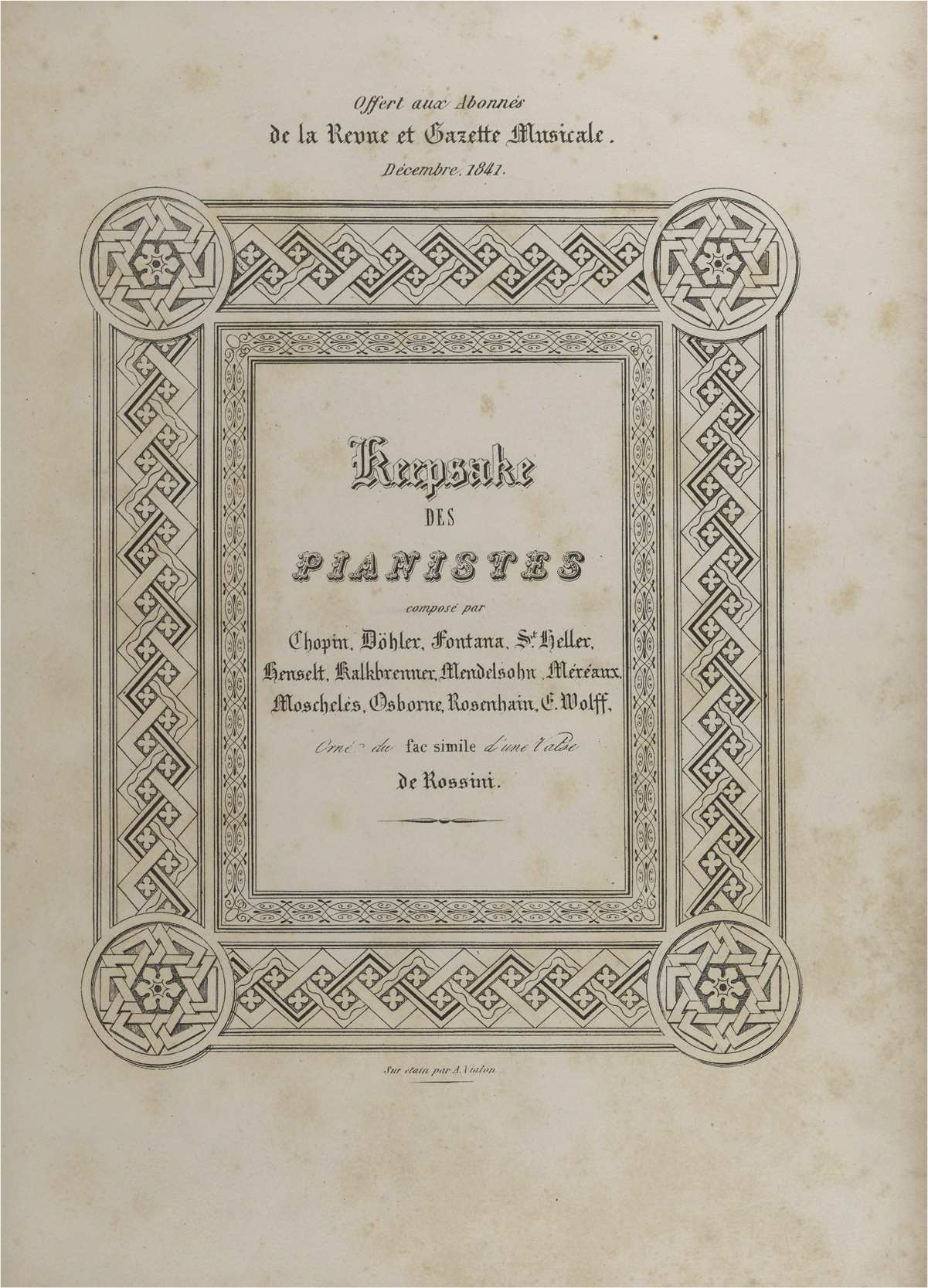

In 1841, a subscriber to the Revue et gazette musicale (hereafter RGM) would have received not only his or her weekly dose of musical news, reviews and essays, but also a number of perks: concert tickets to Pleyel's salon; portraits of celebrated musicians; and printed music, including an album of new piano pieces entitled Keepsake des pianistes. As stated prominently on its title page and in advertisements, the album was ‘ornamented by the facsimile of a waltz by Rossini’ (‘Orné du fac simile d'une Valse de Rossini’; see Figure 1). Hardly known for his pianism, Rossini would seem an odd choice for an album devoted to piano music. His odd-man-out status stands blazoned on the title page: while Chopin, Döhler, Fontana, Heller, Henselt, Kalkbrenner, Mendelssohn, Méreaux, Moscheles, Osborne, Rosenhain and Wolff are listed together as composers represented in the Keepsake, Rossini's name appears below, isolated – his contribution presented as merely a pretty hand.

Figure 1. Keepsake des pianistes (1841), title page. Philadelphia, PA, University of Pennsylvania Libraries, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, M1.K33 1839.

Or perhaps not ‘merely’. For there was much one could do with a facsimile of a composer's handwriting around 1840. Recovering just what one could do, however, requires setting aside modern musicological assumptions about the nature and uses of facsimile. Today, music facsimiles are made mainly to be examined by scholars and performers who seek insight into the composer's musical intentions – intentions potentially concealed or subverted by translation into print. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians currently defines ‘facsimile’ as ‘a genre of book publishing based on photo-mechanical printing techniques that attempts to recreate the appearance of an original handwritten manuscript or printed edition’, explaining that facsimiles are ‘produced, conceived and used as tools for study or investigation by scholars, researchers, teachers and others who might not have access to the original material, although they occasionally become collectable in their own right owing to instances of exceptional craftsmanship or rarity’.Footnote 1 In this sense, the history of music facsimile begins in 1868, when the newly invented technique of photolithography was used to produce facsimile editions of Handel's Messiah and Schubert's Der Erlkönig, in each case with an interest in bringing into public view the long-dead composer's conception of his celebrated masterwork.Footnote 2

But, as the Keepsake attests, music circulated in facsimile prior to the introduction of photo-mechanical printing techniques. The album belongs to another era of music facsimiles in which the first step was not to align the original document with a camera lens, but rather to cover it with paper and trace it by hand. The resulting tracing could then be mass-reproduced by means of lithography to yield prints that, by the 1820s, were known internationally by the Latin compound noun ‘fac-simile’.Footnote 3

For today's typical facsimile reader, the photographic method – with its ‘mechanical objectivity’ – guarantees fidelity to the original. A facsimile made by manual tracing sounds suspicious: the human hand introduces opportunities for interpretative selection, alteration and error.Footnote 4 Indeed, discrepancies of a sort foreign to photographic reproduction can be found in lithographic specimens. Consider one of the earliest examples of music in facsimile: that of Mozart's aria fragment ‘In te spero, o sposo amato’, which appeared in Georg Nikolaus von Nissen's Mozart biography of 1828. Rather than an exact copy of the original manuscript, the facsimile is a reformatted version: where the autograph has nine bars on the first line, the facsimile has only eight – a pattern of truncation by which subsequent lines become further and further displaced from the original (see Figures 2a–b). By this means, the facsimile preserved the size and shape of the original notes while fitting them onto a page of shorter dimensions. ‘Fac-simile’, such instances may remind us, comes from the Latin for ‘make similar’, not ‘make exact’ copy.

