Introduction: evaluation of research performance in law and law journals

The mass of scientific output is quickly growing,Footnote 1 which raises questions of its quality and societal impact. Although legal academia around the world produces thousands of law journals, law, as an academic discipline, lacks any commonly agreed quality indicators at an international level. Metrics, based on citation analysis, are rejected by the legal scholars’ community and various journal rankings are also controversial.Footnote 2 While legal scholars in many countries have so far succeeded in keeping their autonomy regarding where to publish their research, their colleagues in an increasingly high number of other countries are being evaluated based on metrics recorded in the Web of Science (hereinafter WoS), Scopus or in similar databases. Since these metrics affect their individual career paths as well as their universities’ research funding, they are compelled to adjust by publishing in journals that are listed in the databases their institutions expect and reward. This affects submissions to law journals and editorial boards are often compelled to adjust.

Research evaluation, including in the field of law, is increasingly important since the public demands to know whether research is paying off and government funding for academic research is becoming more dependent upon performance.Footnote 3 This requires some form of research performance evaluation.Footnote 4 As engaging experts to read and assess all books and papers is too costly and time-consuming when performing macro-level research evaluation,Footnote 5 university managers and research funders have resorted to proxies for determining the quality of research, such as indexation of journals based on citation-counting and reputation of publishing houses. These proxies are increasingly also used for research evaluation at a micro level.Footnote 6 However, while some claim that counting citations adds up to improved science,Footnote 7 others suggest that citation counting is killing academic dissent,Footnote 8 claiming that a bibliometrics-based approach restrains the freedom of researchers to decide what topics to focus on and where to publish their scholarly publications.Footnote 9 An increasing number of studies have revealed fundamental problems with peer review, and support the advocates of citation counting.Footnote 10

When it comes to metrics, law has much more in common with the humanities than with sciences.Footnote 11 Economics in particular is considerably different from law from the metric point of view.Footnote 12 However, even humanities have been compelled to make the quality of scholarly publications more transparent and internationally comparable and law is increasingly being pressured to do so as well.Footnote 13 As a positive consequence, an increasing number of publications deal with evaluating academic legal research, addressing the issues.Footnote 14

The starting point of this paper is that legal scholarship should not compare itself to other disciplines but should instead concentrate on research quality indicators best suited to it. When it comes to papers in law journals, it is imperative to establish criteria that would – within the myriad of law journals on the global market – distinguish those of higher or expected scholarly quality from those below this standard. Citation-based and peer review-based ranking of law journals are paralleled in the paper, using qualitative and quantitative analysis. The main research questions in this respect are:

to what extent does the journal impact factor, as defined by WoS, that is broadly accepted by other fields of research, conform to the specific nature of (European) legal scholarship? Is the journal impact factor completely at odds with legal scholarship or does it relatively appropriately rate law journals compared to a peer review-based ranking? What do editors of some of the internationally leading law journals that are not listed in the WoS think about applying to this ranking?

In this regard, the next section first looks at the position of law journals in the WoS, which is recognised across research disciplines and across the world as the most selective scholarly journal index, and is increasingly referred to by research funders. The paper then compares the WoS with the Finnish Publication Forum (JUFO), which is peer review-based, and provides some statistical analyses on correlations between the two, complemented by a study of the attitudes towards the WoS of over 40 editors of leading law journals.

1. Journal impact factor and legal scholarship

(a) A myriad of law journals

The law journals’ universe is very diverse and sizeable. Perez et al estimate that there are 1629 English language law journals in the world.Footnote 15 Authors of country reports in the book Evaluation of Academic Legal Research in Europe estimate that there are about 1300 German law journals that predominantly publish papers in German,Footnote 16 approximately 135 Austrian law journals, only seven of which partly or entirely publish papers in English,Footnote 17 over 100 Swiss law journals that publish German, French and Italian papers, but rarely English ones,Footnote 18 around 250 Italian law journals, predominantly published in Italian,Footnote 19 325 Spanish law journals that mostly publish papers in Spanish,Footnote 20 150 Dutch law journalsFootnote 21 etc. As it can be expected that other European countries, in particular larger ones such as France and Russia, as well as legal scholarship in Asia, Africa, Canada and Latin America, publish numerous law journals in languages other than English, one can conclude that there are an enormous number of law journals on the market. There is in fact no obstacle – beyond economic implications (which are increasingly irrelevant with the expansion of online publishing) – to prevent any law department or even an individual jurist, academic or professional from running his/her ‘own’ law journal. The increasing number of law journals, however, affects the quality of legal publications on account of acceptance rates being increased and it is illusory to claim that several thousands of law journals, mostly with equally attractive titles, are of comparable (high) quality.

(b) JIF – a controversial proxy for journal quality

To distinguish scholarly journals with higher recognition within respective disciplines from others, the concept of the journal impact factor (hereinafter JIF) was introduced by Eugene Garfield.Footnote 22 In the 1960s, Garfield launched the Science Citation Index (SCI), which in turn led to the multidisciplinary WoS platform.Footnote 23 WoS pursues the principle of selectivity, so that only journals that fulfil the stated criteria are included – most importantly that they can attract established scholars in the field of study (based on citation analysis).Footnote 24 This orientation derives from the so-called Bradford's Law of Dispersion, according to which a relatively small number of journals publish the majority of significant scholarly results.Footnote 25 Based on journal statistical data, Clarivate Analytics, current owner of the WoS platform, publish annual Journal Citation Reports (JCR), which assign citations to journals included in databases. The JCR is based on JIF that is defined as the average number of times papers from the underlying journal published in the past two years have been cited in other journals listed in WoS. Depending on their JIF, journals on the ranking are sometimes divided into quartiles (Q1 to Q4).

Illustration of the 2019 JIF calculation for Legal Studies:

$${\rm JIF\ } = {\rm Citations\ in\ }2019 \ {\rm to\ items\ published\ in\ }2017( {22} ) + 2018( {18} ) /{\rm Number\ of\ citable\ items\ in\ }2017 ( {33} ) + 2018 ( {34} ) = 40/67 = 0.597$$

$${\rm JIF\ } = {\rm Citations\ in\ }2019 \ {\rm to\ items\ published\ in\ }2017( {22} ) + 2018( {18} ) /{\rm Number\ of\ citable\ items\ in\ }2017 ( {33} ) + 2018 ( {34} ) = 40/67 = 0.597$$In natural sciences (and increasingly also in social sciences), JIF is used as a proxy for the relative importance of a journal within its field, with journals with higher JIFs deemed to be more prestigious than those with lower ones. Researchers are motivated to publish in prestigious journals and JIFs are frequently taken into account in academic promotions and pressuring researchers to target journals with a higher impact factor.Footnote 26 From an editorial perspective, more prestigious journals attract more papers and thus have the privilege of choosing the best ones for publication.

