INTRODUCTION

Elasmobranchs are among the top predators in marine environments and have an important role in marine ecosystems in relation to both fish and lower trophic level invertebrate populations (Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Pawson and Shackley1996). In spite of the value of understanding the feeding relationships in food web dynamics, community conformation and the energy transfer in marine systems, knowledge of the dietary ecology of most elasmobranchs is poor. This applies particularly to batoids, which have received considerably less scientific attention than pelagic sharks (Bizarro et al., Reference Bizarro, Robinson, Rinewalt and Ebert2007). Indeed, of the 245 species of skate described, fewer than 24% have had any quantitative dietary information published. There are many reasons why quantitative analyses are few. One is the lack of adequate systematic knowledge of the group. Another is the lack of financial resources to study either non-target species or species of low economic value. Yet another is that skates often live in habitats difficult to get at (Ebert & Bizarro, Reference Ebert and Bizzarro2007).

The skates, as important predators and ground-fish competitors, have a significant impact on the benthic fauna, playing an essential role in structuring benthonic–demersal marine communities (Ebert & Bizarro, Reference Ebert and Bizzarro2007; Treloar et al., Reference Treloar, Laurenson and Stevens2007). Even though the skates' diet is determined largely by ontogenetic mechanisms, it is also influenced by environmental factors. Hence, it is important to identify those factors in order to evaluate the diet variation in terms of the environment (Jaworski & Ragnarsson, Reference Jaworski and Ragnarsson2006). Factors such as body size, maturity stage, sex, season, bottom depth, region, habitat mobility, seasonal occurrence, potential prey abundance and distribution, as well as ecomorphology, are among potential factors influencing skate diets (Jaworski & Ragnarsson, Reference Jaworski and Ragnarsson2006; Treloar et al., Reference Treloar, Laurenson and Stevens2007).

Ontogenetic dietary changes have been analysed in skates (Bizarro et al., Reference Bizarro, Robinson, Rinewalt and Ebert2007; Barbini, Reference Barbini2011), since the predator size is one of the main causes behind diet composition changes during ontogeny (Lucifora et al., Reference Lucifora, García, Menni, Escalante and Hozbor2009). Moreover, differences in feeding behaviour between sexes have been also found in some species (Orlov, Reference Orlov1998; San Martín et al., Reference San Martin, Braccini, Tamini, Chiaramonte and Perez2007).

Amblyraja is a circumglobal genus, even though it most often is found at high latitudes and deep waters (McEachran & Miyake, Reference McEachran, Miyake, Pratt, Taniuchi and Gruber1990; Ebert & Compagno, Reference Ebert and Compagno2007). It is composed of ten species, one of which, Amblyraja doellojuradoi, inhabits the south-west Atlantic (Menni & Stehmann, Reference Menni and Stehmann2000; Cousseau et al., Reference Cousseau, Figueroa, Díaz de Astarloa, Mabragaña and Lucifora2007). Off the coast of Argentina it is distributed from 36° to 55°S along the outer shelf and the continental slope (80–600 m depth). Information about A. doellojuradoi is scarce and refers almost exclusively to taxonomy and distribution (Pozzi, Reference Pozzi1935; Bellisio et al., Reference Bellisio, López and Torno1979; Menni et al., Reference Menni, Ringuelet and Aramburu1984; Menni & Stehmann, Reference Menni and Stehmann2000; Sánchez & Mabragaña, Reference Sánchez and Mabragaña2002; Cousseau et al., Reference Cousseau, Figueroa, Díaz de Astarloa, Mabragaña and Lucifora2007). The exception is a paper published by Sánchez & Mabragaña (Reference Sánchez and Mabragaña2002) where, on the basis of few specimens, the diet of A. doellojuradoi was evaluated. They found that this species feeds mainly on crabs and, in a lesser proportion, on fish and polychaetes. Regarding the information on industrial fishing, A. doellojuradoi is considered a rare species (Colonello et al., Reference Colonello, Massa and Lucifora2002).

