Introduction

In 2001, Hoffmann and Tarzian published “The Girl Who Cried Pain: A Bias against Women in the Treatment of Pain.”Reference Hoffmann and Tarzian 1 The article explored what was known at the time about how men and women experienced and reported pain, and how women, as compared to men, were treated for their pain. The authors sought to determine whether there were differences in the biological and psychosocial bases for pain between men and women, whether men and women experienced pain differently, and whether there were treatment disparities for pain linked to sex.

Based on a review of the literature, they found that women were more likely than men to experience (or at least report) a number of chronic pain conditions. These included migraines and chronic tension headaches, facial pain, musculoskeletal pain and pain from osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia. In addition, in experimental settings, women had lower pain thresholds (the least intense stimulus that produces pain), higher ratings of pain stimuli, and lower pain tolerance (the most intense pain stimulus one is willing to tolerate) than men. Hoffmann and Tarzian explored what might account for these differences including biological differences, e.g., hormones, genetics, and differences in the brain and central nervous system, and psychosocial and cultural factors, such as gender role expectations, behavioral coping, and socialization. Despite the differences in pain experience, and that women were more likely to seek treatment for their chronic pain than men, several studies indicated that women were more likely to be inadequately treated by health care providers (HCPs) for their pain, including a study that found that men were more likely to be given opioids, and women sedatives, after abdominal surgery.Reference Calderone 2 Hoffmann and Tarzian ascribed this finding and similar findings from other research to HCPs “who, at least initially, discount[ed] women’s verbal pain reports and attribute[d] more import to biological pain contributors than emotional or psychological pain contributors.” 3 Other studies hypothesized that it could be due to differences in the way men and women communicate with their physicians as well as how patients are perceived by their physicians.Reference Miaskowski 4 One study found that physicians’ treatment of female patients was related to their appearance and whether they presented with hostility,Reference Hadjistavropoulos, McMurtry and Craig 5 whereas these same characteristics were not related to how men were treated.

In this article, we examine these questions again, twenty years later. Specifically, we first explore what we have learned in the last two decades regarding pain more generally, including new concepts about the pain experience. Next, we report on studies of biological and psychosocial differences between men and women that may explain their different pain experiences. Third, we examine the literature on gender- and sex-based disparities in pain treatment to determine whether there is evidence that it remains a problem. Fourth, we examine several explanations for why HCPs might treat men and women differently for their chronic pain. And, last, we make recommendations as to how sex-based disparities in treatment may be mitigated.

In this article, we examine these questions again, twenty years later. Specifically, we first explore what we have learned in the last two decades regarding pain more generally, including new concepts about the pain experience. Next, we report on studies of biological and psychosocial differences between men and women that may explain their different pain experiences. Third, we examine the literature on gender- and sex-based disparities in pain treatment to determine whether there is evidence that it remains a problem. Fourth, we examine several explanations for why HCPs might treat men and women differently for their chronic pain. And, last, we make recommendations as to how sex-based disparities in treatment may be mitigated.

We focus primarily on sex as a binary characteristic based on reproductive organs and functions assigned by chromosome complement.Reference Boerner, Chambers, Gahagan, Keogh, Fillingim and Mogil 6 We distinguish sex from gender, which we understand is a person’s self-representation as male or female. We also recognize that these constructs are outmoded in that during the last two decades there has been a greater understanding that sex not only includes individuals who are male and female but also those who are intersex (i.e., whose physical characteristics are not one sex or another but may include attributes of bothReference Montañez 7 ). In addition, we have come to understand that gender exists on a spectrum including those who do not identify with any gender (agender), those who do not identify with the sex they were assigned at birth (transgender) and those who identify with both genders or see themselves as “between genders” or “beyond” gender (genderqueer). 8 With some minor exceptions,Reference Strath, Sorge, Owens, Gonzalez, Okunbor, White, Merlin and Goodin 9 because these developments in the field of sex, gender, and identity are still quite new, the research on chronic pain has not yet incorporated them and thus we do not yet have data linking these categories to the experience of ongoing pain.

New Developments in Pain Research and Understanding

The past 20 years have witnessed considerable growth in research addressing sex-dependent biological pain mechanisms, in part fueled by the “sex as a biological variable” (SABV) policy adopted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).Reference Clayton and Collins 10 While Congress required the agency to ensure that women were included in all clinical research in 1993, 11 it was not until 2014 that NIH adopted the SABV policy requiring inclusion of both female and male animals in NIH-funded preclinical research. 12 In fact, nearly 80% of animal studies published in the journal Pain from 1996 to 2005 used only male subjects.Reference Mogil 13 It took decades before the NIH and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) realized that women were not just a smaller version of men. The SABV policy has resulted in greater inclusion of both sexes in preclinical animal studies as well as increased attention to potential sex differences in research design and data analysis in both animal and human studies. While preclinical animal research does not always translate directly to humans, the requirement has produced significant advances in knowledge regarding biological mechanisms relevant to sex differences in humans. Additional factors generating new insights regarding biological contributions to sex differences in pain include conceptual and methodological advances that have informed chronic pain research. Three important developments have been particularly relevant to sex differences research: (1) the concept of central sensitization, (2) increased interest in understanding how and why disparate chronic pain conditions co-occur in some people (termed “chronic overlapping pain conditions”), and (3) greater emphasis on subgrouping individuals with common symptoms, characteristics and/or similar disease mechanisms, i.e., phenotyping of individuals with chronic pain.

While the gate control theory, published in 1965, highlighted the importance of the central nervous system (CNS), i.e., the brain and spinal cord, in the experience of pain, pain continued to be primarily viewed as originating in the peripheral tissues where the symptoms are experienced. Recent research, however, has expanded our knowledge of the role the central nervous system plays in processing these peripheral inputs. A new development has been the identification of central sensitization, which happens when the CNS becomes hypersensitive and amplifies pain signals, i.e., it overreacts to normal signals of pain, pressure, temperature, and/or movement.Reference Woolf 14 Individuals with central sensitization experience widespread heightened sensitivity to pain and reduced ability of internal pain control systems (i.e., inhibitory pathways) to suppress pain perception. The condition often arises after sustained acute pain, but not always. While the concept of central sensitization was initially described nearly 40 years ago,Reference Woolf 15 its integration into our thinking about chronic pain has increased dramatically in the past 10-20 years. Central sensitization highlights the limitations of prior conceptualizations of pain, which viewed pain primarily as a symptom of actual or potential tissue damage. Indeed, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) recently introduced a new subtype of pain, nociplastic pain, defined as “pain that arises from altered [pain sensation] despite no clear evidence of actual or threatened tissue damage … or evidence for disease or lesion … causing the pain.”Reference Kosek, Cohen, Baron, Gebhart, Mico, Rice, Rief and Sluka 16 While this definition does not specifically mention central sensitization, this is certainly implied as an important component of nociplastic pain. 17 In fact, the pain conditions highlighted as prototypical examples of nociplastic pain (e.g., fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, nonspecific chronic low-back pain, temporomandibular disorders, irritable bowel syndrome) all have demonstrated evidence of body-wide hypersensitivity to pain, one of the hallmarks of central sensitization.Reference Harper, Schrepf and Clauw 18 Notably, most of these conditions also show greater prevalence in females than males.Reference Fillingim, King, Ribeiro-Dasilva, Rahim-Williams and Riley 19 One factor driving increased appreciation for the importance of central sensitization in many chronic pain conditions has been advances in neuroimaging that can noninvasively characterize CNS processing of pain. Abundant evidence now demonstrates that altered brain structure and function are part of the pathogenesis of chronic pain, further supporting central sensitization as a mechanism of high clinical significance.Reference Coppieters, Meeus, Kregel, Caeyenberghs, De Pauw, Goubert and Cagnie 20

The second development over the past 10-20 years has been a burgeoning interest in understanding why someone with one chronic pain condition often develops other chronic pain conditions, also called chronic overlapping pain conditions (COPCs).Reference Maixner, Fillingim, Williams, Smith and Slade 21 Although not an exhaustive list, the pain conditions that typically occur together are highlighted in Table 1. Most of the listed conditions are substantially more common in females than males, with some being female-specific. Because these COPCs show high coexistence and occur more frequently in women, some experts believe that they may be caused by the same pathogenic mechanisms.

