Therefore from God’s reason and through His thought on the generation of time, so as to allow time to come into being, the Sun and the Moon and five other stars, which are referred to as “planets” came into existence so that the numbers of time could be determined and protected. (Plato, Timaeus)Footnote 1

Why Wednesday?

Why is Wednesday a holy day for Yezidis? The easiest way to provide an answer to this question is to point to Judaism, Christianity and Islam. The adherents of these religions celebrate Saturday, Sunday and Friday respectively; Yezidis similarly have followed the tradition of having their own “holy day” and, wanting to be different, they have chosen one that was not associated with other religions. On the other hand, such an explanation might well justify a choice of Tuesday or Thursday to be the holy day. Such reasoning fails to account for the special status that Wednesday enjoys among Yezidis. The place that Wednesday holds in Yezidism can be rationally explained, similarly to the meaning of other days in the week within other religious systems. Although I do not know if the explanation that I suggest below stood behind the Yezidis’ choice, it seems highly likely to me that it did. However, before I present it here, let me provide a brief outline of the Yezidis and especially of “Yezidism,” as it is within its framework—understood as a kind of system of rules or set of concepts—that Wednesday occupies a particular place.

Figure 1. Yezidi Qewwals in Lalish.

Source: the author.

The Yezidis and Their Tradition

The Yezidis consider themselves the oldest people in the world, offspring of Adam’s son, Sheihid ben Jarr, who was born without participation of Eve, before she gave rise to the seventy-two nations of the world. In their eyes they belong to the oldest religious tradition and therefore, apart from the term “the Yezidis,” they refer to themselves in terms of Sunet, “Tradition.”Footnote 2 For centuries they have inhabited the territories of North Mesopotamia, where the cultural influences of East and West, Christianity and Islam, Hellenism and oriental cultures crossed. Each of those cultures jealously guarded its identity, but at the same time each was marked by the influence of those with whom it came into contact.

The main abodes of the Yezidis are situated in the Nineveh and Dohuk governorates in northern Iraq, especially in two areas: Sheikhan (House of Sheikhs) and Sinjar (ancient Singara, Kurd. Shingal), where they inhabited more than 100 villages.Footnote 3 As a result of genocide committed by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), Sinjar is now depopulated and many of the Yezidi who survived were forced to emigrate. This is not for the first time: for centuries, the Yezidis were accused of Satanism and persecuted as not belonging to the Ahl-e Kitab people. Ottoman Turks tried to convert them to Islam by force, and in case of refusal punished them with death. Therefore, over the centuries the Yezidis spread to the Christian Transcaucasian territories, to Armenia and Georgia, and, in recent years, especially to Russia and Germany.

The main religious sanctuaries and tombs of the Yezidi saints are located in vicinity of Sheikhan region, in Lalish valley, in the foothills of the Hakkari mountains. According to myth, Lalish was created in heaven and descended as the first and the most beautiful place on earth. One of the Yezidi sacred hymns even states that “Lalish is a powerful Paradise [behişt], And a house from eternity, And the home of Sultan Sheikh Adi.”Footnote 4 For this reason the whole valley is considered holy, and shoes must be removed before entering it.

Behind the veil of the myth, after examining reports of the medieval historiographers,Footnote 5 we can state that the Yezidis have at least 800 years of documented history. A particularly significant event for their community had took place in the twelfth century, when a Muslim mystic Adi ibn Musafir (called Sheikh Adi, Shiadi or Adi al-Shami, i.e. Adi the Syrian) came to the Lalish valley and founded a mystical brotherhood, Adawiyya. After his earthly days came to an end in the 1160s, his body was buried in a sarcophagus, and placed in the building which now serves as the main Yezidi sanctuary. On the wall of its old entrance portal one can see a huge copper serpent of unknown origin. Most likely the building was formerly a Christian monastery or a dervish teqqe built over the spring which emerges in the underground cave.Footnote 6

In Adi’s time the Yezidi community consisted of his followers from the Kurdish and Assyrians tribes living in the region as well as the Arabs, descendants of the Umayyad dynasty who sought shelter in the area. This group also included Sheikh Adi’s relatives whose family descended from the line of the last Umayyad ruler, half-Kurdish Marwan II (a grandson of Marwan b. al-Hakam). Therefore the Yezidi religion arose as a movement formed on the basis of the local pre-Islamic beliefs permeated by mystical ideas of Adi and his successors, especially his great-great-nephew Sheikh Hasan and Hasan’s son Sharfadin, who have been venerated especially in Sinjar, where he lived.

Religious and ethnic diversity seems to remain in conjunction with the division of the Yezidi community into castes, introduced in the early stages of its existence. The whole Yezidi milet consists of three endogamous castes named according to Sufi-originated terminology: Sheikhs (Ar. elders, spiritual leaders), Pirs (Pers., same meaning) and Murids (Ar. disciples). Although the Murids constitute more than 90 percent of the whole community, the sheikh caste is the most significant. It is from the sheikhs that Bave şêx (Father of the Sheikhs) and Mîr (Prince), the religious and political leaders, are elected.

Besides the division resulting from blood ties, the Yezidi community is also divided according to function. Among them, one should mention especially the Faqirs, a kind of Yezidi “monks,” and the Yezidi hymnists—Qewwals. The duty of Qewwals is to convey the religious lore contained in the sacred hymns (qewls), which they do with the accompaniment of two sacred instruments: daff (tambourine) and shebâb (flute). Their tasks include visiting Yezidi villages every year during the so-called “Parade of the Peacock” and participating in religious ceremonies, when they play music and recite hymns. This is one of the most important functions for the duration of the religious ties, because for centuries the Yezidis were faithful to the religious prohibition on writing down their religious principles. The ban was only broken in the twentieth century. Therefore, the basic source for the study of the religion tradition of the Yezidis is their oral tradition and their sacred hymns.

