State-owned enterprise (SOE) reform and management is one of the most debated topics among economists and scholars in the China field. Discussions range from external market competition to ownership structures and corporate governance.Footnote 1 Since the 1980s, power delegation reforms have taken several forms, including management responsibility systems, board-of-directors systems and the establishment of joint-stock companies. During the 1990s and early 2000s, corporate governance in Chinese SOEs generally converged towards international “best practices” based on a stylized Anglo–American model.Footnote 2 According to an influential study, China's economic rise and integration into the global economic order were based on emulating Western rules and regulatory systems.Footnote 3 However, this trend seems to have reversed since 2012, when Xi Jinping 习近平 took charge. We now observe a formalization of the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) role in SOE management as the Party advances what it calls a “modern state-owned enterprise system with Chinese characteristics.”Footnote 4 A new regime of “corporate governance with Chinese characteristics” is being consolidated, with vast consequences for corporate operations.Footnote 5 This raises important questions: what form of SOE corporate governance is emerging under Xi Jinping? How is the role of the CCP institutionalized into modern corporate governance structures? Which key measures and institutions have been developed to ensure Party dominance, and what does this tell us about the nature of the Chinese corporate world?

In the literature, the role of the Party organization is the least understood aspect of corporate governance in China. This gap in extant research not only creates challenges for private and foreign investors alike but also limits our understanding of how the Chinese economic system works.Footnote 6 As such, there is a need to understand the role of the Party in SOEs, including the Party organization's relations with existing corporate organs and the relationship between the Party's leadership of SOEs and modern corporate governance rules.Footnote 7 Extending previous work by Christopher McNally,Footnote 8 Yukyung Yeo,Footnote 9 Yihong ZhangFootnote 10 and Jiangyu Wang,Footnote 11 we argue that the informal political governance structure of SOEs (the Party organization) is becoming an institutionalized element of legal SOE governance (for example, through amendments of SOE Articles of Association, new laws and new Party regulations). In particular, new policy directives issued in 2015, 2017 and 2020 mark important changes in SOE governance not previously addressed in the literature.

The article contributes an updated comprehensive review (up to January 2020) of the most important CCP documents, national laws and regulations related to the role of the CCP in corporate governance. It provides examples of the application of new laws and regulations in SOEs, including revisions of enterprise Articles of Association in listed state-controlled enterprises and decision-making and appointment procedures in non-listed SOE holding groups. The article also examines the application of Chinese indigenous administrative corporate governance concepts such as “bidirectional entry, cross appointment” (shuangxiang jinru, jiaocha renzhi 双向进入, 交叉任职) and “three majors, one big” (sanzhong yida 三重一大). Furthermore, the article discusses the Party's control over the selection and appointment of SOE executives through the nomenklatura system. Each of these points is made theoretically, through the presentation of illustrative empirical evidence, and via a case study of the China Energy Conservation and Environmental Protection Group (CECEP). We document the institutionalization of Party leadership in a new hybrid model of corporate governance. In addition to official documents and secondary works, we draw on interviews with enterprise managers, academics and government officials.

We find that a unique, hybrid model of SOE governance is institutionalizing in the form of a legal governance structure, in accordance with Western (Anglo–American) standards, and co-existing with a political Party-led governance structure. Extensive vertical and horizontal managerial interlocks exist between the CCP organization within the enterprise and other corporate organs. It is part of Xi Jinping's broader agenda to re-establish Party control over all aspects of society and under which the Party is increasingly being morphed with the state.

We argue that the roots of this change lie in the Xi administration's search for a way to combine market-oriented institutions, law-based governance and continued reform with stronger Party leadership in all areas of society. The CCP is mixing market-oriented institutions with tight Party oversight. This has led to the standard corporate governance structure being mixed with strong Party groups (dangzu 党组) and Party committees (dangwei 党委) within enterprises. These bodies appoint senior management and take part in strategic decisions. Under the Xi administration, the principle of “separation of government and business” (zhengqi fenkai 政企分开) still applies, but clearly does not mean “separation of Party and business.” Indeed, Party-defined policy objectives are at the heart of SOE operations and management.

Literature Review

Overall, two types of literature on Chinese corporate governance have emerged. Studies in the first group take as their starting point international/Western best practice corporate governance models and, in particular, the Anglo–American model of corporate governance. They point to problems and troublesome practices in China while making recommendations to improve effectiveness, accountability, transparency and efficacy of corporate governance.Footnote 12 And, in general, they predict continued convergence towards the Western model of corporate governance.Footnote 13 These studies do not, however, take into account the key role of the Party in leadership appointments and decision-making procedures. In contrast, a second group of studies addresses governance from an institutional embeddedness perspective, acknowledging the Party organization as an important corporate governance organ.Footnote 14 Most of the studies in this group concentrate on listed state-controlled companies, which are subsidiaries of SOE holding groups.Footnote 15 However, the holding groups or parent companies themselves are beginning to come into focus.Footnote 16

