Red Canyon as place

Red Canyon is located in the foothills of the Owl Creek Mountains, a sub-range of the Rocky Mountains that form the southern part of north-western Wyoming's Bighorn Basin (Figure 1). The English name derives from the colour of the iron-rich cliffs found there. In the 1930s, Shoshone Indians identified the canyon as Êngkahonovita Ogwêvi, or ‘Red-gulch's river course’ (Shimkin Reference Shimkin1947: 252). Ancestral landscapes remain important components of Shoshone identity today (Johnson & Johnson Reference Johnson and Johnson2011).

Figure 1. Regional maps (illustration by L. Scheiber; base maps from Google Earth Pro V 7.3.3.7786; http://www.earth.google.com).

A break in the rugged topography, abundant resources and year-round fresh spring water combine to make the canyon an attractive and memorable location. People have been drawn here for thousands of years, as it is a defendable, protected and productive landscape. Artefacts ranging from hundreds to thousands of years old are abundant, with surface and deeply buried archaeological deposits indicating long-term occupations. Indigenous groups who resided in the area include ancestors of the Shoshone, Crow, Comanche, Ute, Bannock, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Blackfeet, Salish and Lakota. The canyon is currently privately owned and is surrounded on three sides by the Wind River Indian Reservation.

Focusing on a brief time period between c. AD 1850 and 1930, this article addresses a significant gap in the archaeology of western North America (Lightfoot & Gonzalez Reference Lightfoot and Gonzalez2018) by emphasising the entanglement of Indigenous residents and settler colonialists. Increasing disciplinary specialisation means that a farmstead, Indian campsite and rock art panel would typically be investigated by different researchers with different research questions. Such separation, however, reduces the opportunity to explore complex responses to colonialism, territorial expansion and assimilation policies. Here, therefore, we seek to bridge divides between prehistoric and historical archaeologies, and to dismantle false dichotomies between Indigenous and Euro-American histories (Funari et al. Reference Funari, Hall and Jones1999; Mitchell & Scheiber Reference Mitchell, Scheiber, Scheiber and Mitchell2010; Schneider et al. Reference Schneider, Gonzalez, Lightfoot, Panich, Russell, Jones and Perry2012).

Red Canyon social geography

In the seventeenth century, Shoshone groups occupied much of the Great Basin, Plateau and Plains, including western Wyoming. Their territory increased after they acquired horses from Comanche relatives in the early 1700s. Shoshone band membership across the region was fluid and loosely organised (Hultkrantz Reference Hultkrantz1961). During the early to mid 1800s, highly mobile equestrian bands of Plains Shoshone actively engaged in trade with American trappers, traders, miners and, eventually, settlers (Shimkin Reference Shimkin, Sturtevant and D'azevedo1986). During this time, Native people of the Plains and Rocky Mountains made strategic decisions to introduce Euro-American-manufactured items into their material repertoire, as witnessed by the diversity of objects at residential campsites and hunting camps (Scheiber & Finley Reference Scheiber, Finley, Scheiber and Mitchell2010a; Scheiber Reference Scheiber, Scheiber and Zedeño2015; Martin Reference Martin2016; Newton Reference Newton2018).

Numerous heterogeneous Shoshone bands settled in the Wind River Basin following the signing of the Fort Bridger Treaty in 1868, which established the 45 million-acre Shoshone Indian Reservation (renamed Wind River in 1937) (Stamm Reference Stamm1999a). Governmental demands, starting with the surrender of the southern third of the reservation in 1872, reduced Shoshone landholdings to only 2.8 million acres. Six years later, the government allowed the Northern Arapaho to relocate to the Shoshone Reservation, thereby increasing competition for land and resources. In 1897, the Shoshone and Arapaho ceded 26km2 of the reservation, which included numerous mineral hot springs on the Bighorn River (Stamm Reference Stamm1999a). Our case study concentrates on the corner of this ceded land, approximately 13km south-west of Thermopolis (‘Hot City’), Wyoming. A final negotiation in 1905 annexed the northern two-thirds of the reservation to American homesteaders, resulting in a patchwork of private and tribal lands to the north of the Wind River.

