The oldest Hexapoda originated sometime in the Silurian, to take advantage of early land plants. The oldest known fossil hexapods are earliest Devonian from Scotland (Ross et al. Reference Ross, Edgecombe, Legg and Clark2016), but the oldest fossils of pterygote insects come from the mid-Carboniferous; however at these times the group was well differentiated (Grimaldi & Engel Reference Grimaldi and Engel2005), with a number of extinct lineages, and also representatives of the oldest extant pterygote lineages, present (Nel et al. Reference Nel, Roques, Nel, Prokin, Bourgoin, Prokop, Szwedo, Azar, Desutter-Grandcolas, Wappler, Garrouste, Coty, Huang, Engel and Kirejtshuk2013).

The bugs, order Hemiptera Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1758, belong to one of the most ancient lineages within the Eumetabola (Paraneoptera+Holometabola), and can be dated back to 330 Ma (Nel et al. Reference Nel, Roques, Nel, Prokin, Bourgoin, Prokop, Szwedo, Azar, Desutter-Grandcolas, Wappler, Garrouste, Coty, Huang, Engel and Kirejtshuk2013; Song & Liang Reference Song and Liang2013). The Hemiptera has long been recognised as a monophyletic group (Hennig Reference Hennig1969; Rohdendorf & Rasnitsyn Reference Rohdendorf and Rasnitsyn1980; Ax Reference Ax1999; Beutel et al. Reference Beutel, Friedrich, Ge and Yang2014; Gullan & Cranston Reference Gullan and Cranston2014). The most striking feature of the group is the presence of a segmented rostrum with a multisegmented sheet-like labium covering the mandibular and maxillary stylets; these stylets, being the mandibles and maxillary laciniae, are modified and formed into a concentric bundle, the mandibular enclosing the maxillary ones, both forming the food and salivary channels. The maxillary and labial palpi are always absent (Weber Reference Wang, Szwedo and Zhang1930; Hennig Reference Hennig1969, Reference Hennig1981; Emeljanov Reference Emeljanov2002). Such a unified mouthpart allows the Hemiptera to eat a variety of foods. Feeding habits of the Hemiptera range from phytophagy to predation, including ectoparasitism and hematophagy; many of them are pest species of cultivated crops, vectors of plant pathogens and diseases and some are vectors of human diseases (Grimaldi & Engel Reference Grimaldi and Engel2005; Forero Reference Forero2008; Beutel et al. Reference Beutel, Friedrich, Ge and Yang2014; Gullan & Cranston Reference Gullan and Cranston2014).

The Hemiptera is an unbelievably diversified and successive group, inhabiting all terrestrial and some marine habitats. Being one of the Big Five insect orders, after Coleoptera, Diptera, Hymenoptera and Lepidoptera (Schuh & Slater Reference Schuh and Slater1995; Grimaldi & Engel Reference Grimaldi and Engel2005; Cameron et al. Reference Cameron, Beckenbach, Dowton and Whiting2006; Gullan & Cranston Reference Gullan and Cranston2014), it is the most diversified group of non-endopterygote insects, with diversity maybe surpassed only by the Diptera (Kristensen Reference Kristensen, Naumann, Carne, Lawrence, Nielsen, Spradbery, Taylor, Whitten and Littlejohn1991).

The Hemiptera contains 302 extant and extinct families known – the biggest number of families among any insects, with approximately 104,000 described extinct and recent species (Beutel et al. Reference Beutel, Friedrich, Ge and Yang2014; EDNA 2015; PaleoBioDB 2017). In comparison, all the other insect orders, excluding the Big Five, cover over 100,000 species (Table 1). It should be pointed out, however, that the species richness of the Hemiptera seems to be underestimated. One of the biggest groups, the Cicadomorpha, has about 33,500 known species, but 90 % of the estimated global diversity of this suborder remains unknown (Hodkinson & Casson Reference Hodkinson and Casson1991; Dietrich & Wallner Reference Dietrich, Wallner, Hoch, Asche, Hömberg and Kessling2002; Dietrich Reference Dietrich2005, Reference Dietrich, Chang, Lee and Shih2013).

Table 1 Diversity of extinct and extant insects. Data compiled from Nicholson et al. Reference Nicholson, Mayhew and Ross2015; EDNA 2015; PaleoBioDB 2017, updated.

1. Systematics and classification

Hemipterans constitute a group with a long and complicated evolutionary and taxonomic history. The history of the Hemiptera classification started with Systema Naturae 1st edition (Linnaeus Reference Linnaeus1735), but the 10th edition (Linnaeus Reference Linnaeus1758) is recognised as valid for zoological nomenclature purposes. Fossil Hemiptera studies started almost in parallel, with a paper by Bloch (Reference Bloch1776). Since its beginning, the classification of the group produced troubles and taxonomic problems. Linnaeus (Reference Linnaeus1758), on page 343 of the 10th edition of Systema Naturae, placed the genera Cicada, Notonecta, Nepa, Cimex, Aphis, Chermes, Coccus and Thrips in the Hemiptera. Such recognition resulted in a paraphyletic group. Thysanoptera, together with ‘Psocodea' (paraphyletic assemblage; see Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Yoshizawa and Smith2004; Yoshizawa & Johnson Reference Yao, Cai, Xu, Shih, Engel, Zheng, Zhao and Ren2006), are regarded as the closest relatives of Hemiptera (Rasnitsyn & Quicke Reference Rasnitsyn and Quicke2002; Grimaldi & Engel Reference Grimaldi and Engel2005; Beutel et al. Reference Beutel, Friedrich, Ge and Yang2014; Gullan & Cranston Reference Gullan and Cranston2014). Linnaeus (Reference Linnaeus1735, Reference Linnaeus1758) built his opinion on the Hemiptera on the structure of the wings, but he noticed the differentiated structure of the mouthparts, dividing hemipterans into insects with “rostrum inflexum” (true bugs, cicadas and their allies) and insects with “rostrum pectorale” (coccids and some other Sternorrhyncha).

The 19th and the beginning of the 20th Century resulted in prolific works on the classification, divisions and subdivision of various taxonomic units, but also the first studies on relationships (Brożek et al. Reference Brożek, Szwedo, Gaj and Pilarczyk2003). During the 19th Century, several workers on the Recent Hemiptera were also dealing with fossils (Handlirsch Reference Handlirsch1906–1908; Becker-Migdisova Reference Becker-Migdisova and Rodendorf1962b; Metcalf & Wade Reference Metcalf and Wade1966; Szwedo et al. Reference Szwedo, Bourgoin and Lefebvre2004; Heie & Wegierek Reference Heie and Wegierek2011). The next steps in the research on the classification and relationships of the Hemiptera, and within the group, were undertaken in the 1950s and ‘60s; however, most of them regarded the Heteroptera and ‘Homoptera' as independent separate insect orders. At this time, several ‘∼morpha' units were established among both Recent and fossil hemipteran groups (Becker-Migdisova Reference Becker-Migdisova and Rodendorf1962b; Štys & Kerzhner Reference Štys and Kerzhner1975). Major debates on classification started again with ‘molecular revolutions'. As result the ‘Homoptera' disappeared as an independent order and the Heteroptera became one of the suborders within the Hemiptera. The question of monophyly of the ‘Auchenorrhyncha' (i.e. Fulgoromorpha+Cicadomorpha) is still under dispute (Bourgoin & Campbell Reference Bourgoin, Campbell and Holzinger2002; Szwedo Reference Szwedo and Holzinger2002; Forero Reference Forero2008; Cryan & Urban Reference Cryan and Urban2012; Beutel et al. Reference Beutel, Friedrich, Ge and Yang2014). The monophyly of Sternorrhyncha was also questioned and discussed (Börner Reference Börner1904; Schlee Reference Schlee1969a, Reference Schleeb, Reference Schleec; Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov2000a, 2005). The accumulation of new data and interpretations resulted in the present state of knowledge, with six suborders within the Hemiptera; i.e., Paleorrhyncha, Sternorrhyncha, Fulgoromorpha, Cicadomorpha, Coleorrhyncha and Heteroptera (Szwedo et al. Reference Szwedo, Bourgoin and Lefebvre2004). The number of Hemiptera families, their content and the relationships within and between higher taxa are still the subject of discussions after 250 years of study.

The list of extant and extinct families and classification of the Hemiptera is given below. The classification is derived from the proposals of Burckhardt & Ouvrard (Reference Burckhardt and Ouvrard2012), Drohojowska (Reference Drohojowska2015), Grazia et al. (Reference Grazia, Shuch and Wheeler2008), Heie & Wegierek (Reference Heie and Wegierek2011), Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2014), Hodgson & Hardy (Reference Hodgson and Hardy2013), Schuch & Slater (Reference Schuh and Slater1995), Schuch et al. (Reference Schuh, Weirauch and Wheeler2009), Sweet (Reference Sweet2006) and Szwedo et al. (Reference Szwedo, Bourgoin and Lefebvre2004). The stratigraphic ranks are given partly after Nicholson et al. Reference Nicholson, Mayhew and Ross2015 and PaleoBioDB (2017), checked, corrected and updated; doubtful data are placed in square brackets; chronostratigraphic units are given using the the International Chronostratigraphic Chart, v. 2017/02 (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Finney, Gibbard and Fan2013, updated).

Order Hemiptera Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1758

Protoprosbolidae† Laurentiaux, Reference Laurentiaux1952 – Carboniferous (Bashkirian)

Clade Hemelytrata Fallén, Reference Fallén1829

= Euhemiptera Zrzavý, Reference Zherikhin, Rasnitsyn and Quicke1990

Aviorrhynchidae† Nel, Bourgoin, Engel & Szwedo, Reference Nel, Roques, Nel, Prokin, Bourgoin, Prokop, Szwedo, Azar, Desutter-Grandcolas, Wappler, Garrouste, Coty, Huang, Engel and Kirejtshuk2013 (in Nel et al. Reference Nel, Roques, Nel, Prokin, Bourgoin, Prokop, Szwedo, Azar, Desutter-Grandcolas, Wappler, Garrouste, Coty, Huang, Engel and Kirejtshuk2013) – Carboniferous (Moscovian)

Suborder Cicadomorpha Evans, Reference Evans1946

Infraorder Prosbolopsemorpha† infraord. nov.

