Introduction

Singapore is a multi-ethnic society of 3.8 million residents comprised of 75 per cent of people from Chinese background, 13 per cent from Malay background, 9 per cent from Indian background and 3 per cent from other groups (Singapore Department of Statistics 2012). Based on current population trends, Singapore will be the second fastest ageing population in the world, behind Japan. The number of older Singaporeans aged 65 years and above will rise from one in 12 in 2009 to one in five in 2030. There will be an increase in the average current life expectancy to 82 years and 86 years for men and women, respectively (Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports 2009). In a non-welfare system (Chan Reference Chan, Fu and Hughes2009), the family remains the first line of support (Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports 2009) and the need to work in later life, a common practice of the lower socio-economic group (Hermalin and Chan Reference Hermalin and Chan2000; Mehta Reference Mehta1999a), is also strongly encouraged by the recent ‘successful ageing’ policy to ensure financial security in later life (Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports 2009). In recent times, a sub-group of older professional taxi drivers presented new challenges to policy makers by lobbying for the extension of their working lives beyond 70 years of age. At the same time, policy makers were concerned to balance public safety with competent driving performance from older taxi drivers (Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle Reference Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle2010a).

Driving performance is known to be affected by age and health-related changes. It is common that professional drivers comply with higher licensing standards than ordinary drivers, in view of their longer driving hours and work-related demands despite regional differences in licensing policies (Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle Reference Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle2010b). Yet the landscape of retirement specific to older professional drivers and its influences on the workforce are not yet fully understood internationally. Until 2006, age-based mandatory retirement at 70 years existed for all types of professional drivers (Class 3 taxi and minibus, Class 4 and 5 heavy vehicles) in Singapore (Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle Reference Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle2010a; Singapore Medical Association 2011). Distinctively, only Singaporeans are eligible to become taxi drivers (Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle Reference Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle2010b) without a quota restriction, unlike the other groups of professional drivers allowed additional access to imported labour for their workforce. During the election year of 2006, older Singaporean taxi drivers lobbied for changes to the mandatory retirement age.

In a rapidly ageing society, there is a risk of the retirement of older workers reducing the supply of a skilled workforce (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) 2006). Policy makers worldwide have been encouraged to promote older workers participation (Ebbinghaus Reference Ebbinghaus2006; OECD 2006), especially in Western countries known previously to have an early retirement trend and a leisure-ethic lifestyle in later life (Neugarten Reference Neugarten and Neugarten1996). Subsequently, there have been regional reviews of policies which have included the prevention of forced early retirement prior to 65 years, for example in Europe and Singapore (Goh Reference Goh2009; Ministry of Manpower, Singapore 2013), and the removal of mandatory retirement policy in the United States of America (USA) (von Wachter Reference von Wachter2012). Despite no shortage of labour supply to the Singaporean taxi driver workforce due to the newer surge of younger citizens into the industry (Tan Reference Tan2013), the taxi licensing policy in Singapore was revised in 2006 following lobbying by older taxi drivers (Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle Reference Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle2010a).

Optional taxi licence renewal at the age of 70 years until 73 years was allowed provided that drivers passed both the medical screening and a new functional driving assessment (Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle Reference Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle2010a, Reference Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle2010b). A unique feature of the licensing policy is that the older taxi drivers would retain valid ordinary driving licences upon expiry of their professional licences. However, Singapore has a transport policy that limits private car ownership uniquely through an additional high financial costing required for a certification to own a vehicle. The impact is that most retired taxi drivers are unlikely to own personal vehicles. Retired taxi drivers are likely to experience driving cessation as a result of the mandatory retirement. Retirement for older Singaporean taxi drivers therefore represents a complex experience of expected but forced age-based retirement from both work and driving, unrelated to driving performance, health or safety issues.

Literature review: retirement from work and driving

Retirement from work is a multi-dimensional process involving the complex interaction of personal, institutional and societal contexts, characterised by common trends and diverse individual outcomes (Beehr and Bennett Reference Beehr, Bennett and Shultz2007). From a lifecourse perspective, retirement transition from work has been reported to involve psychological adjustment and the practical development of a new lifestyle (van Solinge and Henkens Reference van Solinge and Henkens2008). Research indicates there is a sub-group of people at risk of poor outcomes from retirement in terms of life satisfaction (Neugarten Reference Neugarten and Neugarten1996; Pinquart and Schindler Reference Pinquart and Schindler2007; van Solinge and Henkens Reference van Solinge and Henkens2008; Wang Reference Wang2007). These include older workers with low incomes and low educational level; workers with a strong work role identity experiencing involuntary retirement due to ill health or job termination; and those with compromised personal, social and psychological resources (Neugarten Reference Neugarten and Neugarten1996).

Existing driving cessation literature has highlighted negative consequences for health, with increased depression, and reduced quality of life and community participation when older ordinary drivers in the West retire from driving (Liddle, McKenna and Bartlett Reference Liddle, McKenna and Bartlett2007; Marottoli et al. Reference Marottoli, Mendes de Leon, Glass, Williams, Cooney and Berkman2000), often due to health changes or decreased driving abilities (Anstey et al. Reference Anstey, Windsor, Luszcz and Andrews2006; Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Ross, Ackerman, Small, Ball, Bradley and Dodson2008). The process of driving cessation could be gradual, voluntary, or sudden and involuntary, with consensus in the literature describing it as a life transition leading to psycho-social and transport needs for older ordinary drivers (Choi, Adams and Kahana Reference Choi, Adams and Kahana2012; Eisenhandler Reference Eisenhandler1990; Liddle et al. Reference Liddle, Turpin, Carlson and McKenna2008; Siren and Hakamies-Blomqvist Reference Siren and Hakamies-Blomqvist2009; Whitehead, Howie and Lovell Reference Whitehead, Howie and Lovell2006; Windsor and Anstey Reference Windsor and Anstey2006). An expected, voluntary retirement context could allow for easier psychological adjustment and better outcomes than a sudden, involuntary event (Liddle et al. Reference Liddle, Turpin, Carlson and McKenna2008; van Solinge and Henkens Reference van Solinge and Henkens2008). In contrast to Western studies, research on driving cessation in Asia remains unexplored even though there is recognition of the influences of local context, cultural values, ethnicity, gender and personal life histories impacting on driving cessation experiences and outcomes (Choi, Adams and Kahana Reference Choi, Adams and Kahana2012; Curro Reference Curro2010). To date, literature on professional drivers with a focus on retirement and driving cessation are lacking compared to those on health and safety issues, highlighting certain medical conditions and fatigue levels.

