This article studies the rise and fall of the first liability insurance cartel in the United States. In 1886, insurance companies in America began selling liability insurance for personal injury accidents, primarily to cover business tort liability for employee accidents at work and non-employee injuries occasioned by their business operations.Footnote 1 In 1896, the leading liability insurers agreed to fix premium rates and share information on policyholder losses. In 1906, this cartel fell apart.

Although largely forgotten until now, the rise and fall of this cartel confirms the expectations of both cartel theory and past studies of insurance cartels, largely in fire insurance, showing how insurers engaged in unstable price-fixing efforts and shared information to better estimate future claims costs.Footnote 2 Moreover, this liability insurance cartel offers a deviant case for standard accounts of how law and legal institutions influenced industrial organization in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century.

In standard accounts of industrial organization at this time, researchers largely emphasize how firms across industries moved from cartels to horizontal mergers as strategies to control price competition. The firms joining cartels were largely in relatively new capital-intensive mass-production industries that had been rapidly expanding on the eve of the Depression of 1893. Given their high fixed costs, those firms responded to the decline in demand by lowering prices, and then, to control the ensuing price competition, by forming cartels to fix prices or production levels. From 1895 to 1904, about twenty percent of industries experienced significant consolidation activity.Footnote 3 Some scholars explain this merger wave by pointing to legal factors. By 1895, the Sherman Act clearly prohibited cartel agreements, but did not clearly preclude consolidation through state-chartered corporations, whereas states could have, but largely did not, use their powers under state corporate law to restrict horizontal mergers.Footnote 4

For some, however, the standard accounts have largely ignored or suppressed substantial variation within and across industries along many dimensions of industrial organization, including cost structure, organizational form, and inter-firm cooperation.Footnote 5 For example, Berk concludes that standard accounts of American industrialization have mistaken a part for the whole, based on past research on custom, specialty, and batch industries; the persistence of non-corporate organizational forms in fire insurance and electricity; and the fact that “only 22 percent of U.S. industry participated in the great merger wave.”Footnote 6

Similarly, although the first liability insurance cartel does not challenge arguments about the influence of antitrust and corporate law on the merger wave, the story of its rise and fall raises the possibility that, in the eighty percent of industries that did not experience significant consolidation activity, possible legal influences on industrial organization may have substantially varied within and across industries in ways that standard accounts have not fully appreciated.Footnote 7

First, the first liability insurance cartel does not easily fit standard accounts of the legal influences on industrial organization. Insurance companies generally enjoyed immunity from federal antitrust regulation. From 1869 until June 1944, the United States Supreme Court consistently declared that Congress' power under Article I of the United States Constitution to “regulate Commerce . . . among the several States” did not cover insurance,Footnote 8 thereby arguably precluding action against insurance companies under the Sherman Act, which Congress had enacted pursuant to this power.Footnote 9 This shield from federal antitrust regulation (partly revived in 1945 by CongressFootnote 10) allocated regulatory authority over the insurance business in the States to state governments and state law, including state antitrust statutes, statutes that expressly barred some kinds of insurers from cooperative rate-setting, and state common law on unreasonable restraints of trade. Here, fire insurance and liability insurance diverge. Despite some lawsuits against fire insurance companies during this period,Footnote 11 no one appears to have sued any member of the first liability insurance cartel for violating any such state law.

Second, the distinctive structure of the liability insurance market suggests a distinctive possible legal influence: state solvency regulation of liability loss reserves. Unlike traditional industries with high fixed costs, sellers of insurance only know what their policies actually cost sometime after sale, when their policyholders suffer losses during the term of the policy and seek payment. If the odds or severity of the insured event vary significantly over time, those future costs may be both hard to estimate accurately and vary with changes in industry norms for how to estimate those future costs. If an insurer underestimates future claims costs and sells at a lower price on that basis, the insurer may not set aside enough capital in reserve to cover claims when they later arise and must be paid. Moreover, if this insurer insolvency risk remains positive and hard for buyers to observe at the time of sale, new firms may try to lure buyers with lower prices by setting aside less in reserve, and therefore bearing higher insolvency risk.Footnote 12

Faced with such price competition, insurers can conceivably adopt several strategies. They too can lower prices by setting aside less in reserve. They can, as part of product differentiation efforts, seek ways to credibly signal to buyers that they have lower insolvency risk than their rivals. They may share information with their rivals to more accurately estimate their future claims costs, and with that, their own insolvency risk, if they compete for the same pool of buyers and they believe that their future claims costs will be highly correlated with those of their rivals.Footnote 13 They may agree to fix prices as a way to jointly ameliorate price competition and secure monopoly profits. Or they may seek or support state regulation. For example, at the time State insurance codes typically required fire insurance companies to set aside fifty percent of gross annual premium income as an “unearned premium” reserve,Footnote 14 that is, capital designated and set aside in advance to cover any and all future claims on policies that may occur before those policies expire.

The rise and fall of the first liability insurance cartel raises the possibility that under certain conditions, insurance firms may be motivated to join price-fixing arrangements in part to credibly signal to buyers that because they are cartel members, they have lower insolvency risk than their non-cartel rivals.Footnote 15 If so, this suggests solvency regulation as a possible cause of the cartel's fall. By the 1890s, many states had statutes on the books to reduce insurance insolvency risk, both generally and for certain insurance lines, such as fire insurance. In this respect, however, state regulation of liability insurance differed from state regulation of fire insurance, because specific regulation of liability insurer loss reserves did not exist until 1901, and was limited until 1905. When such regulation began, it may have reduced the value of the cartel as a solvency signal, which thereby partly explains why the first liability insurance cartel fell apart shortly thereafter.

This article proceeds as follows. Part I describes the sources of cost uncertainty faced by the first liability insurers in the United States. Part II shows how, in 1896, the leading liability insurance companies formed the Conference of Liability Companies, and details the terms of their arrangement. Part III evaluates four possible complementary explanations for why this cartel abandoned its price-fixing effort in 1906: price competition from non-Conference rivals; defections by Conference members; state competition law; and state solvency regulation of liability insurance loss reserves. Of these, the article concludes that, given the available evidence, price competition from non-Conference rivals and state solvency regulation are plausible explanations, whereas state competition law is a less plausible one and the influence of Conference-member defections is unclear. The Conclusion identifies the limits of this article and suggests directions for future research.

I. Background: Pricing Liability Risk

This Part describes the uncertainties faced by the first liability insurers of personal injury accidents as they tried to set prices. It shows how they priced employers' liability insurance—a major type of liability insurance sold at the time—and how their uncertainty about future losses motivated both price competition and, for some insurers, efforts to signal buyers that they had less insolvency risk than their rivals.