Table 1 Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions

Among people with one pain condition, sex appears to be a risk factor for experiencing an increased number of co-occurring pain conditions.Reference Mun, Ruehlman and Karoly 22 Individuals with COPCs also show evidence of experiencing central sensitization. Moreover, psychosocial stress is a common risk factor for development and persistence of COPCs.Reference Fillingim, Ohrbach, Greenspan, Sanders, Rathnayaka, Maixner and Slade 23 The recent increased awareness of the high rates of COPCs has revealed shortcomings in prior clinical research, as many studies have focused on a single pain condition, while either excluding individuals who report additional chronic pain conditions or simply failing to identify the presence of COPCs.

The third important development in pain research that has implications for understanding sex differences is systematically classifying people with a given pain condition by similar symptoms and/or underlying disease mechanisms to identify subgroups within that condition. This approach, termed phenotyping,Reference Edwards, Dworkin, Turk, Angst, Dionne, Freeman and Hansson 24 recognizes that considerable heterogeneity exists within any single pain condition, such that even in people with the same pain condition, there is tremendous variability in signs, symptoms, and associated features. The goal of this approach is to classify individuals whose pain may be driven by different underlying mechanisms, as this has important implications for treatment. One example is temporomandibular disorder (TMD). In the OPPERA (Orofacial Pain: Prospective Evaluation and Risk Assessment) Study,Reference Slade, Ohrbach, Greenspan, Fillingim, Bair, Sanders and Dubner 25 researchers performed comprehensive phenotyping on a large number of individuals with and without TMD. Cluster analysis then identified three subgroups of individuals: 1) an “adaptive” cluster who exhibited low psychological symptoms and low pain sensitivity, 2) a “pain-sensitive” cluster who showed generally low psychological symptoms but high pain sensitivity, and 3) a “global symptoms” cluster who had high psychological symptoms and high pain sensitivity.Reference Bair, Gaynor, Slade, Ohrbach, Fillingim, Greenspan, Dubner, Smith, Diatchenko and Maixner 26 Notably, females were overrepresented in the “pain-sensitive” and “global symptoms” clusters. Another example is fibromyalgia, which also presents with significant variability in symptoms from patient to patient. These symptoms include, but are not limited to, pain, cognitive impairment, mood disorders, fatigue, lack of restorative sleep, painful bladder and restless leg syndromes, GI dysfunction, and vulvodynia. In a 2016 publication, researchers identified four subgroups of patients with fibromyalgia based on “pain, physical involvement, psychological function and social support.” The authors concluded that these subcategories may lead to better management of patients by “more comprehensive assessment of an individual patient’s symptoms.”Reference Yim, Lee, Park, Kim, Nah, Lee and Kim 27 Many other such examples are also available.Reference Braun, Evdokimov, Frank, Pauli, Uceyler and Sommer 28

Biological Mechanisms Related to Sex: What Have We Learned in the Last Two Decades?

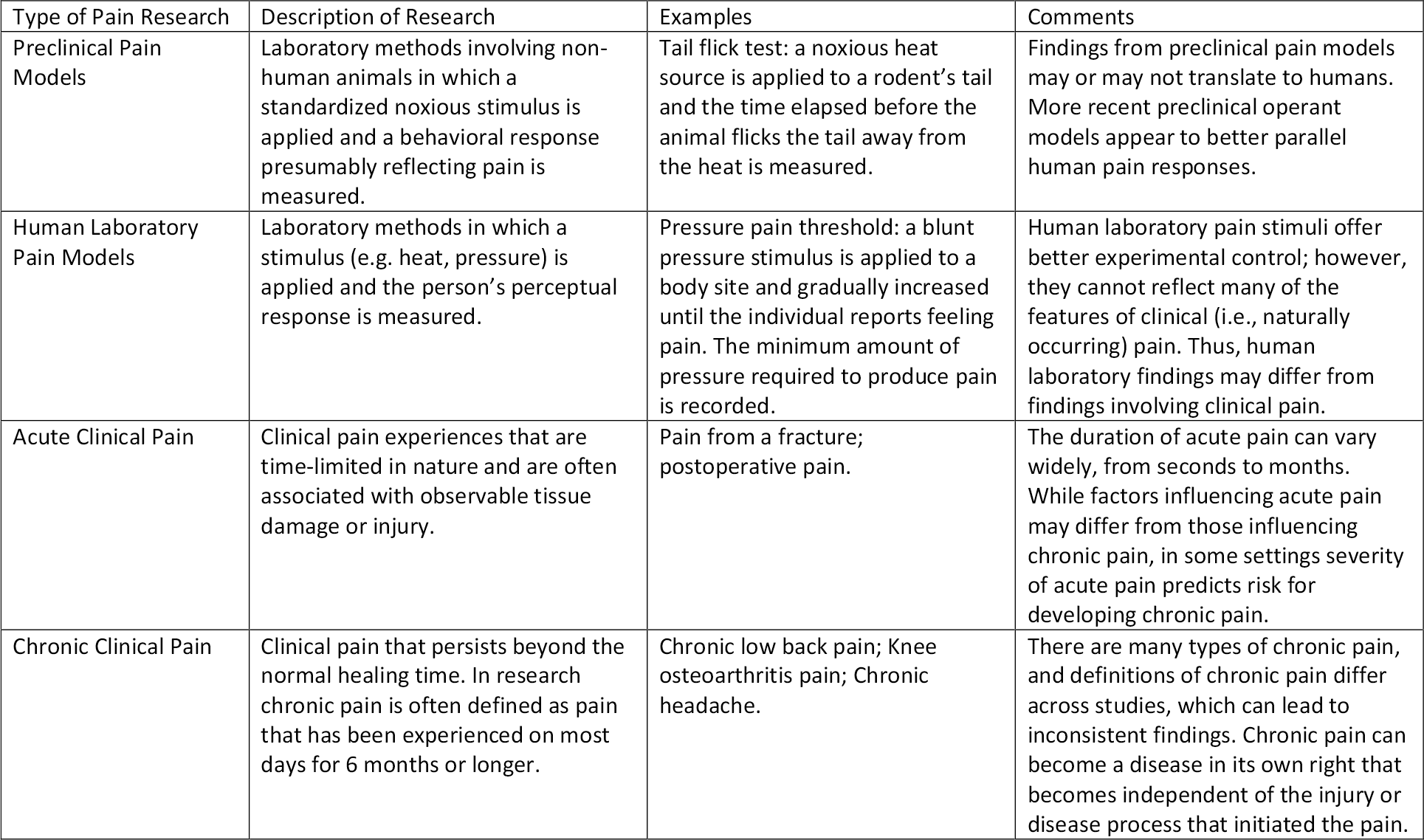

During the last two decades, researchers have continued to explore biological causes for differences in pain experience between men and women, building on research from before 2000. During this time some important insights have emerged, particularly in the areas of immunity and genetics. In addition, researchers have affirmed or disputed earlier findings and have discovered more refined bases for differences that they earlier understood to be a cause of disparities in pain between the sexes. Most of this research has focused on hormonal, genetic, and neurochemical factors along with brain structure and function and response to analgesics. This research has included pre-clinical animal studies, laboratory studies with human subjects and clinical studies with patients experiencing chronic pain. These different types of studies are described in Table 2.

Table 2 Different Types of Pain Research Used to Examine Sex and Gender Differences

Hormonal Factors: Although researchers and clinicians have known for some time that sex hormones contribute to sex differences in pain, over the past two decades we have learned that estrogens’ influences on pain are far more nuanced than previously thought, because effects can differ based on several factors. These include tissue-specific actions of estrogens, levels and timing of estrogens, interactions with other concurrent hormones, and stage of lifespan.Reference Craft 29 There are two main types of hormonal influences relevant to pain: 1) developmental influences whereby prenatal and neonatal hormonal events, as well as age of menarche, produce long-lasting effects on biological systems (e.g., the CNS) that influence pain; and 2) ongoing influences in which current changes in hormones influence simultaneous pain-related responses.Reference McCarthy, Arnold, Ball, Blaustein and De Vries 30 Since 2000, based on studies in humans, we have learned that in the developmental realm, earlier age of menarche has been associated with increased risk for menstrual pain,Reference Yamamoto, Okazaki, Sakamoto and Funatsu 31 chronic upper extremity painReference Wijnhoven, de Vet, Smit and Picavet 32 and chronic pelvic pain.Reference Latthe, Mignini, Gray, Hills and Khan 33 These findings, while somewhat complex, suggest that early hormonal influences may impact pain experiences in adulthood.