Citation analysis, however, turned out to be a true research policy minefield.Footnote 27 The opponents of metrics point out that authors cite for a variety of motives, some of which have little to do with research quality (negative citations; citations to show courtesy; self-citations used to promote oneself; citations to show command of literature in the field).Footnote 28 In contrast, proponents of the citation-based research evaluation argue that JIF is easy to understand, widely recognised, difficult to defraud, an objective indicator of influence, endorsed by funding agencies and scientists, independent and global. Garfield states that citations are the currency of science, with which scientists pay other scientists,Footnote 29 while Moosa maintains that ‘a fantastic paper that has not been cited at all is fantastic only because the author says so’, whereas a negative citation is, according to him, ‘better than no citation’.Footnote 30

To address the impact factor obsession and negative points about citation-based evaluation, important international initiatives, such as the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA)Footnote 31 and the Leiden Manifesto,Footnote 32 have been adopted in the last decade, warning against irresponsible use of metrics. Academic life without JIF, as contemplated by the Expert Group of the European Commission,Footnote 33 is, however, currently only a vision.

The Shanghai subject ranking for law, part of the notorious ARWU World University Rankings, is based to a large extent on citation data.Footnote 34 As universities strive to improve their position in this ranking, law departments are increasingly expected to contribute, with more papers published in the top quartiles of the WoS and more citations. When the general Australian Research Council (ARC) list was abandoned in 2011, all disciplines (with the exception of business) resorted to evaluation by the imperfect, but less subjective, impact factor.Footnote 35 When it comes to research evaluation at the macro level, most European countries have also chosen indicator-based models. According to Sivertsen, this is ‘not because they do not observe the scholarly standards and fundamental principles of research evaluation, but because they do not see direct institutional funding as the appropriate place for executing research evaluation’.Footnote 36 In Spain, it is reported that agencies which evaluate academic legal research give extraordinary weight to the publication of papers in indexed journals, especially in WoS. As a result, a researcher who has not published in journals listed in the indexed databases will have difficulty advancing his or her academic career.Footnote 37 This runs contrary to a 2018 decision of the Spanish Supreme Court ruling that research agencies may not rely solely on the impact factor but must also consider the quality of publications, regardless of the publication channel.Footnote 38 The Swedish Research Council also extracts data on the number of publications and citations from WoS. Although the research community in Sweden supported mixed quantitative-qualitative methods for quality evaluation, the government opted for a more mechanical, quantitative method of assessment (based on the number of publications and citations, as well as the amount of external research funding attracted by the respective higher education institution), mainly due to its simplicity and lower cost.Footnote 39 Being aware of metrics’ faults, the Swedish Research Council itself proposed to upgrade the current WoS-based bibliometric model, so that it would be used to complement a peer review system. However, the plan was rejected by the government due to its costliness and complexity.Footnote 40 Although the UK Research Excellence Framework (REF) has primarily relied on peer assessment in its evaluation of academic output, the Stern report of 2016 supported the use of metrics, stating that the committee supports ‘the appropriate use of bibliometric data in helping panels in their peer review assessment, and recommend all panels should be provided with the comparable data required to inform their judgements’.Footnote 41 In Slovenia, 25% of the governmental funding of universities providing higher education now depends on the number of scholarly papers cited in Scopus,Footnote 42 points for papers published in journals that are listed in WoS are multiplied in comparison to papers in non-listed journals, and researchers cannot apply for research projects and state-funded junior researcher positions unless they can demonstrate a certain number of citations in WoS and Scopus.Footnote 43

Legal scholarship has always been suspicious towards the concept of an impact factor. Jürgen Basedow explains that he has ‘serious doubts about the role and ascertainment of the “impact factor” in legal scholarship’.Footnote 44 According to him, scholarly publications in disciplines other than law are exclusively measured by their innovative content, so that the ascertainment of their impact makes sense, while most citations in legal publications simply serve to give some evidence of settled views, based on case law or legal literature. Basedow thus concludes that the idea behind most citations in legal publications is not to take account of novel ideas, which can therefore be ascribed a certain ‘impact factor’.Footnote 45

Since legal academics in an increasing number of countries cannot escape the use of metrics, the following subsections point out some of the characteristics of the law journal ranking based on JIF as calculated and reported by WoS. The second part of the paper then concentrates on peer review rankings of law journals, in particular the Finnish one, and analyses consistencies and discrepancies between the JIF-based and peer review-based rankings, in order to explore how the two systems conflict or complement each other.

(c) JIF-based ranking of law journals

There is a relatively slow-growing number of law journals indexed in WoS: from the 98 law journals that were listed in 1994, the number has risen to 150 in 2017 (53% increase).Footnote 46 The vast majority of journals in the WoS ‘law’ category are general law journals that usually attract more citation than specialised journals and are thus better positioned to be selected for listing. Contrary to some expectations, WoS does not exclude student-edited law reviews from the listing. As noted by Perez et al, student-edited law reviews ‘do not use peer review, and paradoxically, the academic community of legal scholars has almost no say in the selection process in these journals, whether as editors or reviewers. Despite these differences, the two categories are lumped together in all the major academic rankings, including WoS and Scopus’.Footnote 47 It is also evident that WoS is inclined towards interdisciplinary fields covering ‘law &’ subjects, most notably criminology, medicine and law and psychology and law. Moreover, the number of articles published within the law journals listed in WoS is low in comparison to other fields. Consequently, in 2017, there were 4,164 articles published in all the 150 listed law journals together, whereas physical chemistry and applied physics – which have a similar number of listed journals to law in their respective categories – each published over 68,000 articles a year.Footnote 48 While 51% of the listed law journals are quarterlies, in many other disciplines, such as chemistry, oncology and physics, the majority of journals are published monthly.Footnote 49 This affects the publication and citation dynamics, in particular the ‘h-index’ that presupposes a high number of publications.Footnote 50

JIFs for law journals are also relatively low in comparison to certain other disciplines, with the highest JIF in 2017 held by Yale Law Review at 5.2.Footnote 51 Moreover, the average JIF for law journals has for decades been around 1.0, with its peak value in 2000 (1.436) and the lowest value in 2013 (0.868). In other fields the average JIF has grown significantly in the last 20 years.Footnote 52 This means that articles in the law journals listed in the WoS are on average cited less often in the first two years after publication compared to articles in selected other fields, and that the average number of citations is not increasing as it is in selected other fields. This is hardly surprising, considering the mostly single authorships that lead to slower dynamics of publications in law in comparison with fields where several authors – or even whole consortiumsFootnote 53 – work on a paper, as well as that articles in law are on average considerably longer than articles in natural sciences and engineering,Footnote 54 leading to longer review procedures and consequently slower publishing dynamics. Moreover, law journals focus on ‘qualitative’ rather than ‘quantitative’ methods and, as Swygart-Hobaugh found, scholars applying quantitative methodologies tend to be more frequently cited than their qualitatively-oriented colleagues.Footnote 55 In this respect, all law journals listed in WoS received 5282 citations in WoS in 2017, which is, for example, less than a single journal or even a single highly-cited paper in medicine or natural sciences.Footnote 56

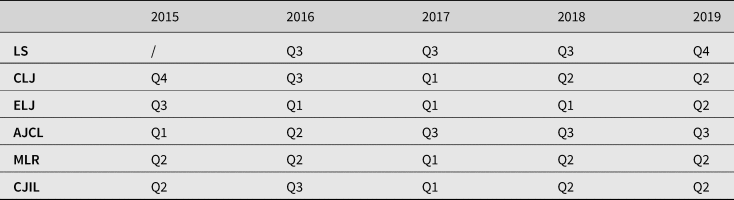

A consequence of this low average JIF in law is that the majority of the listed law journals have very similar JIFs.Footnote 57 Consequently, law journals easily leap from one quartile of the ranking to another on a yearly basis. Table 1 shows the inconsistency in rankings on the WoS list with respect to Legal Studies (LS), Cambridge Law Journal (CLJ), European Law Journal (ELJ), American Journal of Comparative Law (AJCL), Modern Law Review (MLR) and Chinese Journal of International Law (CJIL).

