Introduction

The Hebrew Bible prohibits lending at interest. This is often linked to care for the poor: “If you lend money to my people, to the poor among you… you shall not exact interest from them” (Exod 22:24). Lev 25:35–37, Ezek 18:17, and Prov 28:8 also couple usury and poverty.Footnote 1 Ben Sira (29), who views lending as a source of unnecessary worry and a good way to lose money, singles out lending to the poor as a positive activity that enjoys both the approval and guarantee of God. Philo associates avoidance of interest, forgiving of debts on the sabbatical year, and gifts to the poor with the civic ideal of philanthrōpia.Footnote 2 A similar connection is found in 4 Macc 2:7–9.Footnote 3

In Deut 23:20–21, however, usury is disconnected from the poverty laws. The former appears in chapter 23, while the latter appear in chapter 15, with the slave laws and the laws of the sabbatical year. Both Tannaim and Amoraim follow Deuteronomy in sharply decoupling usury from poverty. The Mishnah’s discussion of usury at Bava Metzi‘a 5 does not mention poverty; the parallel Tosefta (t. B. Metz. 4–6) does not either. The status accorded to the poor in scripture is explicitly erased in the midrash on Exodus from the school of R. Akiva, the Mekhilta of Rabbi Simon. This work expands the usury prohibition from “the poor” to all people.Footnote 4 In classical rabbinic literature, the usury prohibition functions in the realm of laws related to commerce and protection of private property, not those intended to ameliorate the plight of the poor. Loans and favors between (Jewish) neighbors and peers are regulated as commercial transactions. A person who borrows on interest transgresses no less than the lender.Footnote 5

As an economic problem, poverty can be ameliorated by giving money to the poor. Legislation about poverty may give benefits or penalties to people who are defined as poor. But poverty is also a matter of social imaginaries. The community can be imagined as one of equals, in which financial means do not determine civic status. It can also be imagined as bifurcated between classes, a system in which class forms a central part of an individual’s identity. Finally, the community can imagine that it is a community of “the rich” with or without an obligation to another community of “the poor.” If one imagines those of lesser means to be in one’s community, they are no longer “the poor” but rather peers down on their luck.Footnote 6 The radical inclusion of less fortunate peers in the rabbinic usury legislation brings the identity of their group to the point of conceptual and discursive erasure.Footnote 7

I leave the value judgment of this shift to others better equipped to discuss such questions.Footnote 8 In this paper I discuss the revival and return of the tradition that connected the usury prohibition to the poor in piyyut and in the Tanhuma midrashim. Both genres bring this tradition to the fore through the use of earlier rabbinic materials, which do not espouse it. This combination of usury and care for the poor mirrors fourth-century Christian writings on usury.

The paper will proceed thus. First, I discuss the precise nature of the coupling between usury and poverty in the Tanhuma midrashim, which transcends local textual issues, and note the ways in which these works employ earlier rabbinic sources in the service of this coupling. I then turn to piyyut, specifically two works by the fifth–sixth century payyetan Yannai, which feature this coupling as well. In the third part of the article I situate these works in the context of the late Roman “rise of the Poor.”Footnote 9

Tanhuma

Marc Bregman writes, “Tanḥuma-Yelammedenu literature is best regarded as a particular midrashic genre which began to crystallize toward the end of the Byzantine period in Palestine (5–7th century C.E.), but continued to evolve and spread throughout the Diaspora well into the middle ages, sometimes developing different recensions of a common text.”Footnote 10 All editions (and fragments) of the Tanhuma center their discussion of usury on the poor and their plight, and they associate the avoidance of usury with the salvation reserved for those who care for the poor.Footnote 11 In tone, they have much in common with the sermons of Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa and Ambrose of Milan on usury, pointing out the social evils of lending at interest and casting the borrower as a victim of the lender.Footnote 12

All published editions of the Tanhuma, as well as some of those still only in manuscript, use materials from Tannaitic literature and Leviticus Rabbah 34 to construct their homilies on Exodus 22:24.Footnote 13 Some editions of the Tanhuma include more material from their sources; others use them sparingly.Footnote 14

Tanhuma couples the usury prohibition and care for the poor in three ways: first, by the reworking of older rabbinic materials; second, the amplification of traditions found in non-rabbinic literature and their adaptation to fit the new coupling; and third, the introduction of new materials on the salvific import of the avoidance of usury and care for the poor.

Coupling Usury and Poverty: Redaction

Tanhuma homilists and redactors often used earlier rabbinic sources. In the case of usury, they turn both to Tannaitic literature and Leviticus Rabbah 34. The Tanhuma reworks these sources in service of its new ideology in various ways, as the following two examples indicate.Footnote 15

Example 1: Tan. Exod Mishpatim 9 (and parallels) = t. B. Metz. 6:13

The Tanhuma here reworks the Tosefta in three ways. First, the tradition is made anonymous. Second, the verse not only commends the avoidance of usury, but also giving charity to the poor. Third, avoidance of usury and engagement in charity is not only a way out of death but also tantamount to observing all the commandments. The insertion of charity and poverty into the Tannaitic tradition here brings it into conversation with the homilyFootnote 16 that follows it, which I discuss below.