Discussing local (Shanghai) regulations on overlaps between the Party committee and modern corporate organs, McNally argues that Chinese reforms have allowed for continued interference by Party institutions in the governance of corporatized SOEs, leading to ineffective corporate governance setups.Footnote 17 Wen Lin and Curtis Milhaupt focus on institutionalized mechanisms linking the SOE business groups with other organs of the party-state – for example, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission's (SASAC) behaviour as a controlling shareholder.Footnote 18 They describe “two parallel personnel systems in all Chinese SOEs: the regular corporate management system and the party system,” including a brief mention of the important principle of “bidirectional entry, cross appointment” (BECA).Footnote 19 In a similar vein, Wang finds that “SOEs in China are subject to a system of corporate governance that features two parallel structures, one for legal governance and the other for political governance.”Footnote 20 He analyses the content of the October 2004 CCP policy document that contains the first outline of the BECA principle, arguing that the two parallel structures run separately.Footnote 21 Wendy Leutert empirically analyses the BECA principle in 53 central SOE holding groups.Footnote 22 Angela Zhang and John Liu study the recent amendments of listed SOEs’ charters.Footnote 23

McNally, Wang, Leutert, and Zhang and Liu all point to the increasing importance of the Party organization in corporate governance. In contrast, Milhaupt and Zheng argue that the party-state exercises less control over the state sector than is commonly assumed – mainly owing to insider control and the control challenges inherent to large pyramid-shaped corporate organizations.Footnote 24 However, Kjeld Erik Brødsgaard and several chapters in Barry Naughton and Kellee Tsai's 2015 work maintain that the control mechanisms posed by organization departments of the Party (namely, the nomenklatura and Party committee appointments of managers) ensure control over the state sector.Footnote 25 Naughton and Tsai find that the Chinese system is fundamentally “Communist Party-managed state capitalism.”Footnote 26

Important insights have been gained from this group of studies regarding the Party's role in corporate governance. However, only Leutert along with Zhang and Liu address the period after Xi Jinping's assumption of power in 2012,Footnote 27 leaving a dearth of research on recent developments. During Xi's tenure, more than 70 per cent of all Party rules have been revised or reformulated, including important regulations on Party–SOE relations.Footnote 28 In particular, the main policy directives from 2015, 2017 and 2020 mark important changes in SOE governance not previously addressed in the literature.Footnote 29 For example, the 2020 document provides crucial information on the detailed work of Party committees, Party general branch committees, Party branches and Party groups.Footnote 30 The regulations intend to get the Party out of the shadows by increasing the institutionalization and formalization of the Party's role in corporate governance. As such, we argue that the two parallel structures, described by Wang as well as Lin and Milhaupt, are now merging into one hybrid model under Xi Jinping.Footnote 31

SOE Corporate Governance in China: Between Economic and Administrative Models

The concept of “corporate governance” (gongsi zhili 公司治理) was officially endorsed by the Party in 1999.Footnote 32 In the early 2000s, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) introduced an independent-director system and a policy of specialized board committees for all listed companies. The establishment of the SASAC in 2003 intended to secure uniform representation of the interests of the state in corporatized SOEs. With the 2005 Company Law revision and various SASAC-led initiatives, additional Anglo–American market-based mechanisms gradually strengthened SOE corporate governance and the monitoring of SOE managers. In 2004, the SASAC launched a pilot programme which selected seven central SOEs (central holding groups) to implement “standardized boards.” Board committees – including nomination, remuneration and evaluation, and audit committees – were established to act as advisory bodies to the board.Footnote 33 Also, the company's general manager would remain on the board but would no longer serve as its chairman, and managers involved in the day-to-day operations of the company were entirely excluded from serving on the board.Footnote 34 The introduction of a standardized board system with a majority of external directors has been considered the centrepiece of the SOE governance reforms.Footnote 35 By mid-2019, all 96 central SOE holding groups controlled by the central SASAC had implemented this system, while 90 per cent of the local SASAC groups had established boards of directors.Footnote 36

