When Sibelius’s balletic pantomime Scaramouche was performed at the Stockholm Royal Opera in 1924, the composer Moses Pergament hailed it as no less than ‘the most inspired [music] that Sibelius ever wrote’.Footnote 1 This level of praise formed a constant in the production’s reviews. The reviewer for Stockholms-tidningen wrote, ‘In the Finnish composer’s later works Scaramouche occupies a very prominent place: here Sibelius’s melodic inspiration flows, his imaginative power is undiminished.’Footnote 2 Despite its rapturous initial reception, Scaramouche remains one of Sibelius’s least-known works. It has not been the focus of a single musicological study; neither has it yet received its UK première.Footnote 3 This article redresses this issue by reading Scaramouche through its first production – staged in Copenhagen in 1922 and in Stockholm in 1924 – in order to explore first the significance of Scaramouche in Sibelius’s broader output; second, what the production’s context and reception can reveal about contemporaneous perceptions of Sibelius; and third, what the disjuncture between these views and present attitudes towards the composer indicates about the aesthetic sympathies of early twentieth-century Nordic composers more widely.

Benjamin Korstvedt wrote that the ‘critical opportunity’ of reception history lies in the moments where historical responses create ‘spaces of difference […] against our established patterns of comprehension’.Footnote 4 Contemporaneous reviews of Sibelius’s orchestral works painted him as a symphonist whose music conjured up visions of the Finnish landscape – an image which is much discussed in musicological writing on the composer today.Footnote 5 But the Scaramouche reviews present a different side of Sibelius. Here he was described as an erotic dramatist, and Scaramouche’s critical success depended on the score’s stylistic plurality and cosmopolitan sound.

The traces left by the ‘theatrical’ and the ‘symphonic’ Sibelius tell quite different stories about early twentieth-century Nordic culture. In contrast with the view that Sibelius was an ‘outsider’ in relation to an Austro-Germanic mainstream, as James Hepokoski puts it,Footnote 6 his dramatic works encourage a reorientation towards a view of the Nordic countries as their own geographical centre: looking from Scandinavia outwards, Sibelius was very much an ‘insider’. The Nordic countries had their own thriving theatrical culture, and for his stage music Sibelius mostly set texts by Nordic authors. Scaramouche was no exception: the scenario is by the Danish author Poul Knudsen (1889–1974).

Additionally, Scaramouche illuminates the importance of dance as a formative ‘modern’ genre within the Nordic countries. Discussions of Sibelius’s dramatic enterprises are frequently framed around his lack of a full-scale opera and the abandoned project The Building of the Boat. Footnote 7 However, this bypasses the fact that Sibelius did complete a full-scale balletic pantomime and a considerable number of incidental scores. During this period, Scandinavians considered contemporary dance to be one of the foremost progressive art forms, and incidental music was regularly commissioned for large theatre productions. Neither the theatre nor ballet were in confrontation with the onerous musical traditions and rhetorical burdens associated with operas and symphonies, so they were able to provide composers with a more liberating musical space in which to carve out their own pathways. Scaramouche was followed by other Nordic ballet pantomimes such as Okon Fuoko by Leevi Madetoja (1925–7, also with a scenario by Knudsen) and Bergakungen (The Mountain King) by Hugo Alfvén (1923), as well as ballets such as Viking Dahl’s Maison de Fous (The Madhouse, 1920) and incidental scores far too numerous to list here.Footnote 8 Attending to the widespread popularity of theatrical composition among early twentieth-century Nordic composers (rather than imposing a twenty-first-century model upon them which prioritizes opera and finds them wanting) offers a way of viewing their work that is more receptive to their own priorities.

As well as supplying an inroad into early twentieth-century dance culture, the first production of Scaramouche also provides a valuable perspective on Sibelius’s score. The performance brought together some of the leading lights of Scandinavian dance, who had conflicting stylistic priorities. The result was a stylistic potpourri, such that critics’ interpretations were divided between viewing the production as a symbolist allegory or as an expressionist drama. Sibelius’s music, however, was used to justify all arguments. The reviewers heard Sibelius’s music as both symbolist and expressionist. I argue that this illuminates a tension at the centre of Sibelius’s score – it is defined by stylistic plurality, and is consequently a vital score for understanding Sibelius’s compositional experimentation in the years between 1909 and 1914.

Sibelius in 1913

Scaramouche dramatizes the tragic consequences of an unfulfilled artistic life, in which creativity is stifled by social constraint. The story revolves around a love triangle between Blondelaine, a (female) dancer; Leilon, her lover; and Scaramouche, a hunchbacked viola player. Leilon refuses to dance with Blondelaine, but when Scaramouche plays at a party that they are hosting she dances herself into a fever to his music, seduced by the sound of his playing. Leilon banishes Scaramouche, but Blondelaine follows him. When she returns to Leilon in a fit of remorse, Scaramouche pursues her to their house. Panicking, Blondelaine stabs Scaramouche and hides his body behind a curtain. She then dances herself to death, and the pantomime ends with Leilon drawing back the curtain to discover Scaramouche’s body.

The genesis of Sibelius’s score was fraught with difficulty. It appears that when he signed the contract to score the pantomime in 1912, he was under the impression that he was to write only one or two dances. When he came to complete the piece, however, he realized that it required a full, through-composed score. Upon this realization, Sibelius wrote in his diary, ‘Ruined myself by signing the Scaramouche contract. Was so violent today that I broke the telephone.’Footnote 9 At this point he demanded a greater commission to be able to complete the work, as he felt that such a demanding undertaking would impact on his international reputation.Footnote 10 This was not the only incident which caused Sibelius special consternation. He had earlier accused Knudsen of plagiarism. He was struck by the similarities between Knudsen’s text and Arthur Schnitzler’s pantomime Der Schleier der Pierrette (The Veil of Pierrette, 1910), set to music by Ernő Dohnányi, and promptly wrote to his publisher, Wilhelm Hansen, to alert him. Undoubtedly, the similarities between the two dramas are uncanny (both involve a woman who dances herself to death after being seduced by a man whom she murders), but it was eventually decided that Knudsen was not guilty of plagiarism, and the commission continued.

Why did Sibelius persevere with Scaramouche despite these setbacks? At a practical level, one consideration may have been pecuniary. Sibelius’s excessive spending is well documented, and he might have felt unable to walk away from a commission.Footnote 11 But Scaramouche was not just a cause of anxiety for Sibelius. Only six days after destroying his telephone, he recorded on 27 June 1913 that he ‘worked these days and today on the pantomime. Have the feeling of being a genius. Such a wonderful Ego!’Footnote 12 On 10 April he had declared that ‘poetry is in the air. – Occupied with Scaramouche’,Footnote 13 and on 17 April, ‘The day is lovely. What outstanding poetry! Walked in the evening. Such days as this make it extremely difficult for me to be separated from [lined out: my] life. Suicide on such a day would for me be an impossibility. – Forged the S[caramouche] dance.’Footnote 14 These mood swings were entirely characteristic of Sibelius, but it seems that the pantomime provided him with a rich compositional stimulus as well as logistical strife. I suggest that there are two related reasons for Sibelius’s continued interest in the pantomime: first, that the text’s exploration of the connection between artistic and sexual expression was a topic of particular concern for Sibelius in 1913;Footnote 15 and second, that the genre offered Sibelius an opportunity for stylistic experimentation, which was especially valuable during these years when he was, as Hepokoski writes, re-evaluating his position as an international composer.Footnote 16

Sibelius’s diary entries from 1910 onwards express an increasing preoccupation with sexuality, creativity and ageing, often interrelating the three. On a trip to Paris in October 1911, he expressed trepidation about his passing youth. In a doleful diary entry on 31 October, he wrote: ‘Arrived here and revisited the old haunts. But the young drinking and smoking “Jean” is no more! Should it now be that the “zest” for life is over forever?!’Footnote 17 Such ruminations led him to ponder contemporary debates about the differences between male and female brains:

One could object that the ‘feminine’ has qualities which are incompatible with the workings of a man’s brain. But I do not believe it! In the best women I have known, femininity has not been bothersome, damn it. And the conversation has been of the highest quality. Never mind that the undercurrent is passion.Footnote 18

Of course, Sibelius’s diary entries cannot be taken entirely at face value. As Erik Tawaststjerna notes, it is unclear precisely for or to whom Sibelius was writing his diary, and some entries show subsequent revision as though he were later tempering his opinions to express a more balanced approach.Footnote 19 Nonetheless, they give a relatively unguarded insight into his state of mind, and the regular recurrence of particular topics illuminates his ongoing preoccupations. For Sibelius, feelings about his own physical well-being and maturity were inextricably interconnected with his thoughts about women and sexuality. Each passing year brought with it new anxieties about the effect of ageing on his sexual desires, whether mentally or physically. In 1915, only two years after Scaramouche was composed, he penned a substantial note in his diary dated 13 April, writing about his increasing age and the relative transience or constancy of romance:

We all live in anticipation of the spring. Eva and Arvi not least. A strange feeling for me to become a grandfather soon. So long, therefore, Jean Sibelius. And you played [the] young man in Gothenburg. One may not come with words of consolation: it is the mind not the body which determines its age. It is not so. Our body is probably a large part of the decision […] Every age like every season has its own distinctive feature – please God that I may be wise and prudent and above all new. You probably know Jean Sibelius, whose ecstasy and phrases never die! The sap rises sufficiently in you as in other trees of fifty years – and how! The vigorous old man! But the time when one sat on a bench in each other’s arms swearing eternal fidelity is probably past. – I say this now in the hope that it is the case. But this ‘repeated puberty’ of geniuses which Goethe talks about flatters me. – When I close my eyes I revel in a fantasy from long ago […] A real friendship!! – Maybe love. This ‘uncertainty’ penetrates into my bones.Footnote 20

Running parallel to his concerns about his increasing age were his worries about the status of his music on an international platform, as he compared himself to younger composers with whom he felt he had to compete. Sibelius’s letters and diary entries make increasing reference to composers such as Arnold Schoenberg, and the Scaramouche commission arrived only a month after a disagreement with the painter Eero Järnefelt in Helsinki, where Järnefelt had praised Schoenberg at Sibelius’s expense. This caused considerable tension, Sibelius concluding, ‘I was dejected – did not really defend my little compositional cross. […] I see clearly that my successes – good criticism etc. – have caused jealousy to many. And these are a priori my sworn enemies.’Footnote 21 He was also comparing himself to Frederick Delius the day before the commission came in, worried that his music might be misunderstood by audiences and critics.Footnote 22 This concern continued as he worked on the pantomime, writing on 15 February 1913, ‘My star is in descent. Can no longer interest the European public.’ Nonetheless, he was convinced that this was not due to the quality of his work. He continued, ‘Have perhaps not been enough of a follower […] One [thing] I know. That all my works are, in their nature, perfected art works.’Footnote 23 A few days later, an incident in Vienna whereby the musicians refused to play his Fourth Symphony returned him to worrying about his age:

The thing with Sinf. IV in Vienna! The orchestra refused to play. Probably the same case in Berlin. –This hurts! But perhaps time – wonderful time – counsels against even this. – I want to sell everything that I have, but – who is buying[?] What to do in this instance? – It is important now not to lose heart; as well as – above all – the head. They consider – at least most of the world’s orchestral musicians – that I am a dead man. Mais nous verrons! Should this be the end of Jean Sibelius as a composer?Footnote 24

Hepokoski has labelled the years between 1909 and 1914 as a ‘crisis’ period for Sibelius, during which he began ‘to feel eclipsed as a modernist’.Footnote 25 Undoubtedly, Sibelius was keenly aware of his ‘descending star’, and of whether his music was perceived as modern or not. But his artistic identity did not exist in isolation; it was amalgamated with his personal identity. The period before 1915 was a time of crisis for Sibelius because he began to feel eclipsed not just as a modernist, but as a man – his concerns about ageing and sexual maturity were as formative as his ‘prestige-rating in the institution of art music’.Footnote 26

His dramatic music offered a way to approach these more intimate concerns, and Scaramouche’s thematicization of the relationship between sexual and creative identities is a particularly potent example. Scaramouche represents the marginalized musician in a form which might well have appealed to Sibelius, who so often referred to himself in his diary as a persecuted artist, misunderstood by people to whom he refers as ‘Philistines’. The parallel between the two characters was recognized by Gunnar Hauch, who remarked that:

Sibelius’s music to Poul Knudsen’s Scaramouche can almost be read as a fable, equivalent to that given in the pantomime itself. Sibelius has been the demon Scaramouche, who lured poetry far away from the pale, young poet, out into the deep night, and breathed into it his own being, the wild song, the mystery of Pan in the dark forest. And when it then returned to its theatre, there was nothing that was the poet’s any more, rather everything was Sibelius.Footnote 27

But Scaramouche is not the only character with whom Sibelius might have identified. The empathetic relationship between the seemingly juxtaposed personalities of Blondelaine and Scaramouche resembles Sibelius’s apparently contradictory character traits. Mäkelä has argued that Sibelius was a man of two halves, calling him both the ‘homme naturel’ and the ‘homme civil’. According to Mäkelä, ‘Sibelius was […] not only someone who could establish contact with nature and who saw through the trap of the supposedly unspoilt nature of the mythological but was also an elegant “homme civil”, who moved about big cities like a “fish in water”.’Footnote 28 In this dualism we can see parallels with the passionate Scaramouche and the civilized Blondelaine, two aspects of the same person. And it is art – music and dance – that brings the two together. Without it, they both perish. As Mäkelä states, ‘In his heart of hearts, Sibelius probably indeed believed that a synthesis of nature and civilisation was possible through art’Footnote 29 – but he was ultimately paralysed by self-criticism. Similarly in Scaramouche, the overwhelming climax of the bolero hints at this synthesis, but it is denied and falls into silence. Later on, Scaramouche’s death is, remarkably, marked not by melodramatic chords, but by silence. In Scaramouche Sibelius seems to foreshadow his later withdrawal from publishing his music, indicating that silence can be the only outcome when creative life is controlled by anxieties about the judgment of others.

It would be nine years before Scaramouche received its première in Denmark. The reasons for the significant performance delay are unclear, but the piece has a unique combination of music, mime and spoken word which appears to have deterred a number of directors including (according to one newspaper) Max Reinhardt.Footnote 30 When it was eventually performed, therefore, Sibelius was a collaborator at a distance. There is no evidence that he was involved with the Danish or Swedish stagings, or that he even saw the production.Footnote 31 (By comparison, he had conducted some performances of his previous incidental music, such as Svanevit (Swanwhite) at the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki in 1908.) Therefore, the first public hearing of Sibelius’s music, and subsequently the first critics’ reception of it, was highly mediated by the director, choreographer, dancers and designer, and was interpreted more through the aesthetic concerns of the 1920s than those of the previous decade. In this context, despite being composed nine years previously, Sibelius’s score was mostly read as innovative and experimental, inheriting some of the connotations generated by the other collaborators. Consequently, the reception history of Sibelius’s score is inextricably bound up with the 1922 and 1924 productions, whereby the music became one element in a historically contingent intersection of ideas cohering within a single performance event.

The context: Denmark

The first production was directed by Johannes Poulsen and choreographed by Emilie Walbom, with set designs by Kay Nielsen. When it was restaged in Stockholm in 1924, apart from the dancers (the Norwegian dancer Lillebil Ibsen took the role of Blondelaine in 1922 and Poulsen himself danced Scaramouche, while the Swedes Ebon Strandin and Sven D’Ailly performed the main roles in 1924), the production was entirely the same. The reception, however, differed wildly between the two countries, reflecting significant differences regarding the status of dance. Despite Denmark’s and Sweden’s geographical proximity, their dance cultures developed at very different speeds (Sweden’s much faster than Denmark’s), and this is reflected in the critical writing about Scaramouche. Danish criticism of the production was polite and mostly positive; but without an established critical framework from similar productions, reviewers largely avoided interpreting the drama. Swedish critics were not so reserved in their interpretations. They read Scaramouche in the light of debates about the relationship between dance, music and the body that had been raging in Swedish papers for the past ten years.

The Scaramouche collaboration was conceived as a conscious attempt to modernize Denmark’s ballet. Throughout the first decade of the 1900s, both Stockholm’s and Copenhagen’s dance cultures were characterized by conservatism. The choreography of August Bournonville (1805–79) remained dominant in the Royal Ballets of both countries. Bournonville’s status was guarded especially fiercely in Denmark; around 1905, the year of his centenary, several publications appeared declaring the ballet master’s superiority. The critic Ove Jørgensen used the opportunity to denigrate both Isadora Duncan and Loïe Fuller, who came to Denmark to perform in 1905. He dismissed the former as an ‘American dilettante’ and accused the latter of presenting merely ‘quasi-philosophical experiments’.Footnote 32

A turning point for Danish dance came in 1918, when Mikhail Fokine and Vera Fokina came to Copenhagen and staged a series of productions as guest artists at the Royal Theatre. Fokine’s choreography was in direct contradiction of the Bournonville heritage. Bournonville, influenced by French ballet, emphasized grace, effortlessness and a limited use of the arms. Fokine, however, based his choreography on the principles that he laid out in his 1914 letter to The Times: that the ‘new ballet’ should not use ‘combinations of ready-made and established dance-steps’; that dance and gesture must ‘serve as an expression of its dramatic action’; that choreography should strive to ‘replace gestures of the hands by [a] mimetic of the whole body’; that all dancers on stage must be expressive; and that productions must be built upon an ‘alliance of the arts only on the condition of complete equality’, granting equal status and liberty to choreographer, scenographer and composer.Footnote 33 The critic Helge Wamberg wrote that Fokine’s Danish productions were nothing short of a ‘revolution’,Footnote 34 and that the performances were well received by audiences who ‘cheered the fact that Bournonville was dead’.Footnote 35

Discussions about Danish dance revolved around the differences in bodily movements between the old and new dance styles. The body, and how it could be disciplined, was foregrounded in debates across various fields thanks to the prevalence of vitalism (the belief that humans and nature are connected by a single life force) in early twentieth-century Danish culture. In dance, the vitalist trend was reflected in attempts to ‘remasculinize’ choreography for male dancers. Hans Beck, ballet master of the Royal Danish Ballet between 1894 and 1915, aimed both to preserve Bournonville’s legacy and to exaggerate the difference between male and female training and performance. Jørgensen particularly approved of Beck’s innovations, writing that he had

succeeded in removing everything unmanly in the art of the dancers and created a distinctly virile dance, where the flaming power and appeal of the steel-strong male body and its movement, refined through the laws of beauty and the use of musical rhythms, create the most wonderful contrast to the more voluptuous and graceful suppleness of the female body.Footnote 36

Walbom entered this politicized arena as the Royal Danish Ballet’s first female choreographer in 1906. She was denied the post of ballet master (Beck was instead succeeded by Gustav Uhlendoff ), but was appointed the company’s first ballet mistress in 1915. Her choreographic style was controversial. Although there were some points of continuity between herself and Beck,Footnote 37 Walbom moved away from Bournonville and instead turned to Fokine for inspiration. Her style was perceived as international and modern, particularly in her stress on plastique. The term plastique (and its Danish and Swedish translations, plastik or plastisk) was used throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to refer to a type of fluid, malleable physical expression that aimed to sculpt the body into an ideal form. It was originally associated with attempting to develop the body according to the ideals of antiquity,Footnote 38 but by the late 1910s the ideal had changed. Developed in close collaboration with theatre and pantomime, twentieth-century plastique came to indicate free movement that focused on the dancer’s individual expression – prompting an association with expressionism – rather than cultivation of a formal system of signs and gestures as per Bournonville.Footnote 39 Walbom’s plastique choreography was based on Fokine’s principles, and when she staged her 1918 Fokine-inspired ballet A Night in Egypt, reception was divided between those who fretted about the Royal Danish Ballet’s move away from the Bournonville heritage and those who embraced the new form of choreography.Footnote 40

Poulsen was instituting a parallel upheaval in the theatre. He made his directorial début at the Copenhagen Royal Theatre in 1914, with a production of Everyman heavily influenced by Reinhardt. Throughout the 1910s, realism was the predominant style at the theatre. Poulsen’s Everyman was a clear statement against the trend for using a ‘historically accurate environment’ for the play’s aesthetic.Footnote 41 The stage (designed by Svend Gade) consisted of three stylized, symbolic realms – Heaven, Earth and the Grave – connected by steps, while the costumes were inspired by medieval Danish frescoes. In the year of the production Poulsen wrote to the critic Otto Borchsenius that ‘the realistic-naturalist period of the [Georg] Brandes followers is now over’, and that he was going to turn to large-scale drama that aimed at a mass audience instead of catering for the Royal Theatre’s traditional small group of bourgeois patrons.Footnote 42

Both in his move away from realist theatre and in his desire to reach mass audiences, Poulsen formed part of a wider Scandinavian trend. Also heavily inspired by Reinhardt, Poulsen’s Swedish contemporary Per Lindberg tried to establish a ‘popular’ theatre at the Lorensberg in Gothenburg, where he served as artistic director from 1919 to 1923.Footnote 43 He, like Poulsen, believed that in order to create a theatre that had mass appeal, realism needed to be dispensed with.Footnote 44 Lindberg’s reasoning was that expensive, intricate realist sets kept ticket prices prohibitively high, and besides this the lack of theatrical spectacle in realist theatre made shows less enjoyable to watch, limiting their interest.Footnote 45 Theatre directors of this generation were trying to create a theatre that they felt was appropriate for the move towards social democracy in 1920s Scandinavia, a theatre that could be ‘an artistic forum for contemporary thought, a mirror of contemporary life, a portrayal of its social, moral and psychological problems’.Footnote 46

To complete the core artistic team, Poulsen hired Kay Nielsen as the set and costume designer. Now better known for his fairy-tale illustrations, Nielsen designed for a considerable number of Poulsen’s productions, including the 1919 Aladdin with music by Carl Nielsen, and the première of The Tempest with music by Sibelius.Footnote 47 He brought a completely different flavour to Walbom’s Russian influences and Poulsen’s German inspirations. Nielsen’s work was closer to art nouveau and fin-de-siècle symbolism, influenced by Aubrey Beardsley, Japanese woodcuts, Chinese prints and the Pre-Raphaelites.

