As the nineteenth century dawned over the Atlantic world, its largest human migration, the transatlantic slave trade, came under serious and sustained assault. Saint Dominguans landed a heavy first blow in 1804 by successfully concluding a massive uprising and permanently closing the huge traffic to their shores. A few years later, the British and United States governments banned their trades, after long campaigns by Enlightenment thinkers, zealous evangelicals, and political reformers. By 1836, every other Atlantic world ‘carrier’ had either promulgated abolition laws or signed international treaties outlawing the trade. Unprepared to rely on these steps alone, many nations prescribed harsh penalties for persistent traffickers, deployed slave trade suppression fleets to African, South American, and Caribbean waters, and jointly created Courts of Mixed Commission to adjudicate slaving cases. Together, these measures represented an onslaught unprecedented in the history of the Atlantic slave trade, and in the history of human rights.Footnote 1

This pressure did not, however, cause the trade to simply wither away. Instead, traffickers defied abolition and suppression, forcing huge numbers of captives aboard illegal slave ships. According to the Voyages database, almost 1.2 million men, women, and children departed from the slaving coasts of Africa after 1836, when Portugal became the final carrier to abolish the trade, up to 1866, when the last slaver crossed the Atlantic Ocean.Footnote 2 An additional 450,000 captives arrived in the Spanish colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico, and in the Empire of Brazil, before 1836, but after the Spanish and Brazilian bans of 1820 and 1830.Footnote 3 Taking into account shipboard deaths, slaving to minor destinations, and Voyages omissions (this was a secret trade, after all), well over 1.65 million captives left African shores illegally in the nineteenth century. This figure represents 13 per cent of all embarkations during the trade’s entire 350-year history.Footnote 4

Historians’ analyses of this large and enduring traffic typically emphasize the many weaknesses of state suppression. One major focus is the failure of successive Spanish, Brazilian, and Portuguese governments to earnestly enforce their abolition laws.Footnote 5 These governments, which fully appreciated Cuba and Brazil’s increasing dependence on slave-grown sugar and coffee, abolished their trades only under considerable diplomatic pressure and subsequently failed to rigorously suppress illegal slaving under their flags and to their shores. A second major theme is the debilitating effect of state sovereignty on international suppression. One problem was that the US and France forbade other nations from policing vessels sailing under their colours, despite committing few resources to do the job themselves.Footnote 6 As a result, a wide cast of traffickers found shelter beneath the American and French flags. Another difficulty was that the Mixed Commission system became weaker as many nations, most notably Britain, came to eschew these tribunals in favour of their own court systems.Footnote 7

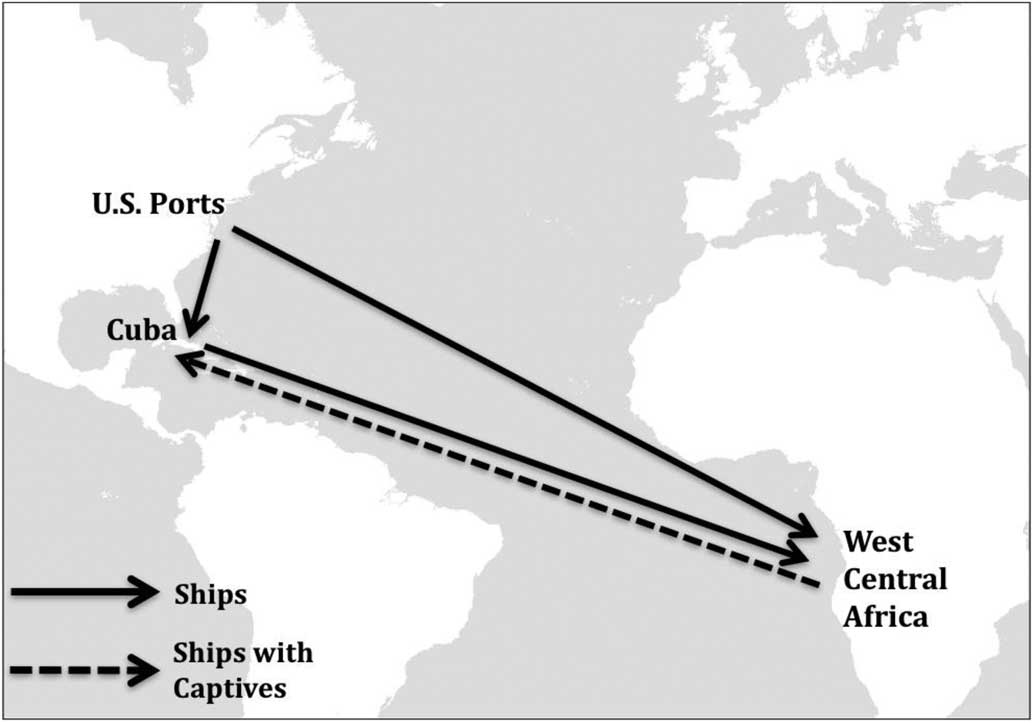

This article rethinks the trade’s persistence by closely examining the work of traffickers between 1850 and 1866. This was a distinctive phase in the history of the trade. In 1850, the Brazilian government closed the massive illicit traffic to its shores, heralding a new era dominated by the United States, West Central Africa, and Cuba. Each region in the post-1850 nexus performed particular functions, as illustrated in Figure 1.Footnote 8 The first region, the United States, became by far the largest supplier of slaving vessels, and, alongside Cuba, a major departure point for voyages. These roles owed much to the availability of American-flagged ships in large ports such as New York City, the booming metropolis where the US trade was based. The second region, West Central Africa, was the major source of captives for those American ships. According to Voyages, 70 per cent of all 225,609 post-1850 embarkations occurred between Landana, the region’s northern outpost on the Loango Coast, and Moçâmedes, at the southern end of Portuguese Angola.Footnote 9 The captives who departed these and other African shores headed almost invariably for Cuba. This third region was the final major market for illegally trafficked Africans in the Americas. It would continue to receive them until the trade’s final demise in 1866.Footnote 10

Figure 1 Major flows of slave ships and captives in the illegal transatlantic slave trade after 1850.

