9 Chamber music and works for soloist with orchestra

Of Vaughan Williams’s works that fall within the categories discussed in this chapter, only The Lark Ascending is widely known.1 The general listener might also have come across the Tuba Concerto: as a rare instance of a serious virtuoso work for that instrument, this has the occasional airing. But the rest of the composer’s works for chamber ensembles or for a soloist with orchestra are probably known only to specialist performers, Vaughan Williams scholars, CD completists (most of the chamber music, even the earliest, exists in recordings, as do all the concertos) and audiences who have come across them at concerts they have attended primarily in order to hear other works on the programme. Yet there is much of interest in this music: the stylistic characteristics by which Vaughan Williams is generally recognized are as much on display as in better-known works, as are his music’s strengths and weaknesses, and the broad lines of his development. With the possible exception of The Lark Ascending, it would require a good deal of special pleading to place any of the works I am considering within the highest reaches of his output. But some of the invention is highly imaginative and there are moments, too, of that quality of ‘vision’ for which the composer is renowned.

While the pairing of categories in this chapter represents to some degree a marriage of convenience, a compromise inevitable in a volume of this kind, there are, in fact, interesting common concerns as well as illuminating differences of approach that can be traced between the two groups of works (as there are, of course, with the rest of Vaughan Williams’s output). As it happens, with the exception of the work for tuba, the concertos were written between the periods of composition of the main chamber pieces. Approaching the task chronologically, my narrative therefore begins with chamber music, moves to four of the concertos, and ends by contrasting the contemporaneous Violin Sonata and Tuba Concerto.2

The early chamber music: finding a voice

Vaughan Williams’s first acknowledged chamber work is the String Quartet No. 1 in G minor (1908–9; revised 1921). A number of earlier pieces were withdrawn by the composer, and remained in manuscript until his widow, Ursula, lifted the embargo forty years after his death, and allowed a number to be published by Faber Music. The earliest of these is effectively Vaughan Williams’s first completed attempt at an extended original composition, the String Quartet in C minor (1898). This shows some flair for string-writing, even though the textures never exceed the conventional. Particularly impressive is the fleet, scherzo-like music in the Trio, which derives much of its impetus from rhythmic disruption. If the liking for (and, in some ways, the manner of) development suggests a Beethovenian model, the minuet-like Intermezzo suggests Haydn in its asymmetrical phrasing. Meanwhile the modality for which the mature Vaughan Williams is known is incipient at most. The opening of the first movement is consistently Aeolian up to bar 28, the only harmonic deflection from the tonic C minor triad being the Neapolitan in bar 15. More varied colours, in both timbre and harmony, are found in the expansive Quintet in D major for clarinet, horn, violin, cello and piano of the same year.3

Breadth of utterance is another characteristic of the mature composer and is a notable feature, too, of the Piano Quintet in C minor (1903), which comprises three big, ambitious movements, each lasting around ten minutes. These movements are, generally speaking, impressively paced, suggesting an embryonic symphonist. A sense of trajectory across the span of the work is achieved by inserting pre-echoes of the finale’s main theme in the first two movements (from bars 186 and 277 in the first movement, and from bars 55, 99 and 171 in the second). The style is post-Brahmsian, nowhere more so than in the bold opening gesture. But the music also shows the influence of Parry in its investment in the expressive potential of diatonic dissonance (see, for example, bars 1–7 in the second movement)4 – though non-dissonant diatonic contexts such as from bar 139 in the first movement also make their mark. Indeed, it is these moments – mostly wistful, often slightly pained – that make the biggest impression, rather than the chromatic working-out. All three movements end quietly, with melodic descents and a sense of withdrawal – precursors of the ‘niente’ endings for which Vaughan Williams was later to become famous. There is a tendency towards over-writing, and his writing for piano (for which he was criticized throughout his career) has more than a few awkward moments, especially when he is attempting to forge his own manner of modal harmony and voice-leading (in, for example, the harmonized repeats of the final movement theme).

Three years later, in the Nocturne and Scherzo (1906), the problem of how to integrate separate and radically different resources (a vein of late Romantic chromaticism that is more reminiscent of Bridge, and two kinds of diatonicism – the appoggiatura-laden version inherited from Samuel Sebastian Wesley and Parry noted in the Piano Quintet (see n. 4), and the modality of the folksongs in which he had an increasing interest) seems to come to a head. As Kennedy observes of the contemporaneous In the Fen Country: ‘The harmonic idiom is a curious mixture of the chromaticism of Strauss and his imitators, the pure diatonic style in which Butterworth was to write, and occasional glimpses of the Vaughan Williams of a few years later’.5 While there is no hint of folksong in the Nocturne movement, various moments of melancholic yearning convey an English tone. See, for example, the events from bar 91 to the end – the long descent from the climax, the nostalgic return to the opening bars and the listless cadence on to an added-sixth chord. Folksong does play a part in the Scherzo movement (which is actually subtitled ‘founded on an English Folk-song’: Vaughan Williams had started collecting folksong three years earlier in 1903), principally in the Lento section towards the end, though elements of the song do also appear in the Scherzo section proper.

When the String Quartet No. 1 in G minor received its first performance in 1909, the purportedly specialist audience was, if the report in The Musical Times is accurate, if not hostile then certainly dismissive:

SOCIETY OF BRITISH COMPOSERS.

A meeting of this Society was held at Messrs. Novello’s Rooms on November 8. String quartets by Dr. Vaughan Williams and Dr. James Lyon were performed by the Schwiller Quartet. There were passages in Dr. Vaughan Williams’s work which, on the assumption that the composer’s aims were fully carried out by the executants, represented the extreme development of modernism, so much so that not even the advanced tastes of an audience of British composers could find everything in them acceptable.6

To the audience of today, cognizant, say, of Schoenberg’s works of 1909 (Erwartung Op. 17, Five Orchestral Pieces Op. 16, Das Buch der hängenden Gärten Op. 15 and Drei Klavierstücke Op. 11), the notion of Vaughan Williams’s music representing ‘the extreme development of modernism’ seems absurd. Indeed, despite the modal resources (the quartet begins with a theme in G Dorian, and the main material of all four movements is modal) and a classicizing tendency at certain points (perhaps the result of studying with Ravel in Paris the previous year), much of the work is conservatively Romantic. It is possibly these elements that the Grove writers are thinking of when they say that the ‘traces of former ways, usually involving a chromatic expressiveness’ constitute ‘a serious handicap’.7 Peter Evans observes that ‘A sonata plan can be read into the first movement, but the progress is desultory and quartet dialogue minimal; the surprisingly grazioso minuet and the jiggish rondo-finale are more successful’.8 He does not mention the third, slow movement. Entitled ‘Romance’, it is notable for its obliquity: no cadence is other than equivocal, while the opening theme suggests several possible ‘tonics’ (the proper modal term would be ‘final’), none of which is confirmed by supporting harmony. The coda is characterized by the unexpected ‘discovery’ of the C major triad, one of very few pure triads in the movement; even this is presented in its least stable ![]() position, and has the seventh, B, pitted against it. Nevertheless, it is a moment of ‘revelation’ that is perhaps the most Vaughan Williams-ish aspect of the movement. Particularly uncharacteristic of the mature composer is the Romantic subjectivity: he adopts a personal, if not actually confessional, utterance, especially in the outer sections, rather than the ‘communal’ tone found in later movements titled ‘Romance’ or ‘Romanza’ (those, for example, in Symphony No. 5, the Piano and Tuba Concertos, String Quartet No. 2 and indeed in The Lark Ascending, which is subtitled ‘Romance’).