Singaporean context

Local retirement studies have described Singaporean workers as having a strong worker role identity and being concerned about finding alternative employment on retirement. Strong cultural value on the importance of work from influences of Confucian work-ethic, financial need, a cultural focus on a male worker identity and undeveloped leisure lifestyle (Lim Reference Lim2003; Lim and Feldman Reference Lim and Feldman2003; Mehta Reference Mehta1999a; Thang Reference Thang2005) could contribute to a challenging retirement transition for some Singaporeans. In a non-welfare society, Singaporean older workers without institutional pensions, for example self-employed or casual workers, and who are without adequate traditional family financial supports (Chan Reference Chan, Fu and Hughes2009; Devasahayam Reference Devasahayam2004; Mehta Reference Mehta1999a) would be a potentially vulnerable group of retirees. Postponing plans for full retirement is likely for some Singaporean workers (Lim and Feldman Reference Lim and Feldman2003) and retirement planning is a new cultural challenge for older Singaporeans who are living longer (Thang Reference Thang2005) with an identified need for local retirement planning programmes, covering both financial and psycho-social aspects (Lim and Feldman Reference Lim and Feldman2003; Mehta Reference Mehta1999a). As self-employed workers, Singaporean taxi drivers do not have the benefit of an institutionalised pension scheme from taxi driving compared to other workers in government sectors or multinational companies.

Since 2007, there has been a national agenda to promote its vision of successful ageing through four main approaches: employability and financial security; holistic and acceptable health care and services; ageing in place; and active ageing (Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports 2009). Yet, a sub-group of older Chinese Singaporeans is at risk of poor ageing outcomes, for example older men and those with six or lower years of education (Ng et al. Reference Ng, Broekman, Niti, Gwee and Kua2009). With a focus on promoting successful ageing (Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports 2009), it will be useful for local policy makers to understand how retirement from taxi driving is experienced by older Singaporean taxi drivers, and if there are any related needs that could be addressed. Concerns related to postponing retirement at optional taxi licence renewal at 70 years of age could arise again at the extended mandatory age limit of 73 years. In June 2012 (after this study was conducted), the age limit was further raised from 73 to 75 years following feedback from taxi drivers (Land Transport Authority 2012). It is unknown whether older Singaporean taxi drivers could be a vulnerable group in terms of poorer ageing outcomes. The retirement context of older Singaporean taxi drivers provides a unique opportunity to explore the needs and experiences of mandatory and expected retirement for self-employed, professional drivers who are possibly in good health, within an South-East Asian context. Insights into the socio-cultural impact of later-life transition of older taxi drivers in the Singaporean context could be gained. The findings from the study could be potentially used to develop a relevant intervention for the target group in the future.

Design and methods

An exploratory research design (Teddlie and Tashakkori Reference Teddlie and Tashakkori2009) was indicated to answer the research question: What was the retirement experience of older taxi drivers? The descriptive phenomenological method (Langdridge Reference Langdridge2007) was chosen to obtain first-hand descriptive accounts from participants of varying backgrounds (years of taxi driving, ethnicity and retirement circumstances). Gathering information from in-depth interviews allows identification of the essences or structures of the similar but common lived experiences (Langdridge Reference Langdridge2007). Ethical approval for this study was granted by the National Healthcare Group, Singapore (DSRB 2009/00151) and the University of Queensland, Australia (2009001069).

Participants

In a descriptive phenomenological study, the emphasis is to seek a maximum variation of the phenomenon under study to give a deeper and fuller understanding of the common essential structure of the phenomenon. According to research literature, an unexpected event is associated with a more difficult transition compared to an expected event (van Solinge and Henkens Reference van Solinge and Henkens2008). The local scenario of licensing policy for taxi drivers (Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle Reference Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle2010a) informed the research team that there was a possible range of retirement experiences for older taxi drivers aged 70–73 years. When older taxi drivers fail their driving tests at 70 years of age, an unexpected event would likely have occurred. At 73 years of age, older taxi drivers would experience an expected, forced retirement. The retirement experiences of older taxi drivers could be planned or unprepared for, forced or voluntary, or any combination of these depending on multiple factors and contexts. It was, therefore, important to capture the breadth of the retirement experience (Langdridge Reference Langdridge2007) and across the continuum of the retirement transition from 70 to 73 years, to enable the potential development of a relevant intervention in the future to a wider population of retired older taxi drivers. Therefore, the study aimed to recruit up to 30 older taxi driver participants using purposive stratified sampling (Patton Reference Patton2002) based on their retirement experiences, characterised by three main groups (A, B and C) as described below.

Inclusion criteria

• Group A: Retired older taxi drivers, aged 73 years and above who did not renew their driving licences at 70 years, after failing their driving assessments. They were retired drivers who had experienced an unplanned retirement.

• Group B: Older taxi drivers, aged 72–73 years, who will retire within six months or have retired in the last six months. They were current and retired drivers soon approaching or had undergone expected but forced retirement recently at 73 years of age, respectively.