Remark. This group is proposed to embrace Permian and Triassic forms of specialized Cicadomorpha, with long rostrum, and tegmina with dense branching on membrane, often with dense net of irregular transverse veinlets; claval veins fused reaching margin as a common stem.

Superfamily Prosbolopseoidea† Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1946

Prosbolopseidae† Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1946; Permian (Kungurian–Capitanian)

Superfamily Pereborioidea† Zalessky, Reference Yoshizawa and Johnson1930

Curvicubitidae† Hong, Reference Hong1984; Triassic (Anisian–Carnian)

Ignotalidae† Riek, Reference Riek1973; Permian (Wuchapingian)–Triassic (Induan)

Pereboriidae† Zalessky, Reference Yao, Cai, Xu, Shih, Engel, Zheng, Zhao and Ren1930; Permian (Artinskian)–Triassic (Ladinian)

Infraorder Prosbolomorpha† Popov, Reference Popov, Rohdendorf and Rasnitsyn1980

Superfamily Dysmorphoptiloidea† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906

Dysmorphoptilidae† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906; Permian (Kungurian)-Jurassic (Kimmeridgian)

Eoscarterellidae† Evans, Reference Evans1956; Permian (Changhsingian)–Triassic (Carnian)

Magnacicadiidae† Hong & Chen, Reference Hong and Chen1981; Triassic (Anisian)

Superfamily Palaeontinoidea† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906

Dunstaniidae† Tillyard, Reference Targioni-Tozetti1916; Permian (Capitanian)–Jurassic (Callovian)

Mesogereonidae† Tillyard, Reference Tillyard1921; Triassic (Carnian)

Palaeontinidae† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906; Triassic (Carnian)–Cretaceous (Aptian)

Superfamily Prosboloidea† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906

Prosbolidae† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906; Permian (Artinskian)–Jurassic (Callovian)

Maguviopseidae† Shcherbakov, Reference Shcherbakov2011; Triassic (Carnian)

Clade Clypeata Qadri, Reference Qadri1967

Superfamily Cercopoidea Westwood, Reference Wegierek1838

Aphrophoridae Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843; [Cretaceous (Cenomanian)] Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Cercopidae Westwood, Reference Wegierek1838; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Cercopionidae† Hamilton, Reference Hamilton and Grimaldi1990; Cretaceous (Aptian)

Clastopteridae Dohrn, Reference Dohrn1859; [Eocene (Priabonian)] Miocene (Burdigalian)–Holocene

Epipygidae Hamilton, Reference Hamilton2002; [Eocene (Lutetian)]–Holocene

Procercopidae† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906 – Jurassic (Hettangian)–Cretaceous (Turonian)

Sinoalidae† Wang & Szwedo, Reference Wang, Szwedo, Zhang and Fang2012 in Wang et al. Reference Wang, Szwedo, Zhang and Fang2012; Jurassic (Callovian–Oxfordian)

Superfamily Cicadoidea Latreille, Reference Latreille1802

Cicadidae Latreille, Reference Latreille1802; Cretacous (Cenomanian)–Holocene

Tettigarctidae Distant, Reference Distant1905; Triassic (Rhaetian)–Holocene

Superfamily Hylicelloidea† Evans, Reference Evans1956

Chiliocyclidae† Evans, Reference Evans1956; Triassic (Carnian)

Hylicellidae† Evans, Reference Evans1956; [Permian (Wuchapingian)] Triassic (Ladinian)–Cretaceous (Aptian)

Mesojabloniidae† Storozhenko, Reference Storozhenko1992; Triassic (Carnian)

Superfamily Cicadelloidea Latreille, Reference Latreille1802 stat. resurr.

(= Jassoidea auct., partim)

Remark. The superfamily was proposed to distinguish several groups from the Cercopoidea (Evans Reference Evans1966). It was not universally accepted, and the superfamily Membracoidea was accepted to comprise leafhoppers (Cicadellidae) and treehoppers (Membracidae and related families). The resurrection of the superfamily is proposed to comprise fossil and Recent representatives of these hyperdiverse insects.

Archijassidae† Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1962a; Triassic (Carnian)-Jurassic (Tithonian)

Cicadellidae Latreille, Reference Latreille1802 s. l.; Cretaceous (Aptian)-Holocene

Superfamily Membracoidea Rafinesque, Reference Rafinesque1815 s. str.

Remark. This superfamily is treated in the strict sense, following Hamilton's (Reference Hamilton2012) hypothesis on neotenic origin of this lineage from ancestral forms close to or representing Cicadellidae.

Aetalionidae Spinola, Reference Spinola1850; Miocene (Burdigalian)–Holocene

Melizoderidae Deitz & Dietrich, Reference Deitz and Dietrich1993; Holocene

Membracidae Rafinesque, Reference Rafinesque1815; Miocene (Burdigalian)-Holocene

Ulopidae Le Peletier & Audinet-Serville, Reference Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau and Audinet-Serville1825; Holocene

Superfamily Myerslopioidea Evans, Reference Evans1957

Myerslopiidae Evans, Reference Evans1957; Cretaceous (Aptian)–Holocene

Suborder Fulgoromorpha Evans, Reference Evans1946

Superfamily Coleoscytoidea† Martynov, Reference Martynov1935

Coleoscytidae† Martynov, Reference Martynov1935; Permian (Roadian)

Superfamily Fulgoroidea Latreille, Reference Latreille1807

Acanaloniidae Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843; Holocene

Achilidae Stål, Reference Stål1866; Cretaceous (Aptian)–Holocene

Achilixiidae Muir, Reference Muir1923; Holocene

Caliscelidae Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843; Miocene (Burdigalian)–Holocene

Cixiidae Spinola, Reference Spinola1839; Cretaceous (Barremian)–Holocene

Delphacidae Leach, Reference Leach1815; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Derbidae Spinola, Reference Spinola1839; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Dictyopharidae Spinola, Reference Spinola1839; Cretaceous (Antonian)–Holocene

Eurybrachidae Stål, Reference Stål1862; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Flatidae Spinola, Reference Spinola1839; Paleocene (Thanetian)–Holocene

Fulgoridae Latreille, Reference Latreille1807; Eocene (Ypresian)-Holocene

Fulgoridiidae† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1939; Jurassic (Sinemurian-Oxfordian)

Gengidae Fennah, Reference Fennah1949; Holocene

Hypochthonellidae China & Fennah, Reference China and Fennah1952; Holocene

Issidae Spinola, Reference Spinola1839; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Kinnaridae Muir, Reference Muir1925; Miocene (Burdigalian)–Holocene

Lalacidae† Hamilton, Reference Hamilton and Grimaldi1990; Cretaceous (Barremian–Aptian)

Lophopidae Stål, Reference Stål1866; Paleocene (Thanetian)–Holocene

Meenoplidae Fieber, Reference Fieber1872; Holocene

Mimarachnidae† Shcherbakov, Reference Shcherbakov2007c; Cretaceous (Valanginian–Turonian)

Neazoniidae† Szwedo, Reference Szwedo2007; Cretaceous (Barremian–Albian)

Nogodinidae Melichar, Reference Melichar1898; Paleocene (Danian)–Holocene

Perforissidae† Shcherbakov, Reference Shcherbakov2007b; Cretaceous (Barremian–Santonian)

Qiyangiricaniidae† Szwedo, Wang & Zhang, Reference Szwedo, Wang and Zhang2011; Jurassic (Toarcian–Alenian)

Ricaniidae Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843; Paleocene (Danian)–Holocene

Tettigometridae Germar, Reference Germar1821; Holocene

Tropiduchidae Stål, Reference Stål1866; Cretaceous (Turonian)–Holocene

Weiwoboidae† Lin, Szwedo, Huang & Stroiński, Reference Lin, Szwedo, Huang and Stroinski2010; Eocene (Ypresian)

Superfamily Surijokocixioidea† Shcherbakov, Reference Shcherbakov2000b

Surijokocixiidae† Shcherbakov, Reference Shcherbakov2000b; Permian (Wordian)–Triassic (Carnian)

Clade Prosorrhyncha Sorensen, Campbell, Gill & Steffen-Campbell, Reference Sorensen, Campbell, Gill and Steffen–Campbell1995

Infraorder Ingruomorpha† infraord. nov.

Remark. The family Ingruidae appears to be one of the earliest branches of early Hemelytrata, separated in parallel to the Prosbolopseidae (Popov & Shcherbakov Reference Popov and Shcherbakov1991, 1996; Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov and Schaefer1996). Ingruidae are believed to be ancestral to Coleorrhyncha: Progonocimicidae, and through the scytinopteromorphan family Paraknightiidae to the Heteroptera.

Ingruidae† Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1960; Permian (Kungurian–Capitanian)

Infraorder Scytinopteromorpha† Martins-Neto, Gallego & Melchor, Reference Martins-Neto, Gallego and Melchor2003 stat. nov. [= Scytinopteromorpha Gallego, Martins-Neto & Carmona, 2001, nom. inform.]

Superfamily Scytinopteroidea† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906

Remark This unit is likely paraphyletic.