The first liability insurer for personal injury accidents in the United States emerged in 1886, when George Endicott, a prominent fire and marine insurance broker in Boston, started the United States branch of the London-based Employers' Liability Assurance Corporation in a single room up one flight of stairs on State Street in Boston.Footnote 16 Other companies quickly joined the liability insurance business—on one account, fourteen companies had joined by early 1894.Footnote 17 Most of these early liability insurers were stock companies that sold multiple lines of insurance nationwide. For example, the Fidelity and Casualty Company, reportedly the first casualty company to sell multiple insurance lines,Footnote 18 was by 1895 selling liability insurance as well as accident, burglary, fidelity, plate glass, and steam boiler insurance.Footnote 19

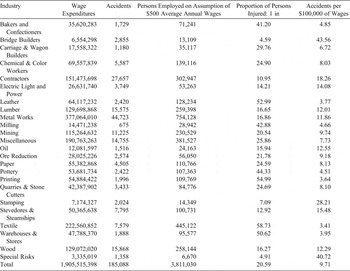

In pricing liability insurance, the first liability insurers faced the new and difficult task of accurately estimating policyholder liability risk. For a policy covering employer tort liability for workplace accidents, for example, insurers calculated the premium by multiplying an employer-provided estimate of the employer's payroll during the policy period with a premium rate, usually calculated in terms of $100 of payroll. With the payroll estimate, the insurer could calculate the liability insurance policyholder's accident risk by type of trade or industry,Footnote 20 much the way the Fidelity and Casualty Company did from 1889 to 1903 (Table 1).

Table 1. Fidelity and Casualty Company Liability Experience, 1889–1903, by Industry Type.

Source: “Employers-Liability Accidents,” Monthly Bulletin of the Fidelity and Casualty Company (Sept. 1906): 135. Columns 4–6 are author's calculations that slightly differ from calculations in the original.

The harder question was how to set the premium rate: the way to convert estimates of accident risk into estimates of liability risk. Initially, the first liability insurers based premium rates roughly on accident insurance premium rates, and then adjusted them on an ad hoc basis.Footnote 21 Indeed, some companies may have deliberately published inflated premium rates in their rate manuals to make it easier for insurance agents to “cut” those rates to increase sales.Footnote 22

Still, although these insurers also set aside an unearned premium reserve,Footnote 23 uncertainty arose from the fact that most liability losses tended to accrue several years after the policy had expired. The accident and its liability loss did not happen at the same time. Rather, for every covered accident, the liability insurer only knew its actual cost after settlement, final judgment, or when the statute of limitations expired. In hindsight, we can see the actual distribution of liability losses across the years after the policy year. Figure 1 reports the average five-year distribution of losses for liability insurance policies nationwide for four major liability insurance companies doing business in Michigan. It shows that, for these companies, most of the loss costs associated with a particular year's liability insurance business occurred in the year immediately after the policy year, and dropped significantly thereafter. Others looked back at the distribution of losses paid under liability insurance policies over a ten-year period, and found similar results.Footnote 24

Figure 1. Five-year distribution of liability losses paid as a fraction of liability premiums collected in the policy year. Source: Report of Employers' Liability Commission to the Governor of Iowa (Des Moines: Emory H. English, 1912), 109-13 (based on data filed with Michigan Insurance Department). The Fidelity and Casualty Company asserted that, unlike some other companies, it did not include claims expenses with paid losses. “Michigan Loss Ratios,” Monthly Bulletin of the Fidelity and Casualty Company (June 1905): 88.

Without the benefit of hindsight, some liability insurers set aside each year, in addition to their unearned premium reserve, a special reserve specifically to cover future liability losses. This signal of solvency had credibility problems, because it was difficult for insurance buyers to know whether that reserve was adequate. Rather than rely on companies' own published figures, the Spectator, an insurance trade publication, counseled its readers in 1895 to look closely at the insurer's reputation, and in particular, to whether the insurer is defending “an unusually large percentage of suits rather than settling them,” or is “appealing from an unusual percentage of verdicts.” If so, that would indicate an increase in the average cost of its suits and claims, and render “fictious” the insurer's allotted reserve for unsettled claims and suits.Footnote 25

Uncertain insolvency risk also resulted in price competition with rivals who took advantage of uncertain insolvency risk by setting aside less in reserve in order to sell their policies at lower prices. The older insurers often stressed that this practice–at the time called rate-cutting–increased insolvency risk. As Fidelity and Casualty's George Seward wrote to his agents in 1892, “It seems to be impossible for the newer companies to recognize the fact that there is a distant and contingent liability hanging over them. Because they don't meet their losses at once as in Fire Insurance, they seem to think that they will not occur. THE CONSEQUENCE IS THAT THEY SHOW A READINESS TO CUT RATES, WHICH IF PERSISTED, WILL LEAD THEM INTO BANKRUPTCY.”Footnote 26

By stressing rivals' rate-cutting, these insurers were engaged in a form of product differentiation by stressing their rivals' high insolvency risk and their lower insolvency risk. Thus, Seward reminded his insurance agents in 1901 to stress that the Fidelity and Casualty Company “is old in the business, well tried and of undoubted strength. In this way he will set forth the intrinsic value of the insurance offered by him, as against the lack of evidence of intrinsic value which can be offered by the rate-cutting agent.”Footnote 27 Yet, as the editors of the Spectator had put it in 1895, as the published statements of liability insurers “involve so much of the unknown,” the “average manufacturer or merchant may be well pardoned for mistaking the apparent for the real, and considering that he has done well in accepting the policy of the company which offers the lowest premium rather than that which offers the greatest protection.”Footnote 28

II. The Rise of the Liability Conference

In 1896, the major liability insurers agreed to fix prices and pool information on liability losses. This Part describes how they reached this agreement, its key terms, and how long it lasted.

On February 15, 1894, representatives of six leading liability insurers met at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City. Their goal: to set premium rates, that is, to fix prices.Footnote 29 By March, the group had agreed to adopt a uniform policy and set premium rates according to a “regular tariff.” The agreement later fell apart, because of a last-minute defection by A.W. Masters, of the London Guarantee and Accident Company.Footnote 30

In this first of several efforts to fix prices and pool liability loss data, the liability insurers were imitating the fire insurance business, which by the 1890s had allocated rate-setting authority to organizations of local fire insurance agents.Footnote 31 (American liability insurers may also have been aware of contemporaneous rate-setting efforts by accident insurance companies in England.Footnote 32) Among American liability insurers, Travelers Insurance Company President James G. Batterson, for one, urged rival liability insurance company managers also to adopt rate setting to solve the rate-cutting problem.Footnote 33 After a second attempt fell apart in 1895,Footnote 34 Batterson continued to do so.Footnote 35 Other justifications included the benefits of information pooling. As Fidelity and Casualty's George Seward recounted to an insurance journal publisher a few days after the second attempt began in 1895, the proposed information-pooling effort “was the most important . . . . The field is so new that some of the gentlemen who attended the conference can hardly be considered to ha[v]e knowledge enough of the loss ratio in different classifications to judge what premium they ought to secure.”Footnote 36 If the prospect of monopoly profits also motivated company managers, they did not mention this motive publicly.