When they came to collaborate on Scaramouche, then, the core members of the artistic team were separately established as pioneers ushering in a new age on Denmark’s stages. Scaramouche was conceived in the same spirit of rejuvenation, being the second in a series of experimental collaborations.Footnote 48 Poulsen did not try to coordinate the different personalities involved to produce one coherent directorial ‘vision’, but instead allowed their different styles to exist in agonism with one another. On the day of the 1922 première, Poulsen gave an interview in Berlingske tidende in which he said, ‘One finds that they are still finding new ways for dramatic art abroad, and that is what we are going to try [at home] with Scaramouche […] The theatre arts need renewal, but renewal can only come through experiments.’Footnote 49 Because the dance revolution in Denmark was so recent, and so significant in the dethroning of Bournonville, and on account of ballet’s combination of multiple media, in 1922 dance was the experimental Danish art form. This was the context in which Danish critics viewed Sibelius’s music. When they wrote about his contribution to the production, they were assessing it as part of an experimental collaboration that attempted to interact with international theatrical developments, building a new alternative to the Bournonville tradition.

The context: Sweden

Without a figurehead of standing comparable to Bournonville, Sweden’s dance life had been much faster to reform than Denmark’s. Dance was seen as a platform for ‘modern’ expression much earlier in Sweden than it was in Denmark. Fokine and his choreography had been on Stockholm’s stages since 1913, and while living in Stockholm, Fokine had tutored a number of young Swedish dancers including Jean Börlin, who would go on to lead the Ballets Suédois. The Suédois, financed by the impresario Rolf de Maré, ran for three years between 1920 and 1923 in Paris, during which time it earned a reputation as a significant rival to Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes.Footnote 50 On the basis of this more active cultivation of contemporary dance, Swedish newspapers ran theoretical articles throughout the 1910s that discussed the future of dance forms and the relative merits and shortcomings of different approaches.

One of the main points of contention was whether dance should exist as an independent art form, or merely as a means of interpreting the music that it accompanies. Émile Jaques-Dalcroze’s eurhythmics was particularly popular in Sweden, his philosophy being that the body was an instrument for musical interpretation, and should be cultivated as a tool to express responses to music physically. Dalcroze schools were set up to follow his pedagogical principles, teaching a combination of eurhythmics, solfège and improvisation. One of the leading proponents of eurhythmics was Anna Behle. Having studied with both Duncan and Dalcroze, Behle set up the first eurhythmics school in Stockholm in 1907 and was an outspoken advocate of the Dalcrozean method. She had begun as a music student, studying at the Stockholm Royal College of Music, and remained passionately convinced of dance’s primary purpose as a method of musical interpretation. In 1912, she wrote an article for Dagens tidning explaining that Dalcroze’s method – and therefore hers as well – ‘attaches particular importance to the perception of the music. The dance – or rather the gestural preparation – as he allows his students to perform it, should work with means that are as simple as possible and in an immediate fashion follow and express the music’s mood.’Footnote 51 Although she praised Duncan’s dancing in the same article, she was by now a sufficiently established figure to criticize her former teacher, saying that ‘Duncan danced without any musical understanding in deeper terms […] she rarely succeeds in producing every composer’s particular mood in a satisfying way, even though movements and poses may be able to fit the form’.Footnote 52

Behle was not alone in her belief that dance should be a method of musical interpretation. An anonymous author writing for Borgåbladet (a Swedish-language Finnish newspaper) in the same year similarly argued in favour of Dalcroze’s attitude towards dance. ‘In order for a dance or other gestural production to be a work of art, whose value is comparable to the music which is produced,’ they wrote, ‘the human body must follow and express the music’s overall rhythmic and musical crescendos, decrescendos and accents.’Footnote 53 They extolled the virtues of Dalcroze’s techniques, emphasizing that eurhythmics has a spiritual dimension that trained dancers almost to channel the ‘spirit’ of music:

What this school demands of its disciples is above all to listen, first and foremost to the music’s modulations in every detail in a simple, natural and artistic manner. Through both a serious spiritual and physical education, they must learn to create from their bodies a sensitive instrument which vibrates with and gives expression to all the emotional range’s shifting nuances.Footnote 54

Praising dance’s complete subordination to musical expression was not universal, however. Some practitioners and theorists took a different perspective, viewing dance as an art form born of music, but best understood on its own terms rather than as an act of interpretation. In 1912, Björneborgs tidning, another Swedish-language Finnish newspaper, republished an article by the Austrian dancer Elsa Wiesenthal, originally published in the Viennese newspaper Neue freie Presse. Footnote 55 She expressed a desire for a self-referential dance form, understood independently of its relationship to dramatic arts, saying, ‘Dramatic and dance art can meet – as in the pantomime – but the pure dance art is an art like music, out of whose sound and rhythm it is born.’Footnote 56 While she viewed music and dance as the most closely related art forms and acknowledged the importance of music for dance, she argued in favour of compositions that best served dancers. She expressed a hope that Dalcroze’s eurhythmics would ‘bring […] musicians much closer to the dance’, lamenting that ‘there are so few modern composers who write really effective dance music for the stage’.Footnote 57

At the far end of the spectrum were those who argued in favour of an autonomous dance form, independent of all other art forms. The composer Viking Dahl published an extensive article on dance in Svenska dagbladet in 1919. In it, he condemned contemporary dance as regressive in comparison with its sister arts. He reserved particular scorn for dance when combined with other art forms; he believed that dance was not yet at the stage where it could obtain a pure enough form of expression to withstand combination. He wrote: ‘I dare to imagine a dance art self-contained and absolutely independent of other art forms, such as music. We have “pure” music, “pure” painting, “pure” sculpture […] why can we not also have a “pure” expressive gestural art?’Footnote 58

This debate formed the backdrop against which Swedish critics approached the 1924 performance. As we shall see, they mapped their readings of the pantomime onto these arguments (and vice versa). The reviews that favoured a symbolist interpretation expressed the view that dance should be subordinated to music. Those that saw in Scaramouche an expressionist drama emphasized the independence of dance.

In both Denmark and Sweden, then, dance was a serious modern art form worthy of debate. This context throws a new perspective on Sibelius’s comment: ‘Opera is […] a conventional form of art and should be cultivated as such.’Footnote 59 Dance, not opera, was at the forefront of Nordic artistic developments through the 1910s and 1920s, and this perhaps steered Sibelius in the direction of producing a balletic pantomime rather than an opera during these years when he was negotiating his position on an international platform. A ‘conventional form of art’ could not serve a composer concerned with becoming a pioneer of the twentieth century rather than a relic of the nineteenth – but the ballet pantomime could.

Reviewing the music in context

One interpretation of the Scaramouche story, in which the dancers are purely symbolic, is allegorical. Many turn-of-the-century texts about dance, such as Hugo von Hoffmansthal’s 1911 essay ‘On Pantomime’ and Stéphane Mallarmé’s 1886 essay ‘Ballets’, envisaged the dancing body as a symbolic means of expression, eliminating the body as corporeal form. Mallarmé’s ‘Ballets’ renders this explicit. His dancer entirely ceases to be, evaporating into nothingness beyond the role of symbol: ‘A [female] dancer is not a woman who dances, […] she is not a woman, but a metaphor summarising one of the elementary aspects of our form.’Footnote 60 The emphases are Mallarmé’s own: he deletes not only the individuality of the dancer, but continues to extract her gender – ‘she is not a woman’. The female body and mind are erased as extraneous blemishes. In Scaramouche, this conception of the body as signifier is reflected in the interaction between Blondelaine and Scaramouche, which can be read as symbolizing dance’s dependence on music.

An alternative, expressionist interpretation highlights Blondelaine’s psychological unravelling as the central theme of Scaramouche, focusing on the more corporeal and sexual aspects of the drama. The sensuality of the dancing body – particularly the female body – was foregrounded by the unbound movement of dancers such as Fuller, Duncan and Maggie Gripenberg. Their performances formed part of a wider discourse about, as Harold Segel puts it, redefining ‘the role of women in society, of the place of woman in the family, and of traditional attitudes towards female sexuality’.Footnote 61 Even in their choice of clothing, these dancers challenged their audiences to address their physicality directly, their loose-fitting garments and bare feet allowing them greater range and freedom of movement. Women expressing their sexuality through dance was a source of anxiety for many authors, and Blondelaine is one in a plethora of early twentieth-century women who dance themselves to death, becoming sacrifices to their own sexuality – unable to control their bodies, they are overcome by their sexual desires and dance themselves into an early grave.Footnote 62

The first production capitalized on the dual interpretative possibilities of Scaramouche. Kay Nielsen’s set encouraged a symbolist reading (see Figure 1). The stylized backdrop, familiar from Nielsen’s fairy-tale illustrations, is so cavernous that it diminishes the physicality of the figures in the foreground. Blondelaine and Scaramouche are dominated by the opulent decorations that cover the walls, their bodily struggle insignificant against the unforgiving straight lines that segment the stage. This was exacerbated by the costumes. Scaramouche’s costume depicts him as a shamanic figure (see Figure 2) – his clothes are covered in symbols and geometric designs, with talismans hanging from his belt, his appearance reinforcing the sense that, as Pergament put it in 1924, the music adds ‘a cosmic power’.Footnote 63 Additionally, his costume allows for more freedom of movement than Blondelaine’s relatively formal attire. Scaramouche’s tattered cloak and esoteric appearance alludes to a greater freedom than that offered by the constraints of Leilon and Blondelaine’s world, visually symbolizing his resistance to the societal norms embodied by Leilon and his friends.

Figure 1 Kay Nielsen’s set design for Scaramouche. Image public domain.