Granulidae† Hong, Reference Hong1980; Triassic (Ladinian)

Ipsviciidae† Tillyard, Reference Tillyard1919; [Permian (Roadian)]–Jurassic (Sinemurian) [Cretaceous (Aptian)]

Paraknightiidae† Evans, Reference Evans1950; Permian (Changhsingian)–Triassic (Carnian)

Saaloscytinidae† Brauckmann, Martins-Neto & Gallego, Reference Martins-Neto, Brauckmann, Gallego and Carmona2006 in Martins-Neto et al.; Triassic (Anisian–Carnian)

Scytinopteridae† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906; Permian (Kungurian)–Cretaceous (Aptian)

Serpentivenidae† Shcherbakov, Reference Shcherbakov1984; Triassic (Carnian)–Cretaceous (Berriasian)

Stenoviciidae† Evans, Reference Evans1956; Permian (Capitanian)–Triassic (Carnian)

Suborder Coleorrhyncha Myers & China, Reference Myers and China1929

Infraorder Progonocimicomorpha† Popov, Reference Popov, Rohdendorf and Rasnitsyn1980

Superfamily Progonocimicoidea† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906

Progonocimicidae† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906; Permian (Changhsingian)–Cretaceous (Aptian)

Infraorder Peloridiomorpha Popov, Reference Popov, Rohdendorf and Rasnitsyn1980

Superfamily Peloridioidea Breddin, Reference Breddin and Michaelsen1897

Hoploridiidae† Popov & Shcherbakov, Reference Popov and Shcherbakov1991; Cretaceous (Aptian)

Karabasiidae† Popov, Reference Popov1985; Jurassic (Sinemurian-Tithonian)

Peloridiidae Breddin, Reference Breddin and Michaelsen1897; Holocene

Clade Heteropterodea Zrzavý, Reference Zrzavý and Koteja1992

Suborder Heteroptera Latreille, Reference Latreille1810

Clade Euheteroptera Štys, Reference Štys1985

Infraorder Nepomorpha Popov, Reference Popov1968

Pterocimicidae† Popov, Dolling & Whalley, Reference Popov, Dolling and Whalley1994; Jurassic (Sinemurian)

Superfamily Nepoidea Latreille, Reference Latreille1802

Belostomatidae Leach, Reference Leach1815; Triassic (Carnian)–Holocene

Nepidae Latreille, Reference Latreille1802; Eocene (Priabonian)–Holocene

Superfamily Corixoidea Leach, Reference Leach1815

Corixidae Leach, Reference Leach1815; Triassic (Carnian)–Holocene

Shurabellidae† Popov, Reference Popov1971; [Triassic (Norian)] Jurassic (Hettangian–Oxfordian)

Superfamily Gelastocoroidea Kirkaldy, Reference Kirkaldy1897

Gelastocoridae Kirkaldy, Reference Kirkaldy1897; Cretaceous (Cenomanian)–Holocene

Ochteridae Kirkaldy, Reference Kirkaldy1906; Holocene

Superfamily Naucoroidea Leach, Reference Leach1815

Aphelocheiridae Fieber, Reference Fieber1851; Holocene

Leptaphelocheiridae† Polhemus, Reference Polhemus2000; Jurassic (Callovian)

Naucoridae Leach, Reference Leach1815; Triassic (Carnian)–Holocene

Potamocoridae Hungerford, Reference Hungerford1948; Holocene

Triassocoridae† Tillyard, Reference Tillyard1922; Triassic (Anisian-Norian)

Superfamily Notonectoidea Latreille, Reference Latreille1802

Notonectidae Latreille, Reference Latreille1802; Triassic (Carnian)-Holocene

Superfamily Pleoidea Fieber, Reference Fieber1851

Helotrephidae Esaki & China, Reference Esaki and China1927; Holocene

Mesotrephidae† Popov, Reference Popov1971; Cretaceous (Turonian)

Pleidae Fieber, Reference Fieber1851; Holocene

Scaphocoridae† Popov, Reference Popov1968; Jurassic (Oxfordian)

Clade Neoheteroptera Štys, Reference Štys1985

Infraorder Cimicomorpha Leston, Pendergrast & Southwood, Reference Leston, Pendergrast and Southwood1954

Superfamily Cimicoidea Latreille, Reference Latreille1802

Anthocoridae Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843; Cretaceous (Aptian)-Holocene

Cimicidae Latreille, Reference Latreille1802; [Cretaceous (Cenomanian)]–Holocene

Curaliidae Schuh, Weirauch, Henry & Halbert, Reference Schuh, Weirauch, Henry and Halbert2008; Holocene

Lasiochilidae Carayon, Reference Carayon1972; Holocene

Lyctocoridae Reuter, Reference Reuter1884; Holocene

Plokiophilidae China, Reference China1953; Holocene

Polyctenidae Westwood, Reference Westwood1874; Holocene

Torirostratidae† Yao, Cai, Shih & Engel, Reference Yao, Cai, Rieder and Ren2014 in Yao et al. Reference Yao, Cai, Rieder and Ren2014; Cretaceous (Aptian)

Velocipedidae Bergroth, Reference Bergroth1891; Holocene

Vetanthocoridae† Yao, Cai & Ren, Reference Yao, Cai and Ren2006b; Jurassic (Callovian)–Cretaceous (Aptian)

Superfamily Joppeicoidea Reuter, Reference Reuter1910

Joppeicidae Reuter, Reference Reuter1910; Holocene

Superfamily Miroidea Hahn, Reference Hahn1831

Microphysidae Dohrn, Reference Dohrn1859; Cretaceous (Santonian)–Holocene

Miridae Hahn, Reference Hahn1831; Jurassic (Callovian)–Holocene

Superfamily Nabidoidea Costa, Reference Costa1853

Medocostidae Štys, Reference Štys1967; Holocene

Nabidae Costa, Reference Costa1853; Jurassic (Callovian)-Holocene

Superfamily Reduvioidea Latreille, Reference Latreille1807

Ceresopseidae† Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1958; Jurassic (Sinemurian)

Pachynomidae Stål, Reference Stål1873; Holocene

Reduviidae sensu lato Latreille, Reference Latreille1807; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Superfamily Thaumastocoroidea Kirkaldy, Reference Kirkaldy1908

Thaumastocoridae Kirkaldy, Reference Kirkaldy1908; Cretaceous (Turonian)–Holocene

Superfamily Tingoidea Laporte, Reference Laporte1833

Ebboidae† Perrichot, Nel, Guilbert & Néraudeau, Reference Perrichot, Nel, Guilbert and Neraudeau2006; Cretaceous (Albian–Cenomanian)

Hispanocaderidae† Golub, Popov & Arillo, Reference Golub, Popov and Arillo2012; Cretaceous (Albian)

Ignotingidae† Zhang J., Golub, Popov & Shcherbakov, Reference Zhang, Sun and Zhang2005; Cretaceous (Barremian)

Tingidae Laporte, Reference Laporte1833; Cretaceous (Aptian)–Holocene

Vianaididae Kormilev, Reference Kormilev1955; Holocene

Infraorder Dipsocoromorpha Miyamoto, Reference Miyamoto1961

Superfamily Dipsocoroidea Dohrn, Reference Dohrn1859

Ceratocombidae Fieber, Reference Fieber1860; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Cuneocoridae† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch and Schröder1920; Jurassic (Toarcian)

Dipsocoridae Dohrn, Reference Dohrn1859; Cretaceous (Barremian)–Holocene

Hypsipterygidae Drake, Reference Drake1961; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Schizopteridae Reuter, Reference Reuter1891; Cretaceous (Barremian)–Holocene

Superfamily Stemmocryptoidea Štys, Reference Štys1983

Stemmocryptidae Štys, Reference Štys1983; Holocene

Superfamily Enicocephalomorpha Stichel, Reference Stichel1955

Aenictopecheidae Usinger, Reference Uhler1932; Holocene

Enicocephalidae Stål, Reference Stål1858; Cretaceous (Barremian)–Holocene

Infraorder Gerromorpha Popov, Reference Popov1971

Superfamily Gerroidea Leach, Reference Leach1815

Gerridae Leach, Reference Leach1815; Cretaceous (Albian)–Holocene

Hermatobatidae Coutière & Martin, Reference Coutière and Martin1901; Holocene

Superfamily Hebroidea Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843

Hebridae Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843; Miocene (Burdigalian)–Holocene

Superfamily Hydrometroidea Billberg, Reference Billberg1820

Hydrometridae Billberg, Reference Billberg1820; Cretaceous (Albian)–Holocene

Macroveliidae McKinstry, Reference McKinstry1942; Holocene

Superfamily Mesovelioidea Douglas & Scott, Reference Douglas and Scott1867

Madeoveliidae Poisson, Reference Poisson1959; Holocene

Mesoveliidae Douglas & Scott, Reference Douglas and Scott1867; Jurassic (Kimmeridgian)–Holocene

Paraphrynoveliidae Andersen, Reference Andersen1978; Holocene

Veliidae Brullé, Reference Brullé1836; [Cretaceous (Aptian)] Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Clade Panheteroptera Štys, Reference Štys1985

Infraorder Aradimorpha Verhoeff, Reference Vea and Grimaldi1893

Superfamily Aradoidea Brullé, Reference Brullé1836

Aradidae Brullé, Reference Brullé1836; Jurassic (Oxfordian)–Holocene

Kobdocoridae† Popov, Reference Popov1986; Cretaceous (Hauterivian)

Termitaphididae Myers, Reference Myers1924; Miocene (Burdigalian)–Holocene

Infraorder Leptopodomorpha Štys & Kerzhner, Reference Štys and Kerzhner1975

Superfamily Leptopodoidea Brullé, Reference Brullé1836

Leotichiidae China, Reference China1933; Holocene

Leptaphelocheiridae† Polhemus, 217; Jurassic (Callovian)

Leptopodidae Brullé, Reference Brullé1836; Cretaceous (Cenomanian)–Holocene

Omaniidae Cobben, Reference Cobben1970; Holocene

Palaeoleptidae† Poinar & Buckley, Reference Poinar2009; Cretaceous (Cenomanian)

Superfamily Saldoidea Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843

Aepophilidae Puton, Reference Puton1879; Holocene

Archegocimicidae† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906; Jurassic (Sinemurian)–Cretaceous (Aptian)

Saldidae Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843; Cretaceous (Barremian)–Holocene

Infraorder Pentatomomorpha Leston, Pendergrast & Southwood, Reference Leston, Pendergrast and Southwood1954

Dehiscensicoridae† Du, Yao, Ren & Zhang, Reference Du, Yao, Ren. and Zhang2017; Lower Cretaceous (Barremian–Aptian)