Table 1. Ranking of selected law journals listed in WoS quartiles from 2013–2019

Source: Data retrieved from Journal Citation Reports, Clarivate Analytics

It may be concluded that law journals in WoS are in certain aspects not comparable to journals in categories such as economics, medicine or natural sciences. Yet, this does not necessarily mean that the WoS ranking is irrelevant for law, but rather that law journals in WoS should only be compared to other law journals.

(d) Relevance of books for citation-based ranking of law journals

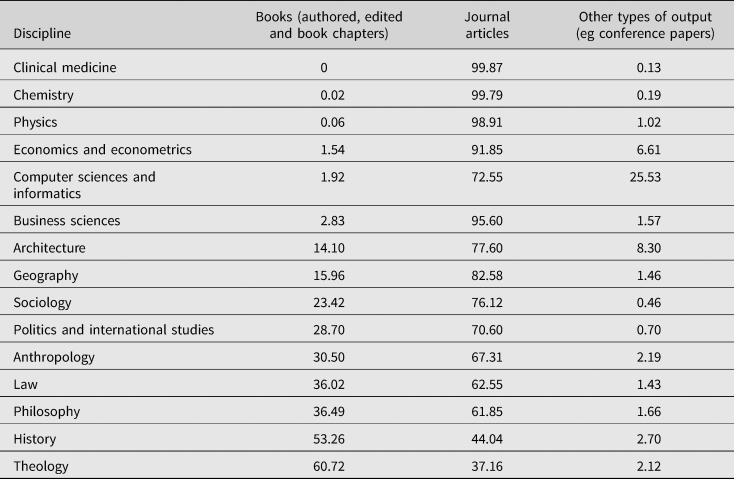

When evaluating law journals based on citations, it is important to note that the 150 law journals on the WoS list are by no means the only (scientifically relevant!) output of legal scholars. If books, working papers and a significant number of leading law journals are not covered by the journal ranking based on citation analysis, the results of the research performance analysis are considerably frustrated.Footnote 58 Research output data show that books are just as significant in law as in humanities (called ‘book-oriented fields’ by the Metric Tide Report).Footnote 59 On the basis of data on research output type collected under the UK REF (2014), I have calculated relative shares of books, journal articles and other types of output that have been submitted for evaluation in the selected research discipline.Footnote 60 Table 2 shows the varied relevance of books in these disciplines.

Table 2. Share of books and journals in total research output submitted to the UK REF (in %)

Source: Author's calculations based on data in Table 4, Wilsdon, above n 45, p 154.

The above figures show that assessing publishing on the basis of JIF is entirely different in natural sciences and economics in comparison with law and humanities. This large share of books is even more meaningful considering authoring a book requires significantly more effort than a journal article, which means that absolute data on the number of published books and journal articles needs to be weighted to reflect this.

The above is accepted by the scientometric theory, which distinguishes between disciplines with excellent, good and moderate WoS coverage. In most disciplines the WoS coverage is excellent or good, providing a firm justification for the bibliometric use of WoS indexes in research evaluation in these disciplines. However, in certain parts of social sciences and in the humanities, including law, the WoS coverage is moderate. In these disciplines, scientometrics experts note that one should be cautious when using WoS indexes in the assessment of research performance.Footnote 61 This fact was also acknowledged by WoS, but only for arts and humanities. The latter have a special ‘Arts & Humanities Citation Index’ where no JIFs are calculated.Footnote 62 As is pointed out by the authors of The Leiden Manifesto for Research Metrics in principle No 6, ‘Historians and social scientists require books and national-language literature to be included in their publication counts’.Footnote 63 Books may thus by no means be disregarded when analysing the impact of law journals, nor when evaluating research performance in legal scholarship altogether. When it comes to bibliometric evaluation of research performance, the legal research community should strive to be assessed by humanities’ standards so that JIF does not serve as representative information on law journals’ full impact, in particular until such time as book citations are captured by JIFs’ calculations.

(e) Internationalisation v local commitment of legal scholarship

One of the main criteria for selecting a journal to the WoS list is that the journal has adequate international impact. It is generally believed that only research that leads to results, the relevance and implications of which reach beyond a purely national interest or viewpoint, may be considered as genuine.Footnote 64 In contrast to natural sciences, law (similar to other disciplines of social sciences and humanities) has an intrinsic connection with the national environment, parliaments, courts and administrative bodies that create national law and practice in national languages. It is arguable, therefore, whether scholarly research that is primarily related to national aspects is of interest and should be communicated to scholars in other countries. While the US Justice Antonin Scalia claimed that comparative law does not have any normative meaning for answering legal questions that arise in the US system,Footnote 65 it has been shown that law journals by US law schools have a very strong national orientation, yet they are considered international by WoS.Footnote 66

When assessing JIFs in law, it is important to note that a considerable majority of law journals indexed in WoS are US-based. In 1994, 20 years after the SSCI index had been launched, there were only 10 non-US law journals on the list, where the Common Market Law Review, ranking 42nd, was the highest ranked among them at the time. Out of 150 law journals that were indexed in this database in 2017, 88 (ie 58%) were US-based; a further 37 were based in England (25% of all listed law journals), 12 law journals were based in the Netherlands and only 13 of them in other countries across the globe.Footnote 67

