Introduction

Frontline service employees are those employees who directly interact with an organization's customers, such as salespeople, waiters, nurses, and flight attendants. Performance in such jobs is dictated by adherence to ‘display rules’, which refer to explicit or implicit standards established by organizations regarding the emotions that these employees display to customers (Hochschild, Reference Hochschild1983; Ashforth & Humphrey, Reference Ashforth and Humphrey1993; Grandey, Reference Grandey2000). For example, the display of positive rather than negative emotions is a common expectation of frontline service employees. This applies even when customers become upset and regardless of whether the employee truly experiences positive emotions (Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry, Reference Parasuraman, Zeithaml and Berry1985; Bitner, Booms, & Tetreault, Reference Bitner, Booms and Tetreault1990). Such emotional displays are an important factor in determining the quality of service delivery and impact employees' well-being (e.g., Bitner, Booms, and Tetreault, Reference Bitner, Booms and Tetreault1990; Grandey, Reference Grandey2000). Here, the term ‘emotional display’ is used to refer to actual emotions displayed by the employee to customers.

To ensure that displayed emotions are consistent with display rules, frontline employees often need to regulate their emotions. The process of regulating one's emotions when serving customers to express organizationally accepted emotions has been coined ‘emotional labor’ (Hochschild, Reference Hochschild1983; Grandey, Reference Grandey2000). As suggested by Hochschild's initial work (Reference Hochschild1983), employees generally employ two main emotional labor strategies when performing emotional labor. Deep acting is the process of consciously regulating unacceptable emotions to express organizationally desirable feelings through the use of strategies such as those of attentional deployment, perspective taking, and cognitive reappraisal (Gross, Reference Gross1998; Grandey, Reference Grandey2000). It has been referred to as the more authentic of the two strategies in that the employee's intention is to no longer experience situation-inappropriate emotions and to actually experience situation-appropriate emotions (Grandey, Reference Grandey2003). On the other hand, surface acting refers to displaying emotions that are not necessarily experienced while masking unacceptable feelings or to amplifying the appearance of emotions to comply with organizational display rules (Gross, Reference Gross1998; Grandey, Reference Grandey2000). The key difference between the two strategies is whether the emotion that is displayed is the emotion that is actually being experienced by the employee (deep acting) or whether the displayed emotion is simply expressed without actually being experienced (surface acting).

Research to date suggests that these two emotional labor strategies impact both employee- and customer-related outcomes, although the effects for deep and surface acting often manifest in opposite directions, with the former typically leading to beneficial outcomes. The findings of some primary studies are summarized in Table 1 and include outcomes related to job performance, job satisfaction, emotional exhaustion, turnover, customer rapport, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty. As a result of these consequential effects of emotional labor, researchers have also exhibited a continued interest in examining the antecedents of emotional labor with a focus on both situational and dispositional causes of emotional labor use. Table 2 summarizes some of the main findings from these previous studies.

Table 1. Outcomes of emotional labor

Table 2. Antecedents of emotional labor

As is shown in Table 2, much of the work on individual-level antecedents of emotional labor has focused on distal dispositional predictors, such as Big Five personality factors, emotional intelligence, and trait affectivity. Far less empirical research has focused on proximal motivational causes of the use of different emotional labor strategies, such as goals or self-efficacy. Nevertheless, a conceptual argument for the effects of motivation and, in particular, goals, has been proposed by Diefendorff and Gosserand (Reference Diefendorff and Gosserand2003). These authors argue that, based on control theory (Carver and Scheier, Reference Carver, Scheier and Krohne1993), motivational goals are necessary components of the dynamic processes of emotional labor. They suggest that people engage in self-regulatory strategies if they detect a discrepancy between their goals and behavioral outcomes (Carver & Scheier, Reference Carver, Scheier and Krohne1993; Diefendorff & Gosserand, Reference Diefendorff and Gosserand2003). That is, employees' motivational goals determine whether they engage in self-regulatory tactics (Carver & Scheier, Reference Carver, Scheier and Krohne1993). In other words, in the context of emotional labor, motivational goals result in individuals using or not using emotional labor strategies to regulate their emotions when interacting with customers (Diefendorff & Gosserand, Reference Diefendorff and Gosserand2003).

In this study, we contribute to the literature on emotional labor by (i) exploring how such motivational goals – in particular an individual's goal orientation – may affect employees' uses of the two emotional labor strategies and (ii) examining the mediating role of self-efficacy in such effects. In doing so, we draw on research showing that individuals employ a motivational approach to achieve their goals (Nicholls, Reference Nicholls1975; Dweck, Reference Dweck1986). Such a motivational approach has been labeled by educational psychologists as ‘goal orientation’ (Nicholls, Reference Nicholls1978; Eison, Reference Eison1979; Dweck, Reference Dweck1986), which is defined as a pattern of beliefs that leads to ‘different ways of approaching, engaging in, and responding to achievement situations’ (Ames, Reference Ames1992: 261). Although a number of theories have demonstrated the important role of goal orientation in determining behaviors (Dweck, Reference Dweck1975; Nicholls, Reference Nicholls1978; Eison, Reference Eison1979), employees' goal orientations have received little attention within the context of emotional labor. Thus, we aim to examine the relationship between goal orientation and emotional labor use for frontline service employees.

Researchers have generally distinguished between two main types of goal orientation through which individuals achieve their goals: performance goal orientation and learning goal orientation (Dweck & Leggett, Reference Dweck and Leggett1988). Performance goal orientation refers to the tendency to engage in activities to demonstrate ability (i.e., performance improvement), while learning goal orientation refers to the tendency to engage in activities to improve one's abilities (i.e., self-development; Dweck, Reference Dweck1986). Thus, the underlying motivations that drive an individual's behavior differ based on whether the person utilizes a learning goal orientation (where the motive is to achieve real change or self-development) or a performance goal orientation (where the motive is to demonstrate that one has achieved an outcome). In the educational context, Dweck (Reference Dweck1986) argued that individuals with a high learning orientation use deeper learning strategies (e.g., paraphrasing and summarizing) to pursue their underlying motives for self-development. In contrast, a performance orientation is related to the use of shallower learning strategies (e.g., memorizing) to achieve goals focused on the outcomes of behaviors. These two strategies have been labeled deep-processing and surface-processing strategies, respectively, in the organizational learning literature (Entwistle & Ramsden, Reference Enwistle and Ramsden1983).