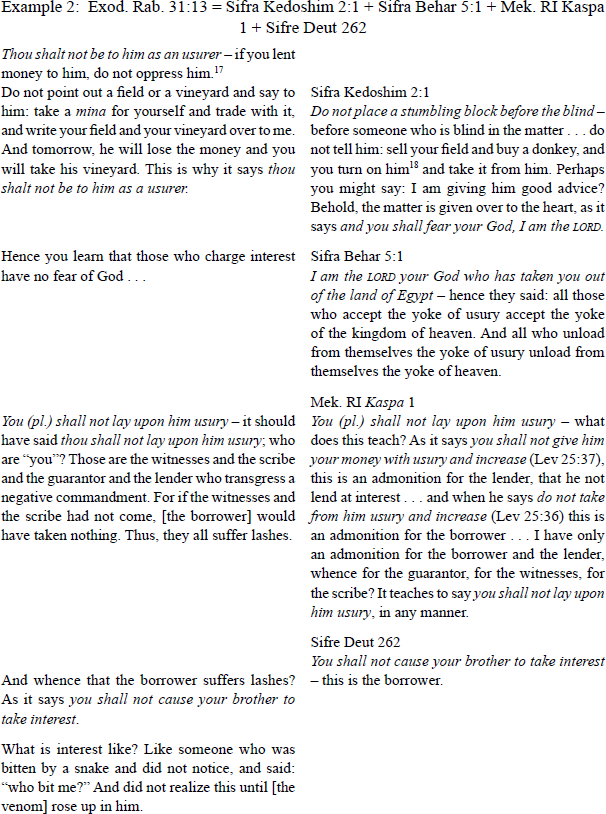

Example 2: Exod. Rab. 31:13 = Sifra Kedoshim 2:1 + Sifra Behar 5:1 + Mek. RI Kaspa 1 + Sifre Deut 262

Exodus Rabbah here weaves together traditions from various Tannaitic midrashim, and frames them between two non-Tannaitic traditions which reflect the usury-poverty coupling prevalent in the Tanhuma.Footnote 19 The explanation of the Biblical Hebrew term נשך as related to biting, and specifically snake bites, is conspicuously absent from classical rabbinic literature. Additionally, the prohibition against “oppressing” the borrower, though found in LXX and in the Targumim, is also absent from classical rabbinic literature. Re-working Tannaitic materials into this framework casts them as measures intended to better the lot of the borrower, the victim of usury.

Sifra Kedoshim is taken out of context to fit its new location. In its original context, it is a comment on Leviticus 19:14, “you shall not place a stumbling block before the blind.” In that context, Jews are admonished not to give bad advice to their unwitting peers to sell their fields with the intention of buying those fields at fire-sale prices later. Exodus Rabbah, perhaps reading into the Mishnah’s connection of this prohibition with usury (m. B. Metz. 5:11), takes Sifra’s admonishment from the context of bad advice to the more common context of borrowing against real estate. This practice was extremely common in the ancient Levant.Footnote 20 But it does not follow that bad advice causes a practice to become usurious. In fact, this same practice is mentioned and allowed in Mishnah Bava Metzi’a itself: “[If] a man lent another money on the security of his field and said to him, ‘If you do not pay me by this date three years hence it is mine,’ it is his. And thus Boethus b. Zonin did, according to the sages.”Footnote 21 The Mishnah allows (encourages?) using fields as security for the express purpose of repossessing them after a period of time elapses. This is not a usurious transaction, because, in the rabbinic imagination, neither the value of the loan nor of the collateral increases with time. Thus, if the lender does not benefit from the produce of the field, it is completely permitted. Nonetheless, it is easy to see how a borrower might be victimized through just these kinds of contracts and lose all of their property. The very behavior criticized by the Tanhuma is explicitly allowed in the Mishnah.Footnote 22

Not all of the Tannaitic material here is similarly reworked and some of it remains at odds with the outlook presented in the Tanhuma. Thus, Tanhuma echoes Sifre Deuteronomy’s censure of the borrower, whom the Tanhuma then likens to the victim of a snakebite.

The Tannaitic material is reworked and re-contextualized in the Tanhuma to include poverty and charity in the scope of the usury prohibition. Material from Leviticus Rabbah, which focuses exclusively on poverty and charity, stays mainly intact in the Tanhuma. It becomes related to borrowing, lending and the usury prohibition through context alone. By being cast as a commentary on the verses prohibiting usury in Exodus, and interspersed with discussions of usury, the poverty/charity homilies of Leviticus Rabbah now become a mirror image of the usury prohibition. Much like the insertion of charity into the Toseftan tradition above, materials from Leviticus Rabbah are used in the various editions of the Tanhuma to cast charity as the alternative to usury.

Material Unique to the Tanhuma Editions

Some material, found in several editions of the Tanhuma, is not found elsewhere and cannot reasonably be explained as a reworking of other rabbinic sources known to us. The two examples that follow include two kinds of unique material: (1) material with significant parallels in non-rabbinic works, such as Josephus and the Targumim and (2) material with no earlier Jewish parallels, but with some echoes in Christian literature.