Figure 2a. Mozart's autograph of ‘In te spero’ in facsimile (20.5 × 25.5 cm). Georg Nikolaus von Nissen, Biographie W. A. Mozart's (Leipzig, 1828), facing p. 28.

Figure 2b. Photograph of Mozart's autograph of ‘In te spero’ (23 × 30 cm). Washington DC, Library of Congress, ML30.8b.M8 K.383 h (<http://lccn.loc.gov/2008560638>).

With such room for discrepancy between original and reproduction, we might wonder how lithographic facsimiles became valued material objects; to put the matter another way, we might ask what was being reproduced, and what produced. The pre-photographic era of facsimile-making was characterized not only by a different technical process, but also by different sorts of original texts, different ways of reading and different assumptions about the uses to which facsimiles would and could be put. To be collectable was a primary function of facsimiles, rather than the exception. They were also to be read with particular attention to the writer's character as betrayed by his handwriting. In the case of Nissen's Mozart biography, the facsimile supported a narrative of the composer's personal development – not by establishing chronology, as autographs are often used by modern musicologists to do, but rather by making visible Mozart's essential being. Nissen described verbally the dimensions of Mozart's note heads and flags as a youth, letting the facsimile provide this data for Mozart's mature hand. The handwriting comparison, in turn, amplified a discussion of Mozart's flowering as an individual and an artist. Whereas Mozart sacrificed happiness and life for art in his adulthood, according to Nissen, he ‘was less petulant in early childhood, not as intensely into art, not even consciously guided towards it, but rather was left to his own devices, even held back, until his singular nature irresistibly broke through and unmistakably made itself known’.Footnote 5 Nissen thus presented the autograph to be read not for compositional process, authorial intent or chronology, but rather for the ‘singular nature’ of the composer breaking through in the dimensions of his flags and note heads. As ideas about individual character and its manifestations came together with the hobby of collecting to fuel interest in autographs, facsimiles did more than ‘democratize’ access to precious documents. They altered the means available to composers to cultivate their public image, the ability of publishers to entice music consumers, and the opportunities to define interpretative communities – professional and amateur, reverent and irreverent – around musical texts.

Making facsimiles

While facsimiles came to adorn high-end musical publications, the technology that made them possible originated with a desire to print more cheaply. Lithography was invented in the 1790s by Alois Senefelder. By his own account, Senefelder entered the business of printing after facing delays and high costs in his efforts to publish as a dramatic author. Having little in the way of start-up finances, he experimented with various material means of etching and engraving. Limestone plates were cheaper than the standard copper or pewter, and childhood memories of seeing notes etched in stone at a local music printer's suggested that the material would make a suitable substitute. But it was in moving from the mechanical process of engraving to a chemical one – a move that involved the make-up of ink – that Senefelder invented a novel printing technique. Rather than relying on a raised or lowered surface to determine the distribution of ink, as in both letterpress and intaglio printing, lithography worked on the principle that oil and water repel one another. By writing on stone in oil-based ink and applying a water-based solution to the stone, one obtained a flat surface that would accept (oily) printing ink only where there was already writing. Running the inked stone together with paper through a press transferred the ink from the stone to the paper, and yielded an inverted print of the writing or drawing on the stone. Writing with ink on stone was less labour-intensive, and required less specialized skill and equipment, than engraving, making the process of lithographic printing quicker and easier. Senefelder foresaw special opportunities for his new method in music printing, and he built up his business with finances from the court composer Franz Gleissner, who was eager to have his compositions printed at high quality and low cost.

As an alternative to writing on stone, Senefelder described a method that involved writing with oil-based ink on paper, then transferring this writing from the paper to the stone. Calling this the ‘transfer’ or ‘tracing’ manner of lithography, Senefelder deemed it the most important part of his invention, for it eliminated the need for writing backwards and thereby put quick and cheap textual reproduction within reach of all writers. ‘In order to multiply copies of your ideas by printing,’ Senefelder explained, ‘it is no longer necessary to learn to write in an inverted sense; but every person who with common ink can write on paper, may do the same with chemical ink, and by the transfer of his writing to the stone, it can be multiplied ad infinitum.’Footnote 6 In addition to touting its use for copying routine communications in government and commerce, Senefelder predicted that the manner would give ‘new life’ to music printing by greatly reducing the cost of engraving. And although engraving continued to dominate music publishing into the 1860s, when the combination of lithography with the steam press increased reproduction speeds for high-volume jobs, transfer lithography did permit elaborate scores to be printed in small runs cost-effectively, making possible publications like the full score of Wagner's Tannhäuser (Dresden, 1845), which the composer wrote directly onto lithographic transfer paper for a run of only 30 copies.Footnote 7

The method of transfer lithography also facilitated the production of facsimiles. By using translucent paper, one could trace an existing document in greasy ink, then transfer the tracing from paper to stone for printing. One of the first books thus to apply lithography to the reproduction of text in its original appearance was J. C. F. Aretin's Ueber die frühesten universalhistorischen Folgen der Erfindung der Buchdruckerkunst, produced by Senefelder in 1808. This brief book, about the early history of printing and its revolutionary consequences, came with a ‘complete lithographic facsimile of the oldest known German print’ (a nine-page tract entitled Die Manung der Christenheit wider die Türken, dated by Aretin to 1454).Footnote 8 The new facsimile technique was thus quickly put to antiquarian and historical use, reproducing a text significant not so much for what it said as for the way it was printed (indeed, for the sheer fact that it was printed). From the facsimile one gained a feel for the past; and by comparing it to present-day print, one could see how the art had progressed.

Reading facsimiles

Another impetus to facsimile production came from a different mode of textual engagement – one less historicist, more physiognomic. An ancient art of discerning inner character from outward appearance, physiognomy gained new scientific and fashionable status in the 1770s thanks largely to the work of Johann Caspar Lavater.Footnote 9 Lavater famously discerned inner being in the features of the face, loading his publications with portraits and silhouettes which he interpreted for his readers – finding the craftiness of a knave in a long, somewhat pointed and prominent chin, for example, or the spirit of analysis and detail in the curvature from the eye to the back of the skull in profile.Footnote 10 But Lavater also identified handwriting as an outward record of inner states. ‘Isn't it true’, he added in the revised, French version of his earlier German work, ‘that the exterior form of a letter often leads us to make judgments about whether it was written in a calm or anxious state, in a hurry, or in a relaxed frame of mind? About whether the author is a solid or light man, a lively or heavy spirit?’Footnote 11 Lavater thus suggested extending physiognomic perception from faces to handwriting.

