INTRODUCTION

The genomes of four Strongyloides species (S. ratti, S. stercoralis, S. papillosus and S. venezuelensis), and two closely related species from the same evolutionary clade, the parasite Parastrongyloides trichosuri and the free-living species Rhabditophanes sp. have recently been sequenced. The genomes of each these six species have been formed into 42–60 Mb assemblies, with each containing 12 451–18 457 genes (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). The genomes of S. ratti, S. stercoralis and P. trichosuri each comprises two autosomes and an X chromosome (Bolla and Roberts, Reference Bolla and Roberts1968; Hammond and Robinson, Reference Hammond and Robinson1994), while in S. papillosus and S. venezuelensis chromosomes I and X have fused (Albertson et al. Reference Albertson, Nwaorgu and Sulston1979; Hino et al. Reference Hino, Tanaka, Takaishi, Fujii, Palomares-Rius, Hasegawa, Maruyama and Kikuchi2014); Rhabditophanes sp. has five chromosomes (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). All six genomes are AT rich, with GC values ranging from 21 to 25% in the four Strongyloides spp. to 31 and 32% in P. trichosuri and Rhabditophanes, respectively (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). The genomes have been assembled to a high-quality – the reference genome S. ratti into single scaffolds for each of the two autosomes, and the X chromosome assembled into ten scaffolds. The high-quality assembly of these genomes makes the Strongyloides species an excellent model in which to understand nematode genomics. For Strongyloides spp., the parasitic and free-living adult female stages of their life cycle are genetically identical because the parasitic female reproduces by a genetically mitotic parthenogenesis (Viney, Reference Viney1994). The differences between the parasitic and free-living adult stages are therefore due solely to differences in expression of genes of the Strongyloides genome. Because the parasitic and free-living adult stages are genetically identical, the genes and proteins upregulated in the parasitic stage, compared with the free-living stage can be directly attributed to a putative role in parasitism. Most parasitic nematode species do not have genetically identical parasitic and free-living adult stages. Strongyloides therefore offers a uniquely tractable system to study the genetic basis of nematode parasitism.

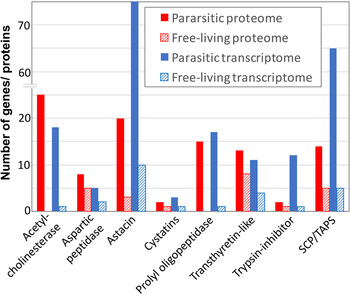

Specific gene and protein families are upregulated at different stages of the Strongyloides life cycle when compared with other life cycle stages (Fig. 1) (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). Comparisons of the transcriptome and proteome of parasitic females with the transcriptome and proteome of free-living adult female stages of the Strongyloides life cycle have revealed genes and proteins upregulated in the parasitic female, with a putative role in parasitism (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). Genes encoding two protein families – astacins and SCP/TAPS – are the most commonly upregulated gene families in the transcriptome of the parasitic adult female, when compared with the genetically identical free-living female adult stage of the life cycle. Together the astacins and SCP/TAPS gene families account for 19% of all of the genes significantly upregulated in parasitic females. An expansion in the number of the astacin and SCP/TAPS genes in Strongyloides and Parastrongyloides, when compared with a range of nematode species, coincides with the evolution of parasitism in the Strongyloides–Parastrongyloides–Rhabditophanes clade of nematodes, further highlighting their likely role in parasitism. A detailed analysis of the astacin and SCP/TAPS protein families in Strongyloides spp. has recently been published (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). Several other gene and protein families, including acetylcholinesterases (AChE), aspartic proteases (APs), prolyl oligopeptidases (POP), proteinase inhibitors (trypsin-inhibitors and cystatins) and transthyretin -like proteins (TLP), are also commonly upregulated in the proteome and transcriptome of the parasitic female suggesting that these proteins also have a putative role in Strongyloides parasitism (Fig. 2). Many of these protein families with a putative role in Strongyloides parasitism are also expressed and sometimes secreted by the parasitic stage of the life cycles of many other species of parasitic nematodes, further suggesting these families more a general role in nematode parasitism. For example, AChEs, astacins, APs, prolyl endopeptidases, proteinase inhibitors, SCP/TAPS and TLP proteins have all been associated with parasitism in parasitic species including nematodes (Lee, Reference Lee1996; Williamson et al. Reference Williamson, Brindley, Abbenante, Prociv, Berry, Girdwood, Pritchard, Fairlie, Hotez, Dalton and Loukas2002, Reference Williamson, Lustigman, Oksov, Deumic, Plieskatt, Mendez, Zhan, Bottazzi, Hotez and Loukas2006; Knox, Reference Knox2007; Asojo, Reference Asojo2011; Fajtová et al. Reference Fajtová, Štefanić, Hradilek, Dvořák, Vondrášek, Jílková, Ulrychová, McKerrow, Caffrey, Mareš and Horn2015; Lin et al. Reference Lin, Zhuo, Chen, Hu, Sun, Wang, Zhang and Liao2016). Possible roles of the protein families upregulated in parasitic females, compared with the free-living stage, are summarized in Fig. 1. These roles are based on evidence for these protein families in other parasite species, as discussed for each protein family, below.

Fig. 1. The Strongyloides life cycle and the protein families associated with the parasitic adult female, free-living adult female and third stage infective larvae (iL3), and their putative roles in nematode parasitism. The coloured boxes represent the different putative roles of protein families in parasitism, including haemoglobin proteolysis (red), penetration of host tissues and cells (orange), immunomodulation (blue) and inhibition of gut expulsion mechanisms (green). These putative roles are based on empirical evidence of proteins from parasitic nematodes and other parasites. Mostly, protein families are associated with a single putative role, apart from astacins where there is evidence for roles of astacin proteins in host tissue penetration and immunomodulation. Little is known about the role of these protein families and further investigation may reveal that other protein families also have multiple roles in parasitism. Adapted from Hunt et al. (Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). aBrindley et al. (Reference Brindley, Kalinna, Wong, Bogitsh, King, Smyth, Verity, Abbenante, Brinkworth, Fairlie, Smythe, Milburn, Bielefeldt-Ohmann, Zheng and McManus2001); Williamson et al. (Reference Williamson, Brindley, Abbenante, Prociv, Berry, Girdwood, Pritchard, Fairlie, Hotez, Dalton and Loukas2002); Sharma et al. (Reference Sharma, Eapen and Subbarao2005); bMcKerrow et al. (Reference McKerrow, Brindley, Brown, Gam, Staunton and Neva1990); Grellier et al. (Reference Grellier, Vendeville, Joyeau, Bastos, Drobecq, Frappier, Teixeira, Schrevel, Davioud-Charvet, Sergheraert and Santana2001); Bastos et al. (Reference Bastos, Grellier, Martins, Cadavid-Restrepo, de Souza-Ault, Augustyns, Teixeira, Schrével, Maigret, da Silveira and Santana2005); Williamson et al. (Reference Williamson, Lustigman, Oksov, Deumic, Plieskatt, Mendez, Zhan, Bottazzi, Hotez and Loukas2006); cMoyle et al. (Reference Moyle, Foster, McGrath, Brown, Laroche, De Meutter, Stanssens, Bogowitz, Fried and Ely1994); Zang et al. (Reference Zang, Yazdanbakhsh, Jiang, Kanost and Maizels1999); Culley et al. (Reference Culley, Brown, Conroy, Sabroe, Pritchard and Williams2000); Dainichi et al. (Reference Dainichi, Maekawa, Ishii, Zhang, Nashed, Sakai, Takashima and Himeno2001); Manoury et al. (Reference Manoury, Gregory, Maizels and Watts2001); Pfaff et al. (Reference Pfaff, Schulz-Key, Soboslay, Taylor, MacLennan and Hoffmann2002); Del Valle et al. (Reference Del Valle, Jones, Harrison, Chadderdon and Cappello2003); Asojo et al. (Reference Asojo, Goud, Dhar, Loukas, Zhan, Deumic, Liu, Borgstahl and Hotez2005); Sun et al. (Reference Sun, Liu, Li, Chen, Liu, Liu and Su2013); Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Zhuo, Chen, Hu, Sun, Wang, Zhang and Liao2016); dLee (Reference Lee1970, Reference Lee1996); Selkirk et al. (Reference Selkirk, Lazari and Matthews2005).