Superfamily Coreoidea Leach, Reference Leach1815

Alydidae Stål, Reference Stål1872; Jurassic (Oxfordian)–Holocene

Coreidae Leach, Reference Leach1815; [Triassic (Norian)] Jurassic (Callovian)–Holocene

Hyocephalidae Bergroth, Reference Bergroth1906; Holocene

Rhopalidae Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843; Jurassic (Callovian)–Holocene

Stenocephalidae Latreille, Reference Latreille1825; Holocene

Trisegmentatidae† Zhang, Sun & Zhang, Reference Zhang, Zhang, Hou and Ma1994; Miocene (Langhian)

Yuripopovinidae† Azar, Nel, Engel, Garrouste & Matocq, Reference Azar, Nel, Engel, Garrouste and Matocque2011; Cretaceous (Barremian)

Superfamily Idiostoloidea Scudder, Reference Scudder1962

Idiostolidae Scudder, Reference Scudder1962; Holocene

Superfamily Lygaeoidea Schilling, Reference Schilling1829

Berytidae Fieber, Reference Fieber1851; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Colobathristidae Stål, Reference Stål1865; Holocene

Lygaeidae Schilling, Reference Schilling1829; [Jurassic (Bajocian)] Eocene (Lutetian)-Holocene

Malcidae Stål, Reference Stål1865; Holocene

Meschiidae Malipatil, Reference Malipatil2014; Holocene

Pachymeridiidae† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906; [Triassic (Rhaetian)] Jurassic (Hettangian)–Cretaceous (Aptian)

Superfamily Piesmatoidea Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843

Piesmatidae Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843; Cretaceous (Aptian)–Holocene

Superfamily Pyrrhocoroidea Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843

Largidae Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843; Cretaceous (Santonian)–Holocene

Pyrrhocoridae Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843; Eocene (Priabonian)–Holocene

Superfamily Pentatomoidea Leach, Reference Leach1815

Acanthosomatidae Stål, Reference Stål1864; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Aphylidae Bergroth, Reference Bergroth1906; Holocene

Canopidae McAtee & Malloch, Reference McAtee and Malloch1928; Holocene

Corimelaenidae Uhler, Reference Tullgren1871 (including Thyreocoridae Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843); Holocene

Cydnidae Billberg, Reference Billberg1820; [Jurassic (Toarcian)] (Cretaceous (Hauterivian)–Holocene

Cyrtocoridae Distant, Reference Distant1880; Holocene

Dinidoridae Stål, Reference Stål1867; Holocene

Lestoniidae China, Reference China1955; Holocene

Megarididae McAtee & Malloch, Reference McAtee and Malloch1928; Holocene

Mesopentacoridae† Popov, Reference Popov1968; Jurassic (Toarcian)-Cretaceous (Aptian)

Parastrachiidae Oshanin, Reference Oshanin1922; Holocene

Pentatomidae Leach, Reference Leach1815; Cretaceous (Aptian)-Holocene

Phloeidae Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843; Holocene

Plataspididae Dallas, Reference Dallas1851; Holocene

Primipentatomidae† Yao, Cai, Rider & Ren, Reference Yao, Ren, Rider and Cai2013; Cretaceous (Barremian–Aptian)

Probascanionidae† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1939; Jurassic (Toarcian)

Protocoridae† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906; Jurassic (Hettangian–Toarcian)

Saileriolidae China & Slater, Reference China and Slater1956; Holocene

Scutelleridae Leach, Reference Leach1815; [Eocene (Ypresian)]–Holocene

Tessaratomidae Stål, Reference Shcherbakov, Popov, Rasnitsyn and Quicke1864; Miocene (Burdigalian)–Holocene

Thaumastellidae Seidenstücker, Reference Seidenstücker1960; Cretaceous (Barremian)–Holocene

Urostylididae Dallas, Reference Dallas1851; Miocene (Burdigalian)–Holocene

Venicoridae† Yao, Ren & Cai, Reference Yao, Cai and Ren2012 in Yao et al. Reference Yao, Cai and Ren2012; Cretaceous (Barremian–Aptian)

Suborder Paleorrhyncha† Carpenter, Reference Carpenter1931

Superfamily Archescytinoidea† Tillyard, Reference Tillyard1926

Archescytinidae† Tillyard, Reference Tillyard1926; Carboniferous (Gzhelian)–Triassic (Induan)

Suborder Sternorrhyncha Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843

Archiconiopterygidae† Ansorge, Reference Ansorge1996; Jurassic (Toarcian)

Clade Aphidiformes sensu Schlee, Reference Schlee1969a (= Aphidococca sensu Kluge, Reference Kluge2010)

Infraorder Aphidomorpha Becker-Migdisova & Aizenberg, Reference Becker-Migdisova1962

Superfamily Adelgoidea Schouteden, Reference Schouteden1909

Adelgidae Schouteden, Reference Schouteden1909; [Cretaceous (Albian)] Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Elektraphididae† Steffan, Reference Steffan1968; Cretaceous (Santonian)–Pliocene (Piazencian)

Mesozoicaphididae† Heie in Heie & Pike, 1992; Cretaceous (Campanian)

Superfamily Aphidoidea Latreille, Reference Latreille1802

Aiceonidae Raychaudhuri, Pal & Ghosh, Reference Raychaudhuri, Pal, Ghosh and Raychaudhuri1980; Holocene

Anoeciidae Tullgren, Reference Toenschoff, Gruber and Horn1909; Holocene

Aphididae Latreille, Reference Latreille1802; Cretaceous (Santonian)–Holocene

Baltichaitophoridae† Heie, Reference Heie1980; Eocene (Lutetian–Priabonian)

Canadaphididae† Richards, Reference Richards1966; Cretaceous (Barremian–Campanian)

Cretamyzidae† Heie & Pike, Reference Heie and Pike1992; Cretaceous (Campanian)

Drepanochaitophoridae† Zhang & Hong, Reference Zalessky1999; Eocene (Ypresian)

Drepanosiphidae Herrich-Schäffer, Reference Herrich-Schäffer and Koch1857; Cretaceous (Aptian)–Holocene

Eriosomatidae Kirkaldy, Reference Kirkaldy1905; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Greenideidae Baker, Reference Baker1920; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Hormaphididae Mordvilko, Reference Mordvilko1908; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Isolitaphidae Poinar, Reference Poinar2017; Cretaceous (Cenomanian)

Lachnidae Herrich-Schäffer, Reference Herrich-Schäffer and Koch1857; Miocene (Serravalian)–Holocene

Oviparosiphidae† Shaposhnikov, Reference Shaposhnikov1979; Jurassic (Toarcian)–Cretaceous (Aptian)

Parvaverrucosidae† Poinar & Brown, Reference Poinar and Brown2006; Cretaceous (Cenomanian)

Phloeomyzidae Mordvilko, Reference Mordvilko1934; [Eocene (Lutetian)]–Holocene

Rasnitsynaphididae† Homan & Wegierek, Reference Homan and Wegierek2011; Cretaceous (Aptian)

Sinaphididae† Zhang, Zhang, Hou & Ma, Reference Zhang and Hong1989; Cretaceous (Aptian)

Tamaliidae Oestlund, Reference Oestlund1922; Holocene

Thelaxidae Baker, Reference Baker1920; Cretaceous (Barremian)–Holocene

Superfamily Genaphidoidea† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1907

Genaphididae† Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1907; Cretaceous (Berriasian)

Superfamily Palaeoaphidoidea† Richards, Reference Richards1966

Juraphididae† Żyła, Blagoderov & Wegierek, Reference Zrzavý2014; Jurassic (Callovian)–Cretaceous (Aptian)

Palaeoaphididae† Richards, Reference Richards1966; Cretaceous (Aptian–Campanian)

Shaposhnikoviidae† Kononova, Reference Kononova1976; Cretaceous (Santonian)

Szelegiewicziidae† Wegierek, Reference Weber1989; Jurassic (Bajocian)–Cretaceous (Aptian)

Superfamily Phylloxeroidea Herrich-Schäffer, Reference Herrich-Schäffer and Koch1857

Phylloxeridae Herrich-Schäffer, Reference Herrich-Schäffer and Koch1857; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Superfamily Tajmyraphidoidea† Kononova, Reference Kononova1975

Burmitaphididae† Poinar & Brown, Reference Poinar and Brown2005; Cretaceous (Albian–Cenomanian)

Grassyaphididae† Heie in Heie & Azar, Reference Heie and Azar2000; Cretaceous (Campanian)

Khatangaphididae† Heie in Heie & Azar, 5; Cretaceous (Cenomanian-Santonian)

Lebanaphididae† Heie in Heie & Azar, Reference Heie and Azar2000; Cretaceous (Barremian)

Retinaphididae† Heie in Heie & Azar, Reference Heie and Azar2000; Cretaceous (Santonian)

Tajmyraphididae† Kononova, Reference Kononova1975; Cretaceous (Santonian)

Superfamily Triassoaphidoidea† Heie, Reference Heie1999

Creaphididae† Shcherbakov & Wegierek, Reference Shcherbakov and Wegierek1991; Triassic (Carnian)

Triassoaphididae† Heie, Reference Heie1999; Triassic (Carnian)

Leaphididae† Shcherbakov, Reference Shcherbakov2010; Triassic (Anisian)

Lutevanaphididae† Szwedo, Lapeyrie & Nel, Reference Szwedo, Lapeyrie and Nel2015; Permian (Artinskian)

Infraorder Coccidomorpa Heslop-Harrison, Reference Heslop Harrison1952

Clade Archecoccoidea Borchsenius Reference Borchsenius1958

Apticoccidae† Vea & Grimaldi, Reference Van Valen2015; Cretaceous (Barremian)

Arnoldidae† Koteja, Reference Koteja and Azar2008; Eocene (Lutetian–Priabonian)

Burmacoccidae† Koteja, Reference Koteja2004; Cretaceous (Cenomanian)