• Group C: Older taxi drivers aged 70 years who passed the driving assessments in the last six months. They were likely current drivers with an expected, forced retirement only in three years time.

• All participants require the ability to communicate in English, Mandarin, Chinese dialects or Malay. All taxi drivers have a basic level of English as required for initial taxi licence application but older Chinese taxi drivers may prefer to communicate in Mandarin, the official Chinese language between different dialects.

Exclusion criteria

• Taxi drivers unable to communicate in English, Mandarin, Chinese dialects or Malay.

These sub-groups of taxi drivers were formed to yield a maximum variation in the retirement experiences for inductive analysis and not for hypothesis testing. Data collection across the sub-groups of taxi drivers would continue until adequate saturation of themes was found (Patton Reference Patton2002). All taxi drivers were likely to be male due to the demographic distribution of the workforce (Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle Reference Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle2010a).

Procedure

Recruitment

All potential participants (Group A, B and C) were recruited from two sources. Firstly, the major driving assessment site for licence renewal of 70-year-old taxi drivers was asked to identify potential and shortlisted candidates from its driving records of 2006 and 2009, willing to be contacted by the researcher (MLC) for the purpose of the research. Secondly, advertisement leaflets were also distributed at places frequented by taxi drivers and to persons with potential networks to taxi drivers. The researcher (MLC) contacted interested candidates to answer any queries during multiple phone calls or visits before and after providing Participation Information Sheets with consent forms. Participants were reassured in the Participant Information Sheet and consent form that their identities would be kept confidential in the study and that collected data would be de-identified during data analysis and in the reported findings. Moreover, participants were reassured they could opt out of the study at any time without any negative consequences.

Data collection

The main mode of data collection was face-to-face, in-depth interviews using an audiotape to record the interviews with flexibility for telephone interviews when requested. These interviews were between 20 minutes and one hour duration. An interview schedule (Table 1) with key questions, adapted from driving cessation research (Liddle et al. Reference Liddle, Turpin, Carlson and McKenna2008), was used to prompt the participants and to guide the interview process where necessary.

Table 1. Interview schedule

Interviews were conducted, after obtaining written consent, at a location and in the language (English or Mandarin) preferred by the participant. All English interviews were conducted by the researcher (MLC). A local volunteer interpreter assisted the researcher (MLC) with the initial five Mandarin interviews and transcribed one Mandarin interview into English. All English interviews and remaining Mandarin interviews were transcribed verbatim by the researcher (MLC). Member checking (Patton Reference Patton2002) was done with the summary of the transcribed interview during a second visit to the taxi driver a week later or on the telephone, where appropriate. Additional data from impressions and observations made during the interviews were also recorded in the post-interview memo notes and field notes to enable triangulation of the data (Patton Reference Patton2002).

Data analysis

The data were analysed and interpreted inductively. Phenomenological reduction guidelines (Langdridge Reference Langdridge2007) were used by the researcher (MLC) to analyse the taxi driver transcripts to arrive at a tentative list of themes for coding. Two other researchers in the team (LG and JL) conducted independent paper coding on Group A and Group B drivers to act as expert reviewers and to ensure reliability of the data through inter-coder agreement (Patton Reference Patton2002). Following consensus coding (Patton Reference Patton2002) between all three researchers, five key themes were identified. This coding tree was further refined to four main themes between two researchers (MLC and JL) in the recoding of six selected transcripts (two from each Group A, B and C participants) that reflected the diversity and complexity of issues. The nVivo (version 8) software (Qualitative Solutions and Research 2009) was used to manage the coding tree. This paper will report three of the four major themes that emerged. The remaining theme, ‘Needs in retirement’ will be reported elsewhere.

Results

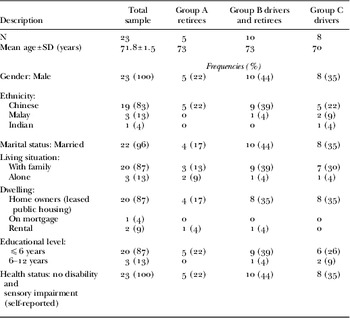

All participants (N=23) were recruited from the major driving assessment site for older taxi drivers. They comprised five Group A, ten Group B and eight Group C male participants. There were participants who were two months to three years before retirement (N=8) and those who had retired (N=15) for lengths of time ranging from a week to three years. The socio-demographic information of the participants is summarised in Table 2. Most interviews were conducted in Mandarin (N=15) and the rest were in English (N=8). Contrary to the potential for differences in outcomes and needs, based on the nature of retirement experiences, the results of the inductive data analysis indicated strong commonalities in the outcomes and retirement experiences between sub-groups of participants. The majority of retired participants, whether they had failed (Group A) or passed the driving tests (Group B) at 70 years, reported a difficult retirement transition with unmet needs. Three of the four major themes capturing the needs and experiences relating to retirement from taxi driving in Singapore are reported below.

Table 2. Socio-demographic status of participants

Note: SD: standard deviation.

Theme 1: The stories of taxi driving

This theme captured the recounted history of the taxi industry, the diverse meanings of taxi driving and experiences of the formal relicensing policy at 70 years old. Taxi driving was described with a sense of pride and fondness. Many questioned the mandatory age limit, but seemed resigned to the licensing policy. Descriptions of the taxi industry and their comments about the formal relicensing process were given spontaneously by a majority of the participants when they were asked about the meaning of taxi driving.

Descriptions of the taxi industry

Participants described how taxi driving had become more regulated and structured over time with the introduction of age-based mandatory retirement in the 1970s and the loss of personal ownership of taxi vehicles. All participants described increasing challenges in the industry in terms of lower earnings, more competition with the rise in taxi drivers and from younger drivers, besides a higher accountability in the industry.

