿfar Yāhaqqi and Sayyed Mahdi Zarqāni. The Hadiqeh was written not only to serve pietistic purposes—that is, religious preaching—but also to provide advice to Bahrāmshāh. The work’s dual purpose, which may have been one reason behind the production of its multiple recensions, is what ties its different sections to each other. The Hadiqeh was composed as a guide for human perfection or betterment.Footnote 8 As is argued here, in the Hadiqeh, the intellect functions as the tool par excellence to achieve this perfection. In order to access this tool, one must preoccupy oneself with certain pietistic acts that are discussed in different sections of the work. The result of human spiritual perfection is union with the divine Beloved. This philosophical mysticism is what ties the political and the spiritual content of the work to each other. A ruler who has achieved union with God and has become His true manifestation, is God’s true vicegerent and can lead society to happiness. This study aims to open a door to further scholarly debates about this invaluable but understudied work in the history of Persian literature.

A Chaotic Jumble and the Loss of Authorial Intent

The complex textual history of Sanāʾi’s poetry, to a significant extent, lies in a multi-staged process that resulted in the production of significantly different manuscripts and editions of his poems, including those of the Hadiqeh. De Bruijn has identified three recensions of the Hadiqeh, two of which were produced by the poet himself during his lifetime and one shortly after his death by his disciple Moḥammad b. ʿAli ar-Raffāʾ.Footnote 9 The first recension, entitled Fakhrināmeh, was prepared by the author upon the invitation of his royal patron, Bahrāmshāh of Ghazna, and was presented at the court. It contained two sections where the poet apologized to the Ghaznavid ruler for not becoming attached to his court due to his pietistic lifestyle.Footnote 10 This recension, as Modarres-e Razavi and de Bruijn argue, draws its name from the epithet of the Ghaznavid ruler, “Fakhr ad-Dawleh” or “Fakhr as-salātin fi al-Islām.”Footnote 11 It most likely included a major part of the politico-ethical section of the Hadiqeh and multiple sections from other chapters of the book.Footnote 12 The second draft was an extended version of the work, having around ten thousand verses, and was presumably sent to Khwājeh Emām Borhān ad-Din, known as “Beryāngar” (d. 1156–57 CE), a renowned preacher in Baghdad. Lastly, according to the introduction of an early manuscript of Sanāʾi’s Kolliyāt (most likely produced at some point in the twelfth or early thirteenth century), the poet died in 529/1135, while he was still organizing a draft of the Hadiqeh.Footnote 13 Sanāʾi, therefore, did not have the chance to finalize and authorize the draft. Thus, Bahrāmshāh assigned ar-Raffāʾ the task of gathering the existing sections of the work and placing them in proper order in a volume. The result was the third recension of the Hadiqeh, an abridged version of the work, having around five thousand verses.Footnote 14 This abridged recension was published in an edition entitled Hadiqat al-haqiqeh va shariʿat at-tariqeh (Fakhri-nāmeh) in 2003 by Maryam Hosayni. Ar-Raffāʾ’s recension contained his introduction to his teacher’s work, which appears in the beginning of many of the manuscripts of the Hadiqeh. In addition to ar-Raffāʾ’s introduction to the Hadiqeh, some manuscripts contain an introduction presumably composed by Sanāʾi himself.

According to ar-Raffāʾ’s introduction, while Sanāʾi was composing his work, “a group of lowly, sightless people” (jamāʿati mokhtasar-e bi-basar) stole fragments of it “with the intention of dispersing the book due to jealousy” (khwāstand ke az ru-ye hasad in ketāb rā motefarreq konand).Footnote 15 Based on the introduction of an old manuscript of the Hadiqeh known as the Kabul manuscript, a person named Mohammad b. Ebrāhim b. Tāher al-Hosayni later found the stolen fragments and returned them to Sanāʾi.Footnote 16 This episode about returning the fragments is not included in other manuscripts of the Hadiqeh, and we cannot be completely certain about its authenticity. However, ar-Raffāʾ’s testimony in his introduction confirms that fragments of the Hadiqeh were stolen before Sanāʾi prepared a draft of almost ten thousand verses for Borhān ad-Din Beryāngar. There were, however, some remaining verses that he had not incorporated into the draft he sent to Beryāngar.Footnote 17 De Bruijn also argues that at the time of Sanāʾi’s death, some fragments of the Hadiqeh may not yet have been incorporated into any of the recensions, and thus later editors may have added them to the work.Footnote 18 Are these fragments the stolen fragments that were returned to Sanāʾi, or are they simply verses that did not fit anywhere in the draft that Sanāʾi sent to Beryāngar? Did Sanāʾi manage to fit these verses into the recension he was preparing for Bahrāmshāh at the end of his life? We cannot be certain.

Based on what was explained above, we have possibly three different drafts of the Hadiqeh, as well as two different introductions to the work. We have some information about the production of the Hadiqeh, which is attested only in the Kabul manuscript. We also know that some sections of the Hadiqeh were stolen at some point during its production. These sections may or may not have been returned to Sanāʾi. If they were, their integrity is questionable. Finally, we know that Sanāʾi was left with some verses that he did not include in the draft he sent to Beryāngar. However, we do not have any other information about these verses. These backdrop considerations imply an exceedingly convoluted textual history.

To all these complications, we should add the popularity of Sanāʾi’s poetry during his life and after his death, which led to the wide circulation and the production of a variety of manuscripts of his works. One major difference between the manuscripts is the difference in the order of the sections of the work, as well as the order of the individual verses.Footnote 19 The production of the oldest extant manuscript of Sanāʾi’s masnaviyyāt including the Fakhrināmeh, known as MS Baǧdatli Vehbi (BV), dated 552/1157—that is, only twenty-three years after Sanāʾi’s death—in Konya, far away from Ghazna, demonstrates the wide circulation of his works. The alteration of primary recensions of the work is attested in a late medieval edition and commentary of the work, entitled Latāʾef al-hadāʾeq men nafāʾes ad-daqāʾeq (Subtleties of the Gardens from Gems of the Details) (c. 1632 CE). The edition was produced by ʿAbd al-Latif ʿAbbāsi, a scribe in the court of the Mughal emperor Shāh Jahān (r. 1628–58 CE) and a renowned commentator of Rumi’s Masnavi-ye maʿnavi. As he indicates in the introduction of the Latāʾef, he undertook the task of editing the Hadiqeh in order to protect the book from alterations.Footnote 20 We must, however, keep in mind that editions of any particular work should be viewed as part of the work’s reception history, since editorial license in manuscript juxtaposition often leads to rearrangements, eliminations, and selections based on perceived textual variations, and this inevitably alters the text. Our access to authorial intention, therefore, becomes clouded in the process of the production of editions. Editions are, in a way, “reconstructions” of a particular text.Footnote 21 ʿAbbāsi’s edition of the Hadiqeh is no exception. Additionally, a medieval work is the product of the mouvences of a given text between its original author and its subsequent authors—that is, scribes, editors, and even minstrels and reciters in Sanāʾi’s literary environment, which was characterized by a partly textual and partly oral culture. In other words, in addition to the vertical movement of a given text throughout history, a text goes through multiple horizontal movements among different individuals and groups of a given cultural milieu.Footnote 22 Each of these authors is part of the collective construction of the work. Therefore, a work is a “complex unity constituted by the collectivity of its material versions.”Footnote 23 In this multi-staged process of the production of a given work, the authorial intention, along with the Ur-text, is lost. The Hadiqeh as passed down to us is in reality a multi-authored text, each author (or modifier) being the source of textual authority.Footnote 24

