Introduction

Since the publication of Green and Abutalebi's adaptive control hypothesis (ACH), many studies have examined the influence of bilingual language context on cognitive control. Bilinguals switch to different languages based on the demands exerted by the interactional context, and, as a result, different kinds of control mechanism may set in (Green & Abutalebi, Reference Green and Abutalebi2013). Context broadly is understood as the environment with explicit or implicit cues that inform bilinguals about the appropriate languages to be used and the languages to be inhibited. The bilingual mind being cognitively flexible accomplishes this effortlessly in any communicative situation (Bialystok, Reference Bialystok2017). Further, we know from many neuroimaging studies that language control uses the same neural networks as non-linguistic cognitive control (Abutalebi & Green, Reference Abutalebi and Green2007, Reference Abutalebi and Green2008; Abutalebi, Della Rosa, Ding, Weekes, Costa & Green, Reference Abutalebi, Della Rosa, Ding, Weekes, Costa and Green2013; Anderson, Chung-Fat-Yim, Bellana, Luk & Bialystok, Reference Anderson, Chung-Fat-Yim, Bellana, Luk and Bialystok2018; De Baene, Duyck, Brass & Carreiras, Reference De Baene, Duyck, Brass and Carreiras2015; but see Branzi, Calabria, Boscarino & Costa Reference Branzi, Calabria, Boscarino and Costa2016; Calabria, Branzi, Marne, Hernandez & Costa, Reference Calabria, Branzi, Marne, Hernandez and Costa2015; Declerck, Eben & Grainger, Reference Declerck, Eben and Grainger2019).

Bilinguals use executive control mechanisms to modulate greater activation of a certain language and deactivation of another (Bialystok, Craik & Luk, Reference Bialystok, Craik and Luk2012; Blumenfeld & Marian, Reference Blumenfeld and Marian2013; De Groot & Christoffels, Reference De Groot and Christoffels2006). Knowledge of interlocutors and their language dominance or proficiency can assist bilinguals in language control; and so, the extent of language activation depends on the interactional context (Beatty-Martinez, Navarro-Torres, Dussias, Bajo, Guzzardo Tamargo & Kroll, Reference Beatty-Martinez, Navarro-Torres, Dussias, Bajo, Guzzardo Tamargo and Kroll2019; Blanco-Elorrieta & Pylkkanen, Reference Blanco-Elorrieta and Pylkkanen2017; Liu, Timmer, Jiao, Yuan & Wang, Reference Liu, Timmer, Jiao, Yuan and Wang2019; Jevtovic, Dunabeitia & de Bruin, Reference Jevtovic, Dunabeitia and de Bruin2019). It is possible that they pre-emptively choose which language to keep activated more and which one to inhibit for a particular interlocutor. The demands imposed by the contexts, as well as the cues in the environment, influence the goal of the speaker. These, in turn, involve processes implicated in tackling interferences (Green & Abutalebi, Reference Green and Abutalebi2013). Building on this assumption, we hypothesise that upon seeing a certain interlocutor (even if it is not an active conversation) the bilingual brain quickly adopts a control setting for this interlocutor, and this activated control mechanism will be transferred to the task which calls for interference suppression. Evidence for the same comes from studies that have looked at the influence of language contexts on domain-general executive functions in bilingual language users (Wu & Thierry, Reference Wu and Thierry2013; Hartanto & Yang, Reference Hartanto and Yang2016; Ooi, Goh, Sorace & Bak, Reference Ooi, Goh, Sorace and Bak2018). Wu and Thierry (Reference Wu and Thierry2013) reported that implicit contextual cues could influence bilinguals’ interference resolution. In their study on Welsh–English bilinguals, they introduced single-language and mixed-language context by intermittently introducing words in Welsh, English or both (that were irrelevant to the task) while doing the Flanker task. They observed that conflict resolution was better (reduced error rates as well as ERP amplitude) in the mixed-language context. The conflict resolution was improved as a result of the enhancement of the executive system in the mixed-language context indicating the presence of cross-domain interaction between language context and executive function. However, it is not clear if bilinguals adopt different types of control settings with regard to their awareness of the interlocutors’ language profiles i.e., proficiency, fluency or dominance. We tested the hypothesis that bilinguals adopt specific control settings to specific interlocutors depending on their awareness of those interlocutors using a non-linguistic Flanker task. The differences in the demands imposed by the context could be captured on the Flanker task as reduced conflict effects. Bilinguals will use a similar control strategy while performing a Flanker task if this strategy is what they choose for language selection and control for a certain interlocutor who is present there.

Effect of context on linguistic and non-linguistic dimensions

Many studies have shown that bilinguals can take relevant cues from the context (faces, cultural objects, language cues) and activate the relevant lexicons (Grosjean, Reference Grosjean, Grosjean and Li2013; Hartsuiker & Declerck, Reference Hartsuiker and Declerck2009; Jared, Pei Yun Poh & Paivio, Reference Jared, Pei Yun Poh and Paivio2013; Roychoudhuri, Prasad & Mishra, Reference Roychoudhuri, Prasad and Mishra2016). For example, Chinese–English bilinguals tag certain languages to certain faces that they think is congruent with the ethnicity (Li, Yang, Scherf & Li, Reference Li, Yang, Scherf and Li2013); or, when bilinguals find that the language they have to use for a certain interlocutor does not match, they are slower in producing them (Woumans, Martin, Vanden Bulcke, Van Assche, Costa, Hartsuiker & Duyck, Reference Woumans, Martin, Vanden Bulcke, Van Assche, Costa, Hartsuiker and Duyck2015; Molnar, Ibanez-Molina & Carreiras, Reference Molnar, Ibanez-Molina and Carreiras2015). These studies suggest that bilinguals keep track of the language profiles of their interlocutors and adopt a certain control setting for that specific or group of similar interlocutors. These control settings are general purpose in nature (Green, Reference Green1998; Miyake & Friedman, Reference Miyake and Friedman2012) and therefore are transferable to other domains. Although bilinguals tag specific languages to interlocutors, it is not clear how they select languages for interlocutors that are bilinguals and differ in their language profiles. How bilinguals’ language production is influenced by interlocutors of varying proficiencies comes from a study by Kapiley and Mishra (Reference Kapiley and Mishra2018). The study showed that high-L2 proficient Telugu–English bilinguals selected English a significant number of times when they saw a cartoon they perceived as highly proficient in English (that had been introduced earlier). Interestingly, the same bilinguals selected Telugu (L1) a higher number of times, inhibiting their dominant English responses, when they perceived the cartoon to be not so good at English. This data was acquired in the context of a voluntary naming task and choices therein.

Few studies have directly examined the kind of cognitive control settings bilinguals bring in depending on the language requirements of the language contexts using non-linguistic tasks (Hartanto & Yang, Reference Hartanto and Yang2016; Ooi et al., Reference Ooi, Goh, Sorace and Bak2018). For understanding the modulatory role of interactional context on task-switching performance, Hartanto and Yang (Reference Hartanto and Yang2016) categorised 133 bilinguals from University of Singapore into two groups based on a composite score – DLC bilinguals (dual-language context) and SLC bilinguals (single-language context). They hypothesised that a difference in the interactional context – DLC bilinguals speak both languages in a context whereas SLC bilinguals speak one – would lead to differences in switch cost. They observed smaller switch costs for DLC bilinguals, indicating differential effects of interactional contexts on the executive function. In another study, Ooi et al. (Reference Ooi, Goh, Sorace and Bak2018) compared participants from Edinburgh and Singapore on ANT task and the Test of Everyday Attention Elevator task to see the effects of interactional context on attentional control. For the same, they categorised the participants into four different groups – Edinburgh monolinguals (ML), Edinburgh non-switching late bilinguals (ELB), Edinburgh non-switching early bilinguals (EEB) and Singapore switching early bilinguals (SB). They observed that SB had enhanced attentional control indicating that bilinguals who engage in language switching (either dual language/dense code-switching context) were more efficient in resolving conflicts than the others. Evidence for how linguistic environment influences the engagement of cognitive control and language production also comes from the study by Beatty-Martinez et al. (Reference Beatty-Martinez, Navarro-Torres, Dussias, Bajo, Guzzardo Tamargo and Kroll2019). They examined the variation in the engagement of cognitive control in interactional contexts using lexical production tasks (verbal fluency and picture naming) and AX-CPT in three groups (separated, integrated and varied) of highly proficient Spanish-English bilinguals from different language environments. They found that these groups relied differently on the environmental cues to recruit cognitive control which later facilitated their language retrieval.