Obadiah and Borrowing versus Lending

Exodus Rabbah, MS Vat. Ebr. 44 and MS Cambridge 1212, as well as the early Medieval Sefer ve-hizhir, contain the following homily:Footnote 23

Another matter: if you lend money to my people. This is what is written, He that putteth not out his money to usury. Come and see: anyone who has wealth and gives charity to the poor and does not lend at interest, it is recorded about him as if he observed all the commandments. And who is this? This is Obadiah, who was rich, and was the steward (אפוטרופוס) of Ahab the king of Israel, as it says And Ahab called Obadiah, which was the governor of his house (1 Kings 18:3). And he was exceedingly rich, but he spent all of his money on charity, because he fed the prophets (see 1 Kings 18:4). And when the famine came, he borrowed money from Jehoram, son of Ahab, [in order to] supply the prophets. [Obadiah] upheld he that putteth not out his money to usury [… he that does these things shall never be moved]. But Jehoram, who lent at interest, [about him] God said: is this one still alive? Let Jehu come and kill him, as it says And Jehu drew a bow with his full strength, and smote Jehoram between his arms, and the arrow went out at his heart. . . (2 Kings 9:24). And why between his arms and the arrow went out of his heart? For he hardened his heart and put his hands out and took interest. [And he died,] To uphold what Ezekiel said: He hath given forth upon usury, and hath taken increase: shall he then live? he shall not live (Ezek 18:13). Thus [God] admonishes themFootnote 24 and says if you lend money to my people.

The tradition about Obadiah borrowing money to feed the prophets whom he hid in a cave is found already in Josephus.Footnote 25 Josephus also provides a scriptural cue for this tradition, entirely missing from the Tanhuma. In 2 Kings 4:1: “Now the wife of a member of the company of prophets cried to Elisha, ‘Your servant my husband is dead; and you know that your servant feared the LORD, but a creditor has come to take my two children as slaves’ ” (NRSV). The husband of this woman clearly borrowed money, because the creditor is coming to take his sons. But who was this man? The only identification we have is that he “feared the Lord.” This is the same description of Obadiah, the steward of Ahab, found in 1 Kings 18:3 and 18:12.Footnote 26 Josephus, in retelling the story, says that the woman was the wife of Obadiah, and that she told Elisha that “a hundred [prophets] had been fed by him with money he had borrowed and had been kept in hiding; now, after her husband’s death, both she and her children were being taken away into slavery by her creditors.” The narrative thus begins with Obadiah providing for the prophets, and ends with a prophet providing for Obadiah’s sons.Footnote 27 A short allusion to this tradition is also found in Pesikta de-Rav Kahana Shekalim 5, attributed to R. Mani; but it does not go beyond identifying the woman asking Elisha for assistance as Obadiah’s wife.

Another source that reflects part of this tradition is the Targum to 2 Kings 4:1. In the targumic tradition, liturgical readings were sometimes prefaced by a lengthy narrative exposition called a Tosefta. These were sporadically preserved in fragmentary MSS and in biblical commentary, notably David Kimhi’s commentary to the prophets.Footnote 28 The Targum to 2 Kings contains the following expansion (in bold).

And one woman of the wives of the sons of the prophets called out to Elisha, saying: “your servant, Obadiah, my husband, is dead. And you know that your servant was fearful before the Lord. For when Jezebel killed the prophets of the Lord, he took one hundred men from them and hid them in groups of fifty men in a cave. And he would borrow and feed them, so that he would not feed them from Ahab’s property, for it was taken under compulsion. And now, the creditor is coming to take my two sons for him as slaves.”Footnote 29

A standard Aramaic loan contract would have included interest.Footnote 30 But the expansion does not make the connection between the avoidance of interest and Obadiah’s god-fearing. Instead, it alludes to Prov 19:17, “Whoever gives freely (חונן) to the poor lends to the LORD, and will be repaid in full” (NRSV). Obadiah borrows from Jehoram to lend to God, and thus his payment is assured.Footnote 31

“Fearing the Lord” is also part of the admonishment against taking usury in Lev 25:36. Obadiah left substantial debt after his death but was “fearful of the Lord.” This leads the Tanhuman homilist to the conclusion that Obadiah both borrowed at interest and that he avoided taking interest. This conclusion is not necessarily warranted by logic: Obadiah could have simply borrowed large sums of money and not returned them (yet); but the homilist adopts it all the same, and casts Obadiah as a willing victim of the evil lender, Jehoram. The former is righteous, and the latter is evil, and both receive their just deserts.Footnote 32 The tradition about Jehoram being the lender is not found in any other source.Footnote 33

The Mishnah censures both sides of a usurious loan contract (as well as the scribe, the witnesses and the guarantors). Borrowing at interest is equally problematic and equally forbidden, in the eyes of the Mishnah, as lending at interest.Footnote 34 But in the world the Tanhuma portrays, borrowers are victimized by their lenders. Commending Obadiah for only borrowing but not lending at interest fits nicely with this image. It also quite accurately reflects most of the usury prohibitions found in the Hebrew Bible.Footnote 35 Censuring those who lend at interest more than those who borrow is a salient feature of early Christian preaching against usury, for example in Ambrose:

We accuse the debtor because he has acted somewhat imprudently, but nevertheless there is nothing wickeder than the usurers, who think that another’s loss is their gain, and regard as their own loss whatever is possessed by others… The [lender] like a lion is seeking whom he may devour, the [borrower] like the young ox dreads the onslaught of the robber… The Lord therefore sees both the usurer and the debtor, he looks upon them as they meet, a witness of the wickedness of the one, the wrong of the other; He condemns the avarice of the former, the folly of the latter.Footnote 36

The Salvific Meaning of Usury

Exodus Rabbah, Tanhuma (ed. Mantua) and MS Vat. Ebr. 44 contain a homily that discusses the salvific meaning of usury and loans.Footnote 37 The homily centers on the term כסף נמאס, “reprobate silver” in Jeremiah 6:30, and connects it with other occurrences of “silver” and the verb מ-א-ס, “to abhor” in the prophets. Taking its cue from verses in Jeremiah, which compare Israel to various scrap metals, the homily reads the commandment to lend without interest in conjunction with the commandment to return a pledge “by the coming of the sun” (Exod 22:25–26), as a description of the way in which Israel have fallen into exile and how they will be, in the end-times, taken out of it:Footnote 38

Another matter: If you lend money to my people. This is what is written: Reprobate (נמאס) silver shall men call them [because the LORD hath rejected them] (Jer 6:30). When Israel were exiled from Jerusalem, the enemies took them out in collars. And the nations of the world said: The Holy (blessed be He) does not want these people, as it says Reprobate silver shall men call them, etc. Just as silver is smelted and made a vessel, and smelted again and made a vessel, and so many times over, until finally a man can crush them with his hand and it can no longer be used for work. So too Israel have no redemption, because the Holy (blessed be He) has rejected them, as it says Reprobate silver, etc. When Jeremiah heard this he came to the Holy (blessed be He) [and said]: Master of the Universe, is it true that you have rejected (מאסת) your sons? This is what is written Hast thou utterly rejected Judah… why hast thou smitten us, and there is no healing for us? (Jer 14:19).

…

The Holy (blessed be He) said to him: however, I have made a condition with them that if they sin, the temple will be pawned (מתמשכן), as it says, And I will set משכני among you (Lev 26:11). Do not read משכני, my tabernacle, but rather משכוני, my pledge. And thus Balaam says: How goodly are thy tents, O Jacob, thy dwellings (משכנתיך), O Israel! (Num 24:5). Two pledges. [And] They are called tents when built, and dwellings when they are destroyed.

I do not pawn my temple to the nations because I owe them anything. But your sins cause me to pawn my temple to them. Otherwise, to whom do I owe anything? As it says: Thus saith the LORD, Where is the bill of your mother’s divorcement, whom I have put away? or which of my creditors is it to whom I have sold you? To whom do I owe anything? Behold, for your iniquities have ye sold yourselves, and for your transgressions is your mother put away (Isa 50:1).

And this was my condition with Moses about them: If thou lend money to my people the poor by thee, thou shalt not be to him as an usurer. If they transgressed these commandments, I will pawn two pledges, as it says: If thou pawn to pledge (חבל תחבל) thy neighbour’s raiment. Moses said to him: Master of the Universe, will they be pawned forever? He said no, rather by that the sun cometh (Exod 22:25–26). Until the sun comes, as it says But unto you that fear my name shall the Sun of righteousness arise with healing in his wings (Mal 3:20).Footnote 39

Although it is an allegorical reading of silver, loans, pawns and the sun, the allegory and allegorized entities do not match up completely. Israel are called “reprobate silver” by the gentiles, as if God has cast them away. The homilist takes pains to prove that this is untrue. Sin however creates a debt and when Israel sinned, their temple was pledged as collateral for their debts. Apparently, God does not charge interest for the sins, but He withholds the pledge “by that the sun cometh,” i.e. until the day the messiah comes. The final day of salvation, on which the “sun of charity” will shine, is the day when Israel’s pledge will be returned to them and perhaps their debt will be forgiven.

The identification of the Messiah with the “sun of charity” in Malachi 3:20 is found already in the Testament of Judah,Footnote 40 and then in the Gospel of Luke (1:78).Footnote 41 It is subsequently invoked by (in chronological order) Clement, Origen, Hippolytus, Gregory Nazianzus and Eusebius.Footnote 42 It is not, however, found in rabbinic sources that predate the Tanhuma, which read the sun of Malachi 3:20 as the celestial body.Footnote 43

The combination of metaphors in this homily is especially rich: sin is debt; the temple’s destruction is its taking in pledge; the coming of the messiah is the sun, bringing with it the return of the pledge.Footnote 44 The classical rabbinic discussions of usury and debt contain no such allegories. The metaphor of debt as sin is ubiquitous in classical rabbinic literature, as in Second Temple literature. It is also used creatively in parables and in statements about sin.Footnote 45 But discussions of usury in rabbinic literature do not mention this metaphor outright or utilize it in any significant way.Footnote 46

Yannai on Usury and Poverty

Usury and poverty are also connected in the work of the payyetan Yannai, who wrote in late fifth- and early sixth-century Palestine. The relationship between the Tanhuma midrashim and piyyut has not yet received the comprehensive treatment it deserves. Scholarship on this relationship seeks textual connections between piyyut and midrashim conventionally dated later than the piyyut.Footnote 47 I point however to thematic and ideological similarities without claiming a philological influence or a genetic relationship.