The study of the Hadiqeh as a work—which encompasses its archetypal version, i.e. the Fakhrināmeh, among other versions—should not be reduced to the study of Fakhrināmeh alone, which according to de Bruijn is most likely reflected in MS BV.Footnote 25 After all, it was the extended (or “vulgate”) version of the work that came to be appreciated and quoted by later authors and thus became influential in the history of Persian literature.Footnote 26 Therefore, when discussing the textual unity of the Hadiqeh, our guiding question should not be “what did Sanāʾi intend to convey?” The question should rather be “how does this unity manifest through the Hadiqeh regardless of the order of its chapters and subchapters?” In other words, we cannot, and should not, try to understand the unity of the text in light of the way Sanāʾi intended to organize the fragments that he had composed, for two reasons: first, Sanāʾi never found the opportunity to organize the fragments and the closest we can get to his version of the work is through ar-Raffāʾ’s recension, which is not free of alterations for the reasons explained before; in other words, the Ur-text is irretrievable; second, because the masterpiece that traveled through the centuries, was quoted numerous times, and served as a model for subsequent didactic masnavis was the product of a collective act of writing. Sanāʾi’s intent was, therefore, a fraction of the entire picture.

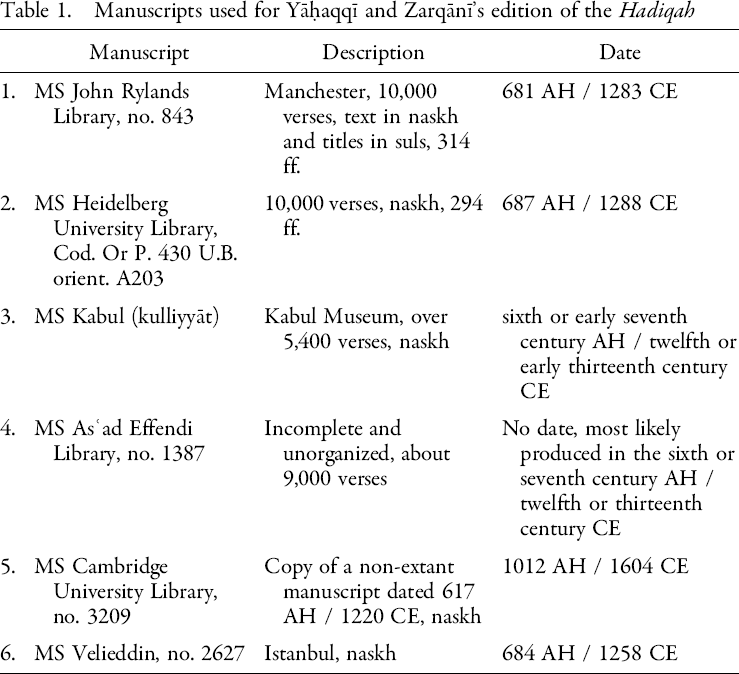

For the purpose of the current study, I am basing my arguments on the most recent edition of the extended version of the Hadiqeh, co-edited by Yāhaqqi and Zarqāni. The two-volume book contains a critical edition of the Hadiqeh and multiple indexes, including an index of all the verses (kashf al-abyāt) and a commentary on some of the difficult verses of the work. The main advantage of this edition over the previous ones is the editors’ use of two manuscripts, which were not available to Modarres-e Razavi and Rawshan when they produced their editions of the vulgate text.Footnote 27 These two manuscripts are MS John Rylands Library, Manchester, no. 843, dated 681/1283, and MS Heidelberg University Library, Cod. Or P. 430 U.B. orient. A203, dated 687/1288, and the editors use the former as their main manuscript. Along with these two manuscripts, four other manuscripts are used in the preparation of this edition: the aforementioned MS K, MS Asʿad Effendi Library, no. 1387, MS Cambridge University Library, no. 3209, and MS Velieddin, Istanbul, no. 2627. Table 1 contains information about the six manuscripts used in Yāhaqqi and Zarqāni’s edition:

Table 1. Manuscripts used for Yāḥaqqī and Zarqānī’s edition of the Hadiqah

The editors have intentionally set aside MS BV in an attempt to create an edition of the extended recension of the Hadiqeh without being too concerned about the Fakhrināmeh. Their edition demonstrates that the majority of the contents of BV had already been incorporated into other manuscripts that belong to the older layer of the Hadiqeh’s textual history—that is, the two main manuscripts used for the production of this edition.Footnote 28 This proves my point about not limiting the study of the unity of the Hadiqeh to Fakhrināmeh, and precisely for this reason I have based the current study on Yāhaqqi and Zarqāni’s edition.

On the Unity of the Hadiqeh: The Hadiqeh as a Town

Understanding the unity of the vulgate Hadiqeh is a challenging task, mainly due to the way a wide array of topics is weaved into the fabric of the work. Medieval Persian and Arabic poems do not lend themselves to modern perceptions of textual unity on the ground of a “logical sequence” of different sections of a given work. The search for unity based on logical order has resulted in misleading methodologies. Some scholars have come to the conclusion that each verse (bayt) is a self-contained unit and should be read and treated independently.Footnote 29 Rejecting the theory of atomism, other scholars searched for the perfect Ur-text that demonstrates a logical coherence and unity within a poem.Footnote 30

The confusion about the unity of medieval Persian and Arabic poetry, to a great extent, lies in the lack of debate about the concept of poetic unity in the medieval Persian and Arabic manuals of literary criticism. Medieval Arabic authors seem to have been more concerned with issues such as poetic imagery and rhetoric, and not much so about the thematic and structural unity of poems. Additionally, information about poetic unity in Persian sources is sparse. To this scarcity of material about poetic unity we must add the lack of analysis of the unity of masnavis in particular. Most examples cited in medieval manuals of literary criticism present ghazals, robāʿis, and, in some cases, qasidehs. So how can we discuss the unity of masnavis, and to what extent can the information we have about unity of other forms of poetry guide us in our understanding of the unity of masnavi as a versatile literary form? There are different types of masnavi, each of which manifests different forms of unity. Romance masnavis such as Nezami’s Layli wa Majnun, and Khosrow wa Shirin, or Jāmi’s Yusof wa Zolaykhā, in addition to their thematic unity, have a linear narrative that unifies their different sections. Some mystical masnavis, such as Sanāʾi’s Sayr al-ʿebad, share this feature. Others, such as ʿAttār’s Manteq at-tayr, have a frame-tale (e.g. the story of the hoopoe and his journey with the birds) that creates a unity within its different sections and anecdotes.Footnote 31 This being said, what are we to do with a massive, multi-dimensional didactic masnavi such as the Hadiqeh, which lacks a linear or framing narrative, and discusses a variety of topics? Are these topics related? If they are, how do they interact with each other to create a unified whole?

