Introduction

The purpose of this article was to review recommendations proposed by various guidelines and consensus statements for adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on transition from Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) to Adult Mental Health Services (AMHS) and for adults presenting for the first time to AMHS with a possible ADHD diagnosis. There is a lack of clarity, guidance and choice in Ireland for both of these patient groups in addition to economic restrictions on the mental health budget. Given the above, it is perhaps a starting point to develop Irish guidelines and hopefully service development will follow.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) ADHD Guideline group proposed three categories of service provision required for adults with ADHD. First, young people diagnosed and managed by CAMHS requiring ongoing care from AMHS. A second group of adults diagnosed in childhood but not receiving treatment whether through disengagement with services or having chosen to attend services but decline treatment. The third presentation is the adult querying a diagnosis of ADHD (NICE, 2008).

Adolescents on transition from CAMHS to AMHS

Up to 15% of diagnosed cases of ADHD continue to meet diagnostic criteria at 25 years of age, along with 50% displaying residual symptoms (Faraone et al. Reference Faraone, Biederman and Mick2006). Along with the continuation or development of comorbidities such as substance misuse and anxiety or mood disorders, a smooth transition from CAMHS to AMHS services has been advised (BAP, 2007; NICE, 2008; Barkley et al. Reference Barkley, Fischer, Edelbrock and Smallish1990).

Currently, CAMHS teams discuss options for follow on care with adolescents and their care-givers. If stable on medication, the young person may opt to follow-up with their family doctor. This may feel less stigmatizing or reassuringly familiar for families have attended their GP regularly for their medical card prescriptions while attending ADHD clinics.

In practice, there are few AMHS teams with specialized training, experience and adequately resourced in the United Kingdom and Ireland (Hall et al. Reference Hall, Newell, Taylor, Sayal, Swift and Hollis2013). CAMHS teams therefore tend to hold on to their older adolescent cases beyond the age cut-off given the scarcity of adult ADHD services and perceived difficulties transferring care (Young et al. Reference Ward, Wender and Reimherr2011). Adolescence is a known time of vulnerability and change, therefore it is important that any transitions in care are planned in advance and the service user is involved given that the young person will be taking responsibility for their healthcare needs (Young et al. Reference Ward, Wender and Reimherr2011). In particular, given the propensity of ADHD symptoms to lead to missed appointments and non-compliance, it is imperative that there are no barriers or care gaps. A study by McCarthy et al. (Reference McCarthy, Asherson, Coghill, Hollis, Murray, Potts, Sayal, de Soysa, Taylor, Williams and Wong2009) highlighted a disengagement from services by age 21. Given the symptom profile of ADHD and its comorbidities, these ‘lost to follow-up’ cases will utilize other services such as social services, accident and emergency departments, etc. (Liebson et al. Reference Liebson and Long2003).

The ‘ITRACK’ (Transition from Child and Adolescent to Adult Mental Health Services in Ireland) study evaluated service organization, policies, process and user and carer perspectives on the transition from CAMHS to adult services. Findings from the ITRACK study were that while transition is recommended, in reality it is still problematic in Ireland. Specific issues with transition were identified such as a wide variation in the transitional process with a lack of formal handover between CAMHS and AMHS team whereas written handovers were deemed adequate. There was an issue of access to services for 16–18 year olds. The study also found that the transition process did not involve a period of joint working between adult and child services, which is advised given the difference in service culture (McNamara et al. 2013). It should be acknowledged that there are examples of a smooth transfer of care from CAMHS to AMHS.

The NICE Guidelines recommend that adolescents should be transferred to adult services following reassessment using a Care Program Approach if they continue to have significant ADHD symptoms or comorbidities that require treatment (NICE, 2008). Advance planning between CAMHS and adult services with a formal handover meeting is advised to enable a smooth transition and involvement of the young person or carer in this process is advocated (Munoz-Solomando et al. Reference Munoz-Solomando, Townley and Williams2010). NICE recommends that adult services reassess any comorbidities and perform a comprehensive assessment of psychosocial functioning. The British Association of Psychopharmacology (BAP) Guidelines propose that AMHS in conjunction with primary care involvement should be sufficient to assess adolescents on transition and newly presenting adults.