In 1896, on the third attempt, they succeeded. By March, the major liability insurance companies had formed what later became known as the Conference of Liability Companies.Footnote 37 George Endicott was its first President.Footnote 38 The companies agreed to set premium rates, adopt standard policy forms, appoint an arbitrator to disputes among them, and establish “a bureau of statistics” authorized to “to call for tabulations of the experience of each company to collate same, and to prepare for consideration such proposals as to change rate as the circumstances may call for.”Footnote 39

In June 1896, the Conference's rules, regulations, and premium rate schedule went into effect.Footnote 40 By September, the Conference had adopted a standard form liability insurance policy for each of the various types of liability lines.Footnote 41 The Conference issued revised rate manuals several times thereafter, including October 1897,Footnote 42 October 1898, May 1901, and December 1904.Footnote 43 In its first manual, the Conference initially set liability premium rates based on the rates currently set by the Employers' Liability Assurance Corporation and the Fidelity and Casualty Company. The ultimate goal was to set premium rates based on an analysis, by the Conference's Bureau of Statistics and Arbitration, of the loss-experience data collected from all of the participating companies.Footnote 44 Stewart Marks, formerly of the Standard Life and Accident Insurance Company, had accepted the position as head of that Bureau: the Conference's chief actuary and its sole arbitrator, the final decider of disputes among members.Footnote 45

The participating companies also agreed to fix prices by not selling liability insurance policies at premium rates below those set by the Conference in the Conference's Liability Manual. Whereas commissions to agents and special agents were left to company discretion, no Conference member could authorize commissions to brokers exceeding fifteen percent generally, or exceeding ten percent for commissions on premium dollars in excess of $1,000. Moreover, no agent, special agent, or employee of a Conference company could “place any risk in any of the liability lines with any company not a party to the Conference agreement.” And rebates of commissions, or any other effort to “cut” a rate below the Manual rate, were prohibited.Footnote 46

The terms of the Conference Agreement would be enforced by its Bureau of Arbitration, in which the Agreement vested authority to

direct cancellation of any policy written in violation of this agreement; may order the company offending not to write the risk again for a period of one year; may direct the companies not to accept business from any broker who more than once violates the terms of this agreement, and may fine any company which permits any agent or employee to violate this agreement not more than $100 for each violation thereof. Such fines shall be used to defray the miscellaneous expenses of the bureau.Footnote 47

The Conference arbitrator would receive word of disputes from the companies, which would filter disputes brought to them by agents, and the arbitrator would be the final authority in deciding those disputes.Footnote 48

In contrast to rate-setting in fire insurance, in the structure of the Liability Conference, local associations of liability insurance agents took a subordinate role. By early May 1896, and at the urging of the Conference companies, insurance agents had set up local liability insurance associations in six cities—New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Chicago, and St. Louis.Footnote 49 The Baltimore association, for example, required its members to sign a pledge not to rebate or reduce premiums in violation of the Conference Agreement. Although the local associations provided input on liability premium rates,Footnote 50 unlike local fire insurance boards, the Conference itself retained the final authority to set rates.

The Conference lasted for about a decade, with members exiting the Conference during that time (Table 2).

Table 2. Liability Conference Membership, 1896–1906.

Sources: “Action By Liability Conference,” The Spectator, March 29, 1906,181; Weekly Underwriter, March 24, 1906, 217; “Liability Conference Takes Important Action,” The Standard, March 24, 1906, 289; “Employers' Withdraws From Liability Compact,” The Standard, October 28, 1904, 409; “Pleased to Have Maryland as an Ally,” The Standard, November 25, 1899, 500; “Maryland May Join Liability ‘Compact’,” The Standard, September 30, 1899, 316; “Liability Company Loses Detroit Company,” The Standard, November 21, 1902, 482; “Travelers Quits Liability Compact After All,” The Standard, October 6, 1900, 336; and “Harmonious Meeting of Liability Companies,” The Standard, February 29, 1896, 235.

aUnion Casualty and Surety transferred its liability business to the Maryland Casualty Company.

By December 1904, Fidelity and Casualty, one of the four remaining Conference companies, waxed fatalistic about the “demoralized” liability line,Footnote 51 telling its agents: “[I]t is no part of our purpose to participate in any effort to make a new conference that shall include the rate-cutters. … When the existing Conference goes to pieces, as it may, we are out of liability conferences for good and all.”Footnote 52 That month, the remaining Conference members agreed to maintain their rate agreement.Footnote 53 In 1905, the Liability Conference published its fourth manual,Footnote 54 and the remaining members of the Conference decided to continue.Footnote 55 Soon after, however, in March 1906, the Conference members voted to abandon the rule prohibiting competition among members.Footnote 56 Although two new companies would join the Conference later that summer,Footnote 57 the Conference was now purely an information-pooling arrangement. By January 1908, the Spectator reported that the Conference manual of liability premium rates “has become a dead letter, discredited and abandoned. All the companies are going alone, like a vessel where the master has discarded the compass.”Footnote 58

III. Explanations for the Fall

This Part evaluates four of the possible reasons why the Conference's cartel arrangement collapsed in 1906: (1) price competition from non-Conference rivals; (2) cheating by Conference members; (3) state competition law; and (4) state solvency regulation of liability loss reserves. The available evidence suggests that price competition by non-cartel rivals played an important role; the influence of defection by fellow cartel members is unclear; and state competition law appears not to have made much of a difference. The available evidence also is consistent with a fourth plausible cause: State solvency regulation of liability insurance loss reserves might have reduced the value of cartel membership as a signal of company solvency.

A. Price Competition from Non-Conference Firms

Price competition from rival non-Conference firms played an important role in the demise of the Liability Conference's price-fixing effort. As more firms entered the liability insurance market, the share of that market held by the Conference members began to fall and market concentration sharply declined (Figure 2). If market concentration implies market power to set prices,Footnote 59 this decline suggests that the Liability Conference's price-fixing effort became less successful over time.

Figure 2. Number of firms, Liability Conference market share, and industry concentration, 1895–1910. Sources: Annual data on liability premiums received by multi-line stock companies as reported in The Insurance Year Book 1901–1902. [Life, Casualty and Miscellaneous] (New York: Spectator Co., 1901), 325–32; The Insurance Year Book 1904–1905 [Life, Casualty and Miscellaneous] (New York: Spectator Co., 1904), 418–28; and The Insurance Year Book 1911–1912 [Life, Casualty and Miscellaneous] (New York: Spectator Co., 1911), A-260 to A-287. Mutual insurers selling liability insurance are not included in the underlying data. Exits from Conference (see Table 2) are coded by calendar year after the year in which exit occurred.