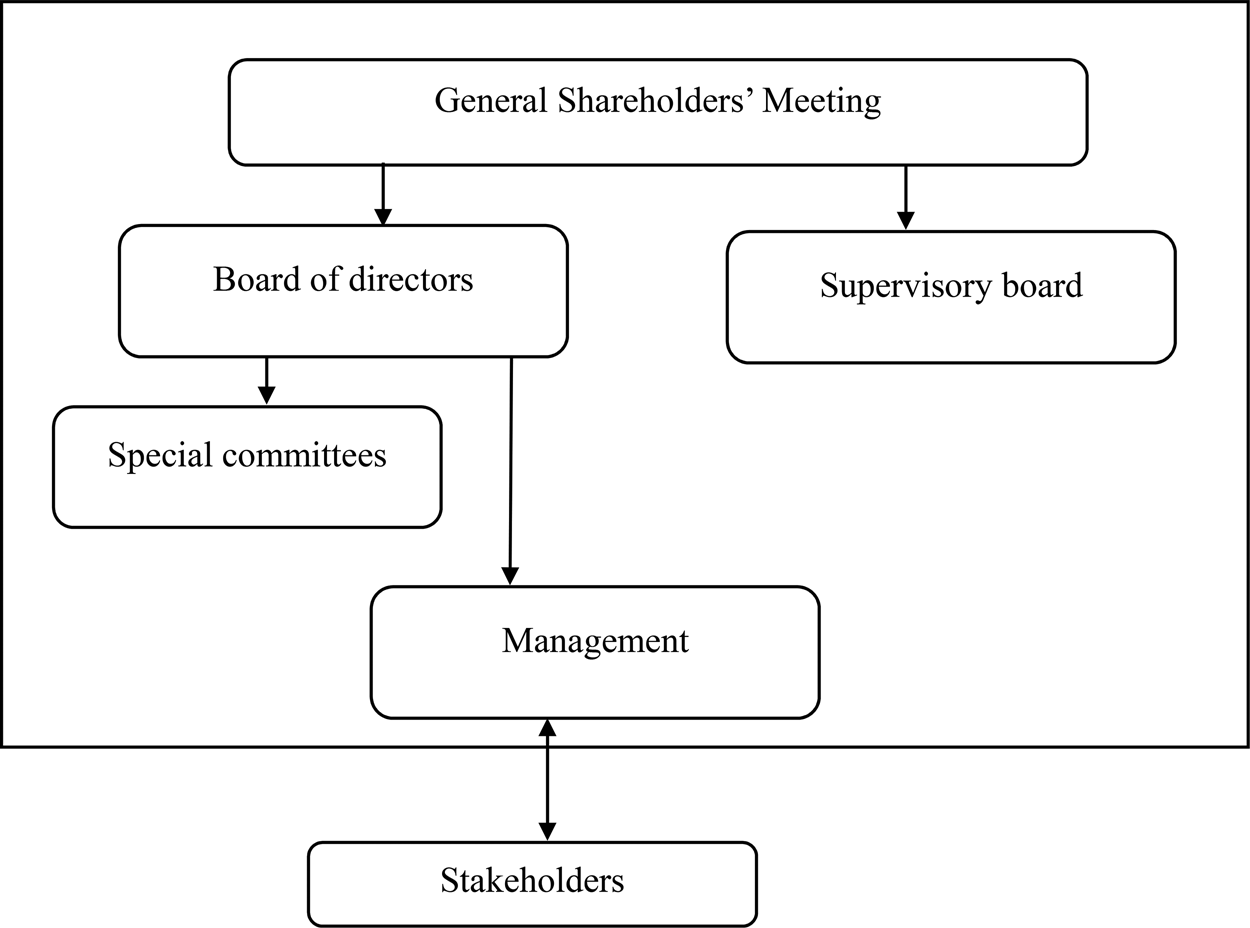

In short, Chinese SOEs have for the most part been corporatized into limited liability companies and stock-holding corporations that are subject to the Company Law in a manner similar to that which governs private and foreign companies operating in China.Footnote 37 Some SOEs are listed on stock exchanges in order to raise capital and to improve governance and transparency. During this process, corporatized SOEs are subjected to “Western-style” standard internal and external supervision through a more or less direct application of Western-style (Anglo–American) corporate governance models (see Figure 1). Scholars who have addressed the extent of the implementation of this model expect the trend towards Western governance structures to continue.Footnote 38

Figure 1: Formal Corporate Governance Structure of State Holding Companies as Presented on Official Webpages

Source:

OECD 2011, 18.

However, the understanding of Chinese corporate governance gained from the perspective of an Anglo–American Western model is incomplete and can be misleading owing to the governance structure of the Chinese political economy, which increasingly centres on the CCP.Footnote 39 First, SOEs and corporate organs in SOEs are regulated not only by laws and formal state regulations but also by internal CCP regulations. Notably, Party organizations inside SOEs are primarily regulated by the Party's internal rules and regulations rather than the Company Law or CSRC regulations. Second, modern-day SOEs have grown out of the socialist planned economy, and aspects of the former management philosophy and practice still exist today. Political logics rather than economic rationales often set the direction of SOEs. Despite the crucial role of the Party organization, current regulations do not require disclosing even basic information such as the composition of the enterprise Party committees or their meeting dates. Indeed, the Party organization is not included on official webpages or in company presentations (see Figure 1 above). With a focus on the role of the Party organization, below we analyse: 1) the legal and regulatory frameworks of SOE governance; 2) decision-making procedures; and 3) appointment mechanisms.