Historians have offered only a partial picture of how slave traders financed the traffic during its final phase. In a small portion of his classic 1987 book on the ending of the slave trade, David Eltis used evidence from British archives to argue that Cuba was the main source of capital, with merchants in West Africa, West Central Africa, and New York also playing minor roles. In 2012 and 2013, Roquinaldo Ferreira and Leonardo Marques offered a little further detail on investment from West Central Africa and New York. Also in 2013, Martín Rodrigo highlighted a few examples of Cuban and Spanish investment, typically involving Catalonia.Footnote 11 Taking a slightly different approach, Eltis and other historians have demonstrated some of the ways in which merchants principally engaged in legal trade indirectly supported the traffic. One recent example of this work is Claudia Varella’s examination of New York sugar merchant Moses Taylor, whose commercial ties with Cuba occasionally intersected with the traffic.Footnote 12 Like the other studies, Varella’s yields some important pieces of the financing puzzle. What remains to be done, however, is to recover even more pieces, and especially, to fit them together, and to interpret the broader meanings of the overall picture.

Table 1 The ‘ship’ shareholdings in the voyage of the Haidee (1858).

Source: TNA, FO 84/1086, Sánchez memo in Archibald to Malmesbury, 3 May 1859.

This article reconstructs the transatlantic nature of slave trade financing. It argues that investors’ ability to tailor their investment patterns to the context of suppression, and to move capital through prevailing global trading patterns, was a major factor in sustaining the traffic. This thesis is developed over two sections. The first section uses financial data from fifteen illegal voyages to identify who investors were and how they deployed their capital (for a list of the voyages, see Table 2 in the appendix). The major point is that slave traders internationalized investment to limit risk and to boost the chances of handsome returns. The second section uses slave traders’ intercepted correspondence and reports from British and US slave trade spies to explore how investors shifted slave trade capital around the Atlantic basin.Footnote 13 Three subsections highlight how moving capital was the lifeblood of this deadly trade, enabling traffickers to pool capital before voyages took place, to draw captives to the coast for embarkation, and to distribute returns to far-flung investors after voyages ended. They also show how slave traders developed these flows in collaboration with an international array of merchants and bankers. These partners helped traffickers feed slave trade capital into widening patterns of nineteenth-century global commerce and finance. Often taking the form of cloth, flour, or a simple bill of exchange, this capital travelled the Atlantic basin with near impunity, until suppression finally achieved its goal.

The investment structure of the illegal slave trade

Investing in illegal slaving voyages was potentially lucrative, but it was also risky. On the one hand, rising world sugar prices boosted slave prices in Cuba, and created unprecedented profit rates for investors.Footnote 14 For the period between 1856 and 1867, David Eltis estimates average profit rates of 91 per cent, far beyond the 10 per cent common in the eighteenth-century trade.Footnote 15 On the other hand, investors faced high risks. In addition to the traditional risks from shipboard revolt, shipwreck, and rampant disease, illegal voyages were in danger of capture by naval patrols. Interception was a serious concern. After 1850, British, Portuguese, French, US, and Spanish cruisers patrolled African, Cuban, and US waters, capturing around 40 per cent of all transatlantic slavers.Footnote 16 Voyages that beat those odds faced further risks and costs in Cuba. Many of the island’s officials demanded large bribes in exchange for safe disembarkations, and some colonial administrations, such as that of Captain General Juan de la Pezuela (1853–54), were quite effective at ‘confiscating’ newly arrived captives.Footnote 17

Two broad groups of traffickers invested in voyages despite these risks. The first comprised residents of the US and West Central Africa. These investors were separated by great distances and were of diverse origins in Portugal, Brazil, and Africa, but they shared the Portuguese language and long experience in the illegal slave trade in West Central Africa and Brazil before 1850. When the Brazilian government suppressed its traffic in that year, slaving fraternities on both sides of the South Atlantic splintered. As Leonardo Marques has shown, some slave traders simply retired from the traffic, but others, mainly from West Central Africa, emigrated to the United States.Footnote 18 By the mid 1850s, a small stream of slave trade émigrés had trickled into New York City. A few more traffickers subsequently arrived from other parts of the Luso-Atlantic, which meant that about a dozen dedicated slave traders were ensconced in the merchant district of Lower Manhattan. Though they occasionally operated out of other US ports, including Boston, Baltimore, and New Orleans, New York would remain their base until the early 1860s.

The New York immigrants were typified by Manoel Basílio da Cunha Reis, a slave trader with long experience in the South Atlantic and strong ties to West Central Africa. Born in Portugal in 1822, he had moved to Brazil as a young man and operated in Rio de Janeiro, the shipping and finance centre of the illegal slave trade in South America.Footnote 19 By the early 1850s, he had established himself at the coastal town of Ambriz in northern Angola. In 1854, he was described by the British Foreign Office as a ‘notorious slave dealer’ who kept captives in barracoons (temporary housing) north of Ambriz on the Congo river.Footnote 20 Facing increasing pressure from both the British and Portuguese authorities, and with reopening of the Brazilian trade seeming unlikely, Cunha Reis sailed to New York in 1856.Footnote 21 He was joined in the US by Antonio Augusto Botelho, José da Costa Lima Viana, José Lucas Henriques da Costa, and José Pedro da Cunha, all of whom had similar career trajectories.Footnote 22

Cunha Reis and his allies had come to New York to break into the illegal slave trade to Cuba, the final major open market for captives in the Americas. Their basic strategy was to purchase vessels in US ports and dispatch them to West Central Africa, where their correspondents would force captives aboard and onwards to the Caribbean. Occasionally, vessels would also go to the Bight of Benin, where the New Yorkers had fewer connections.Footnote 23 Overall, the plan had merits. It combined the benefits of the biggest ship market in the Americas, the famous protection offered by the US flag, and their allies’ expertise in supplying captives for incoming slavers. The major problem was insecurity on the Cuban end. This weakness was underlined in the early 1850s, when several Portuguese and Brazilian traffickers had attempted to establish themselves on the island but were expelled by successive captain generals. Pezuela’s administration banished two of these individuals, Antonio Severino Avellar and Gaspar de Molta, in early 1854. His agents also chased the Portuguese Antonio Augusto Botelho, who was rumoured to be hiding out in a Cárdenas cane field under the fictitious name Antonio Martínez. The colonial administration eventually expelled all three traffickers, and each one sailed for New York.Footnote 24