The Yezidi Religion: Sharfadin

In referring to the religion of Yezidis as “Yezidism,” we need to consider whether we are talking about the Yezidism as understood by non-Yezidis, or Yezidism in the understanding of Yezidis themselves. This is particularly important because a lot of Yezidis do not refer to their religion as “Yezidism,” but use the word “Sharfadin” instead, which is preserved in a common formula: “Dîne min Şerfedîn,” i.e. “My religion—Sharfadin.” They have given it a specific name, because one of the fundamental principles of the religion lies in the conviction that reality is made of personified emanations of God. As the spiritual head of the Georgian Yezidis, Dimitri Pirbari (Pir Dima), told me:

The Yezidi religion is characterized by personification. Days are personified, months are personified, Heaven and Earth—personified. Everything is personified except one—evil is not personified. … The Yezidis say: “Dîne min Şerfedîn e,” i.e. “My religion is Sharfadin”—this is the personification; “Atqata min Siltane Êzîde,” i.e. “My faith-belief is Sultan Yezid”; and thirdly—“Îmana min Tawûsî Malaka,” i.e. “I believe in Tawusi MalakFootnote 7.” … In my view, during the Sharfadin rule the ultimate canonization of the Yezidi religion took place. Thus the entire canonization was associated with his name. One can also say that Sharfadin was the real name of Sheikh Adi. And finally, it is often said that Sharfadin is one of the names of Tawusi Malak. I believe however that first and foremost the name is connected to the person who lived in Sinjar. I think that it is during his time that the canonization occurred. And therefore it is said that it is his religion, his way and his order. … The Yezidi religion is mysticism. It does not exist without it. In prayer, we call God, Xwedê. In our understanding, God is everywhere and in everything.Footnote 8

The term “Şerfedîn” carries a very wide range of meaning for Yezidis. First, it is the name of an angel. In one of the Yezidi hymns, Behind the Veil, it can be heard that: “Angel Sherfedin is the first principle and religion.”Footnote 9 Second, it also conveys an individual etymological sense—“Honor of the religion” (Ar. sharaf al-din). Third, it can refer to Sheikh Adi, whose full name was Sharaf al-Din abu al-Fadail Adi ibn Musafir ibn Ismail ibn Musa ibn Marwan ibn al-Hasan ibn Marwan.Footnote 10 Fourth, it is the name of a Yezidi leader from Sinjar, Sharaf al-Din b. Hasan (d. 1257/8), during whose time the principles of the Yezidi religion were most likely established. His position in Yezidism is exceptionally strong, particularly among Sinjari Yezidis, which can be well illustrated by their saying: “If we had two Sharfadin, we would not need God.” Finally, Sharfadin also constitutes the name of the Savior (Şerfedîn il-Mehdî), who in accordance with the Yezidi faith is to come at the end of time. Moreover, Yezidis use this name to refer to their sacred hymns, qewls, in general, which provide an elemental source of knowledge about their religion (in which over centuries the use of the written word was prohibited) and hold a special place in it, corresponding to the status of holy scriptures in other religions. Giving the hymns the name of “Sharfadin” denotes that the religion is encompassed in them and finds its expression through them.

Only two of the abovementioned meanings allow an approximate estimation of the time when the Yezidi religion and its principles were established. If we assume that the name of the religion—Şerfedîn—stems from Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir, the beginning of the religion and its principles have to be traced to twelfth century, whereas if we ascribe the origin of the name to Sharaf-al-Din of Sinjar, then they would date back to thirteenth century Nevertheless, in conversations with Yezidi it can be heard that the name “Sharfadin” comprises all the above-mentioned characters and meanings, as it is the name of one of the first angels, the Peacock Angel (Tawûsî Melek), who by will of God (Xwedê) was granted rule over this world. He permeates and encompasses the entire earthly reality, just as a peacock’s tail includes the whole spectrum of colors.

Because of the particular worship of the angels, Yezidism (and Yarsanism, along with Alevism) is sometimes classified as a branch of the religion for which the name “Yazdanism” was invented, i.e. “The cult of Angels.”Footnote 11 Some scholars in turn try to derive the name from the Persian īzad (divinity/god) or from the Avestan yazata (venerable) or connect it with personages with similar-sounding names, e.g. Yazid al-Ju’fi; Yezid b. Unaisa; Yazdin and even Jesus, son of Mary, or an Iranian town Yazd.Footnote 12 However, in conversations with non-Yazidis the Yezidis refer often to other etymologies; for example, they say that “Yezidi” (Êzdî) means that “God created me” (Xweda ez dam), so the “Yezidis” means “the people of Creator.” These explanations, however, seem to be mainly due to the fear of Shi’a Muslims, among whom caliph Yezid ibn Muawiya has a sinister fame. In fact, in the Yezidi oral tradition (in the legends and hymns that the Yezidis disseminate in their own group), the figure of Yezid ibn Mu’awiya, called “Sultan Yezi,” is mentioned and portrayed as a mystic in whom God or his supreme angel, the Peacock Angel, was embodied.Footnote 13

In this context, the Yezidi auto identification as the “Tradition” takes on a deeper meaning. By this name they wish to emphasize that both they and their religion constitute the oldest religious tradition, coming directly from the angels and Adam himself; Their religion thus, through angels, received the divine element (Sur, “Mystery”). Their place of cult was Ka’ba, before Mecca became the holy city of Muslims.Footnote 14 In other words, Yezidis believe they are the descendants of the Quraysh tribe and its forefathers. The most sacred Yezidi place, the Lalish valley, was laid out in the fashion of Mecca, and just as in Mecca, the Zem-zem spring, Mount Arafat or Pira Silat bridge are there. The most sacred objects of the Yezidi religious practice, the so-called Sanjaks or Peacocks,Footnote 15 are perceived to be the holy artifacts; according to Yezidi beliefs they were initially kept in Mecca, in the custody of the grandson of Abraham, from where they were moved to Syria by Yezid’s father, Mu’awiya.Footnote 16 This legend was described by the prince Ba-Yazid al-Amawi (son of Ismail Beg Chol):

These peacocks, were set up in the Holy Ka’abah side by side with the Quraish’s gods which were worshipped at that time. After Islam, Abu Sufyan saved the seven Sanjaqs for being holy for Quraishites and for a memorandum of his great grandfather Ibrahim Al-Khalil [ = Abraham]. Those Sanjaqs remained with him until his son Mua’wiya inherited them and transferred them from Holy Mecca to Al-Sham [Syria] when he was amir [ruler] over it in the caliphate of Omar ibn Al-Khattab.Footnote 17

In this context, we can perceive the special cult of two worldly embodiments of the Peacock Angel: Adi ibn Musafir, the descendant of the Umayyad dynasty (descended from Quraysh), and particularly the eponym of Yezidis, Umayyad caliph Yezid ibn Mu’awiya (Êzî, Siltan Êzîd), in whom they see the defender of the pre-Muslim, Meccan tradition. Yet for the full picture of this religion, one should add the special place of celestial bodies, which are also perceived by Yezidis as a manifestation of the world of angels.