Primary care involvement is advised if the young person concerned is stabilized on a longer acting medication. The main follow-up here would involve monitoring for side effects and the usual cardiovascular and weight checks.

Adult ADHD

The topic of adult ADHD is a contentious issue among mental health specialists in Ireland and indeed in many other countries (Kirley et al. Reference Kirley and Fitzgerald2002; Kooij et al. Reference Kooij, Bejerot, Blackwell, Caci, Casas-Brugue, Edvinsson, Fayyad, Foeken, Fitzgerald, Gaillac, Ginsberg, Henry, Krause, Lensing, Manor, Niederhofer, Nunes-Filipe, Ohlmeier, Oswald, Pallanti, Pehlivanidis, Ramos-Quiroga, Rastam, Ryffel-Rawak, Stes and Asherton2010; Turner, 2010). With the recent publication of DSM-V in 2013, the diagnostic criteria are now quantified and qualified clearly for physicians. Adult mental health clinicians had expressed reluctance to manage adult ADHD cases due to the past lack of diagnostic clarity and due to concerns prescribing controlled medications that may lead to addiction issues (Stockl et al. 2003). These fears are further compounded by the fact that stimulants are unlicensed for use in adults in most European countries (Kooij, Reference Kooij, Bejerot, Blackwell, Caci, Casas-Brugue, Edvinsson, Fayyad, Foeken, Fitzgerald, Gaillac, Ginsberg, Henry, Krause, Lensing, Manor, Niederhofer, Nunes-Filipe, Ohlmeier, Oswald, Pallanti, Pehlivanidis, Ramos-Quiroga, Rastam, Ryffel-Rawak, Stes and Asherton2010). There is a lack of long-term outcome studies on the efficacy of psychostimulants and other medications used in the management of ADHD (Kirley et al. Reference Kirley and Fitzgerald2002). Stimulants are not advised during pregnancy and breastfeeding and are contraindicated in psychotic disorders, all of which may complicate the management of adult ADHD (Kooij, Reference Kooij, Bejerot, Blackwell, Caci, Casas-Brugue, Edvinsson, Fayyad, Foeken, Fitzgerald, Gaillac, Ginsberg, Henry, Krause, Lensing, Manor, Niederhofer, Nunes-Filipe, Ohlmeier, Oswald, Pallanti, Pehlivanidis, Ramos-Quiroga, Rastam, Ryffel-Rawak, Stes and Asherton2010).

There are yet many questions to be answered for the management of ADHD, even in established adult ADHD clinics, such as the recommended frequency of follow-up appointments and how best to treat comorbidities (Morris, Reference Morris2012, ADHD Educational Institute).

The separation between child psychiatry and AMHS can further compound this stigma (Kooij, Reference Kooij, Bejerot, Blackwell, Caci, Casas-Brugue, Edvinsson, Fayyad, Foeken, Fitzgerald, Gaillac, Ginsberg, Henry, Krause, Lensing, Manor, Niederhofer, Nunes-Filipe, Ohlmeier, Oswald, Pallanti, Pehlivanidis, Ramos-Quiroga, Rastam, Ryffel-Rawak, Stes and Asherton2010). Adult psychiatrists may view adult ADHD symptoms as akin to those of emotionally unstable personality disorder or a mood disorder, therefore increased awareness and training needs to be provided (Turner, 2010). Views from some adult services are that patients present in the hope of a diagnosis of adult ADHD to be prescribed a ‘lifestyle enhancer’ (Turner, 2010). Some individuals may perceive a diagnosis of adult ADHD as more desirable than that of emotionally unstable personality disorder or substance misuse (Kirley et al. Reference Kirley and Fitzgerald2002).

Prevalence

Prevalence rates for adult ADHD are estimated to range from 2% to 5% (Kooij et al. Reference Kooij, Bejerot, Blackwell, Caci, Casas-Brugue, Edvinsson, Fayyad, Foeken, Fitzgerald, Gaillac, Ginsberg, Henry, Krause, Lensing, Manor, Niederhofer, Nunes-Filipe, Ohlmeier, Oswald, Pallanti, Pehlivanidis, Ramos-Quiroga, Rastam, Ryffel-Rawak, Stes and Asherton2010). There is a noticeable lack of data on the prevalence rates of Irish adults with ADHD who are either newly diagnosed or attend AMHS or their general practitioner. One Irish study screened adults attending outpatient mental health services and found 24% met criteria for ADHD based on the adult ADHD Self Report Scale but none had been recognized by their treating clinician (Syed et al. Reference Stockl, Hughes, Jarrar, Secnik and Perwien2010).