The U.S. federal government transferred 2.6km2 of land around the mineral springs in 1897 to the state of Wyoming and opened the rest of the land to homesteaders. Swedish-American settlers Jacob and Amanda Nostrum soon staked their claim. In 1898, German immigrant John Voss launched a stage line for mail and passengers between Thermopolis and the Indian agency/military outpost of Fort Washakie. The 112km journey crossed through Red Canyon (Big Horn River Pilot 1898a). The Nostrums decided to open a stage station, which operated until the discontinuation of the mail route in 1905. The rise of the railroad and automobile industries ended stagecoach travel in the early twentieth century (Milek Reference Milek1986).

Prior to the influx of Old World livestock into north-western Wyoming in the 1880s, the Shoshone regularly hunted in the Bighorn Basin and camped at the hot springs (Milek Reference Milek1975; Stamm Reference Stamm1999b). Red Canyon was situated along a well-defined route, and it is where 1800 Shoshones found refuge from a snowstorm while hunting buffalo in 1874 (Patten Reference Patten1926: 297). It was through the canyon that Shoshones and Arapahos insisted on travelling when accompanying Indian agent John McLaughlin to the hot springs in 1896, and it was also where McLaughlin promised them perpetual access to the springs (McLaughlin Reference McLaughlin1910: 299).

The thermal springs (Baa Gwiwene or ‘smoky water’ in Shoshone) in Thermopolis are well known for their medicinal and healing properties. Shoshone individuals sought visions from the resident water spirits, and soaked in the water to increase longevity and battle endurance (Nabokov & Loendorf Reference Nabokov and Loendorf2004: 138). Local settler histories are generally silent about the number and length of Native visits to the springs after the 1897 land transfer, although newspaper accounts suggest that Shoshone families regularly camped there (Big Horn River Pilot 1897; Bangert Reference Bangert1922; Hot Springs County News 1944). Decades later, the Douglas Budget (1950: 4) reported that “Indians come in motor cars and light wagons drawn by ponies and camp for days near the springs”.

The ‘Gift of the Waters’ pageant, written by Thermopolis resident Maria Montabe in 1925 and performed at the Big Spring annually since 1950, presents a fictionalised re-enactment of Shoshone Chief Washakie relinquishing the springs to the American people (Milek Reference Milek1975). Members of the Eastern Shoshone tribe, and Washakie's descendants in particular, have travelled to Thermopolis to participate in this event for nearly 70 years (Thermopolis Independent Record 2019), receiving financial compensation and buffalo meat in return. Shalinsky (Reference Shalinsky1986) argues that the pageant's performance reworks the past to justify the present, casting Indians as past relics while offering little to counter contemporary negative stereotypes. While we agree with her conclusions, we also suggest that some Indigenous investment in the historical narrative occurred in 1950, when Washakie's son, Charlie (an important Peyote church leader), added his dream-inspired ‘Song to Smoking Water’ to the programme (Duhig Reference Duhig1952). As Shoshone people receive power in dreams, song dreamers are considered to be influential healers and singers (Hultkrantz Reference Hultkrantz1997). When Charlie chose to sing his dream song dressed as his father, he added a uniquely Shoshone feature to the pageant that continues today.

Native people leaving the reservation at the turn of the twentieth century followed the familiar path through Êngkahonovita Ogwêvi. Ruts and grooves adjacent to the gravel road leading into the canyon represent visible remnants of the old stage trail. Although the road ends at the ranch at the bottom of the canyon, the faint trace of the old trail continues, crossing into the reservation and heading south through the mountain pass that opens onto the Wind River Basin. Red Canyon therefore represents a border between several entities, notably plains and mountains, Indigenous and settler communities, and the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This interconnectedness is literally and symbolically represented by the road that winds through the canyon (Figure 2). We conducted our field research at Red Canyon between 2010 and 2013. From the beginning, we were intrigued by the juxtaposition of overlapping historical narratives. Although we originally structured our research around borderland issues, it became clear that a framework that permitted investigation of cultural entanglement and sustained colonialism was also necessary (Lightfoot & Gonzalez Reference Lightfoot and Gonzalez2018; Äikäs & Salmi Reference Äikäs and Salmi2019). The integrated analysis of different site types and artefact assemblages has allowed us to recognise the active role that people played in the shaping of temporal and spatial boundaries in Red Canyon (Lightfoot & Martinez Reference Lightfoot and Martinez1995; Hämäläinen & Truett Reference Hämäläinen and Truett2011).