In accord with this conclusion, reports in the insurance trade press suggest that at least two Conference members left the Conference because of price competition from non-Conference firms. In November 1902, the Standard Life and Accident Company of Detroit withdrew from the Liability Conference.Footnote 60 Its President, W.C. Maybury, pointed out that at its inception, Conference members had written eighty percent of the business, and that percentage had since dropped to fifty percent.Footnote 61 Maybury also suggested that his company had left to escape the restrictions of the Conference agreement.Footnote 62 A few years later, in late 1904, the Employers' Liability Assurance Corporation also withdrew, citing its opposition to higher Conference manual rates scheduled for a month later, preferring instead a strategy of reducing expenses, particularly agent commissions.Footnote 63

Price competition from new firms destabilized the Conference's price-fixing efforts. To illustrate, consider how the Conference responded to the entry of the Maryland Casualty Company into the liability insurance market. Shortly after its inception in March 1898, the Maryland Casualty Company, based in Baltimore, had, according to one account, advertised that it was “not bound by compact rates,” that is, that it would offer liability insurance at rates below those in the Liability Conference Manual.Footnote 64 A few months later, in early May 1898, the Conference had invited Maryland Casualty, through its President, John Stone, to join the Conference.Footnote 65 Stone refused, pointing to a personality conflict with George Seward, now President of the Fidelity and Casualty Company.Footnote 66

In the summer of 1898, Maryland Casualty offered Travelers liability manager Edwin De Leon a position as its New York agent. De Leon asked Travelers President Batterson for his advice as a polite way to solicit a counter-offer. Batterson refused,Footnote 67 and De Leon soon left for Maryland Casualty.Footnote 68 Soon thereafter, Maryland Casualty started a price war. When De Leon had left Travelers, he had apparently taken “a complete list of [Travelers'] patrons” and was now “approaching them with cut rates.”Footnote 69

In mid-September, Batterson wrote separately to Conference President Endicott that, in response to the “vicious competition with which we are confronted,” the Conference companies “are all apparently asking for special rates on business which they cannot hold at Manual rates. Maybury asks consent to protect his Baltimore business against new comer who has stolen his agent. I am in precisely the same fix in New York. . . . . DeLeon will first go for the risks with which he is familiar, – ours; but he will not spare any Company's business which he can get. He is offering 20 per cent. commission where we have paid only fifteen.”Footnote 70 Batterson added: “I cannot wait for the Board to act. When the house is on fire, it is not wise to call a town meeting to see what is best to do about it.”Footnote 71

Batterson soon proposed that the Conference abandon “the rate book for competition purposes and leave each Company to protect its own business in any way it sees fit. In fact we cannot do otherwise and hold our agents.”Footnote 72 He favored continued cooperation “for the sake of combining the experience of the associated Companies in order to determine the pure premium on classified risks. We can work together as against a common enemy and treat each other fairly: but let each Company manage its own business in its own way.”Footnote 73

Unwilling to wait for a Conference meeting on the issue, Batterson took unilateral action. As he told an agent in Louisville, the Maryland Casualty Company and another non-Conference company, the Frankfort Marine, Accident and Plate Glass Insurance Company, “are on the war path . . . . I have determined for this Company that we will meet their rates if necessary to save our desirable risks. . . . [L]ook to your renewals a full month or two before they mature or you will be caught napping.”Footnote 74

In the first week of October 1898, the Conference temporarily suspended its rules and rates pending a meeting on the issue for the following week.Footnote 75 Conference President Endicott favored dissolution, whereas Seward supported maintaining the Conference rate agreement.Footnote 76 When the Conference finally met, in New York, on October 12, W.T. Dana, the representative of Employers' Liability Assurance Corporation, issued that company's resignation, and then withdrew it, and the story that emerged in the insurance trade press was that of Conference members holding firm.Footnote 77

Yet, less than two weeks after the October 12 meeting, Conference actuary Stewart Marks sent a notice to agents in New York that reminded them of the Conference limit of fifteen-percent commissions and reaffirmed the Conference's authority to take disciplinary action for violation of that rule.Footnote 78 The unstated target of Marks' notice was apparently the Travelers. Seward, at least, had complained that Travelers had been paying twenty-percent commissions in violation of Conference rules.Footnote 79

By early December 1898, George Endicott was dead,Footnote 80 and a few weeks later, the Conference members elected George Seward to succeed Endicott as Conference president.Footnote 81 About nine months later, however, in October 1899, the Liability Conference was negotiating with the Maryland Casualty Company over the terms of its joining the Liability Conference.Footnote 82 This was not easy. Because of Maryland Casualty's price war with the Conference members in the prior year, some Conference members appear to have been reluctant to take the company inside. In a letter to A.W. Masters, general manager of London Guarantee and Accident, Travelers President Batterson referred to George Seward's idea that Maryland Casualty President John Stone “‘ought not to be admitted until he begins to feels the pressure of losses.’” Batterson found this suggestion impractical, because that time was “indefinite and unknown.”Footnote 83

The next day, Batterson wrote to mollify Seward: “We all feel alike in regard to the onslaughts made upon our business by the Maryland; but it has now become a matter of business and not a question of retaliation or sentiment.” He added: “Now my esteemed Chairman I want to say that I admire your fighting qualities, and the way you put your fist down sometimes leads me to an earnest prayer for our enemies, but I cannot agree with you that we are justified either in delay, or going back of the date when we opened negotiations by Committee for reasons to sustain that position.”Footnote 84

A week earlier, Batterson, who apparently had been charged to deal with Maryland Casualty about Conference membership, had written to Maryland Casualty President Stone and given him four reasons for joining Conference. First, “a considerable bulk” of Maryland's business had been drawn from the Conference companies “by reduced rates or otherwise” that were “below the line of safety, and must be unprofitable if continued.” Second, a threat: some of the Conference companies had a “strong disposition . . . to regain” the business they had lost to the Maryland “regardless of the question of profit or loss.” Third, joining the Conference meant that the Maryland's liability policies could be renewed at the increased manual rates, not the lower rates at which they were originally obtained. Finally, the Maryland would benefit from loss-data pooling without paying a proportionate share of past expenses and without contributing the same volume of loss experience as other Conference companies.Footnote 85 Batterson urged Stone to move quickly, writing a few days later that “[e]very day's delay may bring up some new complications at points where agents are more anxious to get business than to preserve harmony among the Companies.”Footnote 86

Batterson did not mention that absent price competition by a non-Conference company such as Maryland Casualty, it would become easier to preserve the price-fixing features of the Conference Agreement. As Batterson wrote to Seward a few days later: “I am afraid we will not be able to ‘set our own house in order’ until The Maryland is in the Conference, for so long as that Company is ‘outside,’ it will be impossible to control the business ‘inside.’”Footnote 87 Indeed, Batterson assumed that Stone “knows as well as we do that Conference agreements as to brokerages are being broken right along, and that we cannot easily control that so long as he is outside.”Footnote 88 By early November, the Maryland Casualty Company had been persuaded inside.Footnote 89 Thereafter, no other company joined the Conference before it abandoned price-fixing in 1906.

B. Defections

Just as price competition came from non-Conference rivals, it may have also come from fellow Conference members who had covertly defected from the Conference agreement on prices and commissions. Cartel theory emphasizes that cartel members have the incentive to defect, because prices are fixed above the competitive level. Theory also suggests that, when two sellers agree on a price, if either seller can quickly observe the other's defection and respond by “punishing” the first seller by engaging in full-blown price competition, the threat of such punishment may deter defection in the first place.Footnote 90 I have no direct evidence of cheating by Conference companies, in part because the Conference practice of special rating makes it hard to prove such cheating, absent data on the actual premium rates on policies sold by each Conference company.