Dr Jessica Bramham, an Irish clinical neuropsychologist with an interest in adult ADHD deduces that given a US prevalence rate of 4% of adults with ADHD (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Adler, Barkley, Biederman, Connors, Demler, Faraone, Greenhill, Howes, Secnik, Spencer, Ustan, Walters and Zaslavsky2006), Ireland’s equivalent prevalence rate could be estimated to be up to 120 000 adults (www.stpatricks.ie).

Symptom profile

Adults with ADHD experience inner restlessness, over-talkativeness and an inability to sit still for long periods when required, that is, at church/meetings. Increased inclination to fidget, or a constant need to be on the go categorize the hyperactivity described in childhood onset ADHD. Impulsive symptoms are manifest as sensation seeking behaviours, moving jobs/relationships on impulse, impatience and acing without thinking. Inattentiveness presents as tardiness, distractibility, disorganization and being bored.

A typical ADHD adult is described as unable to settle after the age of 30, having moved jobs and changed relationships and usually underachieving in life (Kooij et al. Reference Kooij, Bejerot, Blackwell, Caci, Casas-Brugue, Edvinsson, Fayyad, Foeken, Fitzgerald, Gaillac, Ginsberg, Henry, Krause, Lensing, Manor, Niederhofer, Nunes-Filipe, Ohlmeier, Oswald, Pallanti, Pehlivanidis, Ramos-Quiroga, Rastam, Ryffel-Rawak, Stes and Asherton2010). As is described with children with ADHD, relationships and occupational functioning are impaired due to untreated ADHD along with an increased likelihood to accidents.

Gender

Evidence suggests that equal numbers of women and men are affected with ADHD as adults (Murphy & Barkley, Reference Munoz-Solomando, Townley and Williams1996; Rowland et al. Reference Rowland, Lesesne and Abramowitz2002). In contrast to childhood onset ADHD, where boys outnumber girls, females have featured in higher numbers with adult ADHD in some clinical studies (Biederman et al. Reference Biederman2004; Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Adler, Barkley, Biederman, Connors, Demler, Faraone, Greenhill, Howes, Secnik, Spencer, Ustan, Walters and Zaslavsky2006). This feature may be due to recognition bias in that girls are referred later given the diagnosis tends to be viewed as a male disorder and they present with a more inattentive profile than hyperactivity (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Adler, Barkley, Biederman, Connors, Demler, Faraone, Greenhill, Howes, Secnik, Spencer, Ustan, Walters and Zaslavsky2006). Another theory for this later presentation is that girls tend to have more internalizing problems such as chronic fatigue and inattention. Another factor may be that women tend to seek help and attend clinics more often than men (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Adler, Barkley, Biederman, Connors, Demler, Faraone, Greenhill, Howes, Secnik, Spencer, Ustan, Walters and Zaslavsky2006).

Comorbidities

Up to 75% of adults with ADHD will have one comorbid disorder and 33% will have two or more (Biederman et al. Reference Beirne, McNamara, O’Keeffe and McNicholas1993). Adults with ADHD can present with a range of comorbidities such as substance misuse disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder and personality disorders (NICE, 2008) along with mood and anxiety disorders, learning difficulties and other neurodevelopmental disorders (Murphy et al. 2002). Clarification of the primary diagnosis in this patient group can be challenging given diagnosis is dependent on a past clinical history prone to recall bias. Diagnosis is further complicated by the fact that comorbidities such as substance misuse and personality disorder have similar presentations (Kirley et al. Reference Kirley and Fitzgerald2002). The Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS) is recommended to distinguish comorbidities from ADHD symptoms (Kirley et al. Reference Kirley and Fitzgerald2002) (Table 1).

Table 1 Psychiatric comorbidity in adult ADHD

Shekim et al. (Reference Shekim, Asarnow, Hess, Zaucha and Wheeler1990); Biederman et al. (Reference Beirne, McNamara, O’Keeffe and McNicholas1993); Barkley et al. (Reference Munoz-Solomando, Townley and Williams1996); Murphy & Barkley (Reference Munoz-Solomando, Townley and Williams1996); McGough et al. (Reference McGough, Smalley, McCracken, Yang, Del’Homme, Lynn and Loo2005).