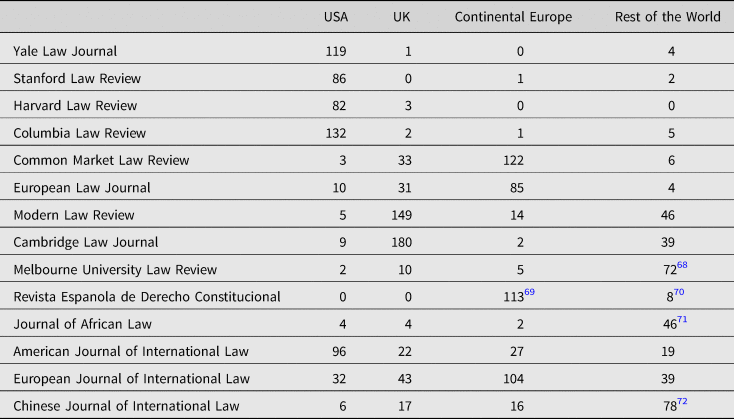

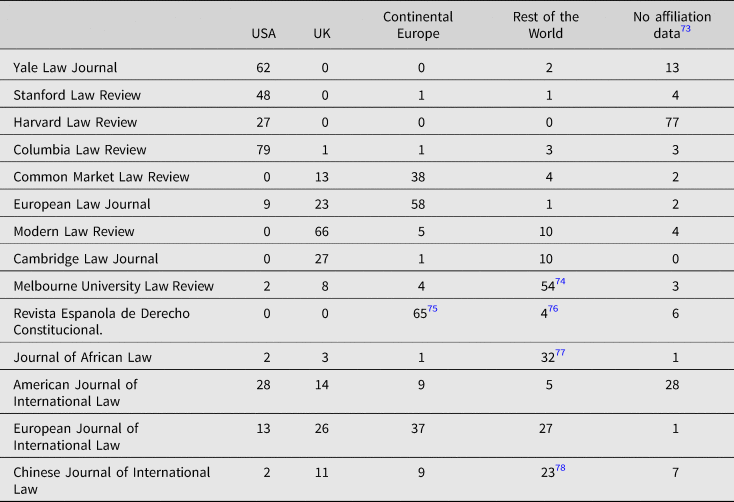

Further, as Tables 3 and 4 show, considerable regionalism in publication of legal scholarship still exists, so that US law journals mostly publish papers from US-based authors and are at the same time mostly cited by US-based authors. The same also stands for European law journals and law journals from other continents across the globe. This national or regional orientation of legal scholarship is to a lesser degree noticeable in respect of international law journals, but still present, which means that there is no single global legal scholarship, but rather several regional ones.

Table 3. Paper contributions by countries/regions, 2015–2017

Source: Calculations based on data in Incites Journal Citation Reports, Clarivate Analytics

Table 4. Citation contributions by countries/regions, 2015–2016

Source: Calculations based on data in Incites Journal Citation Reports, Clarivate Analytics

A consequence of the US-dominated ranking of law journals and regional citation patterns is that the US has a very high percentage of country self-citations. Data from Scimago that are based on ScopusFootnote 79 show that the US share of country self-citations in law journals is 58%, which is much higher than in some other countries – eg Austria only has a 9% rate of country self-citations.

Table 5. Share of self-citations by selected countries in law journals (1996–2017)

Source: Scimago Journal & Country Rang, Social Sciences, Law, All regions, 1996–2017

The high share of self-citations by US researchers does not mean that Austrian legal scholars do not cite Austrian colleagues as often as American legal scholars cite fellow Americans, but that in comparison with the latter the former have significantly fewer publications in the journals listed in Scopus and WoS and the data on the self-citation rate based on the listed journals consequently do not reflect the full country self-citation rate. For the same reason US law journals have relatively higher JIFs than law journals from other countries. Considering there is only one journal dealing with African law in WoS, it is hardly surprising that it has the lowest JIF among all the law journals on the list.Footnote 80

This means that JIF functions on the basis of the snowball effect: the more journals from a particular jurisdiction are included in the database, the more citations they collect and the higher the impact factor they have. Although Tables 3 and 4 show that US law journals do not have greater cross-border impact than non-US law journals, the former grasp of 60% of titles in the law category of WoS makes it easier to show adequate citation impact than the latter. To improve the presence of European law journals in WoS, the snowball needs to be pushed downhill, with more titles applying for selection in WoS. With few European law journals on the list, however, these and the ones yet to apply have difficulty showing their (international) impact.

Moreover, for the majority of researchers the citation-based analysis of law journals is hampered due to national and linguistic barriers.Footnote 81 International focus is one of the key criteria in the selection of a journal for WoS, which focuses on journals that publish full text in English. Hence, it is considered that the journals most important to the international research community are published in English.Footnote 82 While WoS admits that the English rule has notable exceptions in humanities and social sciences, there are only three law journals listed in WoS in 2019 that are not fully published in English.Footnote 83 Specific importance of the local language for legal scholarship is thus hardly reflected in the selection of law journals for the WoS list.Footnote 84 The prevalent position of English when selecting journals for WoS means that younger legal scholars in particular lack the motivation to publish in other languages, in particular less spoken ones, thereby steering the selection of their research topics towards those that are more suitable for English language law journals, leaving aside national and local issues.Footnote 85 With national legislation, judicial and administrative practice being published in national languages, researchers from other jurisdictions are restricted to addressing legal issues from these jurisdictions. Although it would be crucial to improve the rule of law in their domestic jurisdictions, especially when it comes to developing countries, researchers can either focus on topics that should be attractive for US law journals or find shortcuts by publishing their papers in journals from non-law categories of WoS that accept introductory legal topics for a non-legal audience. As accessibility of the former (as shown by data in Table 3) is very limited for non-US scholars, the latter path will often be chosen by the researchers.

2. Peer review rankings of law journals

(a) Peer review-based rankings controversy

Until the criteria for selection of journals to WoS are more attuned to European legal scholarship, as advocated by the Leiden Manifesto principles,Footnote 86 peer review-based rankings (and preferably a single European one with limited national variations), based on quality reputation of journals,Footnote 87 can perhaps make up for many of the shortcomings of the JIF-based ranking of law journals. It needs to be admitted, however, that the peer review-based journal rankings are as controversial as the WoS-based ranking.

Moosa is particularly critical about peer-review systems, claiming that this approach leads to academics lobbying for the upgrading of journals that they edited, or in which they published. He stated that if ranking is determined by the personal preferences of committee members, then rankings could change ‘by the stroke of a pen’ as a result of the principle that ‘this is a great journal because I have published there’.Footnote 88 In respect of Sweden, Bakardjieva Engelbrekt explains that Sweden is the only Nordic country refusing peer review-based ranking of journals, opting for a WoS-based bibliometric system instead, due to the concerns about the integrity and objectivity of the procedure for ranking journals, which is strongly influenced by the views of the representatives in the panels. Journal rankings are also seen as a less robust indicator of quality than the actual number of citations.Footnote 89 By contrast, a UK report published in relation to the 2008 Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) noted that ‘(b)ibliometrics are not sufficiently robust (…) to replace expert review’.Footnote 90

It thus seems that peer review-based journal rankings have been accepted not because they are so terrific, but because certain scholarly communities consider they are better than citation-based ranking. As noted by Letto-Vanamo in respect of the Finnish peer review ranking, ‘(a)lthough the rankings are criticized (…) the application of bibliometric analysis or citation indexes would hardly be accepted among Finnish legal scholars’.Footnote 91 It is essential, however, that peer review-based rankings are conducted by legal scholars experienced with scholarly publishing, that the process is transparent, with members of the panel and criteria for ranking publicly announced. The participation of the research community in the process is also very important for increasing the objectivity and legitimacy of the ranking, as well as periodical review for keeping the ranking up to date.

Due to the shortcomings of the JIF-based ranking of law journals, there have been numerous attempts to establish a substitute ranking to WoS.Footnote 92 Since 2015 Denmark, Finland and Norway have been joining their national lists of authorised research publication channels used as indicators in the national performance-based research funding systems.Footnote 93 Due to its user friendliness, transparency and explicit evaluation criteria, the law journal ranking by the Finnish Forum was applied for the purposes of this paper, with some analysis also covering the other two Nordic rankings of law journals. Although the Finnish Publication Forum (in Finnish Julkaisufoorumi, JUFO)Footnote 94 has been developed for Finnish academic funding purposes and is not readily suitable for broader European use, the Finnish system could serve as a role model to develop a European peer review ranking of law journals.