The second main group of investors had few such problems in Cuba. They were long-term residents of the island, and exercised impressive local power. Most were wealthy planters and merchants who had profited from Cuba’s nineteenth-century sugar boom and the illegal slave trade before 1850. One important asset was their large estates, which they used to temporarily house newly arrived captives and to conduct illicit slave sales.Footnote 25 Another was their influence over the island’s officials through the distribution of bribes. These payments had been a feature of the Cuban slave trade for decades, but, by the 1850s, traffickers and officials had developed well-honed systems in many parts of the island. In the western jurisdiction of Pinar del Río, for instance, investors and lieutenant governors established a formula that determined the size of bribes based on the number of incoming captives.Footnote 26 At a more distant remove, but no less importantly, Cuban slave traders also maintained strong business and political ties with Spain, offering them logistical and financial support for slaving operations, as well as a degree of protection from Cuban officials who were genuinely committed to suppression.Footnote 27

The island’s most powerful slave trader, Julián Zulueta y Amondo, enjoyed all these advantages. Born into a wealthy mercantile family in Álava, in Spain’s Basque region, in 1814, he emigrated to Cuba in 1832. A few years later, he bought his first plantation in the key sugar-producing province of Matanzas. He subsequently made his base along the expanding sugar frontier in Colón. By the 1860s, he owned four large sugar estates, which boasted highly sophisticated mills, complete with triple-effect vacuum evaporators, centrifuges, and gas lighting. Over 2,000 slaves laboured upon his lands, many of whom had arrived illegally from Africa. Such was Zulueta’s power that his henchmen openly marched one group of captives overland from the coast to one of his estates. His commercial connections and standing in Cuban society permitted such brazen disregard for the law. By the 1860s, he was married to the niece of a powerful Spanish-born slave trader, Salvador Samá y Martí; later in life, after the trade had ended, he was awarded the titles Marques of Álava and Viscount of Casa-Blanca by the Spanish crown.Footnote 28

Cuban investors’ local power and tight connections with Spain contrasted sharply with their weak ties with the African coast. Unlike Portugal, Spain never had a strong foothold in the regions that fed into the slave trade. Even as other powers stepped up their slaving in the eighteenth century, Spain depended on other nations to supply its imperium with captives.Footnote 29 The legacy of that reliance was evident in the 1830s and 1840s, when only a few powerful Havana traffickers such as Pedro Martínez ran slaving establishments on the African coast. In most cases, Cuban traffickers relied on Portuguese, Brazilian, or African merchants to organize shipments on their behalf.Footnote 30 A further limitation was that Cubans enjoyed only restricted access to West Central African captives and had to depend on importations from Senegambia, Sierra Leone, and the Bight of Biafra, where slave prices were higher and embarkations more risky.Footnote 31

Financial records captured by British, Portuguese, and US suppression campaigns show how Cuban and Lusophone traffickers in New York and West Central Africa manipulated the trade’s investment structure to overcome their strategic disadvantages. These sources reveal financial data for 15 of the approximately 353 slaving voyages that set sail after 1850.Footnote 32 This is clearly a small sample, but it is broadly representative of the traffic. Almost every vessel, for instance, embarked from US or Cuban ports, the major departure regions for post-1850 voyages. All but one slaver received captives, or intended to receive them, in West Central Africa, which is generally reflective of the region’s share of embarkations after 1850. Furthermore, all but one of the voyages were destined for Cuba, reflecting the island’s dominance as a disembarkation zone. The fifteen voyages are also spread widely and evenly across the post-1850 trade, meaning that there are at least a handful of cases to analyse from every half-decade up to 1866. (See Table 2 in the appendix for more information on these voyages.)

In thirteen of the fifteen voyages, speculators used an investment model that Emilio Sánchez, a Cuban-born British spy in New York, and an unnamed American spy in Lisbon, described as ‘freighting’.Footnote 33 Under this system, there were two ways to invest. The first was to buy shares in what traffickers called the ‘ship’. These shares funded the operating costs of the voyage such as the purchase of the vessel, repairs, crew wages, and provisions. The second type of investment was in the ‘cargo’. The role of ‘cargo’ investors was to purchase captives and put them aboard the slaver. After the vessel departed from the African coast, it would carry, or ‘freight’, the captives to Cuba, with the ‘cargo’ owners continuing to own them until their arrival in the Caribbean. When the voyage had been completed, a consignee would receive all the captives and pay the voyage manager for the delivery, after deducting bribes and consignee fees. As the consignee proceeded to sell the captives to Cuban planters, the manager would split the profits from the voyage, allocating one half to investors in the ‘ship’ and the other half to investors in the ‘cargo’. One variant of this model was for ‘cargo’ owners to send their own captives to particular consignees in Cuba. In these instances, the various consignees acted for the ‘cargo’ investors, selling the captives on their behalf, and paying fees to the ‘ship’ investors who had funded the transatlantic crossing.Footnote 34 In both cases, therefore, there were investments in the ‘ship’ and the ‘cargo’. In other words, ‘freighting’ was the norm.

‘Freighting’ was not unique to this period of the slave trade, but was ideally suited to it. Unlike much of the British and French trades, especially from the mid eighteenth century onwards, Portuguese, Brazilian, and Spanish traffickers had ‘freighted’ captives extensively during the legal era.Footnote 35 Whereas the British and French usually funded voyages purely in the metropole and bartered for captives on the African coast, the ‘freighting’ model invited traffickers in Africa to purchase captives for voyages. The main advantage of extending ‘cargo’ investment in this way was that it translated into good organization on the African side of the trade. This feature of ‘freighting’ was particularly important with anti-slavery vessels patrolling the coast. Because African traffickers’ capital was also at stake, they were inclined to dispatch slavers as quickly and securely as possible. The bartering alternative, by contrast, was slower and more risky. Traffickers occasionally used additional risk-limiting tactics, such as splitting investments over several voyages and widening investment to include small shareholders, but it seems that the key link was between American-based and African-based traders.Footnote 36

The case of the Restaurador indicates the importance of tying African suppliers to the outcome of a voyage. This vessel journeyed from Cuba to the New Calabar river in the Bight of Biafra in early 1853. Upon his arrival, the Spanish captain, Juan Coll, declared that he would offer no freight, but would exchange his cargo of sugarcane brandy and Mexican gold for captives. Initially, Coll’s plan seemed to be working. He struck deals with several African merchants, handing over the goods and specie in return for promises that the captives would be delivered after twenty days. But these arrangements, which left the merchants with the booty in hand and no stake in the voyage, quickly unravelled. Just a few days later, one of the merchants, Ammacree of New Calabar, informed local white merchants about the slaver in the river. Soon, the news reached the British man-of-war HMS Ferret, which was cruising off the coast. Two weeks into Coll’s wait for the slaves, the British patrol captured him and his ship, causing the voyage to fail completely.Footnote 37