Viewing the Fakhrināmeh as “a long sermon,” de Bruijn has already explained some of the possible connections between different sections of the text through a close textual analysis, taking into consideration the circumstances surrounding its production and its didactic function.Footnote 32 However, his concern for finding a logical order for the different sections of the Hadiqeh and the right turning points that connect the sections has led to his description of the vulgate Hadiqeh as “a seemingly random collection of fragments, dealing with a great variety of didactic themes without any clear connection to each other.”Footnote 33 In order to discuss the unity of the Hadiqeh, however, we must not concern ourselves with the order of the sections, again because the vulgate work is the product of multiple reconstructions of the original recension by different medieval authors, including Sanāʾī. We must, however, see if the vulgate work complies with the medieval standards of poetic unity.

To discuss a multi-sectioned work with a lack of clear narrative such as the Hadiqeh, Shams-e Qays ar-Rāzi’s description of poetic unity may be helpful, since the criteria introduced by him can be applied to different genres and forms of poetry. As he explains, what constitutes a beautiful, complex, unified poem is the beauty of its individual constituents, together with the beauty of the poem as a whole. Comparing poetry to the human body in the epilogue of his manual of literary criticism, al-Moʿjam fi maʿāyir-e ashʿār al-ʿajam, Shams-e Qays writes:

The necessary constituents of poetry are correct words, palatable expressions, eloquent phrases and subtle themes, which when poured into the mold of acceptable meters and strung into the string of pleasant baits, are called good poetry, and the whole of [poetic] craft is for nothing but the perfection of its means and necessaries, since the perfection of a person is not achieved without the soundness of individual limbs.Footnote 34

Elsewhere in his work, he makes use of the art of painting and jewelry making as analogies to describe the second criterion for poetic unity—that is, balance and harmony, or “proportionality” in Jerome Clinton’s words:Footnote 35

He [the poet] should be like a skillful painter, who in the composition of designs and in the drawing of the curving branches and leaves places every flower somewhere and draws each branch outward from it, and in the blending of colors uses each color in some place and gives every color to some flower. Where a deep color is appropriate, he does not use a pale one, and where a dark color is appropriate, he does not use a light one, and he should be like a master jeweler, who increases the elegance of his necklace by beauty of combination and proportion of composition.Footnote 36

While the first passage emphasizes the importance of the soundness and elegance of smaller elements within a given poem, the second passage views poetry as a piece of art in which individual elements create a harmonious whole. Based on the above-cited passages, a poem can be considered a successful example of a unified whole so long as its sound and elegant individual parts integrate well into the whole scheme of the work.

To supplement Shams-e Qays’ criteria with Sanāʾi’s own view of his work as a cohesive whole, we should look at the poet’s description of his poem as an architectural structure. In the final chapter of the work, Sanāʾi compares his act of writing to the construction of a town named after him (Sanāʾi-ābād), inclusive of lands, houses, arches, bricks of different kind, trees and other plants, a castle, and a gate.

Though each part of this urban layout has a certain characteristic, function, and makeup, together they create a beautiful, unique, grand whole. The portrayal of the poet as an artisan (a master jeweler, a painter, a weaver, or an architect) and the poem as a work of art designed in a complex and harmonious way was a common method used by Persian poets to indicate the unity of their poems. Farrokhi, for instance, in his famous qasideh dedicated to the Amir of Chaghanian, compares his poem to a “silk robe” (holleh) “spun from his heart” (tanideh ze del), woven from his soul (bāfteh ze jān), “whose composition was discourse” (tarkib-e u sokhan), and “whose patterns were designed by his tongue” (negargar-e naqsh-e u zabān).Footnote 39 Similarly, Nāser-e Khosrow compared his Divān to a garden and one of his qasidehs to a castle built in the middle of the garden (qasri konam qasideh-ye khwod rā, dar u), whose veranda and rose garden are made of verses (az bayt-hāsh golshan wa ivān konam), and whose foundation is the meter “mafʿul fāʿelāt mafāʿil faʿ” (mafʿul fāʿelāt mafāʿil faʿ/bonyād-e in mobarak bonyān konam).Footnote 40 Thus, when Sanāʾi compares his work to a complex architectural work, he is using a common trope to indicate that there is a unity within his work, and that different sections of the work are interconnected and harmonious.

Here, in order to verify Sanāʾi’s claim about the unity of the Hadiqeh, I will only focus on one aspect of the unity in his work, that is, thematic unity, taking into account the criteria of unity introduced by Shams-e Qays. If a close examination of the major themes discussed in different chapters of the Hadiqeh demonstrates that the work is a harmonious whole and that each of its sections contributes to an overall message, then we will have fulfilled our task. The goal is to examine whether the Hadiqeh follows a particular line of thought, and not necessarily a linear line of thought. This line of thought is what renders the Hadiqeh a non/narrative work.

The Purpose of the Hadiqeh

In the last chapter of the Hadiqeh, Sanāʾi dedicates the work to Bahrāmshāh and states that the reason behind writing it was to share his wisdom with the king: “When [this] slave witnessed the king’s kingship and justice / He shared the wisdom he had with him [the king].”Footnote 41 In multiple verses of this chapter, Sanāʾi praises his poetry for knowledge and wisdom embedded in it. For instance, he states:

Or: “Every single verse of it [the Hadiqeh] is a world of knowledge / Each single meaning is a sky of knowledge.”Footnote 43

The purpose of writing the work is explained similarly in both ar-Raffāʾ and Sanāʾi’s introductions to the Hadiqeh. Since Sanāʾi’s introduction is not included in Yāhaqqi and Zarqāni’s edition, here I will cite ar-Raffāʾ’s introduction, which bears significant similarities to Sanāʾi’s introduction. I include Sanāʾi’s introduction in the notes for those interested.