Callipappidae MacGillivray, Reference MacGillivray1921; Holocene

Coelostomidiidae Morrison, Reference Morrison1927; Holocene

Electrococcidae† Koteja, Reference Koteja and Grimaldi2000b; Cretaceous (Barremian–Campanian)

Grimaldiellidae† Koteja, Reference Koteja and Grimaldi2000b; Cretaceous (Turonian)

Grohnidae† Koteja, Reference Koteja and Azar2008; Eocene (Lutetian-Priabonian)

Hammanococcidae† Koteja & Azar, Reference Koteja and Azar2008; Cretaceous (Barremian)

Jersicoccidae† Koteja, Reference Koteja and Grimaldi2000b; Cretaceous (Turonian)

Kozariidae† Vea & Grimaldi, Reference Van Valen2015; Cretaceous (Cenomanian)

Kukaspididae† Koteja & Poinar, Reference Koteja and Poinar2001; Cretaceous (Albian)

Kuwaniidae MacGillivray, Reference MacGillivray1921; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Labiococcidae† Koteja, Reference Koteja and Grimaldi2000b; Cretaceous (Turonian)

Lebanococcidae† Koteja & Azar, Reference Koteja and Azar2008; Cretaceous (Barremian)

Lithuanicoccidae† Koteja, Reference Koteja and Azar2008; Eocene (Lutetian–Priabonian)

Marchalinidae Morrison, Reference Morrison1927; Holocene

Margarodidae Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1899; [Cretaceous (Barremian)] Eocene (Ypresian)–Holocene

Matsucoccidae Morrison, Reference Morrison1927; Cretaceous (Valanginian)–Holocene

Monophlebidae Morrison, Reference Morrison1927; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Ortheziidae Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843; Cretaceous (Barremian)–Holocene

Pennygullaniidae† Koteja & Azar, Reference Koteja and Azar2008; Cretaceous (Barremian)

Phenacoleachiidae Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1902; Holocene

Pityococcidae McKenzie, Reference McKenzie1942; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Putoidae Tang, Reference Tang, Yao and Ren1992; Cretaceous (Barremian)–Holocene

Serafinidae† Koteja, Reference Koteja and Azar2008; Eocene (Lutetian–Priabonian)

Steingeliidae Morrison, Reference Morrison1927; Cretaceous (Barremian)–Holocene

Stigmacoccidae Morrison, Reference Morrison1927; Holocene

Termitococcidae Jakubski, Reference Jakubski1965; Holocene

Weitschatidae† Koteja, Reference Koteja and Azar2008; Cretaceous (Cenomanian)–Eocene (Priabonian)

Xylococcidae Pergande in Hubbard & Pergande, Reference Hubbard and Pergande1898; Cretaceous (Aptian)–Holocene

Clade Neococcoidea Borchsenius Reference Borchsenius1950

Aclerdidae Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1905; Holocene

Albicoccidae† Koteja, Reference Koteja2004; Cretaceous (Cenomanian)

Asterolecaniidae Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1896; Holocene

Beesoniidae Ferris, Reference Ferris1950; Holocene

Calycicoccidae Brain, Reference Brain1918; Holocene

Caryonemidae Richard, Reference Richard1986; Holocene

Cerococcidae Balachowsky, Reference Balachowsky1942; Holocene

Cissococcidae Brain, Reference Brain1918; Holocene

Coccidae Fallén, Reference Fallén1814; Cretaceous (Cenomanian)–Holocene

Conchaspididae Green, Reference Green1896; Holocene

Cryptococcidae Kosztarab, Reference Kosztarab1968; Holocene

Dactylopiidae Signoret, Reference Signoret1875; [Miocene (Aquitanian)]–Holocene

Diaspididae Targioni-Tozzetti, Reference Tang1868; Holocene

Eriococcoidae Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1899; Cretaceous (Turonian)–Holocene

Halimococcidae Brown & McKenzie, Reference Brown and McKenzie1962; Holocene

Hodgsonicoccidae† Vea & Grimaldi, Reference Van Valen2015; Cretaceous (Barremian)–Holocene

Inkaidae† Koteja, Reference Koteja1989; Cretaceous (Santonian)

Kermesidae Signoret, Reference Signoret1875; Eocene (Lutetian)–Holocene

Kerridae Lindinger, Reference Lindinger1937; Holocene

Lecanodiaspididae Targioni-Tozzetti, Reference Targioni-Tozetti1869; Holocene

Micrococcidae Silvestri, Reference Silvestri1939; Holocene

Phoenicococcidae Stickney, Reference Stickney1934; Holocene

Porphyrophoridae Signoret, Reference Signoret1875; Holocene

Pseudococcidae Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1905; Cretaceous (Barremian)–Holocene

Rhizoecidae Williams, Reference Westwood1969; Holocene

Stictococcidae Lindinger, Reference Lindinger1913; Holocene

Tachardiidae Green, Reference Green1896; Holocene

Infraorder Naibiomorpha† infraord. nov.

Remark. This group is placed within Aphidomorpha (e.g., Heie & Wegierek Reference Heie and Wegierek2011) or in Coccidomorpha (e.g., Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov2007a). As the classifications and relationships within these infraorders are still debatable, a new taxonomic unit to comprise three extinct families is proposed.

Superfamily Naibioidea† Shcherbakov, Reference Shcherbakov2007a

Dracaphididae† Hong, Zhang, Guo & Heie, Reference Hong, Zhang, Guo and Heie2009; Triassic (Ladinian)

Naibiidae† Shcherbakov, Reference Shcherbakov2007a; Triassic (Carnian)–Eocene (Lutetian)

Sinojuraphididae† Huang & Nel, Reference Huang and Nel2008; Jurassic (Callovian–Oxfordian)

Infraorder Pincombeomorpha† Shcherbakov, Reference Shcherbakov and Koteja1990

Superfamily Pincombeoidea† Tillyard, Reference Tillyard1922

Boreoscytidae† Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1949; Permian (Kungurian–Roadian)

Pincombeidae† Tillyard, Reference Tillyard1922; Permian (Changhsingian)–Triassic (Carnian)

Simulaphididae† Shcherbakov, Reference Shcherbakov2007a; Permian (Changhsingian)–[Triassic (Norian)]

Clade Psylliformes sensu Schlee, Reference Schlee1969a (= Psyllaleyroda sensu Kluge, Reference Kluge2010)

Infraorder Aleyrodomorpha Chou, Reference Chou1963

Superfamily Aleyrodoidea Westwood, Reference Westwood1840

Aleyrodidae Westwood, Reference Westwood1840; Jurassic (Oxfordian)-Recent

Infraorder Psyllaeformia Verhoeff, Reference Vea and Grimaldi1893 (= Psyllodea Flor, Reference Flor1861)

Superfamily Protopsyllidioidea† Carpenter, Reference Carpenter1931

Protopsyllidiidae† Carpenter, Reference Carpenter1931; Permian (Kungurian)–Cretaceous (Turonian)

Superfamily Psylloidea Latreille, Reference Latreille1807

Aphalaridae Löw, Reference Löw1879; Eocene (Lutetian)-Holocene

Calophyidae Vondraček, Reference von Dohlen and Moran1957; Holocene

Carsidaridae Crawford, Reference Crawford1911; Eocene (Priabonian)–Holocene

Homotomidae Heslop-Harrison, Reference Heslop-Harrison1958; Holocene

Liadopsyllidae† Martynov, Reference Martynov1927; Jurassic (Toarcian)–Cretaceous (Aptian)

Liviidae Löw, Reference Löw1879; Miocene (Burdigalian)–Holocene

Malmopsyllidae† Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1985; Jurassic (Callovian–Oxfordian)

Phacopteronidae Heslop-Harrison, Reference Heslop-Harrison1958; Miocene (Burdigalian)–Holocene

Psyllidae Latreille, Reference Latreille1807; Miocene (Burdigalian)–Holocene

Triozidae Löw, Reference Löw1879; Miocene (Burdigalian)–Holocene

Remarks. The previous comprehensive list containing data on the fossil record of the Hemiptera was presented by Nicholson et al. (Reference Nicholson, Mayhew and Ross2015). However, this list comprises data up to end of 2009, and listed 194 families with a fossil record. Szwedo et al. (Reference Szwedo, Bourgoin and Lefebvre2004) listed 221 families of the Hemiptera, both extinct and extant. Numerous extinct families were described after this date, and some new Recent families were also discovered (Schuh et al. Reference Schuh, Weirauch, Henry and Halbert2008), and others were established as a result of molecular and revisionary works. The list above comprises 302 families, including 142 extinct families and 78 extant families that lack a fossil record. The classification of the Hemiptera is still subject to discussion and the data on families and their fossil record will be subject to change from new discoveries. However, these current figures are a good measure of the evolutionary success of the group.

2. The geological history of Hemiptera

The oldest Hemiptera – Protoprosbolidae and Aviorrhynchidae – appeared in the Carboniferous (Fig. 1). Since then, the evolution of hemipterans was subject to originations and extinctions, ecological shifts and revolutionary changes. The first division of ancient Hemiptera took place in the Carboniferous – the sternorrhynchan lineage which developed various forms of ‘quasiholometaboly' (Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov and Schaefer1996) vs. the ‘euhemimetabolic' euhemipteran lineage.

Figure 1 Relationships of major Hemiptera groups, major global changes affecting the evolution of the order and their heritable symbionts. Main symbiotic groups according to Bennett & Moran (Reference Bennett and Moran2015). Times of estimated interrelationships given tentatively. Abbreviations: Betaproteo = beta proteobacterial symbiont(s); Gamma Halomo = gamma halomoproteobacterial symbiont(s); Gamma Entero = gamma enteroproteobacterial symbiont(s); Alphaproteo = alpha proteobacterial symbiont(s); Bacteriodetes = phylum Bacteriodetes symbiont(s); yeast-like = yeast-like symbiont(s).