position, and has the seventh, B, pitted against it. Nevertheless, it is a moment of ‘revelation’ that is perhaps the most Vaughan Williams-ish aspect of the movement. Particularly uncharacteristic of the mature composer is the Romantic subjectivity: he adopts a personal, if not actually confessional, utterance, especially in the outer sections, rather than the ‘communal’ tone found in later movements titled ‘Romance’ or ‘Romanza’ (those, for example, in Symphony No. 5, the Piano and Tuba Concertos, String Quartet No. 2 and indeed in The Lark Ascending, which is subtitled ‘Romance’).

In both the Minuet and Trio and the Finale (Rondo capriccioso) a structural role is accorded to modal elements. Some of the elaborating chromaticism derives from the extension of modal qualities: for example, the parallel whole-tone scales in the violins in the Minuet at two bars after rehearsal letter C are readily heard as an extension of the whole-tone step at the top of E Mixolydian scale, E–D♮. This is a far more convincing use of the whole-tone scale than at the end of the first paragraph of the Romance, where it seems unmotivated. The whole-tone scale is also generated in this way in the Finale (see the three bars before rehearsal letter B and from five bars after rehearsal letter E to letter F). It is presumably these (relatively short) examples of whole-tonery that caused one of Vaughan Williams’s friends to say that he ‘must have been having tea with Debussy’ when he wrote the work.9

Writing the year before String Quartet No. 1 was revised and again saw the light of day, Edwin Evans noted that it

has been lost apparently beyond recall, and there remains only the Phantasy Quintet for two violins, two violas, and violoncello. This has had several performances, and has made a lasting impression on those who heard it . . . in my recollection it is one of the most characteristic works of its author, and one which makes lovers of chamber music regret that his contribution to their repertoire should not be more voluminous.10

The Phantasy Quintet was actually composed in 1912, two years after the Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis, Vaughan Williams’s ‘breakthrough’ work (in technique if not in terms of initial public recognition). So it is not surprising that there should be a much clearer sense of identity. Some of the Fantasia’s technical means of achieving rapt contemplation are on show in the Prelude, while the lento Alla sarabanda foreshadows the luminous, diatonic hymnic tone of the final movement of A Pastoral Symphony and the slow movement of Symphony No. 5. The work was commissioned by W. W. Cobbett, presumably to exemplify his chamber-music ideal of a one-movement, multi-sectional composition, though this particular piece is in essence divided into four separate movements (each linked to the next by an ‘attacca’).11 Vaughan Williams does, though, employ an integrative strategy he had essayed on a much larger scale in A London Symphony, on which he was concurrently working – the return of the opening melodic material in a ‘window’ near the end of the fourth movement (Burlesca). Material from the Prelude also returns in the development section of the Scherzo.

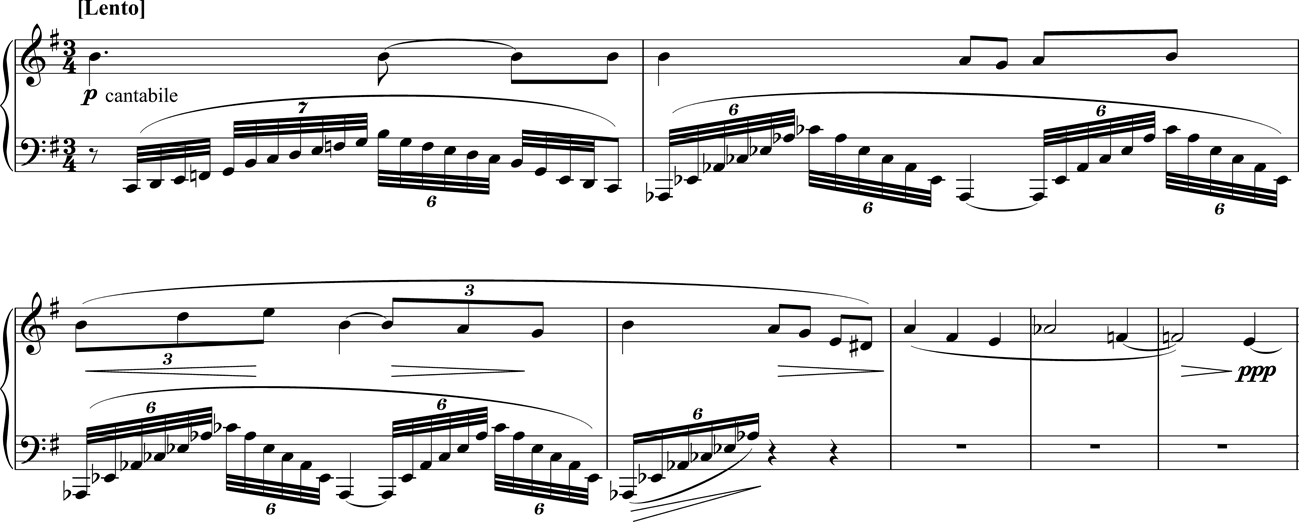

The success of the Prelude results in large measure from the simplicity of both materials and structure. The movement begins with a pentatonic melody rising from the bottom of the viola’s range. The pentatonic scale is devoid of semitones, with the consequence that, firstly, there is no inherent hierarchy: it is the metrical and rhythmic emphasis of the notes F and C that creates the sense of F as tonic. Secondly, there is no inherent sense of tension and release (there is no leading note demanding to be resolved to the tonic). It is primarily the latter that engenders the atmosphere of contemplation. After the second of the two types of material – triads moving in parallel – is brought into play, a second melody is introduced, employing the same pentatonic scale but this time descending from an f″ on violin I. The shape of the movement arises from the disposition and combination of this material. In the first section, the F centre is elaborated by shifts to the flattened mediant, A♭. The second section, meanwhile, starts with a shift to A♮: the harmony focuses on the A major triad (though this subsequently alternates with, and is supplanted by, the C that provides the route back to F), while both melodies are transposed to A: see Ex. 9.1. One could say that the melodies are counterpointed against each other, except that there is none of the propulsion normally associated with counterpoint: they are simply allowed to unfurl in the same modal ‘field’. The third section is the most exploratory harmonically, visiting as before first the flat, then the sharp side, but extending a little deeper into both. The movement is then rounded off with a literal repeat of the first melody. It is partly the recognition that regions of experience have been explored but ‘things remain the same’ that lends this short movement such a profound sense of melancholy. The Grove writers observe that in the Tallis Fantasia ‘hidden depths’ are revealed ‘contemplatively and obliquely rather than through direct dialectic’. The Prelude demonstrates this in miniature. It is a world immediately recognizable as Vaughan Williams’s own. It is not without dissonance (a ninth results from the voice-leading at four bars after rehearsal letter B, for instance, and the exact parallelisms after letter D result in a succession of false relations), but this enhances the contemplative state rather than supplying a destabilizing element.