The kerovah for the reading beginning with Exodus 22:24 has not been preserved in its entirety. Most of it is missing, and only two of the piyyutim survive. Importantly, no catenae of verses, which typically end the poems and signal the shift to the end of each blessing, have been preserved. Thus, there are no traditions traceable from piyyut to midrash, but only an ideological shift that they both share. The connection is in tone, tenor, and agenda, which are significantly more difficult to gauge.

The bulk of Yannai’s work, preserved in the Cairo Genizah, consists of piyyutim for the Sabbath and holiday prayers. Most were published in 1985–1987 by Zvi Meir Rabinowitz, but Rabinowitz’s edition contains no piyyutim for week 61 of the triennial lectionary cycle.Footnote 48 In 2002 Benjamin Löffler published a fragment with two piyyutim for this lection.Footnote 49 The following is the end of a “Five” piyyut, customarily a ten-line alphabetic acrostic ending with yod.Footnote 50

א Four dusts you have made most stringent from among the laws / and they beat before them and after them

…

ה For the dust of usury is the hardest of all / On the borrower and the lender, the debtor and the creditor

ו And it brings sin to the guarantor and the writer and the witnesses / And to the house in which it is placed, and the wealth in which it is mixed

ז It is meritorious to be a lender who does not take usury / for he lit the eye of the poor man in a time of darkness

ה If the son of a gentile or the son of your people come to you to borrow / the commandment of the close precedes that of the far

ט The good one, who feeds all is called the master of all / from his hand is all and his is all

י A hand, when you open it to the needy one, makes you equal to your creator / lend to him and he will repay you, and give you your just rewards.Footnote 51

“Five” piyyutim often center on the interplay between scripture and the legal issues in the lection.Footnote 52 Here one may have expected a poetic catalog of financial transactions, based on the Mishnah and Tosefta. Instead, the poet offers a mélange of usury and charity. The section poetically invokes two Tannaitic traditions: it begins, following Tosefta Avodah Zarah 1:10, with a listing of legal areas which impart “dust.” In the poem, “dust” is a curse or a dampening of profit surrounding a more severe prohibition.Footnote 53

The Tosefta lists four legal areas that impart “dust”: usury, seventh-year produce, evil speech and idolatry. It then explains what should be avoided due to these dusts: “Dust of usury” is a reason to avoid trading in bills of debt owned by another. Although the markup on that debt is not technically usury (t. B. Metz. 4:3), the Tosefta rules against it, saying it can impart “the dust of usury.” For Yannai “the dust of usury” is the fact that the sin of usury spreads to all those involved in contracting the loan, not just borrower and lender. Yannai thus combines the Mishnah (m. B. Metz. 5:11), which lists five transgressing parties for each usurious loan, with the tradition that usury imparts “dust,” and equates the two. This “dust” also brings a curse on the wealth itself, and the home it is placed in. The former tradition is found in the Talmud—but not the latter.Footnote 54

Yannai continues: “It is meritorious to be a lender who did not take usury/for he lit the eye of the poor man in a time of darkness.” The poor—entirely absent from the rabbinic usury laws—are brought into the conversation. The word זכות, which begins the line, is a financial term—it means “credit,” but also “merit.” In colloquial Palestinian Aramaic, beggars would say זכי בי or זכי גרמך בי, “cause merit to yourself through me” when asking for alms.Footnote 55 Yannai uses the term זכות in conjunction with an allusion to Proverbs 22:2 and 29:13, which are both about poor people meeting others with more means, to articulate the avoidance of usury. He thereby links usury and charity once again, as in Leviticus, Exodus, Psalms, and Ezekiel.

The second law in the piyyut is: “If the son of a gentile or the son of your people come to you to borrow/the ‘commandment’ of the close precedes that of the far.”

Yannai calls this lending a “commandment” מצוה, used (with its Greek cognate ἐντολή) in Second Temple literature to mean “charity.” This usage is rarely attested in the legal register of rabbinic literature, but there is ample evidence of it in colloquial speech and in epigraphy.Footnote 56 Thus, says Yannai, Jews should lend to Jews (“the close”) before they lend to gentiles (“the far”). This law is also Tannaitic in origin, found in Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael (Kaspa 1).Footnote 57 The Mekhilta picks up on the verbosity of Exodus 22:24, “if you lend money to my people, to the poor one among you.” Each of these qualifiers is read as denoting a precedence among two groups, and those not of “my people” or “among you” have a lower priority:

Israel and a gentile stand before you – [choose] my people

A poor man and a rich man stand before you – to the poor

*A poor man from your people and a poor man from your town – the poor from among you* Footnote 58

A poor man from among you from your town, and a poor man from among you from another town, it teaches saying – את the poor from among you.