Goal orientation has increasingly been examined in organizational research, demonstrating that it plays an important role in work-related topics such as organizational change (e.g., Gully and Phillips, Reference Gully and Phillips2005), team building (e.g., Bunderson and Sutcliffe, Reference Bunderson and Sutcliffe2003), organizational climate and culture (e.g., Potosky and Ramakrishna, Reference Potosky and Ramakrishna2002), leadership (e.g., Janssen, Onne, Yperen, and Nico, Reference Janssen and Yperen2004), job performance (e.g., Payne, Youngcourt, and Beaubien, Reference Payne, Youngcourt and Beaubien2007), sales performance (e.g., VandeWalle, Cron, and Slocum, Reference VandeWalle, Cron and Slocum2001), employees' customer/selling orientation, and job satisfaction (Harris, Mowen, & Brown, Reference Harris, Mowen and Brown2005). Previous research has supported the significant role of learning and performance goal orientation in self-regulatory tactics and behaviors (e.g., Kanfer, Reference Kanfer1992; VandeWalle, Brown, Cron, and Slocum, Reference VandeWalle, Brown, Cron and Slocum1999).

The main purpose of the present study is to examine the impact of goal orientation on emotional labor strategy use. We expect learning orientation and performance orientation to relate to the extent to which individuals adopt deep and surface acting strategies, respectively. Our expectation is based on the fact that the underlying motives for engaging in deep acting and surface acting are distinct. Service employees engaging in deep acting (i.e., the deeper strategy according to goal orientation theory) aspire to regulate inner feelings (self-regulation) or to achieve real change in terms of the emotions that are experienced. This is consistent with the learning goal orientation of self-development and real change. Surface acting (i.e., the shallower strategy) is based on the motive of expressing an expected emotion without necessarily feeling that emotion. This is consistent with the performance goal orientation of demonstrating outcomes rather than realizing actual change. Thus, we suggest that a stronger learning goal orientation is likely to lead to greater engagement in deep acting strategies, while a stronger performance goal orientation is likely to lead to greater engagement in surface strategies.

It should be noted that previous empirical research has mostly concentrated on global rather than strategy-specific causes of engaging in emotional labor. While this research has generated important insights, it does not allow researchers to differentiate the antecedents of one strategy from another. For example, display rules (e.g., Goldberg and Grandey, Reference Goldberg and Grandey2007) and patient mistreatment (e.g., Grandey, Foo, Groth, and Goodwin, Reference Grandey, Foo, Groth and Goodwin2012) have been shown to increase emotional labor use in general (see Kammeyer-Mueller et al., Reference Kammeyer-Mueller, Rubenstein, Long, Odio, Buckman, Zhang and Halvorsen-Ganepola2013, for an exception). However, few studies differentiate between the antecedents of either emotional labor strategy. Investigating the impacts of either strategy will advance emotional labor theories and might also help managers select and recruit service employees more effectively.

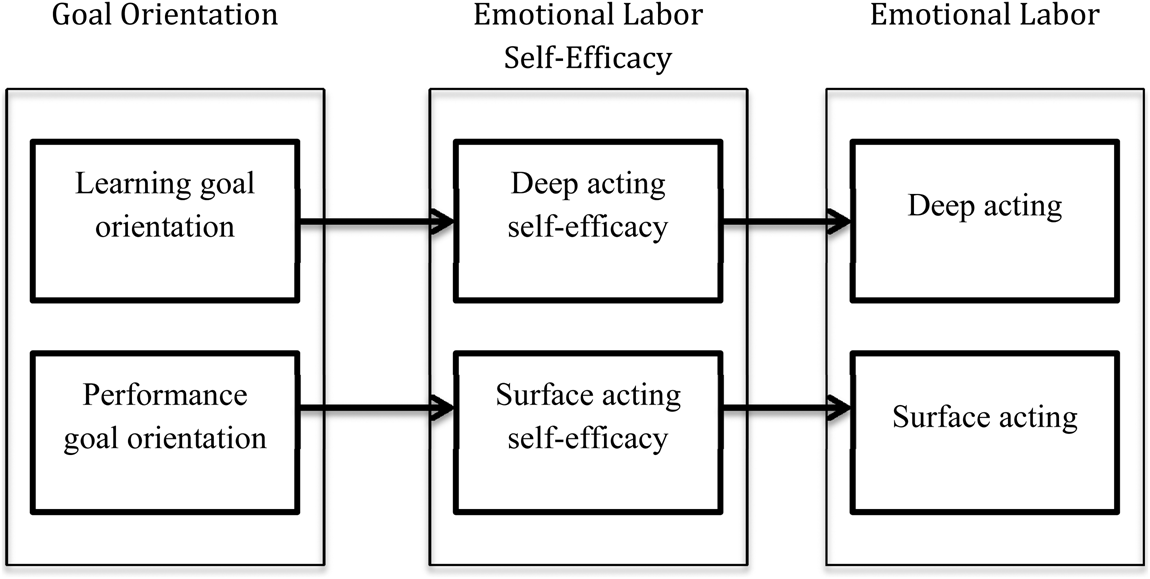

Finally, through this study we also aim to examine the process through which goal orientation affects emotional labor use. Specifically, we focus on the mediating role of emotional labor ‘self-efficacy.’ Self-efficacy is defined as one's beliefs about his or her ability to successfully perform in a specific context (Bandura, Reference Bandura1997). Individuals' expectations of their efficacy determine whether they will engage in coping behaviors and how much effort they will exert in doing so. In the context of emotional labor, deep acting and surface acting self-efficacy serve as necessary components of engagement in either emotional labor strategy. Therefore, we expect to find that an individual's self-efficacy to engage in either emotional labor strategy affects his or her use of that particular strategy in the workplace. As such, the presence of deep acting self-efficacy and surface acting self-efficacy are expected to increase the use of deep and surface acting behaviors, respectively. The self-efficacy to engage in emotional labor strategies has received increasing attention in the literature recently, with evidence supporting a moderating role of emotional labor self-efficacy in the relationship between emotional labor use and both individual and organizational outcomes, such as job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion (e.g., Pugh, Groth, and Hennig-Thurau, Reference Pugh, Groth and Hennig-Thurau2011), employee well-being (e.g., Sloan, Reference Sloan2012), and absenteeism (e.g., Nguyen, Groth, and Johnson, Reference Nguyen, Groth and Johnson2013). In this study, we add to this literature by examining the mediating role of emotional labor self-efficacy in the relationship between goal orientation and emotional labor use. Our hypothesized model, which specifies relationships between goal orientation, self-efficacy, and emotional labor, is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Proposed model of employee goal orientation, emotional labor self-efficacy, and emotional labor strategy use.