The aim of the present work is to study the trophic aspects of A. doellojuradoi on the Argentine Continental Shelf. The specific objectives are to evaluate potential differences by sex, size, maturity stage, latitude and depth in feeding ecology. This study provides the first detailed contribution on the food habits of A. doellojuradoi in an extensive area of the south-west Atlantic in order to understand the role of the species in the regional food web.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area and sampling

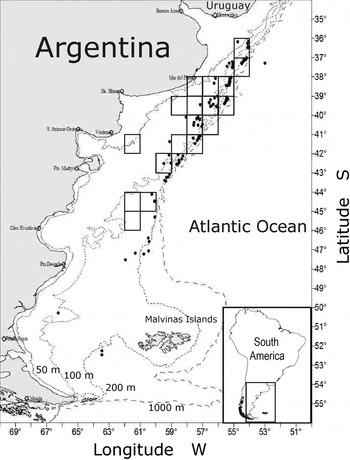

Skates were collected from research cruises carried out by the Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo Pesquero (INIDEP) (N = 167), and from commercial vessels (N = 102) between the years 2005 and 2012 in the south-west Atlantic between 36° and 50°S, from 75 to 414 m deep (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Map of the study area showing positions of trawl stations and cells of fishing grid (black rectangles) where specimens of Amblyraja doellojuradoi were captured.

Total length (TL) was measured to the nearest millimetre, and sex and maturity stage were recorded by macroscopic observation of the reproductive organs (Mabragaña et al., Reference Mabragaña, Lucifora and Massa2002; Colonello et al., Reference Colonello, García and Lasta2007). The immature specimens were characterized by thin uteri, ovaries without visible oocytes, oviductal glands not fully developed in females; thin and straight spermatic ducts, underdeveloped testes and not calcified claspers in males. In contrast, mature females evidenced enlarged uteri, ovaries with vitellogenic oocytes, oviductal glands fully formed and possible presence of fully or partially formed egg-case; mature males showed meandered epididymides tightly filled with sperm, testes with vitelline vesicles and calcified claspers (Mabragaña et al., Reference Mabragaña, Lucifora and Massa2002; Colonello et al., Reference Colonello, García and Lasta2007). The stomachs were dissected, labelled and fixed in 10% formaldehyde. In the laboratory, prey items were identified to the lowest possible taxonomic level using identification keys (Bastida & Torti, Reference Bastida and Torti1973; Menni et al., Reference Menni, Ringuelet and Aramburu1984; Boschi et al., Reference Boschi, Fischbach and Iorio1992; Cousseau & Perrotta, Reference Cousseau and Perrotta2000), illustrative guides and information from specialists. The numbers and weights of every prey item were recorded.

Analysis of diet

DIET COMPOSITION

In order to quantify the diet composition and its comparison with published studies, percentage by weight (%W), percentage by number (%N) and percentage of frequency of occurrence (%F) were calculated. From these values the index of relative importance (IRI = %F(%N + %W)) was estimated (Pinkas et al., Reference Pinkas, Oliphan and Iverson1971) and then expressed as a percentage value (%IRI, Cortés, Reference Cortés1997). For statistical purposes, prey items were grouped into six categories: teleosts, crabs, isopods, other crustaceans (other decapods, gammarids, cumacea and mysidacea), polychaetes and other invertebrates (pycnogonids, cephalopods, sipunculids, asteroids, hydrozoans and ophiuroids). The variables considered in assessing the consumption of different prey categories were: TL, sex, maturity stage (immature and mature), and longitude and latitude as geographical variables. Latitudinally, the study area was divided into a northern region from 36° to 43°S and a southern region from 43° to 50°S. Since the depth of capture of the totality of specimens was unknown, the geographical variable longitude was considered to supply missing data. In agreement with the spatial layout of the Argentine coast, as the geographical variable longitude decreases from 69° to 51°W, the platform depth increases.

The minimum number of stomachs needed to describe the diet of each group of individuals considered, was assessed using cumulative diversity curves (Magurran, Reference Magurran2004). In order to minimize bias, the order in which stomachs were sampled was randomized 100 times. Then, the cumulative number of stomachs sampled at random was plotted in relation to the average cumulative diversity index of the stomach contents. Where the average value of the diversity index (Shannon–Wiener) reached an asymptote, the sample size was considered sufficient to describe the dietary composition of the group of individuals considered.