Driving safety

Young drivers with untreated or sub-optimally treated ADHD have a twofold to fourfold increased likelihood of driving accidents versus their non-ADHD peers. Adults with ADHD who are untreated or sub-optimally treated are three to four times more likely to have a history of driving accidents and fines (Jerome et al. Reference Jerome, Segal and Habinski2006; Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Barkley, Smallish and Fletcher2007).

Based on simulator studies, stimulant medication may reduce cognitive difficulties related to ADHD problem driving, however, there is limited data to prove this. The Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance (CADDRA, 2011) Guidelines have a detailed section dedicated to evaluation of driving risk as the Canadian Medical Association Guidelines (2006) state that ADHD is a reportable condition if there is evidence of problem driving. Problem driving is defined as speeding, tailgating, road rage along with inattention and distractibility while driving. However, given most road traffic accidents happen in the evening, at a time when long-acting ADHD medications may have worn off, this raises the question of whether a driving assessment may prejudice an adult ADHD patient in terms of obtaining car insurance even when treated.

The reality in Ireland

There is one specialized private adult ADHD clinic in St. Patrick’s University Hospital Dean Clinic. A multidisciplinary team performs diagnostic assessments, which entail cognitive testing, collateral history and developmental history with further questioning on employment, educational and medical history. This service offers follow on care in the form of medication, group workshops, motivational interviewing, solution-focused therapy and other psychological therapies.

A recent review of adult psychiatrists in Ireland (n=91) found that the majority also accept the validity of the diagnosis, are willing to accept new cases for assessment (67%) and continuation of treatment (66%) but expressed a lack of confidence in managing cases (Beirne et al. Reference Biederman, Faraone, Spencer and Wilens2013). It was encouraging to note that 74% indicated that adult ADHD should be a diagnostic category in DSM-V. This suggests that CAMHS clinician’s views of AMHS not accepting ADHD referrals needs to be reconsidered and highlights a willingness to develop adult ADHD services by adult psychiatrists.

However, as the majority of AMHS in Ireland are catchment based, it means that for the majority of adults seeking assessment or follow on care, this is with their general practitioner if he/she is willing. There are a range of private clinicians (psychiatrist and psychologists) nationwide, however, these do not have multidisciplinary teams.

Adult ADHD in other countries

In England, a number of specialized NHS Trust adult ADHD clinics were set up in the wake of the 2008 NICE Guidelines publication. These NHS funded clinics are catchment based. Unfortunately, some have since closed as they were classified as a low priority for funding by trusts. In other cases, referrals are contingent on an individual case panel process according to a UK-based parent support website (www.aadduk.org).

The South London and Maudsley NHS Trust established a specialized adult ADHD outpatient clinic in the early 1990’s, which accepts referrals from GP/consultant psychiatrists nationwide if funding is provided by the primary care trust or GP consortium.

Scotland and Wales are similar to Ireland in that their adult ADHD services are at an early stage of development.

Selected international guidelines

The British Association for Psychopharmacology Guidelines 2007 and Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: update on recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology 2014

The British Association for Psychopharmacology produced a set of evidence-based guidelines for the management of ADHD in adolescents in transition to adult services and in adults. This group published an update document in 2014. These guidelines evolved following a consensus group discussion of available evidence on childhood ADHD, the transition of adolescents to adult services and on reviewing the growing literature on adult ADHD, in particular the licensing of new medications and service provision. The consensus groups comprised of psychiatrists, psychopharmacologists, psychologists, pharmacists and pre-clinical scientists. This document sought to draft comprehensive guidelines on best practice in this emerging field.

NICE guidelines (England and Wales) 2008

This guideline is relevant for the diagnosis and management of ADHD across the lifespan (from 3 years upwards). The guideline incorporates the care provided by primary, community and secondary healthcare professionals and educational services that have direct contact with and make decisions concerning the care of individuals with ADHD. There is a section which addresses adolescents transitioning from CAMHS to AMHS.

European consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD: the European network adult ADHD (BMC Psychiatry) 2010

This consensus statement review article was created by The European Network Adult ADHD to increase awareness of adult ADHD and to improve patient care in Europe. Drafted by 40 professionals with an interest in and experience of adult ADHD from 18 European countries, it details available screening and diagnostic tools and appropriate treatments.

The Canadian attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder practice guidelines 2011

These guidelines were produced by the CADDRA. They are aimed at specialist clinicians that manage patients of all ages and their families with ADHD. These guidelines stipulate that clinicians must complete the provided online training modules for adult ADHD. There is a comprehensive section dedicated to managing ADHD in adolescents but the guideline does not discuss adolescents in transition to adult services.

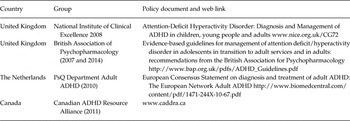

Other English speaking international psychological societies were contacted to ascertain if they had guidelines for adult ADHD. The American Psychiatric Association did not have any guidelines on the topic, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) did not have any guidelines either but advised the authors to consult the NICE and CADDRA guidelines, stating that they planned to develop guidelines in the future. The RANZCP website has an expert panel discussion on the advised guidelines available to view. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network have guidelines for ADHD in the younger generation, but not for the adult population (Table 2).

Table 2 International guidelines and consensus statements included in this article

Assessment of adult ADHD

NICE guidelines

The NICE Guidelines advise that assessment of adult ADHD should be in a secondary care setting and carried out by a psychiatrist or mental health specialist trained in the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD. Symptoms should have a clear history of origin during childhood with persistence through life. The clinician should adjust for age appropriate changes in behaviour when using ICD-10 or DSM-IV symptom criteria. The symptoms should not be due to another psychiatric illness.

Evidence of moderate/severe psychological, social and/or educational or occupational impairment should be demonstrated in two settings.

As per the other guidelines, a full clinical, psychosocial, developmental and psychiatric history should be obtained. Collateral history and a mental state examination should also be performed. Rating scales are adjuncts to diagnosis when there is doubt about symptoms. The NICE Guidelines do not advise as to suitable rating scales or use of a structured diagnostic format for assessment.

BAP guidelines

The BAP Guidelines 2014 propose an extended set of 20 adult symptoms, which incorporate both DSM-V and ICD-10 symptom criteria. Adult specific symptoms such as ‘trouble waiting if there is nothing to do’ were included. This guideline advises if a client has any pre-existing diagnoses to ensure assessment is started afresh.

The BAP guidelines state that general practitioners should be trained to be aware of the diagnostic criteria for adult ADHD.

Multiple sources of collateral history are preferred, ideally one developmental and one contemporary. Cognitive testing is recommended to diagnose comorbid intellectual disability, which differs to the other guidelines. Other neuropsychological tests are advised where indicated to allow for individualized treatment packages, which could improve functioning. The BAP guidelines clearly state that treatment response cannot be used to diagnose ADHD.

European consensus statement

The European consensus statement recommends a comprehensive diagnostic interview with the patient. Caution is advised to be aware of retrospective recall, which can lead to both under and over reporting. However, it states that if insight is good then accurate information can be obtained. The European Guidelines recommend the Connors Adult Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV, a structured diagnostic interview or the Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in Adults.

The interview should include a detailed past medication history (somatic and psychiatric) and to search for a family history of any psychiatric or neurological disorders. It is important to also ask if there is a family history of sudden unexplained death.

A collateral history from parent, partner or close friend to check for pervasiveness and severity of symptoms should be obtained. Various rating scales are discussed. These include the ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RSRS), The adult ADHD Self Report Scale Symptom Checklist (ASRS) as its name implies is specific to adult ADHD. It is particularly useful in those with substance misuse disorders. The guidelines details other rating scales such as the Brown ADD Scale Diagnostic Form (BADDS), Connors Adult Scale (CAARS) and the WURS. These rating scales are an adjunct to the diagnostic assessment.

CADDRA guidelines

The Canadian Guidelines advise to screen adults for ADHD who present with difficulties such as anger control and marital disharmony amongst many others. A current symptom screen is recommended in these cases by implementing the WHO Adult Self Report Scale (ASRS-V1.1).