(b) Finnish ranking of law journals

JUFO is a project set up by the Federation of Finnish Learned Societies, after universities adopted result-oriented management models and following the decision of the Ministry for Education that scholarly publications be introduced to the university funding model.Footnote 95 The evaluation is performed by 23 discipline-specific expert panels, composed of some 250 distinguished Finnish or Finland-based scholars. The panellists are chosen from among academics with experience in research work, scholarly publishing and research evaluation.

Evaluation and ranking of law journals is under the jurisdiction of Panel 19, which covers political science, public administration and law (including criminology). It is composed of ten Finnish professors affiliated with different Finnish universities, chaired by Jukka Snell from the University of Turku, co-editor of the European Law Review. The panels are expected to consult their background communities. This means that the scientific community can contribute to and influence the future development of the classification. In order to keep the classification reliable and updated, the review of ratings is performed at four-year intervals, meaning that fluctuation of rankings is not as rapid as the fluctuation of rankings based on JIFs.

In order to meet the scientific criterion, a peer reviewed publication must contain new research results in a form that is publicly available, reproducible and utilisable. A publication must have an external publisher; author's editions are not considered as publications. To support their work, the panellists can utilise a number of different impact indicators and indexing data, as well as data on the levels awarded in the corresponding Norwegian and Danish systems. Depending on the particular publication practices in various disciplines, certain panels give more weight to JIFs than others. Citation analyses and indicators are widely used in the fields of natural sciences and medicine to assess the value of research, but less so in social sciences and humanities. As a consequence, a Level 1 law journal may have a higher JIF than certain Level 2 law journals. Consequently, JUFO is more adjusted to the Leiden Manifesto than WoS.

989 journals have been evaluated and classified under the category ‘social sciences – law’. The journals are ranked in accordance with a quota system with a pyramid structure so that there are 22 law journals in the highest rank (rank 3), 119 journals in the middle rank (rank 2) and 736 journals in the standard rank (rank 1). Moreover, there are 102 law journals on the list that have been given a ‘non-ranked’ status (or rank 0).

First, 22 journals in the world top level (rank 3) inter alia include American Journal of Comparative Law, Common Market Law Review, European Journal of International Law, European Law Journal, European Law Review, Harvard Law Review, Oxford Journal of Legal Studies and The Modern Law Review. Due to the quotas, Level 3 can contain fewer than 5% of all publication series and it is therefore impossible to meet the objective of having at least one journal per each speciality in the highest level. Level 3 journals include the supreme-level journals that cover the discipline comprehensively, have extremely consistent impact, international authors and readers and editorial boards that are formed of the leading researchers in the field, so that publishing in these journals is highly appreciated among the international research community of the field.Footnote 96 All level 3 law journals are published in English, as it is believed that in such journals competition between authors is more intense and peer review procedures are usually more demanding than in non-English law journals.Footnote 97

Secondly, according to the criteria, Level 2 (internationally leading law journals) can be awarded to leading academic journals where researchers from various countries publish their best research findings. These are mainly international journals, with editors, authors and readers representing various nationalities. The panels must choose within the framework of their Level 2 quota (maximum 20% of the aggregate publication volume (Levels 1–3)) those journals where the highest-level publications are directed as a result of extensive competition and demanding peer reviewing. The Level 2 list includes the following law journals, for example: American Business Law Journal, European Constitutional Law Review, Columbia Law Review, Stanford Law Review etc.Footnote 98 While all journals at Level 3 publish English papers, Level 2 journals include notable non-English law journals,Footnote 99 as well as leading Finnish or Swedish-language publication channels that are seen to be as important a merit as publishing in an international Level 2 channel.

The largest category of law journals on the list that is not quota restricted includes 736 journals at Level 1 (standard academic research). According to the JUFO criteria, Level 1 can be awarded to domestic and foreign journals that meet the criteria of an academic publication channel, ie that publish scholarly research outcomes, editorial boards are constituted by experts and peer reviewed. This category of journals includes a long list of international, European, Asian, African, as well as various regional law journals, including Nordic, Baltic, Australian, Russian, American, German, French, Italian, Croatian, Slovenian and other journals. While the large majority are published in English, journals published in various other languages are also found on the list.Footnote 100 Journals publishing in languages not spoken by the panel members are a challenge, as the panel is restricted to deciding between rank 0 and 1, based on the information provided on the journal's website that details formalistic criteria about peer review, editorial board etc.Footnote 101

Finally, 102 of the evaluated journals in the category ‘law’ do not have a ranking. This means that the journal in question does not, according to the evaluation panel, meet some of the Level 1 criteria, eg that over half of the referees and authors represent a single research organisation and the relevance or quality of research raises questions.

Peer review-based ranking is therefore able to neutralise certain biases of WoS, discussed in the previous section of this paper, especially in respect of law journals that for some reason cannot enter into WoS (law journals that do not publish English papers and specialist law journals that have difficulty attracting enough citations to show a sufficiently significant impact on the scholarly community to be selected for inclusion in WoS) or where JIF does not fairly reflect the reputation of a law journal within the academic community, while at the same time preserving the national commitment of legal academia. The main objective of this paper was to establish to what extent rankings based on JIF and peer review overlap, and – based on this – conclude on the relevance of JIF in the field of legal scholarship.

(c) Comparison between WoS and Nordic peer review ranking of law journals

(i) Methodological clarification

To ascertain to what extent rankings based on JIF and peer review overlap, JIFs – as published by the Clarivate Analytics for 2017 – were attributed to the journals that are listed in the ‘law’ category of the Finnish ranking of journals.Footnote 102 It must be emphasised that the law category of journals in WoS (150 journals) differs from the law category in JUFO (989 journals), as the latter includes not only journals in the former category, but also journals that belong to other categories in WoS (eg criminology, women's studies, international relations etc) as well as a large number of journals that are not listed in WoS. It was thus established that 257 journals from the JUFO ‘law’ ranking are listed in different categories of WoS.

Based on the above, various correlations between the two rankings were statistically examined in terms of their overlapping and gaps. This, inter alia, led to a list of law journals that are considered to be internationally leading by the Finnish peer reviewers, yet they are not listed in WoS. The same was also done in respect of Norwegian and Danish law journals’ rankings. I then contacted all the editors of this group of law journals with publicly available e-mail addresses, asking them to comment on their attitude towards WoS. A remarkably large share of editors replied to my inquiry, suggesting that the issue of journal rankings is an important one and that an international debate on this topic is needed. The editors’ responses are discussed after the analysis of the correlations between the JIF- and peer review-based rankings of law journals.

(ii) Statistical analysis of parallels between JIF and peer review-based rankings of law journals

First, law journals that are highly ranked by peer reviewers, despite having no or low JIF, were looked at. It was established that there are no law journals among the world's top law journals on the Finnish ranking that are not also included in WoS. Moreover, all of the world's top law journals are ranked in the first quartile (Q1) of WoS. It may thus be concluded that all law journals that are considered as journals of the highest quality by legal experts are also ranked highly in WoS and that JIF, in certain respects, mirrors the quality reputation among Finnish peers, in the field of law.Footnote 103 While it is true that some law journals in this group have not always been in the Q1 of WoS, the majority of them hold a stable JIF in Q1. This considerably strong overlapping between the JIF-based and peer review-based ranking of law journals in the most prestigious category is interesting, considering that the country citation coverage does not indicate that Finnish legal scholars highly cite all of the journals in the group, in particular not the US university law journals (see Table 4 above).