The Moon, the Sun, the Seven

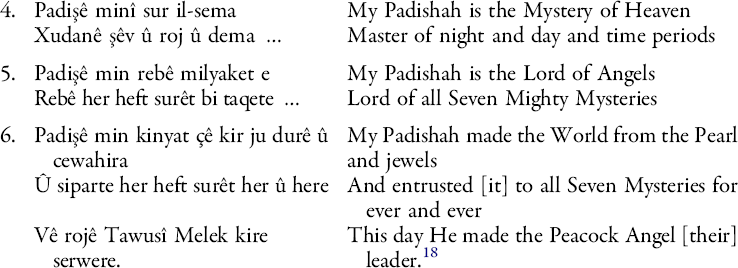

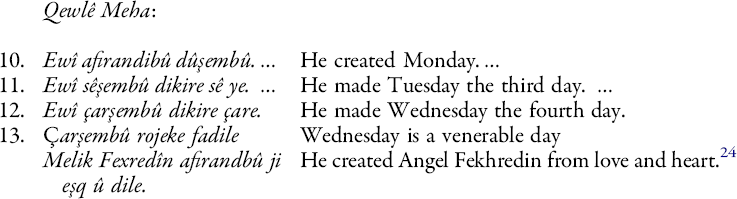

Apart from the characters already mentioned, Yezidis hold in particular reverence seven angels, called “the Seven Mysteries” (Heft Sur). As is recited in The Hymn of the Padishah (Qewlê Padişa):

The Seven Mysteries have their individual manifestations—they become personalized in the celestial bodies as well as in the characters of saintly men. A good illustration of such an emanational way of thinking can be found in the example of two brothers—Shemsedin and Fekhredin—regarded as the sons of an enigmatic figure called Êzdîna Mîr (or Êzdînamîr/Yezdîn Amîr). The former also goes under the name of Sheikh or Angel Shemsedin (Şêx/Melik Şemsedîn) and “Sheshems” (Şêşims), whereas the latter is known as Sheikh or Angel Fekhredin (Şêx/Melik Fexredîn) and Fekhr.

In the hymns devoted to Shems, Yezidis sing that “everything partakes in him,”Footnote 19 they also call him “the Light of God” (Şêşims nûra Xwedê ye).Footnote 20 They regard him as one of the Seven Angels, and also the manifestation of the Peacock Angel,Footnote 21 as one of the four elements of the world, and also as the Sun (Şems), or, to be more exact, as its spirit or intellect. In one of the Yezidi beyts that can be heard in Iraq, the following words are sung:

What is more, believing in reincarnation, Yezidis identify him with a medieval Persian mystic, Shams al-Din Tabrizi, as well as Shams al-Din, a figure from Yezidi history, whose tomb is located in Lalish.

In turn, to quote a fragment of an article by a Yezidi, Khalaf Salih—“the god of the moon in the mythology of the Yezidian religion is called Malak Fakhradin.”Footnote 22 In this context, Yezidis occasionally use an expression “Manga Melek Fexredîn”—the Moon of Angel Fekhredin.Footnote 23 Additionally, he is also connected with one of the four material elements of the world, with a historical figure from the Yezidi community, Sheikh Fakhr al-Din (believed to have authored the most important qewls), as well as with the famous mystic Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (d. 1209), and even with a seventh century Nestorian monk, Rabban Hormuzd. The Yezidi rules stipulate that their Baba Sheikh must be a descendant of Fakhr al-Din line.

Figure 2. Celestial symbols in the residence of Baba Sheikh (sitting on the left), Ain Sifni, Iraq.

Source: the author.

In our context, it is worth noting that in the Yezidi Hymn of the Months, the figure of Angel Fakhradin is indeed connected with Wednesday. The hymn mentions God’s creation of the days of the week:

However, it is also the Peacock Angel that is linked with Wednesday, and with a specific planet, Mercury:

This star represents Wednesday; this day is very important in Yezidism. According to Yazidian mythology the Lord completed creation of the universe and decorated it with living objects and then life started on the earth. Thus God created the chief of Angels (Tawoos Malak). Mercury appears after a short time after sunset and sometimes at twilight so the Yezidis call it “the morning star.”Footnote 25

This and other contradictions are explained by Yezidis, who say that Fakhradin can sometimes be perceived as a personification of the Peacock Angel. The stunning diversity of incarnations of divine reality on display here is an obvious effect of the manifestations of godhead or God (called “Padishah”) in the world. I make this distinction as it is not always easy to say when Yezidis mean God, and when His first angel, Peacock Angel, or one of his inferiors. This ambiguity can be seen particularly in the descriptions of cosmogony, where God/god sometimes acts in person, and other times as one of the angels. For instance, in Hymn of the Black [Book] Furqan, the creation of the Moon and the Sun is described as God’s actions through the Fakhradin and Shemsedin:

The association of planets and angels is in fact known to many religious traditions, not only to the Near Eastern ones, reaching far into the past of Babylonian times. We can also encounter them in Greek philosophy (especially of Pythagoras and Plato) and their Late Antiquity commentators such as Porphyry, Iamblichus, and Proclus, who all refer to the Pythagorean and Platonic tradition, which interpreted the world of celestial bodies in astronomical and mystical terms. The tradition was particularly strong in the vicinity of Edessa (today’s Şanlıurfa)—in Harran, the famous town of Abraham. The people of the area, the so-called “Sabians,” were said to have been characterized by a religion based on the cult of the moon, the sun and planets (or rather intelligences presiding over them).Footnote 27 The religion in question, as much as we can reconstruct it based on the accounts of medieval authors, was a syncretic combination of local beliefs and Greek philosophy. It stood firm against Islam as late as the eleventh or even thirteenth century, when—as written by Ibn Shaddad (1216–85), who visited Harran in 1242—“most of the inhabitants had removed to Mardin and Mosul.”Footnote 28 Without exploring this thread further here, let me just quote a remark by Shahrastani (1086–1153 AD), Persian historiographer contemporary to Sheikh Adi. In his Book of Sects and Creeds, trying to capture the essence of Harranians’ religion, he attributed to them a kind of pantheism. According to him, they believe in one God who manifests himself in the world through the Seven Rulers (al-mudabbirāt al-sab’):

The creator whom they worship is—they say—both one and multiple. He is one as regards the essence, the beginning, the principle, eternity without origin. He is multiple, because he multiplies (in the eyes) in physical forms: they are the seven governors (and [their] earthly representations), endowed with kindness, knowledge and excellence: he manifests himself through them and individualizes himself in their physical forms, without losing his unity as to the essence. According to them, he established the spheres and all that is there of bodies and stars. And he made them the governors of our world. They are “the fathers” … living and endowed with reason.Footnote 29

Figure 3. Stele depicting the last king of Babylon, Nabonidus (reigning 556–539 BC) praying under emblems of Venus, sun and moon; found in Harran, now in Şanlıurfa Museum, Turkey.

Source: the author.