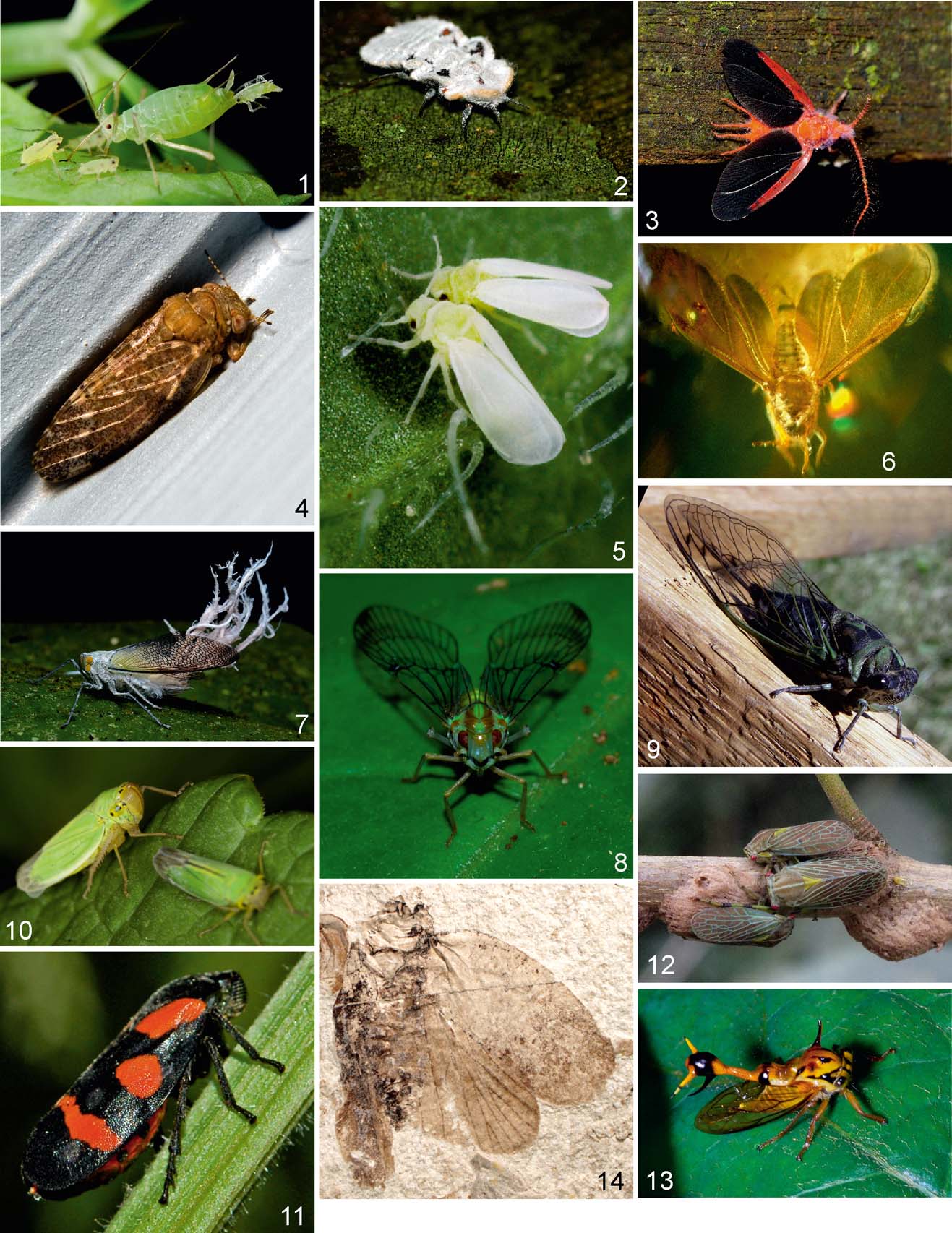

Plate 1 Diversity of the Hemiptera. (1) A pea aphid Acyrtosiphon pisum (Aphididae) giving birth to live young. Photo: Shipher Wu, National Taiwan University, CC BY-SA 3.0. (2–3) Giant scale insect Drosicha corpulenta (Monophlebiidae): (2) female; (3) male. Photos: Bernard Dupont, CC BY-SA 2.0. (4) Pachypsylla sp. (Aphalaridae). Photo: Bruce Marlin, CC BY-SA 3.0. (5) Whitefly Bemisia tabaci (Aleyrodidae), USDA, public domain. (6) Winged aphid (Aphidoidea) from Baltic amber. Photo: Anders L. Damgaard, CC BY-SA 4.0. (7) A planthopper Pterodictya reticularis (Fulgoridae) with abdominal filaments of ketoester wax. Photo: Geof Gallice, CC BY-SA 2.0. (8) A planthopper (Tropiduchidae). Photo: Bernard Dumont, CC BY-SA 2.0. (9) Annual cicada Tibicen linnei (Cicadellidae). Photo: Bruce Marlin, CC BY-SA 2.5. (10) Green leafhopper Cicadella viridis (Cicadellidae). Photo: gbohne, CC BY-SA 2.0. (11) Cercopis sanguinolenta (Cercopidae), Photo: Hectonichus, CC BY-SA 3.0. (12) Aetalion sp. (Aetalionidae). PyBio.org. (13) Membracid treehopper Heteronotus sp. (Membracidae). Photo: Bernard Dupont, CC BY-SA 2.0. (14) Fossil hylicellid (Hylicellidae: Vietocyclinae), Middle Jurassic Daohugou Biota, Coll. NIGPAS NN4. Photo: J. Szwedo.

Plate 2 Diversity of the Hemiptera. (1) Moss bug Xenophyes rhachilophus (Peloridiidae). Photo: S. E. Thorpe, public domain. (2) Ochterus marginatus (Ochteridae), public domain. (3) Water strider (Gerridae). Photo: Ryan Hodnett, CC BY-SA 4.0. (4) Nepa rubra (Nepidae). Photo: Holger Gröschl, CC BY-SA 2.0. (5) Big-eyed toad bug Gelastocoris oculatus (Gelastocoridae). Photo: Ryan Hodnett, CC BY-SA 4.0. (6) Cryptostemna sp., female (Dipsocoridae). Photo: Michael F. Schönitzer, CC BY-SA 3.0. (7) Female of bed bug Cimex lectularius (Cimicidae), on the fur of one of its hosts, a bat. Photo: Jacopo Werther, CC BY-SA 4.0. (8) Checkerboard ground bug Spilostethus saxatilis (Lygaeidae). Photo: Bernard Dupont, CC BY-SA 2.0. (9) Plant bug Calocoris roseomaculatus (Miridae). Photo: Hectonichus, CC BY-SA 3.0. (10) Assassin bug (Reduviidae), female laying eggs. Photo: Bernard Dupont, CC BY-SA 2.0; (11) Sycamore lace bug Corythucha ciliata (Tingidae), Photo: Jacopo Werther, CC BY-SA 2.0. (12) Flag-footed bug Anisoscelis affinis (Coreidae). Photo: Cheryl Harleston, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. (13) Shield-backed bug (Scutelleridae). Photo: Bernard Dupont, CC BY-SA 2.0.

The oldest Paleorhycha: Archescytinidae (paraphyletic group) are known since the latest Carboniferous, and this group seems to be ancestral to sternorrhynchan lineages (Fig. 1). Archescytinidae presents various adaptations for living on plants (such as the seed ferns Peltaspermales and the early gymnosperms Cordaitales and Cycadales). The rostrum base of these archaic tiny sap-feeders was placed variably – more anteriorly on the head (auchenorrhynchous position), or shifted posteriad, between the legs (sternorrhynchous position). Another example of disparity of these insects is in their ovipositors – it was protruding caudally, or its long needle-like inner gonapophyses formed a coiled loop under the abdomen in repose (Shcherbakov & Popov Reference Shcherbakov, Popov, Rasnitsyn and Quicke2002). The hypothesis that the ovipositor was used to lay eggs inside plant strobiles, and that nymphs dwelt there until ripe strobile would dehisce (Becker-Migdisova Reference Becker-Migdisova1972), was argued by Emeljanov (Reference Emeljanov2014), who stated that it was certainly used for inserting eggs into plant tissues and not for moving them into deep and narrow axils. The flattened, phloem-feeding nymphs, clinging on to plants, seems to be common among Archescytinidae, Psylliformes and early Aleyrodomorpha, probably also among Pincombeomorpha, early Aphidomorpha and early Coccidomorpha (Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov and Schaefer1996; Shcherbakov & Popov Reference Shcherbakov, Popov, Rasnitsyn and Quicke2002; Drohojowska et al. Reference Drohojowska, Szwedo and Azar2013).

The sternorrhynchans of the infraorder Pincombeomorpha, earliest Aphidomorpha and psylliformian Protopsyllidiidae are present among fossils of the Permian. Permian paleorrhynchans – Archescytinidae are diverse at these times, but they disappear from the fossil record at the end of the period. Triassic Pincombeomorpha had become rare, diverse Aphidomorpha appeared and Protopsyllidiidae are present in Gondwanaland.