In sum, the purpose of this study is twofold. First, drawing on goal orientation theory (Dweck, Reference Dweck1986), which suggests that one's goal orientation approach influences the tendency to use particular types of coping strategies, we examine the impact of goal orientation on emotional labor strategy use for a diverse sample of service employees. Specifically, we examine the impact of learning and performance goal orientations on two types of emotional labor strategies with the expectation that exhibiting a learning goal orientation is a predictor of engagement in deep acting and that exhibiting a performance goal orientation is a predictor of engagement in surface acting. Second, in drawing on Bandura (Reference Bandura1986) theory of self-efficacy, which posits that individuals' self-views influence their behaviors, thoughts, and feelings, we aim to shed light on the mediating effects of emotional labor self-efficacy on the relationship between goal orientation and emotional labor.

Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

Emotional labor

In her seminal book, Hochschild (Reference Hochschild1983) coined the concept of emotional labor and defined it as ‘the management of feeling to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display’ (7). Emotional labor is the process of aligning displayed emotions with organizational display rules and has often been conceptualized as involving the use of two distinct strategies: deep acting and surface acting (Hochschild, Reference Hochschild1983; Grandey & Melloy, Reference Grandey and Melloy2017). As discussed above, these two strategies have been shown to have unique effects, with deep acting generally believed to be the more desirable strategy for employees, organizations, and customers, even though empirical findings are not always consistent (see for example, Adil and Kamal, Reference Adil and Kamal2013; Walsh and Bartikowski, Reference Walsh and Bartikowski2013). Although deep acting and surface acting are theoretically (Hochschild, Reference Hochschild1983; Grandey, Reference Grandey2000) and empirically (e.g., Goldberg and Grandey, Reference Goldberg and Grandey2007; Judge, Fluegge Woolf, and Hurst, Reference Judge, Woolf and Hurst2009; Scott and Barnes, Reference Scott and Barnes2011) defined as distinct strategies, empirical evidence does not always clearly determine whether differential antecedents predict the use of these two strategies. Rather, deep acting and surface acting are often considered to be driven by the same antecedents, as is the case in the opposite direction, even though they are quite distinct regulatory strategies. In this study, we aim to examine whether employees' uses of deep acting and surface acting are underpinned by different forms of goal orientation.

Goal orientation

The concept of goal orientation was initially coined by educational psychologists in the 1970s and 1980s (Dweck, Reference Dweck1975; Nicholls, Reference Nicholls1975; Eison, Reference Eison1979) and has been researched for more than four decades. The theory initially originated as a complement to Atkinson (Reference Atkinson1964) theory of achievement motivation in the classroom and focuses on individual differences in achievement motivation that affect students' educational performance. Goal orientation refers to one's motivational approach to achieving his/her goals (Dweck, Reference Dweck, Lesgold and Glaser1989) and has most often been conceptualized as a two-dimensional construct that consists of learning goal orientation and performance goal orientation.

As discussed above, a learning goal orientation is defined as a person's tendency to develop his or her abilities and to learn new skills (Dweck, Reference Dweck, Lesgold and Glaser1989). In contrast, a performance goal orientation is conceptualized as seeking to gain favorable feedback or to avoid negative judgments of one's ability. In other words, learning-oriented people focus on self-development, whereas people with a performance goal orientation tend to focus on the outcomes of their performance. Dweck (Reference Dweck1986) believes that individuals with a learning goal orientation adhere to the ‘incremental’ theory of intelligence, which defines ability as malleable and subject to change via effort and experience. In contrast, performance goal-oriented individuals are more likely to follow an ‘entity’ theory of intelligence and tend to view their abilities as fixed and unchangeable. Therefore, Dweck (Reference Dweck1986) believes that the main difference is between improving ability (learning-oriented people) and demonstrating ability (performance-oriented people).

Being driven by distinct underlying motives (either demonstrating ability or improving ability), learning and performance goal-oriented individuals often use different behavioral strategies to achieve their goals. In the organizational learning literature, these two types of strategies are referred to as deep-processing and surface-processing strategies (Entwistle & Ramsden, Reference Enwistle and Ramsden1983). Deep-processing strategies are used for knowledge acquisition and for the mastery of a challenging task (Elliot & McGregor, Reference Elliot and McGregor2001), while surface-processing strategies only focus on achieving expected performance for the purpose of self-demonstration rather than self-development (Dweck, Reference Dweck1986). Dweck (Reference Dweck1986) suggests that individuals with a learning goal orientation tend to use deep-processing but not surface-processing strategies due to their emphasis on improving ability rather than on the outcomes of their behaviors. The goal of demonstrating ability and focusing on outcomes, on the other hand, leads performance-oriented individuals to use surface-processing strategies in achievement situations.

Findings of the educational literature consistently support the presence of a positive correlation between learning goal orientation and deep-processing strategies. For example, a learning goal orientation has been shown to be positively correlated with the use of deeper learning strategies such as summarizing and paraphrasing (e.g., Meece, Blumenfeld, and Hoyle, Reference Meece, Blumenfeld and Hoyle1988; Elliot, McGregor, and Gable, Reference Elliot, McGregor and Gable1999). However, performance goals are widely found to be associated with the use of shallower learning strategies such as memorization (e.g., Miller, Greene, Montalvo, Ravindran, and Nichols, Reference Miller, Greene, Montalvo, Ravindran and Nichols1996; Elliot, McGregor, and Gable, Reference Elliot, McGregor and Gable1999). Organizational research on the workplace has supported these findings. As such, employees with a learning goal orientation tend to use deep-processing strategies (e.g., Vermetten, Lodewijks, and Vermunt, Reference Vermetten, Lodewijks and Vermunt2001), while surface-processing strategies are used by performance goal-oriented employees (e.g., Sujan, Weitz, and Kumar, Reference Sujan, Weitz and Kumar1994).