As to ongoing hormonal influences, menstrual cycle has long been thought to influence pain, but research conducted in recent years suggests that menstrual cycle influences on pain perception may be smaller and less consistent in their effects than we previously understood.Reference Pogatzki-Zahn, Drescher, Englbrecht, Klein, Magerl and Zahn 34 Studies since 2001 have also examined the effects of pregnancy on pain. Prior to 2001, pregnancy-induced analgesia had been well documented in preclinical/animal models.Reference Dawson-Basoa and Gintzler 35 More recently, researchers have observed that in women with TMD and migraine headaches, pain declined over the course of pregnancy and returned to pre-pregnancy levels after childbirth, suggesting that the hormonal changes accompanying pregnancy may be protective against pain in women for some chronic pain conditions.Reference LeResche, Sherman, Huggins, Saunders, Mancl, Lentz and Dworkin 36

In addition to investigating ovarian hormones as risk factors for greater pain among women, some research has addressed whether testosterone might be protective against pain, which might contribute to the lower burden of pain reported by men.Reference Melchior, Poisbeau, Gaumond and Marchand 37 However, study results have differed in that regard. For example, in some studies higher testosterone predicted lower pain sensitivity,Reference Bartley, Palit, Kuhn, Kerr, Terry, DelVentura and Rhudy 38 while others showed no association between circulating testosterone levels and pain perception.Reference Ribeiro-Dasilva, Shinal, Glover, Williams, Staud, Riley and Fillingim 39 Higher testosterone has also been linked with lower pain levels after total knee replacement surgery,Reference Freystaetter, Fischer, Orav, Egli, Theiler, Münzer, Felson and Bischoff-Ferrari 40 and higher daily testosterone was correlated with lower daily pain severity in women with fibromyalgia.Reference Schertzinger, Wesson-Sides, Parkitny and Younger 41

The above findings demonstrate that sex hormones exert complex influences on the experience of pain, which should not be surprising given the numerous biological systems with which these hormones interact.

Genetic Factors: New insights into pain differences between the sexes have also come from genetic research. Genetic factors clearly contribute to pain, and many studies now suggest that some genes may influence pain differently in females and males.Reference Mogil 42 For example, redheaded females with one or more variants of the melanocortin-1 receptor gene (MC1R), showed greater pain relief from mixed-action opioid medications (i.e., those that produce effects by activating more than one type of opioid receptor), while this gene was not related to analgesia in men.Reference Mogil, Wilson, Chesler, Rankin, Nemmani, Lariviere and Groce 43 Several commonly studied “pain genes” have also shown an association with pain that differs by sex. 44 These sex-specific genetic associations imply that these genes contribute to biological processes that may have fundamentally different effects on pain in women than men. Hence, therapeutic efforts targeting the biological pathways influenced by these genes would be expected to produce divergent effects in women and men.

Neurochemical Factors: Multiple neurochemical processes contribute to pain processing, and recent evidence has revealed that the influence of these processes on pain often differs for females versus males. 45 One example noted by Mogil 46 involves calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), which is a protein involved in pain transmission that is strongly implicated in the occurrence of migraines. A recent animal study found that CGRP applied to the membrane surrounding the brain caused headache-like responses only among female rats.Reference Avona, Burgos-Vega, Burton, Akopian, Price and Dussor 47 This example is important because several new drugs have been approved for migraine that work by blocking CGRP, and if the effects of CGRP on migraines is fundamentally different in females and males, these medications could show different efficacy for women and men. Several other neurochemicals can influence pain differently by sex, including dopamine, NMDA receptors, vasopressin, oxytocin, prolactin, and serotonin. 48

Immune Responses: Immune processes also seem to affect pain differently in females and males.Reference Halievski, Ghazisaeidi and Salter 49 Animal studies have shown that different types of immune cells are responsible for neuropathic and inflammatory pain hypersensitivity in females and males. Activation of glial cells (cells that support the function of the CNS) seem to cause male hypersensitivity, while T cells (cells that perform a critical function in immunity to foreign substances) seem to be the culprit in females.Reference Rosen, Ham and Mogil 50 Additional findings further support important sex differences in immune responses to painful injury.Reference Noor, Sun, Vanderwall, Havard, Sanchez, Harris and Nysus 51 Findings from human clinical and laboratory studies also demonstrate sex differences in immune response to pain, with the balance of findings revealing more robust immune/inflammatory reactivity among females.Reference Lasselin, Lekander, Axelsson and Karshikoff 52 Limited evidence suggests that experimental immune activation leads to greater increases in pain responsivity among women than men. These findings support important sex differences in immune and inflammatory responses, suggesting that efforts to target these processes in pain therapeutics may require development of sex-specific treatments.

Brain Structure and Function: Noninvasive neuroimaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and accompanying analytic methods have advanced dramatically over the past two decades, and these advances have brought new information regarding sex differences in pain-related brain structure and function. Numerous studies have documented that chronic pain is associated with structural changes in the brain, particularly reductions in cortical thickness or gray matter volume in several pain-related brain regions. 53 Some studies have shown that some of these changes in pain-related brain structure may differ by sex, but the pattern of results differs across studies, possibly because of differences in the pain conditions and age groups being studied.Reference Gupta, Mayer, Fling, Labus, Naliboff, Hong and Kilpatrick 54 We now know that brain function is also strongly related to pain, including the extent to which different brain regions show coordinated changes in their activity, known as functional connectivity.Reference Pfannmöller and Lotze 55 Sex differences in functional connectivity (a measure of the cross-talk between brain regions) have also been explored, with the most consistent findings suggesting sex differences in connectivity of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a brain region involved in high-level cognitive functions, including decision-making and social judgements, as well as pain perception. Several studies have shown that the connectivity of the ACC with other brain regions differs by sex, both in healthy individuals and in those with chronic pain.Reference Coulombe, Erpelding, Kucyi and Davis 56

Responses to Opioids and Other Analgesic Medications: Sex differences in response to analgesic medications, particularly opioids, have received considerable empirical attention over the last two decades. Limited research has reported sex differences in the effectiveness of opioids for chronic pain.Reference Pisanu, Franconi, Gessa, Mameli, Pisanu, Campesi, Leggio and Agabio 57 Animal studies clearly demonstrate that the analgesic effects of opioids are substantially greater in male versus female animals. 58 In contrast, meta-analyses of clinical and experimental studies in humans concluded that women experience greater opioid analgesia than men, with mixed action opioids showing the largest effects for postoperative pain and morphine-like medications producing the most consistent effects against experimental pain.Reference Niesters, Dahan, Kest, Zacny, Stijnen, Aarts and Sarton 59 In addition, women report greater adverse side effects following acute administration of opioids.Reference Riley, Hastie, Glover, Fillingim, Staud and Campbell 60 However, chronic opioid administration reduces testosterone in both sexes, but to a greater extent in men than women.Reference Coluzzi, Billeci, Maggi and Corona 61 In addition to impairing sexual function, this hormonal change may reduce the analgesic effects of opioids and disrupt quality of life for both women and men. Finally, opioid misuse, overdose and death, all show consistently higher rates in men than women.Reference Hoopsick, Homish and Leonard 62 Indeed, while females are more likely to be exposed to opioids, males are at greater risk for dose escalation and both fatal and non-fatal overdose.Reference Brady, Giglio, Keyes, DiMaggio and Li 63 Sex differences in responses to other classes of analgesics have not been as systematically studied. Preclinical evidence suggests that cannabinoids produce greater analgesic activity in females than males;Reference Blanton, Barnes, McHann, Bilbrey, Wilkerson and Guindon 64 however, there is limited human research that has examined sex differences in their analgesic effects.Reference Cooper and Craft 65

An important consideration in interpreting clinical studies of analgesic medications is that sex differences may emerge for reasons beyond the direct effect of the drug. Placebo analgesic responses have been widely documented, in which individuals show significant pain reductions in response to a sham treatment when they believe an actual treatment was administered.Reference Colloca and Barsky 66 An opposite effect, the nocebo response, has also been demonstrated in which people experience increased pain following an intervention when led to believe that the intervention will worsen their pain. 67 Multiple studies have shown that males appear to exhibit greater placebo analgesia than females, while females show a greater nocebo response.Reference Enck and Klosterhalfen 68 Because the expectations underlying placebo and nocebo responses can also influence how people respond to actual pain treatments, sex differences in placebo and nocebo effects may contribute to the patterns of sex differences observed in clinical studies of analgesic responses.