Debacles of this kind encouraged investors in the shipping centres of Cuba and New York to draw on African support via the ‘freighting’ model. In many cases, Cuban ‘ship’ investors joined forces with ‘cargo’ investors in the Bight of Benin. In these instances, vessels typically arrived at Ouidah or Porto Novo, where Portuguese, Brazilians and African traffickers put their captives aboard. Domingo Mustich, a rare Spanish resident of the Bight of Benin, helped with some of these shipments and was himself a supplier of captives.Footnote 38 In other instances, Spanish-registered vessels sailed for West Central Africa. One such slaver, Dolores, brought 595 captives to Cuba in 1855. The ‘cargo’ was almost completely owned by residents of Ambriz and Luanda, the Angolan capital.Footnote 39 In each of these ventures, the Africa-based investors made sure to dispatch the slavers swiftly, while ‘ship’ investors in Cuba wielded their local power to ensure the safe disembarkation and sale of the captives.

New York investors also used the ‘freighting’ model. In most cases they drew heavily on their strong ties with West Central Africa. The voyages of an unnamed brig (1854), the Pierre Soulé (1856), and the Mary E. Smith (1856) all featured investment from both regions.Footnote 40 In each of these examples, a handful of investors, sometimes as few as three, bought up the ‘ship’ shares and dispatched the vessel from the United States. When the vessels reached the slave embarkation point in West Central Africa, ‘cargo’ investors, or their agents, were waiting to put the captives aboard. In a similar way to the Cuba–Africa voyages, local accomplices watched the coast for cruisers, allowing all three ships to escape out into the Atlantic Ocean with hundreds of captives crammed beneath their decks.

Despite its utility on the African side, ‘freighting’ did not erase New York and West Central African investors’ insecurity in Cuba. The case of the Pierre Soulé highlights their vulnerability. In this instance, several of the New Yorkers combined with thirty-five Angola ‘cargo’ investors to bring 467 captives to Cárdenas on the northern coast of Cuba. When José Lucas Henriques da Costa, the voyage manager, arrived on the island, he applied for the prearranged delivery fee but, to his dismay, the Cubans paid far below market rates. With no recourse to the law or to powerful intermediaries on the island, Lucas had to accept US$85,000 for the captives. This sum, he wrote to one of the investors in Angola, caused ‘the whole business [to] suffer a loss of US$48,000’.Footnote 41

While defrauding traffickers in New York and West Central Africa was satisfying for Cuban slave dealers, such chicanery was ultimately counterproductive for Cuban traffickers and for the island’s sugar economy. As the case of the Dolores had shown, Cuban investors needed support in West Central Africa because a large portion of their trade was centred there. Cheating on the Cuban side would only harm their business prospects. Moreover, the island’s planters relied on voyages funded in New York and West Central Africa to meet their growing demand for captives, especially as sugar prices soared in the late 1850s. Lacking both unfettered access to American ships and strong connections with Africa, Cuban traffickers could not satisfy that demand without outside help. New York and West Central African investors may even have underlined their importance to the island’s sugar economy by briefly retreating from the Cuba trade after the Pierre Soulé affair. In the same year, they made one final and futile attempt to revive the traffic to Brazil.Footnote 42

Historically high slave prices in Cuba and the promise of record returns on investment fostered a new spirit of cooperation among speculators in Cuba, New York, and West Central Africa in the late 1850s. Other combinations may have persisted but, strikingly, all three 1858 and 1859 voyages in the fifteen-voyage sample were funded by investors in all three regions. These voyages were made by the Haidee, the Tacony, and the William H. Stewart. Emilio Sánchez, the British spy in New York, described the investment pattern in the first of these voyages, that of the Haidee, which sailed from Manhattan in 1858 (see Table 1).Footnote 43 According to Sánchez, there had been six shareholders in the ‘ship’. Four were Lusophone slave traders in New York and the other two were among Cuba’s wealthiest merchant-planters. On the ‘cargo’ side of the operation, he noted some captives belonged to New York traffickers who maintained slave depots around the Congo river, while West Central African traffickers had sent the others ‘on freight’. The Haidee had therefore enjoyed investment, and logistical support, on every leg of its voyage. Underlining the effectiveness of triple-region funding, Sánchez noted that the ship had brought 903 captives to Cuba and had been a complete success for all investors.Footnote 44

While cooperation boosted all investors’ chances of success, these partners were not equals. The ‘freighting’ system had always rewarded investors in the ‘ship’ more generously than investors in the ‘cargo’. In the case of the Pierre Soulé, the ‘cargo’ investors received returns that were worth little more than the African value of the captives, while the ‘ship’ investors made a profit of 100 per cent.Footnote 45 ‘Cargo’ investors’ dividends would have been much greater had the Cubans not taken advantage of Lucas, but the relative discrepancy between ship and cargo profits would have remained the same. There was logic in that discrepancy, however. ‘Ship’ investors did much of legwork in New York and Cuba, and many took on personal risk by serving aboard slave ships in managerial roles. It therefore made sense that they would be generously rewarded. But when the Cuban speculators joined with the New Yorkers in triple-region voyages, they demanded the greatest spoils while taking the fewest personal risks. In the case of the Haidee, for instance, the Cubans bought up the lucrative ‘ship’ shares without ever setting foot on the vessel, never mind sailing to Africa. Another example of Cuban authority, these arrangements demonstrate that the power players in the illegal slave trade were those who controlled the disembarkation zone.