The piyyut ends with an exhortation to “open hands” to those in need. This alludes to the commandment to give charity in Deuteronomy 15:8 and 15:11, and paraphrases Proverbs 19:17, “Whoever is kind to the poor lends to the LORD, and He will repay him.” The combination of the commandment to “open hands” to the poor in Deuteronomy 15 and the commandment to abstain from usury in Deuteronomy 24 is novel in comparison to rabbinic literature, and to Deuteronomy itself, the first pre-rabbinic tradition to uncouple poverty and usury.

The kerovah for week 99 in the cycle, beginning with Leviticus 25:35, also couples usury, poverty and charity, using the same biblical verses and key terms. The kerovah was preserved more fully—there are two parallel Cambridge fragments that cover the first six piyyutim of the kerovah.Footnote 59 The text preserved includes the catenae of verses, which combine verses on usury (Lev 25:36; Prov 28:8) with verses on charity (Prov 22:2) as well as other verses, read in rabbinic literature as discussing charity (e.g. Eccl 11:1).Footnote 60

The association between avoidance of usury, loans to the poor, and charity is especially apparent, again, in the Five, which here too combines themes of usury (from Tannaitic literature) and charity (from Amoraic midrash). The piyyut begins with a paraphrase of Psalm 41:2, “Happy is he who considers the poor; the LORD delivers him in the day of trouble.”

א Happy are those who uphold the commandment of stretching out the hand (ךי יטמ)

For it will be credited to him immediately (ךימ) and erect a monument to him (ךי ןל)

ב Its punishment is twenty four curses

And its reward twenty-four blessings

…

ה Lend to him, that he may live and he will be equal to you

Do not be a creditor to him, be a guarantor to him

ו And do not charge him five for a tetradrachm

And do not increase an addition of produce upon him

ז The admonishment of this merit, this commandment stated is heavy in the kingdom of the eternal king

ה Giving freely (or: lending)Footnote 61 to the lowly and oppressed and strengthening the staggering and destitute

The commandment of the poor and downtrodden, the merit of the wanting and oppressed

ט Good and bad, mercy and cruelty, life and death were given to man

י He will benefit if he was a benefactor, he will be pitied if he gave pity

He will be revived if he revived, merit if he gave “merit.”

The beginning and end of this piyyut contain traditions about charity known from elsewhere: charity brings twenty-four blessings and curses (Lev. Rab. 34:11);59the names for the poor (Lev. Rab. 34:6); charity brings merit to be used immediately as well as in the future (m. Pe’ah 1:1). At the center of the piyyut is a paraphrase of the mishnah which defines usury, Bava Metzi‘a 5:1: “And do not charge him five (denarii) for a tetradrachm (= four denarii)/And do not increase an addition of produce upon him.” In this paraphrase, Yannai brings the Mishnah ever closer to scripture, reaffirming the primacy of the scriptural context over the rabbinic law.

Lending to the poor, in the piyyut as in scripture—and not in the Mishnah—is part of the commandment to give charity: “Lend to him, that he may live, that he may be equal to you,” a paraphrase of Lev 25:36. Other piyyutim in the kerovah emphasize the giving aspect of charity: “you shall surely give to the destitute according to your hand, and He [=God] shall surely give to you according to His hand” (I:476 l. 30); “Do not let him be sore/do not oppress him if he borrows // support him and he will be with you/for he who gives to the poor lends to the Lord” (I:478 l. 51–52). Giving and lending are intermingled here as two aspects of charity, which is “The Commandment,” and “The Merit.”

Z. M. Rabinowitz noted that the end of the ה-stich, “be a guarantor to him,” parallels the Sifra (Behar 5:1): “do not take usury or increase from him—from him you do not take, but you can become a guarantor for him.”Footnote 62 The Sifra rules that it is permissible to become a guarantor for a forbidden usurious transaction. This ruling opposes the law in the Mishnah (m. B. Metz. 5:11) that the guarantor transgresses a negative commandment by participating in the loan. The Bavli (b. B. Metz. 71a), perhaps following the Tosefta (t. B. Metz. 5:20), rules that the Sifra discusses loans to gentiles, but this is not apparent from the Sifra itself, which is commenting on the superfluous מאתו in the verse. It seems dissonant with the tone of the piyyut that it should allow Jews to facilitate usurious loans for other Jews. Yannai might be using “guarantor” in a figurative sense, i.e. “do not become his creditor, but show solidarity with him and support him.”Footnote 63 However, a closer look at the new context of the usury laws explains how this makes sense: as we saw above, with regard to Obadiah, usurious borrowing is not as blameworthy as usurious lending. Being a guarantor for a poor person who is not able to obtain an interest-free loan, even from a Jew, is a meritorious act for Yannai, who relies on the Sifra to allow it. In the process, he transforms what is a relatively local and minor question—does someone who co-signs a usurious loan transgress a negative commandment—into a matter of moral and religious duty towards the poor.