DIET SHIFTS

By means of a multiple hypothesis modelling approach (Franklin et al., Reference Franklin, Shenk, Anderson, Burnham, Shenk and Franklin2001), variations in consumption of prey categories in terms of sex, maturity stage, TL, the geographical variables longitude (depth) and latitude (taking into account both the northern and southern regions) were evaluated. For each prey category, generalized linear models were built where the number of each prey category was taken as the response variable, and sex, maturity stage, TL, deepness and regions as the explanatory variables (Venables & Ripley, Reference Venables and Ripley2002). A model with no independent variables (null model) was also fitted to test the hypothesis that no one variable had an effect on the consumption of each prey category (Lucifora et al., Reference Lucifora, García, Menni, Escalante and Hozbor2009). Furthermore, models were made with combinations of some of the variables: sex and TL, sex and depth, sex and regions, sex and maturity stage, TL and depth, TL and regions, TL and maturity stage, depth and regions, maturity stage and depth, maturity stage and regions. Whenever too many zeros were present and the variance was often much greater than the mean, models with prey number as the response variable had a binomial error distribution and a log link (Crawley, Reference Crawley2005). For each prey category, the Akaike information criterion (AIC) of all models considered was calculated. The AIC indicates the amount of information lost in each model fit; therefore, the model with the lowest value of AIC was the one that best described the data (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Burnham and Thompson2000; Franklin et al., Reference Franklin, Shenk, Anderson, Burnham, Shenk and Franklin2001; Johnson & Omland, Reference Johnson and Omland2004). Each model was weighed against the others using the Akaike weights (w) which give an estimation of the likelihood of the model (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Burnham and Thompson2000; Franklin et al., Reference Franklin, Shenk, Anderson, Burnham, Shenk and Franklin2001; Johnson & Omland, Reference Johnson and Omland2004).

RESULTS

Diet composition

Of 306 specimens examined, 269 (87.9%) contained food, 158 of which were males (209–710 mm TL) and 111, females (275–515 mm TL). Cumulative curves reach the asymptote diversity in all specimens with 84 stomachs, with 60 and 96 in females and males, respectively, with 20 in immature and 117 in mature, and finally with 131 stomachs in the northern area and 24 in the southern area (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Curves of cumulative mean diversity (Shannon–Wiener index) for each group of specimens considered for the dietary analysis of Amblyraja doellojuradoi. Mean, continuous line; standard deviation, dashed lines.

A total of 53 different prey items were identified in the Amblyraja doellojuradoi stomachs (Table 1). The most important prey in terms of %IRI were crabs (85.47%); less important were polychaetes (4.71%), isopods (1.89%), other crustaceans (1.39%), other invertebrates (3.00%) and teleosts (3.51%). Among the crabs, Libidoclea granaria was the most consumed species, followed by remains of brachyuran crabs and Peltarion spinulosum.

Table 1. Diet composition of Amblyraja doellojuradoi. %N, percentage by number; %W, percentage by weight; %F, percentage frequency of occurrence; IRI, index of relative importance; %IRI, percentage of IRI.

Diet shifts

The consumption of prey categories presented some changes depending on variables such as total length, sex, maturity and regions (Table 2). As the A. doellojuradoi body size rose, the number of crabs consumed increased and consumption was higher in the northern than in the southern region (Figure 3A). The polychaetes consumption decreased as specimens gained size, and it was higher in immatures than in matures (Figure 3B). Females of A. doellojuradoi consumed more isopods than males, and that consumption was higher in the southern than in the northern region (Figure 3C; Table 2). On the other hand, immatures fed more on the ‘other crustaceans’ prey category, and consumption was also higher in the southern region (Figure 3D). The consumption of other invertebrates decreased in number as A. doellojuradoi increased in size (Figure 3E). Finally, feeding on teleosts was determined by the sex variable, showing females having higher consumption than males, and that consumption was higher in the southern than in the northern region (Figure 3F; Table 2).

Fig. 3. Shift in consumption of different prey categories of Amblyraja doellojuradoi in the Argentinean Continental Shelf in function of the total length, sex, latitude and longitude, estimated by a generalized linear model: (A) shift in consumption of crabs in function of the total length and regions (north: solid line and solid circles; south: dotted line and open circles); (B) shift in consumption of polychaetes in function of the total length and maturity (mature: solid line and solid circles; Immature: dotted line and open circles); (C) shift in consumption of isopods in function of sex and regions (north: black; south: white); (D) shift in consumption of other crustaceans in function of the maturity and regions (north: black; south: white); (E) shift in consumption of other invertebrates in function of the total length; (F) shift in consumption of teleosts in function of sex and regions (north: black; south: white). The models had a log link and a negative binomial error distribution.