Fig. 2. Key gene and protein families with a putative role in parasitism showing the number of genes/ proteins in each family that are significantly upregulated in the proteome and transcriptome of parasitic adult females compared to free-living adult females of S. ratti.

While identification of protein families with putatively important roles in nematode parasitism is a major advance, understanding the specific role that they each play in parasitism is still a substantial challenge. Many of these protein families also occur in a diverse range of nematode species, including free-living nematode species, as well as a diverse range of non-nematode taxa. The members of a given protein family have likely evolved diverse functions which may include conserved roles important for a range of species and life cycle stages, as well as more specialized roles specific to nematode parasitism. Uncovering the roles of these proteins will be essential for understanding parasitism by nematodes. Understanding the role of these proteins is also important for identifying and developing drugs and other treatments to control nematode populations. Here, we consider in turn key protein families that have a putative role in parasitism in Strongyloides – AChEs, astacins, APs prolyl endopeptidases, proteinase inhibitors (trypsin inhibitors and cystatins), SCP/TAPS and TLPs (Table 1). Identification of these key protein families is based on the genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic data presented by Hunt et al. (Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). We consider the possible roles of these proteins in nematode parasitism and we present new analyses of these protein families, expanding on this recently published work.

Table 1. Summary of the genes encoding the key protein families with a putative role in parasitism in Strongyloides.

a FC – Fold change. Values represent the range of log2 fold change values for expression in the parasitic female compared with the free-living adult female transcriptome.

PROTEIN FAMILIES WITH A PUTATIVE ROLE IN PARASITISM

Proteinases

Parasites secrete proteinases and peptidases into their environment that will act on both host- and nematode-derived proteins (Tort et al. Reference Tort, Brindley, Knox, Wolfe and Dalton1999). Proteinases and peptidases make up a significant proportion of genes upregulated in the parasitic adult female stage of the S. ratti and S. stercoralis life cycle (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). The majority of these proteinases and peptidases can be categorized into key protein families. Here we discuss the largest of these families that are associated with a putative role in Strongyloides parasitism: astacins, APs and POPs.

Astacins

Astacins are zinc-metallopeptidases that require the binding of zinc in their active site for catalytic activity. They are found in diverse taxa, ranging from bacteria to mammals and have been associated with a range of functions including digestion in the crayfish (after whom they are named, Astacus astacus) and a bone-inducing factor (e.g. bone morphogenic protein) in vertebrates (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Rosen, Cordes, Hewick, Kriz, Luxenberg, Sibley and Wozney1988; Bond and Beynon, Reference Bond and Beynon1995). In nematodes, astacins have been best characterized in Caenorhabditis elegans where they have roles in cuticle biosynthesis, moulting and hatching (Hishida et al. Reference Hishida, Ishihara, Kondo and Katsura1996; Suzuki et al. Reference Suzuki, Sagoh, Iwasaki, Inoue and Takahashi2004; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Birnie, Chan, Page and Jorgensen2004; Novelli et al. Reference Novelli, Page and Hodgkin2006). Nematode cuticles are predominantly made up of collagens, and astacins play a key role in cuticle biosynthesis where they are involved in processing collagen molecules for cuticle formation (Page and Winter, Reference Page and Winter2003; Stepek et al. Reference Stepek, McCormack, Winter and Page2015). Astacins play these roles in both free-living and parasitic species and life cycle stages. However, many of the astacins coded for by the genomes of parasitic species are differentially expressed across the life cycle, suggesting that in parasitic species they have wider roles too. For example, specific sets of astacin coding genes are upregulated in infective larval stages and adult parasitic stages compared with other parasitic and free-living stages of the Strongyloides life cycle, suggesting astacins have also evolved roles specific to the parasitic lifestyle. The role of astacins in parasitic stages has been best characterized for infective larval stages where the gene expression and protein secretion of astacins has been reported in many parasitic nematodes, including Haemonchus contortus (Gamble et al. Reference Gamble, Fetterer and Mansfield1996), Onchocerca volvulus (Borchert et al. Reference Borchert, Becker-Pauly, Wagner, Fischer, Stöcker and Brattig2007), Ancylostoma caninum (Williamson et al. Reference Williamson, Lustigman, Oksov, Deumic, Plieskatt, Mendez, Zhan, Bottazzi, Hotez and Loukas2006), Dictyocaulus viviparous (Cantacessi et al. Reference Cantacessi, Gasser, Strube, Schnieder, Jex, Hall, Campbell, Young, Ranganathan, Sternberg and Mitreva2011), Teladorsagia circumcincta (Menon et al. Reference Menon, Gasser, Mitreva and Ranganathan2012), S. ratti and S. stercoralis (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). Most of the evidence for the role of astacins in nematode parasitism points to them functioning in infective larvae penetrating host skin and in subsequent tissue invasion (Williamson et al. Reference Williamson, Lustigman, Oksov, Deumic, Plieskatt, Mendez, Zhan, Bottazzi, Hotez and Loukas2006). For example, the astacin Ac-MTP-1 occurs in secretory granules of the glandular oesophagus of L3s of the dog hookworm, A. caninum suggesting that it plays a role in host infection. Recombinant Ac-MTP-1 protein (expressed in a baculovirus/insect cell system) was able to digest a range of connective tissues, including collagen and inhibition of Ac-MTP-1 function with either antiserum or the metalloprotease inhibitors EDTA and 1,10-phenanthroline greatly reduced tissue penetration by infective larvae (Williamson et al. Reference Williamson, Lustigman, Oksov, Deumic, Plieskatt, Mendez, Zhan, Bottazzi, Hotez and Loukas2006). Similarly, a role of the S. stercoralis secreted astacin, Ss40, also has tissue degradation properties (McKerrow et al. Reference McKerrow, Brindley, Brown, Gam, Staunton and Neva1990; Brindley et al. Reference Brindley, Gam, McKerrow and Neva1995).

