Incorporating multiple methodologies in a single research design has the potential to significantly advance knowledge. The combination of “qualitative” and “quantitative” methods in political science has become more diverse, including case studies, statistical analysis, formal models, Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA), and experiments. In this study, we investigated specific ways in which scholars of welfare states combined research methodologies. We found that few published works incorporate mixed methods. We argue that this is a missed opportunity by analyzing the specific ways in which combining multiple methods can advance our understanding of welfare states. In doing so, this article contributes to the discussion of the actual use of mixed methods in the social sciences and the specific contributions that this can produce for the advancement of theory.

We chose to study the scholarship on welfare states because of its breadth across subfields and disciplines, which makes it prone to the use of multiple methodologies. On one hand, it crosses a number of subfields in political science, including political economy, comparative politics, international relations, and American politics. On the other hand, the scholarship on welfare states extends beyond political science, incorporating sociology, economics, and public policy. In these ways, the findings in this article regarding the benefits of mixed methods for theory development and testing incorporate research in political science and the social sciences more broadly.

DATA COLLECTION

To analyze the frequency and types of the use of mixed-methods research, we conducted a meta-analysis of the welfare states literature. We defined welfare states scholarship as works that cite Esping-Andersen’s seminal 1990 book, Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Footnote 1 which is a foundational piece for the study of welfare regimes. Before its publication, most studies were limited to “levels” of spending; after this publication, scholars of the welfare state incorporated the notion of qualitatively different “types” of regimes (i.e., social democratic, conservative, and liberal). Those interested in the characteristics, causes, and consequences of types of regimes across countries and regions after 1990 cite Esping-Andersen’s agenda-setting book. In fact, in the introduction to the special issue for the 25th anniversary of The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Emmenegger et al. (2015, 4) argued that the book is a classic in that:

[I]t has (1) advanced the methods of the discipline to produce new insights, (2) incorporated previous understandings of the topic by synthesis or antithesis, (3) has become a standard reference of the discipline for people outside the discipline, (4) has influenced the broader debate on the topic, (5) influenced research outside the core discipline and…(6) [its] impact is cross-cultural and timeless.... Today, Three Worlds is a standard reference in virtually all social science disciplines.

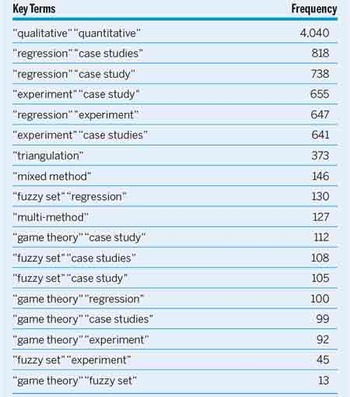

To select articles and books about the welfare state that incorporate mixed methods, we first conducted a search on Google Scholar for Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) citations. In total, there were 25,843 citations. Following the general search, we filtered these citations to isolate those that potentially utilize mixed methods. To do this, we searched the entire text looking for methodological concepts (e.g., “qualitative,” “quantitative,” “regression,” and “case studies”). These words did not necessarily appear in the key terms, but Google Scholar searches through the entire text of a book or article. Table 1 lists these concepts and the frequency of results that accompanied them. Finally, we complemented the online search with a physical library search of books that are shelved alongside Esping-Andersen’s at the University of New Mexico’s Zimmerman Library, that cite his book, and that use mixed methods. This was done to address a possible bias of the online search toward newer works. Footnote 2

Table 1 Terms Used in Google Scholar for Studies That Cite Esping-Andersen (1990)

Note: Both terms (e.g., “qualitative” and “quantitative”) must appear in the text to be included in the frequency.