Ar-Raffāʾ categorizes the people who have access to divine knowledge into three groups: first, prophets; second, their followers, which he identifies as religious scholars (ʿolamāʾ); and third, the sage poets (hokamāʾ-e shoʿarāʾ)—that is, poets whose words contain wisdom. Citing an Arabic saying attributed to the Prophet, “Indeed wisdom is from poetry” (Enna men ash-sheʿr la-hekmah), ar-Raffāʾ highlights the status of sage poets as close people and relatives (zo al-arhām) to the prophets.Footnote 44 The sum of ar-Raffāʾ’s argument here and the above description of Sanāʾi’s Hadiqeh as poetry containing wisdom for the king could suggest that ar-Raffāʾ possibly viewed Sanāʾi as a sage poet and therefore a divinely inspired advisor to the king.

In addition to the purpose of providing the Ghaznavid ruler with advice, ar-Raffāʾ provides an additional purpose behind the production of the work—that is, to facilitate the readers “to be dispassionate about [their corporeal] existence” (az wojud del sard konand) and “to whisper to themselves, ‘desire death if you are honest’” (wa bā khwod in nedā konand ke: “fa-tamannaw al-mawt en kontom sādeqin”).Footnote 45 This would then lead them to “become loving towards the Beloved” (bā dust garm shawand). Love would then drive them to the state of union with Him, because “[spiritual] death unites the lover and the beloved” (al-mawt yusel al-habib elā al-habib). In this state, “He loves them and they love Him” (yohebbohom wa yohebbunah).Footnote 46 Thus, embarking on a spiritual journey, which starts with detachment from material existence and ends with annihilation, leads to the experience of reciprocal love, intimacy, and union with the Divine.

Based on the above information, we should look for two sets of advice in the Hadiqeh: advice that is appropriate for a king, i.e. politico-ethical advice, and advice that is appropriate for a seeker of the Truth. The modern perception of these two sets of advice—that is, courtly and spiritual or profane and sacred—as contrasting is one major element that contributes to the perception of the Hadiqeh as a fragmentary poem. Nonetheless, there are verses throughout the text in which spiritual advice is given to a king instead of a seeker of the Truth. As modern readers, we might expect that a king receives politico-ethical advice that would help him tend to the matters related to the government and his subjects. We may think that a king who is completely devoted to his spiritual life and is detached from the material world is not a competent ruler, for who can neglect the material world but at the same time be interested in it? For medieval audiences, these two sets of advice were not necessarily contrasting. The intersection between the sacred and profane was a central element in medieval works of various genres, and the idea of spiritual perfection was a point of conjecture for different intellectual currents, including political ethics, philosophy, and mysticism.Footnote 47 Yet how does Sanāʾi synthesize these two sets of advice through his didacticism? The intersection of sacred and profane in Sanāʾi’s poetry has been explained by de Bruijn and Lewis—more so, however, in relation to Sanāʾi’s Divān. One major area of inquiry that remains untouched is the intersection between Sufi and pietistic themes and political ethics in Sanāʾi’s Hadiqeh. As I will demonstrate, an analysis of the instances in the Hadiqeh in which Sanāʾi provides politico-ethical as well as Sufi advice to Bahrāmshāh may provide us with a clue to first understand the interaction between Sufism and politics in the Hadiqeh, and second to figure out the connection between different sections of the work.

The Fourth Chapter of the Hadiqeh

The fourth chapter of the Hadiqeh showcases Sanāʾi’s political didacticism parallel to his skill in composing panegyric poetry. I will henceforth refer to this chapter as the politico-ethical section of the Hadiqeh. In this politico-ethical section, Sanāʾi describes the qualities of an ideal ruler, and illustrates each quality by means of anecdotes featuring Persian kings—chiefly Khosrow Anushirvān and Mahmud of Ghazna—and caliphs, including ʿOmar and al-Maʾmun, as exemplars. In addition to the homiletic tone of the chapter and the use of anecdotal narratives, the themes discussed in this section are similar to those in medieval Persian mirrors for princes. Amidst these anecdotal narratives, Sanāʾi advises Bahrāmshāh to be a just and virtuous king. Despite the anecdotal and didactic nature of this chapter and its focus on political ethics, there is one main element that renders this section of the Hadiqeh different from other works that belong to the traditional genre of mirrors for princes, and that is Sanāʾi’s mystical take on the concept of brotherhood of kingship and religion.Footnote 48 In traditional mirrors for princes, the portrayal of a ruler as the vicegerent or, to be more precise, “the shadow of God on earth” (zell Allāh taʿālā fi al-arz) involves a syncretic overlap of worldly and religious authority. In the Hadiqeh, however, the true shadow of God is considered a “perfect man,” one who has experienced the Path and has achieved union with God.Footnote 49 This ideal ruler is the true manifestation of God, and God’s sovereignty over people can be realized through his rule.Footnote 50 This view of an ideal ruler can be confirmed by some passages cited in the fourth chapter of the Hadiqeh and some of Sanāʾi’s panegyrics in the Divān.Footnote 51

In the Hadiqeh, he counsels Bahrāmshāh to embark on a spiritual path by detaching himself from worldly desires and purifying his heart in multiple verses. For instance, similar to his later counterpart Rumi, Sanāʾi refers to heart as the house of God (Kaʿbeh)—and instructs the Ghaznavid ruler to cleanse it of lust, greed, jealousy, and other moral vices.Footnote 52

It is, therefore, Bahrāmshāh’s duty to surpass his forefather Mahmud, who had the title of ghāzi (a warrior of a holy war) due to his military campaigns against the non-Muslims in India. While Mahmud’s mission was to follow Prophet Mohammad’s footsteps by uprooting idol worship and spreading Islam, Bahrāmshāh should continue their path by cleansing his heart of immaterial idols, i.e. moral vices, which prevent one from witnessing the Truth. Sanāʾi, therefore, defines Bahrāmshāh’s mission as internal, coextensive with, and at a level deeper than the external mission of the Prophet and Mahmud.

In another excerpt, Sanāʾi advises Bahrāmshāh to reach a state “where Angel Gabriel becomes his subordinate” (chun shawad jabraʾil ādam-e tu). He urges the ruler to “decide to rise up to the highest level of the heavens” (rāy kon bar shodan be ʿelliyyin), “lean on the Glorious Throne” (takyeh bar masnad-e jalāli zan), “humiliate the Devil and the demons within people,” i.e. their carnal souls (past kon diw wa diw-e mardom rā), and “place the crown of kingship on his heart” after killing his [worldly] desires (tā hawā rā be zir-e pay nanihi / bar sar-e del kolāh-e Kay nanihi), in order to be God’s true vicegerent.Footnote 56 These lines, which remind us of the Prophet’s heavenly ascension (meʿrāj), suggest that the spiritual path to the Throne of God and the perfection of one’s heart is a prerequisite of being an ideal ruler. Aversion to worldly desires and renunciation is also encouraged in some of the anecdotes cited in the fourth chapter of the Hadiqeh. One anecdote, for instance, centers on an anonymous king who avoids being imprisoned in his bodily desires by killing a beautiful slave girl whom he found desirable. Immediately after lusting for the girl, the king throws her into the water where she then drowns. Sanāʾi concludes this cryptic narrative by having the king explain that lusting for the slave girl would detrimentally bog him down in “clay”—a metaphor for the body as the abode of worldly desires. “The king said, being preoccupied with his heart,Footnote 57 / I do not set my two feet in my clay.”Footnote 58

Such passages in the Hadiqeh imply that Sanāʾi’s Perfect Ruler may also be a Perfect Man, meaning he who has completed his self-renunciating and anti-materialist spiritual journey to God. Thus, in the Hadiqeh, we are not simply dealing with two separate types of advice—that is, political and Sufi advice—running parallel to each other. Rather, we are dealing with a synthesis of the two types of advice. Now, how does this synthesis happen and does it have any role in relating the major themes of the Hadiqeh? A glance at the foundations of ideal kingship may be revealing in this matter.