In the genomes of Strongyloides spp. and Parastrongyloides the astacin gene family has expanded to some 184–387 astacin coding genes per species, shown by comparison with eight other species (Trichinella spiralis, Trichuris muris, Ascaris suum, Brugia malayi, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, Meloidogyne hapla, Necator americanus, C. elegans – spanning four evolutionary clades). The astacin coding gene family is the single most upregulated gene family in S. ratti and S. stercoralis parasitic adult females compared with both free-living adult females and infective third-stage larvae (iL3s) (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). The Strongyloides parasitic females reside in the mucosa of the small intestine, but rather little is known about the role of astacins at this life cycle stage. Many of the astacins expressed by parasitic females are likely to be secreted based on the prediction of a signal peptide (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016), and the identification of astacins in the secretome of Strongyloides parasitic females (Brindley et al. Reference Brindley, Gam, McKerrow and Neva1995; Soblik et al. Reference Soblik, Younis, Mitreva, Renard, Kirchner, Geisinger, Steen and Brattig2011; Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). The secretion of these proteins into their host implies that their target substrate is external to the nematode. Because astacins have key roles in tissue degradation in larvae infecting hosts, it is probable that their role in the gut of their host is also involved in tissue degradation. One possibility is that astacins are required to break down the mucosa through which the parasitic females burrow, presumably feeding as they do so. A second, non-mutually exclusive, possibility is that astacins may have evolved a role in immunomodulation, where their proteolytic role may be directed against protein components of the host immune response. Astacins present in the secretome of the hookworm N. americanus are believed to be responsible for proteolysis of eotaxin, a potent eosinophil chemo-attractant (Culley et al. Reference Culley, Brown, Conroy, Sabroe, Pritchard and Williams2000). Further investigation is required to ascertain if astacins have a similar role in immunomodulation by Strongyloides and other parasitic nematode species (Maizels and Yazdanbakhsh, Reference Maizels and Yazdanbakhsh2003).

Aspartic proteases

AP, characterized by the presence of aspartic acid residues in their active site clefts, have been identified in a diverse range of organisms (Dash et al. Reference Dash, Kulkarni, Dunn and Rao2003). In parasitic nematodes, such as H. contortus, A. caninum and N. americanus, they are thought to play a role in the digestion of host haemoglobin (Brindley et al. Reference Brindley, Kalinna, Wong, Bogitsh, King, Smyth, Verity, Abbenante, Brinkworth, Fairlie, Smythe, Milburn, Bielefeldt-Ohmann, Zheng and McManus2001; Williamson et al. Reference Williamson, Brindley, Abbenante, Prociv, Berry, Girdwood, Pritchard, Fairlie, Hotez, Dalton and Loukas2002; Jolodar et al. Reference Jolodar, Fischer, Büttner, Miller, Schmetz and Brattig2004; Sharma et al. Reference Sharma, Eapen and Subbarao2005; Balasubramanian et al. Reference Balasubramanian, Toubarro, Nascimento, Ferreira and Simões2012). Genes encoding APs are upregulated in the parasitic adult female of S. ratti and S. stercoralis compared to free-living adult female stage (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). At this stage of the Strongyloides life cycle, parasitic adults inhabit the host's intestine, an environment that unlikely requires degradation of haemoglobin. Previously, ten AP genes had been identified in S. ratti (Mello et al. Reference Mello, O'Meara, Rigden and Paterson2009). Using the recently sequenced S. ratti and S. stercoralis genome data, we have found that there are in fact a total of 53 genes encoding proteins containing an AP domain (InterPro domain IPR021109). Twelve and 17 of these genes are differentially expressed in the parasitic and free-living S. ratti adult females (six upregulated in parasitic and six upregulated in free-living females) and S. stercoralis, respectively (15 upregulated in parasitic females and two in free-living females). This indicates that different sets of AP genes are expressed at different stages of the life cycle in Strongyloides, possibly reflecting the diversification of APs in parasitic and free-living adults. Two paralogous S. ratti APs, ASP-2A and ASP-2B, which are highly expressed in parasitic and free-living females, respectively, have previously been described (Mello et al. Reference Mello, O'Meara, Rigden and Paterson2009) and molecular modelling of these suggests that they have maintained specificity for similar substrates but differ in their electrostatic charge. These differences may be an adaptation to the differences in environmental conditions encountered by parasitic and free-living stages of the life cycle (Mello et al. Reference Mello, O'Meara, Rigden and Paterson2009).

Many of the S. ratti and S. stercoralis genes that code for a protein with an AP domain and are not differentially expressed between parasitic and free-living adult females are associated with retrotransposons. Specifically, in S. ratti and S. stercoralis most of the genes coding for gene products with AP domains typically are associated with retroviruses and retrotransposons including ribonuclease H-like domain, peptidase A2A, zinc finger CCHC-type domain and intergrase catalystic core domains (Table 2). Retroviral-like and retrotransposon-associated APs are homodimeric, and an AP residue located on each molecule come together to form the active site cleft (Koelsch et al. Reference Koelsch, Mares, Metcalf and Fusek1994). The predicted folding structure of retroviral-like APs of platyhelminth and of Leishmania retroviral-like aspartic peptidase have a quaternary structure similar to that of HIV (Santos et al. Reference Santos, Garcia-Gomes, Catanho, Sodre, Santos, Branquinha and d'Avila-Levy2013; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wei, Luo, Wang, Hu and Cai2015). Because the AP inhibitors currently used as treatment against HIV (e.g. nelfinavir) have also been shown to inhibit the activity of Leishmania and Trypanosoma retroviral-like APs (Santos et al. Reference Santos, Garcia-Gomes, Catanho, Sodre, Santos, Branquinha and d'Avila-Levy2013), AP inhibitors offer a potential control treatment for nematode parasites.

Table 2. Domain combinations for the genes encoding an aspartic peptidase domain in S. ratti and S. stercoralis. Both species have a total of 53 aspartic peptidase coding genes.

Prolyl oligopeptidases (POPs)

POP (also known as prolyl endopeptidase or PEP) enzymes are 70–80 kDa in size and belong to the S9 family of serine peptidases that cleave peptides at internal proline residues (Gass and Khosla, Reference Gass and Khosla2007). A common feature of POP enzymes is that they only cleave peptides up to 30 residues in length, such as neurotransmitters and hormones (Camargo et al. Reference Camargo, Caldo and Reis1979). In S. ratti and S. stercoralis there are 23 and 17 genes, respectively, predicted to code for a POP, based on the predicted presence of a peptidase S9 prolyl oligopeptidase domain (Pfam ID PF00326). Of these genes, 18 and 11 are upregulated in the parasitic female transcriptome, compared with the free-living transcriptome for S. ratti and S. stercoralis, respectively. Several of these upregulated POPs have the greatest differential levels of expression between parasitic and free-living stages (Table 1). The role of POPs in parasitism is best characterized in Trypanosoma, Leishmania and Schistosoma (Bastos et al. Reference Bastos, Motta, Grellier and Santana2013). For example, the T. cruzi POP, Tc80, is thought to have a role in facilitating entry of the trypanosomes into the mammalian host cells (Grellier et al. Reference Grellier, Vendeville, Joyeau, Bastos, Drobecq, Frappier, Teixeira, Schrevel, Davioud-Charvet, Sergheraert and Santana2001; Bastos et al. Reference Bastos, Grellier, Martins, Cadavid-Restrepo, de Souza-Ault, Augustyns, Teixeira, Schrével, Maigret, da Silveira and Santana2005). In Schistosoma, POPs are also important in parasitism, shown by in vitro experiments where recombinant S. mansoni POP, smPOP, cleaves small host-derived peptides such as the vascoregulatory hormones angiotensin I and bradykinin. This suggests a possible role of POPs in modulating the host vascular system (Fajtová et al. Reference Fajtová, Štefanić, Hradilek, Dvořák, Vondrášek, Jílková, Ulrychová, McKerrow, Caffrey, Mareš and Horn2015). Less is known about the role of POPs in nematodes, and especially in parasitic species.