If the screen is positive, CADDRA recommends checking DSM-IV criteria for ADHD and to exclude any other diagnoses that may mimic the symptoms. The ADHD Checklist should then be completed for current symptoms.

Again as with other guidelines, a developmental history is obtained to search for symptom onset in childhood. Collateral history to corroborate symptoms is advised. The ADHD Checklist is employed to retrospectively assess childhood symptoms.

Once a positive ASRS screen and a history of longstanding impairments are obtained, the clinician should complete a full psychiatric assessment for ADHD.

This structured screening approach differentiates CADDRA from the other guidelines. Functional impairment can be measured using the Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale-Self (WFIRS-S). As part of the assessment form, a list of risk factors is given such as caffeine and extreme sports.

CADDRA advises against using CAARS, BADDS and the Adult BRIEF Rating Scales to diagnose as all have inherent observer bias. The guidelines recommend only scoring questionnaires once the clinical history is completed. CADDRA also recommends the use of these scales for both screening and follow-up of symptom change when used serially and when the rater remains constant.

The Canadian guidelines highlight screening for arthritis from past injuries, obesity, poor dental hygiene along with more obvious ADHD specific medical issues. A urine drug screen is advised if there are grounds to suspect substance misuse/seeking behaviour.

To screen for comorbid disorders the Weiss Symptom Record is used as an adjunct to clinical history and is completed by both the individual and a longstanding partner/friend. Other rating scales may also be employed (Table 3).

Table 3 International guidelines for the assessment of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

Management of adult ADHD

NICE guidelines

The NICE Guidelines recommend psychoeducation with the patient and their spouse or other close relative. Medication is the first-line treatment option unless the patient prefers a psychological approach, in which case cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can be offered. Methylphenidate should be prescribed first, followed by Atomoxetine or Dexamphetamine second line if a 6-week trial of methylphenidate proves intolerable or ineffective. Caution is advised when prescribing Dexamphetamine to those at risk of stimulant diversion/misuse. Atomoxetine should be prescribed first line in this patient group. If symptoms continue with medication or there is no response to medication, group or individual CBT should be considered. The NICE Guidelines clearly state that antipsychotics should not be prescribed as a treatment option for adult ADHD. These guidelines provide detailed guidance on doses, side effect monitoring and management.

BAP guidelines

The 2014 update paper discusses the mode of action and recent changes to licensing of medications in Europe in particular. Detailed data on recent clinical trials are provided along with advice on drug titration and dosage and the use of medication in special patient populations such as pregnancy and lactation and substance misuse disorders is well documented in both papers. The guidelines advise that treatment is commenced by specialists. The 2014 update paper points out that drug holidays in adults are not a feasible option given the constant pressures of adult life, but flexible dosing is a potential option as per their day’s demands.

The 2007 BAP guidelines advise there is no prescribing hierarchy due to the limited evidence re-medications in the adult population, but that the choice of drug may depend on pharmacological factors other than efficacy, that is, abuse potential, side effect profile, etc. The more recent BAP 2014 update paper states Methylphenidate is prescribed first line in the United Kingdom given lack of choice with amphetamine formulations and the restrictive license of Lisdexamphetamine. If stimulant treatment shows no effect or the patient is unable to tolerate higher doses after an adequate trial, then a trial of non-stimulant medication, that is, Atomoxetine is advised. Third-line treatment options recommended are Bupropion, Modafinil, Tricyclic antidepressants, Clonidine and Guanfacine. There is a table provided which outlines formulations, half-lives and trade names of the listed medications. Mention is given to the coadministration of medications for resistant cases; however, the article advises there is limited evidence to support the efficacy or safety of such.

European consensus statement

The European consensus statement advises a holistic approach. Treatment consists of psychoeducation involving the patient’s partner and family initially. Stimulants (Methylphenidate and Dexamphetamine) are the first-line options with extended release formulations the preferred choice. Atomoxetine is advocated as a second-line treatment if there is no response to stimulants or their use is contraindicated. Other pharmacological options listed are Modafinil, long-acting bupropion and Guanfacine. Fourth-line agents such as Desipramine and other tricyclic antidepressants are stated to have evidence for use in this population. Antidepressants (except monoamine oxidase inhibitors), antipsychotics and mood stabilizers may be prescribed with stimulants according to the consensus group.

