1. Introduction

Virtual exchange is a term for describing the different approaches to the engagement of learners in sustained online intercultural interaction and collaboration with partners from other cultural contexts as an integrated part of coursework and under the guidance of educators (O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2018). Over the past decade, virtual exchange has experienced exponential growth as a tool for online education, in particular foreign language teaching. From its origins in the 1990s in the forms of eTandem (O’Rourke, Reference O’Rourke and O’Dowd2007) and telecollaborative language learning (Belz, Reference Belz2002), there now exists a wide range of approaches to online intercultural exchange that can be brought together under the umbrella term of “virtual exchange”. This shift in terminology in the field of computer-assisted language learning (CALL) from “telecollaboration” (Belz, Reference Belz2002) or “online intercultural exchange” to “virtual exchange” (VE) can be justified for the sake of promoting cross-curricular understanding, as the latter term is widely used by other disciplines and organisations. It can also facilitate bringing the activity in line with the terminology currently used by funding providers (O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2018).

Organisational and governmental support for VE has grown substantially in recent years. In Europe, the European Commission launched Erasmus+ Virtual Exchange in 2018, a flagship programme that aims to expand the reach and scope of the Erasmus+ programme via VE. In the United States, organisations and networks such as the SUNY Center for Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) and the Stevens Initiative provide training and support for educators and institutions who are interested in integrating VE in their curricula. Various international projects have looked at the application of VE on foreign language education. These include the “Integrating Telecollaborative Networks in Higher Education” (INTENT) project and “Evidence-Validated Online Learning through Virtual Exchange” (EVOLVE).

Although early applications of VE in CALL contexts emphasised the potential the activity offered for enabling students to engage in authentic use of the foreign language outside the classroom (Little & Ushioda, Reference Little and Ushioda1998), more recent approaches have emphasised the need to locate telecollaborative learning within a formal learning context where students’ interactions are guided and supported by the tasks and learning environment provided by their teachers (O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2020). The development of a VE requires considerable collaboration and communication on behalf of the partner teachers as they work together to design tasks and identify opportunities for learning. It is precisely this collaborative work of the teaching partners that differentiates VE from self-directed online learning or single-class distanced teaching. The importance of the collaborative interaction between teachers – and not just the learners – is one of the distinguishable features of VE, and yet the impact of running a VE on the teachers is one of the most underexplored aspects of this learning activity (Kurek & Müller-Hartmann, Reference Kurek and Müller-Hartmann2019; O’Dowd & Dooly, Reference O’Dowd, Dooly and Jackson2020; O’Dowd, Sauro & Spector-Cohen, Reference O’Dowd, Sauro and Spector-Cohen2020).

With this in mind, we set out to examine the impact of VE on educators’ teaching practice and continued development as professionals by examining the impact that setting up and running a VE had on the professional and pedagogical practices of 31 university teacher trainers. In particular, we were interested in teachers’ perspectives regarding the opportunities for innovation and for professional development that emerged from this experience. Our guiding research question was the following: How do in-service teachers perceive their involvement in VE as having an impact on their professional networks, teaching approach, or on other facets of their professional development?

To compile the data, qualitative interviews were carried out in both text-based and videoconferencing formats with the teacher trainers who had run a VE with their students (more details on the process follows). The participants were teacher trainers primarily from European countries (Spain, Portugal, Hungary, and Germany), although some informants were also outside of the EU (United States, Brazil, Israel, Turkey, and Macau). Twenty-nine of the 31 informants were novice telecollaborators, so this was, for most of the interviewees, the first time they had organised a VE with their classes. The data were analysed through a qualitative content lens (Zhang & Wildemuth, Reference Zhang, Wildemuth and Wildemuth2009) to discern the most recurrent categories discussed in the interviews. In this article, we focus on the participants’ perspectives of the VE experiences related to professional and personal development.

The paper is organised in the following way. In the next section we carry out a short review of the learning outcomes of VE in foreign language contexts, paying particular attention to the potential benefits for the teachers who ran these exchanges. We also review the literature on teachers’ professional development through participation in collaborative communities. Following that, we present the context within which this study was located and we outline the research methodology involved. We then present the findings of our study and conclude by considering the implications of our research for the future of VE in foreign language education.