The greatest challenge to the integrity of the slave trade was not the inequality of their financial arrangements but political action. In 1862, Abraham Lincoln’s Republican administration made several bold moves that changed the landscape of the slave trade. The first step was the appointment of a new federal marshal, Robert Murray, in New York City. Murray made it widely known that his main focus would be to suppress the trade in his jurisdiction.Footnote 46 Lincoln’s government soon followed up this appointment by approving the Lyons–Seward Treaty, which permitted British cruisers to detain American slavers. This move, which was part of Lincoln’s broader strategy to gain Britain’s support during the US Civil War, effectively ended slave traders’ use of US ships.Footnote 47 Finally, Lincoln refused to commute the death sentence of Nathaniel Gordon, a ship captain favoured by the New York investors, who had been sentenced for his role in the voyage of the Erie in 1860.Footnote 48 As he hung upon the scaffold, Gordon became the first US citizen to be executed under the US Act of 1820.Footnote 49 These measures caused the New York traffickers to flee the United States. Scattered to the winds once more, some went to Cuba (whence they were expelled, again), some to Africa, and others to the Iberian peninsula.Footnote 50

Despite the twin losses of New York as a slave-trading haven and the valuable protection of the US flag, the traffic continued for another five years on a diminishing scale. During this period, Spain took a more prominent role in the logistics of the trade. The port of Cádiz became an especially important embarkation point for slavers. In 1862, the New York exiles Antonio Augusto Botelho and José Lima Vianna were key players in dispatching slavers from Cádiz, though they were gradually supplanted by local merchants and shipowners such as Manuel Lloret.Footnote 51 By 1864, Lloret and his allies had made Cádiz, in the words of the British consul Alexander Dunlop, ‘the European centre of the trade’.Footnote 52 If Cádiz led the way, Barcelona and Bilbao were not far behind. Bilbao was particularly favoured by the Basque native Julián Zulueta in Cuba. In 1863, João Soares Pereira, a Portuguese trafficker in the Bight of Benin, wrote to Zulueta, acknowledging that one of Zulueta’s vessels, the Luiza, was on its way from Bilbao, and explaining that he would be waiting with a cargo of ‘oil’ when it arrived. The euphemism hardly required careful deciphering.Footnote 53

As Spanish ports took a greater role in dispatching vessels into the slave trade, their residents increased their financial stake in voyages. While investors in Cádiz, Barcelona, and Bilbao had always had some opportunities to finance illegal slaving voyages, thanks to their ties with Cuban traffickers and the occasional departures from Spanish ports, the growing importance of Spanish shipping after 1861 created additional opportunities. Wealthy merchants with close ties to Cuba were best positioned to invest. The Portillo family of Cádiz became among the most prominent Spanish slave traders in the 1860s, owing, in part, to a business partner in Havana.Footnote 54 Iberian friends of Zulueta also stood to do well. In 1863, a telegram reached Bilbao from Cuba announcing the safe arrival of one of Zulueta’s slavers, the Noc Daqui. It had surely been dispatched to assure nervous investors.Footnote 55

As ties between Cuban- and Spanish-based slave traders grew stronger and the influence of New York faded, the position of investors in West Central Africa also weakened. Now left to deal with the Cubans alone, the most favourable arrangement they could forge was a normal ‘freighting’ arrangement coupled with a prayer that the Cubans would fairly remit the spoils. The 1863 voyages of the Cicerón and the Haydee are two examples of this approach, though, in the latter case, the British intercepted the vessel and no-one made money.Footnote 56 According to Joseph Crawford, the British consul in Havana, some West Central African investors were prepared to make even less favourable arrangements. In 1862, he informed the Foreign Office that ‘desperate’ West Central African traffickers had appeared on the island, ‘offering slaves deliverable at certain points, so very cheap that they are hardly to be resisted’.Footnote 57 This proposal, which entailed shouldering all the risks at sea as well as a heavy discount, was highly unfavourable and reflected the increasingly weak position of West Central African investors as the 1860s wore on.

The slow demise of the slave trade in the 1860s gradually made the changing dynamics of voyage financing irrelevant. An estimated 12,659 captives left African shores in 1862, a number that roughed halved every year until the closure of the trade in 1866.Footnote 58 The cause of this decline was not so much tension between traffickers, but the newfound potency of suppressionist policies within the Spanish empire.Footnote 59 While the illegal slave trade had always had its opponents in Spain and Cuba, the growth of metropolitan liberalism and the capitulation of slavery in the United States between 1861 and 1865 had multiplied and galvanized the critics. American emancipation proved especially influential, convincing many wealthy Cuban planters and Spanish statesmen that slavery in Cuba was now under real threat, and could only be saved if the slave trade was closed. As Cuba’s governor, Francisco Serrano, put it succinctly to his superiors in Madrid, ‘the only means of keeping the one is to finish with the other’.Footnote 60 In 1866 the Spanish government acted on this impulse and imposed new, wide-ranging suppression legislation. It received little resistance in Cuba. After three and a half centuries, speculating in the slave trade was finally over.Footnote 61

Circulating capital

Pooling ‘ship’ investments

The illegal slave trade’s disparate investment sources required speculators to discreetly move large amounts of capital over long distances. One major transfer was the pooling of funds in outfitting ports such as New York. This capital covered the purchase of the vessel and provisions for the voyage, as well as other shipping expenses. According to the ‘freighting’ model, it was the responsibility of ‘ship’ investors to cover these costs. The problem was that many voyages’ ‘ship’ investors did not reside in the vessel’s outfitting port or retain credit with their distant associates.Footnote 62 As a result, they often had to send capital on long-distance, border-crossing journeys before it could be put to use. Doing so was both technically challenging and risky. On the technical side, speculators had to ensure that they issued funds in forms that were redeemable at their destination, as well as inexpensive to transport and retentive of their value during transit. The major hazard was that officials might seize investors’ capital as it passed through their jurisdictions. With thousands of dollars on the move, steering capital into position was therefore a potentially complicated and high-stakes endeavour.

Emilio Sánchez, Britain’s spy in New York, understood this process better than most observers. In 1859, he penned a letter to his handler, the British consul, Edward Archibald, describing the ‘ship’ investments in the voyage of the Haidee. The 325-ton vessel had departed from New York the previous year, and eventually disembarked around nine hundred Angolan captives at Cárdenas.Footnote 63 According to Sánchez, the voyage had six ‘ship’ investors. Two were the Basque Julián Zulueta and a Galician, José Plá. Like Zulueta, Plá was an immigrant who had risen to become a major sugar planter, enslaver, and merchant in Cuba.Footnote 64 The other four investors were Portuguese and Brazilians in New York. Some were full-time traffickers, while others were part-time import/export merchants. Between them, the six investors sank US$27,000 into the Haidee’s voyage. Individually, the sums ranged from Zulueta’s US$8,000 stake to Antonio Augusto Botelho’s US$2,500 (see Table 1).