Figure 2 Kay Nielsen’s costume for Scaramouche. Image public domain.

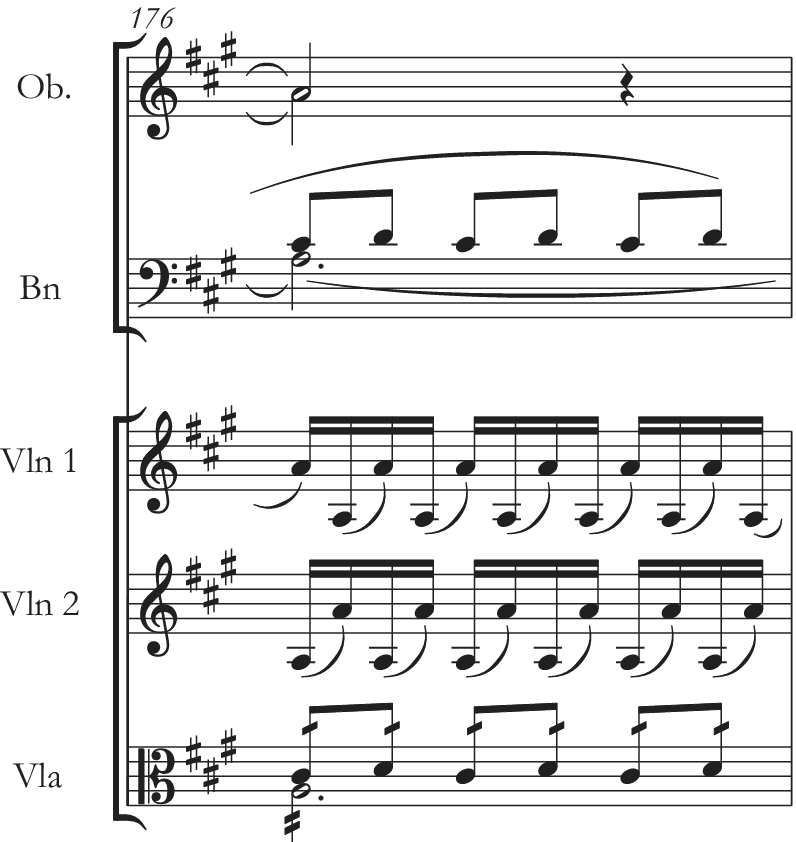

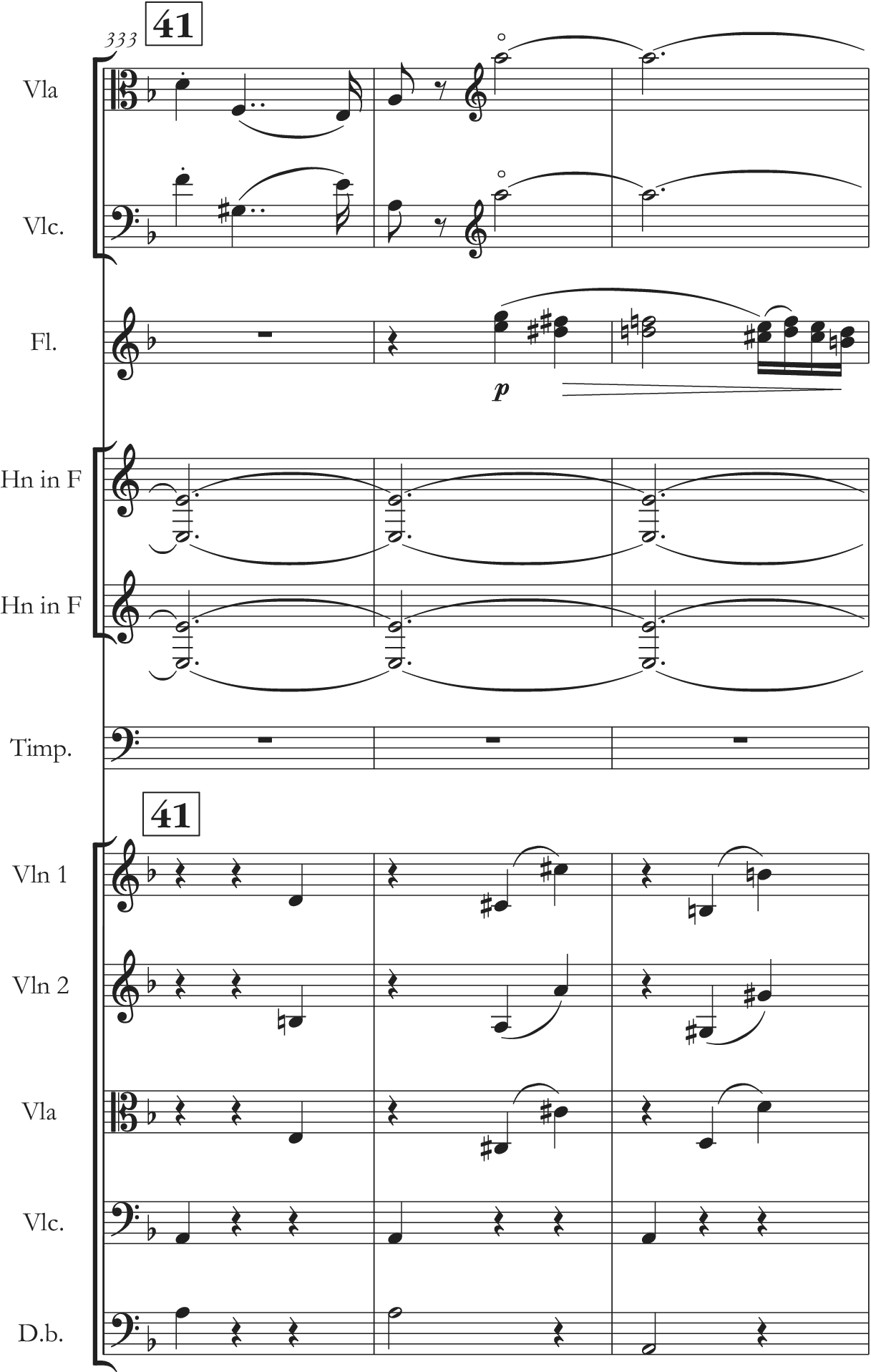

Providing a counterpoint to Nielsen’s ethereal designs, however, was Walbom’s far more bodily, expressionist plastique choreography. The corporeality of the dance was mentioned repeatedly by the Swedish reviewers of the 1924 production, some of whom offered an especially valuable glimpse into how Walbom choreographed the piece, and the effect of her work. Pergament complained that her choreography did not align precisely with Sibelius’s music, lamenting that she ‘apparently saw no intimate connection between the musical motifs and the dance’s movement motifs’.Footnote 64 Certainly, Sibelius’s music is gesturally evocative, particularly in the bolero, with the accented off-beats in bars 324–5, for example (see Example 1d, p. 442). But if we are to believe Pergament, Walbom made a distinct aesthetic choice to move away from a precise synchronization between music and gesture. Rather than focus on Blondelaine-as-symbol, her choreography foregrounded Blondelaine-as-woman, dancing for the pleasure that it gives her and because of her sexual connection to what Scaramouche and his music represent.

Walbom’s interpretation was complemented by Poulsen’s direction. Rather than downplaying the carnal aspect of Blondelaine’s attraction to Scaramouche and his music, Poulsen’s staging emphasized it as much as the conceptual relationship of music to dance. For example, he inserted a tableau at the end of the first act which showed Blondelaine and Scaramouche embracing. At this point in the drama, the text indicates that Blondelaine leaves to find Scaramouche, saying, ‘That is his violin [sic]. Ach, how he sings and calls!’Footnote 65 before running off-stage. Poulsen, however, made the decision to have the lovers embracing on-stage, making their union explicit.

Weaving together all these elements was Sibelius’s music. The score is through-composed, scored for a small orchestra and defined by stylistic plurality. The harmonic and timbral language is consistent throughout, but like Poulsen’s production, Sibelius’s music draws on a constellation of complementary styles, employing them topically to structure the score. Scaramouche presents a significant analytical challenge: because it is first and foremost a dramatic work following the structure of the text, its form is not adequately explained by analytical models developed for Sibelius’s symphonic music. It does not adhere to the idea of a ‘rotational/teleological structure and […] secondary dialogue with the sonata deformational principle’ devised by Hepokoski; nor to the large-scale process of tonal resolution promoted by Veijo Murtomäki, designed to demonstrate how the symphonies are ‘organically unified’; nor to the symphonic model proffered by Arnold Whittall in which ‘an inherent organicism creates stability out of instability’.Footnote 66 Sibelius uses tonality associatively – Scaramouche’s key is D minor, Leilon’s A major and Blondelaine’s A minor. It could be argued, therefore, that the piece is structured around a central tonal polarity between D and A, eventually resolving to D minor. But this implies a more integrated structural process than is present within Scaramouche, and does not accurately represent the organizational principles of the score. Its fragmentary form and lack of ‘symphonic argument’ is Scaramouche’s dramatic strength, as it allows Sibelius to change mood rapidly and to create musical characterizations of the onstage characters. Consequently, instrumentation and timbre are more important elements than the relationship between tonality and form when determining how this score functions.