The consensus statement recommends that stimulant doses are tailored to the individuals’ response and tolerance and should not be calculated on a milligram/kilogram basis. Where substance misuse disorder is comorbid with ADHD, it advises that stimulant treatment is commenced only when illicit substance misuse has been treated, given the risk of stimulant diversion. The consensus group highlight that local regulatory rules apply for each country on the prescription of stimulants.

Coaching, CBT and family therapy are listed as helpful adjuncts particularly in cases with comorbidities; however, it is reported that there is insufficient evidence to support their efficacy as a standalone treatment.

CADDRA guidelines

The CADDRA guidelines recommend psychoeducation combined with behavioural intervention and a problem solving approach to address functional impairment. Information technology aides are also recommended to improve time management, compensate for impaired working memory and poor handwriting. Various websites for voice recognition software and organizational skills are listed along with suggestions such as programmable watches and PDA (Personal Digital Assistants) organizers.

The Canadian group advises that choice of medication is tailored to the patient’s profile bearing in mind comorbidity, risk of substance misuse, tolerance of adverse events and cost of medication. The guidelines provide a detailed regimen for commencing and titrating medications for uncomplicated ADHD. A maximum dosage for both product monograph and CADDRA board (off-label doses) is also included, which is helpful for physicians.

First-line agents are long-acting preparations such as Methylphenidate and Atomoxetine. Second-line medications can also be used as adjuncts and comprise short and intermediate-acting preparations such as Dextro-amphetamine sulphate. Third-line agents such as Imipramine, Bupropion or Modafinil are listed as off-label and are to be commenced by specialists only.

The Canadian guidelines advise that for optimal treatment, lifestyle changes must occur. Follow-up should be regular and with the patients general practitioner (Table 4).

Table 4 International guidelines for the management of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

NICE, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; BAP, British Association of Psychopharmacology; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; SUD, sudden unexplained death; CADDRA, Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance.

Licensed and unlicensed medications for adult ADHD in Ireland

Stimulant medications licensed to treat adult ADHD in Ireland include the Methylphenidate hydrochloride prolonged release formulation, Concerta XL. This product is licensed in Ireland for those with symptoms continuing to adulthood who show benefit from treatment. The product license does not allow for prescription to newly diagnosed adults as safety and efficacy is not established (www.medicines.ie). Another formulation of Methylphenidate hydrochloride prolonged release, Ritalin LA also has a license for the treatment of ADHD in adults in Ireland (www.medicines.ie).

Lisdexamphetamine dimesylate (Elvanse/Tyvanse/Vyvanse) is an inactive prodrug for Dexamphetamine. The license was issued in February 2013 in both the United Kingdom for use in adolescents with symptoms continuing into adulthood with an observed treatment response. Safety and efficacy have not been established for the routine continuation of treatment beyond 18 years of age (www.medicines.ie).

Atomoxetine hydrochloride (Strattera) is a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and has recently been licensed for use with adolescents on transition to adult services and newly diagnosed adults in Ireland (www.medicines.ie). It has no abuse potential and therefore may be prescribed in patients with substance misuse.

With regards to prescribing off-label for adults with ADHD, it is important to note that the BAP 2007 guidelines highlight the necessity for clinicians to prescribe unlicensed medications given the paucity of medication choices. However, these guidelines also quote the British National Formulary’s advice that a doctor’s professional responsibility is most likely increased when doing so. It is important to consider off-label prescribing in particular of controlled drugs in the context of a general practitioner offering shared care for adult ADHD cases. The BAP 2007 guidelines clearly state they support clinicians in prescribing unlicensed medications in the manner outlined in their detailed paper. It is important that a clinician clearly informs their patient if the medication prescribed is off-label and informed consent to be obtained and documented may be prudent in these instances.

Dexamphetamine (Dexedrine) and the Methylphenidate modified release formulation of Equasym XL are unlicensed for treatment of adults with ADHD (www.medicines.ie).

Guanfacine hydrochloride extended release (Intuniv) and Clonidine hydrochloride extended release (Kapvay) are both α2-adrenergic agonists and are licensed in the United States of America as monotherapy or adjuncts to stimulants in the paediatric population. A major European study for Guanfacine hydrochloride is currently at data analysis stage before a potential granting of license in Europe.