Table 2. Best models explaining the consumption in number of prey categories of Amblyraja doellojuradoi. The intercept and coefficient for the variables are given. TL, total length (mm); AIC, Akaike information criterion; w, Akaike's weights; standard errors in parentheses.

DISCUSSION

Since it fed mainly on crabs, polychaetes and bottom fish, Amblyraja doellojuradoi evidenced benthic feeding habits on the Argentine Continental Shelf.

In addition, it was clear that this species was capable of capturing benthic–demersal prey items like Merluccius hubbsi and Patagonotothen ramsayi, although not main components of the skate diet. Of minor significance were polychaetes, represented by errant and sedentary worms. Crustaceans and fish constituted the most important prey items of the region, observed in the majority of skates (García de la Rosa & Sánchez, Reference García de la Rosa and Sánchez1999; Koen Alonso et al., 2001; Brickle et al., Reference Brickle, Laptikhovsky, Pompert and Bishop2003; Mabragaña & Giberto, Reference Mabragaña and Giberto2007; Belleggia et al., Reference Belleggia, Mabragaña, Figueroa, Scenna, Barbini and Díaz de Astarloa2008). Even though A. doellojuradoi consumed a great variety of prey, it showed a specialized consumption of crabs, and therefore is carcinophaga in its feeding habits.

Sánchez & Mabragaña (Reference Sánchez and Mabragaña2002) found that the diet of A. doellojuradoi in Patagonian waters was dominated by crustaceans, and occasionally by fish, polychaetes and molluscs. Besides, Bizikov et al. (Reference Bizikov, Arkhipkin, Laptikhovski and Pompert2004) in the Malvinas (Falkland) Islands reported for the early stages a diet based mostly on euphausids, shifting, close to adulthood, to isopods and polychaetes, as well fish and other benthic prey items. The results of the present work showed that the most important prey was crabs, while the less important were polychaetes, other invertebrates and teleosts. Also, in agreement with Bizikov et al. (Reference Bizikov, Arkhipkin, Laptikhovski and Pompert2004), a dietary shift was evident in A. doellojuradoi. Smaller individuals consumed chiefly polychaetes, isopods and other invertebrates, and larger individuals consumed mostly crabs. Differences between the diet reported by Bizikov et al. (Reference Bizikov, Arkhipkin, Laptikhovski and Pompert2004) and the one here stated result from difference of the sampling areas. It is well known the significance of krill as an abundant resource in the Malvinas Islands (Volkman et al., Reference Volkman, Presler and Trivelpiece1980; Main & Collins, Reference Main and Collins2011); thereby, the skates of smaller size are better able to capture these prey items. The consumption of krill has not been reported by other authors.

Some species of the genus Amblyraja, such as A. radiata, were studied in detail. The diet of this species was studied by Skjæraasen & Bergstad (Reference Skjæraasen and Bergstad2000) in the Norwegian Sea, Norway, and Pedersen (Reference Pedersen1995) in the Davis Strait, Greenland. The first authors found fish, decapods and polychaetes in the diet, and the second one, copepods, gammarids, mysids and squid. Another species of the genus with known dietary habits is A. georgiana of South Georgia, which when young feeds on amphipods and polychaetes and when it matures, on fish (Main & Collins, Reference Main and Collins2011). Bizikov et al. (Reference Bizikov, Arkhipkin, Laptikhovski and Pompert2004) found that A. georgiana of the Malvinas Islands preyed on fish, shrimps, crabs and squids. As discussed so far, it can be concluded that Amblyraja is a genus that feeds mainly on fish and crabs, but does not exclude other prey items from its diet. In addition, it appeared that this genus also undergoes ontogenetic shift in its diet.