In Paris, Edouard Hocquart took up Lavater's suggestion, building upon the Swiss theologian's work to develop a physiognomical science of handwriting in his 1812 treatise L'art de juger du caractère des hommes sur leur écriture (The Art of Judging the Character of Men by their Handwriting). Like Lavater, Hocquart sought to know man's character, his inner nature, a pursuit made enormously difficult by the fact that its object had ‘no material existence’ and so was ‘imperceptible to the senses’.Footnote 12 But this immaterial, inner nature could be expressed outwardly through various media. According to Hocquart, men expressed their sentiments through verbal language, but there was also a ‘language of action’ (‘langage d'action’) made up of gestures; and while a person's words were under the control of the will, gestures often occurred involuntarily. As a result, words could be chosen to manipulate or deceive, but gestures carried ‘the imprint of truth’ (‘l'empreinte de la vérité’).Footnote 13 Handwriting, being a product of gestures, captured those unconscious movements that revealed the true character and passions of the writer. An ‘attentive and sagacious observer’ (‘observateur attentif, et doué de sagacité’) could thus learn to discern the character of a man from his handwriting, determining his essential nature in terms of qualities Hocquart helpfully broke down into binaries: vivacious or dull, impetuous or cautious, mild or obstinate, dexterous or awkward.Footnote 14

Like Lavater, too, Hocquart required not only visible features from which to read character, but also ones that were amenable to reproduction. To demonstrate their respective sciences to readers, both had to present their objects of analysis along with their analytical conclusions. For Lavater, a key technology was an apparatus for taking silhouettes, which he described in the second volume of his Physiognomische Fragmente (see Figure 3). With the aid of this apparatus, the silhouette became not a limited likeness, a blunt reduction of a detailed portrait, but rather ‘the truest and most faithful image that one can give of a person […] because it is an immediate imprint of nature, as none, even the most skilled drawer, is able to sketch freehand from nature’.Footnote 15 Lavater thus claimed for hand-tracing the same level of automatism that would later be claimed for photography. While the freehand artist could not help but put himself into his work, the one who traced a shadow imparted no qualities of himself; rather, he took the ‘immediate imprint of nature’.

Figure 3. Silhouette machine, from Johann Caspar Lavater, Physiognomische Fragmente zur Beförderung der Menschenkenntniss und Menschenliebe, 4 vols. (Leipzig, 1775–8), ii (1776), 93. Berkeley, CA, University of California Berkeley, The Bancroft Library, f BF843.L274 v. 2.

Transfer lithography offered the same level of automatism in the reproduction of handwriting. Hocquart insisted on the impossibility of handwriters concealing their character or feigning emotion – a trained eye would always detect those involuntary motions that betray the truth.Footnote 16 But Hocquart made no mention of the lithographic reproduction process; the accuracy of its tracing method was tacitly assumed. The bulk of Hocquart's treatise consisted of facsimiles of different hands.Footnote 17 More than 30 were included, each accompanied by Hocquart's judgment of the writer's character (see Figure 4). In no. 27, for instance, one is to see that ‘clarity and method’ (‘la clarté et la méthode’) are painted in Condillac's handwriting, while in the more scrawling hand of no. 28 one is to recognize not impatience to finish but rather Pascal's vivacity of spirit and great originality. Through careful observation, the reader could learn to detect such qualities in the incidental movements of the writer's hand – the fleeting language of action captured in enduring form on the page.

Figure 4. Facsimiles of handwriting and their analysis, from Edouard Hocquart, L'art de juger du caractère des hommes sur leur écriture (Paris, 1812). Philadelphia, PA, University of Pennsylvania Libraries, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, BF892.H63 1816.

Like physiognomy, handwriting analysis struck later generations (and indeed some contemporaries) as scientifically dubious. The posited relationship between exterior sign and inner being failed to hold up under rigorous standards of empiricism.Footnote 18 But it is important to recognize that while some devotees held out hope for a complete science, a reading technique that would render character perfectly legible, in general practice neither the face nor the autograph alone disclosed all. Rather, character was to be triangulated from a person's face, his handwriting and his life. As Hocquart observed, it was the ‘necessity of the most perfect harmony in all the movements of the physiognomy’ that assured that true character could be discerned, and efforts at disguise identified as such.Footnote 19 This notion of harmony underwrites the ‘basic physiognomic hypothesis’ identified by Ernst Gombrich: that ‘of a unified character behind all the manifestations we register’.Footnote 20 In the case of composers, the harmonious manifestations of character included not only portraits, autographs and biographies, but also musical compositions.

Collecting facsimiles

Knowing no difference between original and reproduction, physiognomic perception was crucial to the collectability of facsimiles. Conversely, collecting was crucial to physiognomic perception, the individuality of each specimen becoming apparent through comparison with many others. From the 1820s, large numbers of autographs were reproduced in facsimile. Many were published in massive collections, which featured either signature–portrait pairings or autograph letters.Footnote 21 These publications featured a diverse set of extraordinary individuals, historical and contemporary, considered to be of general interest. As the Iconographie française – a volume of 200 portraits and facsimile signatures first published in 1828 – explained in its lengthy subtitle (see note 21), its subjects had attained ‘the greatest celebrity in the government, the church, the military, the sciences, the letters or the arts, or else by their intrigues, their virtues, their beauty or their faults’. This list sums up the types of people who had their handwriting reproduced in facsimile in the nineteenth century, and points to the biographical interests – in virtues and faults, intrigues and achievements – that supported portrait and autograph collecting. Other forms of publication left the act of collecting to consumers: books about particular celebrated individuals were often ‘ornamented’ by a facsimile of the person's signature together with his or her portrait.Footnote 22 The pairing reflects the dual function of portraits and autographs as both attractive illustrations and visible traces of character; while they might remain in the ornamental position of frontispiece, they could also be cut out and resituated in a collection.

Those who collected musicians’ autographs did so either along with those of other celebrities or as a specialized interest. As Annette Richards has shown, a number of late eighteenth-century figures undertook portrait collecting with a particular focus on music, amassing galleries conceived at once as ‘temples of worthies’ – that is, of exemplary masters to be admired from a distance – and ‘temples of friendship’, filled with the likenesses of musicians known personally by the collector, and able to refresh feelings of affection and intimacy.Footnote 23 Both logics were also at work in musical autograph collecting, with one or the other usually taking the upper hand for any individual collector. But facsimile autographs differed from portraits, for behind the former was not just a person – something impossible to possess – but an original autograph. Coming straight from the hand of the composer, the original autograph participated in musical life in a different way from the portrait, having a direct role in the composer's social interactions, and potentially in the very coming into being of his compositions.