We have identified genes predicted to encode a peptidase S9 prolyl oligopeptidase domain (Pfam ID PF00326) in 14 nematode species (four Strongyloides spp., Parastrongyloides, Rhabditophanes and eight species, as above), with between 5 and 18 such genes in each of the eight other species. In the C. elegans genome, we identified six genes that are predicted to encode a POP, but the function of POPs in C. elegans and other nematodes is not understood. In, the Strongyloides–Parastrongyloides–Rhabditophanes clade each species had 8–23 POP. Genes encoding POPs have previously been associated with parasitism based on genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic data of parasitic nematode species including S. ratti (Soblik et al. Reference Soblik, Younis, Mitreva, Renard, Kirchner, Geisinger, Steen and Brattig2011; Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016), S. stercoralis, P. trichosuri, Dirofilaria immitis (Mitreva et al. Reference Mitreva, McCarter, Martin, Dante, Wylie, Chiapelli, Pape, Clifton, Nutman and Waterston2004) and T. muris (Mitreva et al. Reference Mitreva, Jasmer, Zarlenga, Wang, Abubucker, Martin, Taylor, Yin, Fulton, Minx, Yang, Warren, Fulton, Bhonagiri, Zhang, Hallsworth-Pepin, Clifton, McCarter, Appleton, Mardis and Wilson2011). The presence of a β-propeller domain (InterPro domain IPR004106) has been associated with genes encoding a POP-domain in parasitic species (S. ratti, P. trichosuri and D. immitis) (Mitreva et al. Reference Mitreva, McCarter, Martin, Dante, Wylie, Chiapelli, Pape, Clifton, Nutman and Waterston2004). The β-propeller domain is associated with ligand binding, oxidoreductase and hydrolase (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Chan and Wang2011) and, more generally, β-propeller domains are thought to exclude larger peptides from the POP active site, thus protecting them from proteolysis in the cytosol (Fülöp et al. Reference Fülöp, Böcskei and Polgár1998). Among the S. ratti and S. stercoralis POPs, 21 and 14, respectively, are predicted to contain a β-propeller domain, most of which (15 of 16 and all 11 in S. ratti and S. stercoralis, respectively) are upregulated in the parasitic female stage when compared to free-living adult females. A β-propeller domain has also been identified in the Schistosoma smPOP (Fajtová et al. Reference Fajtová, Štefanić, Hradilek, Dvořák, Vondrášek, Jílková, Ulrychová, McKerrow, Caffrey, Mareš and Horn2015) and Tc80 of T. brucei. It is not known if POPs with a β-propeller have a specific role in parasitism and, if so, what this role is.

Proteinase inhibitors

Proteinases are an important component of the host immune defence against parasites. There is strong evidence that proteinase inhibitors are secreted by parasitic nematodes to counteract attack by host proteinases, therefore providing the parasite with protection from the effects of the host digestive system and the immune response (Knox, Reference Knox2007). Proteinase inhibitors are secreted by hematophagous parasites to facilitate feeding within the host environment – for example A. caninum secretes the anticoagulant proteinase inhibitors anticoagulant peptide (AcAP) and hookworm platelet inhibitor (HPI) (Cappello et al. Reference Cappello, Vlasuk, Bergum, Huang and Hotez1995; Stassens et al. Reference Stassens, Bergum, Gansemans, Jespers, Laroche, Huang, Maki, Messens, Lauwereys, Cappello, Hotez, Lasters and Vlasuk1996; Del Valle et al. Reference Del Valle, Jones, Harrison, Chadderdon and Cappello2003). In Strongyloides proteinase inhibitors including trypsin inhibitors and cystatins are upregulated in the transcriptome and proteome of parasitic females, compared with free-living adult females. These proteinase inhibitors potentially have a role in parasitism in Strongyloides, possibly modulating the host immune response.

Proteinase inhibitors can be categorized into two classes based on their interaction with a target proteinases: (i) irreversible high-binding interactions and (ii) reversible interactions (Rawlings et al. Reference Rawlings, Tolle and Barrett2004; Knox, Reference Knox2007). Proteinase inhibitors that irreversibly interact with their targets are endopeptidases and include the serine proteinase inhibitors (serpins) and the nematode-specific smapins family. Serpins are found in a diverse range of animals, plants and viruses (Irving, Reference Irving2000) and are the largest known family of proteinase inhibitors (Law et al. Reference Law, Zhang, McGowan, Buckle, Silverman, Wong, Rosado, Langendorf, Pike, Bird and Whisstock2006; Rawlings et al. Reference Rawlings, Barrett and Bateman2010). The serpins are named after their most common function which is to inhibit serine proteases. However, some serpins also inhibit other proteases such as caspases and cysteine proteases (Ray et al. Reference Ray, Black, Kronheim, Greenstreet, Sleath, Salvesen and Pickup1992; Irving et al. Reference Irving, Pike, Dai, Brömme, Worrall, Silverman, Coetzer, Dennison, Bottomley and Whisstock2002), or have non-inhibitory roles such as hormone transporters in inflammation (Pemberton et al. Reference Pemberton, Stein, Pepys, Potter and Carrell1988). Serpins interact with their target substrate via conformational change which inhibits the protease (Huntington et al. Reference Huntington, Read and Carrell2000). This involves a scissile bond on a reactive-site loop near the C-terminus that traps the protease. The protease cleaves this loop but remains attached to the serpin via an active site serine. In this process the structure of the protease is disrupted and becomes susceptible to degradation (Huntington et al. Reference Huntington, Read and Carrell2000; Zang and Maizels, Reference Zang and Maizels2001). Because these inhibitors act irreversibly and can only inhibit a protease once they are often referred to as ‘suicide’ or ‘single use’ inhibitors (Law et al. Reference Law, Zhang, McGowan, Buckle, Silverman, Wong, Rosado, Langendorf, Pike, Bird and Whisstock2006).

Little is known about the role of serpins in nematode parasitism. The B. malayi serpin Bm-SPN-2 is expressed in the blood-dwelling microfilariae stage. Screening of potential target mammalian serine proteinases revealed that Bm-SPN-2 inhibits human neutrophil-derived proteinases cathepsin G and elastase (Zang et al. Reference Zang, Yazdanbakhsh, Jiang, Kanost and Maizels1999). Similarly, the serpin Anisakis simplex serpin (ANISERP) also inhibits cathepsin G, as well as the human blood clotting serine protease thrombin and the digestive serine protease trypsin (Valdivieso et al. Reference Valdivieso, Perteguer, Hurtado, Campioli, Rodríguez, Saborido, Martínez-Sernández, Gómez-Puertas, Ubeira and Gárate2015). In S. ratti, and S. stercoralis there are 12 and 10 genes, respectively, encoding serpins belonging to the trypsin-inhibitor protein family which are significantly upregulated in the parasitic female transcriptome when compared to the free-living female transcriptome. These genes have some of the highest relative differences in expression levels suggesting they have an important role in parasitism. Further investigation is required to identify the targets of Strongyloides serpins and if the target is host-derived.