Amblyraja doellojuradoi showed changes in diet composition between sexes, with increasing body size, maturity stage, and also between regions (northern–southern). Ontogenetic changes in diet composition had been reported in several studies of skates, in different parts of the world including those skates that inhabit the Argentine Continental Shelf (McEachran et al., Reference McEachran, Boesch and Musick1974; Pedersen, Reference Pedersen1995; Lucifora et al., Reference Lucifora, Valero, Bremec and Lasta2000; Skjæraasen & Bergstad, Reference Skjæraasen and Bergstad2000; Kohen Alonso et al., Reference Kohen Alonso, Crespo, García, Pedraza, Mariotti, Beron Vera and Mora2001; Brickle et al., Reference Brickle, Laptikhovsky, Pompert and Bishop2003; Belleggia et al., Reference Belleggia, Mabragaña, Figueroa, Scenna, Barbini and Díaz de Astarloa2008; Barbini, Reference Barbini2011). According to Jaworski & Ragnarsson (Reference Jaworski and Ragnarsson2006) the size of the skates is the most important variable in determining the composition of their diet. Most of the observed changes in several skates were from crustaceans to fish (Orlov, Reference Orlov1998; Lucifora et al., Reference Lucifora, Valero, Bremec and Lasta2000; Koen Alonso et al., 2001; Brickle et al., Reference Brickle, Laptikhovsky, Pompert and Bishop2003; Treloar et al., Reference Treloar, Laurenson and Stevens2007). Considering the aforementioned and evaluating the diet of skates that inhabit the Argentine Continental Shelf, it is observed that those specimens between 75 and >100 cm maximum total length (Bathyraja griseocauda, B. scaphiops, B. cousseauae, B. brachyurops, and Zearaja chilensis) changed their diet from invertebrates, mainly isopods, amphipods and crabs, to fish (García de la Rosa & Sanchez, 1999; Lucifora et al., Reference Lucifora, Valero, Bremec and Lasta2000; Koen Alonso et al., 2001; Brickle et al., Reference Brickle, Laptikhovsky, Pompert and Bishop2003; Belleggia et al., Reference Belleggia, Mabragaña, Figueroa, Scenna, Barbini and Díaz de Astarloa2008). In contrast, species who reach around 60 cm of total length (B. macloviana, Psammobatis normani and P. rudis) in the same area, fed mainly on polychaetes and small crustaceans (Mabragaña & Giberto, Reference Mabragaña and Giberto2007; Ruocco et al., Reference Ruocco, Lucifora, Díaz de Astarloa and Bremec2009). Amblyraja doellojuradoi is part of this group since the maximum reported size is 60 cm and in the ontogeny it preys on polychaetes and other invertebrates to later feed mainly on crabs. This change is due to the increasing size of the predators, since with a gradual increase in total length, swimming capabilities increase, permitting the capture of bigger and faster prey items, and also to the techniques related to the feeding system, like gape size (Scharf et al., Reference Scharf, Juanes and Rountree2000) and to the strength of biting or sucking (Motta, Reference Motta, Carrier, Musick and Heithaus2004).

Another variable that determines the consumption of polychaetes and other crustaceans is the maturation of the specimens. Immatures of A. doellojuradoi showed an increased consumption of polychaetes and other crustaceans. This is hypothesized to be a result of the higher vulnerability of small prey compared to large prey due to higher encounter rates and the higher probability of capture once detected (Lucifora et al., Reference Lucifora, García, Menni and Escalante2006). Within the species, reduced competition between mature and immature would increase survivorship for the latter during the critical early stages of life. Mature elasmobranchs of many species feed on larger, more active prey items that immatures cannot obtain, thereby reducing intraspecific competition with smaller, younger conspecifics (Olsen, Reference Olsen1954; Springer, Reference Springer1960; Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Wetherbee, Crow and Tester1996; Gray et al., Reference Gray, Mulligan and Hannah1997).

It was also noted that consumption of some prey items varied depending on the regions. Crabs were consumed mostly in the north rather than in the south; fish, isopods and other crustaceans were consumed chiefly in the south rather than in the north. The lack of detailed quantitative information on the distribution and availability of potential benthic prey on the Argentine Continental Shelf prevents an assessment of prey selectivity by A. doellojuradoi. Mabragaña & Giberto (Reference Mabragaña and Giberto2007) found a similar feeding pattern in P. normani and P. rudis, species both inhabiting the same environment as A. doellojuradoi. These authors state that between 35 and 41°S, the most consumed prey were crabs, and between 48 and 55°S were isopods and amphipods. The benthic communities may differ among regions in relation to abundance, dynamics and arrangement. In the north, the inner limit of the Argentine Continental Shelf is forming a highly productive front inhabited by large numbers of benthic prey (Acha et al., Reference Acha, Mianzan, Guerrero, Favero and Bava2004; Mabragaña & Giberto, Reference Mabragaña and Giberto2007).