The aforementioned studies took people from different interactional contexts or categorised the participants into different interactional contexts based on their language use. However, there could have been other confounding variables that are hard to control (such as individuals categorised as being in the single-language context being exposed to the dual-language context in real-life situations) or sometimes researchers have to solely rely on correlations to explain the observed results. Thus, in order to understand the modulatory role of interactional context in the non-linguistic domain and to avoid the abovementioned issues, both types of events – the context as well as the non-linguistic component – have to be considered in the same research design.

Context-induced adaptive control

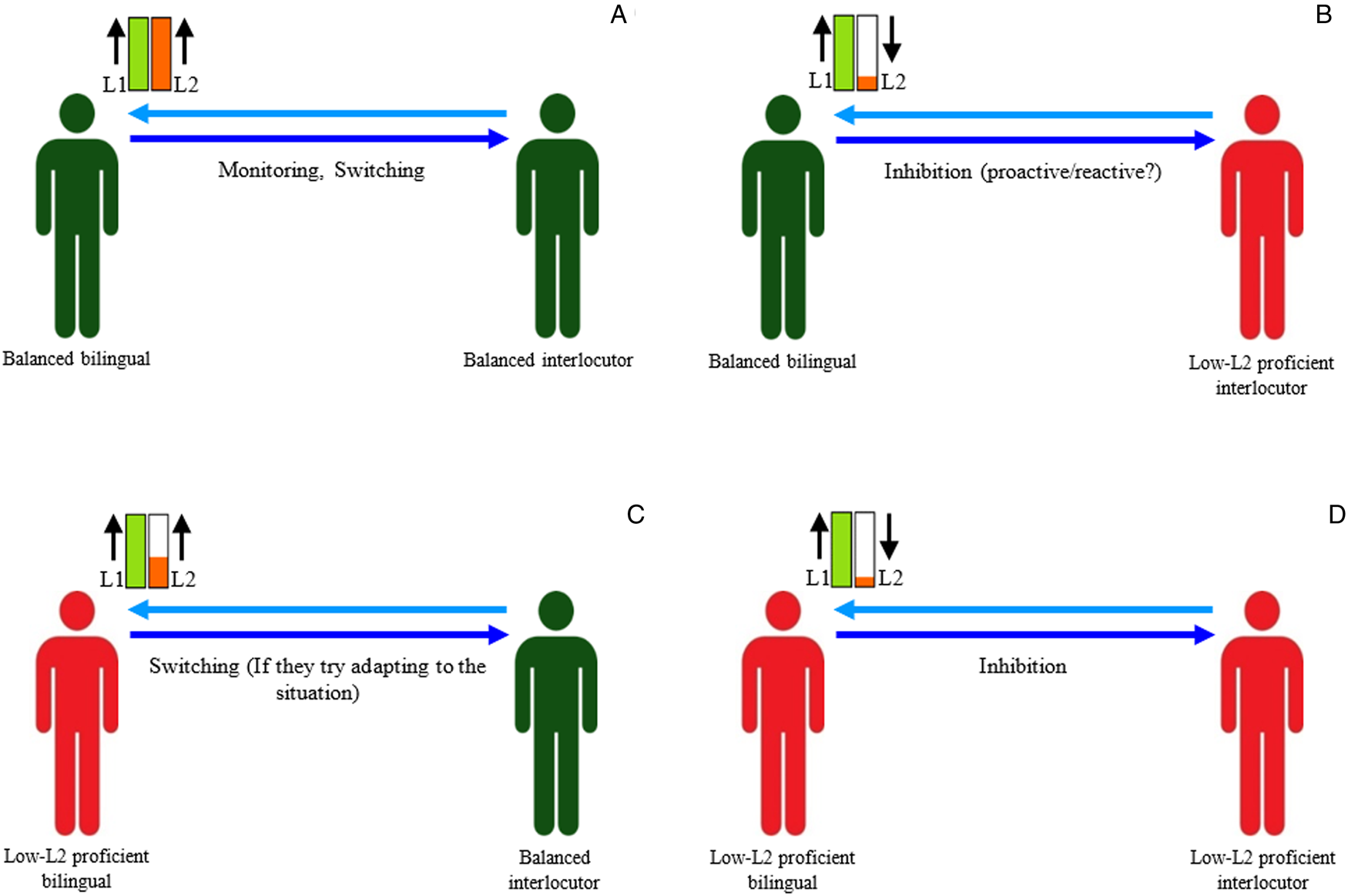

Considering the circumstances of Indian universities, most of the student population are either bilinguals or multilinguals. Depending on their number of years of schooling and training in English, speakers develop different proficiencies in English. Two different bilinguals may have similar proficiency in their first language but very different proficiency in English. Second language proficiency becomes the most defining feature of their bilingualism. Thus, scenarios like these present the possibility to explore how bilinguals of varying second language proficiencies interact with one another. The exact cognitive control mechanisms that they must adopt (monitoring vs inhibition) remain poorly understood. We demonstrate the various types of control settings/mechanisms below through a figure

Fig. 1. Types of control mechanisms involved in different interactional contexts

Fig. 2. Comparison of conflict effect for high-proficient and low-proficient bilinguals in (A) Experiment 1 control condition, (B) Conflict effect in the presence of balanced, unbalanced and neutral interlocutors. For high-L2 proficient bilinguals, the conflict effect was lower in the presence of balanced interlocutor compared to low-L2 proficient bilinguals. (Note: Error bars indicated SE; BD interlocutor – Balanced interlocutor, UBD interlocutor – Unbalanced interlocutor)

Fig. 3. The correlation between conflict effect across different interlocutor conditions and the following variables: years of education in L2 (YoL2), age of acquisition of L2 (AoA_L2), exposure to L1 and L2, L2 naming latency, L2 semantic fluency, L2 self-rated score, L2 vocabulary and composite score on both Experiment 1 and 2. Correlation between conflict effect under different interlocutor conditions (Blue circle represents positive correlation, and red represents negative correlations. The colour intensity and the size of the circle are proportional to the correlation coefficients).

Fig. 4. Comparison of conflict effect for high-L2 proficient and low-L2 proficient bilinguals in (A) Control condition, (B) Conflict effect in the presence of high, low and neutral interlocutors. For high-L2 proficient bilinguals, the conflict effect was lower in the presence of balanced interlocutor compared to low-L2 proficient bilinguals for both monitoring conditions (Note: Error bars indicated SE; BD interlocutor – Balanced interlocutor, UBD interlocutor – Unbalanced interlocutor).

.

Figure 1 depicts situations where bilinguals interact with each other and the type of control mechanisms involved during these interactions. In scenario (a) where two balanced bilinguals are interacting, the speaker is free to engage in both the languages. Thus, one can assume that a balanced bilingual interacting with a balanced interlocutor engages greater monitoring than inhibition of any language. Whereas, in scenario (b), a balanced bilingual is interacting with a low-L2 proficient (in the study, we call them unbalanced) interlocutor. The interlocutor relies more on L1 for the conversation to continue and, so, the speaker engages in inhibition (inhibition of L2). When an unbalanced (low-L2 proficient) bilingual interacts with a balanced interlocutor (scenario c), switching is involved when the former tries to adapt to the situation. An unbalanced bilingual interacting with an unbalanced interlocutor (scenario d) will mostly engage in inhibition (inhibition of L2). Therefore, we assume that language selection with regard to particular interlocutors would require specific types of cognitive control settings. These settings become active whenever a particular interlocutor is present in the environment. It does not matter if there is going to be an active conversation. Bilinguals create preparatory control settings for eventualities for tackling interlocutors, and this can be tapped through a non-linguistic control task.

Current study

In this study, we examine the conjecture that context, induced by cartoon interlocutors, will lead to both linguistic and non-linguistic control settings in the participants. Since bilinguals have to select appropriate language considering the interlocutors’ language proficiency, they will accomplish this using the correct executive control strategies. Therefore, a context's influence on the non-linguistic executive control settings could be measured on a task which calls for the same strategy. Indirectly, this has been the working logic of many studies that have found difference between monolinguals and bilinguals or bilinguals of different language proficiencies on non-linguistic executive control tasks (Bialystok et al., Reference Bialystok, Craik and Luk2012; Costa, Hernandez & Sebastian-Galles, Reference Costa, Hernandez and Sebastian-Galles2008; Costa, Hernandez, Costa-Faidella & Sebastian-Galles, Reference Costa, Hernandez, Costa-Faidella and Sebastian-Galles2009; Prior & MacWhinney, Reference Prior and MacWhinney2010; Singh & Mishra, Reference Singh and Mishra2012, Reference Singh and Mishra2013, Reference Singh and Mishra2015; but see Paap & Greenberg, Reference Paap and Greenberg2013; Paap, Johnson & Sawi, Reference Paap, Johnson and Sawi2014).