Figure 2. Red Canyon localities mentioned in the text (illustration and graphics by L. Scheiber; base map from Google Earth Pro V 7.3.3.7786; http://www.earth.google.com).

Nostrum Springs stage station

Situated on the border of the Indian reservation on a road connecting two worlds, the stage station was a locus for a range of interactions, communications and negotiations among people from multiple backgrounds—what Hardesty (Reference Hardesty1999: 54) calls “others knowing others”. Several farmstead buildings remain standing in Red Canyon, including the 1915 two-storey Nostrum family home (now a guesthouse), a barn and an outhouse. Among these structures is the collapsed Nostrum Springs stage station. Between 1898 and 1905, a six-horse stagecoach travelled back and forth between Thermopolis and Fort Washakie on alternating days, six days a week (Big Horn River Pilot 1898b; Wind River Mountaineer 1905) (Figure 3). Travellers arrived at Red Canyon at either breakfast or dinnertime. While passengers ate a meal, drivers replaced the horses and inspected the equipment. Amanda Nostrum was well known for her hospitality and fruit pies (Milek Reference Milek1986: 92; Burnett Reference Burnett2013: 75). In addition to feeding weary travellers and accommodating horses, the Nostrums also harvested timber, grew crops, tended orchards and raised livestock. While they remained successful after the 1905 closure of the stage line, Jacob died unexpectedly of pneumonia in 1907. Until 1919, Thermopolis residents lobbied to allocate funds to transform the unpredictable and steep Red Canyon route into a ‘good road’ (i.e. graded, paved and safe), but growing automobile usage led to the improvement of other routes (McCalman Reference McCalman1919).

Figure 3. Stage crossing on the Big Horn River near Thermopolis, Wyoming, on a ferry boat, 1911 (WBD & Annette B Gray Papers, University of Wyoming, American Heritage Center, ah01053_0360).

Nearly a century later, the stage station was a vegetation-covered mound on a dead-end road (Figure 4). Our excavations and metal-detector surveys have collected thousands of artefacts consistent with stage stations and farmsteads throughout the West, including wagon parts, farm equipment, horse tack, ceramic dishes, cartridges, sewing supplies, personal items, mason jars, leather shoes, a toy gun, animal bone, glass, metal, building materials and nearly 100 horseshoes (Burnett Reference Burnett2013) (Figure 5). Dating to between 1897 and 1935, these objects attest to multiple activities around the turn of the century, including equipment repair, horse and wagon maintenance, farming, ranching, food preparation, children's play and domestic activities.

Figure 4. Nostrum Springs stage station, 2007 (photograph by L. Scheiber).

Figure 5. Horseshoes revealed by the stage station excavations, 2011 (photograph by L. Scheiber).

During the early twentieth century, Wyoming attracted a number of first- and second-generation Swedish immigrants (Attebery Reference Attebery2007). Did the Nostrums choose to maintain Swedish traditions and, if so, might these traditions be visible in the materials left behind? Prior to our investigations, we knew only that Jacob and Amanda Nostrum were of Swedish heritage. During archival research, however, we discovered that Jacob was born at Bishop Hill in Illinois—a utopian community of Swedish religious dissenters founded by his parents and grandparents in 1846 (U.S. Census Bureau 1870; Anderson Reference Anderson1947). Bishop Hill was a designated stop for stagecoach passengers travelling west on their way from Chicago to St Louis (White Reference White2012). As a young adult, Jacob left that community before spending time in Kansas, Montana, western Nebraska and, finally, Wyoming (Kansas State Board of Agriculture 1875; U.S. Census Bureau 1880, 1900). Amanda Nilsson, his second wife, emigrated from Stockholm during a mass exodus in her early 20s. She married Jacob in Nebraska and gave birth to four of their eight children at their Red Canyon ranch (U.S. Census Bureau 1900; The Billings Gazette 1955).