It can be speculated that Late Triassic–Jurassic Coccidomorpha (alas unknown) were probably associated with gymnosperms and these ancestral forms probably became extinct (Koteja Reference Koteja1985, Reference Koteja and Rosen1990, Reference Koteja2000a, Reference Koteja and Grimaldib, Reference Koteja and Azar2008; Koteja & Azar Reference Koteja and Azar2008). The presumption that these insects, like aphids, were modified, probably due to the diminuation of the body size and probably a more cryptic lifestyle is reasonable. Koteja (Reference Koteja1985) suggested that ancestral coccidomorphans could shift to “hypogeic” habitats, i.e., leaflitter on the forest floor. Rapid climate change in the Jurassic had been documented (Jenkyns Reference Jenkyns2003), and could be one of the factors for the diversification of the lineages leading to modern representatives of the Sternorrhyncha. These early aphids were very probably oviparous, however it could be assumed that parthenogenesis existed from the very beginning (Dixon Reference Dixon1985; Heie Reference Heie, Leather, Watt, Mills and Walters1994), as it occurrs in the Recent representatives Phylloxeroidea, Adelgoidea and Aphidoidea, as well as in coccids and scale insects (Heie Reference Heie, Leather, Watt, Mills and Walters1994; Koteja Reference Koteja and Boczek1996; Gullan & Martin Reference Gullan, Martin, Cardé and Resh2003). It also seems that alternation between parthenogenetic generations and sexuales amongst aphids is probably as old as parthenogenesis itself (Heie Reference Heie, Leather, Watt, Mills and Walters1994). Both groups (aphids and scale insects) evolved and diversified rapidly in the Cretaceous. Several specialised families appeared, but went extinct by the end of the Cretaceous (von Dohlen & Moran Reference Verhoeff2000; Koteja & Azar Reference Koteja and Azar2008; Heie & Wegierek Reference Heie and Wegierek2011; Hodgson & Hardy Reference Hodgson and Hardy2013). The Jurassic Protopsyllidiidae went back to the northern hemisphere, and the earliest Psylloidea (Liadopsyllidae and Malmopsyllidae) and the oldest whiteflies (Aleyrodidae) appeared (Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov2000a).

Most of the recent crown-groups of sternorrhynchans appeared and/or diversified in the Cretaceous period. Cretaceous times are rich in various groups of aphids (Heie & Wegierek Reference Heie and Wegierek2011), scale insects (Koteja & Azar Reference Koteja and Azar2008; Hodgson & Hardy Reference Hodgson and Hardy2013) and diverse whiteflies (Drohojowska & Szwedo Reference Drohojowska and Szwedo2015; Szwedo & Drohojowska Reference Tang, Yao and Ren2016); psylloids seem to be uncommon at these times (Grimaldi Reference Grimaldi2003; Ouvrard et al. Reference Ouvrard, Burckhardt, Azar and Grimaldi2010). The mid-Cretaceous biotic reorganisation of the biosphere (Rasnitsyn Reference Rasnitsyn and Ponomarenko1988; Zherikhin Reference Zhang, Golub, Popov and Shcherbakov2002; Krassilov Reference Krassilov2003), with the extinction of numerous gymnosperm hosts and the diversification of angiosperms in the middle to Late Cretaceous, perhaps drove the evolutionary race, with many short-present, endemic forms present in this period. It appears that the great K/P extinction did not strongly affect these insects, and they further diversified and specialised with host-plants during the Cenozoic (Fig. 1).

The beginnings of the Euhemiptera and the first diversification of the lineages within are hidden deep in the Carboniferous (Nel et al. Reference Nel, Roques, Nel, Prokin, Bourgoin, Prokop, Szwedo, Azar, Desutter-Grandcolas, Wappler, Garrouste, Coty, Huang, Engel and Kirejtshuk2013). The two known families, Protoprosbolidae and Aviorrhynchidae, are not placed at suborder level. In the Permian the Cicadomorpha (Fig. 1) are diversified and morphologically disparate in body size (3 mm to over 100 mm) and in the degree of vein polymerisation. The earliest, ancient Prosorrhyncha (Ingruomorpha) are still morphologically very close to cicadomorphans, their descendants, the earliest coleorrhynchan Progonocimicicidae appeared and the bizarre Fulgoromorpha – Coleoscytidae and later, Surijokocixiidae – presenting more general fulgoromorphan morphology, are recorded among fossils (Fig. 1). By the end of the Permian, Paraknightiidae, presumed ancestors of the true bugs (Heteroptera), appeared (Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov and Schaefer1996; Shcherbakov & Popov Reference Shcherbakov, Popov, Rasnitsyn and Quicke2002). At this time, all these insects were probably not jumping (they were not ‘hoppers') and were phytophagous, probably phloem-feeding on various gymnosperm plants. During the Triassic, several novelties appeared. The major one was that the true bugs (Heteroptera) appeared (Fig. 1). Their Permian ancestors are hypothesised to feed on helophytes (emergent water plants), with coriaceous tegmina securely fixed on the thorax in repose (which might be capable of subelytral air storage). Shcherbakov (Reference Shcherbakov and Schaefer1996) and Shcherbakov & Popov (Reference Shcherbakov, Popov, Rasnitsyn and Quicke2002) hypothesised that neoteny and structural simplification played a greater role in the heteropteran origin than ‘anagenetic' differentiation. The prognathous head with long oligomerous (reduced in number of segments) antennae, typical of true bugs, appeared in nymphs of the Late Permian Paraknightiidae and, together with the flattening of the body, were possibly carried over to the imago later on. The morphological changes in ancient Heteroptera could be explained through emigration from a three-dimensional habitat (vegetation) to a two-dimensional water surface/floating plant carpets habitat.

The first true bugs are believed to be scavengers and/or passive predators, which used their long ‘probing' rostrum to feed on soil microfauna of the littoral zone or inhabiting floating plant carpets (Shcherbakov & Popov Reference Shcherbakov, Popov, Rasnitsyn and Quicke2002). Then, Heteroptera adopted zoophagy at the earliest stages of their evolution. Triassic Heteroptera were represented exclusively by Nepomorpha. It is hard to say if the ancient euhemiptera used substrate-borne signalling for communication; however, it is very likely (Senter Reference Senter2008). In the Triassic, the first fossil record of stridulatory organs among Dysmorphoptilidae (Evans Reference Evans1961; Lambkin Reference Lambkin2015, 2016) and Ipsviciidae is observed, so the songs of these insects were transmitted in the air for the first time (Shcherbakov & Popov Reference Shcherbakov, Popov, Rasnitsyn and Quicke2002). The Triassic is also a heyday of the Scytinopteromorpha, which are represented by diverse and disparate taxa. The oldest representatives of the only living lineage of Cicadomorpha (Clypeata – Hylicelloidea) appeared for the first time in the fossil record and diversified by the Late Triassic. However, the Cicadomorpha fossils of the Triassic were dominated by extinct taxa: Dysmorphoptiloidea, Pereborioidea and Palaeontinoidea. The Triassic fossil record of Fulgoromorpha is extremely poor, represented only by Surijokocixiidae. The Coleorrhyncha are represented quite well in the various Triassic deposits of the world, by diverse Progonocimicidae.

Hemelytrata diversity and disparity increased considerbly during the Jurassic. The Fulgoromorpha are represented by the diverse family ‘Fulgoridiidae', certainly paraphyletic (Szwedo et al. Reference Szwedo, Bourgoin and Lefebvre2004; Bourgoin & Szwedo Reference Bourgoin and Szwedo2008), and the bizarre Qiyangiricaniidae (Fulgoroidea) (Szwedo et al. Reference Szwedo, Wang and Zhang2011). The Cicadomorpha were highly diverse, represented at these times by relic Dysmorphoptiloidea, highly diverse Palaeontinidae and various and diversified Clypeata: Hylicellidae and the oldest representatives of the superfamilies present in the recent fauna, i.e., Cicadoidea (Tettigarctidae), Cercopoidea (Procercopidae and Sinoalidae) and Cicadelloidea (Archijassidae) (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Szwedo and Zhang2010). The latter family presents the first evidence of ‘leafhopperization'; i.e., successive acquisition of cicadelloid characters (Shcherbakov 2012). Representatives of the Scytinopteromorpha (Ipsviciidae, Scytinopteridae) are still present in the Jurassic fossil record; however, they are rare. True bugs of the Jurassic are diversified (Nepomorpha, Gerromorpha, Dipsocoromorpha, Leptopodomorpha, Pentatomomorpha), and the first groups returning to phytophagy appeared at these times; for example, Rhopalidae, Miridae and Vetanthocoridae (Popov Reference Popov1968; Yao et al. Reference Williams2006a, Reference Yao, Cai and Renb, Reference Yao, Cai and Ren2007; Hou et al. Reference Hou, Yao, Zhang and Ren2012). The Jurassic is also rich in fossil Coleorrhyncha, numerous Progonocimicidae and less common Karabasiidae (Wang et al. Reference Vondráček2009).

The Cretaceous was period of dramatic change – most lineages well represented in the Triassic and Jurassic became extinct by the Mid-Cretaceous (Fig. 1). The Early Cretaceous witnessed the last Ipsviciidae (Scytinopteromorpha), Progonocimicidae and Karabasiidae (Coleorrhyncha) and the last non-Clypeata Cicadomorpha (Paleontinidae (Palaeontinoidea)). However, the Fulgoroidea became abundant and highy diverse and disparate in morphology (many still require formal description), and the oldest records of families present in the Recent fauna (Cixiidae and Achilidae) are known.

The Clypeata seems to begin prolific diversification at these times, with transitional forms between extinct Procercopidae and modern Aphrophoridae, earliest Cicadellidae and Myerslopiidae, and the first singing cicadas – Cicadidae (Hamilton Reference Hamilton and Grimaldi1990, 1992; Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov and Schaefer1996; Poinar & Kritsky Reference Poinar and Kritsky2011). The Early Cretaceous and mid-Cretaceous biotic re-organisation of the biosphere were times of prolific diversification of various groups of Heteroptera. Many families of the Recent fauna appeared for the first time, some others, exclusively Cretaceous, appeared and rapidly disappeared (Popov Reference Popov1986; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Sun and Zhang2005; Perrichot et al. Reference Perrichot, Nel, Guilbert and Neraudeau2006; Poinar & Buckley Reference Poinar and Buckley2009; Azar et al. 2011; Golub et al. Reference Golub, Popov and Arillo2012; Yao et al. Reference Yao, Cai and Ren2012, Reference Yao, Ren, Rider and Cai2013, Reference Yao, Cai, Rieder and Ren2014). The first blood-feeding Heteroptera appeared at these times (Yao et al. Reference Yao, Cai, Rieder and Ren2014), and phytophagous groups diversified and adapted to new challenges (Tang et al. Reference Takiya, Tran, Dietrich and Moran2015, Reference Tang, Yao and Ren2016).