Survival or freedom: diverse meanings of taxi driving

Participants attributed different meanings to taxi driving. Taxi driving provided for basic needs in terms of a home and food (i.e. survival) to extra spending money and easy transportation (i.e. freedom). There were also pragmatic, personal and identity-related significances of the role. The most common meaning attributed to taxi driving was related to income for 18 of the 23 participants. It was perceived as an occupation which offered good wages relative to educational and skill levels. Participants described with pride their achievement of home ownership of their leased public housing units and raising a family from their income, which had required relatively long working hours of up to 12 hours a day.

Income and the depletion of savings in retirement was a common concern when participants were over 70 years old. Half of the participants (N=12, 52%) spoke of how they struggled, or would struggle, financially without taxi driving to meet basic necessities, for example, daily expenses, medical bills and support for family dependents. As Participant 15 described, ‘Everything is outgoing expenses with nothing coming in. It is like a battery running flat without being recharged’ (retired driver, translated from Mandarin). The remaining half of participants saw taxi driving as an important means to earn extra spending money for leisure trips or meals out.

After income, the next most important meaning of taxi driving was the opportunity to pass time and be out of the home in the community in a purposeful role. This was perceived as more productive and important than staying at home and participating in household chores. One driver, Participant 20, stated it was ‘healthy to get out of the house … to do something compared to doing nothing at home’. Time away from home was also perceived as cognitively stimulating as it facilitated awareness of the outside world and to prevent cognitive decline and mental health problems.

Taxi driving was described as providing an optimal way to fill their days in a flexible and purposeful manner. ‘It gave me an easier way to pass and organise my time’ (Participant 4, translated from Mandarin). Drivers could organise their own time within the working shift to meet their personal needs and to match their endurance or fatigue with appropriate rest intervals. At the same time, they felt unrestricted in their encounters with people and places in the community, ‘…we can go anywhere we like, see places, the people and their characters’ (driver, Participant 20). These experiences were described as enhancing their sense of personal control and freedom, as part of being ‘your own boss…’ (retired driver, Participant 14, translated from Mandarin).

Participants also saw taxi driving as an opportunity for social interaction, indicating an increasing sense of enjoyment with time spent in the taxi industry. It was perceived as ‘full of fun’ (retired driver, Participant 11), from having stimulating conversation with all types of customers that also helped to give an understanding of different lifestyles. Driving provided participants with a recognised identity within the taxi community, allowing them to interact with peers informally at coffee shops, during their working day. ‘Same line, same industry … when you gather, you are already friends’ (retired driver, Participant 11).

For a few drivers (N=5, 22%), taxi driving provided cheaper access to a personal car to drive family members, buy groceries, meet medical appointments and for leisure trips. The loss of a personal car in retirement was associated with inconvenience and discomfort when they resumed taking public buses. Unfamiliarity with the newer public transportation, the Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) system, was also acknowledged by a few retirees (N=3).

‘No choice, licence stops’: experience of formal licensing process

Seventeen (74%) participants described their experiences of the relicensing process as leaving a sense of powerlessness. Whilst all participants supported the need for medical screening tests, opinions differed regarding the utility and fairness of driving assessments. They expressed frustration with the upper mandatory age limit of 73 years. The policy was perceived to be unfair as they were judged by age rather than abilities. ‘I am very upset with the government because I am healthy and not driving’ (retired driver, Participant 11). Participants expressed willingness to undergo annual medical and driving tests to continue working but appeared resigned and passive about the current system. About a quarter of participants (N=6, 26%) supported the mandatory retirement age, noting the risk of illnesses with age.

Although mandatory retirement was theoretically expected, the majority of participants were unprepared for it, reporting having no time to plan for it when busy at work. Current drivers seemed reluctant to actively plan for retirement, citing the unpredictability of the future. The minority who did report planning (N=5) tended to focus on financial preparation or finding alternative work, ‘Even before the government changed the policy for 70-year-old renewal, I was already thinking of how to get another job’ (retired driver, Participant 11).

Theme 2: Life after retirement – feeling lost

This theme covers the descriptions of the retired driver participants (N=15). The transition into retirement was characterised as mainly an emotional and practical adjustment to a life without the structure of a taxi driving day. ‘It was difficult, I felt like a boxer in a ring who experienced a knock out’ (retired driver, Participant 4, translated from Mandarin). Whilst the emotions during the initial post-retirement period became less heightened with time, a majority of the participants still felt lost without a worker role in late retirement. Boredom and the lack of a destination or purpose for out-of-home activities were highlighted.

Two-thirds of retired participants (N=10) described the acute retirement transition as the most difficult emotional time when dominant feelings of frustration, anger, sadness and loneliness prevailed. A retired driver, who stopped taxi driving five months ago, said ‘I feel upset. I feel sad … I am of no use’ (Participant 8, translated from Mandarin). However, this period appeared to start after a short holiday from working or in the initial few weeks post-retirement, characterised by having no immediate concerns and a reluctance to actively plan their retirement lifestyle.

The overall retirement transition period could last up to a year, according to those who had retired three years ago. It appears to involve the adaptation to a life in retirement without the structure and personal meaning of a taxi-driving lifestyle. One retired driver, who was mentally and financially prepared for retirement, described feeling lonely, ‘beaten [and] lost … as most of my activities are by myself’ and finding it difficult to ‘find things to do to fill in my time’ (Participant 4, translated from Mandarin). The descriptions of the daily routines of a taxi driver and a retired driver counterpart showed considerable differences between them. At work, a taxi driver experienced a variety of stimulation from different people and locations. After work, the taxi driver engaged with his family, rested or participated in indoor leisure activities such as watching television or reading newspapers.