Previous investigations of Swedish-American farmsteads in the western USA have found limited evidence for continued Swedish cultural practices (Haught Reference Haught2010). Although Swedish-American immigrant experiences in the American Midwest, Plains and Rocky Mountains are often characterised as primarily assimilationist in character, a nuanced examination of historic and material records reveals a more complex scenario (Palmqvist Reference Palmqvist1987; Attebery Reference Attebery2007). One of the more unusual items that we recovered when we first visited the Nostrum Springs stage station was a small brass box—containing a porcelain button—that had been previously sealed and mortared into the wall. Inspired by Andersson et al.'s (Reference Andersson, Elfwendahl, Gustafson, Hägerman, Lundqvist, Lönnquist, Ulfsdotter and Welinder2011) analysis of materials found at Swedish summer farms, Burnett (Reference Burnett2013) argues that the box was placed in the wall to protect the occupants of the house. Similarly, wire nails and a harness buckle clustered around a chimney indicate the purposeful placement of objects used in everyday rituals.

The architectural design of the stage station also suggests Swedish influence. Our excavations revealed a rectangular floorplan with sets of parallel rooms, each with their own chimney. This ‘dogtrot’ style was common in European Swedish and Finnish homes (Jordan Reference Jordan1983; Palmqvist Reference Palmqvist1987), and is now associated with the American South. Although uncommon in the American West, this log cabin style has been documented at several homestead cabins in the region (Dosch Reference Dosch1973; Bickenheuser Reference Bickenheuser2015).

We knew that traces of Indigenous presence would be difficult to recognise at the Nostrum Springs stage station, particularly following the widespread adoption of Euro-American manufactured objects into everyday life by the end of the nineteenth century (Silliman Reference Silliman2010). Although the stage station was located just steps from the reservation, Indian allotments and community life clustered 65km to the south-west; the eastern side of the reservation remained primarily uninhabited, except for copper-mining camps close to the mountain pass. The Shoshone and Arapaho experienced significant cultural trauma during the twentieth century (Fowler Reference Fowler1982; Stamm Reference Stamm1999a). They were often met with suspicion when they left the reservation, especially by White ranchers who were fearful that Native people would steal their livestock. During the early 1900s, ranchers often negotiated directly with Indian leaders for grazing permission (Stamm Reference Stamm1999b). Perhaps Jacob made similar arrangements, easing access for stagecoach travellers crossing through the reservation.

Unsurprisingly, evidence of Indigenous interaction at the stage station is indeed ambiguous. Hundreds of chipped-stone flakes recovered from sediments left by the collapsed sod roof and walls could, for example, represent earlier occupation phases, or Indigenous flintknappers re-sharpening stone tools next to the stage stop. A large, blue glass bead embedded in the wall mortar could have come from beadwork that was sold at the Fort Washakie trading post (Moore Reference Moore1955: 134); perhaps the bead was purposely concealed in the wall, in a similar manner to the porcelain button in the box.

A faded, red design that we noted painted on the interior wall of the stage station vaguely resembles Native pictographs. We were inspired by this image and initially interpreted it as an Indigenous symbol—as tangible evidence of interaction between Natives and Euro-Americans. Determining its cultural origin and age is challenging, with efforts to compare it to Plains design elements or even Swedish welcome symbols (i.e. the dala horse) proving unsuccessful. Interpretation of the painted design has now been aided by digital imaging technology that has sharpened the image into at least three diagonal lines, and has helped enhance the numbers written in pencil above it. Arranged in rows and columns, they indicate tallies, schedules and/or prices. This suggests that the figure was probably created by the homesteader family.

Red Canyon tipi rings

Written descriptions of trading posts and colonial settlements are often narrowly focused on the spaces within Euro-American and European settlements. As Native domestic spaces were situated elsewhere, they often go undetected (Lightfoot Reference Lightfoot1995). The road passing by the Nostrum Springs stage station wraps around a steep hill before turning south. We located previously unrecorded Native residential spaces on the other side of this hill. A barbed wire fence running through the site marks the boundary of the reservation (Figure 2). Across the fence is grazing pasture for the Arapahoe Ranch—a tribally owned organic cattle ranch established in 1940 (Fowler Reference Fowler1982), when the federal government restored unclaimed lands back to the tribes. Abandonment of the copper mines in the 1920s meant that no other settlements existed for many kilometres. At least two stone circles, or tipi rings, are partially buried in the short-grass prairie on the non-reservation side (Figure 6). Tipi rings represent the footprints of the former homes of mobile Indigenous residents. They are common archaeological features on the Plains, spanning the human occupational history of the region (Scheiber Reference Scheiber1993; Scheiber & Finley Reference Scheiber and Finley2010b). Following the decimation of bison herds during the mid to late nineteenth century, Plains Indians substituted canvas for hide tipi covers. As canvas rots when touching the ground, they often staked down the tipis with wooden pegs rather than traditional rock weights. These late period campsites are therefore particularly difficult to identify from surface evidence (Banks & Snortland Reference Banks and Snortland1995).