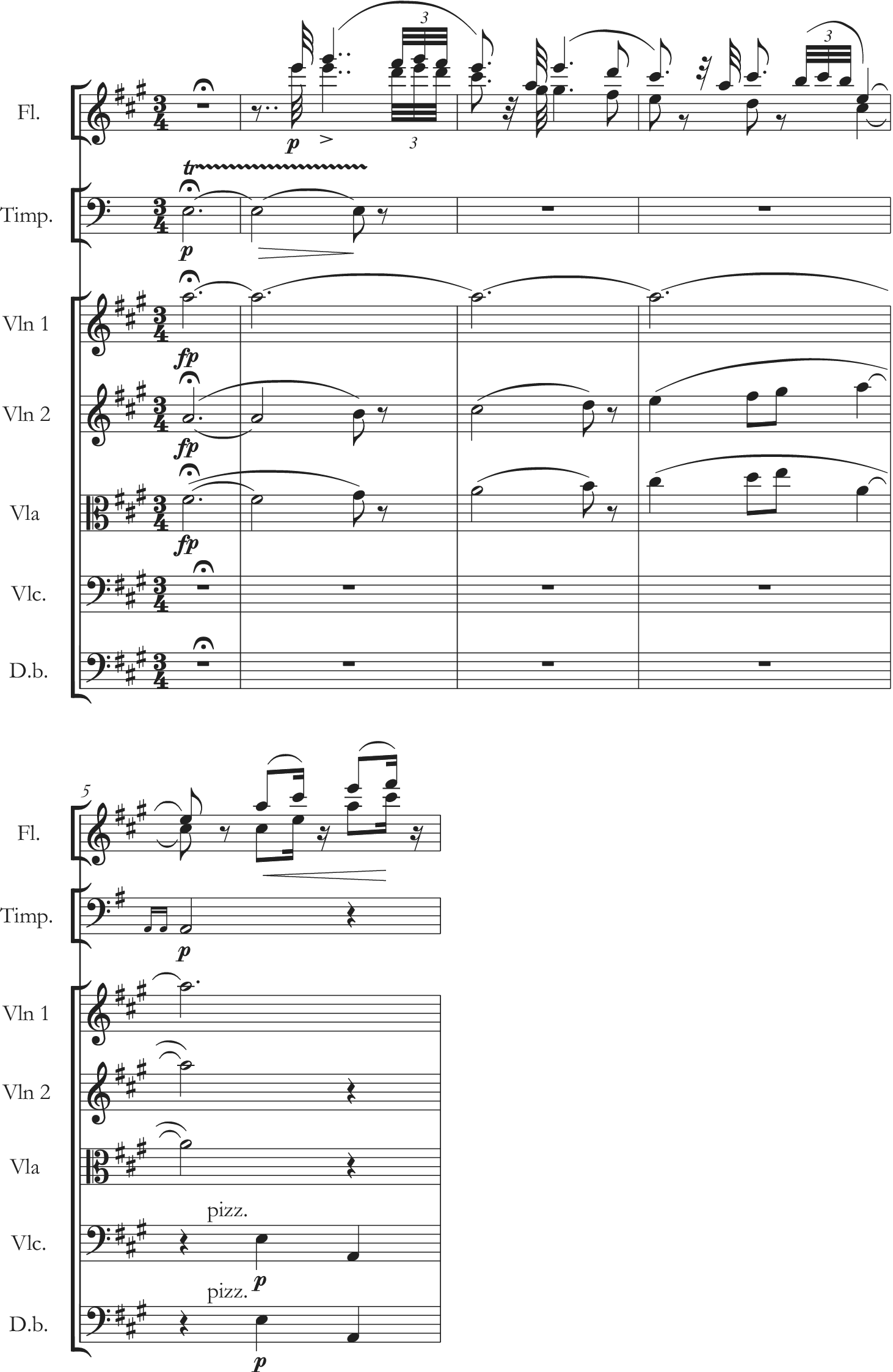

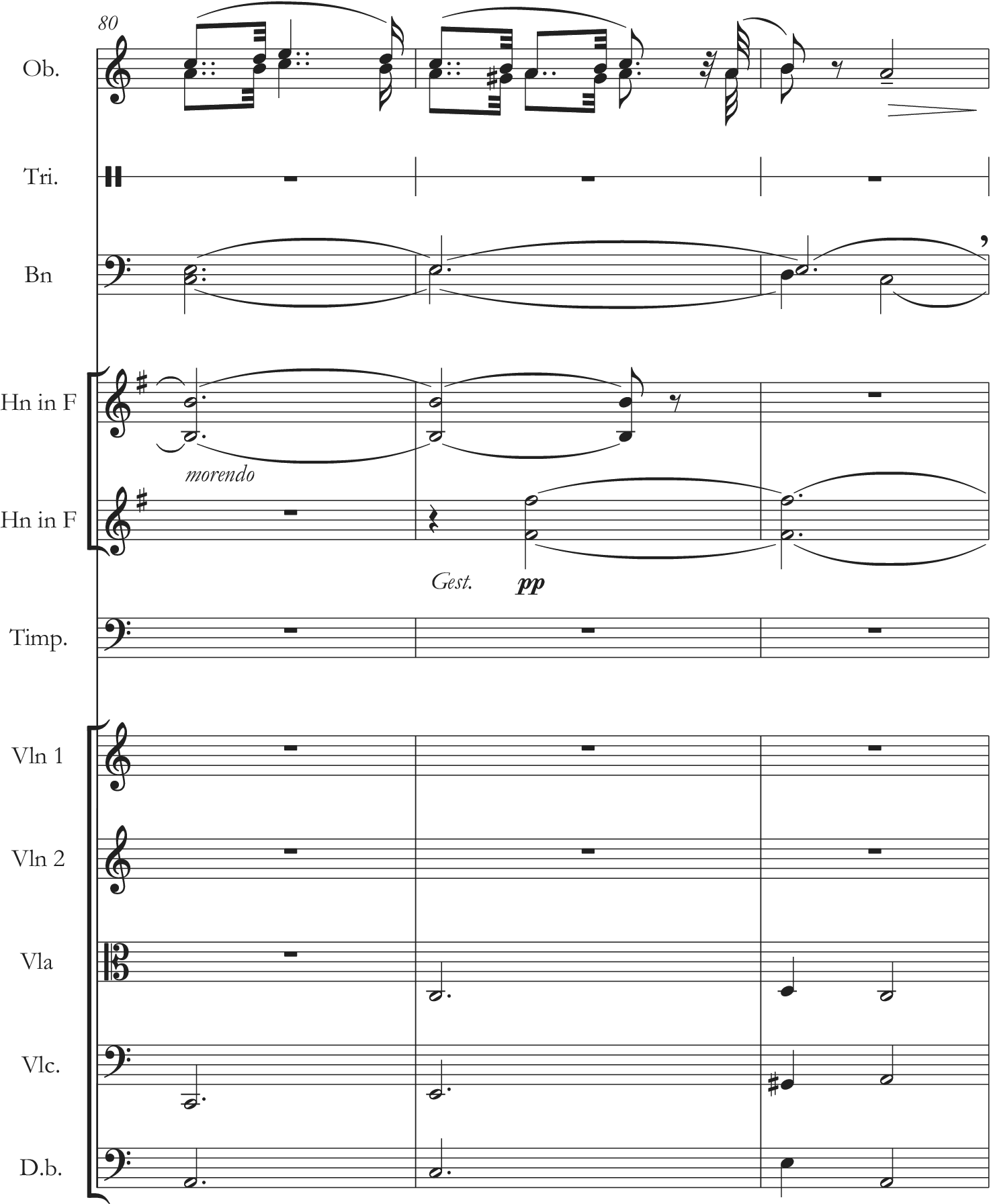

A large quantity of Scaramouche (like the lives of its protagonists) is constructed not around a large-scale tonal polarity or rotational structure, but rather around different dances, juxtaposed to encapsulate different moods and social attitudes, and to symbolize the personalities of and relationships between the three main characters. The pantomime opens with a minuet which both characterizes Leilon and evokes the graceful social circles that Blondelaine and Leilon inhabit (see Example 1a). The music of Blondelaine and Leilon’s social sphere is mundane and repetitive, and seems to function at a deliberately superficial level. Double-dotted minuet rhythms contribute to the impression that this music lacks a solid anchor, rocking back and forth in a manner that would be completely destabilizing in a lower tessitura or at a faster pace, and is sustainable here only thanks to the ethereality of the texture. The orchestration results in a gossamer-thin timbre, providing the musical characterization for the ‘tall, very slender, somewhat decadent’ Leilon who inhabits this sound world.Footnote 67 By contrast, Blondelaine is represented by music in A minor, which is closer to a melancholic chaconne than the opening minuet (see Example 1b). The chaconne’s repetitive harmonic structure, in conjunction with the key and timbre, results in a tonal overdetermination that indicates a sense of harmonic entrapment when compared with the previous section of Leilon’s music, where the reiterated perfect cadences sound obliviously content.

Example 1a Scaramouche, Leilon’s music, bars 1–5.

Example 1b Scaramouche, Blondelaine’s music, bars 76–82.