The Cenozoic record and modern diversity of the Euhemiptera is represented by nearly half of all known families. However, some groups, such as Coleorrhyncha, have low diversity (single family Peloridiidae); whilst others, such as Fulgoromorpha or Heteroptera, are represented by a high number of families. In contrast, Clypeata (Fig. 1) the only survivors of Cicadomorpha, are represented by a few families (grouped in the superfamilies Cicadoidea, Cercopoidea, Cicadelloidea, Myerslopioidea and Membracoidea). Somewhere near the boundary of the Oligocene and Miocene, the Membracoidea s. str. appeared, maybe due to biotic changes, global cooling and drying, and the origin of treehoppers could result from neoteny (Hamilton Reference Hamilton2012).

However, it must be noted, that the family Cicadellidae, with about 40 recognised subfamilies (Dietrich Reference Dietrich2005), and the assumed diversity of 150,000 species (or more) is one of the dominant groups in the modern fauna.

3. Reasons for success and defeat

Evolution may be dominated by biotic factors, as in the Red Queen model (Van Valen Reference Usinger1973), or abiotic factors, as in the Court Jester model (Barnosky Reference Barnosky1999, Reference Barnosky2001), or a mixture of both (Benton Reference Benton2009). The Red Queen hypothesis (Van Valen Reference Usinger1973) was originally used to describe competition between species being the driving factor behind the high diversity of species we see today. Over 40 years later, it is still an attractive and influential (Brockhurst et al. Reference Brockhurst, Chapman, King, Mank, Paterson and Hurst2014). The Court Jester hypothesis (Barnosky Reference Barnosky1999, Reference Barnosky2001) suggests that changes in species may result not due to competition between species, but due to geological or climatic events that act as the driving force behind evolution, and the formation of new species. The two models appear to operate predominantly over different geographic and temporal scales: competition, predation, parasitism and other biotic factors that shape ecosystems locally and over short time-spans. Extrinsic factors, such as climatic and tectonic events, shape larger-scale patterns regionally and globally, and over thousands and millions of years.

Palaeobiological studies suggest that Hemiptera evolution was driven largely by abiotic factors such as climate, landscape, but also biotic factors such as food supply or new niches appeared, which are important factors for lineage formation. The first major abiotic factor influencing the evolutionary direction of the Hemiptera was the Permian/Triassic extinction event (Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov2000b). The next Court Jester event, the Mid-Cretaceous biotic re-organisation of the biosphere, resulted in the extinction of many specialised Mesozoic and relic Paleozoic taxa and in the origination of the modern fauna (Fig. 1). These phytophagous groups, which passed the challenge of host plant shift, met one more Court Jester event – the Oligocene–Miocene global cooling and drying, resulting in new, grassy habitats for colonisation (Fig. 1).

Very little attention has been given to biotic factors and interactions which shaped the evolutionary history of the hemipterans. How strong and in which way all the proposed classes of Red Queen dynamics – Fluctuating Red Queen, Escalatory Red Queen and Chase Red Queen (Brockhurst et al. Reference Brockhurst, Chapman, King, Mank, Paterson and Hurst2014) – are driving the moderm hemipterans, and how they could manage in the past, are still open to question.

One more, overlooked, effect must be taken into consideration in any analysis of the evolutionary successes and defeats observed among the Hemiptera and various lineages within the order – the influence of endosymbiotic mutualistic interactions. Contrary to the Red Queen hypothesis, which suggests that fast evolution is favoured in coevolutionary interactions, the Red King effect assumes that slowly evolving species are likely to gain a disproportionate fraction of the surplus generated through mutualism. This occurs because, on an evolutionary timescale, slow evolution effectively ties the hands of a species, allowing it to “commit” to threats and thus “bargain” more effectively with its partner over the course of the coevolutionary process (Bergstrom & Lachmann Reference Bergstrom and Lachmann2003a, Reference Bergstrom, Lachmann and Hammersteinb).

It could be assumed that the symbiotic association of the ancient paleorrhynchans and sternorrhychans with obligate microorganisms took place early in the history of these groups, probably in their Carboniferous ancestors (Fig. 1). Symbiotic Sulcia is present in modern descendants within Fulgoromorpha and Cicadomorpha: Clypeata lineages (Moran et al. Reference Moran, Tran and Gerardo2005), which suggest a very deep and ancient connection, with a common ancestor of these lineages in the Carboniferous. Zherikhin (Reference Zhang, Golub, Popov and Shcherbakov2002) stated that spore and pollen feeding was probably plesiomorphic, and this kind of feeding is observed in Permopsocida – closely related to the Hemiptera paraneopteran insects (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Bechly, Nel, Engel, Prokop, Azar, Cai, van de Kamp, Staniczek, Garrouste, Krogmann, Dos Santos Rolo, Baumbach, Ohlhoff, Shmakov, Bourgoin and Nel2016). This food source is considered to be much richer and more complete (with aminoacids, sugars, lipids) in nutrients than plant sap (phloem and especially xylem), so the transition to feed on phloem, rich in sugars and poor in aminoacids, would have been a challenge, which could be facilitated by associations with symbionts.

The Sternorrhyncha earliest symbiotic associations are difficult to resolve; the earliest Sternorrhyncha are regarded as phloem-feeders, and this connection is universal amongst Recent representatives of the group. In the modern descendants, the gammaproteobacteria of the Halomonadaceae are known as obligatory symbionts of psyllids and whiteflies, whilst among aphids and coccids, various obligatory bacterial endosymbionts (alphaproteobacteria, betaproteobacteria, gammaproteobacteria, Bacteroidetes) are known (Baumann Reference Baumann2005; Bennett & Moran Reference Bennett and Moran2015). It seems that obligatory endosymbiotic associations among Sternorrhyncha were not a single event, or the most ancient (common?) endosymbionts were replaced by others at very early stages of sternorrhynchan lineage separation.

Obligate symbiosis clearly shaped the evolution of the hemipterans, and it is clearly visible among various sternorrhynchan lineages (Toenschoff et al. Reference Tillyard2012; Bennett & Moran Reference Bennett and Moran2015). A variety of facultative endosymbiotic associations with diverse bacteria and yeasts can be found in all lineages of the Sternorrhyncha, (Moran et al. Reference Moran, McCutcheon and Nakabachi2008; Bennett & Moran Reference Bennett and Moran2015). Endosymbiotic relationships with bacteria and yeasts are also present also among euhemipterans (Müller Reference Müller1949, Reference Müller1962; Buchner Reference Buchner1965; Hosokawa et al. Reference Hosokawa, Kikuchi, Nikoh, Shimada and Fukatsu2006; Takiya et al. Reference Szwedo and Drohojowska2006 Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, McCutcheon, MacDonald, Romanovicz and Moran2014; Bennett & Moran Reference Bennett and Moran2015). It is evident that the effects of endosymbiosis on microevolutionary and macroevolutionary scales in evolution of these insects are of high importance (Fig. 1). New partners and new relationships are regularly reported (e.g., Michalik et al. Reference Michalik, Jankowska, Kot, Gołas and Szklarzewicz2015; Szklarzewicz et al. Reference Szklarzewicz, Grzywacz, Szwedo and Michalik2016). The macroevolutionary and ecological consequences of acquisition (and loss) of endosymbionts, and of replacements and compensations with another endosymbiont, are immense.

These interrelationships gave hemipterans the keys to unlocking new ecological niches, particularly those which rely on an unbalanced plant-sap diet, limited in essential amino acids and vitamins. As a result of multiple gains and losses of symbionts, the multiple mosaic of symbiont combinations is to be found in various groups. Both effects, that of the Red Queen and of the Red King, are to be observed among Hemiptera and their endosymbionts. Symbiotic interrelationships, driving both partners (insects and microorganisms), even if it brings perils of falling into an ‘evolutionary rabbit hole' (Bennett & Moran Reference Bennett and Moran2015), result in benefits, and the high ability of such relationships could be one of the responses for the unpredictable effects of the Court Jester effects.

Euhemiptera are believed to be monophyletic, the monophyly of sternorrhynchans is disputable. This is not only from the fossil record and its interpretation, but the different evolutionary strategies, range of adaptations and heterogeneity presented by the Hemiptera. Firstly, global events (climatic, abiotic) influenced the evolution of the hemipterans in different ways. Secondly, the biotic changes, host availabilities, host shifts and adaptations shaped the evolutionary scenarios of the order. Thirdly, long-term interaction with various internal symbionts and external partners, carved a distinct mark on the evolutionary traits of the group.

3. Conclusion

The Hemiptera can be treated as a uniform, monophyletic group, presenting a number of autapomorphies, recognisable in both extinct and Recent forms. However, the very early stages of the Hemiptera evolution remain virtually unknown. Several questions concerning the formation and specialisation of the rostrum remain unanswered. The head capsule structure needs to be reinterpreted. The wing structure, venation pattern and veins homologisation are still to be elaborated. The genital structures and homology of these elements are still disputable. The behaviour and other biological features, such as sound production, chemical communication, wax production and use, need attention. The endosymbiotic interactions and their influence on food adaptations and evolutionary processes are still far from being understood. The mutualistic interactions with external partners is another challenging field of research.

Some of these questions and problems addressed, can be at least partly, be answered by fossils. Uniformity of the Hemiptera in some features, enormous diversity in others, high adaptability to various conditions, and developmental plasticity – these phenomena are recorded in fossils. The evolvability of the Hemiptera and their vast potential for diversification, make studying the group frustrating on the one hand, but fascinating on the other.

4. Acknowledgements

I would like to cordially thank Dr Jun Chen (Linyi University) and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive reviews, and Dr Andrew J. Ross (National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh) and Mrs Vicki Hammond (Journals & Archive Officer, RSE) for the valuable comments and indications for greatly improving the earlier version of the paper. Special thanks to late Yuri A. Popov (Palaeontological Institute Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow) and Thierry Bourgoin (Muséum national d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris) for fruitfull discussions and encouragement for work on classification of the Hemiptera.