Ex. 9.1. Phantasy Quintet: shift to A, 5 bars before rehearsal letter C.

It would be a mistake to view this as representing Vaughan Williams’s only authentic mode of utterance, however. As we have already seen, some of his finest apprentice music is to be found in scherzos, and the Scherzo in this Quintet strengthens the notion that he has a particular affinity for the genre. It is cast in sonata form, and it is in the development section that the material from the Prelude makes its reappearance: the initial harmonic succession recurs from five to seven bars after rehearsal letter E and the first melody from seven bars after letter F. Like the latter, the main theme of the third movement, Alla sarabanda, is pentatonic, and because of this a kinship with the Prelude may well be felt; but there is no actual thematic connection (at least, I cannot detect one, despite Vaughan Williams’s own statement that ‘There is one principal theme . . . which runs through every movement’12). The Burlesca, which starts on the cello (that instrument having been silent in the sarabanda) confirms the overall centre as D, though the final cadence in the subdued closing section is preceded by an alternative harmonization of the violin’s serene a‴ by F major, the tonic triad of the first movement.

The Phantasy is evidence that Vaughan Williams had purged himself of the stylistic traits of nineteenth-century musical Romanticism, even if his world-view remained in at least some sense Romantic.13 It could be argued that his voice was yet to emerge fully (the revision of A London Symphony in 1918 shows that he was tussling with how to respond to aspects of modernism), but the quality of lyricism was fully established. As I have suggested above, this is characterized by a sense of the collective: both the folksong resonances in the Phantasy, and derivations from English Renaissance music in the Tallis Fantasia, conjure up a repository of experience suspended outside time and evoke an authorial voice that is representative rather than personal and individualistic, even though the music is of course both of those things. This is consolidated in The Lark Ascending, which was initially completed in 1914, the year in which, in an article entitled ‘British Music’, Vaughan Williams discusses (however sketchily) the relationship between compositional individuality and communal utterance.14

Modality and melancholy: The Lark Ascending

Though composed just before the First World War, The Lark Ascending was not performed until 1920, by which time the composer had revised it. Subtitled ‘Romance for violin and orchestra’, it might be called a meditation on George Meredith’s sentimental (and, at best, third-rate) poem of the same name, extracts from which are reproduced at the beginning of the score. Vaughan Williams’s response is also often dismissed as sentimental, and too slight to be accorded serious scholarly attention.15 It seems likely to have been one of the works that provoked the epithet ‘cowpat music’.16 Yet it is a work of greater subtlety than has been generally acknowledged.

The term ‘Romance’ signals lyricism, of course, and, on this occasion at least, an essentially non-dialectical approach to form, as Table. 9.1, a précis after David Manning, shows.17 The Grove writers describe the work as ‘wholly idyllic, and therefore different in feeling from the post-war pastoral works’.18 It must be questioned, though, whether a ‘wholly idyllic’ scene is possible. As other writers have noted, only the outer sections are representational, the violin’s cadenzas enacting the lark’s song and ascending flight. I would suggest that a distinction between representation and commentary leads to an undermining of the idyllic – a distancing from the scene depicted that creates a powerful sense of loss.

Table 9.1 Formal summary of The Lark Ascending*

* adapted from David Manning, ‘Harmony, Tonality and Structure in Vaughan Williams’s Music’, II, 79