On the Foundations of Kingship: Justice and the Intellect

The blueprint of Sanāʾi’s political advice is provided at the beginning of the politico-ethical section of the fourth chapter. Describing the foundations of ideal kingship, the poet states:

The relationship between the intellect and justice is a pivotal theme in Sanāʾi’s political thought. The bulk of the content of the fourth chapter focuses on justice as one of the two foundations of kingship and the different manifestations of justice. Sanāʾi discusses two ways in which justice is manifested in a ruler’s conduct: first, the king’s treatment of his subjects in a fair manner, and his use of punitive power to punish those who do not obey his commands and oppress the vulnerable classes of society, chiefly the peasants; and second, moderation, which is manifested in the ruler’s ability to govern the scope of his generosity, wrath, and forgiveness.

Multiple verses of the politico-ethical section of the Hadiqeh focus on the first manifestation of justice—i.e. dealing with one’s subjects in fair manner. An example can be found in an anecdote which goes as follows: The Ghaznavid Sultān Mahmud sees an oppressed, poor, old woman near his hunting ground. Hearing the woman crying and asking to talk to him, the king goes forward and starts a conversation with her. She explains that she has a son and two daughters, whom she feeds by gleaning the farmers’ harvest (khusheh-chini). She also mentions that she was working for someone in a village for a month and she had received a basket full of grapes as her wage. On her way back home five men, who introduced themselves as royal guards, attacked and beat her, and took the basket from her. She therefore asked around to see where Mahmud’s hunting ground was so that she could meet him in person. Reminding the king that the prayers of the oppressed will be answered by God, she pleads for justice. Fearing the divine punishment for injustice in the afterlife, Mahmud asks his retinue to bring the five royal guards who harmed the woman and executes them in front of his army. He then grants one of his own gardens to the old woman in compensation for the harm his retinue inflicted upon her.Footnote 60 While granting a garden to the poor woman manifests Mahmud’s generosity and his protection of the weak, his strict punishment of his cruel subjects demonstrates his ability to simultaneously use his coercive power. Punishing the oppressor and rewarding the oppressed are two ways in which the first meaning of justice is manifested in the Hadiqeh, and multiple anecdotes in the fourth chapter illustrate this meaning.Footnote 61

The second manifestation of justice is moderation. Sanāʾi states: “The just king treads the middle [path] / Neither is he [too fierce] like a lion, nor is he cowardly.”Footnote 62 This particular manifestation of justice shows itself in qualities such as the ruler’s ability to overlook his subjects’ mistakes, as well as his capacity to overcome his wrath. Several anecdotal narratives illustrate this theme. For instance, in one anecdote the poet describes Khosrow Anushirvān’s patience and self-control as a manifestation of his justice. The story goes that Anushirvān’s chamberlain steals the king’s goblet. The king sees his subject’s misdeed, but pretends that he has not seen anything. Upon noticing that the goblet is missing, the royal treasurer starts searching for it, fearing that the king may hold him responsible. His fear and fury leads him to accuse innocent people of stealing the precious object and to punish them. Anushirvān asks the treasurer to quell his wrath and stop searching for the goblet, saying that the one who has stolen it will not return it and the one who knows who has stolen the goblet will not reveal the secret. One day, while passing a street, the king sees the chamberlain wearing a belt—most likely an expensive belt, based on the context of the story. He points to the belt and jokingly asks the chamberlain whether he has purchased it in exchange for the goblet. The chamberlain gives him a positive response. From this anecdote, Sanāʾi draws the conclusion that Anushirvān has the qualities of “forgiveness” (bakhshudan), “generosity” (bakhshidan), “bounty” (pāshidan), and “concealing [one’s misdeeds]” (pushidan), which are manifest in his decision to not punish the chamberlain and overlook his misdeed.Footnote 63

It is noteworthy that this manifestation of justice is based on the utilization of the intellect. Here we have the intellect as the second foundation of kingship coming into play. Sanāʾi explains his view of the intellect in the fifth chapter of the Hadiqeh, and discusses the intellect’s function as the foundation of moderation in the seventh chapter. Thus, the concept of moderation as a manifestation of justice is the link between the political chapter and chapters five and seven, which contain philosophical and spiritual content. A brief analysis of the fifth and the seventh chapters is in order; I will first explain the content of chapter seven since it is more relevant to the above discussion about moderation.

The seventh chapter, entitled “Love, the Description of the Soul and [Different] Levels of the Heart,” focuses on the idea of cultivating the soul to partake in a spiritual journey to God. In this chapter, the role that the intellect plays in tempering qualities such as wrath (khashm) and lust (shahwat) has been highlighted in multiple lines. For instance, Sanāʾi compares wrath and lust to a dog and a horse, respectively, and presents the intellect (kherad or ʿaql) as a taming agent.Footnote 64 Once one’s wrath and lust become moderate, they lose their harmful qualities and become beneficial:

While a tamed horse can be securely ridden to one’s desired destination, an untamed horse will surely unseat its rider by bucking. A moderate level of desire acts as a driving force like a horse. Similarly, a moderate level of wrath functions as defensive power, which guards one from harm like a dog does. In the politico-ethical section of the Hadiqeh, Sanāʾi mentions wrath and the intellect (kherad), and emphasizes the latter over the former: “Do not place your wrath upon your intellect / Do not degrade your intellect.”Footnote 67