Additionally, there are only a handful of law journals listed in WoS that are highly regarded by Finnish legal experts but do not rank highly in WoS.Footnote 104 Moreover, only three law journals of the highest rank awarded by the legal experts were in Q3 of WoS in 2017, yet all three of them had had higher JIFs in the past.Footnote 105 A similar conclusion about the overlap of the JIF-based and peer review-based ranking may also be made at the lower end of the Finnish ranking, as there is only one law journal in the category ‘non-ranked’ (or rank 0) on the JUFO list, that is listed in WoS.

Significant disparity between the citation and expert based ranking of law journals, however, subsists in the category of internationally leading law journals (rank 2 of the JUFO ranking). First, there is a group of 27 American university law reviews that are in Q1 of WoS but which are not included in the quota of the world's top journals on the JUFO list (rank 3).Footnote 106 This group of law journals has very mixed rankings on the other two Nordic listings, with the lower rank (1) prevailing. Furthermore, there are six law journals that have been ranked as internationally leading by the Finnish legal experts, yet they are only in Q4 of WoS.Footnote 107 While this would be considered as a sign of less renowned journals in some other disciplines, this is evidently not so in legal scholarship.

More importantly, however, 56 law journals out of 121 journals that are considered as internationally leading by the Finnish experts are not included in WoS at all (ie 46%). A significant share of internationally leading journals on the Danish and Norwegian expert based ranking of law journals are also not listed in WoS. The Danish ranking of law journals, which only distinguishes between rank 1 (basic) and rank 2 (leading) law journals, classifies 57 out of 87 journals in the leading category that are not listed in WoS (ie 65%). In respect of the Norwegian list, 26 law journals out of 66 in the leading rank are not listed in WoS (ie 39%).

Within this group of journals, three categories of journals may be established:

(i) generalist law journals in English and in other widely spoken languages: eg Cahiers De Droit Européen, Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies, German Law Journal, Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, The Columbia Journal of European Law etc;

(ii) renowned specialist law journals: eg European Business Law Review, European Company and Financial Law Review, European Journal of Health Law, European Review of Private Law, Human Rights Law Review, Public Procurement Law Review, Ratio Juris, Zeitschrift für Europäisches Privatrecht, Tijdschrift voor Rechtsgeschiedenis; and

(iii) regional or national law journals: eg Lakimies, Nir: Nordiskt Immateriellt Rättsskydd, and Tidsskrift for Rettsvitenskap.

There is, therefore, a large share of journals in the field of law with a strong international reputation that are not (yet) listed in WoS and do not have JIFs recorded, nor do citations in these journals contribute to JIFs of law journals listed in WoS. A large number of internationally reputable law journals not indexed in WoS does, however, not mean that legal scholarship is insusceptible to the WoS and JIF phenomenon, since many law journals from this group are listed in the Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI).Footnote 108 ESCI serves as a waiting room for the core WoS indexes, with less stringent acceptance criteria but without attributing an impact factor to a journal.

It is further relevant that although the three Nordic ranking systems function in a coordinated way, there are manifest differences between them.Footnote 109 Two groups of journals stand out in this respect: certain national law journalsFootnote 110 and numerous specialist law journalsFootnote 111 and multidisciplinary onesFootnote 112 that are difficult to rank when there is no metric indicator behind the comparison. It is also notable that it is more likely that the differences in ratings subsist in respect of journals not indexed in WoS than in respect of journals that are listed in WoS: eg out of 34 law journals on the Danish leading list that are not also ranked high on the Finnish list, 28 law journals are not indexed in WoS, while only 6 are. It will thus be interesting to follow whether/how these rankings will adjust once these journals are indexed in WoS, and speaks in favour of a more harmonised European peer review-based ranking of law journals with a uniform core of law journals and national specific sections.

In respect of the 743 journals ranked as basic (rank 1) on the JUFO list in the category ‘law’, their ranking in WoS is also very diverse: 16 journals are in Q1; 43 in Q2; 46 in Q3; and 67 in Q4 of WoS, while the rest are not listed in WoS. The discrepancy in rank 1 is obvious due to the high selectivity of WoS.

Since the competitive citation-based index of journals – Scopus (operated by Elsevier) – has broader coverage of law journals than WoS,Footnote 113 I have checked the extent to which JUFO and Scopus overlap. Table 6 shows data in respect of the coverage of law journals, ranked by JUFO, in Scopus, where there are 512 law journals in the ‘law’ category, with additional journals publishing legal topics in other related categories. While Scopus is less strict when selecting journals for the index, eg accepting yearbooks, still nearly 30% of the internationally leading law journals from the JUFO list are not listed in Scopus. Importantly, this shows reluctance by editors of law journals to listing their respective journals in citation databases.

Table 6. Coverage of law journals listed on the JUFO ranking in WoS and Scopus (in %)

Source: author's calculations

Comparing the Finnish ranking with the UK ranking of law journals that was established by Campbell et alFootnote 114 based on the most important submissions by UK researchers to the first UK Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) in 2001, which displayed 33 law journals with the highest volume of submissions, it was found that – despite the fact that the UK ranking was based on data from 2001–30 of these 33 UK journals are also listed on the JUFO list (ie more than 90%),Footnote 115 with 21 of these journals (63%) ranking as world top (rank 3) or international leading (rank 2) on the Finnish ranking. The remaining third of UK law journals that do not rank as high in the Finnish ranking are mostly law journals of more local UK relevance (ie Judicial Review, Scottish Law and Practice Quarterly, Edinburgh Law Review), none of which are indexed in WoS.

After examining law journals on the JUFO ranking from the perspective of their JIF, journals that are listed in WoS were observed from the perspective of their position in the JUFO ranking.

It was first established that there is only one journal in WoS that has been ranked below basic (rank 0) by the Finnish legal experts, even though it is in Q1 in WoS.Footnote 116 This discrepancy most likely results from a computer mistake, rather than from a lack of standards for this journal, considering that it is a multidisciplinary journal that was probably left out by all competent panels. There are thus no relevant discrepancies between the two rankings in this respect. As noted before, there is a considerable group of mostly US universities’ law reviews with high JIFs that classify them in Q1 of WoS, yet they are not considered as world top journals by Finnish peer reviewers (rank 3). Still, many of them are considered as internationally leading (rank 2).

There are 16 law journals that are in Q1 of WoS, but have only been awarded with rank 1 by Finnish experts.Footnote 117 Some of these journals are not categorised under law in WoS,Footnote 118 some US universities’ law journals are not as highly reputed by Nordic peer reviewers as their JIF would suggest,Footnote 119 while some have only recently achieved a high JIF.Footnote 120 This group of law journals is also generally ranked in the lower rank of the Danish and Norwegian rankings.Footnote 121

Table 7. Rankings of law journals listed in WoS on the Finnish peer review ranking

Source: Author's own calculations based on data in JUFO and WoS.