Goal orientation, as an underlying motive of individuals' behavior, determines the type of strategy one uses in various situations to meet his or her achievement goals. As discussed above, the use of a learning orientation leads to the aspiration to meet self-development goals, which in turn leads to a greater use of deep strategies (Dweck, Reference Dweck1986). Therefore, we expect that the higher the level of an individual's learning goal orientation is, the more likely he or she will be to engage in deep acting, as deep acting is more consistent with a focus on self-development for the regulation of inner feelings. On the other hand, the higher the level of an individual's performance goal orientation is, the more likely he or she will be to use surface acting, as the primary focus of performance orientation is placed on the outcomes of behaviors. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1

Learning goal orientation is positively related to service employees' use of deep acting.

Hypothesis 2

Performance goal orientation is positively related to service employees' use of surface acting.

Mediating effects of self-efficacy

The concept of self-efficacy lies at the center of Bandura (Reference Bandura1977, Reference Bandura1986) social cognitive theory. Through his theory, Bandura (Reference Bandura1986) emphasizes the major role that cognition plays in individuals' encoding and performing behaviors. He suggests that individual behaviors are shaped by three main factors, namely, personal, behavioral, and environmental factors. According to Bandura, self-efficacy is defined as the extent to which one believes in his/her ability to succeed in performing a specific task (Bandura, Reference Bandura and Rama- chaudran1994). An individual's degree of self-efficacy in a particular task determines whether and to what extent he or she will engage in the task and to what extent he or she will expend effort on successfully completing the task (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977). Thus, self-efficacy is considered a necessary component of behavior. That is, a person engages in a task more readily if he or she is confident enough about that particular task. In the context of customer service and emotional labor strategies, a conceptualization and measure of emotional labor self-efficacy was introduced by Pugh, Groth and Hennig-Thurau (Reference Pugh, Groth and Hennig-Thurau2011), who argue that frontline service employees' levels of self-efficacy with regard to performing emotional labor represents an important facet of their self-competence. Employees are expected to be more likely to engage in either emotional labor strategy if they are confident about their abilities to successfully perform the given strategy.

Self-efficacy has received more attention in the emotional labor literature in recent years. Although organizations prescribe specific display rules for employees, employee use of either surface or deep acting to follow these display rules may depend on how confident they are in performing either of these strategies effectively. Wilk and Moynihan (Reference Wilk and Moynihan2005) showed that general self-efficacy mitigates negative effects of emotional labor on employees' experiences of physiological and psychological strain. It has also been shown that self-efficacy moderates the relationship between emotional labor and service employees' well-being, such as employees' work commitment (e.g., Heuven, Bakker, Schaufeli, and Huisman, Reference Heuven, Bakker, Schaufeli and Huisman2006), emotional exhaustion (e.g., Pugh, Groth, and Hennig-Thurau, Reference Pugh, Groth and Hennig-Thurau2011), job satisfaction/dissatisfaction (e.g., Pugh, Groth, and Hennig-Thurau, Reference Pugh, Groth and Hennig-Thurau2011; Hsieh, Hsieh, and Huang, Reference Hsieh, Hsieh and Huang2016), and feelings of self-estrangement (e.g., Sloan, Reference Sloan2012). Empirical studies also provide support for the mediating role of self-efficacy. For example, self-efficacy has been shown to mediate the relationship between goal orientation and individual performance (e.g., VandeWalle et al., Reference VandeWalle, Brown, Cron and Slocum1999, Reference VandeWalle, Cron and Slocum2001). Self-efficacy has also been shown to mediate the relationship between emotional labor and its antecedents and outcomes, such as emotional intelligence (e.g., Yan, Xi, and Yiwen, Reference Yan, Xi and Yiwen2014) and job satisfaction (e.g., Hsieh, Hsieh, and Huang, Reference Hsieh, Hsieh and Huang2016). Although the mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between emotional labor and emotional intelligence has been tested in the literature, the mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between emotional labor and its motivational antecedents has not been examined. Given the need to achieve self-efficacy prior to the performance of a specific behavior, we suggest that emotional labor self-efficacy is an essential mediator of the relationship between the two emotional labor strategies and their antecedents. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 3

Deep acting self-efficacy mediates the positive relationship between learning goal orientation and the use of deep acting.

Hypothesis 4

Surface acting self-efficacy mediates the positive relationship between performance goal orientation and the use of surface acting.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Participants were recruited through a professional market research firm based in the United States. The firm has access to a permission-based email database of potential respondents based in the U.S. All potential participants provided the firm with prior written consent to be contacted by email to participate in research studies, and they typically receive a small remuneration for their participation. There has been a steady, upward trend in published management research incorporating samples from professional market research firms as well as crowdsourced platforms (Keith, Tay, and Harms, Reference Keith, Tay and Harms2017). The ease of data collection and relatively lower cost compared to paper-and-pencil surveys has made it an attractive alternative for organizational researchers. Research has shown that the quality of data to be generally of reasonably high quality and comparable to other convenience sampling strategies used in management and psychology (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, Reference Buhrmester, Kwang and Gosling2011; Keith, Tay, and Harms, Reference Keith, Tay and Harms2017). Thus, this data collection method provided a viable strategy for us to collect data for this study.

Potential participants were selected based on their self-reported occupations, as we were interested studied in employees who interact with customers on a daily basis. Of the 469 persons contacted via email, 340 individuals accessed the online survey. We included the following screening question at the beginning of the survey: ‘Does your job involve interacting directly with customers/clients in person?’ Only individuals who responded ‘Yes’ to this question were invited to complete the survey. All other respondents were redirected to another page and were not included in our study. Of the potential respondents, 294 (86.47%) passed the additional screening question. Additionally, 32 surveys were later excluded from our data analysis due to considerable amounts of missing data. Thus, our final sample included 262 service employees, representing an overall response rate of 77.64%. Participants reported a mean age of 48.48 years (SD = 11.60) with a near even split in gender (53.4% were female). The participants reported working predominately in customer service jobs (56%), manager/administrator roles (18%), and professional jobs (13%). The average tenure in the current job was 11.80 years (SD = 9.77 years), whereas the average tenure in the service industry was 16.99 years (SD = 11.70 years).

Participants completed the survey on a single occasion. Consequently, our research design yields cross-sectional data, rather than panel data (which involves multiple measurements at different time points).

Measures

The survey included measures of learning goal orientation, performance goal orientation, deep acting self-efficacy, surface acting self-efficacy, deep acting and surface acting, as well as several demographic variables. All scale items used are shown in the Appendix.