Antidepressants such as Desipramine and Venlafaxine are not commonly prescribed given their side effect profiles and they are unlicensed for use in Ireland along with sustained release Bupropion and Modafinil (Table 5, Figs 1–4).

Fig. 1 Proposed algorithm for the management of stable non-comorbid adult ADHD in Ireland. ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; CAMHS, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services; AMHS, Adult Mental Health Services; BP, blood pressure; HR, heart rate.

Fig. 2 Proposed algorithm for the management of non-stable comorbid adult ADHD in Ireland – GP consult re-medication change/suspected comorbidity. GP, general practitioner; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; AMHS, Adult Mental Health Services; MSE, mental status examination.

Fig. 3 Proposed algorithm for the management of non-stable comorbid adult ADHD in Ireland – GP referral of suspected new onset adult ADHD. ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; AMHS, Adult Mental Health Services; MSE, mental status examination; BP, blood pressure; HR, heart rate; GP, general practitioner; ECG, electrocardiography; BAARS-IV, Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale-IV; DARE, disability access route to education; IR, immediate release; LA, long acting.

Fig. 4 Proposed algorithm for the management of non-stable and comorbid adult ADHD- CAMHS transfer of adolescent to specialized adult ADHD AMHS/General AMHS. ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; CAMHS, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services; AMHS, Adult Mental Health Services; BP, blood pressure; HR, heart rate.

Table 5 Medication work-up

BMI, body mass index; CVS, cardiovascular; BP, blood pressure; HR, heart rate; ECG, electrocardiography.

Discussion

There are recent welcome clarifications to both the diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD. With the recent publication of DSM-V the diagnostic criteria for adults with ADHD has been clarified. As previously stated there has been a welcome addition to the treatment armamentarium with Atomoxetine hydrochloride recently licensed for newly diagnosed ADHD in adulthood and a decision is pending on the granting of a European license for Guanfacine hydrochloride. These new developments should provide structure and confidence for practitioners in managing this patient group.

The proposed model of care for the Irish context is for shared care between primary and secondary care. Those with stable non-comorbid ADHD which continues from childhood to adulthood can be managed by their GP alone with facilitated access to AMHS if indicated. Cases of unstable and comorbid ADHD or newly diagnosed adults can be managed by a specialized ADHD AMHS or general AMHS team. In cases of substance misuse comorbid with ADHD, the majority of guidelines advise treating the substance misuse first before focusing on treatment of the ADHD symptoms. For these cases, a specialist addictions AMHS service would be preferable to generic AMHS.

Any service development plan must account for cultural differences in attitudes and values between the CAMHS family centered and developmental model and the AMHS medical model. Consideration should be given to the increasing autonomy and responsibility of the young adult for his/her medical condition and the changing role of the parent/carer during this transition. As with the establishment of any new model of care, service user involvement is key. Dialogue between both CAMHS and AMHS and primary care is pivotal to ensuring seamless transition of adolescents with ADHD and to ensure that a comprehensive follow on service is developed for adults. Liaison with student and occupational health services should be implemented if indicated. Other countries have proposed that lifespan clinics would be the preferred option which would allow both longitudinal cohort and family studies of ADHD.

Given that all the guidelines mentioned in this article propose the ‘gold standard’ for a diagnosis of adult ADHD is based on a full clinical interview, most general adult psychiatrists are equipped to assess such cases. As adult ADHD as a topic is not included in mainstream training for psychologists, nurses and doctors there is a need for investment in training for multidisciplinary adult mental health teams and general practitioners.

Conclusion

Adult ADHD is an increasingly recognized condition with many recent positive developments in its diagnosis and clinical management.

We have reviewed a number of international guidelines and consensus statements regarding the diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD and summarized them in this paper. We have also used these international guidelines to propose guidelines for the management of adult ADHD in Ireland. Our proposed guidelines include less emphasis on medication and a stronger emphasis on psychoeducation than the NICE Guidelines. Our guidelines recommend medication usage in accordance with international recommendations, including some medications, which are not licensed for use in adults with ADHD in Ireland. It should be noted that the licensing situation regarding various medications may change over time, and readers are encouraged to familiarize themselves with the licensing situation for any drug prescribed.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank colleagues who proof read the paper.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.