It may thus be established that a high JIF, which places a law journal in Q1 of the WoS ranking or even in a top-ranked position based on citation counts, does not automatically classify a law journal as ‘world leading’ by expert judgment, which may partly be attributed to the quota system of the JUFO ranking and partly to the regional perception of law journals’ influence.Footnote 122

***

Two main conclusions can be deduced from the above analysis. First, despite the criticism of the legal community towards JIFs, the latter is not completely at odds in the field of law. The most reputable law journals on the Finnish peer review ranking are all listed in WoS and have high JIFs. On the other hand, there is only one law journal listed in WoS that is classified in the non-ranked (0) category of JUFO. Criteria for evaluation of journal quality applied by WoS reviewers and Finnish peer reviewers, eg scientific nature and international impact, are therefore similar to a considerable extent. Law journals indexed in WoS more consistently rank high on the peer review rankings than those that are not in WoS. It is moreover noticeable that upon the publication of JIFs by the Clarivate Analytics for the previous year, editors of law journals that rank high proudly announce this fact on social media, while some law journals also publish their JIF and quartile in WoS – a practice known in most STEM disciplines.Footnote 123 JIF is thus afforded higher relevance than the legal scholarship is perhaps willing to admit.

On the other hand, however, WoS is certainly not the only criteria for assessing the reputation of law journals. Other than by using citation based analysis, it is clearly very difficult to rank academic journals. Based on regionally determined citation spread of law journals that are listed in WoS, one can judge the regionally determined perception of reputation of a law journal by peer reviewers. Americans will hardly consider European journals as leading, while WoS data show that European authors do not cite US law journals listed in WoS to a great extent. Since there are considerable differences between Nordic peer review rankings, especially in respect of those law journals that are not listed in WoS, one can assume that disparities would grow proportionally with the growth of the applicable geographical scope of the ranking. Despite these concerns, however, the Norwegian ranking of publication channels is used to accredit research publications in South Africa.Footnote 124 Moreover, about two thirds of law journals, especially general law journals, rank highly in all rankings. Specialist law journals are in a more difficult position and vary more noticeably when different rankings are compared (eg environmental law journals, company law journals, nationally relevant journals).

To conclude, JIF-based and peer review-based rankings are complementary: while WoS has a global reputation and attracts authors who want or need internationally certificated publications, a comparison with the peer review ranking shows that WoS has adequate standards in terms of scholarly publishing when selecting journals for the list. In contrast, peer review ranking can complement the list of journals in WoS by remedying some of the latter's shortcomings (eg bias towards US, English-language, generalist law journals), though it also has some shortcomings (eg possible subjective judgment by peers compiling the ranking).

(iii) Editors’ response to the survey

Since statistical data have shown that a large share of law journals are not listed in WoS, despite peer review rankings classifying them as being internationally leading journals, I wondered whether, considering their reputation among peers, these law journals have applied or plan to apply for inclusion in WoS, or whether they had some reservations about making such an application, and if so, what those were. Due to some missing editors’ names or difficulty finding their e-mail addresses, I contacted 50 out of the 56 editors of law journals that are considered as ‘internationally leading’ by the Finnish experts, but which are not included in WoS. I asked what their position was on WoS. It was a single question, without a questionnaire, as the survey was qualitative rather than quantitative. I contacted the editors only once, without reminding them about not replying. 45 editors responded to my inquiry; such a high response rate strongly suggests that discussions on the evaluation of law journals are pressing. This subsection briefly summarises the editors’ responses and conducts a brief analysis in this respect.

Table 8. Positions on WoS by editors of internationally leading law journals (according to JUFO) that are not included in WoS

Source: Author's survey among editors of law journals based on e-mail communication in summer 2019.

First, there are some editors that have limited knowledge about JIFs and WoS. They responded, for example, that they have ‘absolutely no idea’ or that they are ‘not familiar with the “Web of Science” factory’ or that they are not aware of indexing issues with respect to their journal, as these decisions are made by their publishers. Two editors emphasised they are not eligible to apply for WoS indexing, as they do not publish sufficient citable content each year to qualify (ie twenty papers). This is a particular problem not only for yearbooks but also for certain specialist law journals that publish a small number of articles per year, to make a strong selection. One of these two editors has reported that they plan to increase the number of papers published, in order to be able to apply for WoS.

A third of the responding editors have reported that they have not applied to WoS, nor are they planning on doing so for a variety of reasons, such as because they are simply not interested in WoS as they have a more practice-focused audience, or because it is sufficient that their journal is indexed on Westlaw. Frank Hendrickx, president of the International Association of Labour Law Journals (IALLJ), which groups about 30 leading labour law journals around the world, noted that IALLJ did not follow an active strategy of being recognised with various lists, as the ranking issue for law journals is not yet fully mature.Footnote 125 One editor noted that their journal is cited by the Court of Justice of the EU and not being indexed in WoS has consequently not discouraged several hundred libraries from purchasing their journal. Certain editors strongly oppose JIFs and WoS and for this reason alone have not submitted their journal to WoS, and while some editors do not strongly oppose WoS, they nevertheless do not see ‘what the added value would be for a law journal to be accepted’, noting that ‘content and quality of content are our prime concern’. Finally, some have not applied for WoS due to their lack of support staff, and the time-consuming process to adhere to WoS standards.

Almost half of the responding editors had already applied or were planning to apply to WoS at some point in the future, in order to attract contributions of a higher quality. One editor responded, for example, that although journal rankings are not used in the UK REF, they are aware that rankings are important in other jurisdictions and since they want to attract authors from these jurisdictions too, they plan to apply for inclusion in WoS. Another editor stated that their publisher had started the application process to WoS and although he was not involved in the process as he focuses on peer review and academic standards, he ‘totally support[s] the process, because we'd like to draw the best authors, and some of them might be interested in these rankings (because their institutions do)’. Another editor explained in this respect that ‘it has become more difficult to compete with ranked journals, which, eg for funding reasons, have grown more attractive even for ‘accomplished authors’. An editor of a journal that was rejected by WoS twice noted that even though they were puzzled after the second rejection, they decided to adjust the publication policy (increasing the number of articles published per year), ‘since the non-indexation prevent us from receiving interesting articles from colleagues operating from countries where it is useless to publish in non-indexed journals’. A few editors stated they have recently changed a smaller publisher for a bigger one and are foreseeing that this change will make it easier for them to apply for inclusion in WoS. It was also noticeable that although some editors were not strong supporters of WoS, their publishing houses convinced them to apply to WoS, since ‘being included in the Web of Science (WoS) does make the journal more discoverable, because researchers use the journal listing and journal citation ranking “JCR” to identify journals to submit to and to read. Being included (…) increases the journal and articles findability’.Footnote 126 Furthermore, some editors have noted that their journals have been submitted for inclusion in WoS and that after two years of evaluation, the journals have been accepted for inclusion in the ESCI; they are thus hoping to be accepted in the core collection in the next few years. It has also been noted that WoS is ‘a tough environment for “regional” journals’, yet they pushed to get more citation potential by being included in ESCI.

Three of the responding editors’ journals had already applied to WoS, yet have been declined due to low citations, quality of peer review or low volume, while one journal had at the time of application been considered too young to show a track record of excellence.