The second type of proteinase inhibitor are those that reversibly interact with their targets, characterized by binding to the active site of a protease with high affinity. These proteinase inhibitors are commonly found in the secretome of parasitic nematodes (Knox, Reference Knox2007). For example, cystatins are a subfamily of the cysteine proteinase inhibitors, which reversibly block the active site of a target cysteine protease. In parasitic nematodes there is evidence that cystatins play a role in the modulation of the host anti-nematode response (Hartmann et al. Reference Hartmann, Schönemeyer, Sonnenburg, Vray and Lucius2002; Maizels and Yazdanbakhsh, Reference Maizels and Yazdanbakhsh2003), including antigen presentation, T cell responses and nitric oxide production (Dainichi et al. Reference Dainichi, Maekawa, Ishii, Zhang, Nashed, Sakai, Takashima and Himeno2001; Manoury et al. Reference Manoury, Gregory, Maizels and Watts2001; Pfaff et al. Reference Pfaff, Schulz-Key, Soboslay, Taylor, MacLennan and Hoffmann2002; Shaw et al. Reference Shaw, McNeill, Maass, Hein, Barber, Wheeler, Morris and Shoemaker2003; Knox, Reference Knox2007). For example, in Heligmosomoides polygyrus, a recombinant cystatin protein is able to modulate differentiation and activation of bone-marrow-derived CD11c+ dendritic cells (Sun et al. Reference Sun, Liu, Li, Chen, Liu, Liu and Su2013). In the host antigen-presenting cells there are two key pathways involving cystatins (cysteine protease-dependent degradation of proteins to antigenic peptides, and the presentation of the MHC class II complex to T cells, which is partly regulated by cysteine proteases that cleave the MHC class II associated invariant chain), and these pathways are potential targets for parasite-derived cystatins to modulate the host immune response (Hartmann and Lucius, Reference Hartmann and Lucius2003). Using the genome and transcriptome data for S. ratti and S. stercoralis (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016) we have identified three S. ratti genes and one S. stercoralis gene encoding cystatin proteins which are upregulated in parasitic females compared with free-living adult females suggesting they have an important role in the parasitic life style. The Strongyloides upregulated cystatin-encoding genes were identified by the predicted presence of a cystatin domain (InterPro domain IPR000010), but they otherwise have no significant sequence homology with known nematode cystatins. Further investigation is required into these Strongyloides proteins to identify if they represent a novel group of immunomodulators.

SCP/TAPS

The sperm-coating protein (SCP)-like extracellular proteins, also known as SCP/Tpx-1/Ag5/PR-1/Sc7 (SCP/TAPS) belong to the cysteine-rich secretory proteins (CRISP) superfamily of proteins. The SCP/TAPS are characterized by the presence of one or two cysteine-rich secretory proteins, antigen 5, and pathogenesis-related 1 proteins (CAP) domains (InterPro domain IPR014044, Pfam ID PF00188). These proteins are found in a diverse range of organisms, including parasitic nematodes, where they are also known by various other names including the venom allergen-like (VAL) (Hewitson et al. Reference Hewitson, Harcus, Murray, van Agtmaal, Filbey, Grainger, Bridgett, Blaxter, Ashton, Ashford, Curwen, Wilson, Dowle and Maizels2011) and Ancylostoma-secreted proteins (ASP) (Asojo, Reference Asojo2011). In S. ratti and S. stercoralis, the SCP/TAPS are the second most commonly upregulated protein family in the adult female parasitic female after the astacins (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016) and are secreted by the parasitic female stage (Soblik et al. Reference Soblik, Younis, Mitreva, Renard, Kirchner, Geisinger, Steen and Brattig2011; Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016).

The first reported nematode SCP/TAPS protein was Ac-ASP-1 identified in the secretome of A. caninum infective larvae (Hawdon et al. Reference Hawdon, Jones, Hoffman and Hotez1996). SCP/TAPS have since been identified in the secretome of a range of parasitic nematodes suggesting they have an important role in parasitism (Cantacessi and Gasser, Reference Cantacessi and Gasser2012). The role of SCP/TAPS in parasitism is poorly understood. The best example for a role of SCP/TAPS in nematode parasitism is in hookworms, where there is evidence for a role in immunomodulation. Specifically, in A. caninum, the SCP/TAPS protein known as neutrophil inhibitory factor inhibits neutrophil adhesion to vascular endothelial cells in vitro by selective binding to the integrin CD11b/CD18, thus inhibiting neutrophil function and the release of hydrogen peroxide from activated neutrophils (Moyle et al. Reference Moyle, Foster, McGrath, Brown, Laroche, De Meutter, Stanssens, Bogowitz, Fried and Ely1994). Secondly, HPI, inhibits in vitro platelet aggregation and adhesion by impeding the function of cell surface intergins (Del Valle et al. Reference Del Valle, Jones, Harrison, Chadderdon and Cappello2003). In N. americanus, the SCP/TAPS protein, Na-ASP-2, has structural and charge similarities to CC-chemokines, which are involved in inducing the migration of immune cells such as monocytes and dendritic cells (Asojo et al. Reference Asojo, Goud, Dhar, Loukas, Zhan, Deumic, Liu, Borgstahl and Hotez2005).

Among four Strongyloides spp. a total of 89–205 genes are predicted to encode SCP/TAPS coding proteins. Comparing these to eight outgroup species (as above), there is an expansion of the SCP/TAPS coding gene family in Strongyloides and Parastrongyloides but not in Rhabditophanes suggesting an expansion of SCP/TAPS protein coding genes coincided with the evolution of parasitism in the Strongyloides clade (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). Interestingly, as for the astacin gene family, the SCP/TAPS gene family is also expanded in N. americanus (Tang et al. Reference Tang, Gao, Rosa, Abubucker, Hallsworth-Pepin, Martin, Tyagi, Heizer, Zhang, Bhonagiri-Palsikar, Minx, Warren, Wang, Zhan, Hotez, Sternberg, Dougall, Gaze, Mulvenna, Sotillo, Ranganathan, Rabelo, Wilson, Felgner, Bethony, Hawdon, Gasser, Loukas and Mitreva2014; Schwarz et al. Reference Schwarz, Hu, Antoshechkin, Miller, Sternberg and Aroian2015) but phylogenetic analysis suggests that the hookworm expansion of the number of SCP/TAPS coding genes is independent to that of the Strongyloides–Parastrongyloides clade (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016).

Transthyretin-like proteins (TLP)

TLP have some of the highest relative levels of gene expression in S. ratti and S. stercoralis adult parasitic females, compared with that of free-living adult females (Table 1) (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). This protein family, also sometimes referred to as transthyretin-like (TTL or TTR-like) proteins, is only found in nematodes and is distinct from the transthyretin-related proteins (TRPs, and sometimes also referred to as TLPs) which are found across a wide range of prokaryotic and eukaryotic taxa (Sauer-Eriksson et al. Reference Sauer-Eriksson, Linusson, Lundberg, Richardson and Cody2009). The TLPs are distantly related to TTRs, plasma proteins in vertebrates that transport thyroid hormones (Power et al. Reference Power, Elias, Richardson, Mendes, Soares and Santos2000), though only a low level of sequence homology has been found among the TTRs, TRPs and TLPs. TRPs, along with uricase and 2-oxo-4-hydroxy-4-carboxy-5-ureidoimidazoline (OHCU) decarboxylase, have been associated with a role in the oxidation of uric acid to allantoin (Ramazzina et al. Reference Ramazzina, Folli, Secchi, Berni and Percudani2006), however, less is known about the role of TLPs. TLPs were originally discovered in C. elegans (Sonnhammer and Durbin, Reference Sonnhammer and Durbin1997) where the TLP, TTR-52, is involved in the recognition and subsequent engulfment of apoptopic cells. Expression of TTR-52 fluorescent protein constructs and C. elegans mutant analysis has shown that TTR-52 aggregates around apoptopic cells and binds to surface-exposed phosphatidylserine, a known ‘eat me’ signal for apoptopic cells. TTR-52 also binds to the CED-1 phagocyte receptor, acting as a bridging molecule to mediate phagocytosis of apoptopic cells (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Li, Zhao, Liu, Shi, Chen, Yang, Guo, Geng, Shang, Peden, Kage-Nakadai, Mitani and Xue2010). Similarly, the TTRs in vertebrates also have a binding role, together suggesting that binding to molecules could be a conserved role of TLPs, although the target molecules they have evolved to bind to may have diverged among different taxa. One can envisage that in parasitic nematodes, binding of host molecules is likely to be an important function in a parasitic lifestyle.