We aimed to examine how employees' general goal orientations and levels of emotional labor self-efficacy affect their use of emotional labor strategies during particular customer service interactions. Therefore, participants were asked to think about the last interaction that they had experienced with a customer/s while answering the items related to emotional labor strategies. To ensure that the emotional labor strategy questionnaire related to their last interactions with a customer/s, all the items related to emotional labor strategies started with the following phrase: ‘In your last interaction with a customer/s ….’ In contrast, all the items related to goal orientation and emotional labor self-efficacy started with the following phrase: ‘In general, ….’

Goal orientation was measured using the 16 items developed by Button, Mathieu and Zajac (Reference Button, Mathieu and Zajac1996). These items were used to assess the employees' degrees of learning goal orientation (eight items) and performance goal orientation (eight items); however, four items (two for each measure) were removed from the study due to low factor loadings. The measures were assessed on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The internal consistency reliabilities (α) of these scales were .87 for learning orientation and .80 for performance orientation. An exploratory factor analysis of the 12 items provided evidence of the construct validity of the measures in that two factors emerged where each item loaded on its respective factor (loadings all greater than .50) but not on the other.

We assessed emotional labor strategies with six items (three items for deep acting and three items for surface acting) drawn from Grandey (Reference Grandey2003) and initially developed by Brotheridge and Lee (Reference Brotheridge and Lee2003). The items were assessed on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 = never to 5 = often. The internal consistency reliabilities for deep acting and surface acting scales were .89 and .91, respectively. Our exploratory factor analysis provides evidence for the two factors, where deep acting items all loaded on one factor and surface acting items all loaded on the other factor.

Employees' deep acting self-efficacy and surface acting self-efficacy were measured with a 6-item measure (3 items each) that we developed following Bandura (Reference Bandura2006) recommendations for using self-efficacy measures. Similar items have been used in prior studies (Pugh, Groth, and Hennig-Thurau, Reference Pugh, Groth and Hennig-Thurau2011) to measure levels of emotional labor self-efficacy. On a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = not at all to 5 = to a great extent, participants were asked to rate how confident they were in performing the behaviors when interacting with customers/clients. The internal consistency reliabilities for these scales were .84 for deep acting self-efficacy and .94 for surface acting self-efficacy. Our exploratory factor analysis provided evidence for the two factors, where deep acting self-efficacy items all loaded on one factor and surface acting self-efficacy items all loaded on the other factor.

We also controlled for employees' experience in service industry because of its relationship with emotional labor.

Data analysis

Hypotheses 1 and 2 were tested through the use of linear regressions. To test Hypothesis 1, deep acting was regressed on learning orientation while controlling for performance goal orientation. Hypothesis 2 was also tested by regressing surface acting on performance goal orientation while the effect of learning goal orientation was controlled. We used the SPSS macro developed by Preacher and Hayes (Reference Preacher and Hayes2008) to test the indirect effects proposed in Hypotheses 3 and 4. The process/macro provides a method for examining the significance of indirect effects of the independent variable on the dependent variable. Furthermore, following recommendations by MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams and Lockwood (Reference MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams and Lockwood2007), we used bootstrapping to test the indirect effects of learning goal orientation and performance goal orientation on deep acting use and surface acting use, respectively.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 3 displays the means, standard deviations, internal consistency, and intercorrelations of all variables used in this study. Although we formally test our hypotheses in the next section, Table 3 suggests that the correlations obtained are consistent with our hypotheses. Specifically, consistent with Hypotheses 1 and 3, a learning goal orientation is positively correlated with deep acting self-efficacy (r = .31, p < .01) and deep acting (r = .20, p < .01), and deep acting self-efficacy is positively and strongly related to deep acting (r = .55, p < .01). Similarly, consistent with Hypotheses 2 and 4, performance goal orientation is positively correlated with surface acting self-efficacy (r = .27, p < .01) and surface acting (r = .19, p < .01), and surface acting self-efficacy is strongly correlated with surface acting (r = .61, p < .01). However, performance goal orientation is also positively correlated with deep acting self-efficacy (r = .34, p < .01) and deep acting (r = .24, p < .01).

Table 3. Means, standard deviations, internal consistency alphas, and correlations among measures

Note. N = 262. Gender coded 1 = male and 2 = female.

Internal reliabilities (alpha coefficients) for the overall constructs are given in the parentheses on the diagonal.

*p < .05 (two-tailed). **p < .01 (two-tailed).

Hypothesis testing

Hypotheses 1 and 2 were tested through the use of linear regressions (see Table 4). We used organizational tenure and service industry tenure as control variables in all of our analyses. Hypothesis 1 was tested by regressing deep acting on learning orientation while controlling for performance goal orientation. Learning goal orientation was positively related to employees' deep acting (β = .13, t = 1.94, p = .05). Similarly, Hypotheses 2 was tested by regressing surface acting on performance goal orientation while controlling for learning goal orientation. In support of this hypothesis, performance goal orientation was associated with an increase in surface acting (β = .21, t = 3.07, p < .01). We also examined interaction effects of learning goal orientation and performance goal orientation on the use of deep and surface strategies to test whether it is the relative propensities of the two goal orientations that determine the use of deep and/or surface strategies. However, neither of these interaction effects were significant (deep acting: β = .65, t = .91, p = .36; surface acting: β = .50, t = .69, p = .49)Footnote 1. Furthermore, we examined whether each goal orientation is more closely related to one form of the emotional labor strategy than the other by calculating a difference score (deep acting – surface acting) and by regressing this on the goal orientation variables. Neither learning orientation nor performance orientation was significantly related to this difference score (learning goal orientation: β = .12, t = 1.64, p = .10; performance goal orientation: β = −.05, t = −.65, p = .52).

Table 4. Regression analyses predicting deep acting and surface acting by learning goal orientation and performance goal orientation controlling for service industry experience

Note. *p = .05 (two-tailed). **p < .01 (two-tailed).

We used the SPSS macro developed by Preacher and Hayes (Reference Preacher and Hayes2008) to test the indirect effects proposed in Hypotheses 3 and 4. The macro provides a method for examining the significance of the indirect effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. Tables 5 and 6 show the results of Hypotheses 3 and 4, respectively. Hypothesis 3 suggested that deep acting self-efficacy mediates the relationship between learning goal orientation and deep acting use. Hypothesis 4, on the other hand, posited that the relationship between performance goal orientation and surface acting use is mediated by surface acting self-efficacy.