Once introduced to any interlocutors, bilinguals prepare themselves with a strategy to tackle them on reappearance. This strategy involves an appropriate choice of lexicon and executive control settings. Importantly, in our study, bilinguals had to keep track of the language dominance/proficiency of the interlocutors and use this knowledge to create control settings when they appeared later during the Flanker task (as well as the refamiliarization phase). Therefore, unlike previous studies (Ooi et al., Reference Ooi, Goh, Sorace and Bak2018) where context was introduced by bringing in bilinguals who lived and worked in different environments, we tested if bilinguals manipulate their top-down control settings using background information of the interlocutors whom they have interacted with. Prior to the main experiment, the participants were introduced to three types of interlocutors – balanced (used L1 and L2 50% of the time), unbalanced (used L1 90% of the time) and neutral interlocutors (language identity unknown). We induced the language identity of these interlocutors through a familiarisation and interaction phase before the main experiment. During the familiarisation phase, they were shown a video of the interlocutors speaking on a topic followed by the interaction phase where participants had to respond to the questions asked by them. It is to be noted that, after these phases, the interlocutors appeared along with the Flanker task and they were task-irrelevant. The participants did not have to interact with them actively and they could ignore them. One might wonder if there is any reason for the participants to be affected by the interlocutors’ presence while performing a non-linguistic task when they understand that the interlocutors were task-irrelevant. We think that the interlocutors’ appearance will influence the participants’ performance on the Flanker task for the following reason. It is well known that bilinguals remain sensitive to their interlocutors and prepare themselves by appropriately controlling the languages that are suitable for them. In our case, the participants have prior acquaintance with the interlocutors through a familiarisation phase and thus have knowledge about their language dominance. This perception will be activated automatically and creates a cognitive control state as soon as they appear during the Flanker task.

We hypothesise that participants will activate both English and Malayalam for those interlocutors perceived as balanced whereas, for an interlocutor perceived to be unbalanced (low-L2 proficient), the participants will activate Malayalam to a higher degree and almost no English. Therefore, balanced interlocutors may demand greater conflict resolution than unbalanced interlocutors. Since both interlocutors are bilinguals and only differ in their second language proficiency in a graded manner, we expect no inhibition but monitoring demands to be higher or lower.

The Flanker task requires conflict resolution, particularly for the incongruent trials. Many have claimed that this is achieved by applying inhibitory control (Fan, McCandliss, Sommer, Raz & Posner, Reference Fan, McCandliss, Sommer, Raz and Posner2002; Hubner & Tobel, Reference Hubner and Tobel2019; Nieuwenhuis, Stins, Posthuma, Polderman, Boomsma & de Geus, Reference Nieuwenhuis, Stins, Posthuma, Polderman, Boomsma and de Geus2006; Verreyt, Woumans, Vandelanotte, Szmalec & Duyck, Reference Verreyt, Woumans, Vandelanotte, Szmalec and Duyck2016). The RTs of the Flanker task have been shown to indicate general executive control advantage (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Hernandez, Costa-Faidella and Sebastian-Galles2009; Hilchey & Klein, Reference Hilchey and Klein2011) and the conflict effect is indicative of cognitive control (Sanders, Hortobagyi, Balasingham, van der Zee & van Heuvelen, Reference Sanders, Hortobagyi, Balasingham, van der Zee and van Heuvelen2018; Tiego, Testa, Bellgrove, Pantelis & Whittle, Reference Tiego, Testa, Bellgrove, Pantelis and Whittle2018; Xie, Ren, Cao & Li, Reference Xie, Ren, Cao and Li2017). We expect that the interlocutors will influence the conflict effects differently and hence, expect lower conflict effects on the Flanker task when participants see the interlocutors that are perceived as balanced compared to unbalanced interlocutors. Many studies have shown that high-proficient bilinguals bring in higher cognitive control when the environmental demands are higher (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Hernandez, Costa-Faidella and Sebastian-Galles2009; Singh & Mishra, Reference Singh and Mishra2013). Thus, in our model, we assume that high-L2 proficient participants will show better conflict resolution in the presence of balanced interlocutors than low-L2 proficient bilinguals.

Experiment 1

Method

Participants

Sixty students (M = 23.36 years, SD = 2.55) from University of Hyderabad were selected for the study. All the participants were native Malayalam (L1) speakers and had acquired English (L2) as a second language (mean age of acquisition of L2 = 7.63 years, SD = 2.67). Object naming task, semantic fluency task, WordORnot and language questionnaire were administered to measure their L2 proficiency. Proficiency in L2 was measured using a composite score (adding the z-scores of L2 proficiency measures (L2 naming latency obtained from object naming task, L2 semantic fluency, WordORnot and L2 self-report score from language questionnaire) and dividing it by square root of the sum of variance and covariance of these values). According to Luo, Luk and Bialystok (Reference Luo, Luk and Bialystok2010), the use of both subjective and objective measures is informative than anyone alone. Following this, we used a cumulative composite score to indicate the language proficiency of bilinguals (McMurray, Samelson, Lee & Tomblin, Reference McMurray, Samelson, Lee and Tomblin2010; Mishra, Padmanabhuni, Bhandari, Viswambaran & Prasad, Reference Mishra, Padmanabhuni, Bhandari, Viswambaran and Prasad2018). Based on the composite score (on L2), participants were categorised into two groups – high-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 22.7 years, SD = 2.60) and low-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 23 years, SD = 3.64) (see Table 1 for participant characteristics) using a median split. All the participants in the study had a normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Written consent was acquired from the participants for their participation. The Institutional Ethics Committee of the University of Hyderabad approved the study.

Table 1. Participant characteristics (Experiment 1)

Note: The groups were compared on the above variables, and * indicates the level of significant difference (** denotes p < 0.001, * denotes p < 0.05)

Language control measures

WordORnot

An online vocabulary test (WordORnot, Centre for Reading Research, Ghent University) was administered to all the participants to test their proficiency in L2. Participants were instructed to judge strings of English letters (100 items were presented) as a “word” or a “non-word”. The total score is the difference between the percentage of correct and incorrect responses. The high-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 58.17%, SD = 10.47) performed significantly better than the low-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 46.37%, SD = 9.91); t(58) = 4.48, p < .001.

Semantic Fluency task

The semantic fluency task was administered both in Malayalam and English. Participants were asked to produce as many words as they could of everyday objects of 4 semantic categories (“birds”, “vegetables”, “animals”, and “fruits”) within 1 minute in both L1 and L2. Following this, the semantic fluency scores (average number of words produced per language) were calculated. The high-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 14.55, SD = 2.21) performed significantly better than the low-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 11.10, SD = 2.37) in L2 category; t(58) = 5.814, p < .001.

Language questionnaire

Participants filled a language background questionnaire with questions on native language, languages known, age of acquisition of L1 and L2, and percentage of time exposed currently to L1, L2 and other languages if any. They also provided their L1 and L2 proficiency self-report score for speaking, understanding and reading ability on a scale of 1 to 10 (with 10 being the highest score). The switching frequency of participants was also measured (see Table 1). To measure the current switching frequency, the question “how often are you in a situation to switch between the languages Malayalam and English?” was asked and rated on a 7-point scale (1-never to 7-very often). The question “when choosing a language to speak with a person who is equally fluent in all your languages, how often would you switch between the languages?” was used to measure the preferred switching frequency on a 7-point rating scale (1-never to 7-very often). The two groups (high-L2 proficient bilinguals: M = 8.51, SD = 0.67; low-L2 proficient bilinguals: M = 7.21, SD = 0.78) differed on the self-rated L2 proficiency score, t(58) = 6.92, p < .001.