On the Intellect

The concept of intellect, explained in the fifth chapter, is pivotal in the study of the unity of the Hadiqeh. On the one hand, it is a central concept in Sanāʾi’s political ethics, and thus it connects the political chapter of the work to the chapters with spiritual content. On the other hand, it provides Sanāʾi with a framework for his philosophical mysticism, which runs through multiple chapters of his work. In most cases throughout the fifth chapter, Sanāʾi uses the word ʿaql without specifying to which intellect—i.e. “partial or human intellect” (ʿaql-e Jozʾi) or “Cosmic Intellect” (ʿaql-e kolli)—he is referring. This ambivalence allows the poet to use the word ʿaql in a more nuanced way, thus implying a connection between the human intellect and the Cosmic Intellect. Prior to Sanāʾi’s time, this connection (ettesāl) was discussed by Muslim Neoplatonists such as al-Fārābi (d. 950 CE) and Ibn Sinā (d. 1037 CE) as a way to access intuitive or inspired knowledge, a superior form of knowledge which is different from empirical knowledge. The connection happens as a result of a proper training of the human intellectual faculties, mainly the imaginative and estimative faculties.Footnote 68 Despite his rejection of Avicennean philosophy, Mohammad al-Ghazālī (d. 1111 CE) integrated many Avicennean teachings, including the idea of the connection between the intellects, into “inner science” (ʿelm-e bāten) or mysticism.Footnote 69 Many Islamic philosophical and mystical writings describe the human spiritual journey to God using the description of upward movement of Neoplatonic hypostases, often compared to the Prophet’s meʿrāj in mystical works. In this upward movement, the human soul moves from the lowest Neoplatonic hypostasis (i.e. Matter) to the Cosmic soul, then to the Cosmic Intellect, and finally to the One (i.e. God).Footnote 70 What facilitates this spiritual ascension is the connection between human intellect and a supreme intellect, sometimes identified as the Cosmic Intellect and sometimes identified as the Active Intellect (ʿaql-e faʿāl). As a result of the parallelism between the Neoplatonic idea of reversion, the Path towards God, and the Prophet’s heavenly ascension, the Active Intellect is often depicted as a guide-like figure—or at times Angel Gabriel—who guides the human soul through its journey to God.Footnote 71

A detailed analysis of Sanāʾi’s description of the intellect in the fifth chapter, in light of Islamic cosmology and epistemology in general, and Avicennean tradition in particular, is beyond the scope of this study. Suffice it to say that this chapter focuses on the description of different intellects, and their role in human spiritual journey. Similar to his predecessors, Sanāʾi identifies the connection between the human intellect and the Cosmic Intellect as the passageway towards true knowledge. He discusses two functions for the human intellect: first, managing the mundane affairs of daily life and being concerned with rank, positions, and financial profit; and second, discernment.Footnote 72 Due to this second function, Sanāʾi does not view the human intellect in an entirely negative light. Referring to the latter function of the human intellect, he sees it as an inborn faculty which protects human beings:

According to a popular belief, snakes were under a spell to guard treasures. They were believed to coil up on top of treasures and prevent them from being opened. Any attempt to open or take a particular treasure would cause its guardian snake to attack the person who intended to access the treasure. Here Sanāʾī compares the relationship between a person and their intellect to that of a treasure and its guardian snake. Although a snake is a venomous creature, its presence around treasure is necessary for its protection. Similarly, the human intellect—despite its main concern with one’s material benefit—is the best protector for human beings. By providing a person with the ability to distinguish good and evil, the human intellect assists one in avoiding the evil.

The goal, however, as Sanāʾi explains after the above verses, is to surpass the human intellect, and reach a celestial intellect that is purely good and the locus of true knowledge.

The main point of chapter five is, therefore, not the human intellect, but a superior intellect. To interpret the word ʿaql as the human intellect would be similar to reaching for the quiver in vain and using the arrows while missing the target. Here, the hierarchy of Neoplatonic hypostasis, that is, Matter (corporeal body), Soul, and the Intellect, and the mention of “the superior Intellect,” serve as clues that point the audience-reader to the Cosmic Intellect, the first creation of God, who can lead the human soul to the unseen world. This ʿaql is described in the opening verses of the fifth chapter as follows:

Here we are dealing with a being whose creation took place in primordial eternity. It is the cause for the creation of all beings (sabab-e har che bud wa hast wa bāshad ust); it organizes the affairs of the world, whether related to knowledge or practice; and more significantly, [divine] commands depend on the being’s existence (ham hameh amr basteh dar hastash). In other words, divine commands are conveyed through the existence of this ʿaql. The description of the ʿaql as a primordial creation emerging from the court of primordial eternity (bārgāh-e azal) indicates that the lord of the court is a primordial being, i.e. God. This information, coupled with the hadis “The first thing that God created is the Intellect” (awwal mā khalaqa Allāh taʿālā al-ʿaql) cited at the beginning of the chapter, points to the first creation of God, the Cosmic Intellect. Continuing the depiction of the Cosmic Intellect, Sanāʾi describes it as “the concealer and revealer of the unseen” (ghayb rā … gāh pushideh gah sarih-nomāy), thus pointing to the relationship between ʿaql and the unseen world, and corroborating his point about surpassing the human intellect and joining the Cosmic Intellect. The goal is, therefore, to know the secrets of the unseen through the Cosmic Intellect.Footnote 76

So far, every part of Sanāʾi’s town, while being unique, seems to have a function within the town’s entire structure. The political, the ethical, and the philosophical contents are interconnected. Each part seems to be clear, sound, and well-integrated into the overall message of the book, that is, spiritual perfection. The didactic framework allows the text to speak to a wide range of audiences. The king is instructed to be just and moderate, and in order to do so he needs to rely on his intellect and train it in a way that it connects to the Cosmic Intellect. The broader audiences of the extended version, i.e. Beryāngar, and possibly the people to whom he preached in Baghdad, as well as any seeker of Truth who is the listener-reader of the Hadiqeh, also need to follow the path of moderation by facilitating the connection of their intellect to the Cosmic Intellect. The theme of the connection between the two intellects links the above-discussed chapters and a series of other chapters, namely chapters six, seven, and eight, which are on knowledge (ʿelm), love (ʿeshq), and the Cosmic Soul (nafs-e kolli), respectively.

On Knowledge, the Cosmic Soul, Love, and Union

In the chapter on knowledge, Sanāʾi makes a distinction between two types of knowledge. Parallel to the distinction between the human intellect and Cosmic Intellect, there is a distinction between knowledge obtained through study and knowledge that is grasped intuitively. Sanāʾi places the latter above the former, and states that the former leads to the latter:

The first line describes the function of knowledge as a means for leading one to God. This knowledge should be empirical and pragmatic, since in the next line Sanāʾī advises his audience to put it into practice after learning it. The second hemistich of the second line can be interpreted in two ways. First, if it is interpreted as analogous to the first, it would seem that Sanāʾī is encouraging his listener-readers to first put into action whatever they have already learned, and then to learn further for the sake of acquiring skills to put into practice again; second, the words “digar” and “ʿelm” can be read together, in which case they would mean “another knowledge.” In this case, the second hemistich can refer to “another type of knowledge,” which could be a reference to intuitive knowledge that is realized as a result of the connection with the Cosmic Intellect. Furthermore, the word “kār,” though often translated as “action” or “work,” is occasionally used as a reference to whatever an author has said before. Therefore, one can argue that the word is a reference to what was said in the first line. In this case, the second line can be interpreted as follows: “Place into action what you have learned; After that, acquire a different type of knowledge, that is, the intuitive knowledge, for the purpose we had talked about, namely ascending to God with the help of the Cosmic Intellect.”