The TLPs have been identified in the secretome, and are upregulated in the transcriptome, of parasitic stages for a number of nematodes species including A. caninum (Mulvenna et al. Reference Mulvenna, Hamilton, Nagaraj, Smyth, Loukas and Gorman2009), B. malayi (Hewitson et al. Reference Hewitson, Harcus, Curwen, Dowle, Atmadja, Ashton, Wilson and Maizels2008), A. suum (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Van Steendam, Dhaenens, Vlaminck, Deforce, Jex, Gasser and Geldhof2013), H. contortus (Schwarz et al. Reference Schwarz, Korhonen, Campbell, Young, Jex, Jabbar, Hall, Mondal, Howe, Pell, Hofmann, Boag, Zhu, Gregory, Loukas, Williams, Antoshechkin, Brown, Sternberg and Gasser2013), Radopholus similis (Jacob et al. Reference Jacob, Vanholme, Haegeman and Gheysen2007) and Litomosoides sigmodontis (Armstrong et al. Reference Armstrong, Babayan, Lhermitte-Vallarino, Gray, Xia, Martin, Kumar, Taylor, Blaxter, Wastling and Makepeace2014). This suggests that TLPs are universally important in nematode parasitism. Little is known about the role of TLPs in nematodes other than C. elegans, and it is not known if the TLPs associated with nematode parasitism have a similar molecular-binding role. The plant parasite nematode Meloidogyne javanica secretes the TLP protein MjTTL5. Yeast two-hybrid protein–protein interaction screens have revealed that MjTTL5 interacts with the Arabidopsis thaliana protein ferredoxin: thioredoxin reductase catalytic subunit (AtFTRc), the expression of which is induced by infection with M. javanica. The AtFTRc protein is an important component of the host antioxidant system that is deployed by plants as part of their infection defence mechanism. It is hypothesized that MjTTL5 causes a conformational change in AtFTRc that results in the reduction of reactive oxygen species in the host, enhancing nematode parasitism (Lin et al. Reference Lin, Zhuo, Chen, Hu, Sun, Wang, Zhang and Liao2016). MjTTL5 is the best characterized parasitic nematode TLP to date. More research is required to identify the binding targets, if any, of TLPs in parasitic nematodes that infect animals. This is particularly important because TLPs are potentially interesting as a vaccine or drug target because they only occur in nematodes, thereby facilitating chemotherapeutic specificity.

Acetylcholinesterases

Cholinesterases are serine esterases that preferentially hydrolyse choline esters, and are members of a large family of related esterases and lipases which share a core arrangement of eight beta sheets connected by alpha helices (the alpha/beta hydrolase fold) (Ollis et al. Reference Ollis, Cheah, Cygler, Dijkstra, Frolow, Sybille, Harel, James Remington, Silman, Schrag, Sussman, Koen and Goldman1992). Vertebrate cholinesterases can be distinguished by their substrate specificity; for example, AChE hydrolyses acetylcholine (ACh), the major excitatory neurotransmitter, which is common to most animals, including nematodes (Selkirk et al. Reference Selkirk, Lazari and Matthews2005). A key feature of AChEs is that the catalytic triad (S200, H440, E327, numbering based on the Torpedo californica enzyme) is located at the base of a 20 angstrom-deep narrow gorge which extends halfway into the enzyme (Sussman et al. Reference Sussman, Harel, Frolow, Oefner, Goldmant, Toker and Silman1991). The gorge is lined by the rings of 14 aromatic residues; most of which can be assigned functional roles. Of these, W84 is critical for enzymatic activity, as both it and F330 form part of the ‘anionic’ (choline) binding site, which orients the substrate in the active site.

ACh controls motor activities such as locomotion, feeding and excretion in nematodes (Segerberg and Stretton, Reference Segerberg and Stretton1993; Rand and Nonet, Reference Rand, Nonet, Riddle, Blumenthal, Meyer and Priess1997), and thus AChE plays a crucial role in regulation. Among nematodes, AChE coding genes have been most thoroughly characterized in the free-living nematode C. elegans, which has four AChE coding genes: ace-1–4. Homozygous mutants of individual ace loci result in slight defects in locomotion, or have no phenotypic effect. However, ace-1–2 double-mutant worms are severely uncoordinated, and ace-1–3 triple mutants have a lethal phenotype, suggesting that although the ace genes have essential functions and are required for viability it is possible that ace-1 and ace-2 can assume the function normally carried out by ace-3 (Culotti et al. Reference Culotti, Von Ehrenstein, Culotti and Russell1981; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Duckett, Culotti, Herman, Meneely and Russell1981, Reference Johnson, Rand, Herman, Stern and Russell1988; Kolson and Russell, Reference Kolson and Russell1985). Green fluorescent protein (GFP) localization studies of the ace-1–3 products show that each gene has a distinct pattern of expression, though with some areas where expression is overlapping (Culetto et al. Reference Culetto, Combes, Fedon, Roig, Toutant and Arpagaus1999; Combes et al. Reference Combes, Fedon, Grauso, Toutant and Arpagaus2000). There is little evidence of expression for ace-4 and it is likely to code for a redundant protein.

Neuromuscular AChEs of parasitic nematodes are much more ill-defined. In addition to expression of neuromuscular AChEs, many parasitic nematodes release variants of these enzymes from specialized secretory glands (Ogilvie et al. Reference Ogilvie, Rothwell, Bremmer, Schnitzerling, Nolan and Keith1973), and this property appears to be restricted to parasitic nematodes which colonize mucosal surfaces (Selkirk et al. Reference Selkirk, Lazari and Matthews2005). These secretory enzymes have been best characterized in Nippostrongylus brasiliensis and D. viviparus. N. brasiliensis secretes three distinct AChEs encoded by separate genes (Hussein et al. Reference Hussein, Chacón, Smith, Tosado-Acevedo and Selkirk1999, Reference Hussein, Smith, Chacon and Selkirk2000, Reference Hussein, Harel and Selkirk2002). Two secreted AChEs from D. viviparus have been characterized (Lazari et al. Reference Lazari, Hussein, Selkirk, Davidson, Thompson and Matthews2003), although this parasite secretes variants which may be encoded by additional genes (McKeand et al. Reference McKeand, Knox, Duncan and Kennedy1994). All of the secreted AChEs take the form of hydrophilic monomers, and analysis of substrate specificity and sensitivity to inhibitors indicates that they can all be classified as true AChEs (Selkirk et al. Reference Selkirk, Lazari and Matthews2005). The rationale for secretion of multiple forms is unclear, since they display similar substrate specificities and pH optima.

The exact role of AChEs in nematode parasitism is still unclear. In mammals, ACh is a key neurotransmitter involved in the regulation of gut peristalsis. It is likely that parasitic nematodes secrete AChE in order to neutralize host cholinergic signalling, with this signalling normally promoting physiological responses (smooth muscle contraction, mucus and fluid secretion by goblet cells and enterocytes, and effects on the immune system) which contribute to parasite expulsion (Selkirk et al. Reference Selkirk, Lazari and Matthews2005). For example, it has been proposed that N. brasiliensis’ release of AChE into the host gut reduces local intestinal wall spasm and reduces peristalsis, thus providing a more stable environment for N. brasiliensis to inhabit (Lee, Reference Lee1970, Reference Lee1996). Parasitic nematode-derived AChE may inhibit the release of host intestinal mucus. ACh is also involved in inflammatory immune responses (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Yu, Ochani, Amella, Tanovic, Susarla, Li, Wang, Yang, Ulloa, Al-Abed, Czura and Tracey2003; Tracey, Reference Tracey2009) and has recently been shown to act as a co-stimulatory signalling molecule for CD4+ T cell activation and cytokine production in mice during N. brasilensis infection (Darby et al. Reference Darby, Schnoeller, Vira, Culley, Bobat, Logan, Kirstein, Wess, Cunningham, Brombacher, Selkirk and Horsnell2015). The host anti-nematode immune response is therefore also a potential target of parasitic-nematode derived AChEs.