Object-naming

A cued object-naming task was administered to obtain an objective measure of proficiency in L1 and L2. One hundred and twenty-one black and white pictures were selected from Snodgrass and Vanderwart (Reference Snodgrass and Vanderwart1980) and Google Images. Eleven Malayalam–English bilinguals selected from University of Hyderabad rated these images on familiarity, frequency of use and name agreement on both languages on a 5-point Likert scale (1-lowest, 5-highest). Based on their ratings, 60 images that had an average score above 3.5 (out of 5) were selected. Before starting the task, participants were familiarised to these 60 objects used in the experiment.

The object-naming stimuli were presented using DMDX (Forster & Forster, Reference Forster and Forster2003) version 5.1.1.3 with directX9.0 on 15.6” hp laptop screen with 1366 x 768-pixel resolution and 60 Hz refresh rate. The trials started with a fixation cross at the centre of the screen for 1000 ms, followed by a red/green coloured square (language cue) for 2000 ms. Participants were asked to respond to the image that followed the square either in L1 or L2. The image disappeared as soon as the voice key was triggered by a response or after 3000 ms. For randomisation, the red square represented English for half of the participants and Malayalam for the remaining half. There were 120 trials in total. The verbal responses were recorded using audacity-win-2.0.5 and errors were coded manually for analysis. Object naming latencies for L1 and L2 on correct trials were calculated after discarding trials with latencies less than 150 ms (4.36%), trials with no (0.75%) or incorrect responses (5.50%). The high-L2 proficient bilinguals (L1: M = 1178.43 ms, SD = 181.94; L2: M = 1063.45 ms, SD = 156.99) had faster naming latencies in both L1 (t = −2.44, p = .01) and L2 (t(58) = -3.78, p < .001) compared to low-L2 proficient bilinguals (L1: M = 1288.64 ms, SD = 166.28; L2: M = 1208.25 ms, SD = 138.59).

Stimuli (Interlocutors)

In the study, three types of interlocutors were used – balanced, unbalanced and neutral interlocutors. A graphic designer sketched the images of six cartoons (three male and three female) to be used as interlocutors in the task. Speech samples (90 seconds duration) for these interlocutors were collected from 8 Malayalam–English bilinguals (four males and four females). The speech samples were on topics like global warming, media, pollution, health, climate change, etc. For the balanced interlocutor, individuals were asked to give speech samples in such a way that they spoke L1 half of the time and L2 for the rest. For the unbalanced interlocutor, the audio sample was recorded in such a way that their speech consisted of L1 90% of the time, whereas L2 was used only 10% of the time. These speech samples were then rated by 11 Malayalam–English bilinguals on a 10-point scale for fluency, cohesiveness and semantics. Based on the ratings, four speech samples were selected. There was no significant difference between the perceived L1 proficiency of balanced and unbalanced interlocutor, t = −0.2828, p = .77. However, there was a significant difference in the perceived L2 proficiency between the selected audio samples, t = 33.73, p = .001.

The selected audios files were then superimposed on the cartoons to make the video of interlocutors. The interlocutors made synchronised lip movements, and eye blinks in the video. Each cartoon was assigned an audio file. On average, each video clip lasted 90 seconds. No video was made for two cartoons that were designated as Neutral interlocutors whose language identity was unknown to the participants.

Procedure

The experiment started with a familiarisation phase followed by an interaction phase, the main task and the re-familiarisation phase.

(a) Familiarisation phase: the participants were familiarised with the balanced and unbalanced interlocutor during this phase. A video clip was shown to them in which cartoon interlocutors spoke on different topics. To avoid any biases, both male and female characters were used for balanced and unbalanced interlocutors.

(b) Interaction phase: following the familiarisation phase, the participants interacted with the interlocutors. The interlocutors asked ten questions, and participants had to respond to each question, and their responses were recorded using Audacity. The balanced interlocutors asked five questions in L1 and five questions in L2, whereas the unbalanced interlocutors asked two questions in L2 and the rest in L1. The order of language used by the interlocutor was random. Participants responded to each question according to their language of choice (96.66% of the participants chose the language of the interlocutor for responding). Following this phase, the participants were asked about interlocutors’ language proficiency and language use. Participants recognised the balanced interlocutors as speaking both the languages equally, whereas they reported that unbalanced interlocutors used more L1 than L2.

The participants then proceeded to do the main task.

Main task: Flanker task

In Flanker task (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Hernandez and Sebastian-Galles2008; Fan et al., Reference Fan, McCandliss, Sommer, Raz and Posner2002), each trial began with a fixation cross for 500 ms. Following this, the target stimuli were presented at the centre of the screen for 1700 ms. Congruent (→→→→→ or ←←←←←) and incongruent (←←→←← or →→←→→) stimuli were used. The participants were requested to respond to the direction of the central arrow; if the central arrow was pointing towards the left, they had to press “A”, and, if it was pointing towards the right, they had to press “L” on the keyboard. The inter-trial interval was 1000 ms. The task was divided into two parts – one without the interlocutors (control experiment – to assess the baseline performance without the presence of interlocutors) and one with the interlocutors (main experiment). The order of presentation of the two parts was counterbalanced across the participants. The control experiment consisted of 160 trials, with 80 congruent and 80 incongruent trials. They were also given 24 practice trials.

For the main experiment, interlocutors (balanced, unbalanced and neutral interlocutor whose language identity was not known) were presented before each flanker stimuli for 1500 ms (Appendix 1). The presentation of the interlocutors was blocked, and the blocks were randomised across participants. The task consisted of 480 trials (160 trials in each condition – 80 congruent and 80 incongruent). After every 80 trials, participants were given a break. Participants were instructed to be as quick and accurate as possible.

(c) Re-familiarisation phase: in the Flanker task, the appearance of the interlocutors was blocked: that is, only one type of interlocutor appeared at a given time. In each block, following 80 trials, participants were given a break. In the balanced and unbalanced interlocutor block, the interlocutors appeared and asked three questions each during the break. The presence of interlocutors during the breaks made sure that the association between the interlocutor and their language identity was reinforced.

Results

Trials were rejected if there were no responses (1.2%), if the trials were above or below two standard deviations of mean RTs of each participant (outliers: 4.5%) and if the response was incorrect (1.1%). Repeated measures ANOVA was performed on filtered data with interlocutor (balanced, unbalanced and neutral) and trial-type (congruent and incongruent) as within-subject factors and group (high-L2 proficient bilinguals and low-L2 proficient bilinguals) as between-subject factors.

RTs were significantly faster in the presence of balanced interlocutor (M = 607.12 ms, SE = 10.16) compared to unbalanced (M = 608.43 ms, SE = 10.38) and neutral interlocutors (M = 622.34 ms, SE = 11.94) showing a main effect of interlocutor, F(2,116) = 6.10, p < .003, η2 = .09 (table 2). Pairwise comparisons show that there was no significant difference between balanced and unbalanced interlocutor (p = .801); however, there was significant difference between balanced and neutral (p = .004) as well as unbalanced and neutral interlocutors (p = .001). Main effect of trial-type was observed as the participants responded significantly faster on congruent trials (M = 587.86 ms, SE = 10.15) compared to incongruent trials (M = 637.40 ms, SE = 11.00), F(1,58) = 313.72, p < .001, η2 = .84. The main effect of group was also significant with high-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 588.05 ms, SE = 14.84) performing faster than low-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 637.21 ms, SE = 14.84), F(1,58) = 5.48, p = .02, η2 = .08.

Table 2. Mean reaction times (RT) and error rates (%) (along with standard deviation in parentheses) for high-proficient and low-proficient bilinguals in Experiment 1. HPB: High-L2 proficient bilinguals, LPB: Low-L2 proficient bilinguals, C: Congruent, IC: Incongruent, BI: Balanced interlocutor, UBI: Unbalanced interlocutor, NI: Neutral interlocutor

There was a significant interaction between interlocutor and trial-type, F(1.83,106.16) = 3.98, p = .02, η2 = .06. Pairwise analysis indicated that the difference between congruent trials and incongruent trials (conflict effect) was lower in the presence of balanced interlocutor (M = 44.39 ms, SE = 2.82) compared to unbalanced (M = 54.64 ms, SE = 3.94) and neutral interlocutor (M = 49.58 ms, SE = 3.62). The pairwise comparison shows that there was a significant difference between balanced and unbalanced interlocutor (p = .007) and marginal difference between balanced and neutral interlocutors (p = .08). No other two-way interactions were significant (F < 1).