Belief in “the Seven” who rule over the world was also attributed to Bardaisan (“Son of the river Daisan”) of Edessa and his followers, called “Daisanites,” who—according to Mesopotamian monk Maruta of Maipherkat (fourth century AD)—“proclaim the Seven and the Twelve [and] deprive the Creator of the power ruling the world.”Footnote 30 We find similar beliefs in Zoroastrianism and Mandaeism. The tradition of Mandaeans, whose roots can also be traced to Harran,Footnote 31 clearly refers to “the Seven,” yet unlike in Yezidism, in Mandaism the “Seven” (planets) are identified in Ginza Rba (I 163–4) as evil beings, together with “Twelve” (signs of the Zodiac).Footnote 32 They are perceived as the sons of the serpentlike Lord of Darkness (Ur) and evil Spirit (Ruha).

For Zoroastrians in turn, “the Seven” can mean the seven planets as well, but primarily denotes seven divine entities called Ameshaspends. Their connection with cosmogony is mentioned in Bundahishn (Primal Creation), also called Zand-akasih (Knowledge from the Zand). In this Middle Persian (ca. eighth to ninth century AD) compilation of Zoroastrian cosmogony, containing traces of Greek influences,Footnote 33 we read about Ohrmazd, whose place and location was Endless Light.Footnote 34 In the beginning he created “Good Thought” (Vohu Manah/Vohuman/Bahman) and sky (asman): “The first of Auharmazda’s creatures of the world was the sky, and his good thought.”Footnote 35

The descriptions of this sky, a celestial sphere that contained everything, bring to mind the Yezidi myth on the original Pearl, from which all the elements of the world emerged. In the Pahlavi texts, the sky is described as luminous, round, hard, or even metallic. Attributes assigned to the sky result to some extent from the etymology of the word “asman,” which occurs in Avesta in the sense of “stone,” and resembles words such as “asen” (iron) and “asemen” (silver). In addition, this original spherical sky is compared to jewel and white crystal.Footnote 36 After the Vohuman and sky, Ohrmazd created Ameshaspends:

He, first, created forth Vohuman, out of Good-Progress, the Essence of Light, with whom there was the good Mazdayasnian Religion; He knew that it will reach the creatures, [up to] the renovation; and then, [He created] Ardwahisht, then Sahrewar, then Spendarmad, then Hordad and Amurdad.Footnote 37

Together with Ohrmazd and Vohuman they constitute seven Ameshaspends, the Good Heptad, connected with the seven stages of creation that occurred later. Their opponents are in turn six bad demons, who under the leadership of Ahriman form the Evil Heptad.

Ohrmazd created elements of the world through Vohuman, who therefore can be perceived as a demiurge (which brings to mind the role of Logos in the Christian theology). Similar to the Yezidi cosmogony, the first stages of creation and the first world was incorporeal and purely formal,Footnote 38 which remained in the state of menog for three thousand years before its material dimension (getig) emerged. The first creatures of Ohrmuzd can be seen as his manifestations or emanations:

Out of His own Self, out of the Essence of Light, Ohrmazd created forth the astral body of His own creatures, in the astral form of luminous and white Fire, whose circumference is conspicuous.Footnote 39

Then the first creatures gained a corporeal dimension, but for the next 3,000 years remained unmoving. As we read in Zadsparam:

Three thousand years the creatures were possessed of bodies and not walking on their navels; and the sun, moon and stars stood still. … And in aid of the celestial sphere he [Auharmazd] produced the creature Time (Zorvan); and Time is unrestricted, so that he made the creatures of Auharmazd moving.Footnote 40

The movement appears with Time (Zurvan), although his position in Zoroastrianism has changed over the course of history and has even resulted in the rise of a Zurvanite heresy. It is worth noting that Time (Chronos) plays a similar role in ancient western cosmogonies, in which it was identified with the Greek god Kronos and then with Roman Saturn.Footnote 41

In one of the Pahlavi texts, Dina-i Mainog-i Khirad, Zurvan was described as a co-creator: “The creator, Auharmazd, produced these creatures and creation, the archangels and the spirit of wisdom from that which in his own splendour, and with the blessing of unlimited time (zorvan).”Footnote 42 In the text we find the same qualification of the seven planets (and twelve signs of the Zodiac) as by Mandaeans:

Every good and the reverse which happen to mankind and also to other creatures, happen through the seven planets and the twelve constellations. … And those seven planets are called the seven chieftains who are on the side of Aharman. Those seven planets pervert every creature and creation and deliver them up to death and every evil. And as it were, those twelve constellations and seven planets are organizing and managing the world.Footnote 43

Mandaeism and Zoroastrianism share a reserve to the material world, which is a kind of visible proof of the degradation of an ideal reality. The creation of the present world, the one as we know, was a consequence of the Ahriman’s attack on the ideal world of Ohrmuzd. After he caused the sky to crack, broke a hole and got inside “in likeness of a serpent,” he killed the first creatures, and the remnants started to multiply. As Plutarch noted “from here comes that evil things were intermixed with the good ones.”Footnote 44Bundahishn:

In likeness of a serpent he darted to the sky below the earth, he trampled it apart and broke it. In the month of Fravartin (first month), the day of Ohrmazd (first day) he entered at midday and the sky feared him as does the sheep the wolf.Footnote 45

Ahriman smashed the original unity. The present world, as known to us, arose from dismembered ideal beings. It is based on opposites and its time is counted by the succession of day and night, the moon and the sun.

When is Wednesday?

For Yezidis, in accordance with the tradition also known to other religions, together with the sunset a day ends and another one begins. It is well illustrated by the Hymn of the Black Furqan quoted above, where the establishment of “night and day” (şêv û roj) and the moon and the sun is mentioned in this very order. Therefore, for Yezidis also Wednesday begins with the setting of the sun. Looking from our perspective, they gather for Wednesday prayers on Tuesday evening. A Yezidi pir characterizes the specifics of this special day as follows:

According to the Yezidi tradition, when the sun begins to set, another day comes. Therefore, on Tuesday evening, as soon as the sun has set, Wednesday begins. Prayers start in sanctuaries, paraffin lamps are lit, the so-called çira, one can smell fragrances—we call them bkhur—and a ceremony is conducted. When Wednesday comes, one must not bathe, shave, wash, sew, spouses should not sleep together—all of this because of the sacred character of Wednesday. In turn, on Wednesday evening, Thursday commences.Footnote 46

The process of determining days, weeks, month and years is related to the position of the sun and the moon. They are also used to establish on which days religious ceremonies will fall. It needs to be borne in mind that unlike in Judaism or Christianity, in the Yezidi religion celestial bodies (or their spirits) are also objects of cult. Each and every Yezidi is obliged to pray daily at dawn, kissing the first rays of the rising sun touching the ground, and directing their face towards the sun. They also says their prayers at sunset.