2. Literature review

2.1 The benefits of virtual exchange for students and teachers

There has been over two decades of research on the principally positive learning outcomes of VE in foreign language education in university contexts (Eck, Legenhausen & Wolff, Reference Eck, Legenhausen and Wolff1995; O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2016; Warschauer, Reference Warschauer1995). The benefits of VE in primary and secondary education have also been documented to a lesser degree (Dooly, Reference Dooly, Jenks and Seedhouse2015; Dooly & Masats, Reference Dooly, Masats, Beckett and Slater2020; Grau & Turula, Reference Grau and Turula2019; Ware & Kessler, Reference Ware and Kessler2016). Specifically, there has been considerable research, mostly in higher education, regarding learner gains and outcomes in intercultural and language learning, which are two of the most predominant areas of practice and research in contemporary CALL (Avgousti, Reference Avgousti2018; Çiftçi & Savaş, Reference Çiftçi and Savaş2018; Shadiev & Sintawati, Reference Shadiev and Sintawati2020).

Studies have demonstrated various benefits that VE can offer foreign language education. First, telecollaborative interaction with online peers has been seen to facilitate key language learning processes, such as the negotiation of meaning (Blake & Zyzik, Reference Blake and Zyzik2003) and peer corrective feedback (Díez-Bedmar & Pérez-Paredes, Reference Díez-Bedmar and Pérez-Paredes2012). Second, researchers have highlighted the potential gains in pragmatic competence in foreign language learning (Belz & Kinginger, Reference Belz and Kinginger2003; Cunningham & Vyatkina, Reference Cunningham and Vyatkina2012). Studies imply that the interactional and performative aspects of online exchange, along with a wider exposure of the language learners to a broad range of foreign language discourse options, may be underlying reasons for advances in intercultural pragmatics (Kecskes, Reference Kecskes2014). Third, VE offers learners the opportunity to explore in depth cultural “rich points” and elicit connotations of cultural behaviour from “real” informants from the partner cultures, allowing learning insight into personalised, subjective accounts of their partners’ sociocultural environments and access to more nuanced understandings of how cultural knowledge is inevitably partial and may even encompass conflicting discourses on both individual and collective levels (Dooly, Reference Dooly, Ben Said and Jun Zhang2013, Reference Dooly, O’Dowd and Lewis2016). Finally, learners have the opportunity to more fully grasp cultures as highly complex, dynamic systems, with boundaries that are fluid and mutable, and they can discern first-hand the tendency of globalisation to resignify the local – and vice versa (Androutsopoulos, Reference Androutsopoulos and Coupland2010; O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2016; Sultana, Reference Sultana, Barrett and Dovchin2019).

The beneficial impact of VE on the teachers who run the exchanges and the challenges that they often encounter have evoked far less interest in the CALL literature to date. However, there are some notable exceptions. Caluianu (Reference Caluianu, Turula, Kurek and Lewis2019), for example, discusses the challenges faced by VE instructors that can lead to negative impact on their telecollaborative exchange. In particular, the author notes issues such as the increase in workload, lack of administrative support, and communication issues between the teachers. O’Dowd (Reference O’Dowd2011) reports on a survey of university-level foreign language instructors who had used telecollaborative exchanges in their classes. He found that although teachers reported receiving sufficient technical support, there was very little pedagogical support available for educators who were interested in learning about VE and how the activity could be integrated into their classes. Informants also mentioned other common barriers to take-up, including the heavy workload involved in setting up an exchange, the variability of student learning outcomes, and the lack of reliability of international partners.

As regards the benefits of VE for teachers, a small number of relevant studies can also be identified. For example, in a self-reporting study by a distance education teacher who, with another teacher, integrated VE into her online class programme, Siergiejczyk (Reference Siergiejczyk2020) underscores that despite the challenges of adapting to new pedagogical paradigms, VE offered teachers the opportunity to develop practical skills, such as facilitating student dialogue and developing more culturally contextualised foreign language instruction. Similarly, a baseline study on teachers’ VE awareness relates that teachers who participate in VE overwhelmingly agreed that involvement in these types of exchanges can lead to teaching innovation and can serve as a means of continued professional development, as well as being a key tool for the internationalisation of both students and teachers (Jager, Nissen, Helm, Baroni & Rousset, Reference Jager, Nissen, Helm, Baroni and Rousset2019). Creelman and Löwe (Reference Creelman, Löwe, Turula, Kurek and Lewis2019) found that teachers taking part in VE projects are exposed to more opportunities for professional networking and knowledge sharing, although there is a need for raising teacher and administrative awareness of this potential in order for more mainstream adoption of the activity to occur.

A key challenge that has emerged in the studies is the intense online collaboration that is required between partner teachers during VE; thus, in the following section, we examine what and how teachers can learn from each other in collaborative communities.