Summary of Biological Contributions to Sex Differences in Pain: Studies have continued to confirm observations from 20 years ago that women have more frequent pain and pain of longer duration, lower pain thresholds, less tolerance for pain, and higher pain sensitivity than men.Reference Mogil 69 Research over the last two decades has therefore sought to understand why, and emerging information highlights multiple biological processes that seem to influence pain differently in females and males. The above discussion provides numerous examples of the biological pathways that can affect pain differently between the sexes. In particular, abundant evidence demonstrates that sex hormones exert substantial and complex effects on pain-related responses. Recent evidence has revealed important sex differences in the mechanisms whereby immune function mediates neuropathic and inflammatory pain, with glial activation being more important for males and T-cell activation more significant for females. In addition, numerous neural mediators and genetic factors have shown sex-specific associations with pain. In most instances, these represent qualitative sex differences, in which a given biological process influences pain differently in one sex than the other. Also, sex differences in pain-related brain structure and function have been reported by multiple investigators, though the findings vary considerably across studies. Finally, sex differences in response to opioids have been reported, but little is known regarding sex differences in the effects of other analgesic agents. Additional research will be needed before these findings can positively impact assessment and treatment of pain in women.

New Concepts in Sex Differences and Psychosocial Factors

Just as research over the last two decades on biological differences between men and women that might contribute to their pain experience has built upon earlier findings, recent studies have both confirmed and built upon earlier literature on psychosocial and cultural factors affecting pain experience in men and women. For example, several studies, a meta-analysis, and a large systematic review corroborate prior findings and conclusions regarding gender roles, i.e., that men who consider themselves more “masculine” tolerate more experimental pain than women and than men who self-identify as less masculine.Reference Alabas, Tashani, Tabasam and Johnson 70 Scientists propose that much of this may be due to sex-based differences in learned behavior that may begin early in childhood. Boys learn to express emotions that signal independence and hide emotional vulnerability, whereas girls are typically conditioned to express emotions that are positive and signal vulnerability.Reference Robinson, Gagnon, Dannecker, Brown, Jump and Price 71 While gender roles clearly play a role in pain responses, gender-typed behaviors are influenced by a complex array of both biological and social factors, including early hormonal events.Reference Hines 72 Interestingly, two studies and a large systematic literature review indicate that it may be possible to alter some of the observed sex differences in the perception of experimental pain by manipulating gender-role stereotypes.Reference Robinson, Gagnon, Riley and Price 73

Additional literature has also endorsed prior findings regarding sex-based differences in coping strategies. In their 2013 review, Bartley and Fillingim cite numerous studies concluding that men tend to use a smaller number of specific techniques, such as behavioral distraction (e.g., deep breathing and diversional conversation) and problem-solving tactics (i.e., developing a plan of action) to manage pain, whereas women use a broader range of techniques including social support, positive self-statements, enhancing emotion regulation, cognitive reinterpretation, and attending to pain cues.Reference Bartley and Fillingim 74 This is not to say that women have superior coping strategies that result in better outcomes, but that treatment strategies may need to consider and incorporate different coping methods for men and women. For example, in a lab-based study, women’s lower pain tolerance was mediated by the rumination component of catastrophizing, 75 (i.e., continuous thinking of the same sad/dark thoughts) but not by the magnification or helplessness components.Reference Sullivan, Thorn, Haythornthwaite, Keefe, Martin, Bradley and Lefebvre 76 In addition, a large systematic review examining studies of experimental pain found that women may cope better with laboratory pain when they attend to their pain or reinterpret pain sensations, while distraction may be more effective for men. 77 Based on these examples, a treatment strategy focused on reducing ruminating thoughts may be quite effective for women. Men, in contrast, may benefit more from a treatment strategy that focuses on distraction techniques.

One important component of coping strategies includes social support, and recent research has shown that social interactions affect the pain experience differently in men and women. In one study, compared to men, women reported reduced pain tolerance when they had the option of interacting with an empathic experimenter.Reference Jackson, Iezzi, Chen, Ebnet and Eglitis 78 Relatedly, another laboratory study found that women whose social networks consisted of more intimate and longer-lasting relationships and greater partner support showed greater pain sensitivity, while men showed distinct patterns in the opposite direction.Reference Vigil, Rowell, Chouteau, Chavez, Jaramillo, Neal and Waid 79 These laboratory findings suggest that social influences on pain may differ significantly for women and men.

An area that has received considerable attention in the last two decades that was not addressed in the prior review by Hoffmann and Tarzian is the extent to which mood and negative affect influence the perception and experience of pain differently in men and women. Mood disorders have been examined as potential contributors to sex differences in pain because they are strongly related to chronic pain in general, and because these disorders, including depression and anxiety, are more common in women than men.Reference IsHak, Wen, Naghdechi, Vanle, Dang, Knosp and Dascal 80 Although we focus on studies examining the influence of mood disorders on pain, research indicates that the relationship is bidirectional, i.e., chronic pain can precede mood disorders or negative affect and vice versa.Reference Bair, Robinson, Katon and Kroenke 81

A systematic review of studies assessing sex differences in laboratory pain perception concluded that depression has minimal impact on “some of the observed sex differences in experimental pain perceptions, while the role of anxiety is ambiguous.” 82 Studies of clinical populations, however, tell a different story. For example, a study of veterans showed that depression had a greater impact on the relationship between combat exposure and pain for women than it did for men.Reference Buttner, Godfrey, Floto, Pittman, Lindamer and Afari 83 In addition, Patel and colleagues demonstrated that patient-reported stress and anxiety were higher among females than males receiving care in an emergency department for painful conditions,Reference Patel, Biros, Moore and Miner 84 and Canales et al. showed that significantly more women than men with temporomandibular disorders had a diagnosis of depression.Reference Canales, Guarda-Nardini, Rizzatti-Barbosa, Conti and Manfredini 85 In a study seeking to identify factors associated with the excess risk of pain in older adults, women showed a greater risk of high-intensity pain than men. This was partially explained by their poorer mental health, particularly psychological distress, as well as lower physical activity, poorer physical function, and presence of comorbid health conditions.Reference García-Esquinas, Rodríguez-Sánchez, Ortolá, Lopez-Garcia, Caballero, Rodríguez-Mañas, Banegas and Rodríguez-Artalejo 86

In a study of those undergoing total knee arthroplasty, women reported higher preoperative emotional distress, however, preoperative anxiety and depression scores were better predictors of severe postoperative pain in men than in women.Reference Nandi, Schreiber, Martel, Cornelius, Campbell, Haythornthwaite and Smith 87 Overall, several studies suggest stronger linkage between emotional distress and chronic pain in women than men, but findings of acute clinical and laboratory-based pain are more variable. This likely reflects the contributions of other complex biopsychosocial factors that may differ substantially between experimental and acute and chronic clinical pain populations.

Another psychosocial factor that may contribute to sex differences is early life adversity (ELA), including physical or sexual abuse, experiences of trauma, parental neglect, and social stress. Evidence links ELA with multiple adverse health outcomes, including multiple chronic pain conditions.Reference Groenewald, Murray and Palermo 88 The higher frequency of ELA among females could contribute to sex differences in pain.Reference Brennenstuhl and Fuller-Thomson 89 Interestingly, some preclinical studies suggest that ELA may affect pain responses differently in females and males. For example, one study showed that early life stress produced hypersensitivity to painful stimuli in male but not female rats.Reference Prusator and Greenwood-Van Meerveld 90 Moreover, ELA could produce psychological consequences that influence pain, and these effects may differ in females and males.Reference Nishinaka, Kinoshita, Nakamoto and Tokuyama 91 One preclinical study found that ELA increased sensitivity to thermal and mechanical pain after nerve injury in both female and male mice; however, ELA only induced depression-like behaviors in female animals. 92 Thus, ELA is an important psychosocial factor that may contribute to chronic pain, however, additional research is needed to determine whether and how ELA may affect pain differently in females and males.