In contrast, a retired driver could have less of a need and opportunity to travel out of home, and as widely as before without his professional role. Without any new roles or activities in retirement, a retired driver would only be involved in the same range of familiar, pre-retirement non-work-related roles, activities and social networks. These appear to involve mostly family roles, grocery shopping and socialising at neighbourhood coffee shops within walking distance, and did not last as long as previous working shifts. More than half of the retired drivers (N=9, 60%) had described their daily life as routine and boring, dominated by passive leisure activities and rest, without a destination or purpose to venture beyond their home vicinity. ‘I am so bored at home … there is nowhere to go. Every day you are at the coffee shops or watching television’ described a retired driver (Participant 15, translated from Mandarin). They appeared lost about how to structure or improve on their retired lifestyle without a worker role. ‘Everyday, I sit down, sleeping, eat, do nothing, a waste of my time…’ (retired driver, Participant 15, translated from Mandarin).

Finding alternative work was a common focus for two-thirds of the retired drivers. About half of the retirees (N=7, 47%) described their job searches as frustrating. Participant 8 highlighted, ‘Nobody wants us … other people get the jobs’ (retired driver, translated from Mandarin). Despite the lapse of three years, five out of six retired drivers were still hoping to find suitable employment, whilst not actively pursuing it. The few (N=3) who described taking up new home-based chores also expressed concerns about gender roles and spending too much time with their spouses. As explained by retired driver, Participant 11, it did not fit into his male gender identity, ‘Not like a housewife, you can do some housework, houseman, cannot…’ (retired driver, Participant 11). Another commented, ‘How much can you talk to your wife?’ (driver, Participant 21). Barriers to social roles in retirement were also described, arising from financial constraints, an undeveloped social network, and the lack of common interest and skills to make new friends.

Theme 3: ‘Old man, nobody wants’ – contradictions of growing old in Singapore

This theme emerged from the discussion about retirement and covered descriptions of beliefs, values and experiences of growing old in Singapore. Most participants appeared to have experienced a reduction in self-esteem in older age, particularly after retirement. They also placed a strong value on the importance of work, family, and staying healthy and independent. The majority felt unwanted, useless and vulnerable with the perceived loss of economic productivity. Participant 12 described a general sense of a loss of dignity and worth, ‘Being old is of no use. You lose out to everybody, everywhere’ (retired driver, translated from Mandarin). A majority felt vulnerable living in a non-welfare state with the rising cost of living and health care, even when living with their families.

Participants retold personal experiences and stories from friends and acquaintances portraying inadequate family support for older people in the community. Most (N=18, 78%) were anxious about becoming a burden to others. ‘When you are old, you cannot make money, you are burden, not only to self but to society’, described Participant 1 (retired driver). They were unsure about whether they could rely on traditional family support from children or relatives, for themselves or remaining dependants. Most were reluctant to burden their children financially, if they could avoid it, recognising the high cost of living in Singapore.

The majority of participants (N=18, 78%) identified staying healthy, functionally independent and active as priorities in later life. Becoming unwell and needing hospitalisation incurred high health-care costs and led to the depletion of financial resources. ‘Don't get sick … don't go to hospital … no good … no money to pay the bills, all the money gone’, recommended Participant 19, a driver. It also meant becoming a burden to their children or others. To remain healthy, all participants highlighted that it was important to maintain a sense of wellbeing. Some perceived work as necessary in old age and to maintain their health. ‘If you are healthy, you need some work or even a little bit of work to maintain your health … Being old like this [without work] is of no use’ (retired driver, Participant 8, translated from Mandarin).

Intergenerational concerns or difficulties between older and younger generations were highlighted by eight participants. There were descriptions of negative attitudes regarding their manner of behaviour or lower education level, wide communication barriers and lack of support from the younger generations, even for their decisions to continue working after 70 years of age. Participants described similar approaches in managing the intergenerational concerns within their family systems. All chose lifestyle options that avoided potential conflicts. These included separate living arrangements with married children, financial independence and seeking alternative sources of emotional support from distant relatives, friends or work peers. For Participant 20, his strategies were ‘… to talk less. Relationships will be better’ and to have minimal engagement in the traditional active grandparenting role, recognising different intergenerational styles of parenting.

There were varied views on the usefulness of current public policies for older people. The majority of participants (N=16, 70%) expressed a sense of vulnerability related to living in a non-welfare system. Most felt that the existing policies did not cater to the locally unemployed or older people who did not have family or financial support. According to an unemployed retired driver, ‘If I am not working, I am not entitled to any of the government payouts of $100 to $200 to supplement the income’ (Participant 8, translated from Mandarin). In contrast, two participants expressed positive views on the public policies. They described Singapore as a safe place to live.

Most of the participants appeared not to have taken steps to provide feedback to the government about their feelings of vulnerability. Two participants, who did engage with government authorities, reported no positive outcomes or resolution of their personal concerns. Three participants stated that it was not worthwhile approaching their Members of Parliament. Given the structure of the non-welfare system, the lack of confidence in future traditional family support and perceived inability to gain the attention of policy makers, work was seen as an important external resource for older people. ‘Who is going to help us? … the government does not assist financially. If you don't work, you can't get any money’ (retired driver, Participant 8, translated from Mandarin).