2.2 Teachers’ development through participation in collaborative communities

There is ample evidence in the literature that the promotion of successful innovative practice in education depends to a great extent on the opportunities teachers have to participate in collaborative networks and partnerships with experts and peers beyond the more immediate circle of daily contacts (Brown & Campione, Reference Brown, Campione and McGilly1994; Cochran-Smith & Lytle, Reference Cochran-Smith and Lytle2020). These networks may involve collaboration between teachers and “experts” or they may simply involve collaboration between colleagues.

Collaboration for teacher development occurs frequently between academics and teachers (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, Reference Cochran-Smith and Lytle2009; Masats, Dooly, Juanhuix, Moore & Vallejo, in press). Johnson (Reference Johnson2009), for example, reports on “Teacher Study Groups” that involve long-term partnerships between public schools, universities, and professional associations that promote opportunities for university-based and school-based faculty to identify and study problems of practice together. The action research carried out in teacher study groups assumes that teachers work best on problems they have identified in their own contexts and that these problems can most successfully be overcome by working collaboratively with colleagues from different educational contexts (Cochran-Smith & Donnell, Reference Cochran-Smith, Donnell, Green, Camilli, Elmore, Skukauskaiti and Grace2006; Lambirth et al., Reference Lambirth, Cabral, McDonald, Philpott, Brett and Magaji2019).

There are also reports of benefits of teacher-to-teacher collaboration (Keffer, Wood, Carr, Mattison & Lanier, Reference Keffer, Wood, Carr, Mattison, Lanier, Bisplinghoff and Allen1998), often described as “learning communities” (Chan & Pang, Reference Chan and Pang2006). Christianakis (Reference Christianakis2010) argues that collaborative teacher research is key for making connections between theory and practice: “collaboration between different practitioners can offer opportunities for interdependence, diverse thought and blurred boundaries” (p. 113). Following a review of different studies in this area, Johnson (Reference Johnson2009) concludes that teachers who participate in such collaborative communities of practice are able to develop new understandings of themselves as teachers, of the curriculum they teach, and of their own teaching practices. Teachers also reported emerging from the groups with an increased sense of efficacy and empowerment. In a large-scale study of 53 schools (Moolenaar, Sleegers & Daly, Reference Moolenaar, Sleegers and Daly2012), it was found that teacher networks ultimately benefit student achievement, although there was no evidence of direct causality. The authors of the study conclude that strong teacher networks have an indirectly beneficial effect through the creation of supportive environments that foment creative instructional strategies while boosting teachers’ personal sense of efficacy.

The literature also indicates that collaboration between teachers is particularly important when dealing with innovative activity such as the introduction of technology into teaching. For example, in their study of the factors that influenced the innovative use of technologies by teacher educators in the Netherlands, Drent and Meelissen (Reference Drent and Meelissen2008) found that teacher educators who demonstrate a willingness to develop contacts with fellow teachers and with experts working in the area of information and communication technology are more likely to use technology creatively. The study suggests that in order to stimulate innovative use of technologies in education, it was necessary to provide “supportive conditions” such as the development of cooperative communities between teachers. The OECD (2015) study on teachers’ use of technology also found that participation in professional development activities that involve collaborative research or working within a network of teachers makes it more likely that teachers will increase their use of student-centred technology practices.

It has been argued that teachers’ virtual learning communities can play a key role in teacher development (Cachia & Punie, Reference Cachia, Punie, Hodgson, Jones, de Laat, McConnell, Ryberg and Sloep2012; Macià & García, Reference Macià and García2016). However, online approaches to educational communities of practice have not been widely implemented to date and there are even fewer examples of collaborative research stemming from collaborative online teaching. Knight (Reference Knight2020) looked at the potential of online collaborative networks for teachers in the context of COVID-19. She argues that the onset of the pandemic means that all practitioners, even those who have enjoyed previously robust professional networks, are likely to endure some level of isolation and that online collaboration will be key to overcoming this isolation. The author proposes four central principles for effective online collaborations: “(a) practitioners must participate in professional communities; (b) practitioners need to be granted enough time for development to occur; (c) mediators (both technical platforms and community leaders) have to provide ongoing support to practitioners; and (d) relationships among practitioners, regardless of their relative experience, are both collaborative and mutually beneficial” (p. 301).

In summary, a review of the literature confirms VE as an educational activity that holds great learning potential for both students and teachers and also highlights the importance of teachers’ engagement in collaborative communities for their professional support and development. The study reported here explores the personal and professional benefits for teachers that can emerge from the collaborative relationships developed by teachers working together in VE.