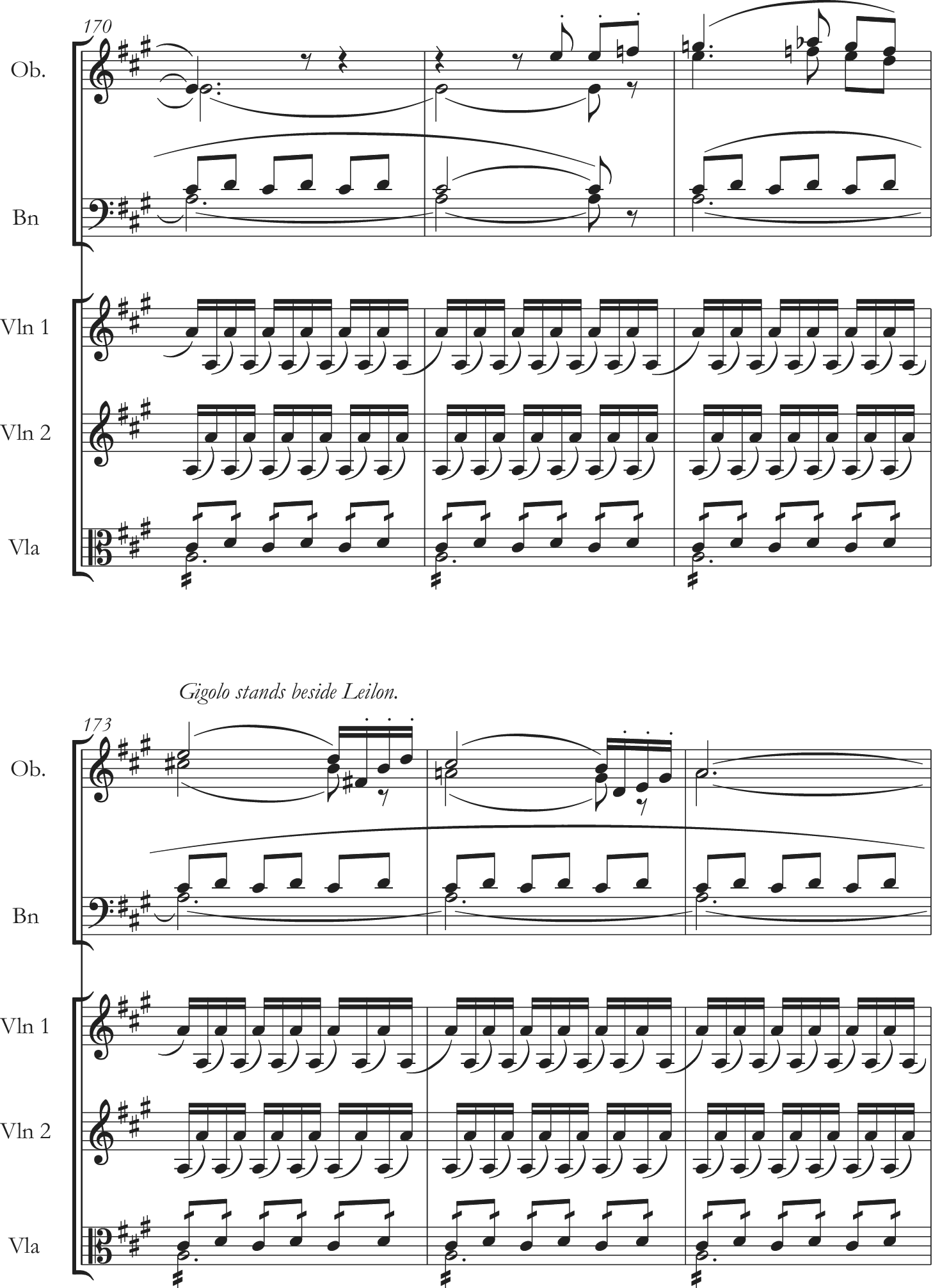

When Leilon calls Blondelaine to dance, he asks the musicians to play a bolero (see Example 1c, p. 439), a dance with sexual connotations. But Blondelaine dances by herself. She is placed into the feminine subject position of the spectacle as she dances on her own for the entertainment of the guests, and Sibelius’s setting is initially lighthearted, effectively tempering the sexual potential of the dance. When Scaramouche plays, however, the music changes entirely (see Example 1d, p. 442). His bolero is the antithesis of Leilon’s dance music. It is densely chromatic, lusciously orchestrated and underpinned by a bass line that provides a foundation for the dance’s intensification. The bolero that Scaramouche plays in the first act is an act of seduction. It is not just music that has to accompany a scene in which Blondelaine is seduced, but it has to provide the very source of her arousal. Sibelius had to compose music that could conceivably drive a woman wild with lust, lose her rational faculties and leave her lover to follow the source of the music. Whether the bolero is interpreted as signifying music’s domination over dance or Blondelaine’s physical attraction to Scaramouche, the dance is Sibelius’s sonic portrait of the dangerous eroticism offered by Scaramouche, encapsulating both irresistible allure and cataclysmic destruction when Blondelaine begins to dance

Example 1c Scaramouche, first bolero, bars 164–76.

.

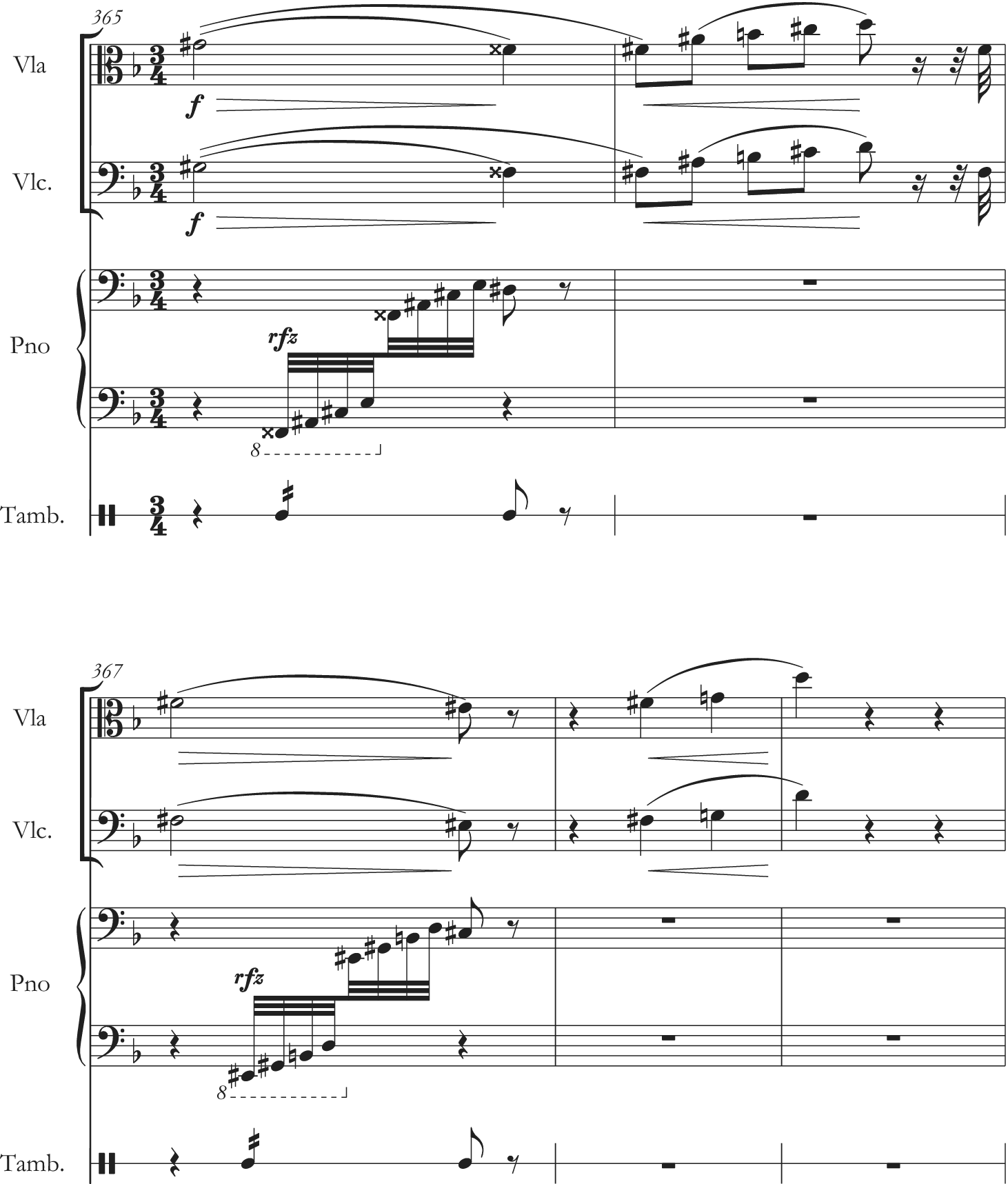

Example 1d Scaramouche, Scaramouche’s bolero, bars 318–35.

The instrumentation of Scaramouche’s bolero is more corporeal than that of the preceding music, using by figure 53 the full forces at Sibelius’s disposal. Included in this is the piano, which provides intermittent arpeggiation from Scaramouche’s entrance in the deepest register of the instrument. The use of the piano’s lowest registers creates a gravelly sonority almost identical to the rumbling piano accompaniment in Sibelius’s earlier song ‘Teodora’ (see Examples 2a and 2b, pp. 446–7). The similarity between the two suggests that Sibelius perhaps associated this sound with the idea of female arousal, the song’s text reading, ‘She draws near with limbs which tremble and quiver from flaming lust’s insatiable fire. Teodora, I want to kiss your lips.’Footnote 68 The protagonist liaises with Teodora, despite the knowledge that, as for Blondelaine and Scaramouche, their union leads to death.

Example 2a Scaramouche, bars 365–9.

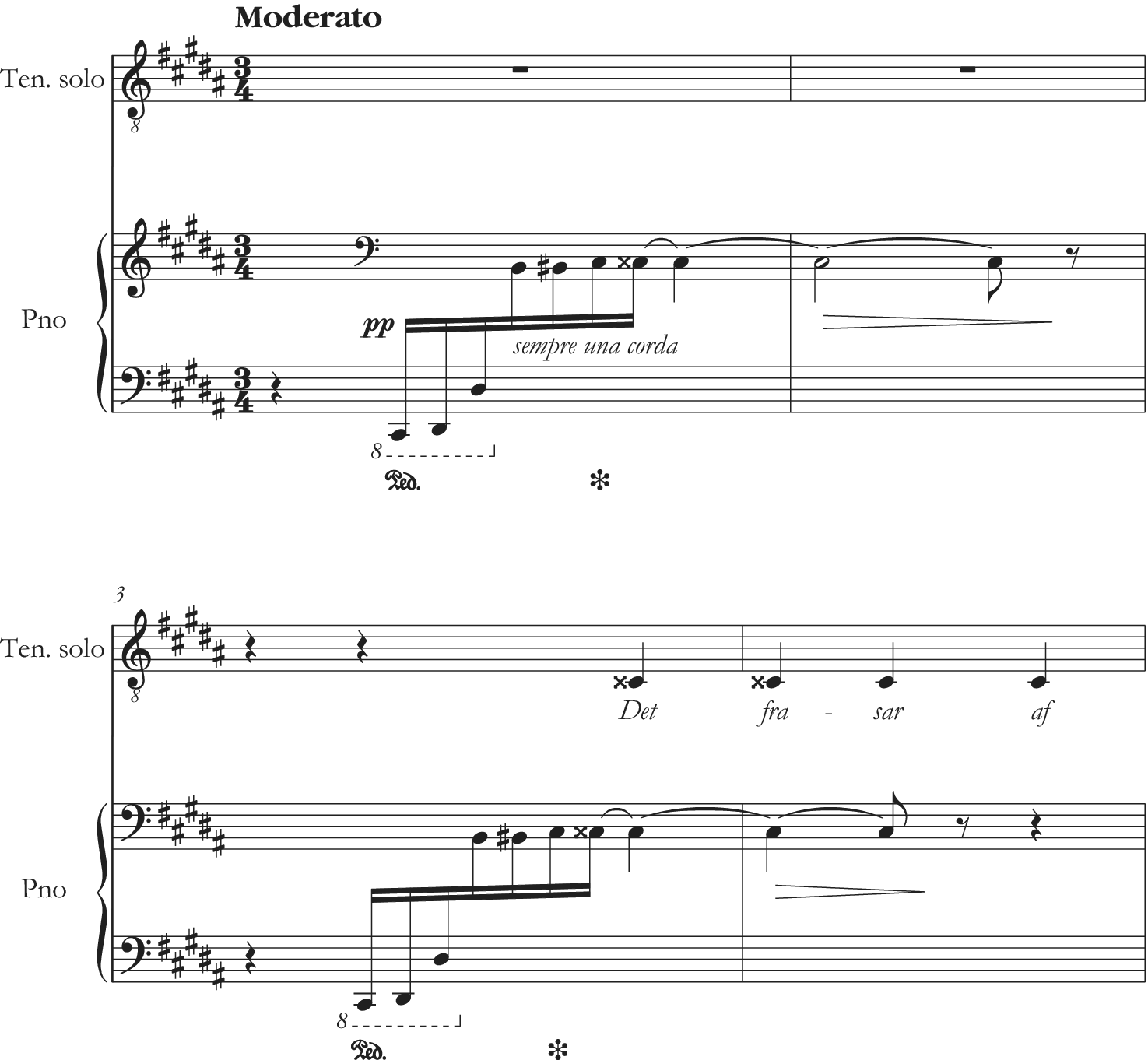

Example 2b ‘Teodora’, bars 1–4.