Several participants acknowledged the reality of limited alternative job prospects in later life. They described employers’ negative attitudes towards older workers, competition of cheaper labour from migrant and younger workers, and reduced retraining opportunities as barriers to their employment. Given this context, there were strong recommendations for government and employers to become more involved in finding and supporting employment for older workers. Some practical suggestions were to raise the 73-year-old mandatory retirement age for taxi drivers, provide driver refresher courses and to modify existing jobs to suit older workers’ abilities.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the rich, lived experience of expected, mandatory retirement and driving cessation of a stratified sample of older Singaporean taxi drivers and the findings inductively gave insights into the socio-cultural impact of their late-life transitions in Singapore. Distinctively, this sample differed from previous retirement literature, with mandatory retirement occurring at a later age of 70 or 73 years rather than the traditional ages of 65 or 60 years (Lim and Feldman Reference Lim and Feldman2003; Mehta Reference Mehta1999a; Neugarten Reference Neugarten and Neugarten1996). In addition, participants were different from previous local retirement studies which had lesser homogeneity in terms of gender, employment and socio-demographic background. All participants were male, self-employed, professional drivers. A majority of them were from a Chinese background, married, living in public housing and had less than six years of education. In comparison to driving cessation literature on older ordinary drivers (Anstey et al. Reference Anstey, Windsor, Luszcz and Andrews2006; Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Ross, Ackerman, Small, Ball, Bradley and Dodson2008; Eisenhandler Reference Eisenhandler1990; Liddle et al. Reference Liddle, Turpin, Carlson and McKenna2008), the majority of the sample had generally good health and driving abilities, with no impairments or disabilities.

The retirement experience

Retiring from taxi driving was characterised by participants predominately as issues related to retirement from work rather than driving cessation. It echoed the complex dynamic multi-dimensional process highlighted by retirement literature with common patterns and individual variation (Beehr and Bennett Reference Beehr, Bennett and Shultz2007). Participants described financial and psycho-social concerns related to the loss of the worker role (Mehta Reference Mehta1999a; van Solinge and Henkens Reference van Solinge and Henkens2008) and the lack of planning (Mehta Reference Mehta1999a). Apart from paid work, participants felt lost in seeking alternative meaningful and purposeful activities in retirement, consistent with local literature highlighting the strong worker role identity, undeveloped leisure lifestyle and the new cultural challenge of retirement planning (Lim Reference Lim2003; Lim and Feldman Reference Lim and Feldman2003; Mehta Reference Mehta1999a; Thang Reference Thang2005). Most seemed focused on the worker role, even when basic financial needs were provided for, with many seeking alternative employment after retirement from taxi driving. This is in contrast to the retirement transition studied within previous Western contexts that had a more leisure-life ethic and previous trend towards early retirement (Neugarten Reference Neugarten and Neugarten1996; OECD 2006) whilst acknowledging a changing trend in recent times. An average increase of 6 per cent in workforce participation of older workers aged 55–64 years has been reported from 2000 (47.6%) to 2011 (54.4%) across Western countries, even during job crises (OECD 2013). The legislative prevention of forced early retirement before 65 years of age in Europe (Goh Reference Goh2009) and the removal of the mandatory retirement policy in the USA (von Wachter Reference von Wachter2012) could have been positive factors contributing towards a change in Western retirement trends. Despite the expected nature of mandatory retirement which could make for an easier psychological adjustment compared to an unexpected one (van Solinge and Henkens Reference van Solinge and Henkens2008), participants in this study described a difficult retirement transition.

In contrast to Western driving cessation literature (Choi, Adams and Kahana Reference Choi, Adams and Kahana2012; Eisenhandler Reference Eisenhandler1990; Liddle et al. Reference Liddle, Turpin, Carlson and McKenna2008; Siren and Hamakies-Blomqvist Reference Siren and Hakamies-Blomqvist2009), most retired participants did not report missing the act of driving itself or having issues with accessibility to transportation. As professional drivers, driving was primarily a work-related activity for participants and seemed not linked as crucially to a personal leisure lifestyle as in most developed Western countries which have a more car-dependent culture (Stav Reference Stav2008). In addition, the better health status of participants meant that they could, theoretically, access public transportation without physical limitations. Whilst the findings did not give a better understanding of driving cessation from an Asian perspective, it yielded some insights into the experience of stopping driving without health-related issues. Participants perceived the age-based mandatory licensing policy as unfair as it was not linked to driving performance issues. They felt frustrated with a reduced sense of perceived control about their situation. Although the driver identity, in terms of ordinary driving, remained intact for retired participants, the loss of the professional driving licence meant the loss of a valued productive role in late-life transition, which resulted in grief.

Changes in cultural roles and values associated with the ageing process were apparent. The participants’ financial need to work, whether for survival or extra spending income, was consistent with literature highlighting the potential financial vulnerability of the majority of older Singaporeans, particularly in terms of disposable income compared to home assets (Chan Reference Chan, Fu and Hughes2009; Devasahayam Reference Devasahayam2004; Mehta Reference Mehta1999a; Reisman Reference Reisman2009). However, unlike previous findings of participants’ confidence in financial support from children (Mehta Reference Mehta1999a), participants cited stories that questioned the continuity of this tradition. Furthermore, in the face of inadequate financial support, participants were reluctant to ask for any financial assistance, perceiving themselves as a potential burden to children or society. The desire for financial independence could be a trend for older Singaporean men with longer life expectancy, reflecting changing values over time. With rising cost of living and fewer supports from a smaller family (Chan Reference Chan, Fu and Hughes2009; Mehta Reference Mehta1999a; Reisman Reference Reisman2009), it was not surprising that participants, without self-reported disability and sensory impairment (Table 2), chose to work. This was consistent with their socio-cultural values of being a responsible family member by contributing financially through the economic productivity of work, as shaped by Confucian philosophy (Westwood and Lok Reference Westwood and Lok2003).