New Research Concepts Related to Psychosocial Factors

Two relatively new concepts related to psychosocial factors have emerged in the pain literature over the last two decades — sex-based differences in the interaction among biological, psychological, and social factors, as well as sex-based differences in “pain resiliency.”

Interaction Among Biological, Psychological, and Social Factors

The field of chronic pain has long recognized the biopsychosocial model of chronic pain in which pain is a result of the complex interactions among biological factors (e.g., genetics, immune function), psychological factors (e.g., emotions, coping skills), and social factors (e.g., social support, culture); however, there has been an increased effort among researchers over the last two decades to better understand the contribution of each, and in combination, to the pain experience. Recent evidence suggests various combinations of these factors, including sex, likely influence the experience and perception of painReference Hashmi and Davis 93 and that these combinations are different for women and men. For example, in both rodent and human studies, administration of arginine vasopressin — a hormone that significantly affects pain perception — blocked experimental pain through a specific internal analgesic system, but only after that system had been activated by stress, and only in males.Reference Mogil, Sorge, LaCroix-Fralish, Smith, Fortin, Sotocinal and Ritchie 94 The authors believe this study is the first to demonstrate analgesic efficacy that depends on the emotional state of the recipient. The results have widespread implications for understanding the effectiveness of drugs in both sexes, as well as the design of studies to test the effectiveness of drugs in people with different combinations of biopsychosocial states.

Meloto and others investigated whether sex and stress can modify the effect of different variations of the COMT gene, a gene previously shown to affect pain sensitivity.Reference Meloto, Bortsov, Bair, Helgeson, Ostrom, Smith and Dubner 95 After a minor motor vehicle collision, the high pain sensitivity COMT genotype was linked to greater pain severity in males with low stress, but not in high-stress males or in females (regardless of stress level). These findings led the authors to conclude that a true understanding of the effects of genetic variations on pain sensitivity can only be achieved by evaluating both sex and other biopsychosocial factors, such as stress. Among individuals with chronic spinal pain, Malfliet et al.Reference Malfliet, De Pauw, Kregel, Coppieters, Meeus, Roussel, Danneels, Cagnie and Nijs 96 found that different psychosocial characteristics were associated with brain structure in different brain regions in women and men. These findings suggest that sex and psychosocial factors may interact in their association with brain structure differently in men and women with chronic pain. The studies illustrate the complex interactions of biological and psychosocial factors with sex, and how significant they likely are in the individual experience of pain.

Resilience

Resilience is another overarching concept that has gained traction in the field of pain research over the last two decades. The concept originated in the field of child development in the 1970s with observations of children who thrived despite experiencing significant risk factors for poor outcomes.Reference Luthar, Cicchetti and Becker 97 Since then, it has evolved to refer to “the maintenance of positive adaptation by individuals despite experiences of significant adversity,” and has been applied to many disease states, including chronic pain. 98 In research, definitions of resilience vary widely, however, with some conceptualizing resilience based on outcomes (i.e., individuals who show better outcomes in the face of substantial challenges are resilient), while others define resilience based on internal resources or characteristics of the individual (e.g., individuals with high levels of optimism or psychological flexibility are resilient). Sturgeon and Zautra hypothesized that individuals considered “resilient” to pain are those who adopt more adaptive coping strategies; possess a greater belief that they can effectively control their pain (i.e. pain self-efficacy); possess greater emotional knowledge, thereby bolstering their own positive affect and reducing the control that pain has over their emotions; have an optimistic outlook on their lives; express a greater belief that their lives have meaning; and demonstrate a willingness to accept pain and its consequences.Reference Sturgeon and Zautra 99

While evidence from other fields demonstrates that stress-related resilience may differ importantly for females and males,Reference Hodes and Epperson 100 limited research has addressed sex differences in pain-related resilience. One recent study found that males with musculoskeletal pain showed higher levels of resilience than their female counterparts.Reference You, Wen and Jackson 101 Also, women with pelvic pain reported lower resilience than men, and greater resilience was associated with lower pain severity.Reference Giannantoni, Gubbiotti, Balzarro and Rubilotta 102 In a study where resilience was based on outcomes, a greater proportion of men than women were classified as resilient, defined as those who reported high pain intensity but low pain-related disability. The resilient group showed higher survival rates over the ensuing 10-year period compared to the vulnerable group.Reference Elliott, Burton and Hannaford 103 In contrast, in a study of treatment-seeking patients with chronic pain, women reported higher pain acceptance and life satisfaction than men, both measures of resilience.Reference Rovner, Sunnerhagen, Björkdahl, Gedle, Börsbo, Johansson and Gillanders 104

Self-efficacy is an important component of “resilience” as defined by Sturgeon and Zautra. The concept, as first proposed by psychologist Albert Bandura, refers to the belief that one can successfully perform a behavior to achieve a desirable goal.Reference Bandura 105 In their review of the literature, Miller and Newton contend that socialization, personal beliefs and cultural identities can differentially affect the development of pain-related self-efficacy in women and men.Reference Miller and Newton 106 In a study of laboratory-induced cold pain, men reported higher self-efficacy and had greater pain tolerance and lower pain ratings than women. Notably, the higher levels of self-efficacy influenced the sex differences in pain tolerance and pain ratings.Reference Jackson, Iezzi, Gunderson, Nagasaka and Fritch 107

Interestingly, resilience may be an important factor not only for the health and well-being of men and women with chronic pain, but also for the current and future health of their children. A study investigating the association between parental chronic pain and resilience factors in thousands of adolescent girls and boys found that when both parents had chronic pain, girls were more likely to have reduced self-esteem, social competence, and family cohesion compared to boys.Reference Kaasbøll, Ranøyen, Nilsen, Lydersen and Indredavik 108 Maternal chronic pain was associated with higher social competence in boys and reduced self-esteem in girls, suggesting a possible disparity between sexes. In addition to parental pain impacting psychosocial function of girls in their adolescence, one study suggests that daughters (but not sons) of those with chronic pain may be at increased risk of developing chronic pain in the future. Another study found that adolescents who had a parent with chronic pain reported greater pain, somatic symptoms, worse physical health, and reduced physical function. Daughters fared worse on some, but not all, domains, leading the authors to conclude that daughters of parents with chronic pain may have increased susceptibility to poorer outcomes relative to their male counterparts.Reference Wilson, Holley, Stone, Fales and Palermo 109

In sum, research in the last two decades on sex-based differences in psychosocial factors and pain has confirmed and extended what was previously known. Gender roles continue to be associated with sex differences in responses to laboratory-based pain, and sex differences in pain coping continue to emerge. Social influences, including the presence of others at the time of pain assessment, seem to differentially influence pain perception in females and males. Also, new research reveals that mood and affect may contribute to sex differences in both clinical and laboratory pain responses. Growing evidence implicates early life adversity as a potentially important risk factor for sex differences in pain, and resilience has become a topic of greater interest in the context of pain. However, much of the newer literature points toward important new directions for research, including a need for work addressing interactions between sex and other biological and psychosocial variables, as well as additional research exploring how potential sex differences in resilience may influence pain.