After completing these steps, we had fewer than 9,000 possible entries. We analyzed each entry to see whether it actually used multiple methods in the text rather than including these words in a different context. Footnote 3 In general, identifying and coding a method was obvious and not problematic. Footnote 4 For example, studies using regression analysis featured regression tables. On the contrary, identifying case studies proved to be less straightforward. Case studies were used for varying purposes—as contextual information, to identify causal mechanisms, or to build a theory—and in varying detail. We included all types in our analysis. After selecting the works that actually incorporated multiple methodologies, we compiled 78 unique entries. Footnote 5 Of these works analyzed, 58% were books and 42% were academic journal articles. Footnote 6 In terms of discipline, 64% had unique or first authors (listed) associated with political science departments, 15% with sociology, 9% with economics, 3% with social policy, and the remainder with other fields. Footnote 7

FINDINGS

The proportion of studies of welfare states that incorporate mixed methods is small: less than 1% of all published works from the early 1990s to 2016. Footnote 8 Until 2000, we found only six works using multiple methodologies; this increased from 15 works from 2001 to 2005, to 19 from 2006 to 2010, and then to 38 from 2011 to 2016. Footnote 9 In terms of which methods are mixed, figure 1 illustrates that 66% combine regression or statistical analysis and case studies, 11% combine formal models and statistical analysis, 7% combine QCA and statistical analysis, 6% combine case studies and formal models, 5% combine QCA and case studies, and 5% incorporate experiments with other methodological strategies. We selected strong examples of the three main combinations and assessed how the choice of mixed methods advances theories of welfare states in ways that single-method research designs cannot achieve.

The proportion of studies of welfare states that incorporate mixed methods is small: less than 1% of all published works from the early 1990s to 2016.

Figure 1 Percentage of Studies by Type of Research Method

Two thirds of the studies surveyed combined statistical analysis of a large number of observations with case studies of a small number of cases. We found in our sample two main alternatives when presenting results of these two methodologies in a single research design. Some studies began with the case study to generate a causal hypothesis and then examined whether those conditions can be generalized to a larger set of cases in the regression analysis. Conversely, other studies began with the regression analysis to establish association between variables and then moved to case studies to establish causality. Footnote 10 The latter is the traditional “nested” design in which case studies presented after the statistical analysis corroborate the findings of the quantitative analysis, improve the measurement of the variables, and—most important—assess the causal mechanisms that lead to such results (George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005; Lieberman Reference Lieberman2005; Ragin Reference Ragin1989).

Huber and Stephens (Reference Huber and Stephens2001) provided an excellent example of the benefits of the nested research design for the advancement of theory. The authors studied the role of the power resources of political parties, labor unions, and women’s movements for the expansion of the welfare state in advanced industrial countries. To test their theory, they combined a pooled time-series analysis of all countries in their sample with detailed studies of nine selected cases. The incorporation of both methodological strategies advances the understanding of the role of long-term processes in the development of welfare states. In other words, their book analyzed how the actions of actors (e.g., the decision of Swedish conservative politicians and organized employers to support harvest-time reforms) are shaped by long-term structural factors (e.g., the long tenure of the Social Democratic Party). The Swedish Conservative Party’s support of the reform in isolation would have generated the conclusion that Left partisanship does not matter for social-policy reform. To contest this short-term argument, the authors increased the temporal domain in their case studies and also highlighted the strong statistical association between partisanship and levels of welfare-state outcomes.

The statistical analysis also allowed Huber and Stephens (2001, 35) to assess counterfactuals in specific cases: “[if] we assert the Norwegian welfare state would have been different in 1980 had bourgeois coalitions been predominant up to that point, we can point out that if Norway’s welfare state were the same in the case of bourgeoisie predominance, it would have been an extreme statistical outlier in our data analysis.” Overall, the combination of both methodologies in a single research design allows for making a stronger case for the role of structural factors—as opposed to theories based on agency—on social-policy reform. Analyzing long-term causes of welfare-state development is a crucial contribution of their book.

The second most common strategy that we identified mixes formal models with statistical analysis. A number of studies on inequality and redistribution employ formal models to specify the theory before testing it using a regression analysis. Mares (Reference Mares2005) represented a noticeable example of this strategy by first using a formal model to develop predictions about social-policy preferences and their variation across sectors with different risk and then testing these propositions using a dataset of social-policy coverage across countries.