Yezidis have their own names for the months,Footnote 47 their own measure of years and time cycles and even periodic cataclysms. However, they often also use local calendars, adapting them to their own needs. Their festivals fall into two categories: those that are determined by the lunar calendar, and those whose day is established by the solar calendar, as is the case with the festival of the New Year (Serê Sal), which begins in spring on the first Wednesday of the month of Nisan.Footnote 48 That is why another name of this festival is Çarşemiya Sor, which according to the Yezidis can be translated as “Red Wednesday” or the “Festival of Wednesday.”Footnote 49 It would thus be easy to assume that the choice of the most holy day in the week is a simple consequence of it being adopted as the beginning of the new year and a new cycle, and therefore the first day. However, this gives rise to another question: why would Wednesday be the first day? According to Yezidi tradition passed on in religious hymns, Saturday or Sunday should be regarded as the first day, as it was on those days that God began the creation of the universe. Following that calculation, Wednesday is the fourth or fifth day of the week, and definitely not the first one; what is more, in a sense, it commences on Tuesday, so on the third or fourth day.

Figure 4. Yezidi Feqir prays with his face to the sun, Lalish.

Source: the author.

The information about the numeration of particular days of the week can be found in Yezidi hymns and apocrypha. According to these sources, the creation of the world was preceded by a static state, when God was in the Pearl (Dur) created out of his Mystery (Sur). The same thread is present in the Yaresan cosmogony, which seems to indicate the co-origin of both religions.Footnote 50 After the Pearl was broken an ocean poured out of it, containing four elements of the universe, which then were gathered with the presence of Love, which acted as rennet.Footnote 51 The creation of each of the days of the week is said to have been accompanied by the creation of God’s angels, also called the “Seven Mysteries.” Each of them presides over one of the celestial spheres, and each rules over a particular cycle of time.

The Yezidi numeration of the days of the week is provided by one of the most important hymns, Hymn of the Week Broken One, which extols the creation of the universe by “Padishah” (Padşa):

Similar words can be found in a piece of lower status, Hymn of Sheikh and Akub, in which, to Sheikh’s question, Akub answers that the process of creating the universe lasted from Saturday to Friday:

However, in the Hymn of Months a different numeration was suggested:

Whereas in an apocryphal text, Meshefa Resh, we can read that God did as follows after creating the white Pearl:

On the first day, Sunday, God created Melek Azazil,Footnote 57 and he is Ta’us-Melek, the chief of all. On Monday he created Melek Dardael, and he is Sheikh Hasan. Tuesday he created Melek Israfel, and he is Sheikh Shams [ad-Din]. Wednesday he created Melek Mikhael, and he is Sheikh Abu Bakr. Thursday he created Melek Azrael,Footnote 58 and he is Sajad-ad-Din. Friday he created Melek Shemnael, and he is Nasir-ad-Din. Saturday he created Melek Nurael, and he is Yadin [Fakhr-ad-Din].Footnote 59 And he made Melek Ta’us ruler over all. After this God made the form of the seven heavens, the earth, the sun, and the moon.Footnote 60

The juxtaposition of the above fragments causes a few serious complications. The last two include specific numeration that makes us regard Wednesday as the fourth day. The two first ones, on the other hand, suggest that Wednesday must be regarded as the fifth day of the week. In fact, a hypothesis can be made that the apocryphal text was composed by one of the local Christian monks,Footnote 61 who not only confused the order of the angels but also imputed to the Yezidis his own numeration of the days of the week, in which Sunday is the first day. However, Sunday also comes as the first day according to the third quoted fragment, which is undoubtedly of Yezidi provenance. Albeit the numeration it contains can be an effect of the etymological and phonetic relation of the word “çarşem” (Wednesday) with the numerical “çar” (four). In a sense, through the constraints of their own language, Yezidis are forced to assume a certain perspective. Thus while talking of Wednesday, whether they want it or not, they have to call it “the fourth day” (çar-şem).

If we assume that the above four quotations represent a trustworthy “explanation” of Yezidis’ count of the days of the week, to avoid discrepancies we would have to assume that the quotes come from different periods, between which either the numeration or terminology describing the days of the week, or the perception of the beginning of the day had changed. A different solution could lie in accepting Saturday (şemî) to be the “zero day,” in which God, while creating the basis or foundation, is preparing for the creation started on Saturday evening, and therefore with the beginning of Sunday. Then Wednesday would be regarded as the fourth day.Footnote 62 Yezidi Qewwals, with whom I had an opportunity to talk about this subject in their home twin villages of Bashiqe and Bahzani, confirmed such numeration of this particular day for Yezidis.

It needs to be added here that in one of the Yezidi hymns, the Hymn on the Creation of the World, beginning with the words “O Lord! There was darkness in the world” (“Ya Rebî dinya hebû tarî … ”), yet another order of days, different from the ones mentioned above, can be found:

However, this version of the hymn raises serious doubts among YezidisFootnote 64 and some of them consider it to be falsified.Footnote 65 It may be a testimony of some internal debate over the numeration of the days of the week and over choosing the day for the Yezidi festival of the New Year, which, as believed by some Yezidis, might have been celebrated originally on a different day than Wednesday.Footnote 66 I have also encountered different attempts to explain this stanza, for example suggesting that Wednesday was to be understood as the day the creation of earth only was completed, and not the whole universe.

Wednesday—The Fourth Day, the First Day

For further consideration, it will be helpful to refer to the work of Biruni (d. 1048 AD), Kitāb al-āthār al-bāqiyah ‘an al-qurūn al-khāliyah known as The Chronology of Ancient Nations. Apart from filing countless facts about various cultures and religions, this Persian scholar often provided shrewd philosophical comments, which allow one to notice the idea manifested in the form of social phenomena. His work begins with the study of day, or to be more precise with the reflection over day and night, the “day-night” ( بليلته اليوم ), or, if we refer to Greek terminology—“Nychthemeron.” While enumerating different approaches to understanding it, he notes:

The Arabs assumed as the beginning of their Nychthemeron the point where the setting sun intersects the circle of the horizon. Therefore their Nychthemeron extends from the moment when the sun disappears from the horizon till his disappearance on the following day. They were induced to adopt this system by the fact that their months are based upon the course of the moon, derived from her various motions, and that the beginnings of the months were fixed, not by calculation, but by the appearance of the new moons. Now, full moon, the appearance of which is, with them, the beginning of the month, becomes visible towards sunset. Therefore their night preceded their day; and, therefore, it is their custom to let the nights precede the days, when they mention them in connection with the names of the seven days of the week.Footnote 67

He then provides a philosophical explanation:

Those who herein agree with them plead for this system, saving that darkness in the order (of the creation) precedes light, and that light suddenly came forth when darkness existed already; that, therefore, that which was anterior in existence is the most suitable to be adopted as the beginning. And, therefore, they considered absence of motion as superior to motion, comparing rest and tranquillity with darkness, and because of the fact that motion is always produced by some want and necessity.Footnote 68

Figure 5. Yezidis praying under the sun, moon and stars symbols in Lalish.