Regulatory Frameworks of Party Involvement in SOE Governance

The legal basis justifying CCP involvement in enterprise governance can be found in the Company Law of the People's Republic of China. Article 19 stipulates that: “Companies, according to the Constitution of the CCP, shall establish Party organizations to carry out Party activities. The company shall provide necessary conditions to facilitate the activities of the Party organization.”Footnote 40 The Party formally plays a similar role in listed SOEs. The 2018 revision of the “Code of corporate governance for listed companies” stipulates that listed companies should establish internal Party organizations and facilitate their work. Moreover, the code requires state-controlled listed companies to incorporate Party-building work into their Articles of Association.Footnote 41

This regulatory framework provides a legal foundation for the CCP's penetration into all Chinese companies, but it does not specify the Party's exact role and relations with other corporate organs in different types of enterprises. Except for in Article 19 of the Company Law and Article 5 of the CSRC regulations, the Party is not mentioned in Chinese laws governing corporate governance. The Party's influence is better judged on the basis of the Party's internal rules and regulations specifying the Party organization's role in corporate governance, as well as in “guiding opinions” from the SASAC and the State Council. Even though the Party's internal regulations in principle are not legally binding, in practice they are often superior to national laws and government regulations.Footnote 42 A comprehensive overview of the most important laws, regulations and guiding opinions regulating the Party's role in SOE corporate governance is shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Selected Regulations and Laws on the Party's Role in SOE Corporate Governance

Source:

iCCP 2020; iiNPC 2018; iiiCSRC 2018; ivCCP 2018; vCCP 2017b; viSASAC 2017; viiState Council 2017; viiiMOF 2017; ixCCP 2017a; xSASAC 2016; xiCCP 2015b; xiiState Council and CCP 2015; xiiiCCP 2015a; xivSASAC and CCP 2013; xvCCP 2010; xviSASAC and CCP 2004. Restricted to October 2004–January 2020 period.

Decision-making Procedures

The basic principle for Party involvement in SOE corporate governance can be found in Article 33 of the Constitution of the CCP. The 2012 version of the Party Constitution stipulated that the basic Party organization of the enterprise was to play a “political core role” (fahui zhengzhi hexin zuoyong 发挥政治核心作用) and “supervise” (jiandu 监督) the implementation of the guidelines and policies of the enterprise. The revised 2017 Party Constitution changed the role of the enterprise Party organization to “play a leadership role” (fahui lingdao zuoyong 发挥领导作用) in terms of discussing and deciding on major issues (zhongyang shixiang 中央事项).Footnote 43

In order to make sure that Party leadership and Party building are fully reflected in the SOE reform, in 2015 the Central Committee released a set of new regulations on the role of Party organizations in the corporate governance of SOEs and mixed-ownership enterprises.Footnote 44 These indicate in unequivocal terms that the Chinese leadership is firmly committed to tightening Party control in the corporate sector. The regulations emphasize that in order to clarify the legal status of Party organizations in the corporate governance structure of state-owned companies, it is necessary to incorporate the overall requirements of Party-building work into SOE charters.Footnote 45 Following the new regulations, most of the larger SOE holding groups and their subsidiaries (see example below) amended their Articles of Association. There followed a number of additional documents on central and local levels which further clarified the position of the CCP in SOE corporate governance.Footnote 46

In 2016, Xi Jinping reiterated that the enterprise Party organization's prior research and discussion must occur before any decision making by the board of directors and managers.Footnote 47 In fact, according to Xi, the “special element” in the state-owned Chinese enterprise system is, “in particular, the integration of the Party's leadership into all aspects of corporate governance.”Footnote 48

Organizational Set-up

Although the Party had been steadily inserting itself into SOE corporate governance, its first comprehensive release of information on the organizational set-up of increased Party presence appeared in January 2020. The “Working regulations of the Communist Party of China concerning primary Party organizations in state-owned companies” are the first public clarification of how the Party sees its corporate role being implemented in organizational terms, and they update previous working regulations for Party groups.Footnote 49 They are the culmination of five years of measures and initiatives and provide us with unique insight into the Party's current thinking regarding its role in Chinese business governance.Footnote 50

According to the new working regulations, Party members should establish a Party committee (weiyuanhui 委员会) in companies employing more than 100 members; a Party general branch committee (dang zhibu weiyuanhui 党支部委员会) in companies with 50–100 members; and a Party branch (dang zhibu 党支部) in firms with 3–50 members. With the approval of the Central Committee, centrally managed enterprises should also set up a Party group (dangzu 党组).

The regulations stipulate that the Party secretary of the Party committee (Party group) should serve as chairman of the board of the company, and the general manager should serve as deputy secretary. In general, and in accordance with the principle of “bidirectional entry, cross appointment,” members of the Party committee (Party group) should join the board of directors, board of supervisors and the management team, and vice versa. The Party organization of subsidiaries of central enterprises guides and supervises Party organizations in their own subsidiaries.