Despite the controversy of JIF and WoS among legal scholars, the majority of the responding editors had no strongly held views in this respect, with the prevailing number of law journals already included in ESCI or planning to apply for inclusion therein in the future. With respect to several journals, the editors noted there has been a shift in editorial policy towards WoS in the past few years. This shift was observed in two directions. While some editors have noted that their predecessors had felt that in the field of legal publications ‘there would be no benefit from an inclusion in such doubtful ranking mechanisms’, the present editors feel that ‘it has become more difficult to compete with ranked journals’ and they will thus check how they can ‘adequately reflect and stir the aspired importance of our journal’ through the ranking mechanisms in the future. Even several practice oriented law journals noted that their authorship has shifted over the years (towards a more academic one) and in this respect the editors are now reviewing their current submission and indexing policy. In contrast, some editors noted that ten or more years ago they planned to submit the journal to WoS in order to achieve international qualification, however, with the change of generations in the editorial boards, the journals are now more practice-oriented, leaving aside the plans to be included in WoS.

In searching for journal editors and their contacts it was also evident that a number of law journals have a very weak website presence, with the most recent content dating back to 2016, no online publication of current issues’ contents etc, which lowers their visibility and impact. In comparison, in natural sciences that traditionally display high JIFs and have a high number of journals indexed in WoS, publishers actively distribute information about the most recent articles and also encourage authors to disseminate their papers as broadly as possible (through relevant academic associations, LinkedIn, Research Gate etc). Science journals even practise monthly citation updates for authors via Mendeley. While one can have an unfavourable view of the dissemination of research publications solely for the purpose of citation collection, it is also true that research can only be purposeful if it reaches the target audience, both within the relevant research community as well as in broader society. Moreover, several law journals that are considered ‘leading’ by the experts do not present their editors on the website, even though the editors’ names are the leading journal attribute to attract quality papers, next to the authors’ reputation and quality of previously published papers. This is an interesting fact, considering that predatory journals from questionable publishers that often do not identify the journal's editors or a formal editorial board are on the rise.Footnote 127 As publishing with modern IT support seems fairly simple, an increasing number of publishers simultaneously set up hundreds of journals in a wide range of fields that invite authors to publish with the aim of earning money, while not meeting the standards of scientific publications. Having real editors with academic reputation is a strong characteristic that differentiate serious journals from predatory ones. It is therefore important that editors’ names are clearly stated within any serious law journal, as well as on associated websites.

I have also noted that many bi-monthly law journals are published at the end of the even month and quarterly journals at the end of the quarter, rather than at the beginning, which shortens the two-year period for the collection of citations that are captured in the JIF calculation. In disciplines that are more JIF-focused, journals are published at the beginning of the relevant period or even ahead of schedule, while many continuously publish papers online until an issue is filled, thereby prolonging the period for collecting citations. Finally, the practice of using less explanatory titles for articles in legal scholarship, which only indirectly reveal their content, in comparison with the more straightforward titles used in natural sciences, could affect the visibility of articles among peers, and their resulting impact.

Conclusions and the way forward

Research work on this paper has made me realise that there are an impressive number of law journals on the market, much larger than I expected. Not all of them have equally high publication standards. While European legal scholars need to accept that there is a real need for a more uniform system of research assessment in Europe,Footnote 128 it is equally true that there is no perfect indicator of quality and that no evaluation system will ever convince every legal scholar in Europe. Pursuit of the best method of research evaluation depends very much on the academic culture within law researchers’ communities (ie whether researchers are keen to take shortcuts in terms of publishing and whether this is supported by their peers); on the level of competitiveness among legal scholars (ie whether there is often a high number of applicants for each academic position or a very limited one); on research management at the respective faculties of law (ie whether rigorous research is expected for employment assessments and promotion purposes); on the degree of financial independence of legal departments within universities (ie how much positions on bibliometrics by hard sciences influence the financial positions of law schools), and finally, on the professional strength and reputation of legal scholarship in general (ie how influential legal scholars are within the academic community). Differences between universities and countries in this respect prevent serious dialogue on legal research evaluation indicators in Europe and more widely. Nevertheless, the so-called new public management and performance-based research funding that is spreading from more developed to less developed countries is making this debate increasingly pressing, and legal scholarship is no more unique than any other research discipline.Footnote 129 Rather than comparing legal scholarship to other disciplines, it should concentrate on research quality indicators most suitable to it. It is thus necessary that European legal scholarship actively participate in establishing indicators that most comprehensively reflect research that is valuable for the legal academic community and the legal profession.

When comparing law journals in WoS and the Finnish peer review-based ranking of law journals, it was found that all law journals that are considered journals of the highest quality by legal experts are also ranked highly in WoS, despite peers not using citation statistics as the main decision-making factor. Moreover, there are many journals in the field of law with a strong international reputation which are not listed in WoS and do not have JIFs recorded, nor do citations in these journals contribute to JIFs of law journals that are listed in WoS. Besides, it was established that a high JIF, placing a law journal in Q1 of the WoS ranking, does not automatically classify the latter as the world's leading law journal according to expert judgment.

Despite the controversy of JIF and WoS among legal scholars, the majority of editors in this survey (whose law journals are not listed in WoS but which are considered ‘leading’ by experts) had no strongly held views in this respect, reflecting that even in the field of law it is increasingly accepted that metrics has its strengths and limits, just like peer review.Footnote 130 Moreover, one size is unlikely to fit all, legal scholarship being no exception. As noted by the Metric Tide Report, a mature research system needs a variable geometry of expert judgement, quantitative and qualitative indicators.Footnote 131 The first principle of the Leiden Manifesto also states that ‘quantitative metrics can challenge bias tendencies in peer review’, thereby strengthening peer review; however, ‘assessors must not be tempted to cede decision-making to the numbers’.Footnote 132 It is undoubtedly a challenge to combine the quantitative and qualitative approaches in an appropriate way.

A two-tier approach is proposed in this respect. On the one hand it would be welcoming if more European law journals could be included in WoS. Once the number of European law journals listed in WoS increases, the image of the international impact of all European law journals will improve on the basis of the snowball effect, leading to higher JIFs for those journals that are already included in WoS, as well as facilitating those reputable scholarly law journals that are still applying for inclusion to prove their international impact. It is also clear that the WoS platform needs to adhere to the principles of the Leiden Manifesto and more consistently reflect them in the criteria for selection of law journals to their core databases, in particular in respect of journals that are not published in English, law journals that have a more national focus yet adhere to the highest quality standards, as well as in respect of specialist law journals that fill narrow niches of legal scholarship and are thus very valuable without having the real potential to attract a high number of citations. Citations in books should also be included in JIF calculations to reflect a more complete journal impact.

Until the WoS selection criteria are more attuned to European legal scholarship, however, peer review-based rankings can complement the JIF-based rankings by evaluating the quality of those law journals that are sidelined by WoS. It is interesting that, in general, everyone ‘knows’ which law journals are the leading ones in certain fields of law, yet when a list is put down on paper, agreement seems to vanish. It would in fact be naive to expect such agreement. Even so, cooperation and exchange of views between various national forums of legal scholars is needed, not only in Scandinavia, where such forums are already formed, but across Europe. A single European ranking would have a higher impact upon national research councils and universities as it would reflect a European understanding of the most prestigious, internationally leading and standard quality scholarly law journals. The Finnish system of publication evaluation, with methodology in line with DORA and the Leiden Manifesto, could serve as a role model for such a project. In this way, balanced attention would be paid to the quantitative and qualitative aspects of impact.