3. Context of the study

This study stems from a European policy experiment within the Erasmus+ Key Action 3 programme (The EVALUATE project: EVALUATING AND UPSCALING TELECOLLABORATIVE TEACHER EDUCATION) with the aim of upscaling current policies and practices of VE in European higher education (Baroni et al., Reference Baroni, Dooly, Garcés García, Guth, Hauck, Helm, Lewis, Mueller-Hartmann, O’Dowd, Rienties and Rogaten2019). Under the auspices of the project, multiple VE partnerships were set up and run as part of the data collection for the study. Teacher trainers were recruited through a call for participants, which was sent out in various online mailing lists (including that of EUROCALL) and on various social networks.

Each of the teaching partnerships elaborated their own joint exchange curriculum according to various factors, including curriculum requirements they had in common, overlap in timetable regarding number of lessons, the focus of the subjects, and other factors that might influence the exchange. The partners were guided through the design of their exchange by VE experts, who helped them establish initial contact, discuss similarities and differences in their core areas of study, and then design a VE.

The participants were provided with tasks based on a widely used model of task sequences (O’Dowd & Waire, Reference O’Dowd and Waire2009) that is common in foreign language approaches to VE. The model includes three interrelated tasks that run along a spectrum, from information exchange to comparing and analysing cultural practices, to eventually working on a collaborative product or output. The teacher trainers, once partnered, had the opportunity to adapt the task sequences to their own particular joint curriculum for their exchange.

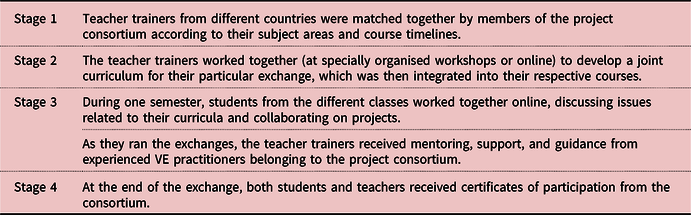

In total, 34 institutions of initial teacher education from 16 countries were involved in the exchanges, which ran over two semesters (some institutions participated in various exchanges). From the 34 institutions, 31 teachers agreed to be interviewed. Most institutions were from European countries, but teacher educators from the United States, Brazil, Israel, Turkey, and Macau also took part in the project and their institutions were included in the study. Some of the teacher educators taught subjects related to primary school education in general, whereas the large majority were responsible for subjects related to foreign language education and bilingual education. The class-to-class VEs were organised in the manner outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Stages of the virtual exchange programme

4. Research framework

4.1 Approach

In order to explore the perceived impact of their involvement in the above described programme on their professional networks, teaching approach, or on other facets of their professional development, the teacher trainers involved in the exchanges were invited to take part in individual interviews. These were carried out as either written (interview questions answered through email) or online and/or face-to-face interviews. Thirty-one teachers accepted. Because the interviews were carried out by more than one researcher, a simple interview outline, consisting of eight core questions, was used to ensure “consistency of treatment across a set of interviews” (Drever, Reference Drever2003: 18) and to allow for comparability of answers. Of course, the responses to these initial guiding questions often led to follow-up questions and requests for clarification. The core questions used by the researchers were as follows:

-

1. What do you think you learned as a teacher from the experience? Was it worth the trouble?

-

2. Did you integrate the exchange into your classes? If so, in what ways did you do that? Did you discuss the tasks and the interactions with your students? Did they work on their interactions during class time?

-

3. How would you describe your relationship with your partner teacher? How often did you communicate together?

-

4. Did you encounter any challenges in your university as you carried out the exchange in your university?

-

5. Did the project have any supplementary outcomes or impact on you or your students?

-

6. Would you like to do more virtual exchanges in the future? If so, would you follow the same format as this one? Or would you do it in a different way? Explain.

-

7. What advice would you give other teacher trainers in your country considering using virtual exchange projects in their classes?

-

8. What recommendations/requests would you make to policymakers in your country about virtual exchange? What could they do to make it easier for teachers like you to use virtual exchange in your classes?

To analyse the data and help answer our research questions, qualitative content analysis was used (Zhang & Wildemuth, Reference Zhang, Wildemuth and Wildemuth2009). This is a widely used qualitative research technique that goes beyond merely counting words and instead carries out the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the process of identifying themes or patterns and systematically classifying them through the use of codes.