Article 15 of the 2020 regulations states that major matters (referring to sanzhong yida) of SOEs must be discussed by the Party committee (Party group) before the board of directors can make a decision. Major matters include: (i) major measures to carry out Central Committee decisions; (ii) the implementation of the national development strategy as well as the implementation of enterprise development strategies and plans; (iii) property rights transfers, large investments and restructuring of corporate assets; (iv) the establishment and adjustment of the corporate organizational structure; and (v) major matters involving production safety, employee rights and interests, and social responsibilities of the enterprise.Footnote 51

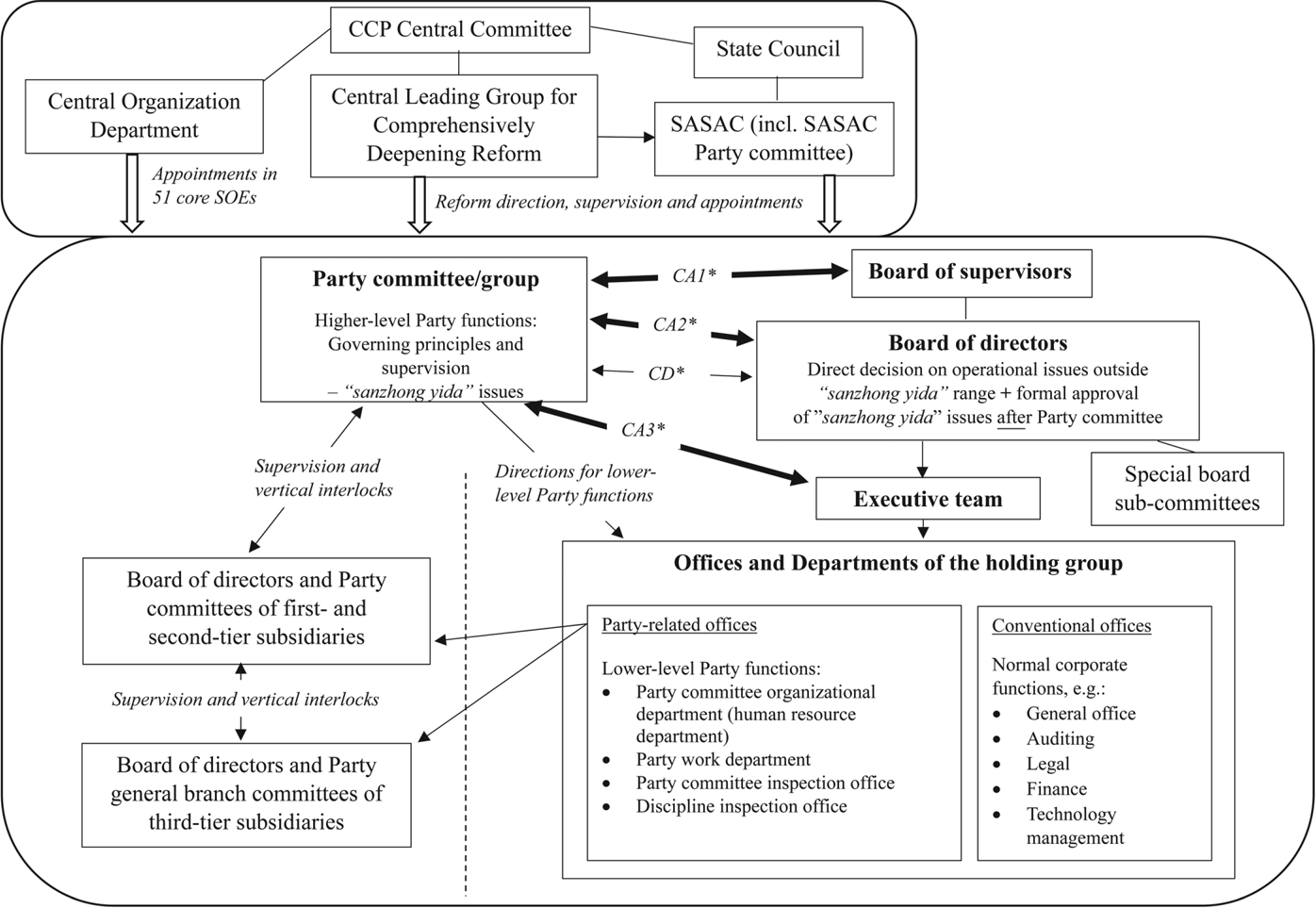

The 2015 regulations emphasized that decision making in SOEs should be carried out “collectively” by the relevant Party committee, the board of directors and senior management, in accordance with the sanzhong yida decision-making principle (see discussion in relation to Figure 2). While the 2020 regulations still refer to the sanzhong yida, they emphasize a decision-making structure that is less collective in the sense that ultimate decision-making authority is vested in the Party committee (group).

Figure 2: Corporate Governance Structures in SOE Holding Groups with Boards of Directors

Sources:

Authors' illustration based on interviews and CECEP organizational structure.

Notes:

*CA = cross appointments; CA1 = chairman of the supervisory board; CA2 = chairman of the board -party secretary; CA3 = general manager-Party vice-secretary, head of the discipline inspection team + one to two other managerial deputies. CD = collective decision-making.