Source: the author.

Biruni juxtaposes this system with others, for example the Byzantine one, in which the beginning of day and night (as well as a month) is determined by the moment of sunrise. Here also a philosophical commentary is provided:

Therefore, with them, the day precedes the night; and, in favour of this view, they argue that light is an Ens, whilst darkness is a Non-ens. Those who think that light was anterior in existence to darkness consider motion as superior to rest (the absence of motion), because motion is an Ens, not a Non-ens—is life, not death.Footnote 69

This description is also present in Torah’s book of Genesis, where we can read that among the darkness and vastness of waters, light was created, and day is defined here as the “evening and morning.” The Jewish tradition proves to be highly relevant in this case, as it connects the cosmogony with the numeration of days, which, together with specific meaning ascribed to them, has been adopted by many peoples of the Near East. If we assume that Wednesday constitutes the fourth day, its particular sacred character in Yezidism may be connected with the significance given to that specific day in Torah (Genesis 1, 14–19):

And God said, “Let there be lights in the expanse of the heavens to separate the day from the night. And let them be for signs and for seasons, and for days and years, and let them be lights in the expanse of the heavens to give light upon the earth.” And it was so. And God made the two great lights—the greater light to rule the day and the lesser light to rule the night—and the stars. And God set them in the expanse of the heavens to give light on the earth, to rule over the day and over the night, and to separate the light from the darkness. And God saw that it was good. And there was evening and there was morning, the fourth day.Footnote 70

To compare the terminology, let me quote the same fragment in the Kurmanji translation (by the British Bible Society):

Hingê Xwedê got: «Bira sînorê qedîmîya e’zmênda r’onayîdar derên, wekî r’ojê ji şevê biqetînin û we’da, r’oj û sala nîşan kin û bira evana sînorê qedîmîya e’zmênda r’onayîdar bin, wekî e’rdê r’onayî kin». Û usa jî bû. Xwedê du r’onayîdarêd mezin çêkirin: R’onaya mezin wekî serwêrîyê li r’ojê bike, r’onaya biçûk wekî serwêrîyê li şevê bike ûn usa jî steyrk çêkirin. Xwedê evana li sînorê qedîmîya e’zmênda danîn, ku r’onayê bidine e’rdê, serwêrîyê li r’ojê û şevê bikin, r’onayê ji te’rîyê biqetînin. Û Xwedê dîna xwe dayê ku qenc e. Û bû êvar û sibeh, bû r’o ja çara. Footnote 71

Figure 6. Sun and Moon symbols on the gate to the sanctuary of Sheikh Shams in Bozan, Iraq.

Source: the author.

Biblical exegetes noticed long time ago that the fourth day is related to the first day of creation (similarly, the fifth to the second one, and the sixth to the third one), when God commanded that there would be light, and then separated it from darkness.

Particularly valuable are the comments on the importance of the fourth day of creation by Alexandrian Jew Philo (c. 15 BC–c. 50 AD), who explained it as referring to terminology and concepts taken from Pythagorean and Platonic philosophy.Footnote 72 In his opinion, on the fourth day

the Creator having a regard to that idea of light perceptible only by the intellect, which has been spoken of in the mention made of the incorporeal world, created those stars which are perceptible by the external senses, those divine and superlatively beautiful images, which on many accounts he placed in the purest temple of corporeal substance, namely in heaven.Footnote 73

Referring to Pythagorean symbolism of the number four, Philo pointed out that it refers to the material world, “for it was this number that first displayed the nature of the solid cube, the numbers before four being assigned only to incorporeal things,”Footnote 74 “the four elements, out of which this universe was made, flowed from the number four as from a fountain.”Footnote 75 Thus it can be asserted that the fourth day (Wednesday) in the order of creation is the new beginning, or the repetition of the act of the creation of the universe, albeit on a different level, when that one abstract light takes a more specific dimension in the form of “the two great lights … and the stars.”

Pointing to the likely relation between Judaism and Yezidism, it is worthy of note that Yezidis use an enigmatic term “three letters” (sê herfa) to refer to the Sun, the Moon and stars. It was used by them for instance in the most important cosmogonic hymn, Qewlê Zebûnî Meksûr, in the verses referring to Abraham (Birahîm Xelîl), who was initially supposed to have paid homage to them in Harran (before he travelled to Mecca, where he was to have founded Ka’aba, and where then the Zem-zem spring came up from underground).Footnote 76

In the book of Genesis, as in the Yezidi hymns, the process of creation is described as the progressing concretization and differentiation of the elements of the world, which can clearly be seen in the example of the descriptions of light and darkness. First, light appears, and as we can read, “the light was good. And God separated the light from the darkness” (Genesis 1, 4).Footnote 78 Next, as a result of a division, day and night come into existence “God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night” (1, 5), and then later—specifically on the fourth day—light undergoes concretization in the lights of the heavenly vault, whose task is to “separate the day from the night.”

Following the text of Quran (XXI: 33), one can say that “He is the One who created the Sun and the Moon.” In the context of Islam, it should be noted that in the Muslim tradition Wednesday was associated with angels. Al-Tabari presents such a view—“God created the angels on Wednesday”Footnote 79—in his monumental work, History of the Prophets and Kings (Tarikh al-Rusul wa al-Muluk), in which he collected the opinions of Muslim authorities about the subject of the beginning of the universe and the consecutive stages of its creation. However, it has to be added that the Muslim tradition is not consistent as regards this issue (which al-Tabari scrupulously points out), because it is mainly based on the text of Quran and Hadiths, which are ambiguous, and often contradict each other. Al-Tabari also records a different view that “God began the creation of the heavens and the earth on Sunday, and He finished in the last hour of Friday”Footnote 80 and a Hadith according to which “God created light on Wednesday—meaning by ‘light’ the sun.”Footnote 81

Figure 7. Sun motif on a modern Yezidi grave in Armenia.

Source: the author.

Figure 8. Sun symbol on an old Yezidi grave in Jamshlu, Armenia.

Source: the author.