On another level, the findings could also reflect changing values with regards to traditional roles in retirement. At 70 years of age, participants would likely be grandparents. Traditional family roles as grandparents have been described as involving care-giving to grandchildren or performing home-based chores for their children (Mehta Reference Mehta1997b, Reference Mehta1999b; Verburgge and Chan Reference Verbrugge and Chan2008). However, in this study some participants perceived grandparenting as a potential source of intergenerational conflict and reduced active involvement in any grandparenting tasks. Intergenerational issues could be partly explained by different values acquired through the type of education systems of the participants (Chinese-based) and their children (English-based), similar to findings by Mehta (Reference Mehta1997a). In addition, some participants highlighted the incongruity of home-based chores for their male identities, consistent with qualitative findings from a previous local retirement study (Mehta Reference Mehta1999a). An emerging trend towards a decline in participation in traditional family roles seems probable. Yet, traditional reciprocal family roles provided a way of social integration into families (Mehta Reference Mehta1997b), the primary social units of Singaporeans (Chan Reference Chan, Fu and Hughes2009). It could be argued that the potential loss of traditional family roles for participants could result in a less positive retirement transition and ageing experience, if alternative roles were not found. This scenario appeared to be supported by the study findings.

According to the theme ‘feeling lost in retirement’, participants described an unsatisfying retirement experience with a limited range of activities, characterised by boredom and isolation. Retired lifestyles mainly involved socialising at neighbourhood coffee shops for most participants or doing some home-based chores for others. According to van Solinge and Henkens (Reference van Solinge and Henkens2008), the retirement transition involved tasks of psychological adjustment to various types of losses (roles, time use, social) and that of developing a new meaningful lifestyle. It would appear that participants had not adapted positively to these tasks in retirement transition. The distinct lack of a productive role or activity outside the home in the description of retired lifestyles was noteworthy, even though such role preferences have been reported by Singaporean men (Mehta Reference Mehta1999a). This is a matter of concern, with literature highlighting the risk of depression in other groups including late middle-aged Japanese men, with high worker role identity, who are without a productive role after retirement (Sugihara et al. Reference Sugihara, Sugisawa, Shibata and Harada2008). Volunteerism which is known to have protective effects on the psychological adjustment to role loss in terms of wellbeing in retirement in Western contexts (van Solinge and Henkens Reference van Solinge and Henkens2008) was not described by participants, consistent with previous findings of a low level of volunteerism in older Singaporeans who are less educated (Schwingel et al. Reference Schwingel, Niti, Tang and Ng2009). The lack of volunteerism in retired participants could also be due to financial constraints associated with lower income savings related to their limited education level. Cultural values, gender, educational level, socio-economic status, social support, mental wellbeing and fulfilment of altruistic and self-oriented motives, including opportunities for new learning, appear to influence participation in volunteerism in the Asian contexts (Cheung, Tang and Yan Reference Cheung, Tang and Yan2006; Dekker and Halman Reference Dekker and Halman2003; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Kang, Lee and Lee2007; Mjelde-Mossey and Chi Reference Mjelde-Mossey and Chi2005; Schwingel et al. Reference Schwingel, Niti, Tang and Ng2009; Wu, Tang and Yan Reference Wu, Tang and Yan2005).

Participants described the contradictory and negative experience of ageing despite positive findings of participants’ pride in their personal achievements (home owners of leased public housing units, raising their families), the availability of family support (living with families rather than alone) and public policies promoting successful ageing (Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports 2009). Participants overwhelmingly described later life as characterised by the feeling of uselessness, which could be explained by several factors. In Singapore, both family and productive activities are important considerations for successful ageing in Singapore (Ng et al. Reference Ng, Broekman, Niti, Gwee and Kua2009; Niti et al. Reference Niti, Yap, Kua, Tan and Ng2008). However, participants appeared to ascribe a lower value to traditional family roles like grandparenting compared to productive roles. The lack of engagement in valued productive roles may lead to increased risk of depression (Sugihara et al. Reference Sugihara, Sugisawa, Shibata and Harada2008). The lack of acceptance and engagement in unpaid productive roles and activities may reflect underlying cultural beliefs, including the beliefs of some participants that work was necessary for health, due to a cultural high work centrality (Westwood and Lok Reference Westwood and Lok2003). Exploration of alternative productive roles that have personal, cultural meaning and value may be necessary with this group to enable the benefits of ongoing participation in later life when the work role is not available (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Azen, Zemke, Jackson, Carlson, Mandel, Hay, Josephson, Cherry, Hessel, Palmer and Lipson1997; Jonsson, Josephsson and Kielhofner Reference Jonsson, Josephsson and Kielhofner2001).

The findings of this study indicated that taxi driving is a unique work role. It is sedentary, non-physically demanding work in a comfortable air-conditioned vehicle with flexible work routines in terms of shifts and rest intervals. As such, the nature of taxi driving offered positive job characteristics for older workers who have to balance work performance with fatigue levels and safety concerns (Loretto, Vickerstaff and White Reference Loretto, Vickerstaff, White, Loretto, Vickerstaff and White2007). After retirement, participants were likely eligible for semi-skilled or manual work, for example cleaners, coffee shop assistants or security officers. However, these jobs are more physically demanding than taxi driving and largely unsuitable for the endurance level of these older workers. This would have complicated the retirement transition of the participants who valued paid employment roles, but struggled to find ones comparable to taxi driving.