In halakhic works, the usury prohibition and poverty remain disconnected throughout this period. In the Babylonian Talmud usury is connected to robbery and fraud, but not opposed to charity (b. B. Metz. 61a). The first halakhic work I have found that connects the two is a fragmentary short Arabic work on usury by Sa’adia Gaon, perhaps a lost fragment from a commentary on Exodus or Leviticus, published and translated most recently by Robert Brody.Footnote 64 Sa’adia succinctly and systematically lists the various kinds of usury according to a categorization scheme of his own invention, using phraseology adapted from the Mishnah. Then he turns to ask: “What is the aspect of wisdom (wjt alḥkmh) for which He was so harsh (šdd) regarding usury?” (346 l. 42). Sa’adia provides several answers, some of which are known from Talmudic literature. The first, however, is not. Sa’adia says that most of those who borrow at interest are weak (ḍʿfy), and lending at interest will just cause them to become poorer.

This line of reasoning continues in Ibn Ezra,Footnote 65 and it may have also been reflected at some point in the medieval debate on the permissibility of lending at interest to Jewish apostates.Footnote 66 But in the geonic period, as far as I can tell, this is a novelty. Sa’adia here introduces, in what seems to be a halakhic survey, an innovation found only in aggadic works from a Palestinian milieu—perhaps a reflection of his own education in Palestine before coming to Babylonia.Footnote 67 Sa’adia’s incorporation of this idea into his own text is careful and measured, however. He marks the section as the “aspect of wisdom” of the usury laws. Although poverty relief is the first justification he provides, it is not the only one. Sa’adia also notes that usury was permitted “under the old regime,” so the Torah had to reinforce it with fear of God. He points to the fact that usury accumulates with time, and every cumulative sin is more severe.Footnote 68 He does not rank these reasons in any hierarchy. The very mention of the poor in this context may reflect the sensibility, already current in the Palestinian (which we might by now call Shāmi?) orbit that usury laws were, primarily, for the poor, and that it was their plight that they were meant to rectify.Footnote 69

The Broader Picture

For the Tanhuma midrashim and piyyut, the civic framework set out in the Mishnah and elaborated in the Talmuds was no longer satisfactory. They understood the usury laws as a means toward alleviation of poverty, and that is how they spoke about them. They also reworked the materials at their disposal similarly. They reframed and recontextualized Mishnah, Tosefta, and earlier midrash, while fusing them with new material, to make the focus on poverty seem as if it is evident from these earlier materials as well. Reading through these works, it is possible not to notice that anything at all has changed. But in fact, the political world envisioned by the Mishnah is no longer sustained, even discursively.

The process of rereading the rabbinic texts back into the world of scripture, with its rich and poor, and the protected classes of stranger, widow and orphan, is a central factor in the creation of this trend. When the worldview embedded in the rabbinic texts ceased to be a living reality, scholars, preachers, and poets turned to the primary canon for justification. “Re-scripturizing” can be found at Qumran and is embedded in the very beginnings of halakhic midrash.Footnote 70 It is an ongoing process which can always be initiated, because scripture is always there.

However, the world of scripture had been taken up, some centuries ago, by another community which placed a premium on poverty and care for the poor. The earliest Christian texts emphasize, following the Hebrew scriptures, that the poor are a gateway to God. Building off this connection, they also raise up the figure of Christ as a paradigm of poverty. In time, the church would come to present its institutions and officials as a community of holy poor, who are the most deserving of charity, and also those who are authorized to distribute it.

It is difficult, under these conditions, not to imagine that such a significant shift in Jewish discourse on poverty would not have been in dialogue of some sort with what was, by that point, the mainstream opinion of the majority religion. This “common sense” drew on so many Jewish sources, as well as on sensibilities still extant in actual Jewish practice and speech patterns, that adopting significant parts of it into an elite Jewish discourse was all but inevitable.Footnote 71

Scholars tell a story of the “Rise of the Poor” in late antiquity from a myriad of perspectives. Some discuss the shift in the legal vocabulary of the empire in the fourth century, when references to “poverty and ‘the poor’ per se occur with relative frequency.”Footnote 72 Some discuss it from perspective of the classical city and its virtues of philanthrōpia and megalopsychia as opposed to the “new” virtue of philoptōchia, into which the older virtues are subsumed.Footnote 73 It is possible to describe a decisive discursive shift here because (1) we see the polemic against the older ethos in action and (2) the new discourse left its mark on the physical landscape of the city. Funds shifted from games and civic benefaction to the church and its charities.Footnote 74 Through the mediation of the church, urban grandees from around the empire began spending their money “Jewishly.”Footnote 75

Scholars of Jewish texts however assumed that Jewish charitable giving went relatively unchanged. Ephraim E. Urbach, for example, discussed “the rise of the poor” only in the context of rabbinic polemics against charitable giving by non-Jews in the early church.Footnote 76 But the “Jewish” ideas that moved the imperial elite were not received by the rabbis unfiltered or unaltered. In the earliest strata of rabbinic literature sacramental giving is not found. The poor do not occupy a place of privilege in Tannaitic literature, which presents a picture of a society nothing like the one bifurcated by rich and poor portrayed in the gospels and replicated in early Christian preaching. The poverty line is drawn quite high (200 denarii, the same amount as a woman’s dowry), and “the poor” as a class are written almost out of existence.Footnote 77 The Mishnah has, for example, no laws on how or when to give charity to beggars.Footnote 78