Figure 6. Red Canyon tipi ring campsite: stone circle 1 excavations, 2012 (photograph by L. Scheiber).

Systematic non-invasive metal-detector survey along with targeted excavations inside and outside the rings indicate that this campsite was occupied much later than we anticipated. The rings are large—6.5–7.5m across—with no visible doorway openings. In the first circle, we documented almost 700 small stone flakes, yellow pigment, wire, wire nails, small glass beads, boxer primers (for re-loading bullets) and a UMC .44 colt revolver cartridge. The second circle contained 500 metal can fragments, a single glass bead, yellow and red pigment, 1300 lithic flakes, a small obsidian projectile point and over 1000 highly fragmented animal bones. Many of these materials were recovered by water-screening sediments through 1.5mm mesh. Each circle also revealed multiple hearths and cooking features, with palaeoethnobotanical analysis identifying several edible plant species, grass seeds, juniper and sagebrush (Puseman Reference Puseman2012).

In total, we recorded over 50 pieces of identifiable metal, including can fragments, a pair of scissors, a button, several wire nails, a sharpened cut nail and flattened metal pipe, the revolver cartridge, primers and bailing wire. Recovery of the artefacts from undisturbed contexts within the interior space of the tipi structures strengthens our confidence that they were left by Native people who incorporated metal and glass objects into local Indigenous practices. The presence of wire nails and very small glass beads suggests that the site was occupied after 1890 (Scheiber Reference Scheiber1994; Wells Reference Wells1998; Martin Reference Martin2016), long after the introduction of Euro-American trade goods into the area, and possibly contemporaneous with the stage station. The side-notched arrow point is diagnostic of Shoshone material culture (Larson & Kornfeld Reference Larson, Kornfeld, Madsen and Rhode1994). Given the site's late date, we suggest that Shoshone people from the reservation camped here at the turn of the twentieth century.

The domestic artefacts demonstrate a creative use of old and new materials. Evidence for weapons and toolmaking comes from the cartridge, primers, arrow point and lithics, but also flattened cans, metal strips, cut lids and scissors (all associated with the manufacture of metal projectile points). Food preparation is demonstrated by fragmented animal bone and empty food cans, plus the wild edible plants and fuel from interior hearths. The sharpened nail/awl, button, pigments and glass beads relate to sewing, clothing and personal ornamentation. Although grass and wood recovered from within the house structures indicate fuel resources, they may also have served as insulating materials for tipi liners (Figure 7). Bailing wire, nails and the flattened pipe may have been used as lacing pins, thatch attachments and pole supporters for the tipis (Adams et al. Reference Adams, White and Johnson2000; Martin Reference Martin2016), which were still being held down with rocks.