The combination of these two research strategies allowed the author to advance the theoretical discussion by qualifying the previously established positive relationship between economic openness and social protection. As Mares (2005, 624–5) explained, the finding that economic openness expands the welfare state was criticized on the grounds that the causal mechanisms are not clear. The author argued that the level of volatility in the economy that produces economic insecurity in certain sectors favors social policies that compensate workers in moments of economic downturn. Conversely, workers in sectors that face lower volatility oppose redistributive social policies, fearing that they could become subsidizers of high-risk industries. The resolution of this political conflict between high- and low-risk coalitions is shaped by the balance of power between the two sectors and the capacity of the state to enforce existing policies. As a result of the latter resolution, trade openness may not expand the welfare state in less-developed countries with weaker states. Mares tested this theoretical model using an original dataset that included 129 countries and measures of the generosity of social-insurance coverage, trade openness, variability in the terms of trade (i.e., external risk), and state efficiency, among other variables. Overall, incorporating a formal model before the large-N analysis allowed the author to clearly specify causal mechanisms and establish the conditions under which economic openness expands (or retrenches) the welfare state.

By combining methodological strategies, Hicks (1999, 32–3) brought together two separate perspectives on the welfare state: one—mostly qualitative—highlights the emergence and changes of the main social-security programs; the other—mostly quantitative—focuses on changes in spending and benefits in programs.

Finally, the third most common strategy combines QCA and statistical analysis in a single research design. This methodological strategy has been increasingly implemented since the late 1990s, more specifically since Ragin’s (1989) publication of his path-breaking book on the use Boolean algebra to determine all possible combinations of an outcome. Hicks (Reference Hicks1999) provided the first analysis of the welfare state to incorporate these two methodologies. He showed that working-class mobilization explains differences across income-security policies in affluent democracies. By combining methodological strategies, Hicks (1999, 32–3) brought together two separate perspectives on the welfare state: one—mostly qualitative—highlights the emergence and changes of the main social-security programs; the other—mostly quantitative—focuses on changes in spending and benefits in programs. In this research design, QCA accounts for different routes (or equifinality) to early welfare consolidation since 1880 and statistical analysis for analyzing yearly changes since the 1960s. Whereas the first strategy aids the generation of new theories, the second is intended for testing already-existent hypotheses.

CONCLUSIONS

A survey of the literature on welfare states illustrated that there are still few published works that mix methodologies in a single research design. We argue that this is a missed opportunity because incorporating multiple research strategies has advanced theories of welfare states. In particular, by combining more than one methodology, Hicks (Reference Hicks1999) explained the causes of the emergence of welfare states as well as yearly changes of benefits, Huber and Stephens (Reference Huber and Stephens2001) contributed to the analysis of long-term causes of welfare-state development, and Mares (Reference Mares2005) qualified previously held theories about the positive effect of economic openness on social protection. These exemplary works advanced our theories in part as a result of research designs that combine QCA and statistical analysis, pooled time-series analysis and case studies, and formal models and regression analysis, respectively.

Another mixed-methods strategy to advance theories of welfare states not discussed in this article involves “scaling down” the unit of analysis from the national to the subnational level. The Subnational Comparative Method has two benefits: it enhances the probability of valid causal inferences by increasing the number of observations, and it constructs controlled comparisons (Snyder Reference Snyder2001, 94–7). For these reasons, recent studies on social policies have chosen subnational research designs that combine different methodologies (Borges Sugiyama Reference Borges Sugiyama2013; Niedzwiecki Reference Niedzwiecki2016; Reference Niedzwiecki2017; Singh Reference Singh2015).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096517001226.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For comments on a previous draft, we thank John Stephens, two anonymous reviewers, and participants at the Second Southwest Mixed-Methods Research Workshop, particularly Marissa Brookes, Jennifer Cyr, Tobias Hofmann, Kendra Koivu, and Paulette Kurzer.