Table 5. Results of mediation analysis predicting deep acting use by learning goal orientation and deep acting self-efficacy

LL, lower limit; CI, confidence interval; UL, upper limit.

Note. Bootstrap sample size = 10,000.

Table 6. Results of mediation analysis predicting surface acting use by performance goal orientation and surface acting self-efficacy

LL, lower limit; CI, confidence interval; UL, upper limit.

Note. Bootstrap sample size = 10,000.

As recommended, we used a bootstrapping approach to determine the confidence intervals of our estimates (MacKinnon et al., Reference MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams and Lockwood2007; Preacher and Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008). Bias-corrected confidence intervals of 95% were estimated for the indirect effects by bootstrapping 10,000 samples. The confidence interval for the indirect effect of learning goal orientation on deep acting use ranged from .04 to .39 (see Table 5). As zero is not included in this confidence interval, Hypothesis 3 is supported. In support of Hypothesis 4, the confidence interval of the indirect effect of performance orientation on surface acting ranged from .20 to .62 (see Table 6). Thus, our results suggest that the relationship between goal orientation and emotional labor is fully mediated by emotional labor self-efficacy. That is, learning (performance) goal orientation predicts deep (surface) acting only if deep (surface) acting self-efficacy mediates this relation.

Contradictory to our expectation that only a learning goal orientation predicts the use of deep acting, our findings also indicate that a performance goal orientation is positively related to the use of deep acting strategies when controlling for the effects of leaning goal orientation (β = .19, t = 2.77, p < .01). Therefore, we determined whether the expression of deep acting self-efficacy mediates the relation between a performance goal orientation and deep acting use. The confidence interval for the indirect effect ranged from .09 to .46, suggesting that deep acting self-efficacy mediates the relation between performance goal orientation and deep acting use (the direct effect was not significant).

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the relationships between goal orientation, self-efficacy, and emotional labor strategy use. In drawing on goal orientation and self-efficacy theories, we developed and tested a model that examined the role of goal orientation in predicting emotional labor use and the mediating role of emotional labor self-efficacy in this relationship. Our results show that employees' goal orientations determine the use of emotional labor strategies. In addition, we found support for our hypothesis that the two types of goal orientation are related to the use of separate emotional labor strategies. Specifically, we found that a learning goal orientation is primarily a predictor of deep acting use, while a performance goal orientation is a stronger predictor of surface acting use (although it does also predict deep acting use). Each of these effects occurred independently of the level of the other goal orientation dimension. Finally, this study showed that goal orientation affects emotional labor only through the mediating role of emotional labor self-efficacy.

Theoretical contributions

Our study provides a number of theoretical contributions to the emotional labor literature. First, although the role of goal orientation has been examined in relation to many other important work-related outcomes (e.g., VandeWalle, Cron, and Slocum, Reference VandeWalle, Cron and Slocum2001; Potosky and Ramakrishna, Reference Potosky and Ramakrishna2002; Bunderson and Sutcliffe, Reference Bunderson and Sutcliffe2003; Janssen et al., Reference Janssen and Yperen2004; Gully and Phillips, Reference Gully and Phillips2005; Harris, Mowen, and Brown, Reference Harris, Mowen and Brown2005), this study is the first to examine how individuals' goal orientations affect their use of two types of emotional labor strategies. According to goal orientation theories (Nicholls, Reference Nicholls1978; Dweck and Leggett, Reference Dweck and Leggett1988), one's goal orientation determines whether and how one engages in self-regulatory activities. Our study shows that, within the customer service context, goal orientation – the motivational approach through which individuals achieve their goals – influences one's use of emotion regulation strategies. Recently, the role of motivation has been investigated in the emotional labor literature (e.g., Diefendorff and Gosserand, Reference Diefendorff and Gosserand2003; Grandey and Diamond, Reference Grandey and Diamond2010; Grandey, Chi, and Diamond, Reference Grandey, Chi and Diamond2013). Diefendorff and Gosserand (Reference Diefendorff and Gosserand2003) suggest that the discrepancy between emotional displays and display rules drives individuals to use emotion regulation strategies. Grandey and Diamond (Reference Grandey and Diamond2010) also compared job design and emotional labor perspectives in explaining how interactions affect employee motivation and well-being. More recently, the moderating role of motivation in the relationship between emotional labor and employee job satisfaction was examined in three related empirical studies (Grandey, Chi, & Diamond, Reference Grandey, Chi and Diamond2013). Although previous research has shown the moderating effect of motivation within the context of emotional labor, our study is the first to test the triggering role of motivation in using self-regulatory tactics. Our study examines how individuals' motivational approaches (goal orientation) influence their use of emotional labor strategies. Our findings are also aligned with the findings of previous empirical studies (e.g., Kanfer, Reference Kanfer1992; VandeWalle et al., Reference VandeWalle, Brown, Cron and Slocum1999) that demonstrate the important role of goal orientation in self-regulatory behavior.

Our study also makes an important theoretical point about the ways in which the two goal orientations affect emotional labor strategies. Specifically, we found a main effect for each of the goal orientations on its aligned emotional labor strategy; however, there was no evidence that the two goal orientation dimensions interactively influenced emotional labor or that the effects occurred in a relative sense. We thus conclude that the effect of learning goal orientation on deep acting strategy use does not depend on whether an individual is high or low in performance orientation and that the effect of performance goal orientation on surface acting strategy use does not depend on whether an individual is high or low in learning goal orientation.

Our study not only explores how emotional labor is influenced by goal orientation but also differentiates between the differential usage of the two emotional labor strategies. In the emotional labor literature, deep acting is generally considered the strategy that leads to more favorable outcomes for employees, customers, and organizations. Therefore, this study contributes to the emotional labor literature by adding to our understanding of emotional labor strategy use by explaining what types of people are more likely to use the better strategy (i.e., deep acting). Specifically, we show that people exhibiting learning and performance goal orientations are most likely to engage in deep acting. These findings are partially consistent with goal orientation theory (Dweck, Reference Dweck1986), suggesting that individuals with a learning goal orientation tend to use deeper tactics to achieve their goals of self-development. However, our findings are inconsistent with goal orientation theory's predictions on performance orientation, which is theoretically only expected to lead to the use of shallower strategies.