To sum up the above considerations, it can be stated that Wednesday is in a sense both the fourth and the first day. It is only from Wednesday onwards that we can really talk about night and day on earth, as it is on this day that the first movement appears, with life in the sun and moon and other celestial bodies. At the same time, Wednesday constitutes the end of one of the stages of creation, the more abstract one, which encompasses the first three days. It is only on the fourth day that God starts to give a more concrete shape to His ideas. On Wednesday, the world (or a model thereof) we know is created, a world where night and day are governed by the moon and the sun, which in turn are manifestations of God and the angels for Yezidis. This gradation of creation, or its concretization, has its clear parallel in Yezidi cosmogony, which begins with darkness in which the luminous Pearl appears, which then gets broken. Its remnants that bring to mind the pieces of an eggshell cracked during the Yezidi festival of Çarşemiya Sor become associated with the sun, moon and stars in the myth. As we can read in a Yezidi apocrypha, Meshefa Resh, God ordered two pieces of the said Pearl to be brought:

one he placed beneath the earth, the other stayed at the gate of heaven. He then placed in them the sun and the moon; and from the scattered pieces of the White Pearl he created the stars which he hung in heaven as ornaments.Footnote 82

Wednesday would then be for Yezidi a symbolic moment of transition from the dark state of non-corporeality and death to materiality, life and light. Wednesday can be understood as the day of the creation of the sun and the moon as well as the stars. This is the way I interpret the fragment of the Hymn of Sheikh and Akub quoted above, where there is an enigmatic statement: “On Wednesday He cut out the shirt.”Footnote 83 Wednesday is at the same time the day angels, which are connected with celestial bodies and manifest themselves through them, were called into being or “descended.” On the fourth day, light (nûr) spread around the world, like the fires that Yezidi light after dark during the spring festival of Wednesday.

Festival of Wednesday

Two festivals are particularly devoted to the Yezidi cosmogony: The “macrocosmic” spring festival Çarşemiya Sor, which commemorates the mythical moment of bringing the “body” of earth into life and submitting it to the rule of the chief of the angels, and the autumn Festival of Assembly (Cejna Cimayê), during which the “microcosmic” thread, among other, is celebrated—the bringing the body of Adam to life by submitting it to the rule of the spirit. The former is the most important to be able to understand the meaning of Wednesday in Yezidism. I will refrain from describing this spring festival in detail here as I have devoted a separate article to the issue.Footnote 84

The spring month (Nisan, April) has played a special place in the Middle Eastern religions from the times of the Babylonians through Zoroastrianism, JudaismFootnote 85 to Christianity, Yezidism and Mandaeism, to mention only a few. In Babylon at that time the New Year ritual was performed in honor of Bel, “during which the other gods acknowledge him as supreme head of Babylonian pantheon”Footnote 86 and the poem Enuma Elish about the Bel’s leading role in the creation of the world was recited. As Boiy showed, this New Year ritual still existed during the Seleucid period.Footnote 87 In turn, in the case of Christianity it should be noted that Christ was to be crucified on Nisan, the 14th day of the month, the preparation day for Passover, before sunset.

As al-Nadim reported, also the Harranian “Sabians” (who in my opinion could join the proto-Yezidi community around the eleventh or twelfth century) celebrated the beginning of the year in this month, when they venerated the moon and the seven planetary deities.Footnote 88 On the fifteenth day of Nisan, they were also reported to have worshipped a deity that was perceived to be the leader of jinns, called Shamal,Footnote 89 “with offerings, sun worship, sacrificial slaughter, burnt offerings, eating and drinking.”Footnote 90 Moreover, every day of the week they were said to have made offerings for particular planets and deities related to them. Every Wednesday, the offerings were supposed to have been made to the planet of Hermes—Mercury/Utarid.Footnote 91

The spring festival Nauruz Rba/Dihba Rba was celebrated by the Iraqi Mandaeans as well, who associated it with commemorating the spirits of forefathers and the moment when “the Mana Rabba Kabira or Great Spirit, completed his work of creation on this day.”Footnote 92 Another festival, which shows many similarities to the Yezidi one, is connected with the Iranian religious practices, as for example Šab-e sūrī, when under the Samanids a large fire was lit on the evening preceding the end of the year. But first of all Chaharshanbe-ye Suri festival should be mentioned, which is still celebrated by Iranian people. It falls in the month of Farvardin, on the night of the last Wednesday before the Nevroz.Footnote 93 It starts on Tuesday evening, when fires are lit. Celebrants jump over them and shout “Sorkhi-ye to az man, zardi-ye man az to” (“Your redness mine, my yellow-paleness yours”).

This contemporary festival has replaced an older one, Farvardegān (earlier: Hamaspathmaedaya), dedicated to the veneration of the souls of the dead.Footnote 94 In the opinion of Biruni:

On the 6th day of Farwardin … is the Great Naurôz, for the Persians a feast of great importance. In this day—they say—God finished the creation. For it is the last of the six days, mentioned before. On this [day] God created Saturn.Footnote 95

However as a result of the changes introduced to the Iranian calendar in the past, the dates of the Yezidi festival and the Iranian festival do not overlap anymore. The Iranian festival seems to be connected with the Yezidi one, although one cannot ignore the voices of some of the Yezidis that the name of their holiday (Çarşemiya Sor), which resembles the “Chaharshanbe-ye Suri,” appeared relatively recently, and formerly it was celebrated under other names as the festival dedicated to the Peacock Angel.

The main celebrations of the Yezidi Çarşemiya Sor, which take place after the equinox in the Iraqi Lalish valley, fall on the first Wednesday of Nisan (according to the Seleucid calendar, i.e. on the third Wednesday of April according to the Georgian calendar). As the Yezidi tradition dictates, the whole month is very special and one must not get married during this time, as it is a month when only angels can enter into marriage.Footnote 96 No new business activity is permitted, be it agricultural or trade; building houses and entering contracts are prohibited too. In short, the rules in force during the month when the Festival of Wednesday is celebrated are analogous to those for each Wednesday in each subsequent week.

As Yezidi tradition has it, on that particular spring Wednesday, as many as three festivals coincide, as Çarşemiya Sor is connected with the celebrations of the Festival of the New Year (Serê Sal), which is at the same time a festival devoted to the Peacock Angel, thus called the New Year of Peacock Angel (Saresale Tawusi Malak) or the Peacock Angel Festival (Eide Tawusi Malak). Yezidis explain the coincidence of so many festivals falling on one day by referring to a popular legend that one of the Yezidis from Ba’adre, Sabah Darwesh, summarized as follows:

God had examined his seven angels and Azazil had passed the exam and God named him Tawoos Malak and made him the king of angels. God sent Tawoos Malak to dissolve the ice of earth to make it suitable for plants, animals and humanity to live on it. This event happened in the first of April according to the Ezidis calendar which is the new year of Ezidis. Thus, the beginning of life on earth is the beginning of Ezidis religion. Also, April is the first month of Ezidis calendar. Because this day was Wednesday the Ezidis postpone the ceremony to it if the first of April becomes on one of the other days.Footnote 97