The Party's embeddedness in enterprise organization is reflected in the structure of departments and offices. In our case study of the central-level SOE, China Energy Conservation and Environmental Protection Group (CECEP), we found that four of the 17 departments are directly related to the CCP organization and its lower-level work (see Figure 2). First, a “Party committee organizational department” (dangwei zuzhibu 党委组织部) is embedded in the human resources department and controls appointments. Second, a separate “Party work department” (dangqun gongzuobu 党群工作部), comprising a corporate culture department, trade union office and veteran cadre office, is in charge of Party-building activities throughout the enterprise.Footnote 52 Third, a “Party committee inspection office” (dangwei xunshiban 党委巡视办) is in charge of ensuring that decisions are implemented. Finally, a member of the enterprise Party committee heads a “Discipline inspection office” (jiwei bangongshi 纪委办公室), which investigates corruption and enforces Party discipline.

Appointments and Personnel Management

Control of personnel is one of the most important ways in which the Party institutionalizes its power over all economic and political organs in China.Footnote 53 Through the nomenklatura system, the CCP controls all appointments, promotions, transfers and removals of officials in China. Top executives are often reshuffled between Party, business and government positions.Footnote 54

The CCP's Central Organization Department (COD) directly controls personnel of the central SOEs that are ranked at either the ministerial or vice-ministerial level (the general manager and the chairman) – currently 51 out of the 96 central SASAC enterprises.Footnote 55 Consequently, although it is the nominally controlling shareholder, SASAC does not control top appointments in its own companies. Deputy-level positions such as deputy chairman and deputy general manager in the largest central SOEs are appointed by the Party's organizational department within SASAC, assisted by a separate SASAC division called the First Bureau for the Administration of Corporate Executives. SASAC's Second Bureau for the Administration of Corporate Executives appoints the remaining central SOE top executives. Appointments are made with inputs from the individual SOE Party committees; central SOE appointments are also subject to approval by the State Council.Footnote 56

At lower levels, the local CCP organization departments and local SASAC organizations control the appointment and dismissal of local cadres, including the top three leadership positions in local SOEs.Footnote 57

Bidirectional Entry, Cross Appointment

The principle of “bidirectional entry, cross appointment” (BECA), which is essential for enterprise corporate governance, demands special attention. According to a local SASAC official, BECA is the main principle for the Party's leadership over SOEs.Footnote 58 The principle implies extensive horizontal interlocks between the Party organization and other corporate organs. One person simultaneously holds the positions of Party committee secretary and chairman of the board. Furthermore, the general manager, the chairman of the supervisory board and the head of the discipline inspection team (the secretary of the discipline inspection office) must have seats on the enterprise Party committee. In addition, one to two other managerial deputies (such as the chief accountant) should also be members of the Party committee.Footnote 59

The outline of this institutional arrangement was first proposed in 2004,Footnote 60 and was later specified in 2013 and 2015.Footnote 61 The 2004 document was released in connection with the first experiments with boards in state-owned sole proprietorship companies. By the end of 2017, 90 per cent of the leaders of China's core central SOEs served simultaneously as chair of the board and Party secretary.Footnote 62 This is up from about 20 per cent during the Hu administration (2003–2012), when general manager–Party secretary interlocks were the norm.Footnote 63

For example, as of October 2019, the Party group in China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), a central SOE holding group, had eight members (see Table 2), six of whom simultaneously held top management positions: the chairman of the board, the general manager, the chairman of the supervisory board, the head of the discipline inspection office, the chief accountant (i.e. chief financial officer) and the chief safety monitor. With this level of insider control, the Party group dominates corporate decision making. In addition, many of these Party group members simultaneously held positions in the publicly listed subsidiary company – as board members and/or members of the subsidiary Party organization (vertical interlocks). For example, Liu Yuezhen 刘跃珍 was simultaneously a Party group member, chief accountant of the parent company and non-executive director of the subsidiary. Similarly, Liu Hongbin 刘宏斌, in addition to being a member of the Party group, was also deputy general manager of the parent company and non-executive director of the listed subsidiary. Wang Yilin 王宜林 held three powerful positions at the same time: chairman of the board and Party secretary in the CNPC holding group, and chairman of the board in the listed CNPC subsidiary company. This structure not only secures both horizontal managerial interlocks within the holding group according to the “bidirectional entry and cross appointment” principle but also vertical interlocks between the holding group and its listed subsidiary.

Table 2: “Bidirectional Entry and Cross Appointment” Principle in CNPC

Source:

Webpage of CNPC holding group, personal profiles of top leaders. Positions as of October 2019. NA = no position.