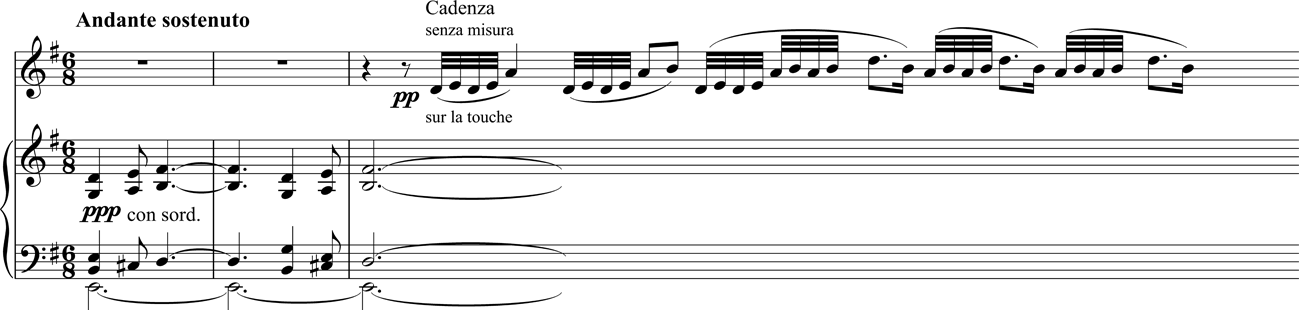

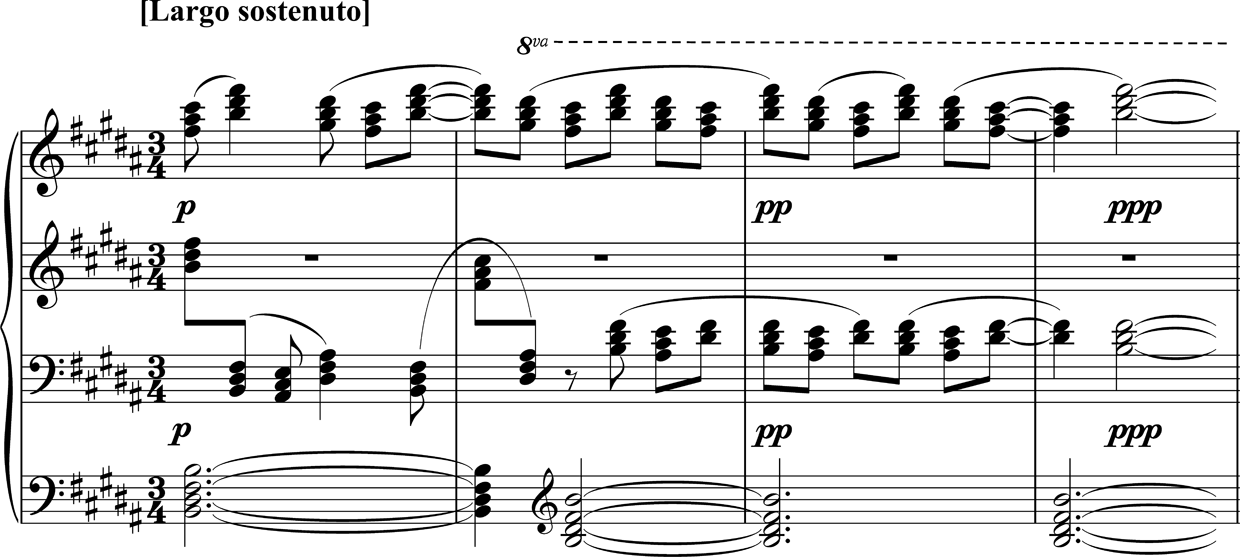

The opening of the work is reproduced as Ex. 9.2. The orchestral ‘introduction’, as Manning labels it, provides a frame that allows the representational world to come into being. Modality does some crucial work here. Firstly, for the listener used to common-practice tonality as the norm (arguably all of us in the industrialized West) it offers something ‘other’. Secondly, Vaughan Williams’s particular construction of modality here allows the underpinning major ninth chord to be dissonant without needing resolution, creating a symbol of time suspended. The pentatonicism of the cadenza similarly symbolizes effortlessness. However, when the orchestra becomes a mobile accompaniment in section A (see Table 9.1), and begins to introduce melodic material derived from the soloist, it takes on a commentating role that develops with the introduction of solos from four bars before rehearsal letter B. The passage for full orchestra at letter D is the first move away from the established modal field. Initially, this proceeds without the solo violin for the first time, and with a more forceful tone (a fuller sonority), but then the soloist joins in and actually effects the climax. In so doing, the soloist moves decisively away itself from representation into commentary;19 though the climax quickly subsides, it is not until the return of the opening material at four bars after rehearsal letter F that the initial point of view is recaptured, and it could be argued that even here the presentation is more of a reminiscence than ‘the thing itself’ (the reprise is, after all, truncated).

Ex. 9.2. The Lark Ascending, opening.

Section B begins with a new, folk-like melody in the flute, shifting the focus from the sky to ground-level and human activity: the cadenza heard earlier contained folk-like shapes, but these point towards the environment rather than connoting, as now, a community. The soloist’s music is essentially decorative in the first two of the three subsections, B1 and B2. Indeed, at the end of B2, from five bars after rehearsal letter Q, it becomes pure decoration once it has jettisoned the thematic oscillating minor third. This process of liquidation has the effect of emphasizing the soloist’s taking up of the flute melody in the return of B1 at letter R. In some ways this section can claim to be the linchpin of the work, in that the various reworkings create the clearest sense of nostalgia: the soloist’s assumption of the flute melody, the repeated cadences supporting the soloist’s languorous double-stopped descents, and the gently yearning suspensions in the soloist’s subsidiary line from six to ten bars after letter R (one of only two times the soloist has them20) all support the effect. After this the second return of the cadenza material is imbued with an even greater sense of loss, the ambivalent modal final and niente ending intensifying the melancholy as an already distant vision vanishes.

The importance of endings: three concertos and a quartet

The Lark Ascending is obviously a virtuoso work, even though the virtuosity most memorably consists in being still and quiet rather than loud and flashy. But it is also the relationship between the soloist and the orchestra that marks this as essentially a concerto – the clear differentiation of roles if not the outright opposition that is commonly viewed as the essence of Romantic manifestations of the genre. The Concerto in D minor for violin and strings (1924–5), written for the Hungarian-born but London-based virtuoso Jelly d’Aranyi at around the time she gave the first performance of Ravel’s Tzigane (1924),21 is cast in a more traditional mould. It was originally entitled ‘Concerto Accademico’, though exactly why has been a source of debate. Hubert Foss sees a hearkening back to pre-Romantic approaches: ‘The implication is not derogatory, as “academic” (a word of different meaning in our modern world) is used in England: only that the form derives from the eighteenth-century concertos of Bach and his fellows’.22 A. E. F. Dickinson wonders whether ‘the ulterior motive is surely some jape, some desire to avoid the burden of a full-blown concerto, by a mock reference to the earlier type’.23 The Grove writers, meanwhile, see the work as ‘Vaughan Williams’s nearest approach to a Bachian “neo-classicism”’, and Kennedy observes a ‘tightly-wrought synthesis of neo-classicism, folk-dance rhythms and triadic harmony’.24 But it would be misleading to imply that the work represents a serious engagement with neoclassical principles. The structural organization derives from Vaughan Williams’s modal practice, and the neoclassical elements are largely surface phenomena, particularly in the second and third movements. In the first, the debt of the first-group material to baroque shapes and rhythms gives a certain degree of impetus, but has the effect of depriving the music of much sense of personality; and the more folky material, such as the new pentatonic theme that initiates the second half of the development at rehearsal letter L, has the ‘all-purpose’ air to which Vaughan Williams’s thematic invention is sometimes prone. But even if it is recognized that, like many composers who have a natural bent for symphonic composition, Vaughan Williams is generally more impressive for what he does with his material than for the quality of the material itself, the first movement is insufficiently inventive at the formal/structural level to make much impact.