Under the Conference special-rating procedure, the Conference could sanction the sale of a Conference company policy at a “special rate”: a Conference-approved rate below the manual rate for a particular buyer when such a rate was ostensibly needed to prevent a buyer from purchasing liability insurance from a non-Conference company.Footnote 91 Applications for special rates, although initiated by local agents, had to come to the Conference from the home office of the Conference company member, not from the agent directly.Footnote 92 Non-Conference rivals scorned special-rating. In 1904, Aetna Life—a non-Conference liability insurer—reported to its agents that a “large percentage” of Liability Conference policies “are specially rated far below their regular Manual, such special rates being in fact,–when approved by their bureau,–Conference rates.” Aetna added that a non-Conference company engaged in the “selfsame procedure . . . is styled ‘rate cutting.’ Surely this is a distinction without a difference . . . .”Footnote 93

We do know that Travelers President Batterson complained that the Conference companies used special rating to protect themselves from competition by other Conference companies. For example, he wrote to Conference arbitrator Marks in 1898 that “[v]ery few of the special ratings so far seem to be called for by outside competition, or by a conviction that the rate is excessive. No one can deliberately look over the list of these cases without being convinced that the effect, if not the purpose, is to protect the risk from competition by Conference companies. . . . [T]he business is being rapidly tied up by special rates and we will soon have to consult the acts of the Special Rating Committee rather than the Manual. One special rate of necessity leads to another, because all in the same business will demand it.”Footnote 94 A few years later, in April 1900, Batterson complained: “To keep watch of the special rates applied for, ascertain (if possible) whether the application is justified by the rules and if not to file a protest, consume not a little time every day.” It was particularly hard when “the rate is all right in the application, but the cut is covered up by a rider.”Footnote 95 Other Conference company managers may have shared this view.

Moreover, Conference company managers may also have been resigned to partial fealty from insurance agents working for Conference companies, who tended not to want to lose any sale, and the accompanying commission, to a fellow Conference member. As case studies in other industries have suggested, rivalry among brokers or independent sales agents may be an important source of the instability of price-fixing agreements, or at least a way that company managers can explain indications of defection from such agreements in way that enabled continued cooperation among them.Footnote 96 Traveler's Batterson pointed to this difficulty for the Conference agreement: “[T]he ordinary agent considers it a mark of genius to steal a risk from an associate Company. . . Almost every mail brings advice of some risk lost to an associate Company by means forbidden. “The agent made it to our advantage” is about as near as we can get to particulars.” Batterson, however, also blamed the companies. Although a company could “cure this by refusing to take the risk or to pay the commission on stolen business,” the agent “wants business, and will work his territory against all comers; he will rebate to the extent of his full commission to get a risk on his books, and then will urge the payment of illegitimate claims to keep it the next year. We all believe this to be true, but submit rather than be disagreeable about it, and have a row with our agent.”Footnote 97

C. State Anti-Trust

In theory, Liability Conference members risked liability under state antitrust or competition law, because of the Conference's agreement on premium rates and commissions. There appears, however, to be no reported instance of legal action against a Conference company for violating state antitrust or competition law because it participated in the Conference. Moreover, there is only weak evidence that such laws caused the Conference companies to stop selling liability insurance in particular states, or affected how long those companies stayed in the Conference.

In public, the Liability Conference responded to antitrust concerns by imitating fire insurers, who had argued that classic antitrust concerns about price fixing did not apply to them, because the insurance market had low barriers to entry and needed rate setting to reduce the insolvency risk borne of rate cutting.Footnote 98 In 1897, Richard Loper, the general manager of The Guarantor's Liability Indemnity Company, and not a Conference member, charged that the Liability Conference's rate-setting activities made it a trust.Footnote 99 Conference President George Seward responded by stressing that the Conference had formed to avoid “ruinous” competition, not to “drive any competitor out of the field.” He added: “And might not such combinations be styled ‘combinations to maintain solvent conditions’ instead of ‘combinations in restraint of trade?’”Footnote 100

In private, Travelers President Batterson, for one, worried about state antitrust law. In October 1897, Batterson had complained to Conference arbitrator Marks about agents who had discussed with policyholders the substance of Conference agreement disputes, “This has been done in numerous cases, and in a way which gives direct evidence of a combination to fix prices for rates for insurance held, which has been held by Courts in some states to be unlawful.” If the Conference could not stop agents from discussing complaints to policyholders, then “we are all at sea and the result will be disasterous [sic].”Footnote 101

The available evidence, however, does not clearly show that any worry about state competition law caused a Liability Conference company to stop selling liability insurance in any particular state. Although most states enacted antitrust statutes from 1889 through 1914, only a few states enacted antitrust statutes that expressly referred to insurance.Footnote 102 Moreover, from 1896 through March 1906—the tenure of the Liability Conference—state antitrust statutes in only Kansas (1889) and Nebraska (1897) expressly covered more than fire or property insurance,Footnote 103 and courts in only Iowa (1897) and Mississippi (1897) declared that insurance fell within the ambit of other words in their state antitrust statutes.Footnote 104 Although a few state courts opined to the contrary,Footnote 105 in most states, the courts did not publish opinions concerning whether their state's antitrust statute covered insurance. State courts in Indiana (1884) and Illinois (1905), however, had opined that a combination to fix fire insurance rates amounted to a restraint of trade that violated state common law.Footnote 106 Moreover, although state legislatures, largely in the Midwest and the South, also enacted so-called anti-compact statutes that specifically banned cooperative rate setting for insurance policies, at least up through 1910, most of these laws covered only fire insurance or fire insurance companies.Footnote 107 Only the statutes in Georgia (1891) and Alabama (1897) were not limited on paper to any particular kind of insurance or insurance company.Footnote 108

Of the states just identified, five experienced legislative or judicial action during the Conference's tenure that arguably raised the odds that the Conference agreement would be found to violate that state's law: Alabama (1897); Iowa (1897); Nebraska (1897); Mississippi (1897); and Illinois (1905). If a Conference firm worried enough about a state's legislative or judicial action in that year, we should expect that firm to stop receiving liability insurance premiums in that state soon thereafter—a proxy for liability insurance sales—but not stop selling other types of insurance it had been selling there.

Although there are limited available state-level data on liability insurance premiums, those data do not indicate significant movement out of Alabama, Iowa, and Nebraska in a three-year period after 1897 (Table 3). Unfortunately, the relevant data for Mississippi are missing. Any causal inference concerning the 1905 Illinois appellate court decision is complicated by the close proximity of this decision to the Conference's end in 1906.Footnote 109

Table 3. Number of Liability Conference Firms Collecting Liability Premiums in Selected States, 1897–1900.

Sources: The Insurance Year Book 1901–1902 [Life and Miscellaneous] (New York: Spectator Co., 1901), 421, 427, 435; The Insurance Year Book 1900–1901 [Life and Miscellaneous] (New York: Spectator Co., 1900), 391, 396, 403; The Insurance Year Book 1899–1900 [Life and Miscellaneous] (New York: Spectator Co., 1899), 363, 368–69, 375; and The Insurance Year Book 1898–9 [Life and Miscellaneous] (New York: Spectator Co., 1898), 335, 344.