One of the first self-identifying collectors of original musical autographs was Aloys Fuchs of Vienna. A bureaucrat trained in philosophy and law as well as a singer and an author of musical biographies and catalogues, Fuchs began to collect musical autographs around 1820. In 1829, the Revue musicale alerted readers to his ‘very interesting’ musical autograph collection, and suggested (spuriously) that he would sell it to anyone willing to publish its more curious items, especially in facsimile.Footnote 24 Fuchs in fact remained committed to growing his collection, and to showing it to any serious music lovers who cared to pay him a visit.Footnote 25 By 1832 Fuchs possessed more than 500 composers’ autographs, and by 1844 more than 1,000.Footnote 26 These formed part of his larger music library of early printed editions, music theoretical treatises and musicians’ portraits. With them, he aimed to establish a comprehensive collection of the notational writing of celebrated composers (his focus was on composers and their works, rather than on musicians more generally) from all eras and countries. A laudatory Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung article on Fuchs's autograph collection by fellow bureaucrat-cum-music-historian Raphael Georg Kiesewetter attributed multiple values to musical autographs – a familiar set in keeping with the temples of worthies and friendship, and a more novel set unique to autographs: ‘The handwriting of famous men is in and of itself highly pleasing and edifying; it can also even be historically significant and many a doubt as to the authenticity of a questionable composition can be resolved by comparison.’Footnote 27

The use of autographs to establish a composition's authenticity – clearly an exceptional use in Kiesewetter's mind – had received recent impetus from a controversy over Mozart's Requiem. Unfolding over several years, the controversy began in 1825 when Gottfried Weber proposed that the Requiem published by Breitkopf & Härtel in 1800 as Mozart's was in fact almost entirely by Franz Xavier Süssmayr.Footnote 28 Weber's contention was roundly attacked by, among others, Abbé Maximilian Stadler, who based his rebuttal largely on Mozart's autographs. In helping Constanze organize her deceased husband's manuscripts, Stadler claimed, he acquired ‘the most exact knowledge possible of Mozart's handwriting, which remained the same until his death’. He could thus attest that, with only minor exceptions, the first three movements ‘all flowed entirely from Mozart's hand’.Footnote 29

The Mozart controversy occasioned reflection not only on the potential use of autographs to establish the true authorship and musical text behind printed editions, but also on the making of facsimiles. Weber sought to publish facsimiles of the Requiem autograph sources in his journal, Cäcilia, but to no avail. While facsimiles of the autograph sources held obvious relevance to the debate, none were produced. Stadler suggests the reason: such autographs were too precious to submit to lithographic reproduction – especially by someone lacking proper reverence for the music represented therein. ‘Nothing would be easier than to arrange for a facsimile in this city where there are so many lithographic printers,’ Stadler observed, ‘but to entrust the task to Cäcilia, of all things, seems most inadvisable, since the work is so lamentably misrepresented and denigrated in its pages. The celebrated Leipzig Musikzeitung would be a far more suitable place for it, for that has always given Mozart's Requiem the praise it deserves.’ Yet even entrusting Requiem autographs to the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung seemed a dubious proposition. ‘Who can blame the fortunate owner if he will not allow it to leave his hands?’ Stadler wrote. ‘How many own Mozart's original manuscripts, and preserve them carefully, like a precious treasure!’ Rather than make facsimiles, Stadler suggested that the manuscripts be deposited ‘in a place where they will be preserved for study by those who know and admire Mozart, with as much care as a valuable, albeit uncopied, painting by Raphael in a public gallery’.Footnote 30 The analogy is significant, figuring the musical autograph – the text in the composer's hand – as the original work of art, next to which both print editions and performances are reduced to interpretations. Stadler himself deposited the Requiem autograph fragment that came into his possession in 1826 (the Sequence to the Confutatis) with the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, in 1828 or 1829, while lending out other, less music-textually significant (and hence also less one-of-a-kind, more interchangeable) autographs to be reproduced in lithographic facsimile.Footnote 31

Despite the example set by Fuchs and the high-profile debate over Mozart's Requiem, musical autograph collecting in the era of transfer lithography rarely had to do with getting at the authentic texts of musical works. Instead, it had to do with getting at the person behind the music. The primary way to collect musicians’ autographs was in albums (although especially prized autographs perhaps might be framed and hung on a wall, as the Baron de Trémont did with his Beethoven letter).Footnote 32 Albums typically had a more personal than a universal flavour, the autographs being valued first as souvenirs, and perhaps secondarily as historical documents. Most albums of this kind were dispersed after their collector's death, individual items going on to fill gaps in other collectors’ albums. A few, however, have been preserved largely as their collectors left them, and from these we can gain some sense of mid-nineteenth-century musical autograph collecting. The London music publisher Vincent Novello began to collect autographs in 1829, when he journeyed to Austria to visit Mozart's widow and gather material for a Mozart biography (which he never wrote, though his materials were used by the Mozart biographer Edward Holmes). The musical items in his album, collected through the 1840s, followed from his personal contacts with musicians and musical gatherings hosted at his home, or else were gifts passed on to him by others personally acquainted with the composers (as in the case of his Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven autographs).Footnote 33 Gustave Vogt, principal oboist of the Paris Opéra, collected autographs from 1840 to 1856 (most avidly from 1842 to 1844), amassing 63 specimens from his musical associates in Paris.Footnote 34 Musicians were among a variety of celebrities that interested the Baron de Trémont, who collected autographs from 1840 to 1850. Trémont hosted musical gatherings at his home, and the invited musicians often left a handwritten memento. Trémont's album blended the personal and the historical: along with autographs he also collected articles from the RGM, and added his own biographical essays and notes.Footnote 35 Female collectors are egregiously absent from the surviving sample held by libraries – a fact which, to judge from the couple of musical autograph albums of women that have turned up in private hands, has little to do with differences in the people or the kinds of texts they pursued.Footnote 36 Traces of female collectors’ activities survive more copiously in other ways – in the many autographs inscribed to female recipients, and in the letters seeking them. For instance, when writing to Mendelssohn about a commission, Charles Bayles Broadley took the opportunity to request, ‘if it be not intruding too much on your kindness … a few bars of Music with your signature on a small piece of paper (about the size of this note) to be inserted in a Lady's manuscript-Book of musical Autographs’.Footnote 37

Facsimiles made the collecting activities of aristocrats, music professionals and their associates available to those without the same social connections. But it was not only those without access to original autographs who collected handwriting in reproduction. Chopin, for example, collected both original autographs and facsimiles. He received an original Beethoven autograph from Fuchs when he visited his collection in 1831, and preserved souvenir autographs (with and without music) written expressly for him by the likes of Leopold Eustachius Czapek, Ferdinand Hiller and Mendelssohn.Footnote 38 Additionally, he kept a number of facsimiles published in the RGM between 1836 and 1844, among them Luigi Cherubini's corrections to his Cours de contrepoint et de fugue, letters between Paganini and Berlioz, and a set of 300 musicians’ signatures.Footnote 39 Like original autographs in this period, these facsimiles circulated as ‘gifts’: the RGM did not sell them individually, but rather presented them as extras for subscribers. The journal's masthead regularly included facsimiles in the list of things to be ‘given’ to subscribers during the year.Footnote 40 As the journal promised when heading into its seventh year (1840), facsimiles – like portraits and concerts – were ‘interesting accessories’ that would ‘continue to be for us the object of most special care’.Footnote 41