A significant three-way interaction between interlocutor, trial-type and group was observed, F(2,116) = 8.28, p < .001, η2 = .12. Costa et al. (Reference Costa, Hernandez, Costa-Faidella and Sebastian-Galles2009) notes that (pg. 138) “…An effect of bilingualism will be indexed either by a main effect of ‘‘Group of Participants” or by an interaction of this variable with the ‘‘Type of flanker” variable, since this interaction would indicate a difference in the magnitude of the conflict effect between the two groups.” Since three-way interactions are complex, they were interpreted by doing a two-way ANOVA on conflict effect (the difference between RT on incongruent and congruent trial) with all the other factors except trial-type following this logic. We found that in the presence of balanced interlocutor, high-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 33.87 ms, SE = 3.99) suffered smaller conflict effect compared to low-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 54.92 ms, SE = 3.99) (p < .001) (refer Figure 2). There was no significant difference between the two groups (high-L2 proficient bilinguals: M = 55.82 ms, SE = 5.57; low-L2 proficient bilinguals: M = 53.46 ms, SE = 5.57 (p = .76)) on conflict effect in the presence of unbalanced as well as neutral interlocutors (high-L2 proficient bilinguals: M = 52.74 ms, SE = 5.13; low-L2 proficient bilinguals: M = 46.43 ms, SE = 5.13 (p = .38)). This gives an indication that the balanced interlocutors might be playing a role in bringing down the conflict, especially in the case of high-L2 proficient bilinguals.

The error analysis (table 2) showed that the main effects of interlocutor, F(2,116) = 0.44, p = .64, η2 = .008 and group, F(1,58) = 0.01, p = .90, η2 < .001 were absent. The main effect of trial-type was significant, F(1,58) = 62.17, p < .001, η2 = .51 indicating that the participants committed more errors on the incongruent rather than the congruent trials. The interaction between interlocutor, trial-type and group was significant, F(2,116) = 5.18, p = .007, η2 = .08; however, pairwise analysis did not reveal any significant interactions that we were interested in. All other interactions were absent (F< 2).

Control experiment

Trials with no response (0.17%) were discarded. Further, 3.8% of the trials above or below two standard deviations of mean RTs of each participant were filtered out as outliers and 1.8% trials as incorrect trials. Repeated measures ANOVA was performed on filtered data with trial-type as within-subject factors and the group as between-subject factor.

Congruency effect was observed on RTs as the participants responded significantly faster on congruent trials (M = 490.61 ms, SE = 8.80) compared to incongruent trials (M = 538.80 ms, SE = 7.78), F(1,58) = 333.79, p < .001, η2 = .85. The interaction between trial-type and group was absent, F(1,58) = 0.18, p = .66, η2 = .003 which reflected on conflict effect as well. It was observed that high-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 494.77 ms, SE = 11.60) performed faster compared to low-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 534.65 ms, SE = 11.60) indicated by the main effect of group, F(1,58) = 5.90, p = .01, η2 = .09.

The error analysis indicated that a main effect of trial-type was present, F(1,58) = 30.20, p < .001, η2 = .34. The main effect of group, F(1,58) = 2.07, p = .15, η2 = .03 and the interaction between trial-type and group (F < 1) was absent.

Correlations

A correlation between L2 measures and task performance (figure 3) was performed. Conflict effect in the presence of balanced interlocutor was negatively correlated with years of education in L2 (r = −.305, p = .01), composite score (measure of proficiency; r = −.275, p = .03), and percentage of exposure to L2 (r = −.27, p = .03) and positively correlated with age of acquisition of L2 (r = .419, p < .001).

Discussion

From experiment 1, it is clear that participants’ performance on Flanker task was influenced by the presence of interlocutors of different L2 dominance. When the interlocutors were perceived as balanced, the high-L2 proficient bilinguals had faster RTs and smaller conflict effect. Consistent with previous findings with such tasks and similar bilinguals (Singh & Mishra, Reference Singh and Mishra2012, Reference Singh and Mishra2013), the high-L2 proficient bilinguals were, in general, faster on the task. This may suggest that highly proficient second-language speakers entertained less conflict with interlocutors perceived as having superior ability in the second language. On the other hand, low-L2 proficient bilinguals did not show any such distinctive adaptation to interlocutors who differed in their L2 dominance. Therefore, these results suggest that the mere presence of an interlocutor and participants’ knowledge of language dominance triggered distinctive control mechanisms. This mechanism influenced performance on the Flanker task. One can say that this is an example of cognitive control mechanism adopted for an interlocutor which is also influencing other action control systems.

Experiment 2

In experiment 1, the distribution of congruent and incongruent trials in the Flanker task created a high monitoring situation. Being equal in numbers, participants could not predict which trial may come next, and they operated in a higher monitoring set up. Interestingly, even when this was the demand of the Flanker task, the interlocutors that appeared passively influenced performance. It is possible that the high-L2 proficient bilinguals brought in greater control resources, and this helped them deal with the interlocutors.

Past studies have shown that both high and low-L2 proficient bilinguals deal with different monitoring demands differently (Singh & Mishra, Reference Singh and Mishra2013); the former shows less conflict effect and faster RTs on the Flanker task when monitoring demands are high (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Hernandez, Costa-Faidella and Sebastian-Galles2009). This has been taken as evidence that high-L2 proficient bilinguals generally bring in greater cognitive control to deal with a situation that calls for greater monitoring. How does the presence of different interlocutors modulate this? From Experiment 1, we can say that high-L2 proficient bilinguals entertained lower conflict (observed as lower conflict effect) in the presence of balanced interlocutors but not for the unbalanced interlocutors. We wondered if the influence of the interlocutors will stay even when monitoring demands on Flanker task are low. Monitoring demand was created by adjusting the relative percentage of congruent and incongruent trials. When a particular type of trial is overwhelming in numbers, then participants adopt a more relaxing strategy. That is, during the low monitoring condition, the participants adopt a more relaxing strategy which is reflected in a larger conflict effect in comparison to high monitoring condition. However, we speculated that the presence of interlocutors will affect performance of participants even in the low monitoring condition. Thus, we expected that adaptation to interlocutors will be present even in the low monitoring condition; but there will be a magnitude difference compared to the high monitoring condition.

Methods

Participants

Eighty-eight students (M = 23.36 years, SD = 2.55) from University of Hyderabad were selected for the study (for participant characteristics, see table 3). All the participants were native Malayalam speakers and had acquired English as a second language (mean age of acquisition of L2 = 7.63 years, SD = 2.67). As carried out in Experiment 1, a composite score was calculated and based on it, participants were categorised into two groups – high-L2 proficient (n = 48; M = 22.95 years, SD = 2.59) and low-L2 proficient (n = 40; M = 23.9 years, SD = 2.78).

Table 3. Participant characteristics (Experiment 2)

(** denotes p < 0.001, * denotes p < 0.05)

Procedure

The procedure was similar to Experiment 1. Following the familiarisation phase, the participants interacted with the interlocutors, and they went on to do the main Flanker task.

Flanker task

The design was similar to Experiment 1 with one exception. There were two monitoring conditions in the Flanker task – high and low. In the high monitoring condition, 50% of the trials were congruent (48 congruent and 48 incongruent trials). The low monitoring condition was divided into two: in low monitoring condition 1 (92% congruent trials), 88 trials were congruent and 8 trials were incongruent; in low monitoring condition 2 (92% incongruent trials), 88 trials were incongruent and 8 trials were congruent. The low monitoring conditions were counterbalanced across the participants. The interlocutors were blocked, and each interlocutor was presented in both high and low monitoring conditions. Participants were instructed to be as quick and accurate as possible. The interlocutor condition consisted of 576 trials, and breaks were given following every 96th trial. The re-familiarisation phase was introduced between the breaks.

A control experiment without the presence of interlocutors was also administered. Similar to the main task, control task also had two monitoring conditions – high and low.

Results

Trials with no response (1.1%), trials above or below two standard deviations of mean RTs of each participant (outliers: 4.4%) and incorrect trials (1.2%) were removed. Repeated measures ANOVA was performed with interlocutor (balanced, unbalanced and neutral), monitoring (high and low) and trial-type (congruent and incongruent) as within-subject factors and group (high-proficient bilinguals and low-proficient bilinguals) as between-subject factor.