Sánchez’s letter detailed the international odyssey of the investors’ capital. It began when Botelho travelled to Cuba. During his brief visit (he had been expelled from the island in 1854), he collected a combined US$12,000 from Zulueta and Plá. The merchant-planters issued the funds in two forms, a US$5,000 bill of exchange, and the rest in Spanish gold doubloons. Sánchez did not say what Botelho did with the doubloons upon his return to New York, but he probably used them to help purchase the Haidee, which soon became the property of Inocêncio Abranches, another of the Portuguese investors in Manhattan. He did note that Botelho presented the bill of exchange to Juan M. Ceballos, a merchant banker of Cantabrian origin. According to Sánchez, Ceballos readily accepted the bill and used it to buy 1,000 barrels of flour on Botelho’s behalf. The Portuguese then had the flour loaded onto the Haidee, which he cleared for Cádiz. When they arrived in Spain, Botelho sold the flour, and had one of the Haidee’s yardarms repaired. Soon they set off again for the British Crown Colony of Gibraltar, where Botelho bought large amounts of rice and beans. After returning once more to Cádiz for bread, water, and further fittings, the Haidee finally set sail for the Loango Coast. Two months later, its crew was cramming 1,100 West Central Africans beneath its decks. Two hundred captives would perish during the transatlantic crossing to Cuba.Footnote 65

Through these twists and turns, the Haidee investors overcame the logistical and suppressionist challenges of the illegal slave trade, shifting capital from the Caribbean through North America and Europe to Africa with apparent ease. At the beginning of the affair, Zulueta and Plá had issued part of their investment in gold doubloons, a form of capital that was both readily available to wealthy merchants in Havana and welcomed by traders in New York.Footnote 66 Similarly, the bill of exchange was safe and convenient to transport, and, in the hands of Juan Ceballos, a leading merchant banker in New York, not at all suspicious. By turning the bill into flour in New York, Ceballos hid slave trade capital in about as dull a commodity as New York could muster. In Cádiz, Botelho seems to have turned the flour into an innocent repair job on his ship. He had exposed the voyage to suspicion and the investors’ capital to seizure when he bought large quantities of food, but his discretion (or possibly his bribes) was sufficient to get the Haidee out of Europe and on its way to Africa.Footnote 67

The Haidee investors and their allies had planned each step carefully, but they were also exploiting the broader opportunities offered by the structural changes in Atlantic world economy during the nineteenth century. The most significant of those changes, the liberalization of trade, had effectively opened up the laundering routes. Freer trade between Spanish jurisdictions and the United States was especially germane. When Zulueta and Plá sent their bill and gold to Ceballos, they were relying on a relationship built upon the booming Havana–New York sugar trade. This traffic had grown steadily since Spain had opened Cuba to foreign commerce in the late eighteenth century. By 1858, when the Haidee’s voyage took place, the United States had surpassed the Iberian power to become Cuba’s largest trading partner.Footnote 68 Zulueta, Plá, and Ceballos, who were major investors and launderers in the voyage, were among the biggest legal traders plying the Havana–New York nexus.Footnote 69

The relatively new but rapidly growing trade between the US and Spain was another important context.Footnote 70 When the Haidee docked in Cádiz in 1858, it joined a stream of vessels arriving from every major port east of the Mississippi river.Footnote 71 New York merchants, including Sánchez, sent goods to Cádiz, and it is likely that, during his long career as an overseas trader, Ceballos did likewise.Footnote 72 As a merchant of Spanish origin, he would certainly have known that Cádiz was a major gateway to the Iberian peninsula, and that Botelho would find a good market for American flour in its port. As his role in the Haidee demonstrates, he had no qualms working with slave traders, and understood intimately how global commerce dovetailed seamlessly with the slave trade.

Buying human cargo

The traffic’s second major capital flow involved ‘cargo’ investors. These speculators were concentrated in the major slave embarkation zones, West Central Africa and the Bight of Benin. After 1850, around 157,000 and 34,000 captives respectively departed from these shores, from a total of around 226,000.Footnote 73 Most ‘cargo’ investors were emigrants from Portugal and Brazil, such as the Brazilian-born Guilherme José da Silva Correia, who operated on the Congo river. A few were Africans, such as the powerful Angolan trafficker Dona Ana Joaquina dos Santos e Silva.Footnote 74 The main task of these traffickers was to purchase interior captives for incoming slavers. To do so, they had to navigate not only shifting local and regional African politics but also the consumer preferences of inland suppliers. As Daniel Domingues da Silva has recently shown, West Central Africans demanded an assortment of foreign goods, including European textiles, firearms, and alcohol, in exchange for slaves.Footnote 75 Sellers in the Bight of Benin, by contrast, required tobacco from Bahia in Brazil.Footnote 76

These trade requirements forced coastal investors to access overseas markets. Some speculators, such as Domingos Martins, did so by importing slave-trading goods themselves. A native Bahian, Martins had immigrated to Porto Novo in the Bight of Benin in 1846, and later moved along the coast to Ouidah. Despite his long-distance migration to West Africa, Martins retained strong connections with Bahia through property, family, and business partners.Footnote 77 By the 1850s, he was reportedly importing 80 per cent of all Bahian tobacco and alcohol entering the Bight of Benin.Footnote 78 After several large shipments arrived from Bahia in 1854, Benjamin Campbell, the British consul at Lagos, reported that Martins had 8,000 rolls of tobacco in store and was ready to deploy them inland for captives.Footnote 79 As Robin Law has noted, Martins also drew goods from Britain, and offered some items to Ghezo, the King of Dahomey, as gifts.Footnote 80 Having placated the most powerful ruler in the Bight of Benin, and with tobacco streaming in from Bahia, Martins was able to become, in Campbell’s estimation, one of the ‘principal shippers of slaves’ in the region.Footnote 81

‘Cargo’ investors followed a similar strategy in West Central Africa. One of the key slave traders in this region was Francisco António Flores.Footnote 82 Also a native of Brazil, Flores immigrated to Angola in the 1840s and made his home in Luanda. Having been heavily engaged formerly in the slave trade to Brazil, he was one of the colony’s leading traffickers with Cuba in the first half of the 1850s. A core plank of Flores’ business was importing cloth, firearms, and gunpowder from Portugal and Britain, and sending them up-country for captives.Footnote 83 The explorer David Livingstone discovered a little about the passage of these goods in 1855. He was at Golungo Alto, 120 miles east of Luanda, and had stumbled across a trafficking case that local merchants claimed Flores had orchestrated. According to Livingston, the colonial authorities had captured a ‘driver or agent … with a company of slaves for exportation’.Footnote 84 A ferryman claimed that he had spotted the driver on his way down to the coast with thirty-six captives, and had previously witnessed him ‘going up the country to purchase them [with] cloth sufficient to buy a great many more than that’. Local merchants had assured the Scot that, had the captives not been intercepted, they would have travelled down to Flores’ base in Luanda, ‘round to Ambriz … in launches’, and aboard a slaver to Cuba.