These dances are knitted together by transitional passages, many of which include diegetic sound effects. After Leilon and Scaramouche finish talking in the first act, for example, Sibelius writes in the musicians’ tuning up as part of the score, using the sound effect structurally as a transition from the passage of dialogue to the start of the bolero. At other moments, Sibelius uses string techniques that exploit the percussive capabilities of the instruments to create non-diegetic acoustic effects. When Scaramouche follows Blondelaine to her home, the double basses play his motif col legno (figure 152), creating a guttural sound beneath the violin and viola ostinato. The melody with which his presence is announced is still the same as when he first appears, but without his viola Scaramouche is threatening and uninviting – there is no seductive allure to the basses’ scraping. In his bolero the basses hold the ensemble together, providing the foundations for the music’s acceleration. Here, they contribute to the passage’s atmosphere of menace, a destabilizing force against the anxiously repetitive upper strings.

In the sections that are not structured by dances, Sibelius moves between relatively self-contained sections with distinct styles of their own. When Leilon is first shown on his own and when Blondelaine returns to him, Sibelius uses a style more familiar from his earlier symphonies. Much of Act 1, scene x, is scored in a way that would not be out of place in a symphony; the solitary cello solo over a pedal recalls the opening of the Fourth Symphony, composed two years before Scaramouche. Within a score so defined by the ability to draw on multiple styles for their affective capacities, Sibelius here seems to invoke his own orchestral idiom topically, using it to signify loneliness, abandonment and isolation.

When Blondelaine finally returns to Leilon, he leaves her temporarily to go and fetch a bottle of wine. As she waits for Leilon to return, Sibelius articulates her nervous apprehension through the string scoring. An ostinato pedal is introduced from figure 141, when Leilon announces he is leaving. From figure 143, the string parts adopt a tremolo figure punctuated by fragments of phrases accompanying Blondelaine, who is becoming visibly more unsettled as she hears noises in the house and believes that she sees Scaramouche in her reflection. Both Morten Kristiansen and Hepokoski highlight the importance of the ‘nervous’ figure to turn-of-the-century conceptions of modern psychology; hysteria was endemic within fin-de-siècle constructions of femininity.Footnote 69 The Viennese critic Hermann Bahr defined the people of die Moderne as consisting entirely of ‘nerves’,Footnote 70 while Arthur Seidl and Max Nordau placed nervousness as the defining personality trait of the modern age, the latter pathologizing the term by associating it with degeneracy.Footnote 71 Modern art that attempted to express the psychological states of these nervous beings earned the associated term Nervenkunst (‘neurotic art’). It would be an exaggeration to describe the whole of Scaramouche as Nervenkunst – even with its dense eroticism and passages of overwrought emotional tension, the stylistic variation within the score prevents a general categorization. But Sibelius’s portrayal of Blondelaine’s anxiousness can accurately be described as Nervenkunst. From here until the close of the pantomime the music lies, as Michael Ewans says of Elektra, ‘on the almost indefinable borderline between decadence and extreme expressionism’,Footnote 72 slowly focusing in on Blondelaine’s psychological processes as she first tries to escape Scaramouche, then comes to terms with murdering him.

Scaramouche relies more heavily on immediate musical effects for its impact than on the large-scale structures described by Hepokoski and Whittall. Consequently, analytical techniques that are more commonly used for film music are more illuminating here than those developed for operas and symphonies. Frank Lehman observes of film music rescored for the concert hall that it encourages a focus ‘on often neglected parameters: gesture, atmosphere, instrumentation, mood, narrative, texture, climax – the musical surface’.Footnote 73 This is directly applicable to Scaramouche. This special emphasis on the sounding surface of the score is perhaps why contemporaneous reviewers felt that Sibelius’s music was so effective. Writing for Aftonbladet, ‘S. S-m’ said that the music was so dramatically suggestive that it seemed as if Sibelius had managed to express musically what ‘is taking place in [the character’s] souls’. The account continues:

It is dramatic music in the eminent sense […] Sibelius’s music has […] a pronounced mimetic character. There is nothing left over of the orchestra-legend’s or rhapsodic-epic’s way of expressing oneself. Here is the dramatist, who shapes human events and unites them in an unbroken symbolic context. […] Harmonically and rhythmically this music is ingeniously creative, alternately self-expressive and gesturally suggestive, and the dramatic suitability of the instrumentation's shimmering colours is surprising. The sound effects conjure forth images.Footnote 74

The author here made a clear distinction between symphonic and dramatic writing, with the latter being identified by descriptive and ‘gesturally suggestive’ writing. They also drew attention to Sibelius’s orchestration and use of sound effects, pointing to how the latter are integrated into the score in such a way that they become a part of both the scenery and the musical narrative. In the same newspaper, another critic under the initials ‘G-r. J.’ used similar language to discuss the pantomime, emphasizing the affective power of the rhythmic and timbral combination.Footnote 75

While attention to the sounding surface is uniform across Sibelius’s theatre music, the stylistic mercuriality of Scaramouche is unique. Nowhere else in Sibelius’s output does he draw on so many styles within the space of a single work. The dramatic demands of Scaramouche seem to have allowed him a degree of compositional freedom that was crucial for his stylistic reorientation during these years, giving him a space to develop methods of transitioning quickly between moods and motifs.

Critical disagreement about the music’s place within the production provides valuable context for situating Sibelius’s stylistic changes between 1909 and 1914, and illuminates something intrinsic to the way in which the music for Scaramouche is written. Within Swedish-language newspapers, symbolism and expressionism were still the artistic movements that reviewers were discussing, even in the early 1920s. And by 1913, part of the ‘progressiveness’ of Sibelius’s music was that it sat somewhere between the two, and was difficult to place within either category. In Scaramouche, Sibelius’s stylistic flexibility was brought to the fore because of the music’s coexistence with other elements of the production, with the set, costumes and choreography all shaping the reviewers’ responses to Sibelius’s score.

Danish critics appear to have been flummoxed by Scaramouche, perhaps unsurprisingly given the speed at which Danish dance was reforming. Under the initials ‘gw’, one settled with saying merely, ‘The symbolism in the little drama is not easy to grasp,’Footnote 76 while the author for Dagens nyheder declared it ‘a beautiful poem’.Footnote 77 Danish critics focused more on Sibelius’s contribution than on the production as a whole, and they were unanimously positive. ‘gw’ offers a representative example, with the statement that Scaramouche ‘consolidates his [Sibelius’s] name as the most original and imaginative composer in the Nordic region’.Footnote 78 This heavy emphasis on Sibelius is probably exacerbated by the fact that one of the critics who wrote most extensively on the performance was Hauch, Sibelius’s long-term admirer and supporter. He took the opportunity to situate Scaramouche within Sibelius’s overall output, pointing out its chronological proximity to the Fourth Symphony and concluding that Sibelius’s theatre music taken as a corpus demonstrates that ‘the topics that have tempted him to [dramatic] musical treatment are those which contain fantasy and mysticism […] should one classify his style, the characterizing words are almost expressionism or symbolism’.Footnote 79

The possibility of hearing Sibelius’s score as both expressionist and symbolist was picked up on by Swedish reviewers, but was woven into larger interpretative arguments that drew on debates about the relationship between dance, music and the body (as discussed above). Pergament made it clear that he interpreted Scaramouche as a symbolist allegory about music’s power over dance:

The action in Scaramouche symbolizes precisely the dance’s dependence on the music. Not its external dependence, which forces dance steps in accordance with the beat and rhythm, but the internal, inescapable, through which the dance’s essence is completely controlled by music’s mysterious power. Both the music and the dance are manifestations of the human psyche and animalistic emotions. But in contrast to the dance […] the music is additionally and above all a cosmic power […] Dance’s dependence on the music has always been obvious.Footnote 80

Consequently, he expressed particular distress over Poulsen and Walbom’s treatment of the pantomime. He found it immensely distasteful, denigrating the focus on Blondelaine’s sexuality for bestowing upon the piece ‘a nauseating odour’.Footnote 81 Similarly, he protested about Poulsen’s tableau that showed Blondelaine and Scaramouche embracing. Again, what troubled Pergament was the physicality of this moment (he added that the ‘nauseating odour’ of the piece was not helped by watching ‘the panting heroine run into the arms of the hunchback’Footnote 82), and the fact that the production granted Blondelaine sexual agency. He expressed special concern about Poulsen’s production portraying Blondelaine as less sexually innocent than he had wanted to believe. Pergament disliked the fact that at her first appearance, ‘One wonders if it is to give the spectator a glimpse of her erotic disposition, [that] she unashamedly swings her hips a little bit, as she walks around in this otherwise so aristocratic company.’Footnote 83 Additionally, he was irked by the fact that the production showed Blondelaine as being drawn to Scaramouche before he began playing. ‘The entire piece is based on the contradiction between the repulsive hunchback and the power in his violin [sic],’ he argued. ‘Personally he is abhorrent, and every thought of a touch between him and Blondelaine is out of the question for her.’Footnote 84 To depict their interaction as more carnally based was, for Pergament, to ‘distort the piece’s symbolic idea – the music as the dance’s – and the dancer’s – master’.Footnote 85

Agne Beijer, however, read the production through an expressionist lens, and castigated Nielsen’s symbolist sets and costumes as ‘naive’, making the scenery ‘taste badly of the fin de siècle’.Footnote 86 His reading, which focused on the personal, physical interaction between Blondelaine, Leilon and Scaramouche, was also favoured by the critics ‘M-e’ and ‘S. S-m’, who were similarly unimpressed by Nielsen’s work. Beijer reserved his admiration for the dancers instead. Having been so critical of the scenery’s fin-de-siècle flavour and damning of the lack of ‘masculinity’ in the text and score, he lauded both Sven Herdenberg and Sven D’Ailly as Leilon and Scaramouche respectively as ‘consistently excellent’, commending Herdenberg’s performance in particular as ‘close to ideal’.Footnote 87 He also praised Ebon Strandin, saying that her depiction of Blondelaine was ‘a truly admirable achievement […] Her Blondelaine found, above all, poignant expression of the darker sides of this genius of dance, for the passion, the anxiety, for the interplay of devotion and defiance.’Footnote 88

Employing Strandin in the lead role immediately signalled the type of production that the Swedish Scaramouche was intended to be – Strandin was considered one of Sweden’s most pioneering dancers, not least through her association with the Ballets Suédois. She had performed leading roles with the company, including alongside Jean Börlin in their 1923 première of Within the Quota, Cole Porter’s ballet about US immigration quotas. By casting Strandin as Blondelaine, Poulsen allied his production with the most modern of Scandinavia’s dance worlds, which no doubt influenced how reviewers approached the production. Indeed, ‘M-e’ and ‘S. S-m’ highlighted Strandin’s plastique movement, the former writing, ‘She gave genuine characteristics in both word and plastik, no false tones or imitative poses.’Footnote 89 ‘M-e’ recognized Walbom’s and Strandin’s involvement as contributing the more expressionist aspects of the production, set against Nielsen’s designs.