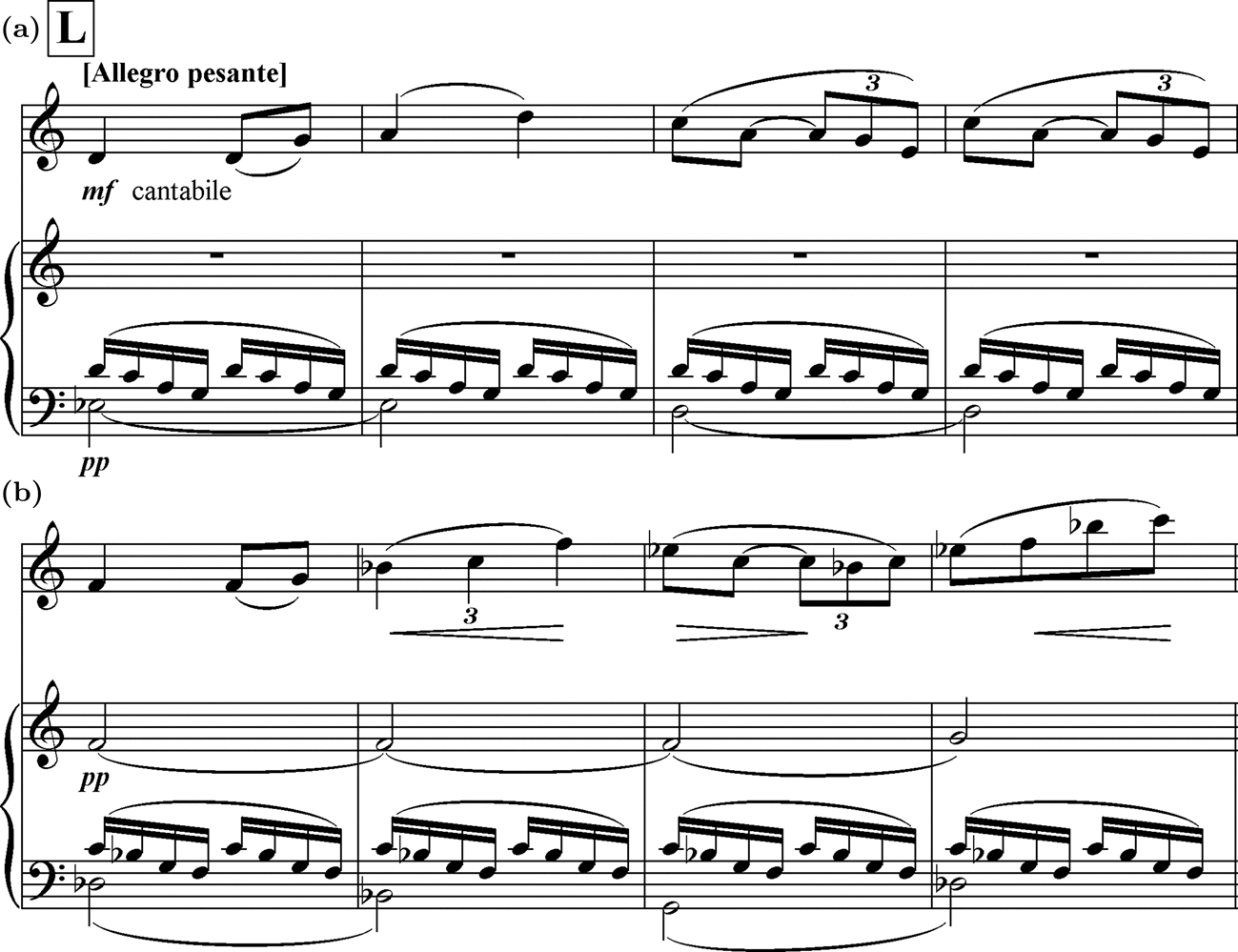

One aspect worth noting, though, is the technique of planing. Ex. 9.3 shows two instances: (a) is the beginning of the pentatonic theme mentioned above, in which the soloist and lower strings, which inhabit the same mode, are pitted against a sustained E♭ in the bass; the more protracted (b), which begins at rehearsal letter R, sees an f″-based layer pitted against a lower G♭-based layer. Both dissonances are quickly resolved, but planing (or bitonality, as it is usually called in the Vaughan Williams literature) takes on greater structural significance in later works, most famously in Flos Campi, completed in the same year as the concerto.25 It is employed in the second movement, too. Ex. 9.4 shows the coda, in which the upper strings elaborate a G triad (with the parallel triadic movement that was firmly established as a Vaughan Williams fingerprint by this stage) while the lower strings descend by step until there results a clash of E♭ against G that is sustained for three bars. As in the first-movement examples, the tension is relatively local, almost colouristic: the E♭ level simply drops away to leave G unchallenged.

Ex. 9.3. Violin Concerto, first movement, instances of planing: (a) rehearsal letter L; (b) rehearsal letter R.

Ex. 9.4. Violin Concerto, second movement, coda, instance of planing.

Tovey says of the ending of the Presto finale that it is the ‘most poetically fantastic and convincing end imaginable’.26 It is certainly the most impressive movement, and again shows Vaughan Williams’s facility for the control of fast music. It is, though, the introduction of a broader melody from rehearsal letter U (a slowed-down version of the theme first stated at a bar after letter B) that sets up the ‘fantastic’ effect. The melody’s alternation between two versions, one in the acoustic mode27 and one in the Dorian, focuses increasingly on the equivocation between major and minor mediants that is fully crystallized at the very end of the movement. This concentration on the play of modal alternatives is possible because of the emergence of a strong tonic: a long dominant pedal beginning at two bars before rehearsal letter U is followed by a stepwise bass descent to D via A♭, G, G♭, F and E.

It can be debated whether the ending of the Piano Concerto (1926–31) is equally effective. The work underwent various revisions in 1933 and 1934, and a version for two pianos was made in 1946, before the revised ending emerged in 1947, changing the closing key from G to B.28 B is the key of a long piano solo that precedes the coda. As discussed further below, this solo passage prefigures the ending of Symphony No. 5 in its diatonic purity and ethereal ascent. But while the closing pages of the symphony complete a work-length trajectory, there is a patchwork quality about the Piano Concerto. This is epitomized by the first of the three movements,29 Toccata, which for all its energy gives an overall impression of being rather static. This is partly due to transitions often being engineered over the last bar or even last couple of beats of a section. But it is mostly to do with the handling of the form. Vaughan Williams’s own rather terse programme note, with its use of the terms ‘development’ and ‘recapitulation’, implies a sonata-form background.30 His listing of the thematic material suggests that the second group occurs at rehearsal figure 3, with a theme in B Aeolian. But this is not accorded the rhetorical force of a traditional second group, or indeed the length one would expect: whereas the work begins with twenty-four bars of C, the transition to the second subject group lasts just three bars; and the second subject group itself lasts only eleven bars (two short sentences of six and five bars in B Aeolian and F Aeolian respectively), before a further transition to the opening material in the tonic. Rather than setting up the traditional tonal dichotomy, Vaughan Williams’s purpose seems to be to set up a solid block of C major from which the rest of the music struggles to move away. The opening is sonically massive, the soloist playing a martellato semiquaver figuration over octave Cs supported by the brass, while the strings have a unison rising marcato line. It is the latter that embodies the straining against C, with a move from C Dorian to more dissonant Locrian inflections. In reference to the traditional expositional repeat, this music returns at rehearsal figure 5 with roles swapped. The hegemony of C is epitomized by the long C pedal in the development from figure 10, but also by the ease with which C returns after the ‘shortened recapitulation’ (as Vaughan Williams describes it) in A♭ for the final, Largamente section: the transition is effected in just three notes.

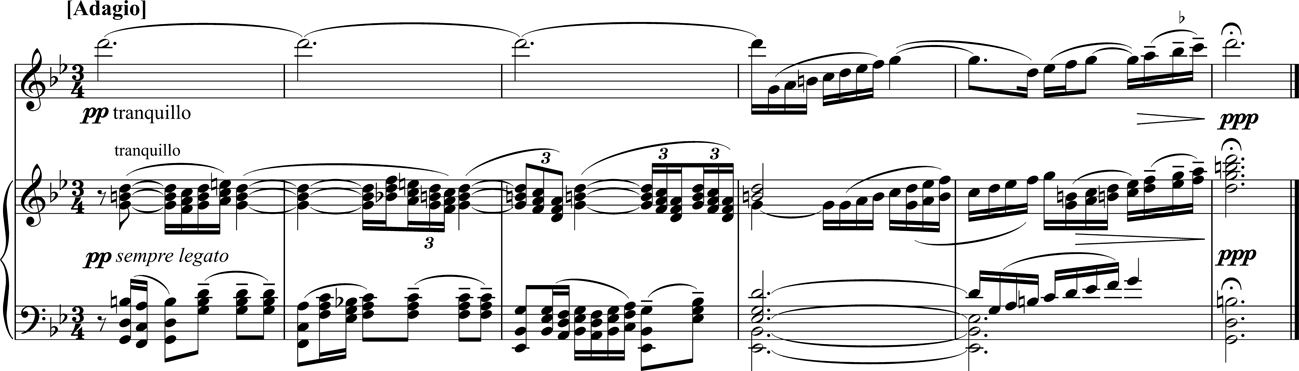

The Romanza is in ternary form. The opening of section A, which is itself ternary, is notable for its use of planing, the pentatonic tune being placed against various elaborated triads: see Ex. 9.5, which also shows the tune’s chromatic ‘tail’. In the central part of section A, E major emerges as the first clear key to support the initial melodic pivot, B. Such clarity, though, turns out to be fugitive: the harmonic underpinning of the next two phrases returns to ambiguity – a minor seventh built on C♯ major and the overlaying of E major and A minor triads. Section B, meanwhile, is largely diatonic and notable for chains of luminous suspensions: a putatively idyllic foil to the less stable outer sections.