How can we account for the discrepancy found between the predictions of Dweck (Reference Dweck1986) goal orientation theory and our findings that performance goal orientation is positively associated with both surface and deep acting? One possibility has to do with the multidimensional nature of performance goal orientation. In the goal orientation literature, researchers have proposed another typology of goal orientation in which performance goal orientation comprises performance-approach goal orientation and performance-avoidance goal orientation (Elliot, Reference Elliott1994; Elliot and Harackiewicz, Reference Elliot and Harackiewicz1996). Performance-approach goals focus on demonstrating ability in relation to others. However, the performance-avoidance dimension refers to a tendency to avoid being perceived as incompetent compared to others (Elliot, Reference Elliott1994; Elliot & Harackiewicz, Reference Elliot and Harackiewicz1996; Elliot & Church, Reference Elliot and Church1997; VandeWalle, Reference VandeWalle1997). These two approaches have been shown to be driven by different antecedents (Elliot & Church, Reference Elliot and Church1997) and to be related to different outcomes (Elliot & Harackiewicz, Reference Elliot and Harackiewicz1996). When considering performance goal orientations with two dimensions, performance-avoidance goals are believed to be dysfunctional (Brophy, Reference Brophy2004). However, the outcomes of performance-approach goals have been shown to be aligned with learning orientation outcomes (Elliot & Harackiewicz, Reference Elliot and Harackiewicz1996; Elliot & Church, Reference Elliot and Church1997).

In addition, this study sheds light on the relationship between goal orientation and emotional labor by highlighting the mediating role of self-efficacy. Consistent with a large body of evidence on self-efficacy (see Bandura, Reference Bandura1977), our study demonstrates that self-efficacy is an important precursor of emotional labor behaviors. That is, setting display rules and instructing employees to engage in various strategies is not sufficient for organizations; rather, employees need to have the confidence and skills to be able to engage in the expected strategies. Although in the emotional labor literature, there has always been an assumption that display rules drive employees to engage in emotional labor strategies (e.g., Goldberg and Grandey, Reference Goldberg and Grandey2007; Lee, An, and Noh, Reference Lee, An and Noh2014), the literature on self-efficacy shows that one's self-efficacy is a critical factor that shapes this process (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977; VandeWalle et al., Reference VandeWalle, Brown, Cron and Slocum1999, Reference VandeWalle, Cron and Slocum2001).

Our results show that goal orientation in itself does not necessarily predict emotional labor use. Rather, emotional labor self-efficacy fully mediates this relationship. That is, a learning goal orientation leads to the use of deep acting strategies by increasing one's confidence in the use of deep acting strategies. Similarly, a performance goal orientation spurs engagement in surface acting by increasing surface acting self-efficacy. Complementary to these findings, our study not only examines the mediating role of self-efficacy but also focuses on the relationship between emotional labor strategies and their antecedents (learning and performance goal orientations). One key finding of this study relates to the fact that emotional labor self-efficacy is a necessary mediating factor in the relationship between personal attitudes (goal orientation) and emotional labor use.

As another theoretical contribution of our study, we clarify the relationship between goal orientation and self-efficacy. According to goal orientation theory (Dweck, Reference Dweck, Lesgold and Glaser1989), a learning goal orientation results in higher levels of self-efficacy, while a performance goal orientation leads to lower levels of self-efficacy. Empirically, a learning goal orientation positively relates to self-efficacy (e.g., Phillips and Gully, Reference Phillips and Gully1997; Steele Johnson, Beauregard, Hoover, and Schmidt, Reference Steele Johnson, Beauregard, Hoover and Schmidt2000; Brown, Reference Brown2001; Potosky and Ramakrishna, Reference Potosky and Ramakrishna2002), but a performance goal orientation has no effect or a slightly negative effect on self-efficacy (e.g., Phillips and Gully, Reference Phillips and Gully1997; Brown, Reference Brown2001; Potosky and Ramakrishna, Reference Potosky and Ramakrishna2002). Our study, however, reveals that the impact of goal orientation approaches on self-efficacy depends on the task to which self-efficacy is related. That is, both goal orientation approaches can positively affect self-efficacy. Specifically, our study shows that learning-oriented individuals tend to have higher levels of deep acting self-efficacy, while individuals with a performance goal orientation are more likely to be high in both deep acting self-efficacy and surface acting self-efficacy.

Practical implications

The role of goal orientation in work settings has received much attention in the organizational literature (e.g., Potosky and Ramakrishna, Reference Potosky and Ramakrishna2002; Bunderson and Sutcliffe, Reference Bunderson and Sutcliffe2003; Janssen et al., Reference Janssen and Yperen2004; Gully and Phillips, Reference Gully and Phillips2005; Harris, Mowen, and Brown, Reference Harris, Mowen and Brown2005; VandeWalle, Cron, and Slocum, Reference VandeWalle, Cron and Slocum2001), suggesting that individual's motivational approaches determine the types of strategies that they use to achieve their goals. Goal orientations drive employees to engage in desirable (deeper) or undesirable (shallower) strategies (Sujan, Weitz, & Kumar, Reference Sujan, Weitz and Kumar1994; Vermetten, Lodewijks, & Vermunt, Reference Vermetten, Lodewijks and Vermunt2001). Therefore, managers are advised to take this into consideration while selecting and training employees, as their goal orientations can potentially predict their use of desirable or undesirable emotional labor strategies. Specifically, the findings of our study suggest that a learning goal orientation supports deeper emotional labor strategy use (i.e., deep acting), whereas performance-oriented people tend to use both strategies (i.e., deep acting and surface acting).

Theories on goal orientation generally suggest that a learning goal orientation leads to positive behaviors, such as perseverance, while a performance goal orientation is positively associated with negative behaviors, such as dysfunctional performance tactics (Nicholls, Reference Nicholls1975; Dweck, Reference Dweck1986). Some studies also have suggested that learning goal oriented individuals tend to perform better than compared to individuals with a performance goal orientation (see Utman, Reference Utman1997, for a meta-analytic review). However, our study shows that this is not always the case. We show that, in the context of emotional labor, performance goal orientation can be beneficial to service employees by motivating them to use deep acting strategies. As noted above, deep acting has been shown to be positively associated with favorable individual (e.g., Lam and Chen, Reference Lam and Chen2012; Johnson and Spector, Reference Johnson and Spector2007; Jiang, Jiang, and Park, Reference Jiang, Jiang and Park2013; Walsh and Bartikowski, Reference Walsh and Bartikowski2013) and organizational (e.g., Totterdell & Holman, Reference Totterdell and Holman2003; Beal, Trougakos, Weiss, and Green, Reference Beal, Trougakos, Weiss and Green2006; Hülsheger, Lang, and Maier, Reference Hülsheger, Lang and Maier2010) outcomes. Therefore, the positive effect of performance goal orientations on selection processes might be beneficial as it encourages the use of deep acting strategies.