4.2 Respondents

A total of 31 interviews were carried out, which, according to Hagaman and Wutich (Reference Hagaman and Wutich2017), falls within the spectrum for sufficient data saturation to identify meta-themes (20 to 40 interviews). The informants were all experienced teachers; however, 29 out of the 31 were novices to VE. The majority (24) were teacher trainers at faculties of education who came from the project’s “partner” regions and countries – Spain, Portugal, Hungary, and Baden Württemberg, Germany – and were teaching courses related to applied linguistics or foreign language teaching methodology.

4.3 Data management and analysis

Once all the interviews had been completed, the data were transcribed (in the case of interviews, carried out via videoconference) and the transcriptions, along with the written interview responses, were transferred into a shared NVivo data analysis platform. Next, the transcripts were read repeatedly by the two researchers in order to select relevant text fragments and assign preliminary codes (words or phrases). The codes were exemplified with key text fragments (Hsieh & Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005).

To ensure coder reliability, the two researchers first individually coded and recoded the data before exchanging their thematic codes for corroboration. After exchanging their initial thematic codes, categories were either subsumed or new categories created through grouping of text fragments with similar codes related to the initial driving question: How do these in-service teachers perceive their involvement in VE as having an impact on their professional networks, teaching approach, or on other facets of their professional development? During this step of the analytical process, the two researchers worked together to reorganise and refine the categories (Cho & Lee, Reference Cho and Lee2014). These new codes were then revised once more to make sure they adequately corresponded with the key text fragments in order to consolidate the major emergent themes stemming from the data (Hsieh & Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005).

The ethics protocol applied to the data included obtaining informed consent before the interviews. Interview candidates were prompted to voice any concerns or questions about confidentiality before beginning the interview. Personal names mentioned in the interviews were converted to pseudonyms in the final transcriptions. The fragments chosen for analysis were scrutinised for potential indicators of identity of persons or institutions involved before being included in reports or texts.

5. Findings

An analysis of the interview data reveals various trends related to how teachers perceived the impact of the VE programme on their students and on themselves. Despite the fact that the questions were principally on the teachers’ personal experiences, the interviewees’ responses often focused on how they viewed the impact of VE on their students who had been involved in the exchange. As can be seen in Table 2, two meta-themes in relation to student learning, which the teachers mentioned in the interviews, were the expansion of learning opportunities (predominantly related to language, intercultural, and subject areas) and the increase in collaborative learning and learner autonomy.

Table 2. Key themes regarding impact on their students (teachers in training)

These answers were not very different from findings from other research regarding the impact of VE on student learning (see reviews by Akiyama & Cunningham, Reference Akiyama and Cunningham2018; Çiftçi & Savaş, Reference Çiftçi and Savaş2018). Teachers saw their telecollaborative projects as opportunities for their students to use their foreign languages in real-world communicative practice and to develop intercultural competence through their online interactions. However, it is significant the importance the informants attributed to various transversal skills and attitudes that are not regularly mentioned in the research on student outcomes in VE. These included collaboration skills, flexibility, teamwork, and creative thinking. One teacher trainer concluded:

I realised that the students had understood the essence of what we wanted to develop in this project – which is put yourself in the position of the other, understand them and, many times, give way. They told me that they had learn the contents of the course better because their international partners had helped them see the contents from another point of view. And they learned how other people work.

Apart from their students’ learning outcomes, the data revealed that the teachers involved in the exchanges felt that the experience had had an important impact on their own personal opportunities, practices, and perspectives regarding teaching and learning. In particular, a number of themes regarding modifications in their teaching practices and enhanced opportunities for innovation in aspects of their professional lives emerged. These are outlined in Table 3 and will be looked at in more detail in the following sections.

Table 3. Main themes and subthemes regarding impact on themselves (teacher interviewees)

5.1 New partnerships and forms of collaboration

A key theme that emerged from the data was the affordance that VE offered the teachers of new prospects for increased collaboration with their partners and the partner institutions. These opportunities ranged from individual partnerships for both teaching and research to new physical (in addition to the virtual) mobility for both the teachers and the students. The amount of protraction and augmentation stemming from the initial exchanges is noteworthy, particularly in this case of a German teacher trainer reporting on the outcomes of his VE with an Israeli partner:

We’ve set up an official cooperation agreement between our two institutions. And I’m taking my class to Israel [the country of the VE partner] in May so they will meet each other face to face. And third, there will be a joint conference between our two institutions. I disseminated this project in our institution and now there are other colleagues who are interested in collaborating with the Israelis. So we are going to have a joint conference in October in Tel Aviv. I couldn’t have imagined this three years ago.