Flores and Martins were not the only merchants to draw slave-trading goods to the African littoral. Merchants engaged in legal commerce were among the investors’ greatest allies in the Bight of Benin and West Central Africa in the mid nineteenth century. Consul Campbell in Lagos reported one incident to the Foreign Office in 1854. According to Campbell, a local trader, Jambo, had recently imported roll tobacco from Bahia. Although Jambo was seemingly not directly invested in the slave trade, the consul noted that ‘the greater part of [the tobacco] has been bought by the woman Tiunaboo on credit, and, tis strongly suspected, is to be paid for in slaves forwarded to [Domingos Martins at] Whydah’.Footnote 85

Like Jambo in the Bight of Benin, British, Portuguese, US, French, and Dutch firms sold slave-trading goods on the coast of West Central Africa. As the historians David Eltis and Marika Sherwood have shown, British manufactures were particularly important in the nineteenth-century slave trade, well after British abolition in 1807.Footnote 86 The Governor of Angola, Sebastião Lopes de Calheiros e Meneses, made this point to Edmund Gabriel in Loanda in 1862. He complained that English vessels were importing the ‘greater part’ of manufactures driving the slave trade on the Congo river. British powder, arms, and other goods, he argued, ‘contribute, at present, more than any other … to attract the negroes from the interior, who bring down and sell slaves at the points where these goods can be obtained’.Footnote 87 Although Gabriel rejected Lopes’ claims, senior British officials privately conceded the point. Just a few months before Lopes penned his complaint, the prime minister, Lord Palmerston, had written privately to William Henry Wylde, head of the Slave Trade Department at the Foreign Office, instructing him to ‘communicate with the British shareholders of the packets [delivering slave-trading goods to Africa] and … point out to them that whether legally guilty or not they are morally guilty of slave trade’.Footnote 88

Palmerston’s remark highlights the ways in which the broad structures of the global economy supported the illegal slave trade, and the tension between Britain’s ‘free trade’ ideology and slave trade suppression. Officially, the British government’s perspective was that ‘free trade’ was helping to destroy the traffic on the African coast.Footnote 89 Many Portuguese policymakers and writers shared this position, arguing that more open trade was putting Angola’s economy on a new footing after generations of intensive slave exporting.Footnote 90 In practice, however, ‘free trade’ inevitably mixed what the British considered ‘legitimate’ and ‘illegitimate’ commerce, and indirectly offered substantial assistance to the slave trade. Not only did it enable coastal traffickers to draw slaving goods to Africa, and encourage inland suppliers to send slave captives down to the coast, but it also invited the agents of European firms, the idealized agents of reform, to become the traffic’s great accomplices.

The wages of sorrow

The third major capital flow was that of the post-voyage remittances. Records from the voyage of the Pierre Soulé show how investors, merchants, and bankers combined to distribute the dividends. In this case, investors had run the voyage along traditional freighting lines. The ‘ship’ shareholders appear to have been the Lusophones in New York, since it was one of their number, José Lucas, who managed the voyage’s affairs in the Americas. The ‘cargo’ speculators were thirty-five residents of southern Angola, where the slaver had received 479 captives late in 1855 (see Table 3 in the appendix).Footnote 91 This geographic distribution of investors meant that the dividends had to circulate between Cuba, the United States, and Angola before everyone would receive their share.

Lucas initiated the process of laundering and circulating the returns in Havana shortly after the Pierre Soulé made landfall at Cárdenas. First, he contacted the consignee, the Havana merchant Justo Mazorra, who eventually agreed to pay him US$85,000 in drafts and specie.Footnote 92 The records from this case do not explain precisely how Mazorra made the payment, but they do disclose that he engaged two Havana merchant bankers, Martín Riera and Nicolás Martínez Valdivieso, to help with the transaction. Both Riera and Martínez were influential figures in Banco Español (Spanish Bank), which had been established under royal charter in Havana the previous year.Footnote 93 Riera was the bank’s subdirector, the second most senior position, while Martínez was a consejero (board member).Footnote 94 According to the bank’s charter, two of its main roles were to deal in bills of exchange and to issue specie. In fact, it was the only institution on the island to hold the latter responsibility.Footnote 95 While it is unclear whether Riera and Martínez used their influence in Banco Español to help issue Mazorra’s payment, the bank was certainly uniquely equipped to do so. The island’s governor, Domingo Dulce, certainly believed that there was a connection between the bank and the slave trade. In an 1863 letter to Madrid, he identified several Portuguese traffickers who had recently taken up residence in Cuba and specifically mentioned their shareholdings in the bank as a point of suspicion.Footnote 96

The specie and gold that Lucas carried back to New York was part of a broader current of slave trade remittances travelling north from Cuba. Several traces of this flow emerge from merchants’ papers, spy reports, and newspaper columns. The correspondence of the New York sugar importer Moses Taylor shows that, in 1854, Drake Bros., an Anglo-Cuban merchant house in Havana, issued two bills of exchange worth a total of US$12,000 in favour of José Lima Vianna, a Portuguese trafficker with no business in Cuba except the slave trade. Vianna carried the bills to Henry Coit, a sugar merchant in New York, who endorsed the bills and released the funds.Footnote 97 According to Emilio Sánchez, the notorious Cunha Reis travelled the same route in the winter of 1858, carrying a massive US$60,000 in drafts from the voyage of the Panchita.Footnote 98

It was also common for traffickers to step off the Havana steamer lugging boxes of specie. In 1860 the New York Times noted that Vianna had recently brought home a box of specie worth US$7,650 from Havana. Incriminatingly, this listing appeared just above an article from the paper’s Cuba correspondent wherein he claimed he was in possession of ‘proof strong as holy Writ’ that six to eight thousand enslaved Africans had arrived in the island during the previous weeks.Footnote 99 In other cases, investors received remittances in commodities. During the Mary E. Smith affair, the final, unsuccessful attempt to bring captives to Brazil in 1856, Cunha Reis in New York wrote to the shipboard manager João José Vianna, explaining: ‘I want to have my share [of the profits] here, for which purpose the Isla de Cuba is to go [to Rio de Janeiro] and come with coffee’.Footnote 100