Together with the steady supply of facsimiles, the RGM also offered subscribers reflections on their value. When it published a ‘Nicolai Piccini’ (sic) letter in facsimile in 1839, for example, a front-page article expounded on handwriting as a ‘kind of mirror’ of the character of famous men, and on the resulting ‘use and usefulness of the collecting of autographs’ – any difference between collecting original and facsimile autographs notably elided.Footnote 42 Further evidence that subscribers collected the journal's facsimiles comes from a binder's volume from the period, now held by the University of Pennsylvania Rare Book and Manuscript Library, in which an unknown music consumer preserved two autograph letters in facsimile, along with the Keepsake des pianistes and other musical supplements to the RGM.Footnote 43 In this subscriber's view, printed texts were disposable; printed music and facsimiles, however, were worth keeping.

The RGM twice (in 1838 and 1844) published supplements consisting of hundreds of signatures of celebrated musicians, mostly composers but also performers such as the singer Maria Malibran (see Figure 5). These pages mimicked those found in albums of original autographs (including Novello's), where each signature had to be obtained individually (usually they were cut from letters), and part of the appeal lay in the pleasure of the hunt. The ready-made collections would thus seem a poor substitute, short-cutting the process of collecting, evacuating the sense of accomplishment to be derived from it, and presenting the fruits of autograph collecting at its least historically minded, its most celebrity-hounding. Yet there was more to the signature collection. A notice accompanying the 1838 set suggested that with them the reader – or perhaps better, given the leading metaphor, the viewer – would ‘browse a sort of biographical gallery’, which was also to unfold week by week through articles about the main events in the artists’ lives, and with an eye to appreciating the nature of their talents and the value of their works.Footnote 44 The notice accompanying the signatures in 1844 placed greater emphasis on their revelatory power, advancing what it declared to be a new dictum: ‘Let's see how you sign your name, and I'll tell you who you are.’Footnote 45 Like Hocquart, the anonymous author of this article held that one learnt to discern character essentials from handwriting through careful study, and deciphered character in terms of binaries such as calm or violent, modest or ambitious. Yet at the same time, the musicians’ signatures were said to be a ‘necessary supplement to all the stories, to all the biographies, to all the notices relating to those same artists; it is the indispensable appendage to all their most lifelike portraits’.Footnote 46 Signatures were thus both sources and indexes of information: they could be analysed for their signers’ essential being and used to point to biographical knowledge acquired otherwise (including from other issues of the journal). These facsimile pages thus constituted not so much an instant autograph collection as an invitation to further gathering – of portraits, biographies and music.

Figure 5. Facsimiles of musicians’ signatures, Revue et gazette musicale, 5/27 (8 July 1838), supplement, first of four pages. RIPM Online Archive (<http://www.ripmfulltext.org/RIPM/Source/ImageLinks/1107219>).

Music in facsimile

Whereas the alphabetic writings of musicians could be read in the same manner as those of any other celebrities, music notation raised special considerations; for while words were assumed to represent conscious thought, such was not the case for music. In a distinction commonly drawn since the mid-eighteenth century, words were a medium of reason whereas tones and gestures alike were media of the heart.Footnote 47 In nineteenth-century terms, the languages of gesture and of tones were less governed by the will and so closer to a person's authentic character and passions: both handwriting and music bypassed words to give true impressions of inner being.Footnote 48

Yet seeing tones in handwriting opened up the possibility of discovering discrepancies between the two media – if the reader was equipped to detect them. François-Joseph Fétis recognized this in an announcement for a special publication entitled ‘Gallery of Celebrated Musicians’, to be made up of portraits, facsimiles and biographies.Footnote 49 Musical autographs in facsimile had great value, Fétis explained, but the nature of that value depended on the reader. For an average person, music facsimiles satisfied a certain curiosity, as did alphabetic facsimiles. For an artist, by contrast, music facsimiles could grant insight into the composer's artistic process. They could reveal, for instance, the composer's hesitation or confidence in the creation of a work. Significantly, Fétis observed that the evidence of the handwriting might contradict the impression of spontaneity or careful reflection given by the music.Footnote 50 In such cases, Fétis suggested, handwriting represented the more reliable testimony to compositional process.

While Fétis presented the different ways of appreciating musical autographs as determined by the reader, modes of facsimile reading also depended on the kinds of musical texts reproduced and on their biographical framing. A morbid curiosity surrounded some of the earliest musical autographs selected for facsimile reproduction. Shortly after Beethoven's death, Schlesinger advertised his complete edition of Beethoven's string trios, quartets and quintets as including ‘a facsimile taken from Beethoven's last work, the seventeenth quartet’, by which he meant op. 135.Footnote 51 The chosen page – the first-violin part of the Lento assai, cantante e tranquillo – features a suitably reflective and sentimental melody, the heart-tugging power of which only gains from imagining it to come from a man on his deathbed. Around the same time, Novello tried to persuade Johann Edler von Eybler – who possessed a partial manuscript of Mozart's Requiem – to have a facsimile made of what he evocatively described as ‘the last Page which Mozart wrote before the pen dropped from his weak hand’. Novello's concern was not with clarifying the Requiem's authorship for the public, but rather with the same sort of curiosity as that tapped by Schlesinger's Beethoven facsimile: ‘This would be [a] most interesting engraving’, Novello added, ‘to all lovers of Mozart.’Footnote 52 What made these autographs interesting was their connection to a poignant point in the composer's life, their record of the body in the last moments of its being inhabited by a soul. A facsimile promised a faithful trace of those final gestures.

For the mere purposes of collecting, or for lending a sense of uniqueness and intimacy to mass-produced publications, the nature of the music autographs reproduced in facsimile would seem immaterial. Such might explain the eclectic set of five facsimiles that appeared in Apollo's Gift, or the Musical Souvenir, a musical annual for the year 1829 produced collaboratively by three music publishers in London: Chappell, Muzio Clementi and J. B. Cramer.Footnote 53 The five facsimiles represent a veritable catalogue of autographic possibilities: Weber's ‘first sketches’ for Oberon exemplify a working document of the compositional process; Mozart's ‘Andantino für Clavier’, from André's collection of Mozart autographs, supplies an unpublished work; Clementi's Canon ed diapason for piano ‘composed and dedicated to J. B. Cramer by his friend’ and Haydn's three-part ‘puzzle’ canon to be read the right way up and upside down represent the kinds of autographs composers regularly supplied for the albums of friends and acquaintances; and the opening bars of the Andante from Beethoven's Piano Sonata op. 79 came from the autograph sent by the composer to Clementi in order to have the work published in London. If most readers saw these as equivalent objects of curiosity for their collections, the assembly of reproductions also allowed them to become matters of public discourse, wherein critics responded to differences not only in the musical hands (Beethoven's being found ‘the most singular we ever beheld’) but also in the nature of the musical texts.Footnote 54 Weber's sample, for example, showed ‘the germ of his original’ musical conception, while Mozart's raised questions about whether the unpublished composition constituted a legitimate work by Mozart or a derivative exercise.Footnote 55