Other verses in the Hadiqeh point to Sanāʾi’s belief in a rather non-material type of knowledge that cannot be studied. For instance, Sanāʾi states: “The world of knowledge is a wondrous world / It is not from the territory of writing and [it does not fit] in speech.”Footnote 78

The account of how one’s access to intuitive knowledge comes about is provided in the Sayr al-ʿebād. The narrative of this work revolves around a meeting between Sanāʾi’s intellect and the Active Intellect, which leads the poet to embark on a spiritual journey with the guidance of the Active Intellect. A similar narrative can be found in the beginning of the Hadiqeh’s eighth chapter, which discusses the Cosmic Soul, particularly its role in connecting humanity to God. In the opening verses of this chapter, Sanāʾī narrates the story of his spiritual meeting with the Cosmic Soul, which appears like the dawn and invites the poet to start a journey with his guidance.Footnote 79 The connection in the Hadiqeh, therefore, happens between Sanāʾī’s soul and the Cosmic Soul—which is the link between the material world and the Cosmic Intellect. These verses not only relate Sanāʾi’s discussion of knowledge in chapter six—which itself is related to his discussion of the intellect in chapter five—to chapter eight (on the Cosmic Soul), but also sets the tone for chapter seven, which discusses themes pertinent to the spiritual path, including divine love. Before discussing this chapter, however, we should add that the noted verses bring to mind a section in the chapter on the intellect in which Sanāʾi provides his audience with an itinerary of the human soul’s ascent to God. In this section, Sanāʾi describes the Cosmic Soul as an intermediate agent between the human mind (hush) and the Platonic forms (surat), the locus of which is the Cosmic Intellect.Footnote 80 The human rational soul first connects to the Cosmic Soul. The Cosmic Soul as an intermediate agent connects the human rational soul or intellect to the Cosmic Intellect. This would then drive the human soul to God:

The idea is to surpass the Cosmic Intellect and meet God directly. A one-on-one meeting between God and His true servants, experiencing divine love and intimacy, and achieving union with God are common themes in Sufi literature. Authors such as Shaqiq Balkhi (d. 810 CE), Khwājeh ʿAbdollāh Ansāri (d. 1088 CE), Mohammad al-Ghazāli, and his brother Ahmad al-Ghazāli (d. 1123 or 1126 CE) present love as the culmination of human spiritual journey towards the Truth.Footnote 82 In the works of philosophers, such as Ibn Sinā, true love is defined as one’s love for the absolute source of love—i.e. God—and experiencing it takes place after knowledge of that absolute source.Footnote 83 Similarly, Sanāʾi places love above knowledge, even the knowledge of Platonic forms accessed through the connection with the Cosmic Intellect, and thus attests to the superiority of love over the Cosmic Intellect in the seventh chapter, where he states:

The seventh chapter of the Hadiqeh, which centers on love and the heart as the locus of love, is replete with verses that assert the superiority of the heart over the Cosmic Intellect and human intellect, as well as the superiority of love over knowledge. Through an allusion to the story of Adam’s descent to earth, Sanāʾi presents love as a divine favor received by Adam after he was already endowed with divine knowledge.Footnote 85 Thus, chapter seven is related to the discussions of the Intellect and knowledge in chapters five and six, respectively. It is also related to chapter eight’s preoccupation with the Cosmic Soul since Sanāʾi subordinates them here to love and the heart.Footnote 86

The superiority of the heart over the [Cosmic] Intellect and the experience of divine love are further elaborated through the discussions of “training the heart” (tarbiyat al-qalb) and treading the Path (tariqeh) in chapter seven.Footnote 87 Chapter seven is the climax of Sanāʾi’s didactic mysticism in his work. On the one hand, the chapter is related to the previously cited verses in chapter four, where Sanāʾi counsels Bahrāmshāh to purify his heart and ascend to the Throne of God by defeating his carnal soul and by placing the royal crown on his heart; this would further corroborate our assertion that Sanāʾi’s perfect ruler is also a Perfect Man and therefore, in the Hadiqeh, we are dealing with the merger of Sufi and political didacticism which is manifested in the portrayal of an ideal ruler. On the other hand, chapter seven can be related to the first chapter of the Hadiqeh—that is, the chapter on “union” or “unity” (towhid). While every Islamic medieval manual conventionally starts with the praise of God and His unity, Sanāʾi uses the word “towhid” also in its second meaning—that is, union with God. Much of the material cited in chapter one concerns the Path of Unity, as well as the qualities and deeds that can either impede or assist the seeker of truth in his quest. Some of the topics discussed in this chapter include “the purity [of heart] and intention” (as-safā va’l-ekhlās), “negligence of full trust in God” (al-ghaflah ʿan al-tawakkol), “striving [on the Path]” (al-mojāhedah), “reverence” (al-khoshuʿ), “praying” (ad-doʿāʾ), “contentment and submission” (ar-rezāʾ va’t-taslim). Additionally, the chapter emphasizes that one’s guidance through the Path is upon God and one can never tread the Path on one’s own. This is why the Intellect acts as a mediator between humanity and God.Footnote 88 Finally, the role of ʿaql as a guide is highlighted throughout the chapter. For instance:

Or: “Though the ear of the head hears countless [voices] / The ear of the [Cosmic] Intellect hears messages of ‘union’ (or: from one [source]).”Footnote 90 This being said, Sanāʾi highlights the limit of the Cosmic Intellect’s guiding capacity. For instance, he states: “The [Cosmic] Intellect is a guide, but only up until His gate / His effulgence will take you to His Presence.”Footnote 91 The verse is reminiscent of the episode of the Prophet’s Heavenly Ascension, during which he parted from Angel Gabriel at the Lote Tree of the Utmost Boundary due to Gabriel’s inability to pass that point. This once again suggests that the union between human and God and the direct experience of divine love happens after the human surpasses the Cosmic Intellect.

In sum, while the political content of the Hadiqeh and Sanāʾi’s description of the connection between the human intellect and the Cosmic Intellect provides his audiences with a blueprint for the path of spiritual perfection, the chapters and themes discussed in this section of the present study clarify the details of the spiritual path. The goal is union and the experience of divine love; the true guide is the Cosmic Intellect, and prior to that the Cosmic Soul; and there are steps that need to be taken to facilitate this upward movement. We are now left with the second, third, and ninth chapters of the work, chapters which revolve around two interrelated themes: first, the ephemerality of the material world and the necessity of asceticism and piety, and second, the sources of guidance—that is, the Qurʾān, and the Prophet and other great figures of the religion.