This is not the only interview data that mention the development of greater institutional cooperation and formalised agreements as an outcome of the semester-long experimental telecollaborative exchange. The following example comes from a Spanish teacher trainer who took part in a Spanish–Polish partnership:

We discussed the possibility of repeating the experience next academic year. We have actually now made an Erasmus agreement between their two faculties, and 4 students from [Spanish university] will be going to [Polish university] next.

Extended collaboration also came in the form of the VEs leading to short-term physical mobility and study visits between the institutions, as the following example illustrates:

The Brazilian group is now with intention to try to carry out a “study visit” to [their institution] in Portugal next year. Teachers are also considering joint projects around this theme.

The following responses show that teachers were also interested in extending invitations to their partners in ways that could potentially engage colleagues outside their own disciplines:

I would like to invite the two teachers from Holland to come and teach here in my faculty and organise a workshop for the other teachers in the faculties and invite students to come and talk about their experiences. Because I think this would be suitable not only for students of languages but also for students of other faculties.

The learning opportunities offered by such combinations of VE and short-term physical mobility have been unexplored to date, and this is an area that is undoubtedly worthy of further exploration.

5.2 Collaboration for research, reflection, and professional growth

Another meta-theme uncovered in the results from the teachers’ VE experiences was the way in which the collaboration between the teachers grew to include research partnerships. This is exemplified by one teacher who described how the telecollaborative work had led to her investigating and publishing together with her partner:

[My partner] is interested in doing research on the project – in fact what drew her to [project name] rather than eTwinning was the research side. She needs publications in journals (not book chapters) and is gathering data of her own with more specific info on the local context.

The interviews revealed that more than one partnership was planning on writing and submitting proposals for conference presentations together: “We are going to … at least we sent an abstract to present a little bit of this project.” Another interviewee mentioned mutual interest in working together to write an article or chapter about their experience: “[My partner] is wonderful – we still communicate and hope to publish something together in the future.”

Validating the findings from Brody and Hadar (Reference Brody and Hadar2018), the respondents in this study also highlighted their own professional growth, which they felt derived from their interactions with their colleagues (in this case, their distanced partners). As the teachers strove to collaborate and work together, they felt they had developed their ability to adapt, make positive changes, and learn from the other. This can be seen in the following extract:

We were able to adapt to each other plans and to appreciate each other’s visions and suggestions and we tried to really coordinate our syllabus. I think that we made a very positive work in adapting to each other syllabus and to create a new one where we could accommodate each other’s perspectives and fit EVALUATE experts’ suggestions.

5.3 Enhanced teaching competences

A third significant theme was related to how the participation in the VEs enabled teacher trainers to develop certain professional skills, such as their ability to collaborate online and to develop innovative teaching practices.

One respondent highlighted that VE can be an intercultural learning experience for teachers as well as for students:

First of all, it was for me a challenge to approach this subject from a different perspective. This was enriching for the subject and enriching for me because I found new dimensions in the subject. It was also enriching for me because I had a chance to work with teachers who had a different academic culture to my own. And having to look for a common position together is enriching because you see that you can achieve that, you can achieve a meeting point and work together with people from another academic culture.

This corroborates other studies that advocate “inquiry as stance” and “inquiry communities” in teacher education, which will enable educators to work together to gain (professional) knowledge by linking their knowledge to practice (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, Reference Cochran-Smith and Lytle1999; Creelman & Löwe, Reference Creelman, Löwe, Turula, Kurek and Lewis2019). From this respondent’s perspective, the VE experience appears to have brought about this effect of shared inquiry:

Of course, that means putting yourself in the position of the other, giving in at times, being more open and more aware of how other institutions work. So this collaborative work has been very enriching for me because it helped me to see other points of view and other ways of working. And it also enriched the subject, adding dimensions that weren’t there before.

The respondents also reported that by engaging their classes in a VE they had come to the conclusion that they needed to be more innovative in general, in both the course where the exchange took place as well as in other courses. The following example exemplifies how VE had encouraged the teacher to take a more critical stance to her own teaching and to develop more interactive activities for her classes:

You realise what is interesting and motivating for your students. It gets you closer … It motivated me to personalise my courses more. As I saw that they responded and participated so much with their partners, this pushed me to create more interactive activities for the rest of my courses and teaching as well. Until now I had done more traditional methods – I would create a video lecture and send it to them. But now I insist on them doing group work and participating more. I had never thought of that before. I now take a much more interactive approach to their learning.