Canons were especially abundant in musical autographs, for composers often chose to write canons for the express purpose of giving a musical souvenir to friends or new acquaintances. With their ability to generate multi-voice harmony from a single line of music, canons had a visual dimension and spatial economy that no doubt contributed to their appeal for autographic purposes. But more than this: since the strict contrapuntal procedures epitomized by canons had largely fallen out of public favour during the eighteenth century, and canons were vanishingly rare in printed music in the first half of the nineteenth century, their circulation in autograph defined an inner circle of intimacy and friendship within musical culture. Canons demonstrated compositional skill, but of a sort allied with learning and craftsmanship at odds with the inborn talent and inspiration prized by Romantics. To make a gift of an autograph canon was thus to disclose the practised mastery behind the public face of musical genius. As albums were often shown to visitors, Luciane Beduschi has suggested that puzzle canons additionally created a form of private communication between composer and recipient, a musical message not to be deciphered by the casual interloper.Footnote 56

Facsimiles meant that the privacy once assumed for autographic gifts was no longer certain – a fact that some composers greeted with enthusiasm. One of the first facsimiles to appear in the Gazette musicale was, in fact, an ‘enigmatic canon’ composed by Henri-Montan Berton for the album of his ‘illustrious friend’ and fellow composer Cherubini. Berton sent the canon to the Gazette in its first year, 1834, along with a letter in which he explained that the canon, as a type of piece, held little importance, but had the merit of being a species of witty composition (‘jeux d'esprit’). Since the Gazette set out to treat ‘all questions that relate to the culture of musical art’, Berton thought his canon for Cherubini's album would have a place in its pages. He recommended that the puzzle canon appear in one issue, and its solution in a following issue.Footnote 57 This recommendation was followed. But surprisingly, Berton's single-line, enigmatic version of the canon – the version designed for Cherubini's album – appeared in print, while his written-out solution to the canon – a writing specimen that would have no place in a traditional album – appeared in facsimile (see Figures 6a–b). Perhaps Berton and the Gazette were less interested in collapsing than they were in maintaining, or even revealing, a distance between composers’ private and public communications. Another reason for this particular facsimile production is suggested by the note included in Berton's hand: ‘Dear Maurice, here is the key to my canonic enigma, that is to say, the witty musical conversation written in score. You can do with it what seems suitable to you.’Footnote 58 The marginal inscription might easily have been omitted, obviating the need for the extra-long paper on which the facsimile was printed (and in fact the note has been omitted, entirely or in part, from microfilm and digital reproductions of the page).Footnote 59 But the inscription was significant, for it branded the facsimile with both an expression of affection between composer and publisher and the licence to reproduce it.

Figure 6a. Berton's puzzle canon, composed for Cherubini's album, Gazette musicale, 1/37 (14 September 1834), 298. RIPM Online Archive (<http://www.ripmfulltext.org/RIPM/Source/ImageLinks/1562401>).

Figure 6b. Solution to Berton's puzzle canon, Gazette musicale, 1/38 (21 September 1834), [308]. Boston, MA, Boston Public Library, Arts Department, ML5.R51.

Another canon facsimile that appeared in an early issue of the Gazette came from its recipient rather than its author: Fromental Halévy – a student of Cherubini who collaborated with his teacher on the Cours de contrepoint et de fugue (1835) – offered to the public a facsimile of three canons by Cherubini (see Figure 7). In a preface to the facsimile, Halévy marvelled at the canon's contradiction between apparently inspired melody and underlying compositional process: ‘It is impossible to believe, reading this theme, that it is not the result of a spontaneous inspiration, yet it required Cherubini to calculate each phrase note by note.’ The look of Cherubini's notation – neat, orderly, even dainty – suggests no rush to capture spontaneous inspiration; on the contrary, it seems to have been carefully penned. Halévy's assessment focused on the text, not the handwriting, a point reiterated when he instructed that ‘one considers the charm of these canons by reading the three that make up the facsimile’ (emphasis added).Footnote 60 From these remarks, the reproduction of the canons in facsimile seems gratuitous, delivering the notes where print would do equally well.

Figure 7. Facsimile of autograph canons by Cherubini gifted to Fromental Halévy, Gazette musicale, 1/10 (9 March 1834), supplement. RIPM Online Archive (<http://www.ripmfulltext.org/RIPM/Source/ImageLinks/1561840>).

But the facsimile did present more than a musical text. For again, the musical autograph bore traces of the composer's social life: it was written for a particular individual to whom it was given as a gift. As Halévy explained, the canons were written out by Cherubini specifically for him, and he had ‘long resisted in proceedings with the editor of the Gazette musicale prior to consenting to publish a fac simile’. Since Cherubini had approved the publication, however, Halévy hoped readers would ‘forgive him for having made public this testimony of the friendship of a great man’.Footnote 61 Sensitive to the potential impropriety of publishing Cherubini's gift, Halévy recognized the music facsimile as exposing the composer's private life as well as providing evidence of his friendship.

With these facsimiles of musical autographs we see composers’ handwriting becoming part of their public image. We also see a gap opening up between autographs and their copies. Whereas other modes of apprehending facsimiles minimized the difference between original and reproduction (both preserved exterior traces of inner being), the autograph as testimony of friendship emphasized the difference, the non-transferable social relationship that inhered in the original artefact. Facsimiles like Cherubini's gift allowed people to collect the testaments of friendships – the souvenirs of experiences they never had.

Yet even if facsimiles seem like poor surrogates for participation in the inner circles of musical life, their collectors bought into a social world. To become a subscriber to the RGM was to become a member of a community of readers, affiliated with a certain cadre of writers and composers some of whom – as the Halévy and Cherubini facsimiles attested – could call each other friends. Music publishers could thus use facsimiles selectively, strategically to expose the social relationships behind their mass-produced commodities – as Schlesinger and Eugène-Théodore Troupenas did around 1840 in presenting to the public new works by Rossini.

The case of Rossini's waltz

Rossini's waltz, the facsimile with which we began, appeared in the Keepsake des pianistes published at the end of 1841 for subscribers to the RGM. The main events surrounding the publication of this facsimile are chronicled in Table 1, and they trace a tale of marketplace competition, music publishers’ machinations and legal disputes. The Keepsake was first announced in a July issue of the RGM as part of a new suite of incentivizing gifts for subscribers, who could look forward to receiving in November the collection of previously unpublished piano pieces by Chopin, Kalkbrenner, Liszt and others, ‘with facsimiles of their handwriting’.Footnote 62 This phrase was by now routine, a part of the RGM's standing practice of enriching both their weekly issues and special publications with facsimiles, to be appreciated as objects of curiosity, mirrors of character and collectables. The RGM continued to advertise the Keepsake ‘with facsimiles of [the composers’] handwriting’ for nearly three months, until 3 October 1841.