The Yezidi festival of Çarşemiya Sor is in a sense a reflection of the Yezidi cosmogonic myth. The festival is preceded by visits to the cemeteries, egg painting and visits to numerous sanctuaries in Lalish devoted to the Yezidi holy men and angels. Animals are killed, offerings are made, Wednesday Hymn is sung (Qewlê Çarşemê), and a game of the so-called hekkane is played, in which painted eggs are cracked. Çarşemiya Sor begins on Tuesday after the sunset, at a moment when according to the Yezidi custom a new day begins, i.e. Wednesday. Wednesday begins with darkness, similar to the world which was first shrouded by darkness. The key moment of the festival is bringing the holy fire out of the sanctuary of Sheikh Adi, upon which all the pilgrims who had gathered in Lalish light their candles from it. The holy valley resembles a sky strewn with stars. The gathered crowd give out cries of worship in adoration of the Peacock Angel and Sultan Yezid (“Hole hola Siltan Êzdî ye, hola Tawisî Melek e!”), hymns are recited and the holy instruments of Qewwals—flute and drum/tambourine—can be heard. In this context it is worth noting that this “set” of instruments boasts a very old tradition, connected for instance with the spring processions worshipping Baalshemin during which a horn and a tambourine were played.Footnote 98

At the break of dawn, a mass is formed from the colorful shells of eggs, the water from the Zem-zem spring and the scarlet anemones and curry, which is then put over door lintels. It is a symbolic representation of the new, revived world and its lively colors. Also at dawn, Yezidi clergy perform the ritual ablution of sanjak, which as the tradition dictates, should then paraded be by Qawwals around villages inhabited by Yezidis. It is a symbolic “baptism” of the Peacock Angel and the commencement of the new cycle of his rule over the world. Each subsequent Wednesday may therefore be perceived as the commemoration of events taking place in that “sacred time.”Footnote 99

Figure 9. Peacock and the Sun on the gate to the old residence of Yezidi Mîr in Baadre, Iraq.

Source: the author.

Music of the Spheres

When referring to the Greek Pythagorean tradition, one could say that the day of the creation of celestial bodies, and especially the sun and the moon and putting them in motion (breathing angels’ spirits into them), is at the same time the day when the Harmony of the Spheres was established and Musica Universalis rang out, as, according to the Pythagoreans, when moving, celestial bodies generate sound.Footnote 100 As the aforementioned Philo of Alexandria wrote, on the fourth day of the creation God set the stars and planets in motion, thanks to which the human reason (logos) perceives their light and the regularity of movements, and through contemplation focuses on the non-corporeal reality and Logos of God: “for the sight being sent upwards by light and beholding the nature of the stars and their harmonious movement … the harmonious dances of all these bodies arranged according to the laws of perfect music, causes an ineffable joy and delight to the soul,”Footnote 101

being raised up on wings, and so surveying and contemplating the air, and all the commotions to which it is subject, it is borne upwards to the higher firmament, and to the revolutions of the heavenly bodies. And also being itself involved in the revolutions of the planets and fixed stars according to the perfect laws of music.Footnote 102

I bring up this thread because it has an interesting parallel in the Yezidi tradition. As I have mentioned, Yezidis claim that the entire reality is an emanation of God/god; all its elements are related to the metaphysical world. It pertains to musical instruments as well. Yezidi associate the two holy instruments that accompany all religious ceremonies—daff (tambourine) and shebâb (flute)—with Angel Sheikh Shems and Angel Fakhradin respectively, and therefore with the sun and the moon (perhaps through the analogy of their shape). The fact these instruments can be used only by Qewwals, and other Yezidi touch them and kiss them with awe testifies to their holy nature.Footnote 103

Therefore it is not surprising that these two instruments occupy a role in the cosmogonic myth as well or, to be more precise, in the micro-cosmogonic one, as it describes a specific microcosm coming to life—Adam. After his body had been created, “Seven Mysteries” are said to have hovered around him for 700 years, which is interpreted as referring to seven angels, yet I understand them as “planets.” The creation of Adam progressed in stages, similar to the creation of the universe. According to the Yezidi cosmogony, the elements of the world were initially inanimate (this idea has a parallel in Zoroastrianism), and its coming to life was supposed to have taken place specifically on Wednesday, when the Peacock Angel was granted rule over it. The same applies to Adam—he comes to life only after some time since the moment his body was created. However, in accordance with the myth, equipping the body with an angel spirit (ruh) could not happen. Depending on the account, the spirit or angel did not want to enter Adam’s body (the myth of the refusal of the first angel to bow before Adam can correspond to that). First, spirit/angel explained his refusal by fear of sin, which the body is prone to, then he allowed himself to be persuaded, although he gave one condition that we can hear about in the Yezidi hymn Qewlê Zebûnî Meksûr:

Figure 10. The Parî Suwar Kirin ceremony, the part devoted to Fakhradin, Lalish.

Source: the author.

In oral accounts passed on among Yezidis, it is said that it was Melek Sheikh Sin who entered the body of Adam, and sometimes that it was all the seven Angels, and still on other occasions that the Angels entered the body before the spirit appeared therein.Footnote 105 However, putting life into man is also connected with the appearance of two special instruments and drinking from the cup. Adam, struck by the “light of Love” (Nûra muhibetê) and, drinking from the cup, becomes involved in mystical tradition, he takes part in mysteries: “He staggered, he was inebriated.” All these events are accompanied by music. The description of the descending “flute and tambourine” (Saz û qidûm, i.e. şibab and def) and their music seem to bring in astral symbolism. It appears that both the “Seven Mysteries” hovering above Adam’s body, as well as the two instruments, are connected with seven planets and their angel-spirits, and especially with the moon and the sun, that these instruments are devoted to in the Yezidi tradition. Such an interpretation finds confirmation for example in the fragment of The Hymn of Ezdina Mir:

Providing the body with soul or spirit, i.e. bringing it to life, is shown here as some kind of harmony of the elements of the body, one that comes from some superior harmony. To sum up, bringing Adam to life can be read as an analogy to bringing the world into life, which took place on a Wednesday.

For Yezidis, Wednesday is therefore the first day of this world (although the fourth one in the order of God’s act of creation), the day of the leader of the angels, the Peacock Angel, understood to be the light-bearing giver of life, or even an Anima mundi, of the world overseen by the sun, the moon and the stars. It is also a day that reminds us of the life and place of man in the world. Due to this fact, Wednesday can be considered to be an archetype of the beginning of the earthly time and life, which is commemorated on individual Wednesdays of each week. Each subsequent Wednesday, the Peacock Angel’s taking over of the rule over the world is celebrated.