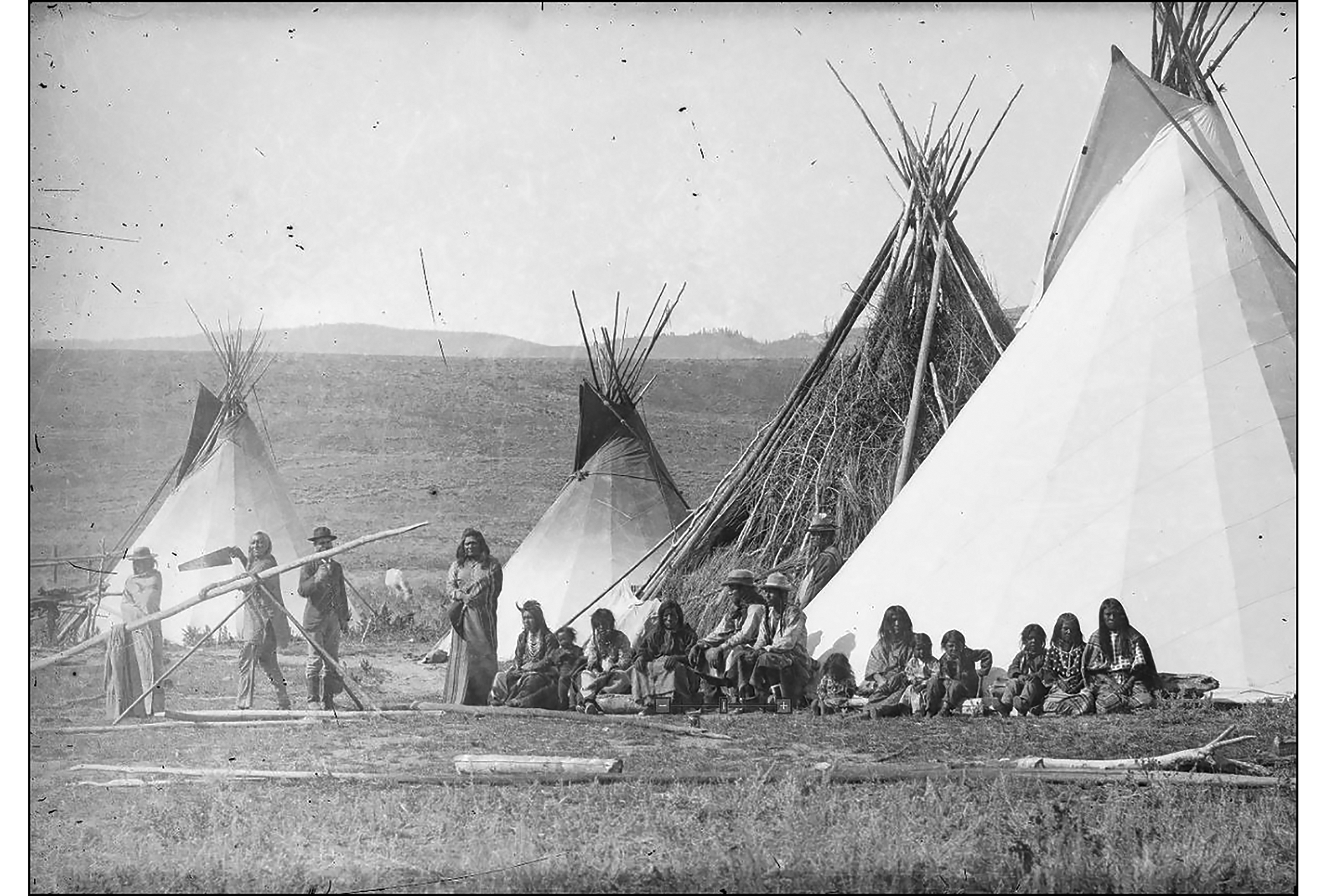

Figure 7. Shoshone encampment of Chief Washakie's extended family near Fort Washakie, 1884; Chief Washakie is carrying the saw. Note the materials and grass thatching (Baker & Johnston Collection, University of Wyoming, American Heritage Center, ah07420_006).

This campsite was occupied at a time during which leaving the reservation was difficult. The occupants may have been on unsanctioned hunting or resource-gathering trips and/or en route to the hot springs or a town celebration (Figure 8). Extensive archaeological deposits confirm that Êngkahonovita Ogwêvi was embedded with countless memories and stories, and that the canyon was considered a place of refuge. The occupants may have negotiated or traded with the Nostrum family and interacted with their children and the passing travellers. Regardless of the nature of the cultural overlap, we see clear evidence for interaction between Native consumers and the Euro-American market economy as represented by the innovative use of household materials at the tipi site. This site contests the notion of the rapid and complete replacement of Indigenous material culture with Euro-American objects, which remains a dominant theme in the history of the American West (Scheiber & Finley Reference Scheiber and Finley2010b; Newton Reference Newton2018).

Figure 8. Gift of the Waters Pageant, Thermopolis, Wyoming, 1925 (Indian-Pageant Photofile, University of Wyoming, American Heritage Center).