The experiences of participants also gave insights into expected, involuntary retirement. The majority of participants had expressed frustration at the age-based retirement policy. Findings illustrated an intense but difficult emotional phase reported by participants in the early stage of retirement transition. Consistent with literature reporting the tendency of men to neglect addressing psycho-social concerns in retirement planning (Lee Reference Lee2003), participants were generally unprepared for the emotional issues of grief and adjustment as part of the normal process of adaptation in retirement transition (van Solinge and Henkens Reference van Solinge and Henkens2008). The loss of perceived control associated with an involuntary event could contribute to a more challenging psychological adjustment in the task of retirement transition than a voluntary event (van Solinge and Henkens Reference van Solinge and Henkens2008). The nature of taxi driving provided direct access to a wide network of customers and peers for social interaction, whereas retirement seemed to cause an immediate reduction in social opportunities. The unrealistic expectation of finding alternative work in late-life retirement could also prolong the adjustment process unnecessarily. At the same time, men are known to be reluctant to seek help for their emotional needs (Addis and Mahalik Reference Addis and Mahalik2003; Fields and Cochran Reference Fields and Cochran2011), thus predisposing any vulnerable retirees to be at risk of depression (Blazer Reference Blazer2002).

An unexpected finding of the retirement experience was the reduction of a life-space in terms of the extent of mobility in the environment (Stalvey et al. Reference Stalvey, Owsley, Sloane and Ball1999). Although participants were healthy and reported no transportation issues, the retired lifestyle was mainly spent at neighbourhood coffee shops. Life-space is a multi-dimensional construct integrating physical, motivational, psychological and social factors on the real-world experience of mobility (Boyle et al. Reference Boyle, Buchman, Barnes, James and Bennett2010). Given the relatively good health status of participants, it appears that psycho-social more than physical factors contributed to a reduction in life-space in retirement, in terms of an undeveloped leisure lifestyle (Thang Reference Thang2005) in the wider community and the focus on the family as the primary social unit (Chan Reference Chan, Fu and Hughes2009). Nonetheless, it is a matter of concern that a reduction in life-space is reportedly associated with a greater risk of mortality and impaired cognitive health in older people living in the community (Boyle et al. Reference Boyle, Buchman, Barnes, James and Bennett2010; James et al. Reference James, Boyle, Buchman, Barnes and Bennett2011). With growing literature recognising the interplay of psycho-social aspects of mobility with health and wellbeing of older people (Siren and Hakamies-Blomqvist Reference Siren and Hakamies-Blomqvist2009; Ziegler and Schwanen Reference Ziegler and Schwanen2011), the combination of reduced social network and life-space for retired participants in this study could potentially also reduce their sense of wellbeing in late-life retirement.

Overall, the mandatory retirement of older taxi drivers was found to be a stressful late-life transition, contrary to literature on better outcomes with expected retirement event (van Solinge and Henkens Reference van Solinge and Henkens2008) and current active ageing public policy (Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports 2009). At the same time, the concerns raised by some participants on the fairness of the current age-based mandatory retirement taxi licensing policy is consistent with findings of a recent survey highlighting the current local taxi licensing policy, as contrary to evidence-based practice (Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle Reference Chan, Gustafsson and Liddle2010b). The perception of ageism with regards to the taxi licensing policy would need to be addressed by policy makers as it appears contrary to the active ageing public policy (Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports 2009). Given that professional drivers of minibuses (Class 3) in Singapore also lobbied to postpone their retirement at 70 to 73 years of age in 2011 (Land Transport Authority 2013), they could potentially be another at-risk group of professional drivers struggling with late-life retirement transition. However, it is unknown universally if other types of older professional drivers, for example heavy vehicles (Class 4 and 5) and older workers from other fields, encounter similar type of challenges in late-life mandatory retirement transition within their own societal contexts.

Implications

The findings of this study indicate that there is a need to support the stressful mandatory late-life retirement transition of older taxi drivers to promote more positive retirement outcomes. Interventions targeting the range of predisposing but modifiable financial and psycho-social factors, for example intergenerational conflicts, social support, productive roles and life-space, are indicated. There is scope to assist in realistic expectations of low employment in late-life retirement with the acceptance of full retirement, and facilitate new types of unpaid but meaningful and productive roles, for example volunteerism. Future research may explore the meaning of unpaid productive activities in the local context. Given the potential trend of disengagement from traditional family roles which were means of social integration for older Singaporeans, it would be important to promote social engagement and support in community networks beyond the immediate family. On a broader level, there is potential to explore the application of an evidence-based taxi licensing policy for older taxi drivers, without a mandatory age limit but one that is based on regular health and driving performance criteria; the retirement issues with professional driver of heavy vehicles and other occupational groups; taxi drivers in other regions; and older Singaporean women in later life in view of the trend of changing family roles.

Limitations

The description of the ‘successful ageing’ policy was based on available government literature. Findings of the retirement experience may not reflect older taxi drivers who did not participate in the study. The gender, age, educational and cultural difference between the researcher and participants, including fear of repercussions from the authorities, could have been potential barriers to recruitment, full disclosure by participants during interviews and accurate translation of Mandarin interviews. The findings were also limited to retrospective and prospective accounts of participants at one point in time during the retirement transition process. There is a need to explore the retirement experience in a prospective longitudinal study and for future cohorts that may include female older taxi drivers.

Conclusion

Retirement for older Singaporean taxi drivers was an involuntary, expected life transition that resulted in the loss of a paid, productive role and access to a private motor vehicle. The impact of this life transition appeared largely related to the loss of the worker role in terms of its impact on financial security, identity, life-space and meaningful activity participation. Work remained a strong focus during retirement transition. Assisting in late-life retirement transition with the multiple-related role losses from taxi driving was indicated.

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to express their gratitude to the participants and the interpreter who volunteered in the study. This work was funded by the National Medical Research Council and Tan Tock Seng Hospital in Singapore, for academic fees and basic living allowance, respectively. Funding bodies played no role in the design, execution, analysis and interpretation of data, and writing of the study. MLC was responsible for refining the design of the study, gaining ethical approval, participant recruitment, data collection, data analysis and manuscript preparation. LG and JL contributed to the conceptual development and design of the study, data analysis and critical appraisal of the written work.