RTs were significantly faster in the presence of balanced interlocutor (M = 609.60 ms, SE = 7.47) compared to neutral (M = 622.29 ms, SE = 7.53) and unbalanced interlocutors (M = 632.00 ms, SE = 7.31), F(1.77,152.77) = 11.11, p < .001, η2 = .11 (table 4). Pairwise comparisons showed that there was a significant difference between balanced and unbalanced interlocutor (p < .001), balanced and neutral interlocutor (p = .01) and unbalanced and neutral interlocutor (p = .01). Main effect of trial-type was observed on RTs as participants responded faster on congruent trials (M = 589.83 ms, SE = 6.66) compared to incongruent trials (M = 652.76 ms, SE = 7.48), F(1,86) = 420.90, p < .001, η2 = .83. The main effect of monitoring condition was also significant, F(1,86) = 6.40, p = .01, η2 = .06. The results also showed that both the groups differed significantly in their performances with high-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 598.41 ms, SE = 9.32) performing faster than low-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 644.18 ms, SE = 10.21), F(1,86) = 10.93, p = .001, η2 = .11.

Table 4. Mean reaction times (RT) and error rates (%) (along with standard deviation in parentheses) for high-proficient and low-proficient bilinguals in Experiment 2. HPB: High-L2 proficient bilinguals, LPB: Low-L2 proficient bilinguals, C: Congruent, IC: Incongruent, BI: Balanced interlocutor, UBI: Unbalanced interlocutor, NI: Neutral interlocutor, HM: High-monitoring condition, LM: Low monitoring condition

There was a significant interaction between interlocutor and group, F(2,172) = 5.54, p = .005, η2 = .06. Pairwise comparison revealed that, for high-L2 proficient bilinguals, RTs were faster in the presence of balanced interlocutor and slowest in the presence of unbalanced interlocutors with a significant difference between balanced and unbalanced interlocutor (p < .001), balanced and neutral interlocutor (p = .001), unbalanced and neutral interlocutor (p = .01); whereas in the case of low-L2 proficient bilinguals, there was no significant difference (p values .34, .89, .26 respectively). A significant interaction between interlocutor and trial-type was observed, F(1.92,165.42) = 20.82, p < .001, η2 = .19, indicating that the difference between congruent trials and incongruent trials (conflict effect) was lower in the presence of balanced (M = 47.12 ms, SE = 3.99) compared to unbalanced (M = 73.08 ms, SE = 3.80; p < .001) and neutral interlocutor (M = 68.55 ms, SE = 4.03; p < .001); however, there was no difference between unbalanced and neutral interlocutors (p = .32). There was an interaction between interlocutor and monitoring, F(2,172) = 5.64, p = .004, η2= .06. In the high monitoring condition, there was a significant difference between balanced (M = 32.73 ms, SE = 3.15) and unbalanced (M = 57.39 ms, SE = 3.58) interlocutor (p < .001); and balanced and neutral (M = 53.49 ms, SE = 3.27) interlocutor (p < .001); whereas in the low monitoring condition, significant difference was between balanced (M = 61.51 ms, SE = 6.53) and unbalanced (M = 88.77 ms, SE = 6.09) interlocutor (p = .001); balanced and neutral (M = 83.61 ms, SE = 6.07) interlocutor (p < .001) and unbalanced and neutral interlocutor (p = .001).

The interaction between monitoring and trial-type was significant, F(1,86) = 51.61, p < .001, η2 = .37 indicating that participants had lower conflict effect in the presence of high monitoring (M = 47.87 ms, SE = 2.39) compared to low monitoring condition (M = 77.97 ms, SE = 4.67). Also, high-L2 proficient bilinguals had smaller conflict effect in both high (M = 46.55 ms, SE = 3.23) and low monitoring (M = 85.87 ms, SE = 6.30) conditions compared to low-L2 proficient bilinguals (high-monitoring: M = 49.20 ms, SE = 3.54; low-monitoring: M = 70.06 ms, SE = 6.90) indicated by an interaction between monitoring and group, F(1,86) = 5.63, p = .02, η2 = .06.

Significant three-way interaction was observed between interlocutor, trial-type and group, F(2,172) = 39.47, p < .001, η2 = .31 showing that in the presence of balanced interlocutor, high-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 32.36 ms, SE = 5.38) had smaller conflict effect compared to low-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 61.88 ms, SE = 5.90; p < .001). Significant three-way interaction between monitoring, trial-type and group was also observed, F(1,86) = 4.85, p = .03, η2 = .05 with both groups of participants resolving conflicts in the high monitoring compared to the low monitoring condition. Finally, a four-way interaction between interlocutor, monitoring, trial-type and group was also observed, F(2,172) = 8.24, p < .001, η2 = .08. Post hoc analysis showed that the difference between congruent and incongruent trials (conflict effect) was reduced for high monitoring compared to low monitoring condition for all interlocutor types. However, for high-L2 proficient bilinguals, conflict effect was reduced drastically in the presence of balanced interlocutors (high-monitoring: M = 18.36 ms, SE = 4.25; low-monitoring: M = 46.36 ms; SE = 8.80) as opposed to unbalanced interlocutors (high-monitoring: M = 66.89 ms, SE = 4.83, low-monitoring: M = 125.84 ms, SE = 8.22) and neutral interlocutors (high-monitoring: M = 54.39 ms, SE = 4.42; low-monitoring: M = 85.41 ms, SE = 8.19) compared to the low-L2 proficient bilinguals indicating that balanced interlocutors might be playing a role in bringing down the conflict in the former (figure 4). For low-L2 proficient bilinguals, there was no significant difference in the conflict effect between the interlocutors in the high monitoring condition; however, in the low monitoring condition, they had reduced conflict effect (M = 51.71 ms, SE = 9.00) in the presence of an unbalanced interlocutor.

The error analysis showed that only the main effects of monitoring (F(1,86) = 5.10, p = .02, η2 = .05), trial-type (F(1,86) = 78.12, p < .001, η2 = .47) and interaction between monitoring and trial-type (F(1,86) = 6.61, p = .01, η2 = .07) were significant, indicating that participants made fewer errors on congruent than incongruent trials; also errors were fewer in high monitoring compared to low monitoring condition. The main effect of interlocutor, group and all other interactions were absent.

Control experiment

Trials with no response (0.21%) were discarded. Further, 4% of the trials above or below two standard deviations of mean RTs of each participant and incorrect trials (1.1%) were discarded. Repeated measures ANOVA was performed with monitoring (high and low) and trial-type (congruent and incongruent) as within-subject factors and the group (high and low-L2 proficient) as between-subject factor.

RTs were faster in high monitoring condition (M = 534.96 ms, SE = 5.94) compared to low monitoring condition (M = 546.93 ms, SE = 6.91), F(1,86) = 7.96, p = .006, η2 = .08. Main effect of trial-type was observed on RTs as the participants responded significantly faster on congruent (M = 513.89 ms, SE = 6.07) compared to incongruent trials (M = 567.99, SE = 6.57), F(1,86) = 245.62, p < .001, η2 = .74. The high-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 528.78 ms, SE = 8.21) performed better compared to low-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 553.11 ms, SE = 8.99), F(1,86) = 3.98, p = .04, η2 = .04.

The interaction between monitoring and trial-type was significant, F(1,86) = 42.27, p < .001, η2 = .33. Participants had reduced conflict effect in high monitoring (M = 37.91 ms, SE = 3.33) compared to low monitoring condition (M = 70.28 ms, SE = 5.00). They were able to perform better in the presence of conflicting information indicating better monitoring abilities. There was a significant interaction between trial-type and group, F(1,86) = 6.90, p = .01, η2 = .07 indicating that high-L2 proficient bilinguals had smaller conflict effect (M = 45.03 ms, SE = 4.65) compared to low-L2 proficient bilinguals (M = 63.17 ms, SE = 5.09). The interaction between monitoring and group was absent, F(1, 86) = 2.47, p = .11, η2 = .02. All other interactions were not significant.

In the error analysis, only the main effect of trial-type was significant, F(1,86) = 9.77, p = .002, η2 = .10. All the other main effects and interactions were not significant (F < 3). We also carried out the sequential congruency analysis to see the presence of conflict adaptation and the results are included in the supplementary file (Supplementary Materials).

Correlations

A correlation between L2 measures and task performance (see figure 3) was performed. Conflict effect in the presence of a balanced interlocutor was negatively correlated with composite score (high-monitoring condition: r = −.295, p = .005; low-monitoring condition: r = −.256, p = .01), and percentage of exposure to L2 (high-monitoring condition: r = −.251, p = .018; low-monitoring condition: r = −.264, p = .012).