Riders Rock petroglyphs

Evidence for cross-cultural interaction at Red Canyon is not limited to domestic contexts. We recorded dozens of petroglyphs in the sandstone cliffs, depicting grooved bison hooves and pecked interior-lined figures, along with carved names left by the Nostrum children. The most notable example for the current study is rock art on a cliff overlooking the tipi campsite and south entrance to the valley: a faded, complex petroglyph panel inscribed on a 6m-tall boulder, which we have named Riders Rock (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Petroglyphs at Riders Rock (photograph and illustrations by L. Scheiber).

The panel comprises more than 20 incised and abraded outlines of humans, horses, tipis and weapons in raiding and combat scenes. Stylistically, the images fit into the regional biographical rock art tradition, which continued at least to the First World War (Lycett & Keyser Reference Lycett and Keyser2019). They also compare favourably to mid to late nineteenth-century fine-line images at site complexes such as Joliet and the Turner Rockshelter in Montana, and No Water and Seedskadee in Wyoming (Keyser & Poetschat Reference Keyser and Poetschat2005, Reference Keyser and Poetschat2009; Keyser Reference Keyser2007; McCleary Reference McCleary2016). The panel is extremely difficult to discern in the field, requiring comprehensive analysis with digital augmentation software. So far, we have recorded seven horses (some with reins and bridles), nine humans (several with headdresses or extremely long hair) and one or two tipis (representing escape from a campsite with a tethered horse). Weapons depicted include arrows, lances and, possibly, feathered staffs or coup sticks. We have so far been unable to identify any recognisable clothing styles, facial features, design elements or horse accoutrements.

Territorial intertribal warfare was extensive throughout the Plains in the nineteenth century as resource availability became strained due to Indigenous groups being pushed into new areas by American settlers. Plains Indian societies also engaged in combat to gain and maintain social status (Keyser & Klassen Reference Keyser and Klassen2001; Greer & Greer Reference Greer, Greer, Clark and Bamforth2018). Biographical rock art often depicts scenes demonstrating an individual's personal accomplishments or war honours, including counting coup (striking without killing), capturing weapons, raiding horses and fighting with enemies. These are narratives of past events, drawn at socially charged places close to actual battles and along well-travelled routes (Keyser & Klassen Reference Keyser and Klassen2001; McCleary Reference McCleary2016). Typically, these images are not associated with supernatural visions, although they are connected to the power that contributed to the success of the warrior-actors.

Plains biographical rock art is an example of a wider tradition of painting or drawing on cloth and paper (i.e. robe garments and ledger books). Most tribes had distinctive artistic styles, and rock art in the Red Canyon area has been attributed to Crow, Shoshone, Blackfeet, Ute and Comanche artists (Keyser & Klassen Reference Keyser and Klassen2001; Francis & Loendorf Reference Francis and Loendorf2002). Individuals from any of these groups may have created the images at Red Canyon in the mid to late 1800s, although the Shoshone and Crow were the most frequent occupants at that time. The petroglyphs probably pre-date the campsite and stage station, as they feature intertribal combat using horses—but only by one or two generations at the most—and it is highly likely that the campsite residents were well aware of the record of successful deeds on the rocky cliff above their tipis. This visual record is a reminder of the systemic conflict and cooperation that developed within local Indigenous cultural frameworks before Euro-American settlement.

Branding the landscape

Before concluding, we return to the red painted design at the stage station that inspired us to try to connect Indigenous and settler worlds. It did connect worlds, just not the ones that we anticipated. Amidst the names and sketches carved by the Nostrum children on the rocks above the stage station were symbols that we unconsciously recognised as brands: shapes representing the capitalist possession of livestock in unfenced country. Seasonal branding remains a family tradition in so-called ‘Cowboy Country’, and brands are a common local identity marker on barns, mailboxes and houses. Late in the current research, we realised that the Nostrums had carved Jacob's official brand (a quarter circle over diamond) on the name rocks and the sidewalk leading to the guesthouse (State Board of Live Stock Commissioners of Wyoming 1912: 176). In clearing away years of overgrowth, we had previously uncovered the date “May 16, 1916” on the guesthouse stairs. To the left of this, drawn in the freshly poured concrete, was the diamond, along with the three diagonal lines that we recognised from the stage station (Figure 10). Ranchers still use red paint markers for temporary livestock identification. In expecting the painted image on the stage station wall to be unknown and foreign, we failed to recognise something that was quite familiar. The symbols from the plaster wall, cliff rocks and concrete stairs all highlight the importance of cattle and horses at the Nostrum family ranch. A critical aspect of our research was to emphasise connected landscapes of memories and actions through time. The stairs over which we had climbed every day ultimately linked us back to this dynamic interplay of history, creativity and narrative, which we call the historical imaginary of Red Canyon.