Chronic Pain Treatment over the Past Two Decades: The Context

Before reviewing the literature on sex-based disparities in pain treatment during the last twenty years, it is important to understand the context of chronic pain treatment during that time and the time leading up to it. In the 1980s and 90s there was a strong emphasis on the complexity and multidimensional causes of chronic pain, during which time multidisciplinary treatment approaches based on a biopsychosocial model enjoyed their heyday. This was especially true for work-based injuries. Unfortunately, lack of health insurance coverage for holistic care made this approach unfeasible and more emphasis was placed on pharmacology and procedures as primary management approaches. While opioids were available at the time, there was both a reluctance on the part of physicians to prescribe them for chronic pain patients and a reluctance of chronic pain patients to take them. Experts attributed this to, among other things, limited evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of these medications for treating chronic pain; fear by physicians of regulatory scrutiny if they prescribed opioids; patient beliefs that they needed to be brave in the face of pain; and concern by patients and their families of the potential for addiction.Reference Resnik, Rehm and Minard 110 As a result, with declining availability of multidisciplinary care, treatment options for chronic pain were limited, whether the patient was male or female. 111

In the mid-1990s, Oxycontin, an extended-release opioid, was approved by the FDA.Reference Van Zee 112 At the same time, opioid prescribing was expanded from cancer and acute pain patients to chronic pain patients.Reference Bernard, Chelminski, Ives and Ranapurwala 113 While some cautioned against the widespread use of opioids, others believed early reports by physician expertsReference Portenoy and Foley 114 and pharmaceutical manufacturers who stated or implied that rates of addiction were not significant. However, data were sparse, and rates of addiction turned out to be somewhat greater than initially reported.Reference Højsted and Sjøgren 115 In some cases, inappropriate prescribing to chronic pain patients may have led to overdoses and deaths, although many deaths were a result of polypharmacy. While some chronic pain patients succumbed to the drugs, overdose deaths were also a response to prescribing for acute pain such as post-surgical pain, including dental procedures.Reference McCauley, Hyer, Ramakrishnan, Leite, Melvin, Fillingim, Frick and Brady 116 These patients, who most likely needed only a few days of pain medication, were often given prescriptions for a 30-day supply. In some cases, non-patients were then able to obtain the drugs, which were left over from surgery and kept in medicine cabinets. In fact, misuse of the drugs was attributed more to an increase in their general availability than to misuse by those for whom they were initially prescribed.Reference Denisco, Chandler and Compton 117 In figures released by SAMHSA, only “about 20% of misusers report[ed] obtaining their prescription opioids from their own physician.” 118 Some individuals who developed an opioid use disorder and were unable to obtain pharmaceutical-grade opioids resorted to purchasing illegal narcotics, such as heroin, on the street. In recent years, these drugs have been laced with illicitly-produced fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, which is much more potent than heroin or morphine and can produce fatal respiratory effects in miniscule quantities.

In response to the opioid overdose crisis, in 2016 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued guidelines that suggested physicians limit their prescribing of opioids to 50-90 mg of morphine equivalent per day.Reference Dowell, Haegerich and Chou 119 Even though these guidelines were recommendations, not laws, physicians began to rapidly taper their patients off opioids or refuse to see patients taking opioids, practices which were inconsistent with the CDC’s intent.Reference Dowell, Haegerich and Chou 120 This was the case even though there are many patients for whom opioid medications are medically necessary and appropriate. The CDC policy and complementary state laws led to an 18-year low in opioid prescribing and has again resulted in significant undertreatment of pain for many men and women. 121 Although opioid prescribing is at an 18-year low, overdose deaths involving opioids are the highest they have ever been, indicating that the policies and laws on opioid prescribing have had unintended consequences for both those misusing/abusing opioids as well as chronic pain patients. 122

While the prescribing of opioids has decreased, over the last decade the prescription of certain antidepressants for chronic pain treatment “has increased, along with evidence of their effectiveness and mechanistic underpinnings.” 123 This practice may fuel a belief that physicians think a woman’s pain is “all in her head,” i.e., a psychological issue or attributable to anxiety or depression. Rather than signify that chronic pain is all in one’s head, however, prescribing of antidepressants for pain reflects the understanding by researchers and clinicians that the locus of some types of chronic pain is in the CNS, i.e., brain and spinal cord. Moreover, the neurochemical systems targeted by these drugs (e.g., serotonin, norepinephrine) are well known to contribute to pain perception. These medications have been shown to be highly effective for a wide range of chronic pain conditions in lower dosages than are necessary for the treatment of depression. In particular, tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline, have been shown to be effective in the treatment of headaches, neuropathic pain, sleep disorders and fibromyalgia. 124

Other efforts to reduce chronic pain that have gained broader attention since the recent restrictions on opioids include self-care and non-pharmacologic methods such as mindfulness and acceptance-based interventions as well as integrative health approaches. According to advocates, these options can help patients retrain their responsive thoughts, actions and emotions to their pain and find different ways to manage and live with it when it is mild to moderate. However, there is little efficacy data for these treatments in different pain populations.

Additionally, during the last two decades SNRIs (serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) such as duloxetine and milnacipran have been FDA-approved for the treatment of pain conditions, including fibromyalgia (both medications), diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain, and chronic musculoskeletal pain (duloxetine). Gabapentenoids (e.g., pregabalin) are another relatively new class of medication that has been approved for treatment of chronic pain conditions. Despite these advances, there is still evidence that many chronic pain patients are not being adequately treated for their pain. 125

Other efforts to reduce chronic pain that have gained broader attention since the recent restrictions on opioids include self-care and non-pharmacologic methods such as mindfulness and acceptance-based interventions as well as integrative health approaches. According to advocates, these options can help patients retrain their responsive thoughts, actions and emotions to their pain and find different ways to manage and live with it when it is mild to moderate. However, there is little efficacy data for these treatments in different pain populations. 126

Treatment of Women v. Men for Other Health Conditions

The study of sex-based disparities in treatment of pain also takes place in a larger context of sex-based differences in treatment for other health conditions. While an overview of the literature in this regard is beyond the scope of this paper, it is important that it be acknowledged. Less adequate treatment of women than men with the same conditions/symptoms has been reported for diabetes, cancer, coronary artery disease and other cardiac conditions, acute stroke, orthopedics, and peripheral arterial disease, among others.Reference Alspach 127 Studies have also found that women are less likely to be admitted to the ICU than men with the same diagnosis and comorbidities. 128 This literature signals a broader bias that can adversely impact the quality of healthcare provided to women relative to men.Reference Cleghorn 129

Do Treatment Disparities for Pain Continue to Exist?

Research over the last two decades largely confirms the earlier conclusions by Hoffmann and Tarzian regarding how men and women respond to pain and the biological and psychosocial bases for those differences. In this section, we explore whether studies over the last twenty years shed additional light on whether men and women are treated/diagnosed differently for their pain and in what ways.

Although anecdotal reports fuel assertions of disparities in pain treatment based on sex, a review of the literature published between 2001 and 2021 uncovered relatively few well designed and sufficiently powered studies that looked at whether women and men were treated or diagnosed differently for their pain. Several of the studies that have been done were conducted in Europe or Australia and, with one or two exceptions, are not included in this review because differences in physician education and health care systems do not permit generalizations across countries. Those conducted in the US can be categorized into three groups: those that focused on (i) differences in treatment/diagnosis between men and women for specific medical conditions that may be associated with pain but not necessarily chronic pain, e.g., pain associated with cardiac conditions; (ii) pain treatment in the pre-hospital and emergency department; and (iii) diagnosis/treatment of women for painful conditions that are unique to women. An example of the latter is a study conducted by Harlow and Stewart on women with chronic vulvar pain (published in 2003) which found that 40% remained undiagnosed after three medical consultations. Similarly, articles published in 2004 and 2009 found that 50% of women with endometriosis saw at least five HCPs before receiving a diagnosis and/or referral.Reference Ballweg 130 We were unable to find any comparable studies addressing how many times men with a chronic pain condition unique to men, e.g., chronic prostatitis, saw a physician before receiving an accurate diagnosis. 131

Treatment/Diagnostic Differences for Specific Conditions

Cardiac and Stroke Symptoms

A few studies have looked at sex-based treatment/diagnostic disparities for stroke and cardiac cases, both of which may present with pain.