TABLE 1 events leading to and following the publication of rossini's waltz in facsimile

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 18 July 1841 | RGM ad.: ‘Le 15 Novembre; Keepsake des Pianistes / Morceaux nouveaux et inédits Par MM. Chopin, Doehler, Henselt, Kalkbrenner, Liszt, Osbourne, Rosenhain, E. Wolff / Avec fac-simile de leur écriture’. RGM Keepsake ads. continue, with added composers (St Heller, Méreaux, Mendelssohn, Moscheles) to 3 Oct. 1841. |

| Sept. 1841 | Aulagnier contacts Rossini about publishing Stabat mater acquired from the estate of its deceased dedicatee, Varela of Spain. Rossini refuses Aulagnier and forms agreement with Troupenas to publish Stabat mater, with newly composed movements, for payment of 6,000 francs. |

| 10 Oct. 1841 | FM announces publication of Rossini's Stabat mater, accompanied by facsimile of letter from Rossini to Troupenas regarding same. |

| 17 Oct. 1841 | RGM Keepsake ad.: ‘Avec fac-simile de leur écriture’ replaced by ‘Et une Valse de Rossini en fac-simile de son écriture’. |

| 24 Oct. 1841 | RGM article attacking Troupenas's Stabat mater. |

| 31 Oct. 1841 | FM response to RGM attack. |

| Dec. 1841 | Publication of Keepsake des pianistes, ‘orné du Fac simile d'une Valse de Rossini’. |

| Jan. 1842 | Troupenas wins Stabat mater court case. |

| Jan. 1843 | Troupenas wins waltz court case. |

Abbreviations

RGM Revue et gazette musicale

FM La France musicale

Plans for the Keepsake changed, however, after La France musicale (FM) announced on its front page a new work by Rossini, to be published by Troupenas. As the unnamed author of the announcement observed, this news was sure to produce ‘a great sensation in the musical word’.Footnote 63 While any announcement concerning Rossini would pique public interest, the publication of a new work was especially significant, for Rossini had brought forth no large-scale works since Guillaume Tell in 1829, and his disappearance from the public eye had come to seem a permanent retirement. The forthcoming work was to be a Stabat mater, raising the question of how the master of the operatic stage would meet the demands of sacred music. Here, Rossini's compositional hiatus could be spun to advantage: while he had devoted himself to teaching in Bologna, the FM reported, Rossini had been ‘able completely to strip the dramatic style’ found in Guillaume Tell, making the Stabat mater ‘the product of a new transformation: it is the third way of Rossini, it is the transfiguration of the Raphael of music’.Footnote 64 Music lovers should not expect more of the same from the master of melody, but something better.

Not only was the FM interested in generating excitement about the new Rossini work, but also it was concerned to demonstrate the authenticity and legitimacy of its announcement. Much of the text was given over to establishing its own credibility. Readers of the FM were told to have confidence in the announcement, which had nothing in common with those of ‘speculators’. Troupenas, far from being such a dubious profit-seeker, was described as both a business associate and a close intimate of Rossini. Identified on one occasion as Rossini's ‘editor’, he was repeatedly called his ‘friend’. The FM offered hard evidence for such claims in the form of a facsimile of a letter from Rossini to Troupenas.Footnote 65 In the published extract, the composer complained that he often read promises of new Rossini compositions in the newspapers, but since he ‘had not made anything for anyone’ he asked Troupenas to do what he could to prevent his ‘very respectable’ (‘fort respectable’; in other words, valuable) name being thus used to deceive the public.Footnote 66 The text of the letter also confirmed the intimacy between Troupenas and Rossini: Rossini closed with the regret that ill health ‘prevents me from going to kiss you’ and the sign-off ‘your affectionate, G. Rossini’.Footnote 67 Rossini's signature, meanwhile, was said to be certified by Francesco Guidotti, senator of Bologna, and by another government official.Footnote 68 The facsimile was thus not offered as an ornament, a collectable or a mirror of character, but first and foremost to verify a printed text, in which it was all too easy to lie or mislead. Troupenas was Rossini's sole authorized publisher, and their relationship was grounded in friendship – the proof was in the composer's hand.

The week following the FM announcement, the RGM revised its advertisement for the Keepsake from ‘with facsimiles of their handwriting’ to ‘and a waltz by Rossini in facsimile of his handwriting’.Footnote 69 Thus began a campaign in the pages of the RGM against Troupenas's publication of Rossini's Stabat mater, which soon spilled over into multiple lawsuits over publication rights to Rossini's music. The particular interests behind the production, and contexts for the reception, of the Rossini waltz facsimile thus made it far more than an ‘ornament’ to the Keepsake. The facsimile provoked new adjudications – both popular and legal – with regard to the meaning of composers’ handwriting and the value of gift manuscripts within a commercial economy under the conditions of mass reproduction.

To understand the Rossini dispute, we must go back ten years to a time shortly after Rossini's departure from the opera houses of Paris. In 1831, the Spanish archdeacon Manuel Fernández Varela, a friend of a friend of Rossini, asked the composer to write a Stabat mater. Suffering from illness, Rossini had completed only half the work by the following spring, and he asked the composer and director at the Théâtre-Italien in Paris, Giovanni Tadolini, to complete the remaining movements. The resulting Stabat mater was performed once, on Good Friday 1833 in Madrid. Thereafter, at Rossini's request, it remained unperformed and unpublished – the manuscript a silent but cherished object among Varela's possessions.Footnote 70

After Varela's death in 1837, however, his possessions were put up for sale. In 1841, the Parisian publisher Antoine Aulagnier acquired the Stabat mater with the intention of publishing it together with Schlesinger. When Aulagnier notified Rossini about his plans (accounts differ as to whether he asked permission to publish, or simply asked if Rossini wished to supervise the publication), Rossini objected.Footnote 71 To prevent the unwanted publication of his joint composition with Tadolini, he turned to Troupenas with the offer of a revised Stabat mater, composed completely by himself.

Against this background, the RGM notice of Rossini's waltz in facsimile thus seems a direct response to the FM announcement of the Stabat mater and its publication of Rossini's letter in facsimile – a deliberate challenge to Troupenas's claims, calculated to establish an alternative set of facts in the eyes of the public. By printing the waltz in facsimile, Schlesinger not only furnished the Keepsake des pianistes with a fitting, ornamental frontispiece, but he also claimed for his firm a new Rossini composition authenticated by the composer's handwriting, in contradiction to Rossini's statement that he ‘had not made anything for anyone’.