Figure 10. Nostrum family brands: upper left) diagonal lines painted on the interior wall of stage station, digitally enhanced; upper right) X-A-quarter circle diamond carved on Nostrum name rock art panels; lower) R-YU, three diagonal lines and quarter circle diamond drawn in fresh sidewalk concrete in stairs leading to Nostrum's 1915 house (photographs and digital enhancements by L. Scheiber).

Conclusions

Our work at Êngkahonovita Ogwêvi offers new insights into the social and material effects of settler colonialism in the American West. The evidence at Red Canyon provides a narrative of cultural expansion, immigration and persistence. It is not a story of an isolated frontier, but a borderland for the exchange of ideas and materials among people from many nations, religions, occupations and backgrounds. While the sites are not all contemporaneous, like overlapping parts in a master sequence, they ultimately interlock.

At Nostrum Springs, we have uncovered evidence of a wide range of activities related to a farmstead and stage station owned by a Swedish-American family at the turn of the nineteenth century. Embedded cultural practices from the old country included the symbolic placement of objects and the log cabin's architectural style. This case study highlights the limitations of prioritising tradition over assimilation, and continuity over change. Amanda left Sweden during widespread immigration to the USA; Jacob was raised in an Illinois community born of frustration with Swedish political and religious leaders. Both had reinvented themselves in their new homeland, exemplifying the “dynamic cultural heritage” of the West (Dixon Reference Dixon2014: 177).

The tipi campsite highlights Indigenous lived experiences during a time neglected in American archaeology, which has prioritised initial contact encounters rather than post-reservation contexts. Despite disruption to settlement and subsistence, Shoshone people left the reservation to camp in tipis at Red Canyon, where they prepared and cooked traditional foods; and they also reloaded firearm cartridges and made arrowheads from stone and metal, illustrating both material innovation and cultural persistence. The mythology of Washakie's donation of the Thermopolis springs perhaps eased borderland racism, allowing people from the reservation to continue journeys to the mineral pools. Native people's participation in the Gift of the Waters pageant, however, does not imply that they relinquished their own voices to tell their history, control their heritage or claim connections to place (Watkins Reference Watkins2005; Atalay Reference Atalay2006; Blackhawk Reference Blackhawk2008).

The diverse symbolic representations at Red Canyon, from Riders Rock to the Nostrum brands, remind us that the lives of people were much broader than their residential spaces. We have identified visual records of their personal identities, their family obligations and their relationships with other groups and animals. Individuals from different cultural backgrounds marked the land with unique symbols of their accomplishments. These examples are reminders of people's profound connections to the land and their sense of place in the world (Basso Reference Basso1996; Cruikshank Reference Cruikshank2014).

By combining narratives from multiple archaeological sites, we sought to challenge dichotomies between prehistory and history, Native and Euro-American, change and continuity, immigrant and resident, and acculturation and tradition. Although it is perhaps conceptually easier to imagine the stage station, campsite and rock art as having separate life histories, a multi-scalar comparative perspective allows us to bridge the past and the present. Ultimately, cultural entanglement is an open-ended and long-term process that has produced the multi-ethnic and pluralistic societies that we know today.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to our collaborators: landowners Michael and Kathleen Gear, and geospatial expert Rebecca Mussetter. We also acknowledge the contributions of 55 project participants, including three Bighorn Archaeology field schools, student researchers, tribal and community members and friends. Reba Teran, language coordinator for the Eastern Shoshone, provided insight into connections between place and language and the importance of songs in everyday ritual. Noel Two Leggins, then-Crow tribal senator, and Burdick Two Leggins, then-Crow tribal historic preservation officer, participated in several seasons of fieldwork. Cherokee elder John Gritts from the U.S. Department of Education discussed twentieth-century Indian education with the field school students.

Funding statement

Funding and support were provided by Red Canyon Ranch, the National Science Foundation (#0714926) and Indiana University's Department of Anthropology and Office of the Vice Provost for Research.