Notes: “—” indicates missing data. Maryland Casualty Company is not treated as a Conference member until 1900.

aNot counted is the Standard Life and Accident Company, which received accident insurance premiums, received zero liability premiums, and incurred liability losses.

bStandard Life and Accident Insurance Company resumed collecting liability premiums, whereas the Fidelity and Casualty Company received some accident insurance premiums and zero liability premiums.

Moreover, in September 1899, the Union Casualty and Surety Company—a Liability Conference member at the time—announced that it had agreed to transfer the liabilities of all its unexpired liability insurance policies to a non-Conference rival, the Maryland Casualty Company, along with its reinsurance reserve on those unexpired policies.Footnote 110 Although reported in some newspapers as simply a notable business deal, at least one newspaper, the St. Louis Republic, reported that Union Casualty had initiated talks with Maryland Casualty in July 1899, because Union Casualty feared that the Missouri attorney general would sue it for participating in the Liability Conference.Footnote 111 (As a Missouri corporation, Union Casualty could not avoid a lawsuit by the Missouri attorney general simply by not selling liability insurance business in that state.) I have no primary evidence to corroborate this assertion.

Finally, state antitrust laws seem more plausible as a pretext for Travelers' exit from the Liability Conference. In April 1899, as state antitrust legislation and lawsuits proceeded against fire insurance companies in Missouri and Arkansas,Footnote 112 Travelers President Batterson wrote to Conference President Seward: “I believe . . . that the Missouri and the other like laws will be sprung upon us, and if fought out in the courts we will be beaten sure.” He announced that Travelers “decides to withdraw from the Conference so far as rates are concerned, and remain for the purpose of comparing and combining experience.” He complained that the Conference companies “have the credit for” liability insurance premium rates, even though non-Conference companies really controlled rates through their rate-cutting. Accordingly, he argued, the Conference companies would be better off just pooling their loss-experience data “as we can under any other system which it is so strongly made the subject of adverse legislation.”Footnote 113

Despite this declaration, Travelers did not exit the Conference. It remained inside for over a year more. In January 1900, Batterson declared that because of the Conference practice of special rates, Travelers' “present intention” was to leave the Liability Conference at its next meeting.Footnote 114 Around this time, Batterson was also frustrated with Travelers' liability business.Footnote 115 A few days later, at the February 27 Conference meeting in Hartford, the Conference apparently took up the matter of special-rating abuseFootnote 116 and, according to the Standard, voted that it would no longer require Conference members to abide by manual rates. The Conference's Bureau of Arbitration and Statistics would, therefore, be renamed the Bureau of Statistics, and Stewart Marks, formerly the Conference arbitrator, now had the title of actuary. The main reason for this change, reported the Standard, was “the embarrassment experienced by some companies in states which have anti-trust laws.”Footnote 117

Although what happened in that meeting is unclear, the Conference agreement apparently retained some price-fixing features, because by April, Batterson was again giving notice of Travelers' “immediate withdrawal” from the Conference, again because of the special rating system.Footnote 118 When Conference President Seward tried to pressure Batterson to stay in the Conference, in part on the ground that the Conference had tried to accommodate Travelers' concerns at the February 27 meeting, Batterson would have none of it: “That the original agreement ‘was abandoned mainly out of regard for our difficulties’ is news to me. My recollection is that the agreement was abandoned for legal reasons which affected all alike.”Footnote 119

By August, however, Batterson still had not “confirmed our resignation from the Conference for fear of its effect upon our own agents, who would immediately make demands that we could not grant.”Footnote 120 Another reason for the delay was that at the time, Michigan Insurance Commissioner H.H. Stevens was auditing Travelers' liability insurance business; accordingly, Batterson told Seward to put “further action about Conference matters” on hold, and promised not to “withdraw the rate books from our agents.”Footnote 121

Several weeks later, Batterson publicly criticized Commissioner Stevens, who after completing his audit, billed Travelers what Batterson considered to be an exorbitant amount for expenses and, when Travelers refused to pay, allegedly threatened Travelers' business in Michigan.Footnote 122 A few days later, George Seward wrote to the Journal of Commerce and Commercial Bulletin, which had similarly criticized Commissioner Stevens, to defend Stevens' reputation and, in so doing, suggested that Batterson had the discretion of a “bull in a china shop” and had “Irish blood in his veins.”Footnote 123 In a letter to the Journal, Batterson replied to Seward's comments.Footnote 124 That same day, Batterson wrote a letter to Conference Actuary Marks in which he “confirm[ed]” Travelers' withdrawal from the Conference.Footnote 125 Hearing of this news, Seward privately celebrated: “We are all to be congratulated . . . on having at last the Travelers on the outside, their uncertain attitude having long been a cause of embarrassment.”Footnote 126

When Batterson died less than a year later,Footnote 127 Sylvester Dunham became Travelers' president. Among the congratulatory letters, Dunham received one from Maryland Casualty President John Stone, who observed that he had “always thought” that Batterson's exit from the Conference had been “largely influenced by personal feeling toward one of the Conference members,” an apparent reference to Seward. And then, Stone invited Dunham to have Travelers return to the Conference. Dunham quickly wrote back to refuse: “I can imagine a conference of liability companies, conducted in such a way as to be extremely useful to all its members, and I am by no means hopeless that at some time in the future such an organization will exist and be participated in by the officers of this Company with dignity and self respect.”Footnote 128 For Dunham, it seems, the Liability Conference was no longer useful to Travelers' liability insurance business. Dunham did not mention state antitrust law.

D. Liability Loss Reserve Regulation

This section develops the idea that state regulation of liability loss reserves partly explains the Conference's fall, because Conference companies had valued Conference membership in part as a credible signal to buyers that those companies had lower insolvency risk than their non-Conference rivals.Footnote 129 To make this signal credible, Conference companies had to show that Conference manual rates reflected better estimates of liability risk, as a result of Conference information pooling. When Michigan became the first state to regulate liability insurers' loss reserves in 1901, the Conference faced a competing signal of insolvency risk, and the Conference became more interested in securing more favorable liability loss reserve regulation. Several key states enacted such regulation in 1905, and the Conference officially abandoned price fixing less than a year later. Causal inference here is complicated, because Conference members might have substantially varied in how much they valued Conference membership as a solvency signal, particularly as compared to other reasons they had for joining the Conference. Still, the available evidence is consistent enough with this causal story to warrant further research.