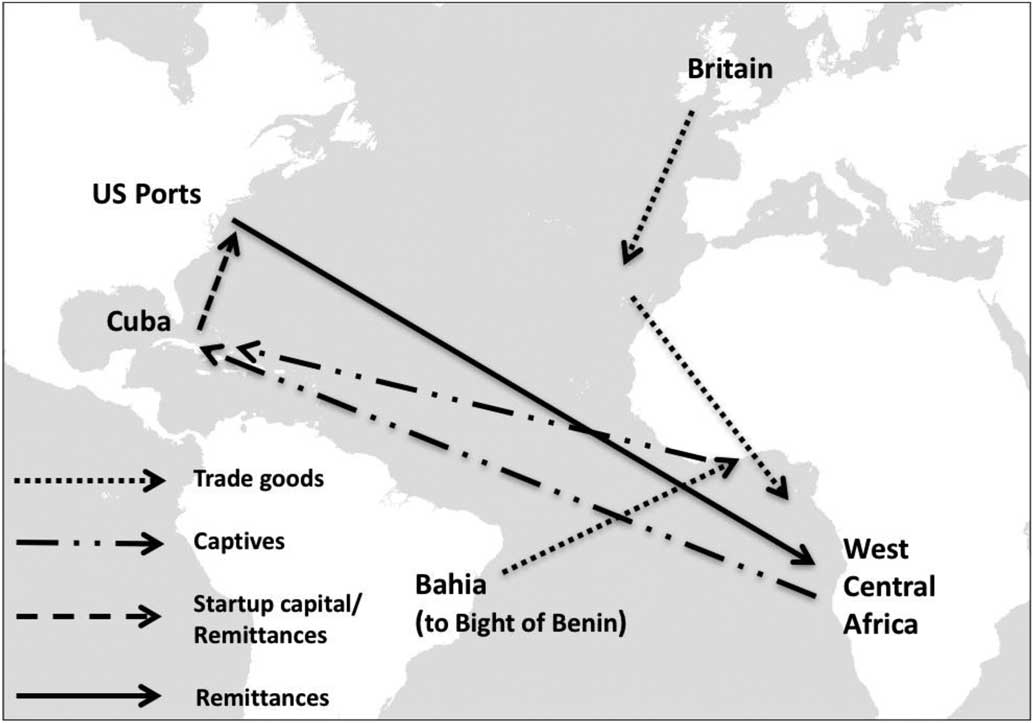

The trans-American journey was only one leg on the long passage of slave trade remittances. Returns from illegal voyages flowed into New York, but some also flowed out to ‘cargo’ investors in Africa. In the case of the Pierre Soulé, Lucas sent the dividends through João Alberto Machado, a Portuguese-born Africa trader in New York.Footnote 101 In the summer of 1856, Machado dispatched the schooner Flying Eagle from New York to southern Angola with a legal trading cargo worth US$30,000 and 432 gold doubloons. He consigned most of the goods to João Soares of Novo Redondo, who had sent forty-eight captives aboard the Pierre Soulé. Two months later, the vessel arrived safely in Benguela. Soares was about to take his portion and distribute the rest to the others when the Portuguese authorities launched a surprise raid on his home. After searching his residence and discovering his incriminating correspondence with Lucas, they immediately seized the Flying Eagle’s cargo and gold. In most cases, slave trade capital moved around the Atlantic world with impunity, as depicted in Figure 2. On this occasion, at least, the circuits were broken.

Figure 2 Major flows of captives and capital in the illegal transatlantic slave trade, 1850–66.

Conclusion

Voyages such as the Pierre Soulé’s were made possible by the ability of far-flung capitalists to form mutually beneficial partnerships. ‘Ship’ and ‘cargo’ investors such as Zulueta, Cunha Reis, and Flores were the key figures. From their plantations and offices in Cuba, New York, West Central Africa, and elsewhere, they reached across the Atlantic world, forging alliances, pooling capital, and attempting to counter the risks from suppression. These relationships were inequitable and sometimes unstable, but they proved lucrative and reliable enough to keep capital flowing into the trade, and ships journeying to the slaving coasts of Africa, for a decade and a half. To help investors move capital into position, they recruited a remarkably international field of capitalists, including officeholders in Havana’s Banco Español, sugar barons in New York, and British merchants on the Congo river. As experienced international traders, they knew exactly how to hide and transmit slave trade capital within legal international commerce, and to exploit the inconsistencies of trade liberalization.

Slave trade investors and their allies were creatures of a rapidly globalizing world. Many traffickers migrated vast distances on several occasions to continue their work. Each of the leading figures forged international trading networks, kept a close eye on world markets for sugar and slaves, and used new technologies such as steamships and the telegraph to conduct their business. No-one better embodied the global character of slave traders and their world than the Portuguese Cunha Reis. By the close of the slave trade in the 1866, he had been an active trafficker in Brazil, West Central Africa, the United States, and Cuba, spinning webs that crisscrossed the Atlantic basin many times over. In the early 1860s, he bought land in Cuba and, with the help of victims of the slave trade, began growing cotton.Footnote 102 Typically of Cunha Reis, it was an enterprise dependent on human exploitation and geared to global markets. His plan was to capitalize on high world cotton prices and the collapse of production in the American South during the Civil War.Footnote 103 A few years later, he was in Mexico, speculating in railroads and trying to recruit contract labourers from China.Footnote 104 These endeavours also bore his hallmarks: high-stakes investment, unfree migration, and transnational thinking. His purview was always global and never paid respect to human costs.

Anti-slave trade forces could not defeat Cunha Reis and his associates until suppression became as global as the traffic itself. In the 1860s, crackdowns on the trade, most notably in the US and in Cuba, finally plugged gaping holes in the suppressionist wall. These measures effectively raised the risk of voyages to the point where traffickers were unprepared to send their ships to sea. They did not, however, specifically tackle the circulation of slave trade capital, a problem even the British had failed to systematically address for half a century. The flow of slave trade capital through commercial circuits nevertheless drained away when states made it too risky for traffickers to continue their work. Slavery would endure in many parts of the Atlantic basin for a generation or more, but the transatlantic slave trade, and the capital flows that supported it, had finally been extinguished.

John Harris is a PhD candidate at Johns Hopkins University. His research explores slavery and abolition in the nineteenth-century Atlantic world, with particular emphases on the United States and the illegal transatlantic slave trade.

Appendix

Table 2 Vessels for which investment data is available in British and US state suppression archives, personal papers, newspapers, and secondary works.

Table 3 ‘Cargo’ account of the Pierre Soulé.