However, it is important to acknowledge that these opportunities for innovation and professional development are not an automatic outcome of participation in VE. It was clearly not the case that VE led to other forms of innovation when teachers were not open to these opportunities. Our data contain evidence of teacher trainers who failed to engage in regular contact with their partner teachers or who were clearly averse to adapting to partner teachers who were operating in different socio-institutional contexts to themselves. The following comment illustrates how easily the collaborative partnership between teachers involved in a VE can break down:

After a few weeks [my partner] wrote to me because there had been students from [my university] who hadn’t done anything. My students said they had been working … Some students from her class and from my class left the project and after that the communication between the two teachers was less fluid. She said in an email “talk to your students, find out why they are not working”. I replied that it was the problem of the two groups. After that the project went better but we never exchanged any more emails.

Teachers can often become frustrated by the different working conditions or constraints of their partner teachers. The following extract exemplifies this clearly:

Well because it took a lot of time. Sometimes you have to wait for answers from the other group. So my students said “can’t we just skype?” and the other group said “we are not allowed to use skype on the computers or something”. So there were two or three groups that worked really really well and there was one group that was just sitting there and didn’t get any replies from their partner group which was also sitting in class. And then I couldn’t communicate with [my partner teacher] because she didn’t reply to her emails and she didn’t have any other social media … So that made it very complicated.

Such setbacks may easily result in the dropping of the partnership once the exchange ends – as opposed to the enthusiastic morphing of the VE into other types of exchanges and partnerships, as described above, or the transferral of these teaching competences to situations such as the current crisis. And the reaction to the constraints described in this last extract may not lead to the reflective practice of how to improve in subsequent iterations of VE.

6. Discussion

Emergent thematic patterns from the interviews of these teacher trainers involved in VE indicate the participants found that the experience not only was generally positive for their learners but also had a significant impact on their own professional behaviour and development as teachers. We identified in the data key themes such as extended opportunities for teacher collaboration, new and unexpected opportunities to expand into research, and professional growth, often involving the development of the teachers’ collaborative skills and intercultural awareness.

While the role of collaboration in VE is often understood as an inherent benefit for learners, such as the enhancement of collaborative learning, the importance of collaboration for the partner-teacher development has received less notice. This is significant given the role of networks and partnerships for teacher professionalisation (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, Reference Cochran-Smith and Lytle1999, Reference Cochran-Smith and Lytle2009; Moolenaar et al., Reference Moolenaar, Sleegers and Daly2012). Moreover, it was seen in the literature review that one of the factors that may influence the innovative use of technologies, including collaborative teaching, is teachers’ willingness to develop contacts with other colleagues who are also working with technology (Creelman & Löwe, Reference Creelman, Löwe, Turula, Kurek and Lewis2019; Drent & Meelissen, Reference Drent and Meelissen2008; Jager et al., Reference Jager, Nissen, Helm, Baroni and Rousset2019).

The attributes highlighted by the interviewees (opportunity and capacity to collaborate with colleagues, adeptness at engaging other colleagues in innovative practices, motivation and creativity to initiate bottom-up actions, etc.) are essential not only for more professional teaching practices but also for teacher reflection and subsequent innovation. The interviewees provided detailed explanations about how the experience had led them to reflect on their previous teaching practices and the need to be more flexible when opening up their classroom practices to others. This corroborates Brody and Hadar’s (Reference Brody and Hadar2018) study on factors that lead to teacher change, in which they found that “collegial” interaction is a major determinant for teachers to research and then implement change in their teaching. Our findings are also in line with results from Tanghe and Park’s (Reference Tanghe and Park2016) study on the impact on teachers’ critical awareness following a VE experience. The VE helped reshape their “positioning vis-à-vis one another”, “vis-à-vis the contexts”, and “vis-à-vis course materials” towards “broadened intercultural and international perspectives” (p. 9) among the teachers in their study.

The mutually supportive VE partnership was an important theme for the subsequent opportunities for research and innovation mentioned by the interviewees. As Murray (Reference Murray2015) explains, “it is a generally accepted idea that reflective practitioners are better able to handle the challenges of teaching” (p. 23) but a process of reflection does not always occur given a teacher’s already busy schedule and other personal and professional pressures. However, our data uphold the suggestion that becoming engaged in collaborative teaching can also lead to a “peer-supported collaborative reflective teaching cycle” (Murray, Reference Murray2015, p. 24). The necessity of discussing, negotiating, and mutually planning a course can lead to inquiring into ways of teaching and to critically questioning whether prior methods have helped or hindered the learning process of the students. Moreover, it almost inevitably facilitates ideas on new pedagogical practice as the deliberations on the best single approach between two classes are being held. In short, the data support the notion that teachers engaged in collaboration can have a positive influence on each other – and others in their context – and this may eventually lead to innovation in ever-expanding circles of impact.