This study also highlights the important role of self-efficacy in the relationship between goal orientation and emotional labor strategy use. The literature on self-efficacy suggests that individuals' self-efficacy determines whether and how they engage in an activity (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977). In the context of emotional labor, our study shows that emotional labor self-efficacy determines whether and how service employees engage in emotional labor strategies. That is, emotional labor self-efficacy is a necessary component of emotional labor use. Given the necessity of emotional labor self-efficacy, our study suggests that managers should pay attention to service employees' emotional labor self-efficacy as display rules and motivations (i.e., goal orientations) do not automatically result in emotional labor use. Rather, service employees need to be confident enough to be able to engage in these strategies. Therefore, our study suggests that to help service employees use emotional labor strategies and deep acting strategies, in particular, managers are advised to focus on service employees' levels of emotional labor self-efficacy, which can be managed through the delivery of training and peer support.

On the other hand, our study shows that one of the ways to improve employees' emotional levels of labor self-efficacy is through developing goal orientation, as it positively affects emotional labor self-efficacy. The development of employees' goal orientation (i.e., enhancing learning and performance goal orientation) results in higher levels of deep acting self-efficacy, which itself leads to desirable individual and organizational outcomes (Beal et al., Reference Beal, Trougakos, Weiss and Green2006; Johnson & Spector, Reference Johnson and Spector2007). The effect of goal orientation development has been previously shown in the literature. Previous studies have shown that the development of goal orientation has positive effects on individuals' behaviors, such as negotiation skills (Stevens & Gist, Reference Stevens and Gist1997) and performance adaptability (Gist & Stevens, Reference Gist and Stevens1998; Kozlowski, Gully, Brown, Salas, Smith, & Nason, Reference Kozlowski, Gully, Brown, Salas, Smith and Nason2001). The positive effect of goal orientation development on self-regulation has also been supported in the literature (Noordzij, van Hooft, van Mierlo, van Dam, & Born, Reference Noordzij, van Hooft, van Mierlo, van Dam and Born2013). Therefore, managers can benefit from developing goal orientation to have employees with higher levels of emotional labor self-efficacy, leading to the use of emotional labor strategies.

Limitations and future research

As with any research study, our study has certain limitations. To examine service employees' uses of emotional labor strategies, we only focused on the service employees' perspective and asked them to retrospectively recall their use of emotional labor strategies, which may have created a recall bias. Future research may address this issue by asking service employees to complete the survey immediately after a specific interaction with a customer. Another limitation of our study is that information on the originality and cultural background of the participants was not available. Although it is not uncommon in survey research to not explicitly ask respondents about their cultural and ethnic background, this may be problematic given the multi-national nature of the United States. Future research should address this problem by assessing cultural backgrounds of participants and including such data as covariates. Furthermore, testing the proposed effects among participants from non-Western cultures will allow the generalizability of the findings to be assessed. In addition, our data was collected using a cross-sectional design, which limits conclusions about cause-effect relationships. This is problematic as we cannot conclude with certainty that it is goal orientation that is the cause of emotional labor and self-efficacy, or whether the relationships represent either reverse causality or the effects of a confounding variable. Using a panel design in which data is collected longitudinally would to some extent reduce this problem as the possibility of reverse causality can be evaluated, however even panel data cannot eliminate the possibility of confounding variables. Consequently, future research should seek to minimize this problem by using experimental designs in which the effects of learning and performance goal orientation on emotional labor use are manipulated.

Finally, consistent with prior research (e.g., Kozlowski et al., Reference Kozlowski, Gully, Brown, Salas, Smith and Nason2001; Steele Johnson et al., Reference Steele Johnson, Beauregard, Hoover and Schmidt2000; Noordzij et al., Reference Noordzij, van Hooft, van Mierlo, van Dam and Born2013) and based on the initial conceptualization of goal orientation (Dweck, Reference Dweck1975; Nicholls, Reference Nicholls1975; Eison, Reference Eison1979), our study considers goal orientation as a two-dimensional construct (i.e., learning goal orientation and performance goal orientation). However, more recent research has expanded on this typology in describing the two dimensional nature of performance goal orientation, namely performance-approach and performance-avoidance (Elliot, Reference Elliott1994; Elliot & Harackiewicz, Reference Elliot and Harackiewicz1996; Elliot & Church, Reference Elliot and Church1997; VandeWalle, Reference VandeWalle1997). Similar to research on performance goal orientation, researchers have begun to consider the two dimensional nature of a learning goal orientation construct which comprises a learning-approach and learning-avoidance goal orientations (Pintrich, Reference Pintrich2000; Elliot & McGregor, Reference Elliot and McGregor2001). Breaking down the performance goal orientation into two dimensions (i.e., performance-approach and performance-avoidance) might help explain our contradictory findings. Although individuals with an approach-performance goal orientation tend to focus on demonstrating competence (Elliot & Harackiewicz, Reference Elliot and Harackiewicz1996; Elliot & Church, Reference Elliot and Church1997), an avoidance-performance goal orientation is responsible for engagement in dysfunctional behavior (Brophy, Reference Brophy2004). Future research may replicate this study while considering performance goal orientation as a multidimensional construct to separately examine the effects of performance-approach and performance-avoidance strategies on emotional labor use.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that goal orientation and self-efficacy play an important factor in the shaping the emotional labor process of service employees that have been largely overlooked in prior research. As an initial examination into this area, a variety of significant contributions to the literature were identified, such that learning-oriented service employees tend to use deep acting, while performance-oriented service employees use both emotional labor strategies, and that both processes are mediated by self-efficacy. These findings provide future directions for research that can help advance our theoretical understanding of the role that motivational processes can play in the emotional labor process of frontline employees.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2019.63

Author Contributions

Mahsa Esmaeilikia acknowledges that Markus Groth has read and approved the paper and has met the criteria for authorship.