In a study to assess missed strokes in the emergency department (ED), Newman-Toker and co-authors examined 187,188 records of stroke admissions with ED discharge within the prior 30 days from over 1,000 hospitals in nine states.Reference Newman-Toker, Moy, Valente, Coffey and Hines 132 The study is relevant to our research as the authors found that the two most common presenting symptoms for stroke misdiagnosis in the ED were dizziness and headache and that women were much more likely to be misdiagnosed than men. The authors suggested that when assessing patients for stroke, ED physicians should be more attentive to the symptoms of women, as well as younger and non-white patients. Further, they recommended that “[f]unding agencies should support studies to develop and refine revisit analyses as a means to measure the burden of misdiagnosis in the ED, along with systematic study of disparities in misdiagnosis based on sex, age, and race/ethnicity.” 133

In a study to assess misdiagnosis of cardiac cases, Maserejian et al., exposed 128 physicians to video vignettes of patients presenting with symptoms of coronary heart disease (CHD), including chest pain, and asked them for a diagnosis and their level of certainty about it.Reference Maserejian, Link, Lutfey, Marceau and McKinlay 134 Physicians were significantly less sure of their diagnosis of CHD for middle-aged women than for other groups and were more likely to have confidence in a diagnosis of a mental health condition for this group. This was true even though both men and women in the videos presented with identical symptoms of CHD.

Emergency Medical Treatment

One of the most common symptoms that bring patients to the ED is pain, making it a focus of a number of studies regarding pain treatment. Before patients get to the ED, however, they are often treated by paramedics and other emergency medical personnel. One study by Michael et al., looked at how these HCPs respond to patient complaints of pain by patient demographics including sex. This was a retrospective study of electronic medical records of a large emergency medical services agency.Reference Michael, Sporer and Youngblood 135 Approximately 1,000 cases were included in the analysis. The authors found that women were significantly more likely to receive less analgesia for isolated extremity injuries in the prehospital setting even when controlling for pain intensity and concluded that “[f]urther inquiry is needed to determine why certain populations such as women receive disproportionately less analgesia.” 136

In a prospective study of 981 adult patients who presented to the ED with abdominal pain, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania found that despite similar mean pain scores

women were less likely to receive any analgesia (60% v. 67%) … and less likely to receive opiates (45% v. 56%…). These differences persisted when gender-specific diagnoses were excluded (47% v. 56%…). After controlling for age, race, triage class, and pain score, women were still 13% to 25% less likely than men to receive opioid analgesia. There was no gender difference in the receipt of nonopioid analgesia. [In addition] women waited longer to receive their analgesia (median time 65 minutes vs. 49 minutes, …).Reference Chen, Shofer, Dean, Hollander, Baxt, Robey and Sease 137

The authors concluded that the results may be due to gender bias.

While these results are indicative of sex-based differences in treatment of patient pain in the ED, other studies have had different results. In a retrospective study of the ED records of 868 patients presenting with musculoskeletal pain, the researchers found that the only bases for disparities in the prescribing of analgesics were “physician characteristics and wide variation in practice,” not patient gender.Reference Heins, Heins, Grammas, Costello, Huang and Mishra 138 Similarly, in a multicenter study of 16 US and 3 Canadian EDs, Safdar et al. examined the influence of both provider and patient gender on analgesic administration to patients with moderate to severe pain treated over a 24-hour period.Reference Safdar, Heins, Homel, Miner, Neighbor, DeSandre and Todd 139 842 patients participated in the study. Baseline pain scores were similar for both sexes. Rates of analgesic administration “were not significantly different for female and male patients (63% v. 57%)” but female patients were slightly more likely to receive opioids than male patients. 140

Other Evidence of Differences in Treatment

A number of studies (both pre- and post-2000) indicate that HCPs are more likely to prescribe psychotropic medications to women than men when both present with the same symptoms. In two related studies published in 2013 and 2014, the authors used clinical pain vignettes and virtual patients to assess provider treatment preferences. The studies found that females were significantly more likely to receive recommendations for antidepressant and psychological treatment than males.Reference Hirsh, Hollingshead, Bair, Matthias, Wu and Kroenke 141 In both cases, male and female patients had similar symptoms and pain facial expressions.Reference Hirsh, Hollingshead, Matthias, Bair and Kroenke 142 In those same studies, men were more likely to be prescribed analgesics than women.Reference Denisco, Chandler and Compton 143 Also, in a study of patients on long-term opioids, a data analysis of two multi-state health plans revealed that significantly more women than men (33% v. 25%) were prescribed sedative-hypnotic drugs for 180 days or more.Reference Campbell, Weisner, LeResche, Ray, Saunders, Sullivan and Banta-Green 144

What Accounts for Differences in Treatment?

Implicit Bias

While it is unlikely that clinicians intentionally fail to adequately diagnose or treat women for their pain, differences in the way clinicians treat men and women for their pain could be due to implicit bias, i.e., unconscious bias that “operates outside of the person’s awareness and can be in direct contradiction to [their] espoused beliefs and values.” 145 According to the National Center for Cultural Competence, “[i]mplicit bias can interfere with clinical assessment, decision-making, and provider-patient relationships such that the health goals that the provider and patient are seeking are compromised.” 146

Although there have not been many studies of differences in treatment of pain patients based on their sex over the last 20 years, there have been studies looking at HCP implicit bias, more specifically, HCPs’ attitudes toward patients presenting with pain and their assessment of pain patients based on sex. A number of these studies used avatars or “virtual human” (VH) patients to assess factors that influence provider decision making. Others were based on questionnaires of HCPs that sought to assess “gender-related stereotypes of pain” that might account for sex-based differences in pain treatment.Reference Wesolowicz, Clark, Boissoneault and Robinson 147 For example, Wesolowicz asked 169 HCPs to complete a “Gender Role Expectations of Pain Questionnaire” and found that providers believed that men tend to underreport their pain compared to women. In an earlier study, Hirsh exposed 54 nurses to vignettes of VH patients after surgery. The virtual patients differed by sex, age, race, and facial expression. The nurses made assessments of patient pain and rendered treatment decisions and were then asked to indicate what information they relied on to make their decisions. None indicated that the patients’ demographic characteristics influenced their decisions when, in fact, “statistical modeling indicated that 28–54% used patient ‘demographic cues’ including sex.”Reference Hirsh, Jensen and Robinson 148 The authors stated that their findings suggested that “biases may be prominent in practitioner decision-making about pain, but that providers have minimal awareness of and/or a lack of willingness to acknowledge this bias.” 149

In a subsequent study using similar methods, medical trainees were asked to review vignettes of 16 VH patients with chronic low back pain who differed by race and sex and make treatment decisions including whether they would prescribe opioids, antidepressants, or physical therapy for the patient.Reference Hollingshead, Matthias, Bair and Hirsh 150 The trainees were also asked to indicate, from a list, factors that influenced their decision-making. Researchers found that “30% of participants were reliably influenced by patient sex and 15% by patient race when making their decisions.” The findings indicated that “there is considerable variability in the extent to which medical trainees are influenced by patient demographics and their awareness of these decision-making influences.” However, during follow up interviews, the study authors noted

some participants endorsed stereotypical beliefs about female patients, such as women have less occupational impairment due to pain and are more open to certain treatments (e.g., antidepressants, mental health counseling). These views fit with evidence that providers often attribute female patients’ pain to psychological factors, particularly when there is no observable pain pathology, and believe that women have higher pain tolerances than men. 151

Some of these attitudes may be learned by medical students during their medical education. According to Rice et al., there is evidence that medical school students’ attitudes toward chronic pain patients get progressively worse as they go through their medical education.Reference Rice, Ryu, Whitehead, Katz and Webster 152 In a study of medical students and residents in Toronto, the authors found trainees viewed chronic pain management as “challenging and unrewarding.” They based this perception, at least in part, on pain being subjective and difficult to measure. Further, they shared that “their inability to cure chronic pain left them confused about how to provide care and voiced a perception that [their] preceptors seemed to view these patients as having little educational value.” 153

In a study conducted in the UK, researchers looked at how HCPs’ assessment of patient trustworthiness affected their assessment of patient pain and of prescribing.Reference Schäfer, Prkachin, Kasewater, de and Williams 154 Pain physicians and medical students were shown a video of a pain patient and given a brief history of the patient’s pain. They were then asked to rate the patient’s pain, and “the likelihood that it was being exaggerated, minimized, or hidden” and to recommend treatment options. The authors found that overall HCP perception of patient trustworthiness had minimal or no effect on their pain estimates or judgments, but when perceptions of trustworthiness were broken down by sex, they found pervasive bias. Providers estimated that women, particularly those rated of low trustworthiness, had less pain than similarly rated males, and were thought to be more likely to exaggerate it. The study findings confirm earlier hypotheses that because pain is subjective, HCPs must rely on patient pain reports to assess pain and treat it, and with such subjectivity comes bias. 155

These studies indicate that HCPs, even early-stage practitioners, may have implicit biases when it comes to attitudes about treating pain patients generally as well as treating women with pain.