The Mishnah represents a civic ethos, with a focus on the town as the locus of a man’s temporal and spiritual activity, and the (Jewish) people of the town as the primary beneficiaries of charitable gifts.Footnote 79 This includes the civic institutions that the Mishnah envisions as meant to care for those citizens of lesser means: the food dole and the community chest, discussed at length by Gregg Gardner.Footnote 80 The Tannaim do not imagine that people of lesser means do not exist, or that others do not have obligations toward them. Rather, they imagine that the basic unit of Jewish community is “the city,” and it is the obligation of “citizens” to care for one another through institutional giving. The Jewish “city” is envisioned as one in which differences in means, which clearly do exist, do not create differences in political status. If this is correct, we must return to our sources and scan them for signs of “the rise of the poor,” as a concern independent of civic life, similar to what we know from Christian works.Footnote 81

In some areas, such as giving to beggars or the spiritual significance of charity, the poor rise in prominence in Amoraic rabbinic literature, both Talmud and Midrash.Footnote 82 But the recoupling of usury and poverty is a rather late phenomenon, which appears only in late rabbinic sources, or what we could term post-rabbinic sources, in the fifth or sixth century CE. In Christian treatments of wealth, too, speaking out against usury, and marking interest-free lending as a form of charitable giving, comes relatively late.Footnote 83 The rabbis returned to the poor in fits and starts, all in the context of the (discursive) demise of the civic ethos that was held dear by both the rabbis of the Mishnah and contemporary imperial elites. It did not happen in one moment.

How could we account for the shift towards recoupling of usury and poverty in the later rabbinic sources? We could chalk it up to genre: the legal nature of the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Talmuds conceivably gives little room to the plight of the poor. But this is contradicted by the complete absence of a link between usury and poverty in “classical” midrash, cotemporaneous with the Yerushalmi, and arguably earlier than the Bavli. The usury laws in the Mishnah view usury as a crime against the divine, with no apparent human victim. They forbid both borrowing and lending equally.Footnote 84 Similarly, we might argue that the audiences are different: the Mishnah’s polis could be cast as a vision for the learned élite, whereas the synagogue-goers who would hear piyyut and perhaps Tanhuma homilies prefer their world more bifurcated. Perhaps this “popular” worldview existed alongside the Mishnah and its highbrow politics all along, but is only expressed and refined in later works.

During this time the Palestinian Talmud had already been “canonized” to the point where it ceased to be expanded. What halakhic literature was produced in this period in Palestine is terse and concerned with practical matters, and quotes Talmudic dicta as authoritative.Footnote 85 Fealty to rabbinic law was still proclaimed, and we have no reason to doubt it. But the legal canon no longer demanded creative engagement in its formation, and creativity shifted elsewhere. This was a time for rethinking narrative: the laws are not contested, but their meaning is recast, using all the available works in the expanded canon, rabbinic literature as well as the scriptures.Footnote 86

Another avenue of inquiry is material. We could look for changes in Jewish settlement patterns in the fifth and sixth centuries CE, to attempt a survey of their material wealth and to examine the institutions which may have survived, in order to see if they changed in any way from the classical rabbinic period.Footnote 87 For the sixth century, we might also consider the impact of the period known now as the “late antique ice age,” as well as the Justinianic plague, which in 541 made its first foray into the Roman empire at Pelusium.Footnote 88 Both may have had effects on population sizes and social structures, including the polis, throughout the Mediterranean basin. They might have brought about an economic downturn in the Roman empire, and made it more vulnerable to the attack of the Muslim armies from the south. Justinian also made significant restrictions on lending and severely curtailed interest rates.Footnote 89 Perhaps, with the demise of physical structures comes the demise of the polity the Mishnah imagines.

Third, the discursive shift in late rabbinic works has roots in the Hebrew scriptures but was amplified and carried out first by Christian readers of those scriptures. If the communal focus shifted away from the civic fabric and became centered on the faith community, it is likely that the Jewish attempt to mirror the structures of power and offer discursive alternatives to them would change as well. A sacramental and salvific concern for the poor took hold in Second Temple Judaism and then, with the rise of Christianity, in growing swaths of the Roman empire. While this salvific language was pushed to the side by the early rabbis, it resurfaced as the central idiom in post-rabbinic literature.

These options are not mutually exclusive; rather they could be read as mutually reinforcing. A change in material circumstances could lead to a reappropriation of latent or foreign ideas. Conversely, similar material circumstances could be cast differently in different times with alternating ideological scaffolding.

I have found little evidence of literary borrowing between Christian homilies and the piyyutim or Tanhuma midrashim on usury. That the same verses are quoted often points to little more than a shared scripture, because they are employed in different ways. The fact that the same “common sense” is reflected in these works, differentiated by time, place, genre, language, and content, shows that they are the product of a shared discourse. Because it was read into scripture seamlessly, it was almost transparently adopted and became virtually self-evident. In this post-rabbinic environment, lending to the poor interest-free regained its status as part of the personal obligation to give charity, which it had lost in the regnant voice of classical rabbinic literature. Usury was now again envisioned as a means of oppressing the poor rather than a repudiation of civic status in the Jewish polity.