Ex. 9.5. Piano Concerto, second movement, bars 7–13.

The final movement takes elements from the chromatic tail of Ex. 9.5 – in particular the pattern of a semitone followed by a minor third (e.g. C–B–G♯) amplified by the oboe and solo viola in the coda of the Romanza – as the basis for a chromatic fugue subject. This pattern, appearing in the bass, is the chief means of transition back to the tonic C in the first movement: see the bar before rehearsal figure 5 and the bar before figure 13 (this suggests a greater degree of unity across the work than the Grove writers allow). It is this fragmentary use of the hexatonic scale (so called because the replication of the interval pattern semitone–minor third across the octave results in six pitch classes), and the fugal writing itself, that most clearly marks the Concerto as ‘an interesting transition to the Fourth Symphony’.31 But it is the final section of the last of the three cadenzas, a reminiscence of section B of the Romanza, that is the most interesting music not only of the movement but also of the whole work. Cast in pure B major, it could be viewed, according to mood, as inspired or as a frankly lazy piece of composition. Ex. 9.6 shows the end of the section. As is the case throughout all of the section, there are three lines, each of which is filled out with parallel triads. The lines have to be arranged so that they are playable with only two hands, but the details of incidence are, I would suggest, otherwise inconsequential. Any dissonance is acceptable in this world so long as the tonic chord arrives at the end: the broad effect is what counts.

Ex. 9.6. Piano Concerto, third movement, end of final piano section.

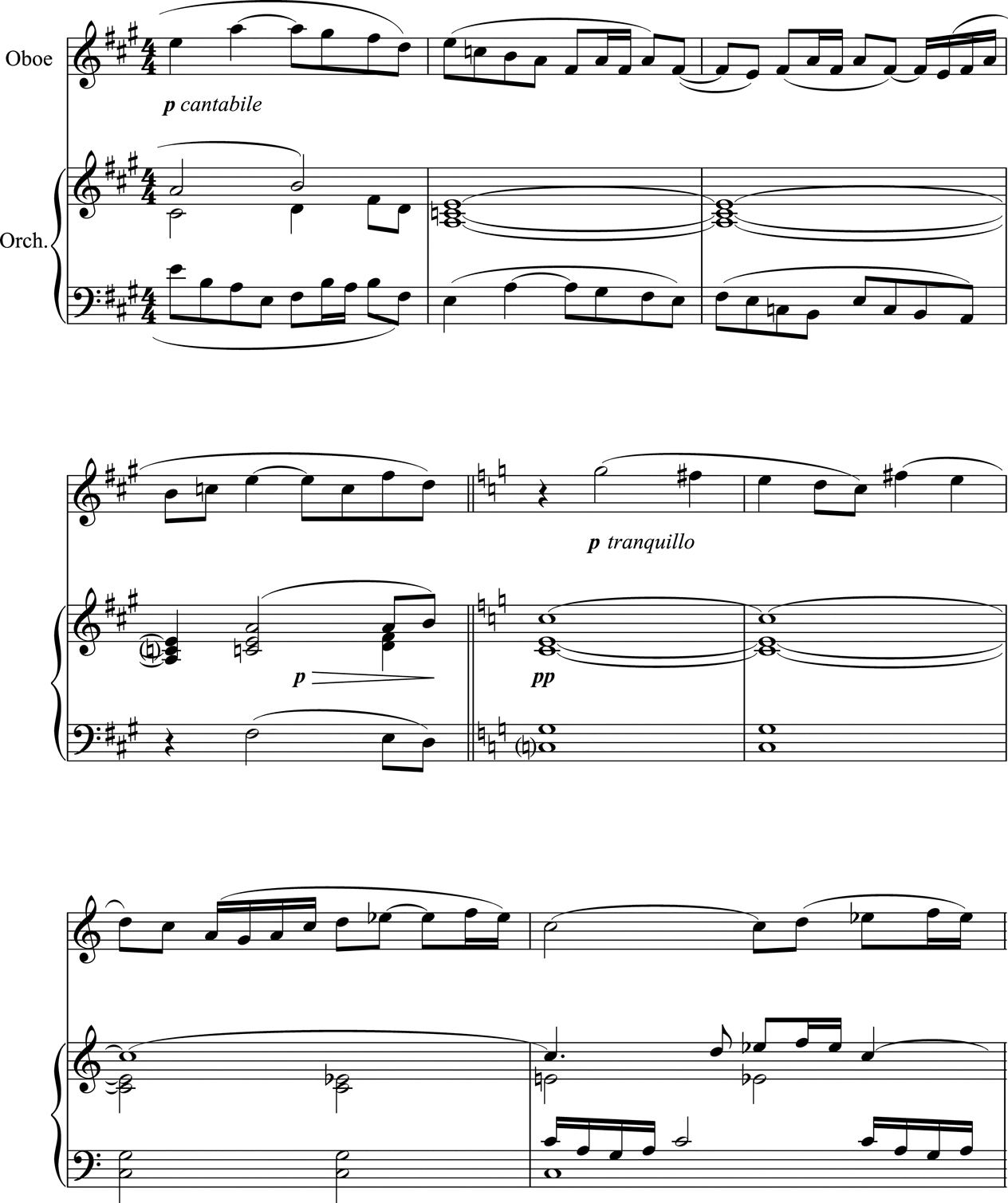

The Oboe Concerto of 1944 (which, like the Violin Concerto, is for soloist and strings) can be heard as a satellite of Symphony No. 5, completed the year before. The most obvious connection with the larger work is the pastoralism: the first movement of the concerto is actually entitled Rondo Pastorale, and double-reed instruments have long been associated with rural contexts. And the concerto, too, has a cyclic element: a pentatonic theme spanning an octave marks the beginning and end of each movement.

The form of the first movement is outlined in Table 9.2. The movement opens ruminatively, with a gesture not unlike the opening of The Lark Ascending, and the main theme is supported by the relaxed rotation of three chords (i, VII and IV); even the ensuing short cadenza seems to be taking it easy. Momentum picks up in section B, though the varied return of section A at rehearsal letter B eases down before section C picks up the pace again. Section D is quasi-developmental, drawing on the dotted rhythm that characterizes section C; section A themes emerge from rehearsal letter E onwards, literally underneath section D material. It could be claimed that the events in Ex. 9.7, which open a ‘window’ into the return of section B, are the key moments of the movement, ensuring that it ends with disquiet rather than the cosy glow in which it begins: when the window opens, it is on to a very different kind of stasis. C is not a new centre (it underpins much of section D), but the mode, the Lydian, is new (and relatively rare in Vaughan Williams), producing slightly more tension than the Dorian and Aeolian patterns that have prevailed up to this point, especially when the line leaps to F♯ and thus highlights the tritonal and semitonal dissonances with the underlying C triad. The subsequent juxtaposition of C major and C minor furthers the tension, and the alternation of E and E♭ returns to colour the coda, which finally settles on a rather despairing A minor.