Piety and Guidance in This World

Chapter nine is particularly relevant to the previously examined chapters. Sanāʾi discusses constellations, planetary movements, and the change of seasons to highlight the ephemerality and unreliability of the world and therefore its lack of value. For instance, he states:

Through these verses, Sanāʾi sets the tone for the chapter, which emphasizes the importance of renunciation and religious piety. For instance, he states:

Sanāʾi continues by inviting his audience to go up to the “world of the [Cosmic] Intellect from [the world of] greed” (dar jahān-e kherad barāy az āz), and deems it necessary to go beyond multiplicity as a feature of the material world in order to reach “the Court of the One” (bārgāh-e ahad).Footnote 95

The rest of the chapter includes multiple series of Sufi advice in which renunciation, the ephemerality of the material world, and its association with suffering and evil are highlighted. This links the ninth chapter to the previously discussed chapters, which explain the journey of the human soul towards God. The role of the Cosmic Intellect, to which the human intellect is connected, is once again highlighted in this chapter, and this further strengthens the link between the ninth chapter and the rest of the Hadiqeh.

Chapters two and three of the Hadiqeh in praise of the Qurʾān and the greats of the religion, respectively, strengthen the narrative structure of the work in two ways. On the one hand, by praising the Qurʾān as the word of God, as well as the veneration of the Prophet and other religious figures, after chapter one’s treatment of towhid, Sanāʾi follows the conventions of writing in the medieval period. Most manuals written in this period start with the praise of God and His unity, occasionally the praise of His words, and then the praise of the greats of religion. On the other hand, the themes discussed in the two chapters are in harmony with the main message of the work. In the third chapter, Sanāʾi praises the Prophet, the Rightly Guided Caliphs, Hasan and Hosayn, Abu Hanifeh, the founder of the Hanafite school of law, and Mohammad b. Edris al-Shāfeʿī, the founder of the Shāfiʿite school. The chapter consists of a series of panegyrics describing the virtues of each of these individuals as well as brief accounts of their leadership and death. Each figure is praised for a particular moral characteristic, such as justice, knowledge, patience, or generosity. For instance, ʿOmar is praised for his justice, while ʿAli is praised for his knowledge, specifically his intellect and access to intuitive knowledge. Many of these moral characteristics are similar to the characteristics of an ideal ruler as described in the fourth chapter of the Hadiqeh. Thus, each of these religious figures serves as an exemplar in his life, rule, and death for the Muslim community in general, and for Sanāʾi’s royal patron, Bahrāmshāh, in particular. If we take into account the fact that Sanāʾi considered the connection of the human intellect with the Cosmic Intellect as a source for tempering moral vices, the depiction of these religious figures as virtuous individuals would imply their contact with the Cosmic Intellect. In the case of ʿAli, this is explicitly mentioned.Footnote 96 The chapter ends with Sanāʾi’s critique of those who are trapped in their prejudiced Islamic orthodoxy. For instance, the Shāfiʿite–Hanafite divide is construed simply as contrary to the verdict of ʿaql.Footnote 97

The connection between the chapter on the Qurʾān (i.e. the second chapter) and the rest of the Hadiqeh lies in two factors: first, the relationship between the Intellect and the word of God, since the Intellect’s words are harmonious with what is said in the Qurʾān and both have a guiding capacity;Footnote 98 and second, a parallelism between the esoteric and exoteric, or the terrestrial and celestial, that runs throughout the work as a whole. For instance, Sanāʾi states:

Here, the Qurʾān is described as a multi-layered text, which is in harmony with Sanāʾi’s description of some of the key concepts in his Hadiqeh. Both intellect and soul have a human and a celestial level. Similarly, knowledge is divided into acquired and intuitive knowledge. Finally, Justice has multiple definitions and manifestations. Perhaps when Sanāʾi refers to the Hadiqeh as the Persian Qurʾān (Qurʾān-e Pārsi) in the epilogue of his book, he is not only referring to the function of the Hadiqeh as a book of guidance, but is also highlighting the multi-layered nature of the work.Footnote 100 This multi-layeredness is what facilitates the synthesis of different intellectual currents such as political ethics, philosophy, and mysticism. Similar to the Qurʾān, the Hadiqeh is, therefore, open to interpretation.

Conclusion

This study was an attempt to provide one possible reading of the extended version of the Hadiqeh by following the connection between the major themes discussed in its chapters. I have argued that the unity of Sanāʾi’s work should not be understood based on a “logical” sequence of discussions that would create a linear narrative. This method has already been applied by de Bruijn, and the result was a sharp distinction between the Fakhrināmeh and the vulgate Hadiqeh in terms of their unity. However, at the core of the Hadiqeh, there is a thematic unity that strings its chapters together, regardless of its multiple recensions and the different arrangement of its sections. If we consider the Hadiqeh as a necklace made of pearls that are strung together through the theme of spiritual perfection, the middle pearl (vāsetat al-ʿeqd), which is often bigger and creates texture and harmony within the necklace, is perhaps the concept of intellect through which Sanāʾi ties different subject areas to one another. Regardless of how other pearls are ordered in this necklace, the string and the middle pearl are always the same, and the necklace is thereby always a unified whole.

As suggested, the merger of Sufi and politico-ethical themes in Sanāʾi’s didacticism, as reflected in the Hadiqeh’s introduction, epilogue, and, most importantly, in its fourth chapter, can serve as a starting point in identifying the core message of the work. A close look at the foundations of ideal rulership demonstrates that Sanāʾī identifies ʿaql as the source not only for justice, which is discussed in the fourth chapter, but also for guidance through the spiritual path. The details of the spiritual path, including renunciation of the transient material world, the human connection to the Cosmic Soul and then the Cosmic Intellect, access to divine knowledge, ascendance to God, and experiencing divine love and union with Him, are described in other chapters of the work. In addition to the link between these central themes, Sanāʾi’s focus on the multi-layeredness of the concepts explored in his work is manifested throughout most of the chapters of the Hadiqeh, and thus further strengthens the unity of the work.

The methodology applied in the present study aimed to suggest a way to surpass the barriers created by the complicated textual history of the Hadiqeh, and to open the door for further scholarly research on the content of the wok. Our understanding of the unity of the vulgate Hadiqeh would perhaps benefit from further examination of individual chapters of the work, the role of exhortations as a unifying factor within the Hadiqeh, the oral and textual aspects of the work, and the question of audiences. Furthermore, a more thorough analysis of the philosophical and cosmological aspects of the Hadiqeh and Sanāʾi’s other works may shed light on his multifaceted approach to the content of the sources from which he draws his influences, as well as the poet’s place in the cultural milieu of his time.

Appendix 1. Quoted Verses in Persian