1. Conference Membership as Solvency Signal

Since the Liability Conference's inception, the Conference companies appear to have stressed the connection between Conference membership and lower insolvency risk. As C.P. Ellerbe, then ex-president of the Union Casualty and Surety Company, wrote in a letter to George Seward in late September 1899, “I am more convinced the Liability Conference ought to be maintained, even if the agreement as to rates is not always well kept. For nearly four years the agents have been preaching the solvency of the Compact Companies and the insolvency of non-Compact Companies. To terminate the Conference now would be to place the Conference Companies in an awkward position.”Footnote 130

Accordingly, when the Liability Conference issued its third rate manual in May 1901, the Conference companies touted it as the product of careful calculations based primarily on Conference members' pooled loss-experience.Footnote 131 Indeed, a few months earlier, George Seward's Fidelity and Casualty Company had boasted in the company's monthly bulletin that this manual would be “a work which will hereafter be, to intelligent liability underwriters, what the mortuary tables are to life underwriters.”Footnote 132 A month later, an item in the company bulletin stressed that the Fidelity and Casualty's contribution to the “expense of tabulating experience, including the cost at the home office and its share of conference expenses, may reach the large sum of $100,000.”Footnote 133 When the manual was finally published, the Standard observed that the Conference companies stressed how the Conference had used “scientific principles” in writing the manual.Footnote 134

Buyers could perceive such claims as credible, in part because the Conference adopted in the 1901 manual a credible method for calculating liability premium rates developed by the aptly-named Frank E. Law, of the Fidelity and Casualty Company.Footnote 135 A mechanical engineer by schooling,Footnote 136 Law discovered that, even after collecting loss-experience data from all the Liability Conference members, there were still not enough data to produce separate liability-risk-sensitive premium rates for the thousands of industry-specific risk classifications on a state-by-state basis, even though liability risk varied with the law of each state.Footnote 137

To solve this problem, Law aggregated loss data for all the states, and, on that basis, fixed a base premium rate for each of many industry-specific risk classifications. This rate included a markup for administrative expenses and profit. Then, he derived a “counter-differential” for each state—a number that one could use to adjust the base premium rate for any risk-classification.Footnote 138 For employers' liability insurance, a state's counter-differential, in theory, represented the combination of two components of employer liability risk unique to each state: (1) physical hazard, “exposure to danger to doing work, in methods of doing work, in kind of machinery used, in precautions taken against the occurrence of accidents, and in character and intelligence of employees”; and (2) legal hazard,“the laws and judicial decisions and the attitude of the community, courts, and juries toward the question of the relations between master and man.”Footnote 139

Table 4 sets forth the counter-differentials for each state for 1908. Using these differentials was simple. For example, if the premium rate for machine shops for the country as a whole was $0.45 per $100 of payroll, then the machine-shops rate for Texas is that rate ($0.45) multiplied by the Texas differential (2), or $0.90 per $100 of payroll. After 1901, Conference manuals contained a table of state counter-differentials for certain risk classifications.Footnote 140 Each state counter-differential rested on the premise that future liability exposure would track past experience, and that therefore the actuary had to raise or lower that counter-differential manually to reflect recent changes in state law that would not yet be reflected in the Conference's pooled loss data.Footnote 141 Still, Law's method provided Conference companies with arguably better estimates of liability risk. Just as important, his method made credible the efforts to persuade buyers that a Conference company's liability policy carried less insolvency risk, albeit only if buyers also believed that the company usually sold that policy according to the Conference manual premium rate.

Table 4. State Counter-Differentials for Employers' Liability

Source: Frank E. Law, A Method of Deducing Liability Rates (New York: Spectator Co., 1908) (chart 2).

2. Liability Loss Reserve Regulation as a Competing Solvency Signal

If Conference companies valued Conference membership as a solvency signal, we should expect that they would value that signal less as states began regulating liability loss reserves, because company compliance with such regulation provided a competing signal of company solvency. Although companies selling liability insurance had been subject to general minimum capital requirements,Footnote 142 by the 1890s, only a few states had enacted special deposit requirements for liability insurers,Footnote 143 and no state had set minimums for liability loss reserves.

Although the early liability insurers resisted these deposit requirements, they appear to have had little success. For example, in 1894, Travelers had joined with Fidelity and Casualty, Union Casualty and Surety, and the Standard Life and Accident Company of Detroit to thwart passage of Ohio legislation requiring out-of-state liability insurers to make a $50,000 deposit to do business in the state.Footnote 144 In public, insurer objections to the then-proposed legislation included that it discriminated against out-of-state insurers, and that it was prohibitively expensive, particularly if other states adopted the same policy.Footnote 145 Privately, the insurers feared that other states would follow Ohio's lead, and then, as Batterson put it to Seward, “we will none of us have money enough to make the circuit.”Footnote 146 And they strongly suspected that the statute was a protectionist measure to aid Ohio's in-state insurance companies.Footnote 147

When their efforts failed, and the bill became law, the liability insurers went to court. On March 12, 1895, the Fidelity and Casualty Company filed a petition in Circuit Court, Franklin County, against the Ohio superintendent of insurance, arguing that Ohio's 1894 deposit requirement violated provisions of the Ohio State Constitution.Footnote 148 Although Fidelity and Casualty was the only nominal plaintiff, the litigation in Fidelity & Casualty Co. v. Hahn was, like the failed lobbying effort, coordinated with Travelers, Standard Life and Accident, and Union Casualty and Surety. Those insurers had waited until early 1895, when their licenses to do business in Ohio were set to expire,Footnote 149 and then demanded unconditional licenses, the denial of which would set up the lawsuit challenging the 1894 statute.Footnote 150

The liability insurers' lawyers, however, had limited options. Although the 1894 statute treated out-of-state insurers worse than Ohio insurers, a federal constitutional challenge would be unlikely to succeed. It was settled that corporations did not count as “Citizens” under Article IV's Privileges and Immunities Clause.Footnote 151 The United States Supreme Court had confirmed only a few months earlier that the insurance business still fell outside of Congress' Article I power to regulate “Commerce” among the several states.Footnote 152 Nor would the insurers fare better by arguing that the Ohio statute violated the Fourteenth Amendment promise that no state shall “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” In 1886, the Supreme Court had read that provision not to constrain New York from denying admission to an out-of-state insurance corporation that refused to pay, as a condition of admission, a license fee that New York imposed only on out-of-state corporations. The Court reasoned that, in those circumstances, the corporation was not “within [the state's] jurisdiction,” but on the outside looking in, and therefore not eligible for whatever equal protection the Fourteenth Amendment promised.Footnote 153

Instead, the insurers' lawyers primarily argued that the Ohio legislature had violated legislative process provisions of the Ohio State Constitution that governed what to put in bill titles and how to amend statutes.Footnote 154 The insurers lost.Footnote 155 In response, both Travelers and Standard Life and Accident paid the $50,000 deposit, whereas both Union Casualty & Surety and Fidelity & Casualty, stopped selling liability insurance in Ohio. In 1899, four years after it left, the Fidelity and Casualty returned, this time agreeing to pay the $50,000 deposit to do business in the state.Footnote 156

In May 1901, the same month that the new Conference Liability Manual was issued, the Michigan legislature became the first state legislature to go beyond nominal-dollar deposit requirements and specify how liability insurers would set their liability loss reserves—that is, at a minimum of forty percent of net premiums received and, at the insurance commissioner's discretion, even more if the company's liability loss ratio consistently exceeded forty percent.Footnote 157 Proponents of this legislation included the Michigan Insurance Commissioner H.H. Stevens, who less than a year earlier had traveled east to examine the liability insurance business of some of the major insurance companies, and apparently found their liability loss reserves to be inadequate.Footnote 158