Table 9.2 Formal summary of Oboe Concerto, first movement

Notes:

† G major is the same collection as the preceding A Dorian.

‡ C Lydian is the same collection as the preceding A Dorian.

Ex. 9.7. Oboe Concerto, first movement, C-Lydian ‘window’ during return of material from section B, 4 bars after rehearsal letter F.

The journey of the final movement, the longest, is rather different. The main material is of scherzo character,32 but the form is essentially sonata form, with a development from six bars before rehearsal letter L and the recapitulation from thirteen bars after letter R after the interpolation of what is in effect a slow movement based on material from the second group. There is a greater sense of melodic expansiveness in this movement, culminating in a broad theme from nine bars after letter V. Kennedy refers to this as a ‘passionate and regretful episode’. Dickinson, in a highly dismissive commentary, sees ‘the penultimate resort to a new tune in G major, traditional in style if not in fact’ as ‘desperate’; furthermore, ‘the abandonment of the original E modal minor is quite unpersuasive’.33 In fact, the ‘new tune’ is adumbrated at the end of the exposition, and E Dorian is little more than a starting point. It makes more sense to see the shape of this particular movement as being formed by balancing different characters of material and harmonic pacing rather than through tonal structure. The ‘new tune’ has some kinship with the hymnic music of the slow movement of Symphony No. 5, and as in that work the appoggiatura-laden diatonicism is indeed, despite the major mode, tinged with the sadness that Kennedy hears.

The last page of the contemporaneous String Quartet No. 2 in A minor (1942–4) also settles into pure diatonicism, though of the more serenely uplifting kind found in the closing pages of Symphony No. 5 (the correspondence is underlined by the use of the same key, D major, to which the music shifts from the F major of the first part of the movement). The final melodic utterance is given to the viola, which has a particular presence throughout because the work is dedicated to the violist Jean Stewart. The instrument also initiates all four movements. As Jeffrey Richards notes, ‘the main theme of the movement comes from the composer’s sketches for a score to a film about St Joan that never materialized’.34 Regarding overall shape, it is with some justification that Evans writes of a ‘suite-like succession’.35 Dickinson, too, says it is ‘Almost a short suite’, but he is surely wrong to say that it is ‘light-weight’.36 The slow movement, which is the longest (it is the length of the others put together) and one of Vaughan Williams’s least romantic ‘Romances’, is serious in mood, its contrapuntal senza vibrato opening and the ecclesiastical chordal chanting of the contrasting idea and eventual climax suggesting an aspiration towards the tone of Beethoven’s late quartets. And both the first and third movements display a degree of angst not encountered in any of the other works in this chapter. As Richards observes,

The Second String Quartet is a product of the same period of musical development as the Sixth Symphony and can be seen to share the same mood. The first three movements are bleak, anguished and jagged, and the scherzo repeats over and over again the stabbing motif that accompanies the Nazis in [the 1941 film] 49th Parallel, the title of which Vaughan Williams marked in his score against this movement.37

The first movement (another bearing the title ‘Prelude’) is in fact the only one that has anything to do with the titular A minor, and this only unambiguously at the end, where it emerges more to articulate the moment of the music’s withdrawal than to celebrate a point of arrival. This moment represents the dissolution of the considerable amount of energy generated at the beginning from a dichotomy between E minor and F minor triads (an opposition also crucial to the Sixth Symphony). Embedded within their oscillation is the semitone–minor third pattern, and this plays an increasing role, leading to several statements of a complete hexatonic scale, A–A, in Violin I towards the end of the development section (from five bars after rehearsal letter G to one bar before letter H). Whilst this does not yet fully focus A as a tonal centre, as the passage includes all twelve pitch classes of the chromatic collection, it does prepare for the eventual outcome; the middle stage in the process is the A minor triad that underpins the G♯-based reprise of the second subject at the beginning of the reverse recapitulation (from nine bars after rehearsal letter H).

The beginning of the third movement is also ambiguous, but in a different way. It begins with a whole-tone motif on viola, G–F–E♭–D♭ (Richards’s ‘stabbing motif’), and during the opening section either G or D♭ can be regarded as the ‘tonic’. Initially, because the rest of the ensemble emphasizes it, it seems that G is the tonic and that the mode is G Locrian. When the violins and cello have the motif and the viola sustains the D♭, that note appears to be the tonic and the mode D♭ Lydian. Both of these pitch classes are later asserted as key centres: G Dorian at the climax at rehearsal letter E, then D♭ at eight bars after letter G before the shift to F minor for the close.

Envoi: Violin Sonata and Tuba Concerto

String Quartet No. 2 received its first performance on Vaughan Williams’s seventy-second birthday. On his eighty-second birthday he was present at the first performance of a work with the same titular key, the Sonata for Violin and Pianoforte in A minor (1954). The role of the titular centre is this time more traditional: the first movement, Fantasia, begins and ends in some form of A (Aeolian at the start; more chromaticized but closing on the A minor triad at the end), and the work concludes with an A major triad. The middle movement, another scherzo, begins and ends in a relatively traditional related area, the subdominant, D. While the quartet is compact and highly focused, and one of the most impressive works discussed in this chapter, the Violin Sonata seems (certainly in the outer movements) diffuse and often routine: Evans’s complaint about the late symphonies that ‘the habits of composition have outlasted the impulse’ is perhaps appropriate here.38 He notes of the Sonata that the Fantasia ‘is in fact a sonata movement, propelled by those minor 3rd shifts prominent in the Fourth Symphony’,39 but the rather episodic – if frequently energetic – approach suggests that ‘Fantasia’ is indeed a more appropriate title. The Scherzo, driven by unpredictable accentuation and harmonic deflection, compels more sustained concentration. While there are moments of comparative quiet – at rehearsal figure 10, for example, and in the coda from figure 14 – rhythmic or harmonic tension is maintained. The Variations of the final movement are based on the theme from the last movement of the 1903 Piano Quintet, delivered at the outset in octaves by the piano. This is representative of the utilitarian aspect that frequently mars Vaughan Williams’s writing for the piano, whose part here often seems like an orchestral reduction: there is little attempt (apart from a few moments in the Scherzo) to explore the instrument’s characteristic sonorities.