Strongyloides ratti and S. stercoralis have 24 and 28 AChE coding genes, respectively, of which 17 and 24 were upregulated in the adult parasitic female stage (whereas only 1 and 0 were comparatively upregulated in the free-living female) (Table 1, Fig. 2.). We have resolved the phylogeny of AChE genes in 14 nematode species, including four Strongyloides species, P. trichosuri and Rhabditophanes sp. (from the same evolutionary clade) and eight outgroup species (as above) encompassing four further nematode clades (Fig. 3). AChEs coding genes were identified by the presence of a predicted cholinesterase protein domain (InterPro domain IPR000997) and the phylogeny was determined using the method described by Hunt et al. (Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). The phylogeny shows an expansion of the cholinesterase gene family in Strongyloides and Parastrongyloides compared with the other nematode species (Fig. 3). The expanded cholinesterase-like genes are all predicted to encode proteins with truncated C-termini, characteristic of secreted AChEs. The number of these genes in Strongyloides and Parastrongyloides are remarkable: 178 genes between 5 Strongyloides and Parastrongyloides species, with 80 representatives for P. trichosuri alone.

Fig. 3. The phylogeny of acetylcholinesterases from 14 nematode species including four Strongyloides species (red) and two species, Parastrongyloides (orange) and Rhabditophanes (pink), from the same evolutionary clade as Strongyloides. The four acetylcholinesterases, ACE 1–4, in the C. elegans genome are marked on the phylogeny. Acetylcholinesterases from Strongyloides and Parastrongyloides were categorized into eight distinct groups based on clustering in the phylogeny. The scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions. The phylogeny also includes genes predicted to encode acetylcholinesterases for eight further species of nematode including Caenorhabditis elegans (black), Necator americanus (brown), Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (light green), Trichinella spiralis (light blue), Trichuris muris (blue), Brugia malayi (navy blue), Ascaris suum (purple), and Meloidogyne hapla (dark green).

The expansion of the AChE family has not occurred in the closely related free-living nematode Rhabditophanes, which only possess two AChE coding genes. Many of the genes in the expanded AChE gene family are upregulated in the parasitic stage of S. ratti and S. stercoralis suggesting that, like the astacins and SCP/TAPS, the expansion of the AChE coding gene family has coincided with the evolution of parasitism in the Strongyloides–Parastrongyloides–Rhabditophanes clade and has a role in parasitism. All Strongyloides and Parastrongyloides species were observed to possess one sequence encoding a protein closely related to C. elegans ACE-1, ACE-2 and ACE-3/4, respectively. The nematode sequences which cluster with C. elegans ACE-1 show features characteristic of this enzyme and tailed forms in general. The sequences, which cluster with ACE-2 show similar conservation of the key amino acids required for disulphide bonds, the catalytic triad, and generally thirteen of the fourteen aromatic residues, which line the active site gorge. A key feature of these predicted proteins is that many have a hydrophobic C-terminus with signals for peptide cleavage and GPI addition, analogous to C. elegans ACE-2. The same is true of the sequences which cluster with ACE-3/ACE-4, and key residues are particularly well conserved in this group. In summary, most parasitic nematodes examined appear to mirror C. elegans in possessing genes for one tailed and two hydrophobic AChEs, and in all likelihood these represent neuromuscular enzymes which perform analogous functions to their C. elegans counterparts. In comparison to the AChE coding genes that have expanded in Strongyloides and Parastrongyloides, the expression of the S. ratti and S. stercoralis AChE coding genes most closely related to the C. elegans ace 1–4 genes were not upregulated in the parasitic or free-living stages of the Strongyloides life cycle (Fig. 3).

We classified the members of the Strongyloides–Parastrongyloides expanded cholinesterase-like gene family into eight groups, based on the phylogeny shown in Fig. 3. The vast majority have cysteine residues in the correct position to form the three intramolecular disulphide bonds, and features of the active site gorge characteristic of cholinesterases. However, closer examination reveals that almost all of the predicted proteins are likely to be enzymatically inactive, with the exception of those in group 1. The group 1 predicted protein sequences possess the necessary key residues for AChE activity. Groups 2, 3 and 4 lack S200 or have modifications around this residue that would render the enzymes inactive. The consensus sequence around the active site serine in cholinesterases is FGESAG. Mutation of S200 generates loss of activity (Gibney et al. Reference Gibney, Camp, Dionne, MacPhee-Quigley and Taylor1990; Shafferman et al. Reference Shafferman, Velan, Ordentlich, Kronman, Grosfeld, Leitner, Flashner, Cohen, Barak and Ariel1992), and mutation of E199 reduces it. Most Parastrongyloides genes in group 2 also lack E327, approximately half of the sequences in group 3 lack H440, and mutations of these residues also render AChEs inactive (Radić et al. Reference Radić, Gibney, Kawamoto, MacPhee-Quigley, Bongiorno and Taylor1992; Shafferman et al. Reference Shafferman, Velan, Ordentlich, Kronman, Grosfeld, Leitner, Flashner, Cohen, Barak and Ariel1992). Almost all group 6 sequences are predicted to retain F330 in the choline-binding site, but show altered residues around S200: many sequences predict the consensus FGTSSG rather than FGESAG, which would likely severely reduce catalytic efficiency (Radić et al. Reference Radić, Gibney, Kawamoto, MacPhee-Quigley, Bongiorno and Taylor1992). Group 5 sequences show relatively poor conservation of active site gorge aromatic residues. All group 6 predicted sequences have a W84Y substitution. W84 is considered a signature of cholinesterases, as the quaternary nitrogen groups of the substrate are stabilized by cation–aromatic interactions. Nevertheless, cholinesterases substituted with smaller aromatic residues such as tyrosine and phenylalanine at this site retain activity, albeit reduced several-fold (Ordentlich et al. Reference Ordentlich, Barak, Kronman, Ariel, Segall, Velan and Shafferman1995; Loewenstein-Lichtenstein et al. Reference Loewenstein-Lichtenstein, Glick, Gluzman, Sternfeld, Zakut and Soreq1996). Proteomic analysis has identified twenty cholinesterase-like sequences in the secretome of adult female parasitic S. ratti, none of which were present in secreted products of free-living adult females (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). Of these, only SRAE_1000291800 from group 1 is predicted to encode an active AChE. Ten of the sequences are from group 6: of these, five have the sequence FGTSSG and five have FGTGTG around the active site serine and are thus most likely enzymatically inactive. The other secreted proteins are from groups 2, 4 and 5.

The presence of large numbers of these genes in the genomes of Strongyloides and Parastrongyloides, that these genes are transcribed and (from S. ratti and S. stercoralis, data) specifically in the parasitic female stage, and (from S. ratti proteomic data) that many result in proteins, sits oddly with most of these not coding for functional cholinesterases. It is possible that these proteins could have quite different, perhaps novel, roles. It is notable that cholinesterases are thought to have a wider variety of non-enzymatic roles, such as in cellular differentiation, adhesion and morphogenesis (Grisaru et al. Reference Grisaru, Sternfeld, Eldor, Glick and Soreq1999; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Rand, Herman, Stern and Russell1988), and such roles might be compatible with how Strongyloides exploits host mucosal tissue during its parasitic phase.