When the facsimile appeared in the Keepsake in December, Rossini's intended recipient of the waltz was, significantly, not evident (see Figure 8). The original autograph from which the Keepsake facsimile was made does not survive, but two versions of the waltz in Rossini's hand do. Each bears a dedication to an upper-class woman: ‘Alla carissima Eugenia Puerati il Suo candido estimatore’ and ‘Alla Sig.ra Elena Bandieranata Ricci’.Footnote 72 In all likelihood, the autograph of the Keepsake facsimile likewise bore a dedication, which the lithographer intentionally failed to trace. By suppressing the dedication, the Keepsake facsimile depersonalized Rossini's manuscript, making the musical text appear intended for the public.

Figure 8. Autograph of Rossini's Waltz, Keepsake des pianistes (1841), frontispiece. Philadelphia, PA, University of Pennsylvania Libraries, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, M1.K33 1839.

How the reading public might have interpreted the Rossini facsimile is suggested by Henri Blanchard, who reviewed the Keepsake for the RGM. Blanchard, it must be said, was hardly an unbiased reviewer. As a regular contributor to the RGM, he had already participated in the Rossini war by writing a review of the Stabat mater based on the score held by Aulagnier before Troupenas's was available.Footnote 73 In his review of the Keepsake, one can see Blanchard trying to have it two ways at once: preserving the value of the facsimile for owners of the Keepsake, while also using it to discredit Rossini. To the former end, he observed that ‘this musical spark in facsimile of the great composer opens the volume’; to the latter, he wrote that ‘[Rossini] is represented in the compilation by a lovely waltz which he undoubtedly gave to the first comer as one might offer a plug of tobacco, and to which, presumably, the master does not attach much greater importance’.Footnote 74 This facsimile – in keeping with its absent dedication – was not to be seen as a testimony of friendship between two individuals but as a product of merely mercantile exchanges (however ‘great’ the composer might be).

The tobacco remark referred directly to the legal case that Troupenas brought against Aulagnier and Schlesinger with regard to the copyright of the Stabat mater. At issue was whether Rossini had sold the Stabat mater to Varela, or had only dedicated the composition to him as a gift. In the former case, the Stabat mater became Varela's property and Rossini had no legal standing to halt its publication. In the latter, rights to the work remained with Rossini, and his consent was required for publication. Varela had given Rossini a snuffbox (worth 10,000 francs according to Schlesinger, but no more than 1,500 francs according to Troupenas) for the composition, and the case hinged on whether this snuffbox constituted a form of payment or a token of thanks.Footnote 75 On 28 January 1842, the case was decided in Troupenas's favour: Rossini's right to dispose of his work as he saw fit was upheld, and Aulagnier and Schlesinger were left with only the portions of the Stabat mater composed by Tadolini.

Matters did not end there, however, for Troupenas also took Schlesinger to court over the publication of Rossini's waltz in the Keepsake des pianistes. In this case, Schlesinger argued that Rossini had written the waltz for the album of a princess who then shared the waltz with the public. Because this occurred in Germany, and copyright protections did not extend internationally, the waltz was in the public domain in France. Rossini's argument, once again, was that he had given the waltz as a gift and did not want it to be published.Footnote 76

The court ruled in Rossini's favour, finding that the supposed prior publication of the gift manuscript in Germany – in the form of a facsimile by Schlesinger of Berlin, brother of the Parisian publisher – had not been authorized by Rossini and so took place in violation of the composer's rights. The resulting ruling clarified the imperative to protect composers’ private writings: ‘One does not have the right to dispose of a work that was written on the basis of intimacy, and which was given as a souvenir; it is an infringement of the author's property to deliver to the public ideas he may have intended to use later; it is an infringement of his reputation to issue test-pieces to which he attached perhaps no importance.’Footnote 77 The technical means of and commercial drives to reproduction posed a mounting threat to works ‘written on the basis of intimacy’. These were often pieces that would hold little interest for the public appearing under the regular conditions of print, but that became fascinating when reproduced in the composer's hand, with its traces of individual character and social life.

Fascination with composers’ handwriting has persisted, even as other reasons for valuing autographs and their facsimiles have come to the fore. A turn from handwriting to musical text can be dated to the 1860s, the impetus coming from the interests of a growing community of music scholars. In his pioneering publication on Beethoven's sketches (1865), Gustav Nottebohm offered not facsimiles but diplomatic transcriptions: it was the musical text that revealed how the composer ‘began a piece, advanced step by step, stopped short, modified, combined, developed, etc. – and how he proceeded in various stages from the initial conception to the final product’.Footnote 78 Beethoven's notoriously ‘individual’ handwriting (to recall the Atlas's characterization) constituted a barrier to be overcome and – by means of transcription – removed for the reading public. Modern facsimile editions likewise emphasize the importance of the musical text, but justify its reproduction in the composer's handwriting by invoking the superior conveyance of the composer's intentions. For example, the introduction to a recent facsimile edition of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony notes that ‘this working autograph represents a highly organized document, imparting the musical text intended by the composer with great, sometimes even pedantic precision’, while a preface to a facsimile of Dvořák's G minor Piano Concerto proclaims: ‘Let us forget [the revisions to the piano part by Vilém] Kurz and return to the original, exactly as Dvořák composed it.’Footnote 79

The turn from handwriting to text represents less a transformation in reading practices than a divergence of interpretative communities and a reordering of the hierarchy of motivations for reproducing music in facsimile. Both of these phenomena are reflected in a 2006 New York Times article on music manuscripts at the Morgan Library, which music critic Anthony Tommasini began with the observation: ‘Autograph manuscripts by master composers are, naturally, invaluable resources for music scholars and specialists.’ Tommasini, however, found himself ‘struck more by what [an autograph] reveals about the character of its […] composer. And this is something that all music lovers, not just specialists, can glean from seeing the score.’ Going further, he suggested that autographs are in fact of dubious value as documents of compositional intention, often reflecting earlier versions of works superseded in the publication process; but ‘what always comes through in an autograph manuscript is the personality of the composer’.Footnote 80

Like nineteenth-century readers, Tommasini discovered meaningful harmony between composers’ personalities, handwriting and music. He gave Grieg as one example: ‘Grieg was a generous soul and an accessible composer, qualities reflected in his manuscript, which is readable, open and unpretentious.’Footnote 81 Similarly, Friedrich Chrysander, reviewing the photolithographic facsimile of Schubert's Erlkönig produced in 1868, noted that ‘Schubert's handwriting is clear and effortless like his work’.Footnote 82 The compelling nature of such observations attests less to the merits of graphology than to the latitude for interpretation in biographical data, handwritten marks and musical works alike – to the importance of correspondences between sources for winnowing down the possibilities, and to the process of selecting what resonates across media. Today, handwriting is rarely acknowledged as a source of information about the character of a composer or his music. But its centrality during the nineteenth century – its circulation in facsimile – meant that it shaped the perception of composers and their compositions, both for the general public and the emerging community of music historians.