Changes to Articles of Association to Integrate the Party into Corporate Governance Structures

In 2017, the COD and the Party committee of the central SASAC issued a notice to all local- and central-level enterprises that provided guidelines on the process of changing the enterprise Articles of Association to accommodate a direct role for the Party in corporate governance in terms of decision making and corporate appointments and supervision.Footnote 64 The Ministry of Finance issued a parallel notice for financial enterprises a few months later.Footnote 65

The COD notice stresses that writing the Party into the Articles of Association is an important institutional arrangement for establishing the statutory status of the Party organization in the corporate governance structure of the company.Footnote 66 It further stresses that the requirements for Party-building work should be clearly defined in every company's Articles of Association, including the legal status, role and responsibilities of the Party organization and the Party organization's staffing and funding.Footnote 67

The January 2020 regulations on the work of primary Party organizations in SOEs clarify that charter amendments must include a formal statement that the Party organization's investigation and deliberation of major issues is pre-procedure for board directors’ and managers’ discussions and decisions.Footnote 68 From August 2015 through September 2018, 84 per cent of all listed SOEs – the public face of SOE holding groups – amended their charters.Footnote 69 Examples include the main listed subsidiary companies under Baosteel Group and Sinopec.Footnote 70 The same is true of listed mixed-owned enterprises with less than 30 per cent state-ownership, 75 per cent of which have amended their charters.Footnote 71 This broad implementation implies that the institutionalization of the role of the Party in corporate governance extends far beyond SOE holding group companies.

Case Study of China Energy Conservation and Environmental Protection Group

Figure 2 shows the Party's embeddedness in the corporate governance structure of CECEP, a central-level, non-listed SOE holding group with a board of directors system. The figure illustrates the horizontal and vertical interlocks of the Party organization and other corporate organs, the actual decision-making in the CECEP holding group (in particular, the relationship between the board and Party committee/group), and the functions of lower- and higher-level enterprise Party organs.

Interviews with CECEP officials highlighted the actual scope of the Party's role in internal decision-making procedures.

Lower-level enterprise Party functions include various Party-building activities, corporate culture initiatives, trade union work, management of retired cadres, tracking of decision implementation and investigation of Party discipline in the entire group. Organizationally, lower-level Party functions are placed in separate offices that are integrated among the conventional offices and departments (see Figure 2). Direction for lower-level Party functions is set out by the group Party committee. The Party committee organizational department has replaced a traditional human resources (HR) department and controls all appointments in the entire CECEP group.Footnote 72

Higher-level Party functions are strictly defined by the sanzhong yida principle formulated in 2010 under Hu Jintao.Footnote 73 In CECEP, the principle applies to first- through third-tier subsidiaries (including Party general branch committees) and covers:Footnote 74

• Important strategic decisions concerning implementation of party-state principles, policies, laws and regulations, and matters related to security and stability, in addition to enterprise development strategy;

• Appointments and dismissals of important personnel of mid-level or above in the enterprise holding group and in directly subordinate enterprises and units;

• Major project arrangements for projects that have an important impact on the scale of assets, capital structure, profitability, production equipment and technical conditions;

• The “one big” (yida 一大), which refers to large-scale capital operations, meaning “the transfer and use of funds exceeding the fund limit that enterprise leaders have the right to mobilize and use.”Footnote 75

Sanzhong yida decisions have to be submitted to the Party committee (group) before they are discussed by the board of directors.Footnote 76 All other operational issues do not go through the Party committee but are submitted directly to the board of directors.Footnote 77 CECEP officials emphasized that the main task of the Party committee is to set a strategic direction for the company and not to interfere in day-to-day management: “What the Party committee actually manages is governing principles (yuanze 原则) and supervision (jiandu 监督). Pre-announcement in decision making is to set the direction [for the board of directors] … It is similar to a supervisory department.”Footnote 78

Despite the dominance of the Party committee, CECEP officials also emphasized that the firm's decisions are made on a commercial basis and that the independent directors have an important say in evaluating the commercial feasibility of major projects.Footnote 79

CECEP officials also highlighted that Party committee members who enter the board are responsible for ensuring that board decisions are in line with the Party committee's recommendations, higher-level Party principles and policies, and laws and regulations, as well as ensuring that they do not damage national and social interests: “The biggest feature of state-owned enterprises is that they consider problems from the perspective of the country … The Party committee considers corporate social responsibility. This is the advantage of management with Chinese characteristics [i.e. with a Party committee]. I think it is necessary.”Footnote 80

In terms of the internal workings of the enterprise Party committee, interviewees emphasized that the committee makes decisions based on a principle of democratic centralism: “The entire Party committee meets, and everyone puts forward a unified opinion. The Party secretary does not have the final say.”Footnote 81 The interviewees highlighted the strengthened direct affiliation between higher-level Party organs in the central SASAC and the CECEP group-level Party committee.

Taken together, the CECEP case points to a Party apparatus that is now more vertically integrated and can exercise effective control over lower-level SOEs, thus potentially forestalling insider control and corruption.

Advantages and Disadvantages of China's Hybrid Model

After decades of reform and opening-up, including mass corporatization and the installation of a modern corporate governance system in the state-owned sector, the Party is now reasserting its control over Chinese businesses. As documented above, we are witnessing a movement towards a hybrid model of corporate governance that merges a Western corporate governance structure with a Party-centred political model. This fits with an overall trend of increased CCP oversight and control over all parts of Chinese society.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of the hybrid model? Viewed through a standard Anglo-American lens, stronger Party committees in corporate governance might be problematic for several reasons. First, they potentially undermine other reforms, such as the mixed-ownership reforms whereby private capital, management and talent are intended to make the SOEs more market-orientated and efficient. By weakening the position of the SOE board, private investors have even weaker incentives to invest in SOEs. The Party will have the decisive say in all major enterprise decisions as long as the enterprise is state controlled (absolutely or relatively).