7. Conclusion

This study examined the impact that setting up and running a VE had on the professional and pedagogical practices of university teacher trainers. In particular, we were interested in teachers’ perspectives regarding the opportunities for innovation and for professional development that emerged from this experience. The data that were analysed in this study would suggest that participation in VE projects can provide teachers with valuable opportunities for professional development and methodological innovation. The teachers interviewed in the study reported that their VE projects had opened up opportunities for new professional partnerships, collaborative academic initiatives, and had led them to introduce more innovative approaches in their teaching. In short, virtual collaboration had led to professional and academic development. In this sense, the findings reflect Darling-Hammond’s (Reference Darling-Hammond2006) argument that learning from each other is essential for teachers, especially as “the range of knowledge for teaching has grown so expansive that it cannot be mastered by any individual” (p. 305).

The findings of this study may be of interest to the management of foreign language departments in university education as it demonstrates how participation in VE can lead teachers to other forms of internationalisation such as short-term student mobility and participation in international research and publishing initiatives.

However, while it is important to highlight the potential that VE offers to teachers for professional development and methodological innovation, it is also clear that many of these outcomes will only come about from teachers who are open to developing in these ways. With this in mind, it is important to recognise here the danger of “self-selection” in the informants of our study. Simply put, it is likely that teachers who signed up to take part in a VE programme were already likely to be open to innovating their teaching, engaging in international networks, and developing their own intercultural competence. We believe that it is fair to posit that teachers who have little interest in these areas are unlikely to be drawn to VE in the first place. However, the argument can be advanced that reading about results such as those found in this study may encourage other teachers who had not considered implementing VE to do so.

The findings reported here regarding professional development through VE collaboration are similar to those found in literature focused on online teacher networks: the process provides more opportunities to share knowledge, insights, and resources (van Amersfoort, Korenhof, Moolenaar & de Laat, Reference van Amersfoort, Korenhof, Moolenaar and de Laat2011); helps teachers improve their own interpersonal skills (Cachia & Punie, Reference Cachia, Punie, Hodgson, Jones, de Laat, McConnell, Ryberg and Sloep2012); and gain access to new ideas, particularly research-based teaching practices and resources (Caroll & Resta, Reference Caroll and Resta2010). However, the meta-theme of increased possibilities for collaborative research and expanded professional collaboration, including physical mobility (often for research purposes), has been overlooked in other literature and deserves further attention.

It is evident that VE is not a panacea for all the shortcomings in online foreign language education. However, in light of the study results discussed, we argue that VE not only offers rich learning opportunities for students but also offers teachers access to collaborative networks and international partnerships and that VE should be considered as an opportunity for teachers to engage both themselves and their students in international learning experiences.

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this paper was supported by the project Evaluating and Upscaling Telecollaborative Teacher Education (EVALUATE) (582934-EPP-1-2016-2-ES-EPPKA3-PI-POLICY). This project is funded by Erasmus+ Key Action 3 (EACEA No 34/2015): European policy experimentations in the fields of education, training and youth led by high-level public authorities. The views reflected in this presentation are the authors’ alone and the commission cannot be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Ethical statement

The authors confirm that all aspects of the study that are included in this manuscript and that have involved human subjects (interviewees) has been conducted with the ethical approval of the relevant bodies of both of our universities and the European agency that funded the study. We confirm that we received consent from all interview respondents to use their data for analysis and publications. The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest in the publication of the text.

About the authors

Robert O’Dowd is an associate professor at the University of León, Spain. He coordinated the Erasmus+ European Policy Experiment Evaluating and Upscaling Telecollaborative Teacher Education (EVALUATE) (2017–2019). He has published widely on virtual exchange and telecollaborative learning in foreign language education.

Melinda Dooly is full professor at the Department of Language, Literature and Social Sciences Education, Faculty of Education, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain. She is the lead researcher of the publicly funded Research Centre for Teaching & Plurilingual Interaction (http://grupsderecerca.uab.cat/greip/en).

Author ORCIDs

Robert O’Dowd, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7348-135X

Melinda Dooly, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1478-4892