The Tuba Concerto (1954) is much shorter (under fourteen minutes in contrast to the twenty-seven or so of the Violin Sonata), presumably in deference to the physical demands of the instrument, whose capabilities Vaughan Williams took ‘great pains’ to explore.40 The work benefits greatly from the reduced dimensions: there is a tighter structure, more sharply etched material, and it is much clearer what the composer is setting out to achieve. There is an obvious danger in writing a serious work for an instrument that, because of its size and perceived lack of agility, has often been characterized as comic, but Vaughan Williams takes the tuba into territory far away from caricature, especially in the second movement, Romanza. The music here perhaps risks sentimentality, particularly when the orchestra ‘corrects’ the tuba’s F♮ of the penultimate bar so that the movement ends on a tonic major triad that can seem a little too sweet, but otherwise the composer demonstrates once again the nostalgic, melancholic potential in pure diatonicism (see, for example, the tuba’s appoggiatura-laden descents from its second bar, and in particular the descent to low B, supported by a move from D major to B Aeolian, at the end of the first paragraph).

The outer movements may not be emotionally searching, but they sustain the listener’s interest in simple but effective ways: as Vaughan Williams’s own programme note announces, ‘The music is fairly simple and obvious and can probably be listened to without much previous explanation’.41 The first movement is an inventive sonata-form hybrid in which the development is concurrent with the recapitulation, such is the degree of reworking in the latter. The rumbustious finale – Rondo alla tedesca – relies on Vaughan Williams’s trademark alternative scale-degrees and chromatic sideslips to generate tension: see in particular the poco animato from five bars before rehearsal figure 9 that leads to the final cadenza. Set alongside the symphonies – including Symphony No. 9 (1956–8), which is relatively compact in comparison with all the others except No. 8 – the Tuba Concerto clearly has reduced ambitions. But it epitomizes Vaughan Williams’s (decidedly unmodernistic) desire, even to the end of his career, to meet the need for a broad range of musical experiences for performer and listener alike. And if it can be said that there is an aspect of ‘lateness’ about Symphony No. 9, the final works in both the chamber and concerto genres have nothing of this about them.

Notes

1 Its popularity in the UK can be gauged by its being voted ‘the top piece of classical music’ in the Classic FM Hall of Fame four years running between 2007 and 2010 (see www.classicfm.com/hall-of-fame/, accessed 30 May 2013; the website proclaims the work to be ‘No.1 for a 3rd year’). The work was also chosen as the focus of the BBC’s populist Culture Show, in a commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Vaughan Williams’s death broadcast on 8 July Reference Vaughan Williams and Cobbe2008: see www.bbc.co.uk/cultureshow/videos/2008/07/s5_e6_williams/index.shtml, accessed 30 May 2013.

2 Several of the works examined here were revised, sometimes more than once; a more expansive study would find considerable interest in comparisons, but here I address only the final versions. I will also not attempt to discuss here the Concerto for Cello and Orchestra that Vaughan Williams completed in short-score draft form in the early Reference Vaughan Williams1940s but never brought to full fruition.

3 All the recently published early chamber works have been recorded by the Nash Ensemble, on Hyperion CDA67381/2, released in 2002. Another early work relevant to this chapter is the Fantasia for Piano and Orchestra, on which Vaughan Williams laboured intermittently between 1896 and 1904, after which it appears to have been set aside; though completed, it was never performed.

4 This is derived, ultimately, from Samuel Sebastian Wesley and other nineteenth-century ecclesiastical composers: see , ‘Parry and Elgar: A New Perspective’, MT 125 (1984), 639–43.

5 KW, 83.

6 MT 50 (1909), 797.

7 and , ‘Vaughan Williams, Ralph’, in Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/42507 (accessed 30 May 2013).

8 , ‘Instrumental Music i’, in (ed.), The Blackwell History of Music in Britain: The Twentieth Century (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995), 245.

9 KW, 90.

10 , ‘Modern British Composers: Ralph Vaughan Williams’, MT 61 (1920), 232–4, 302–5, 371–4, at 373.

11 Cobbett established a chamber-music prize in 1905, originally for a Phantasy Quartet. As Grove explains, ‘There followed numerous other awards for such “phantasies”, a name Cobbett chose as a modern analogue of the Elizabethan viol fancies, in which a single movement includes a number of sections in different rhythms – or as Stanford defined the genre, a condensation of the three or four movements of a sonata into a single movement of moderate dimensions.’ Frank Howes and Christina Bashford, ‘Cobbett, , in Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/06006 (accessed 30 May 2013).

12 Programme note for the first performance reproduced in VWOM, 337.

13 Julian Onderdonk suggests Vaughan Williams ‘never rid himself of certain romanticized notions about traditional music’, for example (Julian Onderdonk, ‘Vaughan Williams’s Folksong Transcriptions’, in VWS, 138).

14 VWOM, 43–56.

15 An exception can be found in the second chapter of David Manning, ‘Harmony, Tonality and Structure in Vaughan Williams’s Music’ (PhD dissertation, Cardiff University, 2003).

16 The term was coined by Elisabeth Lutyens: see ‘Cowpat Music’, in The Oxford Dictionary of Music, Oxford Music Online, www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/opr/t237/e2526 (accessed 30 May 2013).

17 Manning, ‘Harmony, Tonality and Structure in Vaughan Williams’s Music’, 79.

18 Ottaway and Frogley, Grove Music Online.

19 This new role is briefly pre-echoed at two to three bars after rehearsal letter C.

20 The other is from three bars after rehearsal letter V.

21 Bartók’s two Violin Sonatas were also written for her, in 1921 and 1922.

22 , Ralph Vaughan Williams: A Study (London: Harrap, 1950), 170.

23 , Vaughan Williams (London: Faber and Faber, 1963), 412.

24 Ottaway and Frogley, Grove Music Online; KW, 216.

25 Flos Campi is discussed in detail in Chapter 2, 48–9.

26 , Essays in Musical Analysis, vol. ii (London: Oxford University Press, 1935), 208.

27 The acoustic mode is the major scale with sharpened fourth and flattened seventh.

28 Duncan Hinnells, ‘Vaughan Williams’s Piano Concerto: The First Seventy Years’, in VWIP, 132–4.

29 The track listing on some of the commercially available recordings lists four movements, regarding the ‘alla Tedesca’ part of the third movement, Fuga chromatica con Finale alla Tedesca, as separate. The published score (out of print at the date of writing) is clear that there are three movements.

30 VWOM, 352.

31 Ottaway and Frogley, Grove Music Online.

32 Kennedy writes that ‘A discarded scherzo of the [Fifth] symphony was turned into part of an Oboe Concerto for Léon Goossens’ (KW, 285), and presumably he is referring to the final movement. The prominence of fourths (see, for example, the four bars before rehearsal letter A) is reminiscent of the published Scherzo of Symphony No. 5.

33 KW, 347; Dickinson, Vaughan Williams, 422.

34 Jeffrey Richards, ‘Vaughan Williams and British Wartime Cinema’, in VWS, 151.

35 Evans, ‘Instrumental Music i’, 245.

36 Dickinson, Vaughan Williams, 474.

37 Richards, ‘Vaughan Williams and British Wartime Cinema’, 150.

38 Evans, ‘Instrumental Music i’, 187. I do not agree, however, with his assessment of Symphony No. 9, in particular, which seems to me rather harsh.

39 Ibid., 245–6.

40 KW, 362.

41 VWOM, 379.