Discussion

We observed similar patterns of results in both Experiment 1 and 2; participants’ performance on the task varied differently in the presence of interlocutors with varying L2-dominance. Thus, the data support the observation that bilinguals use their knowledge of interlocutors’ language profile to adapt to certain interlocutors and that it can be captured through a non-linguistic task. High-L2 proficient bilinguals were faster in the presence of balanced interlocutors in both high and low monitoring conditions. This indicates that they encountered less conflict with those interlocutors who used both the languages equally. For low-L2 proficient bilinguals, we observed that the conflict effect was reduced in the presence of an unbalanced bilingual in the low monitoring condition. However, for them, there was no effect of interlocutors on conflict effect in the high monitoring condition (no significant difference was observed between the conflict effects in the presence of different interlocutors).

General discussion

The current study explored whether bilinguals are sensitive towards their potential interlocutors' language abilities in different interactional contexts and if this reflects in their dynamic cognitive control settings. Bilingual participants were introduced to different interlocutors before they did a Flanker task. We hypothesised that when high-L2 proficient bilingual speakers interact or encounter an interlocutor with similar second language ability, they will bring in higher monitoring compared to when the interlocutor is less proficient in the second language; since, in the former interactional context, the bilingual speaker has to monitor constantly the language use and switch between them when necessary. Thus, the requirement of cognitive control is dependent on the language profile of the interlocutor. We hypothesised that this should influence their performance on the Flanker task that measures conflict resolution and conflict effect. If bilinguals adopt a certain cognitive strategy for certain interlocutors, then this control setting should show up in any non-linguistic cognitive control task they do (Green & Abutalebi, Reference Green and Abutalebi2013; Hartanto & Yang, Reference Hartanto and Yang2016; Ooi et al., Reference Ooi, Goh, Sorace and Bak2018; Beatty-Martinez et al., Reference Beatty-Martinez, Navarro-Torres, Dussias, Bajo, Guzzardo Tamargo and Kroll2019). We found that the overall RTs were significantly faster (also, reduced conflict effect) in the presence of balanced interlocutors for high-L2 proficient bilinguals. Low-L2 proficient bilinguals may be less flexible in processing both languages at the same time, and this might have affected their control process (Kar, Khare & Dash, Reference Kar, Khare, Dash, Mishra and Srinivasan2011) which in turn reflected in the RTs on the Flanker task. The results suggest that high-L2 proficient participants brought in higher conflict resolution when the environment was demanding. However, this effect was not seen when they did the Flanker task in the presence of unbalanced interlocutors. Cognitively demanding situations require better control to resolve conflicts, and high-L2 proficient bilinguals tend to perform better than low-L2 proficient bilinguals in such situations given their superior executive control (Bialystok et al., Reference Bialystok, Craik and Luk2012; Singh & Mishra, Reference Singh and Mishra2013). Also, the cross-domain interaction between interactional context and executive control plays a role in the enhancement of executive system (Wu & Thierry, Reference Wu and Thierry2013) which in turn must have led high-L2 proficient bilinguals to a better performance in the presence of balanced interlocutors. They showed that not only the explicit task but also the irrelevant and implicit contextual cues modulate executive function.

The balanced interlocutors were introduced in such a way that they alternated between L1 and L2 frequently which led the participants to keep active both their language systems in their presence assuming that they prepared for a conversation with these interlocutors eventually. Also, during the instruction, participants were told that the interlocutors would appear in between the task and might interact with them (re-familiarisation phase), which might have also led the participants to prepare for it. Though the presentation of the interlocutors was task-irrelevant, they simulated the real-life conditions wherein the participants are required to switch smoothly between the two languages. Thus, the expectations, as well as the sensitivity towards these interlocutors, made the situation more challenging (higher monitoring demands) which shifted the executive system to an enhanced level and this was reflected in the conflict resolution task (for more details on the influence of task-irrelevant inanimate objects on a non-linguistic task, see Dolk, Hommel, Prinz & Liepelt, Reference Dolk, Hommel, Prinz and Liepelt2013). Two control processes – conflict monitoring and interference suppression – are essential in the presence of/while interacting with balanced interlocutors as they switch between both the languages. However, the demands placed by unbalanced interlocutors on the language control processes are low as they rarely switch between the languages. For neutral interlocutors, the demands on the monitoring system are high compared to unbalanced interlocutors because the language identity of the former is not known and it is possible that they might use any of the languages, and hence the participants anticipate this and monitor for the cues. These expectations that participants made about their interlocutors reflected in the Flanker task performance. We observed that high-L2 proficient bilinguals were faster in responding to the task in the presence of balanced interlocutors followed by neutral interlocutors; they were the slowest in the presence of low-L2 proficient interlocutors.

Our findings also show that L2 exposure was a significant predictor of conflict effect in the presence of a balanced interlocutor, i.e., as L2 exposure increases, conflict effect decreases. This is in line with the previous studies that show interactional contexts (based on L1 and L2 usage and switching) modulate executive control abilities differently (Borsa, Perani, Della Rosa, Videsott, Guidi, Weekes, Franceschini & Abutalebi, Reference Borsa, Perani, Della Rosa, Videsott, Guidi, Weekes, Franceschini and Abutalebi2018; Hartanto & Yang, Reference Hartanto and Yang2016; Ooi et al., Reference Ooi, Goh, Sorace and Bak2018). Depending on the interactional context and language switching behaviour, the executive control requirements of bilinguals vary (Green & Abutalebi, Reference Green and Abutalebi2013). A thorough look at the socio-linguistic environment in which the participants are situated is essential in explaining the results obtained. The participants in our study were taken from an environment where the lingua franca is English. The high-L2 proficient bilinguals reported more exposure to L2 compared to L1, which might have played a role in adapting to interlocutors of different types. This is also consistent with the findings that high-L2 proficient and balanced bilinguals can modulate their attention in different monitoring contexts and that they have better interference control and conflict resolution abilities (Carlson & Meltzoff, Reference Carlson and Meltzoff2008; Singh & Mishra, Reference Singh and Mishra2013, Reference Singh and Mishra2015; Tao, Marzecova, Taft, Asanowicz & Wodniecka, Reference Tao, Marzecova, Taft, Asanowicz and Wodniecka2011). Bilingual experience affects the inhibitory control and monitoring mechanisms in such a way that the experience of using a second language in the environment demands superior monitoring and exercise of language control to maintain a conversation which ultimately benefits the executive control. We also observed that composite score – which was treated as a measure of proficiency – correlated negatively with the conflict effect in the presence of a balanced interlocutor, indicating that the proficient bilinguals show an advantage in conflict resolution in highly demanding interactional contexts (Singh & Mishra, Reference Singh and Mishra2013; Hartanto & Yang, Reference Hartanto and Yang2016; Ooi et al., Reference Ooi, Goh, Sorace and Bak2018; Ye, Mo & Wu, Reference Ye, Mo and Wu2017) and that they adapt better to their interlocutors.

Interestingly, we observed that for high-L2 proficient bilinguals, the conflict effect was reduced in the presence of a balanced interlocutor in both high monitoring and low monitoring condition (Experiment 2). Though they had slower responses in the low monitoring condition, conflict effect tended to have similar patterns in both monitoring conditions in the presence of interlocutors. It is possible that the presence of balanced interlocutors imposed high demands on the conflict monitoring and resolution resources of the participants even in the low monitoring conditions, which in turn reflected in the performance. It is also interesting to note here that, in the case of low-L2 proficient bilinguals, the pattern of conflict effect under different monitoring conditions was not similar. While there was no difference in the conflict effect (in the presence of different interlocutors) in the high monitoring condition, we observed a difference in the low monitoring condition. These bilinguals tended to have reduced conflict effect in the presence of unbalanced interlocutors (low monitoring condition in Experiment 2). We did not predict this difference for low-L2 proficient bilinguals. The similarity between the interlocutor and the participants might have played a role in reducing interference and conflicts. However, at this point, this is mere speculation, and more studies need to be carried out with bilinguals of varying proficiencies exposed to varying interactional context to understand how control processes adapt to these situations.

One critical aspect of our study is that the high monitoring condition in Experiment 2 had the same design as Experiment 1. It is necessary to examine if the results followed a similar pattern in both the experiments. The high-L2 proficient bilinguals in both the experiments showed a similar pattern of performance. However, this was not the case with low-L2 proficient bilinguals. They showed reduced conflict effect in the presence of neutral interlocutors in Experiment 1, but not in the high monitoring condition of Experiment 2. To see if this was the result of the difference in proficiencies of low-L2 proficient bilinguals in the two experiments, we compared the L2 composite scores and found no significant difference (t = −0.40, p = .68). We are not clear why this difference was observed since these participants did not differ in any of the language measures.