In keeping with Beijer’s interpretation, which saw the piece primarily as a psychological depiction of the relationship between the three main characters, particularly focusing on Blondelaine’s attraction to Scaramouche, ‘M-e’ found the most convincing elements to be those which foregrounded the individuality of the pantomime’s characters, arguing, ‘Amidst all the excessive lyricism, Miss Strandin’s secure and well-calculated actions, her gestural precision and self-control seemed liberating.’Footnote 90 The angular precision of the dancers’ movements seem to have provided an antidote to what Beijer saw as an otherwise stultifying production, concealing the physicality of the dancers’ bodies within a haze of visual symbols and seductive orchestral timbres that intimated that the dancers should be sublimated to the demands of the music. For Beijer, Sibelius’s music was at odds with the clarity of Strandin’s dancing, and the orchestration was so ‘irresistibly suggestive’ that it ‘kept you prisoner’, to the extent that Beijer labelled Sibelius’s music a ‘virus’. It is ‘a wild and ecstatic romantic music’, he wrote, ‘brimming with doomed passion, with nagging remorse, but above all […] with the sweetness of lovesick melancholy. The strong scent of all this lyricism becomes unexpectedly anaesthetizing.’Footnote 91 He placed Sibelius’s music in the same category as Nielsen’s designs, hampered by late nineteenth-century symbolism.

Although agreeing that the music for Scaramouche was overtly erotic, ‘M-e’ interpreted the physicality of Sibelius’s score quite differently, observing that ‘Jean Sibelius’s music to Scaramouche’ is ‘in the broadest sense sensual’, continuing: ‘Sibelius’s orchestra simmers and sings with the hot racing pulse of life; one finds here both the innocent, caressing waltz and the delicate spinet’s song as well as the sensual longing, the animalistic brutality and finally the crime’s piercing dissonance in irritating thirds and chromaticisms.’Footnote 92 For this author, Sibelius’s score was the perfect complement to Strandin’s impassioned performance, helping to focus in on the character’s inner psychological processes.

Conclusion

That the reviewers were able to read Sibelius’s music as both expressionist and symbolist attests to the symbiotic relationship between the texts, performers and context at the moment of the performance event. Given that these reviewers were coming to Scaramouche with a framework shaped by contemporaneous debates about dance, not opera or symphonic music, these reviews present an image of Sibelius markedly different from the nature composer promoted in Swedish-language writing on his symphonies, or the Kalevala-inspired national hero invoked in Finnish-language reception. We see this former characterization in Otto Andersson’s article entitled ‘Sibelius and his Symphonies’, for example, in which he declared that Sibelius ‘like nobody before him, has listened in on our beautiful nature’, and that Sibelius’s symphonies are infused with ‘nature’s deep, wondrous mystery [and] the expansive forest’s dreamy silence, disturbed only by the wind’s sighing song in the treetops’.Footnote 93 Consequently, he continued, Sibelius is ‘a Finnish national composer’, and as such, ‘His peculiarities in melody and harmony have been interpreted as authentic national features.’Footnote 94

This kind of rhetoric is entirely absent from the Scaramouche reviews. Not a single review mentioned nature or Finnish national identity. ‘In this work Sibelius has so successfully emancipated himself from unilateral national language,’ wrote ‘G-r. J.’, that ‘the Scaramouche music sounds surprisingly cosmopolitan, and shows links with […] German, French, and Italian styles’.Footnote 95 Here Sibelius was presented as an international figure, and Scaramouche was received as belonging to a compositional corpus that included Felix Mottl’s Pan im Busch (Pan in the Rose Bush, 1900), Béla Bartók’s Der holzgeschnitzte Prinz (The Wooden Prince, 1914–16) and Richard Strauss’s Josephslegende (The Legend of Joseph, 1912–24), as well as other dance pantomimes by Darius Milhaud, Sergei Prokofiev, Maurice Ravel and Igor Stravinsky.Footnote 96 Apart from Richard Strauss, to whom Sibelius is regularly compared,Footnote 97 these composers are now rarely invoked for bearing any similarity to Sibelius.Footnote 98 Currently, as Eric Saylor writes, ‘dramatic works typically receive the least [musicological] recognition or respect’, and this is reflected in the small quantity of writing on Sibelius’s theatrical music relative to the volumes on his symphonic works.Footnote 99 Dedicated scholarly focus on his symphonies and symphonic poems – compositions which invite few parallels with the aforementioned composers – has obscured what Sibelius’s contemporaries heard in his theatrical compositions. The Scaramouche reviews situate Sibelius as an ‘insider’ within, and an active contributor to, a developing international musical culture centred not on opera houses or concert halls, but on the stage.

Attending to Sibelius’s theatrical works gives a richer understanding of his priorities within the musical debates that shaped his world. Scaramouche encapsulates the complexity of Sibelius’s output, which Mäkelä argues ‘compels us to reflect critically on the multidimensional nature of the present’.Footnote 100 From Sibelius’s perspective, composing a balletic pantomime in 1913 placed him within the most ‘progressive’ lines of artistic development. He was always concerned that his music should be ‘progressive’ even if not ‘modern(ist)’, as demonstrated by his comment about his op. 67 sonatinas: ‘They are anything but modern in the sense dictated by the day. But – if you look deeper – such a style has a lot of future.’Footnote 101 Although Sibelius turned away from the musical styles of his central European contemporaries, his involvement with Scaramouche is indicative of how much inspiration he found in the work of those – especially Nordic personalities – who were not composers. His diaries are littered with references to figures such as the Swedish playwright August Strindberg, whom Sibelius greatly admired – he was able to quote from his plays from memory, for example on 22 October 1911, when he wrote, ‘Nature full of poetry. Strindberg believes the earth to be the haunt of judged souls. Perhaps! When music is of heavenly enough origin. Hence its indefinable nature.’Footnote 102 Sibelius used Strindberg’s words as a point of departure, relating them to his thoughts on music.

Sibelius’s engagement with this material suggests that we should take seriously his youthful comment, ‘The other arts fascinate me more than do other people’s music,’Footnote 103 and that when he criticized German composers in 1891, it was for their failure to respond to art and literature, which Sibelius considered to be the most progressive route for music. He wrote that Germans were ‘following old paths too much. For example, they understand nothing about the latest trends in literature and art […] They have no Zola, Ibsen, Tchaikovsky.’Footnote 104 For Sibelius, the progressive came primarily from Scandinavia and Russia, and specifically from their art and literature. Writing theatrical compositions allowed Sibelius the opportunity to work with literature that he both admired and enjoyed. This collapses the ‘insider’/‘outsider’ binary, for Sibelius was both. His theatrical work placed him as a central and interconnected figure with the Nordic cultural milieu, even as he felt himself isolated from musical developments in central Europe.Footnote 105

Many of Sibelius’s Nordic contemporaries can also profitably be viewed from this perspective – their theatrical, balletic and filmic endeavours provide a valuable frame through which to view their concert-hall works. Sibelius’s friend and admirer Wilhelm Stenhammar (1871–1927), for example, expressed a similar ambivalence about Schoenberg’s music, suggesting an anxiety regarding his position in relation to central European musical trends. Compare Sibelius’s comment of 1912 – ‘Arnold Schoenberg’s theories interest me. However, I find him one-sided!’Footnote 106 – with Stenhammar’s 1911 claim: ‘In this time of Arnold Schoenberg I dream of an art far beyond Arnold Schoenberg: clear, happy, and naive.’Footnote 107 Eschewing Schoenberg’s musical path, Stenhammar instead turned to incidental music to hone his compositional idiom, working with other Nordic practitioners within a genre that was less burdened by the traditions associated with the symphony or opera.Footnote 108 In his various writings, the composer Ture Rangström (1884–1947) expressed a more vehement opposition to Schoenberg, placing himself in the position of an ‘outsider’ in relation to the European mainstream. Nonetheless, Rangström viewed himself as an ‘insider’ within the Nordic countries, working with multiple theatre practitioners and writing various stage works, including incidental music to texts by Strindberg.

As well as providing a space for Sibelius to situate himself on an international stage, his theatrical music gave him the opportunity to experiment formally. Mäkelä writes that owing to their differences in formal conception, Sibelius’s symphonic and theatrical scores are ‘self-contradictory if viewed superficially’.Footnote 109 This is seemingly demonstrated by Scaramouche, which is not structured using Sibelius’s ‘architectonic’ approach to symphonic composition. However, Scaramouche’s structure displays Sibelius experimenting with different kinds of musical logic. Creating the narrative form of the pantomime, constructed from evocative vignettes knitted together by sound effects and transitional passages, perhaps helped Sibelius to move towards the ‘content-based forms’ that Hepokoski identifies as being so central to his compositional practice in the late 1910s.Footnote 110 Sibelius’s diary entries of 1912 expressing a renewed commitment to motivically driven forms could apply just as well to Scaramouche as to his symphonic writing. His comments dated 22 and 23 April are representative: he writes first, ‘My musical themes, you are the ones who will settle my destiny’; and the next day, ‘The musical thoughts – the motives, that is – will create the form and determine my way.’Footnote 111

These comments are particularly revealing as they were made in the context of Sibelius creating sketches for an opera, a project he had been considering intermittently since 1909.Footnote 112 His indecision over the opera came to a head in 1912, when on 22 April he wrote that he was ‘At the crossroads!’ and then the following day, ‘Decided against the opera today.’Footnote 113 It was not until October that he finally wrote to the librettist, Georg Boldemann, declaring his final decision to stop working on the opera (he continued to vacillate between opera and symphony throughout May 1912), but his April entries indicate that his preference for motivically based forms was at least part of his decision to move away from operatic composition. Crucially, Scaramouche did not call for Sibelius to set any words to music, a requirement which he appears to have found stifling within a large-scale form. He wrote to Boldemann that he needed the libretto dialogue to be ‘absolutely as brief as possible’, avoiding ‘“names” and other “unpoetic” words’.Footnote 114 Composing a pantomime – even one with some spoken text – evaded this problem altogether, presenting Sibelius with the compromise of a large-scale dramatic form that could be motivically, not linguistically, driven.

Theatre and ballet were crucially important for Nordic composers during this period, because they provided a space in which composers could experiment freely and work collaboratively. Here, they could cultivate a compositional language in a context that answered to different rules from those of the concert hall, and was not defined in opposition to central Europe. For Nordic composers, the theatre was a space where they could be ‘insiders’.