DISCUSSION

The continued advances in next generation sequencing have led to a great increase in the number of sequenced parasitic nematodes genomes that are available. These data, along with high quality data on the transcriptomes and proteomes of different life cycle stages of parasitic nematodes has enabled predictions of genes and proteins with possible roles in parasitism. We have discussed the protein families with a putative role in parasitism based on evidence that these proteins are upregulated in the transcriptome and proteome of the parasitic stage of the life cycle, compared with the genetically identical free-living stage. Some of these protein families are now under further investigation as potential vaccine targets against nematode infection, including members of the astacin (Nisbet et al. Reference Nisbet, McNeilly, Wildblood, Morrison, Bartley, Bartley, Longhi, McKendrick, Palarea-Albaladejo and Matthews2013; Page et al. Reference Page, Stepek, Winter and Pertab2014), SCP/TAPS (Goud et al. Reference Goud, Bottazzi, Zhan, Mendez, Deumic, Plieskatt, Liu, Wang, Bueno, Fujiwara, Samuel, Ahn, Solanki, Asojo, Wang, Bethony, Loukas, Roy and Hotez2005), AP (Loukas et al. Reference Loukas, Bethony, Mendez, Fujiwara, Goud, Ranjit, Zhan, Jones, Bottazzi and Hotez2005) and cystatin (Arumugam et al. Reference Arumugam, Zhan, Abraham, Ward, Lustigman and Klei2014) protein families. Proteins with a role in parasitism are also key targets for the development of anthelminthic drugs (Page et al. Reference Page, Stepek, Winter and Pertab2014), and as immunomodulatory drugs for autoimmune disease such as asthma and colitis (Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Taylor, O'Gorman, Balic, Barr, Filbey, Anderton and Maizels2010; Whelan et al. Reference Whelan, Hartmann and Rausch2012; Maizels et al. Reference Maizels, McSorley and Smyth2014).

There are still big gaps in our knowledge. Our understanding of the role played by many of these proteins in the parasitic nematode lifestyle, and their targets, if any, within the host are still largely unknown. With the exception of the TLP family, which is only found in nematodes, many of the protein families likely to play an important role in nematode parasitism have been identified across a diverse array of nematode and non-nematode taxa. In many cases, these protein families have a diversity of roles. For example, the SCP/TAPS are not only found in nematodes, but also in plants and animals, where they have been implicated in plant pathogen defence, as components of insect and snake venom, in sperm maturation and male reproduction in insects and mammals, and the development of fibrosis (Cantacessi et al. Reference Cantacessi, Campbell, Visser, Geldhof, Nolan, Nisbet, Matthews, Loukas, Hofmann, Otranto, Sternberg and Gasser2009). Thus, identifying the family to which a protein belongs is not necessarily informative about the roles that they might have in nematode parasitism. The proteins involved in nematode parasitism may have evolved new functions, which may be novel to a particular species, genus or clade of parasitic nematodes.

Many Strongyloides proteins/genes, especially for the protein families discussed here, have the greatest expression in the parasitic stage, compared with the free-living stage, and these proteins are key candidates for proteins involved in parasitism. Of these proteins, many are likely to be secreted into their host based on the prediction of a signal peptide domain in their protein sequence and the presence of these proteins in the secretome (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). The secretion of these proteins is important because proteins that have a role in parasitism are likely to interact directly with their host, for example interacting with components of the host's immune system or other host molecules that are in close association with the parasite in its within-host niche (Hewitson et al. Reference Hewitson, Grainger and Maizels2009). Secreted proteins that are highly expressed in parasitic females compared with free-living females, therefore offer the best candidates for further investigation into their role in parasitism.

Empirical studies are now required to investigate the role, if any, that these Strongyloides proteins have in parasitism. For example, measuring the effect of parasite proteins on immune responses will identify if a protein has immunomodulatory properties (McSorley et al. Reference McSorley, Hewitson and Maizels2013). Another avenue of research that will be important for uncovering the functions and roles of parasite proteins, is transgenic studies. Transgenic techniques have been established in few parasitic nematode species. Recent developments in transgenic techniques for S. ratti and S. stercoralis will now enable the expression patterns of proteins involved in parasitism to be investigated (Li et al. Reference Li, Shao, Junio, Nolan, Massey, Pearce, Viney and Lok2011; Shao et al. Reference Shao, Li, Nolan, Massey, Pearce and Lok2012; Lok, this issue). Strongyloides spp. therefore offer exciting opportunities to further explore the role of protein families with a putative role in parasitism. Furthermore, the potential application of knock-down and knock-in techniques for parasitic nematodes, which are especially available for Strongyloides (Lok, this issue; Ward, Reference Ward2015), will provide important tools for exploring the function and importance of these proteins in parasitism.

Comparison of the genetically identical parasitic and free-living stages of Strongyloides offers a powerful tool to study nematode parasitism. However, when comparing these two life cycle stages it is also important to consider the other phenotypic differences that exist between parasitic and free-living Strongyloides adult nematodes, which will also be determined by differential gene expression. In addition to their considerable differences in lifestyle, i.e. parasitic vs. free-living, they also differ in their longevity, morphology and method of reproduction. Parasitic adults live for around a month in the gut of their host and this is extended up to a year in immunocompromised hosts. By comparison free-living adults are short-lived and survive for around 5–6 days as adults. Parasitic adults are approximately 2 mm long, twice the size of free-living females which also differ in their oesophagus and gut morphology (Gardner et al. Reference Gardner, Gems and Viney2004, Reference Gardner, Gems and Viney2006). Unlike parasitic females which reproduce asexually by mitotic parthenogenesis, free-living females reproduce sexually (Viney, Reference Viney1994). The protein and gene families that are differentially expressed between parasitic and free-living females may therefore also represent differences in longevity, morphology and reproductive strategy.

Here, we have compared the acetylcholinesterase protein families across 14 nematode species including four Strongyloides species, and in a previous study (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016) we compared the astacin and SCP/TAPS protein families across the same 14 species. These comparisons have revealed that the Strongyloides and Parastrongyloides nematodes have undergone a massive expansion of genes encoding protein families with a putative role in parasitism, compared to most other parasitic nematode species spanning four nematode clades. The exception is N. americanus which also has a greater number of both astacins and SCP/TAPS genes, though phylogenetic analysis indicates that these possible gene family expansions are independent to the expansions observed in Strongyloides and Parastrongyloides (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). Future studies including greater numbers of parasitic and free-living nematode species are needed to identify if a similar phenomenon of major expansions of gene families with a putative role in parasitism has occurred in parasitic nematode species more widely. Within Strongyloides the high level of sequence similarity of genes within a given expanded gene family indicates that these genes have probably arisen through tandem duplication (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016). Many of these genes are also physically clustered in the genome, often located in a region at the end of chromosome II suggesting this particular region has been subject to multiple tandem duplication events, where genes from different gene families with a putative role in parasitism have duplicated. The clustering of these genes could imply that they are under selective pressures to maintain close proximity. For example, genes in the same region of a chromosome may share regulatory elements or allow accessibility to certain transcription factors (Lercher et al. Reference Lercher, Blumenthal and Hurst2003).

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

This work was supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust (094462/Z/10/Z to M.V.). IJT was supported by Academia Sinica.