Another variable that determined the consumption of a prey category was sex. Dietary analysis of A. doellojuradoi showed an increased consumption of fish and isopods in females. It was known that some female sharks grew to bigger sizes than males (Cortés, Reference Cortés2000) and exhibited sexual segregation (Springer, Reference Springer, Gilbert, Mathewson and Rall1967). Hence, it could be presumed that females of shark species with sexual size dimorphism and spatial segregation would have a different dietary composition than males. However, skates inhabiting the same habitat, that reached equal size and possessed similar capture capabilities, are expected to exhibit diets and ecological roles alike in both sexes (San Martín et al., Reference San Martin, Braccini, Tamini, Chiaramonte and Perez2007). Nevertheless, Ezzat et al. (Reference Ezzat, Abd El-Aziz, El-Gharabawy and Hussein1987) reported sexual differences in the diet of R. miraletus in the Egyptian Mediterranean waters. Commonly, these disparities appeared as higher frequencies of occurrence of crustaceans and fish in female stomachs, and worms and molluscs in those of males (Ezzat et al., Reference Ezzat, Abd El-Aziz, El-Gharabawy and Hussein1987). In some species of the genus Bathyraja from the North Pacific, sexual differences in food composition were also found and they have been associated with sexual size dimorphism (Orlov, Reference Orlov1998). Diet of skates might vary between sexes either as a result of sexual dimorphism and differences in the predatory capacity of males and females, and/or because of differences in the spatio-temporal foraging activity (San Martín et al., Reference San Martin, Braccini, Tamini, Chiaramonte and Perez2007). In the case of A. doellojuradoi, differences in the spatio-temporal foraging activity of males and females should be ruled out (Braccini et al., Reference Braccini, Gillanders and Walker2005) because both sexes had the same distribution. Sexual size dimorphism should also be ruled out (Begg et al., Reference Begg, Begg, Du Toit and Mills2003) because, beyond the existence of dimorphism, it is contrary to what had been expected, males being larger than females. Generally, species that consume fish have sharp teeth to capture these prey items more successfully (Feduccia & Slaughter, Reference Feduccia and Slaughter1974). However, teeth of A. doellojuradoi were sharper in males than in females, in opposition to the difference reported in diet (Delpiani et al., Reference Delpiani, Figueroa and Mabragaña2012). Thayer et al. (Reference Thayer, Schaff, Angelovic and LaCroix1973) proposed that prey consumption is determined by the calorific value. In this case, the total caloric content of small crustaceans is lower than that of teleost fish. Therefore, increased consumption of fish by females could be due to an energy demand for the reproductive processes such as gonadal development, egg formation and gestation (King & Murphy, Reference King and Murphy1985). A qualitative or quantitative shift in their diets for meeting these growing requirements could be expected (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Pettorelli and Durant2007).

Finally, several factors might influence the feeding of A. doellojuradoi. This species occurred sympatrically with many similar-sized species and consumed the same prey categories. Hence, few species could be main trophic competitors for the species under study. Another factor that could have modified the diet of A. doellojuradoi was the commercial fishing. From 1992 to 2006, skate fisheries in Argentina became strongly important, and capture rose from 761 t to 23,618 t (Cousseau et al., Reference Cousseau, Figueroa, Díaz de Astarloa, Mabragaña and Lucifora2007). This activity may affect marine populations both directly through removal of individuals and indirectly through loss of habitat and modification of the trophic structure (Cousseau & Perrotta, Reference Cousseau and Perrotta2000). Therefore, due to these factors, the environment can be constantly altered, making it difficult to determine the causes of food preference.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to express our gratitude to Dr M. Scelzo, Dr R. Elías and Dr A. Garese for helping with the identification of crabs, polychaetes and hydrozoans, respectively. Thanks also to Dr S. Barbini for instructing us in the statistical method used for the analysis. Finally we would like to thank the Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo Pesquero (INIDEP, Argentina) and the engineer R. Gonzalez for the specimens collected.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

G. Delpiani and M.C. Spath were supported by CONICET, Argentina.