Gender Norms

In addition to gender bias, another possible explanation for different treatment of men and women for pain is “gender norms.” In a 2018 review article, Samulowitz et al.Reference Samulowitz, Gremyr, Eriksson and Hensing 156 asserted that the notion of “gender norms” leads to women’s needs being overlooked. According to this perspective, physicians view the male experience as normal and the female experience as atypical. This explains why we refer to women’s symptoms of myocardial infarction as atypical, because we view men’s as the norm. Men’s pain experience is also more likely to be related to something tangible and easier to treat. That, again, is seen as the norm. These authors make a distinction between gender bias and gender norms. You can have one without the other. Expectations that women will take care of the household and family is a norm; treatment advice that women should prioritize family above work and leisure time is a bias. Awareness of norms is important to avoid bias and to undertake more individualized care. 157

Other Explanations

Research Omission and Lack of Adequate Education

While implicit bias and gender norms may account for some differences in the way in which men and women are treated for their pain, there are several other reasons that may account for sex-based treatment disparities. In addition to the historical lack of research on female animals in preclinical studies of pain mechanisms and treatment, physicians receive very little training about pain management in general and even less for conditions that are more prevalent in women, such as fibromyalgia.Reference Leeds, Smmer, Andrasik, Atwa and Crawford 158 As early as the 1970s, pain treatment experts recommended that medical schools devote more time in the curriculum to teaching students about the treatment and management of pain, in particular chronic pain.Reference Loeser and Schatman 159 Then again, between 2005 and 2011, several professional associations, including the International Association for the Study of Pain and the Institute of Medicine, called for increased medical education about pain. Yet medical schools for the most part have not heeded this message. In a 2011 survey of medical schools, Mezei and Murinson found that 80% of American medical schools did not report any “formal pain education,” with many requiring five or fewer hours of such education. Elective courses were available in only 16% of schools.Reference Shipton, Bate, Garrick, Steketee, Shipton and Visser 160 In addition, the authors found there were no “official residencies” in pain management. As a result, they concluded that physicians “must rely on fellowships to obtain board-certification in pain medicine/pain management” and primary care physicians likely do not have the background to adequately treat complex chronic pain conditions. 161 A subsequent review of studies conducted between 1987 and 2018 found similar results and concluded that ”pain medicine education at medical schools internationally does not adequately respond to societal needs in terms of the prevalence and public health impact of inadequately managed pain.” 162 However, according to a 2019 publication by the Association of American Medical Colleges, 163 since the opioid epidemic, more medical schools report having incorporated course content into the curricula dealing with opioid prescribing and pain treatment.

Difficulty of Diagnosis

Many of the pain-related diseases/conditions that are common to women, such as fibromyalgia, vulvodynia, and chronic fatigue syndrome, must be diagnosed by exclusion; there is no definitive diagnostic test for them. In a 2014 article, Lobo and co-authors described the difficulty of diagnosing fibromyalgia, stating: “The diagnosis, management, and treatment of fibromyalgia is a challenge for both health care professionals and patients mainly due to an unknown etiology, symptom heterogeneity, symptom overlap, and a lack of objective diagnostic techniques. Very often, there is non-uniformity in symptom experience among patients.”Reference Lobo, Pfalzgraf, Giannetti and Kanyongo 164 The diagnosis of fibromyalgia is also confounded by the invisible nature of its symptoms. The normal appearance of patients without any physically noticeable symptoms results in physicians reporting disbelief in patients’ symptom experience. While chronic pain conditions that are unique to men may also be difficult to diagnose and must be diagnosed by exclusion, the fact that there are simply fewer chronic pain conditions that are exclusive to men makes the number of men who experience such difficulty obtaining an accurate diagnosis much lower than the number of women.

Another factor that may lead to difficulty in their diagnosis, is that female patients who complain of pain may have unusual symptoms. Lydia Haas, who wrote about how women in pain are often disbelieved by their physicians, refers to a “class of illnesses — multi-symptomatic, chronic, hard to diagnose — that remain associated with suffering women and disbelieving experts.” 165 The unusual symptoms may be explained by women who have several chronic pain conditions, not just one. A patient with COPCs, for example, may report symptoms ranging from jaw pain to bladder pain. A physician is likely to be stumped by the lack of common symptoms that describe well known diseases or conditions. Given the variation of a woman’s symptoms, she might be referred to specialists who may be able to diagnose some of her symptoms but not all of them. As a result, she may have to go to three or four specialists, who rarely coordinate her care.

Many of the painful conditions that plague women are also poorly understood, perhaps because historically biomedical research has been primarily conducted by and on men. Further, the federal and private investment into research on chronic pain disorders that solely or predominantly affect women has been, and remains, grossly incommensurate with their societal burden. 166 As a result, we know little about the causes, mechanisms of, and effective treatments for, these conditions. This deficiency in knowledge leaves physicians trying different things, many of which may not work. This can make them feel helpless.

Studies have found that physicians who don’t have an explanation or diagnosis for a patient’s problem are more likely to tell a patient “it’s all in your head” or, consistent with the “attractiveness is healthy” assumption more common in women,Reference LaChapelle, Lavoie, Higgins and Hadjistavropoulos 167 tell patients they don’t look ill, they look healthy. A 2009 study by Hartman found that physicians who are “unsure of a diagnosis … are likely to try one of three strategies with a patient: (i) normalize the symptoms; (ii) tell patients there is no disease; (iii) use metaphors to explain the symptoms.”Reference Balweg, Drury, Cowley, McCleary and Veasley 168 These difficult-to-diagnose conditions are often called “contested illnesses” because some medical experts dispute their existence. They include conditions such as “chronic fatigue syndrome, … fibromyalgia, multiple chemical sensitivities, and chronic Lyme disease.” 169

Ways in which Men and Women Communicate about their Pain

In their 2001 article, Hoffmann and Tarzian hypothesized that the tendency of HCPs to disbelieve women’s reports of pain could be due to the different ways in which men and women communicate with their physicians. 170 They pointed to publications by Vallerand and by Smith, the former arguing that women, who are often better able to verbalize their emotions than men, are viewed suspiciously and therefore treated less aggressively than men. The latter asserted that “women’s style of communication may simply not fit neatly into the traditional medical interview model adopted by most physicians.” These speculative theories have been confirmed by subsequent studies finding that women use more words and “graphic language than men, and typically focus on the sensory aspects of their pain event. Men use fewer words, less descriptive language, and focus on events and emotions.”Reference Strong, Mathews, Sussex, New, Hoey and Mitchell 171 A 2019 study found that women experiencing endometriosis use vivid metaphors to describe their pain.Reference Bullo and Hearn 172 Women have also been observed to use more facial expressions to indicate their pain than men. Interestingly, a study by Prkachin et al. demonstrated that greater exposure to pain-related facial expressions led physicians to “more conservative recommendations about [their] pain estimation.”Reference Prkachin, Mass and Mercer 173

Are Differences in Treatment Related to the Provider’s Sex?

Over the past two decades, the influence of the sex of the provider on treatment decisions based on patient sex has become a topic of interest given the increase in the number of women entering the medical profession over the last 25 years. In a 2015 article, Bartley and othersReference Bartley, Boissoneault, Vargovich, Wandner, Hirsh, Lok and Heft 174 asked 154 HCPs (physicians and dentists) to view a series of video vignettes of virtual humans of different age, sex, and race. They were asked to rate the VH patient’s pain intensity and pain “unpleasantness” as well as to indicate whether they would prescribe opioid or non-opioid analgesics for the patient. The study authors found that younger and middle-aged practitioners of both genders were more likely to rate female patients as experiencing greater pain unpleasantness than male patients. They further found that female practitioners were less likely than their male counterparts to recommend opioids for both male and female patients. Finally, the researchers found that younger practitioners were more likely than their more senior colleagues to prescribe opioid analgesics to female patients. The authors concluded that more research is needed to understand the root causes of these differences in order to develop interventions to address them.