The data from the control experiment (which was considered as a baseline measure of executive control) indicates that high-L2 proficient bilinguals were faster in responding to the Flanker arrows compared to low-L2 proficient bilinguals. This RT advantage aligns with the results from previous studies which showed a bilingual advantage in executive functioning (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Hernandez and Sebastian-Galles2008; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Hernandez, Costa-Faidella and Sebastian-Galles2009; Mishra & Singh, Reference Mishra and Singh2014; Singh & Mishra, Reference Singh and Mishra2012, Reference Singh and Mishra2013, Reference Singh and Mishra2015; Tse & Altarriba, Reference Tse and Altarriba2014). According to Hilchey and Klein (Reference Hilchey and Klein2011), this advantage may be considered as a result of a superior executive network. Thus, the results from the control task suggest that executive control is modulated by language proficiency in bilinguals. This difference between high and low-L2 proficient bilinguals might be a possible reason for the difference in the adaptation (adaptation to different interlocutors) processes as well (Kar et al., Reference Kar, Khare, Dash, Mishra and Srinivasan2011). In the error analysis (Experiment 1), the three-way interaction between trial-type, interlocutor and group was significant but further pair-wise comparison indicated no significant interactions. To see whether this is in line with the RT analysis, we decided to investigate further.Footnote 1 In the RT analysis, the difference between high-L2 and low-L2 proficient bilinguals was smaller in the presence of balanced interlocutor compared to neutral and unbalanced interlocutors. However, the error analysis showed that this difference was smaller in the presence of neutral interlocutors compared to balanced and unbalanced interlocutors. Though the main effect of interlocutor was not present in the error analysis, we observed that participants made more errors in the presence of an unbalanced interlocutor compared to the balanced and neutral interlocutors. Also, the difference between high-L2 and low-L2 proficient bilinguals were more in the presence of unbalanced interlocutors followed by neutral and balanced interlocutors respectively showing a similar pattern of results with the RT analysis. To rule out the speed-accuracy tradeoff, the correlation between RT and accuracy data was calculated (Manoach, Lindgren, Cherkasova, Goff, Halpern, Intriligator & Barton, Reference Manoach, Lindgren, Cherkasova, Goff, Halpern, Intriligator and Barton2002; Salthouse & Hedden, Reference Salthouse and Hedden2002). The results show a negative correlation between RT and accuracy data (r = −.453, p < .001); that is, we observed that when participants had faster RTs, they were more accurate (see supplementary file for more details, Supplementary Materials). Further, to see if interlocutors contributed to this correlation, we considered the RT and accuracy rates in the three interlocutor conditions. It was found that the RT was negatively correlated with the accuracy rate under each condition, indicating no speed-accuracy tradeoff. However, a definitive conclusion could not be drawn because of the small percentage of errors (around 2.5%).

This is the first study to demonstrate that bilinguals go beyond activating a language to an interlocutor (Li et al., Reference Li, Yang, Scherf and Li2013; Molnar et al., Reference Molnar, Ibanez-Molina and Carreiras2015; Woumans et al., Reference Woumans, Martin, Vanden Bulcke, Van Assche, Costa, Hartsuiker and Duyck2015), but also dynamically change their executive control settings. Our assumption that a task-irrelevant interlocutor will modulate a bilingual's cognitive state is also consistent with findings that have shown bilinguals’ sensitivity to interlocutors even when there is no direct interaction (Blanco-Elorrieta, Emmorey & Pylkkanen, Reference Blanco-Elorrieta, Emmorey and Pylkkanen2018; Blanco-Elorrieta & Pylkkanen, Reference Blanco-Elorrieta and Pylkkanen2017; Timmer, Christoffels & Costa, Reference Timmer, Christoffels and Costa2018). Kapiley and Mishra (Reference Kapiley and Mishra2018) demonstrated using a similar research design that bilinguals activate languages differently using their perception of the cartoon interlocutor's linguistic abilities. However, there are several limitations to our study at this point in time. From this data, we cannot point the source of dynamic control in bilinguals; whether this is linguistic or non-linguistic in nature? We assume that it is stemming from the linguistic suppression (dependent on the interactional context), which is also related to executive control ability. Further, at this juncture, the question of enhanced executive control in bilinguals has become debatable (Bialystok et al., Reference Bialystok, Craik and Luk2012; Bialystok, Poarch, Luo & Craik, Reference Bialystok, Poarch, Luo and Craik2014; Kroll & Bialystok, Reference Kroll and Bialystok2013; Paap & Greenberg, Reference Paap and Greenberg2013; Paap, Johnson & Sawi, Reference Paap, Johnson and Sawi2015). The current study was conducted with young adult students who work and stay in a highly bi-multilingual setup. Traditionally, studies have focused on the role of L2 proficiency on the cognitive consequences of bilingualism (Andreou & Karapetsas, Reference Andreou and Karapetsas2004; Dash & Kar, Reference Dash and Kar2014; Montrul, Reference Montrul2009; Singh & Mishra, Reference Singh and Mishra2013; Mishra & Singh, Reference Mishra and Singh2014) assuming L1 proficiency to remain stable across a range of L2 proficiencies. But, observing enhanced L1 proficiency in high-L2 proficient bilinguals compared to low L2 proficient bilinguals is not without precedence (Asbjornsen, Reference Asbjornsen2013; Rosselli, Ardila, Lalwani & Velez-Uribe, Reference Rosselli, Ardila, Lalwani and Velez-Uribe2016; Schmid & Yılmaz, Reference Schmid and Yılmaz2018). We observed that the high-L2 proficient participants in our study had higher proficiency in both L1 and L2 language measures. Balanced bilinguals tend to have better language competence and better inhibitory control (Edele, Kempert & Schotte, Reference Edele, Kempert and Schotte2018; Weber, Johnson, Riccio & Liew, Reference Weber, Johnson, Riccio and Liew2016; Yow & Li, Reference Yow and Li2015). We acknowledge that our high-L2 proficient bilinguals could have higher language competence overall which in turn reflected in the executive control. Hence, future studies should focus more on controlling different participant characteristics (or factors) such as language dominance, L1 and L2 proficiency, the use and exposure of different languages, the context in which the participants are situated, etc. to get a clearer understanding of its effects. Thus, it is possible that future studies that explore the contextual effects in a different linguistic environment will find different results. It is also important to explore how interlocutor-related control settings change over a long period as bilinguals move from highly monolingual to bilingual set-ups. We also find that adding an L2-dominant interlocutor (an unbalanced interlocutor who mostly speaks L2) to the experiment will provide a better understanding of the control mechanisms in different contexts. In the presence of an L2-dominant interlocutor, we expect that (a) a high-L2 proficient bilingual can easily adapt to the conversation, whereas (b) for a low-L2 proficient bilingual it will be difficult. Since the monitoring demands imposed by an L2-dominant interlocutor are lower compared to a balanced interlocutor, but higher than an unbalanced interlocutor, we expect the conflict effect to be inbetween the two interlocutors. The study provides support to the idea that a task-irrelevant interactional context can indeed shift one's executive system to an enhanced level, which in turn enhances the non-verbal conflict resolution. More studies need to be conducted to identify the control mechanisms bilinguals need in a particular context and the nature of adaptation. The Indian context provides a perfect opportunity to study these kinds of interactions since, at any given point of time, the chances of encountering interlocutors of differing language profiles are high.

Conclusion

The nature of socio-linguistic accommodation in bilinguals is complicated. The study provides valuable insights into the nature of this adaptation in different interactional contexts. It shows that bilinguals are sensitive to their environmental context and that they adapt to their interlocutors by taking into consideration their relative proficiencies (Mishra, Reference Mishra2018). We found that the control mechanisms adjust dynamically depending on the interactional context. Future studies should focus on the kind of control mechanisms involved in these adaptation processes and how interlocutor-specific they are.

Supplementary Material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728920000528

Acknowledgments

We thank Seema Gorur Prasad for her significant help throughout the preparation of the manuscript; Keerthana Kapiley for her help in manuscript editing and Yesudas Thomas for assistance with the preparation of cartoons. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Appendix 1

Scheme of the experiment