Second, with the maintenance of the traditional political control elements in SOEs, the intended performance effects of other corporate reforms will likely not materialize. The problems that hold back SOEs (for example, the lack of management incentives owing to rigid administrative systems and soft budget constraints) are unlikely to disappear with increased Party control.Footnote 82 The implications of standard management theory therefore suggest that increased Party control will undermine progress towards the goal of improving SOE profitability and performance.

Third, since lines between the Party and legal governance organs are blurred, it is not clear whether the board of directors or the Party organization takes the final decision. Despite the effort of institutionalization of the Party into Articles of Association, SOE corporate governance rules remain uncertain, nontransparent and unpredictable, especially in the eyes of international and private investors.

However, we acknowledge that increased Party control over SOEs can generate a number of advantages. First, the Party committee's increased strength in SOEs can help facilitate smoother interaction with higher-level Party and government organs (notably the SASAC) and provide a better understanding of government policies and party-state objectives. In this way, compliance with laws and regulations can be secured. In addition, the increased vertical integration in the party-state hierarchy might work as a check on insider control and corruption.

Second, long-term strategic development goals can be facilitated by more direct intervention of Party committees (groups) in SOE decision making. Pressure to create short-term profits might ease. This includes ensuring that SOEs lead the way in China's newly announced green transition; if “green and sustainable” become key governing principles in SOEs, Party dominance in decision making might generate society-wide benefits.

Third, to the extent that the Party committee (group) only sets “the governing principles” and conducts “supervision” of misconduct, leaving the board of directors to make commercial decisions (as indicated in the CECEP case study), the Party-led structure of the hybrid model might allow SOEs more market autonomy. Ironically, acquiescence to formal Party supervision might lead to greater informal commercial autonomy, especially in competitive, open sectors. In addition, Party control of SOEs in “key” resource and utility industries with extensive non-profit objectives is both ideologically suitable for the party-state and a better economic alternative to attempting to regulate large private monopolies. The hybrid Party-led model of corporate governance might be a reasonable alternative form of market regulation in very large firms that operate in oligopolistic markets.

Conclusion

In line with the Xi Jinping era's general recentralization of the role of the Party in Chinese society, the Party has reasserted its control over Chinese big business. This time, the vehicle for strengthening the Party's role is the internal enterprise Party organization in the form of Party groups and Party committees. Starting in 2015, the CCP formulated an overlapping system of internal regulations, actively embedding itself into the formal governance structure of SOEs.

In SOEs and all companies controlled by SOEs (including listed and mixed-owned enterprises), the Party exerts its influence through the enterprise Party organization (Party group or Party committee) and its role in decision-making mechanisms, personnel appointment mechanisms and supervision mechanisms. Party Committees no longer focus only on trade unions and welfare issues; they are now actively involved in management issues. The result of legislation and regulations issued since 2015 is that the Party's dominance over SOEs has been strengthened, while the companies’ legal governance structure has been weakened. In place of a convergence with the Anglo-American model of corporate governance, a hybrid, Party-led model of corporate governance with Chinese characteristics has emerged. Some call this system “CCP Inc.” or “Party-managed state capitalism.”Footnote 83 In China, it is called “socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era.”

The advantage of this hybrid model lies in its strength in securing enterprise compliance, communication with higher state and Party organs, and in long-term development planning. As such, the Party's leadership inside SOEs can actively underpin the state-led model of economic development. The Party therefore continues to treat SOEs as its main “ruling foundation” (zhizheng jichu 执政基础).Footnote 84 On the other hand, the hybrid model is unlikely to help resolve efficiency problems and could potentially undermine other reforms, such as efforts towards mixed ownership. The party-state needs to finds a balance between its ambitions to maintain ultimate control and its desire to improve the performance, management and efficiency of the state sector.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a doctoral student grant from the Sino-Danish Center for Education and Research (SDC). The authors wish to thank Hong Zhao, Ari Kokko, Chunrong Liu, Yi Ma, Sarah Swider, Andreas Forsby and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this article.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical notes

Kasper Ingeman BECK is a postdoctoral researcher at the department of international economics, government and business, Copenhagen Business School. He holds a PhD degree in China studies from Copenhagen Business School. His current research covers Chinese state-owned enterprise reforms and governance; state-owned capital funds; state–Party–business relations; and state capitalist models of development.

Kjeld Erik BRØDSGAARD is professor of China studies at the department of international economics, government and business, and director of the China Policy Program, at the Copenhagen Business School. His current research covers state–Party–business relations; the nomenklatura system and cadre management in the CCP; the structure and impact of Chinese business groups; and Chinese economic thinking and development. His latest publications include Critical Readings on the Chinese Communist Party (4 volumes) (Brill, 2017) and The Chinese Communist Party since 1949: Organization, Ideology, and Prospect for Change (Brill, 2019).