This time, in response to the Michigan law, the liability insurers did not go to court, as they had in Ohio years earlier. They instead lobbied for an alternative method of liability loss reserve regulation that mirrored Liability Conference practice. In 1902, Fidelity and Casualty President George Seward argued in a letter to the National Convention of Insurance Commissioners that state insurance regulators should apply the pure-premium method (Frank Law's method, although Seward did not credit Law) of calculating liability premiums to the calculation of liability loss reserves. By multiplying the pure premium losses for the country as a whole by the counter-differentials for each state, one could produce “a ‘standard table of experience’ to be used in determining loss reserves.”Footnote 159 In contrast, Seward complained, Michigan's forty-percent basis for setting liability loss reserve minimums was arbitrary and its method required assuming “that all companies get equal premiums for equal hazards.” This assumption, he argued, was both false and would result in smaller liability reserves for rate-cutting companies—the perverse result of requiring lower minimum reserves for liability companies with higher insolvency risk.Footnote 160 Michigan's Insurance Commissioner Nelson Hadley offered a lengthy defense of the Michigan law.Footnote 161 The National Convention of Insurance Commissioners ultimately refused to endorse either approach.Footnote 162

Legislative efforts continued. A year later, in 1903, New York and Connecticut enacted statutes that used alternative methods for setting liability loss reserve minimums.Footnote 163 On one account, the New York method enacted in 1903, and amended in 1904, had been proposed by the Travelers Insurance Company.Footnote 164 Then, in 1905, five state legislatures enacted roughly the same liability loss reserve law: California, New York, Massachusetts, Illinois, and Connecticut.Footnote 165 By forcing all liability insurers to set liability reserves according to the same criteria, insurance industry supporters argued, these new laws would deter rate-cutting and make those insurers maintain adequate reserves.Footnote 166 The insurance trade press credited Fidelity and Casualty's George Seward with drafting such legislation in New York,Footnote 167 and liability insurers with influencing its passage there as well as in California, Illinois, and Massachusetts.Footnote 168 A few months later, when in September 1905 the Conference reported that it would persist, some reports in the insurance trade press asserted, perhaps mirroring the Conference public position, that Conference members had so decided in part because they believed that the new liability reserve statutes had or would reduce rate cutting by non-Conference rivals.Footnote 169

Less than a year later, however, the Conference declared that it had abandoned its price-fixing effort. The timing here is hardly dispositive, but it is consistent with a causal story in which, assuming continued rate cutting by non-Conference rivals, the presence of liability loss reserve statutes led Conference company managers to value Conference membership less as a solvency signal. That signal plausibly started to lose its value when Michigan enacted its legislation in 1901. Conference companies, however, had good reason not to let Michigan's insurance commissioner gain a monopoly over signaling solvency and instead to criticize Michigan's approach as inferior, as Seward did in 1902. Under the Michigan law, the insurance commissioner had the discretion to raise the minimum reserve for any particular insurer, a feature that liability insurance underwriters largely opposed.Footnote 170

In contrast, save for Connecticut's version,Footnote 171 the 1905 statutes left no discretion to state insurance regulators to raise the company's liability loss reserve minimums above the minimum reserve prescribed by the statute. The 1905 Massachusetts law was typical. It required insurance companies with at least a decade's worth of experience in selling liability insurance to file an annual statement with the state's insurance commissioner. This statement had to contain: (1) the number of persons reported injured under all its forms of liability policies, regardless of whether such injuries resulted in loss to the insurer; (2) the amount paid “on account or in consequence of all injuries so reported,” including payments on lawsuits arising from such injuries, up to August 31 of the reporting year; (3) the number of suits or actions under liability policies that arose out of the reported injuries that had been settled by “payment or compromise”; and (4) the amount paid for those settled suits on or before August 31 of the reporting year. From these data, the Insurance Department calculated the average cost per injury notice and per suit. It then multiplied each of those averages by the number of open accident and lawsuit files for every liability insurer doing business in the state.Footnote 172 The result was a minimum liability loss reserve for each liability insurer derived from the loss experience of the older liability insurance companies.

To be sure, commentators criticized the 1905 statutes,Footnote 173 and in 1911, state legislatures adopted another way to set liability loss reserve minimums in Washington, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Georgia.Footnote 174 Yet, the 1911 statutes underscore how much liability insurers valued solvency regulation without regulator discretion. The National Convention of Insurance Commissioners had endorsed what became the 1911 statutes after consulting with a committee of representatives of the major liability insurance companies.Footnote 175 That committee would only unanimously support a law that did not authorize the state insurance regulator to order additional liability loss reserves above the prescribed minimum.Footnote 176

By then, the major liability insurers were cooperating in another way as well. In December 1910, some months after New York enacted its first workmen's compensation statute, nineteen liability insurers formed the Workmen's Compensation Service and Information Bureau—an effort to price worker compensation policies that, some months later, merged with the Liability Conference's Bureau of Liability Statistics, and later promulgated policies and rates for the growing market for automobile liability insurance.Footnote 177 In some states, this effort operated with express regulatory sanction. For example, the New York legislature had enacted in 1911 the first statute to expressly sanction fire insurance rating bureaus and rely on their rate manuals to police insurers for any “unfair” price discrimination.Footnote 178 In 1912, the New York legislature amended that law to authorize rate-making associations for other kinds of insurance, including liability and workmen's compensation insurance, as well as automobile liability insurance.Footnote 179

Conclusion

A decade after liability insurance for personal injury accidents came to America, the leading liability insurance companies agreed to fix premium rates and pool liability loss information. This article discussed four possible reasons why the cartel abandoned their price-fixing effort in 1906: price competition by non-Conference rivals; defection by Conference companies; fear of state competition laws; and state regulation of liability loss reserves.

This article concluded that price competition by non-Conference rivals played an important role in the Conference's fall. In contrast, state competition law appears not to have made much of a difference. This article found insufficient evidence to assess the importance of Conference member defection. Finally, on the available evidence, it is at least plausible that state solvency regulation of liability insurance loss reserves reduced the value of Conference membership as a signal of company solvency, and thereby contributed to the Conference's fall.

In reaching these conclusions, this article is limited in part by its main sources of evidence: insurance trade journals, state insurance regulator reports, company bulletins, annual firm-level business data as well as the surviving correspondence of two company presidents. In contrast to such evidence, primary materials generated by insurance sales agents may contain much evidence about agent attitudes and sales strategies, which might help assess, for example, the solvency-signal explanation or how often companies defected from the Conference agreement.

This article makes two main contributions. First, it confirms the expectations of both cartel theory and past research on insurance cartels by showing how insurers engaged in unstable price-fixing efforts and shared information to better estimate future claims costs. Second, and perhaps more important, this article offers a deviant case for accounts of the legal influences on American industrial organization. Even if antitrust law and corporate law partially explain the great merger wave, most industries at the time did not experience significant consolidation activity, and these industries varied substantially in organizational form and inter-firm cooperation, among other things. The rise and fall of the first liability insurance cartel raises the possibility that future studies of other industries will reveal a far greater range of possible legal influences on, and thereby help better explain, American industrial organization at the turn of the twentieth century.